Abstract

Although few clinical trials examined the efficacy of bupropion to treat sexual dysfunction among female patients, a comprehensive and objective synthesis of the best available evidence is still lacking. To date, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews or meta-analyses specifically focusing on the role of bupropion in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of bupropion in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction, and we hypothesized that bupropion is efficient in treating female patients with sexual dysfunction. This review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A systematic search for published literature was performed using Ovid, Medline, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, and PubMed databases. In our study, we found that bupropion was almost three-fold more favorable in improving problems with sexual desire (pool estimate 2.845, 95% CI: 0.215 to 5.475, I2= 95.6%, p=0.034). A meta-regression was performed to explore heterogeneity and we found that only the dosage of bupropion was statistically significant in explaining the variance, i.e., the lower the dosage (150 mg vs. 300 mg), the better the improvement in the sexual desire of women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Based on the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis, there is a potential role of bupropion as an effective treatment for women with HSDD.

Keywords: Female sexual dysfunction, treatment, bupropion, systematic review, PRISMA, HSDD

1. INTRODUCTION

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is a prevalent medical problem worldwide [1]. The bio-psycho-social focus of interventions has been viewed as the best approach to this pivotal clinical entity [2, 3]. Managing women with the problem related to sexual desire, sometimes referred to as hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) as part of the FSD, is a great challenge for many clinicians [2, 3]. HSDD has been reported with rates of <10-30% [4]. Extensive population-based studies reported 36% to 39% of women with low sexual desire problems. From this proportion, 8% to 10% met the primary diagnostic criteria for HSDD [3]. In women, low sexual desire commonly increases with age, whereas related distress decreases, resulting in a reasonably steady prevalence of HSDD across the adult lifespan [3].

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [5], the term was revised to female sexual interest/arousal disorder (FSIAD), which was merged from two separate diagnoses, i.e., HSDD and female sexual arousal disorder (FSAD), in the fourth revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) [6].

FSIAD is defined as “the lack of, or significantly reduced, sexual interest/arousal, as demonstrated by at least 3 of the following: absent/reduced interest in sexual activity; absent/reduced sexual/erotic thoughts or fantasies; no/reduced initiation of sexual activity, and typically unreceptive to a partner’s attempts to initiate; absent/reduced sexual excitement/pleasure during sexual activity in almost all or all sexual encounters; absent/reduced sexual interest/ arousal in response to any internal or external sexual/erotic cues; absent/reduced genital or non-genital sensations during sexual activity in almost all or all sexual encounters.”

Sexual functioning includes sexual desire and sexual arousal. The sexual desire and sexual arousal dysfunction was reported with the administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) in 30% to 50% of those treated. Hence, it may lead to non-compliance with medication [7]. Drug holiday and/or substitution with antidepressants (AD) with fewer effects on sexual function, such as bupropion, nefazodone, and mirtazapine, are strategies to manage SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction that have been suggested to deal with sexual side-effects [8]. The management of poor sexual desire is frequently integrated into a multidisciplinary teamwork approach [1, 2]. It is pivotal to note that the role of her spouse/partner in helping to improve sexual desire is also as important as the psychopharmacological interventions, as the former has a close association between female and male sexual functioning [9].

The introduction of a recent pharmacological agent that has emerged in the contemporary literature has been the center of attention as a promising remedy in addressing HSDD. The search for novel psychological agents to treat HSDD has been pursued for decades. Among the pharmacological agents that have been used, flibanserin is the only food and drug administration (FDA)-approved treatment for HSDD [10]. Other medications indicated for HSDD, which are off-label, include hormonal agents, i.e., testosterone [11], and other pharmacological agents in the group of norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRI) like bupropion [12]. Bupropion has been used in the treatment of FSD, particularly for orgasmic dysfunction in non-depressed individuals [13].

Regarding bupropion, this agent is the only antidepressant without serotonergic activity and has a dual effect on dopamine and norepinephrine neurotransmitter systems [12, 14]. It was initially developed to improve the tolerability and safety of the existing antidepressants [12, 14]. Studies indicate that bupropion may reverse sexual dysfunction and has an exceptionally low incidence of drug-induced sexual dysfunction [15, 16]. Among the non-depressed female population, the evidence shows that bupropion may also have pro-sexual effects [13]. Premenopausal women treated with an escalating dose of bupropion were more likely to report a meaningful benefit than women receiving a placebo [17]. Bupropion in premenopausal women may be effective in improving sexual dysfunction symptoms, leading to overall improved sexual satisfaction. Treatment with bupropion may hold the potential to help women suffering from this condition [18].

Although some clinical trials have examined the efficacy of bupropion to treat sexual dysfunction among female patients, a comprehensive and objective synthesis of the best available evidence is still lacking. To date, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no published systematic review or meta-analysis specifically focusing on the role of bupropion in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of bupropion in the treatment of FSD, and we hypothesize that bupropion is efficient in treating female patients with sexual dysfunction.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). PRISMA is a recognized standard for reporting evidence in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It consists of a 27-item checklist to assist reviewers in reporting key characteristics of a systematic review [19].

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A systematic search for published literature was performed across 5 electronic databases (Ovid [Medline], Scopus, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, and PubMed). The electronic database search was conducted from inception till the second week of December 2020. The last search was performed on 16th December, 2020. Search terms were developed according to the population-exposure-comparator-outcome (PETO) framework of the research topic with relevant truncation and Boolean operators. The search focused on adult female subjects with bupropion intervention and the outcome of sexual dysfunction, including sexual desire dysfunction. The search terms used were as follows: “(female or wom$n)”, “adult”, “heterosexuality”, bupropion”, “wellbutrin”, “zyban”, bupropion hydrochloride”, “sexual dysfunction, physiological”, “sexual dysfunction, psychological”, “sexual*”, “dysfunction*”, “disorder*”, “disturban*”, “function*”, “activity”, “impair*”, “orgasm disorder”, “desire disorder”, “sexual adj3 (interest or desire or drive or aversion)”, “hypoactive sexual desire disorder”, “arousal disorder”, “female sexual arousal disorder”, “sexual stimulation”, “sexual excitement”, “lubrication”, “sexual satisfaction”, “sexual dissatisfaction”, “sexual pleasure”, “sexual enjoyment”, “sexual distress”, “sexual stress”, “pain disorder”, “vaginismus”, “dyspareunia”, “sexual difficult*”, “sexual problem*”, “vaginal pain”, “genital pain”, “sexual discomfort”, “penetration disorder”.

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (i) observational and interventional study designs, (ii) adult female subjects with sexual dysfunction, heterosexual, both pre- and postmenopausal, with and without depression, (iii) usage of any formulation of bupropion (bupropion, bupropion XR, bupropion SR) at any dose, (iv) comparisons with placebo or any other antidepressant treatment in women with depression, (v) reporting of the following outcome: improvement in sexual function including sexual desire, reported based on history-taking and valid instruments such as Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Clinical Global Impression of Sexual Function (CGI-SF), Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ), Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF-W), Sex FX Scale, and Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX). To ensure that most of the relevant studies were identified, a bibliographic search was also conducted from eligible studies and systematic reviews. The search was limited to the English language only.

2.2. Managing References

All search results were exported and merged into a reference management software, the Covidence systematic review software (available at www.covidence.org). All duplicates were automatically identified by the software and inspected individually before deletion. The selection of studies involved 5 reviewers (NAR, CLC, AB, NACR, and SD) independently, where the titles and abstracts were screened, and after those, full texts were analyzed for eligibility. Non-relevant studies were excluded. Any discrepancy was resolved by a 6th reviewer (HS).

