ABSTRACT

Metagenomic sequencing is a swift and powerful tool to ascertain the presence of an organism of interest in a sample. However, sequencing coverage of the organism of interest can be insufficient due to an inundation of reads from irrelevant organisms in the sample. Here, we report a nuclease-based approach to rapidly enrich for DNA from certain organisms, including enterobacteria, based on their differential endogenous modification patterns. We exploit the ability of taxon-specific methylated motifs to resist the action of cognate methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases that thereby digest unwanted, unmethylated DNA. Subsequently, we use a distributive exonuclease or electrophoretic separation to deplete or exclude the digested fragments, thus enriching for undigested DNA from the organism of interest. As a proof of concept, we apply this method to enrich for the enterobacteria Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica by 11- to 142-fold from mock metagenomic samples and validate this approach as a versatile means to enrich for genomes of interest in metagenomic samples.

IMPORTANCE Pathogens that contaminate the food supply or spread through other means can cause outbreaks that bring devastating repercussions to the health of a populace. Investigations to trace the source of these outbreaks are initiated rapidly but can be drawn out due to the labored methods of pathogen isolation. Metagenomic sequencing can alleviate this hurdle but is often insufficiently sensitive. The approach and implementations detailed here provide a rapid means to enrich for many pathogens involved in foodborne outbreaks, thereby improving the utility of metagenomic sequencing as a tool in outbreak investigations. Additionally, this approach provides a means to broadly enrich for otherwise minute levels of modified DNA, which may escape unnoticed in metagenomic samples.

KEYWORDS: DNA, foodborne outbreaks, metagenomics, methylation, modifications, restriction endonuclease, sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Foodborne pathogen outbreaks can be a major public health and agroeconomic burden (1, 2). According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 10 people are victim to foodborne illnesses every year (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety). When such outbreaks occur, food and agricultural safety organizations are tasked with determining the responsible contaminated food, the pathogen causing the illness, and the source of this pathogen so that required measures can be taken to remove implicated food products from commerce and perform remediation steps to prevent further illnesses (1–5).

Specific strains of enterobacteria are among common pathogens linked to foodborne illnesses (e.g., Salmonella enterica, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli) (1–7). In an outbreak setting, pathogen detection and identification are often achieved through serotype testing, DNA marker amplification, or targeted sequencing of genomic loci, but these methods sometimes provide insufficient information to trace the organism back to its source (1, 3–5, 7, 8). Thus, strain and substrain level information encoded by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can have great value in tracking and matching a pathogen to its environmental source (1, 9). Whole-genome sequencing (WGS), unlike targeted methods, provides this information and is used at various checkpoints between the farm and consumer to monitor and control contamination in produce (1–5, 10).

WGS of an outbreak pathogen is obtained through either a culture-dependent or a culture-independent approach, the first of which can add many days and substantial cost to an investigation, depending on how simple it is to isolate the pathogen in question and the pathogen load in the sample (1, 3–5, 7). In a culture-independent approach, shotgun sequencing is performed on the sample (produce, food, soil, plant) potentially containing the pathogen, and assembly of the pathogen’s DNA allows for rapid strain-level identification without the need for isolation. While shotgun WGS is recognized as a powerful tool for this application, it comes with the limitation that a sample needs to contain a sufficient load of the pathogen for high enough coverage of the genome to SNP map the genome. Often these samples, instead, contain irrelevant prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA that far exceeds that of the relevant strain. This leads to low-coverage assemblies of the pathogen or increased cost due to excess sequencing of a sample (11–16).

Methods exist to deplete “host” or eukaryotic DNA and enrich for prokaryotic DNA. Some commercial kits selectively lyse eukaryotic (mostly mammalian) cells and degrade accessible DNA through enzymatic or chemical means before purifying DNA from the remaining cells (4, 14, 15). While these offer substantial depletion of eukaryotic DNA, they may fall short in several ways as follows: (i) unable to digest (and therefore deplete) cells with robust cell walls such as fungi, (ii) unable to enrich for prokaryotic DNA post-DNA extraction, (iii) unable to preserve prokaryotic cell-free DNA in a sample, and (iv) unable to deplete irrelevant prokaryotic DNA.

Other methods deplete eukaryotic DNA post-DNA extraction by binding and sequestering this DNA due to the differential presence of methylation patterns between prokaryotes and eukaryotes (11–13, 15, 16). One commercial kit takes advantage of the increased presence of CpG (N6 position of cytosine) methylation in eukaryotes and uses an engineered methyl-CpG binding domain conjugated to an antibody to remove CpG methylated DNA (16). However, studies frequently report weak enrichment through this method, likely due to the presence of large stretches of eukaryotic DNA that are not methylated (14, 15). Additionally, many eukaryotes, such as Caenorhabditis elegans, exhibit predominantly unmodified DNA (17, 18). A different protocol makes use of methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII in noncatalytic conditions to bind and enrich for non-CpG methylated (and therefore prokaryotic) DNA (12). The same group also applied this paradigm to a different restriction enzyme, DpnI, that selectively targets methylated 5′-GATC-3′ motifs (N6 position of adenine) (11). These motifs are methylated by Dam, a type-II methyltransferase widespread in Gammaproteobacteria (of which E. coli, S. enterica and Vibrio cholerae are members) and not found in eukaryotes (19–24). While offering substantial enrichment, these protocols are time and cost prohibitive, as they involve using 1:1 stoichiometric amounts of enzyme to the to-be-enriched substrate DNA, modification of the enzyme by biotinylation, and a final dialysis step (11, 12).

Here, we describe and implement restriction endonuclease-based modification-dependent enrichment (REMoDE) of DNA, an approach that rapidly and cost-effectively enriches for DNA from E. coli and S. enterica in metagenomic samples. We, too, rely on the presence of Dam and Dcm methyltransferases in E. coli and S. enterica and the near complete methylation of all instances of their target motifs in E. coli and S. enterica (23–25). These methyltransferases methylate 5′-GATC-3′ and 5′-CCWGG-3′, respectively (methylated base underlined; W = A or T) (23, 25–27). We employ the highly specific action of methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes MboI (5′-GATC-3′) and PspGI and EcoRII (both 5′-CCWGG-3′) that cleave only unmethylated instances of the motif (28). When applied to a mixed population of DNA that is unmethylated or methylated at these motifs, we observe a segregation of DNA into either short or long genomic-length fragments, respectively. Finally, we select for the longer fragments of DNA either using electrophoretic separation or by taking advantage of the highly distributive nature of the T5 exonuclease (29). When applied to a reaction mixture with different distributions of long and short DNA, electrophoretic separation provides a clean size separation, albeit requiring an additional gel isolation step, while the T5 exonuclease reaction is a cost-effective approach (~$0.03 additional cost/sample) that can be adjusted to rapidly deplete short DNA in a same tube reaction. We observe an 11- to 142-fold enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica DNA in a metagenomic sample relative to an untreated version of the same sample. This method can be extended to other Dam and Dcm methylated organisms and may even be extrapolated to organisms with other methylation patterns as pointed out in the discussion.

RESULTS

Figure 1 provides an overview of the restriction-enzyme-based scheme that we have used to enrich for DNAs methylated at defined sites.

FIG 1.

Schematic of the pipeline for endonuclease- and exonuclease-based enrichment of methylated DNA. A metagenomic sample containing DNA that is and is not Dam and Dcm methylated is treated with methylation-sensitive enzymes. The unmethylated DNA is digested to short fragments while the methylated DNA remains long and intact. Size selection for longer fragments is performed with either electrophoretic separation or a distributive exonuclease (which preferentially degrades short fragments). The enriched sample is then sequenced.

