Abstract

Background and objective

Liver fibrosis has been considered a predictor of cardiovascular disease. This study aimed to evaluate whether the degree of liver fibrosis is related to post-stroke depression (PSD) at 3 months follow-up.

Methods

We prospectively and continuously enrolled patients with first-ever ischemic stroke from June 2020 to January 2022. Liver fibrosis was measured after admission by calculating the Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) and stratified into two categories (< 2.67 versus ≥ 2.67). Patients with a 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale score > 7 were further evaluated using the Chinese version of the structured clinical interview of DSM-IV, for diagnosing PSD at 3 months.

Results

A total of 326 patients (mean age 66.6 years, 51.5% male) were recruited for the study. As determined by the FIB-4 score, 80 (24.5%) patients had advanced liver fibrosis. During the follow-up, PSD was observed in 91 patients, which accounted for 27.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 25.5%–30.5%) of the cohort.

The prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis was higher in PSD patients than those without PSD (40.0% versus 24.0%; P = 0.006). After adjustment for covariates in the multivariate logistic analysis, advanced fibrosis was significantly associated with PSD (odds ratio [OR], 1.88; 95% CI, 1.03–3.42; P = 0.040). Similar results were found when the FIB-4 was analyzed as a continuous variable.

Conclusions

This study found that advanced liver fibrosis was associated with an increased risk of 3-month PSD. FIB-4 score may be valuable for screening depressive symptoms in ischemic stroke patients.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, Depressive symptoms, Liver fibrosis, Fibrosis-4 index, Risk factor

Introduction

Depression is one of the most common and serious neuropsychiatric sequelae after stroke, which accounts for approximately one-third of acute ischemic stroke survivors [1–3]. Post-stroke depression (PSD) is negatively associated with functional outcomes [4] and strongly related to an increased risk of mortality [5]. A meta-analysis of prospective studies with 4648 stroke patients further suggested that PSD may be an independent predictor of stroke recurrence [6]. Considering the clinical importance of PSD, the Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the AHA/ASA recommended screening for PSD in stroke patients [7]. These results emphasize the urgency to early identify risk factors of PSD, which might have clinical implications for a better understanding of the etiology, early prevention, and intervention of PSD.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is estimated to affect approximately 25% of the adult population globally [8], and has recently been reported as a risk factor for large artery atherosclerosis and small vessel occlusion subtypes of stroke by mendelian randomization study [9]. The fibrosis stage is considered the most deleterious pathological feature of NAFLD [10]. A prospective stroke cohort showed that advanced liver fibrosis is associated with unfavorable long-term prognosis and stroke recurrence [11]. However, although liver fibrosis may not be rare in patients with ischemic stroke, there are few data available regarding the relationship between liver fibrosis and post-stroke affective disorder, especially PSD.

To date, several noninvasive modalities have been developed and established to evaluate the degree of liver fibrosis, including transient elastography and predictive scores [12–14]. Among these clinical scores, Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) is easily obtained from blood test results and is recommended by guidelines to screen for liver fibrosis [15]. In this study, we evaluated the association between liver fibrosis, assessed by the FIB-4 index, and the development of PSD at 3 months in patients with ischemic stroke.

Methods

Study cohort and design

From June 2020 to January 2022, we performed a prospective study to enroll first-ever ischemic stroke patients with symptoms onset < 7 days in Mianyang Central Hospital. All patients met the diagnostic criteria for ischemic stroke according to the World Health Organization criteria [16]. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age < 18 years old; 2) neurological deficits caused by other central nervous system diseases, such as cerebral hemorrhage, brain trauma, brain tumors, or paralysis after seizures; 3) history of dementia, cognitive dysfunction, depression or other psychiatric illness; 4) severe aphasia, dysarthria, understanding or consciousness disturbance that precluded us from performing the psychological evaluations.

