SUMMARY

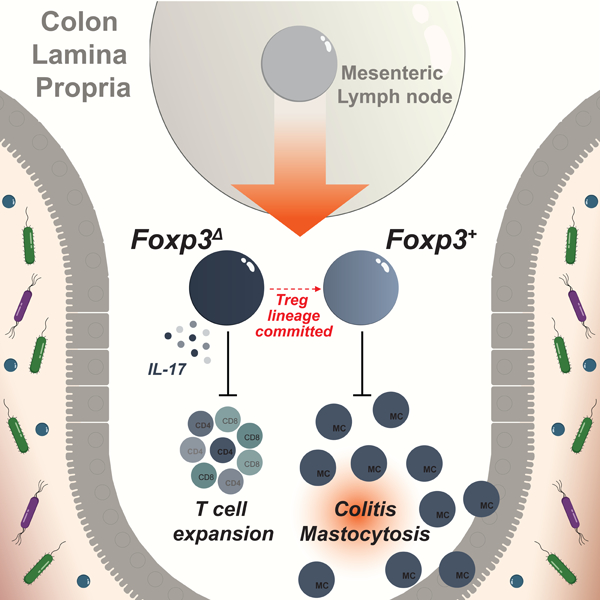

Regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing the transcription factor Foxp3 are an essential suppressive T cell lineage of dual origin: Foxp3 induction in thymocytes and mature CD4+ T cells gives rise to thymic (tTreg) and peripheral (pTreg) Treg cells, respectively. While tTreg cells suppress autoimmunity, pTreg cells enforce tolerance to food and commensal microbiota. However, the role of Foxp3 in pTreg cells and the mechanisms supporting their differentiation remain poorly understood. Here, we used genetic tracing to identify microbiota-induced pTreg cells and found that many of their distinguishing features were Foxp3-independent. Lineage-committed, microbiota-dependent pTreg-like cells persisted in the colon in the absence of Foxp3. While Foxp3 was critical for the suppression of a Th17 cell program, colitis and mastocytosis, pTreg cells suppressed colonic effector T cell expansion in a Foxp3-independent manner. Thus, Foxp3 and the tolerogenic signals that precede and promote its expression independently confer distinct facets of pTreg functionality.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

T cell tolerance is mediated by multiple complementary mechanisms that suppress the generation and activation of self-reactive cells. T cell precursors that receive strong T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation during their development undergo death by negative selection. Autoreactive thymocytes that escape this checkpoint can develop into mature T cells with autoimmune potential. Activation of these cells in the periphery is suppressed by a dedicated population of regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing the X-linked lineage defining transcription factor Foxp3, whose continuous presence is required throughout life to prevent multi-organ autoimmunity (Kim et al., 2007).

Differentiation of Treg cells occurs in the thymus in CD4 single positive (SP) cells receiving moderately strong TCR stimulation in conjunction with interleukin-2 (IL-2) produced by other self-reactive thymocytes (Burchill et al., 2008; Hemmers et al., 2019; Lio and Hsieh, 2008). In addition to this well-described pathway for the generation of thymic Treg (tTreg) cells, a secondary pathway supports the generation of Foxp3+ cells from mature CD4+ T cells in the peripheral lymphoid tissues. While tTreg cells are thought to contribute primarily to the suppression of autoimmunity, peripherally-induced Treg (pTreg) cells are thought to mediate tolerance to food antigens and commensal microbes (Curotto de Lafaille and Lafaille, 2009).

The existence of an extrathymic Treg differentiation pathway was initially suggested by observations in in vitro culture systems in which naïve CD4 T cells can develop into various specialized T helper cell subsets following their activation in the presence of particular cytokines. Activation of CD4 T cell in the presence of TGF-β was shown to induce Foxp3 expression (Chen et al., 2003). Treg cell generation in these cultures was subsequently shown to be closely linked with the differentiation of Foxp3− IL-17-producing Th17 cells, which could be induced by a combination of TGF-β and IL-6 (Bettelli et al., 2006; Veldhoen et al., 2006). Additional studies reported that the Treg vs Th17 cell fate choice was context dependent and could be influenced by environmental signals, including dietary and microbial metabolites such as retinoic acid (RA), short-chain fatty acids and bile acids (Arpaia et al., 2013; Benson et al., 2007; Campbell et al., 2020; Coombes et al., 2007; Furusawa et al., 2013; Hang et al., 2019; Mucida et al., 2007; Schambach et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2013; Song et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2007).

In vivo generation of pTreg cells has been investigated primarily in settings of adoptive T cell transfers, in which TCR transgenic T cells specific for certain food- or microbe-derived antigens can acquire Foxp3 expression (Apostolou and von Boehmer, 2004; Cobbold et al., 2004; Kretschmer et al., 2005; Mucida et al., 2005). Similar to in vitro pTreg differentiation, in vivo Foxp3 induction is dependent on environmental cues and mutually exclusive with the differentiation of Th17 cells. Specific microbes such as Helicobacter hepaticus can trigger the differentiation of anti-inflammatory pTreg cells or pro-inflammatory colitogenic Th17 cells in a context-dependent manner (Chai et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2018). Because pTreg cells are thought to restrain the expansion of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells, their mutually exclusive differentiation in response to overlapping stimuli may provide a means to balance pro- and anti-inflammatory responses to intestinal microbes. However, because methods to unambiguously distinguish pTreg and tTreg cells are still lacking, much uncertainty remains regarding the generalizable mechanisms underlying pTreg differentiation and the distinct physiological functions of these cells.

pTreg and Th17 cells are thought to represent opposing lineages whose differentiation is driven by overlapping sets of transcription factors, including STAT3, RORγt+, and c-Maf (Harris et al., 2007; Ivanov et al., 2006; Neumann et al., 2019; Ohnmacht et al., 2015; Sefik et al., 2015; Wheaton et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2018). While Foxp3 defines the pTreg lineage, its role in shaping the transcriptional and functional features of these cells is unclear. On the one hand, Foxp3 induction at a critical differentiation branch point may enforce a pTreg fate in cells that would otherwise default to a pro-inflammatory Th17 cell lineage. On the other hand, Foxp3 may also be part of a larger tolerogenic program induced by the upstream environmental signals that precede and promote its expression.

To gain insights into the role of Foxp3 in pTreg cells, we devised a genetic labeling strategy to track de novo Foxp3 induction in response to microbial colonization and dietary antigens. We found that transcriptional features of newly differentiated pTreg cells are induced in a Foxp3-independent manner and that Foxp3 was dispensable for the lineage commitment of microbiota-dependent pTreg cells. While Foxp3 was critical for the suppression of a Th17 effector program, colitis and rampant mastocytosis, Foxp3-deficient cells efficiently suppressed colonic T cell expansion. Thus, rather than defining a branch point in the differentiation of cells with pro- and anti-inflammatory functions, peripheral induction of Foxp3 confers a distinct set of regulatory features complementary to those imprinted by the upstream signals that precede or promote its expression.

RESULTS

Genetic labeling enables identification of polyclonal pTreg cells

To address the role of Foxp3 in pTreg cells, we first sought to define the transcriptional changes that coincide with its expression using a genetic model to trace extrathymic Foxp3 induction in response to microbial colonization. In Foxp3DTR-GFP/wtCD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice, tamoxifen-induced CreER mediated activation of the Rosa26lsl-tdTomato recombination reporter allele resulted in fluorescent labeling of CD4+ thymocytes and peripheral CD4 T cell (Figure S1A). Due to random X-inactivation, approximately half of the Treg cells in female mice expressed a wild-type Foxp3 allele while the other half expressed a Foxp3GFP-DTR allele encoding a GFP-diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) fusion protein (Figure S1B). To label only extrathymic Foxp3-negative cells, mice were treated with DT over a three-week period following tamoxifen administration to allow maturation of tdTomato+ thymocytes while concomitantly ablating GFP+ Treg cells (Figure S1C). This resulted in the selective labeling of peripheral Foxp3− CD4 T cells carrying a Foxp3DTR-GFP allele, in which stimulation-induced Foxp3 expression could be measured following the cessation of DT treatment (Figure 1A, S1D,E). Introduction of a wild-type Foxp3Thy1.1 reporter allele in Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice further enabled a direct comparison between stimulation-induced pTreg cells and other Treg populations in the same mice (Figure 1A).

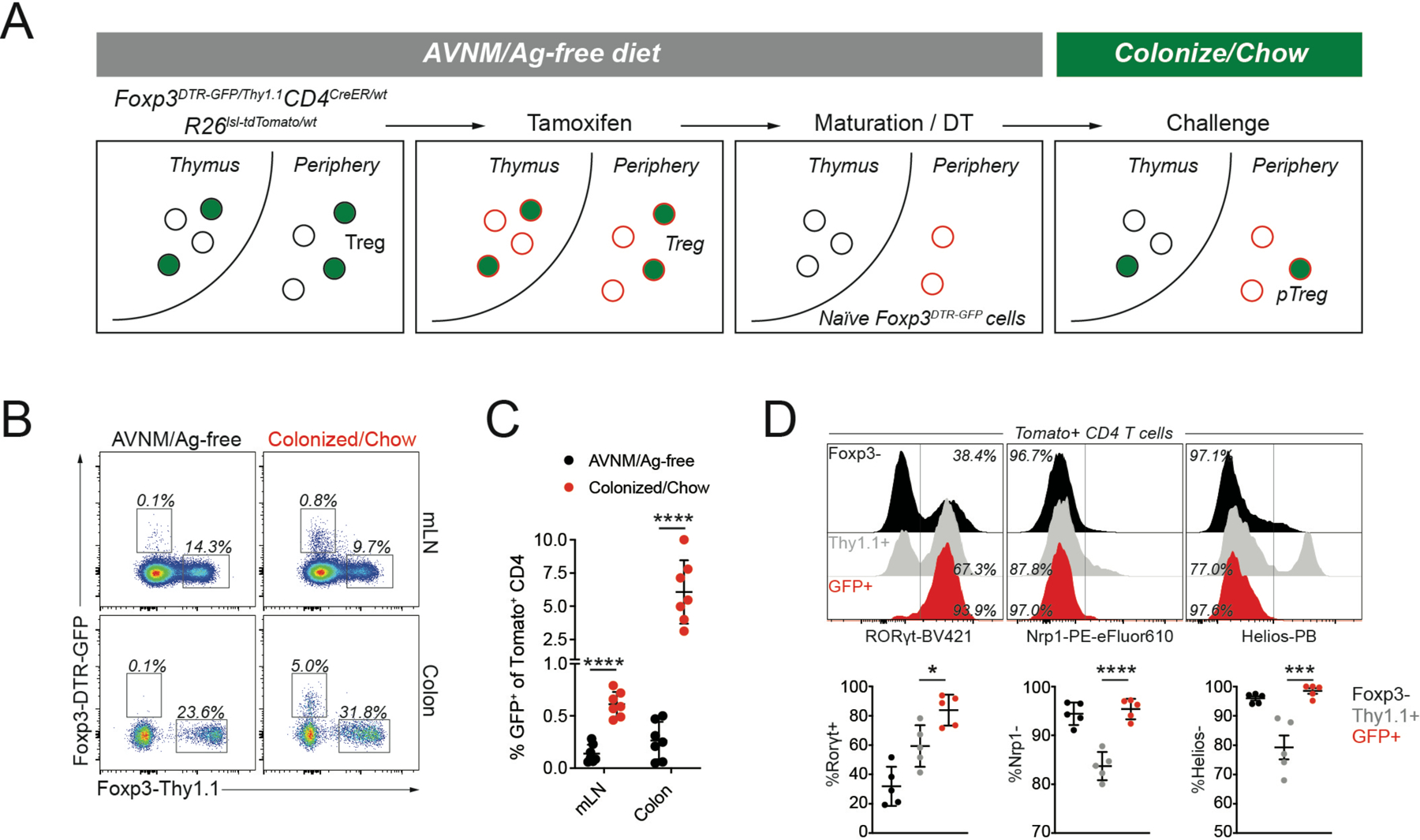

Figure 1: Genetic labeling enables identification of extrathymically generated Treg cells.

