Abstract

Toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) is a colonization factor required for cholera infection. It is not a strong immunogen when delivered in the context of whole cells, yet pilus subunits or TcpA derivative synthetic peptides induce protective responses. We examined the efficacy of immunizing mice with TCP conjugated to anti-class II monoclonal antibodies (MAb) with or without the addition of cholera toxin (CT) or anti-CD40 MAb to determine if the serologic response to TcpA could be manipulated. Anti-class II MAb-targeted TCP influenced the anti-TCP peptide serologic response with respect to titer and isotype. Responses to TcpA peptide 4 were induced with class II MAb-targeted TCP and not with nontargeted TCP. Class II MAb-targeting TcpA reduced the response to peptide 6 compared to the nontargeted TCP response. Class II MAb-targeted TcpA, if delivered with CT, enhanced the serologic response to TcpA peptides. The effectiveness of the combination of targeted TCP and CT was reduced if anti-CD40 MAb were included in the primary immunization. These data establish the need to understand the role of TCP presentation in the generation of B-cell epitopes in order to optimize TcpA-based cholera vaccines.

Cholera is an acute diarrheal disease caused by Vibrio cholerae. Following ingestion of contaminated food or water, bacteria colonize the small intestine and secrete cholera toxin (CT), which is responsible for excessive water loss. A number of live-attenuated- and killed-whole-cell vaccines have been tested. None have proven successful enough to prevent cholera in areas of endemicity (2).

The major virulence factors of V. cholerae are CT and toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) (13, 14; reviewed in reference 16). TCP, a type 4 pilus, is a homopolymer of 20.5-kDa TcpA pilin subunits. TCP is immunogenic and a virulence factor of V. cholerae mediating colonization of the human intestine (27–29, 31, 34). Because of culture conditions, there is little TCP antigen in killed-whole-cell cholera vaccines (27). TCP is not a “dominant” immunogen upon oral infection or experimental vaccination of humans (13). In North American volunteers, a single dose of V. cholerae O1 strain O395 induced a nominal antibody (Ab) response to TcpA. However, 50% of patients from an area in which cholera is endemic had immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA Abs specific for TcpA, suggesting that multiple exposures can induce an anti-TCP Ab (13).

Paradoxically, TcpA and peptides derived from it are very immunogenic and can induce protective Abs when not delivered in the context of a natural infection or vaccination with intact bacteria (27–29, 34). These anti-TCP Abs provide high levels of protection against virulent V. cholerae in the infant mouse assay (27, 28). Similar results were obtained with TcpA-specific monoclonal Abs (MAb), as well as with polyclonal antisera raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to a region of TcpA adjacent to the sequences recognized by the MAb (28, 29). Results of several experimental approaches have indicated that domains within the C-terminal region of TcpA (amino acids 145 to 199) delineated by a single disulfide bond are directly responsible for the protective Ab response seen in animals immunized with intact TCP (13, 14, 17, 28, 29). Three peptides, TcpA4, TcpA5, and TcpA6, induce immune responses in mice that can protect 50 to 89% of infant mice against a challenge with 100 times the 50% lethal dose (29).

While synthesis of TcpA peptides and their use as immunogens might be possible, we wanted to investigate the potential of using intact TcpA as an immunogen with and without additional treatments that might improve TcpA's immunogenicity. Understanding of the roles of various antigen-presenting cell (APC) surface molecules and cytokines in modulating immune responses has facilitated the rational development of vaccination strategies. Collectively these treatments, which can manipulate the immune response, we define as biological response modifiers (BRM). In our study, we focused on three BRM: CT, class II MAb targeting of antigen, and CD40 ligation. CT enhances the immunogenicity of relatively poor mucosal immunogens (6, 18). Targeting vaccine antigens to class II molecules enhances access of APCs to antigen and links signals from the targeted molecules to the temporal acquisition of antigen (9, 24, 35). CD40 ligation on dendritic cells (DCs) and B cells is known to modify immune responses. One group reported that CD40 ligation could augment T-cell-independent serologic responses to pneumococcus antigens (8). Another group reported that immunization with DNA encoding the CD40 ligand could enhance the immune response to respiratory syncytial virus DNA vaccines (32).

We report that the immune response to TCP peptides of mice that have been immunized with intact TcpA can be modulated by class II MAb targeting of the TCP and two BRM, CT and anti-CD40 MAb. The dynamics of the anti-TCP peptide responses after immunization with intact TCP are remarkable and suggest that the immunogenicity of TCP depends on how it is delivered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal manipulation.

Young (8- to 12-week-old) female CBA/jNIA mice were purchased from the National Institute of Aging colony. They were housed in the Animal Resources Center at Dartmouth Medical School, where they were provided with a TekLad rodent diet (Harlan, Madison, Wis.) and water ad libitum. Three mice per group were anesthetized using Metofane (Mallinckrodt Veterinary, Inc., Mundelein, Ill.) and groups A, B, and D were inoculated on the right flank for subcutaneous (s.c.) injections with sterile solutions using tuberculin syringes fitted with a 27-gauge needle. For intranasal (i.n.) inoculations, mice (group C) were anesthetized with Metofane and 10 μl of antigen was dripped into each nostril. A group is defined by a particular treatment modality; for example, group A1 consists of mice immunized with TcpA alone and group B1 consists of mice immunized with class II-targeted TcpA.

