Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of progressively disabling dementia. The chitinases CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 have long been known as biomarkers for microglial and astrocytic activation in neurodegeneration. Here, we collected microarray datasets from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) brain samples of non-demented controls (NDC) (n = 460), and of deceased patients with AD (n = 697). The AD patients were stratified according to sex. Comparing the high CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression group (75th percentile), and low CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression group (25th percentile), we obtained eight signatures according to the sex of patients and performed a genomic deconvolution analysis using neuroimmune signatures (NIS) belonging to twelve cell populations. Expression analysis revealed significantly higher CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression in AD compared with NDC, and positive correlations of these genes with GFAP and TMEM119. Furthermore, deconvolution analysis revealed that CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 high expression was associated with inflammatory signatures in both sexes. Neuronal activation profiles were significantly activated in AD patients with low CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels. Furthermore, gene ontology analysis of common genes regulated by the two chitinases unveiled immune response as a main biological process. Finally, microglia NIS significantly correlated with CHI3L2 expression levels and were more than 98% similar to microglia NIS determined by CHI3L1. According to our results, high levels of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in the brains of AD patients are associated with inflammatory transcriptomic signatures. The high correlation between CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 suggests strong co-regulation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-022-00664-7.

Keywords: CHI3L1, CHI3L2, Alzheimer’s disease, Chitinase, Chitotriosidase, Microglia

Introduction

Alzheimer-Perusini’s disease (AD), the most common form of progressively disabling degenerative dementia in the elderly, includes early-onset familial forms [1] and exhibits severe cognitive deficits including memory loss and language impairment, finally leading to increased dependence in everyday life [2]. Sample evidence ascertains that activation of glial cells, microglia, and astrocytes particularly, might support a low-grade neuroinflammation and, thus, contributing to, or preventing from neurodegenerative processes [3]. Aβ plaques activate microglia and astrocytes, in such a way promoting immune responses [4–6], considered fundamental for the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and, therefore, leading to neuronal dysfunction [7].

AD incidence is higher in women than in men. Two-thirds of people diagnosed with AD have dementia, independently of sex: even if women and men have the same incidence of AD dementia, the mechanisms, pathways, and risk factors differ. Several studies examining risk factors for AD “adjust” for sex in their analysis, notwithstanding not determining whether an actual sex difference exists. Physiologically, female microglia and estrogen have protective effects. However, in AD, female microglia seem to lose their protective capability and instead accelerate the course of AD [8].

Neuroinflammation has been implicated in almost all neurodegenerative diseases, along with AD [9]. Despite microglia and astrocytes belong to neuroimmune system, being the first line of defense against invading pathogens or other types of non-self brain debris [10], their interaction with the peripheral immune system is not yet clear [11]. Microglia possesses both pro- and anti-inflammatory functions. Astrocytes are the most abundant glial subtype in the brain, and similar to microglia cell, can modulate neuroinflammation [12]. Structurally, microglial cells are close to blood vessels and interact with endothelium cells, actively participating in the maintenance and permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [13]. Recently, deep astrogliosis was detected in brains of AD patients [14].

Among the proteins committed in AD-associated neuroinflammation, our attention focused on chitinases family, an ancient gene family including proteins, expressed in innate immune cells [15, 16]. Chitinase 3-like-1 (CHI3L1, also called YKL40 or HC-gp39), mainly expressed in astrocytes [17] is upregulated in a plethora of neurodegenerative disorders [18–20] and specifically associated with the pathogenesis of AD [21, 22]. CHI3L1 expression levels augmented in central nervous tissue of AD patients, leading us to hypothesize that CHI3L1 might have immunological activity in this neuroinflammatory scenario [18, 23–25]. When measured in AD cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), CHI3L1 is a likely candidate biomarker of glial activation, also being linked to neurodegeneration markers tau and neurofilament light (NFL) [26–32]. Chitinase-3-like protein 2 (CHI3L2 or YKL39) is a glycoprotein secreted by different cell types such as polarized macrophages [33], dendritic cells [34], osteoclasts [35], and numerous cells with high proliferative activity [36]. Very little is known about the role of CHI3L2 [37], despite being considered the closest homolog of CHI3L1 [35, 38]. High CHI3L2 expression levels were observed in brains of neurological disease such as neuro-HIV-1 [39], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [40], and AD [23, 24]. Although initially associated with macrophage lineage, evidence suggests that, during neuroinflammatory processes, CHI3L2 expression increases in astrocytes [41], microglial cells [42], and infiltrating macrophages [37, 43].

Here, we analyzed microarray datasets of brain samples from non-demented control subjects (NDC) died from causes not attributable to neurodegenerative pathologies and from deceased patients suffering from AD. The significant transcriptomes, weighted according to CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels and sex, were overlapped with genes enriching CNS cells and immune cells, aiming to discriminate the cellular architecture of AD patients’ brains according to their sex.

Materials and methods

Dataset selection

The NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (Clough and Barrett, 2016) was used to select transcriptomes datasets of interest. Mesh terms “Alzheimer”, “brain”, and “human”, were used to identify the potential datasets to select. We sorted the datasets by the number of samples (High to Low), age, sex, and by clinical data. Two datasets were selected, performed with the same platform (GPL4372), and subsequently merged for our analysis using z-score calculation (Statistical Analysis section) (Table 1). We chose to merge only the datasets with the same platform in order to reduce the errors oscillation introduced with different platforms. The datasets were selected following the criteria exposed in the section “Clinical and pathological criteria”.

Table 1.

Datasets selected

| N° | Datasets | Organism | Samples | Platform | NDC | AD | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GSE44772 | Human | 690 | GPL4372 |

303 (246 ♂ and 57 ♀) |

387 (186 ♂ and 201 ♀) |

23622250 |

| 2 | GSE33000 | Human | 467 | GPL4372 |

157 (123 ♂ and 34 ♀) |

310 (135 ♂ and 175 ♀) |

25080494 |

| 3 | Merging | Human | 1157 | GPL4372 |

460 (369 ♂ and 91 ♀) |

697 (321 ♂ and 376 ♀) |

// |

NDC, non-demented control subjects; AD, Alzheimer’s disease

Sample stratification

To test our hypotheses, we collected microarray datasets to gather brain samples of NDC who died from causes not attributable to neurodegenerative diseases (n=460; 369 males, mean age (ma)=61.89, and 91 females, ma=65.45), and of deceased patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (n=697; 321 males with ma=78.28, and 376 females with ma=82.11). AD patients were selected according to sex and stratified using CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels as a cut-off. We obtained four groups subsequently used for our statistical comparisons. AD patients from the 75th percentile (upper quartile) were considered in this study as High CHI3L1 expression group (HC1EG) and CHI3L2 expression group (HC2EG), which included 80 males patients (z-score= 0.87-> 3.20) and 94 females patients (z-score= 1.14-> 3.38) for CHI3L1, and 82 males patients (z-score= 0.53-> 4.00) and 95 females patients (z-score= 0.77-> 3.87) for CHI3L2. The Low CHI3L1 expression group (LC1EG) corresponded to the patients in the 25th percentile (lower quartile) and included 80 male patients (z-score= -0.43-> -1.67) and 94 female patients (z-score= -0.15-> -1.43). Furthermore, as regards the patients that express low levels of CHI3L2, we indicated as Low CHI3L2 expression group (LC2EG) the 25th percentile (lower quartile) and included 82 male patients (z-score= -0.44-> -1.84) and 97 female patients (z-score= -0.26-> -2.23).

Samples belonging to the 75th and 25th percentiles were interpreted as having a transcriptome that is concordant (i.e., significantly correlated) to the specified signature selected, and the values of the target gene expressed in the stratified samples as a function of the percentile values concordant with the expression of the gene chosen as specific signature (CHI3L1 and CHI3L2).

