Abstract

Cholera is an enteric disease caused by Vibrio cholerae. Toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP), a type 4 pilus expressed by V. cholerae, is a cholera virulence factor that is required for host colonization. The TCP polymer is composed of subunits of TcpA pilin. Antibodies directed against TcpA are protective in animal models of cholera. While natural or recombinant forms of TcpA are difficult to purify to homogeneity, it is anticipated that synthesized TcpA peptides might serve as immunogens in a subunit vaccine. We wanted to assess the potential for effects of the immune response (Ir) gene that could complicate a peptide-based vaccine. Using a panel of mice congenic at the H-2 locus we tested the immunogenicity of TcpA peptide sequences (peptides 4 to 6) found in the carboxyl termini of both the classical (Cl) and El Tor (ET) biotypes of TCP. Cl peptides have been shown to be immunogenic in CD-1 mice. Our data clearly establish that there are effects of the Ir gene associated with both biotypes of TcpA. These effects are dynamic and dependent on the biotype of TcpA and the haplotypes of the host. In addition to the effects of the classic class II Ir gene, class I (D, L) or nonclassical class I (Qa-2) may also affect immune responses to TcpA peptides. To overcome the effects of the class II Ir gene, multiple TcpA peptides similar to peptides 4, 5, and 6 could be used in a subunit vaccine formulation. Identification of the most protective B-cell epitopes of TcpA within a particular peptide and conjugation to a universal carrier may be the most effective method to eliminate the effects of the class II and class I Ir genes.

Cholera is an acute diarrheal disease caused by the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The major secreted or surface-expressed virulence factors of V. cholerae are cholera toxin and toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) (7; reviewed in reference 9). TCP is a type 4 pilus composed of a homopolymer of 20.5-kDa TcpA pilin subunits that mediate V. cholerae colonization (8, 11, 20, 22). The TCP is allelic, i.e., there are two predominant biotype-specific derivatives of TcpA (classical and El Tor), which differ by 18.1% at the protein level in the region defined by amino acids 145 to 199 (15). TcpA and peptides derived from it are immunogenic and induce protective antibodies (Abs) when not delivered in the context of a natural infection or vaccination with intact bacteria (7, 16–19). Anti-TCP Abs when mixed with virulent V. cholerae (500 times the 50% lethal dose [LD50]) and fed to infant mice provide almost complete immunity to cholera (16, 17). The regions of classical TcpA that neutralizing Abs are directed against have been partially defined. Results of several experimental approaches have indicated that domains within the C-terminal region of TcpA (amino acids 145 to 199) delineated by a single disulfide bond can induce the protective Ab response seen in animals (16, 17). Peptides Cl-4, Cl-5, and Cl-6 induce immune responses in mice that can protect 50 to 89% of infant mice against a 100LD50 challenge in the infant mouse cholera model (17). Recent results (24) have further demonstrated that TcpA-derived peptides and new experimental polymer adjuvants induce Ab responses in female mice that protect their pups from V. cholerae infection. The previous studies were focused on the classical biotype of TCP. TCP of El Tor biotypes has not been analyzed for protective epitopes of peptides 4, 5, and 6. Therefore, it is of interest to compare the immunogenicities of peptides 4, 5, and 6 of the two TCP biotypes.

The effects of the immune response (Ir) gene were first described in 1965 by McDeveitt and Sella (12). They showed that a branched polymer composed of a backbone of l-lysine with side chains of dl-alanine conjugated randomly with tyrosine-glutamate when emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA) was able to induce a robust Ab response in C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) and only a low Ab response in CBA mice (H-2k). This and similar phenomena were described as effects of the Ir gene. Interestingly, the (C57BL/6 × CBA)F1 mice made intermediate responses. These results, along with results from an F1 × C57BL/6 cross that showed a predominantly high response, suggested that a single gene was controlling the serologic response. Long-term studies using congenic mice clearly implicated the H-2 locus between K and Ss as containing the genes that controlled this phenomenon. Subsequent studies have shown that the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules are critical for induction of Ab responses and that it is the associated genes in the H-2 locus that mediate the effects of the Ir gene. In the past 35 years, scientists have defined the role of class II in the induction of CD4+ T-cell help for Ab formation. We know that binding peptide antigens (a fragment of the B-cell-internalized antigen) in the class II binding cleft is critical for B-cell presentation of the complex to CD4+ T helper cells. The allelic variations in class II molecules among the H-2 types dictate the ability to bind peptides and thus the capacity to activate antigen-specific CD4+ T cells (2, 5, 14, 23). There is a compelling data set that indicates that the peptide and H-2 sequences must be optimized for effective presentation to induce T-cell help.

If subunit vaccines based on protein sequences are to be useful, they must be able to induce responses in a large percentage of the target population. Classical peptides 4, 5, and 6 are 24 to 26 amino acids in length. Thus, they are long enough to contain both B-cell epitopes (binds surface immunoglobulin to select a B cell) and T-cell epitopes (presented by class II to provide T-cell help). This has been demonstrated for peptides 4 and 6 in CD-1 mice, which are outbred mice of the H-2q haplotypes (24). The issue at hand is to determine if the serologic and protective responses to peptides 4, 5, and 6 are indicative of universal T-cell epitopes for class II molecules or whether the effects of the Ir gene will be evident from limited amino acid sequences. In addition, the allelic differences between Cl and El Tor TCP biotypes could complicate a simple assignment of reactivity based on H-2 type.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Three- to 5-week-old female congenic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). At 8 weeks, 4 to 6 mice per haplotype group were immunized as described below. The congenic mouse strains used were as follows: H-2k, B10.A-H2a H2-T18a/SgSnJ; H-2b, C.B10-H2b/LilMcdJ; H-2d, B10.D2-H2d H2-T18c Hc 1/nSnJ, and H-2k, B10.BR-H2k H2-T18a/SgSnJ. All mice were housed under standard conditions in the Animal Resources Center located at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (Lebanon, N.H.) and maintained on a basic diet of Harlan (Madison, Wis.) Teklad sterilizable rodent feed.