2.3. Quality Assessment of Studies

The quality of included studies was assessed using a specifically modified version of the McMaster Critical Review Form for Quantitative Studies. A modified version more suitable for this review was developed (Appendix 1). Questions on randomization of groups were added for quality assessment of the included randomized controlled trials. Each question was rated “yes”, “no”, “not addressed”, or “not applicable”. A score of 1 point was only given to the “yes” answer. The total score varied by excluding questions rated “not applicable” according to different study designs. The methodologic quality of included studies was assessed by 4 reviewers independently (NA, CLC, and NACR), and any conflicts were resolved through discussion. The assessments were conducted by 3 reviewers (NA, CLC, and NACR) independently. Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus and referred to a 5th reviewer (HS) for clarification. This systematic review and meta-analysis were registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021226364 dated 15 January, 2021).

2.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers (NA and CLC) using customized Microsoft Excel Spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The information extracted includes demographic data, sample characteristics, and the results of all included studies.

2.5. Descriptive

Demographic data and characteristics of the included studies were tabulated and concluded narratively in the text.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The eligibility to run a meta-analysis was based on the availability of relevant data, including both dichotomous and continuous data, either directly extractable or calculable from the existing data, from more than one study. Regarding continuous data, we ran a meta-analysis if the relevant mean, standard deviation, and subjects’ number from both the intervention and control groups were available. For dichotomous data, we ran a meta-analysis if the total number of subjects in each intervention or control was reported or able to be calculated from the provided data, and the total number of subjects who responded to the intervention was available.

A meta-analysis was conducted using the Medcalc® software. A random-effects model was performed, considering the heterogeneity that was present across studies. The effect size for individual studies and their 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed with I2 statistic, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. We would seek other software options if the statistics calculation was beyond the limit of Medcalc® software. Meta-regression was conducted to explore the possible causes of heterogeneity across studies. The Comprehensive Meta-analysis software was used to run the meta-regression.

2.7. Synthesis of Results

The intervention category of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s (NHMR) evidence statement was used to determine the level of evidence of the present review. The NHMR instrument, which contains 5 main components, constitutes the evidence statement: (i) evidence base (based on quantity, quality, and the level of evidence); (ii) consistency of findings across included studies; (iii) clinical impact; (iv) generalizability; and (v) applicability. The “applicability” refers to applicability within the Australian healthcare context. It was deemed not relevant, thus not rated for the finding of this review. Each component was ranked with a grade from “A” to “D” to guide the weighing of the recommendation.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Selection

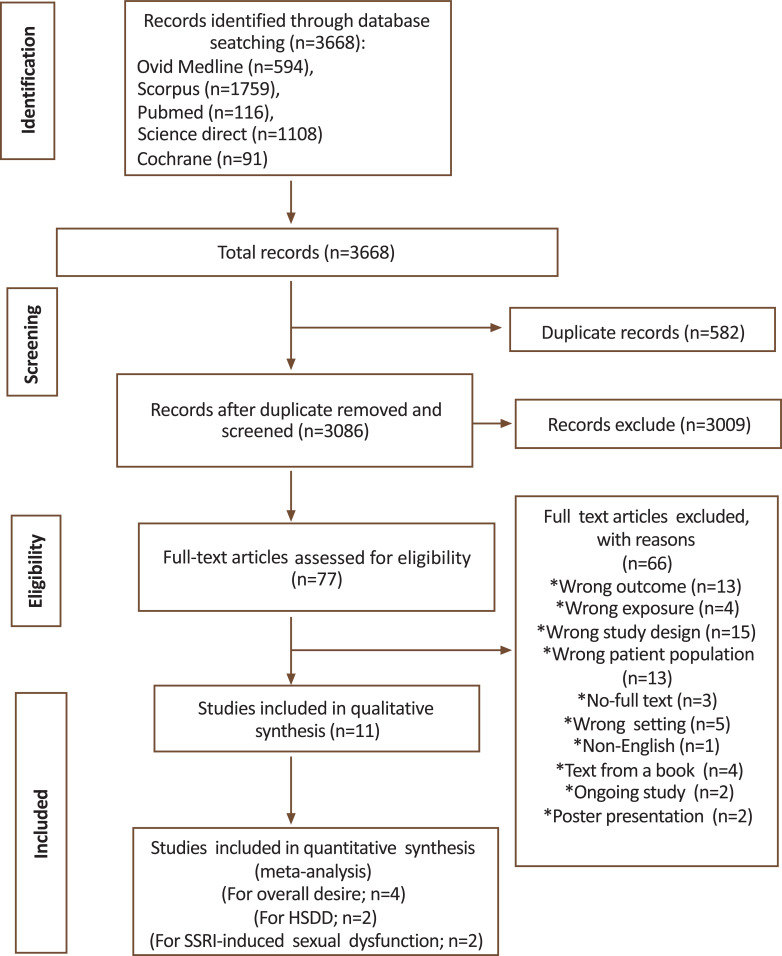

The initial search of electronic databases identified a total of 3668 studies. Of these, 577 were excluded because they were duplicates. A total of 3009 studies were excluded due to irrelevant titles and abstracts. The remaining 82 studies were assessed for full-text eligibility, and 71 studies were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1). Finally, 11 studies [17, 20-29] were included in the qualitative synthesis and only four studies [20, 21, 23, 25] were included in the meta-analysis.

Fig. (1).

The PRISMA flowchart.

3.2. Quality Assessment

The level of evidence for the included studies was classified according to the NHMRC matrix. Six studies [17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24] were rated as level II (randomized controlled trial), 4 studies [25, 26, 27, 28] were rated as level III-3 (comparative studies without concurrent controls) and one study [29] was rated as level IV (case series with either post-test or pre-test/post-test outcomes) (Table 1). According to the McMaster Critical Review tool, the majority of studies were rated to be at low risk of bias. Eight studies [20-27] rated > 90%, 2 studies [17, 29] rated 70-90%, and one study [28] rated 60-70%.

Table 1.

Quality of included studies.

| Study | NHMRC Evidence Hierarchy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad 2011 [20] | Level II | Randomised controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 16/16 (100%) |

| Safarinejad 2010 [21] | Level II | Randomised controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 16/16 (100%) |

| Segraves 2004 [17] | Level II | Randomised controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Na | Yes | Yes | Na | Na | Na | Yes | Na | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11/11 (100%) |

| Thase 2006 [22] | Level II | Randomised controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Na | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15/15 (100%) |

| Clayton 2004 [23] | Level II | Randomised controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15/16 (94%) |

| Kennedy 2006 [24] | Level II | Randomised controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15/16 (94%) |

| Hartmann 2012 [25] | Level III-3 | Interrupted time series without a parallel control group | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14/14 (100%) |

| DeFronzoDobkin 2006 [26] | Level III-3 | Interrupted time series without a parallel control group | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13/14 (93%) |

| Segraves 2001 [27] | Level III-3 | Interrupted time series without a parallel control group | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Na | Yes | 13/15 (87%) |

| Mathias 2006 [28] | Level III-3 | Interrupted time series without a parallel control group | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | NA | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 9/14 (64%) |

| Gitlin 2002 [29] | Level IV | Case series with either post-test or pre-test/post-test outcomes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 11/14 (79%) |