A) female Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice were bred and weaned on antibiotic-containing drinking water (AVNM) and an amino acid-based diet (Ag-free diet). To label CD4 T cells, mice were treated with tamoxifen by oral gavage. tdTomato+ thymocytes were allowed to mature for at least two weeks post-tamoxifen treatment, while depleting DTR-GFP expressing Treg cells using diphtheria toxin (DT) administration. The resulting animals contained tdTomato+ naïve CD4 T cells carrying an unexpressed Foxp3DTR-GFP allele, activation of which can be measured in response to microbial colonization and a dietary switch. B-C) Flow cytometry of tdTomato+ cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN) and colonic lamina propria (LP) of fate-mapped mice two weeks after microbial colonization and dietary switch or maintenance on AVNM and ag-free food. Pooled data from two independent experiments (n=7 mice per group). P-values from multiple t-tests: mLN (p=3.91e-6), LP (p=6.34e-4). D) Expression of Rorγt, Nrp1, and Helios in sorted tdTomato+ cells from LP. Pooled data from two independent experiments (n=5 mice per group).*:p<0.05; ***:p<0.001;****:p<0.0001, by one-way ANOVA. See also Figure S1.

To induce synchronized differentiation of intestinal pTreg cells, breeders and their Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt offspring were administered a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail (AVNM) and an antigen-free (Ag-free) diet which was continued throughout the labeling procedure. Introduction of a complex microbiota by oral gavage with a specific pathogen-free (SPF) fecal slurry and a concomitant switch to a conventional chow diet induced Foxp3 (GFP) expression in ~5% of tdTomato+ CD4 T cells in the colonic lamina propria, while mice maintained on AVNM and an Ag-free diet showed negligible background induction (Figure 1B,C). The resulting colonic GFP+ tdTomato+ CD4 T cells were almost universally RORγt+Nrp1−Helios− in agreement with previously reported features of pTreg cells defined in TCR-transgenic systems (Figure 1D) (Thornton et al., 2010; Weiss et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2018; Yadav et al., 2012). Other potentially tolerogenic challenges, including H. polygyrus infection, allogeneic pregnancy, and orthotopic tumor transplantation did not result in measurable de novo pTreg cell generation, suggesting that pronounced and synchronized extrathymic Foxp3 induction occurred specifically in response to microbial colonization and a dietary switch (Figure S1F-L).

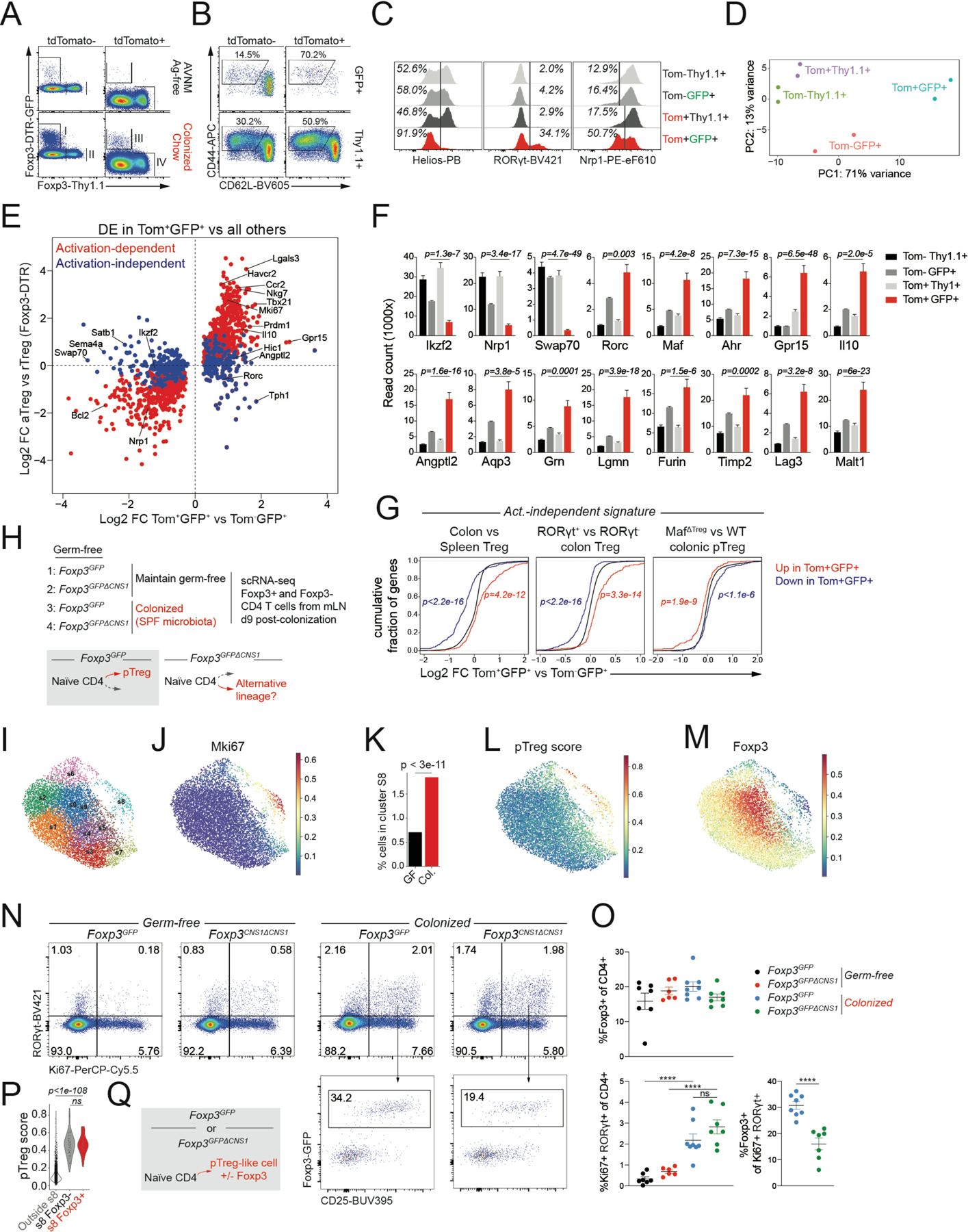

A pTreg transcriptional program is induced independently of FoxP3

To define the transcriptional features of differentiating pTreg cells we isolated tdTomato+GFP+, tdTomato−GFP+, tdTomato+Thy1.1+, and tdTomato−Thy1.1+ CD4 T cells from the mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN) of “pTreg fate-mapped” Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice 10 days after microbial colonization (Figure S2A-B). The newly differentiated tdTomato+GFP+ pTreg cells in the mLN were enriched for RORγt+Nrp1−Helios− cells and predominantly CD44hiCD62Llow, consistent with their recent activation (Figure 2A-C). Conversely, tdTomato−GFP+ cells that recently acquired Foxp3 expression following the cessation of DT treatment were largely CD44lowCD62Lhi, suggesting that this population consisted mostly of newly generated “naïve” tTreg cells. Control populations of tdTomato−Thy1.1+ and tdTomato+Thy1.1+ cells expressing the wild-type Foxp3Thy1.1 allele were predominantly RORγt−Nrp1+ and composed of a mix of CD44lowCD62Lhi and CD44hiCD62Llow cells. RNA-seq analyses of these subsets revealed a pTreg specific gene expression program, including reduced expression of Nrp1, Ikzf2, and Swap70, and increased expression of Rorc, Maf, Ahr, Il10, and the barrier tissue homing receptor encoding Gpr15 gene (Figure 2D-F). Some of the transcriptional features of pTreg cells could also be induced in Treg cells activated in response to autoimmune inflammation, while others were activation-independent (Figure 2E) (Arvey et al., 2014). A comparison with published datasets revealed that this activation-independent pTreg signature was also present in colonic vs. splenic Treg cells, in particular the RORγt+ fraction, and was partially dependent on the transcription factor c-Maf (Figure 2G) (Sefik et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2018). These observations suggest that pTreg cells acquire features of colonic RORγt+ Nrp1−Helios− Treg cells during the earliest stages of their differentiation in the mLN.

Figure 2: A pTreg transcriptional program is induced independently of Foxp3.

A) female Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice were bred and weaned on antibiotic-containing drinking water and Ag-free diet. After labeling of extrathymic CD4 T cells, mice were switched to chow diet and colonized with SPF fecal microbiota. 12 days post-colonization indicated populations were isolated by flow cytometry for RNA-seq. B-C) Expression of activation markers and putative pTreg markers on isolated populations. D) PCA plot of RNA-seq samples. E) RNA-seq showing genes differentially expressed (DE) between GFP+Tom+ and all other sorted Treg populations. Activation-dependent and -independent gene expression changes were defined using a comparison to genes DE in activated Treg (aTreg) cells isolated from secondary lymphoid tissues of male Foxp3DTR-GFP/y mice 11 days following transient DT-induced Treg cell depletion vs resting Treg (rTreg) cells from untreated controls. F) Expression of select genes. P-values from DEseq2, comparing Tom+GFP+ to Tom−GFP+ G) Expression changes in activation-independent pTreg signature genes in published datasets. P-values from one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test comparing red and blue distributions to the background distribution in black H) Experimental design. Germ-free (GF) male Foxp3GFP and Foxp3GFPΔCNS1 mice were colonized with SPF fecal microbiota or kept GF. A 50%−50% mix of GFP+ and GFP− CD4 T cells sorted from pooled mLN of 3 mice per group was used as input for scRNA-seq. I) UMAP of scRNA-seq data showing PhenoGraph clusters. Activated T cells and Treg cells are included in the plot (see Figure S4). J) Imputed Mki67 expression. K) Percentage of cells from GF or colonized (Col.) samples belonging to cluster s8 (hypergeometric test). L) Expression of the pTreg gene expression signature derived from fate-mapping experiment. M) Imputed Foxp3 expression. N-O) Flow cytometry of mLN CD4 T cells. Pooled data from 2 independent experiments with 6–8 mice per group total (****:p<0.0001, by one-way ANOVA or unpaired t test). P) pTreg gene expression signature in the indicated cell subsets. P-value from Mann-Whitney U test Q) Transcriptionally similar pTreg-like cells arise in response to microbial colonization in the presence or absence of Foxp3. See also Figures S2 and S3.

