Abstract

OBJECTIVE

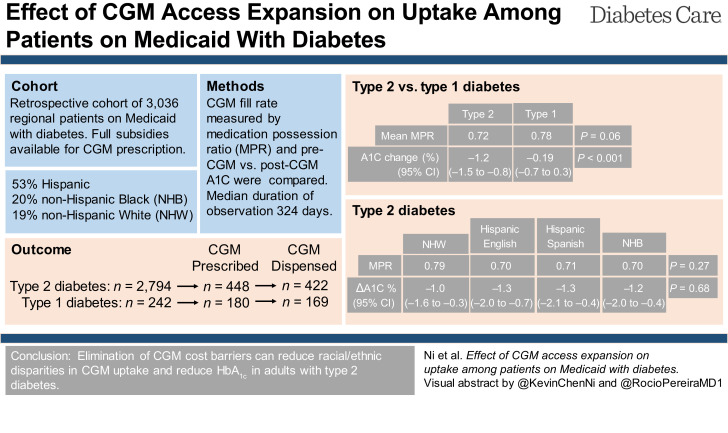

Current studies on continuous glucose monitor (CGM) uptake are revealing for significant barriers and inequities for CGM use among patients from socially underprivileged communities. This study explores the effect of full subsidies regardless of diabetes type on CGM uptake and HbA1c outcomes in a U.S. adult patient population on Medicaid.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study examined 3,036 adults with diabetes enrolled in a U.S. Medicaid program that fully subsidized CGM. CGM uptake and adherence were assessed by CGM prescription and dispense data, including more than one fill and adherence by medication possession ratio (MPR). Multivariate logistic regression evaluated predictors of CGM uptake. Pre- and post-CGM use HbA1c were compared.

RESULTS

CGM were very well received by both individuals with type 1 diabetes and individuals with type 2 diabetes with similar high fill adherence levels (mean MPR 0.78 vs. 0.72; P = 0.06). No significant difference in CGM uptake outcomes were noted among major racial/ethnic groups. CGM use was associated with improved HbA1c among those with type 2 diabetes (−1.2% [13.1 mmol/mol]; P < 0.001) that was comparable between major racial/ethnic groups and those with higher fill adherence achieved greater HbA1c reduction (−1.4% [15.3 mmol/mol]; P < 0.001) compared with those with lower adherence (−1.0% [10.9 mmol/mol]; P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

CGM uptake disparities can largely be overcome by eliminating CGM cost barriers. CGM use was associated with improved HbA1c across all major racial/ethnic groups, highlighting broad CGM appeal, utilization, and effectiveness across an underprivileged patient population.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The recent exponential increase in continuous glucose monitor (CGM) adoption for those with type 1 diabetes has come with widening disparities between the least and most socially privileged (1–6). There is currently much interest in expanding access to CGM for patients with type 2 diabetes not at glycemic target to help achieve better HbA1c, lower glycemic variability and hypoglycemic events, and increased time in range (7–9). While inequitable CGM access will further increase disparities in diabetes health outcomes, affordable CGM access and follow-up can help address critical gaps in diabetes management to achieve better long-term health outcomes and disparity reductions for all patients with diabetes.

A regional Medicaid plan and offering of the State Medicaid program provides free or low-cost health insurance for low-income residents of a major metropolitan city and adjacent counties, allowing access to services at a local multiclinic safety-net health care system. Since October 2020, the intermittently scanned CGM Freestyle Libre 2 (Abbott Diabetes Care) has been available to patients with diabetes who are covered by the regional Medicaid plan with no restrictions and $0 copay. This was a huge expansion of access given FreeStyle Libre 14-day and Libre 2 were only previously covered for individuals requiring three or more daily insulin injections. The real-time CGM Dexcom G6 (Dexcom, Inc.) has also been available to patients on the regional Medicaid plan but is not on formulary and therefore requires a prior authorization review. Both primary care and endocrinology practitioners have been able to offer and prescribe the Libre CGM at their discretion without restrictions typically imposed by other plans, such as intensity of insulin regimen or number of daily finger-sticks. The aim of this study was to measure the potential for full subsidies to ameliorate economic barriers to CGM use and contribute to better HbA1c outcomes in patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

Source of Data

This study was completed as a retrospective analysis of electronic medical record data of patients with diabetes who were seen at a multiclinic urban safety-net health care system and who had access to CGM through their regional Medicaid plan. The health care system provides primary care and pharmacy services at 11 clinic locations and integrated specialty care, including endocrinology. Diabetes self-management support is provided by clinic nurses and clinical pharmacists at the primary care sites and by a certified diabetes care and education specialist–credentialed nurse at the endocrine clinic.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #21-4867).

