Abstract

PURPOSE

Renal artery aneurysms (RAAs) are rare in the general population, although the true incidence and natural history remain elusive. Conventional endovascular therapies such as coil embolization or covered stent graft may cause side branches occlusion, leading to organ infarction. Flow diverters (FDs) have been first designed to treat cerebrovascular aneurysms, but their use may be useful to treat complex RAAs presenting side branches arising from the aneurysmal sac. We aimed to evaluate the mid-term follow-up (FUP) safety and efficacy of FDs during the treatment of complex RAAs.

METHODS

Between November 2019 and April 2020, 7 RAAs were identified in 7 patients (4 men, 3 women; age range 55-82 years; median 67 years) and treated by FDs. Procedural details, complications, morbidity and mortality, aneurysm occlusion, and segmental artery patency were retrospectively reviewed. Twelve months of computed tomography angiography (CTA) FUP was evaluated for all cases.

RESULTS

Deployment of FDs was successful in all cases. One intraprocedural technical complication was encountered with one FD felt down into aneurism sac which requiring additional telescopic stenting. One case at 3 months CTA FUP presented the same complication, requiring the same rescue technique. At 12 months CTA FUP, 5 cases of size shrinkage and 2 cases of stable size were documented. No rescue surgery or major intraprocedural or mid-term FUP complication was seen.

CONCLUSION

Complex RAAs with 2 or more side branches can be safely treated by FD. FD efficacy for RAA needs further validation at long-term FUP by additional large prospective studies.

Main points

Flow-diverter treatment for bifurcation renal artery aneurysms

Angio-computed tomography follow-up after renal aneurysms treatment

Novel endovascular technique for visceral aneurysms

Renal artery aneurysm (RAA) is a rare pathology with an estimated incidence of 0.09% in autopsies and with an incidence estimated in angiographic series of 0.1%-1% in normal population, reaching up to 2.5% in hypertensive population. They account for 22%-25% of all visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs).1,2

RAAs could be classified according to their shape (saccular and fusiform), location (extra- and intra-parenchymal), and wall (dissecting and non-dissecting).2

Risk factors associated with the development of a RAA are fibromuscular dysplasia, atherosclerosis/hypertension, and hereditary connective tissue dysplasias (Marfan syndrome) or vasculitis (Behcet disease).3

Indication for treatment includes diameter size > 2 cm or volume increase, symptoms, hematuria, hypertension, pregnancy (due to higher risk of rupture during childbearing), and acute rupture.1 Aneurysmal rupture is noted in up to 5.6% and is considered a life-threatening condition. Increased risk of rupture is seen during pregnancy.2

Thanks to technical improvement and accumulation of clinical experience, endovascular treatment represents a safe and successful strategy. Coil embolization and stent grafts are the most tested techniques, reported in numerous studies, where treatment choice is made according to the anatomical characteristics of the aneurysm and the parent arteries.3

The aim of the treatment should be the selective occlusion of the aneurysm maintaining normal blood flow to the renal parenchyma; for peripheral lesions, located on a distal branch of the renal artery, as hilar bifurcation or trifurcation, coil embolization or covered stents lead to the sacrifice of parent arteries, determining an increased risk of end-organ ischemia, with possible consequence on the kidney function.2,4

Furthermore, coil embolization in fusiform or wide neck aneurysm cannot be proposed for the potential coil migration or parent vessel occlusion.5

The application of flow-diversion techniques in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms has represented a revolution in neurovascular interventions: in fact, flow diverters (FDs) are specifically designed to maintain laminar flow in the parent artery and side branches patency, while reducing flow velocity within the aneurysm, thus promoting thrombosis of the sac.6,7

The use of a variety of FD techniques for the treatment of VAA and pseudoaneurysms has recently been reported, with good results in terms of stent patency and aneurysm sac reduction rates.8-11

In this study, a multicentric technical experience and clinical outcomes in 7 patients presenting a hilar RAAs with 2 or 3 arising branches from the sac, treated with FD as an alternative approach to conventional endovascular treatment, in order to preserve renal arteries branches and segmental distal patency was reported.

Methods

Patients’ characteristics

Between November 2019 and April 2020, 7 patients with RAA were identified (4 men, 3 women; age range 55-82 years; median 67 years) and treated by endovascular team of interventional radiologists and neuroradiologists.

Ethical committee approval number was 101568 R.C.E.164/20. Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from the research subjects.

