Abstract

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) has consistently advocated for a healthcare system that meets the needs of older adults, including addressing impacts of ageism in healthcare. The intersection of structural racism and ageism compounds the disadvantage experienced by historically marginalized communities. Structural racism and ageism have long been ingrained in all aspects of US society, including healthcare. This intersection exacerbates disparities in social determinants of health, including poor access to healthcare and poor outcomes. These deeply rooted societal injustices have been brought to the forefront of the collective public consciousness at different points throughout history. The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare and exacerbated existing inequities inflicted on historically marginalized communities. Ageist rhetoric and policies during the COVID-19 pandemic further marginalized older adults. Although the detrimental impact of structural racism on health has been well-documented in the literature, generative research on the intersection of structural racism and ageism is limited. The AGS is working to identify and dismantle the healthcare structures that create and perpetuate these combined injustices and, in so doing, create a more just US healthcare system. This paper is intended to provide an overview of important frameworks and guide future efforts to both identify and eliminate bias within healthcare delivery systems and health professions training with a particular focus on the intersection of structural racism and ageism.

Keywords: ageism, health disparities, intersectionality, racism, social determinants

INTRODUCTION

In June 2020, Americans bore witness to the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police. This pivotal event, amid a surge of racially motivated hate crimes in the US, galvanized many organizations and institutions to commit additional resources toward diversity, equity, inclusion, and antiracism initiatives.1 In healthcare, the outcry protesting race-related violence, including police brutality, occurred against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which data had already emerged showing a greater impact of the pandemic on historically marginalized communities. These communities were experiencing much higher rates of infection and hospitalization from COVID-19 than White communities.2 Older Black Americans, in particular, experienced disproportionately high morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.2 The pandemic has laid bare the disparities that exist in the workforce and training of healthcare professionals, educators, and investigators. Across the US, individuals, organizations, and institutions have recognized that lasting and meaningful change to advance equity will require collaboration and commitment.

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS), a nationwide not-for-profit society of geriatrics health professionals, was among the organizations that expressed opposition to violence rooted in racism, bias, and discrimination. In a statement after the death of Mr. Floyd, the AGS committed to doing more to actively oppose all forms of discrimination in healthcare.3 As a first step, the AGS modified its vision for the future to include the AGS commitment to creating a future in which we are all supported by and contributing to communities where bias and discrimination no longer impact healthcare access, quality, and outcomes for older adults and their caregivers.4 Subsequently, the AGS outlined a multiyear, multicomponent plan to address the intersection of structural racism and ageism in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS).5 The AGS has long championed efforts to oppose ageism, defined as discrimination against a person based solely on their age, across its portfolio of programs and products, but had not focused on the long-standing but under-addressed intersection of structural racism and ageism. Given how little has been written about this intersection, the AGS reached out to us, a diverse group of concerned and committed AGS leaders, and asked us to author this paper on behalf of the Society.

This paper provides an overview of important frameworks that should inform future efforts both to identify and eliminate bias within healthcare delivery systems and train health professionals with a particular focus on the intersection of structural racism and ageism. The language we use in this paper moves between current recommendations from the American Medical Association6 and the language used in the articles we cite (e.g., we use African American when citing research that used that term, and Black American in all other instances). We use minoritized throughout this paper to convey that structural racism is inherently an action taken by a dominant group that subordinates another group. Our approach to addressing the intersection of structural racism and ageism is grounded in the concept of a just healthcare system. A just healthcare system recognizes that membership in groups, whether classified by age, race, gender, socioeconomic status, or other descriptors, should not affect the quality of the healthcare that is delivered or who is trained to deliver that care. A just healthcare system also ensures that all of us receive timely, high-quality care that is responsive to our individual needs and offered with cultural humility.

In the US, healthcare injustices have direct adverse impacts, especially on Black Americans and other racially minoritized groups. These injustices are deeply embedded in the policies, practices, and systems that undergird American institutions, including the healthcare system.7 The lack of access to high-quality healthcare in historically and intentionally excluded urban and rural communities in the US is well-documented, and Black or African American individuals are under-represented as healthcare professionals.8,9 Equally problematic is the practice of using race, a social construct, as a proxy to inform clinical protocols that drive healthcare decision-making. Race-adjusted algorithms that use race as a proxy for biological, genetic, or behavioral risk of disease reinforce racial biases and perpetuate health inequities.10 For example, the equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) overestimates kidney function in Black Americans. This leads to transplant delays and increases the risk of progression to kidney failure.11 A second example is in the assessment of lung function using spirometry; the equation inappropriately uses race12 and could lead to delays in lung transplant as well as decreased likelihood of receiving compensation for occupational lung disease in Black Americans compared with White Americans.13 Many of these clinical protocols and algorithms are currently undergoing critical reevaluation or have already been revised to remove race as a variable.10 A third example involves inaccurate pulse oximetry readings among Asian, Black, and non-Black Hispanic patients that led to delays in diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 infection.14 The pandemic demonstrated how the intersection of age, race, and socioeconomic status contributes to poorer health outcomes for those of all ages in historically marginalized communities, as exemplified by the finding that the location of one’s neighborhood predicts survival from COVID-19.15