3.3. Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2. All the studies were published between 2001 and 2010 in five countries, including the United States of America, Germany, Canada, Brazil, and Iran.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Setting | N (total female) | N Bupropi on | N Compara tor | Mean age Bupropion | Mean age Comparat or | Intervention | Bupropion Dosage/day | Comparator | Comparat or Dosage/d ay | Duration | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayton 2004 [23] | US | Multicenter outpatient | 48 | 17 | 20 | 38.45 (5.73) | Bupropion SR | 300mg | Placebo | NA | 4 weeks | Yes | |

| DeFronzoDobkin 2006 [26] | US | Community & multicenter outpatient | 18 | NA | NR | NA | Bupropion SR | 150-300mg | NA | NA | 10 weeks | Yes | |

| Gitlin 2002 [29] | US | Community & multicenter outpatient | 15 | NA | 40.5 | NA | Bupropion SR | 100-300mg | NA | NA | 7 weeks | Yes | |

| Hartmann 2012 [25] | Germany | Outpatient from one center | 16 | NA | 40.3 | NA | Bupropion SR | 300mg | Placebo | NA | 16 weeks | No | |

| Kennedy 2006 [24] | Canada | Multicenter outpatient | 68 | 28 | 34 | 37.8 (10.5) | Bupropion SR | 150-300mg | Paroxetine | 20-40mg | 8 weeks | Yes | |

| Mathias 2006 [28] | Brazil | A private cancer center | 20 | NA | 50.6 (2.7) | NA | Bupropion | 75-150mg | NA | NA | 8 weeks | No | |

| Safarinejad 2011 [20] | Iran | Outpatient from one center | 218 | 109 | 109 | 33.7 (4.3) | 34.2 (4.1) | Bupropion SR | 150mg | Placebo | NA | 12 weeks | Yes |

| Safarinejad 2010 [21] | Iran | Outpatient from one center | 232 | 116 | 116 | 29.7 (5.2) | 29.2 (5.3) | Bupropion SR | 150mg | Placebo | NA | 12 weeks | No |

| Segraves 2001 [27] | USA | Multicenter outpatient | 55 | NA | 42 | NA | Bupropion SR | 300mg | NA | NA | 8 weeks | No | |

| Segraves 2004 [17] | USA | Multicenter outpatient | 66 | 31 | 35 | 36.1 | Bupropion SR | 150-400mg | Placebo | NA | 16 weeks | No | |

| Thase 2006 [22] | USA | Multicenter outpatient | 195 | 90 | 105 | 37.1 ± 12.3 | 37.4 ± 11.6 | Bupropion XL | 150-450mg | Venlafaxine XR | 75- 225mg | 12 weeks | Yes |

Legend: NA = Not available; SR = Slow Release.

Overall, 961 female participants were included. The mean age of participants across studies ranged from 29.2 to 50.6 years. The average size of a trial across all studies was 87 participants, with the largest study enrolling 232 patients and the smallest enrolling 15 patients. Meanwhile, the average duration of study across trials was 10 weeks, with the shortest and longest duration of treatment being 4 weeks and 16 weeks, respectively. The study design that was employed varied between the included studies, where six studies [17, 20, 21-24] instigated a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with two parallel arms while the remaining five studies [25-29] implemented a time-series with no control design. The sexual function reporting scales used also varied across studies, comprising the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ), Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Sex Effect Scale (Sex FX), Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX), Clinical Global Impression-Sexual Function (CGI-SF), and the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISFW) (Table 2a).

Table 2a.

Summary of results of bupropion on sexual desire outcome.

| Study |

NHMRC

Evidence Hierarchy |

Quality | Scale |

Improvement in Sexual

Desire/Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad 2011 [20] | Level II | 100% | FSFI, CGI-SF | ↑*** |

| Safarinejad 2010 [21] | Level II | 100% | BISFW, GEQ | ↑*** |

| Segraves 2004 [17] | Level II | 100% | CSFQ | ↔ |

| Thase 2006 [22] | Level II | 100% | CSFQ | ↑* |

| Clayton 2004 [23] | Level II | 94% | CSFQ | ↔ |

| Kennedy 2006 [24] | Level II | 94% | Sex FX | ↔ |

| Hartmann 2012 [25] | Level III-3 | 100% | FSFI | ↔ |

| DeFronzoDobkin 2006 [26] | Level III-3 | 93% | CSFQ | ↑** |

| Segraves 2001 [27] | Level III-3 | 87% | CGI-I, investigator rated scale | ↑*** |

| Mathias 2006 [28] | Level III-3 | 64% | ASEX | ↑* |

| Gitlin 2002 [29] | Level IV | 79% | ASEX | ↑** |

Legend: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; ↑ improve; ↔ no difference statistically. NHMRC = Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; CSFQ = Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, Sex FX = Sex Effect Scale, ASEX = Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale, CGI-SF = Clinical Global Impression-Sexual Function and BISFW = Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women].

3.4. Improvement in Overall Sexual Functioning

Seven studies [17, 20-22, 26-28] reported a statistically significant increase in overall sexual function. Of these, four were RCTs compared bupropion versus active comparator [22] or placebo [17, 20, 21]. The remaining three studies reported no significant differences either before or after treatment with bupropion [23, 25] or when compared to active treatment [24].

3.5. Females with Depression

3.5.1. Effects of Bupropion on Sexual Functions among Females with Depression

Two studies examined the effects on sexual function of anti-depressants during treatment of depression by comparing bupropion to another active comparator (Table 4). Thase et al. [22] conducted a head-to-head comparison between bupropion and venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), on 195 young, sexually active females with depression. This study reported that the effect of bupropion versus venlafaxine on sexual function was significantly improved (p< 0.05) when assessed using the CSFQ scale. On the contrary, Kennedy and colleagues [24] reported no statistically significant difference in antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction among 68 females with major depressive disorder (MDD) who were randomized to either bupropion SR or paroxetine for eight weeks.

Table 4.

Summary of studies reported risk of development of sexual dysfunction comparing exposure to bupropion and SSRI/SNRI among depressed subjects.

| Study | NHMRC Evidence Hierarchy | Quality | Comparator | Dosage | Scale | Improvement in Sexual Functioning as a Whole | Improvement in Sexual Desire/ Interest | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thase 2006 [22] | Level II | 100% | Venlafaxine XR |

75-225mg | CSFQ | ↑* | ↑* | Yes |

| Kennedy 2006 [24] | Level II | 94% | Paroxetine | 20-40mg | CSFQ | ↔ | ↔ | Yes |

* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; ↑ improve; ↔ no difference statistically. NHMRC = Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; CSFQ = Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, ASEX = Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale, CGI-SF = Clinical Global Impression-Sexual Function and BISFW = Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women.

3.5.2. Effectiveness of Bupropion on SSRI-induced Sexual Dysfunction in Females with Depression

Four studies explored the effect of bupropion in females with depression and those who experienced SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction [20, 23, 26, 29] (Table 3). Two trials [20, 23] randomized 266 females with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction to either bupropion or placebo. Safarinejad et al. [20] reported a higher total score in overall sexual function (better sexual function) in females receiving bupropion versus placebo (p=0.01) using the FSFI scale. In the meantime, Clayton et al. [23] reported no significant differences between the two groups of interventions based on the total CSFQ scores. All 4 studies reported significant improvement in sexual desire or sexual interest among females with depression who had SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.

Table 3.

Summary of studies reported on effectiveness of bupropion in subjects with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.

| Study | NHMRC evidence hierarchy | Quality | Scale | Improvement in sexual function as a whole | Improvement in Sexual Desire/ Interest | Depression | Severity of depression | Duration on SSRI before started bupropion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad 2011 [20] | Level II | 100% | FSFI, CGI-SF | ↑*** | ↑*** | Yes | Mild | ≥24 weeks |

| Clayton 2004 [23] | Level II | 94% | CSFQ | ↔ | ↑* | Yes | Remission | ≥12 weeks |

| DeFronzoDobkin 2006 [26] | Level III-3 | 93% | CSFQ | ↑*** | ↑** | Yes | Severe | ≥ 8 weeks |

| Gitlin 2002 [29] | Level IV | 79% | ASEX | Not reported as a whole | ↑** | Yes | Mild | 12-27 weeks |

Legend: * p<0.05; ↑ improve; ↔ no difference statistically. CSFQ = Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, XR = Extended Release.

