Abstract

In the study, a previously isolated plant beneficial endophytic B. cereus CaB1 was selected for the detailed analysis by whole-genome sequencing. The WGS has generated a total of 1.9 GB high-quality data which was assembled into a 5,257,162 bp genome with G + C content of 35.2%. Interestingly, CaB1 genome was identified to have 40 genes with plant beneficial functions by bioinformatic analysis. At the same time, it also showed the presence of various virulence factors except the diarrhoeal toxin, cereulide. Upon comparative analysis of CaB1 with other B. cereus strains, it was found to have random distributions of virulence and plant growth promoting traits. The core genome phylogenetic analysis of the Bacillus cereus strains further showed the close relation of plant associated strains with isolates from spoiled food products. The observed genome flexibility of B. cereus thus indicates its ability to make use of diverse hosts, which can result either in beneficial or harmful effects.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03463-9.

Keywords: B. cereus, Endophyte, Pathogen, Plant growth promoting, Whole genome sequencing

Introduction

Endophytic microorganisms are considered to have the mechanistic basis to survive within the host plant without causing any adverse effect. They are tuned to have continuous biochemical interactions with the host and also with other microbial communities within the plant system (Rosenblueth and Martínez-Romero 2006). Their direct entry into the plant is considered to occur generally through the lateral roots especially at the zone of elongation and differentiation (Reinhold-Hurek and Hurek 2011). Movement of specific microbial candidates from the soil reserve to the site of entry in the plant is considered through the chemical signalling mediated by the exudates of the host plant root. Once being recruited to the rhizosphere, secondary selective measures are likely to function for the incorporation of the specific organism as a part of the endophytic microbiome (Bishnoi 2015). As the presence of plant beneficial features are being considered as a major criterion for this microbial recruitment, such features present in human pathogens might also favour their entry as an endophyte (Akhtyamova 2013; Santoyo et al. 2016). There are increasing reports on the isolation of Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from various fruits and vegetables with the likely origin from the plant material itself (Al-Kharousi et al. 2016). These organisms which are being hidden within the plants can also have their origin from the clinical source or sanitary waste from the livestock farms (Okeke et al. 1999; Akter et al. 2002). Some of their virulence factors are also likely to favour their entry into the plants. Because of the ubiquitous distribution, a large number of Bacillus species have already been identified to have plant-associated life with significant impact on plant growth, disease resistance and overall health (Bai et al. 2002). Endophytic B. cereus strains are also well known for the heavy deposition of plant beneficial features including nitrogen fixation, siderophore, IAA production and anti-phytopathogenic properties (Niu et al. 2011). Hence, its presence as part of the plant microbiome cannot be considered as an accidental association. However, the toxigenic and other virulence properties of B. cereus of plant origin has to be analysed in detail to predict its likely challenge to humans.

B. cereus strains can have wide range of effects both in plants and humans. There are increasing reports on the identification of rhizospheric or endophytic B. cereus strains with multiple plant beneficial and antiphytopathogenic mechanisms which are being recommended for field applications to manage the plant diseases (Niu et al. 2011). On the other hand, many strains are reported to be associated with foodborne illness and also with other conditions like central nervous system infections, endophthalmitis and cutaneous infections to a certain extent (Bottone 2010). Their major virulence factors include the production of phospholipase, enterotoxins and emetic toxin cereulide (Granum and Lund 2006). Hence, the Bacillus cereus genome provides an interesting platform to study the complexity with microbial adaptation to associate with diverse range of hosts.

The association with plants and humans and the resulting beneficial and harmful effects make the genome-wide analysis of B. cereus is interesting. In the study, Whole Genome Sequence (WGS)-based analysis has been used to provide insight into the lifestyle-based genomic adaptations among different strains of B. cereus. The dynamic nature and the flexibility of bacterial genome especially those with harmful impact on humans demand much predictive analysis to identify its trend towards more pathogenic form. The available WGS data of many B. cereus strains in the public database have been used for the comparative analysis with WGS data of B. cereus CaB1. This showed CaB1 to have heavy deposition of genes for plant growth promotion as well as virulence properties. The comparative genomic analysis using selected 39 genomes showed a common distribution pattern which indicates the likely adaptability of bacteria to both plant and human hosts.

Materials and methods

Source of organism

For the study, endophytic Bacillus cereus CaB1 from Capsicum annuum Lin. which has previously been demonstrated to have plant growth promoting properties was selected (Jasim et al. 2015).