Materials and reagents.

FCA and Freund's incomplete adjuvant (FIA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocking buffer (1× PBS, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Tween 20), wash buffer (1× PBS, 0.05% Tween 20), binding buffer (0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 9.0), and stop solution (0.18 M H2SO4) were all prepared in-house using chemicals purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, Pa.) and Sigma. Methoxyflurane (Metofane) was manufactured by Schering-Plough Animal Health Corp. (Union, N.J.). Heparinized microhematocrit capillary tubes were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Seal-Rite 1.5-ml Natural microcentrifuge tubes and 0.5-ml self-standing microcentrifuge tubes with O-ring caps were purchased from USA Scientific, Inc. Perfektum 5-ml glass needle-lock tip syringes and Popper 20-gauge microemulsifying needles were purchased from Fisher Scientific. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) peroxidase substrate was purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories (Gaithersburg, Md.). All horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary Abs were purchased from Southern Biotechnology Associates (Birmingham, Ala.). One-milliliter Luer-Lok latex-free syringes and 22-gauge PrecisionGlide needles used to deliver the immunogens were manufactured by Becton Dickinson and Co. and were purchased from the local stockroom. Falcon PRO-BIND 96-well U-bottom assay plates used to dilute antisera for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were purchased from Fisher Scientific.

Peptides.

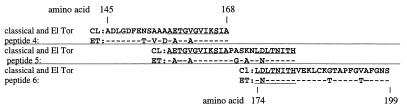

TcpA fragment peptides 4, 5, and 6, derived from sequences of either classical or El Tor biotypes of V. cholerae, were commercially prepared by Macromolecular Resources (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colo.). The peptides used in single letter amino acid code are as follows: ET-4, ADLGDFETSVADAATGAGVIKSIA; ET-5, AATGAGVIKSIAPGSANLNLTNITH; ET-6, LNLTNITHVEKLCTGTAPFTVAFGNS; Cl-4, ADLGDFENSAAAAETGVGVIKSIA; Cl-5, AETGVGVIKSIAPASKNLDLTNITH; Cl-6, LDLTNITHVEKLCKGTAPFGVAFGNS. The relative positions of these peptides are shown in Fig. 1. The lyophilized peptides were resuspended in 5.0% dimethyl sulfoxide–water–0.25× PBS to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and stored at −80°C in 1.0-ml aliquots until used.

FIG. 1.

Sequences and location of the synthetic peptides within the context of amino acids 145 to 199 of classical and El Tor TcpA. Peptides 4, 5, and 6 were synthesized based on the predicted amino acid sequences from cloned classical and El Tor tcpA genes. Dashes, amino acid sequences that are shared. Peptide lengths are as follows: 24-mer for Cl-4 and ET-4, 25-mer for Cl-5 and ET-5, and 26-mer for Cl-6 and ET-6. Underlined sequences are shared between peptides 4 and 5, and 5 and 6 for the same biotype.

Immunization and serum collection.

Peptide antigen emulsions were prepared by diluting peptides in 1× PBS and then mixing with adjuvant in a 1:1 ratio. Mice were administered peptides (25 μg/mouse) via intraperitoneal injection (200 μl/mouse) with FCA for the primary inoculation (day 0) and with FIA for the secondary and tertiary inoculations (days 14 and 28). Preimmune sera were collected 1 to 2 weeks before the primary immunization. The primary-response sera were collected at day +14, and the secondary- and tertiary-response sera were collected at days +28 and +42, respectively.

Blood collection was conducted under light methoxyflurane anesthesia via the orbital venous sinus and plexus or via the tail vein when necessary. The blood was incubated for 30 min at 37°C immediately following collection and then kept at 4°C overnight. Samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 10,000 × g, and 20- to 25-μl aliquots of sera were stored at −20°C until used.

Serology.

Costar 96-well, high-binding, flat-bottom microtiter plates (Corning Incorporated Life Sciences, Acton, Mass.) were coated with 0.5 μg of peptides in 100 μl of 0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 9.0, overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed four times using a Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, Calif.) Skan Washer 400 microplate washer with 250 μl of 1× PBS–0.05% Tween 20. Nonspecific binding was blocked using 200 μl of 1× PBS–0.05% Tween 20–1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were washed four more times, and 50 μl of serially twofold-diluted antiserum was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h and then overnight at 4°C. The initial dilutions were 1:500 for preimmune and primary sera, 1:1,000 for secondary sera, and 1:2,000 for tertiary sera, except for Cl-5 tertiary sera, for which a dilution of 1:2,500 was used for the analysis. Plates were washed six times, and 50 μl of horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG1 (γ1 chain-specific) or IgG2a (γ2a chain-specific) detector antibodies (diluted 1:4,000) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h protected from light. Plates were washed eight times and were then developed with 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine peroxidase substrate for 15 to 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with an equal volume of 0.18 M H2SO4. Optical densities were read using a Dynex Technologies MRX microplate reader (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) using Dynex Revelation, version 3.04, software at 450 nm with 630 nm as the reference wavelength.

Data analysis and statistics.

All calculations and statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel, version 9.0, and GraphPad Prism, version 3.0. The end point titer was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution for the last positive well for each sample after subtracting the background. Background values were defined as twice the mean optical density for all blank wells on a single microtiter plate. Wells containing the lowest dilution for prebleed samples were chosen to be blank background wells. One blank well was selected for each mouse on an individual plate.

Immune responses to the peptides by each haplotype were scored using the following criteria. A + was awarded for each set of sera (primary, secondary, or tertiary) if all the mice responded to the immunization. If only two sets of sera responded e.g., secondary and tertiary, the group was scored ++. If all the mice associated with all three serum sets responded, the score was +++. A further refinement in the scoring was based on the totality of the response. Responses by more than one mouse, but not the entire group, for a particular sera set were scored +/−. If no mice or only one mouse in the group responded, the group was scored −. If more than one mouse, but not all the mice, showed a positive response in the primary and secondary sera, yet the tertiary sera were all positive, the group was scored +/−/+/−/+. To generate the number for the comparison of the immune index, groups were assigned scores based on the response pattern: +, 5 points; +/−, 2.5 points; −, 0 points. The values for the responses of the mice with various haplotypes to classical and El Tor TcpA peptides 4, 5, or 6 were tabulated (see Table 2). In addition, the immunogenicities of the peptides across the haplotypes were determined and related to IgG subclass responses.

