Abstract

Theory and research point to the daily interactions between individual children and teachers as formative to teacher-child relationships, yet observed dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool classrooms have largely been overlooked. This study provides a descriptive examination of the quality of individual children’s interactions with their teacher as a basis for understanding one source of information theorized to inform children’s and teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with each other. Children’s dyadic interactions with teachers, including their positive engagement, communication, and conflict, were observed across a large and racially/ethnically diverse sample of 767 preschool children (M = 4.39 years) at three time points in the year. On average, most children displayed low-to-moderate levels of positive engagement (78%), while nearly all children showed rare communication (81%) and conflict (99%) with the teacher. Boys demonstrated lower positive engagement and higher conflict with the teacher than girls. Black children were observed to demonstrate higher positive engagement with the teacher compared to White children. No differences in interaction quality were observed for Black children with a White teacher compared to White child-White teacher or Black child-Black teacher pairs. Results advance our understanding of dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool classrooms and raise new questions to expand our knowledge of how teacher-child relationships are established, maintained, and modified, to ultimately support teachers in building strong relationships with each and every preschooler.

Keywords: teacher-child relationships, teacher-child interactions, preschool, gender, race/ethnicity, teacher-child racial/ethnic match

Children interact with their teachers on a near daily basis, and over time these dyadic teacher-child interactions become patterned and form a relationship (Pianta, 1999). High-quality relationships are typically operationalized in terms of teachers’ perceptions of high relational closeness—such as positive affect, connection, and child’s comfort initiating and communicating with the teacher—and limited relational conflict, such as negativity or difficulty (Sabol & Pianta, 2012). The relational quality a child shares with their teacher is consequential, as high-quality relationships promote children’s academic and behavioral competence (e.g., Iruka, Curenton, Sims, et al., 2020; Maldonado-Carreño & Votruba-Drzal, 2011) while conflictual relationships undermine these developmental outcomes (e.g., Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Lippard et al., 2018; Pakarinen et al., 2021). Strong and positive teacher-child relationships are an especially valuable resource for racially minoritized children and children from low-income backgrounds (Burchinal et al., 2002; Liew et al., 2010; McCormick et al., 2017; Meehan et al., 2003), because these children face a host of structural and interpersonal barriers (Logan et al., 2012; Iruka, Curenton, Durden, et al., 2020) that a high-quality relationship with a teacher can help alleviate.

Much research on the contributors to relationship quality has examined the role of child sociodemographic characteristics, revealing troubling disparities in relationship quality for boys and Black children (Ewing & Taylor, 2009; Horn et al., 2021; Murray & Murray, 2004). Some studies have also reported that teacher characteristics, particularly self-efficacy beliefs and depression, contribute to teacher-child relationship quality (Hajovsky et al., 2020; Hamre et al., 2008). In addition to child and teacher characteristics, theory (Pianta et al., 2003) and some empirical work (Hartz et al., 2017; Rudasill, 2011) indicate that the back-and-forth exchanges between a teacher and child are equally—if not more—important for understanding how relationships develop. As children and teachers interact, they exchange salient information that informs each individual’s perception of the other; these perceptions become more stable over time and eventually codify into a relationship. Despite their theoretical importance to understanding how relationships between children and teachers develop, a large-scale descriptive study of observed interactions between individual children and teachers is lacking in the literature (Vershueren & Koomen, 2012), in part due to challenges in obtaining observational data at the child level. In the present study, we sought to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive picture of these interactions as they naturally occur in preschool classrooms serving racially/ethnically diverse children from low-income households. Specifically, we examined the average quality of dyadic teacher-child interactions and the extent to which individual children’s interactions with the teacher vary within and between classrooms. Based on knowledge that child gender, child race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match contribute to teacher-child relationship quality, we also explored whether observed interactions vary by these same factors. While teacher characteristics are also important for understanding dyadic interactions, in the current study we intentionally focus on children’s gender, race/ethnicity, and their racial/ethnic match with teachers because these sociodemographic characteristics—due to social stratification—create different opportunities, resources, and barriers for children’s engagement in the classroom (Wang et al., 2019).

Conceptual Model of Teacher-Child Relationships

Our conceptualization of teacher-child relationships is directly informed by Pianta and colleagues (2003). Drawing from attachment theory (Bowlby, 1973) and a developmental systems theoretical perspective (Lerner, 1998), they assert that teacher-child relationships are dynamic systems made up of multiple components including characteristics of the child and the teacher, the reciprocal interactions and communications through which information is exchanged between the child and teacher, and features of the classrooms, schools, and communities in which the relationship exists. Central to this model are the daily reciprocal interactions between a child and teacher, as it is through these interactions that each individual’s representation of the teacher-child relationship is established, modified, and maintained via the exchange of information. Early interaction patterns inform young children’s internal working models of their relationships with teachers that carry over, via a “feedforward” loop, into future relationships with teachers (O’Connor, 2010; Verschueren & Koomen, 2012). Thus, a rich understanding of dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool classrooms is highly needed, as these early interactions can promote or hinder the way in which children and teachers view and approach each other throughout elementary school and beyond.

Observed Teacher-Child Interactions and Relationship Quality

Empirical work shows that the observed quality of children’s interactions with their teacher contributes to teachers’ perceptions of their relationship quality with children, lending support to the conceptual idea that teacher-child interactions help to establish and maintain teacher-child relationships. For example, among a sample of low-income preschoolers, teachers reported greater gains in their perceptions of relational closeness with children observed to interact positively with the teacher (Hartz et al., 2017). Additionally, across the preschool year, teachers perceived increased relational conflict with children observed to interact negatively in the classroom. Further evidence from prevention and intervention work in preschool and elementary classrooms indicates that targeting teacher-child interactions is an effective means to improve teacher-child relationships (Kincade et al., 2020). For example, teacher-child relationship interventions seek to change teacher interactive behaviors through activities such as tracking the ratio of positive to negative interactions (Cook et al., 2018) or coaching teachers to use specific practices when interacting with a child (e.g., praise; Sutherland et al., 2018). Other teacher-child relationship interventions support teachers to engage in child-driven, one-on-one interactions with a child (Driscoll & Pianta, 2010; Vancraeyveldt et al., 2015; Williford et al., 2017) or to increase affiliation and reduce control in dyadic teacher-child interactions (Roorda et al., 2013). Experimental evaluations of these interventions show positive impacts on relationship quality as reported by teachers (Cook et al., 2018, Driscoll & Pianta, 2010; Sutherland et al., 2018; Vancraeyveldt et al., 2015).

These studies provide an empirical link between observed teacher-child interactions and relationship quality. To extend this literature, more can be learned about what dyadic interactions look like in preschool classrooms and the extent to which variability in the quality of dyadic interactions maps onto differences in teacher-child relationship quality along the lines of child and dyadic characteristics. Research shows that individual children have diverse experiences interacting with the same teacher (e.g., Dobbs & Arnold, 2009; Smidt & Rossbach, 2016), and that dyadic interactions with teachers are of moderate to poor quality overall (Franco et al., 2019; Guedes et al., 2020; Hallam et al., 2016; Jeon et al., 2010; Williford et al., 2013). Less is known about how child gender, child race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match contribute to teacher-child interaction quality, although these factors have been linked extensively to teacher-child relationship quality.

