Abstract

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) technology can realize the development of drugs for non-druggable targets that are difficult to achieve with traditional small molecules, and therefore has attracted extensive attention from both academia and industry. Up to now, there are more than 600 known E3 ubiquitin ligases with different structures and functions, but only a few have developed corresponding E3 ubiquitin ligase ligands, and the ligands used to design PROTAC molecules are limited to a few types such as VHL (Von-Hippel-Lindau), CRBN (Cereblon), MDM2 (Mouse Doubleminute 2 homolog), IAP (Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins), etc. Most of the PROTAC molecules that have entered clinical trials were developed based on CRBN ligands, and only DT2216 was based on VHL ligand. Obviously, the structural optimization of E3 ubiquitin ligase ligands plays an instrumental role in PROTAC technology from bench to bedside. In this review, we review the structure optimization process of E3 ubiquitin ligase ligands currently entering clinical trials on PROTAC molecules, summarize some characteristics of these ligands in terms of druggability, and provide some preliminary insights into their structural optimization. We hope that this review will help medicinal chemists to develop more druggable molecules into clinical studies and to realize the greater therapeutic potential of PROTAC technology.

Keywords: PROTACs, E3 ubiquitin ligase ligand, structure optimization, clinical trials, CRBN

1 Introduction

The degradation of most damaged and soluble misfolded proteins is achieved by the 26S proteasome through ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS)-mediated protein degradation (Paiva et al., 2019; Pohl et al., 2019; Kawahata et al., 2020). In the UPS, the proteasome conjugated to a protein substrate through enzymatic cascade (Hershko et al., 1983; Hershko et al., 1992; Komander et al., 2012). First, E1 (Ub activating enzyme) binds Ub (ubiquitin) via an ATP-dependent mechanism and then transfers Ub to E2 (Ubconjugating enzyme) by forming an E2 ubiquitin conjugate (Schulman et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2009). Next, the E3 (Ub ligase) mediates the transfer of the ubiquitin from E2 to the substrate protein, followed by 26S proteasome-induced degradation or post-translational modification of the substrate protein (Zheng et al., 2017). E3 ligase mediates the specificity of protein substrates through a non-covalent or covalent mechanism, and the type of E3 ligase determines the outcome of the substrate protein. For instance, TRAF6 (tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6) interacts with YAP (Yes-associated protein) and promotes its ubiquitination to enhance YAP stability (Liu et al., 2020). c-Cbl (Casitas B lymphoma) binds to the intracytoplasmic tail of PD-1 and targets it for ubiquitination-proteasomal degradation in macrophages, resulting in downregulation of PD-1 and reduced surface expression leading to increased tumor phagocytosis and tumor suppression (Lyle et al., 2019).

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) is based on proteasomes (Schapira et al., 2019). These bifunctional molecules consist of three parts: An E3-recruiting ligand, a POI (protein of interest) targeting warhead, and a linker connecting the two ligands (Sun et al., 2019). PROTAC degraders mediate their own formation of POI-PROTAC-E3 complexes with substrate proteins and E3 ubiquitin ligases, which lead to the degradation of the substrate protein via UPS (Wang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). There are many target-based POI warheads and linkers available for the design and optimization of PROTAC degraders for medicinal chemists, but only a few E3 ubiquitin ligases ligands have been developed (Sun et al., 2019).

Arvinas is the first company to clinically implement two PROTAC degraders, the androgen receptor (AR) degrader ARV-110 and the estrogen receptor (ER) degrader ARV-471 (Mullard, 2019). The safety and effectiveness of ARV-110 has been demonstrated in the treatment of metastatic castrated prostate cancer (mCRPC) (Neklesa et al., 2018; Neklesa et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2022), and ARV-471 also has shown great potential in the treatment of breast cancer (Snyder et al., 2021). Since ARV-110 and ARV-471 entered clinic trials, an increasing number of protein targets have emerged to develop clinical degraders of PROTACs, such as BRD9 and IRAK4 (Table 1), while antitumor is currently the most concentrated field of research for PROTACs, except for KYMERA’s degrader KT-474, which is the only clinical degrader for autoimmune-disease (Békés et al., 2022). These PROTACs degraders are based on different E3 ligands, but mainly on CRBN-based ligands.

TABLE 1.

PROTAC degraders in clinical development.

| Company | Degrader | Target | E3 ligase | ROA | Highest phase | Clinical trial no. (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arvinas | ARV-110 | AR | CRBN | Oral | Phase II | NCT03888612 |

| Arvinas | ARV-766 | AR | Undisclosed | Oral | Phase I | NCT05067140 |

| Arvinas/Pfizer | ARV-471 | ER | CRBN | Oral | Phase II | NCT04072952 |

| Accutar Biotech | AC682 | ER | CRBN | Oral | Phase I | NCT05080842 |

| Bristol Myers Squibb | CC-94676 | AR | CRBN | Oral | Phase I | NCT04428788 |

| Dialectic Therapeutics | DT2216 | BCL-XL | VHL | I.v | Phase I | NCT04428788 |

| Foghorn Therapeutics | FHD-609 | BRD9 | Undisclosed | Oral | Phase I | NCT04965753 |

| Kymera | KT-413 | IRAK4 | CRBN | I.v | Phase I | NA |

| Kymera | KT-333 | STAT3 | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | Phase I | NA |

| Kymera/Sanofi | KT-474 | IRAK4 | Undisclosed | Oral | Phase I | NCT04772885 |

| Nurix Therapeutics | NX-2127 | BTK | CRBN | Oral | Phase I | NCT04830137 |

| Nurix Therapeutics | NX-5948 | BTK | CRBN | Oral | Phase I | NCT04830137 |

| C4 Therapeutics | CFT8634 | BRD9 | CRBN | Oral | IND- e | NA |

| C4 Therapeutics | CFT8919 | EGFRL858R | CRBN | Oral | IND- e | NA |

| Cullgen | CG001419 | TRK | CRBN | Oral | IND- e | NA |

NA, not applicable.

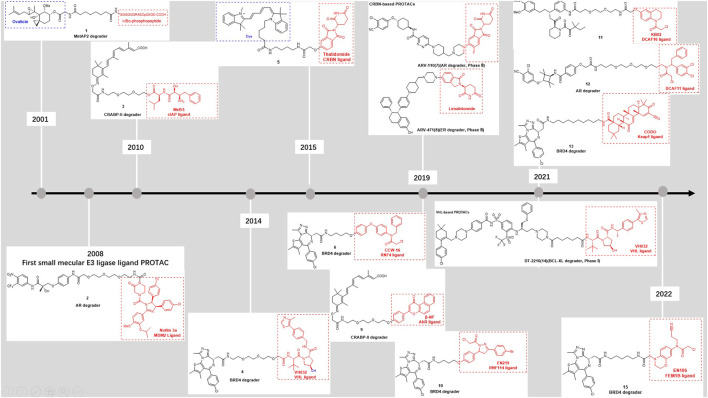

The first PROTAC was discovered in 2001 by Craig Crews, founder of Arvinas (Sakamoto et al., 2001) (Figure 1). This compound consists of a covalent small molecule inhibitor of MetAP-2, and IκBα-phosphopeptide, enabling the ligase to ubiquitylate METAP2. As the first attempt to explore PROTACs, this compound exposed the poor cell permeability prevented it from being widely used, and the structure of phosphopeptides in this type of PROTAC is easily hydrolyzed by intracellular phosphatase, which reduces its stability. Therefore, the desired small molecule E3 ligase ligand, must have good membrane permeability, be stable in vitro environment and have strong affinity to E3 ubiquitin ligase, on the basis of which PROTACs will have stronger druggability.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of E3 ligases ligands discoveries.

In the past 2 decades, various E3 ligase ligands based on different functions have been reported. Such as MDM2 ligand (Honda et al., 1997; Schneekloth et al., 2008; Saadatzadeh et al., 2017), cIAP ligands (Sato et al., 2008; Itoh et al., 2011; Ohoka et al., 2017), VHL ligand (Schneekloth et al., 2004; Rodriguez-Gonzalez et al., 2008), CRBN ligand (Winter et al., 2015), AhR (Aryl hydrocarbon receptor) ligand (Ohtake et al., 2007; Ohoka et al., 2019), DCAF (DDB1- And CUL4-Associated Factor) 11 and 15 and 16 ligands (Han et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021), RNF (RING finger protein) 4 and 114 ligands (Kumar et al., 2019; Ward et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2021), FEM1B (Fem-1 Homolog B) ligand (Henning et al., 2022), KEAP1 (Kelch Like ECH Associated Protein 1) ligand (Tong et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2021; Pei et al., 2022) (Figure 1). They were developed based on the function of different E3 ligases thus have different properties. For instance, VHL is the substrate receptor of CRL2VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase.