All RAAs were treated using Derivo Embolization Device (DED, Acandys), an FD safely and effectively used for intracranial aneurysm treatment.12,13

Before intervention, no patients presented renal dysfunction. No signs of acute rupture were collected, and post-traumatic/mycotic pseudoaneurysms were excluded in this study.

Seven patients had a hilar saccular RAA ranging in size from 20 to 26 mm; only 1 of these patients had a horseshoe kidney and another patient had Marfan syndrome. Moreover, 6 out of 7 patients had a saccular aneurysm at the level of the hilar bifurcation and only 1 patient at the level of the hilar trifurcation.

Finally, 2 of the 7 patients presented with multiple aneurysms of the visceral arteries. Indications to treat were given for RAA size > 2 cm and aneurysm volume increase to 2 cm specifically for patient number 2 and number 3.

Endovascular procedures

In this study, DED was chosen for its characteristics of flexibility and large diameters available. This device has flared ends for a secure wall apposition immediately after the initial distal opening, while the foreshortening on the proximal end is reduced.

Mesh density enables in RAAs flow diversion away from the sac while maintaining the flow into the side branches, avoiding renal infarction. Lastly, the device can be safely recaptured and repositioned if an adjustment and superior placement is needed.

Vascular access was based on the anatomy of the renal artery and its arising angle from the aorta. Four patients by transfemoral access and 3 patients by transhumeral access were treated.

In 3 patients, renal artery was catheterized via humeral artery using a 6F long sheath (NeuronMax, Penumbra), a 5F intermediate catheter (Catalyst, Stryker Neurovascular) over a 0.27 microcatheter (Excelsior XT-27, Striker Neurovascular).

Four femoral access were performed using a 6F long sheath (Destination, Terumo) over a 5F intermediate catheter (Catalyst, Stryker Neurovascular) over a 0.27 microcatheter (Excelsior XT-27, Striker Neurovascular).

In all cases, the microcatheter was advanced into the target vessel on a 0.014” guidewire, and then, an FD was deployed.

All patients received antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day starting 7-10 days before the treatment. During procedures, anticoagulation was provided using intravenous administration of heparin 50 U/kg monitoring blood activated clotting time (ACT): the ACT level was maintained above 250 seconds.

All patients continued acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg/die plus clopidogrel 75 mg/die. After 3 months, clopidogrel was stopped.

Endpoint

The analyzed endpoints were technical success rate, safety, and efficacy and the 12 months computed tomography angiography (CTA) follow-up (FUP). Technical success was defined as successful deployment of FD within the target artery.

Safety was defined as freedom from minor (puncture site hematoma or pseudoaneurysm) or major complications (death, intraprocedural aneurysm sac rupture, acute stent occlusion, or foreshortening). Efficacy was defined as stent and side branches patency and freedom from aneurysm rupture or growth at 12 months after intervention.

Follow-up

Imaging CTA FUP was scheduled at 3 and 12 months.

Results

In all patients, FD was successfully deployed; no ruptures or aneurysm reperfusion after exclusion were observed.

Among the 7 patients treated, in 2 cases (patient 1 and 2), the proximal part of FD prolapsed into the aneurism, 1 during deployment (Figures 1-6) and another at 3 months CTA FUP; both cases were managed with an additional telescopic rescue FD. No clinical consequences were verified.

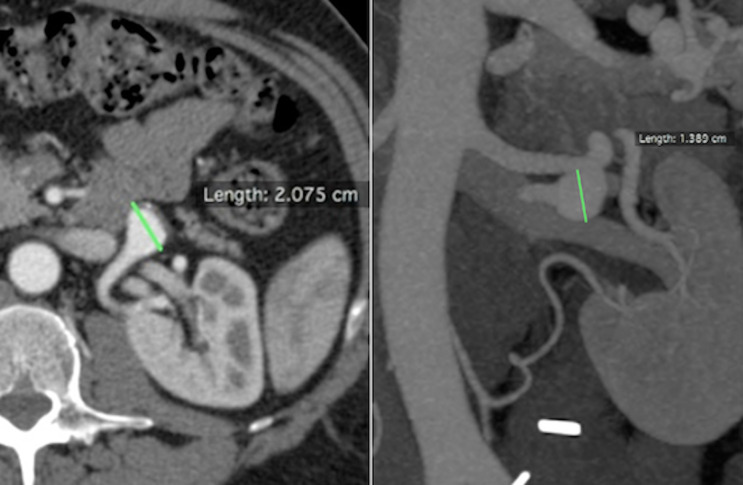

Figure 1.

