Abstract

Objective:

Preterm birth, any birth < 37 weeks gestation, disproportionally affects Black birthing people and is associated with adverse perinatal and fetal health outcomes. Racism increases the risk of preterm birth, but standardized measurement metrics are elusive. This narrative synthesis examines literature on measures of racial discrimination used in preterm birth research.

Data Sources:

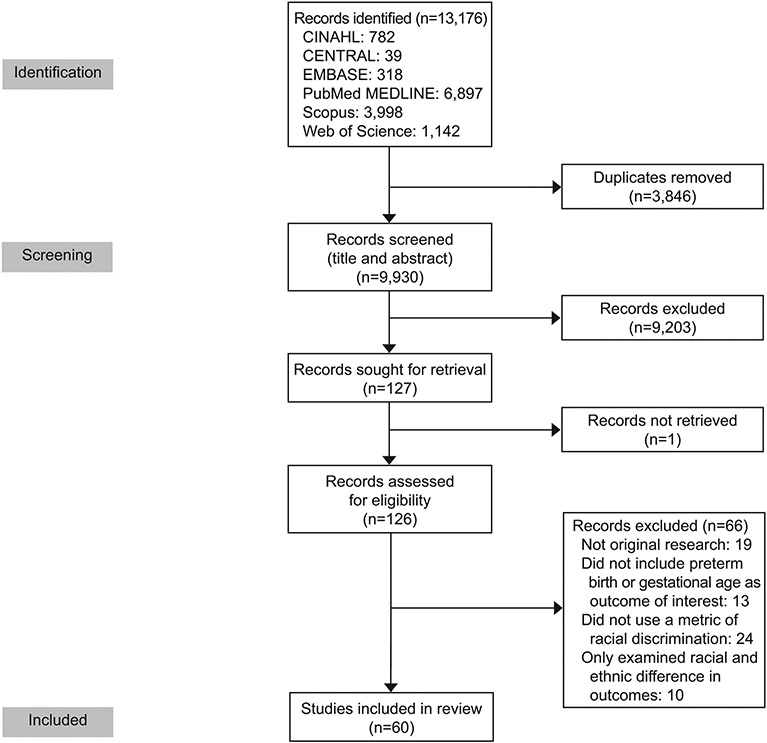

Six databases (CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Web of Science) and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched. Search terms were categorized into three groups (racism terms, measurement terms, preterm birth terms) to identify original research articles that explored associations between racism and preterm birth. English-language, original research articles with US populations were included.

Methods of Study Selection:

Studies were excluded if conducted in only White populations, if only paternal factors were included, or if only racial differences in preterm birth were described. Articles were independently reviewed by two blinded researchers for inclusion at every stage of screening and data extraction; a third reviewer resolved discrepancies.

Tabulation, Integration, and Results:

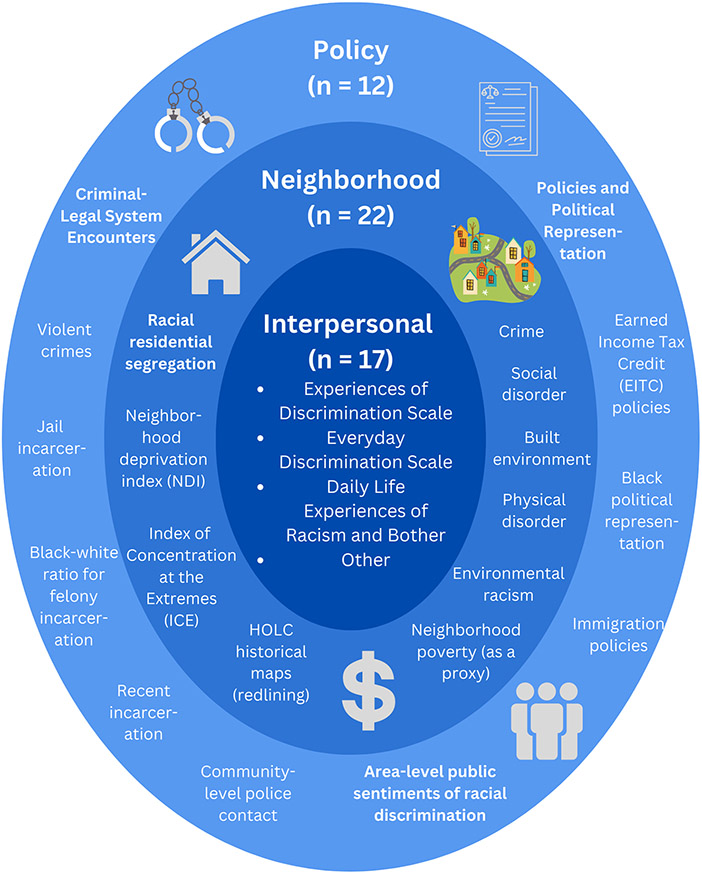

Sixty studies were included in the final analysis. Articles primarily included measures examining interpersonal forms of racism (n=17) through Experiences of Discrimination and Everyday Discrimination scales; neighborhood composition (n=22) with Neighborhood Deprivation Index (NDI) and Index of Concentration and the Extremes (ICE); policy level racism (n = 12) through institutions like residential racial segregation, or policy inequities; or multiple forms (n=9).

Conclusions:

Among studies, assessment methods and application of constructs varied. This heterogeneity poses significant challenges to understanding associations between racial discrimination and preterm birth, and describing potential etiologic pathways of preterm birth, which ultimately hinders development of effective intervention. Strategies to capture multilevel exposures to racism require the development and expansion of metrics that are culturally-inclusive, empirically valid and reliable among Black pregnant populations.

Systematic Review Registration:

PROSPERO, CRD42022327484.

Precis:

Studies of racism and preterm birth use inconsistent, unstandardized metrics of racial discrimination; standard measures should be developed for application in perinatal research.

INTRODUCTION

Black women in the United States experience higher rates of preterm birth compared to White women (14% vs 9%)(1-3), likely influenced by multiple social and structural factors (4-6). During pregnancy, experiences of gendered racism may cause trauma, stress, and disruptions to the physiology of pregnancy (7, 8). Racism has been linked to oxidative stress and antioxidant imbalance that can reduce telomere length in gestational tissues resulting in cellular senescence (9). And, while Kramer and Hogue (10) caution that current literature cannot support direct casual links between racism and preterm birth, they suggest several plausible proximal (maternal inflammation, vascular, and neuroendocrine dysfunction) and distal (health care, genetics, and epigenetics) pathways to this adverse birth outcome due to stress. Thus, there is urgency to both clarify the physiological implications of racism on pregnancy, and to quantify and address racism at multiple levels of perinatal research (11). Without contextualizing one’s adverse birth outcomes in environmental exposures to discrimination, there will be little progress in reducing racial disparities in maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality (12).