Screening of CaB1 for virulence properties

Here, CaB1 was cultured for 24 h at room temperature on the selective medium Polymyxin pyruvate egg-yolk mannitol–bromothymol blue agar (peptone 1.0 g, mannitol 10.0 g, sodium chloride 2.0 g, magnesium sulphate 0.1 g, disodium hydrogen phosphate 2.5 g, potassium dihydrogen phosphate 0.25 g, bromothymol blue 0.12 g, sodium pyruvate 10.0 g, agar 15.0 g, distilled water 1000 mL, pH 7.2 ± 0.2 at 25 °C, polymyxin B 100,000 IU, sterile egg yolk emulsion 25 mL) used generally for Bacillus cereus (Mossel et al. 1966; Floriştean et al. 2007). Haemolytic property of CaB1 was further analysed by culturing it on 5% blood agar (nutrient agar, 0.15 M NaCl, 5% blood) (Bottone 2010).

Whole genome sequencing and data analysis

Here, CaB1 was inoculated into 5 mL of nutrient broth and incubated overnight at room temperature. The culture was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The pelleted cells were further washed and resuspended in 1× PBS buffer and OD was adjusted to 1 at 600 nm. From this, genomic DNA was isolated and quantified using Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA) and 100 ng of DNA was used for library preparation using QIAseq FX DNA Library kit. This involved enzymatic cleavage of DNA followed by the continuous step of end-repair to add A residues to the 3′ ends of DNA fragments. This was followed by ligation with-specific adapters to both ends of the DNA fragments and PCR amplification using HiFi PCR Master Mix. Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies) with High Sensitivity (HS) DNA chip was used to analyse the amplified library. The library was finally loaded into the Illumina platform for cluster generation and sequencing. The template of the fragments was sequenced in both forward and reverse directions by paired-end sequencing (Chaudhry and Patil 2016).

Sequence analysis

De novo assembly of high-quality paired-end reads of CaB1 was accomplished using Velvet-v1.2.10. The scaffolds were further gap-filled using PE reads information using GapCloser v-1.12. RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) Server was utilized to predict the tRNA and rRNA encoding genes (Aziz et al. 2008). BLASTx analysis (e-value threshold of e−05) was done for the identification of virulence genes from Virulence Factor Database.

Pangenomic and phylogenetic analysis

The average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis of CaB1 was done using JSpecies WS (http://jspecies.ribohost.com/jspeciesws/) by comparing with the genome data of 30 different Bacillus spp. genomes from NCBI database and visualised the Heat map by Gene-E. Circular representation was developed by CIRCOS (supplementary file 3).

To identify the core and variable gene-pool among CaB1, B. cereus FORC_005, B. cereus ATCC 14579 and B. cereus NC7401, pan-genomic analysis was carried out using Pan-Genome Analysis Pipeline (PGAP). Here, multiparanoid-based algorithm was used to search for orthologs at a minimum score value of 50 and at an E-value of less than 1 × 10−8 respectively as cut off (Zhao et al. 2012). Further, different Bacillus cereus genomes including B. cereus CaB1 were collected for comparative analysis of selected genes related to plant adaptive features and virulence. This was used to analyse the distribution of the adaptation characteristics among the B. cereus taxa.

SNP-based core genome phylogeny was constructed using B. cereus genomes isolated from various sources, such as clinical, spoiled food, environment and plants. For constructing the SNP-based core genome phylogeny, 35 complete and whole genome sequences of B. cereus were collected from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The genomes were aligned using muscle program, and a core-genome phylogenetic tree was generated by Parsnp (https://github.com/marbl/parsnp. The tree was visualised by using MEGA 10 (Treangen et al. 2014).

Comparative genomic analysis to identify the lifestyle adaptation in Bacillus cereus

The query sequences corresponding to 40 plant growth promoting and 20 virulence genes downloaded from the NCBI database were used to compare its presence and percentage of similarity across 40 selected B. cereus genomes.

Protein homology was determined by performing a BLASTp search against the selected plant growth promoting and virulence protein sequence of the 40 Bacillus cereus strains. Alignment with an e value cutoff of ≤ 0.0001, percentage identity cutoff of ≥ 60% and percentage query coverage cutoff of ≥ 60%, respectively, were considered for homologous proteins. The results were further presented on Coulson plot which depicts the presence and absence of the query proteins.