Patient number 2. Axial and coronal CTA. CTA, computed tomography angiography.

Figure 6.

Patient number 2. One-year CTA FUP documented stent patency and aneurysm dimension stability. FUP, follow-up.

In patient number 3, during the placement of the FD, a stent proximal fish mouth closure was identified and subsequently treated with balloon-expandable stent deployment (RX Herculink Renal Stent System, Abbott) (Figures 7-12).

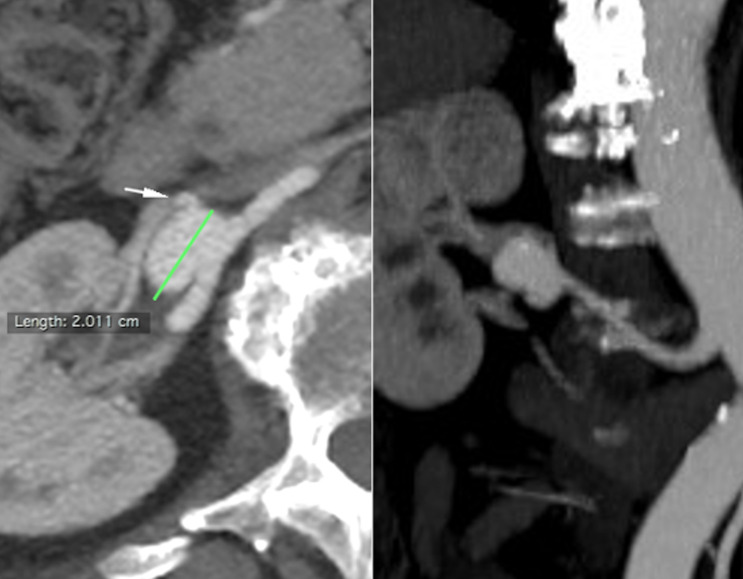

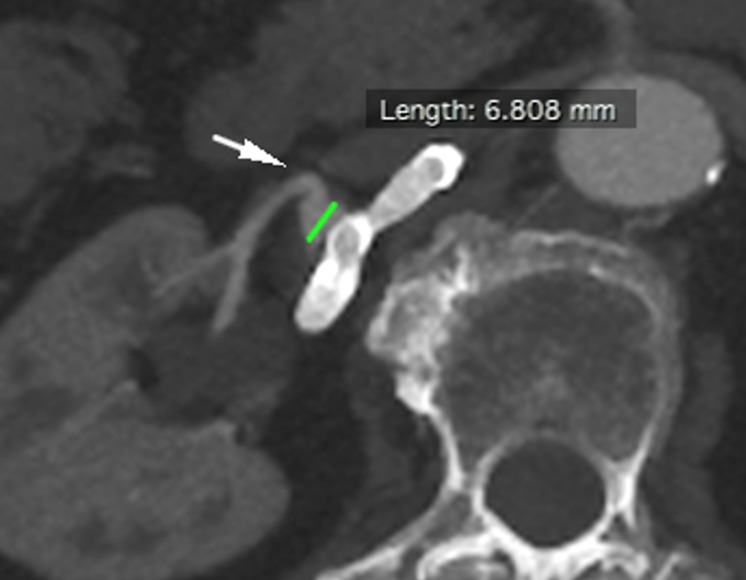

Figure 7.

Patient number 3. Axial and coronal CTA. The white arrow shows a rising branch artery.

Figure 12.

Patient number 3. One-year CTA FUP demonstrated parental artery patency, no renal ischemia, aneurysmal size reduction, with small residual close to a rising branch artery (white arrow).

Patient number 4 with Marfan syndrome, during a preliminary diagnostic contrast injection, dissection of the proximal part of the renal artery occurred and immediately it was treated by a balloon-expandable stent deployment (RX Herculink Elite Renal Stent System, Abbott).

Focal ischemic injury of the kidney upper pole was diagnosed in 1 patient (patient number 2) at 3 months CTA FUP. No segmental artery occlusion was revealed.

No other major (death, intraprocedural aneurysm sac rupture, acute stent occlusion, or foreshortening) or minor complication (puncture site hematoma or pseudoaneurysm) was observed.