A broad call for standardized methods, measures, and approaches to measuring racism and racial discrimination in epidemiologic studies serves as the impetus for the purpose of this work (13). Explorations of racism in preterm birth studies are not new. However, measurement is inconsistent, and there is variability in the forms of racism examined. Racism has been identified in three forms: (1) internalized, (2) interpersonal, and (3) structural (14). To date, preterm birth literature has largely captured individual-level exposure to racism. For instance, perceived discrimination was independently associated with low birthweight, preterm birth, and small for gestational age in an integrated review (15). Among 1,410 Black women with mild to moderate depression, daily experiences of racist microaggressions were significantly associated with preterm birth (6). Consistently worrying about treatment due to race was found to increase risk of preterm birth among another cohort of 2,201 Black women (16). Of the existing reviews that have examined racism in preterm birth (15, 17-19), most have focused on individual forms with the main objective to determine if associations with preterm birth exist. This emphasis on individual-level racism in preterm birth literature, without considering structural discrimination, which is much more pervasive and impactful on access to resources and opportunities, is a disservice to the experiences of Black birthing people. To build towards standardized measures of structural racism and racial discrimination in the field, it is imperative to benchmark how racism is currently assessed in preterm birth research. Therefore, our objective was to conduct a narrative synthesis examining measures of racism in preterm birth studies.

SOURCES

This study was a narrative synthesis of literature examining racism as an exposure and preterm birth (defined as a live birth at <37 weeks completed gestation) as an outcome. This systematic review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID# CRD42022327484).

Six databases (CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Web of Science) and ClinicalTrials.gov were used to identify original research articles, published in English, that measured associations between racism and preterm birth. Databases were searched from March 10, 2022, to March 18, 2022, for articles published from inception to the date of search. Search terms were categorized into three groups to capture articles that used metrics of racism in preterm birth research: racism terms, measurement terms, preterm birth terms (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).

STUDY SELECTION

Articles were included if they: (1) summarized an original research article (2) included preterm birth or gestational age at delivery as an outcome of interest; and (3) measured aggregate or individual-level exposure to racism or racial discrimination. Articles were excluded if they: (1) were restricted to a non-US population (2) included only White race participants; (3) evaluated only paternal (non-birthing people) factors as exposures; or (4) examined racial or ethnic differences in preterm birth without measurement of racism.

Upon completion of searches, all titles and abstracts were uploaded to Covidence, an online systematic review tool (20). At each stage, review was completed by two independent, blinded reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Reasons for exclusion were noted in a full-text review. Data extraction was performed by two independent, blinded study team members; individuals were trained in a protocol to extract data similarly. In cases of conflicts, final data were chosen by a third team member.

Study characteristics extracted included: article title, first author, publication year, DOI, objective, hypothesis, study design and timing, sample size overall and by race or ethnicity, study region and state, and years of data collection. Studies examining preterm birth, defined as all births < 37 weeks gestation, as a primary outcome were included. Secondary birth outcomes included: gestational age (weeks of pregnancy), low birth weight (<2500 grams), birthweight (first weight of infant after birth), small for gestational age (birthweight < 10th percentile for gestational age), and infant mortality (infant death occurring <1 year).

For each metric of racial discrimination, we extracted: name of the metric, original publication of metric, investigator-written description, dataset used, level of racism (perceived, neighborhood, structural), dimension(s) of racism (housing, disorder, education, employment, socioeconomic status, criminal legal, psychological, other), and previous assessments of validity or reliability. The study team prepared a narrative summary of the 60 included articles by level and dimension of the metric of racial discrimination.

RESULTS

The literature search resulted in 13,176 articles (Figure 1); 3,846 were deemed duplicates and removed. Of the remaining 9,330 titles and abstracts that were screened, 9,203 were excluded for not including measures of racism or for not reporting preterm birth as an outcome. The remaining 127 articles were included for full-text review. Sixty-six articles were excluded during full-text review: 19 were not original research articles, 13 did not include preterm birth as an outcome, 24 did not discuss racial discrimination, 10 only considered racial disparities and did not explicitly measure racism (Figure 1). Data were extracted from the remaining 60 articles; 85 metrics of racial discrimination were counted.

Figure 1.

Articles included are displayed by primary exposure measures examining neighborhood composition (n=22), interpersonal (perceived or self-reported) (n=17), policy level inequities (n=12), or multiple forms (n=9) (Figure 2). Of the nine that examined multiple levels of racism, one considered perceived racism and structural forms through neighborhood composition, seven measured neighborhood composition only as a form of structural racism, and one included metrics of all three levels.

Figure 2.

Twenty-two articles (36.7%) (21-42) considered exclusively neighborhood factors, and six of these articles used more than one metric to assess neighborhood measures. In total, 40 metrics of neighborhood level racial discrimination were used (Table 1). Studies of neighborhood composition included dimensions of housing, socioeconomic status, social disorder, built environment, and general environment.

Table 1:

Neighborhood Composition as a Form of Structural Racism in Preterm Birth Studies

| Dimension(s) | Metric of Racism | Metric Reference |

First Author, Year | Study design | Region | State | Racial composition | Dataset to generate metric |

Study team subjective rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing; Disorder; Built environment | 4-factor neighborhood characteristics model* | Evenson 2009; Laraia 2006 | Vinikoor-Imler 2011 † ‡ | Retrospective cohort study | South | NC | Black and white | 2000 Census | Medium |

| Criminal-legal | Annual county-level jail incarceration rate | Jahn 2020 † | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black and white | Bureau of Justice Statistics Census of Jails and Annual Survey of Jails. | Medium | |

| Built environment | Built environment index | Miranda 2012a; Miranda 2012b; Kroeger 2012 | Anthopolos 2014 † | Retrospective cohort study | South | NC | Black and white | 2008 Duke Community Assessment Project, 2006-2007 Durham PD Crime Analysis Lab; 2008 Durham county tax assessor data | High |

| Environment | California Communities Environmental Health Screening Tool | Padula 2018 | Retrospective cohort study | West | CA | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | CalEnviroScreen 2.0 | High | |

| Criminal-legal | County-level homicide | Mark 2022 | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black, white, and Latine | 1991-2002 FBI UCR | High | |

| Housing | Gi* statistic | Getis & Ord 1992 | Salow 2018 | Retrospective case-control study | Midwest | Multiple | Black only | 2010 Census | Medium |

| Housing; SES | Index of Concentration at the Extremes | Massey 2001; Krieger 2015 | Chambers 2019 † | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | West | CA | Black only | 2011 ACS | High |