Baseline data assessment

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were recorded with a standard case report form after admission, including age, sex, education, body mass index, blood pressure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and coronary heart disease. Stroke severity was measured using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score by trained neurologists at baseline [17]. Stroke etiology was confirmed by the Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria including large-artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolism, small vessel disease, and others [18]. Laboratory tests were conducted within 24 h after admission (including platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], blood glucose, Hypersensitive C-reactive protein [Hs-CRP], and lipid profile). Biomarker levels were measured at our hospital’s laboratory by technicians who were blinded to the clinical data.

Liver fibrosis measurement

The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index was calculated to assess the degree of liver fibrosis for each participant after admission using the following formula: FIB-4 index = [age (years) × aspartate aminotransferase level (U/L)]/{[platelet count (109/L)] × [alanine aminotransferase level (U/L)]1/2}. FIB-4 score is a well-validated and clinically established liver fibrosis index [11]. Based on the FIB-4 score, the severity of liver fibrosis was categorized into 2 groups: < 2.67, without advanced liver fibrosis; and ≥ 2.67, advanced liver fibrosis [19].

Psychological measurement

In this study, we used the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17-HAMD) to assess the depressive symptoms at 3 months follow-up [20]. Patients with 17-HAMD score > 7 were further evaluated for diagnosing PSD according to the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) [21–23]. The psychological evaluations were performed by an experienced clinician who was blind to other clinical and laboratory data.

Statistical analysis

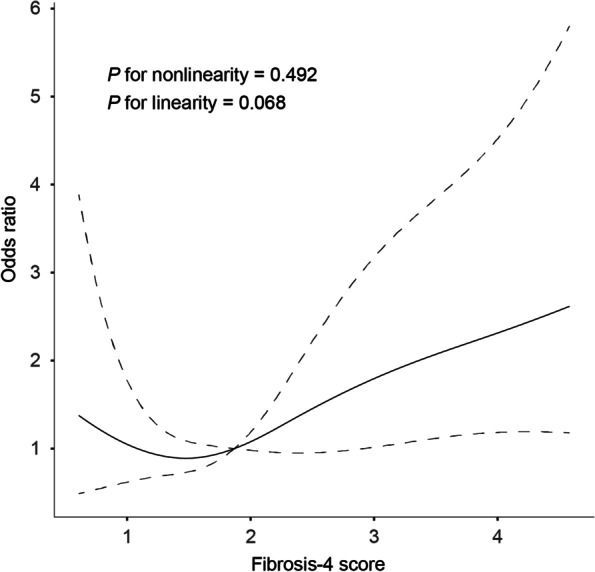

According to the normality of data distribution, continuous variables were demonstrated as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), Categorical variables were summarized as counts and proportions. The differences between the two groups were compared using the Student’s t–test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi–squared test for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to assess variables associated with the presence of PSD. All multivariable analyses were first adjusted for age and sex (Model 1) and additionally adjusted for all variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis (age, sex, education years, diabetes, baseline NIHSS score, and Hs-CRP levels; Model 2). We further evaluated the pattern and magnitude of the association of the FIB-4 index with PSD with restricted cubic splines with 4 knots (at fifth, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles) adjusted for the same potential confounders included in model 2 [24]. The results were expressed as an adjusted odds ratio (OR) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Furthermore, the net reclassification index and integrated discrimination improvement were calculated to estimate the predictive value of adding liver fibrosis status into models 1 and 2, separately. All statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R statistical software version 4.0.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria), and a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 479 patients were screened from June 2020 to January 2022, with 326 patients eligible for the study. The average age of all patients was 66.6 ± 11.3 years and 168 (51.5%) were male. The median (IQR) NIHSS score on admission was 5.0 (2.0, 8.0).