We next sought to dissect the role of Foxp3 in the early differentiation of microbiota-induced pTreg cells. We asked whether Foxp3 expression defined a developmental branch point and whether cells that failed to induce Foxp3 would differentiate into an alternative lineage. To address these questions, we made use of Foxp3GFPΔCNS1 mice in which extrathymic Foxp3 induction is selectively impaired by the deletion of a Foxp3 intronic enhancer element, CNS1 (Zheng et al., 2010). We reasoned that under conditions supporting pTreg cell differentiation in wild-type cells, CNS1-deficient T cells would give rise to an alternative lineage (Figure 2H). To define the CD4 T cell response to microbial colonization in an unbiased manner, we performed single cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) of Foxp3+ and Foxp3−CD4 T cells isolated from the mLN of conventionalized or control germ-free (GF) Foxp3GFP and Foxp3GFPΔCNS1 mice on day 9 post-colonization (Figure 2H, S3A). We first identified Treg cells and cells that responded to microbial colonization as clusters in which T cell activation and proliferation-associated transcripts or Foxp3 were highly expressed (Figure S3B-C). Re-clustering of these cells revealed a proliferative subset (cluster s8) whose relative size was increased upon microbial colonization (Figure 2J-K). This population preferentially expressed the pTreg transcriptional signature, defined in our fate-mapping experiments (Figure 2L, S4D-E). Although Foxp3 expression in cluster s8 was partially dependent on CNS1, its transcript levels were generally lower than in other Treg cell clusters, suggesting that only few of these cells expressed Foxp3 at the time of analysis. (Figure 2M, S3F-H). Flow cytometric analysis of mLN CD4 T cells from colonized or GF Foxp3GFP and Foxp3GFPΔCNS1 mice further confirmed the presence of a microbiota-dependent population of Ki67+RORγt+ cells, only a minority of which expressed Foxp3 in a CNS1-dependent manner (Figure 2N-O). Thus, microbial colonization led to the appearance of pTreg-like cells, many of which did not express Foxp3.

To determine the transcriptional changes associated with Foxp3 induction in pTreg cells, we next compared cells from cluster s8 with and without detectable Foxp3 mRNA. These populations differentially expressed a limited number of genes, including Foxp3-dependent transcripts such as Il2ra, Ctla4, Itgae, Lrrc32 and Tcf7 (Figure S3I) (van der Veeken et al., 2020). However, both Foxp3+ and Foxp3− subsets similarly expressed the pTreg transcriptional signature, suggesting that it was induced prior to, or together with, rather than downstream of Foxp3 (Figure 2P). These observations suggest that CNS1-dependent expression of Foxp3 coincides with or follows the induction of a Foxp3-independent pTreg signature (Figure 2Q).

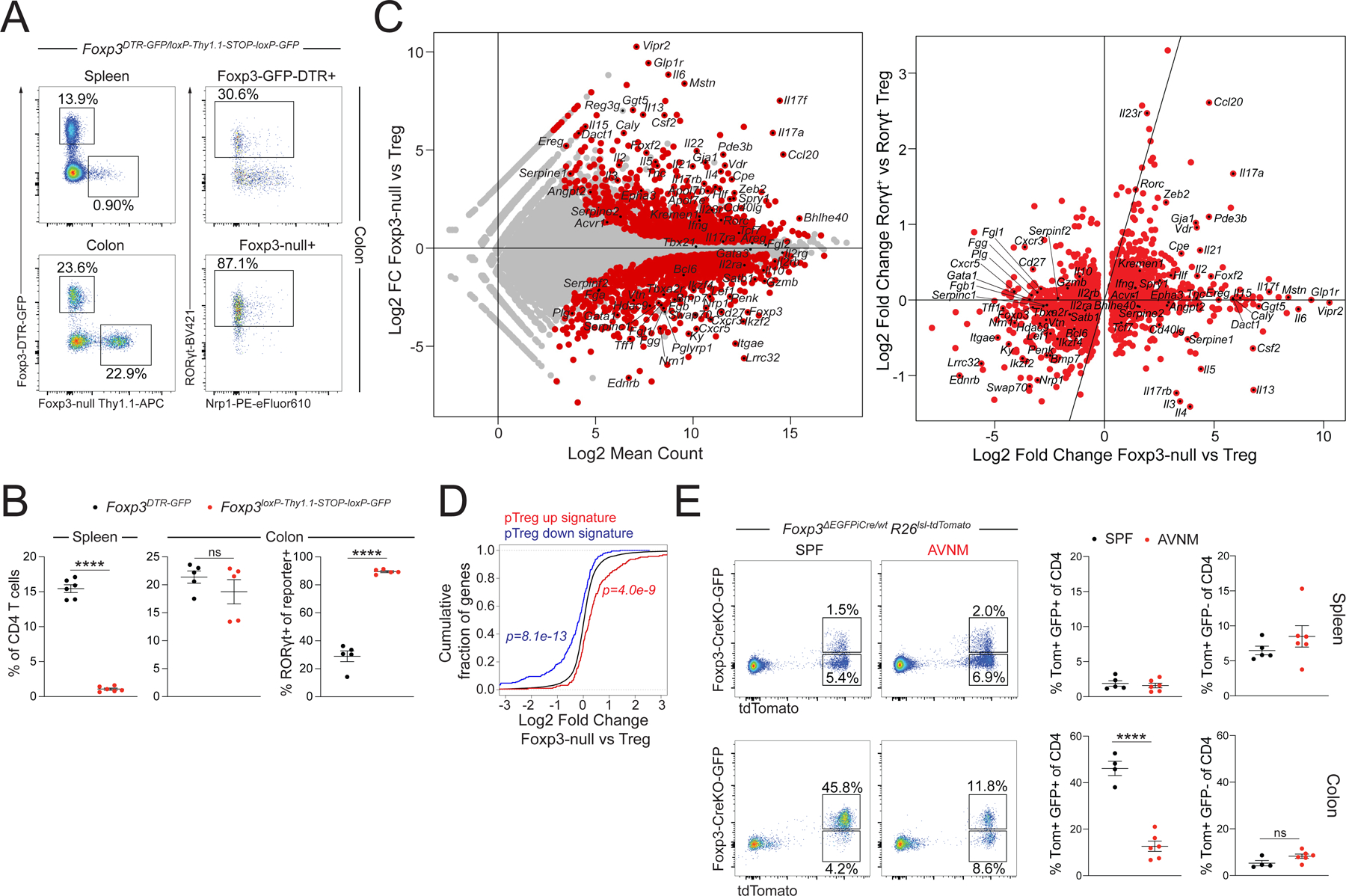

Foxp3 is dispensable for pTreg lineage commitment

To further assess the downstream requirements for Foxp3 in pTreg differentiation, we characterized the effects of Foxp3-deficiency on Treg cell populations in the colonic lamina propria. Here, we analyzed mosaic Foxp3loxP-Thy1.1-STOP-loxP-GFP/DTR-GFP female mice, in which Foxp3 expression in half of the cells is prevented by insertion of a Thy1.1 reporter gene and a STOP cassette upstream of the Foxp3 coding sequence, while expression of a functional Foxp3DTR-GFP allele is enabled in the other half (Hu et al., 2021). Consistent with previous observations, Foxp3 reporter-null cells were severely outcompeted by wild-type Treg cells in the secondary lymphoid organs of heterozygous female mice (Gavin et al., 2007). In contrast, colonic RORγt+ Nrp1− reporter-null cells maintained competitive fitness and were present at comparable frequencies as wild-type Treg cells (Figure 3A-B). RNA-seq analysis of GFP+ Treg cells and Thy1.1+ reporter-null cells from the colonic lamina propria revealed a number of Foxp3-induced transcriptional features, including higher expression of Lrrc32, Itgae, and Nrn1, and lower expression of Il17a, Il17f, and Ccl20 (Figure 3C). However, the pTreg transcriptional program defined in our fate-mapping experiments was still preferentially expressed in reporter-null cells compared to wild-type GFP+ Treg cells, suggesting that many of the transcriptional changes induced early during pTreg differentiation can be maintained even in the absence of Foxp3 (Figure 3D).

Figure 3: Foxp3 is dispensable for lineage commitment of microbiota-dependent pTreg cells.

A-B) Flow cytometry of CD4 T cells from spleen and colonic lamina propria (LP) of female Foxp3DTR-GFP/loxp-Thy1.1-STOP-loxp-GFP mice. Showing one of two independent experiments with 5–6 mice per group each. P-values from paired t-test (****:p<0.0001). C) RNA-seq of DTR-GFP+ wild-type Treg cells and Thy1.1+ reporter-null cells from the LP of female Foxp3DTR-GFP/loxp-Thy1.1-STOP-loxp-GFP mice (left). Comparison with published dataset of colonic RORγt+ vs RORγt− colonic Treg cells (right). D) Differential expression of the pTreg transcriptional signature by LP Treg cells and Foxp3 reporter-null cells. P-values from one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test comparing red and blue distributions to the background distribution in black. E) Flow cytometry of splenic (top) and LP (bottom) CD4 T cells from female Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/wtR26lsl-tdTomato mice maintained on antibiotic-containing or regular drinking water (SPF) for one month. Pooled data from two independent experiments with n=4 or n=6 mice per group. P-value from unpaired t-test (***:p<0.0001).

To determine if colonic Foxp3 reporter-null cells were stably committed to the Treg lineage we analyzed heterozygous female Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice in which Cre recombinase encoded by a Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre reporter-null allele enables irreversible labeling of cells that transiently expressed the reporter-null allele before diverting to another lineage (Charbonnier et al., 2019). While we identified a substantial population of tdTomato+GFP− cells that had transiently expressed Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre in the spleens of these mice, the vast majority of colonic tdTomato+ cells in SPF mice were also GFP+, suggesting that even in the absence of Foxp3, these cells were committed to the Treg lineage (Figure 3E). Although colonic Foxp3 reporter-null cells were dependent on the microbiota for their generation or maintenance, antibiotic treatment did not cause a significant expansion of tdTomato+GFP− cells (Figure 3E). Together, these observations suggest that microbiota-dependent pTreg cells do not require Foxp3 for their lineage commitment.