The Pro564 residue of HIF-1α (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α) is hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylase (also the hydroxyl group in the VHL ligands), bound to VHL proteins and subsequently ubiquitinated by CRL2VHL E3 (Ivan et al., 2001; Schneekloth et al., 2004). HIF-1α protects cells during hypoxia, and VHL-based PROTAC shows good degradation activity in most cases, and VHL ligands even reduce side effects in some cases (Jaakkola et al., 2001). However, in subsequent studies, the poor membrane permeability and low oral delivery rate of VHL ligands limited their application. The E3 ubiquitin ligase ligands are like a toolbox for PROTACs, and the appropriate “tool” is selected based on the different properties of E3 ligands for the purpose of the researchers.

In this review, we will summarize the experience of small molecule PROTACs currently entering clinical trials in optimizing E3 ligase ligands for degraders from the perspective of chemical structure. It is expected to shed light on the optimization of E3 ligase ligands for degraders of PROTACs in the future.

2 E3 ligase ligands optimization of PROTACs for clinical application

2.1 E3 ligase ligands optimization of AR PROTACs

Annually, more than 350,000 deaths are associated with prostate cancer, making the disease one of the leading causes of cancer-related death in men, and the androgen receptor (AR) is believed to drive hormone dependency of prostate cancer (Rebello et al., 2021). Key AR gene alterations contribute to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) (de Bono et al., 2020). Both enzalutamide and abiraterone have shown good results as AR antagonists in the treatment of prostate cancer. However, the drug resistance is inevitable when mutations occur in the ligand-binding domain (Teo et al., 2019). Therefore, the development of AR degraders based on PROTACs technology has become a new strategy (Pan et al., 2007).

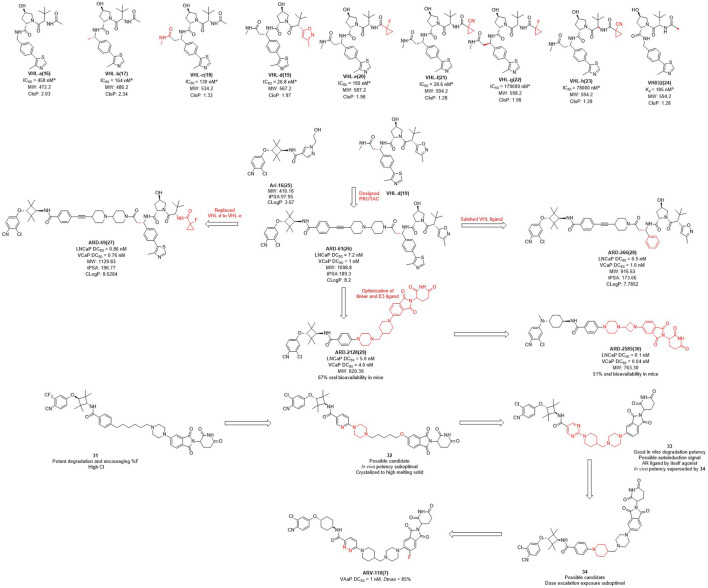

The earlier AR PROTAC was designed using enzalutamide as the AR antagonist and VHL-b ligands as E3 ligase ligand. In 2019, Wang et al. selected Ari-16 as the antagonist of the degrader by screening various VHL-based E3 ligase ligands (compounds 16–24) to build different AR degraders (Kregel et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020) (Figure 2). During E3 ligase ligand optimization process, they found that the (S)-methyl group in VHL-b exposed to the solvent environment could serve as a possible tethering point for the design of AR degraders (Han et al., 2019). Subsequently, they reported that ARD-61 is an AR degrader with DC50 (concentration that resulted in a 50% targeted protein degradation) values of 7.2 nM and 1.0 nM in LNCaP and VCaP cells, respectively. Apparently, the large molecular weight of the VHL ligand makes ARD-61 too large (MW = 1095.8) for its degradation activity to be significant. In their following work, the E3 ligase ligand part of ARD-61 was replaced with a VHL ligand and the optimized degrader ARD-69 showed AR DC50 values of 0.86 nM and 0.76 nM in LNCaP and VCaP cells, respectively. However, the molecular weight of ARD-69 was still too large as an AR degrader. Subsequently, they shortened the linker length and modified the VHL ligand to decrease its molecular weight. Thus, led to degrader ARD-266 with similar degradation activity, the AR DC50 values were 0.5 nM and 1.0 nM in LNCaP and VCaP cells, respectively (Han et al., 2019). The poor membrane permeability and low oral availability of VHL ligands led to its eventual replacement by CRBN ligands which is also used in Bristol Myers Squibb’s ER clinical degrader CC-94676. On the basis of the above three molecules, they discovered that ARD-2128 showed the same degradation activity as ARD-61 (MW = 820.4), but its molecular weight was significantly reduced and its bioavailability in mice reached 67% (Han et al., 2021). Finally, on the basis of CRBN ligand, they re-optimized the linker and the antagonist and disclosed ARD-2585, which has 51% oral bioavailability in mice and with AR DC50 of 0.10 nM and 0.04 nM in LNCaP and VCaP cells, respectively (Xiang et al., 2021).

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structures of VHL ligands and their binding affinities to VHL protein and the design and optimization of AR PROTACs. aInhibitory activity (IC50) of E3 ligands on their substrates. binding affinity (Kd) of E3 ligands to their respective substrates MW, molecular weight; tPSA, total polar surface area; cLog P, calculated Log P; *The arrows in the figure do not mean progressive relationship between these compounds.

In the pharmaceutical industry, AR degraders have also received the attention of Arvinas, whose CRBN-based AR degrader ARV-110 (Figure 2) is currently in phase II clinical trials (Snyder et al., 2021). Arvinas has also performed many optimizations for AR degradation. First of all, compounds 31 and 32 showed good degradation abilities in vitro, but also with a high clearance rate in vivo. Subsequently, they disclosed that bi-functional compound 33 showed strong degradation activity in vitro, however, poor activity in vivo, perhaps due to the metabolism of 33. The structure of compound 34 was optimized on the basis of compound 33 with improved activity in vivo, but it was dose dependent and needed further optimization. Finally, the H at position 3 of the benzene ring of the CRBN ligand of 34 was replaced with fluorine to obtain degrader ARV-110 which improved the druggability. ARV-110 was highly efficient in VCaP cells with a DC50 value with 1 nM and Dmax (maximal levels of protein degradation) of 85% (Snyder et al., 2021). Above all, the E3 ubiquitin ligand functions as the promoter of the degradation process, and optimizing the E3 ligand and modifying its molecular structure is expected to improve the activity and oral delivery rate of the degraders.