The discipline of geriatrics is grounded in a comprehensive, interprofessional, and biopsychosocial approach to patient care. Good geriatrics care promotes well-being and quality of life by customizing care to what matters most to patients with a focus on function and maintaining independence. As such, injustice in any form is an affront to the core values of geriatrics practice.16 When people from historically marginalized groups who have experienced a lifetime of racism then become older, they experience the added injustice of ageism as well. As such, the intersection of structural racism and ageism amplifies the harm resulting from either of these injustices alone. This intersection of structural racism and ageism has received little attention in healthcare but demands further exploration and action.17,18

This paper is divided into sections on (1) structural racism, (2) ageism, (3) the intersection of racism and ageism, and (4) disadvantages related to social determinants of health. The goal is to inform our understanding of these pervasive types of bias in healthcare. In addition, we recommend three initial positive steps that we, together with colleagues in other specialties and disciplines, can take to move us further along the path to a future in which healthcare is free of discrimination and bias that continue to perpetuate disparities.

STRUCTURAL RACISM

Structural racism is a significant driver of healthcare disparities. At its core, structural racism is a powerful collection of organized structures, policies, and practices in society that causes “unavoidable and unfair inequalities in power, resources, capacities, and opportunities across racial or ethnic groups.”19,20 It is mediated through multiple levels of interaction, including individual, interpersonal, and within and across institutions.21,22 Structural racism unjustly harms individuals, populations, and communities through various pathways, including poor quality housing, lack of socioeconomic opportunities, and limited access to quality healthcare, thereby increasing the risk and burden of disease, causing cognitive and psychological effects, and shortening life expectancy. If we are to truly dismantle structural racism, we need to examine its underlying causes and learn to recognize its contributions to racial health inequities. As the AGS comprises geriatrics health professionals, the society recognizes that the healthcare sector is an area in which it and its members can focus their work to reduce the impact of racial health inequities on marginalized communities.

Historical perspectives

To understand structural racism, we must also define and clarify its relationship to the concept of race. Race is a social construct that has been used to categorize human difference based on shared superficial physical characteristics.23 Racism at its core is an ideology and system of power that disparately structures opportunity and assigns value to groups of people based on “race.”19,22 Structural racism “refers to the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, healthcare and criminal justice.”24 Structural racism has had significant negative and harmful consequences throughout US history. One example of this is the enactment of Jim Crow laws in the post-Civil War era in the southern US. These laws led to overt oppression of African Americans that included racial segregation, voter suppression and intimidation, economic and educational disadvantage, brutality, and other injustices until their end in the late 1960s. Despite the legal end of the Jim Crow era, the structural racism that it potentiated has led to many deleterious consequences that are still being felt today, including many documented inequalities in healthcare.25

Another historical example of the effects of structural racism and a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health in the US is the practice of legalized housing segregation, known as “redlining,” that was abetted by the federal government.26 Redlining was practiced by the mortgage lending industry for much of the twentieth century.27 The convergence of these housing policies and practices resulted in generational accumulation of socioeconomic privilege for White families and generations of accumulated socioeconomic disadvantage for people of color and immigrants. Socioeconomic status not only gives access to economic resources but encompasses “knowledge, prestige, power, and beneficial social connections that protect health no matter what mechanisms are relevant at any given time.”28,29,30 Although redlining was made illegal, the legacy and disparate effects of residential segregation persist. In fact, early research in the field of healthcare disparities revealed that legalized housing segregation was a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health.27

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the long-standing and newer structural inequities through its disproportionate health impacts on older adults of color. Along with historic racism and economic and employment loss, older adults of color faced disproportionate adverse effects, including reduced face-to-face interactions with clinicians, gaps in access to essential supplies while isolating, and the physical and mental consequences of social isolation.31,32 In addition, messaging from key US public officials in leadership positions referred to the virus or coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)33 as the “Chinese or Wuhan virus” rather than SARS-CoV-2 and reports of racist and xenophobic incidents directed toward persons perceived to be Chinese or of Asian descent, especially older adults, have increased.34

Although the social construct of race has long been used as a marker of disease risk, it is important to point to the specific underlying “non-biological” causes of racial health disparities that are rooted in structural racism. Limiting the examination of disparities solely based on racial categories may result in healthcare policies that use race as a proxy for myriad risk factors and health indicators without critically examining the underlying structural and social determinants of health as the cause of increased risk for different racial groups. In fact, recent literature has shown that certain social determinants, such as neighborhood characteristics and disadvantage, are powerful predictors of health beyond individual behavior and genetic code.22 Furthermore, it is important to consider the influence of implicit frameworks operating on the interpersonal and individual level as important midstream and downstream mechanisms that perpetuate racial health inequities. Examples from the pandemic include a lack of trust in local healthcare leaders to have the best interest of historically marginalized populations in mind when offering vaccination in communities of color.35