TABLE 2.

Immune indices of classical and El Tor peptides 4, 5, and 6a

| Immunogen | IgG subclass | Immune index for sera from mice of haplotype:

|

Total for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-2a | H-2b | H-2d | H-2k | Immunogen | IgG subclass | Peptide | ||

| Cl-4 | IgG1 | 15 | 0 | 7.5 | 15 | 37.5 | 60 | 92.5 |

| ET-4 | 15 | 5 | 2.5 | 0 | 22.5 | |||

| Cl-4 | IgG2a | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 15 | +32.5 | |

| ET-4 | 12.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 17.5 | |||

| Cl-5 | IgG1 | 15 | 0 | 12.5 | 10 | 37.5 | 52.5 | 72.5 |

| ET-5 | 5 | 7.5 | 0 | 2.5 | 15 | |||

| Cl-5 | IgG2a | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 10 | +20 | |

| ET-5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |||

| Cl-6 | IgG1 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 60 | 97.5 |

| ET-6 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 7.5 | 22.5 | |||

| Cl-6 | IgG2a | 5 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 25 | +37.5 | |

| ET-6 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 12.5 | |||

| Total Cl | 55 | 0.0 | 50 | 57.5 | ||||

| Total ET | 37.5 | 27.5 | 20 | 15 | ||||

| Haplotype total | 92.5 | 27.5 | 70 | 72.5 | ||||

The reactivity of antisera from individual haplotypes of mice to individual biotype peptides was assessed. Scoring for the individual comparisons in this table was based on the ELISA results presented in Fig. 3 to 5, in which the anti-peptide 4, 5, and 6 responses for individual mice in the primary, secondary, and tertiary antisera were assessed. The reactivities of the group for a given serum set were scored as follows: −, 0 (no response); +/−, 2.5 (partial response for more than one mouse but not all); +, 5 (total response). The values in this table were used to generate the rank order of the reactivity for a given peptide shown in Results.

RESULTS

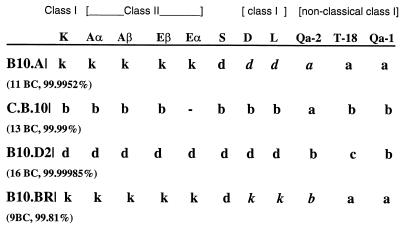

We selected four congenic strains of mice that represent the three most studied class II H-2 regions: H-2b, H-2k, and H-2d (Fig. 2). B10.A, B10.D2, and B10.BR mice express both class II isotypes, I-A and I-E, while C.B.10 mice express I-A only. We anticipated that immunization with TcpA peptide 4, 5, or 6 would be immunogenic in mice of some of the haplotypes as the peptides have previously been shown to provide for both B- and T-cell activation in CD-1 mice (H-2q).

FIG. 2.

Congenic mouse genotypes in the H-2 locus. H-2 congenic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, and the genotypes are presented as described in the supplier material. The number of backcrosses (BC) for each strain is shown, as is the percent identity of the genome based on the number of backcrosses. B10.A mice are H-2a; C.B.10 mice are H-2b; B.10.D2 mice are H-2d; B.10Br mice are H-2k. Differences between H-2a and H-2k mice are in italics.

Cl-4 and ET-4.

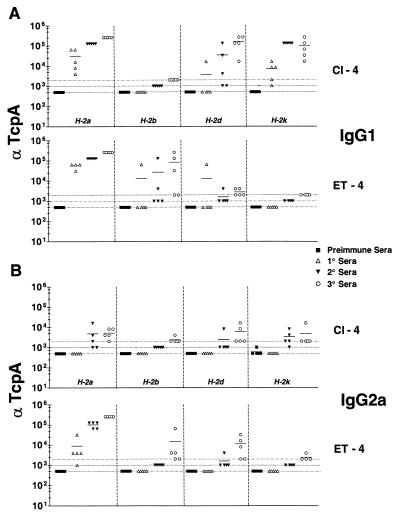

Following one intraperitoneal immunization of peptides in FCA and two with peptides in FIA, sera representing primary, secondary, and tertiary responses were collected and analyzed by ELISA to determine the anti-Cl-4 and anti-ET-4 titers (Fig. 3A [IgG1] and B [IgG2a]). The homologous systems were evaluated, e.g., the ET-4 peptide reacted with ET-4-specific sera. H-2a, H-2d, and H-2k mice immunized with Cl-4 responded well, making IgG1-specific Abs throughout the time course of immunization (Fig. 3A). H-2b mice were nonresponders to Cl-4, but certain mice in the group responded significantly in individual bleeds to ET-4. The IgG1 responses of H-2d mice to ET-4 were modest, a finding which differed from that reported for H-2d mice immunized with Cl-4.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of ELISA titers of classical and El Tor anti-peptide 4 IgG1 (A) or IgG2a (B). End point titers are shown as the reciprocal of the dilution for the last positive well for each serum analyzed. Cl-4 or ET-4 was bound to the plates in 0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 9.0, at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Preimmune and primary sera were diluted to 1:500, secondary sera were diluted to 1:1,000, and tertiary sera were diluted to 1:2,000. Dotted lines, baseline serum dilution. Symbols above the lines are considered positive. Means are indicated by solid lines.

The IgG2a responses to Cl-4 for H-2a, H-2d, and H-2k mice were also positive but of significantly less magnitude than the IgG1 responses (Fig. 3B). The IgG2a responses to ET-4 of H-2a and H-2k mice were comparable to the IgG1 response to ET-4. H-2b mice did not respond to ET-4 with as much IgG2a as IgG1. The IgG2a responses of H-2d mice to ET-4 were variable and low.