Child Gender, Child Race/Ethnicity, and Teacher-Child Racial/Ethnic Match Predicting Dyadic Teacher-Child Relationships and Interactions

Ample research indicates that teachers perceive relationships differently with children depending on sociodemographic characteristics of the child, yet it is unclear if children interact with their teacher differently depending on these same characteristics. For instance, teachers perceive having closer relationships with girls than boys (Baker, 2006; Choi & Dobbs-Oates, 2016; Ewing & Taylor, 2009; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Jerome et al., 2009; Silver et al., 2005), and teachers’ perceived closeness with boys may decline over the first two years of school (Horn et al., 2021). Boys are also more likely to be perceived as having conflictual relationships with teachers (Baker, 2006; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Hajovsky et al., 2017; Jerome et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2008; Silver et al., 2005), regardless of whether the teacher is female or male (Spilt et al., 2012). Although these gender disparities in teacher reports of relationship quality are well-documented, it is unclear whether boys and girls are observed to actually interact differently with their teacher during typical classroom activities. Two prior studies that measured dyadic interactions using the same observational tool as the current study found few to no gender differences in preschool children’s one-on-one interactions with their teacher (Booren et al., 2012; Vitiello et al., 2012). This prior work was based on a limited number of observation cycles conducted for each child (4–8 cycles), and the samples were smaller and, in one case, racially/ethnically homogenous. The present study extends these descriptive findings by including a larger number of observation cycles per child (18)—thus better representing children’s experiences in the preschool classroom—and a larger, more racially-ethnically diverse preschool sample.

Likewise, research has examined how teachers’ perceptions of relationship quality vary based on the child’s race/ethnicity and the match or mismatch between the teacher and child’s race/ethnicity. For example, teachers of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds perceive poorer quality relationships with Black children compared to White children (Gallagher et al., 2013; Loomis, 2021; Murray & Murray, 2004; O’Connor, 2010; Saft & Pianta, 2001), with some evidence that this gap widens over time (Jerome et al., 2009). However, when teachers identify as the same race/ethnicity as the child, racial disparities in relationship quality can narrow (Saft & Pianta, 2001), suggesting that the racial/ethnic match between a teacher and child contributes to teachers’ perceptions of relational quality (Ho et al., 2012). Notably, other studies have found no differences between teacher-reported conflict for Black compared to White children (Hamre et al., 2008) nor any evidence to suggest that racial/ethnic match with the teacher is linked to greater relationship quality (Choi & Dobbs-Oates, 2016). As with child gender, there is limited research on whether children’s race/ethnicity matters for how children interact with their teacher; however, some research indicates that children interact with teachers similarly regardless of whether the teacher is the same race/ethnicity as the child, whereas teachers exhibit more racial bias in their interactions with children. For instance, teachers respond more negatively to a behavior displayed by a child from a different racial/ethnic background compared to the same behavior displayed by a child from their same racial/ethnic background (Ho et al., 2012).

Present Study

The present study provides an in-depth examination of children’s dyadic interaction quality with their teachers in preschool classrooms. Two research questions are addressed: (1) What does the quality of children’s interactions with teachers look like on average, as well as across and within classrooms? (2) After accounting for key covariates theoretically or empirically linked to dyadic teacher-child relational processes, including child age in months; child incoming school readiness skills; family income-to-needs; teacher emotional support; classroom size; and classroom-averaged income-to-needs (e.g., Bosman et al., 2018; Choi & Dobbs-Oates, 2016; Hartz et al., 2017; Howes et al., 2013; Trang & Hansen, 2020), to what extent does child gender, child race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match explain variability in observed dyadic interaction quality? In line with previous research, we hypothesized that children’s dyadic interactions with teachers would be of poor to moderate quality on average (Jeon et al., 2010; Williford et al., 2013) but variable both within and across classrooms. Further, our hypotheses regarding the links between child gender, child race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match and observed interaction quality with teachers were based on the theoretical assumption that patterns of dyadic interactions inform teachers’ perceived relational quality with children. Thus, based on evidence that teachers perceive lower-quality relationships with boys (Ewing & Taylor, 2009; Spilt et al., 2012) and Black children (Loomis, 2021; Murray & Murray, 2004; O’Connor, 2010), we hypothesized that similar disparities would be observed for the quality of dyadic interactions. Due to the mixed evidence on whether teachers’ perceptions of relationship quality vary based on the racial/ethnic match with a child, we did not have a strong hypothesis on how racial/ethnic match might contribute to dyadic interaction quality and consider our analyses addressing this question to be exploratory.

This study extends the literature on dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool classrooms in two important ways. First, the study is unique in its focus on children’s individual experiences interacting with their teacher. Prior studies investigating individual children’s observed classroom experiences (Early et al., 2010; Jeon et al., 2010; Pelatti et al., 2014; Smidt & Rossbach, 2016) examined a broad set of classroom experiences, including children’s learning opportunities and engagement with learning activities. By attending exclusively to children’s observed interactions with teachers, this study provides a more specific descriptive picture of a classroom process theorized to underlie teacher-child relationships. Second, the current study provides this descriptive look at individual children’s interactions with teachers using a larger and more racially/ethnically diverse sample of preschoolers than prior work, enabling us to not only understand the overall nature of dyadic teacher-child interactions, but how they vary by child gender, child race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match, after accounting for key covariates. These differences are well-documented for teacher-child relationships, but not for dyadic teacher-child interactions despite them being a key process by which teacher-child relationships are theorized to develop. Taken together, findings from this study contribute a more detailed picture of preschool children’s experiences with their teacher and have implications for further understanding disparities in teacher-child relationships based on child gender, child race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match.

Method

Participants

Data were collected as part of a staged, two-cohort observational study of children’s classroom experiences from preschool through kindergarten. The observational study targeted preschool programs serving children from low-income households (family income at or below 200% of the federal poverty guidelines, family homelessness, or parents/guardians lack high school diploma) in two sites within one southeastern state in the United States. Within the 17 participating programs, teachers were randomly selected for inclusion in the study among all consented teachers (50 out of 67 in cohort one, all 51 consented teachers in cohort two). All children in a classroom taught by participating teachers were eligible for the study. Classrooms were a mixed of federal/Head Start (n = 10), state (n = 84), and privately funded, non-profit (n = 12). An average of eight consented children per classroom (M = 7.69, SD = 1.15) were randomly selected for participation, after blocking by gender. All children (N = 767) and teachers (N = 106)1 across participating classrooms (N = 106) were part of the present study.

Based upon caregiver report, children were 4 years old on average (M = 4.39, SD = 0.08), half were girls (49%) and half boys (51%), and their racial/ethnic composition was identified as: 50% Black/African American, 22% White/Caucasian, 13% Hispanic/Latino, and 15% Other race/ethnicity (includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and Multiracial). On average, children’s mothers had 13 years of education (M = 13.41, SD = 1.85), the average income-to-needs ratio of the family was 1.45 (SD = 1.06), and 75% of children’s families were considered to have low incomes (i.e., income-to-needs ratio less than 2).

Teachers were 43 years old on average (M = 43.25, SD = 11.23), nearly all were female (98%), and their racial/ethnic composition was: 65% White/Caucasian, 30% Black/African American, 3% Hispanic/Latino, 2% Multiracial. On average, teachers had 15 years of teaching experience (M = 15.14, SD = 8.61), had worked at their current facility for seven years (M = 7.48, SD = 5.66), and half of them (50%) had a master’s degree.

Procedures

Recruitment of Preschool Programs and Participants

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Preschool program administrators were contacted to participate in the study. Following program approval, researchers met with teachers to obtain informed consent. Parents/guardians of all children in participating classrooms were given a letter explaining the study, a consent form, and a family demographic survey. Parents/guardians could complete the survey online (Qualtrics), mail it to researchers, or return it to their child’s teachers. The response rate for the survey was 99% for parents who completed a consent form in each cohort. All families who returned a consent form and survey—regardless of whether their child was selected for participation—received a small honorarium and their child received a book.