Results and discussion

16S rRNA sequencing and primary screening for virulence factors in CaB1

Repeated amplification of 16S rDNA from CaB1 and its sequence analysis has confirmed the selected isolate as a strain of B. cereus. When CaB1 was cultured on Polymyxin pyruvate egg-yolk mannitol–bromothymol blue agar, the colonies showed blue colour as expected for the typical B. cereus (Floriştean et al. 2007). CaB1 was also found to be positive for phospholipase as shown by the formation of white precipitation zone around the colonies due to the lysis of lecithin in the medium. At the same time, CaB1 also has exhibited β-haemolytic properties when cultured on 5% blood agar (Bottone 2010).

General features of CaB1 genome

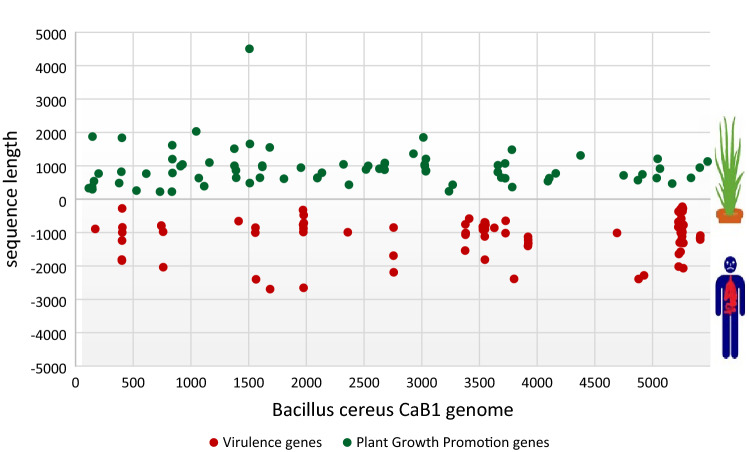

The Whole Genome Sequencing of CaB1 has generated a 1.9 Gb high-quality sequence data. This was assembled into 53 scaffolds which contained total sequence length of 5,257,162 bp with N50 of 416,772 bp and an average G + C content of 35.2%. The genome sequence of B. cereus CaB1 was submitted to Genbank under the accession number GCF020503975.1. Comparative genomic analysis of CaB1 with FORC_005, NC7401, and ATCC14579 showed comparable features (Table 1). WGS of CaB1 was predicted to have 5497 Open Reading Frames (ORF). All the ORFs, when searched for similarity against the COG database, showed a total of 3164 Hits. The top-hit species distribution of CaB1 revealed the majority to be members of Bacillus cereus. Among the 3164 genes identified, 1124 were putative virulence genes. In addition, 419 genes were associated with general functions, 349 in amino acid transport and metabolism, 106 were tRNA genes and 13 were rRNA genes. Out of the 1124 virulence hits, 88 genes were found to have above 90% similarity with existing database (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

General features of Bacillus cereus CaB1 genome in comparison with three reference strains

| B. cereus Strains | CaB 1 | FORC_005 | ATCC14579 | NC7401 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession number | GCF020503975.1 | CP009686.1 | NC_004722 | AP007209 |

| Genome size (bp) | 5,257,162 | 5,349,617 | 5,426,909 | 5,221,581 |

| G + C content (%) | 35.2 | 35.29 | 35.3 | 35.6 |

| No. of CDS | 5497 | 5318 | 5366 | 5415 |

| No. of rRNAs | 13 | 42 | 26 | 14 |

| No. of tRNAs | 106 | 106 | 108 | 104 |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of plant growth promoting genes and virulence genes in B. cereus CaB1 genome based on the RAST annotation. Red dots with negative represent the virulence genes and green dots with positive value represent the plant growth promoting genes