If ET-4 or Cl-4 peptides were used as the immunogen, clear effects of the Ir gene were evident in H-2b and H-2d mice. H-2b mice responded to ET-4 but not Cl-4; H-2d mice responded poorly to ET-4, as evidenced by the minimal production of IgG1 Abs, but responded well to Cl-4. Both H-2k and H-2a mice responded to Cl-4. Unexpectedly, H-2a mice responded to ET-4 but H-2k mice did not. This is surprising since both strains of mice express I-Ak/I-Ek. These mice, however, differ in the MHC-I locus. H-2a mice express Ld and Dd, whereas H-2k mice express Lk and Dk (Fig. 2). The H-2a mouse response to ET-4 for IgG2a was very robust compared to the anti-IgG2a response to Cl-4. The rank orders of response of the various haplotypes of mice to Cl-4 and ET-4 were as follows: Cl-4 (IgG1), H-2a = H-2k > H-2d (H-2b, 0); ET-4 (IgG1), H-2a = H-2b = H-2d (H-2k, 0); Cl-4 (IgG2), H-2a = H-2d = H-2k (H-2b, 0); ET-4 (IgG2), H-2a > H-2b = H-2d (H-2k, 0).

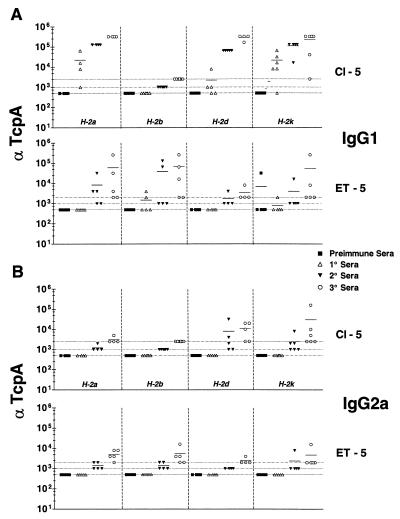

Cl-5 and ET-5.

H-2a, H-2d, and H-2k mice responded with robust IgG1 titers to Cl-5 (Fig. 4A). H-2b mice were again nonresponders to Cl-5. The IgG2a responses to Cl-5 of all the mice were low or absent (Fig. 4B). There was variability in H-2d and H-2k mice in the secondary and tertiary responses (IgG2a) to Cl-5, with not all of them responding. This was clearly different from the IgG1 responses of mice in these two haplotypes in which the overwhelming majority of the mice responded earlier and with higher titers of anti-Cl-5 IgG1. Clearly, for all mice that responded to immunization with Cl-5, the IgG1 response was induced earlier and to a higher degree than that for IgG2a.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of ELISA titers of classical and El Tor anti-peptide 5 IgG1 (A) or IgG2a (B). End point titers are shown as the reciprocal of the dilution for the last positive well for each serum analyzed. Cl-5 or ET-5 was bound to the plates in 0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 9.0, at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Preimmune and primary sera were diluted to 1:500, secondary sera were diluted to 1:1,000, and tertiary sera were diluted to 1:2,000, except for classical sera, which were diluted 1:2,500. Dotted lines, baseline serum dilution. Symbols above the lines are considered positive. Means are indicated by solid lines.

As with immunization of mice with ET-4, immunization with ET-5 revealed effects of the Ir gene. Specifically, H-2b mice did not respond to Cl-5 (Fig. 4A and B). H-2d mice generated marginal responses, thus marking H-2d mice as low responders to ET-5. Similarly, H-2k mice generated low titers in response to ET-5. It should be noted that the H-2a response to Cl-5 was absent in the IgG2a analysis compared to an early consistently high-titer IgG1 response (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the H-2a and H-2k mice that share class II molecules manifest the same qualitative response to Cl-5 or ET-5, which is in contrast to the differential ET-4 responses made by mice of these two haplotypes. The rank orders of response of the various haplotypes of mice to Cl-5 and ET-5 are as follows: Cl-5 (IgG1), H-2a > H-2d > H-2k (H-2b, 0); ET-5 (IgG1), H-2b > H-2a > H-2k (H-2d, 0); Cl-5 (IgG2), H-2d = H-2k (H-2a and H-2b, 0); ET-5 (IgG2), H-2a = H-2b (H-2d and H-2k, 0).

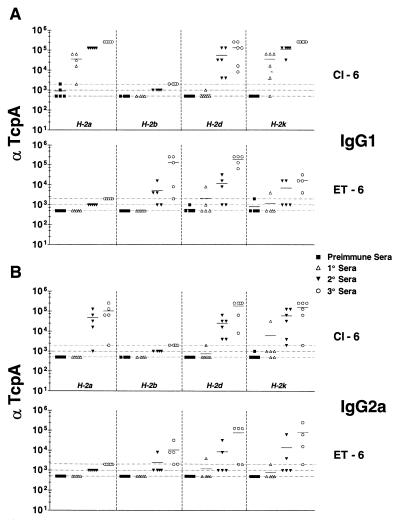

Cl-6 and ET-6.

H-2a, H-2d, and H-2k mice responded to Cl-6 with IgG1-specific Abs throughout the immunization time course, even though there was only one H-2d mouse that had a positive response in the primary sera. As before, the H-2b haplotype mice did not respond to the classical peptide, yet they did respond to the ET-6 peptide. H-2b, H-2d, and H-2k mice made IgG1 in response to ET-6, although the response of H-2k mice was not as high as those of H-2d and H-2b mice. H-2a haplotype mice were nonresponders to ET-6 but responded to Cl-6. This is in contrast to H-2a mice responding to ET-4 and ET-5. Immunization with either Cl-6 or ET-6 revealed a difference in the abilities of I-Ak/I-Ek mice to respond to a given peptide. H-2a mice did not respond to ET-6 while H-2k mice did. This was based on differences that map to the class I region of H-2.