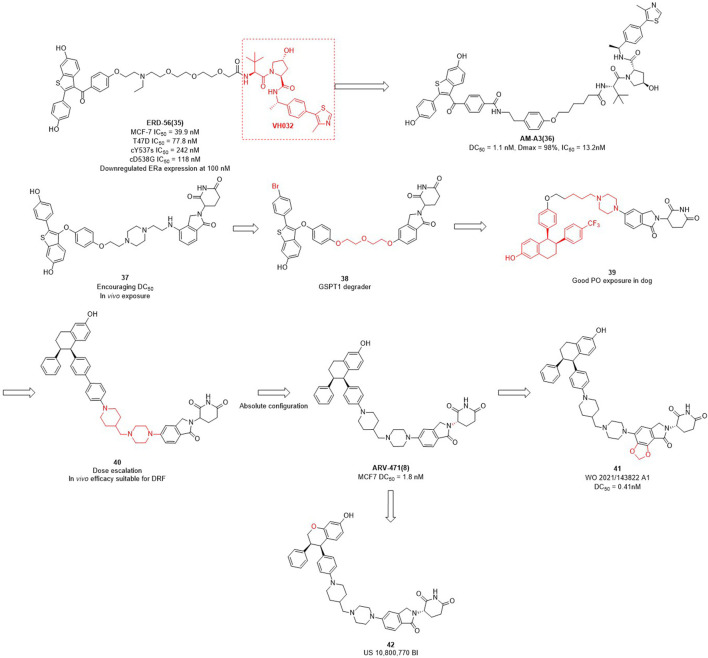

2.2 E3 ligase ligands optimization of ERα PROTACs

The importance of estrogen regulates (ER) for female breast cancer is similar to AR for male prostate cancer. ER targets are associated with 70%–80% of breast cancer profiles, and become the primary therapeutic target for this disease (Ohoka et al., 2018; Waks et al., 2019; Criscitiello et al., 2022). ERα is a member of the nuclear receptor family and plays a crucial role in mediating the estrogen signaling pathway within the mammary glands and female reproductive tract (Arnal et al., 2017). In contrast to the high expression of ERα in breast tumors, the ERα expression is low in normal breast epithelium cells (Huang et al., 2014). ERα knockout experiments in rats demonstrated that ERα plays an important role in promoting the formation of breast cancer cells in the mammary gland (Zhang et al., 2011). In addition to ERα knockout, PROTAC can also reduce the expression levels of ERα in breast. Wang et al. focused not only on AR degraders but also on ERα degraders. In their initial studies of ERα degradation, they singled out raloxifene as ERα-binding ligand and CRBN and VHL as E3 ligase ligands, respectively. Interestingly, the VHL-based PROTACs were shown to induce significant degradation of the target protein, whereas no obvious protein degradation was observed for CRBN-based molecules. Therefore, they synthesized a series of PROTACs based on raloxifene and VH032 (Figure 3). Among them, ERD-56 showed significant degradation properties of ERα protein at 100 nM, and also showed good anti-proliferative activity in MCF-7 and T47D cells with IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) of 39.9 nM and 77.8 nM (Gonzalez et al., 2020). In order to improve the potency of ERD-56, they optimized the linker and ERD-308 showed the best efficacy with DC50 of 0.17 nM (Hu et al., 2019). Interestingly, the ER protein degraders reported above were all designed based on VH032 as an E3 ligase ligand. Due to the poor druggability of VH032 itself, the druggability of ER protein degraders developed based on it was also generally poor. Different from the above studies, Arvinas has also been working on the development of ERα degraders based on CRBN. First, they designed ERα degraders based on raloxifene and lenalidomide, and found that degrader 37 (Figure 3) showed good degradation activity. Based on 37, they optimized the linker and ERα ligands to obtain the degrader 38 targeting GSPT1. Then they modified the structure of raloxifene to obtain degrader 39, due to the poor druggability of the long-chain linker, they decided to use the same linker that existed in ARV-110 to obtain degrader 40. From the activity screening experiment, it was found that the chiral degrader ARV-471 had better degradation activity than 40. The ERα degradation activity DC50 in MCF-7 cells was 1.8 nM and thus ARV-471 became another clinical degrader of Arvinas (Snyder et al., 2021). Hengrui Medicine further optimized CRBN E3 ligase ligand and improve the degradation activity of ER degraders, and found compound 41 with DC50 value of 0.41 nM in MCF-7 cells (Yang et al., 2021). Accutar Biotech undisclosed their structure of ER clinical degrader (AC682) (NCT05080842), in their research they found that the compound 42 with DC50 value of 0.3 nM in MCF-7 cells (Fan et al., 2021). In summary, the optimization of E3 ubiquitin ligase ligand is the key to improve the oral availability and potency of PROTACs.

FIGURE 3.

Design and optimization process of ER PROTACs.

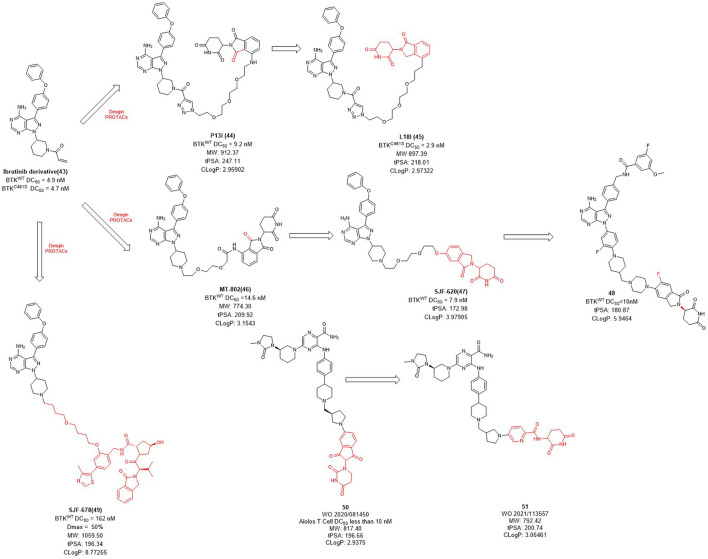

2.3 E3 ligase ligands optimization of BTK PROTACs

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is highly expressed in various of lymphoma cells and plays an essential role in B-cell receptor (BCR) signal and B cell activation (Davis et al., 2010). Since the ATP binding site of BTK is highly conserved, how to achieve kinase selectivity of BTK inhibitors becomes the key issue. Ibrutinib is the first approved BTK covalent inhibitor with high selectivity, strong activity and good oral bioavailability (Pan et al., 2007). The acrylamide warhead of ibrutinib forms a covalent bond with the sulfhydryl group of the cysteine residue 481 in BTK, which is irreversible and thus permanently inactivates BTK kinase with an IC50 value of 0.5 nM after 2 h (Pan et al., 2007). However, the C481S BTK mutation (cysteine to serine mutation at position 481) prevents the formation of the critical covalent bond with ibrutinib, leading to drug resistance (Woyach et al., 2014). In order to overcome this challenge, in 2018, Rao et al. applied the PROTAC technology for ibrutinib-resistant BTK degradation and reported P13I (Figure 4) which is an ibrutinib and pomalidomide-linked degrader with DC50 value of 9.2 nM for wild-type and DC50 value of 30 nM for ibrutinib-resistant C481S BTK in Mino cells (Sun et al., 2018). While ibrutinib has difficulty inhibiting the autophosphorylation of C481S mutant BTK, P13I is effective at low concentrations. For HBL-1 cells expressing the C481S mutant BTK, the GI50 (50% growth inhibitory concentration) of P13I was about 28 nM compared to about 700 nM for ibrutinib, a 20-fold decrease in potency. In addition, P13I showed no effect on ITK, EGFR and TEC family kinases that cause side effects. Subsequently, in order to improve the aqueous solubility of P13I for both in vitro and in vivo evaluations, Rao et al. further optimized the E3 ligase ligand of P13I with lenalidomide and to obtain a new degrader L18I (Sievers et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019). L18I exhibited good solubility in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and inhibit C481S BTK in DLBCL tumors growth in vivo. These efforts suggest that PROTACs may provide a new treatment strategy for ibrutinib-resistant tumors.

FIGURE 4.

Design and optimization of BTK PROTACs.

Unlike the usually used ibrutinib-based BTK PROTACs (In this section we only discuss the reversible non-covalent BTK PROTACs), Crews et al. reported another non-covalent analog of ibrutinib, and developed a novel CRBN-recruiting BTK PROTAC, MT-802 (Figure 4), which induced the efficient degradation of both wild-type (DC50 = 14.6 nM) and C481S mutation (DC50 = 14.9 nM) BTK (Buhimschi et al., 2018). Meanwhile, they found that the degradation efficiency of VHL-recruited BTK PROTAC degrader SJF678 was significantly weaker than that of CRBN-recruited BTK PROTACs. They then developed a BTK degrader 49 based on the E3 ligand of ARV-110 with DC50 value less than 10 nM treated in RAMOS cell lines for 6 h. Nurix Therapeutics discovered two BTK degraders, NX-2127 and NX-5948, currently in Phase I clinical trials and their structures have not been disclosed. In recent years, they have disclosed oral PROTAC degraders 50 and 51 with good activities both in vitro and in vivo, as well as oral bioavailability (Robbins et al., 2020; Sands et al., 2020). The druggability of BTK degraders was significantly improved after modifying the linker to make it more rigid and reducing the molecular weight of the E3 ligand.

2.4 E3 ligase ligands optimization of IRAK4 PROTACs

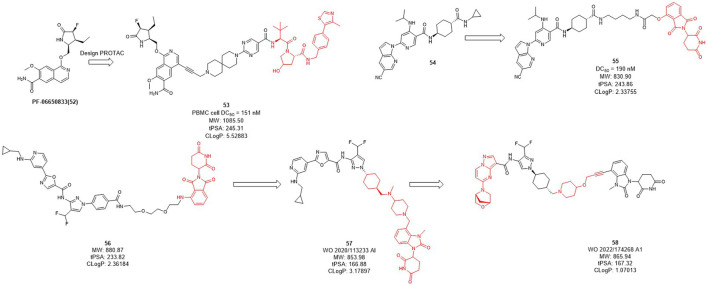

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) is a serine/threonine kinase that not only performs phosphorylation but also functions as a scaffold role in Toll-like receptor (TLR) and interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) signaling pathways (Brzezinska et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2013; Vollmer et al., 2017). As a promising therapeutic target for diffusing large B-cell lymphoma driven by the MYD88 L265P mutant, the IRAK4 target receives significant attention. While Previous inhibitors had only moderate effects on IRAK4 target because they inhibited kinase function but had no effect on scaffold function. Unlike traditional small molecule inhibitors, which only inhibit kinase activity, PROTACs for protein degradation may offer a solution to block both IRAK4 kinase activity and scaffold capabilities. In 2019, Anderson et al. selected PF-06650833 as IRAK4 inhibitor and synthesized a series of compounds based on VHL, CRBN, and IAP ligands. Among them, only the degrader 53 (Figure 5) based on VHL showed degradation activity of IRAK, with the DC50 value of 151 nM in PBMC cell (Nunes et al., 2019). In 2020, Dai et al. designed and synthesized a series of CRBN-based IRAK4 degraders and compound 55 showed DC50 value of 190 nM in vitro (Zhang et al., 2020). However, its degradation activity may be weaker than that of inhibitors 54. It may be due to the weak affinity between the inhibitor and the target protein, and replacing the E3 ligand will not obtain the desired potency.

FIGURE 5.

Design and optimization of IRAK4 PROTACs.

