Abstract

Background: While Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) has a prevalence as high as 3-32% and is associated with cognitive dysfunction and the risk of institutionalization, no efficacious and acceptable treatments can modify the course of cognitive decline in AD. Potential benefits of exogenous melatonin for cognition have been divergent across trials.

Objective: The current network meta-analysis (NMA) was conducted under the frequentist model to evaluate the potential beneficial effects of exogenous melatonin supplementation on overall cognitive function in participants with AD in comparison to other FDA-approved medications (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, and Namzaric).

Methods: The primary outcome was the changes in the cognitive function [measured by mini-mental state examination (MMSE)] after treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. The secondary outcomes were changes in the quality of life, behavioral disturbance, and acceptability (i.e., drop-out due to any reason and rate of any adverse event reported).

Results: The current NMA of 50 randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) revealed the medium-term low-dose melatonin to be associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE (mean difference = 1.48 in MMSE score, 95% confidence intervals [95% CIs] = 0.51 to 2.46) and quality of life (standardized mean difference = -0.64, 95% CIs = -1.13 to -0.15) among all of the investigated medications in the participants with AD. Finally, all of the investigated exogenous melatonin supplements were associated with similar acceptability as was the placebo.

Conclusion: The current NMA provides evidence for the potential benefits of exogenous melatonin supplementation, especially medium-term low-dose melatonin, in participants with AD.

Trial Registration: The current study complies with the Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGHIRB: B-109-29) and had been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020193088).

Keywords: Alzheimer’s dementia, quality of life, cognition, network meta-analysis, dementia, melatonin, circadian rhythm, psychiatry

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s dementia is a highly prevalent disease that increases with age, with a prevalence rate of 3% in those aged 65-74, 17% in those aged 75-84, and 32% in those over 85 [1]. Cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s dementia patients is frequently accompanied by behavioral disturbances, depressive mood, and impaired quality of life [2], which increase caregivers’ burden and the risk of institutionalization [3-5]. To date, several pharmacologic treatments, such as cholinesterase inhibitors, targeting cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s dementia, have been proposed but with unsatisfying results and adverse effects [6]. Developing an effective and tolerable pharmacologic treatment to alleviate cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia is an urgent need in clinical practice [6].

Melatonin, which is endogenously secreted from the pineal gland and plays an important role in modulating circadian rhythms [7], has attracted clinicians’ attention to the management of Alzheimer’s dementia [3, 8, 9]. The disturbance of circadian pacemakers in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) contributes to cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia [10, 11]. Insufficient secretion of melatonin, which is frequently found in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia [12-14], is associated with circadian dysfunction [15].

Prior randomized controlled trials (RCTs) attempted to demonstrate the potential benefits of restoring circadian rhythm through exogenous melatonin supplementation on cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. For example, previous RCTs using low dose (2 mg to 2.9 mg) exogenous melatonin supplementation demonstrated significant improvements in cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia compared to placebos [16, 17]. Furthermore, long-term melatonin use could ameliorate cognitive decline along with aging in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia [3]. However, another RCT with short-term high-dose melatonin (10 mg) did not provide significant results in cognitive outcomes [18]. In addition, traditional meta-analyses, by pooling all of the different dosages and treatment durations of exogenous melatonin supplementation into one group, revealed insignificant benefits of exogenous melatonin on cognition in patients with dementia [19-23]. Although, in 2021, the traditional meta-analysis by Sumsuzzman et al. [24] demonstrated that the melatonin significantly improved mini-mental status examination (MMSE) score in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s dementia, some methodological concerns should be addressed. First, that meta-analysis pooled all different dosages and treatment durations of melatonin into one group to calculate the effect size. Second, that previous meta-analysis merged all different diagnoses into one group (i.e., Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment). Third, that previous meta-analysis did not make further comparison with other pharmacologic treatments for cognitive function. Therefore, the dose and duration associated efficacy of exogeneous melatonin supplement in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia still remains unclear.

Previous studies show that exogenous melatonin supplementation exerts different effects depending on the dosage. Specifically, a low dose is generally thought to have a “high physiological” and “low pharmacological” effect, whereas a high dose is considered to have a “high pharmacological” effect [25-28]. Furthermore, different treatment durations of exogeneous melatonin supplementation exert different effects on cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia [3]. Therefore, it is more appropriate to consider different dosages and treatment durations of exogenous melatonin as different groups in clinical practice. NMA of existing RCTs enables the estimation of the comparative effectiveness and the understanding of the relative merits of multiple interventions, as well as maximizing statistical power, which cannot be achieved with traditional pairwise meta-analyses [29, 30]. Considering these issues, we conducted an NMA of the published RCTs by estimating the relative effectiveness and acceptability of different dosages and treatment durations of exogeneous melatonin supplementation to elucidate the potential role of melatonin in ameliorating cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. General Study Guidelines

The current NMA followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [31] (Supplement Table S1 (5.1MB, pdf) ) and the AMSTAR 2 appraisal tool [32]. The current study complies with the Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGHIRB: B-109-29) and had been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020193088).

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

In the current NMA, our search strategy consisted of two stages. In the first stage, we conducted a systematic review using ClinicalKey, Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, ProQuest, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science databases from inception to June 18th, 2020, and finally, the search was updated in August 29th, 2021. In addition, to search for unpublished studies, we also made a search on the platform of ClinicalTrials.gov (Supplement Table S2 (5.1MB, pdf) ). In the second stage, to include evidence about the efficacy/safety of the FDA-approved oral forms of agents used for episodic migraine management, we conducted an extra search to find RCTs of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, and Namzaric for the management of Alzheimer’s dementia. No language restriction was used. Additionally, manual searches were performed for potentially eligible articles selected from the reference lists of review articles, clinical guidelines, and pairwise meta-analyses [8, 9, 19-24, 33-44].

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) setting of the current meta-analysis included: (1) P: patients with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia; (2) I: exogenous melatonin supplement (in the part of the extra-search stage for dementia pharmacologic surveillance, the “I” would be the active pharmacologic intervention to alleviate cognitive decline); (3) C: placebo-control; and (4) O: the change in cognitive function. To reduce the heterogeneity, we only included RCTs recruiting patients with Alzheimer’s dementia but not mild cognitive impairment. Also, to reduce the potential bias of the placebo effect, we only included published double-blind placebo-controlled RCTs. The inclusion criteria applied in the current NMA included (1) RCTs conducted on patients with Alzheimer’s dementia, (2) formally published, (3) trials investigating the efficacy of melatonergic agents, donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, or Namzaric on outcomes of interest, and (4) trials recruiting participants with Alzheimer’s dementia only. Therefore, those RCTs consisting of mild cognitive impairment were not included.

The exclusion criteria were those studies (1) not a clinical trial, (2) not an RCT, (3) not reporting the target outcomes, or (4) not related to melatonergic agents, donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, or Namzaric. In cases of duplicated data usage (different articles based on the same sample sources), we included only the article with the largest sample source.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two authors (P.T. Tseng and B.Y. Zeng) independently screened the studies and extracted the relevant information from the manuscripts. In cases of discrepancy, the corresponding author (Y.W. Chen) was consulted. If data were missing from published reports, the corresponding authors or co-authors were contacted to obtain the additional data. We followed a priori-defined unpublished protocol (available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author) and flowcharts used in previous NMAs [28, 45-55].

2.5. Node Definition

Because exogenous melatonin supplementation exerts a different physiological effect according to the dosage (a low melatonin dosage is generally thought to have a “high physiological” and “low pharmacological” effect, whereas a high dose is considered to have a “high pharmacological” effect with a sleep-promoting effect) [25-28], we categorized the melatonin supplementation into “low-dosage,” “medium-dosage,” and “high-dosage” groups but did not merge all of the melatonin supplementations into one group (Supplement Table 3 (5.1MB, pdf) ). Also, because the different dosages of individual dementia-managing medication exert different efficacy on cognition in Alzheimer’s dementia [41], we subgrouped the individual dementia-managing medications according to their dosages. The detailed subgrouping of individual regimens is depicted in Supplement Table S3 (5.1MB, pdf) based on the dosage subgroup basis by Dou et al. [41]. Further, in a previous report [56], the different efficacy of dementia-managing medications in cognition has been found in different stratifications of treatment durations. Therefore, we categorized the treatment arms according to different treatment durations defined by the previous report, that is, “short term (less than 6 months),” “medium term (at least 6 months but less than 1 year),” “long term (at least one year but less than 2 years),” and “extremely long term (at least 2 years)” [56].