By stratifying the AD patients according to sex and then to CHI3L1 expression levels, as a subset signature, we found that, in males, 1365 unique genes (including CHI3L1) were significant positive correlated (GSPC) (r-range from 0.40 to 0.83) and 1455 unique genes significant negative correlated (GSNC) (r-range from -0.40 to -0.66) to CHI3L1 expression levels (Supplementary Table 1) (Table 2). As regards the female’s group, we found that there were 2323 unique GSPC (r-range from 0.40 to 0.84) and 816 unique GSNC (r-range from -0.40 to -0.61) to CHI3L1 expression levels (Supplementary Table 1) (Table 2). As regards CHI3L2, we found that, in males, 2113 unique genes (including CHI3L2) were significant positive correlated (GSPC) (r-range from 0.40 to 0.81) and 1502 unique genes significant negative correlated (GSNC) (r-range from -0.40 to -0.66) to CHI3L2 expression levels (Supplementary Table 1) (Table 2). As regard the female’s group, we found that there were 3313 unique GSPC (r-range from 0.40 to 0.86) and 3049 unique GSNC (r-range from -0.40 to -0.67) to CHI3L2 expression levels (Supplementary Table 1) (Table 2).

Table 2.

AD patients’ stratification

| Samples | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| High CHI3L1 expression group (HCEG1) (75th percentile) | 80 | 94 |

| High CHI3L2 expression group (HCEG2) (75th percentile) | 82 | 95 |

| Low CHI3L1 expression group (LCEG1) (25th percentile) | 80 | 94 |

| Low CHI3L2 expression group (LCEG2) (25th percentile) | 82 | 97 |

| z-score value cut-off (75th percentile) for CHI3L1 | 0.87-> 3.20 | 1.14-> 3.38 |

| z-score value cut-off (75th percentile) for CHI3L2 | 0.53-> 4.00 | 0.77-> 3.87 |

| z-score value cut-off (25th percentile) for CHI3L1 | -0.43-> -1.67 | -0.15-> -1.43 |

| z-score value cut-off (25th percentile) forCHI3L2 | -0.44-> -1.84 | -0.26-> -2.23 |

| Middle age (75th percentile) for CHI3L1 | 78.32 | 83.48 |

| Middle age (75th percentile) for CHI3L2 | 78.10 | 84 |

| Middle age (25th percentile) for CHI3L1 | 75.95 | 81.57 |

| Middle age (25th percentile) for CHI3L2 | 74.98 | 78.82 |

| Unique genes significant positive correlated (GSPC1) to CHI3L1 |

2314 (r=0.30->0.83) |

2338 (r=0.30->0.84) |

| Unique genes significant positive correlated (GSPC2) to CHI3L2 |

1847 (r=0.30->0.81) |

2909 (r=0.30->0.86) |

| Unique genes significant negative correlated (GSNC1) to CHI3L1 |

2020 (r=-0.30->-0.61) |

1380 (r=-0.30->-0.61) |

| Unique genes significant negative correlated (GSNC2) to CHI3L2 |

1406 (r=-0.30->-0.66) |

2806 (r=-0.30->-0.67) |

Clinical and pathological criteria

Most of the samples analyzed were obtained from public tissue banks (Table 1). Sample pH, and RNA integrity number (RIN) were elements of pre-selection by the authors of the reference microarray datasets, and subsequently, object of our further exclusion analysis. The authors of original studies reported that all patients gave informed consent, and this study was approved by the medical ethics committees of all sites. All specimens were derived from brain biopsies and were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after surgery for storage at −80 °C.

Data processing and experimental design

To process and identify Significantly Different Expressed Genes (SDEG) within the datasets, we used the MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV) software (The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR), J. Craig Venter Institute, La Jolla, USA). In cases where multiple genes probes have insisted on the same GeneID NCBI, we used those with the highest variance.

With the aim of identifying genes commonly modulated between the GSE datasets present in Table 1 and cell type-specific genes for brain cells, we performed a Venn diagram analysis, using the web-based utility Venn Diagram Generator (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) [44, 45]. For GSE44772 and GSE33000, we also performed a statistical analysis with GEO2R, applying a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate test [46–48].

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using the web utility GeneMANIA (http://genemania.org/) [49], STRING (https://string-db.org/) [50], and the GATHER (Gene Annotation Tool to Help Explain Relationships) (http://changlab.uth.tmc.edu/gather/) [51]. The STRING was also used for building the weighted gene networks commonly modulated, rendered by CorelDRAW2020 (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Additionally, we used public human brain single-cell RNA-sequencing data (RNA-seq, accession no. GSE67835) in order to carry out a panel of cell tissue-specific genes for five main brain cells, i.e., astrocytes (n=191), endothelial cells (endotheliocytes) (n=76), neurons (n=1032), microglia (n=118), and oligodendrocytes (n=111) [52]. From GSE46236, we sorted the SDEG of inflammatory pericytes (n=333) [53].

We deepened the analysis including the immune system cellular profiles, consisting of CD8 T cell (naïve and resting) (CTLs) (n=63), classical Natural Killer (NK) (n=125), T helper cell type 1 (Th1) (n=221), and 2 (Th2) (n=98), obtained from the GSE22886 and two population of macrophages classical and alternative activated, macrophages M1 (n=823) and macrophages M2 (n=160) from GSE5099. As regards the immune-cells GSE22886 dataset, was composed by twelve different isolated types of human leukocytes from peripheral blood and bone marrow. In order to obtain the genes characterizing these cells, we excluded all significant genes in common among all types of human leukocytes and, successively, we selected genes mutually exclusive among those were significantly up-regulated [45, 54].

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used [55]. Statistical significance of the overlap (intersection) between two lists of genes was calculated with Exact hypergeometric probability. The representation factor shows whether genes from one list (list A) are enriched in another list (list B), assuming that genes behave independently. The representation factor is defined as (number of genes in common between both lists) (number of genes in the genome)/(number of genes in list A)(number of genes in list B). A RF > 1 indicates more overlap than expected between the two independent groups, a RF < 1 indicates less overlap than expected, and a RF of 1 indicates that the two groups are identical by the number of genes expected to be independent in the groups.

The probability of finding x overlapping genes can be calculated using the hypergeometric probability formula:

where x = # of genes in common between two groups; n = # of genes in group 1; D = # of genes in group 2; N = total genes, in this case 20203 genes (RefSeq, a database run by the US National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)); C (a,b) is the number of combinations of a thing taken ‘b’ at ‘a’ time [56, 57].

Significant differences between groups were assessed using the Ordinary one-way ANOVA test, and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test correction was executed to compare data among all groups. Correlations were determined using Pearson correlation. All tests were two-sided and significance was determined at adjusted p value 0.05. All datasets selected were transformed for the analysis in Z-score intensity signal. Z score was constructed by taking the ratio of weighted mean difference and combined standard deviation according to Box and Tiao (1992) [58]. The application of a classical method of data normalization, z-score transformation, provides a way of standardizing data across a wide range of experiments and allows the comparison of microarray data independent of the original hybridization intensities. The z-score it is considered a reliable procedure for this type of analysis and can be considered a state-of-the-art methods, as demonstrated by the numerous bibliography [59–69].

The efficiency of each biomarker was assessed by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses. Nonparametric ROC curves analyzed AD vs. NDC. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) indicate diagnostic efficiency. The accuracy of the test with the percent error is reported [70].

