Abstract

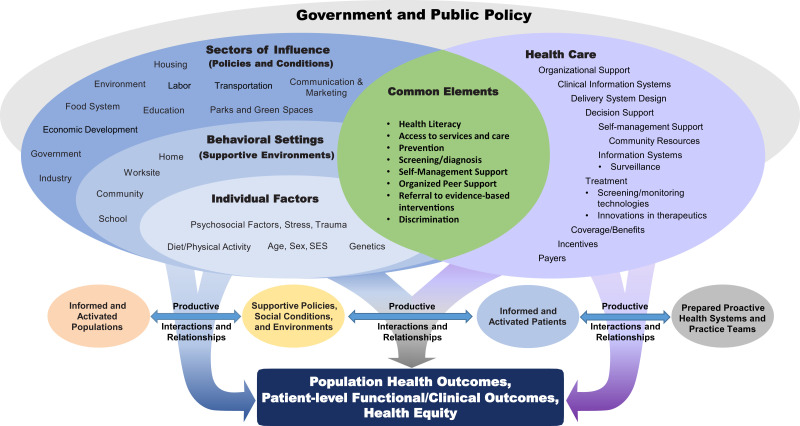

The etiology of type 2 diabetes is rooted in a myriad of factors and exposures at individual, community, and societal levels, many of which also affect the control of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Not only do such factors impact risk and treatment at the time of diagnosis but they also can accumulate biologically from preconception, in utero, and across the life course. These factors include inadequate nutritional quality, poor access to physical activity resources, chronic stress (e.g., adverse childhood experiences, racism, and poverty), and exposures to environmental toxins. The National Clinical Care Commission (NCCC) concluded that the diabetes epidemic cannot be treated solely as a biomedical problem but must also be treated as a societal problem that requires an all-of-government approach. The NCCC determined that it is critical to design, leverage, and coordinate federal policies and programs to foster social and environmental conditions that facilitate the prevention and treatment of diabetes. This article reviews the rationale, scientific evidence base, and content of the NCCC’s population-wide recommendations that address food systems; consumption of water over sugar-sweetened beverages; food and beverage labeling; marketing and advertising; workplace, ambient, and built environments; and research. Recommendations relate to specific federal policies, programs, agencies, and departments, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Trade Commission, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Environmental Protection Agency, and others. These population-level recommendations are transformative. By recommending health-in-all-policies and an equity-based approach to governance, the NCCC Report to Congress has the potential to contribute to meaningful change across the diabetes continuum and beyond. Adopting these recommendations could significantly reduce diabetes incidence, complications, costs, and inequities. Substantial political resolve will be needed to translate recommendations into policy. Engagement by diverse members of the diabetes stakeholder community will be critical to such efforts.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The etiology of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is rooted in a myriad of factors and exposures at the individual, community, and societal levels, many of which also affect the control of all forms of diabetes. Not only do such factors impact risk and treatment at the time of diagnosis but they also can accumulate biologically from preconception, in utero, and across the life course and can then be transmitted intergenerationally. These include inadequate nutritional quality, poor access to physical activity resources and opportunities, chronic stress from many sources (e.g., adverse childhood experiences, racism, and poverty), and exposures to metabolically active environmental toxins (1–3). Such factors may operate independently or interact with individuals’ innate biological factors to elevate risk.

Given this understanding of diabetes, it is clear that many programs administered by federal agencies and departments, including those not directly related to health care, have substantial effects on diabetes. In the U.S., government policies and programs that address agriculture, housing, transportation, and commerce, among others, affect diabetes risk and outcomes, a fact that calls for a health-in-all-policies approach (4). Ensuring that the policies and programs of non–health care-related federal agencies and departments are designed to prevent and control diabetes, and do not contribute to the diabetes epidemic, should be a high priority.

The language in the National Clinical Care Commission (NCCC) charter specified that any recommendations must advance quality of care or public awareness. Many Americans at risk for and with diabetes live in unsupportive environments and have inadequate resources to address diabetes. This has challenged clinicians’ ability to prevent and manage diabetes and prevent its complications (1,5–7) and has led to high levels of frustration and clinical burnout for those working in settings and systems that do not account for the social, material, and psychological needs of individuals with diabetes (8). As a result, diabetes clinical care is evolving from the “traditional” model of care (lifestyle counseling and medications) to an “integrated, patient-centered” model of care that also includes robust clinic–community linkages. These linkages often involve referrals to federal programs that provide assistance with food and nutrition, housing, and transportation. Prior to the 2021 NCCC Report to Congress and the Secretary of Health and Human Services (9), there had been no formal assessment of whether such federal programs help to prevent diabetes and/or its complications or whether they meet the needs of individuals with or at risk for diabetes. Taken together, such individuals represent nearly half of U.S. adults and roughly two-thirds of all U.S. adults eligible to receive any form of public assistance.

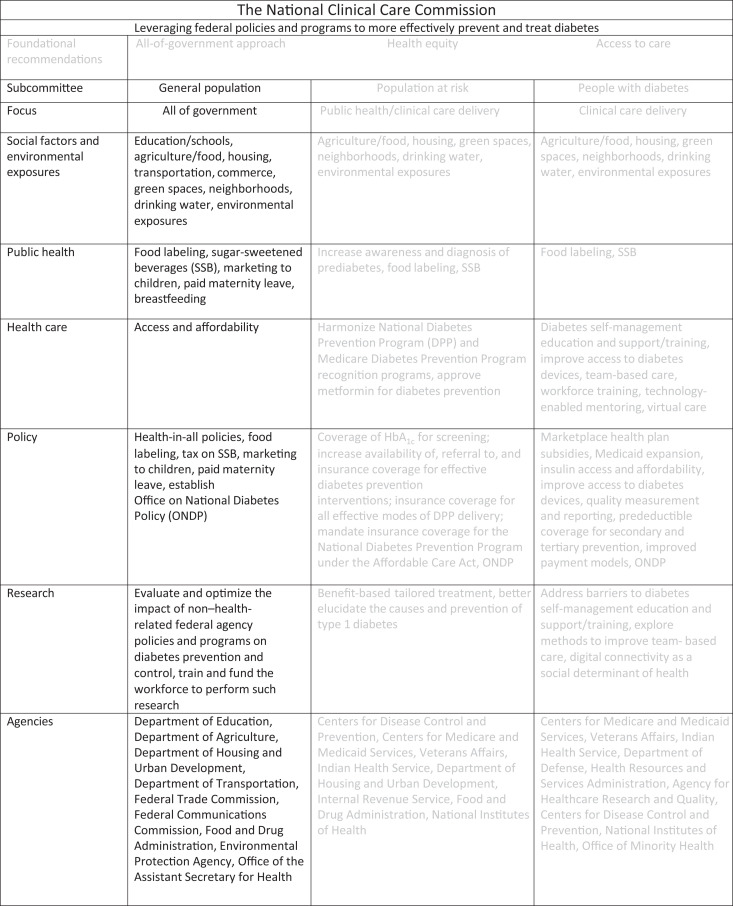

The NCCC determined that it is critical to design, leverage, and coordinate federal policies and programs to foster social and environmental conditions to facilitate the prevention and treatment of diabetes. Doing so will not only support clinicians caring for individuals at risk for or with diabetes but also increase the return on investment of federal expenditures by ensuring that non–health-related federal programs enhance, rather than undermine, the effectiveness of federal health care programs. Many recommendations made by the NCCC Population-Level Diabetes Prevention and Control Subcommittee were intended to cultivate environments that facilitate clinicians’ efforts to provide high-quality, integrated care and support individuals with diabetes to successfully prevent or self-manage diabetes. These recommendations are aligned with the NCCC’s guiding framework (Fig. 1) (9,10).