Kymera has two IRAK4 degraders, KT-474 and KT-413 in phase I clinical trial while their structures are undisclosed (Kymera, 2022). From their published patent (WO 2020/113233 Al), they obtained a series of IRAK4 degraders based on CRBN in combination with different IRAK4 inhibitors, most of which such as compound 56 (Figure 5) showed more than 50% degradation of IRAK4 at 0.01 nM in PMBC cells (Kargbo, 2019) (e.g., compound 57). Subsequently, the E3 ligase ligand part of 56 was replaced with the CRBN ligand, and the linker-optimized degrader 57 also showed DC50 less than 0.01 nM in PMBC cells (Mainolfi et al., 2020). Recently, they disclosed the structure of compound 58 which is also based on CRBN ligand and showed excellent in vitro and in vivo activity, as well as oral bioavailability (Gollob et al., 2022).

2.5 E3 ligase ligands optimization of TRK PROTACs

The tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) receptor family comprises three members: TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC that are encoded by the NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 genes, respectively, which plays an important role in regulating cell differentiation, proliferation, pain, and survival (Pulciani et al., 1982; Martin-Zanca et al., 1986; Klein et al., 1989). TRKs are tyrosine kinases receptors and their main implication is the development and function of neuronal tissues (Kargbo, 2020). Although the targeted treatment of TRK1 and TRK2 shows an overall good safety profile in the clinic trials, this strategy could also be improved because currently available pan-TRK kinase inhibitors may induce off-target adverse effects by modulating TRK family members present in the CNS. Currently, moderate off-target adverse effects have been observed, such as dizziness/ataxia, paresthesia, and weight gain (Drilon, 2019). Non-specific side effects and drug resistance to TRK kinase inhibitors remain great challenges for effective treatment (Kargbo, 2020). In contrast, PROTACs technology keep the target protein in the periphery without penetrating the blood-brain barrier, thus avoid the side effects of off-targeting to the CNS.

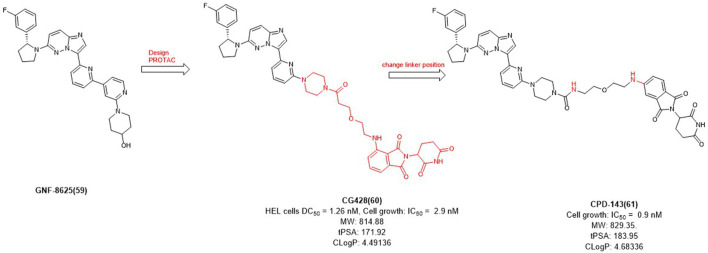

In 2020, Cullgen et al. selected GNF-8625 (Figure 6) as TRK inhibitor and linked with CRBN to obtain a series of TRK degraders and CG428 proved to be the most promising degrader. It demonstrated that CG428 can induce the degradation of wild-type TRKA in HEL cells with DC50 value of 1.26 nM and also inhibit cell growth with IC50 value of 2.9 nM (Chen et al., 2020). They then changed the connect position of pomalidomide with linker and obtained compound CPD-143 with an increased activity which the cell growth IC50 was 0.9 nM (Kargbo, 2020). It can be seen that when optimizing PROTACs, once the POI and E3 ligands were identified, changing the linker position on the E3 ligase ligand could be considered to improve the potency of PROTACs.

FIGURE 6.

Design and optimization of TRK PROTACs.

2.6 E3 ligase ligands optimization of BRD9 PROTACs

The BRD9 (bromodomain-containing protein 9) has gained special attention as a component of the human ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling BAF (BRG1/BRM-associated factor) complex (also known as mammalian SWI/SNF (SWItch Sucrose Non-Fermentable)) (Kadoch et al., 2013; Theodoulou et al., 2016). Studies have shown that BRD9 is preferentially used by cancers harboring SMARCB1 abnormalities, such as malignant rhabdoid tumors and several specific types of sarcomas (Kim et al., 2014). BRD9-containing complexes bind to active promoters and enhancers where they contribute to gene expression (Gatchalian et al., 2018). Loss of BRD9 leads to changes in gene expression related to apoptosis regulation, translation and development regulation. BRD9 is essential for the proliferation of SMARCB1-deficient cancer cell lines and is therefore a therapeutic target for these lethal cancers, and it is also a key target for causing acute myeloid leukemia (Hohmann et al., 2016; Michel et al., 2018). Despite the early discovery of BRD9 inhibitors, there is limited understanding of the function of BRD9 beyond acetyl lysine recognition based on early chemical probes.

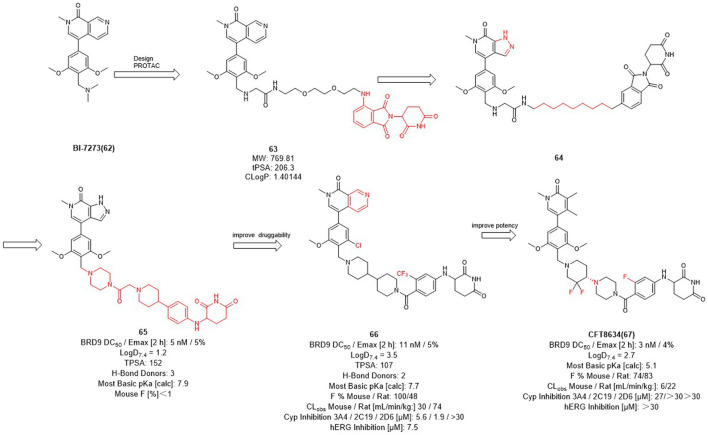

Therefore, Bradner et al. designed the first BRD9 degrader 63 in 2017 to provide a tool compound (Figure 7) (Remillard et al., 2017). Compound 63 was designed by using BI-7273 as inhibitor of BRD9 and CRBN ligand pomalidomide as E3 ligase ligand, it turned out to be valuable for exploring the biological and therapeutic potential of degrading BRD9. C4 Therapeutics (C4T) started with 64 and optimized both BRD9 inhibitors and E3 ligands and finally obtained the tool degrader 65 with DC50 value of 5 nM.

FIGURE 7.

Design and optimization of BRD9 PROTACs.

Compound 66 was optimized based on the structure of compound 65 with fewer hydrogen bond donors and its bioavailability (F %) in mice was increased to 100%, thus improving the druggability of the degrader. Subsequently, they made minor modifications of the POI and linker of compound 65, more importantly, for the E3 ligase ligand part, they replaced the F to trifluoromethyl group of the pomalidomide to obtain the degrader CFT8634 with high oral bioavailability (Jackson et al., 2022). Finally, Food and drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation (ODD) to CFT8634 (Figure 7) for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma which is an orally bioavailable, selective degrader of BRD9 (DC50 = 3 nM) (Sabnis, 2021). In summary, the optimization process from 64 to CFT8634 indicates that the dramatic change in their E3 ligands fraction improves their treatment potential.

2.7 E3 ligase ligands optimization of EGFR L858R PROTACs

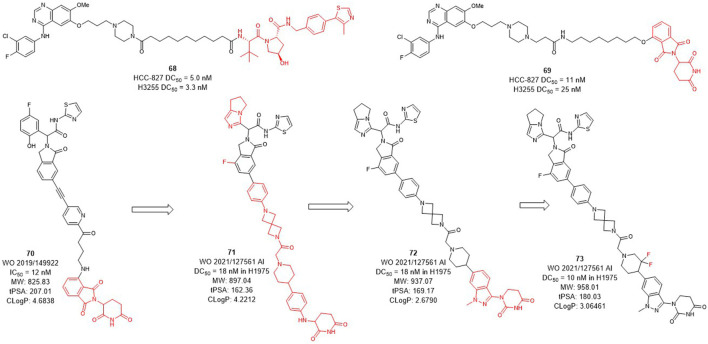

Several epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been developed and approved by the FDA for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer, but their efficacy may be compromised by drug resistance in EGFR-mutant variants (Sharma et al., 2007; Hirsch et al., 2017). Activating mutations, mainly in-frame deletions in exon 19 and L858R mutations, the former occurring in the αC-helix domain and the latter in the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding domain of the EGFR kinase. The EGFR L858R variant leads to poor prognosis and high incidence of malignant pleural effusion in non-small cell lung cancer, and the current small molecule drugs are only moderately effective against this variant (Kohno et al., 2021; Matsui et al., 2021). The development of EGFR L858R degraders based on PROTACs technology has become a new strategy. In 2020, Jin et al. designed and synthesized EGFR degraders with gefitinib and VHL or CRBN-recruited E3 ligands. The DC50 values of VHL-based degrader 68 (Figure 8) were 5.0 nM in HCC-827 cells and 3.3 nM in H3255 cells. The DC50 values of compound 69 which was based on CRBN ligand were 11 nM and 25 nM, respectively. In addition, they also showed good plasma exposure in mice.

FIGURE 8.

Design and optimization of EGFR L858R PROTACs.