As a proof of principle, we elected to test this approach with DNA from organisms readily available in the laboratory and that we knew were Dam and Dcm methylated (E. coli) or unmethylated (C. elegans).

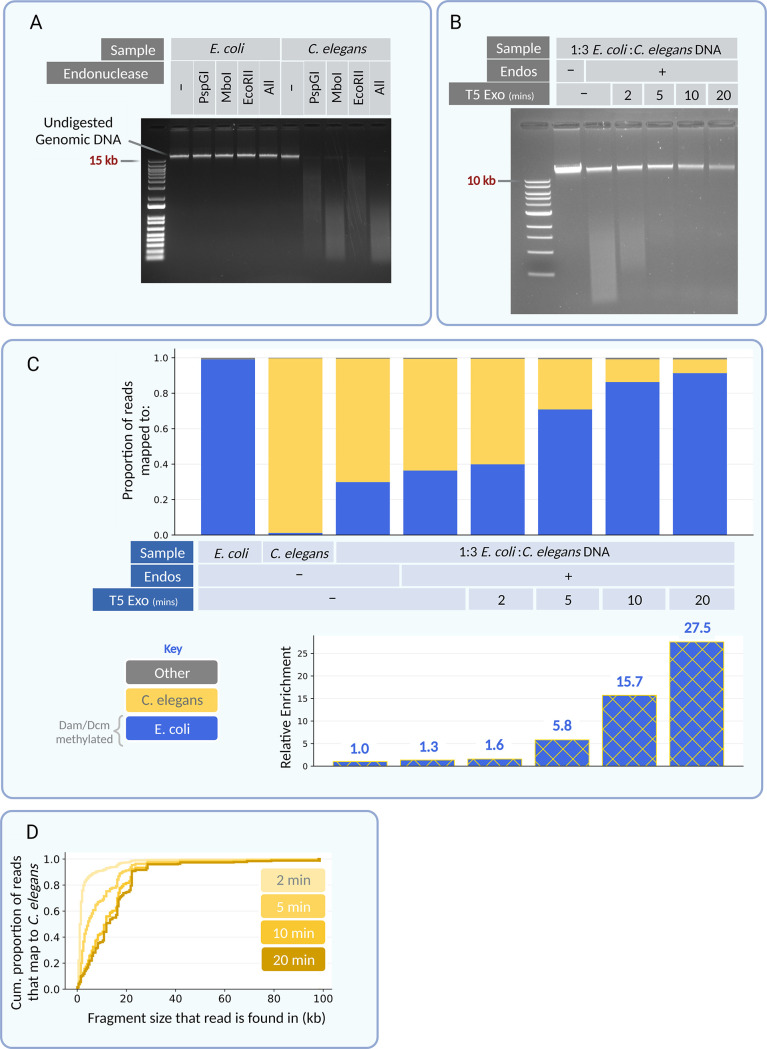

Genomic DNA from TOP10 E. coli and N2 C. elegans was prepared and treated with restriction endonucleases MboI, PspGI, and EcoRII. The DNA was found to be either resistant or susceptible to the action of these endonucleases, respectively (Fig. 2A). A 1:3 mixture (by mass) of genomic DNA from E. coli and C. elegans was prepared as a stand-in for a metagenomic sample. After treatment with the endonucleases, the sample was treated with the distributive T5 exonuclease for 2, 5, 10, or 20 min. When treated for 5 min, or beyond, shorter fragments were substantially depleted from the sample, while longer fragments were retained (Fig. 2B). The preferential retention of longer fragments was as expected given the timing of the reaction and rates of terminus-degrading exonuclease activity (29). When sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq, a progressive enrichment of the proportion of reads that mapped to E. coli was observed (Fig. 2C). Relative enrichment values were calculated as the ratio of the number of E. coli reads to C. elegans reads in a treated sample divided by the ratio in an untreated sample. With 20 min of exonuclease treatment, a 27.5-fold enrichment was observed (Fig. 2C). Longer T5 treatment did not result in greater enrichment of E. coli reads in this mixture (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To determine where the remaining proportion of C. elegans reads was originating from, each C. elegans read was assigned the theoretical length of the restriction fragment that it came from in an in silico digestion of the C. elegans genome. The cumulative distribution of these lengths was plotted for each T5 exonuclease time point (Fig. 2D), and many C. elegans reads, as expected, originated from regions greater than 10 kb.

FIG 2.

Methylation-sensitive endonucleases and T5 exonuclease enrich for E. coli DNA in an E. coli and C. elegans DNA mixture. (A) Gel showing the susceptibility of either E. coli DNA or C. elegans DNA to PspGI, MboI and EcoRII separately and all together. The genomic high-molecular-weight C. elegans band disappears when the endonuclease is applied. (B) Gel showing time points of T5 exonuclease treatment when applied to a 1:3 mixture of E. coli-to-C. elegans DNA treated with the corresponding endonucleases. Notice the disappearance of the low-molecular-weight smear (C. elegans DNA) with longer T5 exonuclease incubation. (C) Paired-end sequencing data from untreated and treated samples. In blue are the proportion of reads in that sample that map to the E. coli genome and in yellow are the proportion that map to the C. elegans genome. Any reads that do not map to either or have chimeric paired reads are colored gray. The C. elegans-only sample contains a certain amount of E. coli DNA likely due to the fact that the worms are fed E. coli. Shown below is the relative enrichment of E. coli DNA calculated as the ratio of the number of E. coli reads to C. elegans reads divided by the ratio in the untreated control. (D) For each T5 exonuclease time point, all C. elegans reads that remained were mapped to the length of the theoretical fragment size that they would be found in an in silico digestion of the C. elegans genome. A cumulative density plot of these fragments is shown to ascertain whether remaining C. elegans reads originate from long fragments or short fragments.

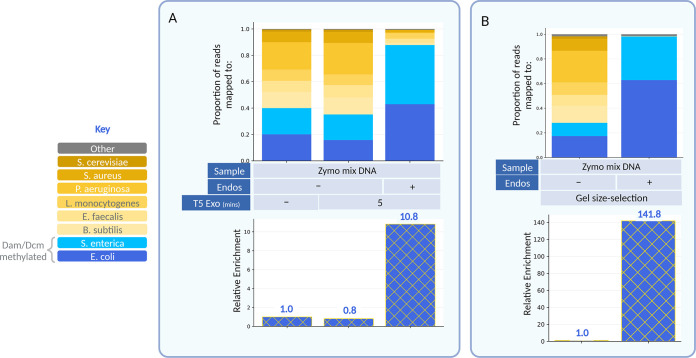

To assay a more complex but standardized sample, we performed this treatment on ZymoBIOMICS microbial community standard high-molecular-weight DNA (hereafter referred to as Zymo mix). This is a mixture of genomic DNA from one yeast and seven bacteria—of which two (E. coli and S. enterica) are Dam and Dcm methylated. Upon PspGI, MboI, and EcoRII endonuclease and T5 exonuclease treatment, an average of a 10.8-fold relative enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica DNA was observed (Fig. 3A). DNA from these two species composes 28% of the untreated Zymo mix according to the manufacturer (Zymo Research). However, we found that roughly 35% to 40% of reads from an untreated sample map to the E. coli and S. enterica genomes. This is likely due to our transposition-based sequencing library construction methods, which have a bias against GC-rich genomes (30). Additionally, it was observed that the enrichment worked just as well without EcoRII, which thus may be omitted (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, to maintain experimental consistency, EcoRII was used for all following experiments.

