Abstract

Latinx (includes Hispanics and is the non-gendered term for Latino/Latina which is a person of Latin American origin or descent) constitutes the largest racial and ethnic minority group in the United States (US). Many members of this group report limited English proficiency, experience discrimination, feel distrust in the healthcare setting, and face poorer health outcomes than non-Latinx Whites. As healthcare systems assess internal structures of care, understanding the experiences of Latinx patients may inform strategies to improve care. This narrative review describes studies that assessed the experiences of Latinx patients with limited English proficiency (LEP) in the inpatient and outpatient settings in the US. We searched PubMed for studies published between January 1, 1990, and March 2021. We reviewed all citations and available abstracts (n = 429). We classified study titles (n = 156) as warranting detailed consideration of the original article. Limited English proficiency is a well-documented challenge reported by Latinx patients seeking care in the outpatient setting, resulting in mistrust of healthcare organizations and clinicians. The effects of LEP overlap substantially with challenges related to patients’ immigration status, cultural traditions, and socioeconomic needs. Use of professional interpretation rather than ad hoc interpretation improves trust and satisfaction. There is no consensus about the most effective mode of delivering professional interpretation (in person, telephonic, video conferencing), although rapid simultaneous telephone translation is a promising modality. Increasing awareness of the barriers to effective communication, improving skills in communicating through translators, and increasing the amount of time spent with patients may improve communication and trust more than structural changes like mode of translation or bedside rounding. Cultural fluency training, standardized language training for providers, and incentive pay for fluency are also deserving of further consideration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07995-3.

KEY WORDS: Latinx, healthcare disparities, Spanish speaking, barriers to healthcare , culturally responsive care , limited English proficiency, medical interpretation

INTRODUCTION

Concerns about widening health disparities in the United States (US) based on race and ethnicity have re-ignited an assessment of the systemic barriers to high-quality care in our healthcare system. Evaluations of patient satisfaction and mistrust demonstrate that Latinx (includes Hispanics and is the non-gendered term for Latino/Latina which is a person of Latin American origin or descent) patients are more likely to report mistrust of healthcare providers and are less satisfied with the care they receive than non-Latinx Whites.1 Understanding the causes and consequences of mistrust and dissatisfaction is important because Latinx are the largest ethnic minority group in the country and constitute 18.5% of US residents, while nearly 13% report undocumented immigration status and almost one third report limited English proficiency (LEP).2,3 Latinx patients who report LEP experience mistrust and dissatisfaction with the healthcare in the US for several reasons. The objective of this narrative review is to summarize the perspectives of Latinx patients with LEP, along with factors tightly linked to LEP such as immigration status, to inform strategies that address systemic barriers to high-quality care.

Several studies have evaluated the experience of Latinx patients with LEP and how it influences health outcomes. A survey that assessed satisfaction among Latinx patients with LEP and kidney disease reported an association between poor patient clinic satisfaction and increased risk of hospitalization which could not otherwise be explained by medication non-adherence, hemoglobin A1c, or blood pressure.4 Poor patient satisfaction can also affect patients’ access to care. Interviews with patients with LEP demonstrated that compared to patients with high satisfaction, those with low satisfaction were less likely to return to the emergency department for care.5 This finding of delaying care is consistent with another study demonstrating that compared to non-Latinx White patients, Latinx patients are more likely to present with more advanced cancer.6 Dissatisfaction with healthcare increases risk of hospitalization, limits access to care and may also drive mistrust in the healthcare system among patients with LEP.

Many studies have evaluated how mistrust of healthcare among Latinx patients influences their interaction with healthcare. Latinx patient mistrust of the healthcare system is common and has been well documented, especially among the Latinx population with LEP.7–9 Interviews with Latinx patients demonstrate an association between medical mistrust, patient satisfaction, and perceived discrimination.10 Mistrust has been associated with reduced cancer screening rates among Latinx patients.11,12

Latinx patients with LEP are likely dissatisfied and mistrustful of US healthcare for many reasons. The objective of this narrative review is to summarize the perspectives of both recent-immigrant and US-born Latinx patients with LEP regarding healthcare received in the US. Understanding these perspectives may inform strategies that address systemic barriers to high-quality care. The term Hispanic and Latinx have both been cited throughout literature which evaluate barriers to care for Spanish-speaking patients with LEP. Though these terms are distinct, both are used throughout this review.

