INTRODUCTION

Patient-centered and family-centered care (PFCC) is widely recognized as integral to health-care delivery.1–3 Broadly defined, PFCC is organized around the needs, values, and preferences of patients and their families. In theory, this concept is obvious and easy to endorse. Yet, a growing body of evidence suggests PFCC is challenging to operationalize, particularly in the technical environment of the intensive care unit (ICU).

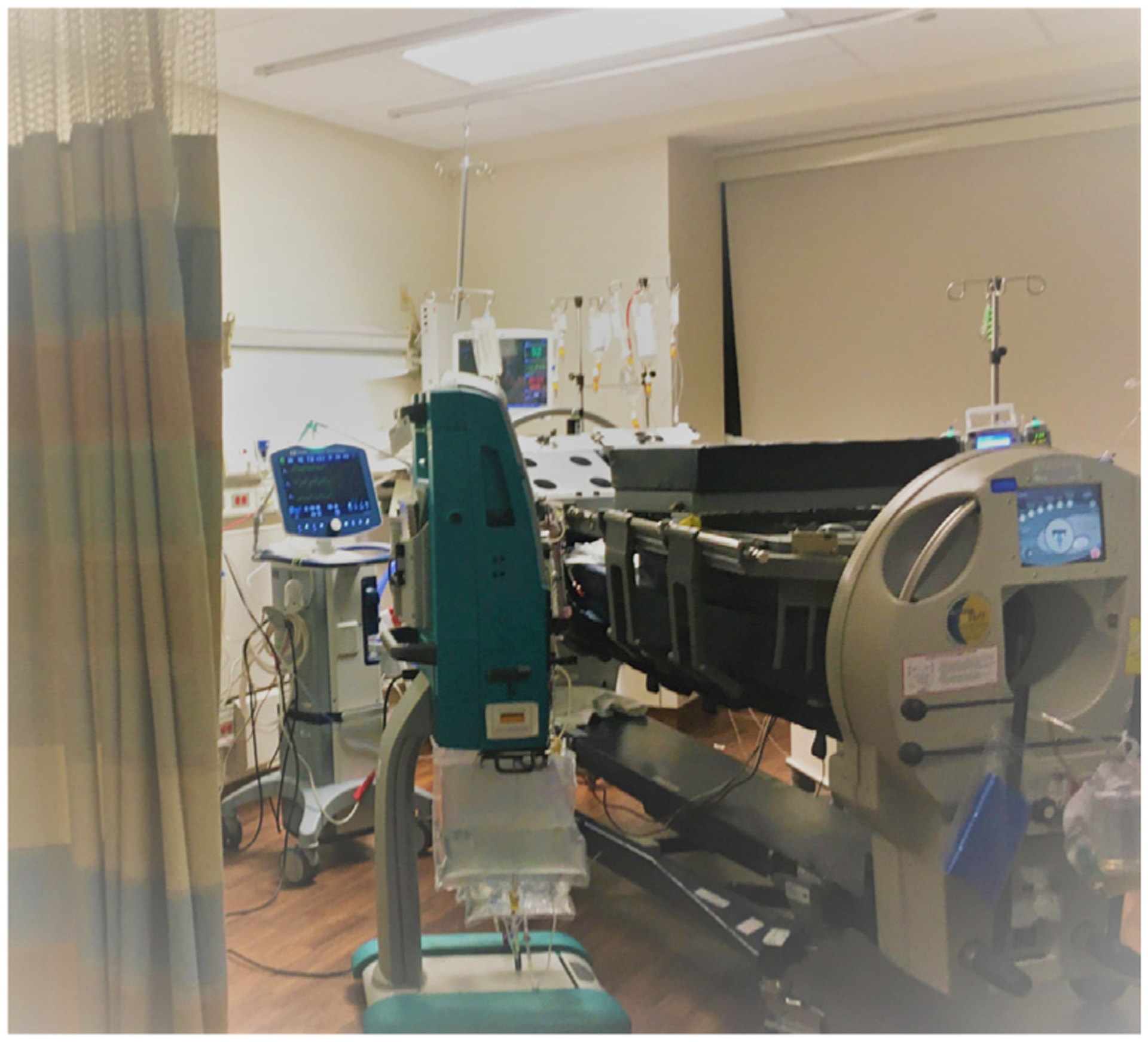

The ICU system is primarily designed to rapidly deliver life-sustaining technology. ICU clinicians are trained to save lives by making decisions quickly and with incomplete information. Through this fundamental nature of the ICU, an imperative to use life-sustaining technology arises that is described by medical social scientists as “giving the best care that is technically possible; the only legitimate and explicitly recognized constraint is the state of the art.”4 Although technological advances have indisputably reduced mortality in critical illness, there is growing recognition that a singular focus on technology can displace human dimensions of care.5 As Fig. 1 illustrates and sociologist Nancy Kentish-Barnes describes, “in the ICU, the patient becomes a body whose organs must be maintained, and this body in turn disappears behind the machines.”6

Fig. 1.

ICU patient in a bed to facilitate prone positioning, surrounded by multiple sources of life-sustaining treatment.