Cohort Definition

We identified all patients ≥18 years of age with the regional Medicaid plan and any diabetes diagnosis (using established Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine ICD-10 codes) who visited a primary care or endocrine provider in the health care system between October 2020 and March 2022. Chart review of patients with type 1 diabetes was performed to confirm accurate type 1 versus type 2 diabetes assignment. Latent autoimmune diabetes was included with type 1 diabetes. Patients who were pregnant during the study period were excluded from the study due to their protected status as a vulnerable population by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

In addition to demographic data and diabetes ICD-10 codes, insulin prescriptions/dispenses, CGM prescription/dispenses, and HbA1c (since April 2019) were obtained from the health care system Epic electronic medical record through June 2022. Secondary analysis of CGM utilization and HbA1c change excluded individuals with first CGM dispense dates after January 2022 to allow for sufficient follow-up time of a minimum of 6 months.

Assessment of CGM Adherence

CGM utilization was calculated using the validated medication possession ratio (MPR) with the numerator defined as total number of days covered by sensor kits (14 days for FreeStyle 1 and 2 and 10 days for Dexcom G6) patient picked up and the denominator defined as days from first sensor pickup to the latter of the data-pull date or the end date of most recent fill. MPR >1.00 was allowed in order to capture earlier refills.

HbA1c Change

HbA1c change was calculated by determining the difference between pre-CGM use HbA1c (closest HbA1c preceding CGM prescription) and latest available HbA1c. Individuals with new diabetes, defined as CGM prescription happening within 1 year of diabetes diagnosis, were excluded to eliminate confounding HbA1c improvements arising from new diabetes diagnosis interventions. HbA1c was measured by enzymatic assay using an Atellica CH 930 Analyzer (Siemens Healthineers AG). Highest reportable HbA1c values are capped at 14.0% (130 mmol/mol), and too high to quantify HbA1c values were truncated to 14.1% (131 mmol/mol) to facilitate numerical calculations.

Statistical Models

Multivariate binomial logistic regression was used to model effects of predictors of getting a CGM prescription (prescribed), picking up CGM (dispensed), having more than one CGM fill, and high CGM fill adherence. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were calculated for logistic regression. High CGM fill adherence was defined as having an MPR >0.90. Validity of dichotomizing at an MPR of 0.90 was confirmed by performing ordinal logistic regression for continuous MPR as described previously (10). Multivariate linear regression was used to model effects of predictors of HbA1c improvement. Coefficients and 95% CI were calculated for linear regression. R 4.2.0 statistical software was used. Multivariate binomial logistic regression (glm), multivariate ordinal logistic regression (orm and rms), multivariate linear regression (lm), and stepwise linear regression (ols_step_both_p and olsrr) were used. Multicollinearity for each model was checked using variable inflation factor (car) with all variable inflation factor values ≤2.0. Two-sided P values were obtained with a significance threshold of 0.05. Regarding multiple comparisons, interpretation of raw P values is considered exploratory.

Results

We identified 3,036 patients with qualifying type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes diagnoses. Of these, 628 patients were prescribed a CGM and 591 were dispensed a CGM, so only 5.9% of those prescribed never picked up sensor kits (Supplementary Table 1). Baseline characteristics of our study population are listed in Table 1 (by type 2 vs. type 1 diabetes and endocrine vs. primary care clinics) and Supplementary Table 1 (by prescribed and dispensed). For patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, male, age, and diabetes duration >1 year were not different between endocrine and primary care clinics (Table 1). In contrast, more patients spoke English and were prescribed/dispensed CGM in endocrine versus primary care clinics for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. While distribution of race/ethnicity, HbA1c at baseline, and insulin regimen were different between endocrine and primary care clinics for those with type 2 diabetes, they were comparable for those with type 1 diabetes. Male, age, language spoken, race/ethnicity, diabetes duration >1 year, diabetes type, baseline HbA1c, insulin regimen, and endocrine specialty care were all significantly different between those prescribed versus not prescribed CGM (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). These same characteristics were not significantly different between those dispensed versus not dispensed, except endocrine care. Duration of observation (time since first CGM dispense to end of observation period) was, on average, 344 days (median 324 days [interquartile range 194–470]). A relatively low number of patients with type 1 diabetes (n = 36 of 169) and type 2 diabetes (n = 10 of 422) exclusively used Dexcom CGM.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | All (N = 3,036) | Type 2 diabetes | Type 1 diabetes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 2,794) | Endocrine (N = 216) | Primary (N = 2,578) | P value* | Overall (N = 242) | Endocrine (N = 170) | Primary (N = 72) | P value* | ||

