ABSTRACT

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is one of the most important pathogens in the global pig industry, which modulates the host’s innate antiviral immunity to achieve immune evasion. RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) sense viral RNA and activate the interferon signaling pathway. LGP2, a member of the RLR family, plays an important role in regulating innate immunity. However, the role of LGP2 in virus infection is controversial. Whether LGP2 has a role during infection with PRRSV remains unclear. Here, we found that LGP2 overexpression restrained the replication of PRRSV, while LGP2 silencing facilitated PRRSV replication. LGP2 was prone to interact with MDA5 and enhanced viral RNA enrichment and recognition by MDA5, thus promoting the activation of RIG-I/IRF3 and NF-κB signaling pathways and reinforcing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and type I interferon during PRRSV infection. Meanwhile, there was a decreased protein expression of LGP2 upon PRRSV infection in vitro. PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interacted with LGP2 and promoted K63-linked ubiquitination of LGP2, ultimately leading to the degradation of LGP2. These novel findings indicate that LGP2 plays a role in regulating PRRSV replication through synergistic interaction with MDA5. Moreover, targeting LGP2 is responsible for PRRSV immune evasion. Our work describes a novel mechanism of virus-host interaction and provides the basis for preventing and controlling PRRSV.

IMPORTANCE LGP2, a member of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), shows higher-affinity binding to RNA and work synergism with RIG-I or MDA5. However, LGP2 has divergent responses to different viruses, which remains controversial in antiviral immune responses. Here, we present the detailed process of LGP2 in positively regulating the anti-PRRSV response. Upon PRRSV infection, LGP2 was prone to bind to MDA5 and enhanced MDA5 signaling, manifesting the enrichment of viral RNA on MDA5 and the activation of downstream IRF3 and NF-κB, which results in increased proinflammatory cytokines and type I interferon expression, ultimately inhibiting PRRSV at the early stage of infection. Moreover, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interacted with LGP2 via ubiquitin-proteasome pathways, thus blocking LGP2-mediated immune response. This research helps us understand the host recognition and innate antiviral response to PRRSV infection by neglected pattern recognition receptors, which sheds light on the detailed mechanism of virus-host interaction.

KEYWORDS: PRRSV, LGP2, MDA5, Nsp1, Nsp2, innate immune response

INTRODUCTION

PRRSV is an enveloped single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus. The genome size of PRRSV is ~15 kb with 10 open reading frames (ORFs) (1). ORF1a and ORF1ab encode nonstructural proteins (NSPs) involved in viral replication, while ORFs 2 to 7 encode viral structural proteins (2). It is known that nonstructural proteins of PRRSV (Nsp1α, Nsp1β, Nsp2, Nsp4, and Nsp11) have been identified to antagonize interferon signaling (3). PRRSV Nsp1α disrupted the interaction between interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and CREB binding protein (CBP), leading to the degradation of CBP and the decrease of type I interferon (IFN) production (4). Nsp1β, Nsp2, and nucleocapsid (N) proteins blocked IRF3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, thus reducing type I interferon expression (5–7). Nsp11 degraded the mRNA of mitochondrial antiviral signaling proteins (MAVS) and inhibited IRF3 activation (8). Nsp1β and N proteins could block STAT1/STAT2 nuclear translocation, thereby inhibiting the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (9). Simultaneously, PRRSV Nsp1, Nsp1α, Nsp4, and Nsp11 inhibited the activation of NF-κB, resulting in decreased type I interferon expression (10). Our previous study demonstrated that PRRSV Nsp4 could reduce PKR protein expression, thus interfering with the PKR-mediated unfolded protein response and interferon production (11). PRRSV can trigger host innate immune signaling pathways, while viral proteins can inhibit antiviral response by interacting with the host antiviral protein. A complete understanding of the interaction between PRRSV and the host’s innate immunity will elucidate PRRSV pathogenesis and help us to develop a better strategy to control PRRS.

The innate immune system is the first line to protect the body against attacking pathogens. The battle against viral invasion begins with recognition. The retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptor (RLR) is one of the families involved in the cytoplasmic recognition of virus-specific components. RLRs sense specific viral nucleic acid and activate downstream cascade inflammatory and antiviral responses, leading to type I IFN and inflammatory cytokine production (12). The RLR family consists of three homologous helicases, including RIG-I (Retinoic acid-Inducible Gene I), MDA5 (Melanoma Differentiation-Associated factor 5), and LGP2 (Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology 2) (13, 14). They are responsible for viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) recognition and ATP hydrolyzation, while the ability for signaling activation differs (15). Two RLRs, RIG-I and MDA5, have been extensively studied and exerted their activity by interacting with downstream adaptor MAVS via their caspase activation recruitment domains (CARDs). Subsequently, the activation of NF-κB and IRF3 are triggered, leading to the transcriptional activation of various antiviral-related genes (16, 17). Compared to RIG-I and MDA5, LGP2 has helicase and regulatory domains but lacks the N-terminal CARDs, which are essential for antiviral signal transduction (18). Hence, LGP2 cannot trigger the downstream signaling pathway alone and needs to bind to RIG-I or MDA5 for signaling transduction. Due to the lack of CARD region in LGP2, the exact role of LGP2 in antiviral immunity has remained controversial: it is expected to either positively or negatively affect the RIG-I- or MDA5-mediated IFN response and production.

In support of the proposed inhibitory role of LGP2 in RIG-I signaling, studies have shown that overexpression of LGP2 inhibits STAT1 activation and IFN transcription in cells infected with seasonal influenza A viruses (19). In addition, LGP2 can promote the infection of Sendai paramyxovirus and Newcastle disease virus by inhibiting the RIG-I signaling pathway and the expression of type I IFN (20, 21), indicating LGP2 possibly plays a negative regulatory role in innate immunity. In contrast to the reports of negative regulation by LGP2, recent studies have shown that LGP2 could contribute to viral RNA recognition for MDA5 and play a synergistic role in enhancing antiviral signal transduction and type I interferon production (22). It was reported that SARS-CoV-2 specifically activated MDA5 and LGP2-mediated IFN responses (23). LGP2 facilitated MDA5-mediated antiviral immune response to inhibit duck enteritis virus (DEV) infection (24). LGP2 knockout mice were more susceptible to encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) infection and, simultaneously, NF-κB signaling and IFN regulatory factors were significantly inhibited (25). In LGP2-deficient cells, cytokine production was significantly reduced, leading to the impairment of IFN responses to modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) infection (26). LGP2 positively regulated the IFN response induced by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), and type I IFN production was significantly reduced in LGP2-knockout hepatocytes (27). Moreover, overexpression of LGP2 inhibited foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) replication and significantly restrained inflammatory response in virus-infected cells (28). Accordingly, LGP2 is an important innate immune molecule that regulates viral replication via RIG-I and IFN signaling pathways. However, little is known about the relationship and possible regulatory manners between LGP2 and PRRSV.

Many viruses can evade LGP2-mediated innate immune responses by interacting with LGP2. Paramyxovirus V proteins were reported to bind directly to the LGP2 helicase domain, thus disrupting its ATP hydrolytic activity and inhibiting IFN production (29). Measles virus and parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5) V proteins interacted with LGP2 and prevented the coactivation of MDA5 signaling (30). Although LGP2 positively regulates HCV-induced IFN immune response, HCV NS3 protein interaction with the LGP2 helicase domain inhibits IFN production (27). Similarly, FMDV Leader protease (Lpro) targeted LGP2 for cleavage, thus inhibiting LGP2-mediated antiviral immune response (28, 31). As indicated above, modulation of host innate immune responses plays a key role in PRRSV immune evasion. Whether the interaction between PRRSV protein and LGP2 shows suppression of antiviral response remains unclear.

In this study, we found that LGP2 overexpression restrained the replication of PRRSV, whereas LGP2 silence promoted PRRSV replication. LGP2 was inclined to interact with MDA5 and increased viral RNA binding to MDA5 during PRRSV infection, which promoted the activation of IRF3 and NF-κB, thus enhancing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs. Conversely, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 could degrade the protein level of LGP2 via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Collectively, LGP2 functions as a positive regulator of anti-PRRSV responses. These results shed new light on the mechanisms of virus-host interaction.

RESULTS

LGP2 suppresses PRRSV infection.

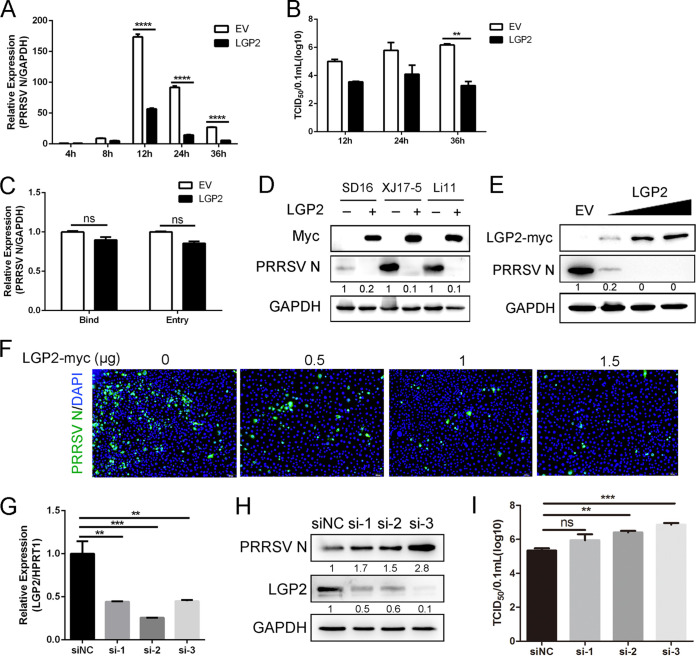

LGP2 is a member of the RLRs family, responsible for viral RNA recognition and host innate immune activation. To investigate the role of LGP2 in PRRSV infection, Marc-145 cells were transfected with LGP2 plasmids and then infected with PRRSV (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 1) for the indicated time. As shown in Fig. 1A, LGP2 overexpression significantly decreased the mRNA level of viral ORF7 at 8, 12, 24, and 36 h postinfection (hpi). Meanwhile, compared to controls, cells with LGP2 overexpressed had lower virus titers, especially at 36 hpi (Fig. 1B). Since there was no significant difference in viral ORF7 mRNA at 4 hpi, whether LGP2 affected viral binding and entry was investigated. Marc-145 cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) and LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, respectively, followed by viral binding and entry assays. As shown in Fig. 1C, there was no significant difference in viral binding and entry under the condition of LGP2 overexpression. These data indicated that LGP2 had little effect on viral binding and entry but interrupted the period of PRRSV replication. Next, we examined the effects of LGP2 on the PRRSV at the protein levels. Marc-145 cells were transfected with LGP2 and EV and infected with the SD16 strain, the XJ17-5 strain, and the Li11 strain, as shown in Fig. 1D. LGP2 overexpression showed inhibitory effects on different strains of PRRSV.