Results

CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression in AD compared with non-AD brain tissue

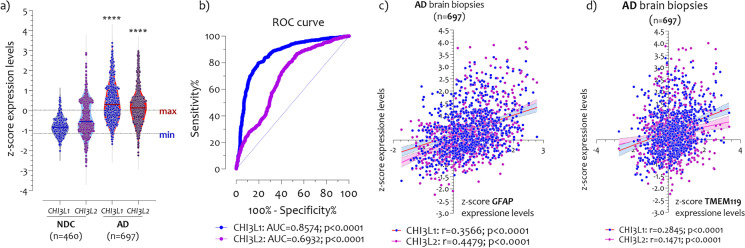

Aiming to analyze CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in AD brains, we merged microarray datasets with the same platform after transformation into z-scores. We obtained data from 460 NDC brains (369 males and 91 females), and 687 AD brains (321 males and 376 females) (Table 1). Expression analysis revealed a significant increase in CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 levels in AD compared with non-AD brains (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1a). To evaluate the potential diagnostic ability of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 to discriminate between AD patients and NDC subjects, we applied a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. CHI3L1 expressed an excellent diagnostic ability to discriminate AD from NDC brains (AUC = 0.8570, p < 0.0001), and CHI3L2 showed satisfactory performance (p<0.0001, AUC=0.6932) (Fig. 1b). Since chitinases are closely linked to the aging process, we correlated CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression with age in AD and non-AD subjects. The Pearson correlation analysis performed highlighted high significant correlation between CHI3L1 (r = 0.4743, p <0.0001), and CHI3L2 (r = 0.3523, p <0.0001), and age (Supplementary Fig. 1). To verify the close relationship between chitinases and astroglia, and microglia cells, we performed correlation analysis with the GFAP as astroglia marker [71], and with TMEM119 as microglia marker [72, 73]. The analysis showed significant positive correlation between CHI3L1 (r = 0.3566, p <0.0001), CHI3L2 (r = 0.4479, p <0.0001), and GFAP expression levels in AD brain biopsies (Fig. 1c). Yet, we highlighted significant positive correlation between CHI3L1 (r = 0.2845, p <0.0001), and CHI3L2 (r = 0.1471, p <0.0001), and TMEM119 expression levels in AD brain biopsies (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in AD brains. Significant increase of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in AD brains (n=697) compared with control (non-demented control (NDC)) (n=460) (a); High diagnostic ability of CHI3L1 (p<0.0001, AUC=0.8574) to discriminate control subjects from AD patients, and satisfactory ability of CHI3L2 (p<0.0001, AUC=0.6932) (b); Pearson correlation analysis performed between CHI3L1 (r=0.3566, p<0.0001), and CHI3L2 (r=0.4479, p<0.0001), and astrocyte activation marker GFAP (c); Pearson correlation analysis performed between CHI3L1 (r=0.2845, p<0.0001), and CHI3L2 (r=0.1471, p<0.0001), and microglia marker TMEM119 (d). The dashed lines indicate the maximum and minimum mean values. Data are expressed as z-score intensity expression levels (means and SD) and presented as violin dot plots. The orange dots indicate the upper and lower quartile CHI3L1 expression levels. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant (****p<0.00001)

By stratifying the samples according to sex, we found significant variations in the expression levels of the two chitinases. Indeed, both the expression levels of CHI3L1 (p <0.001) and those of CHI3L2 (p <0.001) were significantly higher in AD females than in males compared with NDC subjects, and the AD females expressed significant higher levels of CHI3L1 compared to CHI3L2 (p<0.001) (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the brain expression levels of the two chitinases were positively correlated with each other in AD patients (r = 0.5248, p <0.0001) (Fig. 2b), and this correlation remained significant in both males (r = 0.4639, p <0.0001 ) (Fig. 2c) and in AD females (r = 0.5495, p <0.0001) (Fig. 2d), albeit with a slight slope of the curve in males compared to females (r = 0.4639 in males, r = 0.5495 in females ). All these findings are in accordance with data previously reported by our group [18, 23–25, 74–77].

Fig. 2.

CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression and correlation analysis in AD brain biopsies according to patient’s sex. Significantly higher expression of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in female compared with male AD (a). Pearson correlation analysis performed between CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in all samples (b) (r=0.5248, p<0.0001), in males (c) (r=0.4639, p<0.0001), and in females AD (d) (r=0.5495, p<0.0001). The dashed lines indicate the maximum and minimum mean values. Data are expressed as z-score intensity expression levels (means and SD) and presented as dot plots. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant (**p<0.001, ***p<0.0001)

AD males and females exhibit different brain neuro-immune cellular profile according to CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels

We conducted a genomic deconvolution analysis (GDA) using neuro-immune signatures (NIS) obtained from GEODatasets, KEGG, and AmiGo (Table 3). Cell signatures covered six neurological and six immune cells populations, as described in the “Materials and methods” section.

Table 3.

The twelve signatures – neuro-immune signature (NIS)

| n° | Cells and processes | Source | Unique genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Astrocyte | GSE67835 | 177 |

| 2 | Endothelial cells | GSE67835 | 55 |

| 3 | Microglia | GSE67835 | 93 |

| 4 | Neuron | GSE67835 | 974 |

| 5 | Oligodendrocytes | GSE67835 | 95 |

| 6 | Pericyte inflammatory | GSE46236 | 206 |

| 7 | CTLs | GSE22886 | 58 |

| 8 | M1 macrophages | GSE5099 | 674 |

| 9 | M2 macrophages | GSE5099 | 132 |

| 10 | Natural Killer (NK) | GSE22886 | 114 |

| 11 | Th1 | GSE22886 | 191 |

| 12 | Th2 | GSE22886 | 85 |

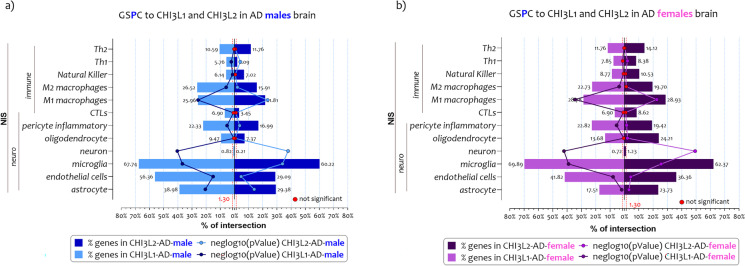

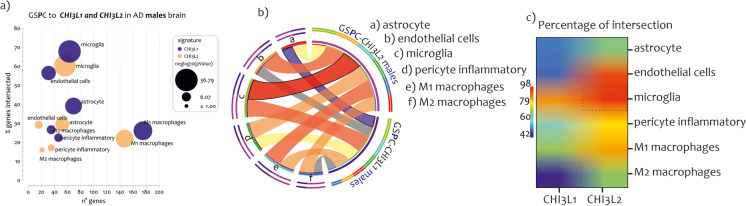

We intersected the lists of genes that characterize the NIS signatures to the genes lists significantly positively correlated respectively to CHI3L1 (ngene=2314) and CHI3L2 (ngene=1847) expression levels in AD males’ brains (GSPC-CHI3L1-males, and GSPC-CHI3L2-males) (Fig. 3a). In addition, we intersected the NIS signatures to the genes lists significantly positively correlated respectively to CHI3L1 (ngene=2338) and CHI3L2 (ngene=2909) expression levels in AD females’ brains (GSPC-CHI3L1-females, and GSPC-CHI3L2-females) (r>0.40, strong positive relationship) (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 3.

NIS deconvolution analysis obtained by GSPC- CHI3L1 and GSPC- CHI3L2 in AD males and female brains. The intersection of genes list positively (GSPC) correlated to CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in brain of AD patients to twelve signatures of CNS cells and the immune cells (NIS), both in males (a) and females (b). The genes in common obtained from the overlaps are expressed in percentages and represented as bar charts. The p-value obtained by Fisher's test is expressed as neglog10 (p-value) and represented as lines charts. The red points represent the non-significant percentage intersections. P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant (neglog10(p-value)> 1.30)

The analysis showed that genes related to the expression of the two chitinases delineated similar brain cell profiles in AD males (Fig. 3a), and females (Fig. 3b). Specifically, as regards the list of GSPC-CHI3L1-males, significant intersections with neuroimmune signatures were highlighted for the cellular signatures of the astrocyte (ngene = 69, n%= 38.98, neglog10 (pvalue) = 20.60, RF = 3.40), endothelial cells (ngene = 31, n%= 56.36, neglog10 (pvalue) = 15.06, RF = 4.92), microglia (ngene = 63, n%= 67.74, neglog10 (pvalue) = 36.79, RF = 5.91), pericyte inflammatory (ngene = 46, n%= 22.33, neglog10 (pvalue) = 5.21, RF = 1.94), M1 macrophages (ngene = 175, n%= 25.96, neglog10 (pvalue) = 25.73, RF = 2.26), and M2 macrophages (ngene = 35, n%= 26.51, neglog10 (pvalue) = 5.86, RF = 2.31) (Fig. 3a). Regarding the excluded NIS, such as neurons, oligodendrocytes, CTLs, natural killer (NK), Th1, and Th2 cells, the RF value was <1, so the intersections differed significantly from the individual processes (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 3a).