Treg-committed Th17 cells differentiate in the absence of Foxp3

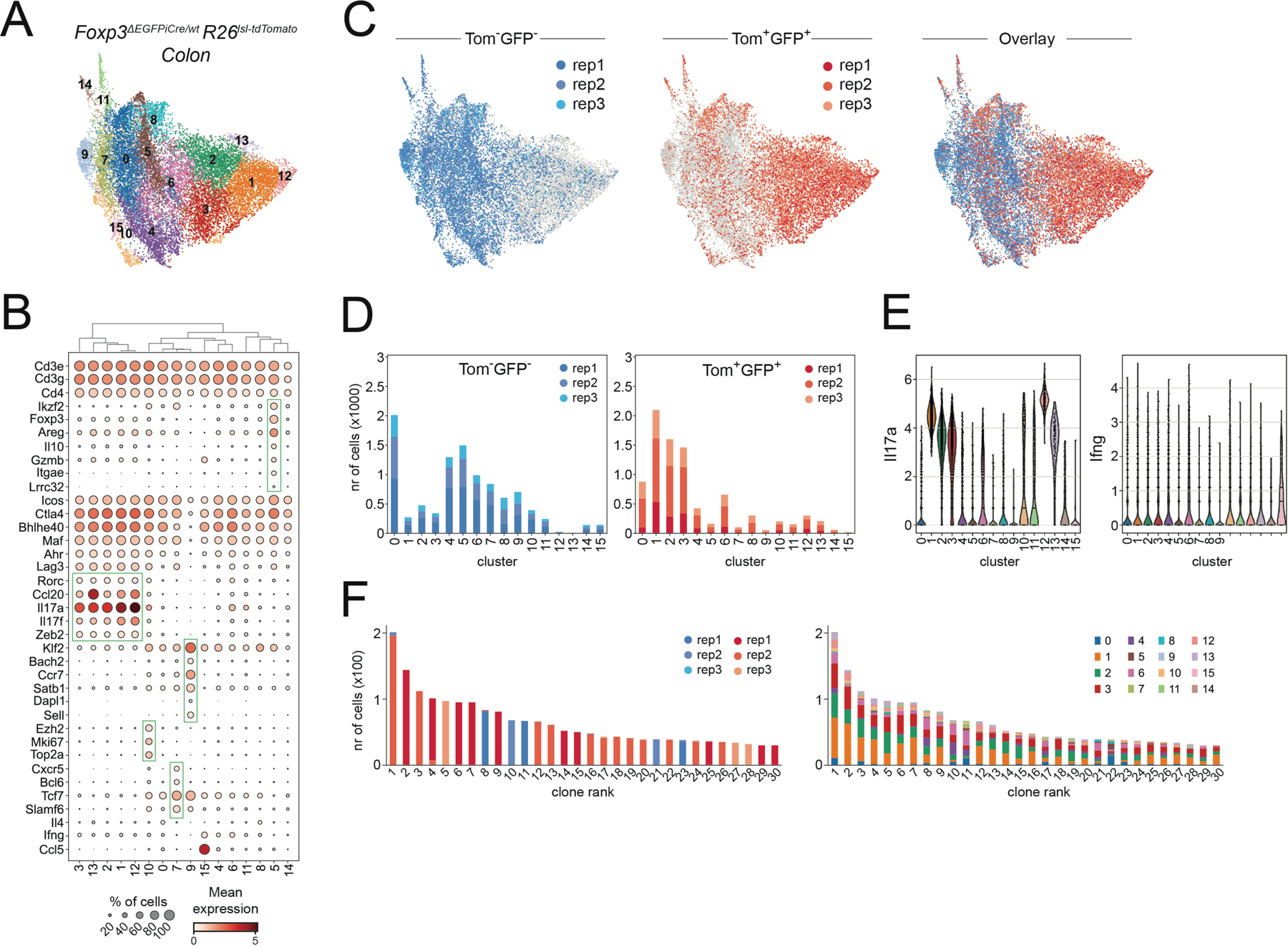

Despite their commitment to the Treg lineage, Foxp3 reporter-null cells could also be classified as Th17 cells based on their high expression of Il17a and Il17f. It was also possible that these cells acquired a “hybrid” state, combining features of both Treg and Th17 cells. To characterize their transcriptional program, we performed scRNA-seq analysis of tdTomato+GFP+ and tdTomato−GFP− CD4 T cells from the colonic lamina propria of heterozygous female Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice. This analysis revealed multiple transcriptionally distinct clusters of colonic CD4 T cells, including cells with Th1, Th2, Th17, Tfh, and Treg cell features (Figure 4A-B). While tdTomato+GFP+ reporter-null cells occupied multiple clusters, these cells were rarely found in Treg cell cluster 5 and instead, predominantly fell within the Il17a+Ifng− clusters 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 4C-E, S4A). TCR repertoire analysis further suggested that the cells occupying these three clusters frequently arose from the same T cell clone (Figure 4F).

Figure 4: Treg-committed Th17 cells differentiate in the absence of Foxp3.

A) UMAP of scRNA-seq data showing PhenoGraph clusters of tdTomato+GFP+ reporter-null cells and tdTomato−GFP− bulk CD4 T cells isolated from the colonic lamina propria of three female Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice. B) Expression of select marker genes by cells occupying distinct PhenoGraph clusters. C-D) UMAP and PhenoGraph cluster composition of scRNA-seq data for individual replicates of tdTomato+GFP+ reporter-null cells and tdTomato−GFP− bulk CD4 T cells. E) Il17a and Ifng expression by cells from distinct PhenoGraph clusters. F) Sample origin (left) and PhenoGraph cluster composition (right) of cells from the 30 largest TCR clonotypes. See also Figure S4.

Importantly, while a very minor fraction of tdTomato+GFP+ cells in clusters 12 and 13 acquired a distinct transcriptional state that was not shared by tdTomato−GFP− cells, the vast majority of Foxp3 reporter-null cells occupied clusters that were also populated by tdTomato−GFP− CD4 T cells from the same mice (Figure 4D). Thus, most Foxp3 reporter null cells acquired a transcriptional state that was characteristic of Th17 cells. These data suggest that in the absence of Foxp3 protein, pTreg precursors typically differentiate into Th17 cells but nevertheless remain committed to the Treg lineage based on their stable Foxp3 reporter-null gene expression.

Foxp3-dependent and independent functions of pTreg cells

Although Foxp3 reporter-null cells were transcriptionally similar to Th17 cells, this did not immediately imply pro-inflammatory functions. Intestinal Th17 cells are functionally heterogeneous and can retain considerable differentiation potential. Pathogen-induced Th17 cells can produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ, while commensal-induced “homeostatic” or “non-pathogenic” Th17 cells are thought to support tissue function in a non-inflammatory manner through mechanisms that are still poorly defined (Gaublomme et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2012; Omenetti et al., 2019). Additionally, a population of stem-like Tcf7+ Slamf6+ Th17 cells can provide a reservoir for the differentiation of pathogenic Th17 cells (Schnell et al., 2021). Our scRNA-seq analysis suggested that colonic Foxp3-reporter null cells were primarily Il17a+Ifng−Tcf7−Slamf6−, most closely resembling “homeostatic” Th17 cells (Figure S4A). Nevertheless, it remained possible that these cells would acquire pathogenic functions and promote pathology in inflammatory settings.

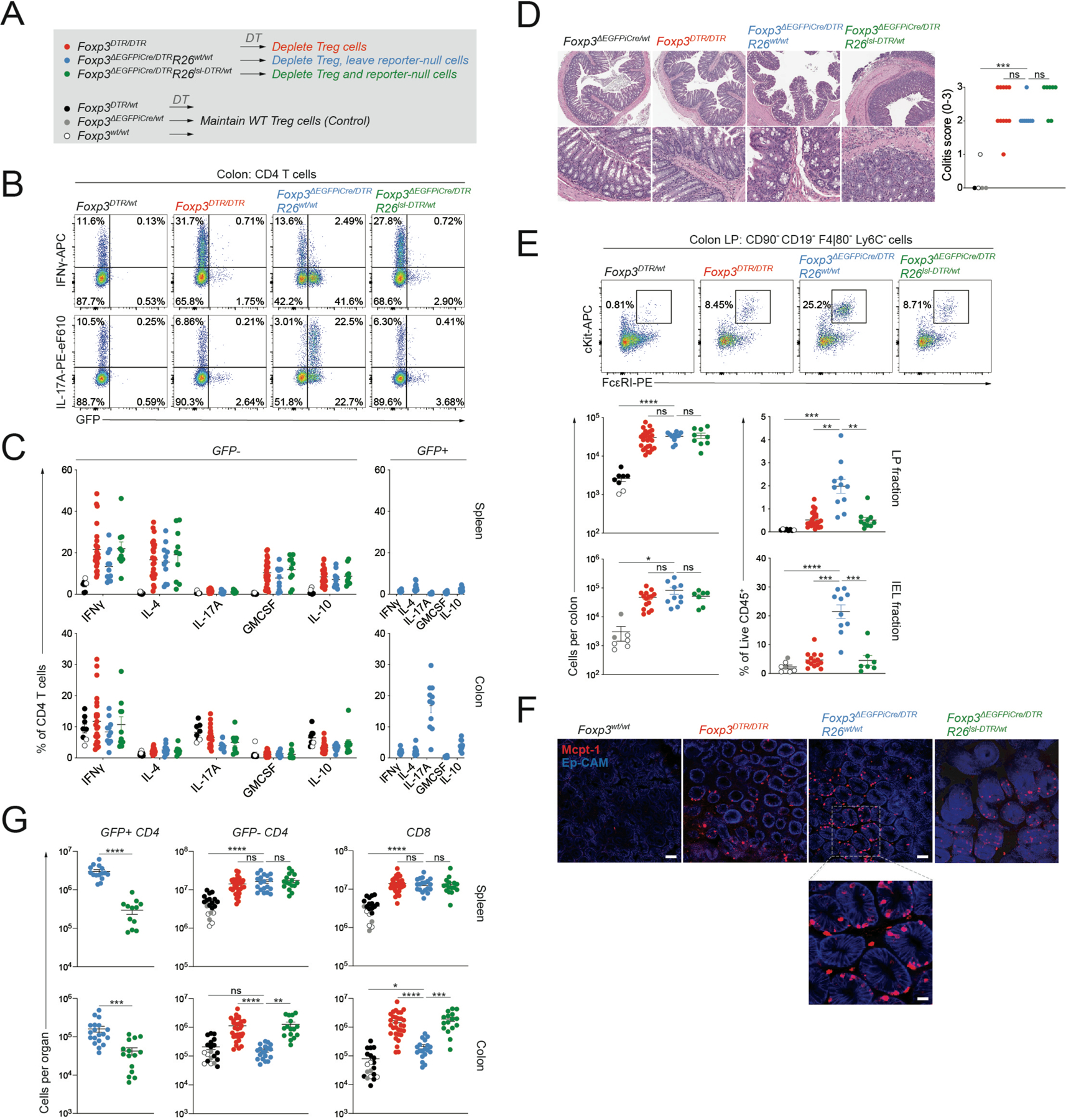

To determine whether Foxp3 reporter-null cells had pro- or anti-inflammatory properties in a setting where suppression by wild-type Treg cells was lifted, we analyzed female Foxp3DTR/DTR, Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/DTRR26wt/wt, and Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/DTRR26lsl-DTR/wt mice, in which DT-treatment induces the ablation of all Treg cells, Treg cells but not reporter-null cells, and both Treg cells and reporter-null cells, respectively (Figure 5A). Foxp3 reporter-null cells that were selectively maintained in the colonic lamina propria of Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/DTR mice after DT treatment produced high amounts of IL-17A, but not IFNγ, upon in vitro re-stimulation (Figure 5B-C). Nevertheless, compared to DT treated Foxp3wt/wt, Foxp3DTR/wt, or Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/wt control mice in which wild-type Treg cells were maintained, mice in all three experimental groups showed pronounced histological features of colitis (Figure 5D). Disease in Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/DTR mice was associated with a selective expansion of intestinal mast cells, but not neutrophils or eosinophils (Figure 5E-F, S5A-B). These observations are consistent with previously observed mast cell expansion in recently colonized Foxp3GFPΔCNS1 mice and suggest that Foxp3 expression in pTreg cells is critical for the suppression of intestinal mastocytosis (Campbell et al., 2018). In contrast, Foxp3 reporter-null cells were sufficient to restrain effector CD4 and CD8 T cell expansion in the colonic lamina propria of DT-treated Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/DTRR26wt/wt mice and this control was lost in Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre/DTRR26lsl-DTR/wt mice in which reporter-null cells were ablated (Figure 5G). Foxp3 reporter-null cells exerted no effect on T cell expansion in the spleen, consistent with the previously reported Foxp3-dependence of tTreg suppressor function (Figure 5G). Thus, although Foxp3-reporter null cells on their own could not prevent colitis, they were capable of efficiently suppressing colonic T cell expansion in the absence of wild-type Treg cells.

Figure 5: Colonic Treg cells have Foxp3-dependent and -independent suppressive functions.