Figure 1.

Framework adopted by the NCCC that combines elements of the Socioecological Model and the Chronic Care Model. SES, socioeconomic status.

One of the NCCC’s specific duties was to make recommendations to improve federal education, awareness, and dissemination activities related to diabetes prevention and treatment. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the health literacy of a large segment of U.S. adults is inadequate. Individuals with diabetes who are beneficiaries of Medicare and Medicaid have high rates of limited health literacy, as do others are who are disproportionately affected by T2D, including members of certain racial and ethnic subgroups and those with limited education (11,12). Individuals with limited health literacy have less awareness of evidence-based strategies to prevent diabetes and, among those with diabetes, less awareness of strategies to manage diabetes and prevent its complications. For example, limited health literacy is the strongest independent predictor of the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), a driver of T2D risk (13). Clinicians often struggle to assist individuals with limited health literacy and report that such individuals require additional community-level support (14). Many federal agencies support and direct programs that can influence public awareness about diabetes prevention and control. These include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Departments of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Transportation (DOT), and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Many NCCC recommendations in this article relate to the coordination and leveraging of the work of these federal agencies and departments to enhance education and awareness of diabetes prevention and care.

Below, we describe the rationale and scientific evidence base supporting the population-wide recommendations of the NCCC that relate to specific federal policies, programs, agencies, and departments. We also provide detailed recommendations in five accompanying tables.

Recommendations

USDA: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Food insecurity and insufficiency increase the risk of T2D (15–17), contribute to difficulty managing diabetes (18), and may lead to costly and disabling complications (18). Food-insecure populations are more likely to experience low-quality diets, chronic stress, cyclical overeating, and weight gain, all of which are risk factors for T2D and poor diabetes self-management (19,20). It is therefore important to recognize the relationship between food insecurity and diabetes and appreciate that increasing accessibility of healthy foods will prevent T2D and help people better manage the condition (21). The USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) supplements the food budgets of income-eligible individuals and households (approximately 40 million people per year) so they can purchase food and move toward self-sufficiency (22,23). SNAP reduces food insecurity but has not yet adequately addressed dietary quality (24). Healthier, nutrient-rich foods often cost more than energy-dense foods with lower nutritional value. SNAP has been more successful in ensuring food security but less successful in providing “nutrition security” (25,26). SNAP recipients must often purchase lower-cost, less healthy food items (27), sacrificing nutrition quality and elevating their risk for obesity, diabetes, or diabetes complications.

Because of the substantial overlap between eligibility for SNAP and for Medicaid and Medicare (28–30), efforts to address food insecurity and dietary quality in SNAP beneficiaries will provide substantial health benefits for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries (31).

The NCCC identified four domains of the SNAP program that need to be addressed.

Improving Dietary Quality

SNAP participants consume fewer fruits and vegetables and more added sugars than recommended in diets to prevent and manage diabetes (25,32). Using small-grant programs, the USDA has tested healthy-food incentive pilot programs to help SNAP participants purchase healthier (more costly) items, especially fruits and vegetables (33). Rigorous evaluations of these initiatives have consistently shown benefits in improving dietary quality (34,35). The Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program, formerly known as the Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives Program, is one such promising USDA program that could help prevent T2D and improve outcomes from diabetes if implemented more broadly. In 2021, the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture announced an investment of over $34 million to support this program, including the Produce Prescription Project, which provides incentives to increase the purchase of fruits and vegetables by low-income families, tribal communities, and other at-risk communities.

Additionally, SSB are one of the main sources of added sugars in U.S. diets, especially among SNAP recipients (32). SSB contain excess calories, have limited to no nutritional value (36), and contribute to the development of T2D and diabetes complications. To help ensure that SNAP benefits are used to assist in achieving nutrition security and do not contribute to the onset of diabetes or diabetes complications, experts have recommended removing SSB as allowable SNAP purchases (37–40). Over a 10-year period, eliminating the use of SNAP subsidies to purchase SSB could prevent 240,000 cases of T2D among SNAP beneficiaries (41). These estimates consider the possibility that individuals may substitute calorie-dense foods for the SSB that they are avoiding.

Expanding Educational Efforts

To achieve maximum benefit from these healthy-food incentives and purchase exclusions, greater outreach to and education of SNAP participants is required. SNAP-Education (42) is a promising program that, when linked to incentives, could help SNAP participants better achieve food and nutrition security and reduce nutrition-related diabetes risks.

Increasing the Benefit

The USDA Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), historically used to determine SNAP benefit allowances, was reevaluated in 2021, resulting in an increase of approximately $36 per person per month in fiscal year 2022 (FY2022), excluding the additional funds provided as part of pandemic relief. This is a response to the many analyses reporting that the food procurement and preparation requirements and expectations associated with the TFP were unrealistic and SNAP benefit allotments provided insufficient funds for most SNAP participants (43,44). The revised TFP reflects the current price of foods in today’s marketplace and includes more fish and red and orange vegetables to align with the 2020–25 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (45).

Expanding Awareness and Accessibility

Challenges associated with technology, numeracy, and language proficiency have kept many SNAP-eligible individuals from receiving SNAP benefits and contributed to disparities in the receipt of SNAP benefits (46,47). State-level innovation is needed to overcome these barriers including increasing public awareness of the benefit (including promotion of SNAP in various languages), streamlining the application process, increasing the number of sites that accept SNAP, and helping stores in rural areas and “food deserts” meet minimum stocking requirements.

The NCCC concluded that the USDA SNAP program should be further enhanced to reduce food insecurity and improve nutrition sufficiency, both of which will help prevent T2D and diabetes complications. NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

NCCC recommendations related to food systems

| Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| USDA | Implement SNAP-wide fruit and vegetable incentives, demonstrated to be effective by the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program, for all beneficiaries by providing at least a 30% incentive on the purchase of fruits and vegetables to improve dietary quality |

| USDA | Eliminate SSB from allowable SNAP purchases |

| USDA | Improve and expand SNAP-Education to provide diabetes and nutrition education and awareness programs for beneficiaries to increase fruit and vegetable consumption, reduce added sugars consumption (especially SSB), and increase media/marketing literacy, as well as increase support for policy, systems, and environmental approaches to improve dietary quality |

| USDA | Incentivize testing and implementation of innovative state-level policies, practices, and programs to enhance the access to and receipt of SNAP benefits by eligible individuals and households and to reduce geographic, racial, ethnic, and linguistic disparities in SNAP enrollment and retention |

| USDA | Sustain efforts to ensure that SNAP benefit allotments are adequate to allow for both food and nutrition security to help prevent and manage diabetes among beneficiaries and implement a process to regularly assess and update the adequacy of SNAP benefits with respect to lowering diabetes risk and managing diabetes |

| USDA | Further strengthen the WIC program by sustaining the evidence-based, prescriptive WIC food package; expand funding for breastfeeding peer counseling services; invest in improvements to information systems and technology to enable greater access and service for WIC participants |

| USDA | Strengthen, increase funding for, and improve access to and participation in summer feeding programs, including partnerships and collaboration between public and private sectors, to promote innovation in rural areas and other high-risk areas where participation has been low; funding for these programs should be increased to enable scaling to meet population needs |