The response to IgG2a of the various congenic mice to Cl-6 was similar to the IgG1 response (Fig. 5B). The IgG2a responses to ET-6 by H-2b, H-2k, and H-2d mice were not as high as the IgG1 responses. As with the IgG1 response, there was no IgG2a response to ET-6 by H-2a mice. The IgG2a responses to Cl-6 were generally as high as the IgG1 responses and thus different from the IgG2a responses of mice to Cl-4 and Cl-5, which were always lower than the IgG1 responses. The rank order of responses of the various haplotypes of mice to Cl-6 and ET-6 are as follows: Cl-6 (IgG1), H-2a > H-2k > H-2d (H-2b, 0); ET-6 (IgG1), H-2d > H-2k > H-2b (H-2a, 0); Cl-6 (IgG2), H-2d = H-2k > H-2a (H-2b, 0); ET-6 (IgG2), H-2k = H-2d > H-2b (H-2a, 0).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of ELISA titers of classical and El Tor anti-peptide 6 IgG1 (A) or IgG2a (B). End point titers are shown as the reciprocal of the dilution for the last positive well for each serum analyzed. Cl-6 or ET-6 were bound to the plates in 0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 9.0, at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Preimmune and primary sera were diluted to 1:500, secondary sera were diluted to 1:1,000, and tertiary sera were diluted to 1:2,000. Dotted lines, baseline serum dilution. Symbols above the lines are considered positive.

Cross-reactive B-cell epitopes in nonresponder peptide-haplotype combinations.

The lack of a serologic response to a TcpA peptide by a particular haplotype of mouse could be related to a lack of B- or T-cell epitopes or both. The positive serologic results for a given biotype peptide among one or more of the haplotypes of mice indicate that there are B- and T-cell epitopes present in Cl-4, -5, and -6 and in ET-4, -5, and -6. If the Ig locus on which the expressed B-cell antigen receptor (binds B-cell epitope) repertoire is based is invariant, then the abilities to bind B-cell epitopes on TcpA peptides should be the same. Thus, the likely explanation for the lack of, or low, serologic response by a particular haplotype of mouse would be an effect of the Ir gene because of the loss of T-cell epitopes.

To explore further evidence for B-cell epitopes in peptides 4, 5, and 6 of the two biotypes, we performed cross-binding assays (Table 1). We assessed, for example, whether Cl-4-specific antisera could bind the ET-4 peptide, which would suggest common B-cell epitopes. The lengths of common sequences between the classical and El Tor peptides are extensive enough, 7 to 12 amino acids, to provide common linear B-cell epitopes. Based on high-titer responses (homologous system) in their tertiary serum, two mice from each of the haplotype groups were chosen for various peptide combinations. In this comparison, we divided the end point titer obtained in the homologous system by the end point titer obtained in the heterologous system analysis. If the B-cell epitopes for given classical and ET peptides are the same or very similar, the titers for the cross-binding assay should be identical (classical/El Tor and El Tor/classical quotients of 1 to 0.04). If there are no common B-cell epitopes between biotype-equivalent peptides, the titer ratio (classical/El Tor or El Tor/classical) will be 0. If there are one or more cross-reactive B-cell epitopes but the binding of the heterologous peptide-induced sera is lower than that of the homologous system, the titers will be above background but lower than those for the homologous system (classical/El Tor or El Tor/classical quotient ratio of 0.008 to 0.002).

TABLE 1.

Cross-reactivity of B-cell epitopes between classical and El Tor peptides 4, 5 and 6a

| Peptide and haplotype | Mouse | Titer for:

|

ET/Cl | Cl/ET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl peptide | ET peptide | ||||

| Cl-4, H-2a | 401 | 1.56 × 106 | 3.13 × 105 | 0.2 | |

| 402 | 3.13 × 105 | 3.13 × 105 | 1 | ||

| ET-4, H-2a | 1 | 7.81 × 106 | 7.81 × 106 | 1 | |

| 3 | 1.56 × 106 | 7.81 × 106 | 0.2 | ||

| ET-4, H-2b | 24 | 6.25 × 104 | 6.25 × 104 | 1 | |

| 22 | 6.25 × 104 | 6.25 × 104 | 1 | ||

| Cl-4, H-2d | 406 | 1.56 × 106 | 1.25 × 104 | 0.008 | |

| 408 | 7.81 × 106 | 3.13 × 105 | 0.04 | ||

| Cl-4, H-2k | 417 | 1.25 × 104 | 1.25 × 104 | 1 | |

| 419 | 3.13 × 105 | 1.25 × 104 | 0.04 | ||

| ET-5, H-2a | 6 | 0 | 6.25 × 104 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 1.25 × 104 | 0 | ||

| Cl-5, H-2a | 421 | 1.56 × 106 | 0 | 0 | |

| 422 | 7.81 × 106 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ET-5, H-2b | 31 | 0 | 1.25 × 104 | 0 | |

| 32 | 0 | 1.25 × 104 | 0 | ||

| Cl-5, H-2d | 426 | 1.56 × 106 | 3.13 × 105 | 0.2 | |

| 427 | 3.13 × 105 | 1.25 × 104 | 0.04 | ||

| Cl-5, H-2k | 436 | 7.81 × 106 | 0 | 0 | |

| 437 | 3.13 × 105 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cl-6, H-2a | 441 | 7.81 × 106 | 1.25 × 104 | 0.002 | |

| 442 | 1.56 × 106 | 1.25 × 104 | 0.008 | ||

| ET-6, H-2b | 28 | 1.25 × 104 | 6.25 × 104 | 0.2 | |

| 30 | 7.81 × 106 | 1.56 × 106 | 5.0 | ||

| ET-6, H-2d | 44 | 2.50 × 103 | 3.13 × 105 | 0.008 | |

| 50 | 2.50 × 103 | 1.56 × 106 | 0.002 | ||

| Cl-6, H-2d | 452 | 3.13 × 105 | 0 | 0 | |

| 473 | 6.25 × 104 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cl-6, H-2k | 460 | 3.13 × 105 | 0 | 0 | |