2.6. Outcomes

2.6.1. Primary Outcomes

The primary outcome was changes in cognitive function measured by the MMSE after treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. We used the MMSE as our primary outcome measure for the reasons outlined as follows. (1) The MMSE scores had approximately linear relationships with the quality of life scores (association between Assessment of Quality of Life scale and MMSE scores: r = 0.30, p < 0.0001) [57]. (2) The MMSE has been widely used and approved to serve as a surrogate for other time-consuming methods of staging dementia, such as the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [58]. (3) The initial MMSE score was significant for determining the time to clinically meaningful decline during longitudinal follow-up [59]. Similarly, the MMSE total score can serve as an index of disease progression and sequence of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia [60]. (4) The MMSE was suitable to evaluate patients with Alzheimer’s dementia in a wide range of severity; conversely, the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognition subscale (ADAS-cog) was only suitable for patients with MMSE scores of at least 14 in accordance with the results of previous research [61]. If any of the potentially eligible RCTs did not provide MMSE measurements, we extracted the other secondary outcome data in our NMA, such as changes in quality of life, changes in behavioral disturbances, and acceptability data.

2.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes were the changes in quality of life and behavioral disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. The acceptability was calculated using the dropout rate and rate of any adverse events reported by the principals of intention-to-treat analyses. Specifically, the dropout rate was defined as the percentage of patients dropping out for any reason before study completion.

2.7. Cochrane Risk-of-bias Tool and GRADE Ratings

Two independent authors (P.T. Tseng and Y.W. Chen) evaluated the risk of bias (interrater reliability, 0.85) for each domain described in the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [62]. We evaluated the certainty of the evidence, including transitivity, precision, and coherence, according to the GRADE framework and previous network meta-analysis by Cipriani et al. [63, 64].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, we estimated the effect size (ES) using the standardized mean difference (StMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To provide more clinically relevant information to clinicians, we calculated the ES of primary outcomes (MMSE) using the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. From the view of clinical practice, the difference between StMD and MD was the clinical meaning. To be specific, from StMD, the clinicians could only know whether there is a statistical significance or not. However, they could not know to what extent this difference is. On the contrary, the MD could tell the clinicians both “whether statistical significance or not” and “to what extent this difference is”. For the categorical variables, we used the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI (the acceptability) and applied a 0.5-zero-cell correction during the meta-analysis. However, if zeroes were present in both the intervention and control arms of one study, we did not apply this correction procedure because of the risk of increasing the bias; instead, these studies were excluded from our analysis [65, 66]. We used the frequentist model of NMA to compare the ES of studies with similar interventions. All of the comparisons were conducted using a two-tailed t-test, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity among the included studies was evaluated using the tau value, which was the estimated standard deviation of the effect across the included studies.

We used mixed comparison with generalized linear models to make direct and indirect comparisons [67]. Specifically, indirect comparisons were conducted using transitivity, in which the differences between treatments A and B could be calculated from the comparisons of treatments A versus C and treatments C versus B. To compare multiple treatment arms, we combined the direct and indirect evidence from the included studies [68]. STATA version 16.0 (StataCorp Statistics/Data Analysis, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used in our NMA with the mvmeta command [69]. The restricted maximum likelihood method was used to evaluate the between-study variances [70].

To provide additional information for clinical applications, we calculated the relative ranking probabilities of the treatment effects of all of the treatments for the target outcomes. In brief, the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) indicated the percentage of the mean rank of each treatment relative to an imaginary intervention that was the best without uncertainty [71]. When the area under the curve was smaller, the treatment deserved a higher rank of benefit on the cognition in participants with Alzheimer’s dementia.

We evaluated the potential inconsistencies between the direct and indirect evidence within the network using the loop-specific approach and identified local inconsistencies via the node-splitting method. The design-by-treatment model was used to evaluate global inconsistencies across the entire NMA [72]. We used comparison-adjusted funnel plots and Egger’s regression to evaluate the potentially small study effects in the order of efficacy of individual treatments [73]. Because of the potentially different placebo effects on primary outcomes (cognition measured by the MMSE) in different treatment durations [3], we assessed the effectiveness of the different durations of placebo therapy as additional proof of transitivity in primary outcomes following the rationale and statistical procedure in previous NMA studies [74, 75]. In brief, we computed and compared the difference in the changes in cognition by “short-term,” “medium-term,” “long-term,” and “extremely long-term” duration of placebo therapy using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). In situations with significantly different placebo effects among different treatment durations, we arranged further analyses to focus on RCTs according to subgroups with different treatment durations. In addition, to exclude potential confounding effects by concomitant prescriptive medications with effects on cognition, we arranged a subgroup analysis focusing on RCTs that excluded prescriptive medications with effects on cognition.

3. RESULTS

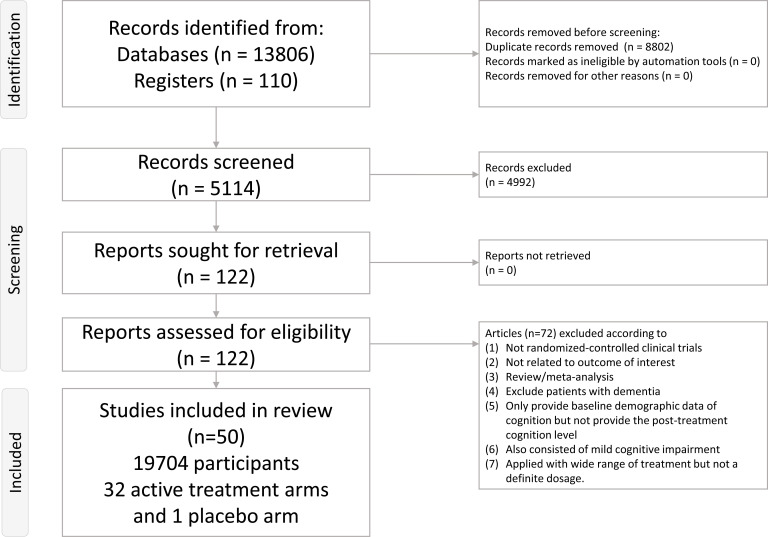

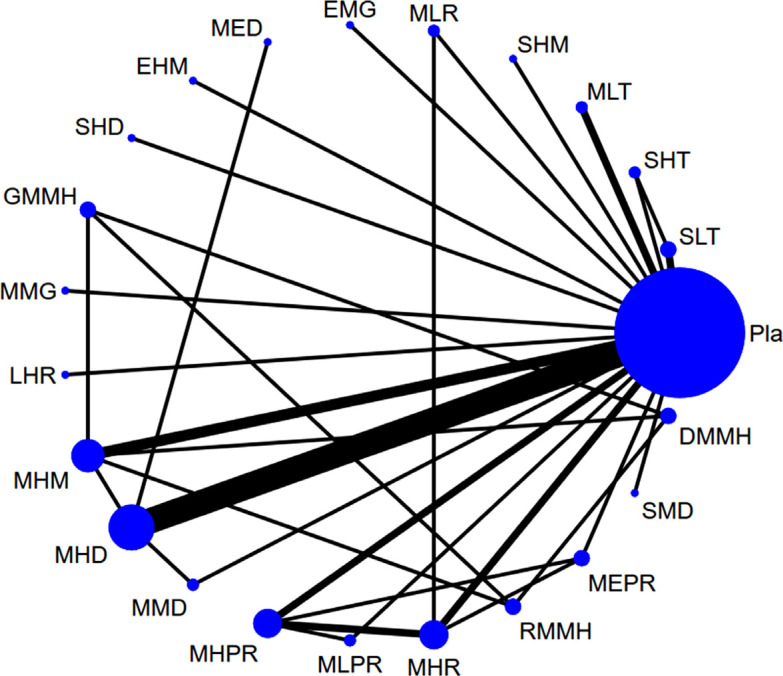

A total of 122 articles were considered in the full-text review (Fig. 1), of which 68 were excluded for some reasons (Supplement Table S4 (5.1MB, pdf) ) [8, 9, 19-24, 33-44, 76-127]. Ultimately, 50 articles were included (Supplement Table S5 (5.1MB, pdf) ) [15-18, 128-173]. Fig. (2) depicts the entire geometric distribution of the treatment arms.

Fig. (1).

Flowchart of the current network meta-analysis. Figure 1) depicts the entire flowchart of the current network meta-analysis.

Fig. (2).

The network structure of changes in cognitive function. Figure 2) depicts the overall network structure of the current network meta-analysis of changes in cognitive function. The lines between nodes represent direct comparisons in various trials, and the size of each circle is proportional to the size of the population involved in each specific treatment. The thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of trials connected to the network.

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

A total of 19,704 participants were included. The mean age of the participants was 75.1 years (range 65.2 to 85.7 years old), and the mean female proportion was 63.6% (range 0.0% to 85.0%). The mean treatment duration was 34.8 weeks (range 4 to 208 weeks). The baseline characteristics of the included participants are summarized in Supplement Table S5 (5.1MB, pdf) .