| USDA | Maintain the nutrition standards found to be salutary in the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) and provide adequate funding for schools to 1) purchase, prepare, and serve healthy, quality foods and beverages for school meals and snacks to meet the HHFKA nutrition standards; and 2) deliver training and technical assistance to support maintenance and attainment of HHFKA nutrition standards and skills to run a program to effectively prevent diabetes |

| USDA, Department of Education | Prohibit the sale of calorically dense and nutrient-poor foods, including SSB, on public school campuses and employ an incentive program to enable schools to cover essential costs such as those for physical activity/athletic programs previously underwritten by the sale of such unhealthy foods and beverages; receipt of federal funds for school-based food programs should be tied to implementation of such restrictions |

| USDA, Department of Education, Department of Interior, Environmental Protection Agency | Ensure that all students in public schools have reliable access to safe, appealing, and free drinking water; this could be accomplished through a combination of federal incentives and possibly tying receipt of funding for school-based food programs for implementation in the future |

| USDA | Significantly expand and increase funding for the USDA Specialty Crop Block Grants to support the safe production and distribution of food and drive demand through education for specialty crops to increase dietary diversity as an aid to help people prevent and/or control diabetes; funding and expansion should be implemented by 2030 to achieve population-wide benefits |

| USDA | Significantly increase funding for the USDA Specialty Crop Research Initiative grants to improve specialty crop production efficiency, handling and processing, productivity, and profitability (including specialty crop policy and marketing) over the long term in a sustainable manner; funding and expansion should be implemented by 2030 to achieve population-wide benefits |

USDA: Nutrition for Women and Children Through Non-SNAP Nutrition Assistance Programs

T2D was once considered a disease of older adults. Unfortunately, the incidence of T2D is now increasing rapidly in children and adolescents, especially children from low-income families and children of color (48). Rates of gestational diabetes also are on the rise (49). The USDA, with its $146 billion annual budget, provides nutritional assistance during pregnancy and early childhood to reduce food insecurity. If redesigned, these non-SNAP programs have the potential to help prevent and control diabetes.

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) serves approximately 7 million participants every month to safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children. Since revising its food package in 2009 to restrict purchases of unhealthy foods, WIC programs have been shown to reduce excess weight gain in pregnant and postpartum women (50), improve birth weight of infants (51), and reduce childhood obesity (52). All of these lower the risk of diabetes.

In 2021, with $490 million provided by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the USDA offered states, tribal nations, and territories the option of boosting the WIC cash value voucher benefit by more than three times the previous amount for up to 4 months (53) to provide temporary relief to families during the pandemic. These additional funds increased the purchasing power of WIC participants and enabled them to buy and consume more fruits and vegetables. The USDA extended this increase in the WIC Cash-Value Voucher/Benefit for fruit and vegetable purchases through the first (54) and second (55) quarters of 2022 only.

Evaluations of WIC have found that inadequate technology infrastructure has limited the efficacy of and participation in the program (56,57). While WIC providers have made technological advances by implementing electronic benefit transfer, or e-WIC, transactions nationwide, the WIC certification process continues to pose challenges for applicants and participants. These challenges could be addressed by allowing remote certification, integrating new projects into WIC site computer networks, and enabling innovations (e.g., web-based participant portals, prescreening tools, and text-messaging features) and additional transaction models (e.g., online purchasing and mobile payments). The USDA recently announced that in 2022, it will use $390 million in American Rescue Plan Act funding to increase participation in WIC by modernizing the program. However, the USDA has not yet released implementation details (58).

WIC also plays a critical role in promoting breastfeeding as the optimal infant feeding choice and has demonstrated effectiveness (59) in increasing breastfeeding rates (60,61) among women who utilize WIC services (62–64). However, WIC’s breastfeeding support services (e.g., the WIC Breastfeeding Peer Counselor Program) do not receive adequate funding to offer those services at all WIC sites.

The National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs serve approximately 30 million children each day. Since the inception of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act in 2010, the incidence of obesity among low-income children in the program declined by 47% (65). Recent USDA initiatives have included an additional $1.5 billion to support the purchases of agricultural commodities to help school meal program operators (66) deal with the challenges of supply chain disruptions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and ensure that students have reliable access to healthy meals. The USDA also increased school meal reimbursements by approximately $750 million (67) to help ensure federal reimbursements keep pace with food and operational costs so that schools could continue to serve children despite the rise in food prices. However, some schools continue to face challenges meeting the new nutrition standards, often due to inadequate staff training, equipment, and infrastructure. In addition, many public schools across the country allow or even promote the sale of unhealthy (calorically dense and nutrient-poor) foods, including SSB, on campus (e.g., vending machines, cafeterias, and canteens). Given that school meals contribute to more than half of the daily caloric intake of U.S. children who participate in the food programs, these practices increase children’s risk of obesity and diabetes. Notably, states with more stringent laws regarding the sale of unhealthy food on school campuses have significantly lower rates of obesity among youth (68).

The Summer Meal Programs(Summer Food Service Program and Seamless Summer Option) is a federally funded, state-administered program that reimburses schools, local government agencies, and faith-based and other nonprofit community organizations that serve free, healthy meals to children and teens at approved meal sites in low-income areas during the summer. Schools that participate in the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Program are eligible to apply for the Seamless Summer Option, which makes it easier for schools to feed children during summer vacation (69). In 2021, recognizing the pressures of the pandemic, the USDA established a waiver to allow the Seamless Summer Option to operate when school is open during the regular school year through 30 June 2022 (70). This waiver was established to support students’ access to nutritious meals while minimizing their potential exposure to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). The USDA also established a nationwide waiver to allow school food authorities to claim Summer Food Service Program reimbursement rates through the 2021–2022 school year (71).

However, many children who participate in school meal programs (e.g., National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs) still do not receive healthy meals during the summer. In 2019, the Summer Food Service Program and the Seamless Summer Option through the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs reached only 1 in 7 children (13%) who received free or reduced-price lunch during the 2018–2019 school year.

The Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program provides funding to participating schools so they can provide children with a wide variety of fresh fruits and vegetables that can help prevent diabetes. Studies have shown that the program can significantly increase the fresh fruit and vegetable intake of participating children without increasing calorie intake (72). The program’s budget, however, is only $183 million (FY2021 enacted), or 0.1% of the USDA’s annual budget. There is a much greater demand for this program than available funds can address.

The NCCC concluded that although investments have temporarily increased in the last year, USDA non-SNAP feeding programs could be better leveraged to prevent diabetes in women, children, and adolescents by 1) further enhancing WIC; 2) further harnessing the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs to improve dietary quality; and 3) expanding the Summer Nutrition Programs and the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program. NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 1.

USDA: Programs That Support Farmers to Make the U.S. Food Supply Healthier

The Farm Bill ($86 billion per year) provides a great opportunity to link the aims of supporting farmers and achieving food and nutrition security with public health and health care goals related to diabetes. The Farm Bill is a powerful, underutilized tool to potentially prevent and control diabetes, curb health care spending, and reduce disparities. Three USDA programs could be enhanced to help reduce the risk for diabetes and diabetes complications in the U.S. population.

The Specialty Crop Block Grant Program aims to enhance the competitiveness of specialty crops, which includes fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts. The associated budget is only $85 million per year, or 0.1% of the Farm Bill budget.