FIG 3.

Methylation-sensitive endonucleases and various size-selection approaches enrich for E. coli and S. enterica DNA in the Zymo mix. (A) Paired-end sequencing data from untreated, endonuclease-only treated and endonuclease- as well as T5 exonuclease-treated DNA. In blue are reads that map to genomes that are Dam and Dcm methylated. In yellow are reads that map to genomes that are not Dam and Dcm methylated. Mean proportions of two biological replicates were plotted. Relative enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica shown below were calculated from the mean proportions. The raw enrichment values for each replicate are as follows (1.0, 0.87, 9.72) and (1.0, 0.76, 12.74) from left to right. (B) Paired-end sequencing data from untreated and endonuclease-treated DNA size-selected through gel electrophoresis (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Mean proportions of two biological duplicates were plotted. Relative enrichments of E. coli and S. enterica shown below were calculated from mean proportions. The raw enrichment values for both duplicates were (1.0, 141.8) from left to right.

The addition of the T5 exonuclease acts to select for long fragments of DNA rapidly (5 to 20 min). This approach has the advantage of a low cost (~$0.03/sample) and can be performed in the same tube as the endonuclease treatment. We were curious how this might compare to the gold standard of electrophoretic size selection (agarose gel electrophoresis). Endonuclease untreated and treated Zymo mix DNA samples were resolved on a gel alongside each other (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Due to the size exclusion limit of a 1% gel, all fragments greater than ~15 kb (highest band of the ladder) comigrate as a single band (31). In the treated sample, a smear throughout the lane is observed; however, high-molecular-weight DNA originating from E. coli and S. enterica is found well above the 15-kb marker. Both the untreated and the treated high-molecular-weight bands were extracted from the gel and sequenced. Virtually all of the reads from the treated sample mapped to E. coli and S. enterica, providing a substantial relative enrichment of 141.8-fold (Fig. 3B). Electrophoretic size selection therefore proves to be an effective way of separating digested fragments from undigested fragments. However, it comes at the cost of time and money over a T5 exonuclease size selection.

Next, to test the dynamic range of exonuclease-based enrichment, we titrated down the input Zymo mix DNA amount from the initial value of 75 ng to 37.5 ng (1/2), 7.5 ng (1/10), and 0.75 ng (1/100). In all cases, we observed, on average, a greater than 20-fold relative enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica DNA (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Dynamic range of enrichment on various amounts and ratios of methylated DNA. (A) Paired-end sequencing data from either half, one-tenth, or one-hundredth the amount of Zymo mix DNA used in the standard protocol following otherwise the same enzyme concentrations. In blue are reads that map to genomes that are Dam and Dcm methylated. In yellow are reads that map to genomes that are not Dam and Dcm methylated. Relative enrichment is shown below. (B) Paired end sequencing data from Zymo mix DNA mixed with S. cerevisiae DNA in 1:1, 1:9, and 1:99 ratios with the total amount remaining 75 ng. Mean proportions of two biological duplicates were plotted for panel B. Relative enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica shown below were calculated from the mean proportions. The raw enrichment values for each replicate are (1.0, 62.9, 1.0, 45.0, 1.0, 28.6) and (1.0, 81.8, 1.0, 65.1, 1.0, 35.8) from left to right. In red are reads that map to the T4 phage. T4 phage DNA sequences represent a population of DNA fortuitously included with the yeast DNA material used in these assays. Notably, this DNA is enriched in parallel to the modified bacterial DNAs, a behavior that is both of interest and expected as a consequence of the known modification of T4 DNA. Thus, this population serves as a fortuitous positive control on the enrichment observed. Mean relative enrichment of T4 phage, E. coli, and S. enterica, together, is (1.0, 89.5, 1.0, 193.4, 1.0, 307.8) from left to right.

While the protocol continued to be effective for vanishingly small amounts of input DNA, we questioned how the enrichment varied when the ratio of Dam/Dcm methylated DNA to unmethylated DNA was altered. To test this, the Zymo mix DNA was mixed with Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic DNA in a 1:1, 1:9, and 1:99 ratio. We observed a robust enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica DNA at all ratios, with average enrichment ranging from 32.4- to 71.5-fold (Fig. 4B). To note is the surprising enrichment of a class of reads that did not seem to map to any of the genomes present in the Zymo mix or S. cerevisiae. This class of reads was reproduced upon replicate experiments. These reads were assembled into contigs using SPADES (32). The largest, most prevalent contig from these unmapped reads mapped to E. coli bacteriophage T4 using BLAST (shown now as red in Fig. 4B). Upon closer inspection, we realized some phage T4 DNA was unintentionally included with the S. cerevisiae DNA (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Enrichment of T4 DNA is expected because it contains hydroxymethyl cytosine, usually glucosylated, in place of cytosine (33–35). This allowed the T4 DNA to resist cleavage by PspGI, MboI, and EcoRII and was, therefore, selected for during T5 exonuclease treatment, serving as a fortuitous positive control (Fig. S4). This happenstance points toward the ability to use this tool as a way to discover genomes in metagenomic samples that are substantially modified or contain noncanonical bases (see Discussion).

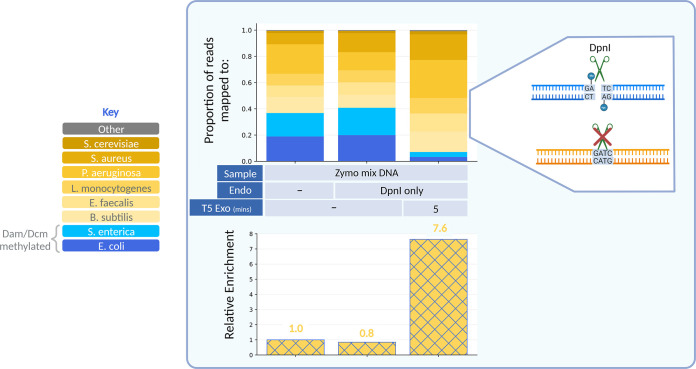

Finally, we asked whether a parallel protocol could be used for selective enrichment of unmodified DNA. DpnI is a restriction endonuclease that selectively cleaves at Dam sites that are methylated (unlike MboI, which cleaves at Dam sites that are unmethylated) (24). Accordingly, DpnI can be used to deplete E. coli and S. enterica DNA in a metagenomic sample. When DpnI was applied to the Zymo mix, a 7.6-fold relative enrichment of non-Dam methylated DNA was observed compared to that of the untreated control (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

DpnI and T5 exonuclease treatment enriches for DNA that is not Dam methylated. Paired-end sequencing data for Zymo mix DNA treated with DpnI, which only cuts at methylated Dam sites. Relative enrichments are shown below.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have described and implemented a novel approach, REMoDE, to enrich metagenomic samples for DNA from organisms of interest based on their specific patterns of DNA modification. While differential methylation has been used to obtain enriched sequence data sets in the past, the technical approaches have involved binding and release steps with high complexity in terms of reagents and protocols (11, 12). Applying restriction enzyme cleavage followed by exonuclease- or gel-based size selection, we obtained remarkable enrichments with only limited manipulation.

