Abstract

The National Clinical Care Commission (NCCC) was established by Congress to make recommendations to leverage federal policies and programs to more effectively prevent and treat diabetes and its complications. The NCCC developed a guiding framework that incorporated elements of the Socioecological and Chronic Care Models. It surveyed federal agencies and conducted follow-up meetings with representatives from 10 health-related and 11 non–health-related federal agencies. It held 12 public meetings, solicited public comments, met with numerous interested parties and key informants, and performed comprehensive literature reviews. The final report, transmitted to Congress in January 2022, contained 39 specific recommendations, including 3 foundational recommendations that addressed the necessity of an all-of-government approach to diabetes, health equity, and access to health care. At the general population level, the NCCC recommended that the federal government adopt a health-in-all-policies approach so that the activities of non–health-related federal agencies that address agriculture, food, housing, transportation, commerce, and the environment be coordinated with those of health-related federal agencies to affirmatively address the social and environmental conditions that contribute to diabetes and its complications. For individuals at risk for type 2 diabetes, including those with prediabetes, the NCCC recommended that federal policies and programs be strengthened to increase awareness of prediabetes and the availability of, referral to, and insurance coverage for intensive lifestyle interventions for diabetes prevention and that data be assembled to seek approval of metformin for diabetes prevention. For people with diabetes and its complications, the NCCC recommended that barriers to proven effective treatments for diabetes and its complications be removed, the size and competence of the workforce to treat diabetes and its complications be increased, and new payment models be implemented to support access to lifesaving medications and proven effective treatments for diabetes and its complications. The NCCC also outlined an ambitious research agenda. The NCCC strongly encourages the public to support these recommendations and Congress to take swift action.

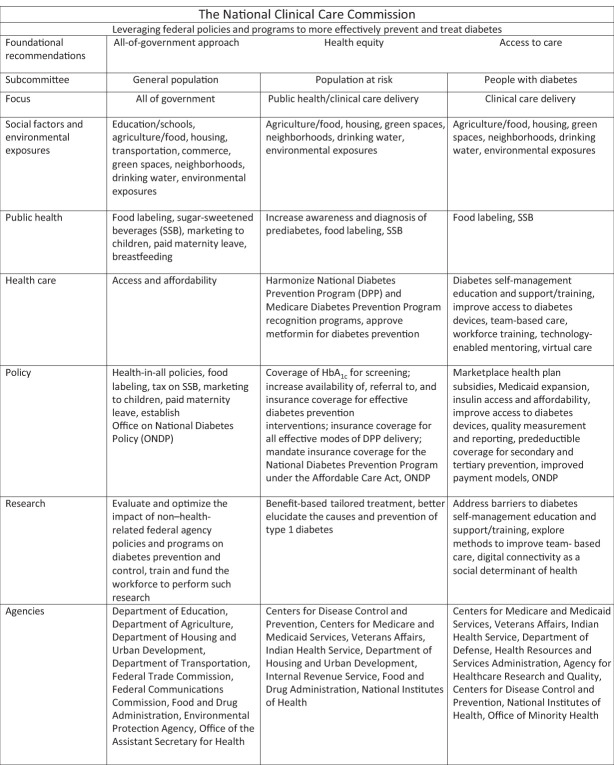

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Approximately 1.4 million Americans are diagnosed with diabetes each year, and 37.3 million Americans have diabetes (11.3% of the U.S. population). Of these, 28.7 million (77%) are diagnosed and 8.5 million (23%) are undiagnosed. In addition, 96 million Americans ≥18 years of age have prediabetes (38% of the adult population). Only 19% of adults with prediabetes report being told by a health professional that they have this condition (1).

Type 2 diabetes is more prevalent in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations and certain racial and ethnic groups. Differential exposure to unhealthy social and environmental conditions influences the risk of type 2 diabetes and susceptibility to complications, comorbidities, and death. Exposure to social and environmental conditions, including lower educational attainment, food insecurity, crowded living conditions, and unhealthy environments, tend to cluster in the same individuals, populations, and areas and drive diabetes disparities (2).