Data Collection

Data collection took place between the years 2016–2018 for cohort one (380 children, 53 teachers, 51 classrooms) and 2018–2020 for cohort 2 (387 children, 56 teachers, 55 classrooms). Relevant to the present study, preschool data collection occurred during the 2016–2017 and 2018–2019 academic years for cohorts one and two, respectively. Data were collected at three time points during the preschool academic year: fall, winter, and spring. Teachers and parents/guardians completed demographic surveys at the beginning of the academic year (fall). Classroom observations and direct assessments of children were collected at all three time points (fall, winter, and spring). Teachers completed ratings of children’s behaviors, classroom practices, and their wellbeing at the beginning and end of the academic year (fall and spring).

Observation Training and Protocol

All data collectors attended a two-day training for each of the two observational measures: (1) a child-level measure of children’s classroom engagement (i.e., inCLASS), of interest to the present study (see Measures section for more details), and (2) a classroom-level measure of classroom quality (i.e., CLASS). The training was comprised of a detailed review of all the dimensions of each measure, along with watching, coding, and discussing five training clips. To be considered a reliable observer, and able to conduct live classroom observations, data collectors had to code five reliability clips independently (without discussion) and score within one point of a master code on 80% of the dimensions. During data collection, observers were required to participate in calibration sessions every other month. These sessions consisted of observers viewing and coding a video independently for each measure, submitting their codes, participating in an online meeting and discussion about the master codes and justifications with a certified trainer, and submitting a reflection to the trainer for additional feedback and support.

The live classroom observation protocol consisted of data collectors spending one or two days in a classroom. Each day, data collectors observed individual children (inCLASS) and their classroom (CLASS) in a series of alternating cycles: a 15-minute cycle for the inCLASS (10 minutes to observe, 5 minutes to score) and a 25-minute cycle for the CLASS (15 minutes to observe, 10 minutes to score), shifting across all participating children in the classroom. The goal of the observation protocol was to complete six inCLASS observation cycles for each child and six CLASS observations. The same observation protocol was applied at each data collection time point, totaling 18 (M = 17.76, SD = 1.57) expected inCLASS observation cycles per child (i.e., six inCLASS cycles at each of the three data collection time points).

Measures

Individual Children’s Observed Interaction Quality with the Teacher

The Individualized Classroom Assessment Scoring System (inCLASS; Downer et al., 2010) was used to assess individual children’s observed interaction quality with the teacher. The inCLASS is an observational measure that captures 10 dimensions of children’s classroom engagement using a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (Low) to 7 (High): (1) positive engagement with teacher; (2) communication with teacher; (3) conflict with teacher; (4) sociability with peers; (5) conflict with peers; (6) assertiveness with peers; (7) communication with peers; (8) engagement with tasks; (9) self-reliance; and (10) behavior control. The inCLASS has shown construct and criterion validity (Downer et al., 2010), along with measurement invariance across gender, ethnicity, and poverty status (Bohlmann et al., 2019). Given conceptual alignment with our construct of interest, we used the three dimensions of the inCLASS that pertain to children’s interactions with the teacher (i.e., positive engagement, communication, and conflict with the teacher). Interrater reliability was calculated across 20% of all observations with two data collectors independently observing and rating the same classroom. The ICCs, estimated using a two-way random model of absolute agreement, were .70 for positive engagement with teacher, .75 for communication with teacher, and .58 for conflict with teacher, indicating moderate to good reliability.

Child and Teacher Sociodemographic Characteristics

Child and teachers sociodemographic characteristics of interest (gender and race/ethnicity) were collected via parent/guardian and teacher survey, respectively.

Covariates

Child covariates.

Child covariates theoretically or empirically linked to dyadic teacher-child interactions or relationships included: (1) child age and family income-to-needs (e.g., Bardack & Obradović, 2017; Garner & Mahatmya, 2015) and (2) child incoming school readiness skills (e.g., Bosman et al., 2018; Choi & Dobbs-Oates, 2016). Demographic covariates (age and family income) were collected via parent/guardian survey. Parent-reported income data were used to calculate income-to-needs ratio based upon published U.S. Census data poverty thresholds for the year the data were collected. School readiness skills were captured using a battery of direct assessments that have been widely used in national studies with preschoolers from low-income households. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) was used to assess children’s receptive language skills. The Picture Vocabulary and the Applied Problems and Quantitative Concepts subtests of the Woodcock Johnson-III (WJ-III; Woodcock et al., 2001) were used to capture children expressive language and math skills, respectively. Regarding regulatory skills, the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders (HTKS; McClelland et al., 2007; Ponitz et al., 2008) was used to capture children’s behavioral self-regulation, and the Pencil Tap subtest of the subtest of the Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment (PSRA; Smith-Donald et al., 2007) was utilized to assess children’s inhibitory control.

Teacher and classroom covariates.

Teacher and classroom covariates theoretically or empirically linked to dyadic teacher-child interactions or relationships included: (1) classroom size, program type, and average income-to-needs (e.g., Hartz et al., 2017; Trang & Hansen, 2020), along with (2) teacher observed emotional support (Hamre et al., 2008; Howes et al., 2013). Classroom covariates (size, program type) were collected via teacher survey. Child-level data were aggregated to the classroom-level using the mean to create the classroom income-to-needs covariate. Finally, observations of classroom-level emotional support were conducted using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), Pre-K version (Pianta et al., 2008). The CLASS is a classroom-level observational measure that captures 10 dimensions of classroom quality using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Low) to 7 (High): (1) positive climate; (2) negative climate; (3) teacher sensitivity; (4) regard for student perspectives; (5) behavior management; (6) productivity; (7) concept development; (8) instructional learning formats; (9) quality of feedback; and (10) language modeling. Previous factor analyses demonstrated that the data support three domains of classroom quality: emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support (Hamre et l., 2007). Numerous studies provide evidence for the construct and predictive validity of the CLASS (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2008). We used the emotional support domain as it is the most proximal to our constructs of interest. The internal consistency for emotional support was excellent—as measured by Cronbach alpha of .88—and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), calculated across the 20% of all observations that were double coded, was .73.

Data Analysis Plan

Descriptive Statistics

We computed descriptive statistics and variability plots using Stata version 14 to examine what individual children’s observed interaction quality with the teacher looked like in preschool classrooms. Ten preschoolers who did not have observational data were excluded, and thus the sample for the descriptive work consisted of 13,218 observation cycles and 757 children. Children who were excluded from descriptive analyses did not differ from their included peers in terms of gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income-to-needs ratio (t-tests, p-values >.05).

Predictive Models

Two models were estimated to explain variability in observed teacher-child dyadic interaction quality (children’s observed positive engagement, communication, and conflict with the teacher). Both models used the robust maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012–2019), modeled all three outcomes simultaneously to account for their shared variance, and included a robust set of child, classroom, and teacher covariates. Parent/guardian-reported child covariates included children’s income-to-needs ratio and age in months. Directly assessed child covariates included incoming school readiness skills: receptive language, expressive language, behavioral self-regulation, inhibitory control, and math reasoning. In addition, we controlled for teachers’ emotional support, classroom size, and classroom income-to-needs mean. We also controlled for whether the preschool program was administered by a public agency (public = 1; non-profit = 0), along with study cohort and site (both dummy coded). The multilevel nature of the data, children nested within classrooms, was accounted for by using type=complex, a command in Mplus that computes robust standard errors while clustering at the classroom level. Missing data ranged from 0 to 9% across study variables, no cases had missing data on all variables, and no systematic patterns of missingness were observed. As a result, we handled missing data using FIML under the assumption that data were missing at random.

Child gender and race/ethnicity.

We first tested whether children’s gender (boy = 1; girl = 0) and race/ethnicity (dummy codes for Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Other, with White as the reference group) explained their observed positive engagement, communication, and conflict with the teacher.

