Summary box.

Ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity is essential for sustainable development. Given the high burden of complications during the postnatal period, this is a critical phase of the maternal and newborn continuum of care.

Coverage and quality of postnatal care is still suboptimal, particularly in low-income countries. Bridging this gap is necessary for reducing health inequity and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

WHO has released an updated, comprehensive guideline including recommendations addressing maternal care, newborn care, and health systems and health promotion interventions during the postnatal period.

The WHO postnatal care model places the woman-newborn dyad at the centre of care, and recognises a ‘positive postnatal experience’ as a key endpoint for all women, newborns, parents, caregivers and families after birth. It highlights opportunities to improve maternal and newborn health and well-being, support nurturing newborn care, and provide high-quality care within well-functioning health systems.

To fully realise WHO’s vision for care across the pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal continuum, attention on scaling up effective coverage of postnatal care is urged, so that every woman and every newborn receives the quality care they need to survive and thrive.

The postnatal period, defined as the period immediately following the birth of the newborn to 6 weeks (42 days) after birth, is a critical time for women, newborns, parents, caregivers and families.1 Postnatal care services are an essential element of the maternal and newborn care continuum. The care provided during this period contributes to improved maternal and child health and well-being by helping to establish healthy practices, prevent disease, and detect and manage complications. It is key to foster an environment that supports the health, social and developmental needs of the woman, newborn and family unit. Yet, coverage and quality of postnatal care lag substantially behind that of both antenatal and intrapartum care,2 and marked inequities in the use of postnatal care persist.3 In line with the Sustainable Development Goals4 and the Global Strategy for Women Children and Adolescent Health,5 and in accordance with a human rights-based approach, there is a need to broaden the objective of postnatal care to improving quality, not solely coverage and survival.

The WHO has responded to the evolving global maternal, newborn and child health agenda with comprehensive guidelines to improve maternal and newborn care, with particular focus on quality of care; that is, both provision and experience of care within the health system, to support all women, newborns and families to thrive in the short term and longer term.

WHO postnatal care recommendations

In 2022, WHO published 63 recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience.1 This guideline updates and expands on the previous WHO recommendations on postnatal care for mothers and newborns,6 published in 2014, which focused on reducing morbidity and mortality in resource-limited settings in low-income and middle-income countries. The updated guideline now sits together with the 2016 WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience7 and the 2018 WHO recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience,8 to round out WHO’s comprehensive vision for quality care of women and newborns, in which ‘every pregnant woman and newborn receives quality care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period’.9

The postnatal care guideline focuses on the essential care package that all women and newborns should receive during the postnatal period. It addresses two main questions: (1) ‘What are the evidence-based clinical interventions during the postnatal period to improve maternal and newborn health and well-being?’ and (2) ‘What are the evidence-based health systems and health promotion interventions to improve provision, utilisation and experience of postnatal care?’ Prioritised interventions responded to the domains outlined in the WHO quality of maternal and newborn healthcare framework,10 the nurturing care framework,11 and the WHO health systems framework.12