The approach provided herein specifically implements methods to selectively enrich DNA of organisms that contain Dam and Dcm systems. These methyltransferases are found in many members of the Gammaproteobacteria phyla including E. coli and S. enterica (19). Many pathogenic food outbreaks have been caused by species from the Gammaproteobacteria phyla (2). Various food and agricultural safety applications require high sequencing coverage of the outbreak strain to confidently obtain identifying SNPs for an outbreak source (optimal coverages may be as high as 50× [36]). Such coverage allows potential matching of the agricultural source with contaminated foods, providing an opportunity to accurately restrict further outbreak from the source, while avoiding interference with supply chains uninvolved in an outbreak.

Sequencing approaches lend tremendous specificity and sensitivity to detection and characterization of potential pathogens. However, challenges in utilization of a sequencing approach can arise in that metagenomic samples from both environmental and clinical sources generally contain irrelevant prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA that far exceeds that of the pertinent strain, and therefore, obtaining high-coverage WGS can prove difficult. This approach proves especially useful in metagenomic analyses such as these. In our experiments, we observe enrichment of E. coli and S. enterica DNA ranging from 11-fold to 142-fold with a broad dynamic range for input DNA amount. Additionally, the method has been developed such that the enrichment can be performed in a single tube and completed within 1.5 h.

Limitations.

There are several potential limitations of the REMoDE approach that users should be aware of. The implementation detailed in this study was performed on mock microbial communities, and there may be characteristics of some natural environmental samples that present additional challenges. While serving as a proof-of-principle that the approach robustly enriches enterobacteria in these samples, there is value in extending the study of this approach to natural samples, where the composition of the community of organisms and quality of DNA will influence the method’s effectiveness. That said, the mock metagenomic samples used in this study comprise DNA from a diverse set of organisms, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, phage, and animal.

Another limitation that we note is that an underlying requirement for the REMoDE method is the presence of high-molecular-weight input DNA for effective segregation of protected and unprotected fragments. The user should also be cognizant of the concentration of input DNA when using T5 exonuclease as a size-selection technique, as optimal exonuclease activity is dependent on both concentration of DNA and reaction time. In use cases where time, cost, and highly parallel processing is not of concern and substantial enrichment is, we suggest using gel electrophoresis as the technique of choice for size selection.

Although the patterns of modification are quite consistent in many species, we note that strains with different patterns of modification exist for some species and should be considered as potential confounders of any generalized approach. For example, B strain E. coli has lost its ability for Dcm methylation likely in the laboratory (37, 38). We encountered this as we tried to enrich for OP50 E. coli DNA and found, instead, that it was digested by PspGI and EcoRII, indicating that it was not Dcm methylated (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). We soon learned that OP50 is derived from B strain E. coli (39). Also, to be noted is that while Dam methyltransferases are indeed widespread (though not ubiquitous [40]) within Gammaproteobacteria, Dcm methyltransferases are apparently confined to genera closely related to Escherichia (38). The piecemeal distribution of Dcm methylation may serve as an advantage or disadvantage in REMoDE applications, depending on the organismal DNA to be enriched for. Since the Dam motif is shorter than the Dcm motif, it is found more frequently in any given genome. Hence, MboI contributes most to the segregation of methylated and unmethylated DNA at these sites compared to PspGI and EcoRII (Fig. 2B), suggesting that an MboI-only digestion would be sufficient to achieve strong enrichment. Indeed, it has also been found that Dam serves a core function for gene expression of virulence factors and that Dam inhibition attenuates virulence and pathogenicity in Dam bacteria in vivo (19, 22, 41). Pathogenic strains leading to outbreak, such as O157:H7, have been found to contain the genes for both Dam and Dcm (11, 42).

Extension of REMoDE for other applications.

Dam and Dcm systems extend to clinically relevant organisms beyond E. coli and S. enterica that would benefit from whole-genome sequencing for tracing purposes (19). For example, Vibrio cholerae (causes cholera), Yersinia pestis (causes plague), Legionella pneumophila (causes Legionnaires’ disease), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (causes pneumonia) are either known or predicted to methylate their Dam sites (19).

Some eukaryotic viruses are also known to harbor methyltransferases. For example, the Melbournevirus of the giant virus family Marseilleviridae is also Dam methylated (43).

It is also worth noting that the principle of enrichment using restriction enzymes and an exonuclease need not only extend to Dam and Dcm methylated DNA. As shown, unmodified DNA can be enriched using DpnI, and this paradigm can be applied more broadly by taking advantage of the vast catalogue of restriction enzymes. Indeed, among others, the following two methylated motifs that are broadly prevalent in clinically relevant bacteria: 5′-RAATTY-3′ and 5′-GANTC-3′ (methylated base underlined; R = A or G; Y = C or T; N = any) (19, 26). Unmethylated 5′-RAATTY-3′ is endonuclease-targeted by ApoI and, in subset, by EcoRI (5′-GAATTC-3′). Unmethylated 5′-GANTC-3′ is endonuclease-targeted by HinfI and, in subset, by TfiI (5′-GAWTC-3′; W = A or T). Under current assumptions, DNA from organisms that methylate these motifs should resist against the action of the listed endonucleases.

One such clinically relevant genus is Campylobacter (5′-RAATTY-3′), which is known to cause widespread foodborne illness across the globe and is estimated to cause more than 1.5 million infections per year in the United States (https://www.cdc.gov/campylobacter/faq.html) and close to 9 million in the European Union (https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/campylobacter). Campylobacter is often associated with the contamination and microbiome of poultry and wild birds (44). Theoretically, the use of ApoI and EcoRI should be able to enrich for these bacteria in metagenomic samples.

Another scenario where enrichment of pathogenic DNA for whole-genome sequencing purposes is particularly useful is in the case of nosocomial infections (infections that originate in the hospital). These are often spread through patient-to-patient contact or patient-to-surface-to-patient contact and need to be traced to origin (45). Such is the case, for example, for the opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii (5′-RAATTY-3′), which initially cropped up in medical military facilities and quickly spread to civilian medical facilities by way of infected soldiers being transported through them (46). This is in addition to bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae that may use the Dam/Dcm systems described above (47).

Mycoplasma bovis (5′-GANTC-3′) is known to infect cattle and has resulted in an estimated loss of $108 million in the United States annually (48). Similarly, Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella suis (5′-GANTC-3′) are known to cause brucellosis in livestock. This method may accordingly prove useful in disease tracking within livestock settings.

Oliveira and Fang detail the presence and distribution of different methylated motifs across clades of bacteria, which may prove useful for a user of this method to select appropriate restriction enzymes for their organism of interest (19). While our manuscript was in review, the same group released a preprint on a similar but slightly different endonuclease-based methylation-dependent enrichment approach called mEnrich-seq (49). In their preprint, they report comparable findings to those here in that there is distinct enrichment of organisms methylated at Dam sites with DpnII (an isoschizomer of MboI). Additionally, they validate the use of XapI (ApoI) to enrich for organisms methylated at 5′-RAATTY-3′.

REMoDE as a discovery tool.

Of potential interest in understanding the results of REMoDE assays are the characteristics of DNA fragments from nonmethylated organisms that remain after digestion and are represented in the sequencing data. Several features could result in the survival of these fragments, including a lack of restriction sites in long stretches of a genome, circular DNA (that does not contain the corresponding restriction sites and is insusceptible to exonuclease degradation), or protection of DNA ends on linear fragments due to specific chemical structures or linkage to a terminal protein. Likewise, novel DNA modifications (or damaged bases) could render some or all fragments from a given experimental source resistant to the initial endonuclease digestions.