AGEISM

Ageism involves discriminating against a person solely based on age. Age is an identity that can have both negative and positive connotations across the lifespan. Any person could be a victim of ageism. Age, as an identity, intersects with other identities that are discriminated against, including race, gender, class, disability, and sexual orientation.36 Ageism toward older adults is pervasive in the US. Analysis of the 2019 National Poll on Healthy Aging showed that 93.4% of US adults aged 50 through 80 experience microaggressions termed “everyday ageism.”37 Older adults are often depicted in popular culture as of less worth than those in younger age groups and as a burden to society.38 Such discrimination may be subtle but, in the case of older adults, can take the form of individual attitudes or societal policies that result in overt marginalization, social exclusion, and overall unjust treatment.38 For example, older adults are often viewed as both using and being potentially undeserving of an undue amount of healthcare resources.35 In addition, ageism occurs in the exclusion of older adults having varying degrees of decision-making capacity from important decisions affecting their health, finances, or personal relationships. Older adults are often excluded from clinical trials, thereby forcing clinicians to make treatment decisions based on inadequate evidence.39 Although the realities of the physical decline inherent in aging were recognized when the discipline of geriatrics was founded,40,41 there is substantial heterogeneity in the rate of decline, and the mere presence of decline in certain domain(s) does not necessarily mean that an older adult is not capable of performing a specific role or task.

Although older adults accounted for 16.3% of the US population in 201942 and core competencies exist for geriatrics education across the health professions,43 geriatrics education is still not universally included in all health professions training programs. This represents a missed opportunity to develop a healthcare workforce attuned to the needs of older adults. For example, among the few residency programs with geriatric accreditation requirements are family medicine, internal medicine, medicine/pediatrics, neurology, and psychiatry.44,45 For advanced practice nursing, the field has determined that ALL adult advance practice registered nurses (ARPN), either primary care or acute care, should be trained to have specialized knowledge to care for older adults.46 Although the uniform APRN regulations across the four essential elements for licensure accreditation, certification, and education were adopted in 2008 and implemented in 2015, their effects on certification are just beginning to take shape. Simply exposing students to older adult patients, in the absence of a structured didactic geriatrics curriculum, is insufficient to change negative attitudes toward older adults and increase competency in caring for older adults.47 Since 1994, the AGS has been working to address this lack of training specific to care of older adults with its partners from the surgical and related medical specialties and via a parallel initiative led by the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) focused on internal medicine specialties.48,49 Together, the collaborating groups have made progress, but medical residency training in surgical and related specialties and in medicine specialties still lacks specific geriatric requirements.

Examples of both overt and more subtle ageism abounded during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overt ageism was exemplified by pronouncements that older adults were universally frail, that their contributions to society were minimal, and that they did not deserve to be prioritized for COVID-19-related resources.50 Some pronounced that older adults should be prepared to step aside (e.g., relinquish limited healthcare resources to younger adults, or even die).51 Some crisis standards of care codified ageism in tools, such as age-based cutoffs, to determine who would receive intensive care under conditions of resource scarcity, as well as “tiebreakers” for healthcare resources based on age.52 Such resource allocation strategies, in which older adults receive medical care based on a factor they cannot control (e.g., being in a particular age group) rather than on an individualized medical assessment, are inconsistent with a just healthcare system.53 Examples of subtle ageism during the COVID-19 pandemic include the absence of expertise in aging on local, state, and national committees involved with pandemic preparedness and response, as well as visitation policies in hospital and long-term care settings that disproportionately affected older adults and led to a secondary pandemic of social isolation.54,55

The pervasive nature of ageism in society signifies that ageism is insidious and therefore difficult to counter. As a result, concerted efforts are needed to identify and eliminate ageism within healthcare systems as well as society at large.

