ABSTRACT

Unravelling the structure-function variation of phycospheric microorganisms and its ecological correlation with harmful macroalgal blooms (HMBs) is a challenging research topic that remains unclear in the natural dynamic process of HMBs. During the world’s largest green tide bloom, causative macroalgae Ulva prolifera experienced dramatic changes in growth state and environmental conditions, providing ideal scenarios for this investment. Here, we assess the phycospheric physicochemical characteristics, the algal host’s biology, the phycospheric bacterial constitutive patterns, and the functional potential during the U. prolifera green tide. Our results indicated that (i) variation in the phycosphere nutrient structure was closely related to the growth state of U. prolifera; (ii) stochastic processes govern phycospheric bacterial assembly, and the contribution of deterministic processes to assembly varied among phycospheric seawater bacteria and epiphytic bacteria; (iii) phycospheric seawater bacteria and epiphytic bacteria exhibited significant heterogeneity variation patterns in community composition, structure, and metabolic potential; and (iv) phycospheric bacteria with carbon or nitrogen metabolic functions potentially influenced the nutrient utilization of U. prolifera. Furthermore, the keystone genera play a decisive role in the structure-function covariation of phycospheric bacterial communities. Our study reveals complex interactions and linkages among environment-algae-bacterial communities which existed in the macroalgal phycosphere and highlights the fact that phycospheric microorganisms are closely related to the fate of the HMBs represented by the green tide.

IMPORTANCE Harmful macroalgal blooms represented by green tides have become a worldwide marine ecological problem. Unraveling the structure-function variation of phycospheric microorganisms and their ecological correlation with HMBs is challenging. This issue is still unclear in the natural dynamics of HMBs. Here, we revealed the complex interactions and linkages among environment-algae-bacterial communities in the phycosphere of the green macroalgae Ulva prolifera, which causes the world’s largest green tides. Our study provides new ideas to increase our understanding of the variation patterns of macroalgal phycospheric bacterial communities and the formation mechanisms and ecological effects of green tides and highlights the importance of phycospheric microorganisms as a robust tool to help understand the fate of HMBs.

KEYWORDS: green tide, phycosphere, Ulva prolifera, bacterial community, harmful macroalgal bloom

INTRODUCTION

Algae and microorganisms, important regulators of the structure and function of marine ecosystems, have intricate interactions (1). The most fundamental relationship between algae and bacteria is the supply-demand relationship of resources (2), in which bacteria transform nutrients to promote algal growth and compete with algae for essential nutrients (3). Algae release organic matter which is used by heterotrophic bacteria, and the chemical nature and concentration of these released compounds vary depending on the species and physiological state of the algae (2, 4). Studies on algal-microbial interactions have typically been conducted at large spatiotemporal scales (1, 5), but emerging evidence indicates that the algae-bacteria relationship is often governed by microscale interactions played out within the region immediately surrounding algal cells (3). This microenvironment, known as the phycosphere, has rich microbial communities, a diverse material composition, and variable ecological functions (6, 7). It is also a common microhabitat in marine ecosystems. Microorganisms in the phycosphere exist in various forms. Microorganisms in a free and particulate form are suspended in seawater, while those in a flocculated form can build a zoogloea consortium to surround phytoplankton cells or build biofilms to attach to the macroalgal surface (1, 8). Phycospheric microorganisms have active metabolic capacity and material transformation ability, which, together with abiotic elements and algal hosts, constitute the three basic components of the structure and function of phycospheric microecosystems (9, 10). Importantly, interactions taking place within the phycosphere occur at the scale of individual microorganisms and exert an ecosystem-scale influence on fundamental processes; these include nutrient provision and regeneration, primary production, and biogeochemical cycling (3).

The phycosphere is the key ecological interface for algae-microorganism interactions (3). Algae fundamentally change the chemical environment of the phycosphere (11). Bacteria exhibit chemotaxis to a range of algal exudates, which may likewise enable them to colonize the phycosphere (4, 12, 13). Some microorganisms associated with the phycosphere can produce biologically available sources of nitrogen, phosphorus, hormones, and volatile compounds to promote algal growth (14, 15). In summary, the phycosphere can be considered a marketplace where cross-kingdom communications are mediated by the release and uptake of organic compounds (16), and gradients within this sphere guide the chemoattraction of bacteria in microscale interactions (4). Although there is no clear definition of the extent of the phycosphere, it can be estimated by gradients of organic compounds (11). Studies have revealed that it can extend from several hundreds of micrometers to a few millimeters around the algal cell (13, 17). However, the size of the phycosphere is variable, depending largely on the size of algal cells and surrounding microbes, and can be changed by algal growth, exudation rate, concentration, and the diffusivity of exuded compounds (3, 11). Recent research has revealed that the phycosphere contains many new and undiscovered microbial lineages and genetic resources (18, 19). The formation of phycosphere microbial communities is closely related to algal bloom events and phycospheric microorganisms can influence the fate and development of an algal bloom cooperatively or competitively, providing a new theory to analyze the mechanisms of algal bloom occurrence (6, 7, 20).

Green tide is an abnormal ecological phenomenon caused by the excessive growth and accumulation of macroalgae of the phylum Chlorophyta (21). Since 2007, the world’s largest green tides, caused by Ulva prolifera, have occurred every summer in the South Yellow Sea in China. These blooms seriously harm offshore marine ecosystems and cause huge economic losses, which has attracted extensive research (22, 23). The U. prolifera green tide is a transregional disaster. It usually originates in the coastal areas of the southern Yellow Sea from mid-April to early May, initially in small patches of floating algae. Subsequently, free-floating algae move northward, driven by ocean currents and the southeast monsoon, gradually forming floating algal mats tens to hundreds of meters in diameter and up to 50 cm thick (24, 25). By mid-June, floating U. prolifera grows to a huge size, covering a large area in the coastal sea of the Shandong Peninsula. In August, the green tide sinks and disappears (22). Coastal eutrophication of the South Yellow Sea is the most important environmental driver for the formation of the green tide (23). U. prolifera can utilize different nitrogen sources (inorganic and organic nitrogen), so strong nitrogen uptake, assimilation, and storage capacity are the key biological characteristics which have enabled it to become the dominant species of the green tide (23). The consumption of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients by U. prolifera significantly reduces its concentration in surface seawater (26). Meanwhile, the growth and death process of U. prolifera releases a large amount of dissolved organic matter (DOM) of different components (27, 28). The formation of a large amount of algal-derived organic matter over a short time is an important source of DOM in coastal areas (23, 28). Therefore, the ecological consequences of large-scale harmful macroalgal blooms are complicated, ranging from profound changes in geochemical cycling to instant fluctuations in planktonic and benthic organisms, especially microorganisms (23, 29).

Emerging studies have confirmed that microorganisms in the phycosphere may be crucial for the dynamics and succession of phytoplankton blooms (20, 30, 31). Much less is known about the formation mechanisms and ecological importance of the phycospheric microorganisms in HMBs such as green tide. In this study, two separate cruises were organized to follow floating U. prolifera at different stages of the green tide. During the cruise, phycospheric biological and environmental samples were collected. We used physiological and biochemical measurements and Illumina sequencing to investigate changes in environmental physicochemical and algal physiological characteristics, as well as variations in bacterial community composition, structure, and function. The interactions and linkages between environment-algae-bacterial communities were studied by partial least-squares structural equation modeling and co-occurrence network analysis. The assembly mechanisms of phycospheric bacterial communities were evaluated by the beta nearest taxon index (β-NTI) and additional Bray-Curtis-based Raup-Crick metric (RCbray) comparison using null model analyses. Our study generated information about the interaction and synergistic evolution between marine organisms and the environment, providing new ideas to increase our understanding of the variation patterns of macroalgal phycospheric microbial communities, as well as the formation mechanisms and ecological effects of green tides.

RESULTS

Variation and linkage of phycospheric biogenic elements and algal physiological state.

The environmental factors in the phycosphere and the physiological state of U. prolifera varied greatly between the early outbreak and outbreak stages of the green tide (Table 1). The concentrations of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP), and dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) were significantly higher in the early outbreak stage, while dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen (DOC and DON, respectively) increased during the outbreak stage. The average concentrations of DIN and DIP in the outbreak stage were 0.89 ± 0.09 and 0.03 ± 0.01 μM, respectively. Compared with the results for the early outbreak stage, DIN and DIP decreased by 94.65% and 94.23%, respectively. The average concentrations of DON and DOC in the outbreak stage were 8.49 ± 0.64 and 134.38 ± 1.02 μM, increases of 72.08% and 18.60%, respectively, compared with the results for the early outbreak stage. The average concentration of DOP was 0.06 ± 0.02 μM in the outbreak stage, a decrease of 66.67% compared with that in the early outbreak stage. In terms of physical parameters, temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) did not change significantly during the different outbreak stages. However, salinity did show some variation. We also measured the environmental factors of the adjacent seawater without floating algal cover as a control (Table 1). The main different environmental factors between the phycospheric seawater and the control seawater were nutrients (including DOC, DON, and DIN). The average concentration of DOC in phycospheric seawater was significantly higher than that in control seawater, and the difference was greater during the outbreak stage. The average concentrations of DON and DIN in phycospheric seawater were significantly lower than those in control seawater in the early outbreak stage. The average DON concentration in phycospheric seawater was higher than that in control seawater during the outbreak stage, but not significantly.