The NIS were also intersected to the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-males (Fig. 3a). The intersection highlighted significant overlaps with signatures of astrocyte (ngene = 52, n%= 21.37, neglog10 (pvalue) = 13.92, RF = 3.21), endothelial cells (ngene = 16, n%= 29.09, neglog10 (pvalue) = 4.68, RF = 3.18), microglia (ngene = 56, n%= 60.21, neglog10 (pvalue) = 33.92, RF = 6.59), pericyte inflammatory (ngene = 35, n%= 16.99, neglog10 (pvalue) = 3.60, RF = 1.85), M1 macrophages (ngene = 147, n%= 21.81, neglog10 (pvalue) = 23.38, RF = 2.38), and M2 macrophages (ngene = 21, n%= 15.90, neglog10 (pvalue) = 2.06, RF = 1.74) (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 3a). For the NIS belonging to neurons, oligodendrocytes, CTLs, NK, Th1, and Th2 cells, the RF value was <1, so the intersections differed significantly from the individual processes (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 3a).

As regards the list of GSPC-CHI3L1-females, significant overlaps were highlighted for the NIS profiles belonging to the astrocytes (ngene = 31, n%= 17.51, neglog10(pvalue) = 1.91, RF = 1.51), endothelial cells (ngene = 23, n%= 41.81, neglog10(pvalue) = 7.92, RF = 3.61), microglia (ngene = 65, n%= 69.98, neglog10(pvalue) = 38.99, RF = 6.03), pericyte inflammatory (ngene = 47, n%= 22.81, neglog10(pvalue) = 5.46, RF = 1.97), M1 macrophages (ngene = 194, n%= 28.78, neglog10(pvalue) = 34.42, RF = 2.48), and M2 macrophages (ngene = 30, n%= 22.72, neglog10(pvalue) = 3.69, RF = 1.96) (Fig. 3b). Regarding the excluded NIS, such as neurons, oligodendrocytes, CTLs, NK, Th1, and Th2 cells, the RF value was <1, so the intersections differed significantly from the individual processes (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 3b).

We highlighted significant overlaps between the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-females and the NIS for astrocytes (ngene = 42, n%= 23.72, neglog10 (pvalue) = 3.21, RF = 1.65), endothelial cells (ngene = 20, n%= 36.36, neglog10 (pvalue) = 4.36, RF = 2.52), microglia (ngene = 58, n%= 62.36, neglog10 (pvalue) = 25.63, RF = 4.33), oligodendrocytes (ngene = 23, n%= 24.21, neglog10 (pvalue) = 2.12, RF = 1.68), pericyte inflammatory (ngene = 40, n%= 19.11, neglog10 (pvalue) = 1.55, RF = 1.34), and M1 macrophages (ngene = 195, n%= 28.93, neglog10 (pvalue) = 22.52, RF = 2.01) (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 3b). Regarding the excluded NIS, such as neurons, CTLs, NK, Th1, and Th2 cells, the RF value was <1, so the intersections differed significantly from the individual processes (Fig. 3b).

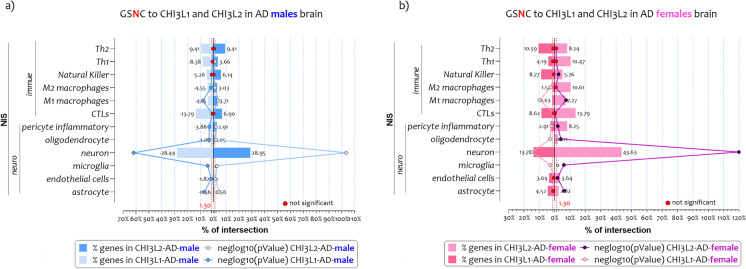

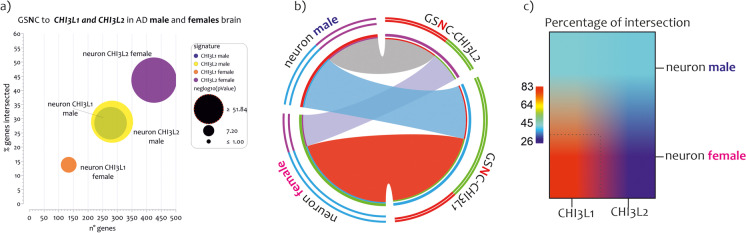

The NIS were also overlapped with the lists of genes negatively correlated with CHI3L1 (ngene= 2020) and CHI3L2 (ngene= 1406) expression levels in AD males’ brains (GSNC-CHI3L1-males, and GSNC-CHI3L2-males) (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, we also intersected the NIS with the lists of genes negatively correlated with CHI3L1 (ngene= 1380) and CHI3L2 (ngene= 2806) expression levels in AD females’ brains (GSNC-CHI3L1-males, and GSNC-CHI3L2-males) (r>0.40, strong positive relationship) (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 4.

NIS deconvolution analysis obtained by GSNC- CHI3L1 and GSNC- CHI3L2 in AD males and female brains. Overlapping of genes negatively (GSNC) correlated to CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in brain of AD patients to twelve signatures of CNS cells and the immune cells (NIS), both in males (a) and females (b). The genes in common obtained from the overlaps are expressed in percentages and represented as bar charts. The p-value obtained by Fisher's test is expressed as neglog10 (pvalue) and represented as lines charts. The red points represent the non-significant percentage intersections. P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant (neglog10(p-value)> 1.30)

The analysis showed that genes related to the expression of the two chitinases delineated similar brain expression profiles in AD males (Fig. 4a) and females (Fig. 4b). Specifically, as regards the GSNC-CHI3L1-males, significant overlaps were highlighted only for the neuronal signatures (ngene = 277, n%= 28.43, neglog10 (pvalue) = 61.90, RF = 2.84). Similar results were obtained for GSNC-CHI3L2-males (ngene = 282, n%= 28.95, neglog10 (pvalue) = 103.40, RF = 4.16). Regarding the remaining NIS excluded, the RF value was <1, so the intersections differed significantly from the individual processes (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 4a).

Regarding female profiles, we showed that genes related to the expression of the two chitinases delineated similar NIS such as in the AD males (Fig. 4b). Specifically, as regards the GSNC-CHI3L1-females, significant overlaps were highlighted only for the neuron cellular signatures (ngene = 134, n%= 13.75, neglog10 (pvalue) = 14.55, RF = 2.01). In GSNC-CHI3L2-females, similar results were obtained (ngene = 425, n%= 43.63, neglog10 (pvalue) = 119.90, RF = 3.14). Regarding the remaining NIS excluded, the RF value was <1, so the intersections differed significantly from the individual processes (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 4b).