Additionally, critically ill patients are often unable to communicate, which creates challenges for the ICU team to ascertain and uphold patients’ individual values, goals, and preferences. Only 1 of 3 American adults has created an advance directive (AD) describing their preferences about life-sustaining treatment.7 Even when ADs are established, multiple barriers limit their utility, including instability of adults’ end-of-life preferences8,9 and lack of access to AD documents when needed.10 Furthermore, when surrogate decision makers are making treatment decisions on behalf of a critically ill patient, they often struggle to accurately represent the patients’ preferences.11

In this article, we will discuss the history and terminology of PFCC, describe interventions to promote PFCC, and highlight limitations to the current model and future directions.

HISTORY AND TERMINOLOGY

The Picker Institute introduced the concept of “patient-centered care” in 1993 as a response to growing concerns about disease-centered or clinician-centered care.12 This concept included 5 dimensions: (1) respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs; (2) coordination and integration of care; (3) information, communication, and education; (4) physical comfort; (5) emotional support; and (6) involvement of family and friends.”12 In 2001, the Institute of Medicine advocated for patient-centered care that is “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”1

Family-centered care—an approach to health care that is respectful of and responsive to families’ needs and values—was initially introduced in the context of pediatrics13 but is now recognized across populations and care settings.2 Family is defined by the patient as those who provide support and with whom the patient has a significant relationship. Given that patients in the ICU are often too ill to communicate, families are asked to participate in complex medical decision-making. Families also face significant caregiving burden for survivors of critical illness.14 Up to one-half of family members of critically ill patients experience psychological symptoms during and after the critical illness.15,16 Family-centered care in the ICU recognizes the importance of the family to a patient’s recovery, provides support for families for decision-making, caregiving and bereavement, and attempts to reduce future suffering for family members after critical illness.

Several fields and concepts inform and overlap with PFCC. Palliative care medicine is oriented around improving quality of life for patients with serious illness and families by attending to physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs.17 The concept of dignity-conserving care emerged from palliative medicine but applies across the spectrum of health care and emphasizes patients’ personhood.18 The related model of human-centered care arose from the recognition that patients in the ICU are susceptible to dehumanization, the process by which individuals are seen as having lost their positive human qualities.19 To counter this tendency, human-centered care honors the dignity of all persons; it additionally identifies health-care professionals as potential beneficiaries of humanized care settings that may mitigate burnout.20,21 Finally, patient and family engagement (PFE) is considered a key pillar in quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.22 PFE describes a set of behaviors, organizational policies, and values that foster the inclusion of patients and families as active participants on health-care teams and in health-care systems. What unites each of these concepts is the value of human dignity and the notion that the fundamental purpose of health care is respecting the dignity and value of patients and their families.

MEASURING AND QUANTIFYING THE PROBLEM

There is an expanding body of literature dedicated to measuring PFCC. Gazarian and colleagues propose a practical definition of dignity and respect, suggesting that dignity represents the inherent worth of all human beings, and respect represents the behavioral or social norms that appropriately honor and acknowledge such dignity.23 Respectful ICU care requires (1) recognition of fundamental human needs (ie, physical, emotional, and psychological safety), (2) acknowledgment of patients as unique individuals, and (3) attention to the critical status and vulnerability of patients and families in the ICU.19,23–25 Specific behaviors of respectful care are well described25–27; concrete examples are shown in Table 1.19

Table 1.

Examples of respectful and disrespectful behaviors

| Situation | Disrespectful Approach | Respectful Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Entering the patient’s room | Enter without warning or acknowledgment | Knock before entering |

| Approaching a patient’s bed | Neglect to introduce oneself | “Hello, I’m Dr. Schmidt. I’m a physician in training” |

| During emotionally charged encounters (eg, during ACLS or family meeting) | Multiple unintroduced staff, only partly involved | Appropriate staff present; those who are present are introduced and involved |

| Addressing a patient | “Bud” or “Dear” or similarly colloquial term | “Mr./Ms. Jones, what do you prefer that I call you?” (If know, use preferred name) |

| Necessary physical examination in conscious patient | Wordlessly performing the examination | “May I examine your abdomen?” |

| Necessary physical examination in unconscious patient | Wordlessly performing the examination | “I’ll be examining your abdomen” |

| Discussion of “code status” | “If your heart stops, should we try to restart it?” | A personalized approach that considers the contexts and trajectories of illness from the patient’s perspective |

| Rounding | Patients and families excluded from rounds | Patients and families included in rounds |

| Referring to patients | Room 502 or “the heart” | “Jill in 502” or “Steve with heart failure” |

| General protection of modesty/privacy | Private parts of body exposed; drapes left open | Only necessary parts of body exposed; drapes closed |

| Response to patient’s needs, including pain | Slow response times | Timely response |

| Attention during encounter | Reading texts on cell phone; reviewing material for another patient | Attending directly to the given patient and family |

Definition of abbreviation: ACLS, advanced cardiac life support.

Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society.

Copyright © 2021 American Thoracic Society. all rights reserved.