3.6. Females with HSSD

Four studies have investigated the effect of bupropion on females with HSSD (Table 5). Two RCTs [17, 21] investigated the effect of bupropion versus placebo in 298 non-depressed, premenopausal females with HSDD. In a 12-week study randomizing treatment-seeking women with regular menstrual cycles, Safarinejad et al. [21] reported a statistically significant increase in the mean composite score on the BISF-W with 114% and 9% increments from baseline to 12-weeks post-intervention in the bupropion group versus the placebo group, correspondingly with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.2 (95% CI 2.1-6.3; P=0.001). A similar observation was made by an earlier, smaller trial [17] of 16 weeks’ duration, enrolling females with idiopathic, global HSSD. In this study, Segraves and colleagues [23] reported a statistically significant improvement in the total CSFQ score (P=0.0002) for bupropion versus placebo.

Table 5.

Summary of studies reported on effectiveness of bupropion in subjects with HSDD.

| Study | NHMRC Evidence Hierarchy | Quality | Scale | Improvement in Sexual Functioning as a Whole | Improvement in Sexual Desire/Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad 2010 [21] | Level II | 100% | BISFW, GEQ | ↑*** | ↑*** |

| Segraves 2004 [17] | Level II | 100% | CSFQ | ↑*** | ↔ |

| Hartmann 2012 [25] | Level III-3 | 100% | FSFI | ↔ | ↔ |

| Segraves 2001 [27] | Level III-3 | 87% | CGI-I, investigator rated scale | ↑*** | ↑*** |

*** p<0.001; ↑ improve; ↔ no difference statistically. NHMRC = Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; CSFQ = Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression-Investigator Rated, BISFW = Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women and GEQ = Global Effiacy Question

Additionally, findings from non-randomized single-arm trials (Segraves 2001) are in parallel with their RCT counterparts. Segraves and colleagues [27] conducted an 8-week single-blind active treatment phase with bupropion SR following a 4-week run-in with placebo. Of the 51 female participants, 29% responded to treatment. However, a more recent, smaller-scale study found no difference in the overall pre- and post-treatment FSFI scores among 10 females who entered a 20-week bupropion treatment phase (Hartmann 2012).

3.7. Improvement of Sexual Desire

All of the included studies evaluated the effect of bupropion on sexual desire disorder. Seven studies [20, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29] reported statistically significant improvement, whereas four studies [17, 23, 24, 25] observed no significant changes after treatment with bupropion (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of results of bupropion on sexual desire outcome.

| Study |

NHMRC

Evidence Hierarchy |

Quality | Scale |

Improvement in Sexual

Desire/Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad 2011 [20] | Level II | 100% | FSFI, CGI-SF | ↑*** |

| Safarinejad 2010 [21] | Level II | 100% | BISFW, GEQ | ↑*** |

| Segraves 2004 [17] | Level II | 100% | CSFQ | ↔ |

| Thase 2006 [22] | Level II | 100% | CSFQ | ↑* |

| Clayton 2004 [23] | Level II | 94% | CSFQ | ↔ |

| Kennedy 2006 [24] | Level II | 94% | Sex FX | ↔ |

| Hartmann 2012 [25] | Level III-3 | 100% | FSFI | ↔ |

| DeFronzoDobkin 2006 [26] | Level III-3 | 93% | CSFQ | ↑** |

| Segraves 2001 [27] | Level III-3 | 87% | CGI-I, investigator rated scale | ↑*** |

| Mathias 2006 [28] | Level III-3 | 64% | ASEX | ↑* |

| Gitlin 2002 [29] | Level IV | 79% | ASEX | ↑** |

Legend: ↑= increase; ↔ = no improvement.

3.8. Secondary Outcomes

The effects of bupropion on other domains of sexual dysfunction were reported inconsistently across the included studies (Table 6a). These studies include arousal (n=11 [17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]), lubrication (n=4 [20, 25, 28, 29]), orgasm (n=10 [17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29]), satisfaction (n=7 [20, 21, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29]), pain (n=2 [20, 25]), pleasure (n=2 [17, 22]), frequency (n=3 [21, 22, 23]), receptive to positive responses to partner initiation (n=2 [17, 21]), fantasy (n=1 [27]), improvement in distress (n=1 [21]), and tolerability (n=1 [21]).

Table 6a.

Secondary outcomes.

| Study | NHMRC Evidence Hierarchy | Quality | Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasm |

Satis-

faction |

Pain | Pleasure | Frequency |

Receptive/

Positive Response to Partner Initiation |

Fan-

tasy |

Rela--

tion ship |

Improve ment in Distress | QOL | Tolerability | Dropout Rate Due to SE in Bupropion Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad 2010a | Level II | 100% | ↑** | ↑*** | ↑*** | ↑*** | ↔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3% |

| Safarinejad 2010b | Level II | 100% | ↑*** | - | ↑*** | ↑*** | - | - | ↑*** | ↑** | - | ↑** | ↑** | - | Yes*** | 3% |

| Segraves 2004 | Level II | 100% | ↑* | - | ↑** | - | - | ↑*** | ↑* | - | - | - | - | - | 13% | |

| Thase 2006 | Level II | 100% | ↑* | - | ↑* | - | - | ↑* | ↑* | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6% |

| Clayton 2004 | Level II | 94% | ↔ | - | ↔ | - | - | - | ↑* | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12% |

| Kennedy 2006 | Level II | 94% | ↔ | - | ↔ | ↔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12% |

| Hartmann 2012 | Level III-3 | 100% | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | - | - | - | - | ↓* | - | ↔ | - | 25% |

| DeFronzoDobkin 2006 | Level III-3 | 93% | ↑*** | - | ↑*** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 17% |

| Segraves 2001 | Level III-3 | 87% | ↑*** | - | - | (39%)× | - | - | - | - | ↑*** | - | - | - | - | 9% |

| Mathias 2006 | Level III-3 | 64% | ↑* | ↑* | ↑* | ↑*# | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ↔ | - | NR |

| Gitlin 2002 | Level IV | 79% | ↑** | ↔ | ↑* | ↔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13% |

Legend: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, ↑ improve; ↔ no difference; ↓ worsen; (39%) × reported improvement but no significant; # Significant at 4 weeks but not significant at; NR not report.

Secondary outcomes from the 11 studies noted that 8 studies reported a significant improvement in arousal, 2 out of 4 studies reported a significant improvement in lubrication, and 7 out of 10 studies reported a substantial improvement in orgasm. For another domain, 4 out of 7 studies reported a significant improvement in satisfaction, all 2 studies reported a significant improvement in pleasure, and all 3 studies reported a significant improvement in frequency.

3.9. Meta-analysis

For our primary outcome, i.e., the effects of bupropion on sexual desire dysfunction, 4 studies are eligible for meta-analysis. However, 2 studies have given dichotomous data while another 2 studies provided continuous data of the FSFI-sexual desire sub-scales mean score with a standard deviation of both treatments and comparator group. We apply a combination of data by converting 2 studies of continuous data to log OR and log SE by multiplying by π/√3=1.814 (reference: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2, 2021). We calculated the log OR and log SE of another 2 studies with dichotomous data. Lastly, we ran a meta-analysis by using the generic-inverse variant method. A funnel plot was not presented because less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