Teacher-child racial/ethnic match.

We then explored whether a child’s racial/ethnic match with the teacher explained their observed positive engagement, communication, and conflict with the teacher. To that end, we first created a match variable at the child-level (match = 1; mismatch = 0) in accordance with the coding approach used by Rasheed and colleagues (2020). As displayed in Table 1, 35% (n = 263) of children matched the race/ethnicity of their teacher. Second, we created a variable for each subgroup of teacher-child racial/ethnic match and mismatch at the child-level. Given five (Black, White, Hispanic/Latino, Multiracial, Other) and four (Black, White, Hispanic/Latino, Multiracial) race/ethnicity categories for child and teacher respectively, there were 20 potential combinations of racial/ethnic match and mismatch. Combinations were removed if they had too few cases or if they included Multiracial or Other to distinctly align or contrast teacher and child race/ethnicity (see Table 1), resulting in a final analytic sample that included 580 children and 96 teachers. The variables for teacher-child racial/ethnic match subgroups were used as the main predictors. Black children with White teachers was the largest subgroup in our sample (31%; n = 227) and was treated as the reference group.

Table 1.

Teacher-child racial/ethnic match and mismatch combinations

| Teacher race/ethnicity | Child race/ethnicity | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Racial/ethnic match | 263 | 35.40 | |

| Black | Black | 130 | 17.50 |

| Latino | Latino* | 9 | 1.21 |

| White | White | 121 | 16.29 |

| Multiracial | Multiracial* | 3 | 0.40 |

| Racial/ethnic mismatch | 480 | 64.60 | |

| Black | Latino* | 19 | 2.56 |

| Black | White | 37 | 4.98 |

| Black | Other* | 8 | 1.08 |

| Black | Multiracial* | 24 | 3.23 |

| Latino | Black* | 9 | 1.21 |

| Latino | White* | 5 | 0.67 |

| Latino | Other* | 1 | 0.13 |

| Latino | Multiracial* | 1 | 0.13 |

| White | Black | 227 | 30.55 |

| White | Latino | 65 | 8.75 |

| White | Other* | 17 | 2.29 |

| White | Multiracial* | 55 | 7.40 |

| Multiracial | Black* | 5 | 0.67 |

| Multiracial | Latino * | 3 | 0.40 |

| Multiracial | White* | 4 | 0.54 |

| Multiracial | Other* | 0 | 0.00 |

Note: Multiracial = two or more races; Latino = Hispanic/Latino of any race; White = White, non-Hispanic; Black = Black, non-Hispanic.

Excluded from the analytical sample for the teacher-child racial/ethnic match prediction model.

Results

Individual Children’s Observed Interactions with the Teacher

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for individual children’s observed interaction quality with the teacher by time point and averaged across all three time points, at both the cycle and the child levels. On average, children’s positive engagement, communication, and conflict with the teacher were relatively low and stable across time points. Given our conceptual interest in patterns of dyadic teacher-child interactive behaviors, along with their relative stability, we focus the description of results on children’s average scores across time points.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and quality frequency counts for individual children’s observed interaction quality with the teacher at the cycle and child levels, by time point and in total.

| Cycle level (N = 13,218) | Child-level average (n = 757) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall | Winter | Spring | Total | Fall | Winter | Spring | Total | |

|

| ||||||||

| Positive engagement with teacher | ||||||||

| M | 2.48 | 2.61 | 2.47 | 2.52 | 2.48 | 2.61 | 2.47 | 2.52 |

| SD | 1.36 | 1.46 | 1.44 | 1.42 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.66 |

| Min—Max | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–5.83 | 1–6.42 | 1–6 | 1.17–5.67 |

| Low | 57% | 54% | 58% | 56% | 36% | 29% | 36% | 22% |

| Mid | 40% | 41% | 38% | 39% | 64% | 71% | 64% | 78% |

| High | 3% | 5% | 4% | 4% | 0% | <1% | <1% | 0% |

| Communication with teacher | ||||||||

| M | 1.59 | 1.64 | 1.68 | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.64 | 1.67 | 1.64 |

| SD | 0.97 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.43 |

| Min—Max | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–4.25 | 1–5 | 1–5.67 | 1–3.58 |

| Low | 85% | 83% | 83% | 84% | 83% | 79% | 78% | 81% |

| Mid | 14% | 16% | 16% | 15% | 17% | 21% | 22% | 19% |

| High | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Conflict with teacher | ||||||||

| M | 1.08 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 |

| SD | 0.4 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.21 |

| Min—Max | 1–6 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–3.08 | 1–3.75 | 1–5.83 | 1–2.81 |

| Low | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 99% | 99% |

| Mid | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| High | <1% | <1% | <1% | <1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Note: Quality thresholds for positive engagement, communication, and conflict with the teacher were defined in accordance with the inCLASS measure: low (1–2), mid (3–5), and high (6–7). Percentages refer to percent of cycles (cycle-level) and children (child-level) within each quality range.

Cycle-Level

Across all three time points, cycle-level results indicated that children’s average positive engagement (M = 2.52), communication (M = 1.63), and conflict (M = 1.09) with the teacher were low, but substantial variation was found for positive engagement (SD = 1.42, range 1–7) and communication (SD = 1.03, range 1–7) across cycles. An average cycle could be described as a child showing few indications of being emotionally connected or having a conversation with the teacher, along with few examples of negative interactions between a child and the teacher (e.g., negative affect, aggression). Most observation cycles were characterized by low positive engagement (57%), communication (83%), and conflict (98%) between the child and the teacher. These data reveal that explicitly positive (i.e., positive engagement and communication) and negative (i.e., conflict) interactions between individual children and their teachers were rarely observed across these preschool classrooms.

Child-Level

When averaged across all cycles and the three time points, child-level results similarly indicate that children’s average positive engagement (M = 2.52) and communication (M = 1.64) with the teacher were predominantly low quality but evidenced little to no conflict (M = 1.09). Most individual children’s interaction quality with the teacher demonstrated some positive engagement (78%), as evidenced by most children’s average score falling into the lower end of the mid category, but nearly all children showed rare communication (81%) and conflict (99%) with the teacher on average. To determine the proportion of children observed to engage in high- or low-quality interactions with the teachers at least once, we examined each child’s range of scores across cycles (not shown in Table 2). Among the 757 children in the sample, 309 (41%) had at least one cycle of high positive engagement with the teacher (many indications of attunement, proximity seeking, or shared positive affect). A smaller number of children (n = 92; 12%) had at least one cycle of high communication with the teacher (child frequently initiating communication or sustained conversation). Among all children, 307 (41%) had at least one cycle engaging in some form of conflict with the teacher (i.e., conflict rated as two or higher).