Blood collection at different time points in the experiments was performed on anesthetized mice through the retro-orbital sinus. Initial immunizations were performed on day 0, followed by serum collection to assess the primary responses at day 21. Mice were immunized (groups A to D) s.c. with either 3 μg of soluble TCP (conjugated or not) at day 0 and either 1 μg of CT or 1 μg of CT plus 10 μg of anti-CD40 MAb. Mice in groups A to C were boosted on day 28 s.c. with 5 μg of whole TCP, while mice in group D were boosted intravenously (i.v.) via the tail vein with 7.2 μg of whole TCP on day 6 after the primary immunization. All mice were bled on days 21 and 37 to assess the serologic response to TCP.

Conjugate and targeting-construct preparation.

TCP was purified as described previously (27). Purified MAb FGK-44.5, an anti-murine CD40 MAb (a gift from A. Rolnik, Basel, Switzerland) and MAb 10.2.16 (anti-class II MAb) were produced in-house by protein A affinity chromatography (22). Anti-class II MAb-TCP conjugates were produced essentially as described by Carayanniotis and Barber (5). Briefly, TCP and protein A-purified anti-I-Ak MAb (10.2.16) were replaced with biotin (Pierce Chemicals, Rockford, Ill.) and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C before conjugation with 652.6 μg of avidin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). The molar ratio of TcpA, antibody, and strepavidin used for these studies was 1:1:0.4, respectively. The TCP–anti-class II MAb complexes were separated from free TCP by Sephadex G75 chromatography to yield a class II MAb targeting construct that was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting (data not shown).

Serologic analysis.

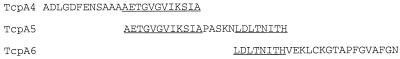

Ninety-six well enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)/radioimmunoassay plates (Costar, Corning, N.Y.) were coated with 10 μg of TCP peptide/ml in phosphate-buffered saline–0.04% sodium azide for 4 h and then washed and stored at 4°C until used. TcpA peptide 4, peptide 5, and peptide 6 (Fig. 1) were synthesized commercially and diluted in buffer for binding to ELISA plates. Underlined sequences are areas where peptides have overlap (peptide 4 to 5 and peptide 5 to 6). Serial twofold dilutions of experimental sera (prebleed, primary [day 21], or secondary [day 37] antisera) or hyperimmune positive-control sera were incubated in coated plates overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer (BBS; 0.05% Tween 20, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% bovine serum albumin, 0.04% sodium azide) at initial dilutions of between 1:100 and 1:200 for IgG analysis or 1:25 for IgA analysis. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgM, and IgA (serum Ig) or anti-IgG2a, anti-IgG1, and anti-IgA MAb (KPL, Gaithersburg, Md., or Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.) were incubated at dilutions of 1:1,000 or 1: 5,000 in BBS without sodium azide for 2 h at room temperature followed by extensive washing. The color reaction was developed using ABTS (2,2′-azinobis[3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid]; KPL, Gaithersburg, Md.) for 30 min and quantified using a Molecular Devices (Menlo Park, Calif.) 96-well plate reader set to 405 nm. The serum titer is reported as the reciprocal of the last dilution that was above zero after subtracting twice the mean optical density values for blank background wells. Prebleed sera were negative at the level of the background wells. As reported, titers must differ by fourfold or more for the difference to be considered significant (12). In our laboratory, the typical standard deviation for TCP ELISA titers that range from 100 to 100,000 is 37.08 ± 46.16. If these values were used to calculate the maximum titer bound by a particular confidence interval, a titer of 100 that has added to it the mean standard deviation (37.1) plus two standard deviations (92.2) of that mean would have an upper limit of 230.4. In our studies, we would not consider this titer significantly different even though a titer of 230 would account for 95% of the values that are possible from a normally distributed population of titers. Our constraint for significance requires that the titers differ by more than four standard deviations and thus represents a conservative estimate of significant differences.

FIG. 1.

TcpA peptide sequences of antigens used in ELISA. Peptides 4, 5, and 6 were synthesized based on the predicted amino acid sequences encoded by the classical biotype strain O395 TcpA gene. Peptide lengths are 24-mer for TcpA, 25-mer for TcpA5, and 26-mer for Tcp6. The overlaps between peptides 4 and 5 and 5 and 6 are underlined.

RESULTS

Serum Ab responses to TCP peptides 4, 5, and 6 is modulated by targeting and CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb.

Developing vaccines in ways that maximize responses to relevant protective antigens is an important consideration, especially if the protective antigen is not intrinsically immunodominant in the context of the whole bacteria. We hypothesize that the context of TCP with respect to the protein itself or other immunodominant proteins of V. cholerae can influence the serologic response directed at protective TCP epitopes.

Specific MAb conjugated with antigens have been used to target antigen to surface molecules on APCs and have been found to be an effective means to induce serologic responses without adjuvants (5, 9, 24). Targeting antigen to selected surface molecules provides signals to the APCs contemporaneous with antigen for more-effective immunization. To determine if the serologic response to TCP peptides could be manipulated, we targeted TCP to major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules via anti-class II MAb-TcpA conjugates. We also examined the additional effects of other BRM, CT, and anti-CD40 MAb. These BRM function as adjuvants for APC by modulating the APC presentation phenotype and/or the cytokine environment (3, 4, 8, 9, 12, 32). CBA/jNIA mice were immunized, and the total serum antibody responses to TCP peptides 4, 5, and 6 were assessed (Table 1). In Table 1, the corresponding groups are compared; thus group A1 is compared to B1. The mice in groups A1 to A3 were treated with nontargeted TcpA and are always the control for other comparisons of class II MAb-targeted TcpA with or without other BRM.

TABLE 1.