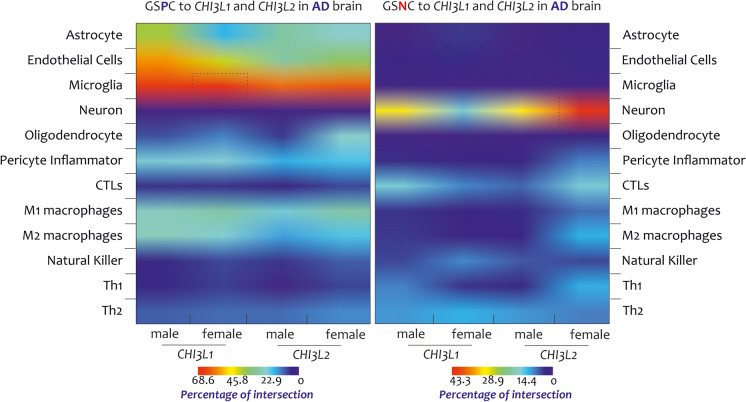

All these findings highlight the significant overlap between GS(P/N) C-CHI3L1 and GS(P/N)C-CHI3L2 and microglia, astrocyte, endothelial cells, pericyte inflammatory, and neuron NIS (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Heatmap NIS deconvolution. High percentage of intersections was found between the microglial profile and the GSPC2-male-female and GSPC1-male transcriptome. Regarding the microglia highlighted by GSPC-CHI3L1-female, and the neuron highlighted by GSNC-CHI3L2-female transcriptomes showed the high percentages of intersections. The gradient color (smaller values in blue and larger values in red) indicates the percentage of intersections by the GSPC/GSNC/CHI3L1/CHI3L2 to the NIS

Signature similarity between CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 cellular profiles

We decided to intersect the genes belonging to the NIS defined with the lists of GSPC-CHI3L1/CHI3L2, and the list of GSNC-CHI3L1/CHI3L2 to identify the percentage similarity between the two chitinases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Signature similarity

| Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profiles | Neuro-immune signature | CHI3L1 | CHI3L2 | CHI3L1 | CHI3L2 |

| GSPC | Astrocyte | 52.2 | 69.2 | 61.3 | 45.2 |

| Endothelial cells | 51.6 | 94.1 | 73.9 | 85.0 | |

| Microglia | 87.3 | 98.2 | 86.2 | 96.6 | |

| Pericyte inflammatory | 63.0 | 82.9 | 70.2 | 82.5 | |

| M1 macrophages | 72.6 | 86.4 | 77.3 | 76.9 | |

| M2 macrophages | 42.9 | 71.4 | 56.7 | 65.4 | |

| GSNC | Neuron | 44.8 | 44.0 | 83.6 | 26.4 |

Our analysis showed that the NIS significantly regulated by list of GSPC-CHI3L2 in both males and females AD were largely contained in those determined by the list of GSPC-CHI3L1 (Table 4). In particular, when we compared the male profiles, the percentages of genes involved were higher for the NIS determined by the list of GSPC-CHI3L1 (67.74% microglia) (Fig. 6a) (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, the signature of the microglia identified by the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-male showed the highest percentage of transcriptomic similarity to the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-male (98.2%), while the lowest transcriptomic similarity was due to the M2 macrophages identified by the list of GSPC-CHI3L1-male signature (42.9%) (Table 4) (Supplementary Table 1) (Fig. 6b, c). Also, for the female profiles, we showed higher percentages of genes belonging to NIS significantly regulated by the list of GSPC-CHI3L1 (microglia 68.89%) (Fig. 7a) (Supplementary Table 1). Regarding the signature similarity between the profiles identified by the two chitinases, the signature of the microglia identified by the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-female showed the highest percentage of transcriptomic similarity to the list of GSPC-CHI3L1-female (96.6%), while the signature of the astrocytes identified from the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-female showed the lowest transcriptomic similarity (45.2%) (Table 4) (Fig. 7b, c) (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Signature similarity between NIS determined by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in AD males. Bubble-chart of the percentage of genes significantly involved in NIS determined by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in AD males. The different colors indicate the signatures identified by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, while the circle's size indicates neg log10 (p-value) (a). Cord-diagram of microglia-NIS identified by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 males. The red cord represents the highest genomic share (similarity between CHI3L1 and CHI3L2) (98.2% for microglia identified by the GSPC-CHI3L2-male signature) and the blue string the lowest (42.9% for M2 macrophages identified by the GSPC-CHI3L1-male signature) (b). Heat-map of signature similarity between NIS determined by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in males. The dashed boxes indicate the most regulated NIS (c)

Fig. 7.

Signature similarity between NIS determined by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in AD females. Bubble-chart of the percentage of genes significantly involved in NIS determined by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in AD females. The different colors indicate the signatures identified by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, while the circle's size indicates neg log10 (p-value) (a). Cord-diagram of microglia-NIS identified by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 females. The red cord represents the highest genomic share (similarity between CHI3L1 and CHI3L2) (96.6% for microglia identified by the GSPC-CHI3L2-female signature) and the blue string the lowest (45.2% for astrocyte identified by the GSPC-CHI3L2-female signature) (b). Heat-map of signature similarity between NIS determined by GSPC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in females. The dashed boxes indicate the most regulated NIS (c)

Regarding the neuroimmune signatures intersected significantly with GSNC-CHI3L1 and GSNC-CHI3L2 in both AD males and females, they showed data only significant for neuron signatures (Fig. 8) (Table 4). In particular, when we compared the male and female profiles identified by the two chitinases, the percentages of the genes involved were higher in the NIS determined by GSNC-CHI3L2 (28.95% for the male, and 43.63% for the female) (Fig. 8a) (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, the signature similarity of neurons identified by GNPC-CHI3L1-female showed the highest percentage of transcriptomic similarity to GSNC-CHI3L2-female (83.6%), while the signature similarities of male neurons were almost identical (44.8% for the CHI3L1-male, and 44.0 for the CHI3L2-male) (Table 4) (Fig. 8b, c).

Fig. 8.

Signature similarity between NIS determined by GSNC-CHI3L1 and GSNC-CHI3L2 in AD males and females. Bubble-chart of the percentage of genes significantly involved in NIS determined by GSNC-CHI3L1 and GSNC-CHI3L2 in AD males and females. The different colors indicate the signatures identified by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, while the circle's size indicates neg log10 (p-value) (a). Cord-diagram of microglia-NIS identified by GSNC-CHI3L1 and GSNC-CHI3L2 males and females. The red cord represents the highest genomic share (similarity between CHI3L1 and CHI3L2) (83.6% for neuron identified by the GSNC-CHI3L1-female signature) (b). Heat-map of signature similarity between NIS determined by GSNC-CHI3L1 and GSPC-CHI3L2 in males and females. The dashed boxes indicate the most regulated NIS (c)

Biological processes identified by the common genes between the microglia, and neuron signatures determined by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2

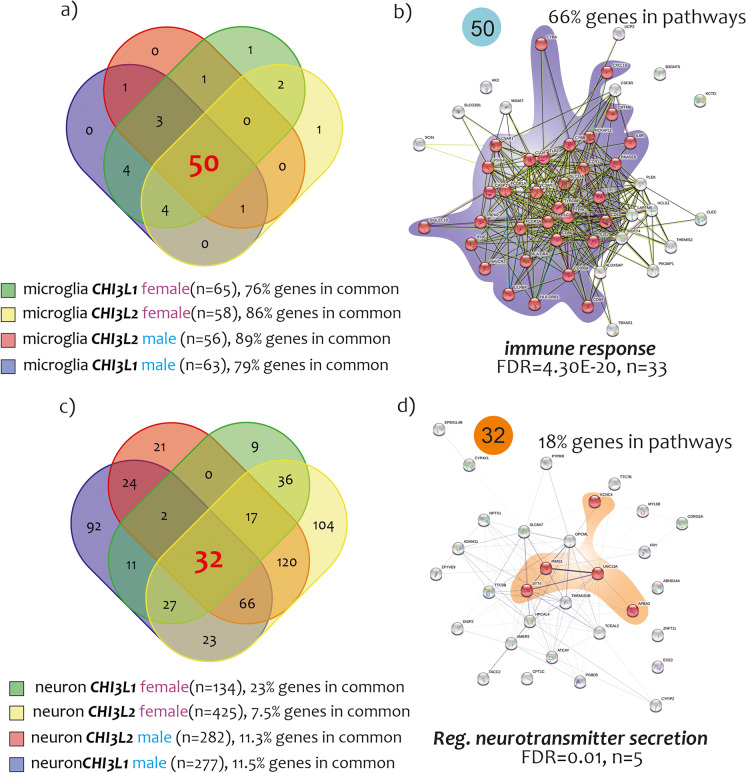

Having emerged from our results that microglia and neuron signatures were the most regulated by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, we decided to verify the genes in common between the lists GSPC-CHI3L1/2-male/female for microglia, and GSNC-CHI3L1/2-male-female for neurons. We performed a Venn’s analysis by crossing the microglia NIS signatures obtained from the GSPC-CHI3L1-male, GSPC-CHI3L1-female, GSPC-CHI3L2-male, and GSPC-CHI3L2-female data sets. The analysis showed 50 genes in common between all microglia-NIS. Regarding the 50 genes in common, the largest percentage contribution was that shared by microglia-CHI3L2-male (89%) (76% for microglia-CHI3L1-male, 86% for microglia-CHI3L2-female, and 79% for microglia-CH3L1-female) (Fig. 9a) (Supplementary Table 1). Besides, we performed a GO analysis of the 50 genes in common among the microglia-NIS (Fig. 9b). The data showed that the 66% (33 genes) were involved in biological processes of immune response (FDR = 4.30E-20, n = 33) (Fig. 9b) (Supplementary Table 1). Other processes, such as leukocyte chemotaxis (FDR = 1.47E-05, n = 7), leukocyte migration (FDR = 0.00016, n = 8), positive regulation of chemotaxis (FDR = 0.00025, n = 6), and neutrophil chemotaxis (FDR = 0.0031, n = 4), were significantly activated by the signature of the 50 genes.