Restriction-modification systems evolved such that a host cell’s restriction enzymes would be unable to digest host DNA due to the presence of protective modifications, which infecting phage DNA would not have. As such, type II restriction enzymes are very specific to their cognate restriction sites but are blocked by these modifications. This proves a useful method to distinguish modified DNA from unmodified DNA. In some cases, these enzymes are unable to cleave DNA with other modifications within the restriction site and not just with the modification associated with the corresponding restriction-modification system. Indeed, certain phages (T4, S2-L, etc.) modify all instances of a base (C in T4, A in S2-L) in their genome, and when purified DNA from these phages is treated with restriction enzymes, the DNA withstands the action of these enzymes (33, 34, 50). This is why a substantial enrichment of T4 DNA was observed in our experiments when there was an inadvertent inclusion of T4 DNA in our yeast DNA sample. REMoDE could, therefore, also be used to screen environmental samples for DNAs resistant to the action of a selection of endonucleases. Such sequences suggest the presence of noncanonical bases or modifications. This DNA could then be sequenced either by standard short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina) or by methods conducive to distinguishing modified residues, such as Oxford Nanopore or PacBio single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic DNA preparation.

(Typical methods for genomic DNA preparation should function well for REMoDE as long as caution is taken to limit extensive shearing of purified DNA. The methods of DNA purification employed in this study were relatively standard, and we have extensively detailed these below for reproducibility.)

E. coli.

Protocol is adapted from Green and Sambrook (51). A total of 1.5 mL of an overnight culture (2× TY medium) of TOP10 E. coli was centrifuged at 5,000 relative centrifugal force (RCF) at room temperature for 30 s and the supernatant removed by aspiration. Four hundred microliters of 10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA (TE) buffer at pH 8.0 was added to the tube, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended via gentle vortexing. Fifty microliters of 10% SDS and 50 μL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL in TE, pH 7.5) were added to the tube and left to incubate at 37°C for 1 h. The digested lysate was pipetted up and down three times with a p1000 pipette to reduce viscosity. Five hundred microliters of a 1:1 mixture of phenol/chloroform (phenol equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) was added to the tube and pipetted up and down multiple times to mix. The mixture was then transferred to a 2-mL phase lock light tube (5 PRIME 2302800) and centrifuged at 16,000 RCF at room temperature for 5 min. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new phase lock tube, and the 1:1 phenol/chloroform extraction was repeated. The aqueous phase was then extracted twice with 500 μL chloroform. The suspension was transferred to a fresh microcentrifuge tube, and 25 μL of 5 M NaCl followed by 1 mL of ice-cold 95% ethanol was added. The mixture was pipetted up and down multiple times and then centrifuged at 21,000 RCF at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully removed with a pipette and left to dry for 10 min. The damp-dry pellet was dissolved in 100 μL of TE. A total of 2.5 μL of RNaseA (10 mg/mL; Thermo Scientific; EN0531) was added to the solution, mixed, and left to incubate for 30 min at 37°C. Forty microliters of 5 M ammonium acetate and 250 μL of isopropanol were added to the mixture, mixed with a pipette, and left to incubate at room temperature for 10 min with the cap closed. The tube was centrifuged at 21,000 RCF at room temperature for 10 min. The pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol, and then the ethanol was aspirated carefully with a pipette. The tube was left to dry for 10 min. The pellet was then dissolved in 100 μL TE (pH 8.0) and left to incubate overnight at 37°C for complete dissolution. The concentration was determined using Qubit BR double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) reagents and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer.

C. elegans.

Worms from three 60-mm by 15-mm starved plates of N2-strain (PD1074) C. elegans were collected by washing them off the plate with 1.5 mL of 50 mM NaCl and into a 1.5-mL tube. The tube was centrifuged for 40 s at 400 RCF at room temperature. Approximately 1,200 μL of the supernatant was aspirated out, leaving roughly 300 μL of worms and solution. In a fresh 1.5-mL tube, 1.2 mL of 50 mM NaCl containing 5% sucrose was added. The remaining 300 μL of the worms and solution was mixed and layered over the sucrose cushion. The tube was centrifuged for 40 s at 400 RCF. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with 1.5 mL of 50 mM NaCl. The tube was centrifuged again for 40 s and the supernatant removed. A total of 450 μL of worm lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS) was added to the tube along with 20 μL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL). The tube was gently vortexed. The tube was left to incubate at 62°C for 45 min and vortexed four to five times throughout the incubation. Five hundred microliters of phenol was added to the tube, mixed thoroughly by pipetting up and down, and transferred to a phase lock light tube. The tube was centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 RCF. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new phase lock tube and extracted with 500 μL of 1:1 phenol/chloroform. Finally, the aqueous phase, again, was extracted with 500 μL of chloroform and transferred to a fresh 1.5-mL tube. Eighty microliters of 5 M ammonium acetate was added to the solution. One milliliter of ethanol was added to the tube and mixed thoroughly by pipetting. The tube was then centrifuged for 5 min at 21,000 RCF at room temperature, and the pellet was washed once with 0.5 mL of ethanol and centrifuged again. The ethanol was aspirated out, and the pellet was left to dry for 10 min at room temperature after which 25 μL of TE (pH 8.0) was used to resuspend it. The concentration was determined using Qubit BR dsDNA reagents and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer. Note that RNase was not used in this preparation, and thus downstream experiments with C. elegans contain C. elegans RNA; however, DNA was RNaseA treated before loading onto gel in Fig. 2A.

S. cerevisiae.

Four milliliters of an overnight S288C yeast culture (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD] medium) was pelleted at 16,000 RCF for 1 min and resuspended in 250 μL of breaking buffer (2% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 1% [wt/vol] SDS, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris base pH 8, 1 mM EDTA). Approximately, to the volume of 200 μL of 0.5-mm glass beads was added to the mixture as well as 500 μL of 1:1 phenol/chloroform. The tube was vortexed at max speed at 4°C for 10 min. It was then centrifuged at 16,000 RCF at 4°C for 10 min. Four hundred microliters of the aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh 1.5-mL tube. One microliter of RNase A (10 mg/mL) was added to the mixture, and it was left to incubate at 37°C for 10 min. A total of 750 μL of 1:1 phenol/chloroform was added to the tube and mixed well with a pipette. The solution was transferred to a 2-mL phase lock light tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 RCF at room temperature. The aqueous phase was then transferred to a fresh 1.5-mL tube, and 65 μL of 3 M sodium acetate was added to the tube. One milliliter of ice-cold ethanol was added to the tube, mixed, and left to incubate for 10 min at −20°C. The tube was centrifuged for 10 min at 21,000 RCF. The supernatant was carefully aspirated out, and the pellet was washed with 1 mL of ice-cold 70% ethanol. The tube was spun again for 10 min at 21,000 RCF at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully aspirated out, and the pellet was left to dry for 10 min. It was then resuspended in 20 μL of TE. The concentration was determined using Qubit BR dsDNA reagents and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer.

ZymoBIOMICS MCS-HMW DNA.

ZymoBIOMICS MCS-HMW DNA (Zymo D6322; “Zymo mix”) was obtained from Zymo Research. The concentration was determined using Qubit BR dsDNA reagents and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer and found to be slightly lower than the manufacturer specifications (78 ng/μL as opposed to 100 ng/μL). For all of the following experiments, the Qubit-measured concentration was used instead of the manufacturer provided one. Zymo Research reports that the standard contains DNA that is >50 kb in size.

Endonuclease and exonuclease treatment.

Note that for initial experiments, a substantial amount of DNA was used (750 ng) as input, and it was later found that the input could be decreased manifold. In the Zymo mix experiments, 75 ng of input DNA was used.