The Specialty Crop Research Initiative works to address the critical needs related to sustaining the specialty crop industry including conventional and organic food production systems, over the long term. The associated budget is also only $85 million per year, or 0.1% of the Farm Bill budget.

The Healthy Food Financing Initiative provides grants and loans to improve access to fresh and healthy foods by financing grocery stores, farmers’ markets, food hubs, and co-ops in urban and rural areas. The grants and loans help food retailers overcome the higher costs and initial barriers associated with providing fresh and healthy food options for individuals and families living in low-access areas. Evidence (73) shows that Healthy Food Financing Initiative-financed programs increase food security, reduce intake of added sugars, and decrease the percentage of daily calories from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars. The associated budget is only about $25 million per year, or 0.03% of the Farm Bill budget. In FY2021, through the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, the USDA invested an additional $5 million to improve access to healthy foods in underserved areas, create and preserve quality jobs, and revitalize low-income communities (58).

The NCCC concluded that additional resources should be provided to the USDA to create an environmentally friendly and sustainable U.S. food system promoting the production, supply, and accessibility of foods such as specialty crops (fresh fruits, dried fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts) that will attenuate the risk for diabetes and its complications. NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 1.

USDA, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Treasury, and Office of U.S. Trade Representative: Consumption of Water Rather Than Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

When water replaces caloric beverages, water consumption is associated with improved glycemic control (74). Tap water is the preferred source of drinking water, but in areas where tap water is known to be contaminated, filtered or bottled water is acceptable. Many regions of the U.S. face persistent challenges in providing clean tap water to their populations because of contamination of water sources or the systems that deliver water (75).

Replacing SSB with water in institutions (e.g., schools) and delivering clean water to homes to replace SSB have shown promise (76,77) in reducing obesity and diabetes risk. Modeling studies demonstrate that consuming water instead of SSB could significantly reduce the prevalence of obesity and diabetes by lowering caloric intake and preventing the metabolic effects of consuming liquid sugar (78). To enhance diabetes prevention and control, strategies to increase clean water availability and consumption should be coupled with strategies that reduce SSB availability, with the overall goal of promoting water consumption and reducing consumption of added sugars.

SSB represent the largest single source of added sugar in average American diets (30–40%) and by themselves account for 50–90% of the recommended daily limit of added sugars (79). Moreover, many Americans consume well above the average amount, placing them at especially high risk for T2D. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. children and youth consume at least one SSB per day, 1 in 5 consumes two SSB per day, and 1 in 10 consumes three or more SSB per day. Highest intake levels are observed among adolescents, groups with lower socioeconomic status, and non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (80,81). Among those who drink ≥1 SSB per day, calories from SSB alone exceed the recommended daily limit for added sugars and often exceed 25% of total daily calories. SSB consumption is associated with T2D, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality (82). Diabetes risk resulting from SSB consumption is a consequence of not only excess caloric intake but also unique effects of added sugars on metabolism. Consuming one SSB per day increases risk of T2D by about 20%. There is an even greater risk among those who consume more than one SSB per day (83). In the U.S., SSB consumption alone is projected to account for 1.8 million new cases of T2D over the next 10 years. The percentage of cases attributable to SSB is much higher in low-income populations and communities of color, and SSB consumption is a significant contributor to race/ethnicity-, education-, and income-related disparities in diabetes (84).

While numerous public health associations and specialty medical organizations have concluded that consuming SSB contributes to T2D, the beverage industry has funded research and campaigns to dispute these conclusions (85–87). At the same time, the U.S. government has not issued scientific reports or clear guidance to the public about the health hazards of SSB consumption. This has undermined the ability of clinicians to effectively guide people with diabetes in the prevention and treatment of diabetes. In addition, federal agencies largely fail to call out SSB as a health hazard in their public communications. Recommendations to reduce or eliminate SSB from the daily diet are absent from even the CDC’s National Diabetes Prevention Program curriculum (88).

Many nongovernmental health organizations have recommended limiting intake of SSB through communication campaigns, implementing warning labels, restricting access to SSB in schools, raising the price of SSB, and restricting sales in the workplace (89). A study of a workplace SSB sales ban by a large employer found that, among employees who were daily SSB consumers (≥12 oz/day), mean daily intake decreased by approximately 50% 10 months after the ban, and reductions in SSB intake correlated with improvements in waist circumference and insulin sensitivity (90). The intervention was also found to be cost saving to the employer (91). Based on the evidence, health systems around the country are beginning to restrict SSB sales.

Increasing the price of SSB with excise taxes of as little as 1 cent per ounce (about 10% of the price) has been shown to reduce SSB consumption by about 20% and raise substantial revenue to fund health promotion activities (92,93). Despite the health benefits of reductions in SSB consumption, the beverage industry has opposed taxation and has lobbied for state preemption laws to make SSB taxation unlawful at county and municipal levels (94). It has been estimated a federal SSB tax of only one penny per ounce would generate about $7 billion per year (95). Over time, such a tax would generate at least $80 billion and save $55 billion in direct health care costs (96).

The NCCC concluded that all relevant federal agencies should promote the consumption of water and reduce consumption of SSB in the U.S. population and that they employ all the necessary tools to achieve these goals, including education, communication, accessibility, water infrastructure, and SSB taxation. The NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

NCCC recommendations related to consuming water over SSB

| Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| USDA, Department of Education | Child nutrition programs should be a conduit for education to promote consumption of water and reduce consumption of SSB. The USDA should encourage hydrating with water instead of SSB and provide safe water education in WIC nutrition education and in childcare settings. Congress should harness the Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act to strengthen existing water provisions for school nutrition programs. |

| HHS | The HHS should commission a scientific report under the joint auspices of the U.S. Surgeon General, the CDC, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to summarize and present a synthesis of the evidence regarding the causal relationship between SSB consumption and obesity and type 2 diabetes. The report should be authored by experts in diabetes and clinical medicine, nutrition and metabolism, epidemiology and public health, and health disparities; authors should be free of any conflicts of interest related to the food and beverage industry. |

| HHS | The CDC and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases should develop and implement a national campaign and associated materials both to promote consumption of water and to reduce consumption of SSB as a strategy to promote overall health, including the prevention of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The CDC should also include such messages across all its relevant programs, including the National Diabetes Prevention Program and its associated Diabetes Prevention Program curriculum. |

| Department of Treasury | Similar to the federal tobacco tax, the Department of the Treasury should impose an excise (not sales) tax on SSB to cause at least a 10–20% increase in their shelf price. The revenues generated should be reinvested to promote the health of those communities that bear a disproportionate burden of type 2 diabetes (for example, promote child nutrition and improve access to clean water in low-income communities and communities of color). This federal SSB tax should not preempt state or local authorities from levying their own additional excise tax on SSB. |

| HHS | The HHS should serve as a federal model by 1) ensuring onsite access to safe, clean, and appealing drinking water; 2) restricting the sale of SSB in HHS-owned or HHS-leased offices, workplaces, and health care facilities; and 3) measuring the impact of these interventions on employee behavior and diabetes-related outcomes through voluntary participation in an evaluation of the model. |

| All agencies | All agencies should promote drinking water and reduce SSB consumption within their own organizations and through the grants and programs they fund or administer. All agencies should increase access to free, clean, and appealing sources of drinking water for their employees and visitors and develop procurement and other policies that curb the availability and sale of SSB to their employees and visitors. |

| Office of the U.S. Trade Representative | The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative should ensure that all international trade agreements allow for the taxation of SSB and front-of-package health advisory labels and icons (see also FDA recommendations in Table 3). |

HHS, Department of Health and Human Services.