Variability Across and Within Classrooms in Individual Children’s Observed Interactions with the Teacher

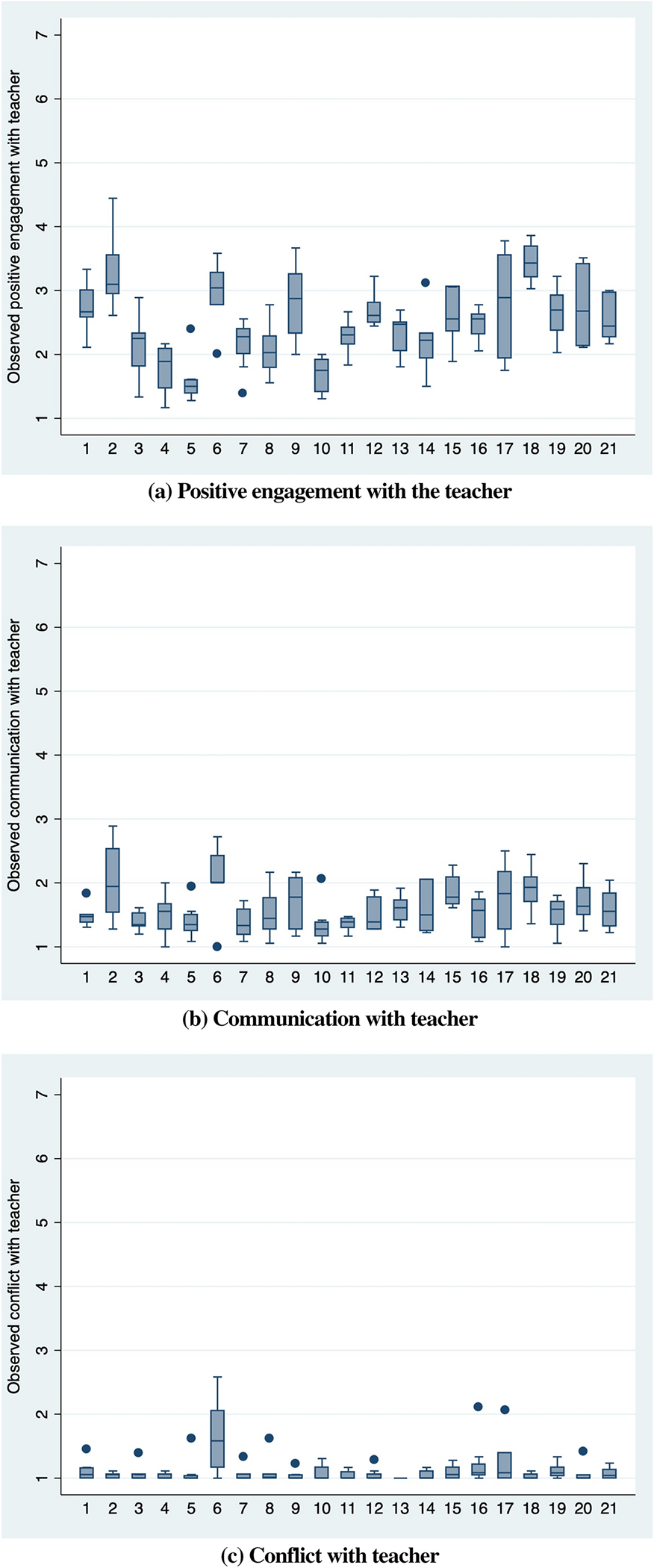

Within- and between-classroom variability of individual children’s average interactions with the teacher was examined for all classrooms in which seven or more children were observed (n = 85). The ICC was .46 for positive engagement with the teacher and .29 for communication with the teacher, indicating significant variation in individual children’s positive interactions with the teacher both within- and between-classrooms. The ICC for conflict with the teacher was .08, indicating that most variability in children’s conflict reflected differences between children within classrooms. Figure 1 displays these within- and between-classroom differences in individual children’s observed interaction quality with the teacher for a randomly selected set of 21 classrooms.

Figure 1.

Variability across 21 randomly selected classrooms for positive engagement with the teacher (a), communication with teacher (b), and conflict with teacher (c). This variability is based on a child’s average interaction quality with the teacher across all observation cycles.

Individual Children’s Observed Interactions with the Teacher as a Function of Children’s Gender and Race/Ethnicity

We tested whether boys and Black children were observed to interact less positively with the teacher when compared to girls and White children, respectively. Results for the model testing children’s gender and race/ethnicity as predictors of individual children’s observed interaction quality with the teacher are presented in Table 3. Regarding positive engagement with the teacher in the classroom, findings revealed significant, albeit small, associations. The results indicated that boys demonstrated lower positive engagement with the teacher (β = −0.14, SE = 0.03, p < .001) and higher conflict with the teacher (β = 0.13, SE = 0.04, p < .001) than girls. Additionally, Black children were observed to demonstrate higher positive engagement with the teacher compared to White children (β = 0.10, SE = 0.04, p < .05).

Table 3.

Associations between children’s gender and race/ethnicity and their average observed interaction quality with the teacher across the preschool year.

| Positive engagement with the teacher | Communication with the teacher | Conflict with the teacher | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | S. E. | p-value | Est. | S. E. | p-value | Est. | S. E. | p-value | |

|

| |||||||||

| Child gender | |||||||||

| Boy | −0.14 | 0.03 | <.001 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.04 | <.001 |

| Child race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Black | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.63 |

| Latino | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.93 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Other | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.30 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Child covariates | |||||||||

| Income-to-needs | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.14 |

| Age in months | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.29 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.53 |

| Receptive language | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.42 |

| Expressive language | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.70 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.60 |

| Behavioral self-regulation | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.61 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.39 |

| Inhibitory control | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.91 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.37 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Math reasoning, applied problems | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Math reasoning, quant. concepts | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.27 |

| Teacher/classroom covariates | |||||||||

| Ethnicity non-White | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.77 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.73 |

| Income-to-needs mean | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.18 | 0.06 | <.01 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.40 |

| Size | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Observed emotional support | 0.34 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.05 | <.001 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.16 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.14 | 0.05 | <.01 |

Note: Coefficients are standardized. All three outcomes were modeled simultaneously to account for their shared variance. Models also control for cohort, site, and program type. White was treated as the reference group for child race/ethnicity.

Individual Children’s Observed Interactions with the Teacher as a Function of Teacher-Child Racial/Ethnic Match

We tested whether children in racially/ethnically matched teacher-child dyads were observed to interact more positively with the teacher when compared to teacher-child racially/ethnically mismatched pairs. Results for the model testing the different combinations of teacher-child racial/ethnic match and mismatch are displayed in Table 4. White children with a Black teacher exhibited lower conflict (β = −0.05, SE = 0.02, p = .03) when compared to Black children with a White teacher. No other significant differences were observed for teacher-child racial/ethnic match/mismatch subgroups with Black or White children.

Table 4.

Associations between teacher-child racial/ethnic match/mismatch and children’s average observed interaction quality with the teacher across the preschool year.

| Positive engagement with the teacher | Communication with the teacher | Conflict with the teacher | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | S. E. | p-value | Est. | S. E. | p-value | Est. | S. E. | p-value | |

|

| |||||||||

| Teacher-child racial/ethnic match/mismatch | |||||||||

| Black child-teacher match | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.68 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.73 |

| White child-teacher match | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.79 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.53 |

| White child-Black teacher | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.55 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.36 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Latino child-White teacher | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Child covariates | |||||||||

| Boy | −0.15 | 0.03 | <.001 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Income-to-needs | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Age in months | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.34 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.56 |

| Receptive language | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Expressive language | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.89 |

| Behavioral self-regulation | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.85 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.30 |

| Inhibitory control | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.79 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.56 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.35 |

| Math reasoning, applied problems | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.35 | −0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Math reasoning, quant. concepts | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.44 |

| Teacher/classroom covariates | |||||||||

| Income-to-needs mean | −0.21 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.20 | 0.07 | <.001 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.65 |

| Size | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.53 |

| Observed emotional support | 0.39 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.31 | 0.05 | <.001 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.05 | <.001 | 0.17 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

Note: Coefficients are standardized. All three outcomes were modeled simultaneously to account for their shared variance. Models also control for cohort, site, and program type. Black child-White teacher pairs were treated as the reference group for teacher-child racial/ethnic match/mismatch.

