Abstract

Soil fungi play indispensable roles in all ecosystems including the recycling of organic matter and interactions with plants, both as symbionts and pathogens. Past observations and experimental manipulations indicate that projected global change effects, including the increase of CO2 concentration, temperature, change of precipitation and nitrogen (N) deposition, affect fungal species and communities in soils. Although the observed effects depend on the size and duration of change and reflect local conditions, increased N deposition seems to have the most profound effect on fungal communities. The plant-mutualistic fungal guilds – ectomycorrhizal fungi and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi – appear to be especially responsive to global change factors with N deposition and warming seemingly having the strongest adverse effects. While global change effects on fungal biodiversity seem to be limited, multiple studies demonstrate increases in abundance and dispersal of plant pathogenic fungi. Additionally, ecosystems weakened by global change-induced phenomena, such as drought, are more vulnerable to pathogen outbreaks. The shift from mutualistic fungi to plant pathogens is likely the largest potential threat for the future functioning of natural and managed ecosystems. However, our ability to predict global change effects on fungi is still insufficient and requires further experimental work and long-term observations.

Citation: Baldrian P, Bell-Dereske L, Lepinay C, Větrovský T, Kohout P (2022). Fungal communities in soils under global change. Studies in Mycology 103: 1–24. doi: 10.3114/sim.2022.103.01

Keywords: drought, elevated CO2, global change, mycorrhiza, nitrogen, deposition, warming

INTRODUCTION

Over the past century, CO2 levels have steadily increased, and global temperatures have risen accordingly. The climate is predicted to continue to change, with increased variability in rain and temperature extremes, both inter- and intra-annually (IPCC 2014, Lee et al. 2021), and affect the whole biosphere including soils. In addition to the changing climate, it is the change of global atmospheric nitrogen (N) deposition that is perhaps the most threatening global phenomenon. It has increased from 34 Tg N/y in 1860 to 93.6 Tg N/y in 2016 (Ackerman et al. 2019) and is predicted to continue increasing worldwide as the result of human activity. Whether soils will become a source or sink of greenhouse gases under future climate scenarios is difficult to predict due to unclear changes in soil carbon and nitrogen pools, and differences in microbial responses between ecosystems and locations (Jansson & Hofmockel 2020), but there is a justified concern that soils will be heavily affected.

Fungi are eukaryotic microorganisms that play multiple fundamental roles related to the future of soil health. As major decomposers of organic matter, mutualists, or pathogens, fungi significantly influence plant health, carbon mineralisation and sequestration, and act as important regulators of the soil carbon balance (Crowther et al. 2016). It is thus important to determine how climate and other global change factors affect future soil fungal communities. The responses of the plant associated guilds to global change factors will likely be of particular interest due to their effects on plant communities. Mycorrhizal fungi act as mutualistic symbionts to plants, providing access to critical nutrients and can ameliorate abiotic stressors associated with climate change, such as heat and drought (Redman et al. 2002, Kivlin et al. 2013). Plant pathogenic fungi, on the other hand, may opportunistically attack plant hosts that are under stress due to the rapid change in their environment (Juroszek et al. 2020, Desaint et al. 2021). Therefore, soil fungi, particularly plant associated guilds, mediate the effects of global change on natural vegetation and agricultural crops in multiple ways.

In addition to direct effects, climate change can indirectly affect soil fungi through shifts in soil chemistry and vegetation structure (Tedersoo et al. 2014, Větrovský et al. 2019, Zhou et al. 2020). It is thus important to understand how global change affects soil fungi. Even though this question has been repeatedly addressed in many contexts and settings in the past, it is still difficult to give a general answer. Soil is the habitat with the highest fungal diversity (Baldrian et al. 2021) and generalisations based on the observed response of individual species are difficult. This high diversity is associated with high levels of functional redundancy in the communities of saprotrophic as well as symbiotic fungi (Žifčáková et al. 2017). Consequently, loss of some species may in theory be replaced by other taxa. However, the critical level of species loss with consequences for ecosystem processes remains largely unknown. Additionally, the diversity, and dependence on plant hosts, of fungal lifestyles (i.e., free-living saprotrophs, mutualistic symbionts and plant pathogens) affect fungal species responses to climate change.

In this review, we will discuss the links between soils, plants, and fungi to explore the paths by which global change affects fungi and their roles in soils. We will also estimate taxon realised niche space to make predictions about the relative sensitivity of various fungi to global change. Lastly, we will use the accumulated information from experimental manipulations of ecosystems to find general patterns in fungal responses to individual global change factors. For simplicity, we will cover only selected global change processes, namely the increasing CO2 levels, warming, reduction in precipitation and N deposition (Fig. 1) since these effects are general and long-lasting. While there is a whole suite of other important phenomena linked with global change, such as land use change, biological invasions, increased fire frequency or increased phosphorus (P) input, these factors are very often geographically local or appear at limited temporal scales which makes the predictions of their effects on fungi difficult. This review adds to our knowledge of belowground communities’ responses to global change by focusing on soil fungi, comparing the possible and current responses of plant pathogens to that of mycorrhizal symbionts, leveraging estimates of fungal guilds realised niches to predict their responses, and only synthesising studies that impose realistic global change manipulations.

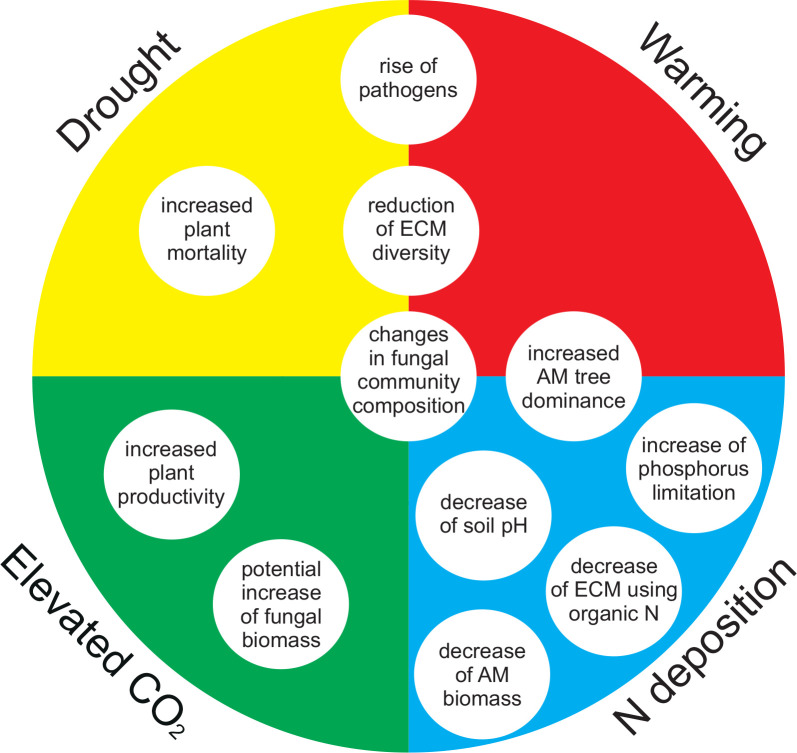

Fig. 1.

Major current and predicted responses to global change factors. Responses to each factor is represented by the location within each section with responses spanning multiple sections indicating the importance of multiple climate change factors.

Fungi and their climatic niche

Utilisation of the niche concept is one approach to predicting the response of fungi to climate change: if we understand the constraints for fungal life, we can identify and localise the environments where they can live. The concept of the ecological niche provides a framework for understanding resource partitioning by organisms and emergent patterns of coexistence and distribution (Macarthur & Levins 1967). Realised niches define the conditions under which organisms can survive and reproduce in the presence of biotic interactions while fundamental niches are defined in the absence of biotic interactions. While the realised niche can be derived from a species’ distribution and abundance across habitat properties (Veresoglou et al. 2012, Davison et al. 2021), characterisation of the fundamental niche is more difficult, because it requires experimental investigation of responses to environmental gradients (Lekberg et al. 2007). However, knowing parameters of the fundamental niches of species would be a valuable tool for the prediction of species’ responses to changing abiotic environments. The fundamental niche provides information on species’ potential responses without the influence of biotic interactions, which must also be expected to change along with abiotic changes (Blois et al. 2013).