| Huynh 2018 † | Cross sectional case-control study | Northeast | NY | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | 2010 ACS, 5 year | High | |||

| Jahn 2020 † | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black and white | 2000 Census; ACS (no year) | Medium | |||

| Shrimali 2020 † | Retrospective cohort study | West | CA | Black, white, and Latine | 1980, 1990, 2000 Census; 2007 ACS, 5 year | High | |||

| Thoma 2019 † | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black and white | 2016 ACS, 5 year | Medium | |||

| Housing; Education; Employment; SES | Neighborhood deprivation index | Messer 2006 | Blebu 2021 | Cross sectional survey | West | CA | Black only | 2010 ACS | Low |

| Janevic 2010 | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | Northeast | NY | None of the above | 2000 Census | High | |||

| Ma 2015 | Retrospective case-control study | South | SC | Black and white | 2000 Census | High | |||

| Messer 2010 | Retrospective case-control study | South | NC | Black and white | 2000 Census | Medium | |||

| O'Campo 2008 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-Site | Multiple | Black and white | 2000 Census | Medium | |||

| Vinikoor-Imler 2011 † ‡ | Retrospective cohort study | South | NC | Black and white | 2000 Census | Medium | |||

| Housing; Education; Employment; SES | Neighborhood deprivation index§ | Messer 2006 | Kramer 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | South | GA | Black, white, and Latine | 1990, 2000 Census; 2005 ACS, 5 year | High |

| Housing; Education; Employment; SES | Neighborhood disadvantage index∥* | Sealy-Jefferson 2017 | Sealy-Jefferson 2019 † | Retrospective cohort study | Midwest | MI | Black only | ACS (no year) | Medium |

| SES | Neighborhood economic trajectories (GINI index) | Cubbin 2020 † | Retrospective cohort study | South | TX | Black and white | 1990, 2000 Census; 2006 ACS, 5 year | Medium | |

| Housing; Disorder; Built environment | Neighborhood environment scales∥* | Mujahid 2007; Echeverria 2004 | Sealy-Jefferson 2016 | Retrospective cohort study | Midwest | MI | Black only | LIFE | High |

| SES | Neighborhood poverty trajectories | Margerison-Zilko 2015 | Cubbin 2020 † | Retrospective cohort study | South | TX | Black and white | 1990, 2000 Census; 2006 ACS, 5 year | Medkum |

| Disorder | Neighborhood quality | Coulton 1996; Elo 2009 | Mendez 2014 † | Retrospective cohort study | Northeast | PA | Black, white, and Latine | SPEAC | High |

| Housing | Neighborhood racial isolation & dissimilarity spatial index | Massey & Denton 1988; Reardon & O'Sullivan 2004 | Kramer 2010 | Retrospective cohort study | National | National | Black and white | 2000 Census | Medium |

| Housing | Neighborhood racial isolation spatial index | Reardon & O’Sullivan 2004 | Anthopolos 2011 | Retrospective cohort study | South | NC | Black amd white | 2000 Census | Medium |

| Housing | Neighborhood racial isolation spatial index | Anthopolos 2011 | Anthopolos 2014 † | Retrospective cohort study | South | NC | Black and white | 2000 Census | High |

| Disorder; Built environment | Perceived physical and social residential environment ∥* | Sealy-Jefferson 2015 | Sealy-Jefferson 2019 † | Retrospective cohort study | Midwest | MI | Black only | LIFE | Medium |

| SES | Poverty Exposure | Massey & Fischer 2000 | Britton 2013 † ¶ | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black and Latine | 2000 Census | Medium |

| Housing | Residential segregation | Massey & Denton 1988 | Bell 2006 | Cross sectional survey | National | National | Black only | 2000 Census | Medium |

| Britton 2013 † ¶ | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black and Latine | 2000 Census | Medium | |||

| Chambers 2018†# | Cross sectional case-control study | West | CA | Black and white | 2009 ACS, 5 year | High | |||

| Grady 2010 | Retrospective cohort study | South | MI | Black and other | 2000 Census | Medium | |||

| Margerison-Zilko 2017 † | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black only | 2010 Census | Medium | |||

| Osypuk 2008 | Retrospective case-control study | Multi-Site | Multiple | Black and white | 2000 Census | High | |||

| Mendez 2014 † | Retrospective cohort study | Northeast | PA | Black, white, and Latine | 2000 Census | High | |||

| Disorder | Ross Neighborhood Disorder Scale∥* | Ross & Mirowsky 1999 | Dove-Meadows 2020 † | Mixed methods | Midwest | Multiple | Black only | Unnamed study | Medium |

| Housing; Built environment | Neighborhood physical characteristics | Zuberi 2016 † | Retrospective ecological study | Northeast | PA | None of the above | PNCIS, USPS, HUD | Low | |

| Housing; Disorder | Neighborhood social environment | Zuberi 2016 † | Retrospective ecological study | Northeast | PA | None of the above | ACS (no year); PNCIS | Low | |

| Environment | Urban green space | Tvina 2021 | Retrospective case-control study | Midwest | WI | Black only | National Land Cover Database | High | |

| Housing; Built environment | Tax foreclosure | Sealy-Jefferson 2019 † | Retrospective cohort study | Midwest | MI | Black only | Wayne County Treasurer; Data Driven Detroit | Medium |

indicates metric has been assessed for reliability

indicates study listed more than once

indicates PTB as secondary outcome

indicates metric referenced was modified by investigator

indicates metric has been assessed for validity

indicates very preterm birth (VPTB) as primary outcome

indicates gestational age as primary outcome

Seven articles (11.7%)(23, 25, 27, 35, 43-45) included measures of neighborhood racial segregation through Massey & Denton’s 1988 conceptualization of five distinct measures: clustering, centralization, evenness, exposure, and concentration (46). Segregation was also approximated through the Neighborhood Racial Isolation Spatial Index, derived from Massey & Denton and expanded by Reardon and O’Sullivan (47). For example, Anthopolos and colleagues (21, 22) approximated a measure of racial segregation based on the regional-scale spatial isolation index (47) and included modifications to account for population interaction within neighborhoods and application to Census block groups (21). These measures were applied at the county or metropolitan area level and included studies that examined Black-White differences using Census data as the primary residential data source.

The Neighborhood Deprivation Index (NDI) proposed by Messer and colleagues (48) developed and standardized an index of contextual variables to examine impacts of neighborhood factors and associated perinatal health outcomes. The NDI incorporates measures of poverty, education, employment, housing, and occupation from Census data through a principal component analysis (PCA). Six studies (10%) deployed the NDI as described in the original proposal and validation (24, 28, 31, 33, 34, 41). For instance, Blebu et al. (24) conducted a PCA to determine how each measure of deprivation contributed to variance in the sample and created a z-score transformed index score, with higher scores representing higher neighborhood deprivation. Modified versions of the NDI were also included. Kramer, Dunlap & Hogue (30) performed the suggested analysis of eight measures that deviated from the recommended and included prevalence of “female-headed households” and “adults with management or professional positions.”