| 472 | 7.81 × 106 | 6.25 × 104 | 0.008 | ||

Tertiary sera for two individual mice for selected biotype-specific antiserum peptides were analyzed for reactivity by ELISA. Not all the sera for all the combinations presented in Fig. 2 to 4 were analyzed in this table. End-point titers were calculated for each serum and ratios of titers were calculated for classical antisera against classical peptide or El Tor peptide (Cl/ET) or for El Tor antisera against El Tor peptide or classical peptide (ET/Cl). Ratios of cross-reactivity were calculated by dividing the heterologous titer by the homologous titer. Ratios of 1 to 0.04 were considered indicative of highly cross-reactive sera. Ratios that produced a quotient of 0 were considered descriptive of non-cross-reactive sera. Ratios of >0.04 to 0.002 were considered indicative of low cross-reactivity. Average ratios were calculated for each peptide analyzed and modes were determined for the data set presented in Table 2 (peptide 4, average of 0.55, mode of 1; peptide 5, average of 0.24, mode of 0; peptide 6, average of 0.52, bimodal [0 and 0.008]).

This analysis indicates that peptide 4 is the most cross-reactive, producing an average cross-reactive score of 0.55 and a mode of 1. Peptide 5 was the least cross-reactive peptide, with an average of 0.24 for a cross-reactive score and a mode of 0. Peptide 6 was cross-reactive but not as cross-reactive as peptide 4. The average cross-reactivity score for peptide 6 was 0.52 with a dual mode of 0 or 0.008.

If one examines the peptide-haplotype combinations (Table 1) that were suggestive of the effects of the Ir gene, it is apparent that biotype differences can affect both T- and B-cell epitopes. The Cl-4 H-2a group reveals identity in the cross-reactivity analysis, suggesting that the lack of response is not due to lack of a common B-cell epitope. Since the class II restriction element is the same in these haplotypes, another explanation (effects of the class I Ir gene) is required to explain the lack of a serologic response.

The cross-binding responses to peptide 5 are suggestive of limited or no common B-cell epitopes. The biotype sequences of peptide 5 have more-limited areas for B-cell epitopes because of the significant nature of the amino acid differences between the biotypes of TcpA. The cross-binding score of Cl-5 antisera from H-2d mice is unusual in peptide 5 comparisons, as it indicates near identity (score of 0.2 or 0.04) between Cl-5 and ET-5 for H-2d mouse sera. In particular, the changes Cl-E158 to ET-A158, Cl-K172 to ET-A172, and Cl-D176 to ET-N176 suggest that it would be difficult to maintain B-cell reactivity of peptide 5, thus focusing common B-cell epitopes on sequences in the middle of the peptide. The data in Table 1 suggest that there are not sufficient common sequences in Cl-5 or ET-5 to accommodate Ab binding. Alternatively, the B-cell epitopes that are immunogenic in the different biotypes of TcpA 5 are different.

The differences in the abilities of H-2a and H-2k mice to respond to Cl-6 and ET-6 is likely based on a change in the B-cell epitope due to the amino acid differences between the biotypes. The cross-binding score for these haplotype-peptide combinations is in the middle range, suggesting positive but not optimal binding. The dominant B-cell epitope in response to Cl-6 or ET-6 immunization (H-2a versus H-2k) should not change the class II binding capacity of the epitopes but does alter binding of Abs, suggesting that the B-cell epitope(s) is near the site of amino acid differences between the biotypes which, because of their nature (Cl-D175 to ET-N175, Cl-G189 to ET-T189, and Cl-V195 to ET-T195) would likely be disruptive for Ab binding.

Immune indices of classical and El Tor peptides 4, 5, and 6.

The anti-peptide 4, 5, and 6 responses of mice immunized with classical or El Tor peptides were scored as described in Materials and Methods and are shown in Table 2. The comparisons in Table 2 allow the evaluation of the immunogenicity of classical and El Tor peptides with respect to haplotypes and the relative responsiveness with respect to IgG1 or IgG2a of different haplotypes to classical and El Tor peptides 4, 5, and 6.

The H-2a, H-2d, and H-2k mice, which express both I-Ak/I-Ek and I-Ad/I-Ed in general generate very good responses to classical and El Tor peptides 4, 5, and 6. The response of H-2a mice is on average higher (92.5) than the responses of H-2d (70) or H-2k mice (72.5). The H-2b mice are nonresponders to classical peptides (0) but can respond to ET peptides (27.5) in a fashion intermediate between that of H-2a (37.5), H-2d (20), and H-2k (15) mice. The allelic differences between classical and ET peptides provide B- and T-cell epitopes for the H-2b mice as they can respond to ET-4, -5, or -6.

H-2a, H-2d, and H-2k mice are equally responsive to classical peptides if all IgG subclasses are scored. In all haplotypes of mice, immunization with classical or El Tor peptides induced an IgG1 response that was better than the IgG2a response. IgG2a responses to Cl-4 and ET-4 and Cl-6 and ET-6 were comparable, while the IgG2a responses to Cl-5 and ET-5 were lower. The differential responses of H-2a and H-2k mice are surprising and are not correlated with class II differences but with other H-2 region gene differences (Fig. 2).

If the immunogenicities of biotype-equivalent classical and El Tor peptides across the haplotypes are examined, it is apparent that peptides 6 (97.5) and 4 (92.5), regardless of the biotype, are the most immunogenic if both IgG1 and IgG2a responses are considered. The response to peptide 5 (72.5) is lower and more variable for the individual biotypes of peptides and for the IgG subclasses. Clearly, peptide 5 sequences are less immunogenic in the haplotypes of mice tested, which may correlate with the limited class II isotype that is expressed (I-Ab only).