TABLE 1.

Average values of environmental factors and Ulva prolifera physiological state during different outbreak stagesa

| Survey data | Early outbreak stage (south of 35°N, n = 6) |

Outbreak stage (north of 35°N, n = 6) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phycospheric seawater | Seawater without algae cover | Phycospheric seawater | Seawater without algae cover | |

| Basic physicochemical factors | ||||

| Temp (°C) | 20.68 ± 0.16a | 20.25 ± 0.20a | 19.16 ± 0.44a | 20.13 ± 0.15a |

| Salinity (‰) | 30.53 ± 0.28a | 30.32 ± 0.10a | 31.74 ± 0.24b | 31.48 ± 0.40b |

| pH | 7.44 ± 0.17a | 7.81 ± 0.23a | 7.68 ± 0.12a | 7.95 ± 0.13a |

| DO (mg/L) | 4.30 ± 0.13a | 2.30 ± 0.02b | 4.31 ± 0.03a | 6.22 ± 0.06c |

| PAR (μmol photons/[m2·s]) | 386.34 ± 18.25a | 375.20 ± 20.80a | 363.12 ± 44.08a | 373.72 ± 19.25a |

| Major nutrients (μM) | ||||

| DOC | 109.38 ± 1.15a | 40.91 ± 2.64b | 134.38 ± 1.02c | 49.37 ± 3.19b |

| DON | 2.37 ± 0.11a | 8.66 ± 0.33b | 8.49 ± 0.64b | 5.61 ± 1.53b |

| DOP | 0.18 ± 0.02a | 0.30 ± 0.13a | 0.06 ± 0.02b | 0.12 ± 0.03b |

| DIN | 16.64 ± 0.52a | 28.1 ± 3.73b | 0.89 ± 0.09c | 1.00 ± 0.10c |

| DIP | 0.52 ± 0.04a | 0.41 ± 0.10a | 0.03 ± 0.01b | 0.02 ± 0.01b |

| Algal physiological state | ||||

| Fv/Fm | 0.80 ± 0.01a | 0.72 ± 0.01b | ||

| SOD (U/mg prot) | 102.83 ± 3.31a | 332.97 ± 9.88b | ||

| Y(NPQ) | 0.09 ± 0.02a | 0.11 ± 0.02a | ||

| NRA (μmol/L NO2−/[mg/h]) | 2.30 ± 0.27a | 0.73 ± 0.11b | ||

DO, dissolved oxygen; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; DON, dissolved organic nitrogen; DIN, dissolved inorganic nitrogen; DIP, dissolved inorganic phosphate; SOD, superoxide dismutase; Y(NPQ), quantum yield of regulated non-photochemical energy loss; NRA, nitrate reductase. Different letters above the average values indicate significant differences (Student’s t test, P < 0.05).

U. prolifera in the outbreak stage had a relatively poor growth status and suffered more environmental stresses than that in the early outbreak stage. Compared with those during the early outbreak stage, the Fv/Fm (ratio of variable fluorescence by maximum fluorescence) and nitrate reductase (NRA) values of floating U. prolifera in the outbreak stage were 0.72 ± 0.01 and 0.73 ± 0.11 μmol/L NO2− (mg/h), decreases of 10.00% and 68.26%, respectively. This indicated that the photosynthetic activity and nitrate assimilation capacity of U. prolifera were significantly lower during the outbreak stage than in the early outbreak stage. The average value of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was 332.97 ± 9.88 U/mg·prot in the outbreak stage, an increase of 223.81% compared to that in the early outbreak stage. This indicated that the antioxidant activity of U. prolifera was significantly higher during the outbreak stage than in the early outbreak stage and that the algal body suffered higher environmental stress pressure. Compared with the early outbreak stage, the average value of quantum yield of regulated non-photochemical energy loss Y(NPQ) was 0.11 ± 0.02 in the outbreak stage, which represented a slight but not significant increase of 22.22%, indicating that the algae were not suffering strong light damage.

The results of Pearson correlation analyses between the environmental variables and algal physiological state are shown in Fig. S3a. They indicate that phycospheric environmental factors, especially the major nutrients, were highly correlated with the physiological state of U. prolifera. DOC and DON showed significant positive correlations with SOD (RDOC = 0.990, RDON = 0.979) and negative correlations with NRA (RDOC = −0.962, RDON = −0.955). DIN and DIP showed significant negative correlations with SOD (RDIN = 0.998, RDIP = −0.994) and positive correlations with NRA (RDIN = 0.968, RDIP = 0.961) and Fv/Fm (RDIN = 0.949, RDIP = 0.932). An RDA analysis was used to evaluate whether the phycospheric environmental variables and physiological state of U. prolifera relationships among the algal samples had a significant spatial dynamic (Fig. S3b). The RD1 and RD2 axes account for 99.97% and 0.03% of the total variation, respectively. Algal samples from different outbreak stages were significantly separated along the RD1 axis. DIN, DIP, DOC, and DON were the main explanatory variables for the variation in algal physiological state.

In summary, phycospheric environmental variables are strongly correlated with the physiological state of U. prolifera, particularly environmental nutrients. The rich inorganic nutrients in the early outbreak stage promote the photosynthetic activity and nutrient assimilation ability of the algae, which is beneficial to the growth of U. prolifera. The deterioration of the algal growth state during the outbreak stage was reflected in an increase in antioxidant activity, while the metabolic activity of the algae depleted inorganic nutrients and promoted the release of DOM.

Changes in bacterial community composition and structure.

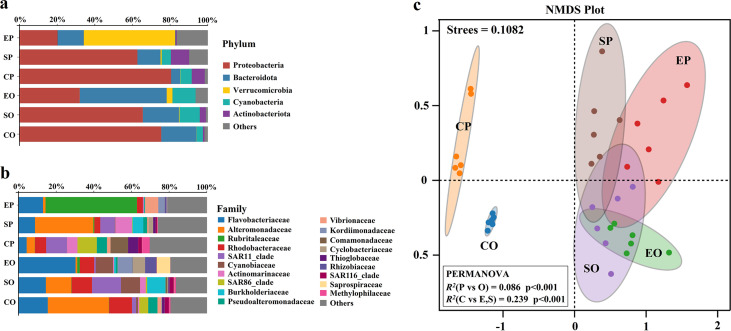

The dominant bacterial phyla, families, and genera with relative abundance above 1.00% were calculated (Fig. 1a and b; Fig. S4). The dominant bacterial phyla included Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Cyanobacteria, and Actinobacteria (Fig. 1a). Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes showed two opposite trends in the comparison between sample groups: Proteobacteria were more abundant in control seawater (75% to 81%) than in phycospheric seawater (62% to 65%) or algal surfaces (20% to 32%) while Bacteroidetes were more abundant on the algal surface (13% to 46%) than in phycospheric seawater (12% to 19%) or the control seawater (4% to 18%). During the early outbreak stage, Verrucomicrobia was enriched on the algal surface (49%), and Actinobacteria was enriched in the phycospheric (10%) and control seawater (7%). During the outbreak stage, Cyanobacteria was enriched in the phycosphere (10% to 12%). The dominant bacterial families mainly included Flavobacteriaceae, Alteromonadaceae, Rubritaleaceae, and Rhodobacteraceae (Fig. 1b). Flavobacteriaceae (14% to 30%) and Rhodobacteraceae (7% to 12%) were more abundant in samples from the outbreak stage. Alteromonadaceae was enriched in phycospheric seawater during the early outbreak stage (30%) and in control seawater during the outbreak stage (32%). Rubritaleaceae was only enriched on the algal surface during the early outbreak stage (49%).

FIG 1.