FIG 1.

LGP2 has effects on PRRSV replication. (A) Marc-145 cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36 hpi, cells were collected. The transcription levels of PRRSV N were shown using qRT-PCR. (B) Cell supernatants of different periods postinfection (12, 24, and 36 hpi) were collected for determining the TCID50. (C) Marc-145 cells were transfected with an empty vector and Myc-tagged LGP2 for 24 h, and then virus binding and entry assays were carried out. For the viral binding assay, cells were precooled at 4°C for 2 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) at 4°C for another 2 h, under the condition that virions bind to the cell surface but cannot enter. For the viral entry assay, cells were washed with cold PBS immediately after the viral attachment assay and incubated at 37°C for another 2 h, and an alkaline high-salt solution was used to remove cell-surface-associated viruses. Cells were collected to detect viral load using qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (D) Marc-145 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing LGP2 or empty vector for 24 h, and cells were infected with SD16 strain, XJ17-5 strain, and Li11 strain (MOI = 1) for another 24 h. Western blotting was used to detect the expression of Myc and PRRSV N. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (E and F) Control plasmid and different concentrations of Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmids (0, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 μg) were transfected into Marc-145 cells for 24 h, and then cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1). The expression of Myc, PRRSV N, and GAPDH is shown, as measured by Western blotting. GAPDH was included as an internal control (E). Immunofluorescence analysis of PRRSV N (green) expression in Marc-145 cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 200 μm (F). (G to I) LGP2 knockdown facilitated PRRSV infection. (G) PAMs were transfected with negative-control siRNA (siNC) or three LGP2 siRNA (si-1, si-2, and si-3) for 24 h, respectively. LGP2 mRNA expression was detected using qRT-PCR analysis. (H) After LGP2 interference, PAMs were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h, and protein levels of PRRSV N and LGP2 were determined using Western blotting. (I) The TCID50 is shown from cell supernatants. For Western blotting, the relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control. The data are the results of three independent experiments (means ± the standard errors [SE]). Significant differences are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Furthermore, different doses of LGP2 plasmids were transfected into Marc-145 cells, and then cells were infected with the CHR6 strain. We observed that LGP2 overexpression markedly suppressed PRRSV replication, as shown by decreased PRRSV N protein. Meanwhile, PRRSV N expression was decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1E). Immunofluorescence analysis also demonstrated significant inhibition of viral replication in LGP2-overexpressing cells (Fig. 1F). Three siRNAs were designed to identify whether silencing of LGP2 plays a different role on PRRSV infection. As shown in Fig. 1G, the LGP2 mRNA level was significantly decreased when porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) were transfected with these siRNAs. As expected, we found that LGP2 knockdown increased the levels of viral N protein, indicating PRRSV replication was promoted when LGP2 was silenced (Fig. 1H). Similarly, silencing of LGP2 significantly enhanced virus titers in PAMs compared to controls (Fig. 1I). These data suggest LGP2 is involved in PRRSV infection and plays a role in regulating PRRSV replication.

LGP2 promotes type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines production following PRRSV infection.

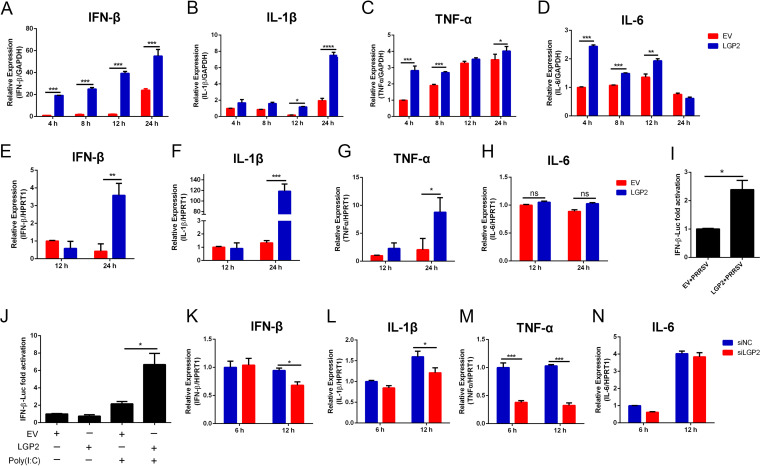

The role of LGP2 in virus-triggered innate immunity has remained controversial. It positively or negatively influences the RIG-I signaling and IFN production in virus-infected cells (22). Based on the inhibitory effects of LGP2 upon PRRSV replication, we determined whether LGP2 regulates the production of inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons during PRRSV infection. Marc-145 cells were mock transfected or transfected with LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, and cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. Compared to EV-transfected cells, cells with LGP2 overexpression significantly enhanced the expression of IFN-β as early as 4 hpi and retained high expression from 4 to 24 hpi (Fig. 2A). The expression of IL-1β was also significantly increased at 12 and 24 hpi in LGP2-overexpressed cells (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) mRNA expressions were induced as early as 4 hpi in LGP2-overexpressed cells, though transcript levels were attenuated at subsequent time points (Fig. 2C and D). In addition, we used 3D4/21 cells, an immortal macrophage cell line with CD163 stable expression, to further demonstrate the effects of LGP2 on type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines following PRRSV infection. Similarly, LGP2 overexpression boosted IFN-β, IL-1β, and TNF-α transcription at 24 hpi in 3D4/21 cells (Fig. 2E to G). However, there was no difference in IL-6 mRNA expression when 3D4/21 cells were transfected with the LGP2 plasmid (Fig. 2H). Dual-luciferase reporter assay was used to measure IFN-β promoter activation. As shown in Fig. 2I, LGP2 overexpression remarkably activated the promoter activity of IFN-β in PRRSV-infected cells compared to those in control cells. Similarly, the activation of IFN-β exhibited stronger when cells were transfected with LGP2 in the presence of poly(I·C) (Fig. 2J). Moreover, we chose one LGP2 siRNA (si-3) pair for LGP2 interference. PAMs were transfected with this siRNA and then infected with PRRSV. We detected the transcription of these cytokines at 6 and 12 hpi. Except for IL-6, other cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-β) were significantly decreased in PAMs with LGP2 silencing (Fig. 2K to N). Taken together, LGP2 promotes IFN-β and proinflammatory cytokines expression, which correlates with the inhibition of PRRSV replication.

FIG 2.

LGP2 facilitates the expression of IFN-β and proinflammatory cytokines during PRRSV infection. (A to D) Marc-145 cells were transfected with control plasmid and LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, and cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. The relative expressions of IFN-β (A), IL-1β (B), TNF-α (C), and IL-6 (D) were detected using qRT-PCR, and GAPDH served as an internal control. (E to H) 3D4/21 cells were transfected with control plasmid and LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, and cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 12 and 24 h. The relative expression of IFN-β (E), IL-1β (F), TNF-α (G), and IL-6 (H) was detected using qRT-PCR. The data are normalized to GAPDH in each sample. (I) Marc-145 cells were transfected with the control plasmid and Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, and cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1). The activation of the IFN-β promoter was shown using dual-luciferase reporter assays. (J) HEK293T cells were mock stimulated or stimulated with poly(I·C) for 8 h in the absence or presence of LGP2 overexpression. The activation of the IFN-β promoter was shown using dual-luciferase reporter assays. (K to N) PAMs were transfected with negative-control siRNA or LGP2 siRNA (si-3) for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 6 and 12 h. The relative expression of IFN-β (K), IL-1β (L), TNF-α (M), and IL-6 (N) was detected using qRT-PCR. The data are normalized to GAPDH in each sample. The data are the results of three independent experiments (means ± the SE). Significant differences are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

LGP2 potentially interacts with MDA5 and leads to activation of RIG-I and NF-κB signaling during PRRSV infection.

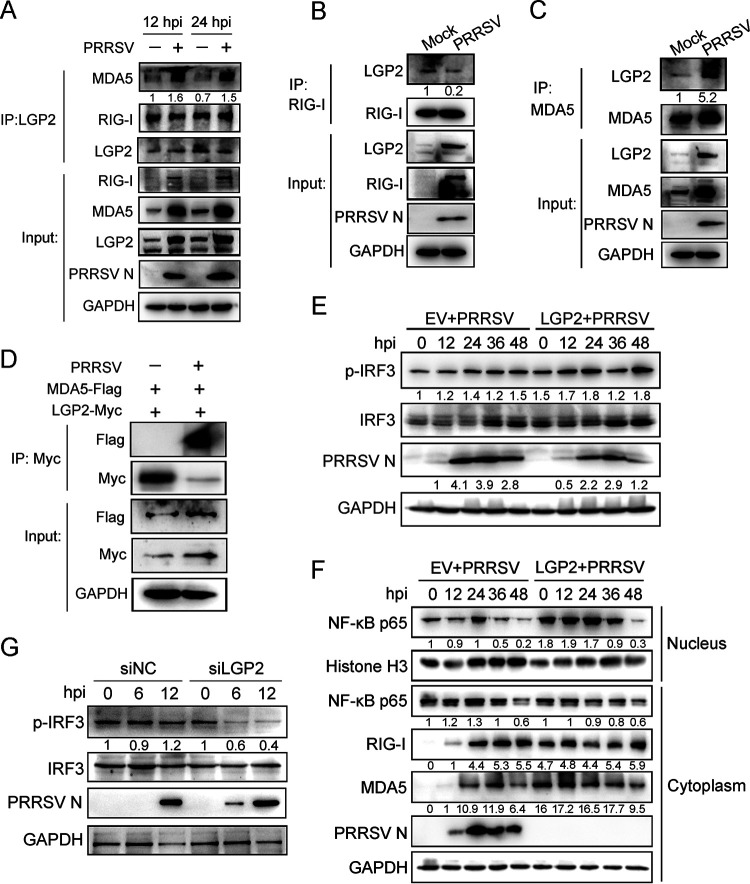

It has been reported that LGP2 potentiates viral RNA-induced signaling by working upstream of RIG-I, MDA5, and MAVS (18). How does LGP2 function on IFN-I signaling during PRRSV infection? According to the positive role LGP2 played in anti-PRRSV, we speculated that LGP2 was essential for the augmentation of RIG-I signaling. To address this hypothesis, PAMs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 12 and 24 h. As shown in Fig. 3A, the interaction between LGP2 and MDA5 was enhanced in PRRSV-infected cells, while the LGP2 antibody immunoprecipitated the constant amount of RIG-I in the absence or presence of PRRSV infection. Moreover, we used a RIG-I antibody and an MDA5 antibody to precipitate LGP2, and the results showed no obvious difference in LGP2 that RIG-I immunoprecipitated when cells were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (Fig. 3B). However, MDA5 precipitated more LGP2 protein upon PRRSV-infected cells (Fig. 3C). In addition, Marc-145 cells were cotransfected with LGP2 and MDA5 plasmids and then infected or mock infected with PRRSV for 12 h. Immunoprecipitation assays indicated that LGP2 interacted with MDA5 when cells were infected with PRRSV, and this interaction was enhanced in virus-infected cells (Fig. 3D). These results suggested that LGP2 was inclined to interact with MDA5 in PRRSV-infected cells. To further identify LGP2 accelerated the activation of RIG-I signaling following PRRSV infection. Marc-145 cells were transfected with LGP2 plasmid or empty vector for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1). It was shown that LGP2 overexpression catalyzed the phosphorylation of IRF3 and enhanced the phosphorylated IRF3 level. Besides, the total IRF3 also maintained a greater magnitude in LGP2-transfected cells than in EV-transfected cells (Fig. 3E). Simultaneously, a cell fractionation assay was performed to detect the nuclear translocation of p65, representing the activation of NF-κB signaling. As shown in Fig. 3F, the nuclear translocation of p65 occurred as early as 0 hpi and increasingly accumulated in the cells with LGP2 overexpressing, which occurred much earlier than the negative control. In addition, LGP2 overexpression increased the protein expression of endogenous RIG-I and MDA5 at 0 and 12 hpi, the early stage of PRRSV infection, compared to the control. In addition, PAMs were transfected with LGP2 or negative siRNA for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1). As shown in Fig. 3G, LGP2 knockdown reduced IRF3 phosphorylation in PAMs at 6 and 12 hpi compared to the negative control. LGP2 is more prone to interact with MDA5 and facilitates the activation of RIG-I signaling and NF-κB signaling following PRRSV infection.