Both PspGI and EcoRII target Dcm sites and were used in these experiments. The redundancy is due to both enzymes requiring conditions that were inconvenient: PspGI has a high optimal temperature, which is 75°C that could be detrimental to the nucleic acids in the sample, and EcoRII requires the presence of two Dcm sites in close proximity for cleavage. Hence, both enzymes were used at more convenient but suboptimal conditions as follows: a 50°C incubation for PspGI and an additional 30-min incubation (1 h total) of EcoRII. However, as shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material, EcoRII may be omitted for seemingly no loss in fold enrichment with the Zymo mix.

The enzyme concentrations, conditions, and incubation times described here may be modified to user specifications. Optimal T5 exonuclease concentration and incubation time may rely, among other factors, on the amount of DNA, the number of available DNA fragment termini, and the median length of DNA fragments in any given reaction. Ideally, time points for T5 exonuclease incubation should be taken for every uncharacterized sample, as an extended incubation may result in overdigestion of DNA and limited enrichment of the genome of interest.

E. coli and C. elegans mixture.

To set up 37.5-μL reaction mixtures, 1:3 mixtures of E. coli and C. elegans DNA were made by mixing 187.5 ng of E. coli genomic DNA with 562.5 ng of C. elegans genomic DNA in 8-strip PCR tubes. A volume of ultrapure water needed to make the reaction up to 37.5 μL after the addition of rCutsmart (NEB B6004S) and PspGI (NEB R0611) was added to each reaction mixture followed by 3.75 μL of 10× rCutsmart buffer and 0.6 μL (6 U) of PspGI. The tubes were mixed via gentle vortexing after every step. Each mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 min after which 0.6 μL (3 U) of MboI (NEB R0147) was added to each reaction mixture. Each mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min after which 0.94 μL of 2 M NaCl was added to each reaction mixture (to bring the NaCl concentration to roughly 50 mM, which is optimal for EcoRII [Thermo Scientific ER1921]). Then, 0.6 μL (6 U) of EcoRII was added to each reaction mixture. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The tubes were put on ice and 0.4 μL (4 U) of T5 exonuclease (NEB M0663) was added to each reaction mixture and incubated for 2, 5, 10, or 20 min at 37°C and immediately quenched with 8 μL 6× NEB purple loading dye (NEB B7024S) supplemented with 6 mM EDTA (to make the total EDTA concentration in the stock tube 66 mM). Twelve microliters of the mixture was resolved on a 1% agarose gel run at 140 V for 40 min.

Seventy-four microliters of ultrapure water was added to the remaining sample (to make up to 100 μL total volume), and each reaction mixture was then purified using the Zymo genomic clean and concentrate kit (Zymo D4011). The DNA was eluted with 10 mM Tris buffer heated to 63°C and incubated for between 2 and 5 min. The concentration was determined using Qubit HS dsDNA reagents and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer. For control reactions, enzymes were replaced with an equal volume of ultrapure water at the appropriate point in the protocol.

ZymoBIOMICS MCS-HMW (Zymo mix).

For the experiment in Fig. 3A, 75 ng of Zymo mix DNA was used. A volume of ultrapure water needed to make the reaction mixture up to 37.5 μL after the addition of rCutsmart and PspGI was added to each reaction mixture followed by 3.75 μL of 10× rCutsmart buffer and 0.6 μL (6 U) of PspGI. The tubes were mixed via gentle vortexing after every step. Each mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 min after which 0.6 μL (3 U) of MboI was added to each reaction mixture. Each mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min after which 0.94 μL of 2 M NaCl added to each reaction mixture (to bring the NaCl concentration to roughly 50 mM, which is optimal for EcoRII). Then, 0.6 μL (6 U) of EcoRII was added to each reaction mixture. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Note that as shown in Fig. S2, this step may be omitted and after incubation with MboI, the reaction may proceed directly to T5 exonuclease digestion. The tubes were put on ice and 0.4 μL (0.4 U) of T5 exonuclease diluted 1:10 in 1× NEBuffer 4 was added to each reaction mixture and incubated for 5 min at 37°C and immediately quenched with 8 μL 66 mM EDTA. The tubes were vortexed. Fifty-two microliters of TE was added to each reaction mixture to make up to 100 μL total volume and purified using the Zymo genomic clean and concentrate kit. The DNA was eluted with 15 μL of 10 mM Tris buffer heated to 50°C and incubated for 2 to 5 min. This experiment was done in biological duplicate.

For the experiment in Fig. 3B, the same protocol was followed as in Fig. 3A except after the EcoRII incubation, 8 μL of NEB purple loading dye was added and the samples were loaded into a 1% agarose gel and run for 45 min at 120 V. The high-molecular-weight bands were excised with a razor and dissolved in 3 volumes of Zymo agarose dissolving buffer (Zymo D4001) at 50°C. They were then processed through the Zymo genomic clean and concentrate kit as in Fig. 3A excluding the step of the addition of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) DNA binding buffer. This experiment was done in biological duplicate, and one of the duplicates was prepared from a previous experiment.

For the experiment in Fig. 4A, the same protocol was followed as in the experiment in Fig. 3A save for using either 37.5, 7.5, and 0.75 ng of input Zymo mix DNA.

For the experiment in Fig. 4B, different ratios of Zymo mix DNA and S. cerevisiae DNA were mixed together 1:1 (37.5 ng:37.5 ng), 1:9 (7.5 ng:67.5 ng), and 1:99 (0.75 ng:74.25 ng), and the same protocol was followed as in Fig. 3A save for the T5 exonuclease incubation being 20 min instead of 5. This experiment was done in biological duplicate.

For the experiment in Fig. 5, the same protocol was followed as in Fig. 3A, save for a 1-h incubation with 0.3 μL (3 U) of DpnI (NEB R0176) at 37°C instead of using PspGI, MboI, or EcoRII.

Figure 3A (1 replicate), Fig. 5, and Fig. S2 plot the same untreated Zymo mix control data since these were performed in the same experiment. Additionally, Fig. 3A (1 replicate) and Fig. S2 plot the same PspGI-, MboI-, EcoRII-, and T5 exonuclease-treated data since these were performed in the same experiment.

Library preparation and MiSeq sequencing.

Nextera XT (Illumina FC-131-1024) library preparation was used to build sequencing libraries for all experiments. One-third of the recommended volumes of the manufacturer protocol were used, i.e., 3.33 μL of tagmentation buffer, 1.67 μL of 0.2 ng/μL DNA, 1.67 μL of Tn5 mix, 1.67 μL of the neutralizing buffer, 1.67 μL of each index followed by 5 μL of the polymerase mix. The transposition incubation was done at 37°C for 5 min. Amplification was performed as in the Nextera XT protocol with 12 cycles of amplification. The amplified libraries were resolved on a gel, and DNA of the range of 300 to 600 bp was excised for gel recovery using the Zymo gel extraction kit (Zymo D4007). Concentrations of DNA were determined with Qubit HS dsDNA reagents and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer. The libraries were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer using a MiSeq reagent kit v3 (MS-102-3001; 78 cycle, paired-end).

Data analysis.