Fig. 9.

GO analysis of common genes identified by the microglia and neuron signatures determined by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2. Venn’s analysis crossing the microglia NIS signatures obtained from GSPC-CHI3L1-male, GSPC-CHI3L1-female, GSPC-CHI3L2-male, and GSPC-CHI3L2-female. The analysis showed 50 genes in common between all microglia-NIS (a). GO analysis of the 50 genes in common among the microglia-NIS. The main biological process involved in activation of 50 genes was the immune response (FDR = 4.30E-20, n = 33) (b). Venn’s analysis crossing the neuron NIS signatures obtained from GSNC-CHI3L1-male, GSNC-CHI3L1-female, GSNC-CHI3L2-male, and GSNC-CHI3L2-female. The analysis showed 32 genes in common between all neuron-NIS (c). GO analysis of the 32 genes in common among the neuron-NIS. The main biological process involved in activation of 32 genes was the regulation of neurotransmitter secretion (FDR = 0.001, n = 5) (d)

Regarding the neuroimmune signatures intersected significantly with GSNC-CHI3L1-male, GSNC-CHI3L1-female, GSNC-CHI3L2-male, and GSNC-CHI3L2-female, Venn’s analysis showed 32 genes in common between all neurons-NIS (Fig. 9c) (Supplementary Table 1). Noteworthy, regarding the 32 genes in common, the largest percentage contribution was that shared by neuron-CHI3L1-female (23%) (7.5% for neuron-CHI3L2-female, 11.3% for neuron-CHI3L2-male, and 11.5% for neuron-CH3L1-male) (Fig. 9c) (Supplementary Table 1). GO analysis of the 32 genes in common between neuron-NIS (Fig. 9d) showed that 18% (5 genes) were involved in biological processes of regulation of neurotransmitter secretion (FDR = 0.001, n = 5) (Fig. 9d) (Supplementary Table 1). Another significantly modulated process was the positive regulation of dendrite extension (FDR = 0.034, n = 3) (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Our analysis revealed significantly higher CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression in AD compared with NDC, and significant positive correlations of these genes with GFAP and TMEM119, astrocytes, and microglia markers, respectively. Moreover, neuroimmune deconvolution analysis revealed that high expression of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 was linked to inflammatory signatures in males and females AD. Neuronal activation profiles were significantly activated in AD patients with low CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels. Additionally, GO analysis of common genes regulated by the two chitinases showed immune response as a main biological process. Finally, microglia NIS significantly correlated with CHI3L2 expression levels and were more than 98% similar to microglia NIS determined by CHI3L1.

In recent years, the use of datasets available in public databases has grown exponentially. Analysis of public transcriptome datasets for the identification of novel pathogenic pathways and therapeutic targets has been extensively used in a number of human pathologies [39, 78, 79], including neurodegenerative diseases [24, 39, 44, 45] and cancer [80, 81]. Through a meta-analysis of public transcriptome datasets, it is possible to increase the statistical power to obtain a more precise estimation of gene expression differentials and assess the heterogeneity of the overall estimation. Meta-analysis makes comprehensive use of already available data and represents a vast source of information that could make a difference in setting up highly targeted experimental strategies.

Elevated levels of the polymer chitin have been found in CNS, CSF, and plasma in AD patients and implicated in influencing Aβ accumulation and AD pathogenesis [82]. The involvement of chitinases in immune-mediated degenerative processes is currently a hot topic. There are large studies on CHI3L1 as CSF biomarker that increases with aging and early in AD, much less so regarding CHI3L2 [83]. Currently, the two chitinases, at the CNS level, are considered purely astrocytic proteins [84, 85]; nevertheless, a strong microglial regulation emerges from our data. We aimed to profile the AD patient’s brains according to their CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels, and subsequently, highlight AD-NIS sex-dependence. We found a significant increase in CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in AD patients compared to NDC subjects. These data are closely aligned with previous results from other research groups demonstrating variations of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels in CSF of AD patients [83]. Specifically, we confirmed the presence of CHI3L1, CHI3L2, CHID1, and CHIT1 in the brains of AD patients, also revealing for the first time a sex-linked difference in CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels. Consistently, differences appeared in GSPC of CHI3L1. Males were distinguished by more than the double of genes overlapping for NIS profiles belonging to astrocytes in comparison to females. Indeed, 23 genes overlapped between the list of GSPC-CHI3L2 and NIS for oligodendrocytes, whereas a similar overlap did not emerge in males. On the same trend, in terms of pronounced difference between males and females, it is the virtually absence of overlaps between the list of GSPC-CHI3L2-females and NIS for M2 macrophages. These divergences between the two sexes deserve deeper studies.

Recently, we proved a positive correlation between CHI3L2 and the microglia-mediated neuroinflammation (IBA1), alteration of the blood-brain barrier (PECAM1), and neuronal damage (CALB1) expression levels, further corroborating the positive correlation that exists between CHI3L2 and its homolog CHI3L1 [25]. Further, expression analysis of another chitinase, CHID1, showed opposite behavior to CHI3L1 and CHI3L2. Indeed, the CHID1 expression levels in the brains of AD patients were positively correlated with CALB1 and neurogranin (NRGN), suggesting a function closer to neurons than to astrocytes/microglia/endothelial cells, typical of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 [74].

Interestingly, expression levels of the two chitinases had a higher r Pearson index for GFAP than for TMEM119, as well as r Pearson index higher for CHI3L2 compared with CHI3L1. This finding further supports the hypothesis that CHI3L1, and its homolog CHI3L2, are astroglia proteins whose function is expressed on target cells such as microglia [86].

CHI3L1 is not only expressed in astrocytes, but also in reactive and neurotoxic astrocytes, which are induced by microglia [87]. It can also regulate microglial activation states that may induce neuronal death [86]. Indeed, here we have found that NIS overlap between those identified by GS(P/N) C-CHI3L1 and GS(P/N) C-CHI3L2, particularly striking in microglia, astrocyte, endothelial cells, pericyte inflammatory, M1 macrophages, and neuron signatures. On the one hand, GSPCs to CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 characterize astrocytic cells; on the other hand, they could have microglia, inflammatory pericytes, M1 macrophages, and endothelial cells as activation targets. CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 could modulate the expression and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from glial cells, resulting in BBB disruption (Supplementary Table 1). CHI3L1 has been shown to be involved in BBB disruption and remodeling of the blood vasculature in AD, confirming the modulation of endothelial cells and pericytes highlighted here [88]. Furthermore, the percentage of similarity between microglial and neuronal signatures indicated that the microglial transcripts identified by positively correlation to CHI3L2 (microglia-CHI3L2) were almost completely overlapping with that identified by CHI3L1 (microglia-CHI3L1), both in male and female AD patients, suggesting a similar role played by the two chitinases at the level of AD microglia regulation. It has been shown that CHI3L1 plays a direct role in neurons [89]. When we analyzed the NIS highlighted by the signatures negatively correlated with the expression of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, we found significant modulation only for genes characterizing the neurons. When we measured the percent degree of overlap, we found that those identified by the female signature of CHI3L1 (neuron-CHI3L1-female) were entirely overlapping with those of CHI3L2 (neuron-CHI3L2-female), suggesting a more prominent neuronal role for the negatively related genes of CHI3L2.