INTERSECTION OF RACISM AND AGEISM

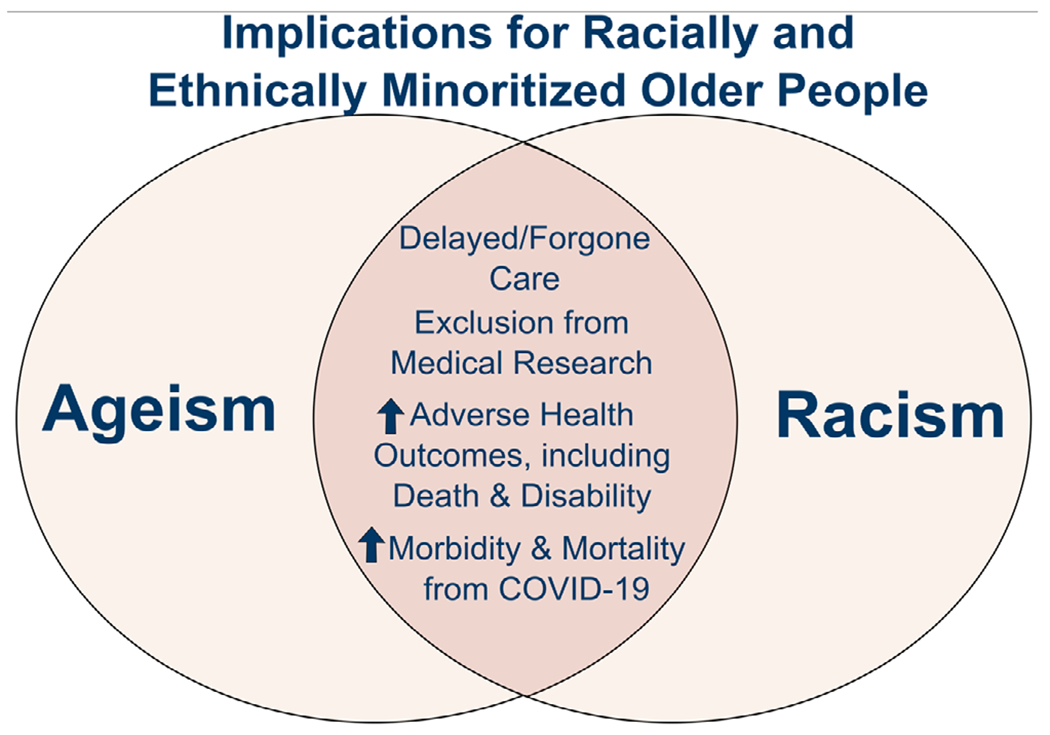

The constructs of racism and ageism can have negative effects on health outcomes that can be magnified when race and age intersect (Figure 1). Fully understanding the implications of the intersection of racism and ageism first requires understanding the concept of intersectionality. Intersectionality is defined as the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination combine, overlap, or intersect, especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups.56 This theory was introduced in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor, scholar, and writer on civil rights and critical race theory,57 as a way to address the way Black American women were marginalized within the mainstream feminist movement.58 Although its origins are rooted in race and sex, intersectionality can be applied to many social identities as the discrimination that is experienced as the result of one’s race or age can combine, overlap, and intersect.

FIGURE 1.

Intersection of ageism and racism in healthcare: a double disadvantage

Other theories and hypotheses also examine the interplay of racism and ageism. One such example is that of the double jeopardy hypothesis.59 This hypothesis states that Black American older adults suffer a “double disadvantage to health” due to the interactive effects of race and age.60 Another theory that has been applied to the effects of racism and other forms of disadvantage over the life course is the cumulative inequality theory, which suggests that social systems generate inequality that manifests over a person’s life and can result in poor health outcomes, including premature mortality.61 There is also the “weathering hypothesis,” which suggests that early declines in health observed in aging Black Americans are the result of repeated exposures to social or economic adversity and political marginalization.62,63

The implications of the intersection, interplay, or cumulative effects of race or racism and age or ageism have been found in the literature. Some research suggests that disadvantage in the form of discrimination or racism has been associated with suicidal ideation in older Chinese American adults,64 and with depressive symptoms in older African American adults.65 Additional research has shown that perceived racism may lead to health disparities for older racially minoritized adults, including delayed and forgone care.66 Furthermore, structural racism has certainly contributed to racial and/or ethnic disparities experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults who are members of historically marginalized communities.67 One need look no further than Medicare data to see how being a member of a historically marginalized community leads to poor health outcomes.68 The authors of a 2021 Kaiser Family Foundation Report, “Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities and Medicare,” noted that Black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries have fewer years of formal education and lower median per capita income, savings, and home equity than White beneficiaries.69 They also noted that among Medicare beneficiaries, people of color are more likely to report being in relatively poor health and have higher prevalence rates of some chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, than White beneficiaries. People of color are also less likely to have one or more doctor visits, but they have higher rates of hospital admissions and emergency department visits than White Medicare beneficiaries. These findings from the Kaiser report illustrate that the intersection of these constructs has long-term and lasting consequences. Work must be done to address these significant contributors to health disparities seen in and experienced by historically marginalized older adults.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