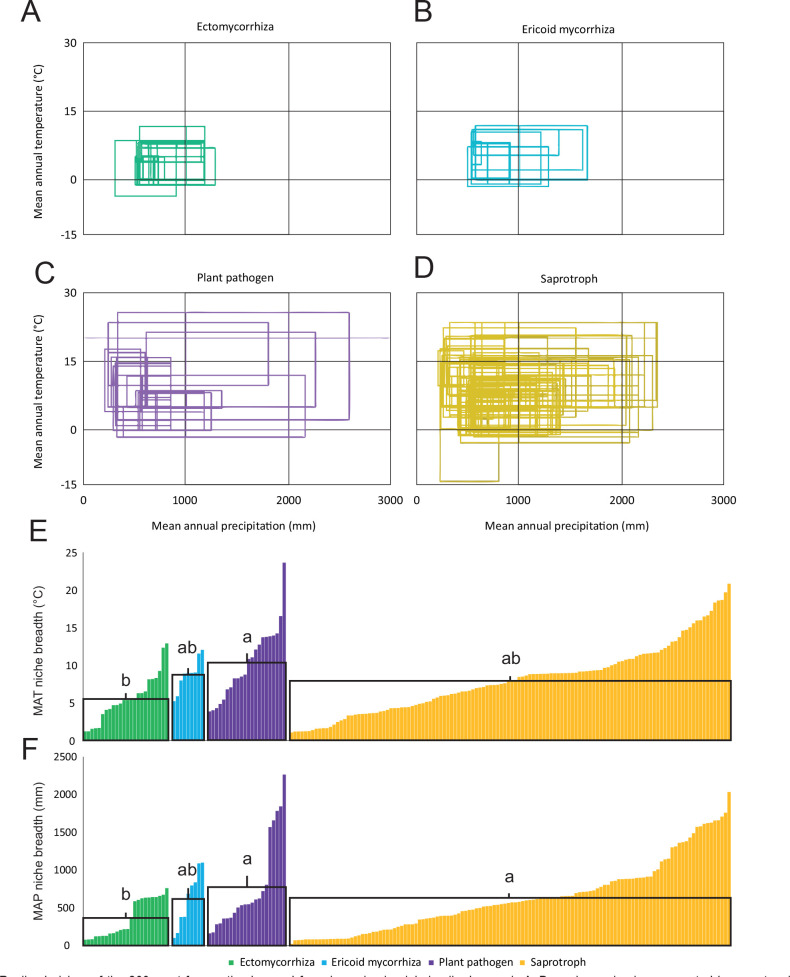

In a global metastudy of soil fungal occurrences using available high-throughput sequencing data, climatic factors contributed, on average, 40–80 % of total explained variability, substantially more than the soil and vegetation properties (Větrovský et al. 2019). Though climatic factors are generally found to be among the most important drivers of global fungal composition, their relative importance varies between studies. For example, Bahram et al. (2018) found that soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio was the most important driver of fungal abundance, taxonomic and gene composition while Tedersoo et al. (2014) found that soil pH was a major driver of many fungal guilds. Of the climatic factors tested, Větrovský et al. (2019) found that mean temperature of driest quarter, precipitation seasonality, mean temperature of wettest quarter, precipitation of coldest quarter and diurnal temperature range were most often the strongest predictors of individual species distributions. Here we used mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) to define species realised niches because these metrics are the most widely used and intuitive defining features of biomes and local climates, are known to affect both soil biota and plants (Jetz et al. 2012, Thompson et al. 2017) and MAT was identified as the strongest predictor of the local distribution of macrofungi within Norway (Wollan et al. 2008). If we define the breadth of the realised climatic niche as the range of MAT / MAP where 90 % of occurrences are observed, fungal species typically inhabit soils within 5–15 °C difference in MAT and 300–1 200 mm difference in MAP (Větrovský et al. 2019), although niche breadth varies largely among individual taxa (Fig. 2). When we compared the 200 most common soil fungi (taxa occurring in > 99 samples worldwide) based on their membership in ecological guilds, the mean annual temperature at the location of occurrence was lowest for ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi followed by ericoid mycorrhizal (ERM) fungi, saprotrophs, and plant pathogens while there was less variation between guilds in the observed mean annual precipitation (Table 1). More importantly, the size of the realised temperature and precipitation niche (the range of MAT and MAP between the first and the ninth decile of all observations) was smaller in ECM fungi than in saprotrophs, ERM fungi, and plant pathogens (Table 1; Fig. 2; Větrovský et al. 2019). Narrow breadth of the temperature niche in ECM fungi across climatic gradients was also observed within a smaller geographic extent spanning Japan (Miyamoto et al. 2018).

Fig. 2.

Realised niches of the 200 most frequently observed fungal species in global soils. In panels A–D, each species is represented by a rectangle representing the lower and upper decile of the mean annual precipitation (MAP) and mean annual temperature (MAT) of locations from where it was reported. Colours indicate ecological guild membership: A) green – ectomycorrhizal fungi (n = 24), B) blue – ericoid mycorrhizal fungi (n = 9), C) purple – plant pathogens (n = 22), and D) yellow – saprotrophs (n = 125). The distribution of fungal species niche breadth in E) MAT and F) MAP with color representing guilds and pairwise significant difference between means represented by letters. Individual species are represented with columns. Data from (Větrovský et al. 2019).

Table 1.

Realised niche of fungal guilds of the 200 most common soil fungi from Větrovský et al. (2019). The centre of the niche space is represented by the mean guild Mean Annual Temperature (MAT) and Mean Annual Precipitation (MAP) while the size is represented by the range of MAT and MAP between the first and the ninth decile of all observations.

| Fungal Guild | n | Mean MAT (mean ± SD °C) | Mean MAP (mean ± SD mm) | Range MAT (°C) | Range Mean Annual Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECM) | 24 | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 714 ± 124 | 5.5 | 365 |

| ericoid mycorrhizal (ERM) fungi | 9 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 838 ± 194 | 8.7 | 616 |

| saprotrophs | 125 | 7.7 ± 3.3 | 809 ± 249 | 7.9 | 630 |

| plant pathogens | 22 | 8.1 ± 3.7 | 807 ± 316 | 10.3 | 774 |

Since plant pathogens tend to inhabit warmer areas, and individual species extend both into drier and wetter climates than the ECM fungi (Fig. 2), warming will likely more negatively affect plant-beneficial fungi than plant pathogens (Větrovský et al. 2019). Supporting our prediction of increased soil pathogens, a recent global model of current and projected distributions of plant pathogens showed likely increases in pathogen abundance with MAT predicted to be the major driver (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2020a). Furthermore, there is evidence that the niches of pathogens may lack trade-offs between biotic and abiotic niche breadths (Chaloner et al. 2020) and may be more labile than that of plant mutualists such as AM fungi (Bebber & Chaloner 2022) suggesting that pathogens may adapt more rapidly to future climates than plant mutualists. It should be noted that the niche concept can be, in theory, extended to other global change factors as well. For example, the response of ectomycorrhizal fungi to nitrogen availability is known for several taxa (van der Linde et al. 2018). However, the limited number of species with reasonable information on their niche breadth, and missing data on local N availability (which exhibits much higher spatial variability than climate), make this concept at present unusable for predicting responses to altered N.

Ecological guilds of fungi and global change

As already discussed, global surveys of soil fungal occurrences in the GlobalFungi database (Větrovský et al. 2020) show that members of various fungal guilds differ in the size of their climatic niche. Moreover, the level of dependence on vegetation varies from obligate biotrophs to free-living fungi. Due to this, global changes are expected to affect various ecological guilds of soil fungi (ECM fungi, AM fungi, ERM fungi, plant pathogens and saprotrophs) differently, affecting their relative share or community composition. These shifts may subsequently result in changes in various ecosystem processes such as decomposition rate or plant performance.

Importantly, climate change-driven shifts in plant communities may lead to shifts in the host availability affecting those fungi that have a narrow host range. With increasing warming, some alpine communities have seen the replacement of forbs with deep rooted grasses (Liu et al. 2018) and increasing nitrogen deposition can lead to reduced species richness though this effect depends on ecosystem characteristics, such as mean annual precipitation (Clark et al. 2007). Altered environmental conditions promote not only natural range shifts of plants species (Rudgers et al. 2014), but also enable naturalisation of alien plant species outside their native distribution range (Seebens et al. 2015). Such events can affect local ecosystems and their fungal components in several ways: by competition for resources, by the introduction of novel fungal species (such as mycorrhizal symbionts or pathogens), or by selective recruitment of root-associating fungal species already present in the local pool by the alien plants (Rudgers et al. 2020, Vlk et al. 2020a). Because of all these factors, changes in local fungal communities are expected as has been already observed for plant introductions (Vlk et al. 2020b).

Due to the complex effects of N on soil chemistry and vegetation, and the fact that mutualistic mycorrhizal fungi mediate its transfer to plants, change in atmospheric deposition is perhaps the factor with greatest importance for guild composition of soil fungi (Fig. 1). Indeed, nitrogen addition to 25 grasslands distributed across four continents led to the increase of fungal pathogens, although it did not significantly affect AM fungi and saprotrophs. These guild level responses were primarily mediated through nutrient-induced shifts in plant communities (Lekberg et al. 2021). On the other hand, no consistent shifts in guild composition were observed across N-supplemented forests in the USA (Moore et al. 2021).

Among the various aspects of global change, changes in climate lead to severe ecosystem alterations. Forests are already facing increasing lengths of heat waves with unprecedented increases of temperature in high latitudes combined with long drought periods. This high level of climate stress likely increases the vulnerability of forests to disturbances including tree dieback and forest fires (Fig. 1; Allen et al. 2010). These severe forest disturbances were shown to result in a shift of fungal communities from those dominated by ectomycorrhizal fungi in undisturbed forests to those dominated by saprotrophs in disturbed forests (Štursová et al. 2014, Rodriguez-Ramos et al. 2021) as a response to changes in primary productivity.