Twelve months CTA FUP shows stent patency in all patients. In 5 cases, shrinkage in the size of the aneurysm was documented, and in the 2 remaining cases, the aneurysm was unchanged. In all cases, the segmental arteries were preserved at 12 months CTA FUP (Table 1).

Table 1.

RAA features, procedural details, and follow-up findings

| Case number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of RAA | Hilar aneurysm in a horseshoe kidney | Hilar bifurcation, saccular LRA | Hilar bifurcation, saccular RRA | Hilar trifurcation, saccular LRA | Hilar bifurcation, saccular RRA | Hilar bifurcation, saccular RRA | Hilar bifurcation saccular LRA |

| RAA size (mm) | 25 | 20 | 20 | 26 | 23 | 24 | 26 |

| Type of device | DED | DED | DED | DED | DED | DED | DED |

| Size of the DED (diameter × length, mm) | 5.5 × 40 | 6 × 30 | 5.5 × 50 | 6 × 40 | 5 × 60 | 5.5 × 50 | 6 × 50 |

| Additional interventional | After 3 months FU telescopic rescue FD (6 × 50 mm) | Intraprocedural telescopic rescue FD (6 × 30 mm) | Intraprocedural proximal balloon-expandable stent (RX Herculink Elite Renal Stent System, 4 × 12 mm) | Intraprocedural proximal balloon-expandable stent (RX Herculink Elite Renal Stent System, 5.5 × 18 mm) | None | None | None |

| Complications | None | Distal segmental artery occlusion | None | None | None | None | None |

| Follow-up (FU) 1 year | |||||||

| RAA size (mm) | 22 | 20 | 6 | 26 | 5 | 23 | 8 |

| % RAA size reduction | 12 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 78 | 4.2 | 69.3 |

| Stent patency | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

RAA, renal artery aneurysms; LRA, left renal artery; RRA, right renal artery; DED, Derivo Embolization Device; FD, flow diverter; FU, follow-up.

Discussion

Endovascular treatment for a personalized approach to different anatomic variables and a reduced invasiveness along with lower morbidity/mortality rates should be today preferred over nephrectomy in the first instance.

Despite some authors lately recommend a conservative approach, it is commonly accepted that indications for treatment of a RAAs are major diameter of 2 cm or more and/or signs of progression in FUP imaging. Smaller aneurysms should be treated when patients are symptomatic, presenting with refractory hypertension, rupture/hemorrhage, flank pain, when they have a single kidney, or in women of child-bearing age seeking pregnancy, because the incidence of rupture during pregnancy is higher (80%).1,2,14

Conventional in situ surgical vessels reconstruction include aneurysm resection with primary angioplastic closure with or without branch reimplantation, patch angioplasty, primary re-anastomosis, interposition bypass, aorto-renal bypass, splanchno-renal bypass, and plication of small aneurysms.4

While complex distal branch lesions were historically treated with nephrectomy, they may best be approached with ex vivo repair and auto-transplantation.4 Murray et al.15 described a 92% success rate with in situ bifurcation and ex vivo multi-branch replacement with branched and unbranched internal iliac artery autograft in 12 patients with aneurysms without mortality or major morbidity. Gallagher et al.16 reported seven ex vivo reconstructions for complex aneurysmal disease with excellent technical success. Chandra et al.17 compared in situ and ex vivo reconstructions and noted no significant difference in hospital length of stay, morbidity, mortality, or need for reoperation at FUP.

Traditional endovascular therapies have utilized coil embolization for distal and parenchymal aneurysms and stent graft exclusion for main renal artery lesions. The indications for endovascular repair have broadened with the introduction of 3-dimensional detachable coils, remodeling techniques (which include balloon- and stent-assisted coiling), and FDs.

Embolization with coils requires sac catheterization and is not feasible in the case of unfavorable large aneurysm neck or in the presence of side branches arising from the neck or the aneurysmal sac itself.1,3

Covered stent grafts have been used to treat RAA with good technical success rate, but their use in complex RAAs may obstruct side branch perfusion, leading to kidney infarction.18,19

The classification of 3 groups of RAA by Rundback et al.20 did not distinguish RAA bifurcation or trifurcation morphology. In these case series, aneurisms morphology of bifurcation or trifurcation RAAs precluded the use of conventional coil embolization, standard self-expanding or balloon-expandable covered stents; in this study, FD was then chosen, in order to preserve existing side branches arteries.