METHODS

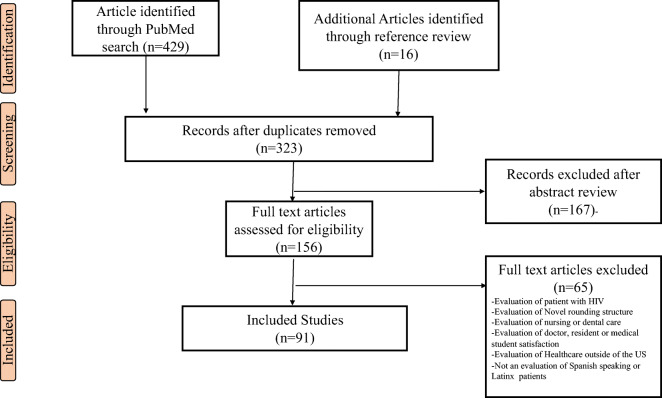

A single author (LE) searched PubMed for studies published between 1990 and March 2021 using several keywords and search term combinations listed in Table 1. The key term search yielded 429 publications and 323 were available after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). A single author (LE) reviewed all citations and available abstracts (n = 323). A single author (LE) classified study titles and abstracts as not relevant (n = 167) or warranting detailed consideration of the original article (n = 156). A second author (EH) reviewed all included articles (n = 91) to ensure that each met both inclusion and exclusion criteria. We did not include studies that addressed the following: (1) patients with diagnosis of HIV; (2) satisfaction with nursing care or nursing rounds; (3) novel bedside rounding structures that did not include LEP patients; (4) evaluations of attending, resident, or medical student satisfaction; (5) evaluation of or satisfaction with dental care; and (6) healthcare outside of the United States, as well as studies that (7) did not address LEP or Latinx patients. We included in this narrative review publications which were evaluations or comparisons of healthcare provided to LEP or Latinx patients, studies which describe challenges faced by this population, studies that describe patient experience surrounding bedside rounds, studies that evaluate language concordance among these patients and factors which influence patient trust.

Table 1.

Search Term Combinations

| Iteration | Term 1 | Term 2 | Term 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Latino | Medical Mistrust | |

| 2 | Latinx | Medical Mistrust | |

| 3 | Latino | Mistrust | |

| 4 | Latinx | Mistrust | |

| 5 | Latino | Trust | |

| 6 | Latinx | Trust | |

| 7 | Hispanic | Medical Mistrust | |

| 8 | Bedside Rounds | Patient Satisfaction | |

| 9 | Bedside Rounds | Limited English Proficiency | |

| 10 | Bedside Rounds | Spanish | |

| 11 | Bedside Rounds | Language Interpertation | |

| 12 | Satisfaction | Language Interpertation | Latino |

| 13 | Satisfaction | Language Interpertation | Latinx |

| 14 | Languageg Concordance | Mistrust | |

| 15 | Languageg Concordance | Satisfaction |

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search.

RESULTS

Latinx Patient Challenges

Limited English Proficiency (LEP)

The most frequently cited challenge faced by the Latinx patient population is LEP. A 2013 survey found that 25.1 million Americans report limited English proficiency.13 Latinx patients with LEP face many challenges navigating a healthcare system which was originally structured for English-speaking patients. Among 1344 patients who were surveyed in a public health department clinic, 25% of patients with LEP reported difficulty scheduling appointments, and 29% of Spanish-speaking patients, compared to 10% of English-speaking patients, did not report resolution of medical conditions after a doctor’s appointment (P < 0.001).14 Interviews with 20 Latinx patients with LEP identified 3 similar themes which contributed to inferior care: misidentifying the patient in records, lack of Spanish language services, and perceived discrimination.15 A study of Latinx patients in North Carolina demonstrated a trend of patients seeking care from not only language-concordant clinicians but also ethnically concordant clinicians.16

In addition, Latinx patients face many challenges communicating with doctors and advanced practice providers. Interviews with 2921 foreign-born Latinx patients found that language discordance was the best predictor of confusion, frustration, and perception of poor care.17 Semi-structured qualitative interviews with Latinx caregivers demonstrated many concerning trends; caregivers commonly experienced emotional stress when communicating with clinicians, and patients commonly experienced communication without professional interpretation.18 Patient-clinician communication challenges have been well described among Latina women. Interviews and medical mistrust measure of 220 Dominican women living in New York found that communication difficulty was predictive of dissatisfaction; when women communicated with a language-concordant clinician, they reported less difficulty.19 Finally, in a study of 116 Latinx patients, clinicians with higher self-ratings of Spanish language proficiency and cultural competency were reported to be more responsive to patients and better able to elicit patient concerns, explain health conditions, and empower patients.20

