Abstract

In Box v Planned Parenthood, Justice Thomas wrote an impassioned concurrence describing abortions based on sex, disability or race as a form of ‘modern-day eugenics’. He defended the challenged Indiana reason-based abortion (RBA) ban as a necessary antidote to these practices. Inspired by this concurrence, legislatures have increasingly enacted similar bills and statutes allegedly as a prophylactic to ‘eugenics’, its underlying discrimination, and the racial disparities eugenics caused. This article tests my hypothesis that this legislative focus on eugenics is largely performative, rather than evidence of true concern about the discrimination and disparities underlying eugenics. My research examined state laws in several areas that fall within narrow and broad understandings of eugenics to determine whether states with RBA bans have implemented policies to counteract eugenics more broadly. My analysis shows that they generally have not. Instead, the apparent motivation is to commandeer concerns about eugenics to restrict reproductive rights. This legislative mission is hypocritical, and it harms the very groups impacted by the eugenics movements—minorities, women, people with disabilities, the LGBTQ+ community, and immigrants. Ultimately, it has led us to Dobbs, which makes everyone vulnerable to the eugenics policies Thomas condemns by undercutting previous constitutional protections against eugenics.

I. INTRODUCTION

The eugenics movement is a scourge upon American history. It represents an era when the government abused its power by controlling the reproductive lives of the disenfranchised—the disabled, the mentally impaired, and others deemed to be deficient based on class or race. It was also manifested in stringent immigration restrictions rooted in racism, prejudice, and stereotypes. Persuaded by the veneer of scientific validity, progressives, educated individuals, and social reformers supported eugenic policies as vital to the national welfare.1 Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr fully embraced the now debunked eugenics theories in his infamous majority opinion in Buck v Bell. In a mere five paragraphs, Holmes effortlessly determined there was no constitutional violation in Virginia’s involuntary sterilization of Carrie Buck, who, along with her mother and daughter, was diagnosed as an ‘imbecile’. Shockingly, Holmes easily concluded in one of the most problematic Supreme Court lines that ‘three generations of imbeciles is enough’.2 The litigation over Virginia’s mandatory involuntary sterilization law was a test case for the growing number of such laws.3 The Supreme Court’s endorsement of this eugenic sterilization law inspired even more legislators to follow suit, resulting in eugenic sterilization laws in 28 states by 1931.4

While that history seems unimaginable to many today,5Buck v Bell has not actually been overturned. Indeed, Roe v Wade, which itself was just overturned, cited Buck v Bell as authority for the proposition that constitutional rights are not absolute.6 Nevertheless, there is near unanimity that the eugenics chapter was a horror to avoid repeating at all costs. Eugenics, once a symbol of progressive social reform, is now a term of derision, evoking contempt for highly discriminatory state policies.7

Nearly, 100 years after Buck v Bell was decided, another Supreme Court opinion regarding eugenics—Justice Thomas’s concurrence in Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky8—once again heavily influenced legislation. But instead of promoting eugenics as Holmes did, Thomas drew upon our disgraceful history to condemn abortion as a potential ‘tool of modern-day eugenics’. Thomas’s concurrence focused on an Indiana law that prohibits abortions based on sex, race, or disability,9 which the Seventh Circuit had enjoined as unconstitutional.10 Although Thomas concurred with the Court’s denial of Indiana’s petition for certiorari regarding the ban,11 his 20-page opinion was a full-throated condemnation of ‘reason-based’ abortions as vestiges of the eugenics era. Relying on a decidedly biased and incomplete account of eugenics, his thesis was that reason-based abortion (RBA) bans are appropriate antidotes to ‘modern-day eugenics’. The not so subtle subtext throughout, however, is that abortions themselves are eugenic, a point that Professor Murray demonstrates so powerfully in Race-ing Roe: Reproductive Justice, Racial Justice, and the Battle for Roe v. Wade.12

Just as Buck v Bell inspired more states to enact mandatory sterilization laws, Thomas’s concurrence encouraged more legislatures to propose or enact RBA bans. Indeed, many of the recent bills and some enacted statutes quote Thomas’s concurrence. While supporters of these bans are primarily conservative legislators, the argument that terminating pregnancies based on race, sex, or disability is a form of eugenics transcends conservative politics. In fact, there are many liberal critiques of prenatal testing that describe it as eugenic.13 Thus, this perspective potentially reaches across the aisle.

This article argues, however, that Thomas’s view of eugenics, particularly his vision of the appropriate anti-eugenic remedy, is at best very narrow, and at worst problematic. In response to the growth of RBA bans as prophylactics to ‘eugenics’, which explicitly or implicitly embrace this narrow conception of anti-eugenics, I explored whether their policies are consistent with the expressed concerns underlying these allegedly anti-eugenic measures, or whether the enactment of RBA bans is merely a pretextual nod to concerns about eugenics. In other words, do RBA-ban states allow or impose policies that are eugenic in other ways, or have these states enacted more expansive anti-eugenic measures, demonstrating they are truly concerned about eugenics?

My hypothesis in approaching this project was that states with RBA bans would not tend to have more expansive anti-eugenic measures. Instead, I hypothesized that the focus on eugenics is performative and intended to engender support for yet another abortion restriction, rather than a reflection of true concern about the underlying discrimination that promoted eugenics and the disparities that resulted. To test my hypothesis, I investigated what states with RBA bans have done (or have not done) to address eugenics in other areas. My research found that, accepting Thomas’s concerns about eugenics on his own terms, states with RBA bans are generally not anti-eugenic across various measures.

I should add that this research began well before the seismic shift in the reproductive rights landscape rendered by Dobbs. v Jackson Women’s Health Organization.14 That decision, which unceremoniously overturned the nearly 50-year-old constitutional right to abortion established in Roe v Wade15 and reaffirmed in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v Casey,16 has given the green light to states eager to ban abortion, generally. If my thesis is correct that the focus on eugenics has more to do with a desire to end abortion than true concerns about eugenics, one would expect RBA-ban states to respond quickly to the Dobbs’ invitation to restrict abortion rights. And, indeed, they have. Just five months after Roe was overturned, 14 of the 17 states with RBA bans had enacted or already had trigger laws with complete bans (four of which have been blocked) and one had enacted a 6-week ban (which has also been blocked) (see Table 1). This means that 14 (82.3.5 per cent) of RBA-ban states have sought to ban abortions at six weeks or earlier.

Table 1.

Current Abortion Bans

| Number of RBA-Ban States with Bans | States Where Ban Is in Effect | States Where Ban Is Temporarily or Permanently Enjoined or Found Unconstitutional |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Ban | 14 | Alabama, Arkansas,† Idaho,† Kentucky,† Louisiana,† Mississippi,† Missouri,† Oklahoma,† South Dakota,† Tennessee,† Texas, and West Virginia† | Arizona,† Indiana,† North Dakota,† Michigan, Montana, South Carolina, Utah,† and Wyoming |

| 6-week LMP | 1 | Georgia | Iowa, Ohio† |

†RBA-ban state

That leaves three RBA-ban states. North Carolina has a gestational ban at 20 weeks. Pennsylvania allows abortion with several restrictions. After the 2022 elections, it appears that Pennsylvania will have a divided legislature with a democratic governor, suggesting that, for the near future, Pennsylvania will not impose more stringent regulations. Finally, although Kansas allows abortions until 22 weeks and Kansans voted in August to reject a ballot measure that would have amended the State Constitution to deny a right to an abortion, Kansas still places several restrictions on abortions.17 In addition, because the Kansas legislature retained its republican supermajority, it could impose even more stringent and veto-proof restrictions. In other words, not a single RBA-ban state is unequivocally abortion friendly, and a strong majority make abortion all but inaccessible.

One of the goals of this piece is to demonstrate empirically what most people would suspect—states with RBA bans are more interested in restricting abortion than preventing eugenics. A prior empirical study considered a narrower version of that issue. In 2015, Professor Kalantry examined whether sex-selective abortion bans are anti-immigrant or anti-abortion. Her findings demonstrated that states with a higher growth of Asian immigrants were more likely to pass bans on sex-selective abortions. But she also found that states with sex-selective abortions were more likely to have other kinds of anti-abortion legislation.18 My study indirectly confirms the connection between RBA-bans generally (not just sex-selective abortions) and abortion restrictions by demonstrating the many ways RBA-ban states are not, in fact, concerned with eugenics or discrimination, either on the terms described by Justice Thomas or by other definitions.