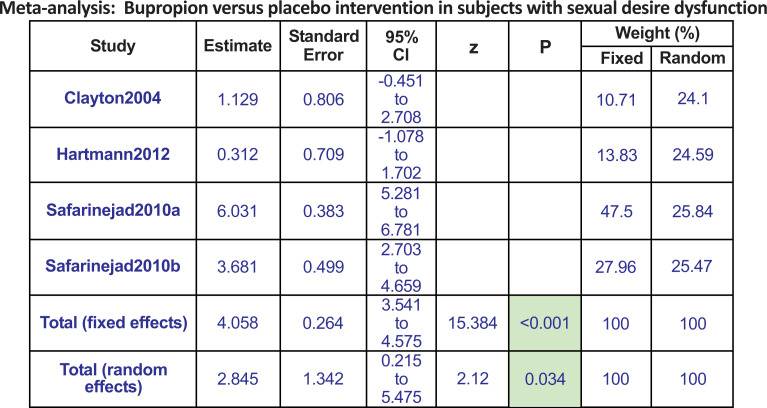

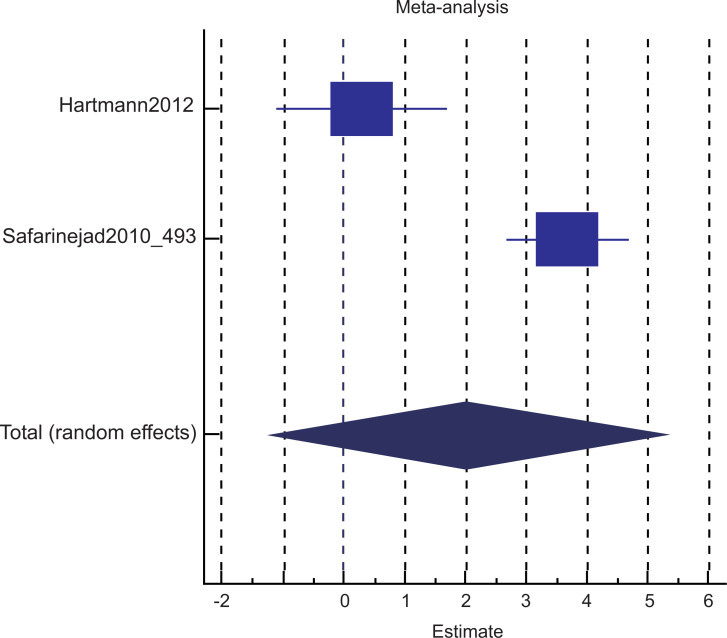

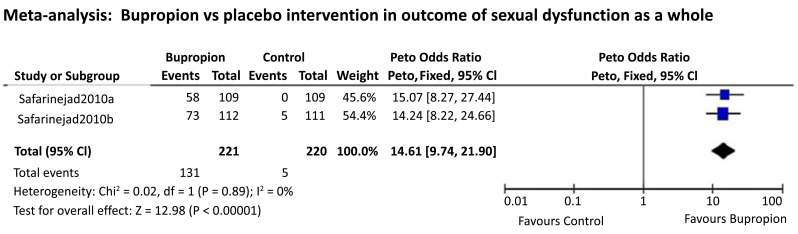

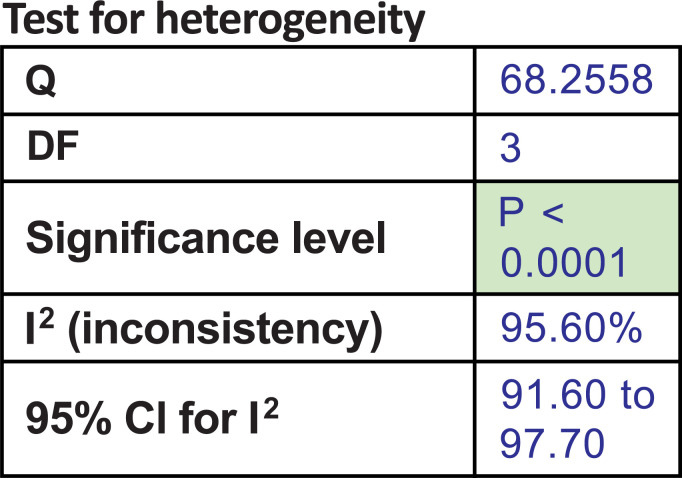

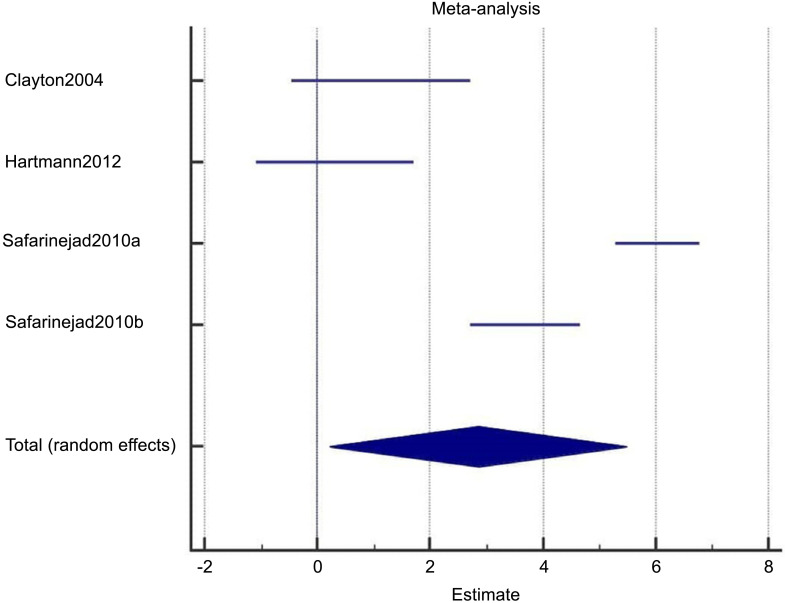

All 4 studies compared bupropion with a placebo. We found bupropion to be 2.8 times more favorable in improving sexual desire dysfunction (pool estimate 2.845, 95% CI: 0.215 to 5.475, I2= 95.6%, p=0.034) (Figs. 2a-c).

Fig. (2a).

The total random effects for the meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention in subjects with sexual desire dysfunction.

