Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to identify patients at risk of long-term hypocalcaemia following total thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease, and to determine the thresholds of postoperative day 1 serum calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) at which long-term activated vitamin D treatment can be safely excluded.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of 115 consecutive patients undergoing total thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease at a university referral centre between 2010 and 2018. Outcome measures were the day 1 postoperative adjusted calcium and PTH results, and vitamin D analogue need at 6 months postoperatively. Logistic receiver operating curves were used to identify optimal cut-off values for adjusted serum calcium and serum PTH, and sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated.

Results

Temporary hypocalcaemia was observed in 20.9% of patients (mean day 1 serum adjusted calcium 2.2±0.14mmol/l and PTH 4.15±2.42pmol/l). Long-term (>6 months) activated vitamin D analogue therapy was required in five patients (4.3%), four of whom had normal serum PTH and one with undetectable PTH at 6 weeks post surgery. No patient with a day 1 postoperative calcium >2.05mmol/l and detectable PTH required vitamin D supplementation at 6 months post surgery (100% sensitivity, PPV 50%, NPV 100%).

Conclusions

The biochemical postoperative day 1 thresholds identified in this paper have a 100% NPV in the identification of patients who are likely to require either no or only temporary activated vitamin D supplementation. We were able to identify all patients requiring activated vitamin D supplementation 6 months postoperatively from the day 1 postoperative serum calcium and PTH values, while excluding those that may only need temporary calcium supplementation. These threshold levels could be used for targeted follow-up and management of this subset of patients most at risk of long-term hypocalcaemia.

Keywords: Graves’ disease, Hypoparathyroidism, Parathyroid hormone, Calcium, Total thyroidectomy

Introduction

Treatment options for Graves’ disease consist of antithyroid medication, radioiodine and total thyroidectomy (TTx). It is well established that TTx is the preferred surgical option for patients with poorly controlled Graves’ disease, eye involvement, goitre or those with a contraindication to radioiodine.1 However, TTx is associated with morbidity, with hypocalcaemia being the most common and severe.2 Graves’ disease is an independent risk factor for post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia following TTx.3 The British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons (BAETS) national audit has reported transient hypocalcaemia, defined as hypocalcaemia lasting 6 months or less, in up to 27% of patients undergoing TTx, while long-term hypocalcaemia, due to permanent hypoparathyroidism, occurred in up to 5.3% of patients.4

Postoperative hypocalcaemia is most likely to occur as a result of local trauma from manipulation, devascularisation or unintended resection of normal parathyroid glands at time of surgery. During the subsequent period of hypoparathyroidism, the remaining parathyroid glands do not produce sufficient active parathyroid hormone (PTH) to maintain calcium homeostasis, thus leading to hypocalcaemia. This can present in the postoperative period symptomatically or asymptomatically and requires calcium supplementation, with or without vitamin D analogues, and regular monitoring of biochemistry. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes of hypoparathyroidism can impact on life survival, with permanent hypoparathyroidism after TTx having a twofold increase in mortality compared with those without permanent hypoparathyroidism.3 Therefore, early identification of patients with long-term hypocalcaemia is of great importance because it can allow tailored intervention and follow-up of patients.

The primary outcome measure was dependence on activated vitamin D supplements at 6 months postoperatively. The secondary outcome was to determine the thresholds of day 1 postoperative serum calcium and PTH at which long-term vitamin D treatment could be safely excluded in the setting of a specialist tertiary referral endocrine centre in the UK.

Methods

Consecutive patients diagnosed with Graves’ disease and undergoing TTx from a prospectively maintained database of endocrine surgery at a university tertiary referral centre between 2010 and 2018 were studied.

Data collected consisted of standard patient demographics, morning postoperative day 1 adjusted serum calcium and serum PTH levels, 6-month postoperative adjusted serum calcium and serum PTH levels, and the prescription of activated vitamin D analogue supplementation (1-alphacalcidol, 250–2,000ng daily) at 6 months post surgery identified from prescription records from the online Welsh Clinical Portal system, which accesses general practice prescription records and was the primary outcome measure.