Advanced liver fibrosis in acute ischemic patients

Among these patients, 80 (24.5%) patients had advanced liver fibrosis. The demographic characteristics, clinical data, and laboratory data stratified by the degree of liver fibrosis were presented in Table 1. Compared to participants without liver fibrosis, those with advanced liver fibrosis were older (72.3 ± 8.4 years versus. 64.8 ± 11.5 years, P < 0.001), and had a higher prevalence of hypertension (82.5% versus. 70.4%, P = 0.038), cardioembolism (28.8% versus. 16.3%, P < 0.001) and 3-month PSD (40.0% versus. 24.0%, P = 0.006), and higher levels baseline NIHSS score (median, 6.0 versus. 5.0, P = 0.013).

Table 1.

Baseline data of the included patients stratified by liver fibrosis status

| Variables | Study cohort n = 326 |

With advanced liver fibrosis n = 80 |

Without advanced liver fibrosis n = 246 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, year | 66.6 ± 11.3 | 72.3 ± 8.4 | 64.8 ± 11.5 | < 0.001 |

| Male, % | 168 (51.5) | 45 (56.3) | 123 (50.0) | 0.331 |

| Education < 12 years, % | 172 (52.8) | 45 (56.3) | 127 (51.6) | 0.547 |

| Risk factors, % | ||||

| Hypertension | 240 (73.6) | 66 (82.5) | 174 (70.4) | 0.038 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 83 (25.5) | 22 (27.5) | 61 (24.8) | 0.630 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 69 (21.2) | 20 (25.0) | 49 (19.9) | 0.334 |

| Coronary heart disease | 46 (14.1) | 15 (18.8) | 31 (12.6) | 0.170 |

| Current smoking | 137 (42.0) | 39 (48.8) | 98 (39.8) | 0.161 |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 136.1 ± 19.7 | 136.4 ± 25.7 | 136.2 ± 17.4 | 0.891 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 82.0 ± 9.9 | 81.2 ± 9.5 | 82.3 ± 10.0 | 0.910 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.3 ± 2.5 | 24.1 ± 2.3 | 24.3 ± 2.6 | 0.431 |

| Baseline NIHSS, score | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 0.013 |

| PSD at 3-month, % | 91 (27.9) | 32 (40.0) | 59 (24.0) | 0.006 |

| Stroke subtypes, % | < 0.001 | |||

| arge artery atherosclerosis | 149 (45.7) | 25 (31.3) | 124 (50.4) | |

| Cardioembolism | 63 (19.3) | 23 (28.8) | 40 (16.3) | |

| Small vessel occlusion | 91 (27.9) | 19 (23.8) | 72 (29.3) | |

| Others | 23 (7.1) | 13 (16.3) | 10 (4.1) | |

| Side of infarction, % | ||||

| Left | 165 (50.6) | 43 (53.8) | 122 (49.6) | 0.518 |

| Right | 181 (55.5) | 39 (48.8) | 142 (57.7) | 0.161 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Platelet, 109/L | 183.8 ± 58.2 | 145.9 ± 39.0 | 196.1 ± 58.2 | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate transaminase, U/L | 29.2 ± 19.2 | 41.0 ± 30.6 | 25.3 ± 11.3 | < 0.001 |

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | 32.6 ± 20.4 | 34.4 ± 29.2 | 32.0 ± 16.5 | 0.363 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 0.646 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.8) | 0.698 |

| High-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.830 |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 2.4 (1.8, 2.9) | 2.4 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.4 (1.7, 2.9) | 0.374 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 0.465 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 4.0 (1.0, 7.1) | 4.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 4.0 (1.4, 7.0) | 0.751 |

Hs-CRP Hypersensitive C-reactive protein, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, PSD post-stroke depression