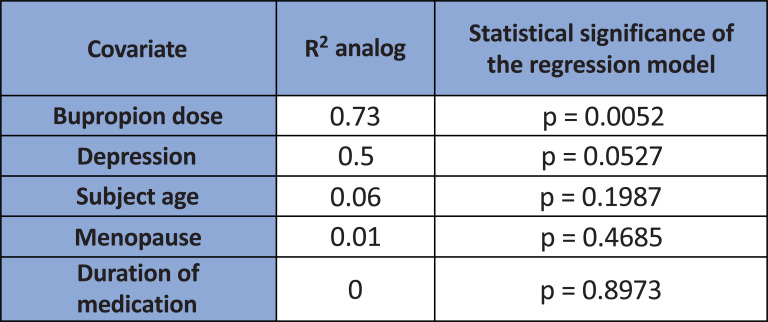

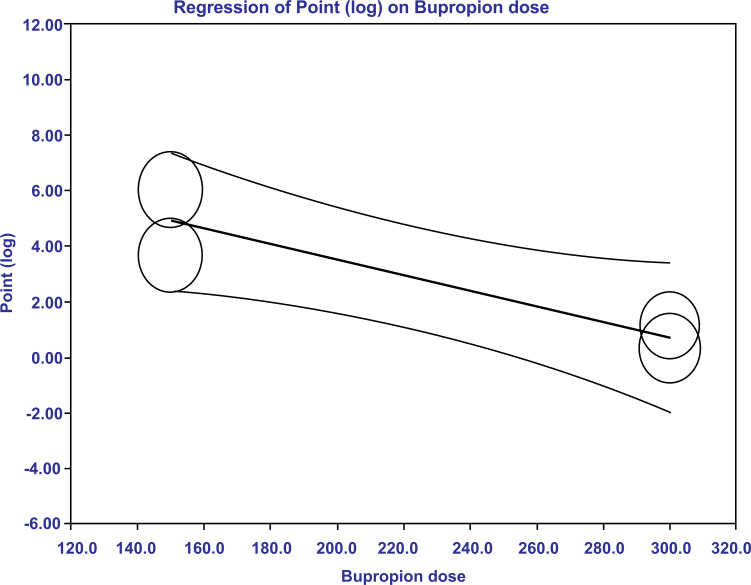

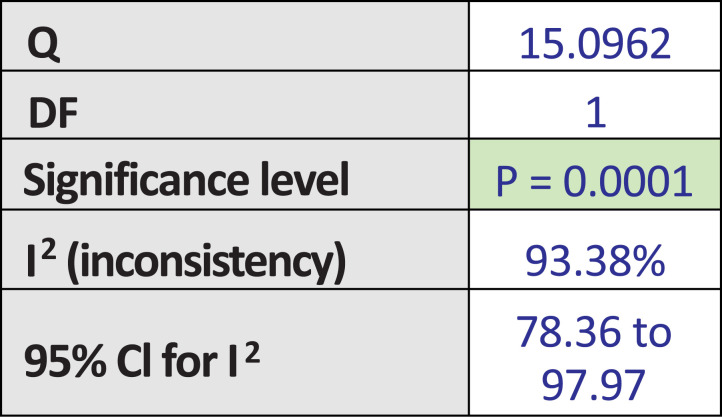

Given high heterogeneity, we ran a meta-regression analysis after the meta-analysis. In the meta-regression, we found that only the bupropion dosage was statistically significant in explaining the variance (R2=0.73, p=0.0052) (Fig. 3a). An amount of 150 mg dose of bupropion had a greater treatment effect size compared to 300 mg in subjects with sexual desire dysfunction (Fig. 3b). The dose effects explained 73% of the variance. In this study, we were unable to calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) because data were combined from dichotomous and continuous data, both of which had been converted to logarithmic form.

Fig. (3a).

The meta-regression revealed only bupropion dosage to be statistically significant in explaining the variance (R2=0.73, p=0.0052). Depression in the covariate refers to the severity of depression.

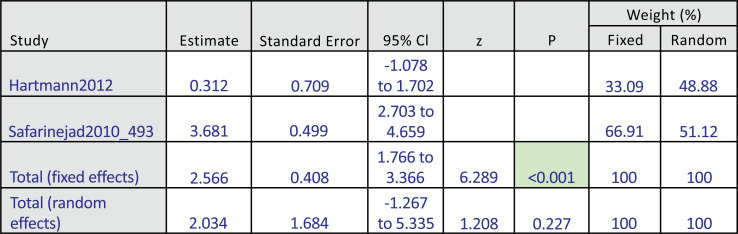

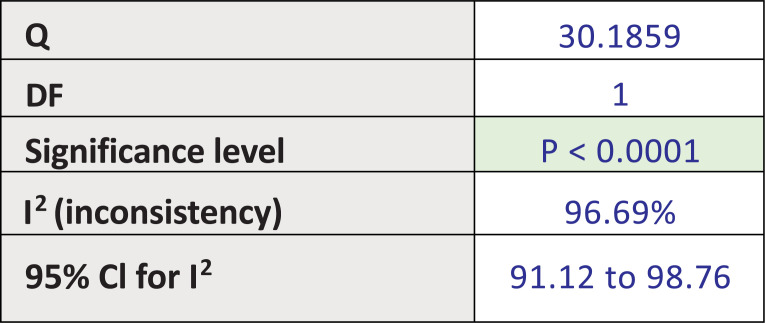

Among these 4 studies that focused on the outcome of sexual desire, we found 2 studies that targeted HSDD, while another 2 studies focused on SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction. Thus, we ran a subgroup analysis. Both subgroup analyses did not show significant improvement in the bupropion group in the random-effect model. The results were as follows: subgroup analysis for bupropion treatment in HSDD (pool estimate 2.034, 95% CI: -1.267 to 5.335, p=0.227) (Fig. 4a). The test for heterogeneity for the meta-analysis for bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD) is illustrated in (Fig. 4b), which shows that those studies were heterogenous. Fig (4c) illustrates the Forrest plot for the meta-analysis for bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD).

Fig. (4a).

The total random effects for the meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD).

Fig. (4c).

Forest-plot graph on meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD).

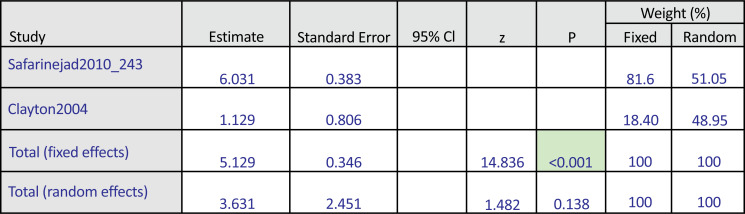

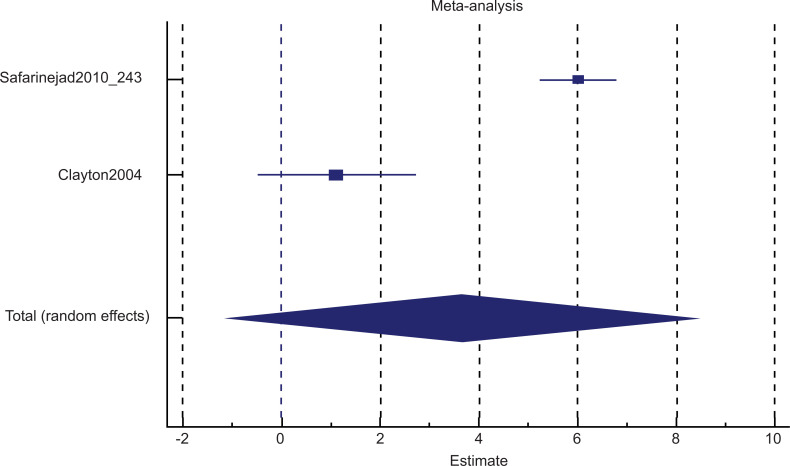

Fig. (5a) illustrates the subgroup analysis for bupropion treatment in SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction (pool estimate 3.631, 95% CI: -1.172 to 8.435, p=0.138). The test for heterogeneity for the meta-analysis for bupropion treatment in SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction is illustrated in Fig. (5b), which shows that those studies were heterogenous. Fig. (5c) illustrates the Forrest plot for the meta-analysis of bupropion treatment in SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction.

Fig. (5a).

The subgroup analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction.

Fig. (5b).

The test for heterogeneity for the meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction.

Fig. (5c).

The Forrest plot for the meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with SSRI-induced sexual desire dysfunction.

There were 2 studies that compared bupropion SR with placebo on the outcome of sexual dysfunction improvement reported as a whole, which is eligible to run a small meta-analysis. Since both studies had a similar sample size (N=109 vs. 112) and the dichotomous data enabled for odds ratio comparison, thus running a meta-analysis using the Peto odds ratio method was deemed unbiased in this case. We found that in comparison to the placebo, bupropion SR is 14 times more favorable for improving FSD (Fig. 6).

Fig. (6).

Meta-analysis: Bupropion vs. placebo intervention in outcome of sexual dysfunction as a whole.

3.10. NHRMC Evidence Statement Matrix

It was important to identify and treat women with sexual desire disorders, either due to hypoactive sexual desire disorders or SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in those with depression. This systematic review found that bupropion has a significant role in treating women with sexual desire disorders. The NHMRC evidence statement matrix is summarized in Table 7. An overall grade B recommendation indicates that the body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice in most situations (Table 7).

Table 7.

NHRMC evidence statement matrix.

| Components | Grade | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence base | A-Excellent | 6 out of 11 studies are level II studies. The quality of studies is good, 8 out of 11 studies score 90% and above. |

| Consistency | B-Good | Most studies, including 3 out of 6 studies of high-quality level II and 3 out of 4 studies of level III-3 concluded consistently. Among the 3 level II studies that reported no significant improvement, 2 studies showed an improvement trend; another 1 study has a significant baseline sexual functioning difference in comparison with the comparative group which may indicate allocation bias. |

| Clinical impact | C-Moderate | 6 out of 11 studies including those with higher-quality reported statistical significance; however, the studies’ context varied (HSDD, SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, etc.). The dropout rate due to side effects is around 3-12%. |

| Generalizability | C-Evidence is not directly generalizable to the target population but could be sensibly applied to the target population. | The included studies were conducted in different countries with subjects of 29–50-year-old women with sexual dysfunction, especially sexual desire dysfunction. However, the evidence is sensibly to be generalized for women with sexual desire disorder. |

| Grade of recommendation | B | Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice in most situations. |

The 5th indicator of the NHRMC Evidence Statement Matrix is “applicability,” which refers to applicability within the Australian healthcare context. It was deemed not relevant and thus not rated for the finding of this review.