Reads were demultiplexed on the Illumina MiSeq using the MiSeq reporter. The resulting reads were mapped to their corresponding genomes via Bowtie 2 version 2.4.5 (52) using default settings. The reference file (FASTA format) for each experiment contained the genomes of each organism whose DNA was used in that experiment. The reference file was organized such that each chromosome or plasmid from every genome was given a header name unique to that species. Reads that mapped to each species were counted by parsing through the SAM file output by Bowtie 2 and first binning each aligned read to its corresponding species in a Python 3 list and then counting the elements of that list. The proportion of reads mapped to a particular species was obtained by dividing against the total number of aligned reads. The data were plotted using matplotlib in Python 3 on Jupyter Notebook. Relative enrichment was calculated as follows:

Genome sequences.

For E. coli and C. elegans experiments, genome assemblies GCA_000005845.2 (GenBank) and UNSB01000000 (European Nucleotide Archive) were used, respectively. These genomes were combined into a single FASTA file used as a reference for Bowtie 2, and the alignments were output as SAM files.

For Zymo mix experiments, genome assemblies were obtained from the protocol of this reagent (https://s3.amazonaws.com/zymo-files/BioPool/D6322.refseq.zip). The genomes were combined into a single file. Since the assembly that was included for S. cerevisiae was heavily discontiguous and since the S288C strain of S. cerevisiae was used in the experiment for Fig. 4B, the provided S. cerevisiae was instead replaced with the latest assembly available on the Saccharomyces Genome Database (S288C_reference_sequence_R64-3-1_20210421). Also added to this file was the genome for T4 phage (GenBank accession number OL964735.1), as this sequence appears in some sequencing data sets due to use in other ongoing experiments. Finally, for some samples, reads that did not map to any of the listed genomes were assembled using SPADES version 3.13.0 with default parameters. When these contigs were input into BLASTN, it revealed the presence of the aforementioned T4 phage DNA (subsequently added to reference file) but also plasmids of S. cerevisiae and S. enterica that were not included in the reference genomes (S. cerevisiae [CP059538.1, J01347.1]; S. enterica [GenBank accession number CP012345.2]). These plasmids were also added to the reference genome file.

In silico digest of C. elegans genome.

The C. elegans genome was digested in silico based on sites where a Dam or Dcm cleavage site is expected. Each read mapped by Bowtie 2 was located to the theoretical fragment by genomic coordinates. The theoretical length of the containing fragment(s) for each read was assessed by measuring the number of bases between upstream and downstream cut sites.

Data availability.

All sequencing data sets used in this study have been deposited on to the NCBI SRA (PRJNA903933). SRA accession numbers for each sample can be found in the supplementary excel file.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the lab of Gavin Sherlock (Stanford University) and A. Pyke for providing the S288C strain of S. cerevisiae. We also thank K. Artiles, M. McCoy, O. Ilbay, L. Wahba, M. Shoura, D. Jeong, E. Greenwald, D. Galls, A. Straight, P. Sidhwani, K. Sundararajan, C. Limouse, K. Fryer, R. Brown, O. Smith, R. Ladurner, and M. Gebala for discussion on the project.

Support for this work was provided by NIH Grant R35GM130366. S.U.E. was supported by NIH grant T32HG000044. J.L.C. was supported by the intramural research program of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Figures were created with BioRender.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Andrew Z. Fire, Email: afire@stanford.edu.