FDA: Food and Beverage Labeling and Claim Requirements

The general public, especially those of lower educational and income status, is frequently misinformed about the nutritional value and health risk of foods and beverages (97), especially processed and packaged foods. Current labeling regulations are inadequate to identify risk and enable individuals to reduce consumption of foods and beverages that can lead to a higher burden of diabetes. Inaccurate and misleading marketing claims about the health benefits of products, combined with a federal nutrition label that requires high levels of scientific numeracy and health literacy by consumers, contribute to this problem (98). The lack of focused efforts by the FDA to enact programs and policies to prevent and control diabetes has made the work of many other federal health agencies, including the CDC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and Health Resources and Services Administration, more challenging and more costly.

Evidence from around the world suggests that food and beverage labeling that is clearer, more direct, and more compelling than that required by the FDA can improve dietary quality at individual and population levels (99–101) by changing consumer purchasing patterns and encouraging product reformulations by industry. To fulfill one of the FDA’s goals of supporting informed consumer decision making, the agency should ensure that food labels are truthful, not misleading, and provide clarity for consumers seeking a healthy diet. For example, the FDA should enhance regulations to ensure that objective, science-based standards are used when products use the term “whole grain” (102) and provide clarity around labels such as “toddler milks,” “transition formulas,” and “recommended” or “necessary” for these products. The FDA should also mandate scientific evidence for all health claims and require disclaimers that such products are not intended for children aged <12 months or as a substitute for breastmilk or infant formula (103,104). Additionally, a new requirement around the inclusion of “added sugars” is needed. Existing regulations disqualify the use of health claims or qualified health claims if a product contains excess levels of total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, or sodium (98). Products with excess levels of added sugars should be added to that list.

The NCCC concluded that the FDA should improve its food and beverage labeling regulations that influence both consumer behavior and food and beverage industry practices to better prevent and control diabetes. The NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

NCCC recommendations related to food and beverage labeling, marketing, and advertising

| Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| FDA | In communicating added sugar content contained in products in the revised Nutrition Facts Label (and in the Recommended Daily Allowance), use teaspoon units in addition to grams to enable consumers to estimate their added sugar intake relative to daily limits |

| FDA | Implement a robust, multilingual communication campaign to improve awareness of the new labeling on added sugar and the rationale for the labeling (highlighting the potential harms of consuming excess added sugars) |

| FDA | Update policies and regulations to prevent industry claims on food and beverage products that mislead U.S. consumers to believe that unhealthy foods are healthy |

| FTC | Should be provided the authority, mandate, and requisite resources to 1) create guidelines and rules regarding the marketing and advertising practices of the food and beverage industry and associated communication networks and platforms targeted to children younger than 13 years old; 2) restrict industry practices based on these rules; 3) fully monitor these practices; and 4) enforce such rules |

FTC: Commercial Advertising and Marketing of Unhealthy Foods and Beverages to Children

Over the last few decades, rates of T2D have been increasing among U.S. youth of color, with rates tripling among certain Native American youth, doubling among Black youth, and increasing up to 50% among Latinx and Asian/Pacific Islander youth (47). The expansion of the T2D epidemic into children and adolescents is largely a result of a food environment that increasingly promotes unhealthy dietary patterns. The unfettered advertising and marketing of what is commonly described as “junk food” (high-calorie, high-sugar, high-sodium, nutrient-poor foods) and SSB to children through television, film, social media, and other Internet platforms, including marketing campaigns targeting children of color, have been shown to be drivers of the consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages among children (105). Children and preteens are especially vulnerable to marketing and advertising as they lack the skills to detect if and when they are being deceived (106).

In their efforts to prevent diabetes in young people, many countries have instituted regulations and/or bans on the marketing of unhealthy food to children. These strategies can reduce children’s exposure to unhealthy food advertisements and reduce their consumption of SSB (100).

Extensive work by the FTC in the 1970s, in collaboration with other agencies, reported and monitored industry practices that were contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemics in children and adolescents. The FTC was subsequently prohibited from regulating the practices of advertisers or their communication platforms to protect children from such practices (106). Specifically, the FTC was not allowed to create guidelines or promulgate regulations through notice-and-comment rulemaking regarding food and beverage advertising to children; restrict commercial advertising and marketing to children by advertisers, communication networks, and online platforms of those foods and beverages that contribute to unhealthy dietary patterns; or to monitor the practices of food and beverage advertisers and any associated communication networks and online platforms by routinely accessing marketing and advertising information. The food and beverage industry’s commitment to self-regulate what and how it markets to children is widely acknowledged to have failed to reverse or change these marketing practices (107).

The NCCC’s recommendations on food and beverage marketing and advertising to prevent children’s exposure to, and consumption of, calorie-dense and nutrient-poor foods and beverages that can lead to T2D are listed in Table 3.

Department of Labor: Breastfeeding to Reduce the Risk of Diabetes Among Mothers and Their Children

Breastfeeding provides both short-term and long-term health benefits for babies and mothers. Breastfeeding is independently associated with lower odds of type 1 diabetes and lower odds of obesity in offspring. Women who breastfeed have a 30% reduction in the risk of developing diabetes and a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and breast and ovarian cancer (108). These benefits are associated with greater breastfeeding intensity (proportion of infant feedings from breast milk) and duration, with an apparent threshold at 3 to 6 months’ duration.

Over the past 10 years, effective breastfeeding promotion policies and programs at federal, state, and community levels have been guided by strategies outlined in the 2011 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. These policies and programs have helped improve overall breastfeeding rates. One example is the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for WIC, which serves more than half of the infants born in the U.S. (61). WIC works to ensure that mothers and families who utilize its services understand the benefits of breastfeeding and receive support to achieve their breastfeeding goals. WIC provides access to trained breastfeeding staff, the WIC Peer Counseling Program, free classes on newborn behavior and breastfeeding, and the provision of breast pumps for mothers returning to school or work.

Currently, four of five U.S. mothers begin breastfeeding at the birth of their infants; however, the proportion who breastfeed quickly decreases such that fewer than half of infants are exclusively breastfed at 3 months of age (109,110). Moreover, there are marked racial and ethnic, socioeconomic, geographic, and occupation-related disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration (111). These factors must be addressed to ensure that all mothers and families can reach their breastfeeding goals and experience the health benefits, including reduced risk of diabetes.

A leading reason why mothers, and particularly low-income mothers, stop breastfeeding is the need to return to work. A recent CDC study found that only about half of worksites offer lactation support for breastfeeding mothers (109,112). Paid maternity leave for at least 3 months is associated with breastfeeding duration. Women who return to work at or after 13 weeks have two to three times higher odds of breastfeeding beyond 3 months (113) and nearly twofold greater odds of breastfeeding for at least 6 months.

The NCCC concluded that federal agencies should promote and support breastfeeding to 1) increase breastfeeding rates; 2) enhance the intensity and duration of breastfeeding among mothers who breastfeed; and 3) reduce disparities in breastfeeding rates, duration, and intensity. Additional funding should be provided for federal programs that promote and support breastfeeding to overcome persistent societal and employment-based obstacles to breastfeeding. The NCCC further recommended that the CMS incentivize hospitals and facilities providing maternal and newborn services to implement evidence-based policies, practices, and procedures proven effective in promoting breastfeeding. The NCCC’s specific recommendations related to breastfeeding are in Table 4.