Mycorrhizal plant symbionts

Geographic distributions of plants with various mycorrhizal symbioses show climate-driven patterns. Temperature-related factors have been found to be the main predictors of the distributions of plant species forming AM, ECM, and ERM symbiosis. Recent models show AM plants to be favoured by warm climates, while dominance of ECM plants (and to some extent ERM plants) is more favoured by colder climates (Barcelo et al. 2019). Ectomycorrhizal symbiosis dominates forests in which seasonally cold and dry climates inhibit decomposition and is the predominant form of symbiosis at high latitudes and elevation. AM trees dominate in grasslands and the warm-and-wet climates of tropical forests where enhance decomposition is typical (Steidinger et al. 2019). Warming can significantly alter the distribution of mycorrhizal host plants, with likely subsequent impacts on the proportion of various guilds of mycorrhizal fungi. In addition to warm climates, AM fungal colonisation has been found to be strongly related to soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio and highest at sites featuring continental climates with mild summers and a high availability of soil nitrogen (Soudzilovskaia et al. 2015). In contrast, the intensity of ectomycorrhizal infection in plant roots maybe more related to soil acidity, soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio and seasonality of precipitation and is highest at sites with acidic soils and relatively constant precipitation levels (Soudzilovskaia et al. 2015). As such, root colonisation by both guilds is predicted to respond to climatic factors and N deposition.

AM fungi primarily rely on inorganic forms of N (Phillips et al. 2013) or small organic N compounds (Whiteside et al. 2012). In contrast, some ECM fungi are thought to rely more heavily on organic N sources (Phillips et al. 2013), having a greater capacity to invest in N-degrading extracellular enzymes that access complex organic forms of N in soil, such as proteins and chitin (Fernandez & Kennedy 2016). ECM fungi are thus more associated with slower decomposition of soil organic matter and increased soil carbon (C) storage (Averill et al. 2014, Averill & Hawkes 2016, Fernandez & Kennedy 2016), potentially by competing with free-living soil microbes for organic N resources. These distinctions between AM and ECM fungi lead to two important predictions: (a) that inorganic N inputs to ecosystems will favour AM-associated trees at the expense of ECM-associated trees, and (b) that inorganic N-driven declines in ECM fungal abundance will reduce the belowground C storage capacity of the forest biome (Fig. 1). Indeed, recent nitrogen deposition across USA favoured the expansion of AM trees at the expense of ectomycorrhizal trees, and was spatially correlated with reduced soil carbon stocks (Jo et al. 2019). This implies that future changes in nitrogen deposition may further turn the balance between AM and ECM fungi in forest ecosystems (Averill et al. 2018).

Ectomycorrhizal fungi

Despite the potential for climate change driven replacement of ECM with AM trees, most ecosystems are dominated by either ECM plant symbionts (in most temperate and boreal forests worldwide) or AM symbionts (in natural grasslands, croplands and tropical forests). Therefore, relative abundance of each guild or the change of within-guild species composition are the most likely responses. While shifts in dominant mycorrhizal type mediated by global changes will likely result in changes in nutrient cycles and soil carbon storage, consequences of potential shifts of within guild species composition are less clear.

Based on the assessment of present climatic drivers of ECM fungal distribution, under future climate scenarios North American Pinaceae forests are predicted to see as high as 26 % declines in ECM fungal species richness within 50 years, although there is a high level of regional variation (Steidinger et al. 2020). Furthermore, ECM fungal diversity across Japan was also demonstrated to significantly decrease with MAT (Miyamoto et al. 2018), suggesting potential decreases with warming. The observation of the ECM fungal community shift on Betula papyrifera and Abies balsamea saplings in a warming experiment (Fernandez et al. 2017) suggests that warming may change the future composition of the ECM fungal subcommunity.

Since N supply to plants is one of the major roles of ECM fungi, N deposition likely affects ECM fungal communities. With increasing nitrogen availability, fungi that obtain nitrogen from complex soil organic sources using metabolically costly pathways – e.g., Cortinarius, Piloderma and Tricholoma – are likely at a disadvantage compared to fungi that use inorganic nitrogen, such as Elaphomyces or Laccaria (Lilleskov et al. 2011). In a large survey of ECM fungi associated with forest trees in Europe, several ECM fungi responded to N throughfall deposition. Fungi that use organic nitrogen tended to be negative indicators for nitrogen deposition, while fungi that use inorganic nitrogen tended to be positive indicators. Conifer specialists – particularly those with abundant hyphae and rhizomorphs – were more negatively affected by increasing nitrogen than generalists and broad-leaf specialists (van der Linde et al. 2018). In the future, N deposition will likely affect ECM fungi and promote shifts from nitrophobic species (e.g., Russula vinosa, Lactarius rufus) to nitrophilic species (e.g., Scleroderma citrinum, Amanita rubescens, Russula ochroleuca) (Fig. 1; van der Linde et al. 2018).

In theory, mutualistic fungi could accompany host plants in climate-induced migration (Rudgers et al. 2020). In a study of the upward migration of tree individuals above the tree line, low ECM diversity was observed in the roots of migrating trees indicating that the altitudinal shift in the ECM fungal community lags behind climate-driven tree migration. ECM fungal dispersal limitation is thus an important factor controlling this process and possibly retarding vegetation shifts (Alvarez-Garrido et al. 2019). Similar conclusions were found in a study of invasive pines that clearly showed plant invasions can be limited by the dispersal of ECM fungi (Nunez et al. 2009).

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Similar to ECM fungi, AM fungi also fully depend on their symbiotic host plants as a sole source of carbon (Tisserant et al. 2013) and therefore any environmental shifts may affect abundance, species richness and AM fungal community composition directly as well as indirectly by altering their host plants. A recent review of the response of AM fungal species richness and community composition to various aspects of global change found that elevated CO2 will likely have no effect on AM fungal richness, and responses to N deposition, warming, and changed precipitation will likely be highly context dependent (Cotton 2018).

The effects of the above-mentioned extrinsic factors associated with global change are translated into community composition of AM fungi via differential responses of each species, which are determined by their intrinsic characteristics, such as specific growth patterns, morphology or anatomy. AM fungi greatly vary in root colonisation traits such as extent and structure (Klironomos & Hart 2002), and soil hyphal traits such as extent, density and structure (Powell et al. 2009). Interestingly, the increase of CO2 concentration, as well as increases in N availability, leads to lower relative abundance of AM fungal taxa from the Gigasporaceae and Diversisporaceae families, which produce high levels of extraradical mycelia, while relative abundance of the Glomeraceae taxa, which are characterised by extensive intraradical colonisation, tend to increase (Cotton 2018). This shift in community traits suggests lower investments in potentially costly nutrient acquisition traits with increasing nutrient availability.

The community level responses to environmental conditions combined with various intrinsic characteristics indicate that niche optima and niche width may differ among the species of AM fungi. Large sampling campaigns, enabled by an onset of high-throughput sequencing methods, provide sufficient data to model parameters of species ecological niches. While Acaulosporaceae has a realised niche optima in low temperature conditions, Gigasporaceae has a realised niche optima in high temperature and high precipitation conditions (Davison et al. 2021). Additionally, the width of the AM fungal temperature niche appears to be limiting, seeming to be narrower than in other fungal guilds (Větrovský et al. 2019, Davison et al. 2021). These findings indicate that changes of MAT and MAP can particularly affect the composition of AM fungal communities.

Contrary to diversity, the abundance of AM fungi seems to be more consistently affected by changes in N availability and shifts in CO2 concentration. While the majority of studies report a decrease in AM fungal abundance with enhanced nitrogen (e.g., Shen et al. 2014, Chen et al. 2017, Treseder et al. 2018, Zhang et al. 2018, Han et al. 2020, Jia et al. 2020a, Ma et al. 2021a), a few found no effect (Lilleskov et al. 2019, Karst et al. 2021). The addition of N can benefit AM fungi if it exacerbates plant P limitation (Johnson 2010), but may be suppressive if nitrophilic, ruderal plants replace plants that allocate more C to AM fungi (Isbell et al. 2013). Thus, the responses likely depend on the extent to which nutrient addition alleviates plant deficiencies and alters plant communities. A meta-analysis examining the global effects of nutrient enrichment on AM fungal and plant diversity showed that AM fungal diversity, rate of root colonisation, and extraradical biomass typically decreased with N addition, while spore abundance and hyphal length were unaffected. These results were consistent among forests, grasslands, and agro-ecosystems (Ma et al. 2021a).

The short-term fertilisation effect of elevated CO2 concentrations mostly stimulated AMF abundance (e.g., Treseder 2004, Antoninka et al. 2011, Zavalloni et al. 2012, Sun et al. 2017, Dong et al. 2018). Importantly, while stimulation of AM fungal abundance with increased CO2 is expected, considering that plant productivity depends on nutrient supply by AM fungi, the increase of temperature and shifts in precipitation will likely affect AM fungal abundance thanks to a greater climate niche partitioning of AM fungi.

Plant pathogens

Analyses of fungal guild niche breadth indicates that plant pathogens may better cope with climate change than other fungal guilds (Chaloner et al. 2020). Conditions that affect pathogen overwintering and dispersal are of essential importance due to pathogen lifestyles, survival in soils, and outbreaks triggered by climatic and plant host signals. Global warming in areas with seasonal temperature variation has increased pathogen survival during winters and increased the length of vegetation seasons leading to faster pathogen spread or stronger outbreaks (Harvell et al. 2002). As an ongoing consequence of warming, movement of crop pests to higher latitudes has already been observed. Since the 1960s, fungal crop pests were observed to move polewards at a pace of some 5 km/y, more rapidly than most other crop pests (Bebber et al. 2013).