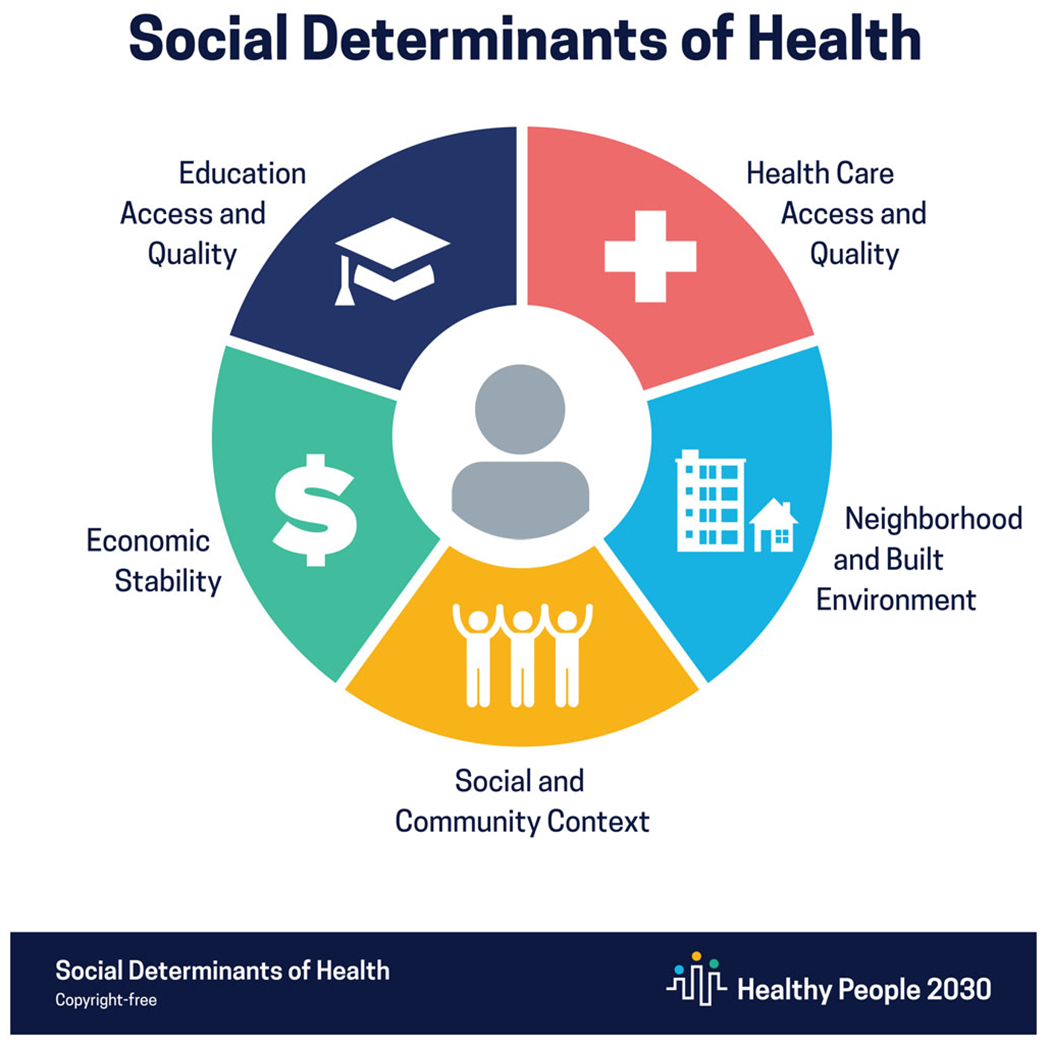

Social determinants of health are the conditions in the places where people are born, live, work, learn, and age that influence health, quality of life, and health outcomes (Figure 2).70–72 Social determinants of health that are driven by ageism and racism act synergistically to increase risk of poor outcomes in older adults. Social determinants, including inequality and injustice, create pathways through their interactions with biological processes in individuals and populations that result in greater disease burden and increased risk of poor health and well-being, referred to as the syndemics model of health.73 A striking and timely illustration of the syndemics model of health is in the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 among older adults; people of color; persons working in high-risk, high-contact occupations with few liberties to socially isolate; and individuals living in nursing homes or long-term care facilities.74–76

FIGURE 2.

Social determinants of health

Disadvantages in intergenerational transfer of wealth, home ownership, earning power, social mobility, access to high-quality education, and housing and transportation, result in less savings and greater housing and financial instability among older Latino and African American adults than among older White adults.34,77 In addition, older Asian adults from different subgroups (e.g., Cambodian, Bangladeshi, Korean), particularly more recent immigrants to the US, experience income and wealth inequality and limited access to resources that support aging in place.34,70 These vulnerabilities result from long-standing discriminatory policies and practices that impede the ability of older adults of color to withstand the financial impact of health problems and associated healthcare costs in their retirement years.78 Furthermore, patients’ experiences of racism and implicit bias have direct effects on the quality and outcomes of healthcare. For example, persons of color and those with limited English proficiency report less satisfaction with care, less involvement in patient-centered care and decision-making, and poorer communication with clinicians.79,80 Despite strong evidence implicating the causative roles of social and structural inequities on poor health outcomes among marginalized populations of older adults, there is a paucity of gerontology literature focused on structural and system-level determinants that examines the intersection of race and age. For example, little is known about the role of resilience among aging adults from diverse racial and/or ethnic groups recovering from aging-related illness and disability.81 System-level changes, including shifts to value-based payments, need to incorporate a health equity lens. In addition, a focus on individual and population health metrics to address upstream social determinants of health is imperative to reduce the impact of health-related social risk factors.82

THREE OF THE FUNDAMENTAL CHANGES NEEDED TO REALIZE THE PROMISE OF A JUST HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