C4T discovered the CRBN-based EGFR L858R degrader 70 (Figure 8) with an IC50 (BaF3 EGFR T790M/L858R/C797S degradation) value of 12 nM (Duplessis et al., 2019). After the optimization of the linker and the CRBN ligand, compounds 71 and 72 were subsequently synthesized, both showed a DC50 value of 18 nM in H1975 cells. Based on the structure of 72, compound 73 was further identified, which improved the DC50 value to 10 nM in H1975 cells. C4T replaced the lenalidomide ligand with a new CRBN-based derivative ligand, resulted in a better activity of compound 73 than compound 70 on the basis of structural optimization (Nasveschuk et al., 2021).

2.8 E3 ligase ligands optimization of BCL-XL PROTACs

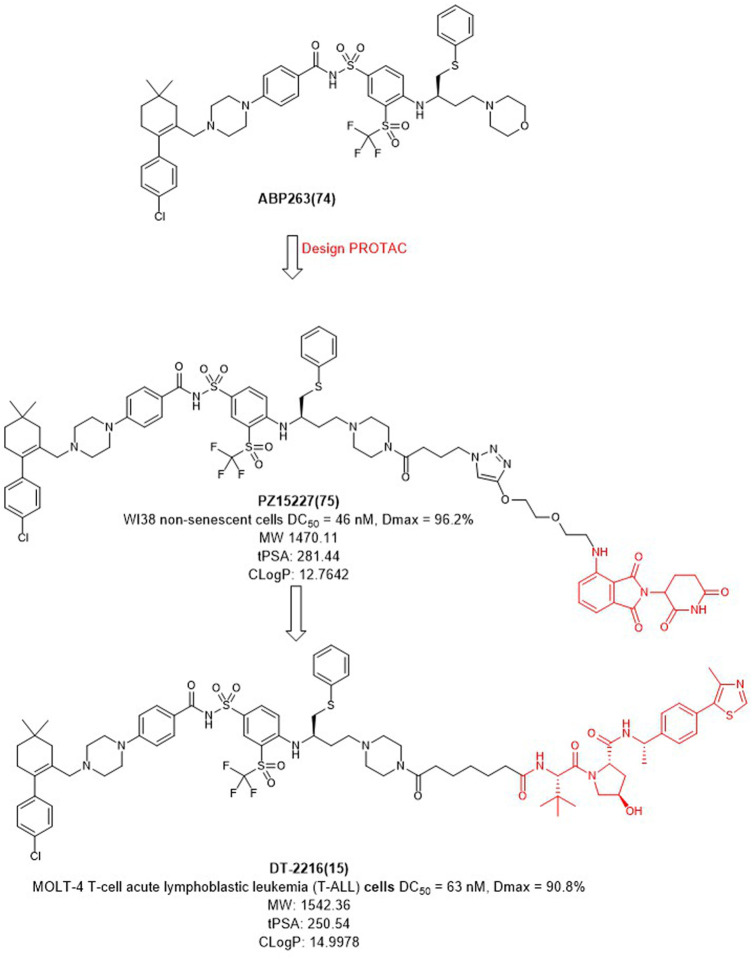

BCL-XL belongs to the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 protein family and plays a key role in determining cell life and death by regulating the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Czabotar et al., 2014). The anti-apoptotic function of BCL-XL protects cancer cells and induces drug resistance, which also promotes tumor progression (Igney et al., 2002). Inhibition of BCL-XL has been of great interest as a potential cancer therapeutic strategy. However, traditional BCL-XL inhibitors, such as ABT263 (Figure 9), exhibit targeted and dose-limited platelet toxicity (Zhang et al., 2019). Since the tissue distribution studies of VHL and CRBN have shown that its expression in platelets is minimal, degraders of BCL-XL could be developed through PROTAC technology.

FIGURE 9.

Design and optimization of BCL-XL PROTACs.

In 2019, Zheng et al. selected ABT263 (Figure 9) as BCL-XL inhibitor connected with CRBN to obtain the degrader PZ15227 with DC50 value of 46 nM and Dmax of 96.2% in WI38 non-senescent cells (NCs) (He et al., 2020). Compared with ABT263, PZ15227 showed reduced toxicity to platelets but remained toxicity against senescent cells because CRBN was less expressed in platelets. Subsequently, they found that CRBN-based PROTACs were highly potent against other cancer cell lines, but less potent in MOLT-4 cells, possibly due to the low expression of CRBN (Zhang et al., 2020).

In 2021, Zheng et al. discovered DT2216 (NCT04886622) as an effective BCL-XL degrader based on VHL E3 ligase with a DC50 value of 63 nM and Dmax of 90.8% in MOLT-4 cells. Compared with ABT263 (EC50 = 0.191 μM, half max effective concentration) and DT2216 (EC50 = 0.052 μM), the latter showed increased cytotoxicity to MOLT-4 cells. More importantly, DT2216 exerted almost no effect on the viability of platelets up to a concentration of 3 μM which showed better effect than PZ15227. DT2216 was found to have enhanced efficacy against a variety of BCL-XL-dependent leukemia cell lines and exhibited much less toxic to platelets than ABT263 (Khan et al., 2019). Therefore, DT2216 was approved by FDA to enter phase I clinical trials for the treatment of advanced liquid and solid tumors. These findings demonstrated the potential of using PROTAC to reduce the toxicity of targeted drugs.

2.9 E3 ligase ligands optimization of STAT3 PROTACs

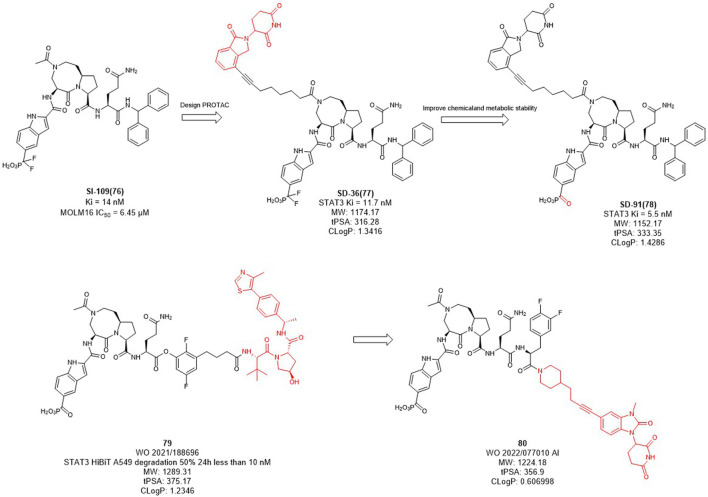

In mammalian cells, the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is an essential component of the seven members of the STAT family (STAT1, 2, 3, 4, 5a, 5b, 6). STAT3 is widely expressed in a variety of cells and tissues and activates the expression of downstream genes in response to various cytokines, growth factors and other signals (Yu et al., 2009). Under normal physiological conditions, STAT3 activation is rapid and transient, mainly due to the presence of negative regulators in cells. However, STAT3 is continuously activated and expressed at high levels in tumor cells. Overexpression of STAT3 is strongly associated with cancer cell survival, proliferation, invasion, metastasis, drug resistance, and immune evasion, among other related genes. Since STAT3 dysregulation contributes to many human cancers and other human diseases (Wang et al., 2018). Inhibition or downregulation of STAT3 expression has become a main strategy for cancer therapy. However, to date, no drugs based on STAT3 targets have been approved in the market. Wang et al. designed several STAT3 degraders based on SI-109 (Figure 10) and lenalidomide, and discovered that degrader SD-36 exhibited good degradation activity (Zhou et al., 2019). In the subsequent studies, they converted the difluoro methylene group of SD-36 to a ketone group to obtain degrader SD-91 with improved potency both in vitro and in vivo (Zhou et al., 2021). Kymera Therapeutics chose the similar inhibitor, SI-109 (Figure 10), but changed the linker attachment site and synthesized a series of degraders based on VHL ligand or CRBN ligand derivatives (Yang et al., 2022). From their disclosed data, the degradation activity of VHL-based degraders was generally better than that of CRBN-based derivatives. However, their recent patent selected CRBN-based ligands for further optimization may due to the large molecular of VHL ligand. It is hypothesized that reducing the molecular weight and the hydrogen bond receptors of E3 ligands may be the trend for PROTACs to be more druggable.

FIGURE 10.

Design and optimization of STAT3 PROTACs.

3 Conclusions and perspectives

Since PROTAC technology was first identified as a clinical therapeutic strategy, both academia and industry have shown great interest in PROTACs technology. However, PROTACs degraders have relatively more complex chemical structures and biological mechanisms than traditional small molecule drugs, which require efforts in the fields of organic synthetic chemistry and medicinal chemistry.