Samuel M. Brown, Elie Azoulay, Dominique Benoit, Terri Payne Butler, Patricia Folcarelli, Gail Geller, Ronen Rozenblum, Ken Sands, Lauge Sokol-Hessner, Daniel Talmor, Kathleen Turner, and Michael D. Howell; The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (Volume 197, Issue 11), pp. 1389–1395.

The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society.

Approximately 30% of ICU patients and families report experiencing disrespect during their ICU stay.28,29 Disrespectful care can damage patient–clinician relationships, lead to long-lasting adverse effects on physical and psychological health,30,31 and may even be associated with risk of physical harm to patients.30,32–34 A multicenter survey demonstrated that more than one-third of ICUs had a poor “climate of mutual respect.”35 A climate in which disrespect and dehumanization is widely accepted may ingrain such behaviors into the wider ICU team and contribute to deficiencies in patient care.36–38 At the same time, high rates of burnout experienced by ICU clinicians may be linked to witnessing or participating in (sometimes unintentional) acts of dehumanization and disrespect.21

Most patient satisfaction surveys include a dimension related to respect.39 The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey is a global assessment of patient satisfaction but does contain dimensions related to respect.40 The family satisfaction in the ICU survey measures satisfaction with care and decision-making, constructs that overlap with acts of respect.41,42 However, surveys assessing patient and family satisfaction may suffer from ceiling effects, wherein responses are skewed favorably, making it difficult to distinguish meaningful change in PFCC.43 Geller and colleagues developed a specific tool to measure ICU patient and family experiences of respect.28 This tool evaluates clinician behaviors such as greetings and introductions, bedside manner, listening and sharing information, attending to modesty, honoring patients’ preferences, and responding to patients’ needs/requests. These behaviors are simple, yet powerful and pragmatic to protect against dehumanization.

Respect is increasingly recognized as a system-level outcome; as such, measurement of respectful behaviors in the ICU requires assessment of unit-level structures. CORE-ICU is a clinician-reported measure of overall environment and climate of respect in the ICU.44 The ethical climate of the ICU, defined as the organizational practices and conditions that affect the way difficult patient care problems are discussed and resolved, is also crucial to optimal ICU functioning.45 The Ethical Decision-Making Climate Questionnaire measures latent factors affecting the decision-making climate in the ICU within 3 domains: interdisciplinary collaboration and communication, physician leadership, and ethical environment.35 Several investigators propose treating acts of disrespect as patient safety events and recommend using existing quality and safety frameworks (such as root cause analysis) to audit such incidents.46,47

INTERVENTIONS TO PROMOTE PATIENT-CENTERED AND FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

Personhood and Humanization

PFCC requires acknowledging patients as unique individuals. Several interventions emphasize eliciting information about patients that refocuses attention on personhood, guards against dehumanization, and promotes deeper connections among patients, families, and clinicians. Chochinov and colleagues developed the single question Patient Dignity Question18: “What do I need to know about you as a person to give you the best care possible?” Another questionnaire documenting personal attributes called “This is Me” (TIME) has been well-received by patients, and clinicians reported TIME enhanced their respect and compassion for patients.48 “About me” boards (Fig. 2) display important information about the patient’s background, personality, interests, and preferences. Such tools may deepen patient–clinician relationships, enhance interdisciplinary communication, and motivate patients and families.49–52 Clinicians describe a deeper sense of meaning and job satisfaction after implementation of a “Get to know me” tool.52

Fig. 2.

ICU Diary “Get to Know Me” page. (From K Taylor A Blair, Sarah D Eccleston, Hannah M Binder, Mary S McCarthy; Journal of Patient Experience (Volume 4, Issue 1), pp. 4–9; copyright © 2017 by SAGE Publications, Inc.; with permission.)

ICU diaries are another intervention to affirm personhood and support patients and families. ICU diaries are written records of the ICU stay maintained by family members and clinicians and may allow patients to reconstruct their illness narrative, combat frightening memories, and regain a sense of reality.53–56 ICU diaries have been shown to mitigate the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, anxiety, and depression in ICU patients and reduce psychological symptoms for family members.53,55,57 Family members value ICU diaries because they help families to understand medical information, communicate with clinicians, and humanize the relationship with the patient and ICU team.58

Family Presence and Participation

Active partnership with patients’ families in the ICU is critical to PFCC. Family presence includes unrestricted visitation,59 participation in daily work rounds with the ICU team,60 and the invitation to remain present during CPR and procedures.61 Family presence in the ICU is associated with decreased anxiety, shorter length of stay, and higher patient and family satisfaction with care.2,62 Family presence has also been shown to decrease the risk for delirium.63,64 Family members’ active participation in patient care activities fosters PFCC. Qualitative studies demonstrate that family members value their role as a care provider for their loved ones in the ICU.65,66 Family members who partnered with nurses to deliver patient care such as bathing or massage perceived increased respect, collaboration, and support.67 Family participation in patient care rituals has been associated with reduced symptoms of PTSD 90 days after patient death or discharge.68

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in deimplementation of many family-centered care practices and has been associated with worse PFCC.69,70 Bereaved family members report not only poor communication and inadequate support during their loved ones’ ICU stay71 but also feelings of abandonment, powerlessness, and unreality, as well as disruptions in typical end-of-life rituals, which can lead to complicated grief.72,73 Limited family presence is linked to poor clinical outcomes. Visitation restrictions resulted in delayed decisions to limit treatments before death and lengthened ICU stays,74 and lack of family presence was associated with a higher risk of delirium for ICU patients with COVID-19.63 Prohibiting family presence has also negatively affected health-care workers. Clinicians reported moral distress related to changing visitation policies and restrictions.75,76 Health-care workers had to facilitate virtual “good byes” between families and dying patients, placing them more clearly in the face of suffering.77 These experiences add to the high burden of burnout in critical care providers.

