Abstract

We examined the ability of the koala biovar of Chlamydia pneumoniae to infect both Hep-2 cells and human monocytes and the effect of infection on the formation of foam cells. The koala biovar produced large inclusions in both human and koala monocytes and in Hep-2 cells. Koala C. pneumoniae induced foam cell formation with and without added low-density lipoprotein, in contrast to TW183, which produced increased foam cell formation only in the presence of low-density lipoprotein.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a major cause of respiratory disease (6, 7) and has recently been linked to cardiovascular disease (10, 12). At first C. pneumoniae was thought to be primarily a human pathogen. However, more recent evidence suggests that C. pneumoniae is able to infect a wide range of species, including horses (13), frogs (2), and koalas (5). Three biovars of C. pneumoniae are recognized: human, horse, and koala. While the epidemiology and genetic variability of the koala biovar of C. pneumoniae has been studied (4, 8, 14), remarkably little is know about its growth characteristics. We investigated the growth of the koala biovar of C. pneumoniae in human and koala blood monocyte-derived cultures and also the ability of this biovar to enhance the uptake of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by infected human monocytes to produce foam cells.

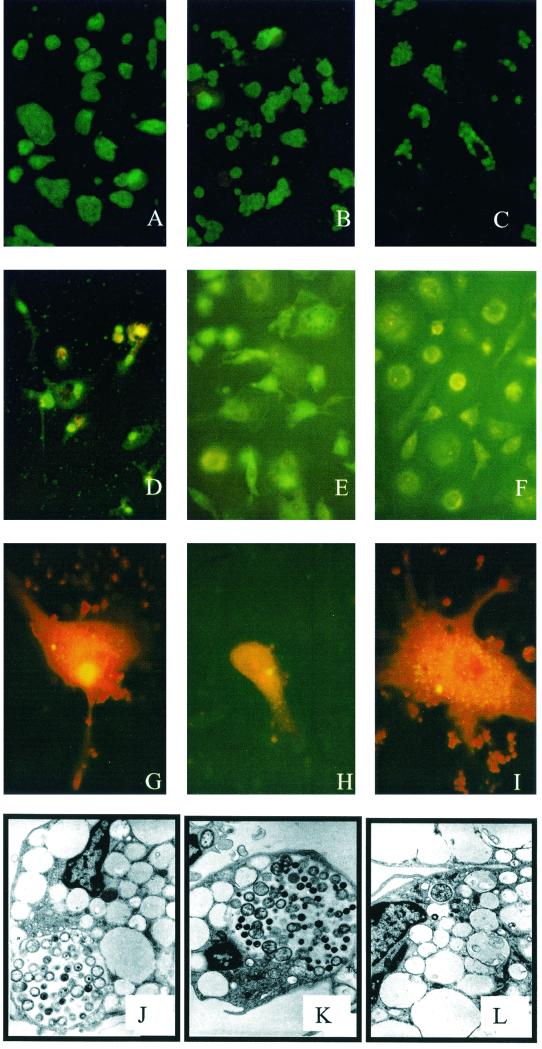

Two isolates of human C. pneumoniae were used: C. pneumoniae strain TW183 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (VR-2282); C. pneumoniae strain WA97001 is an Australian C. pneumoniae clinical isolate. The koala C. pneumoniae strain used was the LPCoLN isolate described by Wardrop et al. (14). Hep-2 cells were grown on coverslips in 24-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Bedford, Mass.) in minimal essential medium (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies, Auckland, New Zealand), HEPES (0.028 M), vancomycin (0.1 mg/ml), streptomycin (0.125 mg/ml), and Glutamax (0.4 mM; Gibco BRL). When confluent, the cells were infected with 4 × 105 inclusion-forming units (IFU) of chlamydia per ml in a solution containing minimal essential medium, 5% FCS, vancomycin, streptomycin, glucose (0.5%), NaCO3 (0.14%), Glutamax, and cycloheximide (0.2 mg/ml) and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g at 36°C for 1 h, after which the cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Chlamydia genus-specific monoclonal antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) at 8, 24, and 48 h postinfection (p.i.). Immunofluorescence staining showed that Hep-2 cells were permissive to infection with all three strains of C. pneumoniae. Of the two human strains, TW183 produced titers of 107 to 108 IFU/ml, compared with titers of 106 to 108 IFU/ml for strain WA97001. The koala isolate grew consistently better than either human isolate in Hep-2 cells, producing titers of 108 to 109 IFU/ml. The morphology of the inclusions varied markedly between isolates (Fig. 1A to C). Koala C. pneumoniae produced large inclusions, usually with a single inclusion per cell. The inclusions produced by TW183 were smaller, usually with multiple inclusions observed per cell. WA97001 produced the smallest inclusions, also with multiple inclusions present per cell.

FIG. 1.

(A to C) Hep-2 cells infected with C. pneumoniae. (A) KCpn (LPCoLN); (B) TW183; (C) WA97001. (D to F) Human monocytes stained with Chlamydia genus-specific monoclonal antibody and an FITC conjugate at 48 h p.i. (D) KCpn; (E) WA97001; (F) uninfected. (G to I) Koala monocytes stained with Chlamydia genus-specific monoclonal antibody and an FITC conjugate at 48 h p.i. (G) KCpn; (H) TW183; (I) WA97001. (J to L) TEM of human monocytes infected with C. pneumoniae. (J) KCpn at 24 h p.i.; (K) KCpn at 48 h p.i.; (L) TW183 at 24 h p.i.