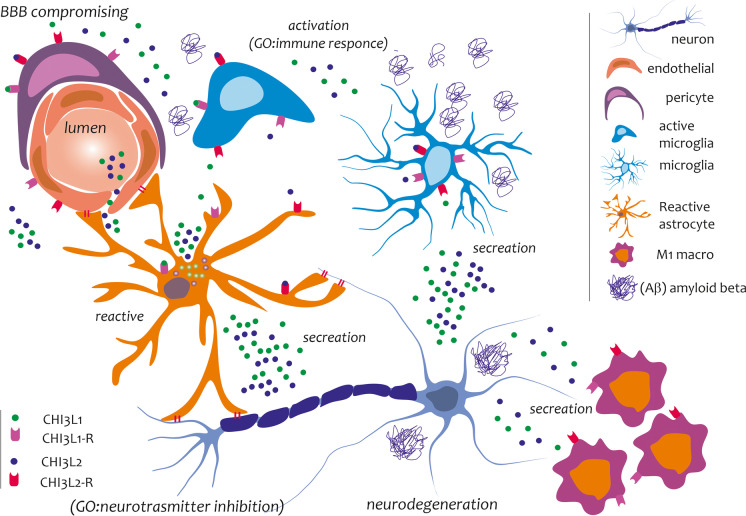

We hypothesize that CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 function as neuronal cytokines mediating neuroinflammatory processes in order to trigger receptors expressed on target brain cells (astrocyte, microglia, pericytes, endothelial cells, and M1) and regulating innate inflammatory responses. CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 would play an essential role in the communication dynamics between microglia and astrocytes during neuroinflammation. Their action on endothelial cells and pericytes could contribute to the compromised integrity of the BBB, a process observed in AD patients. Yet, another effect potentially played by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 could be the direct one on neurons, that we indirectly unveiled, and in which cell death phenomena is linked to synapse loss, as well as to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and to the appearance of well-defined neurodegenerative features prior to overt plaque and tangle formation [90]. This cumulative evidence led us to hypothesize that the two chitinases, CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, likely play a similar role in the brains of AD patients (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Potential role played by CHI3L1 and ChI3L2 in AD brain. CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 may be cytokines that mediate neuroinflammatory processes to trigger receptors expressed on target brain cells (microglia, pericytes, endothelial cells) and regulate innate inflammatory responses (M1 macrophages)

Our investigations revealed cells profiles similarities identified in AD brains based on the expression levels of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2, suggesting a similar role played by the two chitinases. These similarities would suggest an increase in the regulatory activity of microglia, pericytes, and endothelial cells by astrocytes through the function of the two chitinases. Further studies will be needed to corroborate the neuroinflammatory role played by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in human brain. Being able to characterize the signal transduction mechanisms operated by CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 on CNS cells leading to neuroinflammation could provide opportunities for the development of new drugs for the treatment of patients with AD or affected by other neurodegenerative diseases.

Finally, our study presents some limitations. Our analyses did not consider any AD severity scale. The analysis we conducted suggested potential targets for further deepening. The pathological links with CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 expression levels do not have a causal component. We cannot exclude that confounders might influence the relationship between the high-expression of CHI3L1-2 and that of other genes. Nevertheless, our data represent a starting component to investigate new AD facets.

Supplementary Information

Data analysis (XLSB 244 kb)

Age correlation (PNG 344 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our gratitude to the authors of microarray datasets made available online, for consultation and re-analysis. We would like to thank Led Zeppelin for inspiring us to write this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- MD

Microarray datasets

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- MeV

MultiExperiment Viewer

- FDR

False discovery rate

- CNS

Central nervous system

- NFTs

Neurofibrillary tangles

- NDC

Not demented control subjects

- HCEG

High CHI3L1 expression group

- LCEG

Low CHI3L1 expression group

- GSPC

Genes significant positive correlated

- GSNC

Genes significant negative correlated

- SDEG

Significantly different expressed genes

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- GDA

Genomic deconvolution analysis

- GSPC-CHI3L1

Genes significantly positively correlated to CHI3L1

- GSNC-CHI3L1

Genes significantly negatively correlated to CHI3L1

Author contribution

The study was conceptualized and designed by Michelino Di Rosa. The original manuscript was written by Michelino Di Rosa, Cristina Sanfilippo, Paola Castrogiovanni, and Manlio Vinciguerra. Data curation was performed by Manlio Vinciguerra, Martina Ulivieri, Francesco Fazio, Rosa Imbesi, Kaj Blennow, and Henrik Zetterberg. Methodology and formal analysis were performed by Cristina Sanfilippo, and Paola Castrogiovanni. The manuscript was revised and improved by Michelino Di Rosa, Manlio Vinciguerra, Kaj Blennow, and Henrik Zetterberg. All co-authors aided in interpretation of the results and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the University Research Project Grant (PIACERI 2020–2022), Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences (BIOMETEC), University of Catania, Italy, and by the European Social Fund and European Regional Development Fund – Project MAGNET (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000492). The funder/sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the GEODaset repository, Home - GEODataset - NCBI (nih.gov).