Another (forthcoming) piece challenges the coopting of disability rights rhetoric to justify genetic-selective abortion bans.19 Not only does the article show that genetic-selective RBA bans ‘cannot be justified solely on the basis of disability rights’—particularly when such bans have not been ‘proposed as part of a broader disability rights policy agenda’,20 but it also demonstrates that these particular RBA bans do not advance disability rights.21 Instead, the disability rights rhetoric used to justify these laws politicize and hinder the possibility of coalition building on behalf of the disability community, even as the bans restrict reproductive rights.22 My study, like this one, challenges the defense of RBA bans on their own terms to show that the alleged motivation is ineffective, at best, and disingenuous, at worst.

Part I begins by setting up the judicial landscape that led to Thomas’s passionate condemnation of eugenics and defense of RBA bans. It then demonstrates how Thomas uses a partially distorted narrative of the eugenics movement to justify his concerns about ‘modern-day eugenics’ and support for RBA bans as anti-eugenic.

Part II describes how this conception of eugenics has influenced growing efforts to enact RBA bans. These laws have been proliferating since 2010, especially in the last few years. In addition, legislators have increasingly used explicit and implicit references to ‘eugenics’. Indeed, some legislation quotes directly from Thomas’s concurrence in Box.23

Part III then discusses different conceptions of eugenics and anti-eugenics remedies. It points out that in one sense Thomas’s version of eugenics is quite narrow in focusing solely on reproductive decisions. But in another sense, he hints at a broader conception of eugenics by focusing on racial disparities in abortion rates and abortions based on sex. Despite adopting this broader understanding of eugenics, Thomas advocates an anti-eugenic remedy—RBA bans—that is quite narrow.

Part III argues that if we are to take seriously a broad conception of eugenics that examines how state policies lead to racial (or other) disparities, anti-eugenic remedies should address the disproportionately negative impacts on the populations who were harmed by the eugenics movement: people of color, low-income individuals, members of the LGBTQ+ community, females, people with disabilities, and immigrants. It is worth noting also that Thomas’s description of eugenics bleeds into concerns about discrimination and inequality, which are not precisely the same thing as eugenics per se. But they are at the heart of eugenics policies. In many ways, Thomas uses the term eugenics as a bludgeon to critique inequality and discrimination—but only in the abortion context. Indeed, it is striking how little he is concerned about racial, gender, or social class equality in other contexts.24

Part IV provides empirical analysis of various state laws and policies that potentially have eugenic (or anti-eugenic) impacts, or, in some sections, discriminatory (or anti-discriminatory) impacts. Section A begins by focusing on policies tied to a narrow conception of eugenics—laws related to reproduction. An examination of laws related to sterilization, conjugal visits, incest, assisted reproductive technologies, and substance use during pregnancy support my theory that RBA-ban states often do not impose anti-eugenic remedies beyond RBA bans. However, as this section shows, prenatal information laws and bans on wrongful birth/life claims correlate positively with states that have enacted RBA bans. This outcome is not surprising because these laws are tied directly to preventing reason-based abortions and are therefore consistent with the alleged anti-eugenic goals of RBA bans.

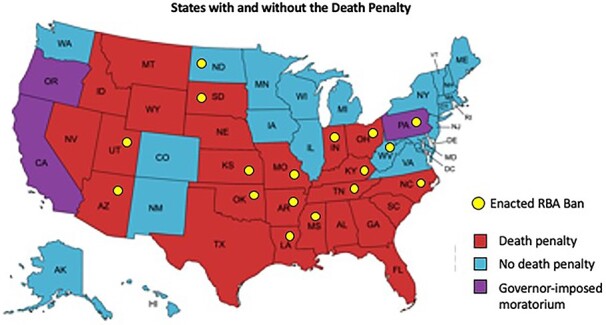

Section B then explores state laws that have eugenic (or anti-eugenic) impacts in a slightly broader sense. The eugenics movement included deeply discriminatory efforts to ‘purify’ the American population by encouraging the presence of favored groups and discouraging that of ‘dysgenic’ groups. As a result, state laws that discourage the groups discriminated against in the eugenics era could also be viewed as eugenic. Thus, this section examines laws that impact (illegal) immigrants, incarceration rates as an indirect measure of state policies related to imprisonment, and death penalty statutes. As expected, it finds that RBA-ban states generally are not anti-eugenic in these areas.

Section C turns to an even broader understanding of eugenics—policies that discourage the thriving and integration of the groups at risk during the eugenics era. Infant mortality rates, for example, are indicators as to whether states promote (or fail to promote) the wellbeing of various groups, including minorities. And pay gaps between women and men are indicators as to whether the state protects equality between the sexes. This Section shows a general, albeit not perfect, trend: states with RBA bans are less likely to have legislation or policies that are anti-eugenic or anti-discriminatory in this broader sense.

I conclude the article by discussing how my findings show that legislators commandeered the term ‘eugenics’ to justify further restrictions of reproductive rights before Dobbs. I argue that this characterization of abortions as eugenic—a feature everyone abhors—has always been an attempt to garner support across the aisle for greater abortion restrictions. It also has been deceptive in suggesting that RBA bans remedy broader concerns surrounding eugenics, when in fact they do little to address or reduce the underlying discrimination and disparities that resulted from eugenics. In fact, they only enhance those disparities.

Even though the Dobbs decision has fulfilled Thomas’s goal of allowing states to ban all abortions, including RBAs, my examination of the way RBA-ban states address (or don’t address) eugenics and discrimination in other areas remains important. While Dobbs resolved the question as to whether RBA bans are unconstitutional,25 my research shows how the use of eugenics to defend these bans distorts both what is horrific about the eugenics movement (by focusing only on abortion) and the abortion debate itself. In misusing the term ‘eugenics’ in service of condemning certain types of, and ultimately most, abortions, this approach confuses the nature of interests at stake. While the distinction between reason-based abortions and all abortions is irrelevant after Dobbs in the most abortion-restrictive states, the eugenics argument on which Thomas et al. rely can influence and oversimply popular discussions about prenatal testing and its purpose26; it can even potentially lead to RBA bans in more abortion-moderate states.

Worse, although Dobbs represents the result of Thomas’s mission to end the right to abortion, the decision exposes everyone, especially the most vulnerable among us, to the threats of eugenics. The constitutional analysis of Roe, as understood until recently, offered a constitutional interpretation that protected against involuntary sterilization. But that reasoning no longer stands. Thomas and his brethren have instead left us utterly powerless under the Constitution against state-imposed eugenic policies, even as he and others rail against eugenics. Irony is an understatement for what this misuse of the term eugenics has wrought.

II. THE THOMAS CONCEPTION OF EUGENICS AND ANTI-EUGENICS

II.A. Prelude to the Thomas Concurrence

Justice Thomas was not the first judge to associate certain types of pregnancy terminations with eugenics. Some courts have used the term descriptively and neutrally to contrast abortions intended ‘to prevent the birth of a defective child’ (‘eugenic’ abortions) from those intended to protect the mother’s health or life (‘therapeutic’ abortions) or ‘performed to limit the size of the family for economic reasons’ (‘socioeconomic’ abortions).27 Others, however, have used the term to critique wrongful birth or life claims—ie lawsuits brought by parents or the child, respectively, alleging that a provider’s negligence deprived expectant parents of the opportunity to terminate a pregnancy based on fetal anomalies.28

For example, in holding that parents could not recover for a wrongful birth claim for a physician’s alleged failure to inform them that their child would be born with birth defects, the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1967 concluded that a ‘child need not be perfect to have a worthwhile life’.29 The court reasoned:

We are not faced here with the necessity of balancing the mother’s life against that of her child. The sanctity of the single human life is the decisive factor in this suit in tort. Eugenic considerations are not controlling. We are not talking here about the breeding of prize cattle. It may have been easier for the mother and less expensive for the father to have terminated the life of their child while he was an embryo, but these alleged detriments cannot stand against the preciousness of the single human life to support a remedy in tort.30

Similarly, in Taylor v Kurapti, a Michigan appellate court held that a claim for wrongful birth could not be brought. The court criticized the phrase ‘wrongful birth’ because it suggests that

the birth of the disabled child was wrong and should have been prevented. If one accepts the premise that the birth of one ‘defective’ child should have been prevented, then it is but a short step to accepting the premise that the births of classes of ‘defective’ children should be similarly prevented, not just for the benefit of the parents but also for the benefit of society as a whole through the protection of the ‘public welfare’. This is the operating principle of eugenics.31

Foreshadowing Thomas’s concurrence, the court then recited the history of eugenics,32 criticizing Justice Holmes for ‘one of the most callous and elitist statements in Supreme Court history’:

[I]t is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.33

The Michigan court reasoned that even if, today, ‘this talk of the “unfit” and of “defectives” has a decidedly jarring ring’, we may not be ‘above such lethal nonsense’, given the potential of genetics advances to identify genes for various medical conditions. Specifically, it worried that allowing wrongful birth claims for the lost opportunity to obtain a ‘eugenic abortion’ is ‘but another short half step from…proposing, for the benefit of the child’s overburdened parents and of the society as a whole, that the existence of the child should not be allowed to continue’.34

II.B. RBA Bans and the Thomas Concurrence

Judge Frank Easterbrook, joined by then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett, was the first to discuss reason-based abortion bans in terms of eugenics. Dissenting from the Seventh Circuit’s denial of a rehearing en banc concerning a different part of an Indiana abortion statute,35 Easterbrook’s opinion challenged the en banc panel’s view that Indiana’s ‘Sex Selective and Disability Abortion Ban’, which prohibits abortions when the provider knows the abortion is sought ‘solely’ based on race, sex, Down syndrome diagnosis or related characteristics,36 was unconstitutional. According to Easterbrook, the Court’s abortion decisions never considered the ‘validity of an anti-eugenics law’, and none of those ‘decisions holds that states are powerless to prevent abortions designed to choose the sex, race, and other attributes of children’.37

Justice Thomas’s Box concurrence builds on Easterbrook’s characterization of the Indiana law as anti-eugenic, albeit it shines a much brighter spotlight on the horrors of the eugenics movement than any prior opinion. Thomas does so, however, with a pointed and inaccurate twist long embraced by some aspects of the anti-choice movement. After devoting only a paragraph to agree with the majority's decision to overturn the injunction regarding statutory requirements for the disposition of fetal remains, Thomas presents his thesis that Indiana’s RBA ban is anti-eugenic:

Each of the immutable characteristics protected by this law can be known relatively early in a pregnancy, and the law prevents them from becoming the sole criterion for deciding whether the child will live or die. Put differently,…[the RBA ban] promote[s] a State’s compelling interest in preventing abortion from becoming a tool of modern-day eugenics.38

Thomas relies on the history of the eugenics movement to argue that ‘the use of abortion to achieve eugenic goals is not merely hypothetical’, but a current threat because the ‘foundations for legalization of abortion in America were laid during the early 20th-century birth-control movement’.39 To make this claim, Thomas focuses to a disproportionate extent on two key figures associated with reproductive freedom: Margaret Sanger, who founded Planned Parenthood and was a leader in the birth control movement, and Alan Guttmacher, future Planned Parenthood President. To be sure, both supported the eugenics movement, but they were not the principal figures behind that movement. According to Thomas’s tale of eugenics, Sanger, whose name he invokes 28 times (not including citations), was a primary force behind the movement, rather than one of many influential figures who supported it. He unabashedly ties Planned Parenthood, the symbol of reproductive rights, to eugenics to argue that reason-based (and perhaps all) abortions are eugenic.

Thomas does offer strands of the more typical and historically accurate narrative. He identifies Francis Galton as the man who coined the term ‘eugenics’ and who promoted efforts to encourage people with ‘desirable qualities’ to reproduce and to discourage the ‘unfit’ from reproducing. And he observes that Galton’s goal was to improve ‘society by “do[ing] providently, quickly, and kindly” “[w]hat Nature does blindly, slowly, and ruthlessly.”’40 In addition, Thomas accurately points out how ‘well embraced’ eugenics theories were, ‘particularly among progressives, professionals, and intellectual elites’.41

His history also correctly underscores the movement’s underlying racism, where anecdotes and statistics were used to categorize racial and ethnic groups in eugenics terms. Although he focuses heavily on eugenic conclusions about African Americans,42 he rightly observes that eugenicists did not just deem certain racial groups to be “unfit.” The “unfit” also included the “‘feeble-minded’, insane’, ‘criminalistic’, ‘deformed’, ‘crippled’, ‘epileptic’, ‘inebriate’, ‘diseased’, ‘blind’, ‘deaf’ and ‘dependent’ (including orphans and paupers).”43

Thomas’s account also includes the shameful legislative strategies to reduce ‘dysgenic’ traits in America: The Immigration Act of 1924, which severely restricted immigration by those who were not from Western and Northern Europe; anti-miscegenation laws;44 laws prohibiting marriage between the ‘unfit’; and mandatory eugenic sterilization laws. He rightly condemns Buck v Bell, as well as Holmes’s eugenic rhetoric45 and ‘full-throated defense of forced sterilization’. As he notes, Holmes’s decision legitimized and contributed to the momentum of the eugenics movement and the involuntary sterilization of as many as 70,000 people in the United States.46

But Thomas’s narrative takes a turn from standard accounts of eugenics in a few ways. First, after correctly noting that support for eugenics ‘waned considerably’ once Americans became aware of eugenic policies in Nazi Germany and scientific understandings demonstrated how problematic the assumptions underlying eugenics were, he claims, with nary a citation, that ‘support for the goal of reducing undesirable populations through selective reproduction has by no means vanished’.47 His primary goal is to suggest that reason-based abortions are a form of such modern-day eugenics.

To make the case that ‘abortion is an act rife with the potential for eugenic manipulation’,48 Thomas flanks his discussion of the main features of the eugenics movement with a diatribe against Margaret Sanger and to a lesser extent Alan Guttmacher. He twice quotes Sanger’s statement that ‘“Birth Control…is really the greatest and most truly eugenic method” of “human generations.”’49 Indeed, he argues, she saw it as more effective than sterilization.50 He also points to her initiation of the ‘Negro Project’, which was intended to ‘promote birth control in poor, Southern [B]lack communities’, and which Sanger described as “‘“the most direct, constructive aid that can be given them to improve their immediate situation.”’”51

Thomas does offer some half-hearted disclaimers, including that W.E.B. DuBois and other Black leaders supported the Negro Project. He also twice concedes that Sanger ‘distinguished between birth control and abortion’, even quoting her as describing contraception as the only thing that ‘can put an end to the horrors of abortion and infanticide’. And finally, he notes that Sanger’s supporters argue her writings ‘should not be read to imply a racial bias’, although it is clear he thinks otherwise.52

Despite these disclaimers, Thomas sees a clear through line between Sanger’s support of birth control and his view that (reason-based) abortions are a form of modern-day eugenics. Even if Sanger ‘was not referring to abortion…, at least not directly’,53 he reasons, her eugenics arguments for birth control ‘apply with even greater force to abortion’.54 If ‘birth control could prevent “unfit” people from reproducing’, ‘abortion can prevent them from being born in the first place’.55 To underscore this assertion, Thomas twice suggests that eugenicists were big proponents of abortion56 and three times references Alan Guttmacher as one such proponent.57 Even if the end of World War II led to a ‘public aversion to eugenics’ and reluctance to use the term, Thomas argues, eugenic desires remain. He points to support for birth control and abortion in the latter half of the 20th century as a means ‘to achieve “population control” and to improve the “quality” of the population’.58 Thus, abortion has the ‘potential…to become a tool of eugenic manipulation’.59

Finally, Thomas devotes the last part of his concurrence to linking contemporary ‘eugenic’ attitudes to abortion and discrimination against Black people, people with disabilities, and females. He argues that the racism of the eugenics movement underlies contemporary support for birth control,60 and that abortion carries those same ‘eugenic’ overtones. His support? The ‘considerable racial disparity’ in who has abortions. Black women, he observes, have abortions at 3.5 times the rate of white women, and Black children in some parts of New York City are ‘eight times more likely to be aborted than white children’.61 Thomas offers no causal explanation for these disparities, no evidence that it is part of a grand plan of modern-day ‘eugenicists’, and indeed, no evidence that people terminate pregnancies on the basis of race. He simply states that ‘[w]hatever the reasons for these disparities’, abortion is a method of family planning of which ‘[B]lack people do indeed “tak[e] the brunt.”’62

With respect to disability, Thomas argues that abortion has become ‘a disturbingly effective tool for implementing the discriminatory preferences that undergird eugenics’.63 Here, he points to the high abortion rates in Europe and the United States for pregnancies in which Down syndrome has been identified.64 And finally, with respect to sex, he describes ‘widespread sex-selective abortions’ in Asia and asserts they are ‘common among certain populations in the United States’.65

Surprisingly, Thomas concurs in the Court’s decision not to grant certiorari with respect to Indiana’s RBA ban. Nevertheless, his concurrence unabashedly lays the groundwork for the Court to uphold those laws (or all abortion bans), eventually. Thomas claims that the Court ‘has been zealous in vindicating the rights of people even potentially subjected to race, sex, and disability discrimination’, and therefore the Court cannot ‘forever’ avoid such issues in the context of abortion.66 Thus, he concludes that ‘[e]nshrining a constitutional right to an abortion based solely on race, sex, or disability of an unborn child…would constitutionalize the views of the 20th-century eugenics movement’.67 In short, he sees the Indiana ban on reason-based abortions as vindicating such constitutional rights.68

Notably, the majority opinion in Dobbs references Thomas’s views in a footnote, citing to his Box concurrence for the proposition that some supporters of ‘liberal access to abortion…have been motivated by a desire to suppress the size of the African-American population’.69 Indeed, the footnote implicitly endorses these views in stating that ‘it is beyond dispute that Roe has had that demographic effect’ because a ‘highly disproportionate percentage of aborted fetuses are Black’.70 Although the majority claims not to ‘question the motives of either those who have supported or those who have opposed laws restricting abortions’, in citing Thomas’s concurrence and presenting those statistics, it hints that a majority of the Court, not just Thomas, endorses a view that abortions themselves are eugenic.