Buffy coat cells were obtained from healthy blood donors via the Australian Red Cross Blood Service. Monocytes were isolated by magnetic separation with a monocyte negative isolation kit (Dynal, Melbourne, Australia) according to the kit instructions. Koala blood was obtained from healthy koalas at the Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary, and the monocytes were isolated by differential density centrifugation on Ficoll-Paque. The cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% FCS, HEPES, Glutamax, vancomycin, and streptomycin; plated onto glass coverslips of 24-well plates at a density of 4 × 105 cells per well; and incubated for 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. These 5-day-old monocytes were infected with 4 × 105 IFU of human C. pneumoniae per well and 6 × 104 IFU of koala C. pneumoniae per well in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 60 min at 36°C. Following centrifugation, the plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and then fixed with methanol and stained at 8, 24, and 48 h p.i. For fluorescence staining, the cells were fixed in methanol and incubated with an in-house Chlamydia genus-specific monoclonal antibody for 1 h and then with an anti-mouse FITC conjugate (Silenus, Melbourne, Australia) for a further hour. Inclusions were viewed under blue light on a fluorescence microscope. For electron microscopy (EM), the monocytes were gently scraped from the wells using a Pasteur pipette and pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant was removed, and glutaraldehyde was added. The fixed cells were then processed for transmission EM (TEM) by standard procedures. The human monocytes were largely resistant to the development of productive inclusions when they were infected with either of the human C. pneumoniae isolates (TW183 or WA97001), with less than 1% of the cells developing visible inclusions. The infected cells formed a few small inclusions at 48 p.i. with both TW183 and WA97001 (Fig. 1E shows WA97001). These inclusions did not progress to form large inclusions, and there was no evidence of host cell lysis by 10 days p.i. Similar observations of restricted growth in human monocytes by human C. pneumoniae have been reported elsewhere (1, 3). In contrast, koala C. pneumoniae infection resulted in the formation of large inclusions by 48 h p.i. (Fig. 1D). The level of cells infected by the koala strain was also much higher (approaching 100%), even though the infecting dose used for the koala strain was less than that used for the human strains. In koala monocytes, koala C. pneumoniae produced larger inclusions than those produced by either human isolate (Fig. 1G, H, and I). Once again, more inclusions were evident in the cells infected with koala C. pneumoniae than in cells infected with either human isolate. When analyzed by EM, inclusions were difficult to find in the human monocytes infected with human C. pneumoniae. Figure 1L illustrates one of the few inclusions observed and shows a single chlamydial particle within the inclusion. At 48 h p.i., we did not observe any particles resembling reticulate bodies or elementary bodies within inclusions in these cells. Inclusions were abundant and easy to find in the koala C. pneumoniae-infected monocyte samples. At 24 h p.i. (Fig. 1J), the majority of particles seen were reticulate bodies or intermediate forms, while by 48 h p.i., a number of elementary bodies were evident (Fig. 1K).