The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) introduced by Massey in 2001 (49) quantifies measures of concentrated privilege and deprivation by approximating geographic distributions of income inequality by race. Krieger and colleagues (50) expanded Massey’s original concept to three scores: ICE race, ICE income, and ICE race + income. ICE has been applied to perinatal outcomes. For example, Chambers et al. (43) included ICE as an approximation of structural racism in a California birth cohort, creating scores that ranged from −1 to 1 and grouping participants into quintiles ranging from least to most privileged; women living in least privileged zip codes were more likely to experience preterm birth compared to women living in the most privileged zip codes, and effects remained after adjusting for maternal factors (43). Five studies (8.3%) used the ICE in their study as a primary exposure and approximation for neighborhood and structural racism (43, 51-54).

The most frequent dimension of structural racism assessed was housing. The most common metric was the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE), used by five investigators. Other studies operationalized redlining and residential segregation policies by combining Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) historical maps (55-57) or Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) records (45, 58) with contemporary birth data. Three of these studies were conducted with state-level data from the Northeast.

Neither socioeconomic status nor poverty alone is a metric of racism. Still, three studies (5.0%) exclusively evaluated neighborhood poverty as a proxy for racial discrimination via area and neighborhood deprivation. Cubbin et al. (26) examined trajectories of neighborhood wealth and poverty in relationship to Black-White disparities in preterm birth over time. They calculated a Gini index, a measure of neighborhood income inequality, to categorize census tracts into four poverty trajectories (59). Salow and colleagues (37) calculated a Getis-Ord Gi* statistic (60), a spatial z-score that estimates how racial composition of a neighborhood differs from a regional mean, to examine associations of segregation among non-Hispanic Black women with diagnosed preterm birth from medical records review. .(60)Britton et al. (25) examined the influence of racial segregation on preterm birth and determine differences across geographic exposures to poverty by calculating the natural log of population size and median household income (in $1000s) and examining the Black or Hispanic poverty rate.

Six studies (10.0%) described social disorder as an indicator of neighborhood-level racial discrimination (38, 39, 41, 42, 45, 61). Mendez and colleagues (45) examined residential redlining, crime and safety, physical disorder, and social disorder in association with preterm birth. Of the six studies describing social disorder, four of the scales also included the built environment. Vinikoor-Imler et al. (41) described social disorder and built environment through Census block level indices of several domains: Physical Incivilities, Walkability, Decoration, Arterial or Thoroughfare, and Social Spaces. Other studies used objective neighborhood physical characteristics like property maintenance, housing vacancy, social spaces, and tax foreclosure to describe the built environment (22, 41, 42). Sealy-Jefferson et al. (39) examined the influence of neighborhood tax foreclosures - considered a measure of social disorder - on longitudinal risk of preterm birth among African American women; these researchers also implemented a metric of participant-reported perceptions of neighborhood characteristics: walkability, access to healthy foods, safety, and social cohesion (38, 39). Two studies described environmental racism in association with preterm birth. Padula et al. (36) used the California Communities Environmental Health Screening Tool to regress individual pollution indicators to birth outcomes in Fresno County. Tvina et al. (40) quantified proximity of urban green space to maternal residence in Milwaukee.

Seventeen articles (28.3%) (4, 6, 16, 45, 62-74) examined forms of individual or interpersonal discrimination as a risk factor for preterm birth (Table 2). Three articles used two metrics to assess interpersonal racism. Most commonly used were the validated Experiences of Discrimination Scale (75) and the Everyday Discrimination Scale (76). Additional scales used were the Daily Life Experiences of Racism and Bother (77), the John Henryism Active Coping Scale (78), the Perceived Racism Scale (79), Racism and Life Experiences Scale and the Racism-Related Experiences Scale (80). Short items from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Survey (PRAMS) inquired whether the respondent had been upset by experiences of racism; three studies used these indicators (26, 62, 63). One study cited use of nine questions measuring racial discrimination included in the 1997 Black Women’s Health Study (81). Chronic worry about race related treatment were included in two studies (16, 26). Nine studies included Black participants only. Studies were often cross-sectional, and about half contained data from prospective cohort studies. Studies were most frequently conducted at the state-level.

Table 2:

Self-reported Racial Discrimination in Preterm Birth Studies

| Dimension | Metric of Racism | Metric Reference |

First Author, Year |

Study design | Region | State | Racial composition | Dataset to generate metric |

Study team subjective rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | Daily Life Experiences of Racism and Bother∥* | Bond 2008 | Slaughter-Acey 2016 | Retrospective cohort study | Midwest | MI | Black only | LIFE | High |

| Psychosocial | Everyday Discrimination Scale∥* | Williams 1997 | Fryer 2020 | Secondary analysis of prospective cohort | Multi-Site | Multiple | Black and Latine | CCHN | Medium |

| Mendez 2014 † | Retrospective cohort study | Northeast | PA | Black, white, and Latine | SPEAC | High | |||

| Psychosocial | Everyday Discrimination Scale§ | Dominguez 2008 | Daniels 2020 | Cross sectional survey | West | CA | Black only | AAWHHS | Low |

| Psychosocial | Everyday Discrimination Scale§ | Williams 1997; Krieger 2005 | Dominguez 2008 ‡ | Prospective cohort study | West | CA | Black and white | Unnamed study | Low |

| Psychosocial | Experiences of Discrimination∥* | Krieger 1990; Krieger 2005 | Dove-Meadows 2020 † | Mixed methods | Midwest | Multiple | Black only | Unnamed study | Medium |

| Giurgescu 2012 | Cross sectional case-control study | Midwest | IL | Black only | Unnamed study | Low | |||

| Grobman 2018 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-Site | Multiple | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | nuMoM2b | Medium | |||

| Psychosocial | Experiences of Discrimination§ | Krieger 1990; Krieger 2005 | Dole 2004 | Prospective cohort study | South | NC | Black and white | PINS | Low |

| Public sentiment | Implicit Association Test | Greenwald 1998 | Orchand 2017 | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black and white | Project Implicit | Low |

| Psychosocial | John Henryism Active Coping Scale | James 1996 | Wheeler 2018 † | Secondary analysis of prospective cohort | South | NC | Black and white | HPHB | Low |