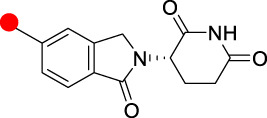

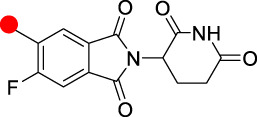

Although PROTACs technology has shown many advantages over traditional small molecule drugs for antitumor therapy, unlike traditional small molecule drugs, they are mostly regarded as “beyond rule-of-five”. PROTACs molecules have more hydrogen bond donors and acceptors and larger molecular weights, mostly around 1,000 Da. Therefore, the poor membrane permeability and low bioavailability of PROTACs molecules limit its clinical application. In the process of optimizing E3 ligase ligands by medicinal chemists, it is important to ensure a high affinity between the E3 ligase ligands and E3 ubiquitin ligases. The excessive molecular weight of E3 ligands leads to poor membrane permeability. Based on the suitable molecular weight size of CRBN ligand, ARV-110 and CFT8634 were rationally designed. In addition, they both introduced F in the aromatic ring of CRBN ligands, probably to improve their druggability. Most of the other CRBN ligands modifications are designed to improve the affinity with E3 ligases or to improve the druggability properties of these degraders in oral PROTACs.

Typically, the POIs based on agonists or antagonists of target proteins, as well as the traditional pharmacological optimization of these small molecules, have been studied in the design and optimization of PROTACs. The optimization of linkers tends to have more rigid structures. However, although more than 600 E3 ligases have been identified, the number of small molecule ligands available to design PROTAC molecules for E3 ligands is rather limited, and only CRBN-based PROTACs have been clinically achieved for oral application (Table 2).

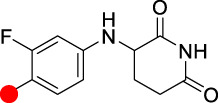

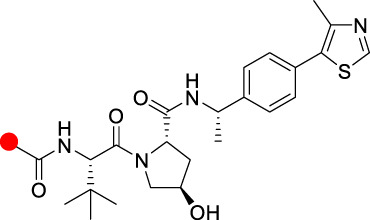

TABLE 2.

Summary of the chemical properties of E3 ligase ligands in clinical trials.

| E3 ligase ligand | E3 ligase | MW | ROA | tPSA | cLog P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CRBN | 244.08 | Oral | 66.48 | 0.305 |

|

CRBN | 276.05 | Oral | 83.55 | 0.747 |

|

CRBN | 222.08 | Oral | 58.2 | 1.184 |

|

VHL | 486.23 | I.v | 111.1 | 2.343 |

Red spot: Linking site.

It is believed that advances in artificial intelligence techniques (protein structure prediction), virtual drug screening, and other technologies will facilitate the discovery of E3 ligands and provide more tools for PROTAC design. These advances will greatly facilitate the transition of PROTACs degraders from being considered as tool molecules to small molecule clinical drug candidates.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Highlevel new R&D institute (2019B090904008), and High-level Innovative Research Institute (2021B0909050003) from Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province.

Author contributions

Concept, writing, review, and revision of the manuscript: MW, S-XG, HJ, and HX; all authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Arnal J. F., Lenfant F., Metivier R., Flouriot G., Henrion D., Adlanmerini M., et al. (2017). Membrane and nuclear estrogen receptor alpha actions: From tissue specificity to medical implications. Physiol. Rev. 97, 1045–1087. 10.1152/physrev.00024.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés M., Langley D. R., Crews C. M. (2022). PROTAC targeted protein degraders: The past is prologue. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 181–200. 10.1038/s41573-021-00371-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinska A. A., Johnson J. L., Munafo D. B., Ellis B. A., Catz S. D. (2009). Signalling mechanisms for toll-like receptor-activated neutrophil exocytosis: Key roles for interleukin-1-receptor-associated kinase-4 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but not toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-beta (TRIF). Immunology 127, 386–397. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02980.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhimschi A. D., Armstrong H. A., Toure M., Jaime-Figueroa S., Chen T. L., Lehman A. M., et al. (2018). Targeting the C481S ibrutinib-resistance mutation in bruton's tyrosine kinase using PROTAC-mediated degradation. Biochemistry 57, 3564–3575. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen Y., Zhang C., Jiao B., Liang S., Tan Q., et al. (2020). Discovery of first-in-class potent and selective tropomyosin receptor kinase degraders. J. Med. Chem. 63, 14562–14575. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscitiello C., Guerini-Rocco E., Viale G., Fumagalli C., Sajjadi E., Venetis K., et al. (2022). Immunotherapy in breast cancer patients: A focus on the use of the currently available biomarkers in oncology. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 22, 787–800. 10.2174/1871520621666210706144112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar P. E., Lessene G., Strasser A., Adams J. M. (2014). Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: Implications for physiology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 49–63. 10.1038/nrm3722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R. E., Ngo V. N., Lenz G., Tolar P., Young R. M., Romesser P. B., et al. (2010). Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature 463, 88–92. 10.1038/nature08638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bono J., Mateo J., Fizazi K., Saad F., Shore N., Sandhu S., et al. (2020). Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 2091–2102. 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drilon A. (2019). TRK inhibitors in TRK fusion-positive cancers. Ann. Oncol. 30, viii23–viii30. viii23-viii30. 10.1093/annonc/mdz282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplessis M., Jaeschke G., Kuhn B., Lazarski K., Liang Y. N., Alice Yvonne, et al. (2019). Preparation of substituted isoindoline compounds which cause degradation of EGFR and are useful as anticancer agents. U.S. patent NO WO2019149922. Watertown: United States Patent Application Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Qian Y., He W., Liu K. (2021). Bicyclic imide derivative, preparation method thereof, and application thereof in medicine. CN patent NO WO 2021/143822 Al. Shanghai: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Iii H. a. B., Vuky J., Dreicer R., Sartor A. O., Sternberg C. N., et al. (2022). Phase 1/2 study of ARV-110, an androgen receptor (AR) PROTAC degrader, in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 17. 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.6_suppl.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatchalian J., Malik S., Ho J., Lee D. S., Kelso T. W. R., Shokhirev M. N., et al. (2018). A non-canonical BRD9-containing BAF chromatin remodeling complex regulates naive pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 5139. 10.1038/s41467-018-07528-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollob J., Davis J., Mcdonald A., Rong H. (2022). Irak4 degraders and uses thereof. U.S. patent NO WO 2022/174268 Al. Watertown: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez T. L., Hancock M., Sun S., Gersch C. L., Larios J. M., David W., et al. (2020). Targeted degradation of activating estrogen receptor alpha ligand-binding domain mutations in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 180, 611–622. 10.1007/s10549-020-05564-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T., Goralski M., Gaskill N., Capota E., Kim J., Ting T. C., et al. (2017). Anticancer sulfonamides target splicing by inducing RBM39 degradation via recruitment to DCAF15. Science 356, eaal3755. 10.1126/science.aal3755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Wang C., Qin C., Xiang W., Fernandez-Salas E., Yang C.-Y., et al. (2019a). Discovery of ARD-69 as a highly potent proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) degrader of androgen receptor (AR) for the treatment of prostate cancer. J. Med. Chem. 62, 941–964. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Zhao L., Xiang W., Qin C., Miao B., Mceachern D., et al. (2021). Strategies toward discovery of potent and orally bioavailable proteolysis targeting chimera degraders of androgen receptor for the treatment of prostate cancer. J. Med. Chem. 64, 12831–12854. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Zhao L., Xiang W., Qin C., Miao B., Xu T., et al. (2019b). Discovery of highly potent and efficient PROTAC degraders of androgen receptor (AR) by employing weak binding affinity VHL E3 ligase ligands. J. Med. Chem. 62, 11218–11231. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Zhang X., Chang J., Kim H. N., Zhang P., Wang Y., et al. (2020). Using proteolysis-targeting chimera technology to reduce navitoclax platelet toxicity and improve its senolytic activity. Nat. Commun. 11, 1996. 10.1038/s41467-020-15838-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning N. J., Manford A. G., Spradlin J. N., Brittain S. M., Zhang E., Mckenna J. M., et al. (2022). Discovery of a covalent FEM1B recruiter for targeted protein degradation applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 701–708. 10.1021/jacs.1c03980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1992). The ubiquitin system for protein degradation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61, 761–807. 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Heller H., Elias S., Ciechanover A. (1983). Components of ubiquitin-protein ligase system. Resolution, affinity purification, and role in protein breakdown. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 8206–8214. 10.1016/s0021-9258(20)82050-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch F. R., Scagliotti G. V., Mulshine J. L., Kwon R., Curran W. J., Wu Y.-L., et al. (2017). Lung cancer: Current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet 389, 299–311. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30958-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann A. F., Martin L. J., Minder J. L., Roe J. S., Shi J., Steurer S., et al. (2016). Sensitivity and engineered resistance of myeloid leukemia cells to BRD9 inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 672–679. 10.1038/nchembio.2115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R., Tanaka H., Yasuda H. (1997). Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 420, 25–27. 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Hu B., Wang M., Xu F., Miao B., Yang C. Y., et al. (2019). Discovery of ERD-308 as a highly potent proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) degrader of estrogen receptor (ER). J. Med. Chem. 62, 1420–1442. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Omoto Y., Iwase H., Yamashita H., Toyama T., Coombes R. C., et al. (2014). Differential expression of estrogen receptor α, β1, and β2 in lobular and ductal breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 1933–1938. 10.1073/pnas.1323719111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igney F. H., Krammer P. H. (2002). Death and anti-death: Tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 277–288. 10.1038/nrc776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y., Ishikawa M., Kitaguchi R., Sato S., Naito M., Hashimoto Y. (2011). Development of target protein-selective degradation inducer for protein knockdown. Bioorg Med. Chem. 19, 3229–3241. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.03.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M., Kondo K., Yang H., Kim W., Valiando J., Ohh M., et al. (2001). HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O 2 sensing. Science 292, 464–468. 10.1126/science.1059817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P., Mole D. R., Tian Y. M., Wilson M. I., Gielbert J., Gaskell S. J., et al. (2001). Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292, 468–472. 10.1126/science.1059796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. L., Agafonov R. V., Carlson M. W., Chaturvedi P., Cocozziello D., Cole K., et al. (2022). Abstract ND09: The discovery and characterization of CFT8634: A potent and selective degrader of BRD9 for the treatment of SMARCB1-perturbed cancers. Cancer Res. 82, ND09. 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2022-nd09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoch C., Hargreaves D. C., Hodges C., Elias L., Ho L., Ranish J., et al. (2013). Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nat. Genet. 45, 592–601. 10.1038/ng.2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargbo R. B. (2020). PROTAC compounds targeting TRK for use in cancer therapeutics. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 1090–1091. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargbo R. B. (2019). PROTAC degradation of IRAK4 for the treatment of neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 1251–1252. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahata I., Fukunaga K. (2020). Degradation of tyrosine hydroxylase by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease and dopa-responsive dystonia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3779. 10.3390/ijms21113779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S., Zhang X., Lv D., Zhang Q., He Y., Zhang P., et al. (2019). A selective BCL-XL PROTAC degrader achieves safe and potent antitumor activity. Nat. Med. 25, 1938–1947. 10.1038/s41591-019-0668-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. H., Roberts C. W. (2014). Mechanisms by which SMARCB1 loss drives rhabdoid tumor growth. Cancer Genet. 207, 365–372. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Parada L. F., Coulier F., Barbacid M. (1989). trkB, a novel tyrosine protein kinase receptor expressed during mouse neural development. EMBO J. 8, 3701–3709. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08545.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T., Matsui T., Enatsu S. (2021). Differences between EGFR exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R point mutation, frequently detected EGFR mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, from a molecular biology viewpoint. Gan Kagaku Ryoho 48, 1463–1467. 10.1038/srep31636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D., Rape M. (2012). The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregel S., Wang C., Han X., Xiao L., Fernandez-Salas E., Bawa P., et al. (2020). Androgen receptor degraders overcome common resistance mechanisms developed during prostate cancer treatment. Neoplasia 22, 111–119. 10.1016/j.neo.2019.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Sabapathy K. (2019). RNF4-A paradigm for SUMOylation-mediated ubiquitination. Proteomics 19, e1900185. 10.1002/pmic.201900185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kymera (2022). https://investors.kymeratx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/kymera-announces-positive-results-phase-1-clinical-trial (Accessed Dec 14, 2022).