II.C. Historical Inaccuracies

Historians and other scholars have taken serious issue with many of Thomas’s claims, even while noting where his account of eugenics is accurate.71 They have condemned his opinion as a distortion of ‘history in the service of ideology’,72 ‘“historically incoherent,”’73 ‘selective, and incomplete’,74 ‘“really bad history,”’ reliant on ‘“a gross misuse of historical facts,”’ and guilty of the ‘“amateur historical mistake to project early 21st-century right wing views” onto the early 20th century’.75

As Adam Cohen, one of the historians whose work Thomas cites, asserts, ‘Thomas used the history of eugenics misleadingly’ and as ‘a new weapon in the arsenal of the anti-abortion movement’. Cohen notes that.

Thomas relied on a kind of historical guilt-by-association. ‘The foundations for legalizing abortion in American were laid during the early 20th century birth-control movement’, he wrote. The birth-control movement, in turn, ‘developed alongside the American eugenics movement’. Therefore, he suggested abortion is inseparable from America’s history of eugenics.76

Michael Dorf compares this aspect of Thomas’s reasoning to the syllogism in Love and Death, which leads to the conclusion that ‘all men are Socrates’.77

Although Sanger did support eugenics, many scholars reproach Thomas for suggesting her goal in opening a birth-control clinic in Harlem was to discourage reproduction in the Black community. As Professor Melissa Murray points out in Race-ing Roe: Reproductive Justice, Racial Justice, and the Battle for Roe v. Wade,78 Margaret Sanger’s promotion of birth control was much more nuanced and complex. Sanger initially tried to promote family planning by emphasizing feminist goals such as voluntary motherhood and support of women’s sexuality. Unfortunately, these goals did not align with feminism in the early twentieth century, whose call for equality was rooted in ‘the moral superiority of motherhood’ and ‘emphasis on maternal value, chastity, and temperance’.79 Only when it became clear that her efforts to promote birth control did not have the support of the women’s movement did Sanger reframe the argument for contraception in eugenics terms. By tying family planning to eugenics—with its wide appeal, purported scientific validity, and focus on the well-being of the country—Sanger hoped to garner broader support for contraception.80

Scholars also critique Thomas’s suggestion that Sanger was imposing something on the Black community against their will. Historian Daniel Kevles stresses that Sanger’s ‘concern with lower income and immigrant women was to give them control over their lives; and these women were extremely grateful for it’.81 Similarly, Professor Dorothy Roberts writes in Killing the Black Body that ‘Black women were interested in spacing their children and Black leaders understood the importance of family planning services to the health of the Black community’, which then as now faces high rates of maternal and infant mortality.82 Author Harriet Washington describes how Black women embraced birth control because of the career options it provided, including allowing women to enter professional jobs by delaying motherhood until they were ready.83 Finally, Ayah Hurridin, who is writing her Ph.D. thesis on eugenics and the African American community, observes:

History shows that a lot of African Americans thought Margaret Sanger had the right idea. That birth control is not only a way to control reproduction and family size, but also a lot saw it as vindication of black womanhood, coming out of a long history where, during slavery, a lot of black women didn’t have control over their reproduction due to all kinds of horrific sexual violence.84

Many historians also critique Thomas’s insinuation that eugenicists were big supporters of birth control and abortion. According to Kevles, the opinion was “‘ignorant and prejudiced when it comes to birth control’.” For example, prominent eugenicists like Charles Davenport opposed birth control. Many eugenicists feared that “‘the women who would use it were the type of women they would want to encourage to reproduce, so-called ‘better’ women—upper-middle-class women’.”85 Kevles also finds Thomas’s claims “‘wholly inappropriate when it comes to abortion vis-à-vis eugenics’”86 because the leaders of the movement, including Davenport and Harry Laughlin, “were largely opposed to abortion and birth control.”87 As Professor Paul Lombardo puts it, “‘I’ve been studying this stuff for 40 years, and I’ve never been able to find a leader of the eugenics movement that came out and said they supported abortion’.”88 And of course, as even Thomas conceded, Sanger opposed abortion.89

Finally, Professor Murray faults Justice Thomas for overlooking and obscuring ‘the significant history of racialized sterilization abuse in the United States’, which continued long after public support for the eugenics movement waned. Whereas the sterilization efforts during the eugenics movement century were primarily directed at poor white people to protect the public fisc and purify the white race,90 in the second half of the 20th century, states began to repurpose ‘their state sterilization programs to limit reproduction among those who were unduly dependent. . . on the public fisc’, and who were disproportionately women of color. By equating ‘state-sponsored reproductive abuses’ primarily with individual decisions regarding abortion and contraception,91 and overlooking this history, Thomas fails to emphasize ‘the strong correlation between race and socioeconomic status and vulnerability to reproductive control’.92

Not all criticize Thomas’s concurrence, however. Some argue that he ‘was plainly not making the “guilt by association” argument…. Instead, he was showing that eugenics thinking has indeed played a significant role in the thinking of some leading advocates of abortion’.93 Others praise Thomas for exposing many Americans to a needed lesson on eugenics, with which the anti-abortion movement has long been familiar.94 Professor Paulsen contends that Thomas’s account is ‘mostly right’, and that he ‘stopped short of claiming that legal abortion is a racist plot to reduce the African American population’.95 Under his view, even if ‘abortion is not a eugenic conspiracy’, Thomas highlighted the ‘undeniable fact that the aborted are disproportionately racial minorities, female, and those with disabilities’, and that ‘abortions are sometimes had, today, for eugenics reasons—fairly often, even for sex selection and disability-elimination’. Thus, he sees Thomas as correct in showing that abortion is ‘capable of being used as “a disturbingly effective tool for implement the discriminatory preferences that undergird eugenics’.96

Justice Thomas’s arguments linking abortion to eugenics are not new.97 As one historian observes, ‘the discursive use of eugenics to smear anything remotely associated with it, or could be associated with it, has been going on a long time’.98 Indeed, these themes can be found in propaganda from various pro-life groups linking abortion to racial genocide, including the 2009 documentary, Maafa 21: Black Genocide in the 21st Century America.99 Similarly, the Issues4Life Foundation, a faith-based organization that aims to achieve the goal of ‘zero African-American lives lost to abortion or biotechnology’, blames Planned Parenthood Federation of America for the ‘Da[r]fur of America’, ie the high abortion rates in the African-American community.100 Similar propaganda has appeared on billboards in minority neighborhoods with such messages as ‘Black children are an endangered species’ and ‘The Most Dangerous Place for an African American is in the Womb’.101 And, more recently, the use of the slogan ‘Unborn Black Lives Matter’ in response to ‘Black Lives Matter’ furthers this propaganda.102 While most of these messages have come from predominantly white anti-abortion groups, some Black anti-abortion groups share these views, pointing, as Thomas does, to the disproportionate numbers of abortions among Black women.103 Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that these views are not, and have not been, widely held within the Black community.104

All of this is to say that Thomas’s history of eugenics and purported links to abortion based on race, sex, or disability does not capture the nuances of the eugenics era or attitudes toward family planning. As Murray persuasively demonstrates, ‘throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, racialized arguments appeared on all sides of the debate of whether and how to regulate abortion, birth control, and reproduction’.105 But Thomas’s narrow understanding of eugenics,106 which focuses on (reason-based) abortions, is gaining popularity and shaping legislative efforts across the country.