The use of FDs during aneurysms treatment has been widely accepted in recent years, since they promote the reconstruction of the parent vessel.9 The stasis of blood flow in the aneurysm leads to an inflammatory response, followed by thrombosis and healing of the aneurysm, while the stent acts as a scaffold for neointimal proliferation and remodeling of the parent vessel.21

Although the flow-modulation mechanism leads to earlier sac depressurization, the time required to achieve aneurysm exclusion, in comparison to conventional techniques, is longer, in terms of weeks to months. However, rather than the thrombosis, the most predictive effect of clinical success is the dimensional reduction of the sac, which is the result of aneurysm depressurization.6

In this case series, some technical corrections during endovascular intervention were needed.

In patients 1 and 2, the proximal part of FD prolapsed into the aneurysm. DED device need to be correctly sized during preprocedural planning, because undersizing of the FD may cause inadequate wall apposition of the device and incomplete coverage of the aneurysm neck, which may compromise aneurysm occlusion.22,23

DED misures were planned according to 3-dimensional digital subtraction angiography (DSA), slightly overestimating DED devices in all cases.

FD prolapses have been attributed to the structure of the FD itself: DEDs are characterized by the presence of only distal flares, without proximal flares, probably leading stent proximal prolapse into the aneurysm sac. To overcome this complication, it could be useful to use an FD with flares in the proximal part rather than distal or more overestimating DED diameters.

Since these stents are specifically designed for intracranial circulation, the maximum available diameter at the moment of DED use was 6 mm; thus, the treatment can only be proposed for vessels with a maximum caliber less of 6 mm.

Device opening was difficult in 1 patient (patient 3): DED’s fish-mouthed formation at the proximal part caused insufficient opening of the stent. This was rescued with an additional balloon-expandable stent with proper wall apposition. This patient was discharged without any renal deficit and stent patency was confirmed at 3 months CTA FUP. We attributed this complication vascular tortuosity.

Technical success was obtained in all cases we reported, similar to other cases described in the literature7-11: in all patients, DED deployment was successfully accomplished and stent patency was documented at 12 months CTA FUP. The median hospital stay was 3 days as Colombi et al.9 experience.

In this multicentric experience, all segmental arteries remained patent at 3 and 12 months CTA FUP with no narrowing or shrinkage of caliber.

A small infarct area was diagnosed in 1 patient at 3 months CTA FUP. The jailed branch was patent in the absence of size reduction or remodeling, without symptoms or alterations of laboratory analysis. We attributed this infarction to the migration of an embolus.

There are several clear advantages using flow diversion techniques: the aneurysmal artery is treated at the neck, which is the point most at risk of future recurrence, side branches patency is preserved and, finally, the risk of incidental rupture associated with aneurysm sac catheterization and intrasaccular maneuvers are avoided. Furthermore, FD treatment is a very fast procedure, reducing hospital stay and being feasible under local anesthesia, without the need for general anesthesia, avoiding all the complications that this could lead to.

Some limitations for repairing RAAs with FD should be considered. First, small number of cases, collected retrospectively; second, the need to wait the aneurysms sac reduction or thrombosis; third, the double antiplatelet therapy can lead to RAA rupture or elsewhere bleeding; fourth, the FD high costs compared to both endovascular and surgical treatment should be considered, as in these case series 2 cases resulted in the use of more than one FD.

Conclusion

Initial clinical experience with FDs in the treatment of complex RAAs yielded satisfactory results in technical success, aneurysm sac thrombosis and shrinkage, and branch vessel patency. No FDs thrombosis or aneurysm rupture after treatment occurred. Larger clinical prospective series with longer FUP will clarify the role of FDs for RAAs.