FIG 3.

LGP2 interacts with MDA5 and activates RIG-I signaling and NF-κB signaling. (A) PAMs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 12 and 24 h, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an LGP2 antibody. Immunoblots of MDA5, RIG-I, and LGP2 are shown. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (B) PAMs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the RIG-I antibody, and immunoblots were shown to detect the interaction between LGP2 and RIG-I. (C) PAMs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with MDA5 antibody, and immunoblots showed the interaction change between LGP2 and MDA5. (D) Marc-145 cells were cotransfected with Myc-tagged LGP2 and Flag-tagged MDA5 plasmids for 24 h, and cells were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody, precipitated with Flag-tagged MDA5, and Myc-tagged LGP2 were detected using immunoblotting. (E) Marc-145 cells were transfected with empty vector and LGP2 plasmids for 24 h and incubated with PRRSV at 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hpi, cells were collected. The protein levels of p-IRF3, IRF3, and PRRSV N were determined using Western blot analysis. (F) Marc-145 cells were treated as described in panel E. Cells were collected, and nuclear and cytoplasmic protein samples were extracted using a nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit. Western blotting was performed to detect the expression of NF-κB p65, RIG-I, MDA5, and PRRSV N. Histone H3 is used as an internal nuclear control, and GAPDH serves as the cytoplasmic internal control. (G) PAMs were transfected with scrambled siRNA or LGP2 siRNA (si-3) for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 0, 6, and 12 h. The protein expression of PRRSV N, p-IRF3, and IRF3 are shown, as detected by Western blotting. For the Western blot, the relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control.

LGP2 promotes viral RNA recruitment and recognition by MDA5.

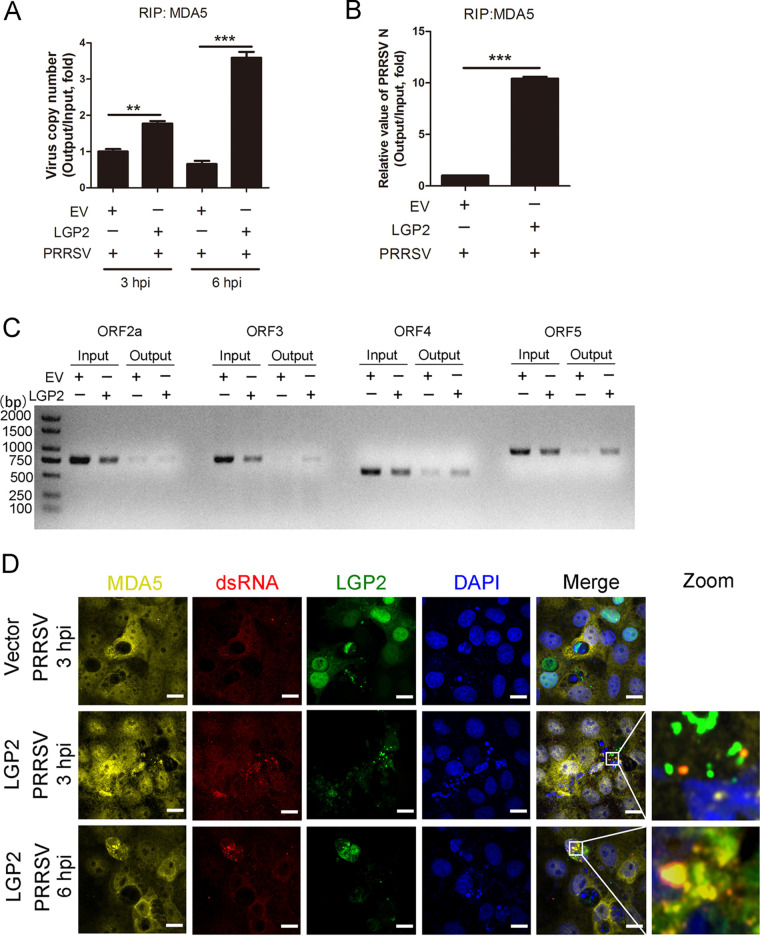

It is reported that LGP2 has higher-affinity binding to dsRNA and ssRNA, whether LGP2 increases the initial rate of MDA5-RNA interaction when LGP2 interacts with MDA5 following PRRSV infection, Marc-145 cells were mock transfected or transfected with LGP2 plasmids for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for 3 or 6 h. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays were carried out to analyze the amount of viral RNA binding to MDA5, and the copy number of the virus was detected. As shown in Fig. 4A, MDA5 constitutively interacted with viral RNA at 3 and 6 hpi, and this interaction was significantly enhanced in cells with LGP2 overexpression. Likewise, the PRRSV N mRNA immunoprecipitated by MDA5 in LGP2-overexpressing cells was greater than in control cells (Fig. 4B). After RIP assays, MDA5-interacted RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and it was amplified with corresponding primers of different PRRSV ORFs. As shown in Fig. 4C, the bands of ORF2a, ORF3, ORF4, and ORF5 were detected, and the bands were increased in LGP2-overexpressed cells, suggesting that MDA5 could indeed bind to PRRSV RNA, and MDA5 interacted more PRRSV RNA upon LGP2 overexpression. To further investigate dsRNA recruitment of MDA5 and LGP2, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged LGP2 plasmids were mock transfected or transfected into Marc-145 cells and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for 3 or 6 h. Immunofluorescence assays revealed the colocalization of LGP2, MDA5, and viral dsRNA, indicating that LGP2 interacted with MDA5 and carried viral dsRNA to MDA5 (Fig. 4D). These data demonstrated that LGP2 promotes the recruitment and recognition of viral dsRNA to MDA5, thus amplifying the downstream cascade of antiviral immune responses.

FIG 4.

LGP2 facilitated viral RNA binding to MDA5. (A) Marc-145 cells were mock transfected and transfected with LGP2 plasmids for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for another 3 or 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an MDA5 antibody, and immunoprecipitated RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed. The PRRSV copy number was detected using TaqMan real-time qPCR. The columns represent the relative value of precipitated viral RNA (Output)/total viral RNA (Input). (B) Marc-145 cells were mock transfected and transfected with LGP2 plasmids for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for another 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an MDA5 antibody, and the relative value of PRRSV N (ORF7) was detected using SYBR green qPCR. (C) The agarose gel electrophoresis of PRRSV ORF2a, ORF3, ORF4, and ORF5 PCR products after RIP assays and amplified with the corresponding primers. (D) Marc-145 cells were mock transfected and transfected with GFP-tagged LGP2 plasmids for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for another 3 or 6 h. Immunofluorescence analysis of the colocalization among MDA5 (yellow), LGP2 (green), dsRNA (red), and DAPI (blue) is performed. Scale bar, 10 μm. The data are the results of three independent experiments (means ± the SE). Significant differences are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

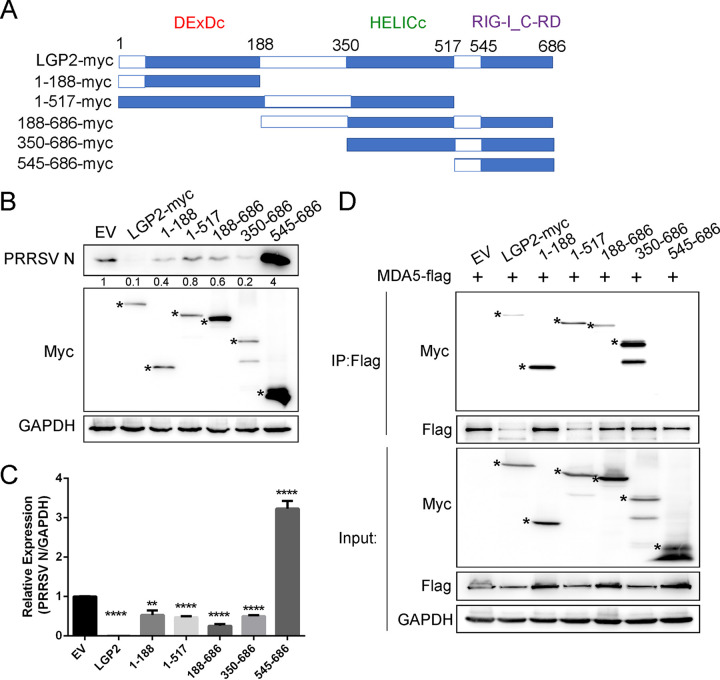

DExDc and HELICc domains of LGP2 are required for the regulation of PRRSV.

LGP2 consists of a DEAD-like helicase superfamily ATP binding domain (DExDc), a helicase superfamily C-term domain associated with DExH/D box proteins (HELICc), and a C-terminal regulatory domain of RIG-I (RIG-I_C-RD), lacking the N-terminal CARDs (18, 32). To map the domain(s) of LGP2 associated with PRRSV replication, Myc-tagged truncated LGP2 plasmids were constructed and transfected into Marc-145 cells, and then cells were infected with PRRSV (Fig. 5A). We found that full-length LGP2 significantly restrained the protein expression of PRRSV N, and LGP2 fragments containing either DExDc or HELICc domains still inhibited N protein expression, even though there was a weak recovery. However, LGP2 fragments lacking both domains had been shown to increase the expression of viral N protein (Fig. 5B). Consistently, quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis also demonstrated that LGP2 fragments with DExDc or HELICc domains could downregulate the transcript levels of PRRSV N, but the inhibition of viral replication was eliminated in the absence of DExDc and HELICc domains (Fig. 5C). We have demonstrated LGP2 interacts with MDA5 and leads to the activation of downstream signaling. To map the domain(s) of LGP2 required for the LGP2/MDA5 interaction, we cotransfected Flag-tagged MDA5 and Myc-tagged full-length or truncated LGP2 into HEK293T cells. We found that LGP2 constructs comprising the DExDc or HELICc region coprecipitated with MDA5, while LGP2 only with RIG-I_C-RD fragments had no interaction with MDA5, which was consistent with that affecting virus replication, indicating DExDc and HELICc domains of LGP2 interacted with MDA5 and facilitated antiviral response, results in suppression of PRRSV (Fig. 5D). LGP2 DExDc and HELICc domains are responsible for PRRSV regulation.