Communication

A key tenant of PFCC is that patients’ values, goals, and preferences guide medical decision-making. Because family members are often surrogate decision-makers, routine, structured communication with attention to surrogates’ informational needs is widely recommended.2,78 Several randomized trials in the ICU have centered around communication interventions within multifaceted family support interventions.79–81 In a recent trial of a comprehensive family support intervention in the ICU, surrogate decision-makers in the intervention group reported higher quality of communication and degree of patient-centeredness and family-centeredness, although there was no difference in surrogates’ symptoms of anxiety or depression 6 months after ICU discharge.81 The ICU length of stay was lower among patients who died in the hospital in the intervention group. A recent meta-analysis of protocolized family support interventions demonstrated improved communication, enhanced shared decision-making with family, and reduced ICU length of stay.82 Improvements in communication with patients who cannot speak are also paramount to facilitate participation in decision-making and expression of their needs. Strategies to augment patients’ ability to communicate include the use of communication boards and speaking valves and leak speech for ventilated patients.83

THE FUTURE OF PATIENT-CENTERED AND FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

Significant progress has been made in recent years in the promotion of PFCC in the ICU. Yet, further attention is needed in 3 areas: disparities in health-care delivery, patient and family engagement (PFE), and intentional efforts to humanize the ICU workplace environment for the betterment of patients, families, and staff.

Health Disparities and Patient-Centered and Family-Centered Care

There are racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.84 Disparities in incidence and outcomes of critical illness occur before, during, and after critical illness and involve individual, community, and hospital-level factors.85 There are notable disparities in PFCC-focused practices such as serious illness communication and end-of-life care.86–88 African Americans and individuals with limited English proficiency (LEP) experience worse communication quality89,90 are less likely to have ADs and more likely to receive high-intensity care before death and die in the ICU.87,91–93 Disparities in end-of-life care are mediated by multiple factors, including inconsistent access, provider biases, health-care literacy, and patient and family preferences.94 Importantly, more research is needed to understand whether differences in end-of-life care reflect differences in patients’ and families’ values and preferences or whether they represent disparities in health-care delivery.95

By being responsive to preferences, needs, values, and cultural traditions of patients and families, PFCC may reduce inequities in critical care. Specialty palliative care consultation and better serious illness communication may improve disparities in care.96 Palliative care consultation in seriously ill African Americans is associated with higher satisfaction with care, increased documentation of treatment preferences, and higher rates of home death and hospice referrals.97,98 A commitment to culturally competent communication may also mitigate disparities. Errors in medical interpretation are more frequent and more likely of clinical consequence when nonprofessional interpreters are used compared with professional interpreters.99 Implementation of protocols for scheduling interpreters and tracking adherence increases interpreter presence on family-centered rounds for families with LEP.100 Hospitals must stratify clinical, quality, and patient experience data by race, ethnicity, language, and socioeconomic status to better recognize disparities and identify opportunities for improvement. Health systems should provide clinicians with evidence-based racial and cultural sensitivity training and implicit and explicit bias training.101 Studies of communication or family support interventions often exclude people with LEP. We urgently need to include patients and families with diverse cultures and languages in such studies to better inform PFCC best practices.