In the U.S., diabetes remains the leading cause of incident blindness among adults 18–64 years of age and is also the leading cause of incident end-stage kidney disease (1). In 2017, the total direct and indirect costs of diabetes in the U.S. were estimated to be $327 billion (3). In 2018, people with diabetes ≥18 years of age had 226,000 hospital admissions for hyperglycemic crisis, 60,000 admissions for hypoglycemia, 1,871,000 admissions for major cardiovascular disease, and 154,000 admissions for lower-extremity amputations. In 2019, diabetes was listed as the underlying cause of death on 87,647 death certificates and as an underlying or contributing cause of death for 282,801 Americans. Between 2015 and 2018, among U.S. adults ≥18 years of age with diagnosed diabetes, only 79% reported having at least one usual source of diabetes care and only about one-third (36%) met all four goals for moderate hemoglobin A1c control (<8%), blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg), non-HDL cholesterol (<160 mg/dL), and nonsmoker status (1). These data highlight the urgent need to both prevent diabetes and provide appropriate and timely care for all people with diabetes.

Background and Methods

It has been nearly 50 years since the National Commission on Diabetes issued The Long-Range Plan to Combat Diabetes (4). With encouragement from interested parties and action by the bipartisan Congressional Diabetes Caucus, the Congress passed the National Clinical Care Commission Act in 2017 (5). In 2018, the Secretary of Health and Human Services convened the National Clinical Care Commission (NCCC) to provide recommendations to leverage federal policies and programs to more effectively prevent and control diabetes and its complications (6,7). The purpose of this article is to provide a brief summary of the recommendations of the NCCC.

The legislation that established the NCCC specified that it include 12 private-sector members with expertise in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, patient advocacy, and public health and 11 individuals representing federal agencies including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Indian Health Service, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Office of Minority Health, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (7,8).

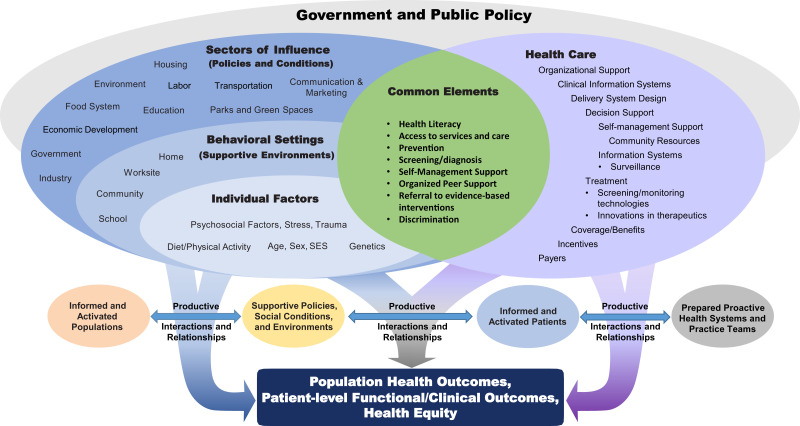

The NCCC recognized that diabetes is both a societal problem that requires a trans-sectoral, all-of-government approach to prevention and treatment and a health condition that requires complex medical care. Accordingly, the NCCC adopted a framework that combined elements of the Socioecological Model and the Chronic Care Model (Fig. 1) (6,7). The Socioecological Model highlights ways in which social factors, environmental exposures, community attributes, and group characteristics interact to influence the health of individuals. The Chronic Care Model recognizes the importance of access to comprehensive, affordable, and high-quality health care and identifies six categories of clinical practice changes that can lead to improved health outcomes for people with diabetes. While these two models have distinct elements, some elements are common to both, including access to services, health literacy, self-management support, organized peer support, and mitigating the negative impact of discrimination (6,7).

Figure 1.

Framework adopted by the NCCC that combines elements of the Socioecological Model and the Chronic Care Model. SES, socioeconomic status.