Association of advanced liver fibrosis with PSD

During the 3 months follow-up, 91 (27.9%) patients experienced PSD. Compared with non-PSD patients, the PSD group had a higher prevalence of education < 12 years (64.8% versus. 48.1%, P = 0.007), diabetes mellitus (44.0% versus. 18.3%, P < 0.001), and advanced liver fibrosis (35.2% versus. 20.4%, P = 0.006), and had a higher level of FIB-4 score (median, 2.3 versus. 1.8, P = 0.032), baseline NIHSS score (median, 5.0 versus. 5.0, P = 0.048), and Hs-CRP (median, 5.6 mg/L versus. 4.0 mg/L, P = 0.015) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline data between patients with and without 3-month PSD

| Variables | With PSD (n = 91) | Without PSD (n = 235) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics, | |||

| Age, year | 68.1 ± 10.8 | 66.0 ± 11.5 | 0.126 |

| Male, % | 42 (46.2) | 126 (53.6) | 0.226 |

| Education < 12 years, % | 59 (64.8) | 113 (48.1) | 0.007 |

| Risk factors, % | |||

| Hypertension | 69 (75.8) | 171 (72.8) | 0.547 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (44.0) | 43 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14 (15.4) | 55 (23.4) | 0.112 |

| Coronary heart disease | 16 (17.6) | 30 (12.8) | 0.262 |

| Current smoking | 34 (37.4) | 103 (43.8) | 0.289 |

| Clinical data | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 136.9 ± 24.9 | 136.0 ± 17.4 | 0.640 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 82.4 ± 9.5 | 82.0 ± 10.1 | 0.677 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.6 ± 2.7 | 24.2 ± 2.4 | 0.198 |

| Baseline NIHSS, score | 5.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 0.048 |

| Advanced liver fibrosis, % | 32 (35.2) | 48 (20.4) | 0.006 |

| FIB-4 index | 2.3 (1.3, 3.1) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | 0.032 |

| Stroke subtypes, % | 0.321 | ||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 42 (46.2) | 107 (45.5) | |

| Cardioembolism | 20 (22.0) | 43 (18.3) | |

| Small vessel occlusion | 20 (22.0) | 71 (30.2) | |

| Others | 9 (9.9) | 14 (6.0) | |

| Side of infarction, % | |||

| Left | 46 (50.5) | 119 (50.6) | 0.989 |

| Right | 53 (58.2) | 128 (54.5) | 0.539 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Platelet, 109/L | 177.5 ± 60.2 | 186.2 ± 57.4 | 0.225 |

| Aspartate transaminase, U/L | 31.8 ± 24.2 | 28.2 ± 16.9 | 0.135 |

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | 34.0 ± 21.3 | 32.0 ± 20.0 | 0.429 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 0.987 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 0.392 |

| High-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.228 |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 2.5 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) | 0.311 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 0.543 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 5.6 (2.0, 7.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 0.015 |

NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, PSD post-stroke depression

Table 3 illustrated the results of multivariate analysis for the association between the degree of liver fibrosis and PSD. After adjusting for potential confounders (including age, sex, education years, diabetes mellitus, baseline NIHSS score, and Hs-CRP levels), multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated that advanced liver fibrosis was independently associated with a higher risk of PSD (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.03–3.42, P = 0.040). The observed association remained significant when the FIB-4 index was analyzed as a continuous variable (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.02–1.66, P = 0.037). The multivariable spline regression model further confirmed a linear association between the FIB-4 score and PSD risk (P for linearity = 0.068, Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis according to the degree of liver fibrosis for PSD

| Variables | Crude model | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Parameters as continuous variables | ||||||

| FIB-4 index | 1.32 (1.07–1.62) | 0.009 | 1.30 (1.03–1.63) | 0.027 | 1.30 (1.02–1.66) | 0.037 |

| Parameters as categorical variables | ||||||

| With advanced liver fibrosis | 2.11 (1.24–3.61) | 0.006 | 2.03 (1.15–3.55) | 0.014 | 1.88 (1.03–3.42) | 0.040 |

Model 1 adjusted for age and sex

Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, education years, diabetes, baseline NIHSS score and Hypersensitive C-reactive protein levels

CL Confidence interval, OR Odd ratio, PSD Post-stroke depression

Fig. 1.