| Sex | 0.21 | 0.66 | |||||||

| Female | 1,726 (57) | 1,620 (58) | 134 (62) | 1,486 (58) | 106 (44) | 76 (45) | 30 (42) | ||

| Male | 1,310 (43) | 1,174 (42) | 82 (38) | 1,092 (42) | 136 (56) | 94 (55) | 42 (58) | ||

| Age (years) | 54 (43–60) | 55 (46–60) | 54 (45–61) | 55 (46–60) | 0.97 | 35 (28–46) | 35 (29–46) | 36 (28–47) | 0.80 |

| Language | 0.040 | 0.034 | |||||||

| English | 2,162 (71) | 1,934 (69) | 166 (77) | 1,768 (69) | 228 (94) | 164 (96) | 64 (89) | ||

| Spanish | 684 (23) | 675 (24) | 40 (19) | 635 (25) | 9 (3.7) | 3 (1.8) | 6 (8.3) | ||

| Other | 190 (6.3) | 185 (6.6) | 10 (4.6) | 175 (6.8) | 5 (2.1) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.049 | 0.58 | |||||||

| NHW | 590 (19) | 490 (18) | 54 (25) | 436 (17) | 100 (41) | 75 (44) | 25 (35) | ||

| Hispanic | 1,624 (53) | 1,548 (55) | 101 (47) | 1,447 (56) | 76 (31) | 51 (30) | 25 (35) | ||

| NHB | 605 (20) | 555 (20) | 45 (21) | 510 (20) | 50 (21) | 32 (19) | 18 (25) | ||

| Asian | 102 (3.4) | 100 (3.6) | 7 (3.2) | 93 (3.6) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| AI/AN | 39 (1.3) | 38 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 35 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 76 (2.5) | 63 (2.3) | 6 (2.8) | 57 (2.2) | 13 (5.4) | 10 (5.9) | 3 (4.2) | ||

| Diabetes duration >1 year | 2,500 (82) | 2,319 (83) | 184 (85) | 2,135 (83) | 0.37 | 181 (75) | 122 (72) | 59 (82) | 0.10 |

| HbA1c at baseline | 7.60 (6.40–10.10) | 7.50 (6.30–9.90) | 9.25 (7.30–11.62) | 7.30 (6.30–9.70) | <0.001 | 9.70 (8.03–11.60) | 9.70 (8.10–11.10) | 10.00 (7.75–12.10) | 0.67 |

| HbA1c at baseline (%) | <0.001 | 0.35 | |||||||

| <7 | 1,144 (38) | 1,121 (41) | 45 (21) | 1,076 (42) | 23 (9.8) | 16 (9.6) | 7 (10) | ||

| 7–8.9 | 822 (27) | 746 (27) | 56 (26) | 690 (27) | 76 (32) | 54 (32) | 22 (33) | ||

| 9–10.9 | 498 (17) | 435 (16) | 45 (21) | 390 (15) | 63 (27) | 50 (30) | 13 (19) | ||

| ≥11 | 527 (18) | 455 (17) | 70 (32) | 385 (15) | 72 (31) | 47 (28) | 25 (37) | ||

| Insulin regimen | <0.001 | 0.056 | |||||||

| No | 1,763 (58) | 1,761 (63) | 51 (24) | 1,710 (66) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Once daily | 462 (15) | 461 (16) | 37 (17) | 424 (16) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Twice daily | 209 (6.9) | 205 (7.3) | 16 (7.4) | 189 (7.3) | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| MDI/pump | 602 (20) | 367 (13) | 112 (52) | 255 (9.9) | 235 (97) | 167 (98) | 68 (94) | ||

| Prescribed CGM | 628 (21) | 448 (16) | 149 (69) | 299 (12) | <0.001 | 180 (74) | 149 (88) | 31 (43) | <0.001 |

| Dispensed CGM | 591 (19) | 422 (15) | 146 (68) | 276 (11) | <0.001 | 169 (70) | 142 (84) | 27 (38) | <0.001 |

Data are n (%) or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated.

Pearson χ2 test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or Fisher exact test.

Predictors of CGM Uptake

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 2, highlighting the effects of the different predictors on CGM outcomes: prescribed, dispensed, more than one fill, and high fill adherence defined as MPR >0.90. Multicollinearity was checked, and no predictor was removed for the multivariate regression model. There were no significant differences by race/ethnic group—Hispanic; non-Hispanic Black (NHB); and Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN)—when compared with non-Hispanic White (NHW) for the CGM outcomes prescribed, dispensed, more than one fill, and high fill adherence.