Discussion

Pianta and colleagues’ (2003) conceptual model of teacher-child relationships compelled a descriptive examination of the observed quality of interactions between teachers and individual children in preschool classrooms. According to this model, patterns of teacher-child interactive behaviors play a central role in the establishment and maintenance of each individual’s representation of the teacher-child relationship. Yet, an in-depth description of patterns of observed interactive behaviors between individual children and teachers is lacking in the literature (Vershueren & Koomen, 2012). We took a step toward addressing this gap in the literature by: (1) describing the average quality of dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool classrooms serving low-income children and its variability across and within classrooms and (2) exploring if interaction quality varies as a function of children’s gender, children’s race/ethnicity, and teacher-child racial/ethnic match, while accounting for key covariates. Results showed that the quality of individual children’s observed interactions with the teacher was low on average, with substantive variation within classrooms. Findings also indicated that observed interaction quality with teachers was lower for boys than for girls, mirroring previous findings that teachers perceive reduced relational quality with boys (e.g., Ewing & Taylor, 2009; Horn et al., 2021; Silver et al., 2005). Black children were not observed to interact less positively with teachers than their White peers, which is inconsistent with some previous work on teachers’ reduced relational quality with Black children (e.g., Loomis, 2021; O’Connor, 2010; Saft & Pianta, 2001). We found no evidence that teacher-child racial/ethnic match positively shapes children’s interactions with teachers. These findings advance our understanding of dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool classrooms and raise questions that can ultimately help to improve interactions and relationships equitably.

Individual Children’s Observed Interactions with the Teacher

Children’s explicit positive and negative interactions with the teacher were infrequently observed on average across this sample, although there was substantial within-classroom variability. Most children showed some indication of an emotional connection with the teacher, as evidenced by children being moderately attuned and seeking proximity to the teacher, along with sharing positive affect with them. However, it is striking that 59% (n = 448) of children were never observed, across 18 observation cycles, to display a strong emotional connection with the teacher. Further, children were rarely observed to initiate and sustain conversations with the teacher. Eighty-eight percent (n = 665) of children were never observed, across the 18 observation cycles, to display high communication with the teacher. In terms of negative interactions, children were rarely observed to display tension, resistance, and negativity with the teacher, as evidenced by 99% of observation cycles showing low conflict. Thus, on average, children were not particularly emotionally connected or communicative with the teacher but did not show negative affect or aggression either.

The observation of minimal to no conflict between children and teachers is encouraging, as the negative repercussions of conflictual relationships for children are stronger than the positive benefits of close relationships (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Pakarinen et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the relatively little positive engagement and—to a greater degree—communication between children and teachers is concerning yet aligned to prior work. For instance, observational work in state-funded preschool classrooms found that children spend 44% of the school day engaged in standard routines (e.g., hand washing) with very little scaffolded interactions with adults (Early et al., 2010). Further observational work in preschool classrooms found that dual language learners had minimal language interactions with teachers, and the interactions that did occur were characterized as basic quality such as giving directions (Franco et al., 2019). One possible explanation for the limited one-one-one interactions is that preschool children spend much time in teacher-directed activities that target children’s academic school readiness (Markowitz & Ansari, 2020). When teachers are directing instruction, it is likely that children have few opportunities to initiate a conversation with teachers, seek proximity to them, or share their affect. A second potential explanation is related to early childhood teachers’ poor work conditions (e.g., low wages, limited work time). A study by King and colleagues (2016) demonstrated that teachers’ financial well-being—both their wages and perceived ability to pay basic expenses—predicts children’s positive emotional expressions and behaviors, accounting for observed classroom quality. If teachers are worried about their financial well-being, they may be less present and available for children to engage positively with them.

Individual Children’s Observed Interactions with the Teacher as a Function of Children’s Gender, Children’s Race/Ethnicity, and Teacher-Child Racial/Ethnic Match

A robust finding in the teacher-child relationship literature is that teachers perceive reduced relational quality with boys compared to girls (Choi & Dobbs-Oates, 2016; Hajovsky et al., 2017; Spilt et al., 2012). The current study’s findings suggest that teachers’ perceptions of relationship quality may be shaped by how boys interact with them in the classroom. We found that boys demonstrate more conflict with teachers compared to girls. It is not surprising, then, that teachers perceive more conflictual relationships with boys (e.g., Hajovsky et al., 2017; Jerome et al., 2009). However, boys’ reduced relationship quality with teachers may not be entirely due to more conflictual interactions. The current study also found that boys have less explicitly positive interactions with the teacher when compared to girls. It is possible that boys are socialized to seek more autonomy and independence, whereas girls are socialized to seek more nurturing and emotionally rewarding interactions (Ewing & Taylor, 2009). As a result, boys may be less likely to seek proximity or be attuned to the teacher than girls, resulting in fewer indications of boys being emotionally connected with the teacher, which in turn may influence teachers’ perceptions of closeness with them. Importantly, boys’ conflictual interactions with teachers may also be influenced by teachers’ behavior toward them. In prior work, teachers have been observed to issue more rewards to girls than boys (Dobbs, Arnold, & Doctoroff, 2004), which may discourage boys and contribute to more conflictual interactions with teachers that were observed in the current study. Future work should attend to both reducing boys’ conflictual interactions with teachers and improving their positive engagement with teachers. For example, teachers could be more widely trained in practices borrowed from evidence-based teacher-child relationship interventions, including how to engage with children in meaningful ways during child-driven activities that support their autonomy (Driscoll & Pianta, 2010; Vancraeveldt et al., 2015; Williford et al., 2017) These steps could change the pattern of interactions between boys and their teachers, ultimately helping to improve the quality of boys’ relationships with teachers.

Regarding children’s race/ethnicity, we found that Black children were observed to engage more positively with the teacher than White children, after controlling for teachers’ ethnicity. Although the association found was very small and requires replication, it provides some signal that Black children engage with their teachers just, if not more, positively compared to their White peers. Further, there were no differences between Black and White children’s conflict with the teacher, controlling for teachers’ ethnicity. Our findings related to racially/ethnically matched and mismatched dyads are less straightforward. First, we did not find evidence that Black or White children in racially/ethnically matched teacher dyads (i.e., White child-White teacher or Black child-Black teacher) displayed higher positive engagement, higher communication, or lower conflict with teachers, compared to Black children with a White teacher. Contrary to prior work showing that teachers’ perceptions of relationship quality are more positive when the teacher and child share a racial/ethnic background (Saft & Pianta, 2001), in this study teacher-child racial/ethnic match did not promote children’s dyadic interactions with their teacher. White children with a Black teacher showed lower conflict compared to Black children with a White teacher, although the magnitude of the association was very small. The links between racial/ethnic match and children’s dyadic interactions with teachers are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution until more replication studies have been conducted.

Overall, findings from the current study indicate that Black children interact just as, if not more, positively with teachers compared to White children. Reconciling these findings in light of prior research showing that teachers perceive higher relational conflict with Black versus White children, even after accounting for cumulative adversity (Loomis, 2021), underscores the salience of teachers’ interpretation of children’s interactive behaviors. Indeed, a prior study found that teachers’ reports of relational quality with children were more reflective of their appraisals of children’s behavior (i.e., this behavior hinders the child’s development) than their perceptions of the actual behavior (Thijs & Koomen, 2009). Another study found that preschool teachers watch Black children more closely than White children, in anticipation of observing challenging behaviors, despite no such behaviors occurring (Gilliam et al., 2016). Applied to the current study, although Black children were observed to interact similarly or more positively with teachers than White children, teachers may hold implicit racial biases that negatively influence their perceptions or appraisals of Black children’s behavior, which can have repercussions for perceived relational quality (Neal et al., 2003). To reduce the disparities in teachers’ perceptions of their relationships between White and Black children, teachers can be supported to objectively observe children’s interactive behaviors in the classroom and reflect on how they appraise children’s behaviors (Okonofua et al., 2020).