Association of fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index with odds ratios of post-stroke depression (PSD) at 3 months. The restricted cubic spline of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with 4 knots located at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution of the FIB-4 score. The midpoints of FIB-4 score reference groups from categorical analyses serve as the reference point. Odds ratios were controlled for the same covariates included in model 2 in Table 3

Adding the FIB-4 score to a model containing conventional risk factors significantly improved risk reclassification for PSD (continuous net reclassification improvement, 0.326; 95% CI, 0.087 − 0.565, P = 0.008; integrated discrimination improvement, 0.053; 95% CI, 0.027 − 0.080, P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reclassification Statistics (95% CI) for PSD by liver fibrosis

| Models | cNRI | IDI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| + FIB-4 index | 0.293 (0.053 − 0.532) | 0.017 | 0.017 (0.001 − 0.034) | 0.039 |

| + Advanced liver fibrosis | 0.262 (0.035 − 0.489) | 0.024 | 0.021 (0.004 − 0.036) | 0.016 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| + FIB-4 index | 0.326 (0.087 − 0.565) | 0.008 | 0.053 (0.027 − 0.080) | < 0.001 |

| + Advanced liver fibrosis | 0.526 (0.293 − 0.759) | < 0.001 | 0.056 (0.029 − 0.082) | < 0.001 |

Model 1 adjusted for age and sex

Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, education years, diabetes, baseline NIHSS score and Hypersensitive C-reactive protein levels

CI confidence interval, cNRI continuous net reclassification improvement, IDI integrated discrimination improvement, PSD Post-stroke depression

Discussion

In recent decades, the extensive focus on PSD is fully justified because of its negative impact on quality of life, cognitive and functional performance, and mortality after stroke [1–3, 25]. We found that advanced liver fibrosis was associated with increased odds for depression at 90 days post-stroke, after adjustment for potential confounders including demographic characteristics and baseline stroke deficits. Furthermore, adding the severity of liver fibrosis into PSD risk stratification may improve case identification.

In our cohort, we observed that 27.9% of ischemic stroke patients were diagnosed with depression 3 months later, which was similar to a recent systematic review indicating that the frequency of PSD is 33.0% (95% CI, 29% to 36%) [26]. Cumulative evidence has shown that PSD is associated with several well-known risk factors such as demographic characteristics, medical history, and stroke characteristics [21, 27, 28]. PSD is highly prevalent among both men and women. However, Chen et al. found that PSD is more common in women than men [28]. As for stroke location, Robinson et al. suggested that patients with left hemisphere lesions are more likely to have PSD than those without it, which is supported by other scholars [29]. But Sun et al. indicated that there was a significant correlation between depressive symptoms and right hemisphere lesions 6 months after stroke [27]. Also, our study did not confirm the association of PSD with females and stroke location. The discrepancy in risk factors of PSD might be due to the different time points in performing the psychological measurement. These results further emphasize the need for an internationally agreed definition of PSD.

To date, several cross-sectional studies have evaluated liver function in predicting clinical outcomes in stroke patients [11, 30–32]. A single-center study enrolling Korean found that the risk of long-term mortality was increased in ischemic stroke patients with significant liver fibrosis evaluated by transient elastography [30]. Similar results were found when liver fibrosis was evaluated by FIB-score [11]. In addition, liver fibrosis was reported to be associated with the risk of hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients without the clinically overt liver disease [31]. Another recent study recruited patients with largely normal liver chemistries and found that the FIB-4 score and the aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index were associated with admission hematoma volume, hematoma expansion, and mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage [32]. Apart from the functional outcome, our study further confirmed the hypothesis that the development of depressive symptoms may mediate by the degree of liver fibrosis.