Warming appears to be the most important driver of plant pathogen abundance. Climatic factors, especially the MAT and precipitation seasonality were the most important predictors of the relative abundance of plant pathogens across 235 global sites. Under future climate change and land-use scenarios, relative abundance of plant pathogens is predicted to increase (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2020a). A nine-year warming experiment in a dryland on the Iberian peninsula showed higher relative share of pathogens, higher relative abundance of Alternaria and higher absolute abundance of Alternaria in warmed plots (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2020a). While the increase in relative abundance, or sporulation, of plant pathogens may increase the risk of a disease outbreak, direct causal links may be difficult to find. It is possible that negative responses of mycorrhizal fungi and neutral or positive responses of pathogens to climate change can subsequently manifest in negative responses of vegetation. More importantly, climatic events seem to be predictive factors of fungal disease outbreaks with high humidity and high temperature being the most common factors (Romero et al. 2022). Pathogens may also use the opportunity to attack weakened host communities such as forest ecosystems after dieback caused by drought or heat stress (Fig. 1; Anderegg et al. 2013).

In natural systems, pathogens appear to be more abundant in resource-rich environments (Reynolds et al. 2003, Revillini et al. 2016), and nutrient addition (e.g. fertilisation) has been linked to increased disease incidence in plants (Walters & Bingham 2007, Veresoglou et al. 2013) which may increase the risk of pathogen spread or outbreaks at elevated atmospheric N deposition. The effect of CO2 increase on pathogens is less clear, however, concentrations of spores of several pathogens were increased by elevated atmospheric CO2 (eCO2) in a Populus tremuloides plantation in air and litter. Although the responses of fungi were not uniform, significant increases were found in the potential pathogenic genera Alternaria, Cladosporium and Fusarium (Klironomos et al. 1997).

Plant pathogen community composition may not intrinsically affect ecosystems because it is often individual taxa that cause disease outbreaks. The effects of global change on individual plant pathogen taxa may thus be more important than the guild-level effects. Based on historical observations of higher Alternaria spp. spore concentrations at warm temperatures, spore concentrations are predicted to increase with warming in the United Kingdom (Maya-Manzano et al. 2016) and future climate models suggest increased prevalence of Alternaria brassicae in North Germany (Siebold & Tiedemann 2012). In several instances, eCO2 increased spore production by Alternaria spp. several-fold (Klironomos et al. 1997, Wolf et al. 2010). Considering disease severity, both warming and eCO2 has been shown to increase Alternaria leaf spot severity on rocket, cauliflower and cabbage (Pugliese et al. 2012, Siciliano et al. 2017).

To conclude, while differential response of ECM fungal species to global changes such as N deposition can be predicted from their extracellular enzymatic capabilities related to organic nitrogen accessibility, response of AM fungi depends on their differential colonisation traits. Species traits of saprotrophs or pathogens related to their response to global changes are much less clear and therefore predictions of global change effects on these two guilds are much more difficult.

Fungal response to global change factors and lessons learned from manipulated studies

Our present understanding of the response of fungi to global change is based on several lines of support: (1) ecological theory and the predictions based on the known niches of fungal species, (2) predictions of responses to indirect factors affected by global change, such as the change of soil chemistry, vegetation composition, or ecosystem productivity, (3) extrapolation of observations of changes in fungal communities across time and space, (4) experimental simulation of future conditions and the analysis of fungal response. Since there is a lack of long-term observations on soil fungi under conditions of real-time climate change and the extrapolation of such observations may be problematic, experimental manipulations simulating global change factors appear to be the best tool to predict the future of soil fungi.

Experimental approaches have several limitations that must be considered when interpreting results. Each of the experiments has at least three important aspects that affect the observations: (1) the duration of treatment, (2) the intensity of manipulation, and (3) the local conditions. Over the duration of treatment, several components of the system respond so that direct, and/or indirect, effects change in time and adaptations emerge. The plant communities likely respond first with altered productivity, while change in composition comes later (Smith et al. 2009). Importantly, the effects of short-term warming and/or precipitation experiments can be eclipsed by site specific year-to-year variation in climatic conditions. The intensity of manipulation is another critical issue. In many experiments, especially those simulating N deposition, the magnitude of treatments is considerably larger than those predicted by current models. Equally important, the target biome and local condition at the experimental sites can interact with the global change treatments. Moreover, soil fungi as the responding community are extremely diverse in terms of alpha and beta diversity (Baldrian et al. 2021) which limits the cross-ecosystem interpretation of community effects. Unfortunately, the experimental results reported so far show high levels of geographic bias with most studies in forests and grasslands of the temperate zone (Tables 2–5). These biases in sampling mean that surprising results from underexplored biomes, such as massive CO2 fluxes from warmed plots recorded in the Panama tropical rainforest, cannot be ignored. Such fluxes largely exceeded model predictions and indicated high sensitivity of local soil C stocks to warming (Nottingham et al. 2020).

Table 2.

Effects of experimental CO2 enrichment on fungi. Manipulations of at least 1 y duration where CO2 enrichment was not combined with other factors were considered.

| Location | Experimental system | Duration of treatment (yr) | CO2 concentration applied (ppm) | Biomass | Diversity | Guilds share | Community composition | Reference1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All fungi | ||||||||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 2 | 500 | + | change | Liu et al. (2014) | ||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 3 | 500 | + | 0 | change | Liu et al. (2017) | |

| North America (USA) | experimental grassland | 3 | 500 | 0 / + | change (more AMF) | change | Procter et al. (2014) | |

| Asia (China) | shrubland | 4 | 700 | 0 | change | Jia et al. (2020b) | ||

| Europe (Denmark) | shrubland | 5 | 510 | 0 | Haugwitz et al. (2014) | |||

| Australia (Australia) | grassland | 5 | 550 | + | change | Hayden et al. (2012) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 6 | 680 | 0 | Gutknecht et al. (2012) | |||

| Europe (Italy) | forest plantation | 6 | 550 | 0 | change | Lagomarsino et al. (2007) | ||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 8 | 500 | + | Liu et al. (2021a) | |||

| North America (USA) | shrubland | 8 | 550 | + | + | change | Lipson et al. (2014) | |

| Europe (Switzerland) | experimental forest | 9 | 570 | 0 | no change | change | Solly et al. (2017) | |

| Europe (Germany) | grassland | 10 | 440 | 0 | Guenet et al. (2012) | |||

| North America (USA) | forest plantation | 11 | 560 | 0 | 0 | no change | Dunbar et al. (2014) | |

| North America (USA) | experimental field | 12 | 550 | + | change (more Basidiomycota, less Ascomycota) | Tu et al. (2015) | ||

| North America (USA) | forest plantation | 14 | 571 | change | Weber et al. (2013) | |||

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi | ||||||||

| North America (USA) | experimental field | 2; 4; 6 | 550 | 0 | change (more Glomeraceae and Gigasporaceae) | Cotton et al. (2015) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 3 | 680 | 0 | no change | Mueller & Bohannan (2015) | ||

| North America (USA) | shrubland | 3.4–3.9 | up to 750 | + | change (more Acaulospora and Scutellospora) | Treseder et al. (2003) | ||

| Europe (Switzerland) | experimental field | 7 | 600 | + (root colonisation) | Gamper et al. (2004) | |||

| North America (USA) | orchard | 7 | 670 | 0 | 0 | Kimball et al. (2007) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 7 | 580 | 0 | - | no change | Zheng et al. (2022a) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 7 | 560 | + (soil hyphae) | Antoninka et al. (2011) | |||

| Asia (India) | experimental field | 8 | 550 | + | 0 | change | Panneerselvam et al. (2020) | |

| Europe (Germany) | grassland | 15 | 440 | 0 (root colonisation) | + | no change | Maček et al. (2019) | |

Table 5.

Effects of experimental N addition on fungi. Manipulations where N was added in a mineral form with the aim to simulate atmospheric deposition that lasted at least for 1 yr and where N addition was not combined with other factors were considered. Manipulations or treatments where N addition exceeded 75 kg N/ha/y were not considered as highly exceeding projected N deposition increase; + denotes that the experiment also included treatment(s) with higher N addition level(s).