A) Experimental design. Female mice of indicated genotypes were treated with DT (1μg via intraperitoneal injection on d0, d1, and d7) and analyzed two weeks after the start of treatment. B-C) Intracellular cytokine staining following 3-hour ex vivo re-stimulation. Pooled data from 4 experiments with n=8 to 25 mice per group. D: H&E staining of colonic sections from indicated genotypes and colitis scores (0–3). Pooled data from two independent experiments with n=5 to 11 mice per group. E: flow cytometry of mast cells in the colonic lamina propria (LP) and intraepithelial (IEL) fractions. Pooled data from 4 (LP) or 3 (IEL) independent experiments with n=8 to 25 mice per group (LP) or n=7 to 15 mice per group (IEL). F: Representative whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF) images of the proximal colon of mice of the indicated genotypes stained with anti-Mcpt1 (red) and anti-Ep-Cam (blue). Scale bars, 50μm. Scale bar of inset below, 10μm. G: Total CD4 and CD8 T cell counts in the spleen and colonic LP analyzed by flow cytometry. Pooled data from 8 experiments with n=16 to 31 mice per group. P-values from Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA (*:p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, ****: p<0.0001). See also Figure S5.

DISCUSSION

Here, we used a combination of genetic tools to characterize the transcriptional features of newly differentiated pTregs and the role of Foxp3 in these cells. Although putative pTreg markers were previously identified using adoptive transfer-based systems, their utility has remained uncertain as tTreg cells can acquire a similar pattern of marker expression under permissive conditions (Gottschalk et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2017; Szurek et al., 2015). Our genetic labeling approach provides a broadly applicable strategy for the unbiased identification of newly generated pTreg cells without the use of a priori defined markers.

Importantly, while we failed to detect pronounced pTreg cell differentiation in response to H. polygyrus infection, allogeneic pregnancy, and orthotopic lung tumor transplantation, we do not rule out the possibility that pTreg cells are generated in these and other settings and may be phenotypically and functionally distinct from those arising in response to microbial colonization. In support of this notion, one study showed that in contrast to their microbiota-induced colonic counterparts, dietary antigen-induced Treg cells in the small intestine were predominantly RORγt− (Kim et al., 2016). Similarly, pTreg cell differentiation from Helicobacter-reactive TCR transgenic T cells was shown to be more efficient in weaning-age mice compared to newborns or adults; however, whether polyclonal pTreg cells generated at different stages of life are transcriptionally or functionally distinct remains to be determined (Nutsch et al., 2016).

Using scRNA-seq, we found that Foxp3+ pTreg and Foxp3−RORγt+ Th17 cells arising in the mLN upon microbial colonization were closely related and shared a transcriptional signature. While we did identify a number of transcriptional changes associated with the induction of Foxp3, newly differentiating pTreg and Th17 cells appeared more similar to each other than to other cells present in the mLN at the same time. Thus, rather than defining an immediate transcriptional branch point between pTreg and Th17 lineages, Foxp3 expression coincides with or temporally follows the induction of a Foxp3-independent program.

We found that colonic Foxp3 reporter-null cells were almost uniformly RORγt+, microbiota-dependent, and closely resembled wild-type Th17 cells. These cells remained committed to the Treg lineage, as evidenced by the stable expression of the Foxp3 reporter-null allele. These observations are consistent with several recent studies. First, ~15% of colonic RORγt+ Treg cells have a history of Il17a expression, suggesting that some IL-17-producing cells retain the capacity to later induce Foxp3 (Pratama et al., 2020). Second, it was found that Foxp3 CNS1 deficiency only delays, but does not abrogate, peripheral Foxp3 induction in a TCR transgenic system (Nutsch et al., 2016). Together, these observations argue that even in the absence of Foxp3 protein, Foxp3 expression in colonic pTreg cells is continuously enforced by cell intrinsic or extrinsic cues. While the nature of these signals remains unknown, TGF-β, STAT3-activating cytokines, c-Maf, and other transcription factors implicated in pTreg cell differentiation are likely candidates. Importantly, despite their global transcriptional similarity, specific differences in gene expression, TCR specificity, or tissue localization may distinguish Foxp3 reporter-null cells from Th17 cells and underlie their continuous induction of Foxp3 expression.

Foxp3 expression by colonic Treg cells was required to prevent histological signs of colitis and the expansion of intestinal mast cells. Pathology and mast cell expansion were equally evident in mice in which Foxp3 reporter-null cells were ablated, suggesting that this phenotype was due to a loss, rather than a gain of functionality by Foxp3-deficient cells. These observations are consistent with the observed mast cell expansion in recently colonized Foxp3GFPΔCNS1 mice and suggest a previously unappreciated link between pTreg and mast cells (Campbell et al., 2018). While the physiological functions of mast cells remain enigmatic, their activity has been implicated in irritable bowel syndrome and food antigen-induced visceral pain signaling (Aguilera-Lizarraga et al., 2021).

Despite lacking Foxp3, colonic Foxp3 reporter-null cells still exerted immunoregulatory functions, as their presence was sufficient to prevent the immediate expansion of effector CD4 and CD8 T cells when wild-type Treg cells were ablated. The mechanisms through which this suppression is achieved are still unclear and possibly distinct from those employed by bona-fide pTreg cells. Reporter-null cell-derived IL-17A, IL17F, and IL-22 could conceivably dampen T cell expansion indirectly by enhancing barrier integrity and limiting microbial exposure in the absence of Treg cell mediated tolerance. However, it is also possible that pTreg and reporter-null cells both utilize the same Foxp3-independent mechanisms to suppress T cell expansion.

Together, our work sheds light on the role of Foxp3 in pTreg cell differentiation and provides a new perspective on the relationship between colonic pTreg and Th17 cells. We found that Foxp3 confers a distinct set of regulatory features complementary to those imprinted by the upstream signals that precede or promote its expression. In the absence of functional Foxp3 protein, reporter-null cells acquired transcriptional features of Th17 cells but remained committed to the Treg lineage and capable of suppressing T cell expansion. Thus, while previous work suggested that pTreg and Th17 lineages represent mutually antagonistic fates with opposing functions, our observations argue that pTreg and “homeostatic” Th17 cells are developmentally and functionally closely related. We hypothesize that mechanisms supporting peripheral induction of Foxp3 expression may have evolved to refine the immunomodulatory and tissue supportive functions of “homeostatic” Th17 cells in a gradual acquisition of tolerogenic properties.

Limitations of Study

Successful genetic labeling of pTreg cells relies on the synchronized differentiation of a sizeable population of cells in response to an acute challenge. The differentiation of tagged pTreg cells occurs in a lymphoreplete environment where untagged pTreg and tTreg cells compete for the same niche. pTreg cells are likely to leave the lymph node and migrate into non-lymphoid tissues shortly after their generation. This makes it difficult to capture pTreg cell induction in response to relatively slow, asynchronized stimuli such as the gradual exposure to commensals and dietary antigens during early life.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY:

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Alexander Y Rudensky (rudenska@mskcc.org).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

scRNA/TCR-seq and bulk RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO under accession numbers GSE176237, GSE176293 and GSE193780 and are publicly available as of the date of publication.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL & SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

Animals were housed at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) animal facility under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions on a 12-hour light/dark cycle under ambient conditions with free access to food and water. All studies were performed under protocol 08–10-023 and approved by the MSKCC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice used in this study had no previous history of experimentation or exposure to drugs. Foxp3DTR-GFP, CD4CreER, Rosa26lsl-tdTomato, Foxp3Thy1.1, Foxp3GFP, Foxp3GFP∆CNS, Foxp3ΔEGFPiCre, Rosa26lsl-DTR, Foxp3GFPKO and Foxp3loxP-Thy1.1-STOP-loxP-GFP mice were previously described (Buch et al., 2005; Charbonnier et al., 2019; Fontenot et al., 2005; Gavin et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2007; Liston et al., 2008; Madisen et al., 2010; Sledzińska et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2010). SPRET/EiJ mice were purchased from Jax. Adult (>6 weeks old) male and female mice were used for experiments as indicated in the figure legends.

Maintenance and colonization of germ-free mice

Germ-free Foxp3GFP∆CNS1 and Foxp3GFP mice (Campbell et al., 2018) were maintained in flexible isolators (Class Biologically Clean; USA) at Weill Cornell Medicine and fed with autoclaved 5KA1 chow. GF status was routinely checked by aerobic and anaerobic cultures of fecal samples for bacteria and fungi and by PCR of fecal DNA samples for bacterial 16S and fungal/yeast 18S genes. Mice were colonized with SPF microbiota by oral gavage with a fecal microbiota slurry in PBS.

METHOD DETAILS

Antibiotic treatment and amino acid-defined diet

To deplete microbiota, mice received Ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich Cat #A0166–5G; 0.5g/l), Vancomycin Hydrochloride (Fresenius-Kabi Cat #C314061; 0.5g/l), Neomycin (Sigma-Aldrich Cat #N6386–100G; 0.5g/l), and Metronidazole (Sigma-Aldrich Cat #M1547–25G; 0.5g/l) in sucralose-containing drinking water. Mice received either regular chow diet (LabDiet 5058 or 5053 for breeders or non-breeders, respectively) or an amino acid-defined diet (Teklad TD.140088).

Fate-mapping of extrathymic Foxp3-induction

Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt or Foxp3DTR-GFP/wtCD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice were treated with 200μl (10mg/ml) Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich: T5648–5G) in corn oil by oral gavage. TdTomato+ thymocytes were allowed to mature for at least two weeks post-tamoxifen treatment. DTR-GFP expressing Treg cells were concomitantly depleted by intraperitoneal injection with 0.5μg diphtheria toxin (DT: List Biological Laboratories: Cat #150) in 100μl PBS. The exact number of DT injections was empirically determined for individual batches of DT to allow maximum depletion of DTR-GFP expressing cells while avoiding non-specific toxicity associated with DT treatment. All mice received at least 3 injections with DT.

pTreg-induction in response to microbial colonization

To measure extrathymic Foxp3 induction in response to microbial colonization, Foxp3DTR-GFP/Thy1.1CD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt or Foxp3DTR-GFP/wtCD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice were bred on antibiotic-containing drinking water and an amino acid-defined diet. After labeling, experimental mice were colonized by oral gavage with SPF fecal microbiota slurry and housed in dirty SPF cages on regular chow diet and water. Mice were analyzed after two weeks. Control animals were maintained on antibiotic-containing drinking water and an amino acid-defined diet.

H. polygyrus infection

Foxp3DTR-GFP/wtCD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice were subject to pTreg cell fate mapping as described. Following the labeling procedure, mice were infected with 200 H. polygyrus L3 larvae by oral gavage. Spleens and mLN were analyzed by flow cytometry 3 weeks post-infection.

Allogeneic pregnancy

Foxp3DTR-GFP/wtCD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt females were subject to pTreg cell fate mapping as described. Following the labeling procedure, females were moved to breeding cages containing SPRET/EiJ males (breeders) or housed without a male (virgins) for 25 days.

Lewis lung cancer

Foxp3DTR-GFP/wtCD4CreER/wtR26lsl-tdTomato/wt mice were subject to pTreg cell fate mapping as described. Following the labeling procedure, mice in the LLC group were intravenously injected with 150.000 Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells (LLC), or left uninjected (control) and analyzed 17–20 days later.