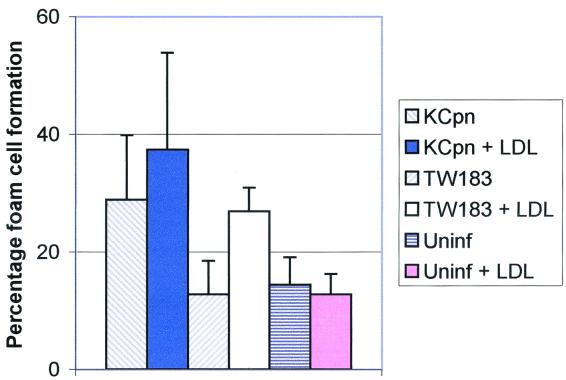

For the foam cell experiments, human LDL was isolated from the plasma of normal volunteers by density gradient ultracentrifugation, similar to methods described elsewhere (11), with the serum density adjusted to 1.07 kg/liter with NaCl and with the samples being centrifuged at 205,000 × g for 24 h at 20°C. The isolated LDL was passed through a PD-10 ion-exchange column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) twice to remove EDTA prior to use in the foam cell experiments. The concentrations of cholesterol and triglycerides in the extract were determined by analysis on a Hitachi 917 automatic analyzer. The LDL was stored in the dark at 4°C for a maximum of 2 weeks. At day 4 after isolation, the medium containing normal FCS was removed from the monocyte monolayers, replaced with RPMI 1640 containing 10% lipid-depleted FCS (LDFCS; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and incubated for a further 24 h. The macrophages were then infected with 4 × 105 IFU of C. pneumoniae TW183 per well or 6 × 104 IFU of koala C. pneumoniae per well in RPMI 1640 plus 10% LDFCS and centrifuged at 800 × g for 60 min. Following centrifugation, 100 μg of LDL per ml was added to the wells in RPMI 1640–10% LDFCS. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Wells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline to remove excess LDL. Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, followed by incubation with 1% (wt/vol) Oil-Red-O (Sigma) in 60% isopropanol for 30 min. The wells were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline and counterstained with hematoxylin, and the coverslips with the adherent cells were removed with tweezers and mounted on glass slides in 10% glycerol. The slides were examined under a light microscope, and percentages of foam cell formation were determined. Foam cells were defined as cells with ≥10 Oil-Red-O-positive droplets. Figure 2 shows that cultures in which the cells were infected with koala C. pneumoniae and treated with LDL produced significantly higher levels of foam cells than cells treated with LDL alone (P < 0.05). Significantly higher levels of foam cell formation were also observed in cultures treated with LDL and infected with TW183 (P < 0.01) than in cells treated with LDL alone. However, koala C. pneumoniae also significantly enhanced foam cell formation compared to that of uninfected cells in the absence of LDL (P < 0.01) while TW183 did not. Addition of LDL made no difference to the percentage of foam cell formation in cells infected with koala C. pneumoniae, although there were significantly higher levels of foam cells when cells infected with TW183 were treated with LDL than when cells were not treated (P < 0.01).

FIG. 2.

Foam cell formation by monocytes/macrophages infected with C. pneumoniae koala strain KCpn (LPCoLN) and TW183 in the presence or absence of LDL. Results are reported as mean percentages and standard deviations from triplicate experiments. Uninf, uninfected.