Taxonomic composition and structure of bacterial communities. Histograms show the phyla (a) and families (b) with relative abundance greater than 1.00%. (c) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis distances reveals changes in the bacterial community structure. Samples with similar community compositions are closer together in the NMDS plot. Some of the permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) results are shown. EP, SP, and CP refer to the epiphytic bacteria, phycospheric seawater bacteria, and control seawater bacteria in the early outbreak stage, respectively. EO, SO, and CO refer to the epiphytic bacteria, phycospheric seawater bacteria, and control seawater bacteria in the outbreak stage, respectively.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis based on Bray-Curtis distances was carried out for all sample groups to evaluate whether the bacterial community composition among the samples had a significant spatial dynamic (Fig. 1c). Phycospheric bacterial samples, including phycospheric seawater bacterial (SP and SO) and epiphytic bacterial samples (EP and EO) were separated from control seawater bacterial samples (CP and CO) on the horizontal axis. Moreover, the samples collected from the early outbreak stage (EP, SP, and CP) and outbreak stages (EO, SO, and CO) could be distinguished on the vertical axis. The result of a permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) showed that the bacterial community structures of all sample groups were significantly different from each other (R2 = 0.594, P < 0.01) (Table S2). The differences in bacterial community structure between the phycospheric and control seawater samples (R2 = 0.239, P < 0.01) were significantly greater than those between the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage samples (R2 = 0.086, P < 0.01) (Fig. 1c). The differences between the SP and SO sample groups (R2 = 0.194, P < 0.01) were smaller than those between the EP and EO groups (R2 = 0.289, P < 0.01). The differences between the EO and SO sample groups (R2 = 0.256, P < 0.01) were smaller than those between the EP and SP groups (R2 = 0.374, P < 0.01). In summary, the composition and structure of bacterial communities in the phycosphere were significantly different from those in adjacent seawater without floating algal cover (Fig. 1c). In the phycosphere, the epiphytic bacterial community structure appeared more altered than that of the phycospheric seawater bacterial community (Table. S2). Differences in the structure of epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacterial communities diminish with the migration of green tides (Table. S2).

Fluctuations and diversity patterns of phycospheric bacterial communities.

Sequencing data were obtained from all samples. A total of 2,653,806 sequences were retained after removing low-quality reads. The Good’s coverage of all sequencing samples was greater than 99.2%, indicating that the sequencing depth of all the samples could represent the real bacterial community (Table S3). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a 97% similarity cutoff were clustered. The mean number of OTUs in the early outbreak stage was 301.83 ± 35.80 in the epiphytic bacterial sample, 412.00 ± 69.74 in the phycospheric seawater bacterial sample, and 301.33 ± 74.90 in the control seawater bacterial sample. The mean number of OTUs in the outbreak stage was 482.83 ± 74.72 in the epiphytic bacterial sample, 345.67 ± 42.99 in the phycospheric seawater bacterial sample, and 334.66 ± 4.67 in the control seawater bacterial sample (Table S3).

The richness and diversity of the bacterial communities were analyzed using alpha diversity indices, including the Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices (Table S3 and Fig. S5a). The alpha index of control seawater bacterial communities did not change significantly. A significant increase was found in the richness and diversity of epiphytic bacterial communities during the outbreak stage of the green tide compared with that in the early outbreak stage (P < 0.01). The Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson index values of epiphytic bacterial samples in the early outbreak stage (EP) were 294.30 ± 31.77, 3.34 ± 0.72, and 0.72 ± 0.12, respectively, representing increases of 61.97%, 63.90%, and 28.01% compared to these values during the outbreak stage (EO). A significant decrease in the richness of phycospheric seawater bacterial communities was also found in the outbreak stage. The Chao1 value of phycospheric seawater bacterial samples in the early outbreak stage (SP) was 435.29, which decreased by 35.78% in the outbreak stage (SO). However, the Shannon and Simpson index values did not change significantly. The richness and diversity of bacterial communities at different spatial locations in the phycosphere during the same stage also differed. The Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson index values of epiphytic bacterial samples were significantly lower than those of phycospheric seawater bacterial samples in the early outbreak stage (P < 0.05). However, the Chao1 value of epiphytic bacterial samples was significantly higher than that of phycospheric seawater bacterial samples during the outbreak stage, while the Shannon and Simpson indices also exceeded those of phycospheric seawater bacterial samples (but not significantly).

Variations in identical and unique OTUs among epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacterial communities were further explored using Venn diagrams (Fig. S5b). The total number of identical OTUs in the four sample groups was 322. Phycospheric seawater bacterial samples in the early outbreak stage contained the highest number of unique OTUs (424), followed by epiphytic bacterial samples in the outbreak stage (288). The unique OTUs of epiphytic bacteria and phycospheric seawater bacteria varied widely among different outbreak stages (Fig. S5c). Compared with those during the early outbreak stage, the unique OTUs of epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacterial samples in the outbreak stage increased by 27.69% and decreased by 21.12%, respectively. Unlike those in the early outbreak stage, the unique OTUs of epiphytic bacteria during the outbreak stage were higher than those of phycospheric seawater bacteria, and the identical OTUs between epiphytic bacteria and phycospheric seawater bacteria increased by 18.28% (Fig. S5c).

Potential environmental drivers for phycospheric bacterial community.

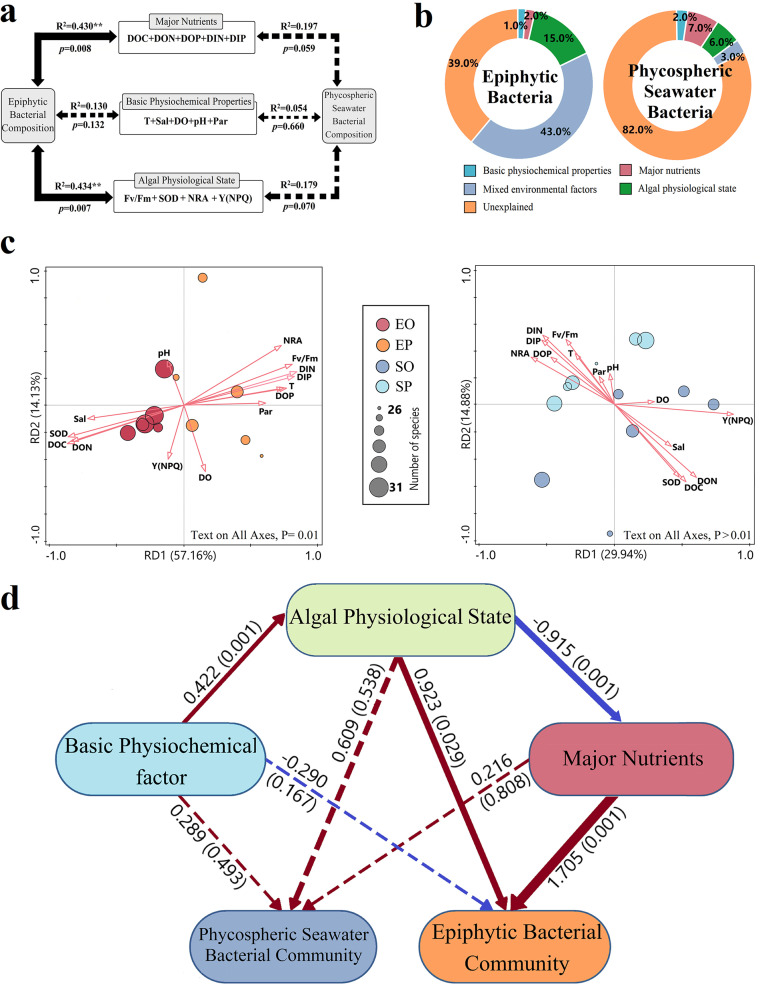

The Mantel test was used to determine the correlation between environmental factors and bacterial community composition. Fig. 2a shows how the epiphytic bacterial community composition was significantly correlated with the major nutrients and the algal physiological state (P < 0.01). The correlation between the major nutrients and the algal physiological state on the phycospheric seawater bacterial composition was marginally significant (0.05 < P < 0.1). The correlation between major nutrients was higher than that of the algal physiological state. Variances of epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacterial compositions were analyzed using variation partitioning analysis (VPA). The results showed that environmental variables explained 61.0% and 18.0% of the variation in epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacterial community compositions, respectively (Fig. 2b). Among the environmental variables, the algal physiological state (i.e., Fv/Fm, SOD, NRA, and Y[NPQ]) explained about 15.0% of the variation in epiphytic bacterial community composition. Major nutrients (i.e., DOC, DON, DOP, DIN, and DIP) and algal physiological states explained 7.0% and 6.0% of the variance in the compositions of phycospheric seawater bacterial communities, respectively. However, basic physicochemical factors (i.e., temperature [T], salinity [Sal], DO, pH, and PAR) only explained 1.0% to 2.0% of the variance in the compositions of phycospheric bacterial community composition.

FIG 2.

Variations in the environmental driving force of the phycospheric bacterial communities. SP and SO refer to the phycospheric seawater bacterial sample groups in the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage, respectively. EP and EO refer to the epiphytic bacterial sample groups in the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage, respectively. (a) Mantel test for correlation between environmental factors, algal physiological state, and bacterial community composition. Black solid and dotted lines indicate significant and insignificant correlations, respectively. R2 indicates the correlation; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. (b) Variance partitioning analysis (VPA) shows the relationships of environmental variables to microbial community composition. (c) Redundancy analysis (RDA) is based on bacterial community composition (genus level) and environmental factors. (d) Pathway analysis using partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) on influential factors of the algal host and bacterial communities of the phycosphere. Single-headed arrows indicate the hypothesized direction of causation. Values on the line indicate relationship strength; P values are shown in parentheses. Solid and dotted lines indicate significant and insignificant relationships, respectively. Red and blue lines indicate positive and negative relationships, respectively. Arrow width is proportional to relationship strength.