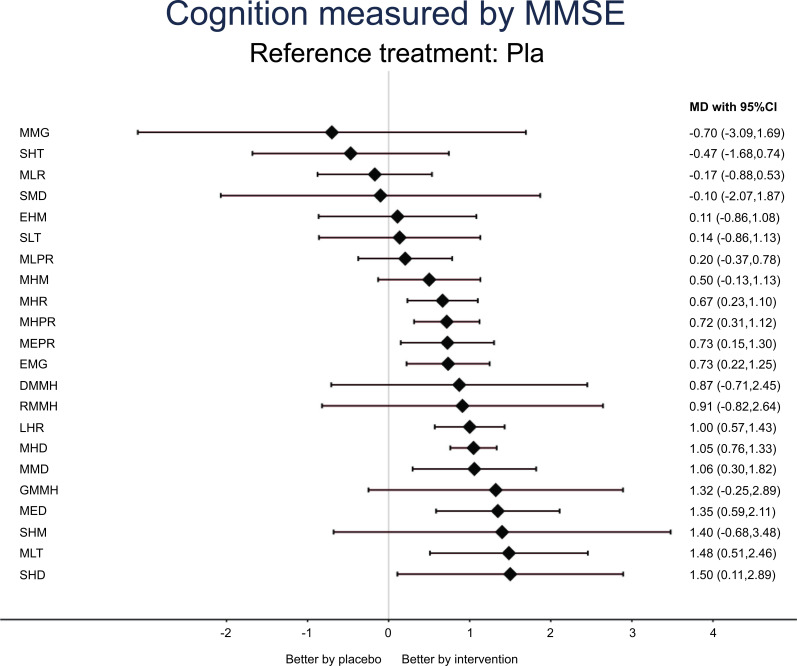

3.2. Primary Outcome: Changes in Cognition (Measured by the MMSE)

The NMA revealed the medium-term low-dose melatonin (MLT), short-term high-dose donepezil (SHD), medium-term extremely high-dose donepezil (MED), medium-term medium-dose donepezil (MMD), medium-term high-dose donepezil (MHD), long-term high-dose rivastigmine (LHR), extremely long-term medium-dose galantamine (EMG), medium-term extremely high-dose rivastigmine patches (MEPR), medium-term high-dose rivastigmine patches (MHPR), and medium-term high-dose rivastigmine (MHR) to be significantly associated with higher post-treatment MMSE than placebos in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia (Table 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3). According to the SUCRA, MLT was associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE, followed by MED and SHD (Supplement Table S6A (5.1MB, pdf) ).

Table 1.

League table of the improvement in cognition (measured by MMSE).

| MLT | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | *1.48 (0.54,2.43) | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.14 (-1.10,1.37) | MED | - | - | - | 0.30 (-0.32,0.92) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| -0.02 (-1.72,1.68) | -0.15 (-1.74,1.43) | SHD | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | *1.50 (0.15,2.85) | - | - | - |

| 0.16 (-1.68,2.01) | 0.03 (-1.71,1.76) | 0.18 (-1.92,2.28) | GMMH | - | - | - | - | 0.41 (-1.07,1.89) | 0.45 (-0.85,1.75) | - | - | - | - | 0.82 (-0.58,2.22) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 0.08 (-2.21,2.38) | -0.05 (-2.27,2.16) | 0.10 (-2.40,2.60) | -0.08 (-2.68,2.53) | SHM | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.40 (-0.65,3.45) | - | - | - |

| 0.44 (-0.58,1.45) | 0.30 (-0.41,1.01) | 0.45 (-0.97,1.87) | 0.27 (-1.31,1.86) | 0.35 (-1.74,2.45) | MHD | 0.15 (-0.65,0.95) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.37 (-1.94,1.20) | - | - | - | - | *1.08 (0.83,1.34) | - | - | - |

| 0.43 (-0.81,1.66) | 0.29 (-0.75,1.33) | 0.44 (-1.15,2.03) | 0.26 (-1.48,2.00) | 0.34 (-1.87,2.56) | -0.01 (-0.77,0.75) | MMD | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | *1.21 (0.42,2.00) | - | - | - |

| 0.48 (-0.58,1.55) | 0.35 (-0.53,1.22) | 0.50 (-0.96,1.96) | 0.32 (-1.31,1.95) | 0.40 (-1.72,2.52) | 0.05 (-0.47,0.56) | 0.06 (-0.82,0.93) | LHR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | *1.00 (0.72,1.28) | - | - | - |

| 0.57 (-1.41,2.56) | 0.44 (-1.45,2.32) | 0.59 (-1.63,2.81) | 0.41 (-1.11,1.93) | 0.49 (-2.22,3.19) | 0.14 (-1.61,1.89) | 0.15 (-1.74,2.04) | 0.09 (-1.70,1.87) | RMMH | 0.04 (-1.45,1.53) | - | - | - | - | 0.41 (-1.17,1.99) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 0.61 (-1.24,2.47) | 0.48 (-1.27,2.22) | 0.63 (-1.48,2.73) | 0.45 (-0.89,1.79) | 0.53 (-2.08,3.14) | 0.18 (-1.42,1.77) | 0.19 (-1.56,1.94) | 0.13 (-1.51,1.77) | 0.04 (-1.49,1.57) | DMMH | - | - | - | - | 0.37 (-1.78,1.04) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 0.75 (-0.35,1.85) | 0.61 (-0.30,1.53) | 0.77 (-0.72,2.25) | 0.59 (-1.06,2.24) | 0.67 (-1.47,2.81) | 0.31 (-0.27,0.90) | 0.32 (-0.59,1.24) | 0.27 (-0.40,0.94) | 0.18 (-1.63,1.98) | 0.14 (-1.52,1.80) | EMG | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | *0.73 (0.34,1.13) | - | - | - |

| 0.77 (-0.29,1.82) | 0.63 (-0.23,1.49) | 0.78 (-0.67,2.23) | 0.60 (-1.02,2.22) | 0.68 (-1.43,2.80) | 0.33 (-0.17,0.83) | 0.34 (-0.52,1.20) | 0.28 (-0.31,0.87) | 0.19 (-1.58,1.97) | 0.15 (-1.48,1.78) | 0.02 (-0.64,0.67) | MHPR | 0.20 (-0.34,0.74) | 0.21 (-0.18,0.59) | - | - | - | 0.30 (-0.23,0.83) | - | 0.69 (-0.09,1.48) | - | - | - |

| 0.76 (-0.37,1.89) | 0.62 (-0.33,1.58) | 0.77 (-0.73,2.28) | 0.60 (-1.07,2.27) | 0.67 (-1.48,2.83) | 0.32 (-0.32,0.97) | 0.33 (-0.62,1.29) | 0.27 (-0.44,0.99) | 0.19 (-1.64,2.01) | 0.15 (-1.53,1.83) | 0.01 (-0.76,0.78) | -0.01 (-0.57,0.56) | MEPR | 0.10 (-0.43,0.63) | - | - | - | - | - | *0.90 (0.35,1.45) | - | - | - |

| 0.82 (-0.25,1.88) | 0.68 (-0.20,1.56) | 0.83 (-0.62,2.29) | 0.66 (-0.97,2.28) | 0.73 (-1.39,2.86) | 0.38 (-0.14,0.90) | 0.39 (-0.49,1.27) | 0.33 (-0.28,0.95) | 0.25 (-1.54,2.03) | 0.21 (-1.43,1.84) | 0.07 (-0.60,0.74) | 0.05 (-0.36,0.46) | 0.06 (-0.51,0.63) | MHR | - | - | - | - | - | *0.83 (0.39,1.26) | - | *0.94 (0.24,1.64) | - |

| 0.98 (-0.18,2.14) | 0.85 (-0.13,1.82) | 1.00 (-0.53,2.53) | 0.82 (-0.62,2.26) | 0.90 (-1.27,3.07) | 0.55 (-0.13,1.22) | 0.56 (-0.43,1.54) | 0.50 (-0.26,1.26) | 0.41 (-1.20,2.02) | 0.37 (-1.08,1.82) | 0.23 (-0.58,1.04) | 0.22 (-0.53,0.96) | 0.22 (-0.63,1.08) | 0.16 (-0.60,0.93) | MHM | - | - | - | - | 0.33 (-0.31,0.97) | - | - | - |

| 1.35 (-0.04,2.74) | 1.21 (-0.04,2.46) | 1.36 (-0.35,3.08) | 1.19 (-0.67,3.04) | 1.26 (-1.04,3.57) | 0.91 (-0.13,1.95) | 0.92 (-0.33,2.18) | 0.86 (-0.22,1.95) | 0.78 (-1.22,2.77) | 0.74 (-1.13,2.60) | 0.60 (-0.52,1.72) | 0.58 (-0.49,1.65) | 0.59 (-0.56,1.74) | 0.53 (-0.55,1.61) | 0.37 (-0.81,1.54) | SLT | - | - | - | 0.13 (-0.83,1.08) | - | - | 0.53 (-0.67,1.73) |