| Psychosocial | Life Experiences Survey§ | Sarason 1978 | Dole 2003 | Prospective cohort study | South | NC | Black, white, and none of the above | PINS | Low |

| Psychosocial | Perceived Racism Scale | Dole 2004 | Wheeler 2018 † | Secondary analysis of prospective cohort | South | NC | Black and white | HPHB | Low |

| Psychosocial | Perceived Racism Scale§ | McNeilly 1996 | Rankin 2011 | Cross sectional case-control study | Midwest | IL | Black only | Unnamed study | Low |

| Psychosocial | PRAMS: upset by experiences of racism | Barber 2021 | Cross sectional survey | South | VA | Black, white, and none of the above | PRAMS | Low | |

| Psychosocial | Bower 2018 | Cross sectional survey | Multi-Site | Multiple | Black only | PRAMS | Low | ||

| Psychosocial | Kim 2020† | Cross sectional survey | West | WA | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | PRAMS | Medium | ||

| Psychosocial | Racism and Lifetime Experiences Scale (RALES)∥* | Harrell 1997 | Misra 2010 † | Qualitative | South | MD | Black only | Unnamed study | Medium |

| Psychosocial | Racism-Related Experiences (RRE) Scale | Harrell 1997 | Misra 2010 † | Qualitative | South | MD | Black only | Unnamed study | Medium |

| Psychosocial | 1997 BWHS questionnaire | Rosenberg 2002 | Cross sectional survey | National | National | Black only | BWHS | Low | |

| Psychosocial | Chronic worry about race-based unfair treatment | Braveman 2017 | Cross sectional survey | West | CA | Black and white | CA MIHA | Low | |

| Psychosocial | Race-specific chronic stress index | Kim 2020† | Cross sectional survey | West | WA | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | PRAMS | Medium |

indicates metric has been assessed for reliability

indicates study listed more than once

indicates PTB as secondary outcome

indicates metric referenced was modified by investigator

indicates metric has been assessed for validity

indicates very preterm birth (VPTB) as primary outcome

indicates gestational age as primary outcome

Structural policies were categorized into three themes: criminal-legal system encounters, public sentiment, and policy and political representation (Table 3). “Criminal-legal system encounters” considered racial inequities in policing, jails, prisons, and courts as predictors of preterm birth. “Public sentiment” describes novel, internet-based measures of racial zeitgeist that were associated with preterm birth. “Policy and political representation” features studies that considered analyses of legislation or racial composition of political power as correlates of preterm birth.

Table 3:

Policy and Governmental Practices as Forms of Structural Racism in Preterm Birth Studies

| Dimension(s) | Metric of Racism | Metric Reference |

First Author, Year |

Study design | Region | State | Racial composition | Dataset to generate metric | Study team subjective rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal-legal | Annual county-level jail incarceration rate | Jahn 2020 † | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black and white | Bureau of Justice Statistics Census of Jails and Annual Survey of Jails. | Medium | |

| Policy | Earned income tax credit | Markowitz 1982 | Komro 2019 # | Quasi-experimental difference-in differences | National | National | Black and white | EITC policies | Medium |

| Criminal-legal | Incarceration prevalence | Dyer 2019 | Cross sectional case-control study | South | LA | Black only | Vera Institute of Justice | Low | |

| Public sentiment | Internet query-based area racism | Stephens-Davidowitz 2014; Chae 2015 | Chae 2018 | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black only | Google Trends at Designated Market Area | Low |

| Housing | HOLC grades | Hollenbach 2021 | Retrospective Cohort study | Northeast | NY | None of the above | 1940s HOLC | High | |

| Housing | HOLC grades | Krieger 2020 | Retrospective Cohort study | Northeast | NY | Black, white, Latine, amd Asian | 1938 HOLC | High | |

| Housing | HOLC grades | Aaronson 2019; Jacoby 2018 | Nardone 2020 | Retrospective Cohort study | West | CA | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | 1940s HOLC | High |

| Housing; SES | Index of Concentration at the Extremes | Massey 2001; Krieger 2015 | Chambers 2019 † | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | West | CA | Black only | 2011 ACS | High |

| Huynh 2018 † | Cross sectional case-control study | Northeast | NY | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | 2010 ACS, 5 year | High | |||

| Jahn 2020 † | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black and white | 2000 Census; ACS (no year) | Medium | |||

| Shrimali 2020 † | Retrospective Cohort study | West | CA | Black, white, and Latine | 1980, 1990, 2000 Census; 2007 ACS, 5 year | High | |||

| Thoma 2019 † | Retrospective case-control study | National | National | Black and white | 2016 ACS, 5 year | Medium | |||

| Criminal-legal | Judicial treatment | Lukachako 2014 | Chambers 2018†# | Cross sectional case-control study | West | CA | Black and white | 2012 Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice | High |

| Criminal-legal | Police contact | Hardeman 2021 | Cross sectional Cohort study | Midwest | MN | Black and white | City of Minneapolis Police Incident Report | High | |

| Policy | Political participation: elected office | Lukachako 2014 | Chambers 2018†# | Cross sectional case-control study | West | CA | Black and white | 2016 county board of supervisor website | High |

| Policy | Political participation: representation | LaVeist 1993 | Margerison-Zilko 2017 † | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black only | City council sites | Medium |

| Criminal-legal | Violent crimes; Neighborhood deprivation index | Messer 2006 | Messina 2013 | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics; crime data | South | GA | Black, white, and none of the above | Atlanta area crime data; GA vital statistics | High |

| Criminal-legal | PRAMS: Criminal justice involvement | Dallaire 2018 | case-control study | South | VA | Black and none of the above | PRAMS | Medium | |

| Housing | Redlining index | Mendez 2013 | Matoba 2019 | cross-sectional, retrospective population-based study | Midwest | IL | Black only | 1990-1995 HMDA | High |

| Housing | Residential redlining | Mendez 2011 | Mendez 2014 † | Retrospective Cohort study | Northeast | PA | Black and Latine | HMDA | High |

| Policy; Other: immigration | State immigrant policies (inclusive and criminalizing) | Sudhinaraset 2021 | Retrospective analysis of vital statistics | National | National | Black, white, Latine, and Asian | Immigration policies | High | |

| Public sentiment | State-level Twitter sentiments | Sanders 2011 | Nguyen 2018 | Cross-sectional analysis of vital statistics | National | National | None of the above | Twitter API | Low |

indicates metric has been assessed for reliability

indicates study listed more than once

indicates PTB as secondary outcome

indicates metric referenced was modified by investigator

indicates metric has been assessed for validity

indicates very preterm birth (VPTB) as primary outcome

indicates gestational age as primary outcome

Six studies considered encounters with the criminal-legal system as a form of structural racism. Messina and Kramer (82) examined area violent crimes in a city by Census block and vital records of preterm birth from 1989-2006. Two studies considered associations between jail incarceration and preterm birth, one nationwide and one in Louisiana (52, 83). Chambers et al. (43) defined judicial treatment as county-level ratio of Black to white people incarcerated for a felony. Dallaire et al. (84) investigated how recent incarceration of a birthing parent or partner was associated with preterm birth. Hardeman et al. (85) considered community-level police contact in Minneapolis as an exposure to preterm birth. Two studies used nationwide internet-based data sources to approximate area-level public sentiments of racial discrimination and associations with preterm birth (86, 87).