In this study, transient hypocalcaemia is defined as postoperative adjusted serum calcium levels <2.1mmol/l for up to 6 months. Long-term hypocalcaemia is defined as activated vitamin D dependence at 6 months postoperatively, which is a surrogate marker of hypoparathyroidism. These definitions align with BAETS criteria. No patients were lost to follow-up and no patients were excluded. No patients underwent concomitant parathyroid surgery. Postoperatively, we do not routinely prescribe calcium and vitamin D supplementation to all patients as standard. Rather, calcium supplementation is reserved for patients with a postoperative day 1 serum calcium <2.05mmol/l and selectively for patients who are symptomatic with a serum calcium >2.0mmol/l. Vitamin D supplementation, where required, is prescribed on a case-by-case basis following assessment at a postoperative outpatient appointment.

All patients in this study underwent surgery by one of two consultant endocrine surgeons (MS or DSC) or by a senior endocrine surgical trainee under supervision at a tertiary centre. Both surgeons contribute their outcomes to the national BAETS audit. Patients with treatment-resistant Graves’ disease may be treated with Lugol’s iodine in this unit, although this does not form part of the usual preoperative preparation. Intraoperatively, if a parathyroid gland is inadvertently resected or identified on the specimen, it is auto-transplanted back into the sternocleidomastoid muscle. We do not use auto-fluorescent imaging or indomethacin green to identify or assess the vascularity of parathyroid glands.

Continuous variables are reported as mean (sd) or median (interquartile range), depending on their distribution. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies with percentages. Logistic receiver operating curves (ROC) were used to identify optimal cut-off values for adjusted serum calcium and serum PTH. Optimal cut-off points were obtained by minimising the distance between points on the ROC curve and the upper left corner. The optimum combined serum calcium and PTH levels were then used to test the reliability of these measurements in our cohort. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated.

Analysis was undertaken using SPSS software (v. 23, IBM). The study has been reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery 2019 guidelines.5

Results

One hundred and fifteen consecutive TTx were performed for Graves’ disease. Of these, 100 patients were women (86.9%) and the median age of the cohort was 37 (30–50) years. The mean postoperative day 1 adjusted serum calcium was 2.2±0.14mmol/l and PTH was 4.15±2.42pmol/l. Temporary hypocalcaemia (<2.1mmol/l) was observed in 24 patients (20.9%) up to 6 months post surgery. We found five patients (4.3%) dependent on activated vitamin D analogue therapy at 6 months post TTx; all had undetectable postoperative PTH levels at day 1. Of these patients, four had normal range postoperative serum PTH (parathyroid insufficiency) and one had an undetectable serum PTH (hypoparathyroidism) at 6 months post TTx.