The NCCC gathered information from federal agencies, interested parties, key informants, and the public, conducted systematic searches and reviews of the scientific literature, and drafted recommendations. Recognizing that the diabetes epidemic in the U.S. is driven in part by social and environmental factors, the NCCC obtained information from both non–health-related and health-related federal agencies whose policies and programs could affect diabetes risk and outcomes (7,8). Initially, the NCCC developed a survey and distributed it to nine health-related agencies and three non–health-related agencies. The survey solicited information about department and agency policies and programs relevant to diabetes and any evaluations of their impact. To develop evidence-based and actionable recommendations, the NCCC formed three subcommittees focused on 1) population-wide strategies to prevent and control diabetes; 2) targeted diabetes prevention strategies for individuals at risk for type 2 diabetes, including those with prediabetes; and 3) the treatment of diabetes and its complications in individuals with diabetes (6,7). The three subcommittees reviewed agencies’ responses and, when needed, sought clarification and requested additional information. The subcommittees also requested information about programs and policies from other agencies and departments that did not receive the survey (7,8). In total, the NCCC solicited and received information from 10 health-related and 11 non–health-related federal agencies.

The subcommittees also identified stakeholder organizations whose missions overlapped with the NCCC’s charge and consulted key informants whose subject matter expertise was relevant to the work of the Commission. They sought input through video meetings, conference calls, and written communication. Between 2019 and May 2021, the NCCC received presentations from more than 50 key informants. Each subcommittee also developed a list of questions to guide literature searches relevant to their focus areas. Librarians at the National Library of Medicine conducted the searches, and the subcommittees reviewed the relevant publications (7,8).

Finally, in compliance with Federal Advisory Committee Act requirements, all deliberations that involved the entire NCCC were open to the public. Twelve public meetings took place. In addition, the NCCC invited public input through Federal Register Notices, sought written comments prior to public meetings, encouraged verbal presentations at NCCC meetings, and welcomed e-mail comments sent directly to the Commission. The NCCC reviewed all public comments and, when appropriate, integrated them into its report (7,8).

The three subcommittees used an iterative process to develop recommendations. All recommendations addressed federal policies and programs and were prioritized according to strength of evidence and the recommendations’ reach and scope, practicability, likely effectiveness and safety, affordability, and impact on health equity. The subcommittees reported their progress, shared their findings, and presented draft recommendations at the public meetings. The subcommittees presented and received feedback on their near-final recommendations at the NCCC’s public meeting on 22 June 2021. At its final public meeting on 8 September 2021, the entire NCCC reviewed and voted unanimously to approve the final recommendations (7,8).

Results

The NCCC determined that a three-pronged approach is needed to address diabetes. First, the federal government must implement population-wide strategies to prevent and treat diabetes (9,10). Second, it must enhance individual-level interventions that target high-risk individuals to prevent type 2 diabetes (11,12). Third, it must address barriers and facilitate treatment of diabetes and its complications (13,14). The NCCC also established three foundational recommendations to guide all federal efforts to prevent and treat diabetes: 1) increase access to health care; 2) promote health equity; and 3) develop infrastructure to increase engagement of, and coordination among, health-related and non–health-related federal agencies (15,16). Herein, we summarize the recommendations of the NCCC around these themes and outline next steps in implementing the Commission’s recommendations (16,17).

Population-Wide Strategies to Prevent and Control Diabetes

The NCCC recommends that the policies and programs of non–health-related federal agencies and departments that address agriculture, food, housing, transportation, commerce, and the environment be aligned with the policies and programs of health-related agencies and departments to prevent and control diabetes and reduce diabetes disparities (9,10).

Many policies and programs of the USDA profoundly affect the nutritional status of Americans. In fiscal year 2021, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children served approximately 6.2 million low-income women, infants, and children each month (18). It seeks to ensure that pregnant and postpartum women have access to nutritious foods, that they deliver infants with appropriate birth weights, and that those children achieve appropriate BMI percentiles. Changes are recommended to update the technology infrastructure of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children to increase participation among eligible women, to enable participants to buy and consume more fruits and vegetables, and to promote breastfeeding as the optimal infant feeding choice (9,10).