Findings from the current study also raise important directions for future research. First, future research should examine the links between teacher and contextual factors (e.g., teacher work conditions) and the quality of dyadic teacher-child interactions in preschool, to better understand why such limited one-on-one interactions between children and teachers are occurring and to align support with the issue at hand. Second, more work should unpack drivers of teachers’ interactions with individual children. Although the current study focused on children’s observed interactions with teachers and how this varies by child and dyad sociodemographic characteristics, teachers’ beliefs about and interactions with children are equally important as teachers and children influence each other in a bidirectional manner (Doumen et al., 2008). Future research could build off Thijs & Koomen (2009) to examine whether teachers appraise children’s interactions differently depending on the child’s gender, child’s race/ethnicity, and the teacher-child racial/ethnic match and whether these appraisals then lead to teachers’ interacting differently with individual children. Future work could also test whether teachers’ attributions of children’s interactions are more strongly linked to perceived relational quality depending on the child’s gender or race/ethnicity or the teacher-child racial/ethnic match. Empirically testing the interplay between observed dyadic teacher-child interactions from the perspective of the child and the teacher, teachers’ appraisals of children’s behavior, and children’s and teachers’ gender and race/ethnicity will advance our understanding of how teachers establish relational perceptions with children which will help to ultimately improve them.

Limitations

The present study contributes knowledge on preschool children’s observed dyadic interactions with teachers, however, several limitations deserve discussion. First, although were interested in understanding dyadic teacher-child interactions due to their theorized importance for establishing teacher-child relationships, teachers’ perceptions of relationships with children were not collected in this study. Thus, we were unable to empirically test the relations between dyadic interactions and relationship quality or the extent to which this relation varies by child and dyad sociodemographic characteristics. Second, while our findings are based on extensive observational data in preschool classrooms, a significant addition to the literature base, it is possible that bias influenced observers’ perceptions of dyadic teacher-child interaction quality. Although a racially/ethnically diverse group of data collectors rated the quality of teacher-child interactions using a standardized measure, we did not explore the extent to which data collectors observed same-race children or differences in raters’ scores by race/ethnicity. Thus, while observations do provide unique information on children’s classroom interactions, they cannot be assumed to be void of bias. Third, we acknowledge that child and dyad sociodemographic characteristics had small associations with children’s observed interaction quality and that child characteristics are only part of the complex and dynamic systems that influence the quality of teacher-child relationships (Pianta et al., 2003). Future work should not only replicate the current study’s finding, but also examine dyadic interactive behaviors from the teacher perspective and assess the extent to which child and teacher interactive behaviors jointly contribute to teacher-child relationships.

Conclusion

Repeated interactions between children and teachers provide salient information to guide how teachers and children build their perceptions of teacher-child relationship quality (Pianta et al., 2003), but attention to this process is lacking in the teacher-child relationship literature (Vershueren & Koomen, 2012). This study examined dyadic teacher-child interaction patterns in preschool classrooms serving children from low-income households. Findings indicate that, on average, children were not particularly engaged in rich one-on-one interactions with teachers yet displayed little conflict. Substantive within-classroom variability in dyadic teacher-child interactions was also observed. Given the benefits of a strong teacher-child relationship, particularly for children coming from low-income communities, these results highlight that teachers need more support to engage with individual children in more positive and child-directed interactions. Findings from this study also underscore the need for future research on the interplay between teacher-child interactions and teachers’ perceptions of relational quality to advance our understanding of how teachers and children establish, maintain, and modify their perceptions of relationship quality with one another.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank the generous programs, teachers, families, and children who participated in this study.

Funding:

This manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), through grant number 2R01HD051498–06A1 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Declarations

Ethics Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication. Participants signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

In cohort one, one child transferred to a different study classroom during the year and two teachers who moved or took an extended leave and were replaced by a new teacher, bringing the total to 53. In cohort two, two children transferred to a different study classroom during the year and three teachers were replaced, bringing the total to 56. Three teachers participated in both study cohorts.

Availability of Data, Code, and Material.

Data not available due to confidentiality agreements (IRB) restrictions.

References

- Baker JA (2006). Contributions of teacher-child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1016.j.jsp.2006.02.002 [Google Scholar]

- Bardack S, & Obradović J (2017). Emotional behavior problems, parent emotion socialization, and gender as determinants of teacher–child closeness. Early Education and Development, 28(5), 507–524. 10.1080/10409289.2017.1279530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann NL, Downer JT, Williford AP, Maier MF, Booren LM, & Howes C (2019). Observing children’s engagement: Examining factorial validity of the inCLASS across demographic groups. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 60, 166–176. 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booren LM, Downer JT, & Vitiello VE (2012). Observations of children’s interactions with teachers, peers, and tasks across preschool classroom activity settings. Early Education & Development, 23(4), 517–538. 10.1080/10409289.2010.548767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman RJ, Roorda DL, van der Veen I, & Koomen H (2018). Teacher-student relationship quality from kindergarten to sixth grade and students’ school adjustment: A person-centered approach. Journal of School Psychology, 68, 177–194. 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Pianta RC, & Howes C (2002). Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: Family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. Journal of School Psychology, 40(5), 415–436. 10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00107-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, & Dobbs-Oates J (2016). Teacher-Child Relationships: Contribution of Teacher and Child Characteristics. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(1), 15–28. 10.1080/02568543.2015.1105331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CR, Coco S, Zhang Y, Fiat AE, Duong MT, Renshaw TL, Long AC, & Frank S (2018). Cultivating positive teacher-student relationships: Preliminary evaluation of the Establish-Maintain-Restore (EMR) method. School Psychology Review, 47(3), 226–243. 10.17105/SPR-2017-0025.V47-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs J, & Arnold DH (2009). Relationship between preschool teachers’ reports of children’s behavior and their behavior towards those children. School Psychology Quarterly, 24(2), 95–105. 10.1037/a0016157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs J, Arnold DH, & Doctoroff GL (2004). Attention in the preschool classroom: The relationships among child gender, child misbehavior, and types of teacher attention. Early Childhood Development and Care, 174(3), 281–295. 10.1080/0300443032000153598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doumen S, Verschueren K, Buyse E, Germeijs V, Luyckx K, & Soenens B (2008). Reciprocal relations between teacher-child conflict and aggressive behavior in kindergarten: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 588–599. 10.1080/15374410802148079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Booren LM, Lima OK, Luckner AE, & Pianta RC (2010). The Individualized Classroom Assessment Scoring System (inCLASS): Preliminary reliability and validity of a system for observing preschoolers’ competence in classroom interactions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 1–16. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KC, & Pianta RC (2010). Banking Time in Head Start: Early efficacy of an intervention designed to promote supportive teacher-child relationships. Early Education and Development, 21(1), 38–64. 10.1080/10409280802657449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn DM (2007). PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test (4th ed.), Pearson Assessments. [Google Scholar]