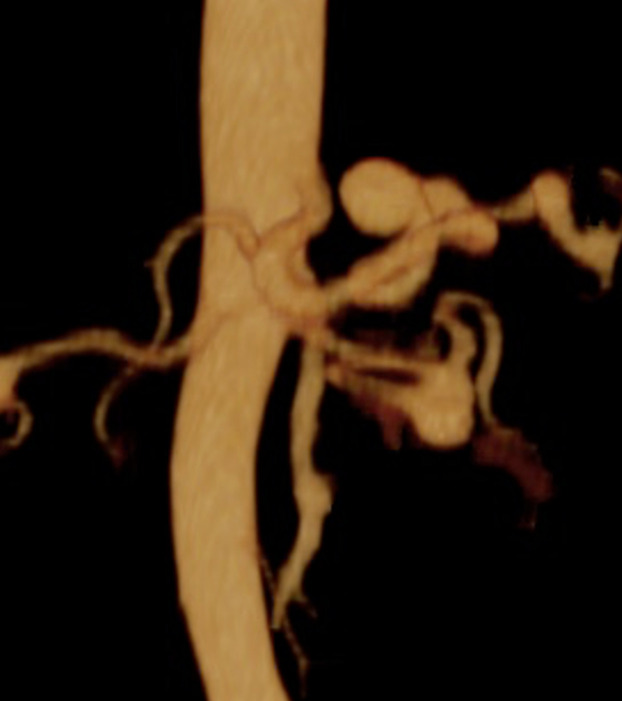

Figure 2.

Patient number 2. 3D CTA. 3D, three-dimensional.

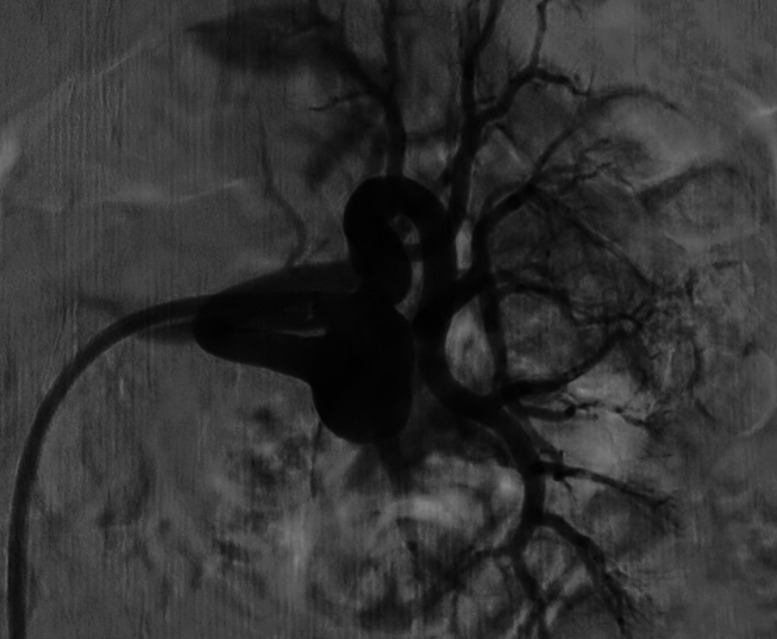

Figure 3.

Patient number 2. Selective left renal artery DSA demonstrated a hilar bifurcation RAA. DSA, digital subtraction angiography; RAA, renal artery aneurysm.

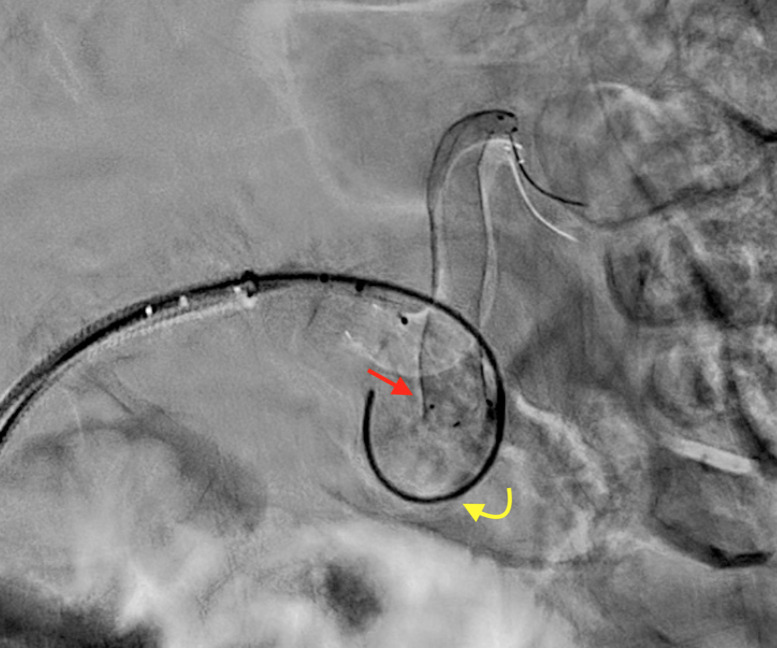

Figure 4.