The WHO postnatal care model

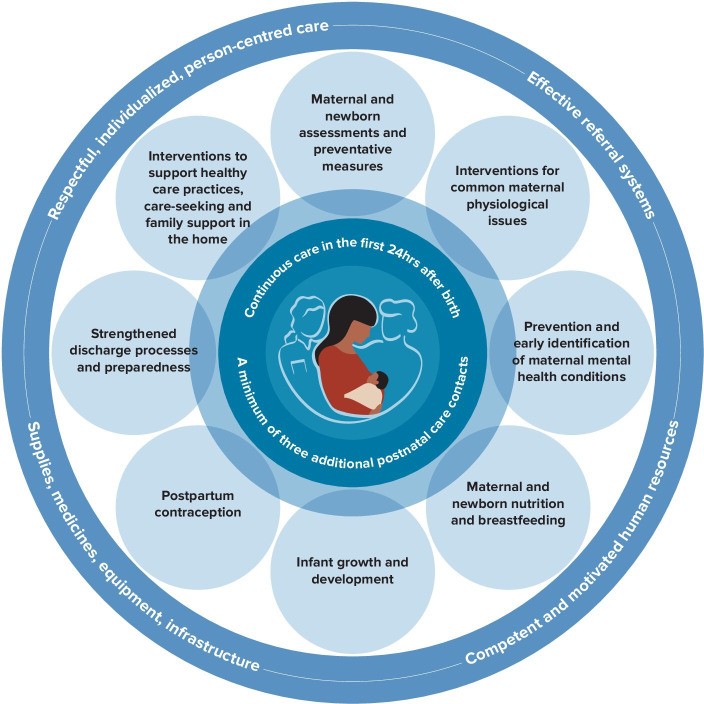

The WHO postnatal care model places the woman-newborn dyad at the centre of care (figure 1), supported by quality care, family support and continued support from health services. Evidence from a qualitative evidence synthesis exploring what matters to women during the postnatal period13 shows that the postnatal period is generally a time of intense joy and happiness, while also characterised by marked changes in self-identity, the redefinition of relationships and opportunities for personal growth, as women adjust to parenthood as individuals within their own cultural context. Pivotal to the postnatal care model is a ‘positive postnatal experience’ (box 1), which is recognised as a significant endpoint for all women, newborns, parents and families after birth, and which lays the platform for improved short- and longer-term health and well-being. As stated in the guideline, the terms woman, mother, partner, parents and caregivers have been used, in an attempt to promote inclusivity of all individuals who have given birth, in recognition of the diverse roles of all individuals involved in providing care and support during the postnatal period, and of diverse couples and families. Families can be an important support for women and parents and have a vital role in maternal and newborn health.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the WHO postnatal care model.

Box 1. Positive postnatal experience1.

A positive postnatal experience is defined as one in which women, partners, parents, caregivers and families receive information and reassurance in a consistent manner from motivated health workers. Both the women’s and babies’ health, social and developmental needs are recognised, within a resourced and flexible health system that respects their cultural context.

To enable the provision of the essential postnatal care package, the foundation of the model is the recommendation for at least four postnatal care contacts. First, ongoing care and monitoring in the first 24 hours after birth is essential, as part of continuous care in the health facility or home. A minimum 24-hour length of stay following a facility-based vaginal birth is recommended to allow sufficient time to complete comprehensive maternal and newborn assessments, and to provide orientations for the transition of the woman and the baby to care in the home (see below). The second contact occurs between 48 and 72 hours after birth; the third between days 7 and 14, and the fourth during week six after birth. Postnatal care contacts can occur at home or in outpatient services. Where feasible, the contact during the first week is recommended to occur at home, to allow the health worker to provide support in the home environment. The model recognises that additional contacts may be required depending on individual circumstances.

Within the postnatal care model, ‘contact’ entails active interaction between women, newborns, parents and health workers. Every contact should include respectful, individualised, and person-centred provision of essential clinical practices, information, and psychosocial and emotional support, provided by kind, competent and motivated health workers who are working within a well-functioning health system. Effective referral systems are also critical, ensuring safe and timely referrals and transport where needed.

Critical to the model are expanded discharge criteria and strengthened preparation of women, newborns, parents and families, to support the transition from the facility to the home. These criteria go beyond essential physiological assessment, to assessment of the women’s emotional well-being; the skills and confidence of the woman to care for herself; the skills and confidence of parents and families to care for the newborn; the home environment; and other factors that may affect the capacity for care practices in the home, care-seeking and continued postnatal follow-up.