To realize the promise of a just healthcare system in which being part of one or more groups does not affect the quality of care that is delivered, three fundamental changes must occur. First, the healthcare workforce must both reflect and be better prepared to care for the populations that it serves. The lack of representation of people from racially minoritized groups across the health professions must be addressed. In medicine, as an example, only 6.2% of medical students graduating in the academic year 2018–2019 were African American,9 even though African Americans comprised 13.4% of the US population in 2019.83 A similar percentage of incoming geriatric medicine fellows from internal medicine (9%) and family medicine (6%) residency programs are Black.84 Similarly, in nursing, 80.8% of registered nurses are White/Caucasian and 19.2% are from minority backgrounds. Only 6.2% of registered nurses are African American.85 There has been evidence of progress in pharmacy with respect to increasing representation of people from racially minoritized groups. According to a recent report, the percentage of non-White licensed pharmacists increased from 14.9% in 2014 to 21.8% in 2019, and the percentage of Black American pharmacists increased from 2.3% to 4.9% in the same time period.86

Second, how we train and support the next generation of health professionals must change so that we are truly supporting trainees from diverse backgrounds to achieve success in their chosen careers. The AGS, as an example, has advocated for changes in the definition of professionalism in medicine, calling for including explicit reference to ensuring that physicians are competent in justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion and actively working to eliminate discrimination and bias such as ageism, ableism, classism, homophobia, racism, sexism, and xenophobia in healthcare.87 The AGS has also advocated for supporting the direct care workforce—the backbone of our health and long-term care system—which mostly comprises women and people of color.88 It is imperative that we invest in the infrastructure needed to care for us all (including the workforce) as we age, to ensure a living wage and benefits, to strengthen training requirements and opportunities, and to provide opportunities for educational and career advancements.89 It is critically important that we incorporate the principles of health equity, geriatrics, and cultural competence into training of health professionals and that our current faculty receive the training they need to support the next generation.

Third, all aspects of healthcare must be examined from the perspective of the intersection of ageism, not only with racism, but also with other biases (e.g., ableism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia). Efforts to include diverse voices in determining healthcare policy and establishing mechanisms through which current and future policies are examined for their effects on building a just healthcare system are important steps. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force plans to address systemic racism by ensuring that its guidelines attempt to reduce health disparities, work that would be strengthened by ensuring intersectionality is addressed in its recommendations.89,90

CONCLUSION

The intersection of structural racism and ageism compounds the disadvantage experienced by historically marginalized communities. This intersection exacerbates disparities in social determinants of health, including poor access to healthcare and poor outcomes. The AGS is committed to the principles of a just healthcare system to eliminate such disparities.

The AGS believes that it is important for AGS members and others to understand the history of structural racism in the US and its impact on healthcare, the impact of ageism on the care that we all receive as we age, and the intersectionality of these two concepts. We recognize that this article provides the briefest of overviews on these important topics, and we are committed to continuing to learn and work together to achieve meaningful and lasting change.

In our future work, we will describe ethical and legal considerations related to the intersection of structural racism and ageism, as well as related health policy approaches needed to realize the vision of a just US healthcare system.

Key points

Structural racism and ageism have long been ingrained in all aspects of US society, including healthcare, exacerbating disparities in social determinants of health, including poor access to healthcare and poor outcomes.

The constructs of racism and ageism can have negative effects on health outcomes that can be magnified when race and age intersect.

Fundamental changes need to realize the promise of a just healthcare system include increased representation of people from racially minoritized groups in the healthcare workforce, support for trainees from diverse backgrounds to achieve success in their chosen careers, and inclusion of diverse voices in healthcare policy discussions.

Why does this paper matter?

The overview of frameworks and guidance for future efforts to both identify and eliminate bias within healthcare delivery systems and health professions training with a particular focus on the intersection of structural racism and ageism may lead to a more just healthcare system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Mary Jordan Samuel for her assistance with manuscript preparation and Geneva Hargis for her assistance with graphic design. The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the AGS Executive Committee for their critical review of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Dr. Nápoles’ contribution was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jih received funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award number KL2 TR001870) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (award number K23 MD015089).

Funding information

Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: KL2 TR001870; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: K23 MD015089

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nápoles-Springer A, Santoyo-Olsson J, O’Brien H, Stewart AL. Using cognitive interviews to develop surveys in diverse populations. Med Care. 2006;44(11):S21–S30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41219501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee FC, Adams L, Graves SJ, et al. Counties with jigh COVID-19 incidence and relatively large racial and ethnic minority populations – United States, April 1-December 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):483–489. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.We denounce race-related violence & will speak out against discriminatory policies, say leaders in geriatrics at AGS. News Release. American Geriatrics Society; June 2, 2020. Accessed Jan 5, 2022. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/media-center/news/we-denounce-race-related-violence-will-speak-out-against-discriminatory-policies [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mission and Vision. Accessed Febraury 2, 2022. American Geriatrics Society. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/about-us/mission-vision [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lundebjerg NE, Medina-Walpole AM. Future forward: AGS initiative addressing intersection of structural racism and ageism in health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(4):892–895. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Medical Association Manual of Style Committee. AMA Manual of Style: A Guide for Authors and Editors. 11th ed. Oxford University Press. 2020. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.amamanualofstyle.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ndugga N, Artiga S. Disparities in Health and Health Care: 5 Key Questions and Answers. 2021; Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-5-key-question-and-answers/