- Early DM, Iruka IU, Ritchie S, Barbarin OA, Winn D-MC, Crawford GM, Frome PM, Clifford RM, Burchinal M, Howes C, Bryant DM, & Pianta RC (2010). How do pre-kindergarteners spend their time? Gender, ethnicity, and income as predictors of experiences in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 177–193. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AR, & Taylor AR (2009). The role of child gender and ethnicity in teacher-child relationship quality and children’s behavioral adjustment in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 92–105. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franco X, Bryant DM, Gillanders C, Castro DC, Zepeda M, & Willoughby MT (2019). Examining linguistic interactions of dual language learners using the Language Interaction Snapshot (LISn). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 50–61. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KC, Kainz K, Vernon-Feagans L, & White KM (2013). Development of student-teacher relationships in rural early elementary classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 520–528. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, & Mahatmya D (2015). Affective social competence and teacher–child relationship quality: Race/ethnicity and family income level as moderators. Social Development, 24(3), 678–697. 10.1111/sode.12114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR, Accavitti M, & Shic F (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions? Yale University Child Study Center. https://medicine.yale.edu/childstudy/zigler/publications/Preschool%20Implicit%20Bias%20Policy%20Brief_final_9_26_276766_5379_v1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Guedes C, Cadima J, Aguiar T, Aguiar C, & Barata C (2020). Activity settings in toddler classrooms and quality of group and individual interactions. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 67, 101100. 10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajovsky DB, Chesnut SR, & Jensen KM (2020). The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the development of teacher-student relationships. Journal of School Psychology, 82, 141–158. 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajovsky DB, Mason BA, & McCune LA (2017). Teacher-student relationship quality and academic achievement in elementary school: A longitudinal examination of gender differences. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 119–133. 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam RA, Fouts HN, Bargreen KN, & Perkins K (2016). Teacher–child interactions during mealtimes: Observations of toddlers in high subsidy child care settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44, 51–59. 10.1007/s10643-014-0678-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, & Pianta RC (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. 10.1111/1467-8624.00301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC, Downer JT, & Mashburn AJ (2008). Teachers’ perceptions of conflict with young students: Looking beyond problem behaviors. Social Development, 17, 115–136. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00418.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC, Mashburn AJ, & Downer JT (2007). Building a science of classrooms: Applications of the CLASS Framework in over 4,000 U.S. early childhood and elementary classrooms. https://www.fcdus.org/sites/default/files/BuildingAScienceOfClassroomsPiantaHamre.pdf

- Hartz K, Williford AP, & Koomen HMY (2017). Teachers’ perceptions of teacher-child relationships: Links with children’s observed interactions. Early Education and Development, 28(4), 441–456. 10.1080/10409289.2016.1246288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho H, Gol-Guven M, & Bagnato SJ (2012). Classroom observations of teacher-child relationships among racially symmetrical and racially asymmetrical teacher-child dyads. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(3), 329–349. 10.1080/1350293X.2012.704759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horn EP, McCormick MP, O’Connor EE, McClowry SG, & Hogan FC (2021). Trajectories of teacher-child relationships across kindergarten and first grade: The influence of gender and disruptive behavior. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55, 107–118. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Fuligni AS, Hong SS, Huang YD, & Lara-Cinisomo S (2013). The preschool instructional context and teacher-child relationships. Early Education and Development, 24(3), 273–291. 10.1080/10409289.2011.649664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iruka IU, Curenton SM, Durden TR, & Escayg KA (2020). Don’t look away: Embracing anti-bias classrooms. Gryphon House. [Google Scholar]

- Iruka IU, Curenton SM, Sims J, Blitch KA, & Gardner S (2020). Factors associated with early school readiness profiles for Black girls. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 51, 215–228. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon HJ, Langill CC, Peterson CA, Luze, Gayle J, Carta JJ, & Atwater JB (2010). Children’s individual experiences in early care and education: Relations with overall classroom quality and children’s school readiness. Early Education and Development, 21(6), 912–939. 10.1080/10409280903292500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome EM, Hamre BK, & Pianta RC (2009). Teacher-child relationships from kindergarten to sixth grade: Early childhood predictors of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness. Social Development, 18(4), 915–945. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00508.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincade L, Cook C, & Goerdt A (2020). Meta-analysis and common practice elements of universal approaches to improving student-teacher relationships. Review of Educational Research, 90(5), 710–748. 10.3102/0034654320946836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King EK, Johnson AV, Cassidy DJ, Wang YC, Lower JK, & Kintner-Duffy VL (2016). Preschool teachers’ financial well-being and work time supports: Associations with children’s emotional expressions and behaviors in classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44, 545–553. 10.1007/s10643-015-0744-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM (1998). Theories of human development: Contemporary perspectives. In Damon W & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 1–24). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Liew J, Chen Q, & Hughes JN (2010). Child effortful control, teacher-student relationships, and achievement in academically at-risk children: Additive and interactive effects. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 51–64. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippard CN, La Paro KM, Rouse HL, & Crosby DA (2018). A closer look at teacher-child relationships and classroom emotional context in preschool. Child & Youth Care Forum, 47(1), 1–21. 10.1007/s10566-017-9414-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Minca E, & Adar S (2012). The geography of inequality: Why separate means unequal in American public schools. Sociology of Education, 85, 287–301. 10.1177/0038040711431588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis AM (2021). The influence of early adversity on self-regulation and student-teacher relationships in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 54, 294–306. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Carreño C, & Votruba-Drzal E (2011). Teacher-child relationships and the development of academic and behavioral skills during elementary school: a within- and between-child analysis. Child Development, 82(2), 601–616. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz AJ, & Ansari A (2020). Changes in academic instructional experiences in Head Start classrooms from 2001–2015. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 534–550. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Pianta RC, Hamre BK, Downer JT, Barbarin OA, Bryant D, Burchinal M, Early DM, & Howes C (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79(3), 732–749. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Connor CM, Farris CL, Jewkes AM, & Morrison FJ (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 947–959. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MP, O’Connor EE, & Horn EP (2017). Can teacher-child relationships alter the effects of early socioeconomic status on achievement in middle childhood? Journal of School Psychology, 64, 76–92. 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan BT, Hughes JN, & Cavell TA (2003). Teacher-student relationships as compensatory resources for aggressive children. Child Development, 74(4), 1145–1157. 10.1111/1467-8624.00598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, & Murray KM (2004). Child level correlates of teacher-student relationships: An examination of demographic characteristics, academic orientations, and behavioral orientations. Psychology in the Schools, 41(7), 751–762. 10.1002/pits.20015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C Waas GA, & Murray KM (2008). Child race and gender as moderators of the association between teacher-child relationships and school adjustment. Psychology in the Schools, 45(6), 562–578. 10.1002/pits.20324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2012–2019). Mplus (Version 8.3). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neal LVI, McCray AD, Webb-Johnson G, & Bridgest ST (2003). The effects of African American movement styles on teachers’ perceptions and reactions. The Journal of Special Education, 37(1), 49–57. 10.1177/00224669030370010501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor EE (2010). Teacher-child relationships as dynamic systems. Journal of School Psychology, 48, 187–218. 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua JA, Perez AD, & Darling-Hammond S (2020). When policy and psychology meet: Mitigating the consequences of bias in schools. Science Advances, 6(42), eaba9479. 10.1126/sciadv.aba9479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakarinen E, Lerkkanen MK, Vilijaranta J, & von Suchodoletz A (2021). Investigating bidirectional links between the quality of teacher-child relationships and children’s interest and pre-academic skills in literacy and math. Child Development, 92(1), 388–407. 10.1111/cdev.13431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelatti CY, Piasta SB, Justice LM, & O’Connell A (2014). Language- and literacy-learning opportunities in early childhood classrooms: Children’s typical experiences and within-classroom variability. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 445–456. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R, Hamre B, & Stuhlman M (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. In Reynolds WM, Miller GE, & Weiner IB (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Vol. 7. Educational psychology (pp. 199–234). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, La Paro KM, & Hamre BK (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System [CLASS] manual: Pre-K. Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ponitz CEC, McClelland MM, Jewkes AM, Connor CM, Farris CL, & Morrison FJ (2008). Touch your toes! Developing a direct measure of behavioral regulation in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(2), 141–158. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed DS, Brown JL, Doyle SL, & Jennings PA (2020). The effect of teacher-child race/ethnicity matching and classroom diversity on children’s socioemotional and academic skills. Child Development, 91(3), e597–e618. 10.1111/cdev.13275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roorda DL, Koomen HMY, Thijs JT, & Oort FJ (2013). Changing interactions between teachers and socially inhibited kindergarten children: An interpersonal approach. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34, 173–184. 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]