The results of our foam cell experiments support our morphological observations that koala and human C. pneumoniae strains are biologically quite different. Our results are similar to those of Kalayoglu and Byrne (9), who used the human strain TW183; in their study, foam cell formation was induced in infected cells in the presence of LDL but was not induced in cells that were infected with TW183 alone (9). However, we also found that lipid uptake could be induced in the absence of LDL when the macrophages were infected with the koala biovar of C. pneumoniae. It appears that infected cells can take lipids other than LDL, possibly triglycerides, from the cell culture medium, since Oil-Red-O cells can be seen in the absence of lipoprotein. Our results indicate that there is an LDL-independent mechanism of lipid uptake that is induced in response to infection with koala C. pneumoniae. Our results also show that foam cell formation in response to TW183 does not require productive infection of the monocytes. TW183 was able to induce foam cell formation yet produced only a few, small inclusions in infected cells.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Princess Margaret Hospital for Children for supplying the nasopharyngeal aspirate which yielded strain WA97001. We also thank the staff of the Division of Microbiology at the Pathcentre, Nedlands, Perth, Western Australia, for assistance with the culture of that strain. The Electron Microscopy Unit of the Department of Pathology at the University of Western Australia is thanked for performing the EM experiments. Thanks also go to David Rees at the Heart Research Institute, Sydney, Australia, for help with the foam cell model and Kevin Croft at the University Department of Medicine, the University of Western Australia, for assistance with LDL isolations.

This work was supported by the Australian Koala Foundation, the Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary, and the QUT Grants Scheme.

REFERENCES

- 1.Airenne S, Surcel H M, Alakärppä H, Laitinen K, Paavonen J, Saikku P, Laurila A. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1445–1449. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1445-1449.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger L, Volp K, Mathews S, Speare R, Timms P. Chlamydia pneumoniae in a free-ranging giant barred frog (Mixophyes iteratus) from Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2378–2380. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2378-2380.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaydos C A, Summersgill J T, Sahney N N, Ramirez J A, Quinn T C. Replication of Chlamydia pneumoniae in vitro in human macrophages, endothelial cells, and aortic artery smooth muscle cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1614–1620. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1614-1620.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girjes A, Hugall A, Timms P, Lavin M. Two distinct forms of Chlamydia psittaci associated with disease and infertility in Phascolarctos cinereus (koala) Infect Immun. 1988;56:1897–1900. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1897-1900.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glassick T, Giffard P, Timms P. Outer membrane protein 2 gene sequences indicate that Chlamydia pneumoniae causes infections in koalas. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grayston J T, Kuo C C, Wang S P. Chlamydia pneumoniae sp. nov. for Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grayston J T, Wang S P, Kuo C C, Campbell L A. Current knowledge on Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain TWAR, an important cause of pneumonia and other acute respiratory diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:191–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01965260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson M, White N, Giffard P, Timms P. Epizootiology of Chlamydia infections in two free-range koala populations. Vet Microbiol. 1999;65:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalayoglu M V, Byrne G I. Induction of macrophage foam cell formation by Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:725–729. doi: 10.1086/514241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo C C, Grayston J T, Campbell L A, Goo Y A, Wissler R W, Benditt E P. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) in coronary arteries of young adults (15–34 years old) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6911–6914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redgrave T G, Roberts D C, West C E. Separation of plasma lipoproteins by density-gradient ultracentrifugation. Anal Biochem. 1975;65:42–49. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Ekman M R, Nieminen M S, Mäkelä P H, Huttunen J K, Valtonen V. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;ii:983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storey C, Lusher M, Yates P, Richmond S. Evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae of non-human origin. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2621–2626. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardrop S, Fowler A, O'Callaghan P, Giffard P, Timms P. Characterization of the koala biovar of Chlamydia pneumoniae at four gene loci—ompAVD4, ompB, 16S rRNA, groESL spacer region. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1999;22:22–27. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]