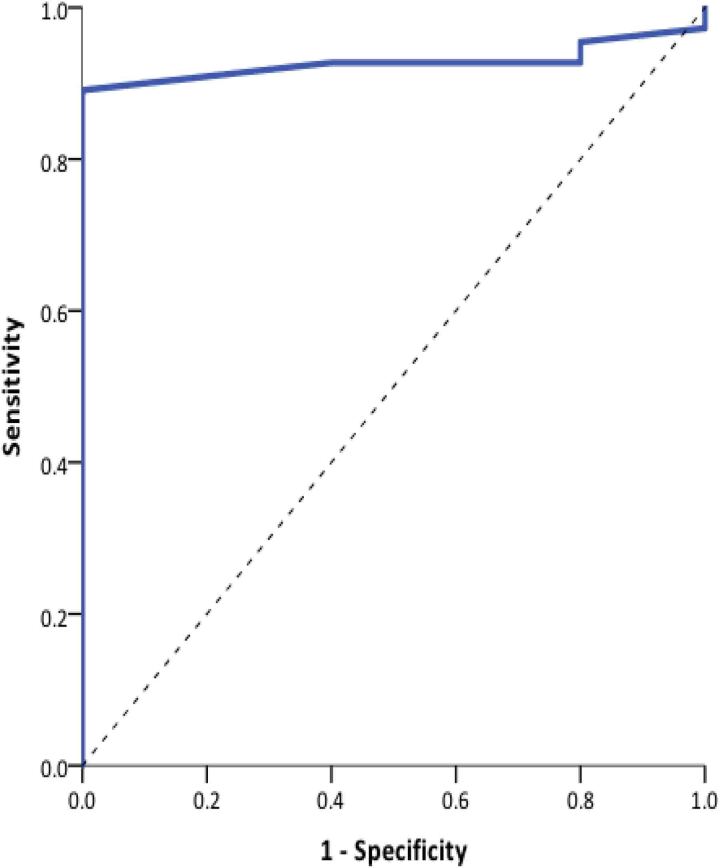

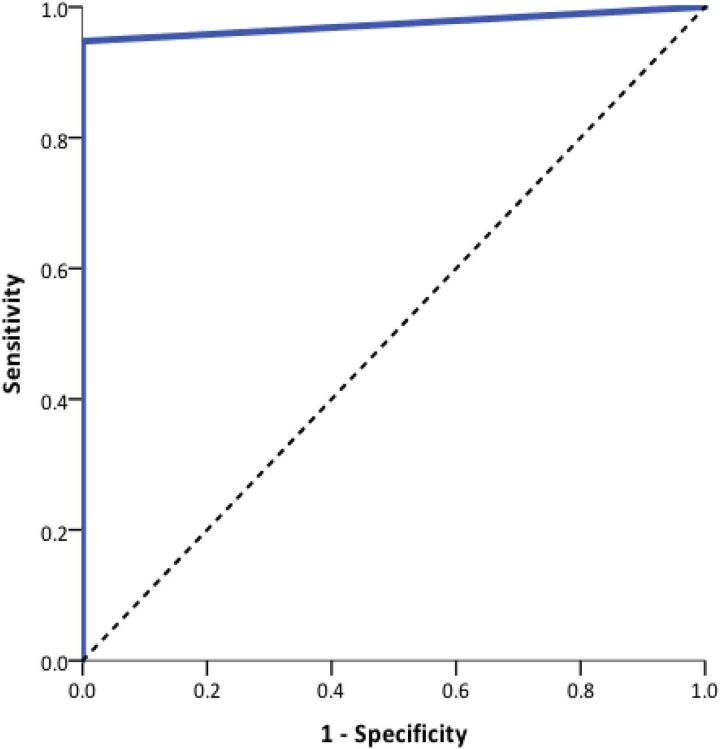

ROC analysis demonstrated an optimum cut-off value for postoperative day 1 serum calcium of <2.05mmol/l. This yielded a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 100% (Figure 1). ROC analysis to determine the postoperative day 1 serum PTH cut-off value showed the optimum value was an undetectable PTH (<0.5pmol/l), yielding a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 100% (Figure 2).

Figure 1 .

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of postoperative day 1 adjusted serum calcium and long-term hypoparathyroidism. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) = 0.974 (95% confidence interval 0.943 to 1.00; p<0.0001).

Figure 2 .

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of postoperative day 1 serum parathyroid hormone and long-term hypoparathyroidism. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) = 0.974 (95% confidence interval 0.943 to 1.00; p<0.0001).

Table 1 shows the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of activated vitamin D dependence in relation to serum calcium and PTH. When the optimal values derived from the ROC analyses were used in combination, this test was 100% specific and had a 100% NPV; this was the same for having hypocalcaemia on postoperative day 1 for the requirement of long-term vitamin D analogues following TTx in Graves’ disease. Of the 24 patients with postoperative hypocalcaemia, only 10 fulfilled the cut-off criteria to be considered at high risk of long-term hypoparathyroidism. All five patients that developed long-term vitamin D dependency were identified within this subgroup, as shown in Table 2.

Table 1 .