FIG 5.

Identification of the LGP2 domains that regulate PRRSV replication. (A) Schematic diagram of full-length (amino acids 1 to 686) or truncated (designated 1-188, 1-517, 188-686, 350-686, and 545-686) LGP2 constructs, all tagged with Myc at the C terminus. Full-length LGP2 contains DExDC, HELICc, and RIG-I_C-RD domains. (B and C) Full-length LGP2 or other LGP2 truncations were transfected into Marc-145 cells. After 24 h of overexpression, the cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. (B) The expression of PRRSV N was detected by Western blotting. Asterisks mark the expressed Myc-fusion proteins of full-length LGP2 or other LGP2 fragments. The relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control. (C) qRT-PCR was used to detect the transcription levels of PRRSV N. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (D) Flag-tagged MDA5 and Myc-tagged full-length or truncated LGP2 were cotransfected into HEK293T for 24 h. IP assays with anti-Flag antibodies were performed to determine their interaction, and the immunoblots with Myc and Flag antibodies were shown. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. Asterisks mark the expressed Myc-fusion proteins of full-length or other truncated LGP2. The data are the results of three independent experiments (means ± SE). Significant differences are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

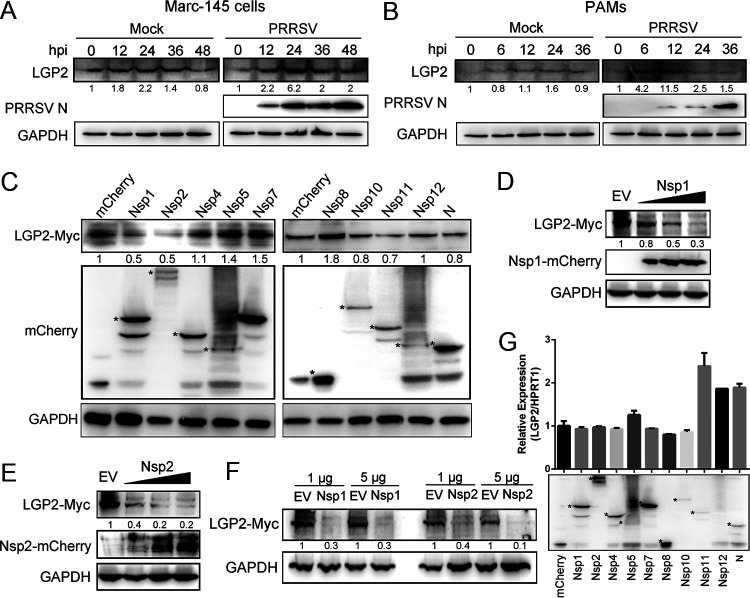

PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 reduce the expression of LGP2 protein.

Whether PRRSV antagonizes LGP2-mediated antiviral response to promote viral replication? First, we detected the kinetics of LGP2 protein expression in Marc-145 cells and PAMs following PRRSV infection. Western blot analysis identified a marked decrease in levels of LGP2 protein at 36 hpi in Marc-145 cells (Fig. 6A) and 24 hpi in PAMs (Fig. 6B). Many viruses can interfere with LGP2-mediated innate immune responses by interacting with LGP2. To screen the proteins of PRRSV responsible for LGP2 expression, mCherry-tagged viral proteins and Myc-tagged LGP2 were cotransfected into HEK293T cells. We observed the LGP2-Myc protein was remarkably reduced in the cells expressing Nsp1 and Nsp2, respectively (Fig. 6C). Moreover, we observed that the expression of LGP2 protein was decreased dose-dependent, accompanied by the increase of mCherry-tagged Nsp1 or Nsp2 (Fig. 6D and E). To further explore PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 reduce the protein expression of LGP2, different amounts of Nsp1 or Nsp2 and LGP2 plasmids were cotransfected into Marc-145 cells. Similarly, it was found that Nsp1 and Nsp2 dramatically degraded the expression of LGP2 in Marc-145 cells (Fig. 6F). To identify the effects of viral proteins on LGP2 mRNA level, 10 mCherry-tagged viral proteins were transfected into 3D4/21, respectively. The results showed no significant difference in the transcript level of LGP2 when 3D4/21 were transfected with Nsp1 and Nsp2 (Fig. 6G), which indicated the reduction of LGP2 was probably due to LGP2 protein degradation but not protein synthesis. These data indicated that PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 could reduce LGP2 protein expression.

FIG 6.

PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 reduce the expression of LGP2 protein. (A) Marc-145 cells were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h. Western blot analyzed the expression of LGP2 and PRRSV N. (B) PAMs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h. The protein levels of LGP2 and PRRSV N were determined using Western blot analysis. (C) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with mCherry-tagged PRRSV proteins (1.5 μg) plasmids and Myc-tagged LGP2 (1.5 μg) for 24 h. Cells were collected, and the expression of LGP2-myc and mCherry-fusion viral proteins were determined using Western blot analysis. Asterisks mark the expressed mCherry-fusion proteins of PRRSV nonstructural proteins and N protein. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (D) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the plasmids expressing Myc-tagged LGP2 (1.5 μg) and increased doses of mCherry-tagged PRRSV Nsp1 (1, 3, and 5 μg). After 24 h of transfection, cells were lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-mCherry, anti-Myc, and anti-GAPDH antibodies. (E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Myc-tagged LGP2 (1.5 μg) plasmid and increased doses of mCherry-tagged PRRSV Nsp2 (1, 3, and 5 μg) plasmids for 24 h. The expression of LGP2, Nsp2, and GAPDH was determined using anti-Myc, anti-mCherry, and anti-GAPDH antibodies. (F) Marc-145 cells were cotransfected with the plasmids expressing Myc-tagged LGP2 (1.5 μg) and different doses of mCherry-tagged PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 (1 and 5 μg). Western blotting was used to analyze the protein level of LGP2 and GAPDH. (G) Empty plasmid and plasmids expressing PRRSV Nsp1, Nsp2, Nsp4, Nsp5, Nsp7, Nsp8, Nsp10, Nsp11, Nsp12, and N were transfected into 3D4/21 cells, respectively. The transcript levels of LGP2 were determined using qRT-PCR. Western blotting was used to detect the expression of viral proteins. Asterisks mark the expressed mCherry-fusion proteins of PRRSV proteins. For the Western blot, the relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control. The data are the results of three independent experiments (means ± the SE). Significant differences are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

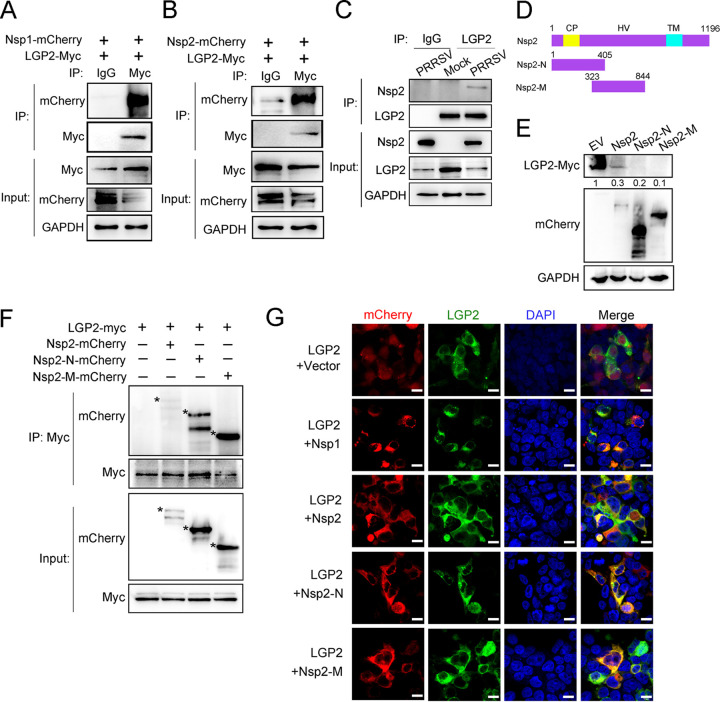

PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interact with LGP2.

To investigate the mechanism that PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 work on LGP2 protein, Myc-tagged LGP2 and mCherry-tagged Nsp1 or Nsp2 were overexpressed in HEK293T cells, and then coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays were performed. As expected, exogenous LGP2 immunoprecipitated with Nsp1 and Nsp2 in HEK293T cells, respectively (Fig. 7A and B). To further determine the endogenous interaction between LGP2 and Nsp2, PAMs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV, an LGP2 antibody immunoprecipitated PRRSV Nsp2 in PRRSV-infected cells (Fig. 7C). We then took Nsp2 as an example to map the Nsp2 domain(s) required for LGP2/Nsp2 interaction. We constructed two mCherry-tagged truncated Nsp2 (Nsp2-N and Nsp2-M) (Fig. 7D). Full-length or truncated Nsp2 and LGP2 plasmids were cotransfected into HEK293T. Surprisingly, we found that Nsp2 and its two truncations downregulated the expression of the LGP2 protein (Fig. 7E). Furthermore, co-IP assays revealed that both the truncated Nsp2-N and Nsp2-M could interact with LGP2 (Fig. 7F), indicating that Nsp2-N and Nsp2-M (amino acids 1 to 844) are responsible for the interaction with LGP2, thus resulting in the reduction of LGP2 protein level. To further identify the interaction between LGP2 and Nsp1, Nsp2, and Nsp2 truncations, GFP-tagged LGP2 and mCherry-tagged Nsp1, Nsp2, or Nsp2 truncations were cotransfected into HEK293T cells. It was shown that LGP2 colocalized with Nsp1, Nsp2, Nsp2-N, and Nsp2-M protein but not with an empty vector (Fig. 7F). We observed that LGP2 was visibly aggregated in the cytoplasm when cells were transfected with Nsp2 and Nsp2-N. Altogether, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 can interact with LGP2 and work on LGP2 degradation.

FIG 7.

PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interact with LGP2. (A) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with mCherry-tagged Nsp1 and Myc-tagged LGP2 for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Myc or IgG antibodies, and the immunoblots are shown with mCherry and Myc antibodies. IgG is a control. (B) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with mCherry-tagged Nsp2 and Myc-tagged LGP2 for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Myc or IgG antibodies, and the immunoblots are shown with mCherry and Myc antibodies. IgG is a control. (C) PAMs mock infected or infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with LGP2 antibody, and the immunoblots with Nsp2 and LGP2 antibodies are shown. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (D) Schematic diagrams of the full-length Nsp2 (amino acids 1 to 1196) and Nsp2 fragments (Nsp2-N, amino acids 1 to 405; Nsp2-M, amino acids 323 to 844), with an mCherry tag at the position of N terminus. HV, hypervariable region; TM, transmembrane domain; Nsp2-N, Nsp2 N-terminal; Nsp2-M, Nsp2 middle. (E) Empty vector or plasmids expressing mCherry-tagged Nsp2, Nsp2-N, and Nsp2-M were transfected into HEK293T cells with Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid, respectively. After transfection, cells were lysed and subjected to Western blotting to analyze the expression of LGP2-myc. GAPDH is included as an internal control. The relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control. (F) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Myc-tagged LGP2 and mCherry-tagged Nsp2 or its truncations. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a Myc antibody, and immunoblots of Myc and mCherry are shown. GAPDH served as an internal control. Asterisks mark the expressed mCherry-fusion proteins of full-length or other truncated Nsp2. (G) GFP-tagged LGP2 and mCherry-tagged Nsp1, Nsp2, Nsp2-N, or Nsp2-M were cotransfected into HEK293T for 24 h, respectively. Immunofluorescence analysis of the colocalization between LGP2 (green) and Nsp1, Nsp2, Nsp2-N, or Nsp2-M (red) was performed. Scale bar, 10 μm.

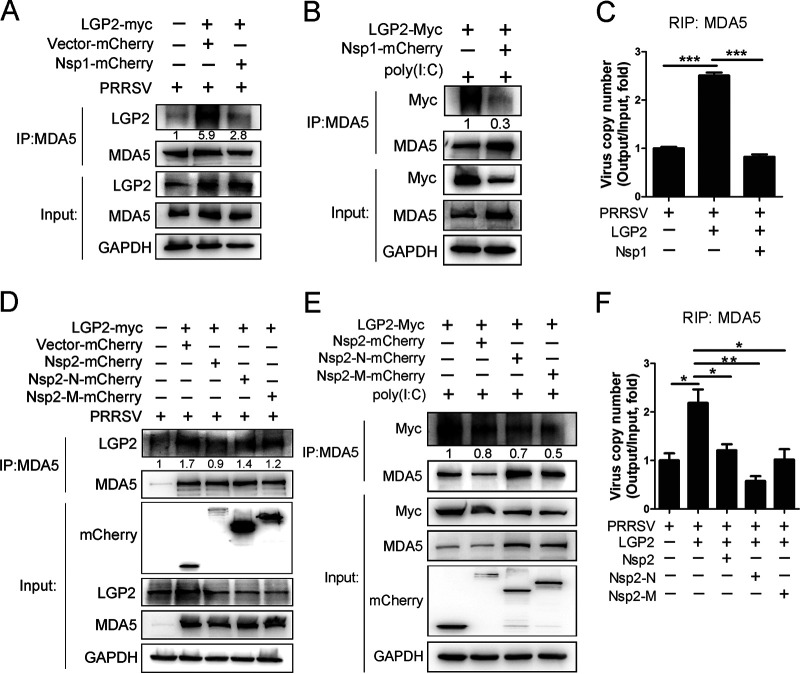

Nsp1 and Nsp2 decrease the recognition and interaction of viral RNA mediated by LGP2 and MDA5.

We have demonstrated that LGP2 potentially binds to MDA5 to facilitate MDA5-viral RNA interaction following PRRSV infection. However, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 reduce the protein expression of LGP2. Accordingly, we speculate that Nsp1 and Nsp2 can attenuate or block the interaction among LGP2, MDA5, and viral dsRNA via degrading LGP2 protein. To test this hypothesis, Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector or mCherry-tagged Nsp1 plasmids were cotransfected into Marc-145 cells, respectively, and then infected with PRRSV. Co-IP assays showed that the interaction between LGP2 and MDA5 was enhanced when LGP2 was overexpressed, while the interaction was impaired in cells coexpressing Nsp1 and LGP2 (Fig. 8A). Likewise, Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector or mCherry-tagged Nsp1 plasmids were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, respectively. After 24-h transfection, cells were stimulated with poly(I·C) for another 12h. The results showed that Nsp1 significantly weakened the interaction between LGP2 and MDA5 compared to the control group (Fig. 8B). RIP assays further demonstrated that LGP2 overexpression increased the rate of MDA5-RNA interaction. However, viral dsRNA enrichment was significantly decreased when cells were transfected with Nsp1 (Fig. 8C). We investigated whether Nsp2 and its truncations would interrupt the interaction between LGP2 and MDA5, reducing MDA5-bonded viral RNA. As expected, LGP2 immunoprecipitated by MDA5 was increased when LGP2 was overexpressed alone. However, this interaction was significantly reduced when cells were exposed to Nsp2, Nsp2-N, and Nsp2-M (Fig. 8D and E). Consistently, viral RNA precipitated by MDA5 was increased in LGP2-overexpressed cells. Compared with cells transfected with LGP2 plasmid alone, MDA5-viral RNA interaction declined in the presence of Nsp2, Nsp2-N, and Nsp2-M (Fig. 8F), which suggested Nsp2 and its truncations weaken LGP2 combining to MDA5, and even viral RNA recognition by MDA5. These data demonstrate that Nsp1 and Nsp2 attenuate the interaction between LGP2 and MDA5 following PRRSV infection, which decreases the recognition and recruitment of viral RNA by MDA5, ultimately leading to a decrease of antiviral immunity mediated by MDA5 and LGP2.

FIG 8.

Nsp1 and Nsp2 impaired the interaction among LGP2, MDA5, and viral RNA. (A) Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector or mCherry-tagged Nsp1 plasmids were cotransfected into Marc-145 cells, respectively, and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an MDA5 antibody, and immunoblots of LGP2 and MDA5 were shown. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (B) Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector or mCherry-tagged Nsp1 plasmids were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, respectively. After transfection, cells were stimulated with 2 μg/mL poly(I·C) for another 12 h. LGP2-myc was immunoprecipitated with an MDA5 antibody, and immunoblots with Myc and MDA5 antibodies are shown. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (C) Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector or mCherry-tagged Nsp1 plasmids were cotransfected into Marc-145 cells, respectively, and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an MDA5 antibody, immunoprecipitated RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and PRRSV copy number was detected using TaqMan real-time qPCR. (D) Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector, mCherry-tagged Nsp2, Nsp2-N, or Nsp2-M plasmids were cotransfected into Marc-145 cells, respectively, and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an MDA5 antibody, and immunoblots of LGP2 and MDA5 were shown. GAPDH is shown as an internal control. (E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Myc-tagged LGP2 and mCherry-tagged Nsp2, Nsp2-N, or Nsp2-M plasmids, respectively. Next, cells were exposed to 2 μg/mL poly(I·C) for another 12 h. IP assays with anti-MDA5 antibodies were performed to determine the interaction between LGP2 and MDA5. The LGP2-myc immunoblot with anti-Myc antibody is shown. GAPDH was included as an internal control. (F) Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmid and mCherry-empty vector, mCherry-tagged Nsp2 or Nsp2 truncations plasmids were cotransfected into Marc-145 cells, respectively, and then infected with PRRSV (MOI = 5) for 6 h. RIP assays with anti-MDA5 antibodies were performed to evaluate the interaction between MDA5 and viral RNA. PRRSV copy number was detected using TaqMan real-time qPCR. The columns represent the relative value of immunoprecipitated viral RNA (Output)/total viral RNA (Input). For the Western blot, the relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control. The data are the results of three independent experiments (means ± the SE). Significant differences are denoted by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

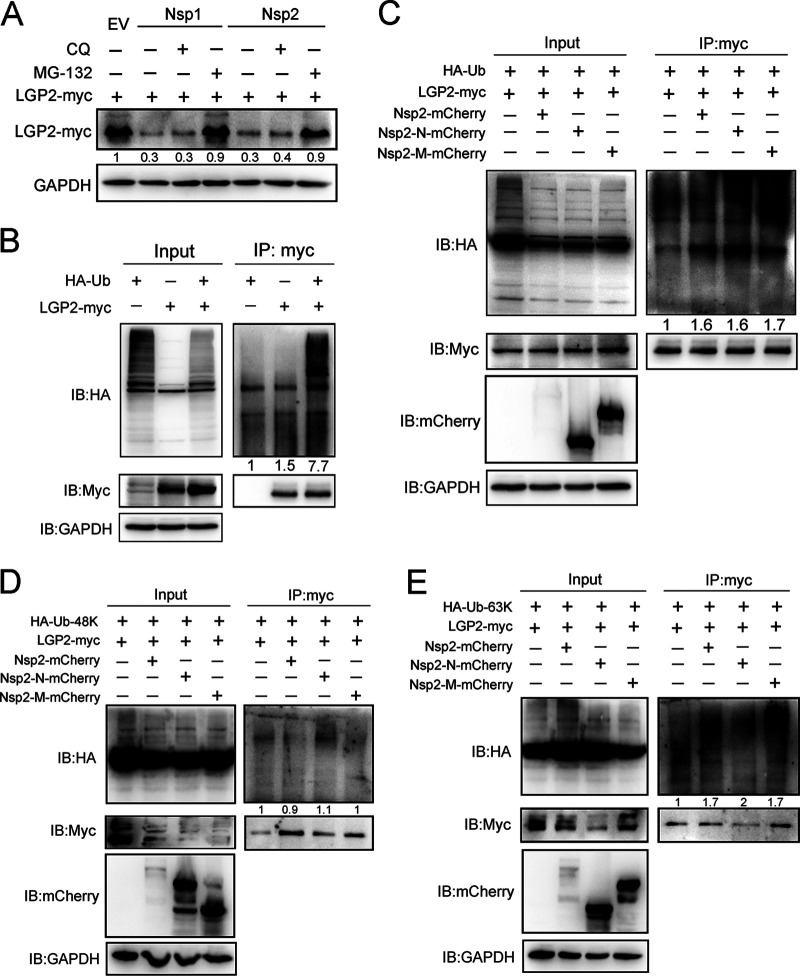

PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 promote the degradation of LGP2 via ubiquitin pathway.