RDA analysis was performed to discern the linkage between bacterial community composition and the environmental factors and physiological state of U. prolifera. Similar to the results of the VPA analysis, environmental factors explained more of the total variance in the community composition of epiphytic bacteria (RD1, 57.16%) than in that of phycospheric seawater bacteria (RD1, 29.94%). Fig. 2c shows that DOC, SOD, DIN, and Fv/Fm are the main explanatory variables for epiphytic bacterial community composition (P < 0.01). Of these, DIN and Fv/Fm have the largest positive effects on epiphytic bacterial community composition during the early outbreak stage. DOC and SOD have the largest positive effects during the outbreak stage. DON, DOC, DIN, DIP, and NRA are the main explanatory variables for phycospheric seawater bacterial community composition. Although the explanations of the conditional effects of all variables except for DON and NRA are not significant, it is still clear that DIN and NRA show positive effects with the composition of phycospheric seawater bacterial communities in the early outbreak stage and DON, DOC, and SOD show positive effects with the composition of phycospheric seawater bacterial communities in the outbreak stage.

Linkages among the environment-algae-bacterial communities were examined using partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM; Fig. 2d; Table S4). Seawater and epiphytic bacterial composition, algal physiological state, basic physiochemical factors, and major nutrients were selected as the important factors. In the phycosphere, the basic physicochemical factors and major nutrients had significant effects on the algal physiological state (P < 0.01), with contribution coefficients of 0.422 and 0.915. Algal physiological state and major nutrients had strongly positive effects on the epiphytic bacterial community, with contribution coefficients of 0.923 and 1.705 (P < 0.05). Both also had positive but not significant effects on phycospheric seawater bacterial communities. The effect of basic physicochemical factors on the bacterial community was weak in all cases. The SEM-PLS analysis showed a strong link between environment, algal, and bacterial communities in the green tide phycosphere. While physicochemical factors influenced the physiological state of the algae, algal metabolism also strongly influenced the nutrient concentration in the environment. Similar to the VPA analysis results, the algal physiological state and major nutrients strongly influenced the epiphytic bacterial community construction process but had a much weaker effect on the phycospheric seawater bacterial community.

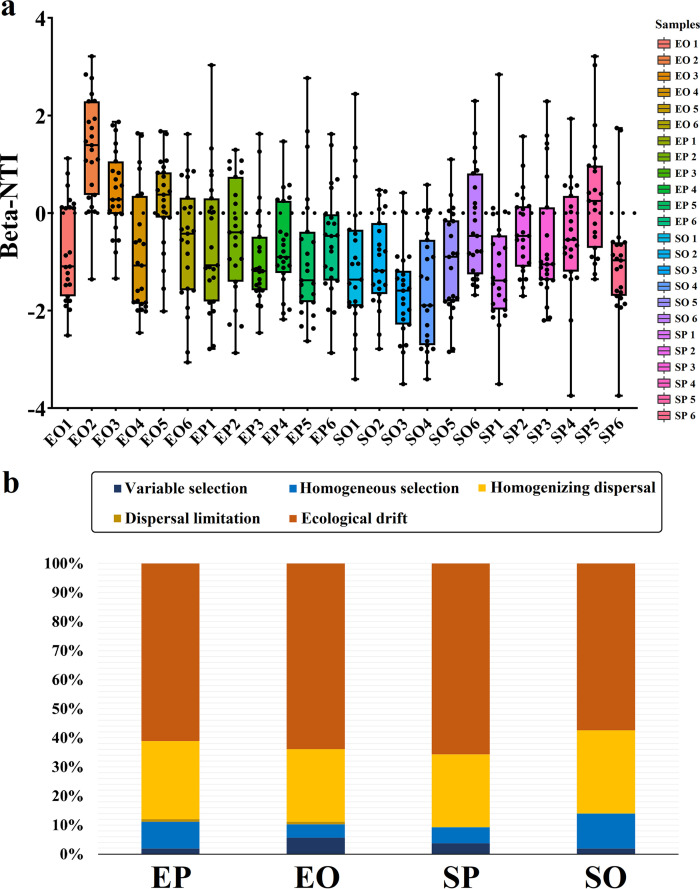

Assembly of the phycospheric bacterial communities.

Weighted β-NTI and RCbray were used in combination to approximate the relative contributions of the different processes of assembly, and a null model analysis was used to estimate the ecological processes which influence the composition of phycospheric bacterial communities. First, β-NTI and RCbray values were calculated to assess the relative importance of different assembly processes to phycospheric bacterial communities (Fig. 3). The β-NTI values were between −3.743 to 3.214 for all bacterial samples (Fig. 3a), indicating that both deterministic and stochastic processes were involved in the assembly of phycospheric bacterial communities. The stochastic processes, including ecological drift and homogenizing dispersal, were the main force influencing community assembly for all phycospheric bacteria during the early outbreak and outbreak stages, and explained 86.11% to 90.74% of community turnover (Fig. 3b).

FIG 3.

Assembly of the phycospheric bacterial communities. (a) Distribution of beta nearest taxon index (β-NTI) among different samples. (b) The contribution of deterministic and stochastic processes in microbial assembly. SP and SO refer to the phycospheric seawater bacterial sample groups in the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage, respectively. EP and EO refer to the epiphytic bacterial sample groups in the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage, respectively.

Deterministic processes include selection imposed by the abiotic environment (“environmental filtering”) and both antagonistic and synergistic species interactions. Although the contribution of deterministic processes to community construction was low (10.19% to 13.89%) (Fig. 3b), interesting variations existed between the two different stages. The contribution of homogeneous selection in phycospheric seawater bacterial assembly during the outbreak stage (12.04%) increased compared to that in the early outbreak stage (5.56%), suggesting the environmental heterogeneity of surface seawater in the algal mats. The contribution of variable selection in the epiphytic bacterial assembly process during the outbreak stage (5.56%) increased compared to that in the early outbreak stage (1.85%), revealing a potentially stronger selective effect of the host on bacteria colonizing the algal surface and stronger interspecific associations between bacterial groups. These results show that both stochastic and deterministic processes were main forces influencing the community assembly of phycospheric bacteria during early outbreak and outbreak stages.

Variation in the abundance of taxa with carbon or nitrogen metabolic potentials in phycospheric bacterial communities.

Functional annotation of OTUs was conducted using FAPROTAX (Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa, Fig. S6). We explored the taxa with carbon or nitrogen metabolic potential within the phycospheric bacterial community at two different stages. As a whole, the relative abundance of the taxa with carbon or nitrogen metabolic potential in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community was higher than that in the epiphytic bacterial community, while the abundance of each functional taxa differed. The abundance of taxa with potential functions of aromatic compound degradation, methylotrophy, hydrocarbon degradation, and aliphatic non-methane hydrocarbon degradation in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community during the outbreak stage increased by 76.99%, 59.86%, 59.29%, and 71.29%, respectively, compared to that in the early outbreak stage. The abundance of taxa with potential fermentation functions during the outbreak stage decreased by about 93% compared to that in the early outbreak stage. The functional changes of carbon metabolism in the epiphytic bacterial community were similar to those of phycospheric seawater bacteria, but the abundance of taxa with potential cellulose degradation and fermentation functions increased by about 947.06% and 197.04%, respectively, during the outbreak stage.

Taxa with potential functions of assimilatory nitrate reduction and dissimilatory nitrate reduction (including fermentative nitrate reduction and respiratory nitrate reduction) were the most dominant functional taxa for nitrogen metabolism in the phycosphere. During the outbreak stage, the abundance of taxa with potential functions of assimilative nitrate reduction and fermentative nitrate reduction functions decreased by 70.04% and 70.45%, respectively, in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community, and increased by 182.71% and 116.78%, respectively, in the epiphytic bacterial community, compared to that in the early outbreak stage. The abundance of taxa with potential functions of respiratory nitrate reduction increased by 92.13% in the phycospheric seawater bacterial communities and increased by 93.94% in the epiphytic bacterial communities during the outbreak stage compared to that during the early outbreak stage. The abundance of taxa with potential nitrogen fixation functions increased by 670.16% in the epiphytic bacterial community during the outbreak stage compared to that during the early outbreak stage. Taxa with urea catabolism function were highly abundant in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community during the outbreak stage, and taxa with nitrification function were highly abundant in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community during the early outbreak stage.

Topological characteristics of bacterial communities.