Several studies have analyzed communication between Spanish-speaking patients and clinicians in order to better understand patients’ difficulties. An analysis of 38 outpatient clinic conversations between Spanish- or English-speaking patients and their clinicians found that compared with English-speaking patients, Spanish-speaking patients were less likely to mention symptoms (n = 4.1 vs 6.3, P = 0.05), feelings (n = 0.2 vs 1.2, P = 0.05), expectations (n = 0 vs 0.8, P = 0.01), and thoughts (n = 0.9 vs 2.7, P = 0.01), with a thought considered to be an idea about an illness like “I think I got this cold from standing in the rain.” In addition, Spanish-speaking patients were less likely to have comments facilitated (for example, “Do you think your dry cough is related to smoking?”) and more likely to have comments dismissed by clinicians (“A dry cough is normal for people who smoke”).21 In addition, patients have reported low satisfaction with ad hoc interpretation, which includes all interpretation that is not professional interpretation (i.e., using friends, family members, medical assistants, or medical students who speak Spanish but are not certified to interpret).22–26 Medical interpretation from a certified interpreter is also, at times, imperfect; an analysis of interpretation error rates among different forms of interpretation has found that inaccurate interpretation was twice as likely with ad hoc interpretation compared to video or in-person interpretation.27

The communication challenges between patients and providers have an impact on medication adherence and disease outcomes. A retrospective analysis of insulin and oral medication adherence among patients with diabetes compared pharmacy dispensary records of 3205 Latinx LEP patients, 5755 English-speaking Latinx patients, and 21,878 English-speaking non-Latinx White patients. This study demonstrated that LEP is associated with lower oral diabetic medication and insulin adherence.28 A subsequent study of 1605 Latinx patients with LEP and diabetes demonstrated that when LEP patients transition from a language-discordant provider to a language-concordant provider, they achieve improved glycemic and lipid control, compared to patients who transition to a second language-discordant provider.29 A survey of women on a post-partum ward found patients who used interpretation had better pain control, more timely pain treatment, and better perceived provider helpfulness.30

Several novel studies have been conducted among pediatric populations which provide further context to the barriers in communication between Latinx patients with LEP and clinicians. Among 570 parents of pediatric Medicaid patients who needed language interpretation, Spanish-speaking patients in need of medical interpretation reported that clinicians did not spend enough time with their children compared to English-speaking patients (OR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.17–0.68).31 A separate study of 475 pediatric patients receiving care in an emergency department found that compared to English-speaking patients, Spanish-speaking patients had lower rates of hospital admission (9.09% and 0.93%) and lower rates of interventions including CT scans, laboratory studies, IV and nebulized medication, and X rays) (42.34% and 5.35%).9

Immigration Status

Apart from patient and provider communication difficulty, many Latinx patients are undocumented and immigration status is often overlooked by providers. Interviews with Latina women who had an abnormal mammogram described emotional stress from this diagnosis which was compounded by financial stressors due to the inability to work legally.32 In addition, interviews with 26 recently immigrated South American children and adolescents found that these patients often experience difficulty establishing a relationship with a medical provider, in part because clinicians do not understand these patient’s past experiences. They also report distrust of authority figures and are frustrated because language interpretation is often not enough to solve communication barriers.33 Finally, undocumented immigrants are often targeted for deportation, and the anxiety created by the fear of deportation impacts their mental health. A survey of 218 undocumented Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander young adults reported that compared to individuals without Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival status (DACA), those with DACA status were less likely to report gaps in healthcare or depressive symptoms.34

The dissatisfaction and mistrust created by a patient’s immigration status impact disease management and outcomes. Interviews with 60 Latinx patients who had recently survived hospitalization for COVID-19 infection found that Latinx patients were fearful to seek medical care due to discrimination. Patients in this study described a lack of safeguards to protect themselves from COVID-19 infection and fear of deportation should they present for hospital care.35 In addition, undocumented Latinx patients with kidney failure who were interviewed before they transitioned from inpatient emergency dialysis to outpatient scheduled dialysis described fear of discrimination because they are undocumented and because of their LEP.36 A similar theme was reported from interviews with 20 Latinx patients with kidney failure who relied on emergency hemodialysis. These patients were aware that they were receiving inferior care based on immigration status.36