| Location | Experimental system | Duration of treatment (yr) | N addition (kg N/ha/y) | Biomass | Diversity | Guilds share | Community composition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All fungi | ||||||||

| North America (USA) | shrubland | 1 | 7; 15 | 0 | no change | Mueller et al. (2015) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1 | 50; + | 0 | change | Li et al. (2020a) | ||

| North America (USA) | experimental field | 1 | 50 | 0 | no change | no change | Anthony et al. (2020) | |

| North America (Canada) | grassland | 1–2 | 20 | + | Bell et al. (2010) | |||

| Asia (China) | shrubland | 2 | 60 | 0 | change | She et al. (2018) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 2 | 30; 60; + | + | + | change (more AMF) | change (more Basidiomycota) | Li et al. (2019a) |

| Asia (China) | wetland | 2 | 30; 60; + | 0 | change | Li et al. (2020b) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 2 | 25 | + | change | Guo et al. (2021) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 15; 30; 50; + | 0 | Zhang et al. (2018) | |||

| Europe (Czech Republic) | forest | 4 | 50 | 0 | no change | Choma et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 5 | 35 | 0 | change (less AMF) | change | Wang et al. (2020b) | |

| Asia (China) | forest | 5 | 25 | + | + | change (more saprotrophs) | change | Zhao et al. (2020) |

| Asia (China) | forest | 6 | 50; + | - | 0 | change (less Ascomycota) | Wang et al. (2021b) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 6 | 70 | change (less AMF) | Gutknecht et al. (2012) | |||

| Asia (China) | forest | 6 | 50; + | 0 | no change | Li et al. (2019b) | ||

| Asia (China) | experimental field | 7 | 35; 70; + | + | - | change | Wang et al. (2015) | |

| North America (USA) | experimental grassland | 7 | 28; 56; + | 0 | change (less AMF) | change | Li et al. (2021) | |

| Asia (China) | forest | 8 | 50 | 0 | Yan et al. (2021) | |||

| North America (Canada) | forest | 10 | 30 | 0 | no change | no change | Wu et al. (2021) | |

| North America (Canada) | experimental field | 10 | 30; + | 0 | - | change | Tosi et al. (2021) | |

| Europe (United Kingdom) | wetland | 14 | 8; 25; 56 | change (less ERM) | Vesala et al. (2021) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 15 | 18; 53; + | - | 0 | change (more Eurotiomycetes and Sordariomycetes) | Chen et al. (2019) | |

| North America (USA) | forest | 16 | 30 | 0 | no change | Hesse et al. (2015) | ||

| North America (USA) | forest | 20 | 30 | 0 | 0 | no change | Freedman et al. (2015) | |

| North America (USA) | forest | 20 | 50; + | change (less ECM, more saprotrophs) | change (more nitrophilic ECM) | Morrison et al. (2016) | ||

| Europe (Switzerland) | forest | 20 | 22 | 0 | 0 | change (less ECM) | change | Frey et al. (2020) |

| Europe (Sweden) | forest | 23; 46 | 34; 73 | 0 | change (less ECM) | Choma et al. (2017) | ||

| Europe (Sweden) | forest | 24 | 40 | + | 0 | change (more saprotrophs) | change (more nitrophilic ECM) | Tahovská et al. (2020) |

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi | ||||||||

| North America (USA) | experimental field | 1 | 50 | 0 | no change | Anthony et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 2 | 30; 60 | + (root colonisation) | + | change | Liu et al. (2021c) | |

| North America (USA) | shrubland | 2.8 | 60 | - (spore density) | - | change (more Glomus, less Gigaspora and Scutellospora) | Egerton-Warburton & Allen (2000) | |

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 3 | 40; + | + (root colonisation) | 0 | change (more Gigasporaceae) | Cao et al. (2020b) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 50; + | - (root colonisation) | + | change | Jiang et al. (2018) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 3 | 70 | 0 | no change | Mueller & Bohannan (2015) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 4 | 50 | 0 | no change | Zhao et al. (2018) | ||

| Asia (China) | experimental field | 5 | 50; + | - | - | change | Zhu et al. (2018) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 6 | 15; 75 | - (spore density) | + | no change | Zheng et al. (2014) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 6 | 70 | - (biomass) | Gutknecht et al. (2012) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 7 | 50; + | - (root colonisation) | 0 | change | Lu et al. (2020) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 7 | 50; + | - (root colonisation, biomass) | - | change | Chen et al. (2017) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 8 | 25; 50 | 0 | 0 | no change | Li et al. (2015) | |

| North America (USA) | forest | 12 | 30 | change (more Glomus) | van Diepen et al. (2011) | |||

| North America (USA) | forest | 16 | 30 | 0 | no change | van Diepen et al. (2013) | ||

Here, we review the results from experimental simulations of climate change factors 1) elevated CO2, 2) warming, 3) reduction of precipitation, and 4) increased N deposition (Fig. 1). We ended up with 138 studies that applied realistic treatment types and levels (see each section) and reported at least one of the below response variables (Supp. S1). Though our survey is not exhaustive, we believe it is representative of the current state of knowledge. We decided to focus on the commonly studied fungal responses biomass, diversity, guild share, and changes in community composition. Though these responses are interconnected (e.g., changes in fungal diversity will likely lead to changes in composition), we decided to survey all factors to highlight the current focuses of research into the responses of fungi to climate change factors. The analyses of diversity, guild share, and changes in community composition largely rely on meta-barcoding sequencing, which we recognise as suffering from biases such as primer bias and the use of relative abundances (Quinn et al. 2018, Alteio et al. 2021), it is still the best tool for understanding fungal communities (Nilsson et al. 2018). All recorded responses are taken directly from the results sections and therefore represent current interests in the field.

Increase of CO2 concentration

Elevated CO2 partially underlies global increases in plant productivity (Nemani et al. 2003). Furthermore, experimentally elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations (eCO2) have led to short term increases in plant biomass production, allocation of carbon to roots and to soil (Adair et al. 2011) and consequently soil respiration. The higher C allocation belowground can fuel the breakdown of labile organic matter by copiotrophic microorganisms. Therefore, microbial biomass and heterotrophic respiration will likely increase (Fig. 1; Naylor et al. 2020). At longer time scales, eCO2 has been shown to increase microbial decomposition of soil organic matter (SOM) through priming (van Groenigen et al. 2014). Direct effects on individual fungi are unlikely since CO2 concentration in soil pores is higher than in the atmosphere and varies in space and time.

Furthermore, eCO2 may affect fungal propagation and dispersal. Under an 2×-ambient CO2 treatment in a Populus tremuloides plantation, the concentration of airborne fungal propagules, mostly spores, increased fourfold. Analysis of decomposing leaf litter (likely the main source of airborne fungal propagules) indicated that fungi produced fivefold more spores (Klironomos et al. 1997). Furthermore, increased total sporocarp biomass was observed in an eCO2 experiment (Andrew & Lilleskov 2009). Since fruiting and sporulation is the main mode of dispersal of soil fungi, consequences of this observation – if confirmed in additional systems – may be important.

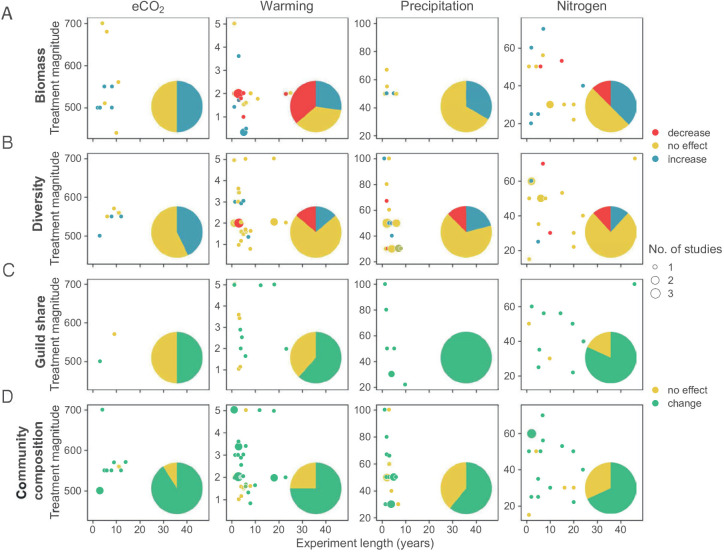

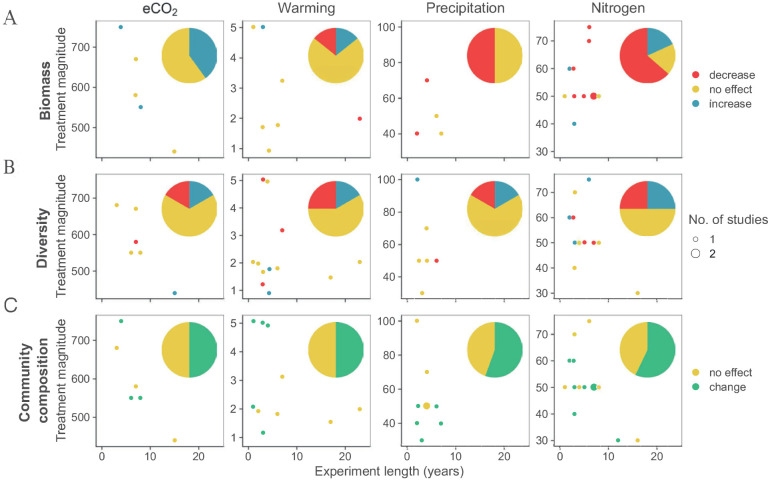

Across the studies we surveyed, eCO2 experiments report either no change or increased biomass and diversity of all fungi, and only single cases of reduced AM fungal diversity and change in guild composition. Most experiments report change in the fungal community composition but there were no consistent observations of enriched or suppressed taxa (Fig. 3, Table 2). Though we found no clear relationship between fungal responsiveness and experimental length (Figs 3, 4), a meta-analysis of 11 studies found a positive relationship between increased fungal richness due to eCO2 and experimental length (Veresoglou et al. 2016). A recent global meta-analysis found no relationship between experimental length and the responsiveness of fungal biomass, but found that eCO2 decreased the F/B ratio across 31 studies (Sun et al. 2021). In our survey, the longest experiments showed contrasting effects on soil chemistry. A forest-based experiment reported significant decreases in pH, organic matter content, and P and increased water content (Weber et al. 2013) which may all potentially affect fungi. However, a grassland experiment of a similar length reported no significant change in soil chemistry (Maček et al. 2019).