Co-occurrence network analysis can determine the coexistence of populations in bacterial communities, including the important interactions and pattern information, and further explain the formation mechanisms of phenotypic differences in phycospheric microbial community structure and function. We constructed bacterial co-occurrence networks based on Spearman correlations to investigate bacterial interconnections in the phycosphere areas during the U. prolifera outbreak (Fig. S7). Network properties generally considered to be ecologically relevant are also shown (Table S5). Nodes represent bacterial genera and edges represent significant relationships (r > 0.8, P < 0.05) in the network. The resulting networks of EP, EO, SP, and SO contained 149, 195, 176, and 154 nodes and 589, 870, 952, and 725 edges, respectively. The EO network complexity is higher than that of EP, and the SO network complexity is lower than that of SP. Positive correlation accounted for 65.53%, 55.40%, 57.35%, and 75.17% of the total relationships in the EP, EO SP, and SO sample groups, respectively. The results revealed enhanced interspecific competition among epiphytic bacteria and enhanced symbiotic relationships among phycospheric seawater bacteria during the outbreak stage. EO has higher network connectivity than EP because it has a higher average degree and smaller average path length. The decrease in density and eigenvector centrality indicates a rise in EO network stability. The decrease in modularity and average clustering coefficient indicates the smaller modularity of the EO network. Similarly, SO has lower network connectivity and stability and higher modularity compared to SP. These results show that the EO network was more complex, more connected, more stable, and less positively correlated and modular than the EP network. In addition, the SO network was less complex, less connected, less stable, and more positively correlated and modular than the SP network. The overall topological properties indicate that interspecies connections within the epiphytic bacterial community became stronger during the outbreak than during the early outbreak stage, while the opposite was true for the phycospheric seawater bacterial community.

Keystone genera variation driven by environmental factors.

Our results indicated that keystone genera differed significantly between stages (Fig. 4; Table S6). Limnobacter, Alteromonas, and Dokdonia were the core nodes of the phycospheric seawater bacterial community in the early outbreak stage. They dominated two clusters, one influenced by major nutrients and the other by algal physiological state. Pseudoalteromonas, Formosa, and Saprospira were the core nodes of the phycospheric seawater bacterial community during the outbreak stage. Each dominated a separate cluster influenced by mixed environmental factors. The core nodes of the epiphytic bacterial community during the early outbreak stage were Dokdonia, Formosa, and Rubritalea. These dominated a large tightly connected cluster influenced by the algal physiological state. Meanwhile, a loose cluster was also contained in the network which was influenced by major nutrients, with Vibrio and Pseudoalteromonas as the core nodes. Marinoscillum, Cobetia, and the SUP05_cluster were the core nodes of the epiphytic bacterial communities during the outbreak stage. They dominated a large cluster influenced by mixed environmental factors, and a small cluster was also contained in the network which was influenced by the algal physiological state, with Lentimonas as the core node.

FIG 4.

Nodal genera and dominant clusters in the phycosphere. In microbial networks, circle and square nodes represent individual genus and environmental factors, respectively. Their size is positively correlated with the node degree. The nodal numbers of clusters associated with environmental factors and their proportion to the network are also shown. Hexagons show the bacterial populations directly associated with the major nutrients and algal physiological state (r > 0.8 and P < 0.05). Red and blue lines indicate positive and negative correlations, respectively. SP and SO refer to the phycospheric seawater bacterial sample groups in the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage, respectively. EP and EO refer to the epiphytic bacterial sample groups in the early outbreak stage and outbreak stage, respectively.

In terms of the overall characteristics of the network, the highest association with environmental factors were EO and SO (44 significant edges each), followed by EP (38 significant edges), and SP (23 significant edges). The numbers of nodes directly and indirectly associated with environmental factors were 61 (EO), >58 (EP), >57 (SO), and >34 (SP), and the proportions of overall network nodes were 38.93% (EP), >37.01% (SO), >31.28% (EO), and >19.32% (SP) (Fig. 4). These results suggest that environmental factors have an important influence on the construction of interspecific relationships in phycospheric bacterial communities, as reflected by the fact that the keystone genera with significantly strong correlations with environmental factors occupy a fairly high proportion of nodes in the co-occurrence network.

Moreover, the percentage of keystone genera to total OTUs and the percentage of total 16S rDNA sequences were calculated to quantify the importance of keystone genera for the entire community assembly (Table S7). Results indicated that the number of keystone genera was small (15.28% to 24.69% of total OTUs), but their relative abundance was high, especially in the phycospheric seawater bacterial communities (more than 40.53% of total 16S rRNA sequences) and the epiphytic bacterial community in the early outbreak stage (61.43% of total 16S rRNA sequences). This indicates that keystone genera were important components of phycospheric bacterial communities during green tide migration outbreaks. It could be hypothesized that changes in the abundance of keystone genera could trigger covariation in the structure and function of the entire bacterial community. These results indicate that keystone genera might play important and intrinsic roles in maintaining interspecific relationships and community structure-function stability in phycospheric bacterial communities.

DISCUSSION

The U. prolifera green tide is the largest in the world, and its extensive and prolonged migration is its main feature. During its 400-km migration from offshore Jiangsu (32°N) to offshore Shandong (36°N), U. prolifera experiences rapid changes in environmental conditions, while the scale of the green tide expands (26, 32, 33). Therefore, the U. prolifera green tide outbreak provides ideal scenarios for studying the structure-function variation of phycospheric microorganisms and its ecological correlation with HMBs.

Variation in the nutrient structure of the phycosphere was closely related to the growth state of U. prolifera.

Our investigation found that the nutrient concentrations in the phycosphere were significantly different from those in the adjacent seawater without bloom coverage (Table 1); the nutrient concentrations in the phycosphere changed significantly with the development of the green tide and were closely related to the growth state of U. prolifera. In the phycosphere, all physicochemical factors were in the optimal growth range for U. prolifera (23). However, the organic and inorganic nutrient levels of the phycosphere changed significantly. In the early outbreak stage, the phycosphere environment was eutrophic, with high concentrations of inorganic nutrients, mostly DIN (Table 1). The concentrations of inorganic nutrients significantly exceeded the minimum limiting concentrations for U. prolifera growth (34, 35). During the outbreak stage, the inorganic nutrient content was extremely low while the organic nutrient concentrations (mostly DOC and DON) were significantly higher than those in the early outbreak stage. Thus, variation in nutrient structure was the most important differential feature of the phycosphere.

The background concentrations of nutrients in different sea areas were different. The 35°N latitude line crosses the middle of Haizhou Bay. The sea area south of 35°N is strongly influenced by near-shore currents and terrestrial runoff (36). These conditions have resulted in a low-salinity, high-nutrient eutrophic surface layer extending to the northeast. Offshore aquaculture activities have further increased the concentration of nitrogen and phosphorus in this area (37). In contrast, the sea area north of 35°N is far from land and terrestrial influences. This area is influenced by the Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass (YSCWM), which forms a strong thermocline in spring and summer (38). Therefore, the mixing effect is weakened and the nutrient concentration in the upper layer of this area is maintained at a low level in summer.

Field and laboratory studies have indicated that inorganic nutrients, particularly DIN, are the key abiotic factors controlling the scale and output of U. prolifera green tides (26, 39) and that high DIN (especially NO3−) concentration promotes rapid growth of U. prolifera (40). Our results confirmed that biological characteristics such as photosynthetic activity and nutrient uptake of the U. prolifera were most sensitive to the concentration change of DIN (Fig. S3), suggesting that DIN in the phycosphere was an important factor contributing to the early formation and development of green tide in the early outbreak stage. It can be hypothesized that in addition to the thermocline of the YSCWM and the lack of large nutrient input sources, algal uptake is one of the primary reasons for the low inorganic nutrient concentrations in the phycosphere during the outbreak stage. The nutrients were insufficient for supporting the steady and rapid growth of large-scale green tides, leading to deterioration in the growth state of the U. prolifera.

The increase in antioxidant activity indicated that the algae were under more intense environmental stress during the outbreak stage (Table 1). Furthermore, the DOC and DON concentrations were significantly and positively correlated with SOD (Fig. S3a). Studies have demonstrated that algae, including U. prolifera excrete DOM to the surrounding seawater during growth (27, 28). More importantly, large amounts of DOM are released with the hydrolysis and decomposition of U. prolifera cells caused by environmental stress (e.g., high temperatures and limited nutrients) (23, 28, 41). By comparing with the control seawater, we suggested that the rapid accumulation of U. prolifera biomass likely contributed to the increase of total DOM in the phycosphere. These combined results suggest that the outbreak of U. prolifera resulted in significant differences in nutrient concentrations between the phycosphere and adjacent seawater. In addition, changes in the physiological state of U. prolifera with the development of the green tide were the main contributors to the changes in phycospheric nutrient levels between the two green tide stages.

Deterministic and stochastic processes combine to influence the phycospheric bacterial community assembly.