The USDA Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) addresses food insecurity and access to foods and beverages for approximately 42 million lower-income Americans each year (19). SNAP is a valuable program for reducing food insecurity, but its impacts on diet quality and diabetes risk have not been optimized. For example, in 2016, SNAP households spent approximately 10% of food dollars on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) (20). The NCCC recommends changes to the SNAP benefit to expand outreach to enable all SNAP-eligible individuals to receive SNAP benefits, increase the benefit to better reflect the current prices of healthy foods in today’s marketplace, provide incentives for the purchase of fruits and vegetables, remove SSB as allowable SNAP purchases, and expand educational efforts to achieve better food and nutrition security and reduce nutrition-related diabetes risks (9,10).

The NCCC further recommends that all federal agencies promote the consumption of water over SSB (9,10). SSB represent the largest single source of added sugar in the American diet (30–40%) and account for 50–90% of the recommended daily limit of added sugars (21). The highest intake of SSB occurs among adolescents, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic people, and groups with lower socioeconomic status (22). To promote changes in normative behaviors, the NCCC recommends that the Surgeon General issue a comprehensive report on the health effects of SSB and that the sale of SSB be restricted on school campuses and in federal office buildings. The Departments of Education and Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency should collaborate to ensure that water consumption replaces the consumption of SSB and that free, clean water is accessible on all school campuses. The NCCC also recommends that the Congress enact an excise tax of as little as 1 cent per ounce (about 10% of the price) to be added to the cost of SSB to reduce consumption, and that the revenues from the tax be used to fund health promotion activities, including access to safe drinking water (9,10).

The USDA supports the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs, which together serve approximately 30 million children each day (23). The USDA also supports the Summer Food Services Program and Seamless Summer Option, federally funded, state-administered programs that reimburse nonprofit community organizations to serve free, healthy meals to children and teens in low-income communities during the summer (24). The NCCC recommends that these programs be provided sufficient financial resources to purchase foods that meet nutritional standards and that summer meal programs be expanded to serve more of the low-income children served by the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs (9,10).

The NCCC also recommends that the USDA harness the Farm Bill ($86 billion per year) (25) to better prevent and control diabetes and reduce disparities. This can be done by increasing funding to three programs: the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program, which targets the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts; the Specialty Crop Research Initiative, which addresses the sustainability of the specialty crop industry; and the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which provides grants and loans to improve access to fresh and healthy foods in low-income settings (9,10).

The NCCC recommends that the Food and Drug Administration improve the nutritional status of the general population by improving food and beverage labeling and limiting misleading product claims. The general public, especially individuals with lower education and income levels, are frequently misinformed by manufacturers about the nutritional value and health risks of foods and beverages (26). Inaccurate and misleading marketing claims about health benefits (such as “whole grain,” “low sugar,” and “real”) make it difficult for individuals to accurately identify risks and make informed choices (27). The NCCC recommends that clear, direct, and compelling food and beverage labeling, such as traffic light icons, be implemented to inform consumers’ dietary choices. The Federal Trade Commission should also be empowered to restrict commercial advertising and marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children under the age of 13 years who are unable to objectively evaluate marketing claims (9,10).

Having paid maternity leave for at least 3 months is associated with higher rates, longer duration, and greater intensity of breastfeeding (28). These are associated with reduced risk of diabetes among mothers and lower rates of obesity among their offspring (29). The NCCC recommends that the Department of Labor ensure that all work sites offer lactation support for breastfeeding mothers and that the Congress enact universal, paid maternity leave for at least 3 months (9,10).

Attributes of built and ambient environments influence diabetes risk and are subject to federal policies and programs (30–33). Housing quality and area-level attributes such as walkability, green spaces, physical activity resources, and opportunities for active transport are determinants of type 2 diabetes risk (34,35). The NCCC recommends that the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Internal Revenue Service, through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program, expand housing opportunities in low-poverty neighborhoods and that the Department of Transportation better address green spaces, walkability, and opportunities for active transport. The NCCC also recommends that the Environmental Protection Agency ensure that its policies, practices, regulations, and funding decisions lead to environmental changes to prevent and control exposures to air pollution, contaminated water, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals that affect diabetes risk (9,10).