Table 4.

NCCC recommendations related to workplace, ambient, and built environments

| Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Department of Labor | Expand existing federal protections for mothers in the workplace, including mothers covered under the Fair Labor Standards Act (non-salaried employees) as well as those who are not covered under the Fair Labor Standards Act (salaried employees) |

| Department of Labor | Develop and disseminate resources to help employers comply with federal law requiring them to provide the time and a place for nursing mothers to express breast milk |

| Department of Labor | Implement a monitoring system to ensure that employers are complying with federal law that requires they implement lactation support programs |

| HHS, USDA, NIH, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, other federal agencies | Support community-based and community-informed demonstration projects to 1) identify and evaluate the impact of effective, evidence-based breastfeeding support interventions among minority women and women with lower socioeconomic status; and 2) inform implementation and scaling efforts |

| HHS | Update the 2011 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding to reflect the current landscape of breastfeeding research and provide updated breastfeeding policy and program guidance for the new generation of health care providers, public health officials, women, and families |

| HHS | Enact and adequately fund a Medicaid incentive payment mechanism to incentivize hospitals and facilities that they provide maternal and newborn services to implement and demonstrate adherence to evidence-based policies, practices, and procedures proven effective in both initiating and increasing the duration of breastfeeding (for example, the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding framework developed by the World Health Organization) |

| U.S. Congress | Enact national maternity leave legislation to provide mothers with up to 3 months of paid leave, which has been shown to both increase rates of breastfeeding initiation and enhance the duration of breastfeeding; the paid leave provided under this legislation would be distinct from unpaid leave available to employees through the Family and Medical Leave Act |

| EPA, other agencies | Limit the extent to which federal agency work contributes to individual- and population-level exposure to environmental pollutants and contaminants associated with diabetes and/or its complications; the EPA and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences should ensure that environmental protections are in place to limit individual-level and population-level exposure and implement abatement measures, prioritizing those exposures that contribute to diabetes-related disparities |

| All federal agencies, particularly DOT and HUD | Modify policies, practices, regulations, and funding decisions related to the built environment to prevent diabetes and diabetes complications by enhancing increasing walkability, green space, physical activity resources, and active transport opportunities; priority should be given to those regions and projects that could mitigate the effects of unhealthy built environments on diabetes-related disparities |

| HUD | Expand federal housing assistance programs to allow access for more qualifying families, such that over a 20-year period, all those who qualify can access subsidized or public housing |

| IRS | Incentivize developers to place new housing units in areas of low poverty, as data show that moving people from areas of high to low poverty favorably affects prevalence of diabetes |

| IRS | Mandate that states include neighborhood health parameters (such as availability of health care services, transportation, employment opportunities, education opportunities, food availability, and physical activity resources) in the required IRS Qualified Allocation Plan criteria |

| IRS | Establish a means to fund or subsidize cost of embedding health services (if needed) in housing developments to incentivize committing space or employing unused space for such services in their plans |

| HUD | Broaden implementation of indoor smoke-free policies to include subsidized multiunit housing, require that multiunit housing adopt smoke-free policies to provide access to cessation resources, and, in collaboration with the CDC Office on Smoking and Health, work to align these policies with its related policies in public housing to ensure that loss of housing is not an unintended consequence |

EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; HHS, Department of Health and Human Services.

EPA, HUD, and DOT: Ambient and Built Environments

Attributes of the ambient and built environments are influenced by federal policies and have substantial population-level impacts on the risk of developing diabetes and its complications. To date, however, the federal agencies and departments whose work affects the ambient and built environments have not issued policies or established programs to evaluate how their work may influence diabetes in the U.S. and have not coordinated their efforts with health-related agencies working on diabetes prevention and control.

Accumulating evidence links diabetes to ambient environmental factors such as air pollution, water contamination, and chemicals associated with metabolic and endocrine dysfunction and diabetes (114). Pollutants and contaminants include 1) particulate matter and nitrogen oxides in the air; 2) heavy metals (arsenic, lead, and uranium) in water; and 3) endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including polychlorinated biphenyls, organochlorine pesticides, bisphenol A, phthalates, and possibly per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances present in food wrappers, clothes, stain-resistant furniture and carpets, personal care products, and cosmetics (115–117). Differences in exposure to such toxins is an underappreciated contributor to racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in diabetes (118–120).

With respect to the built environment, area-level attributes such as walkability, green space, urban sprawl, physical activity resources, and opportunities for active transport have also been shown to be determinants of T2D risk and diabetes complications (121–124), operating in part through differences in levels of physical activity and sedentariness. In addition, the built environments with higher concentrations of Latinos, African Americans, American Indians, and low-income individuals have been shown to be less health promoting than those of other groups, a phenomenon that also contributes to disparities in diabetes and its complications.

The NCCC concluded that all federal agencies whose work influences the ambient (air, water, land, and chemical) and built environments should modify their policies, practices, regulations, and funding decisions to lead to environmental changes to prevent and control diabetes. The NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 4.

HUD and IRS: Housing Policy

Homelessness, housing instability, and poor-quality housing increase the risk for diabetes (125) and impairs diabetes management among those with diabetes (126,127). The federal government influences housing through HUD and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). HUD subsidizes housing through public authority-owned housing (>2 million people) and the housing voucher program (∼5 million people) for privately owned subsidized housing (commonly known as “Section 8 housing”). However, fewer than one in five families (17%) eligible for public or subsidized housing ever receive these services (128).

IRS manages the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program, which gives tax credits to developers who build low-income, subsidized, or mixed housing. States use a process called a Qualified Allocation Plan (129) to choose which projects receive the low-income tax credits. This process scores a project based on a set of mandatory criteria set up by the IRS and any supplemental criteria that individual states choose to add. Currently, the mandatory IRS criteria address the location of the property, characteristics of the population that will move into the housing, types of properties existing on the site, and energy efficiency. However, there are no health-related attributes to the IRS criteria.

Housing plays an important role in clinical outcomes. Families that need to spend >30% of their incomes on housing have difficulty affording food, medications, and medical care. A large, randomized trial sponsored by HUD (Moving to Opportunity) demonstrated that moving families from public housing in a high-poverty zone to subsidized housing in a low-poverty zone is associated with lower diabetes incidence (130).

Exposure to tobacco smoke elevates the risk of T2D and dramatically increases the risk of complications and death among people with diabetes (131). Diabetes prevalence is nearly twice as high among people living in public housing (17.6%) as in the general population (9.4%) (132). Smoking rates and rates of exposure to secondhand smoke are also higher among people with diabetes and prediabetes, especially those who are poor, have limited education, and are Black (133–135). To mitigate tobacco-related disparities, in July 2018 HUD implemented a mandatory smoke-free policy (136) applicable to all public housing authority-owned housing. However, this policy does not apply to Section 8 federally subsidized housing, leaving these residents unprotected from secondhand smoke. Expanding HUD’s smoke-free policy to all federally subsidized housing units could have population-level benefits by reducing diabetes incidence, diabetes-related complications, and diabetes-related deaths.

The NCCC concluded that, to reduce T2D incidence and diabetes complications, housing opportunities for low-income individuals and families need to be expanded, and that such individuals and families should be housed in health-promoting environments. The NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 4.