Phylogenomic and pangenomic analysis

The ANI analysis has showed B. cereus CaB1 to have close similarity with the rhizosphere isolate B. cereus C1L (98.57%) (Fig. 2). The pangenomic analysis showed conservation of 4076 core gene pool among CaB1, FORC_005, ATCC14579, and NC7401. At the same time, 457 genes were identified to be unique to CaB1, 243 for FORC_005, 1050 for NC7401 and 438 for ATCC 14579, respectively. In the phylogenetic analysis, CaB1 was found to have remarkable clustering with strains from plants and spoiled food (Fig. 3). Since many pathogenic strains with plant growth promoting traits have been reported to be kept hidden within fruits and vegetable sprouts, the observation from the phylogenetic analysis is very significant (Al-Kharousi et al. 2016). All the selected plant associated strains have completely clustered with the strains from spoiled food. From these, the food poisoning cases of humans caused by contaminated vegetables may be considered to be related to these hidden microbes at least in some cases (Naranjo et al. 2011). The phylogenetic analysis also showed the distribution of plant beneficial strains among pathogenic strains across the B. cereus taxa irrespective of its human or plant origin which confirms its versatility to survive in multiple hosts (Fig. 3). This also alarms the food safety of fresh fruits and vegetables not only by B. cereus but also by other human pathogens which have plant association. Hence, more genome-wide studies on the genetic basis of interaction of human pathogens with common edible plants are required to predict the general trend involved. In the study, plant growth promoting genes against virulence genes were found to be distributed throughout the genome of CaB1.

Fig. 2.

Heatmap showing the ANI values of Bacillus spp. Here, B. cereus CaB1 shows close similarity with B. cereus C1L (98.57%) isolated from rhizosphere

Fig. 3.

Core genome phylogenetic tree constructed using parsnp showing clustering of B. cereus strains isolated from different sources

Genomic evidence for pathogenicity

The genome mining of CaB1 has resulted in the identification of major virulence factors (supplementary file 3). Among these, phospholipase C (plcA), phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase precursor (piplc), non-hemolytic enterotoxin genes (nheC, nheB and nheA), anthrolysin O (BC5101) and hemolysin BL (hbl) showed 100 percentage identity with the type strain Bacillus cereus ATCC14579. While the iron compound ABC transporter permease protein-petrobactin (fatC) showed 99.71% similarity to Bacillus anthracis str. Ames Ancestor. The virulence gene annotation also showed the presence of genes for cell phospholipase C which helps the bacterium to colonise within the host cell by hydrolysing the host cell membrane. Hemolytic proteins, which cause the RBC lysis and the enterotoxins majorly produced during the spore germination could also be predicted for B. cereus CaB1 from the WGS data. However, there was no evidence for the presence of emetic toxin cereulide and hence CaB1 can expect to have pathogenic potential to cause diarrhoeal disease (Takeno et al. 2012).

Endophyte lifestyle supporting properties of B. cereus CaB1

The genome annotation of CaB1 revealed the presence of several genes which are presumed to be evolved as an adaptation to the endophytic lifestyle. The recruitment of microbial candidates towards the host plant and the microbial existence inside the host are the basic processes involved in the endophytic colonisation. Bacteria have been reported to use quorum sensing mechanisms for diverse purposes and the same are considered to function during their entry into the plants as endophytes. Quorum sensing compounds like N-acyl homoserine lactone have also been demonstrated to have a direct impact on plant growth positively (Schikora et al. 2016). So the quorum sensing genes including luxS and luxR, which are abundantly distributed in the CaB1 genome, could be an indication of its role in plant colonisation process also. Other multimechanistic processes related to the microbial entry into the plant involves attachment, invasion and protection from plant defence mechanisms. The genome analysis of CaB1 conducted in the study has identified the presence of different surface proteins with putative role in bacterial attachment to the plant tissues and subsequent colonisation. The putative cell adhesion protein LPXTG, cell wall anchoring protein and TqXA domain-containing multispecies adhesins observed are expected to favour the entry of CaB1 into plants (Chaudhry and Patil 2016).