The metabolic products of U. prolifera changed the nutrient structure of the phycosphere and provided nutrients for bacterial reproduction, which in turn attracted planktonic bacteria to the phycosphere. Our investigation revealed that the green tide phycosphere had a complex and diverse bacterial community, including both free-floating phycospheric seawater bacteria and epiphytic bacteria colonizing the algal surface (Fig. 1). The composition and structure of bacterial communities in the phycosphere were significantly different from those in adjacent seawater without floating algal cover (Fig. 1c; Table S2). The diversity, composition, and structure of bacterial communities in the phycosphere evolved in response to the green tide migration, but the trends differed (Fig. S5). With the green tide outbreak, epiphytic bacterial communities showed more new bacterial populations colonization, increased diversity, and stronger interspecific associations. In contrast, the richness of phycospheric seawater bacterial communities decreased and its interspecific associations became weaker (Fig. S5; S7).

Stochastic process dominant microbial assembly is commonly found in studies of aquatic systems (e.g., lake, river, and ocean) and indicates that fluidity and connectivity could contribute to stochasticity (42–44). Null-model analyses indicated that stochastic processes, including ecological drift and homogenizing dispersal contributed a bigger role than deterministic processes in shaping U. prolifera phycospheric bacterial community structure (Fig. 3b). Ecological drift (inherent random processes of birth, death, and reproduction) played critical roles in shaping the structure of bacterial communities and can alter community structure and biogeographic patterns even in the absence of selection (45). Unlike the rhizosphere, algal-bacterial interactions occurred in a turbulent environment, which influenced both the physicochemical characteristics of the phycosphere and how “native” microorganisms entered the phycosphere. Planktonic bacteria could disperse into the phycosphere through three potential mechanisms, including random encounters, chemotaxis, and vertical transmission (3). Chemotaxis (the capacity to migrate up or down chemical gradients) is pervasive among natural assemblages of marine bacteria, enabling them to exploit localized chemical hot spots such as the phycosphere (4). Our results confirmed that the epiphytic bacterial community was strongly influenced by the algal physiological state and the concentration of major nutrients (Fig. 2). Since algal surface provided additional ecological advantages for bacteria compared to seawater, including resistance to environmental stress, access to more nutrient resources, and increased opportunities for interactions with algae (9, 46), which suggests that chemotaxis could be the main potential mechanism by which bacteria are attracted to U. prolifera. In contrast, random encounters and vertical transmission could be the main potential mechanisms for planktonic bacteria that entered the phycosphere and remain in seawater, especially in the early outbreak stage. Through field observation, it can be determined that the floating U. prolifera was mostly in the form of patches in the early outbreak stage, and the barrier effect of algal mats on turbulence was weak. Complex mixing and agitation likely weakened the selective forces, which may favor the entry of planktonic bacteria into the phycosphere through stochastic processes such as random encounters and vertical transmission.

Notably, differences in chemical composition between algae-derived DOM underpin bacterial chemotaxis behavior, leading to taxonomic and functional partitioning of prokaryotic communities at the ocean’s microscale (4). The characteristics of the compounds exuded by algal cells are influenced by the algal growth state. For example, during early growth stages, algal cells generally release soluble, highly inert, low molecular weight (LMW) molecules such as amino acids, carbohydrates, sugar alcohols, and organic acids (47, 48). As cells senesce, higher molecular weight macromolecules (HMW), including polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, are released through exudation or cell lysis (48, 49). Similarly, the specific weight of different molecular weight fractions of organic matter secreted by U. prolifera at different growth stages is significantly different. The composition of DOM from U. prolifera is rich in labile amino acids, sugars, and lipids. More LMW soluble organic matter (<1 kDa, small peptides, oligopeptides, oligosaccharides, oligonucleotides, and vitamins) was leached during the early growth while decaying U. prolifera cells release more HMW organic matter (>10 kDa, humic substances, peptides, proteins) (50, 51). Differences in molecular weights of compounds affect their diffusion distance and stability in the phycosphere (3). LMW compounds diffuse rapidly under turbulence, while HMW compounds diffuse more slowly, which increases their residence time in the phycosphere and limits their loss to seawater. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that the release of LMW compounds from healthy U. prolifera in the early outbreak stage became a strong chemoattractant for bacteria, which facilitated the rapid attraction of planktonic bacteria into the phycosphere and promoted bacterial community colonization. During the outbreak stage, the overall weaker growth state of U. prolifera in the floating algal mats and weak turbulence resulted in the release and retention of HMW compounds, which expanded the range of organic matter concentrations and nutrient gradients in the phycosphere and enhanced the effect of the chemotaxis on the overall bacterial community assembly process.

Changes in the local environment progressively increase the importance of deterministic selection (52). Although the contribution of deterministic processes was lower than stochastic processes (Fig. 3b), they were still important for the phycospheric bacterial community assembly, and the contribution of deterministic processes to assembly varied among phycospheric seawater bacteria and epiphytic bacteria (Fig. 3b). The enhanced contribution of variable selection (biotic interactions) to the assembly of epiphytic bacterial communities implies that the assembly of epiphytic bacterial communities during the outbreak was more strongly driven by U. prolifera and members within the community. The ability of terrestrial plants and marine algae to adapt to environmental change through selective enrichment or inhibition of microbial communities by metabolites has been widely studied (3, 46, 53, 54). The stronger environmental stress pressure on U. prolifera during outbreaks may have also enhanced the selection pressure of the U. prolifera on epiphytic bacterial communities, but more metabolic data are needed to support this speculation. Interspecies connections within the epiphytic bacterial community became stronger during the outbreak stage and were dominated by interspecific competitive relationships, suggesting that selection pressure from intra-community members may be a potential driver of epiphytic bacterial community assembly. We hypothesize that multiple mechanisms (e.g., biotic competition, and host selection) combine to generate a stronger selective environment on the algal surface with the green tide development. Results confirmed that the enhanced heterogeneity of the algal surface resulted in more dramatic changes in the community structure of the epiphytic bacteria compared to phycospheric seawater bacteria (Fig. 1). Compared to the early outbreak stage, the organic nutrient concentration in the phycosphere was higher, and the phycospheric spatial structure was more stable during the outbreak stage (Fig. 5; Table 1). Unlike with epiphytic bacteria, the heterogeneity of the phycospheric seawater enhanced the contribution of homogeneous selection (environmental filtering) to phycospheric seawater bacterial community assembly. A decrease in the richness and a weakening of interspecific community associations in phycospheric seawater bacterial communities was observed during the outbreak stage (Fig. S5a; Table S5). It could be explained that as the strength of selection increases leading to an increasingly large breadth of taxa were excluded, the bacterial assemblage may ‘simplify’ as superior competitors begin to dominate (52). The decreased difference in community structure between the epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacteria were observed (Fig. 1c; Table S2), suggesting enhanced homogenization of the algal surface and phycospheric seawater during outbreak stage.

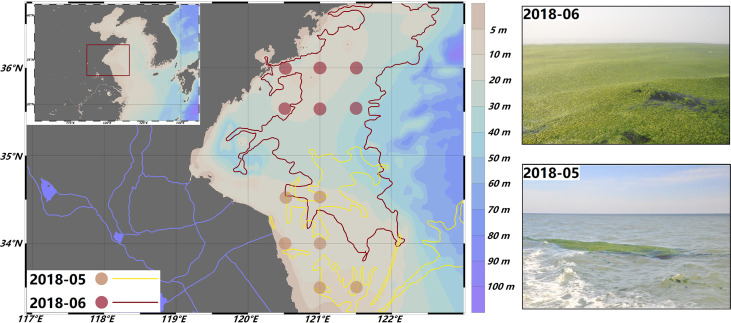

FIG 5.

Information of the sampling areas in the Yellow Sea. Sampling sites and distribution area of floating algae during the early outbreak (yellow) and outbreak (red) stages are shown. The green tide distribution data were obtained from the North China Sea Marine Forecasting Center of State Oceanic Administration (http://www.nmfc.org.cn/).

The metabolic activity of bacterial communities affects phycospheric material cycling and influences the effective utilization of nitrogen by the U. prolifera.

The above results suggested that the algal host could be strongly involved in the assembly process of epiphytic and phycospheric seawater bacterial communities through chemical production in the phycosphere. The response of the bacterial community to variations in the concentration and composition of nutrients in the phycosphere was reflected in the evolution of the abundance of functional taxa. Our results confirmed that the abundance of taxa with carbon or nitrogen metabolic potentials changed between two different green tide stages (Fig. S6). The high abundance of taxa with potential fermentation function suggested that phycospheric seawater and epiphytic bacterial communities have a strong potential to metabolize LMW-DOM (Fig. S6a). The metabolic potential of the epiphytic bacterial community for LMW-DOM was further enhanced and much higher than that of the phycospheric seawater bacterial community in the outbreak stage (Fig. S6a). It can be proposed that the LMW-DOM in the phycosphere was mainly utilized by the epiphytic bacterial community during the outbreak stage. This provided a usable and efficient carbon source for the rapid development of the epiphytic bacterial community and promoted the further development of its community structure. Furthermore, phycospheric seawater bacteria have a greater potential to metabolize complex compounds (Fig. S6a). The taxa with potential xenobiotic biodegradation function (including aromatic compound degradation, methylotrophy, lipid degradation, etc.) had a higher abundance advantage and increase trend in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community during the outbreak stage compared to epiphytic bacteria (Fig. S6a). Importantly, taxa with potential cellulolysis were extremely abundant only in the epiphytic bacterial community during the outbreak stage (Fig. S6a). This was closely related to the decay of the algal host and could play an important role in instigating the collapse and subsequent decomposition of the green tide bloom.