NIH, CDC, USDA, and Other Federal Agencies: Research to Inform Population-Level Diabetes Prevention and Control

It has been nearly 50 years since Congress passed the National Diabetes Research and Education Act (137) to coordinate and expand the government’s research and prevention efforts related to diabetes. This law mandated that the NIH establish a National Commission on Diabetes to develop a long-range plan to combat diabetes (138), with an emphasis on creating a coordinated, interdisciplinary research program. The plan and subsequent action led to a world-class research program that has resulted in a deeper understanding of the epidemiology of diabetes, discoveries of diabetes causes and its complications, and substantial advances in clinical prevention and treatment. This research has focused on understanding the basic biology of diabetes and its complications and intervening at the individual patient level in clinical settings. More recently, the NIH, through the Diabetes Mellitus Interagency Coordinating Committee, updated its strategic plan to guide diabetes-related basic, clinical, and translational research and nutrition research (139). These investments have helped advance the field and have informed and improved the clinical prevention and care of individuals at risk for or with diabetes.

However, since the National Commission on Diabetes issued its report in 1975, our understanding of the diabetes epidemic has evolved. Now there is a greater appreciation of the interactions between social and environmental conditions, stress, and health behaviors and diabetes incidence, diabetes complications, and health disparities. The population-level burden of T2D is, however, a consequence of the unhealthy social and environmental conditions prevalent in U.S. society. There is an urgent need to leverage and coordinate research across a range of federal non–health-related departments and agencies to answer critical questions related to the social and environmental drivers of diabetes and the effects of social and environmental policy changes and related interventions on diabetes and its outcomes. Resultant discoveries have the potential to benefit not only those at risk for and with diabetes but also the general public. Such research will also help ensure that clinicians can provide high-quality, integrated clinical care and that people with diabetes can successfully self-manage diabetes.

The NCCC concluded that federal investments in research and discoveries are needed to generate population-level benefits in the prevention and control of T2D, with a particular focus on elucidating and changing the social and environmental conditions associated with greater risk of diabetes and its complications. The NCCC’s specific recommendations are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

NCCC recommendations related to population-level research

| Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| HHS (NIH and CDC) | Support large-scale natural experiment research, including cost-effectiveness analysis, to inform the evidence base related to social and environmental policies that prevent and control type 2 diabetes; special focus should be paid to “health-in-all policies” types of interventions relevant to non–health agency activities and other public health (nonclinical) interventions |

| HHS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation) or alternative federal entity | Support demonstration projects in collaboration with non–health agencies related to influencing social determinants of health and reducing diabetes risk and diabetes control and complications (for example, USDA SNAP interventions, HUD housing interventions, EPA fresh water interventions, and DOT walkability interventions) |

| HHS (NIH and CDC), USDA, DOT, HUD | Investments in research training need to be made to enhance the workforce skilled in the competencies needed to carry out health impact assessments and related simulation work |

| HHS (NIH) | Expand the NIH initiative on precision nutrition to 1) include clinical trials that can inform critical population health questions related to which foods, beverages, ingredients, and additives promote/prevent the development of type 2 diabetes; 2) include studies of communication interventions and (counter)marketing practices to inform which practices work best for which subpopulations with respect to changing dietary patterns to prevent type 2 diabetes and which practices elevate diabetes risk; and 3) broaden the definition of “precision” to go beyond targeting the individual to include targeting cultural and geographic entities (neighborhoods) |

| HHS (NIH) and USDA | Encourage that nutrition and metabolic research accurately quantify water intake and use this information to better study the associations between water consumption and health across the life span; USDA should develop methods to incorporate water consumption into USDA Food Patterns (water is a beverage that currently is not a contributor to USDA food groups or subgroups) |

| HHS (NIH) | Support research (in collaboration with other agencies) to better understand the role of 1) exposures related to environmental pollutants, toxins, contaminants, unclean water, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals on metabolic function and diabetes risk; and 2) life course trauma (including interpersonal violence, discrimination, racism, and disability) on metabolic function and diabetes risk and associated interventions to reduce exposure to such trauma and/or mitigate the effects of trauma on diabetes outcomes |

HHS, Department of Health and Human Services.

Conclusions

The NCCC’s guiding socioecological framework (Fig. 1) (9,10), and the population-level recommendations that flowed from this framework, represent a major shift in how the federal government can address the diabetes epidemic. While adopting these recommendations could significantly reduce diabetes incidence, complications, and costs in the U.S., substantial political resolve will be needed to translate recommendations into policy. Some of the NCCC recommendations would require new legislation; others, however, require only administrative action (e.g., rulemaking) at the level of the agency or department.

How clinicians and public health experts understand the diabetes epidemic has evolved since the last federal diabetes report was issued in 1975. In part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the critical importance of unhealthy social and environmental conditions in influencing the burden and distribution of disease is now widely acknowledged. As a result, we believe that policymakers and more Americans are recognizing how favorable social and environmental conditions promote health, and many have begun to reckon with the consequences of the nation’s failure to implement an all-of-government approach to disease prevention and control. Of note, a substantial number of the NCCC’s population-wide recommendations would also generate broad public health benefit beyond diabetes (e.g., cardiovascular disease, obesity, asthma, and communicable disease). By recommending a health-in-all-policies and an equity-based approach to governance, the NCCC Report to Congress and the Secretary of Health and Human Services has the potential to contribute to meaningful change across the diabetes continuum and beyond.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The NCCC acknowledges Alicia A. Livinski and Nancy L. Terry, biomedical librarians from the National Institutes of Health Library, Division of Library Services, Office of Research Services, who performed the literature searches. The NCCC also thanks Yanni Wang (International Biomedical Communications) and Heather Stites (University of Michigan School of Medicine) for their editorial assistance.

Funding. The NCCC was supported through a Joint Funding Agreement among eight federal agencies: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Indian Health Service (IHS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Office of Minority Health (OMH). The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP), and the Office on Women’s Health (OWH) provided management staff and contractor support.

The funders had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Health and Human Services or other departments and agencies of the federal government.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented at the 82nd Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, New Orleans, LA, 3–7 June 2022.

Footnotes

C.P. was the Designated Federal Officer for the National Clinical Care Commission. All other authors were members of the National Clinical Care Commission.

Retired

This article is part of a special article collection available at https://diabetesjournals.org/collection/1586/The-Clinical-Care-Commission-Report-to-Congress.