| 1.37 (-0.00,2.75) | *1.24 (0.00,2.47) | 1.39 (-0.31,3.09) | 1.21 (-0.64,3.06) | 1.29 (-1.00,3.58) | 0.94 (-0.08,1.95) | 0.95 (-0.29,2.18) | 0.89 (-0.17,1.95) | 0.80 (-1.19,2.79) | 0.76 (-1.09,2.62) | 0.62 (-0.48,1.72) | 0.61 (-0.45,1.66) | 0.62 (-0.51,1.74) | 0.56 (-0.51,1.62) | 0.39 (-0.77,1.55) | 0.03 (-1.37,1.42) | EHM | - | - | 0.11 (-0.81,1.03) | - | - | - |

| *1.28 (0.15,2.41) | *1.14 (0.18,2.10) | 1.30 (-0.21,2.80) | 1.12 (-0.56,2.79) | 1.20 (-0.96,3.35) | *0.84 (0.19,1.49) | 0.85 (-0.10,1.81) | *0.80 (0.07,1.52) | 0.71 (-1.12,2.53) | 0.67 (-1.01,2.35) | 0.53 (-0.24,1.30) | 0.51 (-0.07,1.09) | 0.52 (-0.24,1.28) | 0.46 (-0.20,1.12) | 0.30 (-0.56,1.15) | -0.07 (-1.22,1.08) | -0.09 (-1.23,1.04) | MLPR | - | 0.00 (-0.52,0.52) | - | - | - |

| 1.58 (-0.61,3.78) | 1.45 (-0.67,3.56) | 1.60 (-0.81,4.01) | 1.42 (-1.10,3.94) | 1.50 (-1.36,4.36) | 1.15 (-0.84,3.14) | 1.16 (-0.95,3.27) | 1.10 (-0.92,3.12) | 1.01 (-1.61,3.63) | 0.97 (-1.55,3.50) | 0.83 (-1.20,2.87) | 0.82 (-1.19,2.83) | 0.83 (-1.23,2.88) | 0.77 (-1.25,2.78) | 0.60 (-1.47,2.67) | 0.24 (-1.97,2.44) | 0.21 (-1.99,2.41) | 0.30 (-1.75,2.36) | SMD | -0.10 (-2.04,1.84) | - | - | - |

| *1.48 (0.51,2.46) | *1.35 (0.59,2.11) | *1.50 (0.11,2.89) | 1.32 (-0.25,2.89) | 1.40 (-0.68,3.48) | *1.05 (0.76,1.33) | *1.06 (0.30,1.82) | *1.00 (0.57,1.43) | 0.91 (-0.82,2.64) | 0.87 (-0.71,2.45) | *0.73 (0.22,1.25) | *0.72 (0.31,1.12) | *0.73 (0.15,1.30) | *0.67 (0.23,1.10) | 0.50 (-0.13,1.13) | 0.14 (-0.86,1.13) | 0.11 (-0.86,1.08) | 0.20 (-0.37,0.78) | -0.10 (-2.07,1.87) | Pla | 0.70 (-1.67,3.07) | 0.06 (-0.66,0.78) | 0.54 (-0.65,1.73) |

| 2.18 (-0.40,4.77) | 2.05 (-0.46,4.56) | 2.20 (-0.57,4.97) | 2.02 (-0.84,4.88) | 2.10 (-1.07,5.27) | 1.75 (-0.66,4.16) | 1.76 (-0.75,4.27) | 1.70 (-0.73,4.13) | 1.61 (-1.34,4.57) | 1.57 (-1.30,4.44) | 1.43 (-1.01,3.88) | 1.42 (-1.01,3.84) | 1.43 (-1.04,3.89) | 1.37 (-1.07,3.80) | 1.20 (-1.27,3.68) | 0.84 (-1.76,3.43) | 0.81 (-1.77,3.39) | 0.90 (-1.56,3.37) | 0.60 (-2.50,3.70) | 0.70 (-1.69,3.09) | MMG | - | - |

| *1.65 (0.45,2.86) | *1.52 (0.48,2.56) | *1.67 (0.11,3.23) | 1.49 (-0.23,3.21) | 1.57 (-0.62,3.77) | *1.22 (0.46,1.98) | *1.23 (0.19,2.27) | *1.17 (0.34,2.00) | 1.08 (-0.79,2.95) | 1.04 (-0.69,2.77) | *0.90 (0.03,1.78) | *0.89 (0.14,1.64) | *0.90 (0.04,1.75) | *0.84 (0.14,1.54) | 0.67 (-0.27,1.62) | 0.31 (-0.91,1.53) | 0.28 (-0.92,1.48) | 0.38 (-0.51,1.26) | 0.07 (-2.02,2.16) | 0.17 (-0.53,0.88) | -0.53 (-3.02,1.97) | MLR | - |

| *1.95 (0.40,3.51) | *1.81 (0.38,3.25) | *1.97 (0.12,3.81) | 1.79 (-0.19,3.77) | 1.87 (-0.54,4.27) | *1.51 (0.27,2.76) | *1.53 (0.10,2.96) | *1.47 (0.18,2.75) | 1.38 (-0.73,3.49) | 1.34 (-0.65,3.33) | 1.20 (-0.11,2.52) | 1.19 (-0.09,2.46) | 1.19 (-0.15,2.53) | 1.13 (-0.15,2.42) | 0.97 (-0.40,2.33) | 0.60 (-0.61,1.82) | 0.58 (-0.97,2.13) | 0.67 (-0.67,2.01) | 0.37 (-1.94,2.68) | 0.47 (-0.74,1.68) | -0.23 (-2.91,2.45) | 0.30 (-1.10,1.70) | SHT |

Pairwise (upper-right portion) and network (lower-left portion) meta-analysis results are presented as estimated effect sizes for the outcome of improvement of cognition in patients with tinnitus. Interventions are reported in order of mean ranking of cognition improvement, and outcomes are expressed as mean difference (MD) (95% confidence intervals). For the pairwise meta-analyses, MD of more than 0 indicates that the treatment specified in the row had more improvement than that specified in the column. For the network meta-analysis (NMA), MD of more than 0 indicates that the treatment specified in the column had more improvement than that specified in the row. Bold results marked with * indicate statistical significance.

Fig. (3).

Forest plot of changes in cognitive function. Figure 3) indicates that, when the effect size is more than zero, the specified treatment is associated with higher improvements in cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia than placebos in the measurement of MMSE.

3.2.1. Transitivity Assumption Test

Because there was only one RCT in the “long-term” duration group in the transitivity assumption test, we did not include the “long-term” duration group in this transitivity assumption test. In brief, there was a significant difference found between the “short-term,” “medium-term,” and “extremely long-term” durations of placebo therapy (p < 0.001, Supplement Fig. S3 (5.1MB, pdf) ). Furthermore, this significance occurred in the comparison of the “short-term” vs. “extremely long-term” groups and “medium-term” vs. “extremely long-term” groups. Furthermore, we detected a significant decline in cognition (measured with MMSE) in the extremely long-term placebo therapy group.

3.2.2. Subgroup Analysis

Because there were insufficient RCTs in the “short-term” and “extremely long-term” subgroups (k = 5 and 2, respectively), we only arranged further subgroup analyses focusing on RCTs with “medium-term” treatment durations. In brief, the subgroup NMA revealed MLT, MED, MMD, MHD, MEPR, MHPR, and MHR to be associated with a significantly higher post-treatment MMSE than placebos in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia (Supplement Table S7A (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Fig. S1A (5.1MB, pdf) , and Supplement Fig. S2A (5.1MB, pdf) ). According to the SUCRA, MLT was associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE, followed by MED (Supplement Table 6B (5.1MB, pdf) ). Further, we arranged subgroup analyses focusing on RCTs that excluded prescriptive medications with effects on cognition. In brief, the subgroup NMA revealed SHD, MLT, MMD, MHD, LHR, MEPR, MHPR, and MHR to be associated with a significantly higher post-treatment MMSE than placebos in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia (Supplement Table S7B (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Fig. S1B (5.1MB, pdf) , and Supplement Fig. S2B (5.1MB, pdf) ). According to the SUCRA, SHD was associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE, followed by medium-term high-dose memantine plus low-dose galantamine (GMMH) and MLT (Supplement Table S6C (5.1MB, pdf) ).

3.3. Secondary Outcome: Changes in Quality of Life

The NMA revealed only MLT, medium-term high-dose memantine plus high-dose donepezil (DMMH), and MHD to be significantly associated with better post-treatment quality of life than placebos in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia (Supplement Table S7C (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Fig. S1C (5.1MB, pdf) , and Supplement Fig. 2C (5.1MB, pdf) ). According to the SUCRA, MLT was associated with the highest post-treatment quality of life (Supplement Table S6D (5.1MB, pdf) ).