Policy-level associations with preterm birth were considered by four studies. State-level earned income tax credit (EITC) policies (88) and immigration policies (89) were operationalized as indicators of racism, and both articles used a national sample. Black political representation was assessed by two studies; Chambers et al. (43) created a ratio of Black to White individuals elected to a county’s board, while Margerison-Zilko et al. (44) created a ratio of percent Black city council members to percent Black voting-age residents in a city.

DISCUSSION

Measures varied widely in constructs used to define “racism.” Most commonly, literature utilizes metrics of neighborhood-level factors as a form of structural racism in association with preterm birth. Least commonly, literature considers policy measures and associations with preterm birth.

Methodological heterogeneity in exposure measurement, regardless of racial composition of a study, presents challenges to comprehensively understanding the impact of racism on preterm birth. Previous reviews have found associations between specific measures of discrimination and preterm birth. Crawford et al. (19) conducted a scoping review of 13 articles associating racial microaggressions and perinatal health outcomes; they found inconsistencies in definitions and measures of microaggressions. Kyung Lee et al. (90) examined 12 studies of redlined vs non-redlined neighborhoods and various adverse health outcomes and found significant associations with preterm birth. Mehra et al. (17) reviewed 42 studies of racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes where 18 measured preterm birth; authors found segregation measures varied widely. Ncube et al. (91) examined associations of neighborhood context with preterm birth and low birthweight, and determined that metrics of neighborhood disadvantage comprised of poverty, deprivation, racial residential segregation, racial composition, and crime. Of note, only seven studies identified were used in a meta-analysis because of variations in the racial composition of the included studies. Building on previous research, this current review uniquely focuses on the measures of racism across multiple domains.

No singular metric is likely to capture all sources or experiences with racism a birthing individual may face. Several investigators have suggested epidemiologic studies integrate multiple metrics across several domains to better measures of racism (13, 92, 93). In our subjective assessment, highly effective articles incorporated multiple measures across two or more domains to capture experiences of structural racism. Recently, ICE has emerged as the preferred measure to approximate structural racism in perinatal research as it incorporates multiple factors of race, income, and race + income. The use of ICE, in conjunction with other measures of structural racism (e.g., redlining) may strengthen a comprehensive assessment of structural racism in epidemiologic studies of preterm birth. A combination of metrics is likely necessary to thoroughly record experiences and environments of racism and its relation to preterm birth. Further, consensus on optimal metrics would improve comparability of research findings. For example, a standardized battery of validated and reliable self-report questionnaires to assess all three levels of racial discrimination – in conjunction with racial discrimination indices constructed from survey or Census data – may be ideal. Future efforts must identify valid and reproducible measures of racism, as standard metrics would benefit various studies of preterm birth and perinatal health.

Complexities of pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes must be acknowledged, as there is no single pathway. Kramer and Hogue (10) showed no consensus on how perceived stress from racism impacted mechanisms that in turn impacted preterm birth. Thus, research must advance methodological and analytic approaches to integrate multiple levels of social, environmental, and individual variables to describe impacts on pregnancy physiology and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes. Importantly, researchers must consider structural factors that impact perinatal health and move away from solely including race and ethnicity a covariate or effect modifier.

As with any review, bias may be introduced throughout article evaluation. To reduce bias, checkpoints were integrated to allow primary investigators with content expertise to review article inclusion.

Characteristics of studies (eg: geographic location, study design, racial composition) varied widely and were largely not generalizable or comparable. Many studies used self-reported survey measures as primary exposures; however, over half (n=34) assessed structural racism through neighborhood or environmental measures directly captured from publicly available sources. As notated as a limitation in another review (15), authors often used racism and discrimination interchangeably. It is understood that discrimination is a measurable conduit of racism, but does not broadly capture the multiple forms and levels within which racism permeates (14).

Racism is a known but inconsistently measured risk factor for preterm birth and assessment methods vary. This heterogeneity poses significant challenges to comprehensively describing the etiology of preterm birth and ultimately hinders effective intervention. Fully capturing impacts of racism may require multiple measures at multiple levels. Further, it is prudent to build consensus on optimal measures for consistency and comparability across perinatal research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Contributors: The authors thank Camillia Comeaux, Blanca Garcia-Silva, and Honorine Uwimana for their assistance in screening articles for this review.

Funding:

This work was funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities 3R01MD013797-03S1 and L60 MD015553 to Ashley V. Hill.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Contributor Information

Phoebe Balascio, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh.

Mikaela Moore, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh.

Megha Gongalla, Department of Sociology, College of Liberal Arts, Temple University.

Annette Regan, School of Nursing and Health Professions, University of San Francisco.

Sandie Ha, Department of Public Health, Health Science Research Institute, University of California Merced

Brandie D. Taylor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Basic Science and Translational Research, University of Texas Medical Branch.