Although the exact mechanism by which liver fibrosis affects PSD after acute stroke is not fully elucidated, several explanations may account for the observed association. Firstly, the inflammatory response is commonly present in all stages of liver disease and related to the presence and development of fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [33]. At present, inflammation has attracted considerable attention as an important mechanism of PSD. The activation of several pro-inflammatory cytokines might induce alternations in brain function including the alteration of neurotransmission and increasing activity of the HPA axis [34], which may contribute to an increased risk of PSD. Secondly, Jagavelu et al. found that liver fibrosis could cause endothelial dysfunction [35]. Meanwhile, endothelial dysfunction has been shown to regulate depressive symptoms in a general elderly population [36]. Furthermore, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has been associated with several subclinical atherosclerosis markers including carotid intimal medial thickness carotid plaques [37]. According to the population-based PREVENCION study among South American Hispanics, depressive symptoms were associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in men [38]. These data demonstrated that liver fibrosis plays an important role in the pathobiology of PSD by mediating subclinical atherosclerosis.

Our study had several limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, this study is a single-center design with a relatively homogeneous ischemic stroke sample, which may have inherent selection bias and limit the generalization to other populations. Secondly, the degree of liver fibrosis was tested only at baseline after stroke without serial measurements, we were unable to exclude the impact of stroke on liver fibrosis. Thirdly, our study excluded the ischemic stroke patients with aphasia, dysarthria, and severe neurological deficits that precluded us from performing the psychological evaluations, which could have resulted in an underestimation of actual PSD rates. Finally, due to the observational nature of this study, it cannot demonstrate a causal relationship. These issues should be resolved in further longitudinal cohort studies with large samples.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this investigation suggested that the advanced liver fibrosis assessed by the FIB-4 score was significantly correlated to the development of PSD 3 months after stroke. Ischemic stroke patients should be monitored for liver fibrosis and followed-up with appropriate interventions. Also, these findings should be further ascertained by animal experiments and cohort studies using more representative hospital-based samples.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

YZ and YT designed the study. YZ, YY, YF, and ZC recorded the clinical data. YZ and LH carried out data analysis. YZ wrote the manuscript. Important data analysis suggestions were made by SX, JS and BY. Manuscript revisions: YT. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript

Funding

No.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Mianyang Central Hospital. All procedures performed in studies were under the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants or their relatives.

Consent for publication

NA.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yun Zhang, Email: zhangyun_neuro@126.com.

Yufeng Tang, Email: dryufeng@126.com.