Total serum anti-TCP peptide response to different TCP immunization methods

| Groupb and treatment (subgroup) | Titerc at indicated day for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide 4

|

Peptide 5

|

Peptide 6

|

||||

| 21 | 37 | 21 | 37 | 21 | 37 | |

| A | ||||||

| TCP pure (A1) | <100 | <100 | 200 | 12,800 | <100 | <100 |

| TCP + CT (A2) | <100 | 100 | 100 | 800 | 200 | 1,600 |

| TCP + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (A3) | <100 | 100 | 400 | 12,800 | 100 | 3,200 |

| B | ||||||

| TCP/MHC-II conj (B1) | <100 | <100 | <100 | 800 | <100 | 400 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT (B2) | 100 | 1,600 | 200 | 12,800 | 800 | 400 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (B3) | <100 | 100 | 200 | 800 | 100 | 800 |

| C | ||||||

| TCP/MHC-II conj (C1) | <100 | 6,400 | <100 | 6,400 | <100 | 200 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT (C2) | <100 | <100 | <100 | 100 | <100 | 100 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (C3) | 100 | 200 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 200 |

| D | ||||||

| TCP/MHC-II conj (D1) | 400 | 100 | 3,200 | 1,600 | 400 | 400 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT (D2) | 800 | 400 | 12,800 | 12,800 | 1,600 | 3,200 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (D3) | 1,600 | 800 | 6,400 | 3,200 | 1,600 | 800 |

Serum antibodies (IgM, IgA, and IgG) are specific for anti-TcpA peptides 4, 5, and 6. Titers must differ by fourfold or more for the difference to be significant.

Groups A, B, and D received the primary immunization at day zero, s.c. Group C was immunized at day zero via i.n. instillation. Groups A to C were boosted s.c. at day 28. Group D was boosted i.v. at day 6. Group A received nontargeted TCP, while groups B to D received class II MAb-targeted TcpA. TCP/MCH-II conj, TCP targeted to MHC class II molecules via anti-class II MAb-TcpA conjugates.

The control for the comparisons is always group A to either B, C, or D. Titers in boldface represent titers that are significantly greater than those in the corresponding control group (e.g., peptide 4, A2 versus B2 at day 21 or 37). The underlined titers are significantly less than those for the corresponding control group. (e.g., peptide 5, A1 versus C1 at day 21).

Peptide 4 responses.

Immunization of mice with nontargeted TCP (group A) does not induce a high-titer immune response to peptide 4 at 21 or 37 days postimmunization. The inclusion of CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb provides for a marginal response seen at day 37 for mice immunized with nontargeted TCP compared to mice immunized with nontargeted TCP and no BRM. At 21 days, class II targeting of TCP can induce a modest response to peptide 4 if CT is included in the initial inoculum (group B2). Similar to that induced by nontargeted TCP, the response to peptide 4 is not high, except in one case at 37 days (group B2). Mice immunized i.n. with class II MAb- targeted TCP (group C) did not respond unless both CT and anti-CD40 MAb were included in the inoculum. BRM modifiers were in general without effect if TcpA was targeted by class II MAb after i.n. instillation. Targeting TCP to class II MAb and providing CT and anti-CD40 MAb in the initial inoculum with an i.v. TCP booster 6 days after the primary immunization significantly boosted the anti-TCP peptide 4 response (group D compared to group A). (Titers from day 21 or day 37 for group D should be compared only to the day 37 titers of groups A to C, as they [groups D1 to D3] received two doses of antigen before day 21, while at 21 days groups A to C received one dose of antigen.) The titers of group D mouse sera at days 21 and 37 were higher than those of group A mouse sera at day 37. Providing an i.v. TCP antigen boost at 6 days postimmunization is more effective than an s.c. boost at day 21.

Peptide 5 responses.

After 21 days, peptide 5 was immunogenic in the context of immunization with nontargeted TCP (group A). The BRM, CT, and anti-CD40 MAb were without significant effect for nontargeted TCP. Class II MAb-targeted TCP (groups B and C) was not more effective at inducing an anti-TCP peptide 5 response, as evidenced by a comparison of day 21 titers with those of nontargeting TCP. Inclusion of other BRM reduced the titers in groups B1 and C1 to C3 compared to nontargeted-TCP responses. Compared to those from group A, titers from groups B and C were generally low at day 37 with two exceptions: C1 was similar to the group receiving no CT and/or anti-CD40 MAb treatment and titers of B2 were higher than those from the group receiving nontargeted TCP and CT. Unlike what was found for peptide 4, where all treatments for group D were superior to the corresponding treatments for group A, targeting TCP to increase the anti-peptide 5 response was only effective in treatment group D2. These data suggest that for group D targeting TCP to class II MAb is not an effective means to induce Abs to TCP peptide 5. It also indicates that the differences in the dose (5 μg for group A versus 7.2 μg for group D) of the boost do not impact the magnitude of the subsequent serologic responses.

Peptide 6 responses.

Immunization with nontargeted TCP and BRM was the only means of inducing a modest anti-peptide 6 response at day 21 that matured into a significant response at day 37. Targeting TCP to class II molecules (groups B and C) did not enhance the day 21 response to peptide 6 except for group B2 when CT was used. Responses at day 37 for groups B2 and B3 and C2 and C3 (targeted TCP and CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb, respectively) were lower than those in mice immunized with nontargeted TCP and the BRM. This is in contrast to what was found for groups B1 and C1, which had a significant response (day 37) compared to group A1. Group D, which received the i.v. TCP boost, had an enhanced response to peptide 6 only if class II MAb targeting was not accompanied by other BRM treatment. While the response of group D mice that were given CT and anti-CD40 MAb was not different from the response for equivalent treatments in group A, the response of group D mice to peptide 6 compared to responses to targeted TCP of groups B and C, which also received one or both of those BRM, was enhanced in selected cases. This was apparent in group C (day 37), which received CT alone or both CT plus anti-CD40 MAb (D2 and D3 versus C2 and C3). These data suggest that targeting of antigen in the context of other BRM generally has a detrimental effect on serologic response to TCP peptide 6 unless a day 6 i.v. boost is provided.