Individual-Level Interventions That Target High-Risk Individuals to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes

To address type 2 diabetes prevention among high-risk individuals, the NCCC recommends interventions to increase awareness and the diagnosis of prediabetes on a population basis by increasing the availability of, referral to, and insurance coverage for the National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) Lifestyle Change Program (LCP), and the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (MDPP), and expanding the use of metformin by facilitating FDA review and approval of metformin for diabetes prevention (11,12).

Translation of the results of the National DPP clinical trial into real-world settings has been slow. There are approximately 96 million American adults with prediabetes, but fewer than one in five adults with prediabetes is aware of the diagnosis and only 5% of them have ever been advised by a physician to participate in the National DPP LCP (1,11,12,36). The NCCC recommends expansion of the CDC campaign to raise awareness of prediabetes and promote enrollment in the National DPP LCP. It recommends that the CMS cover hemoglobin A1c testing when it is used to screen for prediabetes. It further recommends that the CMS National Quality Forum adopt the American Medical Association’s proposed clinical quality measures to monitor and improve care for patients with prediabetes. These measures require assessment and reporting of screening, treatment, and follow-up for prediabetes and, like the Medicare Advantage Star Rating Program, will serve as an impetus for continuous quality improvement. The NCCC recommends that the CDC continue efforts to streamline the National DPP recognition process and that the CMS streamline its payment process for the MDPP. Differences between the two programs should be eliminated or, at a minimum, reduced, and MDPP payment rates should be increased to ensure program sustainability. In addition, the NCCC recommends that coverage be provided for all proven effective modes of LCP delivery, including in-person, telehealth, and online formats. Private insurers should be required to cover the National DPP LCP under the provision of the Affordable Care Act that requires coverage without cost-sharing of preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The MDPP should not be a once-in-a-lifetime benefit. Beneficiaries who are initially unable to fully engage or complete the program should be allowed and indeed encouraged to re-enroll. Since 2012, only 22 states and the District of Columbia have enacted varying levels of Medicaid coverage for the National DPP. A simulation study has suggested that expansion of the National DPP to all state Medicaid Programs would be cost-effective and would improve health equity (37). Incentives should be provided to state Medicaid programs to cover the National DPP (11,12).

Although the DPP clinical trial clearly demonstrated the long-term effectiveness and safety of metformin for diabetes prevention in younger individuals (<60 years of age), in individuals with prediabetes and greater levels of obesity, and in women with prediabetes and histories of gestational diabetes, the FDA has not approved metformin for this indication (38,39). Even though there is strong clinical trial evidence for the efficacy and safety of metformin, the lack of FDA approval of metformin for diabetes prevention is a barrier to its widespread use. Indeed, fewer than 5% of individuals with recently diagnosed prediabetes are ever offered metformin for diabetes prevention (40). The NCCC recommends that funding be provided to the NIH to facilitate a third party to collect, analyze, and present the available data to the FDA and petition it to approve metformin for use in high-risk individuals with prediabetes (11,12).

Address Barriers to and Facilitators of Treatment for Diabetes and Its Complications

There is a gap between the resources available for the treatment of diabetes and its complications and the use of those resources by people with diabetes (11,12). To address this gap, the NCCC recommends improving access to diabetes self-management education, support, and training, increasing patient engagement, and updating guidance for insurance coverage of insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring systems. The NCCC recommends expanding training programs and the diabetes workforce to include community health workers and other nonphysician providers to facilitate team-based care. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should also routinely identify diabetes workforce needs and ensure that the training programs it funds meet those needs. Health Resources and Services Administration training programs should be expanded to train more health care professionals to work in medical shortage areas. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Primary Care Extension Programs and technology-enabled mentoring interventions should be expanded. The NCCC also recommends that new payment models be implemented to support multidisciplinary diabetes treatment teams (11,12,41).

At the practice level, the NCCC recommends that the HHS continue policies implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic to reimburse for virtual care. At the health system level, the NCCC recommends that CMS implement quality measures to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia and enhance patient safety (11,12).