Meaningful Patient and Family Engagement

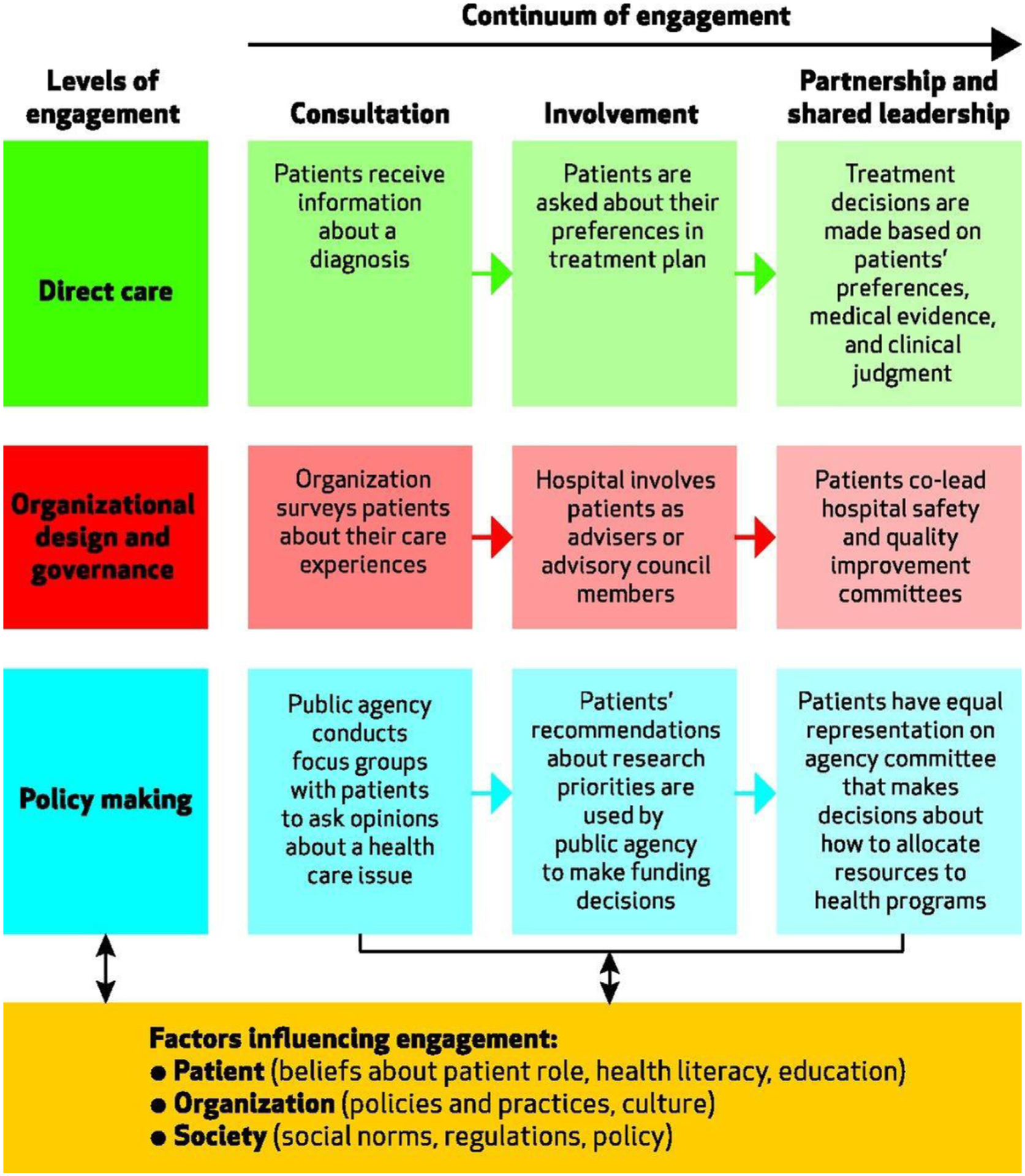

PFE centers health-care delivery around the experiences and priorities of patients and families. Fig. 3 demonstrates 3 critical aspects of PFE: (1) engagement occurs along a continuum, (2) engagement occurs at different levels, and (3) multiple factors affect the willingness and ability of patients to engage. Health-care systems engage patients and families primarily through Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFACs), organizations of current and former patients, family members, and care-givers that work with clinicians and hospital leadership to improve patient and family experience, advise on patient care practices, organizational policies and procedures, and recommend how to better measure and evaluate PFE.102,103 True PFE avoids tokenism, which exists when the unequal power relations among patients, families, and clinicians within the health-care system cause patients and families to have a circumscribed role in these processes.104,105 Organizations should empower PFACs to pursue meaningful projects, integrate patient and family advisors into governance bodies, ensure involvement in community health activities, and promote recruitment and sustained engagement of diverse patient and family representatives.

Fig. 3.

A multidimensional framework for patient and family engagement in health and health care. (From Kristin L. Carman, Pam Dardess, Maureen Maurer, Shoshanna Sofaer, Karen Adams, Christine Bechtel, and Jennifer Sweeney; Health Affairs (Volume 32, Issue 2), pp. 223–231; copyright © 2013 by Project Hope.)

Similarly, patient engagement in research requires moving beyond simple participation to active partnership in research.106 The benefits of PFE in the research process are myriad. Lived experiences of patients and families can inform research questions and priorities, identify patient-centered and family-centered outcomes, and guide researchers to improve enrollment and consent processes. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute champions involvement of patients and families in every step of the research process and has led to a proliferation of patient, family, and community-engaged research.107

Humanism for Health-care Professionals

Critical care health-care professionals suffer high rates of burnout syndrome (BOS), which is characterized by exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.21 BOS is associated with negative mental health outcomes for health-care workers, increased job turnover, reduced patient satisfaction, and decreased quality of care.21 Addressing BOS in ICU clinicians is key to the promotion of PFCC. Mitigating BOS requires a multifaceted approach beyond the scope of this article. In the context of PFCC, we posit the overarching theme of humanization of the ICU should apply to patients, families, and clinicians. We need to value and respect the humanity of our health-care workers if we are to foster a humanized environment for patients and families. A recent consensus document to advance the practice of respect in health-care emphasizes support for health-care professionals.46 However, implementation of programs to monitor and improve the practice of respect could have unintended consequences, such as increasing clinician workload, thereby increasing risk of burnout. Thus, interventions to humanize the ICU must be carefully designed and assessed to ultimately yield the intended effect of improving the ICU environment for all.