3.4. Secondary Outcome: Changes in Behavioral Disturbances

The NMA revealed only short-term high-dose memantine (SHM) to be associated with significantly higher improvements in behavioral disturbances than placebos in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia (Supplement Table S7D (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Fig. S1D (5.1MB, pdf) , and Supplement Fig. S2D (5.1MB, pdf) ). According to the SUCRA, the SHM was associated with the highest improvement in behavioral disturbances (Supplement Table S6E (5.1MB, pdf) ).

3.5. Acceptability Reflected by Dropout Rates

In the NMA, only short-term high-dose rivastigmine (SHR), short-term high-dose galantamine (SHG), MED, medium-term high-dose galantamine (MHG), MHR, MEPR, MHPR, medium-term low-dose rivastigmine patches (MLPR), short-term medium-dose galantamine (SMG), and medium-term medium-dose galantamine (MMG) were associated with significantly higher dropout rates than placebos (Supplement Table S5C (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Table S7E (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Fig. S1E (5.1MB, pdf) , and Supplement Fig. S2E (5.1MB, pdf) ). According to the SUCRA, short-term low-dose melatonin (SLT) was associated with the lowest drop-out rate (Supplement Table S6F (5.1MB, pdf) ).

3.6. Acceptability Reflected by the Rate of any Adverse Events Reported

In the NMA, the most investigated treatments, including SHR, SHG, MED, MEPR, MHR, MHG, DMMH, SMG, MHD, MHPR, MLPR, MMG, and EMG were associated with significantly higher rates of any adverse events reported than placebos (Supplement Table S5C (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Table S7F (5.1MB, pdf) , Supplement Fig. S2F (5.1MB, pdf) , and Supplement Fig. S2F (5.1MB, pdf) ). According to the SUCRA, medium-term low-dose rivastigmine (MLR) was associated with the lowest rate of any adverse events reported (Supplement Table S6G (5.1MB, pdf) ).

3.7. Risk of Bias, Publication Bias, Inconsistency Assessment, and GRADE Ratings

We found 74.3% (260/350 items), 23.4% (82/350 items), and 2.3% (8/350 items) of the included studies to have, overall, a low, unclear, and high risk of bias, respectively. Unclear reporting of the allocation procedures and blinding of the participants or research personnel were the most often encountered reasons for the high risk of bias (Fig. S4A-S4B). Funnel plots of the publication bias (Fig. S5A-S5J) revealed general symmetry, and the results of Egger’s test indicated no significant publication bias among the articles included in the NMA. In general, the NMA did not demonstrate inconsistencies in terms of either local inconsistencies as assessed using the loop-specific approach and node-splitting method or global inconsistencies as determined using the design-by-treatment method (Table S8-S10). The results of the GRADE evaluation are listed in the appendix. In brief, the overall quality of evidence of the NMA, direct evidence, and indirect evidence was low to medium (Supplement Table S11 (5.1MB, pdf) ).

4. DISCUSSION

The current work is the first study using the NMA statistics technique to provide a view of the potential benefits of melatonin for Alzheimer’s dementia compared to the other FDA-approved dementia-managing medications. In the current NMA, we found medium-term low-dose melatonin (MLT) to be associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE among all of the investigated medications in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia. This finding did not change after focusing on RCTs with medium-term treatment duration. Furthermore, the significantly beneficial effects on cognition of MLT were still found when focusing on RCTs that excluded concomitant medications. MLT was also associated with the highest post-treatment quality of life in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia. All of the investigated exogenous melatonin supplements were associated with similar acceptability with respect to the drop-out rate or rate of any adverse events reported, as was the placebo.

The most important finding of the current NMA was that medium-term low-dose melatonin was associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE in the participants with Alzheimer’s dementia. This finding differed from those of previous traditional meta-analyses [19-22]. By pooling the effect sizes of all of the different dosages and treatment durations of exogenous melatonin into one group, prior traditional meta-analyses revealed insignificant benefits of exogenous melatonin on cognition in patients with dementia. As addressed in the previous review article, low- to medium-dose exogenous melatonin affected the phase of sleep-wake rhythms, and high-dose exogenous melatonin showed hypnotic effects on older participants [174]. Similar dose-dependent effects of exogenous melatonin on cognition could also be found in the previous RCTs. Specifically, significant beneficial effects on MMSE were found in patients with dementia receiving medium-dose melatonin supplementation [15-17] but not those receiving high-dose melatonin supplementation [18, 175]. Furthermore, according to the previous RCT [3], low-dose melatonin in medium- to long-term but not short-term use could ameliorate cognitive decline along with the aging process [3]. Therefore, based on the current NMA and previous RCTs [3, 15-18, 175], we hypothesize that the potential beneficial effects of exogenous melatonin on cognition might be restricted to a specific dosage for medium-term use, which might have a therapeutic window of low-dose (less than or equal to 3 mg/day) and medium-term use (at least 6 months but less than 1 year), but not a medium- or high-dose and short-term use.

The rationale of exogenous melatonin supplementation to improve cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia could be supported by physiologic and pharmacologic evidence. Previous reports [176, 177] demonstrate that the neuron numbers of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which mainly modulates the effect of endogenous melatonin, decrease with aging and dementia. In addition, in age-matched controlled trials, serum melatonin levels were significantly lower in patients with dementia, especially Alzheimer’s dementia, than those in normal controls [13, 14]. In addition, patients with Alzheimer’s dementia have been found to be associated with not only the irregularity of endogenous melatonin in patients with dementia [12], but also with circadian rhythm disorders and sleep-wake rhythm disturbances [178, 179]. Insomnia at night and daytime sleepiness were prevalent and significantly correlated with the MMSE (Pearson’s r = 0.62, p < 0.05) in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia [180]. Furthermore, decreased sleep quality could impose adverse impacts on mental function [15] and worsen the progression of Alzheimer’s dementia [181-183] by increasing beta-amyloid deposition [184, 185]. Through the evidence from previous traditional meta-analyses, exogenous melatonin supplementation could improve sleep efficiency [22] and increase total sleep time at night but not during the day [21]. Therefore, exogenous melatonin supplementation, which could restore circadian rhythm [186] and improve sleep quality [22, 27], is a potential choice to alleviate the adverse impact of circadian rhythm disturbance and poor sleep quality on cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia.

In addition to circadian rhythm restoration and sleep quality improvement, there are three potential mechanisms by which melatonin might be able to alleviate Alzheimer’s dementia severity. The first mechanism is the anti-oxidative effect of melatonin supplementation [187]. In a previous research, Alzheimer's dementia was frequently associated with increased oxidative stress, and regimens with antioxidative stress effects might exert potential beneficial effects on cognitive function [188]. The second mechanism is its antagonism effect on beta-amyloid proteins [17]. Melatonin in vitro not only inhibits beta-amyloid protein generation, but also arrests the formation of amyloid fibrils by structure-dependent interactions with beta-amyloid proteins [189]. The third mechanism is its inhibitory effect on the hyperphosphorylation of Alzheimer-like tau protein, which might be associated with the progression of Alzheimer’s dementia [190].

4.1. Limitations

There are several limitations to be addressed in the current NMA. First, some analyses in this study were limited by underpowered statistics, including heterogeneity in the participants’ characteristics (for example, comorbid diseases, different concomitant medications, a wide variety of ages, lack of uniform diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s dementia, a wide variety of rating scales of secondary outcomes, and trial durations) and the small number of trials for some treatment arms. Second, because of the weak network structure (i.e., the limited number of the direct connections between active interventions), especially that of the secondary outcomes, the results of the current NMA should be interpreted with caution. Third, although we tried to include other kinds of melatonergic regimens (ramelteon and agomelatine) by adding these keywords to our search strategy, we found only RCTs with exogenous melatonin supplementation. Future RCTs focusing on different melatonergic regimens in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia are warranted to assess their efficacy. Fourth, as addressed in the discussion, as the treatment duration increased, the different effects on cognition of dementia-managing medications and placebos were more significant [3]. Nevertheless, the relatively overall short treatment duration among the recruited RCTs (mean duration = 34.8 weeks, range 4 to 208 weeks) limited the application of the results of the current NMA. Fifth, although we tried to arrange a subgroup analysis based on RCTs excluding concomitant prescriptive medications, the potential bias by concomitant prescriptive medications could not be completely eliminated. Finally, although our study was strengthened by comparing different treatments with NMA, the generalization of our results was still highly limited depending on the studies included and the possible comparisons within them. Future studies are warranted to assess the efficacy of melatonergic agents focusing on the optimal dosage and treatment duration for the alleviation of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s dementia in different medical settings. Clinicians should consider specific strategies in specific clinical conditions.