Ashley V. Hill, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):366–73. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holdt Somer SJ, Sinkey RG, Bryant AS. Epidemiology of racial/ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(5):258–65. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grobman WA, Parker CB, Willinger M, Wing DA, Silver RM, Wapner RJ, et al. Racial Disparities in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Psychosocial Stress. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):328–35. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell EA. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(2):387–99. doi: 10.1097/grf.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slaughter-Acey JC, Sealy-Jefferson S, Helmkamp L, Caldwell CH, Osypuk TL, Platt RW, et al. Racism in the form of micro aggressions and the risk of preterm birth among black women. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(1):7–13.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill AV, Perez-Patron M, Tekwe CD, Menon R, Hairrell D, Taylor BD. Chlamydia trachomatis is associated with medically indicated preterm birth and preeclampsia in young pregnant women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. doi: 10.1097/olq.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sampath A, Maduro G, Schillinger JA. Infant Deaths Due To Herpes Simplex Virus, Congenital Syphilis, and HIV in New York City. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillippe M. Telomeres, oxidative stress, and timing for spontaneous term and preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer MR, Hogue CR. What causes racial disparities in very preterm birth? A biosocial perspective. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:84–98. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–63. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonney EA, Elovitz MA, Mysorekar IU. Diversity is essential for good science and reproductive science is no different: a response to the recent formulation of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Pregnancy Think-Tank. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(6):950–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring Structural Racism: A Guide for Epidemiologists and Other Health Researchers. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2021;191(4):539–47. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. American journal of public health. 2000;90(8):1212–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alhusen JL, Bower KM, Epstein E, Sharps P. Racial Discrimination and Adverse Birth Outcomes: An Integrative Review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(6):707–20. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braveman P, Heck K, Egerter S, Dominguez TP, Rinki C, Marchi KS, et al. Worry about racial discrimination: A missing piece of the puzzle of Black-White disparities in preterm birth? PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehra R, Boyd LM, Ickovics JR. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;191:237–50. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giurgescu C, McFarlin BL, Lomax J, Craddock C, Albrecht A. Racial discrimination and the black-white gap in adverse birth outcomes: a review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(4):362–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford AD, Darilek U, McGlothen-Bell K, Gill SL, Lopez E, Cleveland L. Scoping Review of Microaggression as an Experience of Racism and Perinatal Health Outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2022;51(2):126–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babineau J Product review: Covidence (systematic review software). Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association/Journal de l'Association des bibliothèques de la santé du Canada. 2014;35(2):68–71. doi: 10.5596/c14-016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthopolos R, James SA, Gelfand AE, Miranda ML. A spatial measure of neighborhood level racial isolation applied to low birthweight, preterm birth, and birthweight in North Carolina. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2011;2(4):235–46. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anthopolos R, Kaufman JS, Messer LC, Miranda ML. Racial residential segregation and preterm birth: built environment as a mediator. Epidemiology. 2014;25(3):397–405. doi: 10.1097/ede.0000000000000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ, Almgren GR, Mayer JD, Huebner CE. Birth outcomes among urban African-American women: a multilevel analysis of the role of racial residential segregation. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3030–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blebu BE. Neighborhood Context and the Nativity Advantage in Preterm Birth among Black Women in California, USA. J Urban Health. 2021;98(6):801–11. doi: 10.1007/s11524-021-00572-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Britton ML, Shin H. Metropolitan residential segregation and very preterm birth among African American and Mexican-origin women. Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cubbin C, Kim Y, Vohra-Gupta S, Margerison C. Longitudinal measures of neighborhood poverty and income inequality are associated with adverse birth outcomes in Texas. Soc Sci Med. 2020;245:112665. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grady SC. Racial residential segregation impacts on low birth weight using improved neighborhood boundary definitions. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2010;1(4):239–49. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janevic T, Stein CR, Savitz DA, Kaufman JS, Mason SM, Herring AH. Neighborhood deprivation and adverse birth outcomes among diverse ethnic groups. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(6):445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer MR, Cooper HL, Drews-Botsch CD, Waller LA, Hogue CR. Metropolitan isolation segregation and Black-White disparities in very preterm birth: a test of mediating pathways and variance explained. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer MR, Dunlop AL, Hogue CJ. Measuring women's cumulative neighborhood deprivation exposure using longitudinally linked vital records: a method for life course MCH research. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(2):478–87. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma X, Fleischer NL, Liu J, Hardin JW, Zhao G, Liese AD. Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth: an application of propensity score matching. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mark NDE, Torrats-Espinosa G. Declining violence and improving birth outcomes in the US: Evidence from birth certificate data. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messer LC, Oakes JM, Mason S. Effects of socioeconomic and racial residential segregation on preterm birth: a cautionary tale of structural confounding. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):664–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Campo P, Burke JG, Culhane J, Elo IT, Eyster J, Holzman C, et al. Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth among non-Hispanic Black and White women in eight geographic areas in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(2):155–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Are racial disparities in preterm birth larger in hypersegregated areas? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(11):1295–304. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padula AM, Huang H, Baer RJ, August LM, Jankowska MM, Jellife-Pawlowski LL, et al. Environmental pollution and social factors as contributors to preterm birth in Fresno County. Environ Health. 2018;17(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0414-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salow AD, Pool LR, Grobman WA, Kershaw KN. Associations of neighborhood-level racial residential segregation with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(3):351.e1-.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sealy-Jefferson S, Giurgescu C, Slaughter-Acey J, Caldwell C, Misra D. Neighborhood Context and Preterm Delivery among African American Women: the Mediating Role of Psychosocial Factors. J Urban Health. 2016;93(6):984–96. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0083-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sealy-Jefferson S, Misra DP. Neighborhood Tax Foreclosures, Educational Attainment, and Preterm Birth among Urban African American Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6). doi: 10.3390/ijerph16060904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tvina A, Visser A, Walker SL, Tsaih SW, Zhou Y, Beyer K, et al. Residential proximity to tree canopy and preterm birth in Black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3(5):100391. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vinikoor-Imler LC, Messer LC, Evenson KR, Laraia BA. Neighborhood conditions are associated with maternal health behaviors and pregnancy outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(9):1302–11. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuberi A, Duck W, Gradeck B, Hopkinson R. Neighborhoods, race, and health: Examining the relationship between neighborhood distress and birth outcomes in Pittsburgh. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2016;38(4):546–63. doi: 10.1111/juaf.12261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chambers BD, Baer RJ, McLemore MR, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Using Index of Concentration at the Extremes as Indicators of Structural Racism to Evaluate the Association with Preterm Birth and Infant Mortality-California, 2011-2012. J Urban Health. 2019;96(2):159–70. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0272-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Margerison-Zilko C, Perez-Patron M, Cubbin C. Residential segregation, political representation, and preterm birth among U.S.- and foreign-born Black women in the U.S. 2008–2010. Health Place. 2017;46:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane JF. Institutional racism, neighborhood factors, stress, and preterm birth. Ethn Health. 2014;19(5):479–99. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.846300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massey DS, Denton NA. The dimensions of residential segregation. Social forces. 1988;67(2):281–315. doi: 10.2307/2579183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reardon SF, O’Sullivan D. Measures of spatial segregation. Sociological methodology. 2004;34(1):121–62. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00150.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, Eyster J, Holzman C, Culhane J, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1041–62. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massey DS. The age of extremes: concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography. 1996;33(4):395–412; discussion 3-6. doi: 10.2307/2061773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public Health Monitoring of Privilege and Deprivation With the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huynh M, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G, Waterman PD, et al. Spatial social polarization and birth outcomes: preterm birth and infant mortality - New York City, 2010-14. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(1):157–66. doi: 10.1177/1403494817701566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jahn JL, Chen JT, Agénor M, Krieger N. County-level jail incarceration and preterm birth among non-Hispanic Black and white U.S. women, 1999-2015. Soc Sci Med. 2020;250:112856. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shrimali BP, Pearl M, Karasek D, Reid C, Abrams B, Mujahid M. Neighborhood Privilege, Preterm Delivery, and Related Racial/Ethnic Disparities: An Intergenerational Application of the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(5):412–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thoma ME, Drew LB, Hirai AH, Kim TY, Fenelon A, Shenassa ED. Black-White Disparities in Preterm Birth: Geographic, Social, and Health Determinants. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(5):675–86. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hollenbach SJ, Thornburg LL, Glantz JC, Hill E. Associations Between Historically Redlined Districts and Racial Disparities in Current Obstetric Outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2126707. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nardone AL, Casey JA, Rudolph KE, Karasek D, Mujahid M, Morello-Frosch R. Associations between historical redlining and birth outcomes from 2006 through 2015 in California. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krieger N, Van Wye G, Huynh M, Waterman PD, Maduro G, Li W, et al. Structural Racism, Historical Redlining, and Risk of Preterm Birth in New York City, 2013-2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):1046–53. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matoba N, Suprenant S, Rankin K, Yu H, Collins JW. Mortgage discrimination and preterm birth among African American women: An exploratory study. Health Place. 2019;59:102193. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luebker M. Inequality, income shares and poverty: the practical meaning of Gini coefficients. International Labour Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Getis A, Ord JK. The Analysis of Spatial Association by Use of Distance Statistics. In: Anselin L, Rey SJ, editors. Perspectives on Spatial Data Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010. p. 127–45. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dove-Medows E, Deriemacker A, Dailey R, Nolan TS, Walker DS, Misra DP, et al. Pregnant African American Women's Perceptions of Neighborhood, Racial Discrimination, and Psychological Distress as Influences on Birth Outcomes. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2020;45(1):49–56. doi: 10.1097/nmc.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bower KM, Geller RJ, Perrin NA, Alhusen J. Experiences of Racism and Preterm Birth: Findings from a Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 2004 through 2012. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(6):495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barber KFS, Robinson MD. Examining the Influence of Racial Discrimination on Adverse Birth Outcomes: An Analysis of the Virginia Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2016-2018. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(4):691–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daniels KP, Valdez Z, Chae DH, Allen AM. Direct and Vicarious Racial Discrimination at Three Life Stages and Preterm Labor: Results from the African American Women's Heart & Health Study. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(11):1387–95. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(1):14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dole N, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM, Hertz-Picciotto I, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and White women in central North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1358–65. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dominguez TP, Dunkel-Schetter C, Glynn LM, Hobel C, Sandman CA. Racial differences in birth outcomes: the role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27(2):194–203. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fryer KE, Vines AI, Stuebe AM. A Multisite Examination of Everyday Discrimination and the Prevalence of Spontaneous Preterm Birth in African American and Latina Women in the United States. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(13):1340–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giurgescu C, Zenk SN, Dancy BL, Park CG, Dieber W, Block R. Relationships among neighborhood environment, racial discrimination, psychological distress, and preterm birth in African American women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(6):E51–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Misra D, Strobino D, Trabert B. Effects of social and psychosocial factors on risk of preterm birth in black women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24(6):546–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orchard J, Price J. County-level racial prejudice and the black-white gap in infant health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2017;181:191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rankin KM, David RJ, Collins JW Jr. African American women's exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination in public settings and preterm birth: the effect of coping behaviors. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3):370–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Wise LA, Horton NJ, Corwin MJ. Perceptions of racial discrimination and the risk of preterm birth. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):646–52. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wheeler S, Maxson P, Truong T, Swamy G. Psychosocial Stress and Preterm Birth: The Impact of Parity and Race. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(10):1430–5. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of health psychology. 1997;2(3):335–51. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bond MA, Kalaja A, Cazeca D, Daniel S, Markkanen P, Punnett L, et al. Expanding our understanding of the psychosocial work environment: a compendium of measures of discrimination, harassment and work-family issues: Createspace Independent Pub; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 78.James SA. The John Henryism scale for active coping 1996. 415–25 p. [Google Scholar]