Table 2.

Predictors of CGM uptake and adherence

| Characteristic | Prescribed CGM | Dispensed CGM | More than one fill | Fill adherence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| NHW | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.91 | 0.66–1.25 | 0.6 | 0.85 | 0.62–1.18 | 0.3 | 0.93 | 0.51–1.66 | 0.8 | 0.92 | 0.59–1.44 | 0.7 |

| NHB | 0.85 | 0.59–1.24 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.60–1.26 | 0.5 | 0.72 | 0.38–1.35 | 0.3 | 0.70 | 0.42–1.16 | 0.2 |

| Asian | 0.76 | 0.31–1.75 | 0.5 | 0.68 | 0.26–1.58 | 0.4 | 2.51 | 0.38–50.2 | 0.4 | 0.20 | 0.02–1.05 | 0.082 |

| AI/AN | 0.66 | 0.20–1.84 | 0.5 | 0.73 | 0.23–2.03 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 0.09–3.46 | 0.4 | 0.34 | 0.05–1.68 | 0.2 |

| Other | 1.36 | 0.64–2.83 | 0.4 | 1.03 | 0.48–2.16 | >0.9 | 0.53 | 0.19–1.67 | 0.3 | 1.81 | 0.69–5.00 | 0.2 |

| Language | ||||||||||||

| English | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Spanish | 0.71 | 0.51–1.00 | 0.053 | 0.71 | 0.50–1.01 | 0.056 | 0.81 | 0.42–1.59 | 0.5 | 1.04 | 0.59–1.83 | 0.9 |

| Other | 0.48 | 0.25–0.91 | 0.028 | 0.51 | 0.26–0.96 | 0.045 | 0.60 | 0.18–2.25 | 0.4 | 1.41 | 0.45–4.64 | 0.6 |

| Age (years) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.078 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.072 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.6 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.3 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Male | 1.26 | 1.00–1.60 | 0.053 | 1.33 | 1.05–1.68 | 0.019 | 0.88 | 0.58–1.33 | 0.5 | 0.93 | 0.67–1.31 | 0.7 |

| Endocrine specialty care | ||||||||||||

| No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Yes | 10.2 | 7.39–14.3 | <0.001 | 10.2 | 7.37–14.1 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 0.90–2.50 | 0.12 | 1.20 | 0.80–1.80 | 0.4 |

| Insulin regimen | ||||||||||||

| No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Once daily | 2.80 | 2.02–3.89 | <0.001 | 2.92 | 2.09–4.09 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 0.57–1.97 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.47–1.53 | 0.6 |

| Twice daily | 4.82 | 3.23–7.14 | <0.001 | 4.98 | 3.32–7.43 | <0.001 | 1.83 | 0.87–3.98 | 0.12 | 1.02 | 0.52–2.00 | >0.9 |

| MDI/pump | 6.21 | 4.48–8.64 | <0.001 | 5.88 | 4.21–8.23 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 1.62–6.08 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 0.80–2.40 | 0.2 |

| Diabetes type | ||||||||||||

| Type 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Type 1 | 1.22 | 0.77–1.93 | 0.4 | 1.01 | 0.64–1.58 | >0.9 | 0.82 | 0.41–1.62 | 0.6 | 0.82 | 0.50–1.34 | 0.4 |

| HbA1c at baseline | 1.29 | 1.23–1.36 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.21–1.33 | <0.001 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.00 | 0.063 | 0.89 | 0.83–0.96 | 0.002 |

OR, 95% CI, and P values calculated using binomial logistic regression.

There was no significant difference between Spanish- and English-speaking for CGM outcomes prescribed, dispensed, more than one fill, and high fill adherence outcomes. In contrast, “other” language had lower odds for CGM initiation outcomes prescribed (OR 0.48 [95% CI 0.25–0.91]; P = 0.028) and dispensed (OR 0.51 [95% CI 0.26–0.96]; P = 0.045). Other language was not a significant predictor for the outcomes more than one fill or high fill adherence.