Patients who are undocumented are also less likely to have health insurance or be eligible for benefits. In a recent survey completed by 294 palliative care physicians, 68% endorsed that limited or no hospice options exist for undocumented immigrant patients.37 Another 2007 survey showed that undocumented status was associated with lower likelihood of a blood pressure check in the preceding 2 years, lower likelihood of cholesterol check in the past 5 years, and lower likelihood of receiving healthcare information from a doctor.38

Cultural Traditions

Differences between US and Latinx cultural traditions impact Latinx patient experience with US healthcare. Several publications have evaluated the intersection of machismo—which represents the strict gender role a man is expected to play in Latinx society,39 familismo—which is the multidimensional construct representing the connection and commitment to family,39 perceived discrimination, and degree of acculturation with healthcare experience in the United States. An association between machismo values, perceived discrimination, and medical mistrust was identified in interviews with 499 Latinx patients in rural Oregon.39 Separate studies have demonstrated that machismo culture influences Latinx healthcare in other ways. Interviews with 480 sexually active Latinx patients evaluated the role of individual, interpersonal, and structural power as a predictor of condom use. The study found that male interpersonal power or the ability to influence another to achieve a desired end was negatively associated with condom use.40

Decisions made by Latina women are often influenced by cultural traditions. Interviews with 38 Black and Latina women found that these women often feel implicit pressure from clinicians to begin contraception and will agree to forms of contraception in order to end conversations.41 A narrative review of surgical treatment of obesity in Latinx and African American patients found that Latinx patients are less likely to undergo bariatric surgery, which was attributed to limited access to care, less frequent financial/insurance coverage, increased medical mistrust, lower referral rates by PCP, and different cultural beliefs surrounding weight loss.42 These cultural beliefs include the perception that being overweight is less common among Latina women than White women. Latina women were shown to be less interested in weight loss for the purpose of changing body shape and more interested in improving energy levels and reducing unwanted hair growth.42

Finally, several studies have found that Spanish-speaking patients often express fatalistic statements which have been associated with medical mistrust. Interviews with racial and ethnic minority patients recently diagnosed with lung cancer found that racial and ethnic minority patients with late-stage presentations were more likely to agree with fatalistic statements such as “if bad things happen, they are meant to be” and statements like “my ethnic group cannot trust doctors” or “my ethnic group should not confide in doctors or healthcare workers because it will be used against them.” 6 Surveys of 268 diverse men who were recently diagnosed with prostate cancer found that Latinos were more likely to express cancer fatalism and medical mistrust compared to non-Latino White men.43 Compared to non-Latino White men, Latino men demonstrated more medical mistrust and cancer fatalism.43

Social Needs and Faith

Latinx patients have unique social needs which influence trust and perceptions of care. In interviews with Latinx patients living in a rural community, individuals reported that hypertension management is often limited by competing family priorities (e.g., needing to put family first), feeling of loyalty to family regarding unhealthy eating habits, and reduced physical activity.44 In addition, surveys of Dominican women demonstrated that downward social mobility was associated with reduced healthcare satisfaction and medical mistrust.45 In another study that analyzed 2242 Latinx patients using the 2007–2009 Medical Expenditure Panel survey, Latinx patients who were English proficient were more likely to have health insurance and a high school education and feel satisfied with their doctor’s communication.46 Faith is also very important for Latinx communities. In a survey of 767 Latinx church goers, adults who participated in church groups/ministries or had a parent who was an immigrant to the United States demonstrated more medical mistrust compared to Latinx church goers who did not participate in church groups/ministry activities.47

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have revealed structural aspects of the American healthcare system which create challenges for Latinx patients.35,37,38,48 Clinicians and healthcare systems need to change practice patterns that negatively affect Latinx patient trust and satisfaction.26,49 Many of these changes focus on improving communication and time spent with patients in clinics. Many of the communication techniques commonly used by hospitals have not been evaluated and cannot be addressed here. The items described are a starting point to inform healthcare strategies and research to improve communication and care for the Latinx population.