- Kymera (2022). https://investors.kymeratx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/kymera-therapeutics-doses-first-patients-phase-1-oncology-trials (Accessed Jun 15, 2022).

- Lim K. H., Staudt L. M. (2013). Toll-like receptor signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a011247. 10.1101/cshperspect.a011247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Yan M., Lv H., Wang B., Lv X., Zhang H., et al. (2020). Macrophage K63-linked ubiquitination of YAP promotes its nuclear localization and exacerbates atherosclerosis. Cell Rep. 32, 107990. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Spradlin J. N., Boike L., Tong B., Brittain S. M., Mckenna J. M., et al. (2021). Chemoproteomics-enabled discovery of covalent RNF114-based degraders that mimic natural product function. Cell Chem. Biol. 28, 559–566.e15. e515. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyle C., Richards S., Yasuda K., Napoleon M. A., Walker J., Arinze N., et al. (2019). c-Cbl targets PD-1 in immune cells for proteasomal degradation and modulates colorectal tumor growth. Sci. Rep. 9, 20257. 10.1038/s41598-019-56208-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainolfi N., Ji N., Kluge A. F., Weiss M. M., Zhang Y., Zheng X. (2020). Preparation of bifunctional compounds as IRAK degraders and uses thereof. U.S. patent NO WO 2020/113233 Al. Cambridge: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Zanca D., Hughes S. H., Barbacid M. (1986). A human oncogene formed by the fusion of truncated tropomyosin and protein tyrosine kinase sequences. Nature 319, 743–748. 10.1038/319743a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Tanizawa Y., Enatsu S. (2021). [Exon 19 Deletion and Exon 21 L858R Point Mutation in EGFR Mutation—Positive Non—Small Cell Lung Cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 48 (5), 673–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel B. C., D'avino A. R., Cassel S. H., Mashtalir N., Mckenzie Z. M., Mcbride M. J., et al. (2018). A non-canonical SWI/SNF complex is a synthetic lethal target in cancers driven by BAF complex perturbation. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1410–1420. 10.1038/s41556-018-0221-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullard A. (2019). First targeted protein degrader hits the clinic. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21 10.1038/d41573-019-00043-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasveschuk C. G., Duplessis M., Ahn J. Y., Hird A. W., Michael R. E., Lazarski K., et al. (2021). Preparation of isoindolinone and indazole compounds for the degradation of EGFR. U.S. patent NO WO2021127561 A1. Watertown: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Neklesa T., Snyder L. B., Willard R. R., Vitale N., Pizzano J., Gordon D. A., et al. (2019). ARV-110: An oral androgen receptor PROTAC degrader for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 259. 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.7_suppl.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neklesa T., Snyder L. B., Willard R. R., Vitale N., Raina K., Pizzano J., et al. (2018). Abstract 5236: ARV-110: An androgen receptor PROTAC degrader for prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 78, 5236. 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2018-5236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes J., Mcgonagle G. A., Eden J., Kiritharan G., Touzet M., Lewell X., et al. (2019). Targeting IRAK4 for degradation with PROTACs. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 1081–1085. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N., Morita Y., Nagai K., Shimokawa K., Ujikawa O., Fujimori I., et al. (2018). Derivatization of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) ligands yields improved inducers of estrogen receptor α degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 6776–6790. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N., Okuhira K., Ito M., Nagai K., Shibata N., Hattori T., et al. (2017). In vivo knockdown of pathogenic proteins via specific and nongenetic inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP)-dependent protein erasers (SNIPERs). J. Biol. Chem. 292, 4556–4570. 10.1074/jbc.M116.768853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N., Tsuji G., Shoda T., Fujisato T., Kurihara M., Demizu Y., et al. (2019). Development of small molecule chimeras that recruit AhR E3 ligase to target proteins. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 2822–2832. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake F., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kato S. (2007). Transcription factor AhR is a ligand-dependcnt E3 ubiquitin ligase. Tanpakushitsu kakusan Koso. Protein, nucleic Acid. enzyme 52, 1973–1979. 10.1038/nature05683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva S. L., Crews C. M. (2019). Targeted protein degradation: Elements of PROTAC design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 50, 111–119. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z., Scheerens H., Li S. J., Schultz B. E., Sprengeler P. A., Burrill L. C., et al. (2007). Discovery of selective irreversible inhibitors for Bruton's tyrosine kinase. ChemMedChem 2, 58–61. 10.1002/cmdc.200600221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J., Xiao Y., Liu X., Hu W., Sobh A., Yuan Y., et al. (2022). Identification of Piperlongumine (PL) as a new E3 ligase ligand to induce targeted protein degradation. bioRxiv.12 10.1101/2022.01.21.474712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl C., Dikic I. (2019). Cellular quality control by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Science 366, 818–822. 10.1126/science.aax3769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulciani S., Santos E., Lauver A. V., Long L. K., Aaronson S. A., Barbacid M. (1982). Oncogenes in solid human tumours. Nature 300, 539–542. 10.1038/300539a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebello R. J., Oing C., Knudsen K. E., Loeb S., Johnson D. C., Reiter R. E., et al. (2021). Prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 7, 9. 10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard D., Buckley D. L., Paulk J., Brien G. L., Sonnett M., Seo H.-S., et al. (2017). Degradation of the BAF complex factor BRD9 by heterobifunctional ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5738–5743. 10.1002/anie.201611281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins D. W., Sands A. T., Mcintosh J., Mihalic J., Wu J., Kato D., et al. (2020). Bifunctional compounds for degrading BTK via ubiquitin proteolytic pathway and their preparation. U.S. patent NO WO2020081450 A1. San Francisco: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez A., Cyrus K., Salcius M., Kim K., Crews C. M., Deshaies R. J., et al. (2008). Targeting steroid hormone receptors for ubiquitination and degradation in breast and prostate cancer. Oncogene 27, 7201–7211. 10.1038/onc.2008.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadatzadeh M. R., Elmi A. N., Pandya P. H., Bijangi-Vishehsaraei K., Ding J., Stamatkin C. W., et al. (2017). The role of MDM2 in promoting genome stability versus instability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2216. 10.3390/ijms18102216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabnis R. W. (2021). BRD9 bifunctional degraders for treating cancer. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 1879–1880. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K. M., Kim K. B., Kumagai A., Mercurio F., Crews C. M., Deshaies R. J. (2001). Protacs: Chimeric molecules that target proteins to the skp1-cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 8554–8559. 10.1073/pnas.141230798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands A. T., Kelly A. (2020). Bifunctional compounds for degrading btk via ubiquitin proteosome pathway. U.S. patent NO WO2021113557. San Francisco: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Sato S., Aoyama H., Miyachi H., Naito M., Hashimoto Y. (2008). Demonstration of direct binding of cIAP1 degradation-promoting bestatin analogs to BIR3 domain: Synthesis and application of fluorescent bestatin ester analogs. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 3354–3358. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira M., Calabrese M. F., Bullock A. N., Crews C. M. (2019). Targeted protein degradation: Expanding the toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 949–963. 10.1038/s41573-019-0047-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth A. R., Pucheault M., Tae H. S., Crews C. M. (2008). Targeted intracellular protein degradation induced by a small molecule: En route to chemical proteomics. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 5904–5908. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth J. S., Jr., Fonseca F. N., Koldobskiy M., Mandal A., Deshaies R., Sakamoto K., et al. (2004a). Chemical genetic control of protein levels: Selective in vivo targeted degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 3748–3754. 10.1021/ja039025z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth J. S., Jr., Fonseca F. N., Koldobskiy M., Mandal A., Deshaies R., Sakamoto K., et al. (2004b). Chemical genetic control of protein levels: Selective in vivo targeted degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 3748–3754. 