We found that the phycospheric bacterial community influences the material cycle of the phycosphere and also had a potential impact on the growth of the algal host. The nitrogen metabolic processes involved in marine microorganisms affected the nitrogen transformation, leading to the transport and exchange of nitrogen between the water column, air, and sediment (55). The availability of nitrogen is crucial for the growth of U. prolifera (26, 39). Taxa with potential assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reduction functions existed in phycospheric bacterial communities (Fig. S6b), which are capable of utilizing DIN for inorganic nitrogen metabolism and assimilating it as its nitrogen source or as an electron acceptor for anaerobic respiration. The high abundance of related taxa at the early outbreak stage may be related to the high concentration of DIN in the phycosphere (Table 1). In addition to nitrogen sources, microbial community nitrogen metabolic processes were also limited by carbon sources (55, 56). During the outbreak stage, competition for DIN utilization by U. prolifera and the increased content of HMW-DOM reduced NO3- supply and organic carbon availability, probably limiting the associated nitrogen metabolic processes of the phycospheric seawater bacterial community. In contrast to phycospheric seawater bacteria, the ecological niche advantage and the LMW carbon source provided by the algal host ensured the supply of organic carbon to the nitrogen metabolic processes of the epiphytic bacterial community during the outbreak stage, thus promoting the continued growth of the abundance of the taxa with potential nitrogen assimilation function in the epiphytic bacterial community (Fig. S6b).

The process of “cooperation and competition” between microorganisms and U. prolifera was reflected in the development of the green tide. The initial outbreak and migration of the green tide were probably supported by the taxa with nitrogen metabolic potentials of phycospheric bacterial communities, which increased the effective nitrogen content available to U. prolifera. During the early outbreak stage, associated functional taxa probably converted NOX-N to NH4-N, which was more readily absorbed and utilized by the U. prolifera, through fermentative nitrate reduction. During the outbreak stage, the increased abundance of taxa with xenobiotic biodegradation potential in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community (Fig. S6a) probably promoted the remineralization of nitrogenous organic matter. Meanwhile, the high abundance of taxa with nitrogen fixation potential existed in the epiphytic bacterial community may convert molecular nitrogen into nitrogen compounds, which could be absorbed and utilized by U. prolifera. The increased abundance of taxa with respiratory nitrate reduction (denitrification) potential during the outbreak stage probably inhibit the growth of U. prolifera biomass, as associated taxa could consume nitrate and produce gaseous N2O and N2, resulting in a loss of nitrogen. However, the functional inference based on 16S data only reflects the abundance of taxa with carbon or nitrogen metabolic potentials. The actual contribution of bacteria to carbon flux and nitrogen flux variations in the phycosphere requires further investigation.

Keystone genera determine the variation of bacterial community structure and function.

Algal types and environmental conditions in the ocean vary. Although bacterial communities are highly specific to algal hosts, some bacterial taxa are always present with high abundance (57); for example, Alteromonadaceae, Burkholderiaceae, Flavobacteriaceae, Rubritaleaceae, Saprospiraceae, and Vibrionaceae (3, 6, 15, 58, 59). These taxa were also dominant in the U. prolifera-associated microbiome in the present and previous investigations (29, 60). There could be an ecological correlation between the periodic outbreaks of the green tide and the recurrence of dominant taxa.

Our results revealed that 39.0% of the variation in epiphytic bacterial community composition and 82.0% of the variation in the phycospheric seawater bacterial community composition could not be explained by the measured parameters (Fig. 2b). Therefore, unidentified factors or biotic parameters (e.g., community interactions) were involved in shaping the community structure during the U. prolifera bloom. Diverse network relationships (positive or negative) were observed in phycospheric bacterial communities (Fig. S7). The interactions demonstrated that biotic factors (co-occurrence or exclusion) were important for shaping microbial composition (3, 61, 62). Our study found that some bacterial genera became “core nodes” in the phycospheric bacterial community network because they had strong associations with many genera, thus forming large clusters of associated species (Fig. 4). Although keystone genera’ numbers were small, they accounted for a large proportion of the abundance in the entire community, especially during the initial construction of phycospheric bacterial community in the early outbreak stage (Table S7; Fig. S4). Changes in their abundance led to symmetrical changes in the corresponding clusters, which could result in the structure-function covariation of the entire bacterial community. By studying the variation patterns of keystone genera associated with major nutrients and algal physiological states, we can obtain information on the interspecies interaction in the phycosphere and further reveal the action mechanisms of phenotypic variations in bacterial communities.

The presence of keystone genera in the early outbreak stage strongly influenced the initial structure and stability of the bacterial community in the phycosphere, especially the epiphytic bacterial community (Fig. 4). Opportunistic populations such as Alteromonas, Dokdonia, and Limnobacter were susceptible to the strong influence of chemotaxis due to their specific substrate utilization strategy (63–65). These populations could enter the phycosphere early to seize ecological niches and play a central role in the construction of microbial communities as “pioneer microorganisms.” These pioneer microorganisms could rapidly adapt to the specific trophic structure of more LMW algal-derived organic matter in the early outbreak stage. For example, Limnobacter uses small molecules such as carboxylic acids and amino acids as energy and carbon sources, while carbohydrates or polyols cannot be used by it (64). The specificity of metabolic substrates makes Limnobacter strongly subject to chemotaxis into the phycosphere. As algal polysaccharides and alginate degrading bacteria, Alteromonas and Dokdonia are strongly attracted to algal-derived metabolites (63, 65). Vibrio and Pseudoalteromonas have similarly been shown to have complex substrate utilization strategies. Because of their biofilm-forming properties, they can easily colonize algal surfaces and provide a sticky substrate for colonization by other bacteria (27, 66, 67). The above keystone genera were significantly associated with about 39% of the genera in the epiphytic bacterial network and were mostly dominated by positive interspecific relationships (65.53%) (Fig. 4, Table S5), indicating that they strongly influenced the initial structure of the bacterial community on the surface of the U. prolifera during the early outbreak stage.

Entering the outbreak stage, new genera take over the central position of some opportunistic pioneer microorganisms in the community (Fig. 4). However, the evolutionary direction of keystone genera in seawater and the algal surface differed. In the phycospheric seawater bacterial community, bacteria with the potential capacity of utilizing HMW substrates became keystone genera. The nitrogen metabolizing functional bacteria became the keystone genera in the epiphytic bacterial community. The LMW components can be readily utilized by microbes but HMW substrates need to be degraded to small molecules by extracellular enzymes secreted by microbes, a process that often requires multispecies collaboration (1, 68). Therefore, during the outbreak stage, phycospheric seawater bacterial communities contained more complex and independent functional clusters of carbon metabolism in response to the high HMW substrate status of the phycosphere, which was also reflected in the community topology characterized by increased modularity and reduced connectivity (Table S5). Multispecies cooperation also led to a significant increase (57.35% to 75.17%) in positive interspecific relationships. The three clusters with Formosa, Saprospira, and Pseudoalteromonas as core nodes comprised about 37% of the phycospheric seawater bacterial network during the outbreak stage. All members of Saprospira can hydrolyze carbon polymers, especially proteins (58). The Formosa members are efficient degraders of complex polysaccharides (63). Formosa and Saprospira all belong to the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides group (CFB-group), which has been shown to colonize mostly organic-rich habitats and is important for the turnover of organic matter.

In addition to the polysaccharide degraders Lentimonas (64), The large cluster with Marinoscillum and nitrogen metabolizing bacteria SUP05 and Cobetia as the core contained about 24% of genera in the epiphytic bacterial network (Fig. 4). Members of the SUP05 clade can use organic and inorganic substrates for autotrophic and heterotrophic growth, reducing nitrate and nitrite to gaseous nitrogen and causing nitrogen loss in marine systems (69, 70). Members of Cobetia can adapt to oligotrophic conditions and fix nitrogen, which compensates for denitrification (71). Meanwhile, Cobetia spp. are hydrocarbon-degrading and biosurfactant-producing, which display a functional potential to inhibit biofilm growth (72). We hypothesized that trophic diversity and different metabolic properties allow SUP05 and Cobetia to adapt to changes in nutrient levels. Colonization of algal surfaces increases their opportunities to interact with algae, which in turn affects the utilization of effective nitrogen by U. prolifera during the outbreak stage. The taxonomic and physiological properties of Marinoscillum have been poorly investigated. Some studies confirm that Marinoscillum is the heterotroph responsible for the generation of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) and degradation of EPS and cell material through N-acetyl-d-glucosamine utilization (73, 74). It is speculated that its presence may be involved in biofilm development, affecting the attachment environment of other bacteria. This hypothesis needs to be confirmed by more studies.