Use of Interpretation

A survey of 48 hospitals in the midwestern United States found that not all hospitals had patient materials translated into Spanish, professional interpreters, or means to validate the interpretation provided by family members, staff, or clinicians.48 Bilingual clinicians should be used when available.49 If bilingual clinicians are unavailable, in-person professional interpretation should be used.22,25,26,50,51 Video interpretation is preferred over telephone interpretation.26,52 A survey of patients with LEP who were admitted to two San Francisco hospitals found that interpreter use was 60% among physicians and 37% among nursing staff.53 The mode of delivering interpretation has been evaluated both in randomized and observational studies; the most effective mode is not clear.26,51 Two studies50,52 evaluated the use of rapid simultaneous telephone translation, in which the interpreter translates while the patient or provider is speaking. One study50 compared rapid simultaneous translation with usual translation using either professional or ad hoc translators, and found better patient ratings of communication with simultaneous translation. Another study52 reported there were fewer inaccuracies with and greater preference for simultaneous translation. Whether or not communication and trust would be improved by specific awareness or skill training for use of interpreters remains uninvestigated. Finally, professional interpretation should be used for all aspects of patient care including disposition conversations.25,30,54 Communication through interpreters appears to result in interactions that are less open-ended, and contains fewer topics or questions introduced by patients.21 Whether or not communication and trust would be improved by specific awareness or skill training for use of interpreters remains uninvestigated.

Cultural Fluency Training

Bilingual clinicians and in-person interpretation are not enough to provide equivalent care for Latinx patients.20 Medical education and workplace education in both linguistic and cultural fluency should be provided to all staff caring for Latinx patients.20,55–58

Standardization of Education and Fluency Evaluations

To our knowledge, there is no standard Spanish medical education for clinicians and no standard evaluation exists for clinicians to demonstrate Spanish language fluency.49,59,60 In order for patient concerns to be understood and met, standardization must be developed in order to ensure that patients with LEP receive the same quality of care as English-proficient patients.

Scheduling and Staffing Change

Several studies have shown that patients with LEP report that they do not have enough time with clinicians.21,31 Scheduling changes should be incorporated for LEP patients to allow for a longer visit. In addition, studies have also demonstrated and proposed the benefit of bilingual staff which can improve patient satisfaction outside of the exam room.15,21,25,61

Incentive Pay for Fluency

Evaluations of fluency and language education of clinicians and staff can be a burden on already busy staff; incentive pay for proficiency has been a proposed intervention.59 The applicability of this intervention is likely to be limited because Latinx patients are more likely to be cared for in resource-limited safety-net hospitals and community health centers.

CONCLUSION

The availability of language-concordant care for individuals with limited English proficiency (LEP) is a well-documented challenge for Latinx patients. When language interpretation is assessed, it is clear that bilingual clinicians or professional, in-person, interpreters are preferred and reduce errors.22,25,26,49–51

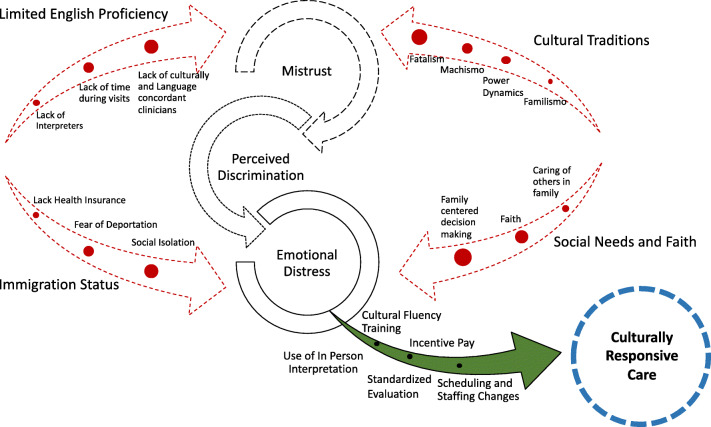

Low healthcare satisfaction and medical mistrust have been well demonstrated in the Latinx community.7,8,10,12,62,63 (Fig. 2). These challenges lead to later hospital presentation, low healthcare utilization, and poor outcomes.4,11,29,42,64,65 The US healthcare system finds itself in an unfortunate cycle with some of its most socially marginalized patients. Additional research is needed; however, it may be challenging to conduct research on the Latinx community given reports of mistrust of medical researchers.66 Some groups report success in research with the Latinx community when using community-based participatory research, direct outreach, and community-partnered interventions.1,67

Figure 2.

Factors contributing to mistrust and strategies to provide culturally responsive care.

There is more research on communication strategies in the outpatient and pediatric setting, and data in the hospitalized adult setting is limited.68–70 To our knowledge, no evaluation of communication with hospitalized adult patients with LEP has been performed, though a few studies have evaluated strategies with hospitalized pediatric LEP patients.67,71 Future research should include an evaluation of communication strategies with hospitalized adult patients.