Evaluation of diagnostic ability of postoperative biochemistry

| Calcium <2.1mmol/l | Undetectable PTH | Calcium <2.05mmol/l and undetectable PTH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=24 | n=11 | n=10 | |

| Sensitivity | 100 | 83.33 | 100 |

| Specificity | 82.73 | 94.68 | 94.74 |

| Positive predictive value | 20.83 | 50 | 50 |

| Negative predictive value | 100 | 98.89 | 100 |

PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Table 2 .

Vitamin D dependence

| Vitamin D at 6 months | ||

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| Hypocalcaemia (n=24) | 19 | 5 (20.8%) |

| PTH undetectable (n=11) | 6 | 5 (45.5%) |

| Calcium <2.05mmol/l and PTH undetectable (n=10) | 5 | 5 (50.0%) |

PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated a combined threshold value for postoperative day 1 calcium and PTH, below which patients can be considered at high-risk of permanent hypocalcaemia following TTx for Graves’ disease. Conversely, patients with biochemical parameters above these critical levels are very unlikely to require more than temporary vitamin D supplementation.

The combined postoperative biochemistry has a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94.74%, which is higher than calcium or PTH levels alone. The findings are in keeping with a previous study at our institution for thyroidectomy undertaken for all pathology; however, the current study focuses on Graves’ disease and activated vitamin D analogue supplementation at 6 months.6 The ability to detect patients at risk of both transient and long-term hypoparathyroidism after TTx for Graves’ disease in the immediate postoperative period facilitates targeted follow-up of at-risk patients, while safely being able to exclude patients not at risk of long-term of permanent hypoparathyroidism.

Numerous studies have attempted to identify the optimum method to select those patients most at risk of hypocalcaemia following thyroid surgery. Postoperative hypocalcaemia is the single most important risk factor for the development of long-term hypocalcaemia; however, the need to monitor calcium postoperatively not only delays discharge for these patients but leads to a significant healthcare burden and patient anxiety. Serial measurements of serum calcium alone have been shown to be burdensome, and unable to safely rule out patients not at risk of developing permanent hypocalcaemia.7 Previous suggestions of routine calcium supplementation have been shown to be ineffective, and lead to all patients requiring longer-term follow-up because they complicate the detection of true hypocalcaemia.8 There is a need for individual institutions to establish local protocols to identify patients at risk of long-term hypocalcaemia using their own biochemical thresholds and timings of measurement.9 This is because of the difficulty in extrapolation and comparisons from other studies due to a variation in calcium and PTH assays, time of measurement as well as the threshold levels used to identify patients at risk.

Postoperative day 1 PTH levels alone can be used to identify at-risk patients, with undetectable PTH levels a predictor of hypocalcaemia; however, patients with intermediate PTH provided an area of uncertainty, still requiring monitoring and potential treatment.10 The mean relative decline in PTH measured 1h postoperatively has also been used as a predictor of postoperative or long-term hypocalcaemia; however, this still does not safely permit exclusion of those patients who are not at risk of permanent hypocalcaemia.11

Measurement of intact PTH (iPTH) is an accurate representation of the true parathyroid state. In recent years, an iPTH assay has been investigated for the prediction of postoperative symptomatic hypocalcaemia. No patient with iPTH ≥6.3pg/ml on the first postoperative day developed permanent hypoparathyroidism. By contrast, iPTH concentrations <6.3pg/ml have not proved to be a strong predictor of this condition.12

Other methods of predicting hypoparathyroidism have been explored. A pilot study using intraoperative parathyroid gland angiography with the fluorescent dye Indocyanine Green (ICG) has shown that all patients with at least one well-vascularised parathyroid gland using ICG scores had normal PTH levels on day 1 postoperatively.13 An intraoperative PTH assay has also been used to assess patients at risk of hypocalcaemia, enabling quicker identification of at-risk patients with results available 15–20min after the operation, facilitating earlier supplementation.14 Assessment of parathyroid glands in situ (PGRIS) has shown that in situ parathyroid preservation is critical in preventing permanent hypoparathyroidism after TTx; patients with a lower PGRIS score having a higher rate of postoperative hypocalcaemia. PGRIS was shown to have a synergistic effect with early postoperative supplementation for those with temporary hypoparathyroidism restoring parathyroid function.15