IgG1, IgG2a, and IgA responses to TCP are modulated by targeting and BRM.

We examined the sera for anti-TCP peptide responses that are indicative of either a Th1 (IgG2a), a Th2 (IgG1), or an IgA response (serum IgA to determine if the difference in serologic responses between the groups was regulating isotype and subclass responses). The data in Table 2 suggest that at day 21 IgG1 and IgA benefited from targeting TCP and the inclusion of CT and/or anti-CD40 MAb. IgG2a was elevated in some groups (B2, C1, and D2 and D3) later in the response.

TABLE 2.

Anti-TCP isotype and subclass responses and peptide specificitya

| Groupb and treatment (subgroup) | Titerc at indicated day and Ig for:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide 4

|

Peptide 5

|

Peptide 6

|

||||||||||||||||

| 21

|

37

|

21

|

37

|

21

|

37

|

|||||||||||||

| IgG1 | IgG2a | IgA | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgA | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgA | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgA | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgA | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgA | |

| A | ||||||||||||||||||

| TCP pure (A1) | <25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 125 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| TCP + CT (A2) | <25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 125 | 125 | 25 | 25 | 25 | <25 | 625 | 125 | 25 |

| TCP + CT anti-CD40 MAb (A3) | 25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | <25 | <25 | 625 | 625 | 250 | 125 | <25 | <25 | 3,125 | 625 | 126 |

| B | ||||||||||||||||||

| TCP/MHC-II conj (B1) | <25 | <25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 25 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT (B2) | 125 | <25 | 25 | 625 | 125 | 25 | 125 | <25 | 250 | 3,125 | 125 | 250 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 625 | 125 | 25 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (B3) | 125 | <25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 | 125 | <25 | 125 | 625 | 125 | 250 | 125 | <25 | 25 | 625 | 125 | 25 |

| C | ||||||||||||||||||

| TCP/MHC-II conj (C1) | <25 | <25 | 25 | 125 | 125 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 25 | <25 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT (C2) | 125 | <25 | 25 | 625 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 625 | 25 | 125 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| TCP/MHC-II conj + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (C3) | <25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| D | ||||||||||||||||||

| TCP/MHC II conj (D1) | 25 | <25 | <25 | 125 | 25 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 25 | 125 | 125 | <25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| TCP/MHC II conj + CT (D2) | 125 | <25 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 3,125 | 125 | 25 | 3,125 | 625 | 25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 625 | 625 | 125 |

| TCP/MHC II conj + CT + anti-CD40 MAb (D3) | 25 | <25 | 25 | 125 | 625 | 25 | 125 | 125 | <25 | 125 | 625 | 25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 25 | 125 | <25 |

IgG1, IgG2, and IgA titers are specific for anti-TcpA peptides 4, 5, and 6. Titers must differ by fourfold or more for the difference to be significant.

Groups A to D and TCP/MHC-II conj are as defined for Table 1.

The comparisons are always to members of group A and within a subgroup of that group, e.g., A1 to B1 or A3 to C3. Titers in boldface represent titers that are significantly greater than those in the corresponding control group (e.g., peptide 4, A2 versus B2 at day 21 or 37; IgG1 and IgA). The underlined titers are significantly less than those for the corresponding control group (e.g., peptide 5, A3 versus C3 for 21 day titers. IgG1).

Peptide 4 responses.

Immunization with intact TCP did not lead to detectable IgG1, IgG2a, or IgA responses 21 days after primary s.c. immunization, except in groups B and C (both class II MAb-targeted TCP), as is most notably evident in the mice that were also given CT (groups B2 and C2) or CT and anti-CD40 MAb (group B3). In the groups (B2, C2, and D2) that were immunized with anti-class II MAb-targeted TCP and CT, the mice responded in general with a modest increase in serum IgA compared to the response to the nontargeted antigen (group A2). Consistent with the lack of response to immunization with whole TCP, mice immunized with targeted TCP with or without other BRM did not generate an anti-TCP peptide 4 IgG2a Ab (day 21), which is indicative of a lack of stimulation of a Th1-type serologic response. Targeting TCP with anti-class II MAb and providing CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb increased the IgG1 response significantly over that to nontargeted TCP at day 37 in selected subgroups for which the method of immunization and boost varied.

Group D mice (day 21 group D versus day 37 group A) had variable anti-peptide 4 responses compared to group A. If both CT and anti-CD40 MAb or neither was included in the immunization, the IgG1, IgG2a, and IgA titers were lower in all but one of the targeted-TCP group. The use of CT alone in group D results in similar responses to those seen in group A2. After several weeks (day 37), the lack of response in group D, which received CT and anti-CD40 MAb, is only apparent in the IgA antipeptide response (D1 and D2) and interestingly the IgG2a response becomes greater than that seen for groups A1 and A2.

The differences noted in the response to peptide 4 (group B) at 21 days that were dependent on the targeting of TCP and other BRM were variable at 37 days. In group B3 the responses were normalized to or were lower than those in group A3. In group B, class II MAb targeting of TcpA by the s.c. route generally increased the IgG1 titers (days 21 and 37) but was without effect on the IgA titers (day 37). Anti-CD40 MAb administration (group B3) had a negative effect on the IgG2a and IgA titers at day 37. A pattern of responses similar to that for group B was seen if the TCP was delivered by anti-class II MAb i.n. In group C3, the anti-CD40 MAb diminished the serologic response at day 37 for all isotypes and subclasses examined.