The challenges faced by the Latinx community should motivate us to identify evidence-based and culturally responsive strategies to provide high-quality care and communication. It is important to understand not only why satisfaction and trust are low among the Latinx but also the mechanisms that contribute to poor outcomes and healthcare utilization. This process begins with further research in partnership with the Latinx community that is translated to upstream structural change in US hospitals.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 110 kb)

Acknowledgements

This publication has no contributors, funding, or presentations to report.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough D, Hanratty R, Price DW, Katz HE, Wright LA, Bronsert M, Karimkhani E, Magid DJ, Havranek EP. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias predicts patients’ perceptions of care among black but not Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013; 11: 43-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.United States Census Bureau. United States Census Quick Facts. United States Department of Commerce. 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI725219. Accessed April, 2021

- 3.United States Census Bureau. 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.htm. Accessed April, 2021

- 4.Cedillo-Couvert EA, Hsu JY, Ricardo AC, et al. Patient Experience with primary care physician and risk for hospitalization in hispanics with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 13(11):1659–1667. 10.2215/CJN.03170318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Carrasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, et al. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;14(2):82–87. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bergamo C, Lin JJ, Smith C, et al. Evaluating beliefs associated with late-stage lung cancer presentation in minorities. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(1): 12–18. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182762ce4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Smirnoff M, Wilets I, Ragin DF, et al. A paradigm for understanding trust and mistrust in medical research: The Community VOICES study. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2018;9(1):39–47. 10.1080/23294515.2018.1432718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sewell AA. Disaggregating ethnoracial disparities in physician trust. Soc Sci Res. 2015; 54, 1–20. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fields A, Abraham M, Gaughan J, et al. Language matters: race, trust, and outcomes in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016; 32(4): 222–226. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.López-Cevallos DF, Harvey SM, Warren JT. Medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and satisfaction with health care among young-adult rural Latinos: satisfaction with care among rural Latinos. J Rural Health. 2014; 30(4):344–351. 10.1111/jrh.12063. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gupta S, Brenner AT, Ratanawongsa N, Inadomi JM. Patient trust in physician influences colorectal cancer screening in low-income patients. Am J Prev Med. 2014; 47(4):417–423. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Davis JL, Bynum SA, Katz RV, et al. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012; 23(4a):67–76. 10.1353/hpu.2012.0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Pandya C, McHugh M, Batalova J. American Community Surveys. United States Census Bureau. 2011. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/limited-english-proficient-individuals-united-states-number-share-growth-and-linguistic. Accessed April, 2021