SUMMARY

PFCC is integral to high-quality health care and has benefits for patients, families, and clinicians. The highly technical nature of critical care puts patients and families at risk of dehumanization and renders the delivery of PFCC challenging. Deliberate attention to respectful and humanizing interactions with patients, families, and clinicians is essential for successful PFCC in the ICU. Current PFCC efforts focus on patients’ personhood, patient-centered and family-centered communication, and interventions to improve family presence, support, and participation. It is imperative that we study how health-care disparities influence PFCC and, furthermore, explore how PFCC can promote health equity. Optimal PFCC requires authentic engagement with patients and families of diverse backgrounds and experiences to inform quality improvement and research initiatives. Finally, we must work together to create a humanistic ICU environment not just for our patients but for ourselves.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

Patient-centered and family-centered care (PFCC) in the ICU is easy to endorse but can be difficult to actualize in the highly technical critical care environment.

Respecting the dignity and humanity of all persons in the ICU, including patients, families, and ICU team members, is the core practice of PFCC.

Behavioral interventions can help promote dignity and respect in ICU environments and include tools that affirm patients’ personhood, support patient- and family-centered communication, and increase family presence and participation in care.

KEY POINTS.

Patient-centered and family-centered care (PFCC) is challenging to operationalize in the intensive care unit (ICU) environment.

The foundation of PFCC is respect for the dignity and humanity of all persons.

PFCC practices include affirmation of patients’ personhood, patient-centered and family-centered communication, and interventions to improve family presence, support, and participation in care.

Optimal PFCC requires continued efforts to address health-care disparities, encourage authentic patient and family engagement, and humanize the ICU environment for patients, families, and health-care professionals.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT AND FUNDING SOURCES

J.M. Kruser’s time was supported, in part, by NIH/NHLBI grant K23HL146890. J.M. Kruser’s spouse receives honoraria for lectures and speakers bureaus from Astra Zeneca. No other authors report any funding or disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker A Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century 2001;323(7322):1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med 2017;45(1): 103–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, et al. The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit Care Clin 2017;33(2):225–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs VR. The growing demand for medical care. N Engl J Med 1968;279(4):190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todres L, Galvin KT, Holloway I. The humanization of healthcare: a value framework for qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2009; 4(2):68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kentish-Barnes N La mort à l’hôpital. Paris: Seuil; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2017;36(7):1244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auriemma CL, Nguyen CA, Bronheim R, et al. Stability of end-of-life pa systematic review of the evidence. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(7): 1085–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YS, Escobar GJ, Halpern SD, et al. The natural history of changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatments and implications for inpatient mortality in younger and older hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64(5):981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison RS, Olson E, Mertz KR, et al. The inaccessibility of advance directives on transfer from ambulatory to acute care settings. JAMA 1995; 274(6):478–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(5):493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerteis ME-LS, Daley J, Delbanco T. Through the patient’s eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. 1sttioned. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo DZ, Houtrow AJ, Arango P, et al. Family-centered care: current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Matern child Health J 2012;16(2):297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med 2011; 39(2):371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171(9):987–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med 2012;40(2):618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO definition of palliative care. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed March 28, 2021.