Patient number 2. During treatment, proximal FD prolapsed into the aneurysm sac, just after deployment. The red straight arrow indicates the prolapsed stent, while the yellow curved arrow refers to the hydrophilic 0.035″ guidewire used for FD renavigation. FD, flow diverter.

Figure 5.

Patient number 2. The malpositioning was rescued by an additional telescopic FD.

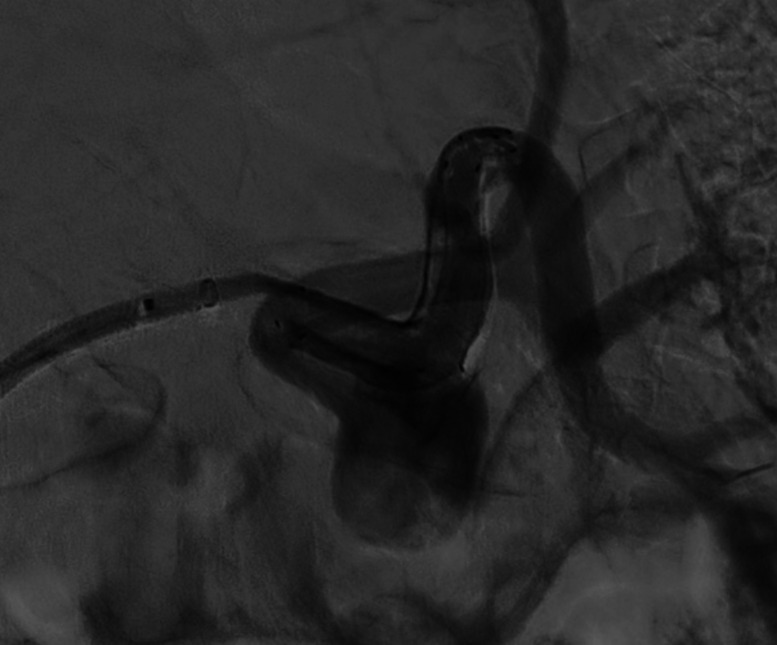

Figure 8.

Patient number 3. Selective right renal artery DSA showed a hilar trifurcation RAA.

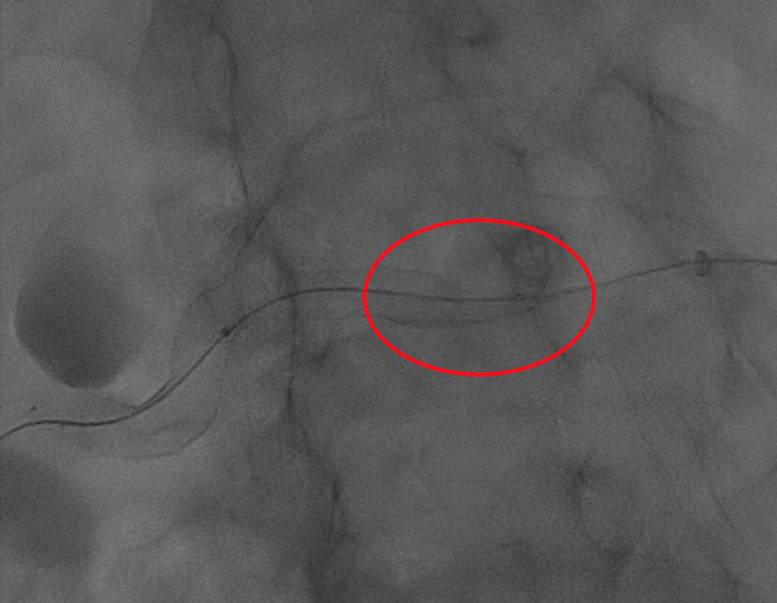

Figure 9.

Patient number 3. During FD placement, a stent fishmouth was observed proximally (red circle).

Figure 10.

Patient number 3. A stent fishmouth was subsequently treated by balloon expandable stent delivery (RX Herculink Renal Stent System).

Figure 11.