Age was not a significant predictor of any CGM outcomes. Males had slightly higher odds for CGM dispensed with no difference for the other CGM outcomes. Endocrine specialty care increased odds for CGM outcomes prescription (OR 10.2 [95% CI 7.39–14.3]; P < 0.001) and dispense (OR 10.2 [95% CI 7.37–14.1]; P < 0.001). However, endocrine specialty was not a significant predictor for more than one fill or high fill adherence. Higher HbA1c had slightly greater odds for CGM prescription (OR 1.29 [95% CI 1.23–1.36]; P < 0.001) and CGM dispense (OR 1.26 [95% CI 1.21–1.33]; P < 0.001). However, individuals with higher HbA1c at baseline were less likely to achieve high fill adherence (OR 0.89 [95% CI 0.83–0.96]; P = 0.002). Average MPR (in parentheses) was comparably high across the following baseline HbA1c: <7% (0.82), 7–8.9% (0.81), and 9–10.9% (0.80) versus lower mean MPR among higher baseline HbA1c, >11% (0.66).

Multiple daily insulin injections (MDI)/pump increased odds for CGM outcomes prescribed (OR 6.21 [95% CI 4.48–8.64]; P < 0.001), dispensed (OR 5.88 [95% CI 4.21–8.23]; P < 0.001), and more than one fill (OR 3.11 [95% CI 1.62–6.08]; P < 0.001). Interestingly, insulin use (once daily, twice daily, or MDI/pump) was not a significant predictor for high fill adherence. Type 1 diabetes was not significantly associated with different CGM outcomes (prescription, dispense, more than one fill, and fill adherence) when compared with type 2 diabetes.

To validate dichotomizing high fill adherence as MPR >0.90, ordinal multivariable logistic regression was performed on raw continuous MPR scores as previously described (10). Similar results to those of binominal logistic regression were obtained (Supplementary Table 2).

CGM Adherence

CGM adherence was assessed by MPR. CGM adherence was not significantly different between those with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes (P = 0.06). Violin plots of CGM adherence revealed distribution of patients around MPR 1, including patients with MPR >1, indicating many patients were calling in early for CGM refills (Fig. 1A). Among those with type 2 diabetes, CGM adherence was not significantly different across the racial/ethnic groups: NHW, Hispanic English-speaking, Hispanic Spanish-speaking, and NHB (ANOVA, P = 0.27). Violin plots revealed comparable adherence among major racial/ethnic groups (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

CGM adherence by diabetes and race/ethnicity. CGM fill adherence was assessed by MPR. Violin plot of MPR by diabetes type (A) and major race/ethnicity groups for those with type 2 diabetes (B). P values by t test and ANOVA depicted, respectively. Hispanic-Eng, Hispanic English-speaking; Hispanic-Span, Hispanic Spanish-speaking.

HbA1c Outcomes

The effects of CGM on glycemic control were assessed by comparing post-CGM versus pre-CGM HbA1c difference (Fig. 2). Among those with type 2 diabetes, CGM use was associated with a 1.2% (13.1 mmol/mol) HbA1c decrease (10.1 to 8.9%; P < 0.001). Those with type 2 diabetes and high fill adherence ≥90% MPR achieved greater HbA1c reduction (−1.4% [15.3 mmol/mol], 9.6% to 8.2%; P < 0.001) versus low fill adherence <90% MPR (−1.0 [12 mmol/mol], 10.5 to 9.4; P < 0.001). Bar plot and continuous distribution plot of post-CGM versus pre-CGM HbA1c difference highlights the magnitude of HbA1c change for type 2 diabetes versus type 1 diabetes (Fig. 2A). Among those with type 1 diabetes, CGM use was not significantly associated with HbA1c reduction (−0.19% [3.0 mmol/mol], 9.7% to 9.5%; P = 0.43). Durability of HbA1c change was assessed by comparing pre-CGM with post-CGM initiation HbA1c at 6 ± 3 months versus 12 ± 3 months (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among patients with type 2 diabetes, pre-CGM mean HbA1c was 10.1% (95% CI 9.8–10.4), which improved to 8.9% (95% CI 8.6–9.2) at 6 ± 3 months versus 9.0% (95% CI 8.6–9.4) at 12 ± 3 months. Among patients with type 1 diabetes, pre-CGM mean HbA1c was 9.7% (95% CI 9.2–10.3), which improved to 9.6% (95% CI 9.0–10.3) at 6 ± 3 months versus 9.2% (95% CI 8.5–9.8) at 12 ± 3 months.

Figure 2.

HbA1c change by diabetes and race/ethnicity. Bar plots and continuous distribution plots of post-CGM vs. pre-CGM HbA1c difference by diabetes type (A) and race/ethnicity for those with type 2 diabetes (B). Error bars represent 95% CI. P values of pairwise t tests depicted. Sample size for patients with available pre-CGM and post-CGM HbA1c (type 2 diabetes, n = 221; type 1 diabetes, n = 87). Hispanic-Eng, Hispanic English-speaking; Hispanic-Span, Hispanic Spanish-speaking.