- 18.Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, et al. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: effects on patients, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015;49(6):974–80.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown SM, Azoulay E, Benoit D, et al. The practice of respect in the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197(11):1389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasco Bueno JM, La Calle GH. Humanizing intensive care: from theory to practice. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2020;32(2):135–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, et al. A critical care societies collaborative statement: burnout syndrome in critical care health-care professionals. A call for action. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194(1): 106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2013;32(2):223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazarian PK, Morrison CR, Lehmann LS, et al. Patients’ and care partners’ perspectives on dignity and respect during acute care hospitalization. J Patient Saf 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aboumatar H, Forbes L, Branyon E, et al. Understanding treatment with respect and dignity in the intensive care unit. Narrative Inq Bioeth 2015; 5(1a):55a–67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bidabadi FS, Yazdannik A, Zargham-Boroujeni A. Patient’s dignity in intensive care unit: A Critical ethnography. Nurs Ethics 2019;26(3):738–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrese J, Forbes L, Branyon E, et al. Observations of respect and dignity in the intensive care unit. Narrative Inq Bioeth 2015;5(1a):43a–53a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gazarian PK, Morrison CRC, Lehmann LS, et al. Patients’ and care partners’ perspectives on dignity and respect during acute care hospitalization. J Patient Saf 2021;17(5):392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geller G, Branyon ED, Forbes LK, et al. ICU-RESPECT: an index to assess patient and family experiences of respect in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2016;36:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Law AC, Roche S, Reichheld A, et al. Failures in the respectful care of critically ill patients. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2019;45(4):276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Entwistle VA. Hurtful comments are harmful comments: respectful communication is not just an optional extra in healthcare. Health Expect 2008; 11(4):319–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sokol-Hessner L, Folcarelli PH, Sands KE. Emotional harm from disrespect: the neglected preventable harm. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24(9): 550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper WO, Guillamondegui O, Hines OJ, et al. Use of unsolicited patient observations to identify surgeons with increased risk for postoperative complications. JAMA Surg 2017;152(6):522–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernan AL, Giles SJ, Fuller J, et al. Patient and carer identified factors which contribute to safety incidents in primary care: a qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24(9):583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34(8):464–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van den Bulcke B, Piers R, Jensen HI, et al. Ethical decision-making climate in the ICU: theoretical framework and validation of a self-assessment tool. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27(10):781–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foulk T, Woolum A, Erez A. Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: the contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. J Appl Psychol 2016;101(1):50–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woolum A, Foulk T, Lanaj K, et al. Rude color glasses: the contaminating effects of witnessed morning rudeness on perceptions and behaviors throughout the workday. J Appl Psychol 2017; 102(12):1658–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, et al. The impact of rudeness on medical team performance: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2015;136(3):487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handley SC, Bell S, Nembhard IM. A systematic review of surveys for measuring patient-centered care in the hospital setting. Med Care 2021;59(3): 228–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein E, Farquhar M, Crofton C, et al. Measuring hospital care from the patients’ perspective: an overview of the CAHPS Hospital Survey development process. Health Serv Res 2005;40(6 Pt 2):1977–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heyland DK, Tranmer JE. Measuring family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: the development of a questionnaire and preliminary results. J Crit Care 2001;16(4):142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the family satisfaction in the intensive care unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med 2007;35(1):271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moret L, Nguyen JM, Pillet N, et al. Improvement of psychometric properties of a scale measuring inpatient satisfaction with care: a better response rate and a reduction of the ceiling effect. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beach MC, Topazian R, Chan KS, et al. Climate of respect evaluation in ICUs: development of an instrument (ICU-CORE). Crit Care Med 2018;46(6): e502–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007;35(2):422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sokol-Hessner L, Folcarelli PH, Annas CL, et al. A road map for advancing the practice of respect in health care: the results of an interdisciplinary modified delphi consensus study. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2018;44(8):463–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sokol-Hessner L, Kane GJ, Annas CL, et al. Development of a framework to describe patient and family harm from disrespect and promote improvements in quality and safety: a scoping review. Int J Qual Health Care 2019;31(9):657–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan JL, Chochinov H, Thompson G, et al. The TIME Questionnaire: a tool for eliciting personhood and enhancing dignity in nursing homes. Geriatr Nurs (NY) 2016;37(4):273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Billings JA, Keeley A, Bauman J, et al. Merging cultures: palliative care specialists in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006;34(11 Suppl):S388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blair KTA, Eccleston SD, Binder HM, et al. Improving the patient experience by implementing an ICU diary for those at risk of post-intensive care syndrome. J Patient experience 2017;4(1):4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gajic O, Anderson BD. Get to know me” board. Crit Care explorations 2019;1(8):e0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoad N, Swinton M, Takaoka A, et al. Fostering humanism: a mixed methods evaluation of the Footprints Project in critical care. BMJ open 2019; 9(11):e029810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kredentser MS, Blouw M, Marten N, et al. Preventing posttraumatic stress in ICU survivors: a single-center pilot randomized controlled trial of ICU diaries and psychoeducation. Crit Care Med 2018;46(12):1914–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med 2015;43(5): 1121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, et al. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Crit Care (London, England) 2010;14(5):R168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Egerod I, Christensen D, Schwartz-Nielsen KH, et al. Constructing the illness narrative: a grounded theory exploring patients’ and relatives’ use of intensive care diaries. Crit Care Med 2011;39(8): 1922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Coquet I, Périer A, et al. Impact of an intensive care unit diary on psychological distress in patients and relatives. Crit Care Med 2012;40(7):2033–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Périer A, Mouricou P, et al. Writing in and reading ICU diaries: qualitative study of families’ experience in the ICU. PLoS One 2014; 9(10):e110146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giannini A, Miccinesi G, Prandi E, et al. Partial liberalization of visiting policies and ICU staff: a before-and-after study. Intensive Care Med 2013;39(12): 2180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allen SR, Pascual J, Martin N, et al. A novel method of optimizing patient- and family-centered care in the ICU. J Trauma acute Care Surg 2017;82(3): 582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beesley SJ, Hopkins RO, Francis L, et al. Let them in: family presence during intensive care unit procedures. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13(7):1155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kleinpell R, Heyland DK, Lipman J, et al. Patient and family engagement in the ICU: report from the task force of the World Federation of societies of intensive and critical care medicine. J Crit Care 2018;48:251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pun BT, Badenes R, Heras La Calle G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (COVID-D): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9(3): 239–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosa RG, Tonietto TF, da Silva DB, et al. Effectiveness and safety of an Extended ICU visitation model for delirium prevention: a before and after study. Crit Care Med 2017;45(10):1660–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davidson JE. Family-centered care: meeting the needs of patients’ families and helping families adapt to critical illness. Crit Care Nurse 2009;29(3): 28–34 [quiz: 35]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engström A, Söderberg S. The experiences of partners of critically ill persons in an intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2004;20(5):299–308 [quiz: 309–10]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mitchell M, Chaboyer W, Burmeister E, et al. Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family-centered care in adult critical care. Am J Crit Care 2009;18(6):543–52 [quiz: 553]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amass TH, Villa G, Omahony S, et al. Family care rituals in the ICU to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in family members—a multicenter, multinational, before-and-after intervention trial. Crit Care Med 2020;48(2):176–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hart JL, Turnbull AE, Oppenheim IM, et al. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 Era. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020;60(2):e93–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hart JL, Taylor SP. Family presence for critically ill patients during a pandemic. Chest 2021;160(2): 549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kentish-Barnes N, Cohen-Solal Z, Morin L, et al. Lived experiences of family members of patients with severe COVID-19 who died in intensive care units in France. JAMA Netw open 2021;4(6): e2113355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moore B Dying during covid-19. Hastings Cent Rep 2020;50(3):13–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morris SE, Moment A, Thomas JD. Caring for bereaved family members during the COVID-19 pandemic: before and after the death of a patient. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020;60(2):e70–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Azad TD, Al-Kawaz MN, Turnbull AE, et al. Corona-virus disease 2019 policy restricting family presence may have delayed end-of-life decisions for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2021;49(10): e1037–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kanaris C Moral distress in the intensive care unit during the pandemic: the burden of dying alone. Intensive Care Med 2021;47(1):141–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cook DJ, Takaoka A, Hoad N, et al. Clinician perspectives on caring for dying patients during the pandemic : a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med 2021;174(4):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rabow MW, Huang CS, White-Hammond GE, et al. Witnesses and Victims both: healthcare workers and grief in the time of COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manag 2021;62(3):647–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, et al. Shared decision making in ICUs: an American college of critical care medicine and American thoracic society policy statement. Crit Care Med 2016;44(1): 188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316(1):51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Randomized trial of communication Facilitators to reduce family distress and intensity of end-of-life care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193(2):154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, et al. A randomized trial of a family-support intervention in intensive care units. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(25):2365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee HW, Park Y, Jang EJ, et al. Intensive care unit length of stay is reduced by protocolized family support intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2019;45(8): 1072–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ten Hoorn S, Elbers PW, Girbes AR, et al. Communicating with conscious and mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care (London, England) 2016;20(1):333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, et al. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med 2002;347(20):1585–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Soto GJ, Martin GS, Gong MN. Healthcare disparities in critical illness. Crit Care Med 2013;41(12): 2784–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cole AP, Nguyen DD, Meirkhanov A, et al. Association of care at minority-serving vs non-minority-serving hospitals with use of palliative care among racial/ethnic minorities with metastatic cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw open 2019;2(2): e187633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chino F, Kamal AH, Leblanc TW, et al. Place of death for patients with cancer in the United States, 1999 through 2015: racial, age, and geographic disparities. Cancer 2018;124(22):4408–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Faigle R, Ziai WC, Urrutia VC, et al. Racial differences in palliative care use after stroke in majority-White, minority-serving, and racially integrated U.S. Hospitals. Crit Care Med 2017;45(12): 2046–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J racial ethnic Health disparities 2018;5(1):117–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, et al. Families with limited English proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted intensive care unit family conferences. Crit Care Med 2009; 37(1):89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(6): 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yarnell CJ, Fu L, Manuel D, et al. Association between immigrant status and end-of-life care in ontario, Canada. JAMA 2017;318(15):1479–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barwise A, Jaramillo C, Novotny P, et al. Differences in code status and end-of-life decision making in patients with limited English proficiency in the intensive care unit. Mayo Clin Proc 2018; 93(9):1271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bazargan M, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Disparities in palliative and hospice care and completion of advance care planning and directives among non-hispanic blacks: a scoping review of recent literature. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38(6): 688–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kross EK, Rosenberg AR, Engelberg RA, et al. Postdoctoral research training in palliative care: Lessons Learned from a T32 program. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020;59(3):750–60.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Starr LT, O’Connor NR, Meghani SH. Improved serious illness communication may help mitigate racial disparities in care among black Americans with COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36(4): 1071–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Starr LT, Ulrich CM, Junker P, et al. Goals-of-Care consultation associated with increased hospice enrollment among propensity-matched cohorts of seriously ill African American and white patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020;60(4):801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(32):3802–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics 2003; 111(1):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cheston CC, Alarcon LN, Martinez JF, et al. Evaluating the Feasibility of incorporating in-person interpreters on family-centered rounds: a QI initiative 2018;8(8):471–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, et al. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Sci Med (1982) 2018;199:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guide to patient and family engagement in hospital quality and safety. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/patients-families/engagingfamilies/guide.html. Accessed July 3, 2021.

- 103.Webster PD, Johnson BH. Developing and sustaining a patient and family advisory council. Institute for Family-Centered Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Majid U The dimensions of tokenism in patient and family engagement: a concept analysis of the literature. J Patient experience 2020;7(6):1610–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hahn DL, Hoffmann AE, Felzien M, et al. Tokenism in patient engagement. Fam Pract 2017;34(3): 290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fiest KM, Sept BG, Stelfox HT. Patients as researchers in adult critical care medicine. Fantasy or reality? Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;17(9): 1047–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Selby JV, Forsythe L, Sox HC. Stakeholder-driven comparative effectiveness research: an update from PCORI. JAMA 2015;314(21):2235–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]