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported the benefit of bupropion as a pharmacological agent in the treatment of HSDD. There was a study in 2015 by Bolduan and Haas [18] where a systematic review was performed without a meta-analysis. In their research, two studies (289 women) were included. One study had a low risk of bias, the other had a high risk of bias, and both trials reported tolerability of bupropion and improvement in sexual desire with the treatment ranging from 12 weeks to 112 days.

In our study, we found bupropion to be almost three-fold more favorable in improving problems with sexual desire (pool estimate of 2.845, 95% CI: 0.215 to 5.475, I2= 95.6%, p=0.034). Because of high heterogeneity, we performed a meta-regression and found only the dosage of bupropion to be statistically significant in explaining the variance, i.e., 150mg shows higher treatment effects on the sexual desire among women with HSDD. On another outcome, using the Peto odds ratio method of 2 studies comparing bupropion SR with placebo, we found that bupropion SR is 14 times more favorable in improving FSD.

There were also secondary outcomes in other domains of sexual function from the study. The outcomes from 8 out of the 11 studies reported a significant improvement in sexual arousal; 2 out of 4 studies reported a significant improvement in vaginal lubrication, 7 out of 10 studies reported a significant improvement in orgasm, and 4 out of 7 studies reported a significant improvement in sexual satisfaction, respectively. The outcome also reported that all 2 studies stated a significant improvement in sexual pleasure, and all 3 studies reported a significant improvement in sexual intercourse frequency.

For the secondary outcomes, it is interesting to note the benefits of bupropion for sexual arousal. It is predicted that other domains of sexual functioning, i.e., sexual arousal, orgasmic capabilities, and sexual satisfaction, also improved tremendously as they formed sequential sexual responses, besides the initiation from the sexual desire [30, 31]. As there was a strong correlation between sexual arousal and sexual desire, improvement was also noted concomitantly in the sexual arousal domain. Studies have shown that sexual desire and sexual arousal form a unitary domain in the sexual response cycle, and there is an overlap between these two entities. For example, Basson (2005) [30] stated that women’s sexual motives are far more complex than merely the presence or lack of sexual desire (characterized as thinking, imagining, or fantasizing about sex and longing for sexual activities between actual sexual encounters). Basson et al. (2004 and 2005) [31, 32] proposed a nonlinear model of sexual response that seeks to more accurately portray the domain of desire and the underlying motivational forces that activate it. Sexual arousal and sexual desire co-occur and strengthen or reinforce each other. Women’s subjective sexual arousal may be minimally influenced by genital congestion (sexual arousal) [31]. In the Asian context, Sidi et al. (2008) [33] also reported in their factor analysis study that sexual arousal and sexual desire co-occur and may form a single clinical entity of sexual functioning. More studies are needed to replicate the advantageous impact of the treatment and the possible adverse effects, particularly with long use. Coordinating research resources for this medical condition is pivotal to understanding the impact of HSDD on many women and their partners.

Treatment of HSDD in premenopausal women with an NDRI agent, bupropion, may have the potential to assist women suffering from this common clinical challenge and yet complex condition. Bupropion, the only currently available NDRI, acts via dual inhibition of norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake, which represents a novel mechanism for a pharmacological agent [34]. As such, bupropion is linked to a unique clinical profile with an action on the firing of both dopaminergic and norepinephrine neural pathways [34, 12]. For the dopaminergic system, this agent targets the reward pathway in the brain, i.e., especially the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra, which are pivotal for incentive-based behavioral actions like sexual performance and sexual desire [35-37].

The present review had several limitations. First, this systematic review and meta-analysis included a relatively small number of randomized clinical trials in this field of research, with numerous studies focusing more on clinical depression as the main or primary objective. Thus, addressing FSD and HSDD are the secondary observations in almost all the studies. Second, the high heterogeneity reflected by the high I2 between the included small numbers of studies may influence the interpretation of the effect estimates generated. Finally, as the search strategy approach was limited to merely English articles, thus, the review was subjected to publication bias. Nevertheless, the extensive and comprehensive search of the databases search engines provided an accurate estimate of the association between the benefits of bupropion and women’s sexual desire. We managed to perform a meta-regression, and this adds more strength to our study. Furthermore, the inclusion of moderate to good quality studies added to the strength of this review.

As HSDD is a common yet complex clinical challenge, numerous approaches have been examined and tested. Based on the data and statistical analysis of this meta-analysis, the use of bupropion in women with HSDD may be effective in enhancing sexual desire, leading to overall improved sexual arousal, orgasm, and sexual satisfaction. More studies are needed to better understand the beneficial impact of the treatment and the potential side effects, particularly with prolonged use. Organizing research resources around this clinical entity, like mindfulness, psychological support, and empathy from the partner, is important as a holistic approach for treating the patient.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of this meta-analysis and systematic review, there is a potential role of bupropion as an effective treatment for a woman with HSDD, despite the fact that the woman is not clinically depressed. Bupropion should be considered as an option for pharmacological intervention, alongside other psychopharmacological agents in the amalgamation of bio-psycho-social perspective of intervention, like participation of her husband in the therapy and other psychosocial measures like psychotherapy and marital session.

These findings support the notion that clinicians should evaluate both sexual desire and arousal together in their clinical practice. As sexual matters are complex with several bio-psycho-social dimensions, an interdisciplinary approach is needed and not merely dependent on pharmacological agents. A further longitudinal study is necessary to identify factors that may contribute to the benefits vs. risk factors for the use of bupropion in women with HSDD and FSD.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines were followed for the study.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1: Modified McMaster Critical Review Form.

McMaster Critical Review Form is modified to suit the studies included in this review, which are mainly etiological studies, so the intervention domain was taken out. Two questions are added for quality assessment of prospective cohort studies, i.e. were the groups randomized and was randomization appropriately done. Providing 1 point for every answer of “Yes”, making the total score 13. In case of non-prospective cohort studies, those 2 questions added will be not applicable (NA) and the total score will be reduced to 11.

| Domains | Yes | No | Not addressed | Not Applicable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study purpose | Yes | No | Na | NA |

| 1. Was the purpose stated clearly? | - | - | - | - |

| Literature review | Yes | No | Na | NA |

| 2. Was relevant background literature reviewed? | - | - | - | - |

| Sample | Yes | No | Na | NA |

| 3. Was the sample described in detail? | - | - | - | - |

| 4. Was sample size justified? | - | - | - | - |

| 5. Were the groups randomized? | - | - | - | - |

| 6. Was randomization appropriately done? | - | - | - | - |

| Outcome | Yes | No | Na | NA |

| 7. Were the outcome measures reliable? | - | - | - | - |

| 8. Were the outcome measures valid? | - | - | - | - |

| Results | Yes | No | Na | NA |

| 9. Were results reported in terms of statistical significance? | - | - | - | - |

| 10. Were the analysis of method(s) appropriate? | - | - | - | - |

| 11. Was clinical importance reported? | - | - | - | - |

| 12. Were drop-outs reported? | - | - | - | - |

| Conclusions | Yes | No | Na | NA |

| 13. Were conclusions appropriate, given study methods and results? | - | - | - | - |

Fig. (2b).

The test for heterogeneity for the meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention in subjects with sexual desire dysfunction.

Fig. (2c).

Forest-plot graph on meta-analysis for bupropion versus placebo intervention in subjects with sexual desire.

Fig. (3b).