Fig. 3.

Observations of the effects of selected global change factors on the A) biomass, B) diversity, C) guild composition and D) community composition of total fungi in the context of experimental length and magnitude of treatment. The pie graphs indicate the total share of experiments reporting statistically significant effects (increase, decrease, no change). Treatment intensities are in ppm applied for CO2, increase in °C in temperature manipulation, percent reduction in precipitation and kg/ha/y in N addition. For the lists of experiments, see Tables 1–4.

Fig. 4.

Observations of the effects of selected global change factors on the A) biomass, B) diversity and C) community composition of AM fungi in the context of experimental length and magnitude of treatment. The pie graphs indicate the total share of experiments reporting statistically significant effects (increase, decrease, no change). Treatment intensities are in ppm applied for CO2, increase in °C in temperature manipulation, percent reduction in precipitation and kg/ha/y in N addition. For the lists of experiments, see Tables 1–4.

Warming

In agreement with the increasing catalytic performance of soil enzymes with increasing temperature (Baldrian et al. 2013), C turnover across global biomes has been shown to increase with temperature (Carvalhais et al. 2014). Temperature sensitivity of soil C loss appears higher in cold regions (Crowther et al. 2016, Koven et al. 2017) and probably the most extreme response is expected in the permafrost where thawing dramatically increases organic matter transformation and the emissions of CO2 and CH4 (Jansson & Tas 2014). The expected C losses are large since the soils in cold regions host large C stocks (Crowther et al. 2019, García-Palacios et al. 2021). Additionally, warming has led to the loss of plant species unable to tolerate new environmental conditions (Freeman et al. 2018) or outcompeted by invaders better adapted to the new conditions (Alexander et al. 2015). These shifts in plant species composition may alter the quality of the carbon input into the system (Harte et al. 2015). Shifts in fungal saprotroph communities in response to both increased access to extant carbon and novel carbon inputs will have important implications for global responses to climate change (García-Palacios et al. 2021).

The responses of soil fungal communities to warming likely depends on the local climatic conditions, such as MAT. Not surprisingly, in the Antarctic, at the lower limit of fungal temperature tolerance, air temperature is the strongest and most consistent predictor of soil fungal diversity and, with current rates of warming, a 30 % increase in fungal diversity is predicted by 2100 (Newsham et al. 2016). However, this diversity response to warming is probably not universal since the highest level of fungal diversity is predicted in cold areas (Větrovský et al. 2019). Similar to soil fungi, the highest diversity of bacteria in global surveys has also been observed at locations with relatively low MAT (around 10 °C; Thompson et al. 2017) and temperate regions (Bahram et al. 2018), although bacterial biomass in soils does not seem to be affected by warming (Lladó et al. 2017).

Short-term and prolonged warming may have differing effects. An initial loss of labile soil carbon in one of the longest running warming experiments in the Harvard Forest was later followed by increased degradation of more recalcitrant carbon compounds. Sustained warming for 26 years resulted in the depletion of soil organic carbon (SOC) with corresponding reductions in microbial biomass (Melillo et al. 2017). Based on a meta-analysis, warming initially increases soil respiration, but the magnitude of observed effect declines significantly as warming progresses and in fact, after 10 years of warming, soil respiration in experimentally warmed plots was similar to controls. Microbial acclimation, community shifts, adaptation, or reductions in labile C may ameliorate warming effects on soil respiration in the long-term. Accordingly, long-term soil C losses might be smaller than those suggested by short-term warming studies. The share of experiments where fungal biomass increased versus decreased with warming have been found to be roughly equivalent and no significant change in the fungal to bacterial (F/B) biomass ratio were observed across studies (Romero-Olivares et al. 2017). The F/B ratio was also unaffected after 7–25 yr of warming across 12 experiments in the Alpine and Arctic tundra (Jeanbille et al. 2021).

Temperature also alters fungal fruiting with consequences for dispersal. Across Europe, timing of fruiting has been shown to vary by 25 d among latitudes and 30 d among altitudes suggesting a strong temperature effect (Andrew et al. 2018). Present-day autumn fruiting of fungi has been shown to occur later than in the past, and the fruiting season length has increased, similar to the vegetation season (Kauserud et al. 2012). There has also been shown to be a significant shift in fruiting of saprotrophic and ectomycorrhizal fungi towards higher altitudes in the Swiss Alps between 1960 and 2010 as a consequence of warming (Diez et al. 2020).

Warming was the most frequently applied treatment in our survey (47 % of studies) and as such gives the best opportunity for generalisations. Importantly, warming was most frequently reported to alter total fungal biomass and a substantial fraction of the observations indicate negative effects, especially between 3–5 yr of application. In longer-lasting experiments, however, the effects on fungal biomass were less pronounced and AM fungi seem to be even less affected. Both negative and positive effects on total fungal diversity were reported but no effects were reported for experiments running for more than three years; furthermore, the decrease of AM fungal diversity was also observed only in the short term (Figs 3, 4, Table 3). Many individual experiments reported significant effects on fungal guild composition, which were, however, context-dependent. The only exception is the effect on plant pathogens where all reports showed their increase (Table 3). Most warming experiments also reported change in fungal community composition, often within the ectomycorrhizal guild (Fernandez et al. 2017, van Nuland et al. 2020) and a decrease of the Glomeraceae was recorded within the AM fungi (Cao et al. 2020a, b). Interestingly, almost all studies with experimental lengths longer than 10 yr or any experimental length with warming treatments larger than 2 °C reported significant changes in fungal community composition. In partial support of our survey, a recent global meta-analysis found that warming decreased fungal richness but that there was no significant effect of experimental length on this response (Li et al. 2022). There were no reports of important changes in soil nutrient content or pH but some of the long-term experiments report the decrease of the F/B biomass ratio (Gutknecht et al. 2012) and lower transcription of hydrolytic enzymes (Romero-Olivares et al. 2019), two factors that may be connected since fungi are important producers of enzymes in soils (Starke et al. 2021).

Table 3.

Effects of experimental warming on fungi. Manipulations of at least 1 yr duration where warming was not combined with other factors were considered.

| Location | Experimental system | Duration of treatment (yr) | Temperature increase (°C) | Biomass | Diversity | Guilds share | Community composition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All fungi | ||||||||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | no change | Zhang et al. (2016a) | ||

| North America (USA) | forest | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | change (more plant pathogens, less AMF) | change | Garcia et al. (2020) | |

| North America (USA) | experimental field | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | no change | change | Anthony et al. (2020) | |

| South America (Brazil) | experimental field | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | change (more Hypocreales, less Pleosporales) | de Oliveira et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 1.2 | 1.4 | + | Liu et al. (2021b) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1.3 | 1.0; 2.0 | 0 | change | Xiong et al. (2014) | ||

| Asia (South Korea) | forest plantation | 1.5 | 3.0 | + | change | Li et al. (2017) | ||

| North America (Canada) | grassland | 1–2 | 2.0 | 0 | Bell et al. (2010) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1; 2; 4 | 1.6 | 0 | no change | Shi et al. (2020) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 1–5 | 3.0 | + | change | Guo et al. (2019) | ||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 2 | 2.0 | variable | - | change | Liu et al. (2014) | |

| Asia (South Korea) | forest plantation | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0 | change | Li et al. (2018) | ||

| Asia (China) | experimental grassland | 3 | 1.5; 2.0 | - / 0 | change | Zhang et al. (2016b) | ||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 3 | 2.0 | - | - | change | Liu et al. (2017) | |

| Asia (China) | experimental grassland | 3 | 1.5; 2.0 | - / 0 | change | Zhang et al. (2017) | ||

| North America (USA) | forest | 3 | 1.7; 3.4 | no change | change (within ECM community) | Mucha et al. (2018) | ||

| North America (USA) | forest plantation | 3 | 1.7; 3.4 | 0 | change (within ECM community) | van Nuland et al. (2020) | ||

| North America (USA) | desert | 3 | 2.0 | - | Zelikova et al. (2012) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 1.7 | + | Ding et al. (2020) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 1.5; 2.0 | no change | Zhang et al. (2019) | |||

| Asia (Japan) | grassland | 3 | 2.0 | - | Yoshitake et al. (2015) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 1.8 | - | Ma et al. (2011) | |||

| Europe (Switzerland) | forest plantation | 3 | 3.6 | + | 0 | no change | change | Solly et al. (2017) |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 3 | 1.0 | 0 | no change | no change | Jumpponen & Jones (2014) | |

| Australia (Australia) | shrubland | 4 | 2.9 | 0 / + | change (more plant pathogens) | change | Birnbaum et al. (2019) | |

| Europe (Spain) | shrubland | 4 | 2.5 | change (less ECM) | change (within ECM community) | León-Sánchez et al. (2018) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 4 | 1.8 | - | Li et al. (2013) | |||

| Europe (Norway) | tundra | 4 | 0.6–1.1 | 0 | no change | no change | Ahonen et al. (2021) | |

| Europe (Spain) | shrubland | 4 | 2 | 0 | change (less ECM) | no change | Querejeta et al. (2021) | |