Among those with type 2 diabetes, CGM use was associated with HbA1c decrease across the major racial/ethnic groups: NHW (−1.0% [11 mmol/mol], 10% to 9.0%; P = 0.006), Hispanic English-speaking (−1.3% [14 mmol/mol], 10.1% to 8.8%; P < 0.001), Hispanic Spanish-speaking (−1.3% [14 mmol/mol], 10.2% to 8.9%; P = 0.004), and NHB (−1.2% [12 mmol/mol], 9.9% to 8.8%; P = 0.004). Bar plots and cumulative distribution plots of post-CGM versus pre-CGM HbA1c difference highlight similar HbA1c decreases across racial/ethnic groups (Fig. 2B). There was no significant difference in HbA1c improvement by group (ANOVA, P = 0.68). Stepwise linear regression identified greater MPR (coefficient −1.6 [95% CI −2.4 to −0.8]; P < 0.001) and baseline HbA1c (coefficient −0.80 [95% CI −0.90 to −0.69]; P < 0.001) as significant predictors of HbA1c improvement among those with type 2 diabetes (Supplementary Table 3). All predictors listed were included in the multivariate regression model. Endocrine clinic was associated with less HbA1c improvement versus primary care (coefficient 0.53 [95% CI 0.01–1.0]; P = 0.045). Major racial/ethnic groups versus NHW, language, age, and sex were not significant predictors of HbA1c improvement.

Conclusions

This study is the first to explore the effect of full subsidies for patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes to address CGM access disparities in a diverse and socially underprivileged U.S. patient population on Medicaid. In this study of adult patients with diabetes, full subsidies were met with high CGM interest and uptake across different diabetes types, major racial/ethnic groups, and major languages. CGM fill adherence was notable for high adherence among those with type 2 and type 1 diabetes. Furthermore, many with type 2 and type 1 diabetes (28% and 32%, respectively) picked up refills early (MPR >1.0). These results highlight the broad appeal and sustained interest for all patients with diabetes. Of note, CGM fill adherence was a significant predictor of greater HbA1c improvement among those with type 2 diabetes, which builds on previous studies among those with type 1 diabetes that noted enhanced HbA1c improvement with more frequent CGM use and highlights the potential of CGM use to catalyze better diabetes management (11,12).

Our results suggest that previously noted racial/ethnic disparities to CGM uptake and adherence can largely be overcome by subsidies. Multivariate analysis found no significant difference in prescription and fill adherence among major racial/ethnic groups: Hispanic, NHB, and NHW. This is in contrast to persistence of racial/ethnic disparities for pediatric type 1 diabetes uptake and adherence despite full CGM Medicaid subsidies (11), which may be due to additional socioeconomic and familial barriers unique to pediatric populations with type 1 diabetes (2).

Despite very different racial/ethnic and socioeconomic Medicaid demographics compared with a previous large predominantly NHW and commercially insured cohort (9), our study achieved similar improvements in HbA1c. The greater mean HbA1c improvement among individuals with type 2 diabetes compared with those with type 1 diabetes was also similar to the previous study (9). Of note, baseline HbA1c among CGM users was higher for both those with type 2 and type 1 diabetes versus previously reported largely NHW/commercially insured population: type 2 (8.2%) and type 1 diabetes (8.2%) (9). We speculate that social factors that our Medicaid cohort face contribute to these differences in baseline HbA1c and allowed for slightly greater magnitude of HbA1c improvement. The sample size of patients with type 1 diabetes was small and limited the power to detect significant differences for HbA1c change. While no significant difference between pre- and post-CGM HbA1c was noted, the mean HbA1c tended to trend downward, with 6 ± 3 months versus 12 ± 3 months post-CGM initiation.

Among those with type 2 diabetes, there was no difference in the magnitude of HbA1c improvement by different major racial/ethnic groups—Hispanic English-speaking, Hispanic Spanish-speaking, NHB, or NHW—and high CGM fill adherence was associated with greater HbA1c improvement. These demographics are in striking contrast to the abovementioned largely commercially insured cohort who were 99% English-speaking and predominantly NHW (9). Our results highlight the broad potential impact of CGM on diabetes outcomes across the socioeconomic spectrum and diverse patient communities.

Language was assessed as a barrier due to FreeStyle and Dexcom CGM only being available in English and Spanish. Perhaps facilitated by this language support, Spanish speaking was not a statistically significant barrier to CGM prescription and use. In contrast, speaking other languages was a barrier to CGM prescription, highlighting the need to expand language support. The numbers of patients identifying as Asian or AI/AN were very small, and further research of CGM use in these populations is needed. Only a limited number of patients exclusively used Dexcom CGM, limiting our ability to make CGM-specific comparisons.