By summarizing the available studies, we found some common patterns. Some specific bacterial populations are closely related to the fate of algal blooms (both phytoplankton and macroalgal blooms). Alteromonas–Pseudomonas–Vibrio group (APV group) is frequently characterized as r-strategists (65), colonizing quickly and promoting the growth of more specialized taxa. Similar to our observation, the APV group has been also found in the early stage of phytoplankton and brown macroalgal bloom events and was closely associated with them (30, 31, 59, 75, 76). The advantage of opportunistic selection is the key to the rapid colonization of this taxon. In addition to their dominance in abundance (Fig. S4; Table S6), our work emphasizes that this group played a role in the early associated bacterial community construction of HMBs through complex community interactions and becomes one of the possible biological elements contributing to the eventual outbreak of algal bloom events (Fig. 4). The exploitation and competition of resources became the theme in interspecific relationships during the late stages of HMBs, which depended heavily on the availability of algal-derived substrates. CFB-group and nitrogen metabolism bacteria can compete and grow under complex nutrient conditions through their diverse substrate utilization strategies. Bacterial remineralization supplies nitrogen and other critical resources to support algal growth also reported in field studies of planktonic algal bloom events in both marine and freshwater environments (20, 60, 76, 77). It provides insights that bacterial groups with specific ecological strategies always accompany the emergence of HMBs and are closely related to the fate of HMBs.

Conclusion.

The structure-function variation of phycospheric microorganisms and its ecological correlation with the HMBs were investigated in the natural dynamic process of U. prolifera green tide. Our results clearly showed the significant variations in the phycospheric environmental physicochemical characteristics, the algal physiological state, and the assembly mechanism and functional characteristics of the phycospheric bacterial community at different stages of the U. prolifera green tide. Complex interactions and linkages existed between environment-algae-bacterial communities in the phycosphere. Our study provides new ideas to increase our understanding of the variation pattern of macroalgal phycospheric microbial communities, as well as the formation mechanism and ecological effects of green tides and highlights the importance of phycospheric microorganisms as a robust tool to help understand the fate of the HMBs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and survey methods.

Studies have revealed that the distribution and coverage areas of the U. prolifera green tide have similar development processes every year (22, 23). After a green tide originates in the southern Yellow Sea from mid-April to early May, its biomass and coverage area usually reaches a peak in June after drifting to the sea area of north 35°N. Therefore, studies generally divide the development of the green tide into two stages based on variations in the green tide growth stage, distribution, and coverage area: the early outbreak stage (sea area south of 35°N is the main floating area, and the green tide is in its exponential phase) and the outbreak stage (sea area north of 35°N is the main floating area, green tide is in its plateau phase).

In 2018, the U. prolifera green tide affected China’s Yellow Sea coastal waters from late April to mid-August. On April 25, a sporadic patch of U. prolifera was found floating in the waters of Nantong, Jiangsu Province (32°N). The green tide grew rapidly and drifted northward, crossing the 35°N latitude line on May 26. The distribution and coverage area reached their maximum on June 29 (38,046 km2 and 193 km2, respectively). Two cruises were organized to investigate this green tide, one in late May in the sea areas south of 35°N (early outbreak stage) and one in late June in the sea areas north of 35°N (outbreak stage). Six sampling sites were designated for each cruise to track the main floating algal patches. The surface seawater and floating algal samples were collected randomly from the floating algal mats (0 to 20 cm) at each sampling site (Fig. 5; Table S1).

Sampling procedures.

Phycospheric samples, including floating algae and phycospheric seawater, were collected from a 0- to 20-cm depth at the center of the algal mats at each site (Fig. S1a; S1b). The floating algae in this location were dense and could represent the growth state of the entire floating population (25). The floating algae and interstitial seawater (average distance from the thalli = less than 5 mm) were collected simultaneously by sterilized samplers (three biological replicates) and then separated by sterile screens with 2-mm pores. The interstitial seawater was considered to be the phycospheric seawater (Fig. S1c). The control seawater samples were collected from a 0- to 20-cm depth in the adjacent seawater without floating algal cover (three biological replicates). Algal samples were used for the measurement of algal physiological characteristics and the collection of epiphytic bacteria. Phycospheric seawater and control seawater samples were used for the measurement of environmental factors and collection of phycospheric seawater bacteria and control seawater bacteria (Fig. S1d).

Measurement of environmental factors.

Phycospheric and control seawater samples were collected with Niskin bottles and filtered through precombusted (460°C for 6 h) Whatman GF/F filters with 0.7-μm pores. The filtrates were collected using polyethylene bottles and stored at −20°C for further laboratory nutrient analysis. Nutrient concentrations were measured using continuous flow autoanalyzer systems (AAIII) (27, 28). The concentrations of NOx− (NO3− and NO2−) were determined using the cadmium-copper reduction method and standard pink azo dye method, respectively. The concentration of NH4+ was determined using the indophenol blue method, and that of DIP (PO43−-P) was determined using the molybdate blue method. DIN was calculated as the sum concentrations of NO3−, NO2−, and NH4+, whereas total dissolved nitrogen (TDN) and phosphorus (TDP) were determined through persulfate oxidation using the AutoAnalyzer 3 System. Subsequently, DON and DOP concentrations were calculated as the differences between TDN and DIN and between TDP and DIP, respectively. DOC was determined using a Multi N/C 3100 total nitrogen/total carbon analyzer (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany). Seawater temperature, salinity, pH, and dissolved oxygen were measured in situ using a YSI Professional Pro Meter (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Photosynthetically active radiation was measured in situ using a TES1335 Illuminance Meter (TES Electronic Inc., Taipei, China).

Measurement of algal physiological state.

The thalli were cleaned gently with sterile seawater and brushes. Next, algal thalli were checked for small grazers and epiphytes, which, if present, were carefully removed with a sterile scraper. To ensure that we were working with U. prolifera, we identified the floating algal samples by morphological identification based on the color, the condition of the base (holdfasts, etc.), and the outline (main axis and branching characteristics), and molecular identification based on 5S rDNA spacer sequences (Fig. S2). The parameters Fv/Fm (PSII maximum quantum yield), and Y(NPQ) (quantum yield of regulated non-photochemical energy loss) were measured to characterize algal photosynthetic activity and anti-light damage capability, respectively. SOD and NRA activity were measured to characterize the antioxidant activity and nitrate assimilation capacity of the algae, respectively. A Dual-PAM-100 Fluorometer (Walz, Berlin, Germany) was used to measure chlorophyll fluorescence. Before the experiments, the thalli were placed in the dark for 15 min. The settings of the Dual-PAM-100 Fluorometer were as described by Zhao et al. 2018 (25). Automated induction, recovery curve routine, and repetitive application of saturation pulses were used to obtain the chlorophyll fluorescence results. After the saturating pulse, the F0, Fm, and Y(NPQ) were determined. F0 is the minimal fluorescence after dark acclimation. Fm is the maximal fluorescence after saturation flashes in the dark-acclimatized sample. The parameter Fv/Fm was calculated using the equation Fv/Fm = (Fm − F0)/Fm, which represents the PSII maximum quantum yield in the thalli and can be used to evaluate photosynthetic activity in U. prolifera. The parameter Y(NPQ) represents the negative effects on U. prolifera from environmental stress. Thallus samples of 0.1 g fresh weight were ground in liquid nitrogen and then extracted with 1 mL of 0.05-mol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used to measure SOD and NRA activity. Measurements were performed using commercial kits following the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng, Nanjing, China).

Microbial sample collection and pretreatment.

For each phycospheric seawater bacterial sample, 3 L of phycospheric seawater was prefiltered through a polycarbonate filter with 3-μm pores, then phycospheric seawater bacteria were collected using a polycarbonate filter with 0.22-μm pores (filtration pressure < 0.04 MPa). The control seawater bacterial samples were treated and collected in the same manner as the phycospheric seawater bacterial sample. For each epiphytic bacterial sample, the thallus with 50 g fresh weight was rinsed three times in autoclaved artificial seawater and then co-vortexed with sterilized silica sand for three rounds at 150 rpm. The vortex suspension was composed of 50g U. prolifera, silica sand with grain sizes of 125 to 250 μm, and 300 mL sterilized seawater. After each round of vortexing for 15 min, the suspension was entirely renewed for the next round. All vortex suspensions produced over the three rounds were combined and pre-filtrated using mixed cellulose ester filter membranes with 3-μm pores to remove silica sand and other contamination. The epiphytic bacteria were then collected from the filtering liquid using a polycarbonate filter with 0.22-μm pores. All filters were stored at −20°C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene amplification, and high-throughput sequencing.