At the health policy level, the NCCC recommends that insulin be made affordable for all Americans who need it (42,43). The NCCC also recommends that a task force, similar to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, be established to identify high-value diabetes services and treatments for the secondary and tertiary prevention of diabetes complications and that certification of their effectiveness and safety by this task force mandate insurance coverage at no out-of-pocket cost. Examples of interventions for secondary prevention of complications might include test strips for self-monitoring of blood glucose and closed-loop insulin delivery systems for people with type 1 diabetes. Examples of interventions for tertiary prevention of complications might include retinal exams to enable timely diagnosis and treatment of diabetic retinopathy, use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers to prevent end-stage kidney disease in people with diabetic kidney disease, and use of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists to prevent recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (11,12).

Foundational Recommendations

The NCCC made three additional foundational recommendations to improve diabetes prevention and control (15,16).

Access to Comprehensive and Affordable Health Care

The Affordable Care Act was designed to extend health insurance coverage to individuals who were not eligible for employer-sponsored health insurance by offering them marketplace coverage at subsidized rates. It was also designed to address the needs of people experiencing poverty by expanding Medicaid eligibility to those who did not previously meet Medicaid coverage requirements (44). The termination of the individual mandate, the proliferation of high-deductible health plans through the marketplace, and the failure of 12 states to expand Medicaid coverage has left a substantial number of people with diabetes underinsured or uninsured (45,46). To improve diabetes prevention and treatment and to prevent its complications, the NCCC recommends that federal policies and programs address these gaps to improve access to and the affordability of health care so that no one at risk for or with diabetes is unable to access high-quality comprehensive health care due to cost (15,16).

Make Health Equity a Guiding Principle for All Federal Policies and Programs

The NCCC recommends that the federal government address health equity in all its policies and programs relevant to the prevention and control of diabetes. Although enhancing trans-agency engagement and collaboration and ensuring access to health care can help to address the social and environmental conditions that contribute to health disparities, it is important to ensure that any changes promote diabetes-related health equity and do not inadvertently increase disparities. For example, CMS policies governing the accreditation or recognition of diabetes self-management training programs that are designed to ensure program quality may create administrative barriers to program availability and, hence, exacerbate health disparities. These disparities may be associated with race (lower availability for non-White people), health status (lower availability for those with comorbidities), and residence (lower availability in urban and rural communities). The NCCC recommends sustained federal action to address and reduce diabetes-related health disparities and promote health equity (15,16).

Establish an Office of National Diabetes Policy

Finally, the NCCC recommends the creation of an Office of National Diabetes Policy (ONDP) to develop and implement a national diabetes strategy initially based on the recommendations of the NCCC. Modeled on the successful Office of National AIDS Policy, this office would leverage and coordinate work across health-related and non–health-related federal agencies to positively change the social and environmental conditions that are enabling the type 2 diabetes epidemic. Although the Diabetes Mellitus Interagency Coordinating Committee, established in 1975 by the National Commission on Diabetes, coordinates activities among a few federal agencies, there is no comprehensive national strategy to address diabetes and no federal entity charged with leading trans-agency efforts to prevent and control diabetes. The NCCC recommends that the ONDP be established at a level above the DHHS and that it be provided with resources to facilitate its effectiveness and enable accountability. The ONDP should include relevant health-related and non–health-related federal agencies. The ONDP’s responsibilities should include 1) overseeing the implementation and monitoring of the NCCC’s recommendations; 2) ensuring collaboration and coordination among health-related and non–health-related federal agencies; 3) advancing a health-in-all-policies agenda with respect to diabetes; 4) providing resources to support Health Impact Assessments for relevant policies and programs across non–health-related departments and agencies; and 5) making recommendations to the executive and legislative branches regarding actions they can take to delay, prevent, and better treat type 2 diabetes and its complications (15,16).