- 8.Klasa K, Galaitsi S, Wister A, Linkov I. System models for resilience in gerontology: application to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(51):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01965-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges Updated August 19, 2019. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-13-percentage-us-medical-school-graduates-race/ethnicity-alone-academic-year-2018-2019

- 10.Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1125–1128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelnick LR, Leca N, Young B, Bansal N. Association of the estimated glomerular filtration rate with vs. without a coefficient for race with time to eligibility for kidney transplant. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun L Race correction and spirometry: why history matters. Chest. 2021;159(4):1670–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaffney AW, McCormick D, Woolhandler S, Christiani DC, Himmelstein DU. Prognostic implications of differences in forced vital capacity in black and white US adults: findings from NHANES III with long-term mortality follow-up. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2477–2478. Erratum in N Engl J Med. 2021; 385 (26):2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMx210003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu J, Bartels CM, Rovin RA, Lamb LE, Kind AJH, Nerenz DR. Race, ethnicity, neighborhood characteristics, and in-hospital coronavirus disease-2019 mortality. Med Care. 2021;59(10):888–892. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The age-friendly health system imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):22–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabowski DC. Response to the commentary: the intersections of structural racism and ageism in the time of COVID-19: racism and ageism help explain underinvestment in long-term care: an important call to action. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2022;15(1): 14–15. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20211209-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson-Lane SG, Block L, Bowers BJ, Cacchione PZ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A. The intersections of structural racism and ageism in the time of COVID-19: a call to action for gerontological nursing science. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2022;15(1):6–13. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20211209-03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendi IX. How to be an Antiracist. One World; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):1–48. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1):S15–S27. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. 2019;7(64):1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.What is structural racism? American Medical Association. November 9, 2021. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/what-structural-racism

- 25.Smith DB. Racial and ethnic health disparities and the unfinished civil rights agenda. Health Aff. 2005;24(2):317–324. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works – racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothstein R The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of how our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing Corporation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35:80–94. doi: 10.2307/2626958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, Levin B. “fundamental causes” of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):265–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1):S28–S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow-Howell N, Galucia N, Swinford E. Recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on older adults. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4–5):526–535. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1759758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mobasseri K, Azami-Aghdash S, Khanijahani A, Khodayari-Zarnaq R. The main issues and challenges older adults face in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a scoping review of literature. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49(12):2295–2307. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v49i12.4810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villa S, Jaramillo E, Mangioni D, Bandera A, Gori A, Raviglione MC. Stigma at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(11):1450–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Gee GC, Bahiru E, Yang EH, Hsu JJ. Asian-Americans and Pacific islanders in COVID-19: emerging disparities amid discrimination. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12): 3685–3688. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06264-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Munana C, Brodie M. COVID-19 vaccine monitor: December 2020. December 15, 2020. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/

- 36.Kane RL, Kane RA. Ageism in healthcare and long-term care. Generations. 2005;29(3):49–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26555410 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen JO, Solway E, Kirch M, et al. Experiences of everyday ageism and the health of older US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):1–13. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.17240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization Global Report on Ageism. World Health Organization; 2021. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016866 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cherubini A, Del Signore S, Ouslander J, Semla T, Michel JP. Fighting against age discrimination in clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1791–1796. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nascher IL. Geriatrics. NY Med J. 1909;90:358–359. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nascher IL. Geriatrics: the Diseases of Old Age and their Treatment. Arno Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Census Bureau. The Older Population in the United States: 2019. US Census Bureau; 2019. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/age-and-sex/2019-older-population.html [Google Scholar]

- 43.Partnership for Health in Aging. Multidisciplinary competencies in the care of older adults at the completion of the entry-level health professional degree. American Geriatrics Society; 2008. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Multidisciplinary_Competencies_Partnership_HealthinAging_2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 44.Common Program Requirements. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements

- 45.Foley KT, Luz CC. Retooling the health care workforce for an aging america: a current perspective. Gerontologist. 2021;61(4):487–496. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. 2021. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf

- 47.Diachun L, Van Bussel L, Hansen KT, Charise A, Rieder MJ. “but I see old people everywhere”: dispelling the myth that eldercare is learned in nongeriatric clerkships. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1221–1228. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e0054f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hurria A, High KP, Mody L, et al. Aging, the medical subspecialties, and career development: where we were, where we are going. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(4):680–687. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee AG, Burton JA, Lundebjerg NE. Geriatrics-for-specialists initiative: an eleven-specialty collaboration to improve care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(10):2140–2145. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cox C Older adults and COVID-19: social justice, disparities, and social work practice. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2020;63(6–7):611–624. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2020.1808141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knodel J Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick suggests he, other seniors willing to die to get economy going again. NBC News. 2020. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/texas-lt-gov-dan-patrick-suggests-he-other-seniors-willing-n1167341 [Google Scholar]