Finally, it is worth pointing out elements of the eugenics era that Thomas does not emphasize. For example, he mentions that eugenic policies focused on the criminalistic elements, but he does not underscore the role of eugenics in the origins of the carceral state. Segregating ‘undesirables’ through imprisonment or institutionalization helped achieve eugenic goals without sterilization. Indeed, scholars argue that, even today, the disproportionate incarceration of minorities functions as a form of ‘new eugenics’.107

In addition, Thomas does not note that the earliest sterilization statutes focused on ‘sex criminals’ and those who were considered to be sexually deviant, ie those whose identities and sexual practices were unconventional. ‘Many of the same eugenics-driven laws that propelled the forced sterilization of so-called “mental defectives” like Carrie Buck also authorized the sterilization, forced commitment, and criminal prosecution of LGBT people’.108 As Nancy Ordover discusses, the eugenicist Albert Moll ‘recognized that any characterization of homosexuality as acquired (and therefore something that could be restrained) could be used to justify legal and criminal penalties’. He, however, viewed ‘the act [of homosexuality/bisexuality] not as criminal but morbid’.109 Concerns among conservatives regarding gay marriage and same-sex couples parenting children today, like the carceral state, may also have their roots in those eugenic notions regarding ‘sex criminals'.

As the next section describes, bills and statutes banning RBAs have proliferated in the last 10 years. After the Thomas concurrence, the anti-eugenic goals of these laws have only become more explicit.

III. THE PROLIFERATION OF RBA BANS

From 1975 to 2009, long before Thomas’s concurrence in Box,110 only 14 RBA bans were introduced, and only two became law: sex-selective abortion bans that passed in Pennsylvania111 and Illinois. The Illinois law was repealed in 1993.112

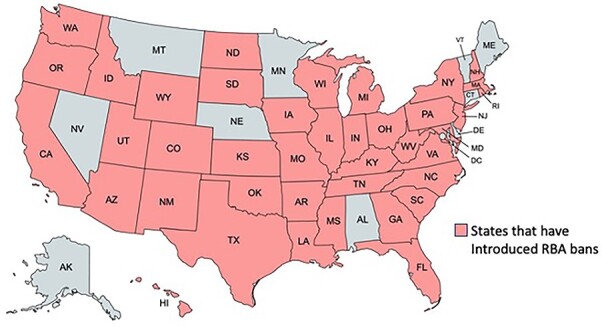

2010, however, marked the beginning of a resurgence of interest in such laws. As Figure 1 shows, since 2010, bills have been introduced across the country in all but nine states and D.C. Table 2a indicates the number of bills (1990) that have been introduced each year between 2010 and 2022, as well as how many are pending, in effect, vetoed, or blocked/enjoined (fully or partially). Not surprisingly, in 2021, following the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the largest number (37) of RBA bans were proposed. Also unsurprising is the distinctly conservative bent in the sponsorship of such laws. Only 21.69 per cent (41) of the 189 bills introduced had democratic sponsors, and only 6.17 per cent (128) of the 2074 total sponsors were Democrats.

Figure 1.

Map of States with Introduced Reason-Based Abortion Bans 2010–2022.

Table 2a.

Summary of RBA Bans Introduced 2010–2022

| Year | Pending | In Effect | Failed | Vetoed | Blocked/ Enjoined | Blocked/ Enjoined in Part | Total Bills Introduced | Enacted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

| 2021 | 17 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 37 | 2 |

| 2020 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 2 |

| 2019 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 4 |

| 2018 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 2017 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3 |

| 2016 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 2 |

| 2015 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 |

| 2014 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| 2013 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 3 |

| 2012 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| 2011 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 2010 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| Totals | 25 | 17 | 141 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 190 | 20 * |

*The total number of states with enacted statutes is 21 counting Pennsylvania’s law, which was enacted before this period.

As of July 2022, 21 RBA bans have been enacted in 17 states (see Table 2b): Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia. Twenty of these laws are currently in effect, and one is partially enjoined.113 Missouri, the only state left with a partial injunction on its 2019 law, instituted a near total ban on abortion, making this injunction irrelevant. Table 2c demonstrates the nature of the prohibited reasons for abortions by state.

Table 2b.

Summary Table of RBA Bans in 2022

| Bans In Effect (Cumulative)** | Partial Blocked/Enjoined | Total Enacted Bans to Date |

|---|---|---|

| 17 AR, AZ, IN, KY, KS, LA, MO, MS, NC, ND, OH, OK, PA, SD, TN, UT, WV |

1 MO |

21 AR, AZ, IN, KY, KS, LA, MO, MS, NC, ND, OH, OK, PA, SD, TN, UT, WV |

**Shows the number of states with enacted bans, some states have enacted multiple bans as indicated by the third column.

Table 2c.

Nature of RBA Bans by State

| State | Sex | Race | Down Syndrome (DS) or Genetic Anomaly (GA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | X | X | X (GA) |

| Arkansas | X | X (DS) | |

| Indiana | X | X | X (DS/GA) |

| Kansas | X | ||

| Kentucky | X | X | X (DS/GA) |

| Louisiana | X (GA) | ||

| Mississippi | X | X | X (GA) |

| Missouri | X | X | X (DS) |

| North Carolina | X | ||

| North Dakota | X | X (GA) | |

| Ohio | X (GA) | ||

| Oklahoma | X | X (GA) | |

| Pennsylvania | X | ||

| South Dakota | X | X (DS) | |

| Tennessee | X | X | X (DS) |

| Utah | X (GA) | ||

| West Virginia | X (DS/GA) | ||

| Totals | 13 | 6 | 14 (7, DS; 10, GA) |

There had been a circuit split as to whether these laws are constitutional, with the Sixth Circuit ruling en banc that Ohio’s ban on abortions based on Down syndrome is constitutional,114 and the Seventh Circuit ruling that the Indiana ban on abortions based on race, sex, and genetic anomaly, which was at issue in Thomas’s concurrence, was unconstitutional.115 Of course, after the Dobbs ruling, abortion bans based on reasons such as race, sex, and genetic anomaly can clearly stand under federal constitutional law if abortion can be banned for virtually any reason from the point of conception.116

Not only has the number of proposals for and enactment of RBA-bans grown in the last decade or so, but there has also been an increase in the use of explicit or implicit references to eugenics in the legislation. As Table 2d shows, of the 21 RBA bans, two have explicit references to eugenics, as do four of the 25 pending bills from 2021 and 2022. In addition, several proposed bills use eugenic-like language, focusing on concerns about discrimination based on race, sex, or disability.

Table 2d.

Summary of Reason-Based Bans

| Pending | In Effect | Passed and Scheduled to Take Effect | Failed | Vetoed | Blocked/ Enjoined | Blocked/ Enjoined in Part | Enacted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Reason-Based Abortion Bans | 24 | 20 | 0 | 141 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Contains ‘Eugenics’ in Text | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Contains Eugenics-Like Language in Text | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

For example, Mississippi’s Life Equality Act of 2020, which prohibits abortions based on race, sex, and genetic anomaly,117 relies heavily on Thomas’s concurrence. Its legislative findings quote Thomas’s description of the Supreme Court as ‘“zealous in vindicating the rights of people even potentially subjected to race, sex, and disability discrimination.”’118 They proclaim that ‘[n]otwithstanding’ state and federal laws that protect ‘the inherent right against discrimination on the basis of race, sex, or genetic abnormality’, ‘unborn human beings are often discriminated against and deprived of life’.119 Finally, they assert that ‘sex-selection abortions continue to occur in the United States’, where the ‘victims are overwhelmingly female’, and that ‘[a]bortions predicated on the presence or presumed presence of genetic abnormalities continue to occur despite the increasingly favorable post-natal outcomes for human beings perceived as handicapped or disabled…’120

While much of the language focuses on discrimination, the stated purpose of this legislation is explicitly anti-eugenic, with quotes from Thomas’s concurrence:

(d) As Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has noted, ‘Each of the immutable characteristics protected by this law can be known relatively early in a pregnancy, and this law prevents them from becoming the sole criterion for deciding whether the child will live or die’.

(e) ‘Abortion is an act rife with the potential for eugenic manipulation’.