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 5 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | no change | Wang et al. (2019) | |

| Europe (Denmark) | shrubland | 5 | 0.3 | + | Haugwitz et al. (2014) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 5 | 1.0 | - | Shao et al. (2018) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 5 | 0.3 | + | Wang et al. (2017) | |||

| Australia (Australia) | grassland | 5 | 2.0 | - | change | Hayden et al. (2012) | ||

| North America (USA) | forest | 6 | 3.4 | change (within ECM community) | Fernandez et al. (2017) | |||

| Europe (Norway) | shrubland | 6 | 1.7 | 0 | no change | Lorberau et al. (2017) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 6 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | change (less AMF) | change (more Dothideomycetes) | Che et al. (2019) |

| North America (USA) | woodland | 6 | 5.0 | 0 | no change | Gehring et al. (2020) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 6 | 1.0 | change (less AMF) | Gutknecht et al. (2012) | |||

| Asia (China) | shrubland | 6 | 0.5 | + | Song et al. (2021) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 7 | 1.3 | 0 / + | change | Yu et al. (2019) | ||

| Many (Many) | 7–25 | 0.5–2.0 | 0 | Jeanbille et al. (2021) | ||||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 8 | 2.0 | 0 | Liu et al. (2021a) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 8 | 1.6 | 0 | no change | Peng et al. (2020) | ||

| Antarctica (Antarctica) | desert | 8 | 0.8 | + | 0 | change | Kim et al. (2018) | |

| North America (USA) | forest | 10 | 1.6 | change | Romero-Olivares et al. (2019) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 11 | 1.8 | 0 | Zhang et al. (2015) | |||

| North America (USA) | forest | 12 | 5.0 | - | change (less AMF) | change | Frey et al. (2008) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 18 | 1.5–2.0 | 0 | change | Geml et al. (2015) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 18 | 1.0–5.0 | 0 | change (more plant pathogens and saprotrophs) | change (within Ascomycota) | Semenova et al. (2015) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 18 | 1.5–2.0 | 0 | change | Geml et al. (2021) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 23 | 2.0 | 0 / - | 0 | change (more AMF) | change | Kazenel et al. (2019) |

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi | ||||||||

| North America (USA) | experimental field | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | change | Anthony et al. (2020) | ||

| Europe (Germany) | cropland | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | change | Wahdan et al. (2021) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 2 | 2.0 | 0 | no change | Wei et al. (2021) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 0.5–1.2 | - | change | Shi et al. (2017) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 3 | 5.0 | + (root colonisation) | - | change (less Glomeraceae) | Cao et al. (2020b) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 1.2–1.7 | 0 | 0 | Yang (2013) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 4 | 5.0 | 0 | change (more Gigasporaceae, less Glomeraceae) | Cao et al. (2020a) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 4.3 | 1.8 | + | Kim et al. (2015) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0 (soil hyphal density) | + | Kim et al. (2014) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 6 | 1.8 | 0 (soil hyphal and spore density) | 0 | no change | Gao et al. (2016) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 7 | 1.5–3.2 | 0 | - | no change | Zheng et al. (2022a) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 17 | 1.5 | 0 | no change | Shi et al. (2021) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 23 | 2.0 | 0 / - | 0 | no change | Kazenel et al. (2019) | |

Reduction of precipitation

Since soil C turnover across global biomes increases with precipitation (Carvalhais et al. 2014), any change in precipitation likely affects C cycling. Responses of plant communities to increased variability in precipitation have ranged from high ecosystem stability in the face of intra-annual variability (Jones et al. 2016) to increasing functional diversity with increased inter-annual variability (Gherardi & Sala 2015). Even when there is very little recorded change in plant community diversity, significant changes in species composition through reordering have been recorded (Jones et al. 2017). While climate models predict both decreases and increases in precipitation across global locations (IPCC 2014), drought effects on ecosystems are likely much more dramatic. Increases in the durations of drought are expected to be a major consequence of future climate and increased desertification is predicted for most semi-arid or arid regions in the coming decades (Huang et al. 2016). Based on a recent meta-analysis, terrestrial ecosystem productivity was decreased by drought across all ecosystems (Wang et al. 2021a). The response of productivity to drought are more pronounced with higher drought intensity and longer duration, and consistent across biomes and climates. Drought can significantly decrease soil moisture, soil C content, soil C:N ratios, and microbial biomass C, whereas it tends to increase soil pH. The relative proportion of fungal biomass (F/B ratio) however, frequently increases with drought (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2020b, Wang et al. 2021a). The diversity and abundance of soil bacteria and fungi have been shown to decrease in drylands as aridity increased, being largely driven by the negative impacts of aridity on soil organic carbon content (Maestre et al. 2015).

Since most global change models predict changes in precipitation, experimental manipulations of precipitation are relatively frequent. Unfortunately, such manipulations are highly diverse and range from reduction and addition to redistribution. Both reduction and addition are frequently combined often without a clear link to a model prediction for the ecosystem under study (Knapp et al. 2015). Moreover, many experiments use manipulations that are likely outside the model predictions with reductions or additions > 50 % and the relevance of such manipulations is thus unclear. For simplicity, we surveyed the effects of precipitation reduction since drought seemed to have more profound ecosystem consequences (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of experimental reduction of precipitation on fungi. Manipulations of at least 1 y duration where reduction of precipitation was not combined with other factors were considered.

| Location | Experimental system | Duration of treatment (yr) | Reduction of precipitation (%) | Biomass | Diversity | Guilds share | Community composition | Reference1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All fungi | ||||||||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 1 | 100 | 0 | change | McHugh & Schwartz (2015) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1 | 50 | 0 | no change | Zhang et al. (2016a) | ||

| North America (Brazil) | experimental field | 1 | 100 | + | change (more selected plant pathogens) | no change | de Oliveira et al. (2020) | |

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 1.2 | 50 | 0 | Liu et al. (2021b) | |||

| Asia (Korea) | forest plantation | 1.5 | 30 | 0 | change | Li et al. (2017) | ||

| North America/Australia (USA/Australia) | grassland | 1–2 | 50 | 0 / + | variable | change (less AMF) | change | Ochoa-Hueso et al. (2018) |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1–2 | 30; 50 | 0 | no change | Yang et al. (2021b) | ||

| Asia (China) | cropland | 1–2 | 30; 50 | 0 | no change | Sun et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1–2 | 20; 40; 60 | change | Zhao et al. (2016) | |||

| Australia (Australia) | grassland | 1; 2; 3 | 50 | + | change | Ochoa-Hueso et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 1; 2; 4 | 50 | + | change | Shi et al. (2020) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 1–5 | 50 | - | change | Guo et al. (2019) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 2 | 67 | 0 | - | change (more Basidiomycota, less Ascomycota) | Zhao et al. (2017) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 2 | 40; 80 | 0 | change (more pathogens, less AMF) | change | Huang et al. (2021) | |

| Europe (Belgium) | forest plantation | 2 | 45–55 | 0 | Hicks et al. (2018) | |||

| Asia (South Korea ) | forest plantation | 2.7 | 30 | - | change | Li et al. (2018) | ||

| North America (USA) | grassland | 2–3 | 66 | change | Lagueux et al. (2021) | |||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 0–100 | 0 | no change | Wu et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 30; 60 | 0 | no change | Wang et al. (2020a) | ||

| Australia (Australia) | shrubland | 4 | 30 | 0 | change (more ECM and plant pathogens) | change | Birnbaum et al. (2019) | |

| Europe (Spain) | shrubland | 4 | 30 | 0 | change (less ECM) | change (within EMF community) | León-Sánchez et al. (2018) | |

| North America (USA) | grassland | 4 | 40 | 0/+ | no change | Narayanan et al. (2021) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 5 | 50 | 0 | change (more plant pathogens) | change | Wang et al. (2020b) | |

| Europe (Denmark) | shrubland | 5 | 50 | + | Haugwitz et al. (2014) | |||

| North America (USA) | woodland | 6 | 50 | 0 | 0 | no change | Gehring et al. (2020) | |

| Asia (China) | grassland | 6 | 50 | 0 | change | Xiao et al. (2020) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 7 | 30 | 0 | no change | Zhang et al. (2021) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 7 | 30 | 0 | Jia et al. (2017) | |||

| Asia (China) | forest | 8 | 30 | + | Yan et al. (2021) | |||

| North America (USA) | forest | 10 | 22 | change | Romero-Olivares et al. (2019) | |||

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi | ||||||||

| Australia (Australia) | experimental grassland | 1; 2; 3; 4 | 50 | 0 | Deveautour et al. (2020) | |||

| Asia (China) | experimental field | 2 | 100 | + | 0 | Zhong et al. (2021) | ||

| North America (USA) | experimental grassland | 2 | 40 | - (root colonisation) | change | Emery et al. (2022) | ||

| Australia (Australia) | experimental grassland | 2.3 | 50 | 0 | change | Deveautour et al. (2018) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 3 | 30 | 0 | change | Wang et al. (2021c) | ||

| Asia (China) | forest | 4 | 70 | - (hyphal and spore density, root colonisation) | 0 | 0 | Maitra et al. (2019) | |

| Asia (China) | forest plantation | 4 | 50 | 0 | 0 | Cao et al. (2020a) | ||

| Asia (China) | grassland | 6 | 50 | 0 | - | change | Zheng et al. (2022b) | |

| North America (USA) | shrubland | 7 | 40 | 0 | change | Weber et al. (2019) | ||

In our survey, no negative effects of precipitation on total fungal biomass were reported with most experiments reporting no effect on any response variable (Fig. 3, Table 4). In studies of AMF, there was decreased hyphal, spore density, and root colonisation in a forest system in connection with soil acidification (Maitra et al. 2019) and a reduction in root colonisation in a perennial cropping system (Emery et al. 2022). Reduction of precipitation most frequently did not affect the diversity of fungi and AM fungi and decrease of total fungal diversity was never observed in manipulations lasting three or more years (Figs 3, 4, Table 4). Contrary to our survey, a recent global meta-analysis found that precipitation reduction led to increased fungal richness with the effect size increasing with experimental length, though precipitation reduction had no effect on fungal diversity (Li et al. 2022). Importantly, precipitation reduction typically shifted the share of fungal guilds with the reduction of AM fungi and increase of plant pathogens being frequently reported. Changes in fungal community composition were also relatively frequent (Table 4). Increase of the F/B ratio was observed in a heathland experiment (Haugwitz et al. 2014). Changes in soil chemistry were typically not found, not even for the long-lasting experiments.