Survival of endophytes inside the plant host against the oxidative stress mechanisms are important. Hence, the presence of multiple genes coding for superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (bsaA) and osmotically inducible protein C (OsmC) could be a reflection of its genomic adaptation for the successful endophytic association (Briggs et al. 2013). The presence of methionine sulfoxide reductase (msrA) gene in CaB1 can also be consider to help the organism to manage the oxidative damage caused by sulfonation of methionine. Halo acid dehydrogenase is another enzyme which can have protective role on CaB1 against the stress effect of halogen-containing plant defence compounds. The trehalose transporter and trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase which are involved in the transport of trehalose across the cell membrane can also be favourable for the endophytic survival of B. cereus CaB1. CaB1 was found to produce chitinase, which is a hydrolytic enzyme cleaving the chitin present in the cell wall material of pathogenic fungi. The presence of genes related to nitrogen fixation (Nifu and Nif3) indicates the role of CaB1 to increase the nitrogen availability to plants. Genes coding for acetone synthesis and metabolism were also detected in the genome of CaB1, which indicated the key regulatory effect of CaB1 on phytohormone functioning. The gene coding for indole pyruvate decarboxylase and IAA acetyltransferase of CaB1 is predictive of its phytohormone production, which generally known to influence stem elongation, apical meristem, and root sprouting. Iron ABC transporter and periplasmic iron-binding proteins of CaB1 are indicative of their role in the uptake and mobilisation of iron to make it available to plants. Genes coding for nitric oxide synthase oxygenase domain which protect the plant from oxidative stress, formamidase helping the plant to acclimatised to the nutrient deficiency and the glycine betaine system supporting the plant to withstand the environmental stress could also be identified from genome data of CaB1. Phosphate solubilising property of B. cereus CaB1 could also be demonstrated due to the presence of genes glucose dehydrogenase, phosphate ABC transporter pstA-C, alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase. Hydrogen sulphide production by CaB1 could also be related to the plant growth promotion. Genes which code for adenylyl sulphate kinase and sulphate adenylyl transferase were also found to be present in CaB1 genome. The phzF gene and the multi-species phenazine biosynthesis genes responsible for the production of antifungal compounds observed for the CaB1 are indicative of its ability to help the host to defend the invasion by fungal phytopathogens. The CaB1 genome also contained the genetic basis for spermidine synthase and related transport genes which indicate its likely impact on plant growth and stress (Nassar et al. 2003; Gill and Tuteja 2010). The presence of genes for lipopolysaccharides, acetoin synthesis and 2,3-butanediol and siderophores further showed the ability of CaB1 to induce defence response in plants (Santoyo et al. 2016).

Comparative genomics

Comparative genomic analysis of the virulence and plant growth promotion-related genes of CaB1 against the B. cereus strains isolated from different sources revealed no significant pattern specific to the plant beneficial or virulence traits. 50% (10) of the virulence genes tested were found to present in more than 90% of the tested isolates. However, the emetic toxin genes CesA, CesB and CesD were present in 5% of the tested genomes. Interestingly, all the plant growth promoting strains shows more than 86.48% of the tested virulence genes (Fig. 4). This confirmed the ability of plant beneficial Bacillus cereus strains to have the chance to carry active virulence factors.

Fig. 4.

Coulson Plot Showing comparative evaluation of Presence and absence pattern of Virulence genes (Supplementary file 1) in selected 37 genomes of Bacillus cereus

The analysis on plant growth promotion related genes showed CaB1 to have a wide distribution of genes for bacterial entry, survival and host plant colonisation. The major genes such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase required for the survival of endophytes in the host plant were found to present in all the strains irrespective of its plant beneficial or pathogenic role. This also ensures the ability of Bacillus cereus to survive inside the plant system. However, the IAA producing genes indole pyruvate decarboxylase and IAA acetyl transferase could be observed among 89.18% and 86.48% strains respectively. In conclusion, the plant growth promotion related genes were found to be distributed in B. cereus strains in the same pattern irrespective its of the source of isolation (Fig. 5). The study indicates the need for a deeper insight into the genomic analysis of plant growth beneficial microorganisms.

Fig. 5.

Coulson Plot Showing comparative evaluation of Presence and absence pattern of endophytic colonisation, survival and plant growth promoting genes (supplementary file 2) in selected 37 genomes of Bacillus cereus

Conclusion

The study revealed the genomic adaptability of the Bacillus cereus for a plant niche and its genetic basis to overcome a negative selection of the host plant. Interestingly, a detailed comparative analysis of plant growth-promoting and virulence properties of B. cereus of diverse origin showed a random distribution of these properties among different isolates. The whole-genome sequence-based analysis of selected CaB1 revealed its likely potential to switch to a human pathogen from an endophytic lifestyle as per the host change. The plant beneficial behaviour of this soil-dwelling microorganism enforces the plant–microbe interaction and hence favour the survival of its pathogenic traits. Availability of less WGS data of plant growth-promoting strains in B. cereus taxa is the major limitation in calculating the versatility of this organisms. From this study, B. cereus can be concluded to the have strong adaptation capabilities for hiding in a plant without losing its virulence properties. This leads to caution about the enteric pathogens hiding in fresh produce and its possible contamination potential.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledging Miss. Jilna Babu and Miss. Celene Francis research assistants at Center for Bioinformatics, School of Biosciences, Mahatma Gandhi University.