Tissue preparation and cell isolation

For flow cytometry analysis of thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes, tissues were mechanically dissociated with the back of a syringe plunger and filtered through a 100-µm nylon mesh. For analysis of immune cells in the colon, tissues were enzymatically digested with DTT/EDTA buffer (PBS with 2mM L-glutamine, 10mM HEPES, 1x penicillin/streptomycin, 5% FCS, 1mM DTT and 2mM EDTA) for 15 minutes for 20 minutes at 37°C shaking at 250 RPM. Cells were filtered through a 100-µm nylon mesh to collect the intraepithelial fraction. Remaining colon tissue was further digested with Collagenase/DNase buffer (RPMI-1640 with 2mM L-glutamine, 10mM HEPES, 1x penicillin/streptomycin, 5% FCS, 1 mg/ml collagenase A from Clostridium histolyticum (Sigma-Aldrich: Cat #11088793001), and 1 µg/ml DNaseI (Sigma-Aldrich: Cat #10104159001)) for 25 minutes at 37°C shaking at 250 RPM in the presence of five 0.25-inch ceramic spheres (MP Biomedicals: Cat #116540412). Cells were filtered through a 100-µm nylon mesh to collect the lamina propria fraction. Immune cells from healthy and tumor bearing lungs and uterus were isolated by Collagenase/DNase digestion of minced tissues for 25 minutes.

To analyze cytokine production, single cell suspensions were incubated for 3 hours in 96 well v-bottom plates with 50ng/ml PMA (Millipore Sigma: Cat #P8139), 0.5 µg/ml ionomycin (Millipore Sigma: Cat #I0634), 1 µg/ml brefeldin A Millipore Sigma: Cat #B7651) and 2 µM monensin (Millipore Sigma: Cat #M5273) in complete RPMI with 10% FCS for 3h at 37°C with 5% CO2. To analyze cytokine production by immune cells from non-lymphoid tissues, cell suspensions were enriched by 40% Percoll centrifugation prior to in vitro re-stimulation.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared in ice-cold FACS buffer (PBS with 2mM EDTA and 1% FCS) and subjected to red blood cell lysis using ACK buffer (150mM NH4Cl, 10mM KHCO3, 0.1mM Na2EDTA, pH7.3). Dead cells were stained with Ghost Dye Violet 510 (Tonbo Biosciences: Cat #13–0870) in PBS for 10 minutes at 4°C. Cell surface antigens were stainedfor 15 min at 4°C using a mixture of fluorophore-conjugated antibodies. Cells were analyzed unfixed or fixed and permeabilized using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences: Cat #554714) (cytokine staining) or the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor staining buffer set (ThermoFisher: Cat #00–5523-00), prior to intracellular staining, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were re-suspended in FACS buffer and filtered through a 100-µm nylon mesh before data acquisition on a BD LSRII flow cytometer or sorting on a BD Aria II. Prior to sorting, CD4 T cells were enriched using CD4 Dynabeads (ThermoFisher: Cat #11461D) or Miltenyi MicroBeads (Miltenyi: Cat #130–117-043), according to manufacturer protocol. 123count eBeads (ThermoFisher: Cat #01–1234-42) were used to quantify absolute cell numbers.

Whole-mount intestine immunofluorescence

Following intestine dissection, colon tissue was pinned down on a plate coated with Sylgard, followed by overnight fixation in PBS/4% PFA at 4° C. After washing in DPBS, samples were then permeabilized first in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100/0.05% Tween-20/(4 μg−µL) heparin (PTxwH) for 2 hours at room temperature (RT) with gentle agitation. Samples were then blocked for 2 hours in blocking buffer (PTxwH with 5 % donkey serum) for 2 hours at RT with gentle agitation. Primary antibodies were added to blocking buffer at appropriate concentrations and incubated for 2–3 days at 4°C. After primary incubation samples were washed in PTxwH, followed by incubation with secondary antibody in PTxwH at appropriate concentrations for 2 hours at RT. Samples were again washed in PTxwH, and then mounted with Fluoromount G on slides with 1 ½ coverslips. Slides were kept in the dark at 4 °C until they were imaged.

Antibodies for intestinal mast cell immunofluorescence

The following antibodies were used for intestinal mast cell visualization: Polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse GFP Alexa Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher Cat #A-21311), rat anti-mouse Mcpt1 (R&D systems: MAB5146) and rat anti-mouse EpCAM Alexa Fluor 647 (BioLegend: Cat #118212).

Confocal imaging of whole-mount intestine samples

Images of whole-mount intestine samples were acquired on an inverted LSM 880 NLO laser scanning confocal and multiphoton microscope (Zeiss).

Histology

Distal colon tissue samples were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Histology was performed by HistoWiz Inc. (histowiz.com) using a Standard Operating Procedure and fully automated workflow. Samples were processed, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5µm thickness. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining was performed on Tissue-Tek automated slide stainer (Sakura) using HistoWiz’s standard protocol. After staining, sections were dehydrated and film coverslipped using a TissueTek-Prisma and Coverslipper (Sakura). Whole slide scanning (40x) was performed on an Aperio AT2 (Leica Biosystems). Colitis was evaluated by a board-certified pathologist and scored on a scale from 0 to 3.

RNA-sequencing

Cell populations were double sorted straight into 1ml TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Cat # 15596018). Phase separation was induced with chloroform. RNA was precipitated with isopropanol and linear acrylamide and washed with 75% ethanol. The samples were resuspended in RNase-free water. After RiboGreen quantification and quality control by Agilent BioAnalyzer, 390pg-2ng total RNA with detectable RNA integrity numbers ranging from 7.9 to 10 underwent amplification using the SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit (Clonetech Cat # 63488), with 12 cycles of amplification. Subsequently, 2–10ng of amplified cDNA was used to prepare libraries with the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems Cat #KK8504) using 8 cycles of PCR. Samples were barcoded and run on a HiSeq 4000, HiSeq 2500 in High Output Mode, or HiSeq 2500 in Rapid Mode in PE50 runs, using the HiSeq 3000/4000 SBS Kit, TruSeq SBS Kit v4, or HiSeq Rapid SBS Kit v2, respectively (Illumina). An average of 43 million paired reads were generated per sample and the percent of mRNA bases per sample ranged from 67% to 80%.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing and pre-processing

Single-cell RNA-Seq of FACS-sorted cell populations was performed on a Chromium instrument (10X Genomics) following the user guide manual for 3′ v3 or 5′ v2 chemistry. In brief, FACS-sorted cells were washed once with PBS containing 0.04% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and resuspended in PBS containing 0.04% BSA to a final concentration of 700–1,200 cells per μl. The viability of cells was above 80%, as confirmed with 0.2% (w/v) Trypan Blue staining (Countess II). Cells were captured in droplets. Following reverse transcription and cell barcoding in droplets, emulsions were broken and cDNA was purified using Dynabeads MyOne SILANE (ThermoFisher: Cat # 37002D) followed by PCR amplification per manual instruction.

For the analysis of mLN CD4 T cells from germ-free and recently colonized Foxp3GFP and Foxp3GFP∆CNS1 mice, approximately 5000 cells were targeted for each sample and prepared using the user guide manual for 3′ v3 chemistry. Final libraries were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq S4 platform (R1 – 28 cycles, i7 – 8 cycles, R2 – 90 cycles). The cell-gene count matrix was constructed using the Sequence Quality Control (SEQC) package(Azizi et al., 2018). Viable cells were identified based on library size and complexity, whereas cells with >20% of transcripts derived from mitochondria were excluded from further analysis.

For the analysis of tdTomato+GFP+ and tdTomato−GFP− colonic lamina propria CD4 T cells, approximately 5,000 cells were targeted for each sample, and triplicates from the same biological group were multiplexed together on one lane of 10X Chromium to reach 15,000 cells targeted, following cell hashing with TotalSeq-C reagents (Biolegend) used at a 1:200 dilution (Stoeckius et al., 2018). ScRNA-seq and scTCR-seq libraries were prepared using the 10x Single Cell Immune Profiling Solution Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, amplified cDNA was used for both 5′ gene expression library construction and TCR enrichment. For gene expression library construction, amplified cDNA was fragmented and end-repaired, double-sided size-selected with SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter: Cat #B23318), PCR-amplified with sample indexing primers (98 °C for 45 s; 14–16 cycles of 98 °C for 20 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 20 s; 72 °C for 1 min), and double-sided size-selected with SPRIselect beads. For TCR library construction, TCR transcripts were enriched from 2 μl of amplified cDNA by PCR (primer sets 1 and 2: 98 °C for 45 s; 10 cycles of 98 °C for 20 s, 67 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min; 72 °C for 1 min). Following TCR enrichment, enriched PCR product was fragmented and end-repaired, size-selected with SPRIselect beads, PCR-amplified with sample-indexing primers (98 °C for 45 s; 9 cycles of 98 °C for 20 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 20 s; 72 °C for 1 min), and size-selected with SPRIselect beads. Final libraries (GEX, TCR and HTO) were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq S4 platform (R1 – 26 cycles, i7 – 10 cycles, i5 – 10 cycles, R2 – 90 cycles).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analysis of bulk-cell RNA sequencing data

RNA-sequencing reads were aligned to the reference mouse genome GRCm38 using the STAR RNA-seq aligner (Dobin et al., 2013) and local realignment was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (McKenna et al., 2010). For each sample, raw count of reads per gene was measured using R, and DESeq2 R package (Love et al., 2014) was used to perform differential gene expression analysis. A cutoff of 0.05 was set on the obtained p values (that were adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction) to get the significant genes of each comparison. The threshold to minimum average expression within samples of each comparison was set to 30 reads. DESeq2 package was used for PCA calculation of components as well.

Raw and processed RNA-seq data was deposited to NCBI GEO under accession number GSE176237.

Analysis of single-cell RNA-sequencing data

mLN samples:

FASTQ files from sequencing were processed by “cellranger count” v4.0.0 using reference transcriptome refdata-gex-mm10–2020-A (Zheng et al., 2017). The resulting count matrices were analyzed in scanpy v1.5.1 (Wolf et al., 2018). For preliminary analysis, only cells with at least 100 captured genes were considered, and only genes captured in at least 10 cells were considered. This resulted in 4,111 cells in the sample “GFP-GF”, 4,146 cells in the sample “GFP-Colonized”, 3,635 cells in the sample “CNS1-GF”, and 5,586 cells in the sample “CNS1-Colonized”. Then normalization was performed using function scanpy.pp.normalize_total() with parameters exclude_highly_expressed=True, max_fraction=0.02. The subsequent analysis focused only on protein-coding genes, and furthermore ribosomal genes were excluded from the analysis. After that, cells with less than 400 captured genes (227 cells collectively over the four samples) were excluded from the analysis, and genes captured in less than 10 cells (9 genes) were excluded. For preliminary analysis, cells from all four samples combined were clustered into 16 clusters using function scanpy.tl.louvain() with parameter resolution=1.5. Clusters with high expression of B cell genes (120 cells across all four samples) and CD8 T cell/NK/NKT cell genes (183 cells across the four samples) were identified as likely contamination and excluded from the subsequent main analysis. In the main analysis, dimensionality reduction was performed using PCA, followed by kNN construction using function scanpy.pp.neighbors() with parameters n_neighbors=30, n_pcs=50, use_rep=‘X_pca’, and data was then visualized with UMAP using function scanpy.tl.umap() with parameter min_dist=0.2 and with tSNE using function sc.tl.tsne() with default parameters. Cells then were clustered using package PhenoGraph (Levine et al., 2015) with parameter k=30 and otherwise default paramerters, resulting in clusters 0–9. Differential expression analysis comparing cells from each cluster with all other cells was run using Mann-Whitney U statistical test applied to normalized counts.