(f) The State of Mississippi maintains a ‘compelling interest in preventing abortion from becoming a tool of modern-day eugenics’.121

Tennessee’s ban on abortions based on race, sex, or a Down syndrome diagnosis,122 also quotes Thomas’s concurrence:

As Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his opinion concurring in the denial of certiorari in Box v Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc.,…‘the use of abortion to achieve eugenic goals is not merely hypothetical’. This historical practice of abortion was rooted not in equality but in discrimination based on age, sex, and disability.123

The legislative findings devote three paragraphs to a history of the eugenics movement in the early 20th century, suggesting, much like Thomas’s account, that the primary figures in the movement were Margaret Sanger, who promoted birth control to reduce ‘“the ever increasing, unceasingly spawning class of human beings who never should have been born at all,”’ and Planned Parenthood President Alan Guttmacher, who endorsed ‘abortion for eugenic purposes’ and ‘to prevent the birth of disabled children’.124

As of July 2022, legislatures in three states—Missouri, West Virginia, and Wyoming—introduced four pieces of legislation banning abortions based on fetal abnormalities. The bills in Missouri and West Virginia quote Thomas’s description of reason-based abortions as ‘rife with eugenic potential’.125 West Virginia’s bill went into effect in July 2022.126

Legislatures also drew upon the same language from Thomas’s opinion in Box in several proposed bans in 2021. For example, bills introduced in Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, and West Virginia, which would prohibit abortions based on race, sex, or genetic anomaly, also describe “abortion as rife with eugenic potential.”127 Louisiana’s proposed bill also links abortions to “sterilizing people with disabilities and aborting their pregnancies without consent…based on flawed eugenic principles.”128 A proposed bill in Arizona, titled the Prenatal Nondiscrimination Act of 2021, which would prohibit abortions based on race and sex, expresses the view that “‘sex control [using technology to choose a child’s sex] might lead to…dehumanization and a new eugenics’.”129 Its legislative findings also proclaim that the “history of the American population control movement and its close affiliation with the American Eugenics Society reveals a history of targeting certain racial or ethnic groups for ‘family planning’.” Like Thomas, its findings suggest that this “history likely contributes to the current statistic that a Black baby is five times as likely to be aborted as a White baby, often in a federally subsidized clinic.”130

Also notable is language in many enacted statutes and proposed legislation hinting at eugenic concerns without using the term explicitly. A 2019 Kentucky statute prohibiting abortions based on sex, race, or disability131 describes such abortions as ‘unfairly discriminatory’.132 Comparing this ban to ‘state, federal, and international law [that] supports the rights of all people to dignity, equality, and freedom from discrimination based on sex, race, color, national origin, or disability’, the findings describe the statute as protecting ‘the human rights of unborn children not to be discriminated against’.133

Similar language can be found in a 2019 partially enjoined Missouri statute prohibiting abortions based on a diagnosis of Down syndrome or the sex or race of the fetus.134 The legislative findings allude to the history of eugenics when suggesting that the law is a prophylactic to the ‘historical relationship of bias or discrimination by some family planning programs and policies towards poor and minority populations, including…the nonconsensual sterilization of mentally ill, poor, minority, and immigrant women and other coercive family planning programs and policies’.135 Without ever using the word ‘eugenics’, the findings rely on many of Thomas’s arguments in support of RBA bans. For example, they state that Black or African–American women in Missouri have abortions at roughly three and a half times the rate of white women. They also describe sex-selective abortions as ‘repugnant to the values of equality of females and males’. Finally, the findings state that terminating pregnancies based on Down syndrome is a ‘form of bias or disability discrimination and victimizes the disabled unborn child at his or her most vulnerable stage’, sending ‘a message of dwindling support for’ the ‘unique challenges’ of those with disabilities, fostering ‘a false sense that disability is something that could have been avoidable’, and increasing ‘the stigma associated with disability’.136 While this statute does not use the term eugenics, it uses the same kinds of discrimination arguments that are explicitly tied to eugenics concerns in other RBA bans.

Thomas’s reasoning has not only influenced legislation, but it also appears in judicial opinions in the federal courts. For example, the Sixth Circuit en banc opinion upholding Ohio’s prohibition of abortions based on a diagnosis of Down syndrome hints at the anti-eugenic effects of the law. It claims the law protects the ‘Down syndrome community from the stigma associated with the practice of Down-syndrome-selective abortions’, noting that ‘two thirds of the pregnancies with a fetal diagnosis of Down syndrome are aborted’ in the United States and at higher rates in some other countries. It also asserts that targeting ‘unborn children exhibiting a certain trait…for abortion…sends a message to people living with that trait that they are not as valuable as others’.137

All but one of the concurring judges explicitly references eugenics and makes anti-eugenics arguments for reversing the preliminary injunction of the Ohio law. For example, Judge Sutton queries in his pre-Dobbs concurrence:

How did it happen that an anti-eugenics law is not the kind of law that reasonable people could compromise over in the context of broader debates about abortion policy? For my part, I do not find this case difficult as a matter of federal constitutional law. The United States Supreme Court has never considered an anti-eugenics statute before. Nothing in its abortion decisions indicates that a State may not ban doctors from knowingly performing an abortion premised on the undesirability of the disability, sex, or race of the fetus. The question is not whether the ban counts as an undue burden. The question is whether the undue burden test applies at all. I see no reason that it does.

His concurrence goes on to argue that.

The Ohio law…prevents the medical profession in particular and society in general from knowingly casting aspersions on individuals with Down syndrome—or, worst of all, celebrating the number of Down syndrome births averted.…Ohio does not have to be Iceland.138

Similarly, Judge Griffin writes ‘separately to emphasize Ohio’s compelling state interest in prohibiting its physicians from knowingly engaging in the practice of eugenics’, invoking Justice Thomas’ concurrence in Box and using the word ‘eugenics’ 17 times throughout his opinion (and in all but one paragraph).139 Finally, Judge Bush makes 22 explicit references to eugenics and also follows Thomas’s concurrence in detailing the history of the eugenics movement.140

IV. NARROW AND BROAD CONCEPTION OF EUGENICS AND ANTI-EUGENICS

As we have seen, legislators who proposed and enacted RBA bans, as well as some judges upholding those laws, embrace Thomas’s view of eugenics. Thomas’s account of eugenics is not only grounded in a misleading view of history, but in many ways it is also exceedingly narrow, focusing only on individual reproductive decisions concerning abortion. Even so, it taps into a common view across ideologies that many reprogenetic decisions today, particularly those where abortions are based on particular characteristics of the fetus (sex or genetic anomaly) are a form of individualized eugenics—what Thomas calls modern-day eugenics and others call the new eugenics, liberal eugenics, or neoeugenics.141

The term eugenics, however, can be understood more or less broadly. Literally, it means ‘good birth’ and is therefore often associated with certain reproductive practices. The quintessential examples are laws from the eugenics era that mandated involuntary sterilization of people with ‘undesirable traits’. These laws were a form of negative eugenics in preventing the birth of children with unwanted and allegedly heritable traits. Anti-miscegenation laws and other laws discouraging marriage among those who were deemed genetically unfit also fall into this category because marriage is so closely tied to reproduction, and because these laws sought to prevent reproduction between individuals believed to present heritable risks to future generations. At the other extreme, efforts to encourage procreation among allegedly ‘genetically superior’ individuals also fall within this narrower description of eugenics, albeit these policies are a ‘positive’ form of eugenics in attempting to promote the birth of those with desirable traits.142

Eugenics policies were not all tied directly to reproduction, however. One goal of the eugenics movement was to reduce the number of people with ‘dysgenic’ traits. This led to the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924,143 which limited the influx of ‘biologically inferior’ ethnic groups and privileged the entry of Northern Europeans.144 The impetus for such legislation was rooted in stereotypes cloaked in scientific legitimacy. Legislators relied on the expertise of eugenics leaders who testified that certain ethnic groups, like Southern and Eastern Europeans, were genetically unfit. Indeed, one expert stated that ‘80–90 per cent of Italian, Russian, Hungarian, and Jewish immigrants were feeble-minded’.145 While these laws, of course, influenced future births in America by determining who was allowed in and who would reproduce, they were eugenic simply in attempting to shape the nature of the American population. Thus, eugenics also includes policies that encourage or discourage certain groups from being part of a country’s or locale’s population.