- 14.Welty E, Yeager VA, Ouimet C, et al. Patient satisfaction among Spanish-Speaking patients in a public health setting. J Healthcare Qual. 2012; 34(5):31–38. 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Calo WA, Cubillos L, Breen J, et al. Experiences of Latinos with limited English proficiency with patient registration systems and their interactions with clinic front office staff: An exploratory study to inform community-based translational research in North Carolina. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015; 15(1):570. 10.1186/s12913-015-1235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Murray-García JL, García JA, Schembri ME, et al. The service patterns of a racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse housestaff: Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1232–1240. 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Tarraf W. Health care quality perceptions among foreign-born Latinos and the importance of speaking the same language. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010; 23(6): 745–752. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.090264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Riera A, Ocasio A, Tiyyagura G. et al. Latino Caregiver Experiences With Asthma Health Communication. Qual Health Res. 2015; 25(1):16–26. 10.1177/1049732314549474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Abraído-Lanza AF, Céspedes A, Daya S, et al. Satisfaction with Health Care among Latinas. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011; 22(2):491–505. 10.1353/hpu.2011.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Grumbach K, et al. An exploratory study of communication with Spanish-speaking patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19:167-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Rivadeneyra R, Elderkin-Thompson V, Silver RC, et al. Patient centeredness in medical encounters requiring an interpreter. Am J Med. 2000;108(6):470-4. 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lee LJ, Batal HA, Maselli JH, et al. Effect of Spanish interpretation method on patient satisfaction in an urban walk-in clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2002; 17(8): 641–646. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Moreno G, Morales LS Hablamos Juntos (Together We Speak): interpreters, provider communication, and satisfaction with care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010; 25(12): 1282–1288. 10.1007/s11606-010-1467-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Crossman KL, Wiener E, Roosevelt G, et al. Interpreters: telephonic, in-person interpretation and bilingual providers. PEDIATRICS. 2010; 125(3): e631–e638. 10.1542/peds.2009-0769. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Flower KB, Skinner AC, Yin HS, et al. Satisfaction with communication in primary care for Spanish-Speaking and English-Speaking parents. Acad Pediatr. 2017; 17(4): 416–423. 10.1016/j.acap.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Boylen S, Cherian S, Gill FJ, et al. Impact of professional interpreters on outcomes for hospitalized children from migrant and refugee families with limited English proficiency: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020; 18(7): 1360–1388. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Karliner LS, et al. Inaccurate language interpretation and its clinical significance in the medical encounters of Spanish-speaking Latinos. Med Care. 2015; 53(11): 940–947. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Fernández A, Quan J, Moffet H, et al. Adherence to newly prescribed diabetes medications among insured Latino and White Patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177(3): 371. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Parker MM, Fernández A, Moffet HH, et al. Association of patient-physician language concordance and glycemic control for limited–English proficiency Latinos with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 177(3): 380. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Jimenez N, Moreno G, Leng M, et al. Patient-reported quality of pain treatment and use of interpreters in Spanish-Speaking patients hospitalized for obstetric and gynecological care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012; 27(12): 1602–1608. 10.1007/s11606-012-2154-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Mosen DM, Carlson MJ, Morales LS, et al. Satisfaction with provider communication among Spanish-Speaking medicaid enrollees. Ambul Pediatr. 2004; 4(6): 500–504. 10.1367/A04-019R1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Shelton RC, Goldman RE, Emmons KM, et al. An investigation into the social context of low-income, Urban Black and Latina Women: implications for adherence to recommended health behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2011; 38(5): 471–481. 10.1177/1090198110382502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lightfoot AF, Thatcher K, Simán FM, et al. “What I wish my doctor knew about my life”: using photovoice with immigrant Latino adolescents to explore barriers to healthcare. Qual Soc Work. 2019; 18(1):60–80. 10.1177/1473325017704034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Sudhinaraset M, Ling I, Gao L, et al. The association between deferred action for childhood arrivals, health access, and mental health: the role of discrimination, medical mistrust, and stigma. Ethn Health. 2020;1–13. 10.1080/13557858.2020.1850647. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Cervantes L, Martin M, Frank MG, et al. Experiences of Latinx individuals hospitalized for COVID-19: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210684. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Cervantes L, Fischer S, Berlinger N, et al. The Illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Gray NA, Boucher NA, Cervantes L, et al. Hospice access and scope of services for undocumented immigrants: a clinician survey. J Palliat Med. 2020. jpm.2020.0547. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Rodríguez MA, Vargas Bustamante A, Ang A Perceived quality of care, receipt of preventive care, and usual source of health care among undocumented and other Latinos. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(S3):508. 10.1007/s11606-009-1098-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Oakley LP, López-Cevallos D F, Harvey SM The association of cultural and structural factors with perceived medical mistrust among young adult Latinos in Rural Oregon. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):118–127. 10.1080/08964289.2019.1590799. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Stokes LR, Harvey SM, Warren JT Individual, interpersonal, and structural power: associations with condom use in a sample of young adult Latinos. Health Care Women Int. 2016;37(2):216–236. 10.1080/07399332.2015.1038345. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Gomez AM, Wapman M Under (implicit) pressure: Young Black and Latina women’s perceptions of contraceptive care. Contraception. 2017;96(4):221–226. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Smith ED, Layden BT, Hassan C, et al. Surgical treatment of obesity in Latinos and African Americans: future directions and recommendations to reduce disparities in bariatric surgery. Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care. 2018;13(1):2–11. 10.1089/bari.2017.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Bustillo NE, McGinty HL, Dahn JR, et al. Fatalism, medical mistrust, and pretreatment health-related quality of life in ethnically diverse prostate cancer patients: Fatalism, medical mistrust, and HRQoL. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(3):323–329. 10.1002/pon.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Cacari Stone L, Sanchez V, Bruna SP, et al. (2021). Social ecology of hypertension management among Latinos living in the U.S.–Mexico Border Region. Health Promot Pract, 152483992199304. 10.1177/1524839921993044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Mendoza S, Armbrister AN, Abraído-Lanza AF Are you better off? Perceptions of social mobility and satisfaction with care among Latina immigrants in the U.S. Social Sci Med. 2018;219:54–60. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Villani J, Mortensen K Decomposing the gap in satisfaction with provider communication between English- and Spanish-Speaking Hispanic patients. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(2): 195–203. 10.1007/s10903-012-9733-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.López-Cevallos DF, Flórez KR, Derose KP Examining the association between religiosity and medical mistrust among churchgoing Latinos in Long Beach, CA. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(1):114–121. 10.1093/tbm/ibz151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Bohm P, Paula Cupertino A Accommodating limited English proficient Spanish speakers in rural hospitals. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(4):1277–1279. 10.1007/s10903-014-0038-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Diamond L, Izquierdo K, Canfield D, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient–physician Non-English language concordance on quality of care and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1591–1606. 10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Gany F, Leng J, Shapiro E, et al. Patient satisfaction with different interpreting methods: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(S2):312–318. 10.1007/s11606-007-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Dueweke AR, Bridges AJ, Gomez DP The effects of interpreter use on agreement between clinician- and self-ratings of functioning in Hispanic integrated care patients. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(6):1547–1550. 10.1007/s10903-015-0288-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Hornberger JC, Gibsoon CD, et al. Eliminating barrier for non-English-speaking patients. Med Care. 1996;34 (8):845-856. 10.1097/00005650-199608000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Schenker Y, Perez-Stable E, Nickleach D, et al. Patterns of interperter use for hospitalized patients with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):712-717. 10.1007/s11606-010-1619-8z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Villalona S, Jeannot C, Yanez Yuncosa M, et al. Minimizing variability in interpretation modality among Spanish-speaking patients with limited English proficiency. Hisp Health Care Int. 2020;18(1):32–39. 10.1177/1540415319856329. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Wu AC, Leventhal JM, Ortiz J, et al. The interpreter as cultural educator of residents: improving communication for Latino parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006; 160(11):1145. 10.1001/archpedi.160.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Garcia EA, Roy LC, Okada PJ, et al. A comparison of the influence of hospital-trained, ad hoc, and telephone interpreters on perceived satisfaction of limited English-proficient parents presenting to a Pediatric Emergency Department: Pediatric Emergency Care. 2004;20(6):373–378. 10.1097/01.pec.0000133611.42699.08. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Mazor SS, Hampers LC, Chande VT, et al. Teaching Spanish to pediatric emergency physicians: effects on patient satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(7): 693. 10.1001/archpedi.156.7.693. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Juckett G Caring for Latino patients. Am Fam Phys. 2013;87(1): 48-54. [PubMed]