Age was explored as a barrier given possible age-related technological barriers, but was found to not be a significant predictor of CGM outcomes. Of note, patients >65 years of age were not represented in the study cohort since these patients were covered under Medicare. Access to endocrinology specialty care was assessed as a CGM catalyst given specialty care can facilitate CGM interest and had 10-fold increased odds for CGM prescription. Notably, endocrine care was not a predictor of high fill adherence, possibly due to broad appeal to both endocrine and nonendocrine patients alike. Severity of diabetes by baseline HbA1c was assessed as a catalyst to CGM use, and 1.0% HbA1c increase had 1.29-fold increased odds for CGM prescription. Interestingly, higher HbA1c predicted lower likelihood to achieve high fill adherence, which highlights potential barriers to adherence in those with the most uncontrolled diabetes. Nonetheless, MPR was persistently high for baseline HbA1c up through <11% and only decreased by a small magnitude for those with HbA1c >11%, which highlights the broad appeal of CGM for patients of all ranges of HbA1c. We speculate that certain social factors that pose challenges for diabetes management may also pose challenges for CGM fill adherence. More work is needed to identify these individual barriers to CGM use.

Insulin regimen was assessed as a CGM catalyst, and intensity of insulin regimen increased the odds of CGM prescription. Insulin regimen did not predict high fill adherence likely also due to broad appeal among insulin and noninsulin user alike. Type 1 diabetes had similar odds for CGM prescription as type 2 diabetes, which suggests broad appeal of CGM not limited to specific diabetes diagnosis.

This study had several limitations. First, the cohort was predominantly composed of patients with type 2 diabetes, and the sample size for type 1 diabetes was smaller, limiting the power to detect significant HbA1c differences and ability to perform additional race/ethnic comparisons for those with type 1 diabetes. The numbers of patients identifying as Asian and AI/AN were very small and merit further studies. Second, though not significant, the OR for many CGM outcomes by major race/ethnic groups compared with NHW was <1, which suggests possible persistent barriers not completely ameliorated by full subsidies that require further investigation. Third, our duration of observation for most patients was 1 year, and studies with longer observation are needed. Fourth, we were not able to examine the quantity or nature of support provided to patients on presentation of the CGM. Though we estimate that the support provided was highly variable depending on available resources at each clinic site, many of our patients had access to endocrine specialty care and certified diabetes care and education specialist support that may not be available at all safety-net clinics. Of note, over half of our patients with CGM did not have endocrine care, and our data importantly demonstrate that endocrine care was not a predictor of high fill adherence, supporting the role for primary care providers to initiate CGM. Specifically, our data support the role of primary care providers at safety-net clinics to initiate and manage CGM. We recognize that our primary care clinic patients had access to clinic nurses and pharmacists for using and troubleshooting CGM, and more research is needed to delineate the support required for optimal CGM initiation in primary care clinics. Fifth, the regional Medicaid plan makes insulin and noninsulin medications very accessible and affordable for patients to implement their diabetes treatment plans, which remains a challenge at many safety-net clinics.

The exponential increase in CGM adoption for those with type 1 diabetes has come with widening disparities in CGM use (1–6). A recent study of CGM use in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes was striking for its finding that increase in CGM use has largely benefited those from higher socioeconomic quintiles in the U.S. in contrast to Germany, where all children are covered by insurance with affordable CGM access: 15% vs. 52.3% for lowest versus highest quintiles (American registry), respectively, in contrast to 48.5% vs. 57% (German) (13). The racial/ethnic disparities are equally striking. Pediatric studies have noted CGM use is 3 to 6 times more likely for NHW than NHB and 1.5 to 3 times for NHW than Hispanic individuals (14,15). Both disparities with lower rates of CGM initiation and higher rates of discontinuation were noted (14). These disparities can persist even when eliminating cost and insurance access, such as when Colorado Medicaid waived out-of-pocket CGM cost for pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes (11). In this study, Hispanic participants were 66% less likely than NHW to achieve optimal use defined as >85% wear, which highlights disparities in continued CGM use. Among patients with type 1 diabetes on Medicare, the increase in CGM use jumped from 3.2% to 24.9% from 2017 to 2019 among NHW versus 0.7% to 11.8% among NHB, highlighting disparities extending to older adults (1).