The pTreg gene signature obtained from the bulk RNA-seq analysis was defined as genes with significantly higher expression (p < 0.1) in tdTomato+GFP+ cells when compared with each of the three other samples (tdTomato−Thy1.1+, tdTomato−GFP+, and tdTomato+Thy1.1+), with at least one comparison reaching a significance of p<0.01. This resulted in a list of 1,087 genes. The pTreg signature was scored in the normalized scRNA-seq data using function scanpy.tl.score_genes() with default parameters. For visualization of gene expression, imputation algorithm MAGIC (van Dijk et al., 2018) was applied with parameters k=30, t=3, n_pca=50, random_state=0. For subsequent more focused analysis of Treg and pTreg cells, clusters 1,2,4,7 were excluded, and the remaining cells were reanalyzed using PCA as described above, kNN using scanpy.pp.neighbors() with parameters n_neighbors=20, n_pcs=50, use_rep=‘X_pca’, UMAP using scanpy.tl.umap() with default parameters, and clustered using PhenoGraph with k=20, resulting in clusters s0-s9. Notably, previously defined cluster 8 (640 cells) was split mostly between clusters s8 (227 cells, with 218 cells in overlap with cluster 8) and s6 (542 cells, with 402 cells in overlap with cluster 8). Enrichment of overlap of cluster s8 (likely enriched for pTreg cells) with each sample was tested using hypergeometric test.

Colon samples

The analysis was performed similarly for tdTomato+GFP+ and tdTomato−GFP− colonic lamina propria CD4 T cell samples. FASTQ files from both scRNA and hashtag (HTO) sequencing were processed by “cellranger count” v6.0.1 using reference transcriptome refdata-gex-mm10–2020-A. In each of the two conditions, HTO read counts for three hashtags were then used to assign each cell barcode to one of the three biological replicates. 19,449 cells with a total HTO read count > 300 and with at least 80% of the total HTO read count concentrated in one of the three hashtags were considered further as those with uniquely identifiable biological replicate assignment (filtering out 5,048 cells with uncertain or insufficient HTO data). Furthermore, only cells with at least 100 captured genes and only genes captured in at least 10 cells were considered for subsequent analysis. In further preprocessing, data was normalized, non-protein-coding and ribosomal genes filtered out, cells with less than 300 captured genes and genes present in less than 10 cells removed, and likely contamination B and monocyte cells filtered out as a result of preliminary clustering analysis. This resulted in data with 5,100 cells in sample “GFP_minus_Tom_minus_rep1”, 3,067 in “GFP_minus_Tom_minus_rep2”, 1,815 in “GFP_minus_Tom_minus_rep3”, 1,725 in “GFP_plus_Tom_plus_rep1”, 4,560 in “GFP_plus_Tom_plus_rep2” and 2,391 cells in sample “GFP_plus_Tom_plus_rep3”. This dataset was analyzed using PCA, kNN, UMAP, PhenoGraph clustering and differential expression analysis between clusters as described above. For TCR reconstruction, FASTQ files from TCR sequencing were processed using “cellranger vdj” with reference refdata-cellranger-vdj-GRCm38-alts-ensembl-5.0.0 and otherwise default parameters. Files filtered_contig_annotations.csv from cellranger vdj output for each sample were then used for TCR sequence and clonotype analysis using package scirpy v0.10.0 following the tutorial (Sturm et al., 2020). Merging the TCR data with the scRNA-seq data and removing cells without at least one full pair of receptor sequences resulted in the dataset with 15,863 cells. Clonotypes were then defined using functions scirpy.pp.ir_dist() and scirpy. tl.define_clonotypes().

Raw and processed scRNA-seq data was deposited to NCBI GEO under accession numbers GSE176293 and GSE193780.

Foxp3 induction in mature CD4+ T cells gives rise to peripheral Treg (pTreg) cells that enforce tolerance to food and commensal microbes. However, the role of Foxp3 in pTreg cells and the mechanisms supporting their differentiation remain unclear. Van der Veeken et al. use genetic tracing to identify microbiota-induced pTreg cells and find that they have Foxp3-dependent and -independent features.

Supplementary Material

Key resources table.

Total seq reagents

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| BUV496 - B220 (clone RA3–6B2) | BD Biosciences | 564662 |

| APC - c-Kit (clone 2B8) | BD Biosciences | 553356 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 - CD11b (clone M1/70) | BioLegend | 101257 |

| FITC - CD11c (clone HL3) | BD Biosciences | 553801 |

| BUV395 - CD19 (clone 1D3) | BD Biosciences | 563557 |

| BUV395 - CD25 (clone PC61) | BD Biosciences | 564022 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 - CD4 (clone RM4–5) | Tonbo Bioscience | 65–0042-U100 |

| BUV496 - CD4 (clone GK1.5) | BD Biosciences | 564667 |

| APC - CD44 (clone IM7) | Tonbo Bioscience | 20–0441-U100 |

| Brilliant Violet 570 – CD45 (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | 103136 |

| Brilliant Violet 711 - CD5 (clone 53–7.3) | Biolegend | 100639 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 - CD62L (clone MEL-14) | Biolegend | 104438 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 - CD64 (clone X54–5/7.1) | Biolegend | 139308 |

| BUV737 - CD8α (clone 53–6.7) | BD Biosciences | 564297 |

| APC - CD90.1 (clone HIS51) | ThermoFisher | 17–0900-82 |

| APC-eFluor780 - CD90.1 (clone HIS51) | ThermoFisher | 47–0900-82 |

| Brilliant Violet 785 - CD90.2 (clone 30-H12) | Biolegend | 105331 |

| PE eFluor610 - F4|80 (clone BM8) | ThermoFisher | 61–4801-82 |

| PE - FcεRIα (clone MAR-1) | ThermoFisher | 12–5898-82 |

| APC - Foxp3 (clone FJK-16s) | ThermoFisher | 17–5773-82 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 - GM-CSF (clone MP1–22E9) | Biolegend | 505410 |

| PE-Cy7 - Gr-1 (clone RB6–8C5) | ThermoFisher | 25–5931-82 |

| Pacific Blue - Helios (clone 22F6) | Biolegend | 137210 |

| APC - IFNγ (clone XMG1.2) | ThermoFisher | 17–7311-82 |

| Brilliant Violet 421 - IL-10 (clone JES5–16E3) | Biolegend | 505021 |

| PE-eFluor610 - IL-17A (clone 17B7) | ThermoFisher | 61–7177-82 |

| PE - IL-4 (clone 11B11) | ThermoFisher | 12–7041-82 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 - Ki67 (clone SolA15) | ThermoFisher | 46–5698 |

| Brilliant Violet 710 - Ly-6C (clone HK1.4) | Biolegend | 128037 |

| redFluor710 - MHC-II (clone M5/114.15.2) | Tonbo Bioscience | 80–5321-U100 |

| eFluor 450 - NK1.1 (clone PK136) | ThermoFisher | 48–5941-82 |

| PE-eFluor610 - Nrp-1 (clone 3DS304M) | ThermoFisher | 61–3041-82 |

| Brilliant Violet 421 - RORγt (clone Q31–378) | BD Biosciences | 562894 |

| Brilliant Violet 421 - Siglec-F (clone E50–2440) | BD Biosciences | 562681 |

| APC-Cy7 - TCR-β (clone H57–597) | BioLegend | 109220 |

| PE-eFluor610 - TCR-β (clone H57–597) | ThermoFisher | 61–5961-82 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 - TCRγδ (clone GL3) | Biolegend | 118129 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 - TNFα (clone MP6-XT22) | Biolegend | 506329 |

| Brilliant Violet 650 - XCR1 (clone ZET) | Biolegend | 148220 |

| Mcpt1 | R&D systems | MAB5146 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 - EpCAM | BioLegend | 118212 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse GFP Alexa Fluor 488 | ThermoFisher | A-21311 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ampicillin | Sigma-Aldrich | A0166–5G |

| Brefeldin A | Millipore Sigma | B7651 |

| Collagenase A from Clostridium histolyticum | Sigma-Aldrich | 11088793001 |

| Diphtheria Toxin | List Biological Laboratories | 150 |

| DNase I grade II, from bovine pancreas | Sigma-Aldrich | 10104159001 |

| Ghost Dye Violet 510 | Tonbo Biosciences | 13–0870 |

| Ionomycin calcium salt | Millipore Sigma | I0634 |

| Metronidazole | Sigma-Aldrich | M1547–25G |

| Monensin sodium salt | Millipore Sigma | M5273 |

| Neomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | N6386–100G |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) | Millipore Sigma | P8139 |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma-Aldrich | T5648–5G |

| Trizol Reagent | ThermoFisher | 15596018 |

| Vancomycin | Fresenius-Kabi | C314061 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| 123count eBeads | ThermoFisher | 01–1234-42 |

| CD4 (L3T4) MicroBeads, mouse | Miltenyi | 130–117-043 |

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5’ Kit v2 | 10x Genomics | 1000263 |

| Chromium Single Cell 3ʹ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3 | 10x Genomics | 1000075 |

| Chromium Single Cell Mouse TCR Amplification Kit | 10x Genomics | 1000254 |

| Dynabeads Flowcomp Mouse CD4 Kit | Thermo Fisher | 11461D |

| Dynabeads MyOne SILANE | ThermoFisher | 37002D |

| eBioscience Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | ThermoFisher | 00–5523-00 |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (Cytofix/Cytoperm) | BD Biosciences | 554714 |

| KAPA Hyper Prep Kit | Kapa Biosystems | KK8504 |

| SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit | Clonetech | 63488 |

| SPRIselect beads | Beckman Coulter | B23318 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Bulk-cell RNA-seq data | This paper | GSE176237 |

| Single-cell RNA-seq data mesenteric lymph node | This paper | GSE176293 |

| Single-cell RNA-seq data colon lamina propria | This paper | GSE193780 |

| Microarray data from Spleen and Colon Treg cells | PMID: 26272906 | GSE71316 |

| RNA-seq data from WT and Maf-deficient Treg cells | PMID: 29414937 | GSE108184 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| LLC cells | Provided by J. Massague (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY) | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Foxp3DTR-GFP: B6.129(Cg)-Foxp3tm3(DTR/GFP)Ayr/J | PMID: 17136045 | JAX:016958 |

| CD4CreER: Cd4tm1(cre/ERT2)Thbu | PMID: 24115907 | MGI:5549971 |

| Rosa26lsl-tdTomato: B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J | PMID: 20023653 | JAX: 007914 |

| Foxp3Thy1.1: Foxp3tm10.1(Casp9,-Thy1)Ayr | PMID: 18695219 | MGI:5451201 |

| Foxp3GFP: B6.129-Foxp3tm2Ayr/J | PMID: 15780990 | MGI:3574964 |

| Foxp3GFP∆CNS: Foxp3tm5.2Ayr | PMID: 20072126 | MGI:4430232 |

| Foxp3 ΔEGFPiCre | PMID: 31384057 | N/A |

| Rosa26lsl-DTR: Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai | PMID: 15908920 | JAX:007900 |

| Foxp3GFPKO: Foxp3tm8Ayr | PMID: 17220874 | MGI: 4436759 |

| Foxp3 loxP-Thy1.1-STOP-loxP-GFP | PMID: 34426690 | N/A |

| SPRET/EiJ | N/A | JAX:001146 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo (v10) | FlowJo, LLC | https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo |

| R | The Comprehensive R Archive Network | https://cran.r-project.org/ |

| Prism (v9) | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism |

| STAR | PMID: 23104886 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| DESeq2 (R Package) | PMID: 25516281 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/DESeq2 |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | PMID: 20644199 | https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us |

| Cellranger | 10X Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/downloads/latest |

| Scanpy | PMID: 29409532 | https://github.com/theislab/scanpy |

| MAGIC | PMID: 29961576 | https://github.com/KrishnaswamyLab/MAGIC |

| Phenograph | PMID: 26095251 | https://github.com/jacoblevine/PhenoGraph |

Highlights.