Conclusions

Adopting the NCCC’s recommendations has the potential to substantially reduce diabetes incidence, improve treatment, prevent complications, and improve health equity in the U.S. Translating these recommendations into policy will require substantial advocacy and political resolve. Some of the NCCC’s recommendations will require action from the legislative branch. Others may require administrative action or rulemaking at the level of agencies and departments in the executive branch. Still, others (for example, mandating front-of-package food labeling) may require input from the judicial branch (47).

The NCCC believes that policy makers, interested parties, and most Americans now recognize that social and environmental conditions shape health. It follows that an all-of-government approach is needed to address diabetes prevention and control. By embracing health in all policies, adopting an equity-based approach to governance, addressing diabetes as both a societal and a medical problem, removing barriers to targeted interventions to prevent diabetes, and ensuring that people with diabetes have access to the resources they need to treat diabetes and its complications, the recommendations of the NCCC, if enacted, can contribute to meaningful improvements in the health of the nation (16,17).

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The NCCC acknowledges Alicia A. Livinski and Nancy L. Terry, biomedical librarians from the National Institutes of Health Library, Division of Library Services, Office of Research Services, who performed the literature searches. The NCCC also thanks Yanni Wang (International Biomedical Communications) and Heather Stites (University of Michigan) for their editorial assistance.

Funding. The NCCC was supported through a Joint Funding Agreement among eight federal agencies: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Indian Health Service (IHS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Office of Minority Health (OMH). The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP), and the Office on Women’s Health (OWH) provided management staff and contractor support.

The funders had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Health and Human Services or other departments and agencies of the federal government.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented at the 82nd Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, New Orleans, LA, 3–7 June 2022.

Footnotes

All authors were members of the National Clinical Care Commission.

Retired

This article is part of a special article collection available at https://diabetesjournals.org/collection/1586/The-Clinical-Care-Commission-Report-to-Congress.

This article is featured in a podcast available at diabetesjournals.org/care/pages/diabetes_care_on_air.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Statistics Report. Accessed 3 August 2022. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html.

- 2. Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care 2020;44:258–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Diabetes Association . Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 2018;41:917–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Commission on Diabetes . Report of the National Commission on Diabetes to the Congress of the United States: the long-range plan to combat diabetes. Vol. I. 1975. Available from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31210023083353&view=1up&seq=4&skin=2021

- 5. United States Code . Public Law 115-80. Accessed 18 July 2022. Available from https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ80/PLAW-115publ80.pdf

- 6. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications, 2021. Chapter 1. Background. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 7. Herman WH, Bullock A, Boltri JM, et al. The National Clinical Care Commission Report to Congress: background, methods, and foundational recommendations. Diabetes Care 2023;46:e14–e23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications, 2021. Chapter 2. Methods. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 9. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications, 2021. Chapter 4. Population-Level Diabetes Prevention and Control. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 10. Schillinger D, Bullock A, Powell C, et al. Leveraging federal programs for population-level diabetes prevention and control: recommendations from the national clinical care commission. Diabetes Care 2023;46:e24–e38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications, 2021. Chapter 5. Diabetes Prevention in Targeted Populations. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 12. Boltri J, Tracer H, Strogatz D, et al. Recommendations from the NCCC Report to Congress: prevention in people with prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2023;46:e39–e50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications, 2021. Chapter 6. Treatment and Complications. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 14. Greenlee MC, Bolen S, Chong W, et al. Improving diabetes treatment and reducing complications. Diabetes Care 2023;46:299–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress. Chapter 3. Foundational Recommendations to Address Diabetes. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 16. Conlin PR, Boltri JM, Bullock A, et al. The National Clinical Care Commission Report to Congress: summary and next steps. Diabetes Care 2023;46:e60–e63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications, 2021. Chapter 7. Looking Forward. Accessed 19 July 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 18. US Department of Agriculture . Economic Research Service. Accessed 3 October 2022. Available from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/wic-program/

- 19. Carlson S, Keith-Jennings B. Policy futures: SNAP is linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower health care costs. Washington, DC, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018. Accessed 3 October 2022. Available from https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-nutritional-outcomes-and-lower-health-care