Immunization with anti-class II MAb-targeted TCP followed by an i.v. boost with antigen 6 days after the initial antigenic exposure shifted the response (day 37) to IgG2a but diminished the IgA response in two out of three subgroups. As reported in Table 1, targeting TCP to class II MAb induced a response to peptide 4 at 21 days, which was maintained at day 37. This difference was not as apparent when only total serum anti-TCP peptide 4 responses were examined.

Peptide 5 responses.

The individual subclass and isotype responses (day 21) to peptide 5 were low or absent in mice immunized with nontargeted TCP. BRM was not regularly effective at modulating the anti-peptide 5 response to nontargeted TCP. TCP targeted to class II molecules with CT and/or anti-CD40 MAb included in the inoculum significantly affected the IgG1 titers and IgA titers (compare B2 and B3 to A2 and A3). Targeting TCP to class II MAb via i.n. instillation was generally ineffective or detrimental to the anti-peptide 5 response, as evidenced by the day 21 titers. However, group C sera at 37 days contained an anti-peptide 5 response that was variable compared to sera of the equivalent subgroup in group A. CT with i.n. instillation of class II MAb-targeted TCP enhanced the IgG1 and IgA responses at day 37. Again, the inclusion of anti-CD40 MAb in the primary immunization (group C3) reduced the response to TCP peptides.

Similar to what was found for peptide 4, the TCP boost at 21 days increased the anti-TCP peptide 5 response at 37 days postimmunization. The anti-TCP peptide 5 IgG1 (B2 and B3, 125; A2, 125) and IgA (B2, 250; A2, 25) responses at day 37 postimmunization were higher in mice immunized with targeted antigen and CT than in group A mice that had been given nontargeted TCP and CT. Comparing the day 37 responses for group A and the day 21 response for group D reveals a variable response depending on the BRM. There was a large increase in the IgG1 anti-TCP peptide 5 Ab (group D2), but the other comparisons were generally not different except for those concerning group D3, the response in which was decreased if anti-CD40 MAb and CT were included at the primary immunization followed by a day 6 i.v. boost. Groups C and D did not consistently sustain the IgA titers, unlike groups A and B.

Peptide 6 responses.

Immunization with intact, nontargeted TCP was more immunogenic for peptide 6 responses at day 21 than anti-peptide 4 or 5 responses. Targeting TCP to class II MAb increased the IgA response at 21 days if CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb were included in the primary inoculum. The IgG1 response to peptide 6 was reduced in groups C2 and C3 and D2 and D3 compared to the response reported for groups A2 and A3. The IgG2a response at day 21 to peptide 6 was generally absent from groups C and D. Compared to what was found for the anti-peptide 4 and 5 responses following targeted TCP immunization, the anti-class II MAb targeting on day 21 did not enhance the serologic response in the IgG compartment but did maintain the capacity to induce some anti-peptide 6 IgA responses.

The magnitudes of the responses to peptide 6 at day 37 in mice immunized with nontargeted TCP (group A) were similar to those of the anti-peptide responses (group A) to peptides 4 and 5. This is in contrast to the response at 37 days of mice immunized with targeted TCP. Targeting TCP to class II molecules was less efficacious for the anti-peptide 6 response for groups B to D than using nontargeted TCP. In general, the anti-peptide 4 and 5 responses of groups B to D were superior to the anti-peptide 6 response at day 21 or 37. Group D mice with one exception (D3; IgA) respond to peptide 6, and the responses are generally low at day 37 for group D. As seen with groups A to C, CT was effective at either maintaining or enhancing the response of group D2 mice.

Effect on anti-peptide 4, 5, and 6 TCP responses correlates with the type of immunization and BRM treatment.

Given the multiple comparisons possible with the data in Table 2, we attempted to simplify the analysis by comparing the IgG1, IgG2a, and IgA responses of groups B to D to those of group A but only within a given treatment modality, e.g., B1 to A1, i.e., mice given TCP targeted or not without BRM. For the comparisons within group A, the anti-TCP serologic response without targeting or other BRM (group A1) was compared to those for nontargeted TCP and either CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb (A2 and A3, respectively; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Increase or decrease in anti-TCP peptide titersa

| Group (treatment) | No. of responses of 18 tested (%) showing:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Increase in titer | Decrease in titer | |

| A1 (nontargeted) | Standard | Standard |

| A2 (nontargeted, CT) | 6 (33.3) | 1 (5.5) |

| A3 (nontargeted, CT, anti-CD40 MAb) | 11 (61.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| B1 (class II targeted) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (5.5) |

| B2 (class II targeted, CT) | 9 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| B3 (class II targeted, CT, anti-CD40 MAb) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (33.3) |

| C1 (class II targeted) | 3 (16.6) | 2 (11.1) |

| C2 (class II targeted, CT) | 6 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) |

| C3 (class II targeted, CT, anti-CD40 MAb) | 1 (5.5) | 12 (66.7) |

| D1 (class II targeted) | 1 (5.5) | 9 (50.0) |

| D2 (class II targeted, CT) | 8 (44.4) | 3 (16.6) |

| D3 (class II targeted, CT anti-CD40 MAb) | 1 (5.5) | 15 (83.3) |

The individual groups for a given treatment from Table 2 were tabulated based on an increase in the anti-TCP peptide titer or a decrease in the anti-TCP peptide titer. The percent effect was calculated based on 18 different group responses to a group treatment. The comparison was made either to the common regimen, A1 to B1, A1 to C1, etc., or, for group A, A1 to A2 and then A1 to A3. The majority of the comparisons of effects within the group, i.e., B1 to B2 or B2 to B3, provide information relative to the effect of the BRM, CT, and anti-CD40 MAb. Comparisons between the groups account for the method of immunization.