Developed a strategy for genetic labelling of peripherally induced Treg (pTreg) cells

Expression of a pTreg transcriptional program is Foxp3-independent

Foxp3 is dispensable for commitment and fitness of microbiota-dependent pTreg cells

Foxp3-deficient Treg cells can suppress colonic T cell expansion

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all members of the Rudensky lab for discussions, Bruno Moltedo and Jesse Green for help with LLC experiments. This study was supported by NIH grants R01AI034206, R01AI153174, and NIH/NCI Grant P30 CA008748, AACR-Bristol-Myers Squibb Immuno-oncology Research Fellowship 19–40-15-PRIT, and the Ludwig Center at MSKCC. A.Y.R. is an HHMI investigator. We acknowledge the use of the MSKCC Single Cell Research Initiative and the Integrated Genomics Operation Core, funded by NIH/NCI Grant P30 CA008748, Cycle for Survival, and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

A.Y.R. is an SAB members and holds equity in Surface Oncology, Vedanta Biosciences, Sonoma Biotherapeutics, and RAPT Therapeutics, is an SAB member of BioInvent and holds IP licensed to Takeda which is unrelated to the current study.

REFERENCES

- Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Florens M, Hussein H, and Boeckxstaens G (2021). Local immune response as novel disease mechanism underlying abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Acta Clin Belg, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Apostolou I, and von Boehmer H (2004). In vivo instruction of suppressor commitment in naive T cells. J Exp Med 199, 1401–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, Liu H, Cross JR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, and Rudensky AY (2013). Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504, 451–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvey A, van der Veeken J, Samstein RM, Feng Y, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, and Rudensky AY (2014). Inflammation-induced repression of chromatin bound by the transcription factor Foxp3 in regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 15, 580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, Cornish AE, Konopacki C, Prabhakaran S, Nainys J, Wu K, Kiseliovas V, Setty M, et al. (2018). Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 174, 1293–1308.e1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, and Noelle RJ (2007). All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med 204, 1765–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, and Kuchroo VK (2006). Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch T, Heppner FL, Tertilt C, Heinen TJ, Kremer M, Wunderlich FT, Jung S, and Waisman A (2005). A Cre-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor mediates cell lineage ablation after toxin administration. Nat Methods 2, 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchill MA, Yang J, Vang KB, Moon JJ, Chu HH, Lio CW, Vegoe AL, Hsieh CS, Jenkins MK, and Farrar MA (2008). Linked T cell receptor and cytokine signaling govern the development of the regulatory T cell repertoire. Immunity 28, 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Dikiy S, Bhattarai SK, Chinen T, Matheis F, Calafiore M, Hoyos B, Hanash A, Mucida D, Bucci V, and Rudensky AY (2018). Extrathymically Generated Regulatory T Cells Establish a Niche for Intestinal Border-Dwelling Bacteria and Affect Physiologic Metabolite Balance. Immunity 48, 1245–1257.e1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, McKenney PT, Konstantinovsky D, Isaeva OI, Schizas M, Verter J, Mai C, Jin WB, Guo CJ, Violante S, et al. (2020). Bacterial metabolism of bile acids promotes generation of peripheral regulatory T cells. Nature 581, 475–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai JN, Peng Y, Rengarajan S, Solomon BD, Ai TL, Shen Z, Perry JSA, Knoop KA, Tanoue T, Narushima S, et al. (2017). Helicobacter species are potent drivers of colonic T cell responses in homeostasis and inflammation. Sci Immunol 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnier LM, Cui Y, Stephen-Victor E, Harb H, Lopez D, Bleesing JJ, Garcia-Lloret MI, Chen K, Ozen A, Carmeliet P, et al. (2019). Functional reprogramming of regulatory T cells in the absence of Foxp3. Nat Immunol 20, 1208–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, and Wahl SM (2003). Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25-naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med 198, 1875–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold SP, Castejon R, Adams E, Zelenika D, Graca L, Humm S, and Waldmann H (2004). Induction of foxP3+ regulatory T cells in the periphery of T cell receptor transgenic mice tolerized to transplants. J Immunol 172, 6003–6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, and Powrie F (2007). A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 204, 1757–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curotto de Lafaille MA, and Lafaille JJ (2009). Natural and adaptive foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity 30, 626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, and Rudensky AY (2005). Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity 22, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, et al. (2013). Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504, 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaublomme JT, Yosef N, Lee Y, Gertner RS, Yang LV, Wu C, Pandolfi PP, Mak T, Satija R, Shalek AK, et al. (2015). Single-Cell Genomics Unveils Critical Regulators of Th17 Cell Pathogenicity. Cell 163, 1400–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin MA, Rasmussen JP, Fontenot JD, Vasta V, Manganiello VC, Beavo JA, and Rudensky AY (2007). Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature 445, 771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk RA, Corse E, and Allison JP (2012). Expression of Helios in peripherally induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 188, 976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang S, Paik D, Yao L, Kim E, Trinath J, Lu J, Ha S, Nelson BN, Kelly SP, Wu L, et al. (2019). Bile acid metabolites control TH17 and Treg cell differentiation. Nature 576, 143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TJ, Grosso JF, Yen HR, Xin H, Kortylewski M, Albesiano E, Hipkiss EL, Getnet D, Goldberg MV, Maris CH, et al. (2007). Cutting edge: An in vivo requirement for STAT3 signaling in TH17 development and TH17-dependent autoimmunity. J Immunol 179, 4313–4317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmers S, Schizas M, Azizi E, Dikiy S, Zhong Y, Feng Y, Altan-Bonnet G, and Rudensky AY (2019). IL-2 production by self-reactive CD4 thymocytes scales regulatory T cell generation in the thymus. J Exp Med 216, 2466–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Wang ZM, Feng Y, Schizas M, Hoyos BE, van der Veeken J, Verter JG, Bou-Puerto R, and Rudensky AY (2021). Regulatory T cells function in established systemic inflammation and reverse fatal autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 22, 1163–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, and Littman DR (2006). The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, Lu H, Ichiyama K, Chen X, Zhang YB, Mistry NA, Tanaka K, Lee YH, Nurieva R, Zhang L, et al. (2017). Generation of RORgammat(+) Antigen-Specific T Regulatory 17 Cells from Foxp3(+) Precursors in Autoimmunity. Cell Rep 21, 195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, and Rudensky AY (2007). Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol 8, 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Hong SW, Han D, Yi J, Jung J, Yang BG, Lee JY, Lee M, and Surh CD (2016). Dietary antigens limit mucosal immunity by inducing regulatory T cells in the small intestine. Science 351, 858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, and von Boehmer H (2005). Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol 6, 1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, Quintana FJ, Xiao S, Peters A, Wu C, Kleinewietfeld M, Kunder S, Hafler DA, et al. (2012). Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol 13, 991–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JH, Simonds EF, Bendall SC, Davis KL, Amir e.-A., Tadmor MD, Litvin O, Fienberg HG, Jager A, Zunder ER, et al. (2015). Data-Driven Phenotypic Dissection of AML Reveals Progenitor-like Cells that Correlate with Prognosis. Cell 162, 184–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lio CW, and Hsieh CS (2008). A two-step process for thymic regulatory T cell development. Immunity 28, 100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston A, Nutsch KM, Farr AG, Lund JM, Rasmussen JP, Koni PA, and Rudensky AY (2008). Differentiation of regulatory Foxp3+ T cells in the thymic cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 11903–11908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, and Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. (2010). A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13, 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, and DePristo MA (2010). The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20, 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucida D, Kutchukhidze N, Erazo A, Russo M, Lafaille JJ, and Curotto de Lafaille MA (2005). Oral tolerance in the absence of naturally occurring Tregs. J Clin Invest 115, 1923–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, and Cheroutre H (2007). Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science 317, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann C, Blume J, Roy U, Teh PP, Vasanthakumar A, Beller A, Liao Y, Heinrich F, Arenzana TL, Hackney JA, et al. (2019). c-Maf-dependent Treg cell control of intestinal TH17 cells and IgA establishes host-microbiota homeostasis. Nat Immunol 20, 471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutsch K, Chai JN, Ai TL, Russler-Germain E, Feehley T, Nagler CR, and Hsieh CS (2016). Rapid and Efficient Generation of Regulatory T Cells to Commensal Antigens in the Periphery. Cell Rep 17, 206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmacht C, Park JH, Cording S, Wing JB, Atarashi K, Obata Y, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Marques R, Dulauroy S, Fedoseeva M, et al. (2015). The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORγt⁺ T cells. Science 349, 989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omenetti S, Bussi C, Metidji A, Iseppon A, Lee S, Tolaini M, Li Y, Kelly G, Chakravarty P, Shoaie S, et al. (2019). The Intestine Harbors Functionally Distinct Homeostatic Tissue-Resident and Inflammatory Th17 Cells. Immunity 51, 77–89.e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratama A, Schnell A, Mathis D, and Benoist C (2020). Developmental and cellular age direct conversion of CD4+ T cells into RORgamma+ or Helios+ colon Treg cells. J Exp Med 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schambach F, Schupp M, Lazar MA, and Reiner SL (2007). Activation of retinoic acid receptor-alpha favours regulatory T cell induction at the expense of IL-17-secreting T helper cell differentiation. Eur J Immunol 37, 2396–2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell A, Huang L, Singer M, Singaraju A, Barilla RM, Regan BML, Bollhagen A, Thakore PI, Dionne D, Delorey TM, et al. (2021). Stem-like intestinal Th17 cells give rise to pathogenic effector T cells during autoimmunity. Cell 184, 6281–6298 e6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefik E, Geva-Zatorsky N, Oh S, Konnikova L, Zemmour D, McGuire AM, Burzyn D, Ortiz-Lopez A, Lobera M, Yang J, et al. (2015). Individual intestinal symbionts induce a distinct population of RORγ⁺ regulatory T cells. Science 349, 993–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledzińska A, Hemmers S, Mair F, Gorka O, Ruland J, Fairbairn L, Nissler A, Müller W, Waisman A, Becher B, and Buch T (2013). TGF-β signalling is required for CD4⁺ T cell homeostasis but dispensable for regulatory T cell function. PLoS Biol 11, e1001674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, Glickman JN, and Garrett WS (2013). The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341, 569–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Sun X, Oh SF, Wu M, Zhang Y, Zheng W, Geva-Zatorsky N, Jupp R, Mathis D, Benoist C, and Kasper DL (2020). Microbial bile acid metabolites modulate gut RORγ+ regulatory T cell homeostasis. Nature 577, 410–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]