Patient number 3. Final DSA showed aneurysmal contrast stasis

References

- 1. Tham G, Ekelund L, Herrlin K, Lindstedt EL, Olin T, Bergentz SE. Renal artery aneurysms. Natural history and prognosis. Ann Surg. 1983;197(3):348 352. 10.1097/00000658-198303000-00016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elaassar O, Auriol J, Marquez R, Tall P, Rousseau H, Joffre F. Endovascular techniques for the treatment of renal artery aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34(5):926 935. 10.1007/s00270-011-0127-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Henke PK, Cardneau JD, Welling TH.et al. Renal artery aneurysms: a 35-year clinical experience with 252 aneurysms in 168 patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234(4):454 62; discussion 462. 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coleman DM, Stanley JC. Renal artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(3):779 785. 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.05.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Etezadi V, Gandhi RT, Benenati JF.et al. Endovascular treatment of visceral and renal artery aneurysms. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(9):1246 1253. 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.05.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sfyroeras GS, Dalainas I, Giannakopoulos TG, Antonopoulos K, Kakisis JD, Liapis CD. Flow-diverting stents for the treatment of arterial aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(3):839 846. 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.04.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabuffi P, Bruni A, Antonuccio EGM, Ambrogi C, Vagnarelli S. Treatment of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms with the use of cerebral flow diverting stents: initial experience. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3(1):48. 10.1186/s42155-020-00137-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardman RL, Taussky P, Kim R, O'Hara RG. Post-transplant hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm treated with the pipeline flow-diverting stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(4):1043 1046. 10.1007/s00270-015-1115-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colombi D, Bodini FC, Bossalini M, Rossi B, Michieletti E. Extracranial visceral artery aneurysms/pseudoaneurysms repaired with flow diverter device developed for cerebral aneurysms: preliminary results. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;53:272.e1 272.e9. 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.05.072) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abraham RJ, Illyas AJ, Marotta T, Casey P, Vair B, Berry R. Endovascular exclusion of a splenic artery aneurysm using a pipeline embolization device. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(1):131 135. 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.09.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adrahtas D, Jasinski P, Koullias G, Fiorella D, Tassiopoulos AK. Endovascular treatment of a complex renal artery aneurysm using coils and the pipeline embolization device in a patient with a solitary kidney. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;36:291.e5 291.e9. 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.03.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kraus B, Goertz L, Turowski B.et al. Safety and efficacy of the Derivo Embolization Device for the treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a multicentric study. J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2019;11(1):68 73. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-013963) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akgul E, Onan HB, Akpinar S, Balli HT, Aksungur EH. The DERIVO embolization device in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: short- and midterm results. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:229 240. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.101) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hellmund A, Meyer C, Fingerhut D, Müller SC, Merz WM, Gembruch U. Rupture of renal artery aneurysm during late pregnancy: clinical features and diagnosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(3):505 508. 10.1007/s00404-015-3967-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murray SP, Kent C, Salvatierra O, Stoney RJ. Complex branch renovascular disease: management options and late results. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20(3):338 345. 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90131-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gallagher KA, Phelan MW, Stern T, Bartlett ST. Repair of complex renal artery aneurysms by laparoscopic nephrectomy with ex vivo repair and autotransplantation. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(6):1408 1413. 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.07.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chandra A, O’Connell JB, Quinones-Baldrich WJ.et al. Aneurysmectomy with arterial reconstruction of renal artery aneurysms in the endovascular era: a safe, effective treatment for both aneurysm and associated hypertension. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(4):503 510. 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.07.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gandini R, Spinelli A, Pampana E, Fabiano S, Pendenza G, Simonetti G. Bilateral renal artery aneurysm: percutaneous treatment with stent-graft placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29(5):875 878. 10.1007/s00270-004-8209-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray TÉ, Brennan P, Maingard JT.et al. Treatment of visceral artery aneurysms using novel neurointerventional devices and techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(9):1407 1417. 10.1016/j.jvir.2018.12.733) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rundback JH, Rizvi A, Rozenblit GN.et al. Percutaneous stent-graft management of renal artery aneurysms. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(9):1189 1193. 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61362-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kadirvel R, Ding YH, Dai D, Rezek I, Lewis DA, Kallmes DF. Cellular mechanisms of aneurysm occlusion after treatment with a flow diverter. Radiology. 2014;270(2):394 399. 10.1148/radiol.13130796) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Estrade L, Makoyeva A, Darsaut TE.et al. In vitro reproduction of device deformation leading to thrombotic complications and failure of flow diversion. Interv Neuroradiol. 2013;19(4):432 437. 10.1177/159101991301900405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mut F, Cebral JR. Effects of flow-diverting device oversizing on hemodynamics alteration in cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(10):2010 2016. 10.3174/ajnr.A3080) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a