The serologic response for nontargeted TCP with CT (33.3% of the anti-TCP peptide responses increased) or CT plus anti-CD40 MAb (61.1% of the anti-TCP peptide responses increased) was increased. The effect of class II MAb targeting and other BRM was both positive and negative. Class II MAb-targeted TCP was more effective at inducing responses than nontargeted TCP. The s.c. delivery of class II MAb-targeted immunogen was comparable to i.n. (group C) delivery, and both were superior to s.c. primary immunization and i.v. boost (group D). If CT was included in the immunizing inoculum with class II MAb-targeted TcpA, the anti-TCP peptide titers were further increased: B2 versus B1, 50.0 versus 22.2%, respectively; C2 versus C1, 33.3 versus 16.6%, respectively; D2 versus D1, 44.4 versus 5.5%, respectively. The i.v. boost was approximately fourfold less effective (group B to group D) than the s.c. boost if class II MAb-targeted TCP was first provided s.c. Similarly, when D3 was compared to B3, it was found that the response was again about fourfold lower in the i.v.-boosted group. The use of CT with targeted or nontargeted TcpA clearly enhanced the anti-TcpA response of mice to TcpA peptides 4, 5, and 6. However, the positive response induced by the CT treatment can be mitigated by the addition of anti-CD40 MAb to the immunization regimen. The CD40 effect lowers the serologic response to either what was obtained with just class II MAb-targeted TcpA alone or in one case (C3) below what is seen with class II MAb-targeted TcpA.

Interestingly, in nontargeted TCP, anti-CD40 MAb did not decrease any of the titers and in 61% of the cases improved the response. It is apparent that adding anti-CD40 MAb to the immunization significantly affects the serologic response in multiple groups, but in a negative manner for the class II MAb-targeted TCP. The rank order of the negative effect of anti-CD40 MAb treatment of TcpA peptide titers was D3 (83%), C3 (67%), and B3 (33%). Clearly, the route of immunization of class II MAb-targeted TCP is related to the effect that the anti-CD40 MAb has on the anti-TcpA peptide titers.

DISCUSSION

Cholera is an enteric disease caused by V. cholerae infection. The current killed-whole-cell and attenuated-live cholera vaccines have differential efficacy depending on the target population and the time after vaccination and primary infection (11). The killed-whole-cell vaccines do not protect as long as is desirable. The live-attenuated vaccines work well in North Americans but have not been demonstrated to protect those in areas where cholera is endemic (11). Several antigens that are thought to induce protection against cholera infection include lipopolysaccharide, CT, TCP, and outer membrane proteins (13, 14, 21, 26).

TCP or peptides derived from it can induce protective responses in animals (27–29, 34). Their utility as immunogens in the context of live-whole-cell and killed-whole-cell cholera vaccines is unproven. Multiple exposures of individuals in areas of endemicity can result in seroconversion to TCP (13). The issues that compromise TCP immunogenicity in the context of whole-cell vaccines could relate to (i) availability or the amount of the TCP antigen in the vaccines and (ii) its immunogenicity (B- and T-cell epitopes), both intrinsic and in the context of other immunodominant antigens. There is an evolving literature that documents changes in the immune response to protein antigens when BRM are added to an immunization regimen. In our system, we focused on targeting antigen to class II molecules and inclusion of CT or anti-CD40 MAb as a means to modify anti-TCP responses. Class II MAb targeting is a well-documented method (5, 9, 24, 25) to enhance the immunogenicity of targeted proteins. Our results clearly indicate that class II MAb-targeting TCP and/or other BRM can influence the isotype of the Ab response as well as the magnitude of the response to TCP peptides. The mechanism of the effect of class II MAb targeting of antigen is not known. Increased access of targeted antigen to DCs and perhaps signals from class II molecules that upregulate costimulatory molecules CD80 or CD86 could enhance the presentation capacity of the APCs (20). Class II MAb signaling also increases tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), both of which can affect maturation and antigen processing of immature DCs (1, 7, 23, 35).

BRM such as CT or CD40 signaling can influence the efficiency of T-cell activation and Ab production by regulating substrates (MHC-II peptide) and cytokines for clonal activation of both B and T cells (19, 33). CT is an adjuvant that has been shown to increase the IgA responses to coinjected antigens targeted to class II molecules (3, 4, 25). CD40 ligation is known to enhance APC function for a number of antigens (8, 10, 15, 32). In vivo CD40 can mature DCs to increase their effectiveness as APC by stimulating the processing of antigen and the charging of class II MAb with peptides (Frleta and Wade, unpublished observations). CD40 ligation can enhance expression of CD54, CD80, CD86, and class II molecules. CD40 stimulation enhances secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-6.

The mechanism whereby class II MAb targeting and CT or CT and anti-CD40 MAb treatment modulates anti-TcpA peptide responses is not known. The potential dynamics of BRM manipulations are perhaps illustrated by IL-6, a cytokine made in response to class II MAb targeting, and the other BRM. IL-6 can regulate the processing of hen egg lysozyme in DCs (7). Normally, immunodominant binding peptides are processed in DCs, but, if IL-6 is added, the immunodominant peptides are no longer generated and cryptic peptides are now expressed on class II MAb. One hypothesis consistent with this model is that TCP normally has immunodominant peptides that do not focus T-cell help to optimally activate B cells during infection or immunization with whole cells. Consistent with the immunorecessive hypothesis is the possibility that the conjugation of antigens such as TcpA to anti-class II MAb affects the “conformation” of TcpA and thus can modulate its processing and thus its presentation. This effect may be manifested as the generation of new class II MAb-peptide complexes or as increased levels of TcpA immunodominant peptides that would now be stimulatory. The differential induction of effector Th1 versus Th2 cells based on the amount or type of peptide expressed can regulate the type of Ab generated (reference 30 and references therein).