- 52.OCR resolves complaint with Utah after it revised crisis standards of care to protect against age and disability discrimination. News Release. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. August 20, 2020. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/08/20/ocr-resolves-complaint-with-utah-after-revised-crisis-standards-of-care-to-protect-against-age-disability-discrimination.html [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farrell TW, Francis L, Brown T, et al. Rationing limited healthcare resources in the COVID-19 era and beyond: ethical considerations regarding older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6): 1143–1149. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kotwal AA, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark RL, et al. Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco bay area older adults during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):20–29. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Major AB, Naik AD, Farrell TW. Finding a voice for the accidentally unbefriended. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(9):1159–1160. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dictionary of Merriam-Webster. Intersectionality. Merriam-Webster. Updated August 18, 2022. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/intersectionality [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crenshaw K Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;1(8):139–168. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carbado DW, Crenshaw KW, Mays VM, Tomlinson B. INTERSECTIONALITY mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Rev. 2013;10(2):303–312. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X13000349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carreon D, Noymer A. Health-related quality of life in older adults: testing the double jeopardy hypothesis. J Aging Stud. 2011;25(4):371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chatters LM, Taylor HO, Taylor RJ. Older black Americans during COVID-19: race and age double jeopardy. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(6):855–860. doi: 10.1177/1090198120965513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferraro KF, Shippee TP. Aging and cumulative inequality: how does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist. 2009;49(3): 333–343. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5): 826–833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Geronimus AT. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethn Dis. 1992;2(3):207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li LW, Gee GC, Dong X. Association of self-reported discrimination and suicide ideation in older Chinese Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(1):42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nadimpalli SB, James BD, Yu L, Cothran F, Barnes LL. The association between discrimination and depressive symptoms among older African Americans: the role of psychological and social factors. Exp Aging Res. 2015;41(1):1–24. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2015.978201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhee TG, Marottoli RA, Van Ness PH, Levy BR. Impact of perceived racism on healthcare access among older minority adults. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(4):580–585. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garcia MA, Homan PA, Garcia C, Brown TH. The color of COVID-19: structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older black and Latinx adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(3):e75–e80. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ng JH, Bierman AS, Elliott MN, Wilson RL, Xia C, Scholle SH. Beyond black and white: race/ethnicity and health status among older adults. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(3):239–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ochieng N, Cubanski J, Neuman T, Artiga S, Damico A. Racial and ethnic health inequities and Medicare. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/racial-and-ethnic-health-inequities-and-medicare [Google Scholar]

- 70.Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed August 25, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health [Google Scholar]

- 71.Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health

- 72.Social determinants of health: know what affects health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 30, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm

- 73.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):941–950. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.COVID-19 risks and vaccine information for older adults. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 4, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html

- 75.Devakumar D, Shannon G, Bhopal SS, Abubakar I. Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yaya S, Yeboah H, Charles CH, Otu A, Labonte R. Ethnic and racial disparities in COVID-19-related deaths: counting the trees, hiding the forest. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(6):1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ong PM, Pech C, Cheng A. Wealth heterogeneity among Asian American elderly. AAPR. 2017;27:15–32. https://aapr.hkspublications.org/2017/06/26/wealthheterogeneity/ [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koma W, Biniek JF, Ochleng N, Neuman T, Smith K. Does Education Narrow the Gap in Wealth among Older Adults, by Race and Ethnicity? Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/does-education-narrow-the-gap-in-wealth-among-older-adults-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nápoles AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J, O’Brien H, Stewart AL. Interpersonal processes of care and patient satisfaction: do associations differ by race, ethnicity, and language? Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1326–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00965.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the nation’s Health. 2019. Accessed September 13, 2022. 10.17226/25467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts United States. U.S. Census Bureau; 2021. Accessed Febraury 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019, percentage of U.S. medical school graduate by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018–2019. Association of American Medical Colleges. Updated August 19, 2019. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-13-percentage-us-medical-school-graduates-race/ethnicity-alone-academic-year-2018-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smiley RA, Lauer P, Bienemy C, et al. The 2017 national nursing workforce survey. J Nurs Regul. 2018;9(3):S1–S88. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(18)30131-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arya V, Bakken BK, Doucette WR, et al. National pharmacist workforce study 2019. 2020. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/2019_NPWS_Final_Report.pdf

- 86.Comments from the American Geriatrics Society on the ABMS draft standards for continuing certification. American Geriatrics Society; 2021. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/AGS%20Comments%20on%20ABMS%20Draft%20Standards%20for%20Continuing%20Certification.final_.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 87.PHI. Direct care workers in the United States: key facts. 2021. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://phinational.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Direct-Care-Workers-in-the-US-2021-PHI.pdf

- 88.Letter to the COVID-19 health equity task force on pandemic preparedness. American Geriatrics Society; 2021. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/American%20Geriatrics%20Society%20follow%20up%20to%20COVID%2019%20Equity%20Task%20Force%20Presentation%20FINAL%20%288%202%2021%29.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 89.Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. Actions to transform US preventive services task force methods to mitigate systemic racism in clinical preventive services. JAMA. 2021;326(23):2405–2411. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin JS, Hoffman L, Bean SI, et al. Addressing racism in preventive services: methods report to support the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2021;326(23):2412–2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]