Increased atmospheric N deposition

Many plant communities are N limited (LeBauer & Treseder 2008), and additional N can thus promote plant productivity if P content is non-limiting (Fay et al. 2015). Additionally, N deposition may reduce plant species richness though this effect depends on ecosystem characteristics, such as MAP (Clark et al. 2007). For example, N addition may increase plant species richness in ecosystems with high MAP (Komatsu et al. 2019). In addition to effects on vegetation, N has multiple effects on soil chemistry, including acidification (Lekberg et al. 2021). Though a recent global meta-analysis found that N reduced overall soil fungal richness (Zhou et al. 2020), the effects of N deposition on soil fungi can be, like plant community responses, context dependent. Across N-addition studies in the US forests, fungal biomass and richness increased with simulated N deposition at sites with low ambient deposition but decreased at sites with high ambient deposition (Moore et al. 2021). Along local fertility gradients, total fungal biomass was highest in soils with the lowest nutrient availability and tree productivity (Nilsson et al. 2005). Higher N availability promotes bacterial growth due to their higher N demand. Especially in the N-limited boreal soils, N addition results in a decrease of the F/B ratio by 25–70 % (Frey et al. 2004, Wallenstein et al. 2006, Maaroufi et al. 2015).

There appears to be a general consensus that N deposition increases soil C sequestration due to the decline in SOM decomposition via the reduction of fungal abundance and decomposer activity in many different soil environments, including temperate and boreal forests (Frey et al. 2014, Maaroufi et al. 2015). Since, similar to plants, many fungi respond to P availability in soil and it is an important driver of fungal abundance in soils without N limitations (Odriozola et al. 2021), increased N content may act on fungal productivity and community composition indirectly through P limitation (Fig. 1).

Within our survey, the goal of the majority of N addition experiments was to simulate predicted increases in atmospheric deposition, but many used unreasonably high amounts of fertilizer, ignored ambient N deposition rates, and virtually none of them referenced a model that predicts future deposition, whose extent shows high local variation. It is currently estimated that the vast majority of forests are subject to total N deposition lower than 25 kg N/ha/y (Schwede et al. 2018) and it is unrealistic to expect that the increase in future is several-fold. We have thus considered only the results of experiments where N addition was lower than 75 kg N/ha/y.

The effects of N addition on fungal biomass in soil were variable. For AM fungi, decreased spore density, root colonisation, and biomass were much more frequent than positive effects (Fig. 4). In forest ecosystems, decrease of fungal biomass and root colonisation appears typical (Ma et al. 2021b). Both increases and decreases in diversity of fungi or AM fungi were observed (Figs 3, 4, Table 5). This lack of consistency in diversity responses is somewhat supported by the effects of increased N on fungal richness varying between global meta-analyses with increased N either decreasing richness or having no effect (Zhou et al. 2020, Li et al. 2022). Changes in the representation of fungal guilds were a common consequence of N addition. In most long-term N addition experiments, the share of ECM fungi was significantly reduced (Table 5) with a shift to nitrophilic taxa such as Rusula vinacea (Morrison et al. 2016, Tahovská et al. 2020). The consequences of longer N enrichment (> 4 yr) were relatively complex and include acidification and increased N availability (Choma et al. 2017, Wang et al. 2021b), decreased F/B ratio (Gutknecht et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2015) and decreased activity of enzymes decomposing recalcitrant plant biopolymers lignin and cellulose (Freedman et al. 2015, Hesse et al. 2015). Although vegetation responds to N addition as well, the change of soil chemistry appeared to be the immediate driver of fungal community composition (Zheng et al. 2014, Zhou et al. 2020, Wang et al. 2021b).

Combined effects and model predictions

Current models predict that the effects of global change factors will act simultaneously in most terrestrial habitats and the resulting effect of global change thus reflects their combination. Furthermore, shifts in plant community composition are likely determined by interactions between multiple climate change drivers (Avolio et al. 2021). Between 1990 and 2014, global heterotrophic soil respiration and its ratio to total soil respiration increased, probably in response to the combined effects of global change factors (Bond-Lamberty et al. 2018). This suggests that climate-driven losses of soil carbon are currently occurring across many ecosystems, with a detectable and sustained trend emerging at the global scale, although the underlying mechanisms cannot be easily identified. Simulation of the global change effects until the year 2090 using available data from 1950 indicates that climate change acts mostly indirectly, through other environmental variables, e.g., changes in the soil pH (Guerra et al. 2021). The effects of global change factors on fungi thus may depend either on the relative importance of each individual factor under local conditions or on the combined effects of multiple factors.

CONCLUSIONS

While ongoing climate change has had seemingly no dramatic effects on soil fungal communities, and neither fungal biomass nor fungal diversity in soils appear to be dramatically affected, experiments simulating the main global change effects predict significant shifts in fungal community composition and the share of fungal guilds. The differences in the size of the realised niche of plant-beneficial ECM fungi compared to that of plant pathogens suggests that the fitness of vegetation may decrease as ecosystems experience increased spread of plant pathogens and potentially higher frequencies of outbreaks. This issue is perhaps the one that deserves most attention (Fig. 1). Interestingly, responses of soil fungi to various aspects of global change can be predicted based on different ecological features. While differential responses of ECM fungal species to global changes such as N deposition can be predicted from their extracellular enzymatic capabilities related to organic nitrogen accessibility, response of AM fungal species depends on their differential colonisation traits.

Global change effects on ecosystems are highly context dependent and there are undoubtedly ecosystems where changes will be more pronounced. Where global change relieves existing limitations, such as the coldest or N-limited areas, novel limitations will arise, such as increased desertification or induced P-limitation, respectively. Unfortunately, these systems are rarely the subject of research. Experimental manipulations in underexplored systems are thus most welcome.

Although the experiments combining multiple factors are relatively frequent (Yang et al. 2021a), they are in most cases applying unrealistic treatment intensities and so far too rare to allow generalisations. Since global change factors act in combination and their effects are not simply additive (Rillig et al. 2019), it would be more than welcome to see results of long-term manipulations based on complex predictions of multiple global change factors for given localities. Since it will never be possible to perform manipulations everywhere, long term collection of observational data is needed that would help to describe trends in the soil mycobiome. Global and regional initiatives intending to capture all available types of fungal community data, combined with paired environmental metadata, across time (Andrew et al. 2017, Větrovský et al. 2020) have the potential to scale our understanding of global change effects on soil fungi to a global level.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (21-17749S). LBD was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (CZ02.2.69/0.0/0.0/18_053/0017705).

DECLARATION ON CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material: https://studiesinmycology.org/

Selection criteria for the inclusion of studies describing effects of global change manipulation on fungi.

REFERENCES

- Ackerman D, Millet DB, Chen X. (2019). Global estimates of inorganic nitrogen deposition across four decades. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 33: 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Adair EC, Reich PB, Trost JJ, et al. (2011). Elevated CO2 stimulates grassland soil respiration by increasing carbon inputs rather than by enhancing soil moisture. Global Change Biology 17: 3546–3563. [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen SHK, Ylänne H, Väisänen M, et al. (2021). Reindeer grazing history determines the responses of subarctic soil fungal communities to warming and fertilization. New Phytologist 232: 788–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JM, Diez JM, Levine JM. (2015). Novel competitors shape species’ responses to climate change. Nature 525: 515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CD, Macalady AK, Chenchouni H, et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest Ecology and Management 259: 660–684. [Google Scholar]

- Alteio LV, Séneca J, Canarini A, et al. (2021). A critical perspective on interpreting amplicon sequencing data in soil ecological research. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 160: 108357. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Garrido L, Vinegla B, Hortal S, et al. (2019). Distributional shifts in ectomycorrizhal fungal communities lag behind climate-driven tree upward migration in a conifer forest-high elevation shrubland ecotone. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 137: 107545. [Google Scholar]

- Anderegg WRL, Kane JM, Anderegg LDL. (2013). Consequences of widespread tree mortality triggered by drought and temperature stress. Nature Climate Change 3: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew C, Heegaard E, Hoiland K, et al. (2018). Explaining European fungal fruiting phenology with climate variability. Ecology 99: 1306–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]