To explore the mechanism that Nsp1 and Nsp2 degraded LGP2 protein expression, the ubiquitin-proteasome inhibitor MG-132 and lysosome inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) was added to cells at 24 h after LGP2 and Nsp1 or Nsp2 cotransfection. Interestingly, we found MG132 treatment in Nsp1- and Nsp2-transfected cells restored the LGP2 protein level comparable to the EV-transfected cells (Fig. 9A). Next, hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Ub and Myc-tagged LGP2 plasmids were cotransfected to HEK293T cells. After 24 h transfection, MG-132 was added to the cells for another 6 h. The co-IP assay was conducted using anti-myc antibody (Ab) and immunoblotting Ub using anti-HA Ab. LGP2 itself could be polyubiquitinated, as shown by the Western blot analysis of smeared higher-molecular-weight bands (Fig. 9B). To investigate whether viral Nsp2 affects the ubiquitination level of LGP2, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with full-length or truncated Nsp2 plasmids, along with LGP2 plasmid and Ub plasmid, for 24 h. IP assays revealed that Nsp2 and its truncations (Nsp2-N and Nsp2-M) promoted the ubiquitination level of LGP2, indicating PRRSV Nsp2 accelerated polyubiquitination of LGP2 protein (Fig. 9C). To further explore the ubiquitinated form that Nsp2 regulated LGP2, we used HA-Ub-48K and HA-Ub-63K plasmids under the condition that all lysine residues were substituted with arginine, except for the positions at 48 or 63. Compared to the control group, there was no change in K48-linked polyubiquitination of LGP2 in cells expressing Nsp2, Nsp2-N, or Nsp2-M (Fig. 9D). Remarkably, K63-linked ubiquitination of LGP2 was enhanced in the presence of Nsp2, Nsp2-N, or Nsp2-M, which suggested Nsp2 and its truncations (in the region from amino acids 1 to 844) were responsible for LGP2 degradation via K63-linked ubiquitination (Fig. 9E). Altogether, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 facilitate LGP2 degradation via the ubiquitin pathway.

FIG 9.

PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 promote LGP2 degradation via K63-linked polyubiquitination. (A) Plasmids expressing mCherry-tagged Nsp1 or Nsp2 and Myc-tagged Nsp2 were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, respectively. After 24 h of transfection, cells were mock treated or treated with chloroquine (CQ; 50 μM) and MG132 (10 μM) for 6 h. Cells were lysed for Western blotting using Myc antibody. GAPDH was included as an internal control. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin or Myc-tagged LGP2 alone or cotransfected with these two plasmids. After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for another 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a Myc antibody, and immunoblots of HA and Myc are shown. (C) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Myc-tagged LGP2 and mCherry-tagged Nsp2 or its truncations, together with HA-tagged ubiquitin. After 24 h, the cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM). Co-IP was used to detect the ubiquitination level of LGP2 using an antibody against Myc. Immunoblots are shown using antibodies against HA, Myc, mCherry, and GAPDH. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with mCherry-tagged Nsp2 or other Nsp2 fragments with Myc-tagged LGP2 and HA-tagged K48-linked ubiquitin for 24 h and were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for another 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a Myc antibody, and immunoblots of HA, Myc, and mCherry are shown using the indicated antibodies. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with mCherry-tagged Nsp2 or other Nsp2 fragments with Myc-tagged LGP2 and HA-tagged K63-linked ubiquitin for 24 h, followed by the treatment of MG132 (10 μM). Cells were lysed for co-IP using an antibody against Myc, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with HA, Myc, and mCherry antibodies. GAPDH was shown as an internal control. For the Western blot, the relative band density was normalized to the loading control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control.

DISCUSSION

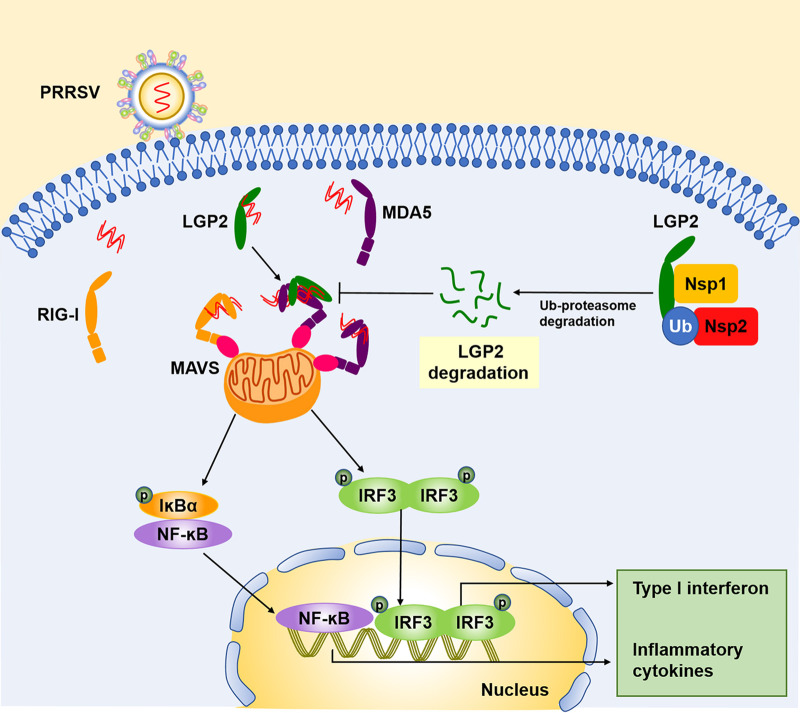

Here, we establish that LGP2 is a positive regulatory factor for anti-PRRSV infection. The mechanism encompasses the following (Fig. 10). First, LGP2 is prone to interact with MDA5 upon virus stimulation, thus reinforcing RIG-I- and MDA5-dependent cascade signaling, manifesting the activation of IRF3 and NF-κB during PRRSV infection. Second, the active signaling in LGP2-overexpressed cells facilitated the expression of type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines production, leading to the inhibition of PRRSV infection. Finally, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interacted with LGP2 and reduced the LGP2 protein expression via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in a dose-dependent manner. This report identified a neglected immune factor, LGP2, synergized with MDA5 to promote the host’s antiviral immune response and regulate PRRSV replication. Meanwhile, screened viral proteins Nsp1 and Nsp2 degraded LGP2 protein, antagonizing the innate immune-mediated by LGP2. Our study sheds light on the role of LGP2 in PRRSV infection and the interaction mechanism between host antiviral proteins and viruses.

FIG 10.

Schematic model of LGP2 regulation of PRRSV infection. Upon PRRSV infection, LGP2 could bind to MDA5 and promote recognition of dsRNA sensed by MDA5, subsequently accelerating downstream IRF3 and NF-κB activation, leading to increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFN, which contributes to suppression of PRRSV at the early stage of infection. Simultaneously, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interact with LGP2, and Nsp2 promotes the K63-linked polyubiquitination of LGP2, resulting in the degradation of LGP2 protein. These data elucidate a new mechanism of virus-host interaction.

The present study provides three novel insights regarding the role of LGP2 in PRRSV infection to be discussed. RIG-I and MDA5, both RLR members, have been widely studied and illustrated mechanisms of cytoplasmic virus recognition and innate immune responses (17). However, unlike other RLR members, LGP2 lacks two CARD domains that mediate interactions with essential adaptor proteins and activation of downstream signaling, leading to the different functional performances of LGP2. A few studies have demonstrated that LGP2 played an inhibitory role in RIG-I signaling, which decreased levels of IFN-β in response to virus infection, such as VSV, HCV, and SV (33, 34). Conversely, recent studies involving targeted gene disruption have suggested a positive role for LGP2 in IFN-β induction and antiviral signaling transduction. It was reported that LGP2 knockout mice were highly susceptible to EMCV infection, and NF-κB activation and IFN-β production were severely attenuated (25). Silencing of LGP2 significantly facilitated FMDV replication and reduced the expression of IFN-β (28). Besides, LGP2 overexpression also accelerated the antiviral response and IFN production in response to many viruses. It follows that the functions of LGP2 are divergent in response to different viruses, which remains controversial in antiviral immune responses. LGP2 antagonized PRRSV infection according to our experiments, as shown by the inhibition of PRRSV replication in LGP2-overexpressed cells and promotion of PRRSV replication in LGP2-silenced cells (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, LGP2 overexpression promoted the activation of NF-κB and RIG-I signaling at the early stage of PRRSV infection (Fig. 3E), ultimately leading to increased proinflammatory cytokines and IFN-β expression (Fig. 2). In summary, LGP2 was confirmed to participate in cellular immune responses against PRRSV infection, which suggested that LGP2 served as an important component of RLRs, together with RIG-I and MDA5, exhibited antiviral activity.

Second, how do they coordinate and balance their function in immune regulation? It has been reported that porcine LGP2 positively regulated porcine RIG-I and MDA5 in activated PAMs by interacting with RIG-I and MDA5, promoting dsRNA binding to MDA5 as well as RIG-I (35). It was demonstrated that LGP2 functioned in viral sensing through cooperation with MDA5 and subsequent MDA5 antiviral innate immune responses in response to many viruses, such as Tembusu virus, MVA, and avian influenza viruses (26, 36–38). In our study, we are interested in the preference of LGP2 for the interaction with RIG-I or MDA5 following PRRSV infection. We performed the experiments using Marc-145 cells employed LGP2 and RIG-I or MDA5 overexpression. Co-IP analysis implied that LGP2 was more likely to bind MDA5 upon PRRSV infection, as shown by increased MDA5 protein precipitated by LGP2 (Fig. 3A, C, and D). Generally, RIG-I and MDA5 have been reported to sense PRRSV RNA and bring downstream cascade effects. However, the roles of LGP2 in antiviral signaling are easily overlooked (39). In the present study, LGP2 may positively regulate antiviral responses by functioning upstream of RIG-I and MDA5, especially in MDA5, leading to the activation of RIG-I and NF-κB signaling and the production of proinflammatory cytokines and IFN-β, which suggests LGP2 is closely related to PRRSV-induced innate immunity and LGP2 has potential to mediate and amplify signaling pathways triggered by RIG-I or MDA5.

Meanwhile, we also demonstrated DExDc and HELICc domains interacted with MDA5 and are required for PRRSV inhibition (Fig. 5B, C, and D). DExDc and HELICc domains contain RNA binding and helicase superfamily ATP binding domains. It was reported that LGP2 ATP hydrolysis promotes dsRNA recognition and enhances MDA5-mediated IFN signaling (15). Accordingly, it is the possible reason why the two regions restrained PRRSV replication. To investigate whether LGP2 promotes the recruitment of dsRNA to MDA5, RIP and confocal assays revealed that LGP2 overexpression could increase the initial rate of MDA5-viral RNA interaction (Fig. 4). Once Nsp1 and Nsp2 degraded LGP2, the rate of MDA5-viral RNA interaction was concomitantly decreased (Fig. 8C and F). The activation of MDA5 manifests the formation of shorter MDA5 filaments, which leads to greater MAVS activation and antiviral signaling. Upon PRRSV infection, LGP2 acts synergistically with MDA5, manifesting enhanced MDA5-RNA interaction. Accordingly, we speculate LGP2 also can accelerate and stabilize the formation of shorter MDA5 filaments to achieve amplifying antiviral response. However, the exact roles and mechanisms of LGP2 in RNA recognition and synergism with MDA5 in antiviral signaling need further investigation.

Third, PRRSV can evade the host’s innate immune responses by degrading host antiviral proteins. PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 are the most common nonstructural proteins that inhibit the host immune response (10). Particularly, the crucial elements in RIG-I signaling are usually disrupted by Nsp1 and Nsp2, such as NEMO, MAVS, TBK1, and IRF3, thus impairing antiviral signal transduction (8, 10, 40). In this study, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 degraded LGP2 protein dose-dependent (Fig. 6D and E). We then demonstrated the potential mechanism is that Nsp1 and Nsp2 had an interaction with LGP2 (Fig. 7A and B), thus facilitating the LGP2 ubiquitination and LGP2 degradation (Fig. 9A to C). K48-linked ubiquitination is responsible for proteasome degradation, whereas K63-linked ubiquitination is involved in innate immune signal transduction (41). Previous studies had demonstrated that the PRRSV Nsp2 OTU domain possesses deubiquitinating activity (42), but we identified that PRRSV Nsp2 facilitated K63-linked polyubiquitination of LGP2 (Fig. 9E). We speculate that another protein combines with nsp2 and LGP2 to form complexes. These proteins may be related to ubiquitination, and Nsp2 will promote the interaction between ubiquitin-related proteins and LGP2 to promote LGP2 ubiquitination. However, whether there are ubiquitin proteins participating in this process still needs further investigation by IP-MS or co-IP-MS. In brief, we first identified LGP2 as a positive regulator in RIG-I signaling, which involves host anti-PRRSV immune, but the precise functions of LGP2 are necessary for us to focus on.

In conclusion, we proposed a possible mechanism for LGP2-mediated antiviral function. Upon PRRSV infection, LGP2 was prone to bind to MDA5 and enhanced the enrichment of viral RNA on MDA5, which facilitated downstream IRF3 and NF-κB activation, leading to increased proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFN expression, ultimately inhibiting PRRSV at the early stage of infection. On the contrary, PRRSV Nsp1 and Nsp2 interacted with LGP2, resulting in the degradation of LGP2 through the Ub-proteasome pathway. Our work demonstrates that LGP2 manifested a positive antiviral effect against PRRSV infection for the first time. These findings help us understand the host antiviral responses to PRRSV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Marc-145 cells derived from African green monkey kidney cells are permissive to PRRSV infection, which were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Corning, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA) at 37°C in 5% CO2. HEK293T cells were also cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2. 3D4/21 cells, an immortalized macrophage line, were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) containing 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2. PAMs were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of piglets using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2. Four PRRSV strains (CHR6, SD16, XJ17-5, and Li11) were used in this study. CHR6 (Classical North American type PRRSV strain) and Li11 (Highly pathogenic PRRSV strain) were preserved in our laboratory. SD16 (Classical North American type PRRSV strain) and XJ17-5 (highly pathogenic PRRSV strain) were provided by Nanhua Chen from Yangzhou University. All PRRSV strains were propagated in Marc-145 cells and titrated as the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50).

Expression vector construction and transfection.

The LGP2 genes were obtained from PAMs cDNA and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1-myc vector (MY1023; EK-Bioscience, China) containing a myc tag or pcDNA3.1-GFP vector containing a GFP tag. Five fragments of LGP2—designated fragment 1-188 (residues 1 to 188), fragment 1-517 (residues 1 to 517), fragment 188-686 (residues 188 to 686), fragment 350-686 (residues 350 to 686), and fragment 545-686 (residues 545 to 686)—were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1-Myc vector, respectively. The cDNAs encoding RIG-I and MDA5 were obtained from PAM cDNA and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1-flag vector (EK-Bioscience) to provide an amino-terminal FLAG epitope tag. The PRRSV nsp1-nsp12, GP2a, GP3, GP4, GP5, E, and N genes were amplified from the PRRSV CHR6 strain and cloned into vector mCherry-N (632523, TaKaRa, Japan) with an N-terminal mCherry tag. Two fragments of Nsp2, designated Nsp2-N and Nsp2-M, were cloned into vector mCherry-N. HA-Ub plasmid and the HA-Ub 48K/63K mutant plasmids were provided by prof. Yaosheng Chen from Sun Yat-sen University. Marc-145 cells, 3D4/21 cells, and HEK293T cells were seeded in six-well plates and grown to 60 yo 70% confluence, and cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol for 24 h, followed by cell harvesting for various analyses.

RNA interference.

Small interference RNAs (siRNAs) against LGP2 and scrambled siRNA (siNC) were designed and synthesized by GenePharma. Adherent PAMs at 2 × 106 cells/well were transfected with the indicated siRNAs (Table 1) at a final concentration of 10 nM using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were infected with PRRSV.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of siRNAs in this study

| siRNA | siRNA sequence (5′–3′) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sense | Antisense | |

| si-LGP2-1 | GGGACCAGCAAGAAGUGAUTT | AUCACUUCUUGCUGGUCCCTT |

| si-LGP2-2 | GCAUCUGGAGACUGUGGAUTT | AUCCACAGUCUCCAGAUGCTT |

| si-LGP2-3 | GCCAGUACCUGAAGCAUAATT | UUAUGCUUCAGGUACUGGCTT |

| si-NC | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription PCR.

qRT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA expression of PRRSV N, LGP2, IFN-β, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. Total RNA was extracted from cells at the indicated times postinfection using TRIzol reagent (Tiangen, China). As described in the instructions, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using HiScript III RT SuperMix (Vazyme, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using QuantStudio3 (Applied Biosystems) and ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China). The reverse-transcription primers are listed in Table 2. Data were normalized to GAPDH or HPRT1 mRNA levels in each sample and were carried out in triplicate. Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for qRT-PCR

| Primera | Sequence (5′–3′)b |

|---|---|

| ORF7 (N)-F | AAAACCAGTCCAGAGGCAAG |

| ORF7 (N)-R | CGGATCAGACGCACAGTATG |

| pIFN-β-F | AGCACTGGCTGGAATGAAACCG |

| pIFN-β-R | CTCCAGGTCATCCATCTGCCCA |

| mIFN-β-F | GCAATTGAATGGAAGGCTTGA |

| mIFN-β-R | CAGCGTCCTCCTTCTGGAACT |

| mIL-6-F | AGAGGCACTGGCAGAAAAC |

| mIL-6-R | TGCAGGAACTGGATCAGGAC |

| pIL-6-F | CTGCTTCTGGTGATGGCTACTG |

| pIL-6-R | GGCATCACCTTTGGCATCTT |

| mIL-1β-F | GGAAGACAAATTGCATGG |

| mIL-1β-R | CCCAACTGGTACATCAGCAC |

| pIL-1β-F | CCCAAAAGTTACCCGAAGAGG |

| pIL-1β-R | TCTGCTTGAGAGGTGCTGATG |

| mTNF-α-F | TCTGTCTGCTGCACTTTGGAGTGA |

| mTNF-α-R | TTGAGGGTTTGCTACAACATGGGC |

| pTNF-α-F | ACTCGGAACCTCATGGACAG |

| pTNF-α-R | AGGGGTGAGTCAGTGTGACC |

| pLGP2-F | CAGATCCTACAGGCTGAGCG |

| pLGP2-R | TGGGACCCTTGAACTGCTTC |

| pHPRT1-F | TGGAAAGAATGTCTTGATTGTTGAAG |

| pHPRT1-R | ATCTTTGGATTATGCTGCTTGACC |

| mGAPDH-F | TGACAACAGCCTCAAGATCG |

| mGAPDH-R | GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer. The letter “m” indicates a green monkey gene; the letter “p” indicates a pig gene.

Pig gene sequences, green monkey gene sequences, and PRRSV gene sequences were downloaded from GenBank.

Western blot.

Cells were harvested at indicated time points after treatment and were lysed in a cell lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) for at least 20 min on ice. The protein concentrations in each sample were quantified. Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were subjected to 8 to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electrotransferred to polyvinyl difluoride membrane (Merck Millipore, USA). Membranes were incubated in 5% skim milk (Sangon Biotech, China) in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) at room temperature. After 1 h of membrane blocking, the membranes were incubated with individual primary antibodies at 1:1,000 at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed using TBST buffer three times, and immunoblots were probed using the indicated secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:5,000. The immunoblotted proteins were visualized by using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (NCM Biotech, China). Most Western blot data were quantified using Image J. The relative band density was normalized to the control GAPDH and then compared to the corresponding control. Antibodies used in this study were listed as follows: anti-PRRSV N (4A5) antibody (9041) was purchased from MEDIAN Diagnostics (MEDIAN, Republic of Korea). Anti-mCherry antibody (ab183628) was purchased from Abcam (Abcam, England). GAPDH (14C10) rabbit MAb (2118), NF-κB p65 (D14E12) rabbit MAb (8242), Myc-tag (9B11) mouse MAb (2276), histone H3 (D1H2) rabbit MAb (4499), Rig-I (D14G6) rabbit MAb, and IRF3 (D6I4C) rabbit MAb were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). LGP2 Rabbit polyclonal antibody (11355), MDA5 rabbit polyclonal antibody (21775), Flag tag rabbit recombinant antibody (80010), and HA tag rabbit polyclonal antibody (51064) were purchased from Proteintech Group (Proteintech, USA). Phospho-IRF3 (Ser396) monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) was provided by Jianzhong Zhu from Yangzhou University. PRRSV Nsp2 antibody was provided by Yanhua Li from Yangzhou University.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Cells were transfected or cotransfected with indicated plasmids for 36 h, followed by cell harvesting for co-IP. Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in a cell lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) with the supplement of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime, China). Immunoprecipitation was performed using a Dynabeads protein G immunoprecipitation kit (10007D; Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First, 3 μg of indicated tag-antibodies were added to 30 μL of magnetic beads for 1 h at room temperature. The supernatant was removed, and cell lysates containing the antigen were incubated with magnetic bead-Ab complex for 1 h at room temperature. After the magnetic bead-Ab-Ag complexes were washed three times, the residues were eluted with SDS sample buffer and separated by 8 to 12% SDS-PAGE. The precipitates and whole-cell lysates were performed immunoblotting as described above.

RNA immunoprecipitation.

Marc-145 cells were transfected with empty vector or LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, followed by PRRSV infection at an MOI of 5 for another 3 or 6 h. Cells were collected and lysed in RIP lysis buffer supplemented with RNase inhibitor (1:100). Magnetic beads were first incubated with 5 μg of MDA5 antibody for 1 h. Then, cell lysates were incubated with MDA5 beads overnight at 4°C. The coprecipitated RNAs were extracted using 1 mL of TRIzol reagent. After that, RNA was reverse transcribed and detected by qRT-PCR or PCR with corresponding primers.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were transfected by indicated plasmids or infected with PRRSV at indicated time points, and then cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (Biosharp, China) for 10 min and permeabilized for 15 min using 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS (Solarbio, China). After a rinsing with PBS, the cells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, cells were incubated with corresponding antibodies overnight at 4°C. After three washings with PBS, the cells were incubated with indicated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Beyotime) was used to stain the cell nucleus for an additional 5 min. All images were captured and processed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (U-HGLGPS; Olympus, Japan) or a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 880NLO; Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Detection of gene expression of interferon and inflammatory cytokines.