Another way to understand eugenics is in terms of the presence or absence of state control. Some describe individual reproductive decisions aimed at improving the birth of one’s child through genetic testing (pre- or post-conception) as a form of ‘neoeugenics’. They distinguish neoeugenics from laws during the eugenics movement that involved state control over reproduction.146 Thus, some see the ‘new eugenics’ as unproblematic because it is tied to ‘a goal of improvement’ based on free choice.147

Others take issue with assertions that ‘eugenics cannot be an individual project’.148 They argue that individual reproductive decisions, such as terminating pregnancies based on Down syndrome, can ‘collectively have a eugenic impact’ and that ‘systemic biases’ can ‘influence individual abortion decisions’.149 Justice Thomas, for example, condemns certain individual reproductive decisions as an extension of the same attitudes that motivated the eugenics movement. Others cite concerns that some individual reproductive decisions can encourage a kind of perfectionism and challenge parents’ ability to ‘appreciate children as gifts [and] to accept them as they come, not as objects of our design or products of our will or instruments of our ambition’.150 Others critique these decisions as commodifying reproduction151 or promoting ableism and devaluing or discriminating against those with disabilities.152 Indeed, some of the concerns about neoeugenics transcend ideology and are part of both liberal153 and conservative critiques.154

A definition of eugenics that is limited to state action, however, does not capture all that was problematic in the eugenics movement, including the discriminatory views underlying some of the policies. Moreover, it suggests a distinction that is not as sharp as some suggest. Although state-mandated involuntary sterilization was one of the most abhorrent aspects of 20th century eugenics,155 the movement also encouraged individual eugenic decisions.156 Indeed, Francis Galton, the father of eugenics, saw eugenics’ greatest promise exercised at the individual, as opposed to state, level, where informed individuals would make the ‘right’ procreative choices.157 England, where eugenics originated,158 focused far more on promoting eugenics through public education than compulsory measures.159

Eugenics therefore can include not only state action intended to control reproduction or population characteristics, but also disparate impacts of state policies on various populations. Although, in one sense, Justice Thomas adopts a narrow definition of eugenics by focusing solely on reason-based abortions, in another sense, his understanding of eugenics is quite broad in focusing on the disparate impacts of abortions, at least with respect to race. Whereas he points to concerns about individual decisions to terminate pregnancies based on sex or genetic anomalies, his concern about ‘race-based’ abortions does not focus on individual decisions to terminate pregnancies based on race or ethnicity. Instead, he focuses on the disparate impact of abortions generally. In other words, his concern is that abortions themselves are disproportionately prevalent among people of color and are therefore, in his view, eugenic with respect to race. In noting that Black children are ‘eight times more likely to be aborted than white children’ in some parts of New York City,160 he focuses not on policies aimed at increasing abortions among Black people, but on the disparate impacts that arise for ‘[w]hatever…reason’.161 Thus, under Thomas’s understanding of the term, eugenics can arise when a confluence of factors results in a disproportionate impact on a group harmed in the eugenics movement, even if no particular policy is geared toward encouraging that result. This viewpoint is quite a broad understanding of eugenics, indeed.

Although Thomas relies on both narrow and broad conceptions of eugenics, his vision of appropriate anti-eugenic remedies is quite narrow. He urges state control over reproductive choices regarding abortion to counter the ‘modern-day eugenics’ that he believes is inspired by the eugenics movement. There is, of course, tremendous irony in such a remedy, given that one of the horrors of the eugenics movement was state control over reproduction. The only difference between state control over reproduction advocated by Thomas’s narrow vision of anti-eugenics and that of the eugenics era is that the latter prohibited reproduction and the former forces reproduction.

If we are to take Thomas’s concerns about modern eugenics seriously, including worries about the disparate rates of abortions among minorities, a broader vision of anti-eugenic remedies is required. If the worry is that sex-selective abortions and abortions based on genetic anomalies are a form of eugenics and that a disproportionate rate of pregnancies among Black people will be terminated, prohibiting reason-based abortions will not remedy the problem. RBA bans will not change the underlying societal and systemic forces that lead to a disparate rate of abortions among people of color. Moreover, there is simply no evidence that people decide on the basis of race to terminate a pregnancy.

In fact, these anti-eugenic efforts blithely ignore the broader social circumstances that impact the very groups the laws claim to protect. For example, the fact that abortions are more prevalent among people of color and low-income people has to do with several factors, including ‘the particular difficulties that many women in minority communities face in accessing high-quality contraceptive services and in using their chosen method of birth control consistently and effectively over long periods of time’ and the ‘significant racial and ethnic disparities’ that have persisted within health care generally.162 RBA bans do nothing to address those disparities or to decrease the proportion of abortions in minority communities.

The narrow ‘anti-eugenic’ efforts of RBA bans also do little to support disability rights or contemplate how state policies might impact a parent’s ability to care for a child, let alone one with a disability. The bans discourage open communication between provider and patient, making it difficult for patients to obtain ‘comprehensive and reliable information’ critical to making an informed decision whether to continue a pregnancy when a disability has been diagnosed.163 The bans do not promote the births of children with disabilities by offering support that would make those choices viable or more palatable.164 Nor do the bans consider how they might disproportionately impact lower-income people—many of whom are people of color—who face disproportionate obstacles in raising a child with a disability. Finally, bans on sex-selective abortion do not address societal attitudes that counteract concerns about the inequality that allegedly motivates them.

Limiting control over reproduction simply does not remedy many of the eugenics concerns Thomas raises. In fact, it exacerbates them. Being denied access to an abortion by law, whatever the reason for seeking an abortion, will disproportionately harm low-income and minority communities. Unlike people with means, their ability to travel to locales where abortions are legal is limited. Nor will they be as likely to have the resources to care for the child they are forced to bear. As a result, they face increased health risks, stress, and economic instability. Moreover, the wellbeing of the children they already have is endangered. Indeed, these laws can impact infant mortality rates,165 which are disproportionately high among minorities. Surely, concerns about infant mortality should be at least as serious as concerns about abortion rates in minority communities. In short, RBA bans do little to help, and they even harm, the very groups they claim to support.

In contrast, a broader conception of eugenics (and anti-eugenics) considers whether state policies promote (or disrupt) the capacity of different populations to live healthy lives, to reproduce, and to care for their children. Under this vision, anti-eugenic remedies would address the kinds of discrimination and disparities that Thomas and others believe justify RBA bans. The narrow conception of eugenics focuses on abortions and tries to counter eugenics with RBA bans. In contrast, the broader conception focuses on remedying systemic forces that can result in disparities and discrimination regarding the populations targeted in the eugenics movement: minorities, low-income individuals, women, the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities, and immigrants. Indeed, one could argue that policies focused on reproductive and health justice are perhaps the best antidote to eugenics under this broad conception hinted at by Thomas.

This broader conception of eugenics is consistent with the idea that the government’s role in eugenics ranges from mandatory sterilization of ‘undesirable’ groups at one extreme to government policies that have disparate impacts on the well-being and populations of the same kinds of groups that were targeted in the eugenics movement at the other extreme. In between is the willingness of states to allow certain individual ‘eugenic’ practices. One might conceptualize these different kinds of eugenics policies in ever-broadening circles.

At the center are policies that promote or discourage the reproduction or birth of certain types of people. Mandatory sterilization laws fall in this circle as a form of negative eugenics. So too do prohibitions of conjugal visits because they preclude procreation by certain classes of people—prisoners—who are disproportionately minorities and low-income individuals.166 As noted earlier, incarceration has played a central role in achieving eugenic goals.167 Incest prohibitions similarly fall in this category because they are based in part on concerns that genetically related individuals have a heightened risk of having children with birth defects.168

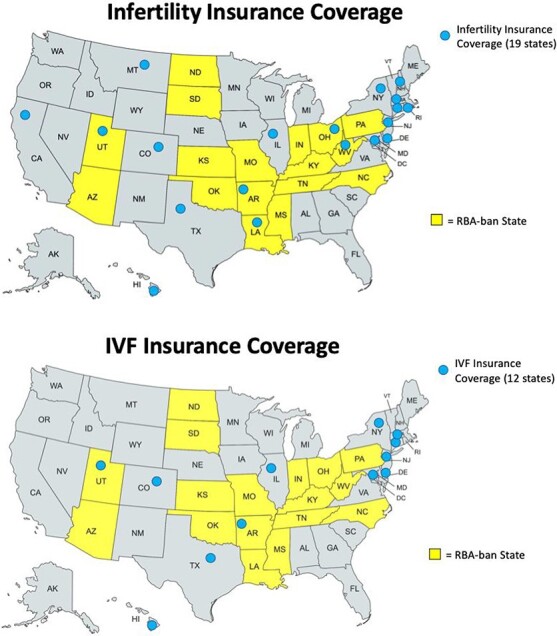

In that same circle are also policies that affect access to assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Dean Judith Daar argues that policies that make it harder for certain groups to access, or that do not assist them in accessing, reproductive technologies are a form of eugenics. As she writes, the ‘true eugenic effect of ART is not in its use but in its deprivation’.169 If laws prohibit certain forms of ART generally or for particular groups, they can have eugenic and discriminatory impacts. For example, certain states prohibit people who are unmarried from accessing some forms of ART (sometimes focusing only on heterosexual marriage), which has a disproportionate impact on access to this technology by low-income individuals, people of color, for whom marriage is less common, and gay people. Similarly, a state’s failure to provide affirmative assistance for ART can be eugenic. Given the high costs of some forms of ART, like in vitro fertilization (IVF), and the disproportionate rate of infertility among people of color,170 ART services are least likely to be accessible to people of color and lower socio-economic groups. States that do not mandate insurance coverage of fertility treatments discourage reproduction among the infertile with the least means, whereas states that provide such mandates are anti-eugenic in broadening the scope of individuals who can reproduce. Similarly, laws that restrict access to surrogacy services or that make it difficult to guarantee legal parentage in using surrogacy may be eugenic in making it more difficult for same-sex couples and single individuals to reproduce. Laws that allow for child abuse charges based on substance abuse also fall within this narrower definition of eugenics because they make reproduction and parentage disproportionately harder for some groups.