References

- 1. Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, Chin MH, Gary-Webb TL, Navas-Acien A, et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care 2021;44:258–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bagby SP, Martin D, Chung ST, Rajapakse N. From the outside in: biological mechanisms linking social and environmental exposures to chronic disease and to health disparities. Am J Public Health 2019;109(S1):S56–S63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGowan PO, Matthews SG. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids, and developmental programming of the stress response. Endocrinology 2018;159:69–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Green L, Ashton K, Bellis MA, Clemens T, Douglas M. Health in all policies—a key driver for health and well-being in a post-COVID-19 pandemic world. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hessler D, Bowyer V, Gold R, Shields-Zeeman L, Cottrell E, Gottlieb LM. Bringing social context into diabetes care: intervening on social risks versus providing contextualized care. Curr Diab Rep 2019;19:30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Edwards ST. Addressing health-related social needs: value-based care or values-based care? J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1916–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barnard LS, Wexler DJ, DeWalt D, Berkowitz SA. Material need support interventions for diabetes prevention and control: a systematic review. Curr Diab Rep 2015;15:574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kung A, Cheung T, Knox M, et al. Capacity to address social needs affects primary care clinician burnout. Ann Fam Med 2019;17:487–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Clinical Care Commission . Report to Congress. Accessed 9 February 2022. Available from https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- 10. Herman WH, Bullock A, Boltri JM, et al. The National Clinical Care Commission Report to Congress: background, methods, and foundational recommendations. Diabetes Care 2023;46:e14–e23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002;288:475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bailey SC, Brega AG, Crutchfield TM, et al. Update on health literacy and diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2014;40:581–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zoellner J, You W, Connell C, et al. Health literacy is associated with healthy eating index scores and sugar-sweetened beverage intake: findings from the rural Lower Mississippi Delta. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1012–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seligman HK, Wang FF, Palacios JL, et al. Physician notification of their diabetes patients’ limited health literacy. A randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:1001–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seligman HK, Berkowitz SA. Aligning programs and policies to support food security and public health goals in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:319–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berkowitz SA, Karter AJ, Corbie-Smith G, et al. Food insecurity, food “deserts,” and glycemic control in patients with diabetes: a longitudinal analysis. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1188–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ippolito MM, Lyles CR, Prendergast K, Marshall MB, Waxman E, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and diabetes self-management among food pantry clients. Public Health Nutr 2017;20:183–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, Wolf MS. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:1227–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rasmusson G, Lydecker JA, Coffino JA, White MA, Grilo CM. Household food insecurity is associated with binge-eating disorder and obesity. Int J Eating Disorders 2019;52:28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gucciardi E, Vahabi M, Norris N, del Monte JP, Farnum C. The intersection between food insecurity and diabetes: a review. Curr Nutrition Rep 2014;3:324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:6–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Accessed 8 February 2022. Available from https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap

- 23. United States Code . The Food Stamp Act of 1964, PubLic Law 88-525 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carlson S, Keith-Jennings B. SNAP Is Linked with Improved Nutritional Outcomes and Lower Health Care Costs. Washington, DC, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018 Available from https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/1-17-18fa.pdf

- 25. Leung CW, Ding EL, Catalano PJ, Villamor E, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Dietary intake and dietary quality of low-income adults in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:977–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fang Zhang F, Liu J, Rehm CD, Wilde P, Mande JR, Mozaffarian D. Trends and disparities in diet quality among US adults by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation status. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e180237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Food and Nutrition Service . Barriers That Constrain the Adequacy of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Allotments. Accessed 8 February 2022. Available from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/barriers-constrain-adequacy-snap-allotments

- 28. Hasche J, Ward C. Diabetes occurrence, costs, and access to care among Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and over. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Data Highlight 2017. Available from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/research/mcbs/downloads/diabetes_databrief_2017.pdf

- 29. Wheaton L, Lynch V, Johnson M. The Overlap in SNAP and Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility, Findings from the Work Support Strategies Evaluation 2013. Available from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/86971/overlap_in_snap_and_medicaidchip_eligibility.pdf

- 30. Auter Z. Medicaid Population Reports Poorest Health. Gallup News Service 2017. Available from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=126793906&site=ehost-live

- 31. Mozaffarian D, Liu J, Sy S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives and disincentives for improving food purchases and health through the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): a microsimulation study. PloS Med 2018;15:e1002661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garasky S, Mbwana K, Romualdo A, Tenaglio A, Roy M. Foods Typically Purchased by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Households. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2016. Available from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/foods-typically-purchased-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap-households

- 33. USDA . Animal Health. Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program 2021. Washington, DC, National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Available from https://nifa.usda.gov/topic/animal-health

- 34. Klerman JA, Bartlett S, Wilde P, Olsho L. The short-run impact of the healthy incentives pilot program on fruit and vegetable intake. Am J Agric Econ 2014;96:1372–1382 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choi SE, Seligman H, Basu S. Cost effectiveness of subsidizing fruit and vegetable purchases through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:e147–e155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee . Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and Secretary of Health and Human Services 2020. Accessed 8 February 2022. Available from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/2020-advisory-committee-report

- 37. Basu S, Seligman HK, Gardner C, Bhattacharya J. Ending SNAP subsidies for sugar-sweetened beverages could reduce obesity and type 2 diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1032–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harnack L, Oakes JM, Elbel B, Beatty T, Rydell S, French S. Effects of subsidies and prohibitions on nutrition in a food benefit program: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 176:1610–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Commission on Hunger to Congress and the Secretary of the Department of Agriculture . Freedom from hunger: an achievable goal for the United States of America: recommendations of the National Commission on Hunger to Congress and the Secretary of the Department of Agriculture, 2015. Available from https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/freedom-from-hunger-an-achievable-goal-for-the-united-states-of-america/

- 40. Blumenthal SJ, Hoffnagle EE, Leung CW, et al. Strategies to improve the dietary quality of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) beneficiaries: an assessment of stakeholder opinions. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:2824–2833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Basu S, Seligman HK, Gardner C, Bhattacharya J. Ending SNAP subsidies for sugar-sweetened beverages could reduce obesity and type 2 diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. National Institute of Food and Agriculture . Supplemental Nutrition Education Program–Education (SNAP-Ed). Washington, DC, National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Accessed 8 February 2022. Available from https://nifa.usda.gov/program/supplemental-nutrition-education-program-education-snap-ed

- 43. Food Research and Action Center . Replacing the Thrifty Food Plan in Order to Provide Adequate Allotments for SNAP Beneficiaries. Washington, DC, Food Research and Action Center, 2012. Available from https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/thrifty_food_plan_2012.pdf

- 44. Caswell JA, Yaktine AL. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Examining the Evidence to Define Benefit Adequacy. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2013. Accessed 8 February 2022. Available from https://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13485 [PubMed]

- 45. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th Ed. 2020. Available from http://DietaryGuidelines.gov

- 46. Hurdles TM. Barriers to Receive SNAP Put Children’s Health at Risk. Philadelphia, PA, Drexel University Center for Hunger-Free Communities, 2021. Available from https://drexel.edu/hunger-free-center/research/briefs-and-reports/too-many-hurdles/

- 47. FitzSimmons CW, Weill JD, Parker L. Barriers That Prevent Low-Income People From Gaining Access to Food and Nutrition Programs. Washington, DC, Food Research and Action Center. Available from https://www.hungercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Barriers-to-Food-and-Nutrition-Programs-FRAC.pdf

- 48. Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, et al. Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002–2012, 2017;376:1419–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ferrara A, Kahn HS, Quesenberry CP, Riley C, Hedderson MM. An increase in the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: Northern California, 1991-2000. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:526–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamad R, Collin DF, Baer RJ, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Association of revised WIC food package with perinatal and birth outcomes: a quasi-experimental study. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:845–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Currie J, Rajani I. Within-mother estimates of the effects of WIC on birth outcomes in New York City. Econ Inq 2015;53:1691–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pan L, Blanck HM, Park S, et al. State-specific prevalence of obesity among children aged 2-4 years enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children–United States, 2010-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1057–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. USDA . USDA to Incentivize Purchase of Fruits and Vegetables Under WIC for 4 Months with American Rescue Plan Funding. Washington, DC, USDA. Accessed 9 February 2022. Available from https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/04/28/usda-incentivize-purchase-fruits-and-vegetables-under-wic-4-months

- 54. Food and Nutrition Service . Implementation of the Extending Government Funding and Delivering Emergency Assistance Act Temporary Increase in the CVV Benefit for Fruit and Vegetable Purchases. Alexandria, VA, Food and Nutrition Service. Accessed 9 February 2022. Available from https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/extending-government-funding-and-delivering-emergency-assistance