- 79.McNeilly MD, Anderson NB, Armstead CA, Clark R, Corbett M, Robinson EL, et al. The perceived racism scale: a multidimensional assessment of the experience of white racism among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 1996;6(1-2):154–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harrell SP, Merchant MA, Young SA. Psychometric properties of the racism and life experiences scales (RaLES). Unpublished manuscript. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosenberg L, Adams-Campbell L, Palmer JR. The Black Women's Health Study: a follow-up study for causes and preventions of illness. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association (1972). 1995;50(2):56–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Messina LC, Kramer MR. Multilevel analysis of small area violent crime and preterm birth in a racially diverse urban area. International Journal on Disability and Human Development. 2013;12(4):445–55. doi: 10.1515/ijdhd-2013-0207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dyer L, Hardeman R, Vilda D, Theall K, Wallace M. Mass incarceration and public health: the association between black jail incarceration and adverse birth outcomes among black women in Louisiana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):525. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2690-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dallaire DH, Woodards A, Kelsey C. Impact of parental incarceration on neonatal outcomes and newborn home environments: a case-control study. Public Health. 2018;165:82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hardeman RR, Chantarat T, Smith ML, Karbeah J, Van Riper DC, Mendez DD. Association of Residence in High-Police Contact Neighborhoods With Preterm Birth Among Black and White Individuals in Minneapolis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2130290. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chae DH, Clouston S, Martz CD, Hatzenbuehler ML, Cooper HLF, Turpin R, et al. Area racism and birth outcomes among Blacks in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nguyen TT, Meng HW, Sandeep S, McCullough M, Yu W, Lau Y, et al. Twitter-derived measures of sentiment towards minorities (2015-2016) and associations with low birth weight and preterm birth in the United States. Comput Human Behav. 2018;89:308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Komro KA, Markowitz S, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws on Birth Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):61–7. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sudhinaraset M, Woofter R, Young MT, Landrian A, Vilda D, Wallace SP. Analysis of State-Level Immigrant Policies and Preterm Births by Race/Ethnicity Among Women Born in the US and Women Born Outside the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e214482. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, Yamoah O, Roche A, Martinez R, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2021:114696. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ncube CN, Enquobahrie DA, Albert SM, Herrick AL, Burke JG. Association of neighborhood context with offspring risk of preterm birth and low birthweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Social science & medicine. 2016;153:156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jahn JL. Invited Commentary: Comparing Approaches to Measuring Structural Racism. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2022;191(4):548–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hardeman RR, Murphy KA, Karbeah JM, Kozhimannil KB. Naming Institutionalized Racism in the Public Health Literature: A Systematic Literature Review. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(3):240–9. doi: 10.1177/0033354918760574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.