Meta-regression plot (bubble plot) examining the change in estimate effects with changes in bupropion dosage. The regression line of the effect size moves closer to zero when bupropion dose increases. This means that the estimated treatment effects (when adjusted for the other covariates) decrease upon increasing bupropion dose from 150mg to 300mg.

Fig. (4b).

The test for heterogeneity for the meta-analysis: Bupropion versus placebo intervention among females with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basson R., Brotto L.A., Laan E., Redmond G., Utian W.H. Assessment and management of women’s sexual dysfunctions: Problematic desire and arousal. J. Sex. Med. 2005;2(3):291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basson R., Leiblum S., Brotto L., Derogatis L., Fourcroy J., Fugl-Meyer K., Graziottin A., Heiman J.R., Laan E., Meston C., Schover L., van Lankveld J., Schultz W.W. Definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction reconsidered: Advocating expansion and revision. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003;24(4):221–229. doi: 10.3109/01674820309074686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton A.H., Kingsberg S.A., Goldstein I. Evaluation and management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Sex. Med. 2018;6(2):59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graziottin A. Prevalence and evaluation of sexual health problems--HSDD in Europe. J. Sex. Med. 2007;4(Suppl. 3):211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Available from: https://www. psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm Retrieved on 16 December 2020.

- 6.Frances A., First M.B., Pincus H.A. DSM-IV guidebook. American Psychiatric Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segraves R.T. Overview of sexual dysfunction complicating the treatment of depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. Monogr. 1992;10(2):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavoussi R.J., Segraves R.T., Hughes A.R., Ascher J.A., Johnston J.A. Double-blind comparison of bupropion sustained release and sertraline in depressed outpatients. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1997;58(12):532–537. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v58n1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chew P.Y., Choy C.L., Sidi H.B., Abdullah N., Che Roos N.A., Salleh Sahimi H.M., Abdul Samad F.D., Ravindran A. The association between female sexual dysfunction and sexual dysfunction in the male partner: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sex. Med. 2021;18(1):99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Portman D.J., Brown L., Yuan J., Kissling R., Kingsberg S.A. Flibanserin in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results of the PLUMERIA study. J. Sex. Med. 2017;14(6):834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.03.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloemers J., van Rooij K., de Leede L., Frijlink H.W., Koppeschaar H.P.F., Olivier B., Tuiten A. Single dose sublingual testosterone and oral sildenafil vs. a dual route/dual release fixed dose combination tablet: A pharmacokinetic comparison. . Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016;81(6):1091–1102. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stahl S.M., Pradko J.F., Haight B.R., Modell J.G., Rockett C.B., Learned-Coughlin S. A review of the neuropharmacology of bupropion, a dual norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2004;6(4):159–166. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v06n0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modell J.G., May R.S., Katholi C.R. Effect of bupropion-SR on orgasmic dysfunction in nondepressed subjects: A pilot study. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(3):231–240. doi: 10.1080/00926230050084623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fava M., Rush A.J., Thase M.E., Clayton A., Stahl S.M., Pradko J.F., Johnston J.A. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: From bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106–113. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v07n0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen R.C., Lane R.M., Menza M. Effects of SSRIs on sexual function: A critical review. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(1):67–85. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy S.H., McCann S.M., Masellis M., McIntyre R.S., Raskin J., McKay G., Baker G.B. Combining bupropion SR with venlafaxine, paroxetine, or fluoxetine: A preliminary report on pharmacokinetic, therapeutic, and sexual dysfunction effects. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2002;63(3):181–186. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v63n0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segraves R.T., Clayton A., Croft H., Wolf A., Warnock J. Bupropion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(3):339–342. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000125686.20338.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolduan A.J., Haas D.M. A systematic review of the use of bupropion for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. J. Woman’s. Reprod. Heal. 2015;1(1):14–23. doi: 10.14302/issn.2381-862X.jwrh-14-546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page M.J., Moher D., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J.M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M.M., Li T., Loder E.W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., McGuinness L.A., Stewart L.A., Thomas J., Tricco A.C., Welch V.A., Whiting P., McKenzie J.E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safarinejad M.R. Reversal of SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction by adjunctive bupropion in menstruating women: A double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(3):370–378. doi: 10.1177/0269881109351966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safarinejad M.R., Hosseini S.Y., Asgari M.A., Dadkhah F., Taghva A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of bupropion for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in ovulating women. BJU Int. 2010;106(6):832–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thase M.E., Clayton A.H., Haight B.R., Thompson A.H., Modell J.G., Johnston J.A. A double-blind comparison between bupropion XL and venlafaxine XR: Sexual functioning, antidepressant efficacy, and tolerability. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(5):482–488. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000239790.83707.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayton A.H., Warnock J.K., Kornstein S.G., Pinkerton R., Sheldon-Keller A., McGarvey E.L. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion SR as an antidote for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):62–67. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy S.H., Fulton K.A., Bagby R.M., Greene A.L., Cohen N.L., Rafi-Tari S. Sexual function during bupropion or paroxetine treatment of major depressive disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2006;51(4):234–242. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann U.H., Rüffer-Hesse C., Krüger T.H.C., Philippsohn S. Individual and dyadic barriers to a pharmacotherapeutic treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorders: Results and implications from a small-scale study with bupropion. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2012;38(4):325–348. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.606495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobkin R.D., Menza M., Marin H., Allen L.A., Rousso R., Leiblum S.R. Bupropion improves sexual functioning in depressed minority women: An open-label switch study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000194623.07611.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segraves R.T., Croft H., Kavoussi R., Ascher J.A., Batey S.R., Foster V.J., Bolden-Watson C., Metz A. Bupropion sustained release (SR) for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in nondepressed women. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(3):303–316. doi: 10.1080/009262301750257155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathias C., Cardeal Mendes C.M., Pondé de Sena E., Dias de Moraes E., Bastos C., Braghiroli M.I., Nuñez G., Athanazio R., Alban L., Moore H.C., del Giglio A. An open-label, fixed-dose study of bupropion effect on sexual function scores in women treated for breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2006;17(12):1792–1796. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gitlin M.J., Suri R., Altshuler L., Zuckerbrow-Miller J., Fairbanks L. Bupropion-sustained release as a treatment for SSRI-induced sexual side effects. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(2):131–138. doi: 10.1080/00926230252851870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basson R. Women’s sexual dysfunction: Revised and expanded definitions. CMAJ. 2005;172(10):1327–1333. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basson R., Leiblum S., Brotto L., Derogatis L., Fourcroy J., Fugl-Meyer K., Graziottin A., Heiman J.R., Laan E., Meston C., Schover L., van Lankveld J., Schultz W.W. Revised definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2004;1(1):40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basson R. Using a different model for female sexual response to address women’s problematic low sexual desire. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(5):395–403. doi: 10.1080/713846827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidi H., Naing L., Midin M., Nik Jaafar N.R. The female sexual response cycle: Do Malaysian women conform to the circular model? J. Sex. Med. 2008;5(10):2359–2366. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferris R.M., Cooper B.R. Mechanism of antidepressant activity of bupropion. J. Clin. Psychiatry. Monogr. 1993;11(1):2–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadighparvar S., Tale F., Shahabi P., Naderi S., Ghaderi Pakdel F. The response of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons to bupropion: Excitation or inhibition? Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2019;10(4):281–304. doi: 10.32598/bcn.9.10.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nutt D.J., Baldwin D.S., Clayton A.H., Elgie R., Lecrubier Y., Montejo A.L., Papakostas G.I., Souery D., Trivedi M.H., Tylee A. Consensus statement and research needs: The role of dopamine and norepinephrine in depression and antidepressant treatment. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl. 6):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabre L.F., Brodie H.K., Garver D., Zung W.W. A multicenter evaluation of bupropion versus placebo in hospitalized depressed patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1983;44(5 Pt 2):88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.