- 59.Ortega P Spanish language concordance in U.S. Medical Care: a multifaceted challenge and call to action. Acad Med. 2018;93(9): 1276–1280. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Lor M, Martinez GA Scoping review: definitions and outcomes of patient-provider language concordance in healthcare. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(10): 1883–1901. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Blanchard J, Nayar S, Lurie N Patient–provider and patient–staff racial concordance and perceptions of mistreatment in the health care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8): 1184–1189. 10.1007/s11606-007-0210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Schwei RJ, Kadunc K, Nguyen AL, Jacobs EA Impact of sociodemographic factors and previous interactions with the health care system on institutional trust in three racial/ethnic groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):333–338. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Kamimura A, Ashby J, Myers K, Nourian MM, Christensen N. Satisfaction with healthcare services among free clinic patients. J Commun Health. 2015;40(1):62–72. 10.1007/s10900-014-9897-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Schriber JR, Hari PN, Ahn KW, et al. Hispanics have the lowest stem cell transplant utilization rate for autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in the United States: A CIBMTR report: Race/Ethnicity and Transplant in Myeloma. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3141–3149. 10.1002/cncr.30747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.LaVeist LT, Isaac LA, Williams KP Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv Res. 2009;2093-2105. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Saadi A, Kim AY, Menkin JA, et al. Mistrust of researchers correlates with stroke knowledge among minority seniors in a community intervention trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020;29(1):104466. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Seltz LB, Zimmer L, Ochoa-Nunez L, et al. Latino families’ experiences with family-centered rounds at an academic children’s hospital. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(5):432–438. 10.1016/j.acap.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Gamp, M, Becker C, Tondorf T, et al. Effect of bedside vs. non-bedside patient case presentation during ward rounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3): 447–457. 10.1007/s11606-018-4714-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Ratelle JT, Sawatsky AP, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Implementing bedside rounds to improve patient-centred outcomes: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28(4):317–326. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007778. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Yeheskel A, Rawal S. Exploring the ‘patient experience’ of individuals with limited English proficiency: a scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(4): 853–878. 10.1007/s10903-018-0816-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Anttila A, Rappaport DI, Tijerino J, et al. Interpretation modalities used on family-centered rounds: perspectives of Spanish-speaking families. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(8):492–498. 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0209. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 110 kb)