The guideline includes several pivotal recommendations, expanding the postnatal care agenda. For the first time, WHO has recommended universal screening of newborns for eye abnormalities, hearing impairment, and neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia. Maternal mental health is also prioritised, with universally recommended screening for—and prevention of —maternal depression and anxiety during the postnatal period. Other recommendations in the guideline cover interventions for common physiological signs and symptoms, preventive measures, nutritional interventions and breastfeeding, infant growth and development, and postpartum contraception. Additional health systems and health promotion interventions include midwifery continuity of care, task-sharing, involvement of men and digital targeted client communication. Readers are encouraged to review the recommendations in detail in the guideline document.1

Implementation of the WHO postnatal care model

The release of the new WHO postnatal care recommendations serves as a much-needed call-to-action for renewed focus on postnatal care, globally. While the recommended minimum length of stay in health facilities and schedule of postnatal care contacts are unchanged from 2014, their implementation remains suboptimal. Renewed and strengthened focus is required in these areas, as well as in the care and monitoring of women and newborns in the first 24 hours after birth, and in preparing women and families for discharge and the transition to the home. Careful attention must also be given to the new recommendations addressing newborn screening and maternal mental health. For any screening intervention, effective systems for referral, diagnosis, management and follow-up are needed, as appropriate for the condition and local context. Health workers will require training and supervision to carry out culturally sensitive screening and subsequent management. A phased approach to adoption, adaptation and scale-up may be needed to address new and ongoing barriers to implementation of these recommendations across different contexts.

Health and social policy considerations will provide an enabling environment for implementation of the postnatal care guideline including, among others, the right to health and healthcare, universal health coverage, respectful care, the protection from harmful commercial marketing of breastmilk substitutes, alcohol and tobacco, birth registration, employment rights, and social protection legislation and strategies. National guidelines need to update and integrate new recommendations and programme managers must ensure that systems are in place for training, monitoring, supervision, budgeting, resource acquisition and management, and quality improvement initiatives.

Adaptation of the recommendations and development of implementation tools should consider their integration and alignment with other response strategies in the context of humanitarian crises. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is essential that maternal and newborn health services continue—or are adapted as needed—to mitigate the risks of insufficient postnatal care, which outweigh the risk of coronavirus transmission during healthcare provision.14 15

Implementation efforts also must include raising awareness of the importance of postnatal care, informing women about what each postnatal care contact entails, and of the fundamental human right of women and newborns to receive postnatal care for their health and well-being. Indicators to monitor progress should capture experience of care and well-being, to enable continuous quality improvement.

To fully realise WHO’s vision, attention must now be urgently focused on scaling up effective coverage of postnatal care, so that every woman and every newborn receives the quality postnatal care they need to survive and thrive.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions that many individuals and organisations made to the development of this guideline, including members of the Guideline Development Group and External Advisors who participated in the virtual technical consultations between September 2020 and June 2021. We thank Dr Özge Tuncalp for providing valuable comments on the draft of this commentary. AMW and JPS were independent consultants working with WHO at the time of guideline development.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @aleenawoj, @HRPresearch, @anagportela

Contributors: The idea of this commentary was conceived by MB. AMW wrote the first draft and revised the manuscript with MB and AP. All authors contributed to the content and development of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding: The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and HRP (the UNDP–UNFPA–UNICEF–WHO–World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction), a cosponsored programme executed by the WHO, funded the development of the postnatal care guideline.

Disclaimer: The views of the funding bodies have not influenced the content of this guideline.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

There are no data associated with this commentary.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization . Tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, newborn and child health: the 2017 report. Washington, DC: United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langlois Étienne V, Miszkurka M, Zunzunegui MV, et al. Inequities in postnatal care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:259-270G. 10.2471/BLT.14.140996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [website]. Sustainable Development Goals. Available: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ [Accessed 12 Oct 2022].

- 5.Every Woman Every Child . Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016-2030). New York: Every Woman Every Child, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tunçalp Ӧ, Were WM, MacLennan C, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns-the who vision. BJOG 2015;122:1045–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group . Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Everybody’s business - strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finlayson K, Crossland N, Bonet M, et al. What matters to women in the postnatal period: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS One 2020;15:e0231415. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context. Interim guidance - 1 June 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) . Community-Based health care, including outreach and campaigns, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interim guidance - May 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data associated with this commentary.