DISCUSSION

Cholera remains a disease for which a universal, highly effective vaccine is lacking (3, 4). The development of a cholera vaccine must take into account the target population and the current biotype and serotype of the endemic or pandemic organism. The success of the Bordetella pertussis subunit vaccine, which is based in part on the immunogenicity of three colonization factors and their capacity to evoke protective serologic responses, has prompted us to evaluate a similar approach for V. cholerae vaccination (11). The only well-defined colonization factor in cholera infection is TCP although it has been suggested that others have a role (18–21). A complicating factor in the use of TCP as an immunogen is the difficulty in isolating endotoxin-free TcpA from cultured bacteria.

A potential TcpA vaccine that could circumvent the LPS contamination could be based on TCP-derived peptides. TcpA peptides have been generated based on the classical TcpA amino acid sequences that span the C terminus of the TcpA subunit (18). This region of TcpA is defined by a predicted β hairpin turn with a disulfide bond that contains amino acids required for assembly of the pilus and also for interaction with either host cells or cells in the aggregated colony of bacteria (10). Corresponding peptides from regions in El Tor TcpA have not been investigated for their protective effect.

The synthesis of peptides corresponding to regions of TcpA overcomes the problem of purification, but it introduces a new problem: the potential effect of the Ir gene associated with a limited peptide sequence available for class II binding. Effects of the Ir gene are classically defined as lower immunogenicity of a protein that has been linked to the lack of peptide binding to class II molecules and thus to no or poor activation of T-cell help for Ab production. Initial studies suggested that classical peptides 4, 5, and 6 were immunogenic, but these studies did not investigate enough potential class II alleles to determine if the effects of the Ir gene would be problematic. In this study, we clearly demonstrate that the three most common H-2 haplotypes of mice manifest significant effects of the Ir gene with respect to these peptides, as evidenced by different levels of serologic responses in selected TcpA biotype and haplotype combinations. These effects are seen in both the classical and El Tor biotypes. Furthermore, there is a non-class II but H-2-linked effect on the immunogenicities of classical and El Tor peptides. This is seen in the response of H-2a and H-2k mice to peptides 4 or 6. In the peptide 4 system, Cl-4 is immunogenic in mice of both haplotypes, whereas only the H-2a mice respond to ET-4. Similarly, for peptide 6, the responses by H-2a and H-2k mice are similar for Cl-6 but, in this comparison, H-2k mice respond to ET-6 while H-2a mice do not.

The canonical class II peptide binding motifs for several haplotypes are known (2, 5, 14, 23). There are preferred amino acid residues in particular positions of the class II-bound peptide, but they are not strict requirements for binding. Other amino acids in the “gestalt” of the bound peptide-class II interaction interface can account for noncanonical peptide-class II interactions that result in sufficient binding for induction of T cells. Clearly, the loss of an anchor residue resulting from the different TcpA biotype sequence could explain the responses in H-2b mice that we report. The change in biotype sequences and the loss of effect do not explain why mice that express the same class II restriction elements would serologically respond in a similar or identical manner. A possible explanation for this effect is perhaps centered in the class I region of the H-2 locus. The H-2a and H-2k mice differ in this region. H-2a mice are Dd Ld Qa-2a, while H-2k mice are Dk Lk Qa-2b. MHC-I molecules are also associated with effects of the Ir gene. This has been demonstrated by several laboratories and also relates to the binding of peptides that influence the subsequent immune responses. It has been established that immunization of mice with protein antigen can result in B cells that express class I bound with peptides from the immunizing antigen (25). The B cells then become a target for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses that kill the B cells and thus reduce or prevent antibody responses to the immunizing antigen. Thus, we hypothesize that, for ET-4 and ET-6, the differences in class I resulted in presented peptides that make B cells in H-2k and H-2a mice, respectively, targets for CTL-based elimination. Clearly, there are a number of uncharacterized genes, with the percent contributions for these genes in congenic mice being unknown because of the unmapped recombination point. If one eliminates non-immune-related genes as the explanation for the differences in response to ET-4 and CL-6, then class I and Qa-2 differences are both theoretical possibilities. Qa-2 antigens are nonclassical MHC-I molecules with the potential to bind peptides. The Qa-2 antigen is the product of the Ped (preimplantation embryo development) gene and is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked cell surface protein encoded in the Q region of the mouse major histocompatibility region (13). Qa-2+ mice have significantly higher preimplantation embryo cleavage rates both in vivo and in vitro than Qa-2− mice. The importance of this for immune responses is unknown. However, Gould et al. recently presented evidence that Qa-2 can affect selection of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (6). Qa-2 has a complex role in immunobiology. Qa-2 could serve as a restriction element (MHC-like structure with bound peptides) for subsequent interactions with T cells. The Qa-2 region differences between H-2a and H-2k mice are a less likely explanation for the lack of response to ET-6 because theoretically nonpermissive allele Qa-2a is associated with a positive serologic response to that peptide by H-2b mice. However, in the ET-4 system, the nonpermissive allele, if it is Qa-2a, is associated with lack of a response in H-2k mice and very low response in H-2d mice. One would have to postulate two mechanisms for the different responses by H-2a and H-2k mice. Qa-2 effects could account for the lack of peptide 4 responses, and class I differences could account for the lack of a peptide 6 response.

While we have identified effects of the Ir gene for classical and El Tor TcpA peptides, it is apparent that other genes can affect the serologic response as well. The reason that H-2a mice are such good responders is not apparent and is not related to the Ig locus as they share that with H-2k mice. Other non-H-2 genes linked to H-2 may contribute to the differences in serologic responses. Regardless of the explanation for the differences, the effect of the Ir gene associated with the differences in the H-2 regions suggests that vaccine peptides based on classical and El Tor TcpA peptide 4, 5, or 6 may not be universally efficacious in the human population. This may be an overstatement, as the target human population is outbred at the HLA locus. The codominant expression of human class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP might allow more possible targets for classical peptide- and El Tor peptide-based binding. Thus, with more class II alleles present, it may be easier to generate a class II peptide complex to induce T-cell help for antibody production. It is, however, also true that certain proteins contain immunodominant epitopes for induction of responses, and thus, while TcpA peptide 4, 5, or 6 binding may occur at a high frequency, the peptide sequences may not be particularly immunogenic with respect to their ability to be highly expressed and thus able to activate naive T cells. There are two solutions to these issues. The most direct, and one that can take advantage of T-cell memory in the mucosal T-cell pool, would be to link classical and El Tor peptide 4, 5, or 6 to a universal protein carrier for its contribution of T-cell epitopes. A recent development by Alexander et al. could also be used by taking advantage of pan-DR epitopes that could be linked to the TcpA peptide, thus yielding a host (human)-based vaccine design based on known class II binding properties (1). Alternatively, a mixture of TcpA peptides that would more effectively cover the possible sequence solutions to MHC-II binding may be used. These solutions would mitigate the effect of the class II Ir gene but not the possible effect of class I or Qa-2 (perhaps not evident in humans, as no Qa-2 gene has been identified). The solution for the class I-based problem of the classical and El Tor peptide sequences is to clearly identify the TcpA B-cell epitopes within peptides 4, 5, and 6 that are immunogenic and protective and then use minimal B-cell epitopes as haptens associated with a universal carrier.