In comparison, our method is simple, cheap and reproducible, not involving any further training or equipment, and allows us to focus our follow-up on a high-risk patient group. Also, our study is specific for patients with Graves’ disease, whereas previous studies have not focused purely on Graves’ disease as an indication for thyroidectomy, which has been associated with a higher rate of hypocalcaemia and complications following thyroidectomy independent of other factors.

Potential limitations of this study include its retrospective design and the single-centre design. However, we have no patients lost to follow-up, and analysis of consecutive patients and data was derived from a prospectively maintained and validated database of endocrine surgery with outcomes submitted to the BAETS national registry.4 The single-centre design limits confounders because the surgical and postoperative management of patients has remained consistent.

Nonetheless, compared with other strategies, our study allows for accurate identification of at-risk patients using a simple, reproducible and reliable method, facilitating early discharge of all patients, with targeted follow-up for those identified as at risk of long-term hypoparathyroidism following TTx for Graves’ disease.

Conclusions

In our cohort, the incidence of long-term hypoparathyroidism was 4% after TTx for Graves’ disease. Postoperative day 1 serum calcium <2.05mmol/l with an undetectable serum PTH identified all patients in our cohort who remained vitamin D dependent at 6 months after surgery, while excluding those who may only need temporary calcium supplementation, therefore enabling targeted follow-up and management of this subset of patients.

References

- 1.Burch HB, Cooper DS. Management of graves disease a review. JAMA 2015; 314: 2544–2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Malki HO, Abouqal R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of predictors of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almquist M, Ivarsson K, Nordenström E, Bergenfelz A. Mortality in patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 1313–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chadwick D, Kinsman R, Walton P, editors. British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons. Fifth National Audit Report. 5th ed. Henley-on-Thames: Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R, Abdall-Razak A, Crossley Eet al. STROCSS 2019 guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2019; 72: 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong C, Price S, Scott-Coombes D. Hypocalcaemia and parathyroid hormone assay following total thyroidectomy: predicting the future. World J Surg 2006; 30: 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graff AT, Miller FR, Roehm CE PT. Predicting hypocalcemia after total thyroidectomy: parathyroid hormone level vs. serial calcium levels. Ear Nose Throat J 2010; 89: 462–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore FD Jr. Oral calcium supplements to enhance early hospital discharge after bilateral surgical treatment of the thyroid gland or exploration of the parathyroid glands. J Am Coll Surg 1994; 178: 11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di FF, Casella C, Bugari Get al. Identification of patients at low risk for thyroidectomy-related hypocalcemia by intraoperative quick PTH. World J Surg 2006; 30: 1428–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grodski S, Farrell S. Early postoperative PTH levels as a predictor of hypocalcaemia and facilitating safe early discharge after total thyroidectomy. Asian J Surg 2007; 30: 178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo ST, Chang JW, Jin Jet al. Transient and permanent hypocalcemia after total thyroidectomy: early predictive factors and long-term follow-up results. Surgery 2015; 158: 1492–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canu GL, Medas F, Longheu Aet al. Correlation between iPTH levels on the first postoperative day after total thyroidectomy and permanent hypoparathyroidism: Our experience. Open Med (Wars) 2019; 14: 437–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal Fortuny J, Sadowski SM, Belfontali Vet al. Randomized clinical trial of intraoperative parathyroid gland angiography with indocyanine green fluorescence predicting parathyroid function after thyroid surgery. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 350–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo CY, Luk JM, Tam SC. Applicability of intraoperative parathyroid hormone assay during thyroidectomy. Ann Surg 2002; 236: 564–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorente-Poch L, Sancho JJ, Ruiz S, Sitges-Serra A. Importance of in situ preservation of parathyroid glands during total thyroidectomy. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]