The predicted cost savings of patients with type 1 diabetes and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes achieving better diabetes management and avoiding costly hospitalizations for hypoglycemia and diabetes-related complications makes sound financial sense for both public and private insurers (16,17). However, 70% of state Medicaid programs do not cover CGM access for those with type 2 diabetes (18). While Medicare recently removed requirements of 4 times/day finger-sticks for CGM use (19), only patients on intensive insulin therapy (three or more injections per day) are eligible: patients with type 2 diabetes on less intensive insulin regimens or with frequent hypoglycemia alone are not eligible (16). Most private insurance plans have similarly restrictive CGM access for those with type 2 diabetes, in addition to high copays and deductibles, which make CGM disproportionately cost-prohibitive for the underprivileged individuals who tend to have plans with less coverage (18).

Technologic advances can exacerbate disparities for those who are denied access to them. In the U.S., the meteoric rise in CGM use has largely benefited the most socially privileged patient populations, though type 2 diabetes and its complications disproportionately affect the most underprivileged patient populations. In this retrospective cohort study, barriers to CGM use were largely overcome with full subsidies, resulting in high fill adherence across major racial/ethnic groups and significant HbA1c improvements among those with type 2 diabetes. Improved CGM coverage can reduce diabetes technology disparities, help patients with diabetes achieve goal clinical outcomes, and facilitate better diabetes management for a greater number of people with diabetes.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Denver Health and its commitment to thoughtful primary and diabetes care for making this study possible.

Funding. K.N. was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Research Service Award (1F30HL136169-03). R.I.P. and C.A.T. were supported by the Denver Health Department of Medicine Academic Enrichment Fund (40150821). R.I.P. and K.S. are Clinical Scholars, supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (77887).

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. K.N. and R.I.P. conceptualized, acquired and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. C.A.T., K.S., and D.B.R. contributed to study design and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.I.P. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.21543273.

References

- 1. Wherry K, Zhu C, Vigersky RA. Inequity in adoption of advanced diabetes technologies among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022;107:e2177–e2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agarwal S, Kanapka LG, Raymond JK, et al. Racial-ethnic inequity in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e2960–e2969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agarwal S, Schechter C, Gonzalez J, Long JA. Racial-ethnic disparities in diabetes technology use among young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:306–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Isaacs D, Bellini NJ, Biba U, Cai A, Close KL. Health care disparities in use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23(S3):S81–S87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker AF, Hood KK, Gurka MJ, et al. Barriers to technology use and endocrinology care for underserved communities with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021;44:1480–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lai CW, Lipman TH, Willi SM, Hawkes CP. Early racial/ethnic disparities in continuous glucose monitor use in pediatric type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:763–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grunberger G, Sherr J, Allende M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology clinical practice guideline: the use of advanced technology in the management of persons with diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract 2021;27:505–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al.; DIAMOND Study Group . Continuous glucose monitoring versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:365–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Gilliam LK, Dlott R. Association of real-time continuous glucose monitoring with glycemic control and acute metabolic events among patients with insulin-treated diabetes. JAMA 2021;325:2273–2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeClercq J, Choi L. Statistical considerations for medication adherence research. Curr Med Res Opin 2020;36:1549–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ravi SJ, Coakley A, Vigers T, Pyle L, Forlenza GP, Alonso T. Pediatric Medicaid patients with type 1 diabetes benefit from continuous glucose monitor technology. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2021;15:630–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson SR, Holmes-Walker DJ, Chee M, et al.; ADDN Study Group . Universal subsidized continuous glucose monitoring funding for young people with type 1 diabetes: uptake and outcomes over 2 years, a population-based study. Diabetes Care 2022;45:391–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Addala A, Auzanneau M, Miller K, et al. A decade of disparities in diabetes technology use and HbA1c in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a transatlantic comparison. Diabetes Care 2021;44:133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lai CW, Lipman TH, Willi SM, Hawkes CP. Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of continuous glucose monitor initiation and continued use in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021;44:255–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipman TH, Smith JA, Patil O, Willi SM, Hawkes CP. Racial disparities in treatment and outcomes of children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2021;22:241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galindo RJ, Parkin CG, Aleppo G, et al. What’s wrong with this picture? A critical review of current Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage criteria for continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:652–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frank JR, Blissett D, Hellmund R, Virdi N. Budget impact of the flash continuous glucose monitoring system in Medicaid diabetes beneficiaries treated with intensive insulin therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23(S3):S36–S44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kruger DF, Anderson JE. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is a tool, not a reward: unjustified insurance coverage criteria limit access to CGM. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23(S3):S45–S55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Herges JR, Neumiller JJ, McCoy RG. Easing the financial burden of diabetes management: a guide for patients and primary care clinicians. Clin Diabetes 2021;39:427–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]