Marc-145 cells and 3D4/21 cells were mock transfected or transfected with LGP2 for 24 h, and then cells were infected with CHR6 (MOI = 1) for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. To assess the effects of LGP2 overexpression on the transcription of interferon and inflammatory cytokines in PRRSV-infected cells, qRT-PCR was used to measure the relative expression of IFN-β, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α as described above. Three replicates were included for each treatment.

Luciferase reporter assays.

Marc-145 cells and HEK293T were cultured in 24-well plates and grown to 60%–70% confluence. Then cells were cotransfected with 2,000 ng of LGP2 expressing plasmid or empty vector, 500 ng of IFN-β luciferase plasmid, and 100 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmid, which served as an internal control. After 24 h posttransfection, cells were mock infected or infected with PRRSV for another 24 h or mock stimulated or stimulated with poly(I·C) for another 6 h. Subsequently, cells were lysed with luciferase lysis buffer, and the luciferase activity was measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative luciferase activity was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase. Three replicates were included for each treatment.

Nuclear/cytosol fractionation assays.

Marc-145 cells were transfected with empty vector or LGP2 plasmid for 24 h, and cells were infected with PRRSV (MOI = 1) cell were collected at 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hpi. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, nuclear and cytoplasmic protein samples were extracted from harvested cells using a nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit (Beyotime). The protein expressions of IRF3, NF-κB, RIG-I, and PRRSV N in the nucleus and cytoplasm were detected by Western blotting, respectively. Histone H3 was the internal nuclear control, and GAPDH was the cytoplasmic internal control.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed with at least three independent replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Data are presented as means ± the standard errors of the means. Statistical significance was determined using Student t test or one-way analysis of variance, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210804), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1800301), the 111 Project D18007, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). Z.Z. is supported by the LvYangJinfeng Program of Yangzhou City.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Z.Z. and X.L. conceived and designed the study. Z.Z. and M.Z. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. L.Y., Y.X., H.Z., Z.L., and P.L. coordinated the study. Z.Z. and X.L. contributed to the interpretation of the data and took part in the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xiangdong Li, Email: 007352@yzu.edu.cn.

Tom Gallagher, Loyola University Chicago.

REFERENCES

- 1.Montaner-Tarbes S, Del Portillo HA, Montoya M, Fraile L. 2019. Key gaps in the knowledge of the porcine respiratory reproductive syndrome virus (PRRSV). Front Vet Sci 6:38. 10.3389/fvets.2019.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dokland T. 2010. The structural biology of PRRSV. Virus Res 154:86–97. 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo D, Song C, Sun Y, Du Y, Kim O, Liu HC. 2010. Modulation of host cell responses and evasion strategies for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res 154:48–60. 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim O, Sun Y, Lai FW, Song C, Yoo D. 2010. Modulation of type I interferon induction by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and degradation of CREB-binding protein by nonstructural protein 1 in MARC-145 and HeLa cells. Virology 402:315–326. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beura LK, Sarkar SN, Kwon B, Subramaniam S, Jones C, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1β modulates host innate immune response by antagonizing IRF3 activation. J Virol 84:1574–1584. 10.1128/JVI.01326-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Zheng Z, Zhou P, Zhang B, Shi Z, Hu Q, Wang H. 2010. The cysteine protease domain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 2 antagonizes interferon regulatory factor 3 activation. J Gen Virol 91:2947–2958. 10.1099/vir.0.025205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagong M, Lee C. 2011. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein modulates interferon-beta production by inhibiting IRF3 activation in immortalized porcine alveolar macrophages. Arch Virol 156:2187–2195. 10.1007/s00705-011-1116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Han M, Kim C, Calvert JG, Yoo D. 2012. Interplay between interferon-mediated innate immunity and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Viruses 4:424–446. 10.3390/v4040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang R, Nan Y, Yu Y, Yang Z, Zhang YJ. 2013. Variable interference with interferon signal transduction by different strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Microbiol 166:493–503. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Music N, Gagnon CA. 2010. The role of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus structural and nonstructural proteins in virus pathogenesis. Anim Health Res Rev 11:135–163. 10.1017/S1466252310000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Z, Liu P, Yuan L, Lian Z, Hu D, Yao X, Li X. 2021. Induction of UPR promotes interferon response to inhibit PRRSV replication via PKR and NF-κB pathway. Front Microbiol 12:757690. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.757690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loo YM, Gale M, Jr.. 2011. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity 34:680–692. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Matsumoto K, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Foy E, Loo YM, Gale M, Jr, Akira S, Yonehara S, Kato A, Fujita T. 2005. Shared and unique functions of the DExD/H-box helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in antiviral innate immunity. J Immunol 175:2851–2858. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2009. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev 227:75–86. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruns AM, Pollpeter D, Hadizadeh N, Myong S, Marko JF, Horvath CM. 2013. ATP hydrolysis enhances RNA recognition and antiviral signal transduction by the innate immune sensor, laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2). J Biol Chem 288:938–946. 10.1074/jbc.M112.424416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esser-Nobis K, Hatfield LD, Gale M, Jr.. 2020. Spatiotemporal dynamics of innate immune signaling via RIG-I-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:15778–15788. 10.1073/pnas.1921861117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. 2009. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol Rev 227:54–65. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Z, Zhang X, Wang G, Zheng H. 2014. The Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology 2: emerging insights into the controversial functions of this RIG-I-like receptor. Biomed Res Int 2014:960190–960197. 10.1155/2014/960190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malur M, Gale M, Jr, Krug RM. 2012. LGP2 downregulates interferon production during infection with seasonal human influenza A viruses that activate interferon regulatory factor 3. J Virol 86:10733–10738. 10.1128/JVI.00510-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Childs K, Randall R, Goodbourn S. 2012. Paramyxovirus V proteins interact with the RNA Helicase LGP2 to inhibit RIG-I-dependent interferon induction. J Virol 86:3411–3421. 10.1128/JVI.06405-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothenfusser S, Goutagny N, DiPerna G, Gong M, Monks BG, Schoenemeyer A, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Fitzgerald KA. 2005. The RNA helicase Lgp2 inhibits TLR-independent sensing of viral replication by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I. J Immunol 175:5260–5268. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh T, Kato H, Kumagai Y, Yoneyama M, Sato S, Matsushita K, Tsujimura T, Fujita T, Akira S, Takeuchi O. 2010. LGP2 is a positive regulator of RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:1512–1517. 10.1073/pnas.0912986107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin X, Riva L, Pu Y, Martin-Sancho L, Kanamune J, Yamamoto Y, Sakai K, Gotoh S, Miorin L, De Jesus PD, Yang CC, Herbert KM, Yoh S, Hultquist JF, Garcia-Sastre A, Chanda SK. 2021. MDA5 governs the innate immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in lung epithelial cells. Cell Rep 34:108628. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huo H, Zhao L, Wang D, Chen X, Chen H. 2019. LGP2 plays a critical role in MDA5-mediated antiviral activity against duck enteritis virus. Mol Immunol 116:160–166. 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyamoto M, Komuro A. 2017. PACT is required for MDA5-mediated immunoresponses triggered by cardiovirus infection via interaction with LGP2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 494:227–233. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaloye J, Roger T, Steiner-Tardivel QG, Le Roy D, Knaup Reymond M, Akira S, Petrilli V, Gomez CE, Perdiguero B, Tschopp J, Pantaleo G, Esteban M, Calandra T. 2009. Innate immune sensing of modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) is mediated by TLR2-TLR6, MDA-5 and the NALP3 inflammasome. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000480. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Hei L, Zhong J. 2017. Laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2) plays an essential role in hepatitis C virus infection-induced interferon responses. Hepatology 65:1478–1491. 10.1002/hep.29050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu Z, Li C, Du X, Wang G, Cao W, Yang F, Feng H, Zhang X, Shi Z, Liu H, Tian H, Li D, Zhang K, Liu X, Zheng H. 2017. Foot-and-mouth disease virus infection inhibits LGP2 protein expression to exaggerate inflammatory response and promote viral replication. Cell Death Dis 8:e2747. 10.1038/cddis.2017.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Feinman LJ, Garcia-Sastre A, Shaw ML. 2018. Paramyxovirus V proteins interact with the RIG-I/TRIM25 regulatory complex and inhibit RIG-I signaling. J Virol 92. 10.1128/JVI.01960-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez KR, Horvath CM. 2014. Paramyxovirus V protein interaction with the antiviral sensor LGP2 disrupts MDA5 signaling enhancement but is not relevant to LGP2-mediated RLR signaling inhibition. J Virol 88:8180–8188. 10.1128/JVI.00737-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez Pulido M, Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Martinez-Salas E, Garcia-Sastre A, Sobrino F, Saiz M. 2018. Innate immune sensor LGP2 is cleaved by the Leader protease of foot-and-mouth disease virus. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007135. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murali A, Li X, Ranjith-Kumar CT, Bhardwaj K, Holzenburg A, Li P, Kao CC. 2008. Structure and function of LGP2, a DEX(D/H) helicase that regulates the innate immunity response. J Biol Chem 283:15825–15833. 10.1074/jbc.M800542200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quicke KM, Kim KY, Horvath CM, Suthar MS. 2019. RNA helicase LGP2 negatively regulates RIG-I signaling by preventing TRIM25-mediated caspase activation and recruitment domain ubiquitination. J Interferon Cytokine Res 39:669–683. 10.1089/jir.2019.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moresco EM, Beutler B. 2010. LGP2: positive about viral sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:1261–1262. 10.1073/pnas.0914011107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li S, Yang J, Zhu Y, Wang H, Ji X, Luo J, Shao Q, Xu Y, Liu X, Zheng W, Meurens F, Chen N, Zhu J. 2021. Analysis of porcine RIG-I like receptors revealed the positive regulation of RIG-I and MDA5 by LGP2. Front Immunol 12:609543. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.609543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruns AM, Horvath CM. 2015. LGP2 synergy with MDA5 in RLR-mediated RNA recognition and antiviral signaling. Cytokine 74:198–206. 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li T, Zhai X, Wang W, Lin Y, Xing B, Wang J, Wang X, Miao R, Zhang T, Wei L. 2021. Regulation of MDA5-dependent anti-Tembusu virus innate immune responses by LGP2 in ducks. Vet Microbiol 263:109281. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liniger M, Summerfield A, Zimmer G, McCullough KC, Ruggli N. 2012. Chicken cells sense influenza A virus infection through MDA5 and CARDIF signaling involving LGP2. J Virol 86:705–717. 10.1128/JVI.00742-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]