Expanding the circle of eugenic (or anti-eugenic) policies a bit more broadly includes those that impact the nature of a jurisdiction’s population. In the eugenics era, immigration policies influenced the ethnic composition of America, which of course also affected who would reproduce.171 Like the Immigration Act of 1924, these restrictions can be explicit in prohibiting certain groups from entering a country. But they can also be more indirect, through state laws that encourage or discourage immigrants from becoming residents by being, respectively, more or less supportive of immigrants. Incarceration can also have eugenic impacts in that it essentially deters reproduction by certain groups of individuals, a disproportionate percentage of whom are people of color.172 So can the death penalty. While one might argue that this broader conception of eugenics really describes concerns about inequality and discrimination, the reality is that immigration policy and the carceral state were explicitly central to eugenics, even if also rooted in deeply discriminatory views. Thus, it is impossible to separate out eugenics from discrimination in this context.

An even broader circle of eugenics includes policies that have the effect of promoting (positive eugenics) or discouraging (negative eugenics) reproduction among certain groups. For example, the government can impose measures that discourage or encourage the birth of children in certain socioeconomic groups through tax breaks and welfare penalties,173 or that encourage or discourage certain types of groups from reproducing based on the extent of state welfare benefits.174 Rather than exploring those policies, I looked to infant mortality as the best indirect measure of state efforts to promote the wellbeing of children, generally, and minority children, specifically. If, as Thomas suggests, the disproportionate impact of abortions among people of color is eugenic, surely high infant mortality rates of minorities and disparate rates are similarly eugenic. These rates can therefore function as a measure of sorts as to whether states have anti-eugenic policies in the broader sense of the term. Again, one might argue that these measures reflect concerns about racial and social inequality, rather than eugenics per se. But as noted earlier, the analysis in this article is in direct response to Thomas’s vehement assertions that abortions are eugenic given the disproportionately high rates of abortion in minority communities. Moreover, eugenic policies were explicitly directed at reducing the presence of certain ethnicities in the population; thus, my analysis considers infant mortality rates (IMRs) in all RBA-ban states, not just those with race-based abortion bans.

Finally, to the extent that reason-based abortions are eugenic in discriminating based on sex, policies that promote women’s wellbeing and thriving can be viewed as anti-eugenic in this broader sense. For example, policies that support equal pay can impact discrimination based on gender. Pay disparities, therefore, offer some insight as to whether the state generally is addressing equality between men and women. Here again, one might argue that laws that ban sex-selection are less motivated by concerns about eugenics per se than by concerns about discrimination, despite Thomas’s (and some states’) description of them as eugenic. This critique is more powerful than the same critique with respect to race, given that eugenics policies did not seem to be directed at eliminating women. Thus, I compare pay gaps and laws related to these gaps in states with RBA bans generally as well as in those with bans against sex selection.

Using these different conceptions of eugenics (and anti-eugenic remedies), my research set out to test my hypothesis that states with RBA bans are not likely to impose broader anti-eugenic antidotes. To test that hypothesis, my research assistants and I examined various state laws and policies related to these different conceptions of eugenics and anti-eugenics. As the next section describes, we found trends that supported my hypothesis among most (but not all) measures.

V. ARE RBA-BANS STATES TRULY ANTI-EUGENIC?

The empirical analysis described below focuses on legislation and policies in a range of areas that can have eugenic-like or anti-eugenic effects with respect to the various conceptions of eugenics discussed in Part IV. Section A examines laws related to the narrowest conception of eugenics: laws that impact who reproduces and how. This section includes laws concerning sterilization, conjugal visits, incest, assisted reproductive technology, substance use during pregnancy, prenatal information laws, and bans on wrongful birth and life claims. Section B examines laws that fall within the slightly broader understanding of eugenics: those that influence who makes up the population, such as laws or policies that discourage the presence of immigrants; incarceration rates, which disproportionately impact minorities and generally prevent their ability to reproduce; and the death penalty, which influences who lives or dies. Finally, Section C explores the broadest circle of eugenics (or anti-eugenics) by examining infant mortality rates, an indirect measure of a state’s promotion of the well-being of children and mothers, and pay gaps, which are indirect measure of efforts (or lack of efforts) to address gender equality.

I begin with several caveats. First, I do not claim that states without RBA bans are aggressively anti-eugenic. Indeed, I suspect that the concept of eugenics does not play a large role in the policies enacted in those states. Instead, my research is aimed at examining whether states that enact RBA bans, allegedly based on concerns about eugenics (or discrimination), demonstrate those concerns more broadly or only with respect to abortion. While in some areas I found that states without RBA bans have policies that are anti-eugenic (or anti-discriminatory), in some instances they also have arguably eugenic-like laws. That does not undermine my critique, which focuses on whether states with RBA bans are consistent in their expressed concerns about eugenics (or discrimination) in enacting those laws.

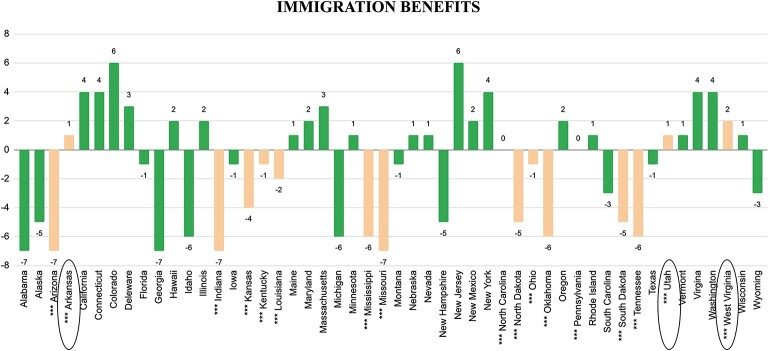

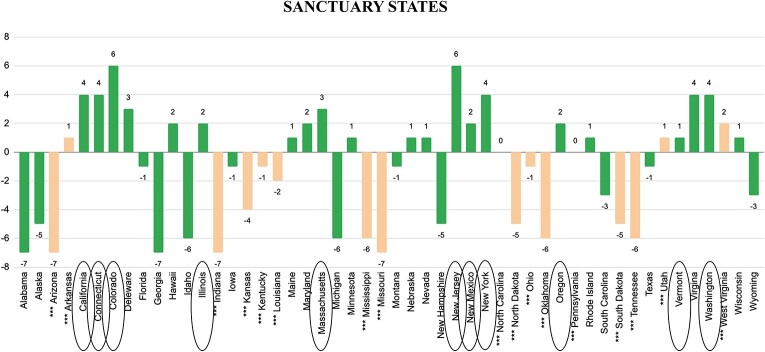

Second, I focused largely on legislative decisions because RBA bans are, of course, enacted by legislatures. Thus, I wanted to compare the presence or absence of different kinds of potentially anti-eugenic legislative efforts within these states. But the focus was not exclusively legislative. Third, given the small numbers (only 17 states have enacted RBA bans) and very different kinds of measures, I did not attempt to determine whether the differences were statistically significant. Fourth, in examining state legislation and policies in states with and without RBA bans, it was difficult to make meaningful year-by-year comparisons because the RBA-bans and other laws were sometimes enacted at different times. Thus, my focus is largely on legislative trends in the last 5–10 years, which is the period when the RBA bills and laws have proliferated. The goal of the research is not to offer a definitive statistical comparison, but instead to get a sense of general trends with respect to states with RBA bans.