References

- 1.Guo J, Wang J, Sun W, Liu X. The advances of post-stroke depression: 2021 update. J Neurol. 2022;269:1236–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson R, Jorge R. Post-Stroke Depression: A Review. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:221–231. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villa R, Ferrari F, Moretti A. Post-stroke depression: Mechanisms and pharmacological treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;184:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindén T, Blomstrand C, Skoog I. Depressive disorders after 20 months in elderly stroke patients: a case-control study. Stroke. 2007;38:1860–1863. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.471805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Crichton S, Rudd A, Wolfe C. Explanatory factors for the increased mortality of stroke patients with depression. Neurol. 2014;83:2007–2012. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Q, Zhou A, Han Y, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang X, et al. Poststroke depression and risk of recurrent stroke: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Med (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17235. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344–e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younossi Z, Koenig A, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatol. 2016;64:1. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu M, Zha M, Lv Q, Xie Y, Yuan K, Zhang X, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and stroke: A Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:1534–1537. doi: 10.1111/ene.15277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekstedt M, Hagström H, Nasr P, Fredrikson M, Stål P, Kechagias S, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatol. 2015;61:1547–1554. doi: 10.1002/hep.27368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baik M, Nam H, Heo J, Park H, Kim B, Park J, et al. Advanced Liver Fibrosis Predicts Unfavorable Long-Term Prognosis in First-Ever Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;49:474–480. doi: 10.1159/000510436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterling R, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa M, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatol. 2006;43:1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Kim D, Kim H, Lee C, Yang J, Kim W, et al. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forns X, Ampurdanès S, Llovet J, Aponte J, Quintó L, Martínez-Bauer E, et al. Identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model. Hepatol. 2002;36:986–992. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine J, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatol. 2018;67:328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroke-1989 Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the WHO Task Force on Stroke and other Cerebrovascular Disorders. Stroke. 1989;20:1407–31. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson A, Klein J, White B, Bourgeois M, Leonard A, Pacino A, et al. Training and Certifying Users of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Stroke. 2020;51:990–993. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams HJ, Bendixen B, Kappelle L, Biller J, Love B, Gordon D. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fandler-Höfler S, Stauber R, Kneihsl M, Wünsch G, Haidegger M, Poltrum B, et al. Non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis and outcome in large vessel occlusion stroke. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211037239. doi: 10.1177/17562864211037239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Tang Y, Xie Y, Ding C, Xiao J, Jiang X, et al. Total magnetic resonance imaging burden of cerebral small-vessel disease is associated with post-stroke depression in patients with acute lacunar stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:374–380. doi: 10.1111/ene.13213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li G, Miao J, Pan C, Jing P, Chen G, Mei J, et al. Higher Serum Lactic Dehydrogenase is Associated with Post-Stroke Depression at Discharge. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:2047–2055. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S341169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu J, Wang L, Fan K, Ren W, Wang Q, Ruan Y, et al. The Association Between Systemic Inflammatory Markers and Post-Stroke Depression: A Prospective Stroke Cohort. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1231–1239. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S314131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8:551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medeiros G, Roy D, Kontos N, Beach S. Post-stroke depression: A 2020 updated review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackett M, Pickles K. Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:1017–1025. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun N, Li Q, Lv D, Man J, Liu X, Sun ML. A survey on 465 patients with post-stroke depression in China. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:368–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Luan X, Zhao K, Qiu H, Liu Y, Tu X, et al. The association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and post-stroke depression. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;486:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson R, Lipsey J, Rao K, Price T. Two-year longitudinal study of post-stroke mood disorders: comparison of acute-onset with delayed-onset depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1238–1244. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baik M, Kim S, Kang S, Park H, Nam H, Heo J, et al. Liver Fibrosis, Not Steatosis, Associates with Long-Term Outcomes in Ischaemic Stroke Patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;47:32–39. doi: 10.1159/000497069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan C, Ruan YT, Zeng Y, Cheng H, Cheng Q, Chen Y, et al. Liver Fibrosis Is Associated With Hemorrhagic Transformation in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Front Neurol. 2020;11:867. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parikh N, Kamel H, Navi B, Iadecola C, Merkler A, Jesudian A, et al. Liver Fibrosis Indices and Outcomes After Primary Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;51:830–837. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seki E, Schwabe RF. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: functional links and key pathways. Hepatology. 2015;61:1066–1079. doi: 10.1002/hep.27332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spalletta G, Bossù P, Ciaramella A, Bria P, Caltagirone C, Robinson R. The etiology of poststroke depression: a review of the literature and a new hypothesis involving inflammatory cytokines. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:984–991. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jagavelu K, Routray C, Shergill U, O'Hara S, Faubion W, Shah V. Endothelial cell toll-like receptor 4 regulates fibrosis-associated angiogenesis in the liver. Hepatology. 2010;52:2. doi: 10.1002/hep.23739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Sloten TT, Schram MT, Adriaanse MC, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Teerlink T, et al. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with a greater depressive symptom score in a general elderly population: the Hoorn Study. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1403–1416. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madan S, John F, Pyrsopoulos N, Pitchumoni C. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and carotid artery atherosclerosis in children and adults: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:1237–1248. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chirinos D, Medina-Lezama J, Salinas-Najarro B, Arguelles W, Llabre M, Schneiderman N, et al. Depressive symptoms and carotid intima-media thickness in South American Hispanics: results from the PREVENCION study. J Behav Med. 2015;38:284–293. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9599-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.