The mechanism whereby antigen targeting or BRM can change the serologic response to B-cell epitopes (serologic response to peptides 4 to 6) that can either enhance a B-cell response, as for peptide 4, or reduce the response, as for peptide 6, is more complex. B-cell epitopes that provide for Ig ligation and subsequent B-cell activation can be provided by DCs (36). Thus targeting antigen to DCs and the “downstream” effects this would have on the handling of antigen may differentially expose B-cell epitopes or affect the longevity of presentation, both of which would affect subsequent B-cell activation. Alternatively, class II MAb-targeted TCP may target TCP peptide-specific B cells directly and thus make certain anti-TCP peptide responses more effective.

These data illustrate the potential to modulate the immune response to TcpA. In general, anti-class II MAb-targeted TCP induced higher (IgG1 and IgA) responses but had marginal effects on IgG2a in most of the groups at the early time points; these effects could be overcome later in the response. CT enhanced the serum IgG1 and IgA responses for certain peptides. We did not measure secretory IgA in this study. However, it is not clear which isotype is the most protective against cholera in humans. The ability to select appropriate B cells that respond to TcpA peptides 4 and 5 is the limiting element in cholera vaccine development, not devising routes of immunization. Serologic responses to TCP peptides 4 to 6 were not equally affected by the various treatments. Even with other BRM treatment, peptide 6 was not particularly immunogenic if TCP was targeted by class II MAb, but peptide 4 was if CT was added. This is an important observation, as peptide 4 has been shown previously to be the most protective immunogen among peptides 4 to 6 (29).

The responses to TCP could be negatively or positively regulated by anti-CD40 MAb. The positive effect of anti-CD40 MAb was restricted to the nontargeted TCP, while the negative effect of anti-CD40 MAb was seen in the class II MAb-targeted TCP groups. The reason for this is likely related to the number of events at the level of APC that regulate antigen presentation. These events are simplified in the nontargeted TCP group compared to the class II MAb-targeted groups. APCs do not have to accommodate class II MAb and CT signaling along with the CD40 signaling in the nontargeted TCP group.

The mice that were immunized with CT and anti-CD40 MAb in the context of class II signaling induced by class II MAb-targeted TCP had a restrictive serologic response to the TcpA peptides. That was evident in anti-peptide 4, 5, and 6 responses but seemed to be centered on the anti-peptide 6 responses and also on the responses to all peptides in groups C and D. The difference between groups C and D and group B is the site of immunization, i.n. for group C, and the timing and physiological context of the TCP boost for group D, 6 days i.v. versus 21 days s.c. The mechanism by which CD40 ligation results in lower serologic responses is not known, but we have noted the lower response of mice immunized with antigen and anti-CD40 MAb (12). We speculate that this is due to the maturing effect of CD40 ligation on DCs (23). If DCs are matured too quickly, the ability to internalize membrane receptors and bound antigen is reduced and thus targeted class II MAb may not effectively be internalized for maximal generation of MHC-II peptide complexes. This would clearly affect the T-cell compartment. It is also formally possible that the anti-CD40 MAb is disruptive of the effective cognate interaction of B and T cells. We do not favor this as a universal explanation because, when TcpA is not targeted, the anti-CD40 MAb enhances the serologic response. A direct effect of CD40 ligation may involve B-cell death early in the immunization period. The anti-CD40 MAb activates B cells initially; this is followed by their loss from the cell population in the spleen of anti-CD40 MAb-treated mice (D. Frleta and W. F. Wade, personal observation). The negative CD40 effect on B cells is perhaps amplified by the anti-class II MAb targeting, which is also known to kill B cells. These negative signals are known to be influenced by surface Ig engagement.