Clearly, the development of cholera subunit vaccines for humans will need to take into account the route of immunization that induces the most protective isotype. Whether this is secretory IgA or IgG is debatable, but the resolution of this issue may dictate the route and method of immunization with TcpA peptides. We were able to induce IgG as well as IgA (data not shown) via intraperitoneal immunization. While this form of immunization is not practical in humans, other routes such as oral or intranasal routes have been shown to be responsive to immunogens by generating IgG as well as serum IgA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants to R.K.T. (AI 25096) and W.F.W. (AI 47373).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander J, Fikes J, Hoffman S, Franke E, Sacci J, Appella E, Chisar F V, Guidotti L G, Chesnut R W, Livingston B, Sette A. The optimization of helper T lymphocyte (HTL) function in vaccine development. Immunol Res. 1998;18:79–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02788751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartnes K, Leon F, Briand J P, Travers P J, Hannestad K. A novel first primary anchor extends the MHC class II I-Ad binding motif to encompass nine amino acids. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1185–1193. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.8.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bern C, Martine J, deZoysa I, Glass R I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull W H O. 1992;70:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournier J M, Villeneuve S. Cholera update and vaccination problems. Med Trop. 1998;58(Suppl. 2):32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fremont D H, Monnaie D, Nelson C A, Hendrickson W A, Unanue E R. Crystal structure of I-Ak in complex with a dominant epitope of lysozyme. Immunity. 1998;8:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould D G, Augustine M M, Fragoso G, Scitto E, Stroynowski I, Van Kaer L, Schust D J, Ploegh H, Janeway C A. Qa-2-dependent selection of CD8alpha/alpha T cell receptor alpha/beta (+) cells in murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1521–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall R H, Losonsky G, Silveira A P, Taylor R K, Mekalanos J J, Witham N D, Levine M M. Immunogenicity of Vibrio cholerae O1 toxin-coregulated pili in experimental and clinical cholera. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2508–2512. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2508-2512.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrington D A, Hall R H, Losonsky G, Mekalanos J J, Taylor R K, Levine M M. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1487–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaper J B, Morris J G, Jr, Levine M M. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirn T J, Lafferty M J, Sandoe C M P, Taylor R K. Delineation of pilin domains required for bacterial association into microcolonies and intestinal colonization by Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:896–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein D L. From pertussis to tuberculosis: what can be learned? Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:S302. doi: 10.1086/313879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDeveitt H O, Sella M. Genetic control of the antibody response. I. Demonstration of determinant-specific differences in response to synthetic poly-peptide antigens in two strains of inbred mice. J Exp Med. 1965;122:517–531. doi: 10.1084/jem.122.3.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McElhinny A S, Kandow N, Warner C M. The expression pattern of the Qa-2 antigen in mouse preimplantation embryos and its correlation with the Ped gen phenotype. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:966–971. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.10.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson C A, Viner N J, Young S P, Petzold S J, Unanue E R. A negatively charged anchor residue promotes high affinity binding to the MHC class II molecule I-Ak. J Immunol. 1996;157:755–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhine J A, Taylor R K. TcpA pilin sequences and colonization requirements for O1 and O139 Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1013–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun D, Mekalanos J J, Taylor R K. Antibodies directed against the toxin-coregulated pilus isolated from Vibrio cholerae provide protection in the infant mouse experimental cholera model. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1231–1236. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun D, Seyer J M, Kovari I, Sumrada R A, Taylor R K. Localization of protective epitopes within the pilin subunit of the Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus. Infect Immun. 1991;59:114–118. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.114-118.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun D, Lafferty M J, Peek J A, Taylor R K. Domains within the Vibrio cholerae toxin coregulated pilin subunit that mediate bacterial colonization. Gene. 1997;192:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tacket C O, Taylor R K, Losonsky G, Lim U, Nataro J P, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Investigation of the role of toxin-coregulated pili and mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin pili in the pathogenesis of Vibrio cholerae O139 infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:692–695. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.692-695.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor R K, Miller V L, Furlong D, Mekalanos J J. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2833–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thelin K H, Taylor R K. Toxin-coregulated pilus, but not mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin, is required for colonization by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor biotype and O139 strains. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2853–2856. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2853-2856.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voss E, Manning P A, Attridge S R. The toxin-coregulated pilus is a colonization factor and protective antigen of Vibrio cholerae El Tor. Microbiol Pathol. 1996;20:141–153. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wall K A, Hu J Y, Currrier P, Southwood, Sette S A, Infante A J. A disease-related epitope of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor. Residues involved in I-Ab binding, self-nonself discrimination, and TCR antagonism. J Immunol. 1994;152:4526–4536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J-Y, Taylor R K, Wade W F. Anti-class II monoclonal antibody-targeted Vibrio cholerae TcpA pilin: modulation of serologic response, epitope specificity, and isotype. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7679–7686. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7679-7686.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yefenof E, Zehavi-Feferman R, Guy R. Control of primary and secondary antibody responses by cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a soluble antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1849–1853. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]