CONCLUSION

The current NMA has provided an overview of the potential effect of exogenous melatonin supplementation, especially medium-term low-dose melatonin, on the amelioration of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Specifically, the current NMA found medium-term low-dose melatonin to be associated with the highest post-treatment MMSE and quality of life in participants with Alzheimer’s dementia. However, because of the small numbers of included studies, the current NMA provided a potential view to encourage future large-scale and long-term treatment and follow-up duration RCTs to focus on the efficacy of different dosages and treatment durations of exogenous melatonin supplementation on cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All the figures/tables/illustrations in this study were original and the authors had the copyright of all the figures/tables/illustrations.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- CI

Confidence interval

- DMMH

Medium-term high dose memantine plus high dose donepezil

- EHM

Extreme-long-term high dose memantine

- EMG

Extreme-long-term medium dose galantamine

- ES

Effect size

- GMMH

Medium-term high dose memantine plus low dose galantamine

- LHR

Long-term high dose rivastigmine

- LLT

Long-term low dose melatonin

- MA

Meta-analysis

- MD

Mean difference

- MED

Medium-term extreme high dose donepezil

- MEM

Medium-term extreme high dose memantine

- MEPR

Medium-term extreme high dose rivastigmine patch

- MHD

Medium-term high dose donepezil

- MHG

Medium-term high dose galantamine

- MHM

Medium-term high dose memantine

- MHPR

Medium-term high dose rivastigmine patch

- MHR

Medium-term high dose rivastigmine

- MLPR

Medium-term low dose rivastigmine patch

- MLR

Medium-term low dose rivastigmine

- MLT

Medium-term low dose melatonin

- MMD

Medium-term donepezil medium dose

- MMG

Medium-term medium dose galantamine

- MMSE

Mini-mental status examination

- NMA

Network meta-analysis

- OR

Odds ratio

- Pla

Placebo

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RMMH

Medium-term high dose memantine plus medium dose rivastigmine

- SHD

Short-term high dose donepezil

- SHG

Short-term high dose galantamine

- SHM

Short-term high dose memantine

- SHR

Short-term high dose rivastigmine

- SHT

Short-term high dose melatonin

- SLG

Short-term low dose galantamine

- SLT

Short-term low dose melatonin

- SMD

Short-term medium dose donepezil

- SMG

Short-term medium dose galantamine

- SMT

Short-term medium dose melatonin

- StMD

Standardized mean difference

- SUCRA

Surface under the cumulative ranking curve

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Ping-Tao Tseng, Bing-Yan Zeng, and Yen-Wen Chen, who contributed equally as first authors, took the whole responsibility of literature search, data extraction, and manuscript drafting. Chun-Pai Yang, Kuan-Pin Su, Tien-Yu Chen, Yi-Cheng Wu, Yu-Kang Tu, Pao-Yen Lin, Andre F. Carvalho, Brendon Stubbs, Yutaka J. Matsuoka, Dian-Jeng Li, Chih-Sung Liang, Chih-Wei Hsu, Cheuk-Kwan Sun, Yu-Shian Cheng, and Pin-Yang Yeh contributed to study design, concept formation, and major revision of the manuscript. Yow-Ling Shiue, who contributed as the corresponding author, took the responsibility of the collection of all information from the other co-authors, major revision of the manuscript, and full access to the data.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines were followed for the study.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert L.E., Weuve J., Scherr P.A., Evans D.A. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.González-Salvador T., Lyketsos C.G., Baker A., Hovanec L., Roques C., Brandt J., Steele C. Quality of life in dementia patients in long-term care. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2000;15(2):181–189. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(200002)15:2<181::AID-GPS96>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riemersma-van der Lek R.F., Swaab D.F., Twisk J., Hol E.M., Hoogendijk W.J., Van Someren E.J. Effect of bright light and melatonin on cognitive and noncognitive function in elderly residents of group care facilities: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(22):2642–2655. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.22.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donaldson C., Tarrier N., Burns A. Determinants of carer stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 1998;13(4):248–256. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199804)13:4<248::AID-GPS770>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devanand D.P., Jacobs D.M., Tang M.X., Del Castillo-Castaneda C., Sano M., Marder K., Bell K., Bylsma F.W., Brandt J., Albert M., Stern Y. The course of psychopathologic features in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54(3):257–263. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830150083012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore A., Patterson C., Lee L., Vedel I., Bergman H., Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia Fourth Canadian consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia: Recommendations for family physicians. Can. Fam. Physician. 2014;60(5):433–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valdés-Tovar M., Estrada-Reyes R., Solís-Chagoyán H., Argueta J., Dorantes-Barrón A.M., Quero-Chávez D., Cruz-Garduño R., Cercós M.G., Trueta C., Oikawa-Sala J., Dubocovich M.L., Benítez-King G. Circadian modulation of neuroplasticity by melatonin: A target in the treatment of depression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018;175(16):3200–3208. doi: 10.1111/bph.14197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardinali D.P., Furio A.M., Brusco L.I. Clinical aspects of melatonin intervention in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2010;8(3):218–227. doi: 10.2174/157015910792246209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardinali D.P., Vigo D.E., Olivar N., Vidal M.F., Brusco L.I. Melatonin therapy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxidants. 2014;3(2):245–277. doi: 10.3390/antiox3020245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moe K.E., Vitiello M.V., Larsen L.H., Prinz P.N. Symposium: Cognitive processes and sleep disturbances: Sleep/wake patterns in Alzheimer’s disease: relationships with cognition and function. J. Sleep Res. 1995;4(1):15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker M.P., Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron. 2004;44(1):121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishima K., Tozawa T., Satoh K., Matsumoto Y., Hishikawa Y., Okawa M. Melatonin secretion rhythm disorders in patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type with disturbed sleep-waking. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;45(4):417–421. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohashi Y., Okamoto N., Uchida K., Iyo M., Mori N., Morita Y. Daily rhythm of serum melatonin levels and effect of light exposure in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;45(12):1646–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida K., Okamoto N., Ohara K., Morita Y. Daily rhythm of serum melatonin in patients with dementia of the degenerate type. Brain Res. 1996;717(1-2):154–159. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asayama K., Yamadera H., Ito T., Suzuki H., Kudo Y., Endo S. Double blind study of melatonin effects on the sleep-wake rhythm, cognitive and non-cognitive functions in Alzheimer type dementia. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 2003;70(4):334–341. doi: 10.1272/jnms.70.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wade A.G., Farmer M., Harari G., Fund N., Laudon M., Nir T., Frydman-Marom A., Zisapel N. Add-on prolonged-release melatonin for cognitive function and sleep in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A 6-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2014;9:947–961. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S65625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Q.W., Lio Y., Luo G.Q., Xiang W., Peng K.R. Effect of melatonin on mild Alzheimer’s disease in elderly male patients. Parct Geriatr. 2009;23(1):56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer C., Tractenberg R.E., Kaye J., Schafer K., Gamst A., Grundman M., Thomas R., Thal L.J., Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study A multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of melatonin for sleep disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. 2003;26(7):893–901. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCleery J., Cohen D.A., Sharpley A.L. Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;(3):CD009178. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009178.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCleery J., Cohen D.A., Sharpley A.L. Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016;11:CD009178. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009178.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y.Y., Zheng W., Ng C.H., Ungvari G.S., Wei W., Xiang Y.T. Meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of melatonin in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2017;32(1):50–57. doi: 10.1002/gps.4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J., Wang L.L., Dammer E.B., Li C.B., Xu G., Chen S.D., Wang G. Melatonin for sleep disorders and cognition in dementia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2015;30(5):439–447. doi: 10.1177/1533317514568005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCleery J., Sharpley A.L. Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;11:CD009178. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009178.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumsuzzman D.M., Choi J., Jin Y., Hong Y. Neurocognitive effects of melatonin treatment in healthy adults and individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021;127:459–473. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brzezinski A., Vangel M.G., Wurtman R.J., Norrie G., Zhdanova I., Ben-Shushan A., Ford I. Effects of exogenous melatonin on sleep: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2005;9(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buscemi N., Vandermeer B., Hooton N., Pandya R., Tjosvold L., Hartling L., Vohra S., Klassen T.P., Baker G. Efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for secondary sleep disorders and sleep disorders accompanying sleep restriction: Meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;332(7538):385–393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38731.532766.F6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sack R.L., Hughes R.J., Edgar D.M., Lewy A.J. Sleep-promoting effects of melatonin: At what dose, in whom, under what conditions, and by what mechanisms? Sleep. 1997;20(10):908–915. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.10.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang C.P., Tseng P.T., Pei-Chen C.J., Su H., Satyanarayanan S.K., Su K.P. Melatonergic agents in the prevention of delirium: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2020;50:101235. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins J.P., Welton N.J. Network meta-analysis: A norm for comparative effectiveness? Lancet. 2015;386(9994):628–630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61478-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naci H., Salcher-Konrad M., Kesselheim A.S., Wieseler B., Rochaix L., Redberg R.F., Salanti G., Jackson E., Garner S., Stroup T.S., Cipriani A. Generating comparative evidence on new drugs and devices before approval. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):986–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J.M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M.M., Li T., Loder E.W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., McGuinness L.A., Stewart L.A., Thomas J., Tricco A.C., Welch V.A., Whiting P., Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71):n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shea B.J., Reeves B.C., Wells G., Thuku M., Hamel C., Moran J., Moher D., Tugwell P., Welch V., Kristjansson E., Henry D.A. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urrestarazu E., Iriarte J. Clinical management of sleep disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease: Current and emerging strategies. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2016;8:21–33. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S76706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W., Chen X.Y., Su S.W., Jia Q.Z., Ding T., Zhu Z.N., Zhang T. Exogenous melatonin for sleep disorders in neurodegenerative diseases: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Neurol. Sci. 2016;37(1):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10072-015-2357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe M., Nakamura Y., Yoshiyama Y., Kagimura T., Kawaguchi H., Matsuzawa H., Tachibana Y., Nishimura K., Kubota N., Kobayashi M., Saito T., Tamura K., Sato T., Takahashi M., Homma A., Japanese Society of Scaling Keys of Evaluation Techniques for CNS Disorders Heterogeneity (SKETCH) study group Analyses of natural courses of Japanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease using placebo data from placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials: Japanese study on the estimation of clinical course of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (N. Y.) 2019;5(1):398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui C.C., Sun Y., Wang X.Y., Zhang Y., Xing Y. The effect of anti-dementia drugs on Alzheimer disease-induced cognitive impairment: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(27):e16091. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glinz D., Gloy V.L., Monsch A.U., Kressig R.W., Patel C., McCord K.A., Ademi Z., Tomonaga Y., Schwenkglenks M., Bucher H.C., Raatz H. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors combined with memantine for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2019;149:w20093. doi: 10.4414/smw.2019.20093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li D.D., Zhang Y.H., Zhang W., Zhao P. Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:472. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thancharoen O., Limwattananon C., Waleekhachonloet O., Rattanachotphanit T., Limwattananon P., Limpawattana P. Ginkgo biloba Extract (EGb761), Cholinesterase inhibitors, and memantine for the treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A network meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(5):435–452. doi: 10.1007/s40266-019-00648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McShane R., Westby M.J., Roberts E., Minakaran N., Schneider L., Farrimond L.E., Maayan N., Ware J., Debarros J. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;3:CD003154. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dou K.X., Tan M.S., Tan C.C., Cao X.P., Hou X.H., Guo Q.H., Tan L., Mok V., Yu J.T. Comparative safety and effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for Alzheimer’s disease: A network meta-analysis of 41 randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018;10(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birks J.S., Harvey R.J. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018;6(6):CD001190. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001190.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koola M.M., Nikiforuk A., Pillai A., Parsaik A.K. Galantamine-memantine combination superior to donepezil-memantine combination in Alzheimer’s disease: Critical dissection with an emphasis on kynurenic acid and mismatch negativity. J. Geriatr. Care Res. 2018;5(2):57–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kishi T., Matsunaga S., Iwata N. The effects of memantine on behavioral disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017;13:1909–1928. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S142839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsieh M.T., Tseng P.T., Wu Y.C., Tu Y.K., Wu H.C., Hsu C.W., Lei W.T., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Liang C.S., Yeh T.C., Chen T.Y., Chu C.S., Li J.C., Yu C.L., Chen Y.W., Li D.J. Effects of different pharmacologic smoking cessation treatments on body weight changes and success rates in patients with nicotine dependence: A network meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2019;20(6):895–905. doi: 10.1111/obr.12835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tu Y.K., Faggion C.M., Jr A primer on network meta-analysis for dental research. ISRN Dent. 2012;2012:276520. doi: 10.5402/2012/276520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Y.C., Tseng P.T., Tu Y.K., Hsu C.Y., Liang C.S., Yeh T.C., Chen T.Y., Chu C.S., Matsuoka Y.J., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Wada S., Lin P.Y., Chen Y.W., Su K.P. Association of delirium response and safety of pharmacological interventions for the management and prevention of delirium: A network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):526–535. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng B.S., Lin S.Y., Tu Y.K., Wu Y.C., Stubbs B., Liang C.S., Yeh T.C., Chen T.Y., Carvalho A.F., Lin P.Y., Lei W.T., Hsu C.W., Chen Y.W., Tseng P.T., Chen C.H. Prevention of postdental procedure bacteremia: A network meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2019;98(11):1204–1210. doi: 10.1177/0022034519870466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang S.W., Tsai C.Y., Tseng C.S., Shih M.C., Yeh Y.C., Chien K.L., Pu Y.S., Tu Y.K. Comparative efficacy and safety of new surgical treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l5919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseng P.T., Yang C.P., Su K.P., Chen T.Y., Wu Y.C., Tu Y.K., Lin P.Y., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Matsuoka Y.J., Li D.J., Liang C.S., Hsu C.W., Chen Y.W., Shiue Y.L. The association between melatonin and episodic migraine: A pilot network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to compare the prophylactic effects with exogenous melatonin supplementation and pharmacotherapy. J. Pineal Res. 2020;69(2):e12663. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J.J., Chen Y.W., Zeng B.Y., Hung C.M., Zeng B.S., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Thompson T., Roerecke M., Su K.P., Tu Y.K., Wu Y.C., Smith L., Chen T.Y., Lin P.Y., Liang C.S., Hsu C.W., Hsu S.P., Kuo H.C., Wu M.K., Tseng P.T. Efficacy of pharmacologic treatment in tinnitus patients without specific or treatable origin: A network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eclini. Med. 2021;39:101080. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen J.J., Zeng B.S., Wu C.N., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Brunoni A.R., Su K.P., Tu Y.K., Wu Y.C., Chen T.Y., Lin P.Y., Liang C.S., Hsu C.W., Hsu S.P., Kuo H.C., Chen Y.W., Tseng P.T., Li C.T. Association of central noninvasive brain stimulation interventions with efficacy and safety in tinnitus management: A meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(9):801–809. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng Y.S., Tseng P.T., Wu M.K., Tu Y.K., Wu Y.C., Li D.J., Chen T.Y., Su K.P., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Lin P.Y., Matsuoka Y.J., Chen Y.W., Sun C.K., Shiue Y.L. Pharmacologic and hormonal treatments for menopausal sleep disturbances: A network meta-analysis of 43 randomized controlled trials and 32,271 menopausal women. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021;57:101469. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng Y.S., Tseng P.T., Wu Y.C., Tu Y.K., Wu C.K., Hsu C.W., Lei W.T., Li D.J., Chen T.Y., Stubbs B., Carvalho A.F., Liang C.S., Yeh T.C., Chu C.S., Chen Y.W., Lin P.Y., Wu M.K., Sun C.K. Therapeutic benefits of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for depressive symptoms after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2021;46(1):E196–E207. doi: 10.1503/jpn.190122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang H.Y., Chen T.Y., Li D.J., Lin P.Y., Su K.P., Chiang M.H., Carvalho A.F., Stubbs B., Tu Y.K., Wu Y.C., Roerecke M., Smith L., Tseng P.T., Hung K.C. Association of pharmacological prophylaxis with the risk of pediatric emergence delirium after sevoflurane anesthesia: An updated network meta-analysis. J. Clin. Anesth. 2021;75:110488. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atri A., Shaughnessy L.W., Locascio J.J., Growdon J.H. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2008;22(3):209–221. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wlodarczyk J.H., Brodaty H., Hawthorne G. The relationship between quality of life, Mini-Mental State Examination, and the instrumental activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2004;39(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perneczky R., Wagenpfeil S., Komossa K., Grimmer T., Diehl J., Kurz A. Mapping scores onto stages: Mini-mental state examination and clinical dementia rating. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):139–144. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192478.82189.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doody R.S., Massman P., Dunn J.K. A method for estimating progression rates in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2001;58(3):449–454. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henneges C., Reed C., Chen Y.F., Dell’Agnello G., Lebrec J. Describing the sequence of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease patients: Results from an observational study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(3):1065–1080. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohs R.C., Knopman D., Petersen R.C., Ferris S.H., Ernesto C., Grundman M., Sano M., Bieliauskas L., Geldmacher D., Clark C., Thal L.J. Development of cognitive instruments for use in clinical trials of antidementia drugs: Additions to the Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale that broaden its scope. The Alzheimer’s disease cooperative study. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1997;11(Suppl. 2):S13–S21. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Higgins J., Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.2. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puhan M.A., Schünemann H.J., Murad M.H., Li T., Brignardello-Petersen R., Singh J.A., Kessels A.G., Guyatt G.H., Group G.W., GRADE Working Group A GRADE working group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349(sep24 5):g5630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cipriani A., Furukawa T.A., Salanti G., Chaimani A., Atkinson L.Z., Ogawa Y., Leucht S., Ruhe H.G., Turner E.H., Higgins J.P.T., Egger M., Takeshima N., Hayasaka Y., Imai H., Shinohara K., Tajika A., Ioannidis J.P.A., Geddes J.R. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brockhaus A.C., Bender R., Skipka G. The Peto odds ratio viewed as a new effect measure. Stat. Med. 2014;33(28):4861–4874. doi: 10.1002/sim.6301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng J., Pullenayegum E., Marshall J.K., Iorio A., Thabane L. Impact of including or excluding both-armed zero-event studies on using standard meta-analysis methods for rare event outcome: A simulation study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010983. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tu Y.K. Use of generalized linear mixed models for network meta-analysis. Med. Decis. Making. 2014;34(7):911–918. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14545789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu G., Ades A.E. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat. Med. 2004;23(20):3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y., Wang W., Zhang A.B., Bai X., Zhang S. Epley and Semont maneuvers for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: A network meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(4):951–955. doi: 10.1002/lary.25688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kontopantelis E., Springate D.A., Reeves D. A re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: The dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salanti G., Ades A.E., Ioannidis J.P. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Higgins J.P., Del Giovane C., Chaimani A., Caldwell D.M., Salanti G. Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A324. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chaimani A., Higgins J.P., Mavridis D., Spyridonos P., Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mutz J., Vipulananthan V., Carter B., Hurlemann R., Fu C.H.Y., Young A.H. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of non-surgical brain stimulation for the acute treatment of major depressive episodes in adults: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;364:l1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Altman D.G., Bland J.M. Interaction revisited: The difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adair J.C., Knoefel J.E., Morgan N. Controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine for patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57(8):1515–1517. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.8.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Atri A., Frölich L., Ballard C., Tariot P.N., Molinuevo J.L., Boneva N., Windfeld K., Raket L.L., Cummings J.L. Effect of idalopirdine as adjunct to cholinesterase inhibitors on change in cognition in patients with Alzheimer disease: Three randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2018;319(2):130–142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bloniecki V., Aarsland D., Blennow K., Cummings J., Falahati F., Winblad B., Freund-Levi Y. Effects of risperidone and galantamine treatment on Alzheimer’s disease biomarker levels in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(2):387–393. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bullock R., Touchon J., Bergman H., Gambina G., He Y., Rapatz G., Nagel J., Lane R. Rivastigmine and donepezil treatment in moderate to moderately-severe Alzheimer’s disease over a 2-year period. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2005;21(8):1317–1327. doi: 10.1185/030079905X56565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Connelly P.J., Prentice N.P., Cousland G., Bonham J. A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of folic acid supplementation of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):155–160. doi: 10.1002/gps.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cummings J., Froelich L., Black S.E., Bakchine S., Bellelli G., Molinuevo J.L., Kressig R.W., Downs P., Caputo A., Strohmaier C. Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, 48-week study for efficacy and safety of a higher-dose rivastigmine patch (15 vs. 10 cm²) in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2012;33(5):341–353. doi: 10.1159/000340056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Devore E.E., Harrison S.L., Stone K.L., Holton K.F., Barrett-Connor E., Ancoli-Israel S., Yaffe K., Ensrud K., Cawthon P.M., Redline S., Orwoll E., Schernhammer E.S., Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Research Group Association of urinary melatonin levels and aging-related outcomes in older men. Sleep Med. 2016;23:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Doody R.S., Gavrilova S.I., Sano M., Thomas R.G., Aisen P.S., Bachurin S.O., Seely L., Hung D., dimebon investigators Effect of dimebon on cognition, activities of daily living, behaviour, and global function in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):207–215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dowling G.A., Burr R.L., Van Someren E.J., Hubbard E.M., Luxenberg J.S., Mastick J., Cooper B.A. Melatonin and bright-light treatment for rest-activity disruption in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008;56(2):239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fan Y., Yuan L., Ji M., Yang J., Gao D. The effect of melatonin on early postoperative cognitive decline in elderly patients undergoing hip arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2017;39:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Feldman H.H., Lane R., Study G., Study 304 Group Rivastigmine: A placebo controlled trial of twice daily and three times daily regimens in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2007;78(10):1056–1063. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Frölich L., Ashwood T., Nilsson J., Eckerwall G., Sirocco I., Sirocco Investigators Effects of AZD3480 on cognition in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A phase IIb dose-finding study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(2):363–374. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frölich L., Atri A., Ballard C., Tariot P.N., Molinuevo J.L., Boneva N., Geist M.A., Raket L.L., Cummings J.L. Open-label, multicenter, phase III extension study of idalopirdine as adjunctive to donepezil for the treatment of mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67(1):303–313. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fullerton T., Binneman B., David W., Delnomdedieu M., Kupiec J., Lockwood P., Mancuso J., Miceli J., Bell J. A phase 2 clinical trial of PF-05212377 (SAM-760) in subjects with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease with existing neuropsychiatric symptoms on a stable daily dose of donepezil. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018;10(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0368-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garzón C., Guerrero J.M., Aramburu O., Guzmán T. Effect of melatonin administration on sleep, behavioral disorders and hypnotic drug discontinuation in the elderly: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2009;21(1):38–42. doi: 10.1007/BF03324897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gault L.M., Lenz R.A., Ritchie C.W., Meier A., Othman A.A., Tang Q., Berry S., Pritchett Y., Robieson W.Z. ABT-126 monotherapy in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia: Randomized double-blind, placebo and active controlled adaptive trial and open-label extension. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2016;8(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gault L.M., Ritchie C.W., Robieson W.Z., Pritchett Y., Othman A.A., Lenz R.A. A phase 2 randomized, controlled trial of the α7 agonist ABT-126 in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimers Dement. (N. Y.) 2015;1(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gehrman P.R., Connor D.J., Martin J.L., Shochat T., Corey-Bloom J., Ancoli-Israel S. Melatonin fails to improve sleep or agitation in double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of institutionalized patients with Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2009;17(2):166–169. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318187de18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grossberg G.T., Alva G., Hendrix S., Ellison N., Kane M.C., Edwards J., Memantine E.R. Memantine ER maintains patient response in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: Post hoc analyses from a randomized, controlled, clinical trial of patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2018;32(3):173–178. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Haffmans P.M., Sival R.C., Lucius S.A., Cats Q., van Gelder L. Bright light therapy and melatonin in motor restless behaviour in dementia: A placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2001;16(1):106–110. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200101)16:1<106::AID-GPS288>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Haig G.M., Pritchett Y., Meier A., Othman A.A., Hall C., Gault L.M., Lenz R.A. A randomized study of H3 antagonist ABT-288 in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(3):959–971. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hamdieh M., Abbasinazari M., Badri T., Saberi-Isfeedvajani M., Arzani G. The impact of melatonin on the alleviation of cognitive impairment during electroconvulsive therapy: A double-blind controlled trial. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2017;24:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.npbr.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hong Y.J., Choi S.H., Jeong J.H., Park K.W., Na H.R. Effectiveness of anti-dementia drugs in extremely severe Alzheimer’s disease: A 12-week, multicenter, randomized, single-blind study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(3):1035–1044. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hong Y.J., Han H.J., Youn Y.C., Park K.W., Yang D.W., Kim S., Kim H.J., Kim J.E., Lee J.H., ODESA study (Optimal Dose Escalation Strategy to Successful Achievement of High Dose Donepezil 23 mg) Safety and tolerability of donepezil 23 mg with or without intermediate dose titration in patients with Alzheimer’s disease taking donepezil 10 mg: A multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel-design, three-arm, prospective trial. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2019;11(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Howard R., McShane R., Lindesay J., Ritchie C., Baldwin A., Barber R., Burns A., Dening T., Findlay D., Holmes C., Hughes A., Jacoby R., Jones R., Jones R., McKeith I., Macharouthu A., O’Brien J., Passmore P., Sheehan B., Juszczak E., Katona C., Hills R., Knapp M., Ballard C., Brown R., Banerjee S., Onions C., Griffin M., Adams J., Gray R., Johnson T., Bentham P., Phillips P. Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(10):893–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huisa B.N., Thomas R.G., Jin S., Oltersdorf T., Taylor C., Feldman H.H. Memantine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor use in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: Potential for confounding by indication. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67(2):707–713. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jaiswal S.J., McCarthy T.J., Wineinger N.E., Kang D.Y., Song J., Garcia S., van Niekerk C.J., Lu C.Y., Loeks M., Owens R.L. Melatonin and sleep in preventing hospitalized delirium: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Med. 2018;131(9):1110–1117.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Johannsen P., Salmon E., Hampel H., Xu Y., Richardson S., Qvitzau S., Schindler R., Group A.S., AWARE Study Group Assessing therapeutic efficacy in a progressive disease: A study of donepezil in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(4):311–325. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]