Edward G. Dudley, The Pennsylvania State University

REFERENCES

- 1.Buytaers FE, Saltykova A, Denayer S, Verhaegen B, Vanneste K, Roosens NHC, Piérard D, Marchal K, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2020. A practical method to implement strain-level metagenomics-based foodborne outbreak investigation and source tracking in routine. Microorganisms 8:1191. 10.3390/microorganisms8081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng X, den Bakker HC, Hendriksen RS. 2016. Genomic epidemiology: whole-genome-sequencing–powered surveillance and outbreak investigation of foodborne bacterial pathogens. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 7:353–374. 10.1146/annurev-food-041715-033259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buytaers FE, Saltykova A, Mattheus W, Verhaegen B, Roosens NHC, Vanneste K, Laisnez V, Hammami N, Pochet B, Cantaert V, Marchal K, Denayer S, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2021. Application of a strain-level shotgun metagenomics approach on food samples: resolution of the source of a Salmonella food-borne outbreak. Microb Genom 7:e000547. 10.1099/mgen.0.000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltykova A, Buytaers FE, Denayer S, Verhaegen B, Piérard D, Roosens NHC, Marchal K, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2020. Strain-level metagenomic data analysis of enriched in vitro and in silico spiked food samples: paving the way towards a culture-free foodborne outbreak investigation using STEC as a case study. Int J Mol Sci 21:5688. 10.3390/ijms21165688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buytaers FE, Saltykova A, Denayer S, Verhaegen B, Vanneste K, Roosens NHC, Piérard D, Marchal K, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2021. Towards real-time and affordable strain-level metagenomics-based foodborne outbreak investigations using oxford nanopore sequencing technologies. Front Microbiol 12:738284. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.738284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forghani F, Li S, Zhang S, Mann DA, Deng X, den Bakker HC, Diez-Gonzalez F. 2020. Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli in wheat flour: detection and serotyping by a quasimetagenomic approach assisted by magnetic capture, multiple-displacement amplification, and real-time sequencing. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e00097-20. 10.1128/AEM.00097-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fratamico PM, DebRoy C, Needleman DS. 2016. Editorial: emerging approaches for typing, detection, characterization, and traceback of Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 7:2089. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrangou R, Dudley EG. 2016. CRISPR-based typing and next-generation tracking technologies. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 7:395–411. 10.1146/annurev-food-022814-015729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng X, Shariat N, Driebe EM, Roe CC, Tolar B, Trees E, Keim P, Zhang W, Dudley EG, Fields PI, Engelthaler DM. 2015. Comparative analysis of subtyping methods against a whole-genome-sequencing standard for Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. J Clin Microbiol 53:212–218. 10.1128/JCM.02332-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franz E, Gras LM, Dallman T. 2016. Significance of whole genome sequencing for surveillance, source attribution and microbial risk assessment of foodborne pathogens. Current Opinion in Food Science 8:74–79. 10.1016/j.cofs.2016.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes HE, Liu G, Weston CQ, King P, Pham LK, Waltz S, Helzer KT, Day L, Sphar D, Yamamoto RT, Forsyth RA. 2014. Selective microbial genomic DNA isolation using restriction endonucleases. PLoS One 9:e109061. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu G, Weston CQ, Pham LK, Waltz S, Barnes H, King P, Sphar D, Yamamoto RT, Forsyth RA. 2016. Epigenetic segregation of microbial genomes from complex samples using restriction endonucleases HpaII and McrB. PLoS One 11:e0146064. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiou KL, Bergey CM. 2018. Methylation-based enrichment facilitates low-cost, noninvasive genomic scale sequencing of populations from feces. Sci Rep 8:1975. 10.1038/s41598-018-20427-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marotz CA, Sanders JG, Zuniga C, Zaramela LS, Knight R, Zengler K. 2018. Improving saliva shotgun metagenomics by chemical host DNA depletion. Microbiome 6:42. 10.1186/s40168-018-0426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heravi FS, Zakrzewski M, Vickery K, Hu H. 2020. Host DNA depletion efficiency of microbiome DNA enrichment methods in infected tissue samples. J Microbiol Methods 170:105856. 10.1016/j.mimet.2020.105856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feehery GR, Yigit E, Oyola SO, Langhorst BW, Schmidt VT, Stewart FJ, Dimalanta ET, Amaral-Zettler LA, Davis T, Quail MA, Pradhan S. 2013. A method for selectively enriching microbial DNA from contaminating vertebrate host DNA. PLoS One 8:e76096. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi Y, Shoura M, Fire A, Morishita S. 2022. Context-dependent DNA polymerization effects can masquerade as DNA modification signals. BMC Genomics 23:249. 10.1186/s12864-022-08471-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brown ZK, Boulias K, Wang J, Wang SY, O'Brown NM, Hao Z, Shibuya H, Fady P-E, Shi Y, He C, Megason SG, Liu T, Greer EL. 2019. Sources of artifact in measurements of 6mA and 4mC abundance in eukaryotic genomic DNA. BMC Genomics 20:445. 10.1186/s12864-019-5754-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira PH, Fang G. 2021. Conserved DNA methyltransferases: a window into fundamental mechanisms of epigenetic regulation in bacteria. Trends Microbiol 29:28–40. 10.1016/j.tim.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wion D, Casadesús J. 2006. N6-methyl-adenine: an epigenetic signal for DNA–protein interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:183–192. 10.1038/nrmicro1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouammine A, Collier J. 2018. The impact of DNA methylation in Alphaproteobacteria. Mol Microbiol 110:1–10. 10.1111/mmi.14079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Løbner-Olesen A, Skovgaard O, Marinus MG. 2005. Dam methylation: coordinating cellular processes. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:154–160. 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marinus MG, Morris NR. 1973. Isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid methylase mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 114:1143–1150. 10.1128/jb.114.3.1143-1150.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geier GE, Modrich P. 1979. Recognition sequence of the dam methylase of Escherichia coli K12 and mode of cleavage of Dpn I endonuclease. J Biol Chem 254:1408–1413. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)34217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinus MG, Løbner-Olesen A. 2014. DNA methylation. EcoSal Plus 6. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0003-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornish-Bowden A. 1985. Nomenclature for incompletely specified bases in nucleic acid sequences: recommendations 1984. Nucleic Acids Res 13:3021–3030. 10.1093/nar/13.9.3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May MS, Hattman S. 1975. Analysis of bacteriophage deoxyribonucleic acid sequences methylated by host- and R-factor-controlled enzymes. J Bacteriol 123:768–770. 10.1128/jb.123.2.768-770.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer BR, Marinus MG. 1994. The dam and dcm strains of Escherichia coli — a review. Gene 143:1–12. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joannes M, Saucier JM, Jacquemin-Sablon A. 1985. DNA filter retention assay for exonuclease activities. Application to the analysis of processivity of phage T5 induced 5′-exonuclease. Biochemistry 24:8043–8049. 10.1021/bi00348a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato MP, Ogura Y, Nakamura K, Nishida R, Gotoh Y, Hayashi M, Hisatsune J, Sugai M, Takehiko I, Hayashi T. 2019. Comparison of the sequencing bias of currently available library preparation kits for Illumina sequencing of bacterial genomes and metagenomes. DNA Res 26:391–398. 10.1093/dnares/dsz017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz DC, Cantor CR. 1984. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell 37:67–75. 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Josse J, Kornberg A. 1962. Glucosylation of deoxyribonucleic acid: III. α- AND β-glucosyl transferases from T4-infected Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 237:1968–1976. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)73968-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pratt EA, Kuno S, Lehman IR. 1963. Glucosylation of the deoxyribonucleic acid in hybrids of coliphages T2 and T4. Biochim Biophysica Acta 68:108–111. 10.1016/0926-6550(63)90413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flodman K, Corrêa IR, Dai N, Weigele P, Xu S. 2020. In vitro type II restriction of bacteriophage DNA with modified pyrimidines. Front Microbiol 11:604618. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.604618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pightling AW, Petronella N, Pagotto F. 2014. Choice of reference sequence and assembler for alignment of Listeria monocytogenes short-read sequence data greatly influences rates of error in SNP analyses. PLoS One 9:e104579. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Militello KT, Simon RD, Qureshi M, Maines R, Van Horne ML, Hennick SM, Jayakar SK, Pounder S. 2012. Conservation of Dcm-mediated cytosine DNA methylation in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 328:78–85. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez-Eichelmann MC, Levy-Mustri A, Ramirez-Santos J. 1991. Presence of 5-methylcytosine in CC(A/T)GG sequences (Dcm methylation) in DNAs from different bacteria. J Bacteriol 173:7692–7694. 10.1128/jb.173.23.7692-7694.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.2009. The genome sequence of E. coli OP50. The Worm Breeder’s Gazette. http://wbg.wormbook.org/2009/12/01/the-genome-sequence-of-e-coli-op50/. Retrieved 6 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 40.On YY, Welch M. 2021. The methylation-independent mismatch repair machinery in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 167:e001120. 10.1099/mic.0.001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang G, Munera D, Friedman DI, Mandlik A, Chao MC, Banerjee O, Feng Z, Losic B, Mahajan MC, Jabado OJ, Deikus G, Clark TA, Luong K, Murray IA, Davis BM, Keren-Paz A, Chess A, Roberts RJ, Korlach J, Turner SW, Kumar V, Waldor MK, Schadt EE. 2012. Genome-wide mapping of methylated adenine residues in pathogenic Escherichia coli using single-molecule real-time sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 30:1232–1239. 10.1038/nbt.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanjar F, Hazen TH, Shah SM, Koenig SSK, Agrawal S, Daugherty S, Sadzewicz L, Tallon LJ, Mammel MK, Feng P, Soderlund R, Tarr PI, DebRoy C, Dudley EG, Cebula TA, Ravel J, Fraser CM, Rasko DA, Eppinger M. 2014. Genome sequence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 2886–75, associated with the first reported case of human infection in the United States. Genome Announc 2:e01120-13. 10.1128/genomeA.01120-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeudy S, Rigou S, Alempic J-M, Claverie J-M, Abergel C, Legendre M. 2020. The DNA methylation landscape of giant viruses. Nat Commun 11:2657. 10.1038/s41467-020-16414-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y, Feye KM, Shi Z, Pavlidis HO, Kogut M, J Ashworth A, Ricke SC. 2019. A historical review on antibiotic resistance of foodborne Campylobacter. Front Microbiol 10:1509. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kollef MH, Torres A, Shorr AF, Martin-Loeches I, Micek ST. 2021. Nosocomial infection. Crit Care Med 49:169–187. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howard A, O'Donoghue M, Feeney A, Sleator RD. 2012. Acinetobacter baumannii. Virulence 3:243–250. 10.4161/viru.19700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Podschun R, Ullmann U. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev 11:589–603. 10.1128/CMR.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicholas RAJ, Ayling RD. 2003. Mycoplasma bovis: disease, diagnosis, and control. Res Vet Sci 74:105–112. 10.1016/s0034-5288(02)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao L, Kong Y, Fan Y, Ni M, Tourancheau A, Ksiezarek M, Mead EA, Koo T, Gitman M, Zhang X-S, Fang G. 2022. mEnrich-seq: methylation-guided enrichment sequencing of bacterial taxa of interest from microbiome. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.11.07.515285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Szekeres M, Matveyev AV. 1987. Cleavage and sequence recognition of 2,6-diaminopurine-containing DNA by site-specific endonucleases. FEBS Lett 222:89–94. 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green MR, Sambrook J. 2017. Isolating DNA from Gram-negative bacteria. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2017:pdb.prot093369. 10.1101/pdb.prot093369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aem.01670-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.5 MB (1.5MB, pdf)

Supplemental material. Download aem.01670-22-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (11.2KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing data sets used in this study have been deposited on to the NCBI SRA (PRJNA903933). SRA accession numbers for each sample can be found in the supplementary excel file.