10.1021/ja039025z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman B. A., Harper J. W. (2009). Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: The apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 319–331. 10.1038/nrm2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. V., Bell D. W., Settleman J., Haber D. A. (2007). Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 169–181. 10.1038/nrc2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers Q. L., Petzold G., Bunker R. D., Renneville A., Słabicki M., Liddicoat B. J., et al. (2018). Defining the human C2H2 zinc finger degrome targeted by thalidomide analogs through CRBN. Science 362, eaat0572. 10.1126/science.aat0572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder L. B., Flanagan J. J., Qian Y., Gough S. M., Andreoli M., Bookbinder M., et al. (2021a). Abstract 44: The discovery of ARV-471, an orally bioavailable estrogen receptor degrading PROTAC for the treatment of patients with breast cancer. Cancer Res. 81, 44. 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2021-44 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder L. B., Neklesa T. K., Chen X., Dong H., Ferraro C., Gordon D. A., et al. (2021b). Abstract 43: Discovery of ARV-110, a first in class androgen receptor degrading PROTAC for the treatment of men with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 81, 43. 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2021-43 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Gao H., Yang Y., He M., Wu Y., Song Y., et al. (2019). PROTACs: Great opportunities for academia and industry. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 4, 64. 10.1038/s41392-019-0101-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Ding N., Song Y., Yang Z., Liu W., Zhu J., et al. (2019). Degradation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase mutants by PROTACs for potential treatment of ibrutinib-resistant non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Leukemia 33, 2105–2110. 10.1038/s41375-019-0440-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Zhao X., Ding N., Gao H., Wu Y., Yang Y., et al. (2018). PROTAC-induced BTK degradation as a novel therapy for mutated BTK C481S induced ibrutinib-resistant B-cell malignancies. Cell Res. 28, 779–781. 10.1038/s41422-018-0055-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo M. Y., Rathkopf D. E., Kantoff P. (2019). Treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 70, 479–499. 10.1146/annurev-med-051517-011947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoulou N. H., Bamborough P., Bannister A. J., Becher I., Bit R. A., Che K. H., et al. (2016). Discovery of I-BRD9, a selective cell active chemical probe for bromodomain containing protein 9 inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 59, 1425–1439. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong B., Luo M., Xie Y., Spradlin J. N., Tallarico J. A., Mckenna J. M., et al. (2020). Bardoxolone conjugation enables targeted protein degradation of BRD4. Sci. Rep. 10, 15543. 10.1038/s41598-020-72491-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer S., Strickson S., Zhang T., Gray N., Lee K. L., Rao V. R., et al. (2017). The mechanism of activation of IRAK1 and IRAK4 by interleukin-1 and Toll-like receptor agonists. Biochem. J. 474, 2027–2038. 10.1042/BCJ20170097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waks A. G., Winer E. P. (2019). Breast cancer treatment: A review. JAMA 321, 288–300. 10.1001/jama.2018.19323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Jiang X., Feng F., Liu W., Sun H. (2020). Degradation of proteins by PROTACs and other strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10, 207–238. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Shen Y., Wang S., Shen Q., Zhou X. (2018). The role of STAT3 in leading the crosstalk between human cancers and the immune system. Cancer Lett. 415, 117–128. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. C., Kleinman J. I., Brittain S. M., Lee P. S., Chung C. Y. S., Kim K., et al. (2019). Covalent ligand screening uncovers a RNF4 E3 ligase recruiter for targeted protein degradation applications. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 2430–2440. 10.1021/acschembio.8b01083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Meng F., Park K. S., Yim H., Velez J., Kumar P., et al. (2021). Harnessing the E3 ligase KEAP1 for targeted protein degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15073–15083. 10.1021/jacs.1c04841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G. E., Buckley D. L., Paulk J., Roberts J. M., Souza A., Dhe-Paganon S., et al. (2015). Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science 348, 1376–1381. 10.1126/science.aab1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woyach J. A., Furman R. R., Liu T. M., Ozer H. G., Zapatka M., Ruppert A. S., et al. (2014). Resistance mechanisms for the Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 2286–2294. 10.1056/NEJMoa1400029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang W., Zhao L., Han X., Qin C., Miao B., Mceachern D., et al. (2021). Discovery of ARD-2585 as an exceptionally potent and orally active PROTAC degrader of androgen receptor for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. J. Med. Chem. 64, 13487–13509. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Zheng X., Zhu X. (2022). Preparation of peptidomimetics as STAT degraders and their uses for treating diseases. CN. patent NO WO2022077010 A1. Watertown: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Jia M., He W., Chen G., He F., Tao W. (2021a). Bicyclic imide derivative, preparation method thereof, and application thereof in medicine. CN. patent NO WO 2021/143822 A1. Shanghai: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Zhao J., Chen D., Wang Y. (2021b). E3 ubiquitin ligases: Styles, structures and functions. Mol. Biomed. 2, 23. 10.1186/s43556-021-00043-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Rape M. (2009). Building ubiquitin chains: E2 enzymes at work. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 755–764. 10.1038/nrm2780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Pardoll D., Jove R. (2009). STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: A leading role for STAT3. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 798–809. 10.1038/nrc2734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Fu L., Shen B., Liu Y., Wang W., Cai X., et al. (2020a). Assessing IRAK4 functions in ABC DLBCL by IRAK4 kinase inhibition and protein degradation. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 1500–1509 e1513. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Crowley V. M., Wucherpfennig T. G., Dix M. M., Cravatt B. F. (2019a). Electrophilic PROTACs that degrade nuclear proteins by engaging DCAF16. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 737–746. 10.1038/s41589-019-0279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Luukkonen L. M., Eissler C. L., Crowley V. M., Yamashita Y., Schafroth M. A., et al. (2021). DCAF11 supports targeted protein degradation by electrophilic proteolysis-targeting chimeras. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5141–5149. 10.1021/jacs.1c00990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Thummuri D., He Y., Liu X., Zhang P., Zhou D., et al. (2019b). Utilizing PROTAC technology to address the on-target platelet toxicity associated with inhibition of BCL-XL. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 55, 14765–14768. 10.1039/c9cc07217a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Thummuri D., Liu X., Hu W., Zhang P., Khan S., et al. (2020b). Discovery of PROTAC BCL-XL degraders as potent anticancer agents with low on-target platelet toxicity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 192, 112186. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. T., Kang L. G., Ding L., Vranic S., Gatalica Z., Wang Z. Y. (2011). A positive feedback loop of ER-α36/EGFR promotes malignant growth of ER-negative breast cancer cells. Oncogene 30, 770–780. 10.1038/onc.2010.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Han X., Lu J., Mceachern D., Wang S. (2020). A highly potent PROTAC androgen receptor (AR) degrader ARD-61 effectively inhibits AR-positive breast cancer cell growth in vitro and tumor growth in vivo . Neoplasia 22, 522–532. 10.1016/j.neo.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N., Shabek N. (2017). Ubiquitin ligases: Structure, function, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 129–157. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Bai L., Xu R., Mceachern D., Chinnaswamy K., Li R., et al. (2021). SD-91 as A Potent and selective STAT3 degrader capable of achieving complete and long-lasting tumor regression. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 996–1004. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Bai L., Xu R., Zhao Y., Chen J., Mceachern D., et al. (2019). Structure-based discovery of SD-36 as a potent, selective, and efficacious PROTAC degrader of STAT3 protein. J. Med. Chem. 62, 11280–11300. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]