Author contributions

SS: conceptualization, data analysis, writing; MP: data analysis, SBM: writing, CGI: writing, CSB: data analysis, AK: Software and whole genome analysis; RB: software and whole genome analysis; SNS: conceptualization, review and editing; EKR: conceptualization, supervision and editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

This is to declare that the authors have no conflict of interest on this research work.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Akhtyamova N. Human pathogens—the plant and useful endophytes. J Med Microbiol Diagn. 2013 doi: 10.4172/2161-0703.1000e121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akter N, Hussain Z, Trankler J, Parkpian P. Hospital waste management and it’s probable health effect: a lesson learned from Bangladesh. Indian J Environ Health. 2002;44:124–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kharousi ZS, Guizani N, Al-Sadi AM, et al. Hiding in fresh fruits and vegetables: opportunistic pathogens may cross geographical barriers. Int J Microbiol. 2016;2016:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2016/4292417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best A, et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, D’Aoust F, Smith DL, Driscoll BT. Isolation of plant-growth-promoting Bacillus strains from soybean root nodules. Can J Microbiol. 2002;48:230–238. doi: 10.1139/w02-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishnoi U (2015) PGPR interaction: an ecofriendly approach promoting the sustainable agriculture system. In: Advances in botanical research, vol 75. Academic Press, pp 81–113

- Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:382–398. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00073-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs L, Crush J, Ouyang L, Sprosen J. Neotyphodium endophyte strain and superoxide dismutase activity in perennial ryegrass plants under water deficit. Acta Physiol Plant. 2013;35:1513–1520. doi: 10.1007/s11738-012-1192-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry V, Patil PB. Genomic investigation reveals evolution and lifestyle adaptation of endophytic Staphylococcus epidermidis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19263. doi: 10.1038/srep19263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floriştean V, Cretu C, Carp-Cărare M. Bacteriological characteristics of Bacillus cereus isolates from poultry. Bull Univ Agric Sci Vet Med Cluj Napoca Vet Med. 2007;64:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. Polyamines and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:26–33. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.1.10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granum PE, Lund T. Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;157:223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollants J, Leroux O, Leliaert F, et al. Who is in there? Exploration of endophytic bacteria within the siphonous green seaweed bryopsis (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasim B, Geethu PR, Mathew J, Radhakrishnan EK. Effect of endophytic Bacillus sp. from selected medicinal plants on growth promotion and diosgenin production in Trigonella foenum-graecum. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015;122:565–572. doi: 10.1007/s11240-015-0788-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mossel DAA, Koopman MJ, Jongerius E. The enumeration of Bacillus cereus in foods. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1966;32:453. doi: 10.1007/BF02097503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo M, Denayer S, Botteldoorn N, et al. Sudden death of a young adult associated with Bacillus cereus food poisoning. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4379–4381. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05129-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar AH, El-Tarabily KA, Sivasithamparam K. Growth promotion of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) by a polyamine-producing isolate of Streptomyces griseoluteus. Plant Growth Regul. 2003;40:97–106. doi: 10.1023/A:1024233303526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu D-D, Liu H-X, Jiang C-H, et al. The plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus cereus AR156 induces systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana by simultaneously activating salicylate- and jasmonate/ethylene-dependent signaling pathways. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24:533–542. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-10-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Edelman R. Socioeconomic and behavioral factors leading to acquired bacterial resistance to antibiotics in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:18–27. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold-Hurek B, Hurek T. Living inside plants: bacterial endophytes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblueth M, Martínez-Romero E. Bacterial endophytes and their interactions with hosts. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006;19:827–837. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo G, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, del Carmen O-M, Glick BR. Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes. Microbiol Res. 2016;183:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikora A, Schenk ST, Hartmann A. Beneficial effects of bacteria-plant communication based on quorum sensing molecules of the N-acyl homoserine lactone group. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;90:605–612. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeno A, Okamoto A, Tori K, et al. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus cereus NC7401, which produces high levels of the emetic toxin cereulide. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4767–4768. doi: 10.1128/JB.01015-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, et al. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15(11):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Wu J, Yang J, et al. PGAP: pan-genomes analysis pipeline. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:416–418. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.