These data support our hypothesis that the mode and the “contextual” mechanism of antigen administration can drive differential TCP peptide responses. If we can determine which TCP B-cell epitopes are the most protective, having the ability to manipulate the immune response to focus on that epitope would be an effective vaccine strategy. It is not clear that the experimental manipulations we have used to uncover the dynamics of TcpA presentation are directly applicable to humans. Human APCs are clearly targets for class II MAb-targeted antigens, but CT and anti-CD40 MAb are potentially too reactive for use in humans. In humans, other manipulations, such as directing specific peptides to APCs with cytokine treatment, may mimic the dynamics of class II MAb targeting of TcpA and other BRMs we report here.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants to J.-A.W. (Dartmouth Hitchcock Foundation) and NIH grants to R.K.T. (AI25096) and W.F.W. (AI 47373).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altomonte M, Pucillo C, Maio M. The overlooked “nonclassical” functions of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigens in immune and nonimmune cells. J Cell Physiol. 1999;179:251–256. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199906)179:3<251::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Martine J, deZoysa I, Glass R I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull W H O. 1992;70:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen J C, Nair S K, Reddy R, Rouse B T. Cholera toxin acts as a potent adjuvant for the induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses with nonreplicating antigens. Immunology. 1994;81:337–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromander A, Holmgren J, Lycke N. Cholera toxin stimulates IL-1 production and enhances antigen presentation by macrophages in vitro. J Immunol. 1991;146:2908–2914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carayanniotis G, Barber B H. Adjuvant-free IgG responses induced with antigen coupled to antibodies against class II MHC. Nature. 1987;327:59–61. doi: 10.1038/327059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czerkinsky C, Russell M W, Lycke N, Lindblad M, Holmgren J. Oral administration of a streptococcal antigen coupled to cholera toxin B subunit evokes strong antibody responses in salivary glands and extramucosal tissues. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1072–1077. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1072-1077.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drakesmith H, O'Neil D, Schneider S C, Binks M, Medds P, Sercarz E, Beverly P, Chain B. In vivo priming of T cells against cryptic determinants by dendritic cells exposed to interleukin 6 and native antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14903–14908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dullforc E P, Sutton D C, Heath A W. Enhancement of T cell-independent immune responses in vivo by CD40 antibodies. Nat Med. 1998;4:88–91. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estrada A, McDermott M R, Underdown B J, Snider D P. Intestinal immunization of mice with antigen conjugated to anti-MHC class II antibodies. Vaccine. 1995;13:901–907. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00012-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores-Romo L, Bjorck P, Duvert V, van Kooten C, Saeland S, Banchereau J. CD40 ligation on human cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors induces their proliferation and differentiation into functional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:341–349. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier J M, Villeneuve S. Cholera update and vaccination problems. Med Trop. 1998;58(Suppl. 2):32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frleta D, Demian D, Wade W F. Class II-targeted antigen is superior to CD40-targeted antigen at stimulating humoral responses in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall R H, Losonsky G, Silveira A P, Taylor R K, Mekalanos J J, Witham N D, Levine M M. Immunogenicity of Vibrio cholerae O1 toxin-coregulated pili in experimental and clinical cholera. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2508–2512. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2508-2512.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrington D A, Hall R H, Losonsky G, Mekalanos J J, Taylor R K, Levine M M. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1487–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito D, Ogasawara K, Iwabuchi K, Inuyama Y, Onoe K. Induction of CTL responses by simultaneous administration of liposomal peptide vaccine with anti-CD40 and anti-CTLA-4 mAb. J Immunol. 2000;164:1230–1235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaper J B, Morris J G, Jr, Levine M M. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirn T J, Lafferty M J, Sandoe C M P, Taylor R K. Delineation of pilin domains required for bacterial association into microcolonies and intestinal colonization by Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:896–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lycke N. The mechanism of cholera toxin adjuvanticity. Res Immunol. 1997;148:504–520. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malisan F, Briere F, Bridon J M, Harindranath N, Mills F C, Max E E, Banchereau J, Martinez-Valdez H. Interleukin-10 induces immunoglobulin G isotype switch recombination in human CD40-activated naive B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;183:937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mjaaland S, Fossum S. Antigen targeting with monoclonal antibodies as vectors. II. Further evidence that conjugation of antigen to specific monoclonal antibodies enhances uptake by antigen presenting cells. Int Immunol. 1991;3:1315–1321. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.12.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukhopadhyay S, Nandi B, Ghose A C. Antibodies (IgG) to lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 mediate protection through inhibition of intestinal adherence and colonisation in a mouse model. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;185:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oi V T, Jones P P, Goding J W, Herzenberg L A, Herzenberg L A. Properties of monoclonal antibodies to Ig allotypes, H-2 and Ia antigens. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1978;81:115–129. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-67448-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierre P, Turley S J, Gatti E, Hull M, Meltzer J, Mirza A, Inab K, Steinman R M, Mellman I. Developmental regulation of MHC class II transport in mouse dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;378:787–792. doi: 10.1038/42039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snider D P, Kaubisch A, Segal D M. Enhanced antigen immunogenicity induced by bispecific antibodies. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1957–1963. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.6.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snider D P, Underdown B J, McDermott M R. Intranasal antigen targeting to MHC class II molecules primes local IgA and serum IgG antibody responses in mice. Immunology. 1997;90:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1997.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sperandio V, Giron J A, Silveira W D, Kaper J B. The OmpU outer membrane protein, a potential adherence factor of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4433–4438. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4433-4438.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun D, Mekalanos J J, Taylor R K. Antibodies directed against the toxin-coregulated pilus isolated from Vibrio cholerae provide protection in the infant mouse experimental cholera model. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1231–1236. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun D, Seyer J M, Kovari I, Sumrada R A, Taylor R K. Localization of protective epitopes within the pilin subunit of the Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus. Infect Immun. 1991;59:114–118. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.114-118.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun D, Lafferty M J, Peek J A, Taylor R K. Domains within the Vibrio cholerae toxin coregulated pilin subunit that mediate bacterial colonization. Gene. 1997;192:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swain S L, Bradley L M, Croft M, Tonkonogy S, Atkins G, Weinberg A D, Duncan D D, Hedrick S M, Dutton R W, Huston G. Helper T-cell subsets: phenotype, function and the role of lymphokines in regulating their development. Immunol Rev. 1991;123:115–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tacket C O, Taylor R K, Losonsky G, Lim U, Nataro J P, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Investigation of the role of toxin-coregulated pili and mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin pili in the pathogenesis of Vibrio cholerae O139 infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:692–695. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.692-695.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tripp R A, Jones L, Anderson L J, Brown M P. CD40 ligand (CD154) enhances the Th1 and antibody responses to respiratory syncytial virus in the BALB/c mouse. J Immunol. 2000;164:5913–5921. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. Functions of CD40 on B cells, dendritic cells and other cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:330–337. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voss E, Manning P A, Attridge S R. The toxin-coregulated pilus is a colonization factor and protective antigen of Vibrio cholerae El Tor. Microbiol Pathol. 1996;20:141–153. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wade W F, Davoust J, Salamero J, Andre P, Watts T H, Cambier J C. Structural compartmentalization of MHC class II signaling function. Immunol Today. 1993;14:539–546. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90184-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wykes M, Pombo A, Jenkins C, MacPherson G G. Dendritic cells interact directly with naive B lymphocytes to transfer antigen and initiate class switching in a primary T-dependent response. J Immunol. 1998;161:1313–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]