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable. The ethics approval and consent to participate were requested by the authors of the original datasets shown in Table 1, and subsequently analyzed in our study.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(8):a006239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Gurwitz D. Auguste D and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1997;350(9073):298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang WY, et al. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(10):136. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medeiros R, LaFerla FM. Astrocytes: conductors of the Alzheimer disease neuroinflammatory symphony. Exp Neurol. 2013;239:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Khoury JB, et al. CD36 mediates the innate host response to beta-amyloid. J Exp Med. 2003;197(12):1657–1666. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steardo L, Jr, et al. Does neuroinflammation turn on the flame in Alzheimer's disease? Focus on astrocytes. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:259. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):358–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, et al. Interplay between microglia and Alzheimer's disease-focus on the most relevant risks: APOE genotype, sex and age. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:631827. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.631827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schain M, Kreisl WC. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders-a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(3):25. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solito E, Sastre M. Microglia function in Alzheimer's disease. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:14. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanegawa N, et al. In vivo evidence of a functional association between immune cells in blood and brain in healthy human subjects. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;54:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colombo E, Farina C. Astrocytes: key regulators of neuroinflammation. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(9):608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott NJ. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions and blood-brain barrier permeability. J Anat. 2002;200(6):629–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagele RG, et al. Astrocytes accumulate A beta 42 and give rise to astrocytic amyloid plaques in Alzheimer disease brains. Brain Res. 2003;971(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henrissat B, Davies G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7(5):637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eide KB, et al. The role of active site aromatic residues in substrate degradation by the human chitotriosidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1864(2):242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonneh-Barkay D, et al. Astrocyte and macrophage regulation of YKL-40 expression and cellular response in neuroinflammation. Brain Pathol. 2012;22(4):530–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Rosa M, et al. Chitotriosidase and inflammatory mediator levels in Alzheimer's disease and cerebrovascular dementia. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(10):2648–2656. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris VK, Sadiq SA. Biomarkers of therapeutic response in multiple sclerosis: current status. Mol Diagn Ther. 2014;18(6):605–617. doi: 10.1007/s40291-014-0117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varghese AM, et al. Chitotriosidase - a putative biomarker for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Proteomics. 2013;10(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teitsdottir UD, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid C18 ceramide associates with markers of Alzheimer's disease and inflammation at the pre- and early stages of dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;81(1):231–244. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter SF, et al. Astrocyte biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25(2):77–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanfilippo C, et al. Sex difference in CHI3L1 expression levels in human brain aging and in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2019;1720:146305. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanfilippo C, Malaguarnera L, Di Rosa M. Chitinase expression in Alzheimer's disease and non-demented brains regions. J Neurol Sci. 2016;369:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanfilippo C, et al. CHI3L2 Expression levels are correlated with AIF1, PECAM1, and CALB1 in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Mol Neurosci. 2020;70(10):1598–1610. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01667-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehli M, et al. Transcriptional regulation of CHI3L1, a marker gene for late stages of macrophage differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(45):44058–44067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alcolea D, et al. Relationship between cortical thickness and cerebrospinal fluid YKL-40 in predementia stages of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(6):2018–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alcolea D, et al. Relationship between beta-secretase, inflammation and core cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(1):157–167. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonell A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid level of YKL-40 protein in preclinical and prodromal Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(3):901–908. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig-Schapiro R, et al. YKL-40: a novel prognostic fluid biomarker for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(10):903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melah KE, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer's disease pathology and microglial activation are associated with altered white matter microstructure in asymptomatic adults at risk for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50(3):873–886. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Querol-Vilaseca M, et al. YKL-40 (Chitinase 3-like I) is expressed in a subset of astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0893-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Rosa M, et al. Evaluation of CHI3L-1 and CHIT-1 expression in differentiated and polarized macrophages. Inflammation. 2013;36(2):482–492. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Rosa M, et al. CHI3L1 nuclear localization in monocyte derived dendritic cells. Immunobiology. 2016;221(2):347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Rosa M, et al. Determination of chitinases family during osteoclastogenesis. Bone. 2014;61:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu QC, et al. CHI3L1 promotes tumor progression by activating TGF-beta signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15029. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33239-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litviakov N, et al. Expression of M2 macrophage markers YKL-39 and CCL18 in breast cancer is associated with the effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;82(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Rosa M, et al. Prolactin induces chitotriosidase expression in human macrophages through PTK, PI3-K, and MAPK pathways. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107(5):881–889. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanfilippo C, et al. The chitinases expression is related to Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Encephalitis (SIVE) and in HIV encephalitis (HIVE) Virus Res. 2017;227:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanfilippo C, et al. CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 overexpression in motor cortex and spinal cord of sALS patients. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2017;85:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wurm J, et al. Astrogliosis releases pro-oncogenic chitinase 3-like 1 causing MAPK signaling in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Mollgaard M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid chitinase-3-like 2 and chitotriosidase are potential prognostic biomarkers in early multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(5):898–905. doi: 10.1111/ene.12960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malaguarnera L, et al. Action of prolactin, IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha and LPS on heme oxygenase-1 expression and VEGF release in human monocytes/macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5(9):1458–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castrogiovanni P, et al. Fasting and fast food diet play an opposite role in mice brain aging. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(8):6881–6893. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0891-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanfilippo C, et al. Middle-aged healthy women and Alzheimer's disease patients present an overlapping of brain cell transcriptional profile. Neuroscience. 2019;406:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao J, Cao H, Chen J. False discovery rate control incorporating phylogenetic tree increases detection power in microbiome-wide multiple testing. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(18):2873–2881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis S, Meltzer PS. GEOquery: a bridge between the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(14):1846–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuberi K, et al. GeneMANIA prediction server 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41(Web Server issue): W115-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang JT, Nevins JR. GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomic signatures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(23):2926–2933. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang M, et al. Integrative network analysis of nineteen brain regions identifies molecular signatures and networks underlying selective regional vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guijarro-Munoz I, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated NF-kappaB signaling pathway and proinflammatory response in human pericytes. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(4):2457–2468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.521161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbas AR, et al. Immune response in silico (IRIS): immune-specific genes identified from a compendium of microarray expression data. Genes Immun. 2005;6(4):319–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castrogiovanni P, et al. Chitinase domain containing 1 increase is associated with low survival rate and M0 macrophages infiltrates in colorectal cancer patients. Pathol Res Pract. 2022;237:154038. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Rodwell GE, et al. A transcriptional profile of aging in the human kidney. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(12):e427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Sanfilippo C, et al. Hippocampal transcriptome deconvolution reveals differences in cell architecture of not demented elderly subjects underwent late-life physical activity. J Chem Neuroanat. 2021;113:101934. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Box GEP, Tiao GC. Bayesian Inference in Statistical Analysis. Addison-Wesley. 1992;1(1):603.

- 59.Cheadle C, et al. Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J Mol Diagnostics JMD. 2003;5(2):73–81. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Care MA, et al. A microarray platform-independent classification tool for cell of origin class allows comparative analysis of gene expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J, et al. Differences in gene expression between B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and normal B cells: a meta-analysis of three microarray studies. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3166–3178. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reddy TB, et al. TB database: an integrated platform for tuberculosis research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D499–D508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Le Cao KA, et al. YuGene: a simple approach to scale gene expression data derived from different platforms for integrated analyses. Genomics. 2014;103(4):239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen QR, et al. An integrated cross-platform prognosis study on neuroblastoma patients. Genomics. 2008;92(4):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yasrebi H, et al. Can survival prediction be improved by merging gene expression data sets? PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mehmood R, et al. Clustering by fast search and merge of local density peaks for gene expression microarray data. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45602. doi: 10.1038/srep45602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheadle C, et al. Application of z-score transformation to Affymetrix data. Appl Bioinforma. 2003;2(4):209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feng C, et al. Expression of Bcl-2 is a favorable prognostic biomarker in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(5):6925–6930. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kang C, et al. Feature selection and tumor classification for microarray data using relaxed Lasso and generalized multi-class support vector machine. J Theor Biol. 2019;463:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zetterberg H, et al. Neurofilaments in blood is a new promising preclinical biomarker for the screening of natural scrapie in sheep. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Z, et al. The appropriate marker for astrocytes: comparing the distribution and expression of three astrocytic markers in different mouse cerebral regions. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:9605265. doi: 10.1155/2019/9605265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Satoh J, et al. TMEM119 marks a subset of microglia in the human brain. Neuropathology. 2016;36(1):39–49. doi: 10.1111/neup.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kenkhuis B, et al. Co-expression patterns of microglia markers Iba1, TMEM119 and P2RY12 in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2022;167:105684. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Castrogiovanni P, et al. Brain CHID1 Expression Correlates with NRGN and CALB1 in Healthy Subjects and AD Patients. Cells. 2021;10(4):882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Sanfilippo C, et al. Postsynaptic damage and microglial activation in AD patients could be linked CXCR4/CXCL12 expression levels. Brain Res. 2020;1749:147127. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Motta M, et al. Altered plasma cytokine levels in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with the disease progression. Immunol Lett. 2007;114(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Malaguarnera L, et al. Interleukin-18 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 plasma levels in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Neuropathology. 2006;26(4):307–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Catrogiovanni P, et al. The expression levels of CHI3L1 and IL15Ralpha correlate with TGM2 in duodenum biopsies of patients with celiac disease. Inflamm Res. 2020;69(9):925–935. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanfilippo C, et al. OAS Gene family expression is associated with HIV-related neurocognitive disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(3):1905–1914. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Di Rosa M, et al. Immunoproteasome genes are modulated in CD34(+) JAK2(V617F) mutated cells from primary myelofibrosis patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Di Rosa M, et al. Different pediatric brain tumors are associated with different gene expression profiling. Acta Histochem. 2015;117(4-5):477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lomiguen C, et al. Possible role of chitin-like proteins in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):439–444. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hong S, et al. TMEM106B and CPOX are genetic determinants of cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer's disease biomarker levels. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(10):1628–1640. doi: 10.1002/alz.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lananna BV, et al. Chi3l1/YKL-40 is controlled by the astrocyte circadian clock and regulates neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(574):eaax3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Hinsinger G, et al. Chitinase 3-like proteins as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21(10):1251–1261. doi: 10.1177/1352458514561906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Connolly K, et al. Potential role of chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1/YKL-40) in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;10.1002/alz.12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Clarke LE, et al. Normal aging induces A1-like astrocyte reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(8):E1896–E1905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800165115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moreno-Rodriguez M, et al. Frontal cortex chitinase and pentraxin neuroinflammatory alterations during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-1723-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matute-Blanch C, et al. Chitinase 3-like 1 is neurotoxic in primary cultured neurons. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7118. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liddelow SA, Barres BA. Reactive astrocytes: production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity. 2017;46(6):957–967. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data analysis (XLSB 244 kb)

Age correlation (PNG 344 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the GEODaset repository, Home - GEODataset - NCBI (nih.gov).