- 20. Garasky S, Mbwana K, Romualdo A, Tenaglio A, Roy M. Foods Typically Purchased by SNAP Households. Alexandria, VA, Food and Nutrition Service, 2016. Accessed 3 October 2022. Available from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/foods-typically-purchased-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap-households

- 21. Marriott BP, Olsho L, Hadden L, Connor P. Intake of added sugars and selected nutrients in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2006. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2010;50:228–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among U.S. adults, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017;270:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Food and Nutrition Service . Building Back Better School Meals. Alexandria, VA, Food and Nutrition Service. Accessed 3 October 2022. https://www.fns.usda.gov/building-back-better-school-meals

- 24. Jones JW, Toossi S, Hodges L. The Food and Nutrition Assistance Landscape: Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Report, EIB-237. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Congressional Research Service . The 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334): Summary and Side-by-Side Comparison. Washington, DC, Congressional Research Service. Accessed 3 October 2022. Available from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45525

- 26. Malloy-Weir L, Cooper M. Health literacy, literacy, numeracy and nutrition label understanding and use: a scoping review of the literature. J Hum Nutr Diet 2017;30:309–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pomeranz JL, Lurie PG. Harnessing the power of food labels for public health. Am J Prev Med 2019;56:622–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ogbuanu C, Glover S, Probst J, Liu J, Hussey J. The effect of maternity leave length and time of return to work on breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2011;127:e1414–e1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feltner C, Weber RP, Stuebe A, Grodensky CA, Orr C, Viswanathan M. Breastfeeding Programs and Policies, Breastfeeding Uptake, and Maternal Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, 2018. Accessed 3 October 2022. Available from https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/breastfeeding/research [PubMed]

- 30. Amuda AT, Berkowitz SA. Diabetes and the built environment: evidence and policies. Curr Diab Rep 2019;19:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bonini MG, Sargis RM. Environmental toxicant exposures and type 2 diabetes mellitus: two interrelated public health problems on the rise. Curr Opin Toxicol 2018;7:52–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sargis RM, Simmons RA. Environmental neglect: endocrine disruptors as underappreciated but potentially modifiable diabetes risk factors. Diabetologia 2019;62:1811–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang X, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Herman WH, Mukherjee B, Harlow SD, Park SK. Urinary metals and incident diabetes in midlife women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020;8:e001233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schootman M, Andresen EM, Wolinsky FD, et al. The effect of adverse housing and neighborhood conditions on the development of diabetes mellitus among middle-aged African Americans. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vijayaraghavan M, Jacobs EA, Seligman H, Fernandez A. The association between housing instability, food insecurity, and diabetes self-efficacy in low-income adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2011;22:1279–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ali MK, McKeever Bullard K, Imperatore G, et al. Reach and use of diabetes prevention services in the United States, 2016-2017. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e193160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laxy M, Zhang P, Ng BP, et al. Implementing lifestyle change interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes in US Medicaid programs: cost effectiveness, and cost, health, and health equity impact. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2020;18:713–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . Long-term effects of metformin on diabetes prevention: identification of subgroups that benefited most in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care 2019;42:601–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes prevention. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moin T, Li J, Duru OK, et al. Metformin prescription for insured adults with prediabetes from 2010 to 2012: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:542–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang S, Weyer G, Duru OK, Gabbay RA, Huang ES. Can alternative payment models and value-based insurance design alter the course of diabetes in the United States? Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41:980–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al.; Insulin Access and Affordability Working Group . Conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1299–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fralick M, Kesselheim AS. The U.S. insulin crisis–rationing a lifesaving medication discovered in the 1920s. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1793–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosenbaum S. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep 2011;126:130–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Garfield R, Orgera K, Damico A. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021. Accessed 8 August 2021. Available from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/

- 46. Wharam JF, Zhang F, Eggleston EM, Lu CY, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Diabetes outpatient care and acute complications before and after high-deductible insurance enrollment: a Natural Experiment for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) study. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:358–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress. Washington, DC, National Clinical Care Commission. Accessed 3 October 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress