Abstract

Depression prevalence is high, impacting approximately 20% of Americans during their lifetime, and on the rise due to stress and loss associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the high prevalence of depression, unacceptable treatment access disparities persist. When depression goes untreated, it leads to substantial negative impacts in multiple life domains. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the gold-standard psychosocial treatment for depression, remains largely unavailable to individuals living with depression, particularly individuals who are members of underrepresented groups in our society. Digital mental health interventions (DMHI) have led to important advances in extending the reach of CBT for depression; however, they are underutilized and treatment engagement remains low. We sought to address some of the current gaps in DMHI by developing an online platform for delivering CBT for depression that is entertaining, simple and straightforward, and tailorable. First, this article introduces our online platform, Entertain Me Well (EMW) and its key innovations, including the use of an engaging, character-driven storyline presented as “episodes” within each session, as well as customizable content that allows for tailoring of text, images, and examples to create content most relevant to the target client population, context, or setting. Next, we describe two EMW depression treatment programs that have been tailored: one for delivery in the rural church setting, called Raising Our Spirits Together, and one tailored for delivery in dialysis centers, called Doing Better on Dialysis. Finally, we discuss future directions for the EMW platform, including the ability to create programs for other common mental health and health conditions, the development of additional character-driven storylines with greater treatment personalization, translation of content in multiple languages, and the use of additional technological innovation, such as artificial intelligence like natural language processing, to enhance platform interactivity.

Keywords: T-CBT, DMHI, depression, mental health treatment, access to care

Depression is among the most common mental health conditions, with approximately 20% of U.S. adults experiencing depression during their lifetime (Hasin et al., 2018, Kessler et al., 2005, Kessler et al., 2003, Kessler et al., 1994) and about 8% experiencing depression in any given 2-week period (Brody et al., 2018). In fact, depression is the leading cause of global disease burden (Friedrich, 2017), with substantial negative effects on multiple life domains, including family and social relationships and work and school (Marciniak et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2003). Untreated depression is estimated to cost the United States $210 billion per year (Greenberg et al., 2015).

The current COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating psychological distress and its associated impacts, with recent literature suggesting that about one-third of U.S. residents have experienced depression during the pandemic, which may be due in part to increased social isolation, grief and loss, and financial distress (Czeisler et al., 2020, Luo et al., 2020, Salari et al., 2020).

Despite high levels of depression prevalence, unacceptable treatment access disparities persist, representing a critical public health concern. Research demonstrates that over half of adults living with a mental health condition do not receive treatment (Han, Compton, Blanco, & Colpe, 2017), whereas approximately two-thirds of persons living with depression do not receive treatment, (Kessler et al., 2005, Olfson et al., 2016). Further, on average, there is an 11-year gap between the onset of a mental health condition and treatment-seeking (Mojtabai and Jorm, 2015, Wang et al., 2004).

These treatment access disparities are often driven by barriers related to treatment availability, accessibility, and acceptability. Availability of treatment has been negatively impacted by the persistent shortage of mental health providers in the U.S., particularly in communities of color, rural communities, and low-income communities (Conner et al., 2010, Hunt et al., 2015, Bolin et al., 2015, Hartley, 2004, Johnson et al., 2006). This shortage is likely to be exacerbated by the increased need for mental health treatment precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, cost (Alang, 2015, Webb et al., 2017), being underinsured or uninsured (Creedon and Cook, 2016, Rowan et al., 2013), travel burden and distance to care (Webb et al., 2017), inconvenient hours of operation (Mojtabai et al., 2011, Salloum et al., 2016), and competing caregiving demands (Dockery et al., 2015, Mosher et al., 2015) limit access to mental health treatment when it is available. Again, these accessibility barriers are more salient for Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC), rural residents, and individuals who are economically disadvantaged (Bolin et al., 2015, Conner et al., 2010, Hartley, 2004, Hunt et al., 2015, Johnson et al., 2006). Finally, and perhaps most important, the stigma around mental health conditions and treatment remains. Sources of stigma include, but are not limited to, concerns about showing personal weakness, beliefs that one should be able to cope with mental health challenges on their own, and concerns that mental health diagnosis will result in labeling and loss of opportunity (Corrigan, 2004, Corrigan et al., 2014, Parcesepe and Cabassa, 2013, Pescosolido et al., 2013).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), an approach that focuses on increasing activities and addressing inaccurate thoughts, is recognized as gold-standard psychosocial depression care (Butler et al., 2006, Cuijpers et al., 2013, David et al., 2018, Hans and Hiller, 2013, Hofmann et al., 2012). CBT is effective when delivered in individual and group modalities (e.g., Butler et al., 2006, Hofmann et al., 2012), across diverse populations (e.g., Ayers et al., 2007, Wilson and Cottone, 2013), and in non-mental health settings (e.g., Himle et al., 2014, Roy-Byrne et al., 2005, Zhang et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2019). Despite decades of research demonstrating its strong evidence base, as well as client preference for psychosocial care over pharmacological treatment (Dorow et al., 2018, Dwight-Johnson et al., 2000, McHugh et al., 2013), CBT is not widely available. Consistent with broader trends related to the availability of mental health treatment, there are a limited number of providers adequately trained and qualified to provide CBT (Cavanagh, 2014). Additionally, accessibility and acceptability barriers remain a concern as well. Even when CBT is available, many clients drop out of treatment after one or two sessions before CBT’s benefits are realized (Eisenberg et al., 2011, Fernandez et al., 2015, Hans and Hiller, 2013). Clients’ most commonly identified reasons for dropping out of CBT include: (a) the approach is found to rely on text-heavy homework and is not engaging, (b) attending in-person sessions is inconvenient and resource-intensive, and (c) some find the approach to be unhelpful (DeJong et al., 2012, Kehle-Forbes et al., 2016).

Digital mental health interventions (DMHI), including technology-assisted CBT (T-CBT), have emerged as promising strategies for effectively treating depression while reducing documented barriers to care (Andrews et al., 2010, Andrews et al., 2018, Firth et al., 2017, Li et al., 2014). There is growing empirical support indicating that T-CBT for depression is effective and, in fact, comparable to face-to-face treatment, particularly when complemented by support from a provider (Andrews et al., 2010, Andrews et al., 2018; Cuijpers et al., 2019; Ebert et al., 2015, Newby et al., 2016, Richards and Richardson, 2012, Wright et al., 2019).

Although technology barriers remain a challenge for some, access to the technology needed to receive T-CBT is increasing. In less than a decade, smartphone ownership among U.S. residents increased by 46%, from 35% in 2011 to 81% in 2019 (Pew Research Center, 2019a). This trend is consistent, though slightly lower, among underrepresented groups, as 80% of Black residents, 79% of Hispanic residents, 71% of rural residents, and 71% of residents with annual incomes of $30,000 or less report owning smartphones (Pew Research Center, 2019a). Similarly, about three-quarters of U.S. residents have access to broadband internet at home (Pew Research Center, 2019b). However, among adults aged 65 years or more (59%), residents in households with annual incomes of $30,000 or less (56%), and Black (66%), Hispanic (61%) residents, and rural residents (63%) are less likely to have broadband internet access at home (Pew Research Center, 2019b). There is likely to be continued growth in access to broadband internet given the increased focus on digital inclusion efforts and policy proposals seeking to classify the internet as a public utility (Rahman, 2018), suggesting the potential for further growth in the implementation and utilization of T-CBT as an important strategy for addressing depression treatment access disparities.

Technology-assisted CBT (T-CBT) offers an important opportunity to expand access to destigmatized evidence-based depression treatment for many individuals for whom face-to-face treatment is not a viable option. The potential of T-CBT for depression has been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic; yet challenges to both distributing T-CBT widely and engaging individuals with depression in T-CBT remain. Lack of engagement and early dropout remain perhaps the most critical issues with current T-CBT programs. It is common for individuals using currently available T-CBTs to drop out early in the course of treatment and never reengage with care (Fernandez et al., 2015). Similarly, evidence from meta-analytic work suggests a median completion rate of 54% for T-CBT programs (Waller & Gilbody, 2009). Meta-analytic review findings also suggest that treatment adherence for T-CBT programs guided by a clinical support person is more similar to face-to-face CBT; yet the average completion rate among the studies of guided T-CBT included in this review was still only 65% (Van Ballegooijen et al., 2014).

Two key factors likely impact user engagement with T-CBT. First, many well-established, empirically supported T-CBTs are text-heavy and highly didactic, contributing to high rates of dropout or noncompletion (Farvolden et al., 2005, Waller and Gilbody, 2009). Most mental health treatments are initially developed and tested among higher socio-economic status, non-Hispanic White, urban populations. The content and structure of T-CBT programs often use jargon and introduce concepts in an academic, text-heavy way that may make many individuals rightly feel that these interventions are not made for them.

Second, research consistently shows that tailoring treatment to specific populations, contexts, and settings is associated with increased uptake, as well as acceptability and sustainability (Barrera et al., 2013, Krebs et al., 2010, Morrison, 2015, Noar et al., 2007). Yet, most currently available, empirically supported T-CBTs employ a one-size-fits-all approach and are not designed to be easily modified. In fact, to our knowledge, no existing T-CBT platforms can be flexibly tailored for particular target populations to reflect their unique needs and experiences (Twomey et al., 2017). As existing T-CBT platforms were not designed to be easily modified to fit the needs of particular clients or groups of clients, needed modifications are costly and time-consuming, with new web development and programming needed to tailor treatment. This “one size fits all” model not only prohibits maximal treatment effect across different populations but also creates barriers to intervention uptake.

In sum, there is unmet potential and promise for increasing access to evidence-based depression treatment through T-CBT. However, the existing structure of available T-CBT programs limits treatment engagement. Innovative approaches are necessary in order to create T-CBT programs that are engaging, accessible, and acceptable to individuals with depression, with specific attention to groups who are underrepresented and underserved. In order to address existing limitations of T-CBT and enhance the potential for T-CBT to alleviate mental health treatment access disparities, we created Entertain Me Well, an online platform designed to deliver intervention content entertainingly while allowing for low-cost customization of content. Our goal was to make therapy enjoyable by developing a simple and engaging T-CBT for depression that is easy to change, scale-up, and distribute. In this article, we introduce Entertain Me Well (EMW) as a platform for delivering depression intervention programs and describe its key innovations: (a) entertaining delivery through a character-driven storyline, (b) quick and easy, low-cost intervention tailoring, and (c) simple, straightforward content geared to multiple learning styles. We then introduce two depression treatment programs delivered within the EMW platform that have been tailored for specific populations, contexts, and treatment modalities (individuals v. group). Finally, we discuss the next steps and additional opportunities for innovation within the EMW platform.

Entertain Me Well

Entertain Me Well is a technology-assisted platform designed to deliver CBT for depression in an engaging and flexible way, without compromising fidelity to core CBT elements. EMW was developed in 2019 as a way to increase access to and engagement with evidence-based depression treatment for adults. EMW was intentionally designed to overcome weaknesses of many existing T-CBT interventions that are static, text-heavy, and delivered in a highly didactic style, contributing to low engagement and adherence (Knowles et al., 2015).

EMW contains gold-standard elements of CBT for depression, including behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and problem solving (Beck, 2011), delivered across eight sessions (see Table 1 ). The CBT content is introduced via an engaging, entertaining character-driven storyline, video-based educational content, and tailorable text and image-based educational content that includes specific examples and vignettes. All content is presented in a simple, straightforward manner that avoids text-heavy approaches and jargon and appeals to multiple learning preferences. Each tailored EMW depression treatment program has an accompanying workbook that includes in-session activities and weekly homework exercises.

Table 1.

Entertain Me Well Depression Treatment Program Overview

| Session | Core CBT Principle | Session Summary | Homework/Action Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Low Mood & Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Psychoeducation |

|

Set Goals for Time in Program |

| 2: The Importance of Taking Action | Behavioral Activation |

|

Activity Scheduling |

| 3: Tools for Taking Action | Behavioral Activation |

|

Set Activity Goals |

| 4: Identifying Negative Thoughts | Cognitive Restructuring |

|

Identify Negative Thoughts/Complete Thought Tracker |

| 5: Talking Back to Negative Thoughts | Cognitive Restructuring |

|

Talk Back to Negative Thoughts/Complete Thought Record and Take Action Based on More Helpful Thoughts |

| 6: Beliefs and Our Mood | Identifying and Challenging Faulty Beliefs |

|

Continue Working on Cost-Benefit Analysis and Take Action on More Flexible Belief |

| 7: Overcoming Setbacks | Problem Solving |

|

Continue Working on the 5-Steps of Problem Solving and Take Action Based on Solution(s) Selected |

| 8: Putting It All Together & Relapse Prevention | Program Review and Relapse Prevention |

|

None |

Development of the EMW platform was co-led by a social work faculty and a social work/psychiatry faculty member (AW, JH) with deep experience in CBT and mental health intervention research. An interdisciplinary approach facilitated content creation as well as the look, feel, and functionality of the platform, with collaborators from social work, psychiatry, psychology, nursing, and music, theater, and dance, as well as community partners, engaging in an iterative process and providing feedback on evolving iterations of the platform. Additionally, the co-developers worked closely with a technology and media company to create the platform design, user experience, and user interface. The technology and media company provided expert services related to web and mobile application development and design, programming, animation, and audio production.

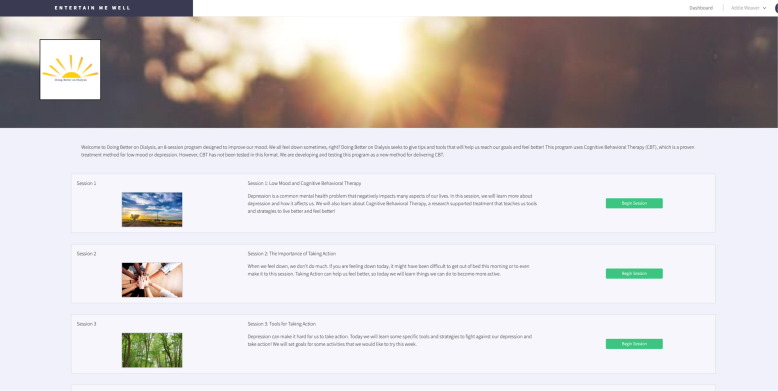

EMW includes both a user side or front-end that allows individuals to access and complete the treatment program and a team manager or back-end that enables researchers and program administrators to create and tailor EMW treatment programs. The user side of the program requires users to create a user ID and password and then prompts them for an invite code. The invite code takes users to the depression treatment program specifically tailored for their population, setting, or context (see Figure 1 ). Users first see a program landing page that provides a summary of their overall program, as well as a brief summary of each session. Users are prompted to begin Session 1. Subsequent sessions remain locked until users reach them in the program. Program materials, in both the technology-assisted platform and in the accompanying workbook, introduce the program as being comprised of eight weekly sessions and encourage users to complete one session per week. Sessions can be completed individually or in a group format. Individual sessions take between 25–35 minutes to complete, whereas group sessions take between 60–90 minutes to complete.

Figure 1.

EMW landing page or program home page for Doing Better on Dialysis (DBD)

The team manager or the back end of the program allows researchers and program administrators to access all existing depression treatment programs housed on EMW. The back end of the program provides a video production–like interface, in which the platform manager can modify customizable content. Sophisticated customizing features, like uploading a video or picture, changing font, and modifying page layout, among others, can be easily achieved. The “view” function enables researchers and program administrators to preview the new, customized content from the client’s perspective, and to implement additional refinements if necessary. A media library is accessible to platform managers of different EMW depression treatment programs (e.g., one tailored for patients with a chronic condition and one tailored for rural adults) to facilitate resource sharing.

EMW’s Key Innovations

EMW utilizes three key innovations to increase treatment engagement and acceptability. These innovations include: (1) entertaining delivery through a character-driven storyline, (2) quick and easy, low-cost treatment tailoring capabilities while retaining core CBT elements, and (3) presentation of intervention content in a simple, straightforward manner.

Entertaining Delivery of Content Through Character-Driven Storyline

EMW utilizes a character-driven storyline to introduce and reinforce core CBT concepts and show how they are applied in the character’s life. The character-driven storyline is embedded within each session, almost like an episode of a television show, and each session’s “episode” ends with a cliffhanger. This cliffhanger or narrative hook is designed to leave users interested and wanting to engage with the next session to find out what happens to the character.

The character-driven storyline developed for the online depression intervention centers around Billi the balloon (see Figure 2 ), an animated character who benefitted in the prior year from a course of CBT for her depression. Billi’s story occurs in both the present time, where she is being interviewed about her experiences with depression and getting help, and in the past, where we retrospectively see what life was like for her when she was feeling down and how she used the CBT skills and tools she learned to improve her mood and feel better. When we see Billi in the present, she provides commentary and insights related to her prior experience with depression while teaching users about core CBT concepts and strategies and providing tips for applying CBT skills and tools. When we see Billi in the past, we see what was happening in her life when she was depressed and how she navigated both successes and setbacks using core CBT strategies of behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and problem-solving training.

Figure 2.

Billi the balloon teaches EMW users about CBT through her character-driven storyline. Here we see Billi (L to R); (1) writing down activity goals as part of behavioral activation, (2) attending her high school reunion even though she wasn’t sure she wanted to and didn’t think it would go well, and (3) reconnecting with a friend who she had isolated herself from when feeling depressed.

Table 2 presents an overview of Billi’s story, the alignment between Billi’s story and core CBT content, as well as an image from each session. Billi’s overall retrospective storyline centers around a key event, an upcoming high school reunion. We see what happens to Billi as she prepares for this event, attends the event, and moves on after the event. During Billi’s story, she experiences challenges and setbacks while putting forth an effort to use her CBT skills and tools. This mix of setbacks and successes was intentionally designed to match the real-world experience of clients who use CBT for depression.

Table 2.

Overview of Entertain Me Well’s Character-Driven Storyline and Core CBT Content

| Session | Core CBT Principle | Billi’s Story | Sample Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Low Mood & Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Psychoeducation |

|

|

| 2: The Importance of Taking Action | Behavioral Activation |

|

|

| 3: Tools for Taking Action | Behavioral Activation |

|

|

| 4: Identifying Negative Thoughts | Cognitive Restructuring |

|

|

| 5: Talking Back to Negative Thoughts | Cognitive Restructuring |

|

|

| 6: Beliefs and Our Mood | Identifying and Challenging Faulty Beliefs |

|

|

| 7: Overcoming Setbacks | Problem Solving |

|

|

| 8: Putting It All Together & Relapse Prevention | Program Review and Relapse Prevention |

|

|

Billi’s story is designed to enhance treatment engagement by facilitating a connection between program users and Billi as they follow her journey with depression and CBT. Users observe Billi using her CBT tools and skills throughout the program, offering concrete examples of ways to take action (behavioral activation), identify and talk back to negative thoughts (cognitive restructuring), and overcome setbacks (problem-solving). Given that narrative has been shown to increase comprehension, learning, and memory (Dahlstrom, 2014), watching Billi’s story unfold is likely to strengthen users’ understanding of and ability to apply CBT concepts. After seeing Billi use these tools and skills, users are asked to apply them in their own lives through in-session activities and weekly homework exercises.

Notably, while EMW contains fixed core content and structure to ensure CBT fidelity, the platform structure provides a streamlined process to create additional stories following a similar model. Although for our first depression treatment program, we created an animated character and storyline with broad appeal to a general adult population in the U.S. context, there is a substantial promise for developing additional stories centered around characters with diverse identities, experiences, and presenting problems. Additionally, although we made a conscious decision to develop an animated character and storyline as research demonstrates that animated characters have broader appeal and relatability to a general adult audience (e.g., George et al., 2013), the platform can easily accommodate live-action video storylines that align with core CBT session content.

Quick and Easy, Low-Cost Tailoring

Another key innovation developed as part of the EMW platform is the ability to engage in quick and easy, low-cost tailoring for target populations, settings, or contexts. Quick and easy customization of content has the potential to increase treatment engagement and intervention uptake. The EMW depression treatment program includes approximately 20% of content that can be easily modified with no additional cost.

The EMW platform was strategically designed to ensure that core CBT content delivered via the character-driven storyline and video-based education content remains unchanged, whereas text and image-based content that provides examples, vignettes, and education to reinforce core CBT content can be customized in a quick, easy, low-cost manner similar to existing word processing or presentation programs. Through the back end of the platform, researchers and program administrators are able to edit existing program content and create new content.

Specifically, the portions of the program that can be easily modified in real-time using the Edit feature in the EMW platform include text and image panels. Editing consists of revising or modifying existing text and image content to better reflect the lived experiences and realities of a particular target population being served (e.g., a list of activities that could be done for enjoyment or fun; see Table 3 for examples of tailored content). It is also possible to create new text and image-based content within the depression treatment program to further emphasize concepts or to enhance content to increase relevance to the target population being served (e.g., an inspirational quote meant to resonate with a particular group; see Table 3 for examples of tailored content). The process of tailoring involves editing or creating content within each session and creating a customized name for the depression treatment program (see below), as well as creating a unique program landing page, program-specific images as well as program and session summary statements (see Figure 1).

Table 3.

Examples of Tailored Content Across Two EMW Depression Treatment Programs

| Raising Our Spirits Together | Doing Better on Dialysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Example of Inspirational Quote |  |

|

| Session 2: Examples of Activities for Enjoyment & Accomplishment |  |

|

| Session 4: Common Negative Thoughts |  |

|

| Session 6: Common Faulty Beliefs |  |

|

When editing or creating new content within each session, researchers or program administrators can choose from advanced design templates. Once a template has been selected, researchers and program administrators can change or add images and videos by uploading them into the template. Text-based content can also be changed, added, or edited. The templates allow for the selection of page layout, as well as font size and format (e.g., bold, italic, underlined; bullet points, etc.).

All design templates that are edited or created are saved and stored in a media gallery. When tailoring the depression treatment, existing design templates can be selected and transferred to a new program and session, if relevant for the client population, setting, or context. In addition to saving all templates in the media gallery, all individual images used in any EMW program or session are stored and available to be used when creating new programs or tailoring a program. This concept allows researchers and program administrators to see all images currently used in existing treatment programs. They can choose to select an image used in another program or select a new image that is more appropriate or relevant for a specific target population, setting, or context. These tailoring capabilities within the EMW platform allow for content customization of text and image-based content in real-time, at little to no cost.

Presentation of Content in Simple, Straightforward Manner

EMW was intentionally designed to present content in a way that is widely accessible and inclusive. First, intervention content is presented in a simple, straightforward manner. This includes introducing core CBT concepts without using jargon. For example, rather than discussing “behavioral activation” as a CBT strategy, EMW presents the user with a simple message about the importance of taking action, and similarly, instead of introducing “cognitive restructuring,” EMW introduces the simpler concept of “talking back to negative thoughts.”

Second, intervention content was developed with attention to reading level. All core (nontailorable) intervention content across the eight sessions is between a fourth- and fifth-grade reading level based on the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level assessment conducted via the Microsoft Word Review function. Additionally, the Flesch reading ease score ranged from 79.5 to 84.9 across the eight sessions. The Flesch Reading Ease score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater readability. A Flesch Reading Ease score between 70–80 corresponds to an eighth-grade reading level, which is accessible to 80% of the adult population in the U.S. Finally, over 95% of EMW intervention content is presented using active voice, which, relative to passive voice, some long-standing evidence suggests bolsters comprehension (e.g., Turner & Rommetveit, 1967).

Third, EMW presents the majority of educational material using both audio and visual elements. This allows users to experience the content by both hearing and seeing the CBT concepts. The video-based educational content has voiceover audio that users hear while the same content is presented visually, either via text or images and graphics. This supports engagement and understanding among users with different learning preferences and needs.

Fourth, users are exposed to core CBT concepts in multiple ways, including the character-driven storyline, video-based education content, and text-based education content. Only after engaging with the material through these multiple channels are users asked to apply CBT concepts to their own lives. Introducing CBT content via these multiple approaches allows core concepts to be initially presented in a more didactic manner, where they are introduced and explained using both video and text-based audio and visual elements, followed by examples in the character-driven storyline when Billi attempts to apply these principles in her daily life. The didactic content includes text and image-based material that is tailorable, as described above, so that information presented is as relevant and applicable as possible for the target population, context, or setting being served, whereas the video-based content is not tailorable, but it is replaceable. By replaceable, we mean that the current video-based content delivering the character-driven storyline or education content can be switched out with new video-based content specifically created for the platform.

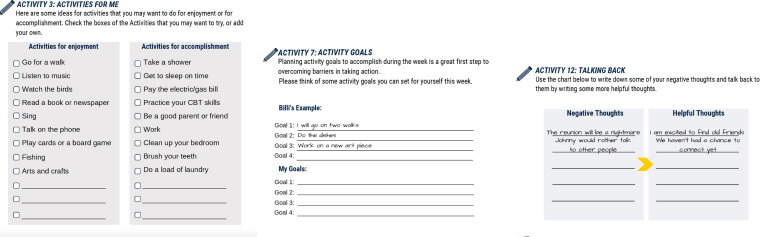

Finally, EMW was intentionally designed to incorporate low-burden activities and homework exercises into each session. For instance, activities supporting the application of core CBT concepts in both the main program and the accompanying workbook first include pre-populated choices that users can select from while leaving some space for users to add new content specific to their experiences. Additionally, some in-session activities consist of very focused, specific prompts that users can complete with short answers. This reduces the academic nature of the program and decreases the writing and time burden that may limit engagement with workbook-based exercises and homework recording forms. In-session workbook and program-based activities also include Billi’s example, so users have a model of how to complete the activity that connects to the character-driven storyline they engage with throughout the program (see Figure 3 ). As referenced above, like in any CBT-based intervention, users also have homework exercises to work on between sessions. In EMW, homework exercises and accompanying recording forms are also designed to be of a low burden to users. The workbook accompanying the web-based treatment includes scaled-down templates for activity scheduling, identifying negative thoughts, talking back to negative thoughts, cost-benefit analysis of faulty beliefs, and problem-solving. These templates offer simple, straightforward, organized ways to complete the action plan exercises without a substantial writing burden. This approach intends to increase engagement and adherence to in-session activities and action plans by making them quicker and easier to complete while retaining the integrity of core CBT strategies.

Figure 3.

EMW includes an accompanying workbook with in-session activities that provide Billi’s examples as a model for completing activities. These activities were also intentionally designed to be low burden, providing pre-populated choices that users can select as well as the option to add new choices that work better for them.

EMW Tailored Depression Treatment Program Examples

EMW has led to the development of multiple tailored depression treatment programs. Currently, we are in the process of testing EMW-based depression treatment programs tailored for rural adults and delivery in church settings, dialysis patients, adolescents and young adult cancer survivors, and low-income, rural, pregnant, and postpartum women receiving WIC services. Emerging pilot and feasibility data is promising, suggesting these tailored depression treatment programs reduce depressive symptoms and are engaging and acceptable to users (Weaver et al., 2021).

In this section, we introduce two tailored depression treatment programs, Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST) and Doing Better on Dialysis (DBD). These two programs have the same core CBT content, which includes the video-based educational content and the character-driven storyline featuring Billi. However, text, images, quotes, and examples have been tailored to the specific target populations, settings, and contexts being served. In both cases, the tailoring decisions were made by a range of key stakeholders through sustained engagement and collaboration with community partners, expert clinicians, and agency leaders who provided insight to modifications necessary to increase relevance and acceptability of the treatment program to the client group, setting, and context under consideration.

Raising Our Spirits Together

Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST), one of EMW’s depression treatment programs, was developed out of community-engaged research in rural Michigan seeking to increase access to mental health treatment for underserved rural residents (K01MH110605; Weaver, PI). Our community-engaged research identified a critical need for depression treatment and suggested that the church was a promising setting for delivering evidence-based depression care in rural settings, as it reduced a myriad of barriers related to availability, accessibility, and acceptability of mental health treatment (Weaver et al., 2019, Weaver et al., 2020).

Through collaboration between researchers and community partners, Raising Our Spirits Together was specifically tailored for group-based delivery in the rural church setting, facilitated by clergy. Therefore, tailoring involved modifications for both the rural context and the church setting. The iterative, community-engaged tailoring process included in-depth interviews with and feedback from multiple stakeholders in our partner rural community as well as regular, monthly meetings with partnering clergy. Through the tailoring process, we identified necessary modifications of images, text, quotes, and examples throughout the eight sessions. These modifications were intentionally made to reflect the lived experiences of rural residents and the rural church delivery setting. First, inspirational quotes included in each session were tailored to introduce a scripture verse that aligned with core CBT session content (see Table 3 for examples of tailored content). Second, images were modified to reflect natural scenes and landscapes consistent with the rural community setting. There was also attention to tailoring images to show persons engaging in activities, such as walking, hiking, and fishing, that can be easily done in rural settings. Third, examples related to core CBT strategies, such as behavioral activation and cognitive restructuring, were modified to reflect our target population of rural residents and the church setting. When introducing activities that could be done for enjoyment, examples included joining a bible study group, going fishing, playing a card or board game, or going to the county fair. It was important to tailor these examples and identify activities that users could realistically do in rural communities without prohibitive cost or travel burden. Additionally, examples of common faulty beliefs were tailored to reflect common rural cultural values of independence and self-reliance. The tailored faulty beliefs designed to fit with the rural context include: I must always put others first, I must never ask for help, and I must never appear weak.

Raising Our Spirits Together has been successfully piloted in a rural Michigan county (n = 9) and a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT; n = 84) of ROST is well under way (ClinicalTrials.gov # NCT04502186). Although our ROST pilot was small, with nine participants recruited using both in-person and virtual methods through a local food bank and two partner churches, results suggest a statistically and clinically significant decrease of depressive symptoms over time in the program (Weaver et al., 2021). Additionally, results indicate that ROST was acceptable and engaging to participants. For example, 100% of pilot participants completed at least 7 of the 8 treatment sessions (Weaver et al., 2021). Qualitative focus group interviews, conducted after each pilot session, suggest participants related well to Billi and her storyline and that the examples provided throughout the program were relevant and helpful (unpublished data). These focus groups helped us understand user engagement and satisfaction with ROST and led to identifying intervention refinements for the RCT. Of particular relevance to current challenges, the ROST pilot was initiated just before the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the original plan was to pilot ROST using a face-to-face small group approach, restrictions on gathering size necessitated a transition from in-person group sessions held at rural churches to pastor-led remote group sessions held via group videoconference (Zoom). A fully remote RCT of ROST in rural Michigan is well under way. To date, we have recruited approximately 40% of our 84 RCT participants and expect to complete the RCT by August 2022. In addition to clinical outcomes, we assess engagement and satisfaction via the User Engagement Scale (O’Brien et al., 2018) and in-depth qualitative interviews with participants randomized to the ROST condition at the end of the active treatment period. This critical data will support our ability to make refinements to the Entertain Me Well platform broadly and to specific elements of the tailored depression treatment programs to improve user experience and treatment acceptability.

Doing Better on Dialysis

A collaboration between the University School of Social Work, School of Medicine, and School of Nursing resulted in the development of Doing Better on Dialysis (DBD), an EMW depression treatment program tailored for individual delivery in dialysis centers with brief check-ins from social workers or nurses after each session. This collaboration was designed to increase access to evidence-based depression treatment among dialysis patients who have high rates of depression but experience extensive barriers to care given their chronic health condition. In developing DBD, the interdisciplinary research team conducted preliminary studies, including a qualitative study of dialysis patients’ perceptions of and receptivity to computer-assisted depression treatment (Himle et al., unpublished data) and a cross-sectional survey of nephrology social workers assessing the barriers and facilitators of delivering computer-assisted depression treatment in dialysis settings (Himle et al., unpublished data). This preliminary work suggested that technology-assisted depression treatment delivered in the dialysis center with brief in-person support from social workers or nurses would be feasible and acceptable.

Doing Better on Dialysis was specifically tailored for dialysis patients and for delivery in the dialysis center with brief check-ins from social workers or nurses at the end of each session. Tailoring focused on customizing content for dialysis patients, a population living with a chronic health condition, and for individual delivery in the dialysis center during their dialysis treatments. Like Raising Our Spirits Together, a team of researchers and multiple stakeholders from the dialysis center, including social workers, nurses, and physicians, collaborated to identify modifications to text, images, quotes, and examples, to increase intervention engagement and acceptability among dialysis patients with depression.

First, inspirational quotes from advocates for persons living with end-stage renal disease and persons on dialysis were selected and incorporated into Doing Better on Dialysis (see Table 3). Quotes from celebrities who are well-known, inspirational, and trusted were also included. Second, images were tailored to reflect the dialysis center context. In fact, photos were taken at the dialysis center, with staff and patient permission and releases, and included in the Doing Better on Dialysis treatment program. This allows users to see their peers and their providers when engaging with the intervention. Images of local landmarks in the region were also incorporated into the treatment program through the tailoring process. Third, examples used to illustrate and reinforce core CBT concepts and strategies were modified to reflect the experiences of dialysis patients. For example, most potential activities for enjoyment presented in DBD can be performed without substantial physical effort, such as calling a friend, playing games on the internet, taking a walk, and listening to music (see Table 3). These examples were selected because most can be done while managing a burdensome, chronic illness. Additionally, examples of common negative thoughts were also tailored with end-stage kidney disease in mind. Thought examples like “I am worthless now that I am on dialysis,” “I am a burden to everyone ever since I have been on dialysis,” or “I am sure that and I will never get a kidney transplant.”

The DBD team is currently conducting an open pilot of the treatment program within one university-affiliated dialysis center in Michigan. This pilot provides a preliminary test of DBD’s impact on depressive symptoms, as well as allows the team to get critical feedback from dialysis patients using the program via the User Engagement Scale (O’Brien et al., 2018) and qualitative interviews conducted at the end of treatment. Collectively, this pilot work supports our understanding of preliminary treatment effectiveness as well as treatment satisfaction and engagement, revealing opportunities to improve the program via additional tailoring. The DBD team will also obtain feedback from providers at the dialysis center, with specific attention to the social workers and nurses supporting the brief session check-ins to better understand potential factors impacting the implementation of the DBD program.

Next Steps and Opportunities

The EMW platform has introduced new innovations to technology-assisted CBT programs that have a strong promise and potential to increase the uptake of evidence-based depression treatment. This initial promise notwithstanding, the current EMW platform is the foundation for what promises to be an exciting series of refinements and advancements in the future.

First, the EMW depression treatment programs currently only have one character-driven storyline that provides an entertaining way to deliver core CBT content. Although there was careful attention and intentionality to creating an animated, nonhuman character to increase engagement and relatability for a broad range of users, there are some limitations of only having one character-driven storyline. Building additional storylines with main characters representing diverse identities and positionalities represents important future opportunities to enhance engagement and personalize treatment. For instance, Billi, the main character in our current storyline, identifies as female. There is potential to create main characters who are nonbinary, transgender, identify as male, or identify their gender another way. Additionally, Billi’s story is designed for an adult population. EMW has the potential to create a new story for children and adolescents that would align with their developmental stage and life experiences. There are similar opportunities to create a story specific to older adults experiencing depression, co-occurring health needs, and social isolation.

Second, the EMW platform’s support of low-cost, quick, and easy tailoring allows for the creation of supplemental content related to wellness and quality of life that complements core CBT content. For example, in response to COVID-19, our team has created content introducing a series of evidence-based stress management tools that can be incorporated within each session of our current depression treatment programs. These stress management tools include diaphragmatic breathing, light movement yoga, mindfulness meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation. There is potential to supplement intervention content with other focus areas, such as nutrition education, social skills training, and parenting support.

Third, there is substantial promise to use EMW as a platform to host various CBT programs for different mental health and health conditions (e.g., a transdiagnostic CBT for depression and anxiety, or a behavioral activation program for healthy eating among patients with diabetes). Although EMW began with the development of a depression treatment program, platform innovations such as quick, easy, and low-cost tailoring and content delivery via an entertaining, character-driven storyline, have high relevance for treating a variety of other mental health conditions, such as generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder, and health conditions, such as diabetes and sleep disorders.

Fourth, all of our current EMW-based, tailored depression treatment programs are delivered with human support. Human support for individual, self-guided delivery consists of brief, 5- to 10-minute weekly check-ins that focus on how users are doing, whether they have any questions about the session content, and reviewing homework exercises for the week. Facilitators supporting group-based delivery introduce and support in-session activities, answer questions, and introduce and practice homework exercises. To date, EMW depression treatment programs that are delivered via a fully self-guided approach, without brief human support, have not been explored or tested. We see the need for future work testing EMW-based depression treatment programs offered without brief human support, as well as research testing EMW-based depression treatment programs delivered with human support compared to fully self-guided delivery.

Fifth, EMW is currently only available in English, which limits its reach on a global scale. Given the high worldwide prevalence of depression and its global disease burden, it is our team’s goal to develop translation features within the platform and make the interventions housed on the EMW platform available in many languages.

Finally, there are promising opportunities to incorporate additional technological innovations to allow for user interactivity within the platform. Currently, the in-session activities and homework exercises are completed via a tailored workbook that accompanies each depression treatment program. Our team seeks to improve platform functionality in order to integrate the workbook within the program. This would increase EMW’s ease of use as well as the potential for scalability. This also could enable users to get automated feedback on their workbook exercises directly in the EMW platform. Additionally, there is potential to leverage technology in order to create an artificial intelligence informed digital dialogue agent to engage with and support users throughout each session, particularly in relation to in-session activities and homework planning. Given the persistent shortage of mental health and other health-related providers, minimizing human support needed for T-CBT interventions represents an important strategy to increase access to needed care, particularly among underrepresented and underserved groups in the mental health system.

Conclusion

Depression prevalence rates were high prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and have increased as a result of the pandemic. Despite the substantial need for depression treatment, unacceptable treatment access disparities remain. Although Digital Mental Health Interventions (DMHIs), including T-CBT, have been found effective for treating depression, they are not widely available, and substantial access challenges remain. Two primary factors driving these access challenges relate to: (1) limited user engagement with and completion of existing T-CBT programs for depression and (2) the inability to tailor existing T-CBTs for depression for specific target populations, contexts, or settings. Bridging the mental health treatment gap is a social justice issue that requires mental health intervention and implementation researchers to innovatively leverage technology in ways that align with user preferences for engagement as well as deliver intervention content in ways that are relevant and align with users lived experiences and realities. Entertain Me Well (EMW), a new web-based platform delivering CBT for depression, takes an important step in addressing these known access barriers. EMW offers three critical innovations intentionally designed to enhance user engagement: (a) entertaining delivery of intervention content through a character-driven storyline, (b) quick and easy, low-cost treatment tailoring while retaining core CBT elements, and (c) presentation of content in a simple, straightforward manner. EMW’s innovations hold promise for extending treatment access in a way that is acceptable and sustainable across diverse populations, contexts, and settings. Preliminary findings reported elsewhere, suggest that EMW engages users and results in a reduction of depressive symptoms. Future work will focus on continued testing of EMW depression treatment programs through both single-armed pilots and randomized controlled trials, as well as making platform improvements that have the potential to further enhance engagement and reach of depression treatment programs. Overall, we consider EMW a “first-of-its-kind” T-CBT platform, which is engaging and entertaining, tailorable for different populations and settings, has major advantages for uptakes, and carries promising potentials to interact with advanced technologies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [K01MH110605]; and the University of Michigan Interprofessional Exchange (IP-X) Research Stimulus Program.

References

- Alang S.M. Sociodemographic disparities associated with perceived causes of unmet need for mental health care. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2015;38:293. doi: 10.1037/prj0000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Basu A., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., English C.L., Newby J.M. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable, and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2018;55:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PloS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers C.R., Sorrell J.T., Thorp S.R., Wetherell J.L. Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:8–17. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J.S. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2011. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M., Jr, Castro F.G., Strycker L.A., Toobert D.J. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:196. doi: 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin J.N., Bellamy G.R., Ferdinand A.O., Vuong A.M., Kash B.A., Schulze A., Helduser J.W. Rural healthy people 2020: New decade, same challenges. The Journal of Rural Health. 2015;31:326–333. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody D.J., Pratt L.A., Hughes J. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2018. Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013-2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A.C., Chapman J.E., Forman E.M., Beck A.T. The empirical status of cognitive-behavior therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh K. Geographic inequity in the availability of cognitive behavioural therapy in England and Wales. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2014;42:497–501. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creedon T.B., Cook B.L. Access to mental health care increased but not for substance use, while disparities remain. Health Affairs. 2016;35:1017–1021. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner K.O., Copeland V.C., Grote N.K., Koeske G., Rosen D., Reynolds C.F., III, Brown C. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: The impact of stigma and race. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:531–543. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;59:614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P.W., Druss B.G., Perlick D.A. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Supplement. 2014;15:37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Berking M., Andersson G., Quigley L., Kleiboer A., Dobson K.S. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;58:376–385. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Cipriani, Furukawa Effectiveness and acceptability of cognitive behavioral therapy delivery formats in adults with depression: A network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019:700–707. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., Weaver M.D., Robbins R., Facer-Childs E.R., Barger L.K., Czeisler C.A., Howard M.E., Rajaratnam S.M. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom M.F. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(Supplement 4):13614–13620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320645111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D., Cristea I., Hofmann S.G. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018;9:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong H., Broadbent H., Schmidt U. A systematic review of dropout from treatment in outpatients with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:635–647. doi: 10.1002/eat.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery L., Jeffery D., Schauman O., Williams P., Farrelly S., Bonnington O., Gabbidon J., Lassman F., Szmukler G., Thornicroft G., Clemet S., MIRIAD Study Group Stigma-and non-stigma-related treatment barriers to mental healthcare reported by service users and caregivers. Psychiatry Research. 2015;228:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorow M., Löbner M., Pabst A., Stein J., Riedel-Heller S.G. Preferences for depression treatment including technology-assisted interventions: Results from a large sample of primary care patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018;9:181. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M., Sherbourne C.D., Liao D., Wells K.B. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(8):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Zarski A.C., Christensen H., Stikkelbroek Y., Cuijpers P., Berking M., Riper H. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PloS One. 2015;10:e0119895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D., Hunt J., Speer N., Zivin K. Mental health service utilization among college students in the United States. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199:301–308. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182175123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farvolden P., Denisoff E., Selby P., Bagby R.M., Rudy L. Usage and longitudinal effectiveness of a Web-based selfhelp cognitive behavioral therapy program for panic disorder. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7:e7. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E., Salem D., Swift J.K., Ramtahal N. Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: Magnitude, timing, and moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:1108. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J., Torous J., Nicholas J., Carney R., Pratap A., Rosenbaum S., Sarris J. The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:287–298. doi: 10.1002/wps.20472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich M.J. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA. 2017;317:1517. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S., Moran E., Duran N., Jenders R.A. Vol. 2013. American Medical Informatics Association; 2013. Using animation as an information tool to advance health research literacy among minority participants; p. 475. (AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg P.E., Fournier A.A., Sisitsky T., Pike C.T., Kessler R.C. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010) The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–162. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, Compton, Blanco, Colpe Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of U.S. adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Affairs. 2017 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans E., Hiller W. Effectiveness of and dropout from outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for adult unipolar depression: A meta-analysis of nonrandomized effectiveness studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:75. doi: 10.1037/a0031080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(10):1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D.S., Sarvet A.L., Meyers J.L., Saha T.L., Ruan W.J., Stohl M., Grant B.F. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:336–346. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle J.A., Bybee D., Steinberger E., Laviolette W.T., Weaver A., Vlnka S., Golenberg Z., Levine D.S., Heimberg R.G., O’Donnell L.A. Work-related CBT versus vocational services as usual for unemployed persons with social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;63:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S.G., Asnaani A., Vonk I.J., Sawyer A.T., Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:427–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J.B., Eisenberg D., Lu L., Gathright M. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care utilization among US college students: Applying the institution of medicine definition of health care disparities. Academic Psychiatry. 2015;39:520–526. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.E., Brems C., Warner T.D., Roberts L.W. Rural–urban health care provider disparities in Alaska and New Mexico. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:504–507. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-0001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle-Forbes S.M., Meis L.A., Spoont M.R., Polusny M.A. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2016;8:107. doi: 10.1037/tra0000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K.R., Walters E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Koretz D., Merikangas K.R., Rush A.J., Walters E.E., Wang P.S. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., McGonagle K.A., Zhao S., Nelson C.B., Hughes M., Eshleman S., Wittchen H.-U., Kendler K.S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles S.E., Lovell K., Bower P., Gilbody S., Littlewood E., Lester H. Patient experience of computerised therapy for depression in primary care. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs P., Prochaska J.O., Rossi J.S. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Theng Y.-L., Foo S. Game-based digital interventions for depression therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, & Social Networking. 2014;17:519–527. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2020:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak M.D., Lage M.J., Dunayevich E., Russell J.M., Bowman L., Landbloom R.P., Levine L.R. The cost of treating anxiety: The medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;2:178–184. doi: 10.1002/da.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R.K., Whitton S.W., Peckham A.D., Welge J.A., Otto M.W. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74:595–602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R., Jorm A.F. Trends in psychological distress, depressive episodes and mental health treatment-seeking in the United States: 2000–2012. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;174:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R., Olfson M., Sampson N.A., Jin R., Druss B., Wang P.S., Wells K.B., Pincus H.A., Kessler R.C. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison L.G. Theory-based strategies for enhancing the impact and usage of digital health behaviour change interventions: A review. Digital Health. 2015;1 doi: 10.1177/2055207615595335. 2055207615595335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher C.E., Given B.A., Ostroff J.S. Barriers to mental health service use among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2015;24:50–59. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby J.M., Twomey C., Li S.S.Y., Andrews G. Transdiagnostic computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;199:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar S.M., Benac C.N., Harris M.S. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:673. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien H.L., Cairns P., Hall M. A practical approach to measuring user engagement with the refined user engagement scale (UES) and new UES short form. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2018;112:28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M., Blanco C., Marcus S.C. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176:1482–1491. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcesepe A.M., Cabassa L.J. Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40:384–399. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B.A., Medina T.R., Martin J.K., Long J.S. The “backbone” of stigma: Identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:853–860. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2019a). Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/.

- Pew Research Center (2019b, June 12). Mobile Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/.

- Rahman Regulating Informational Infrastructure: Internet Platforms as the New Public Utilities. Georgetown Law and Technology Review. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Richards D., Richardson T. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan K., McAlpine D.D., Blewett L.A. Access and cost barriers to mental health care, by insurance status, 1999–2010. Health Affairs. 2013;32:1723–1730. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P.P., Craske M.G., Stein M.B., Sullivan G., Bystrisky A., Katon W., Golinelli D., Sherbourne C.D. A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:290–298. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor S., Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health. 2020;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A., Johnco C., Lewin A.B., McBride N.M., Storch E.A. Barriers to access and participation in community mental health treatment for anxious children. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;196:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner E.A., Rommetveit R. The acquisition of sentence voice and reversibility. Child Development. 1967:649–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey C., O’Reilly G., Meyer B. Effectiveness of an individually-tailored computerised CBT programme (Deprexis) for depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2017;256:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ballegooijen W., Cuijpers P., Van Straten A., Karyotaki E., Andersson G., Smit J.H., Riper H. Adherence to Technology-assisted and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R., Gilbody S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: A systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.S., Berglund P.A., Olfson M., Kessler R.C. Delays in initial treatment contact after first onset of a mental disorder. Health Services Research. 2004;39:393–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.S., Simon G., Kessler R.C. The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2003;12:22–33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A., Hahn J., Tucker K.M., Bybee D., Yugo K., Johnson J.M., Buccalo N., Pfeiffer P., Kilbourne A., Himle J.A. Depressive symptoms, material hardship, barriers to help seeking, and receptivity to church-based care among recipients of food bank services in rural Michigan. Social Work in Mental Health. 2020;18:515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A., Himle J., Elliott M., Hahn J., Bybee D. Rural residents’ depressive symptoms and help-seeking preferences: Opportunities for church-based intervention development. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019;58:1661–1671. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A., Zhang A., Landry C., Hahn J., McQuown L., Harrington M.M.…Himle J.A. Raising Our Spirits Together: Results of an open pilot trial of an entertaining, online group-based CBT for depression delivered in rural areas during COVID-19. Research on Social Work Practice. 2021;10497315211044835 [Google Scholar]

- Webb C.A., Rosso I.M., Rauch S.L. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression: Current progress and future directions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2017;25:114–122. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C.J., Cottone R.R. Using cognitive behavior therapy in clinical work with African American children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2013;41:130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wright J.H., Owen J.J., Richards D., Eells T.D., Richardson T., Brown G.K., Barrett M., Rasku M.A., Polser G., Thase M.E. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2019;80:18r12188. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18r12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Bornheimer L.A., Weaver A., Franklin C., Hai A.H., Guz S., Shen L. Cognitive behavioral therapy for primary care depression and anxiety: A secondary meta-analytic review using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2019;42:1117–1141. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A., Weaver, A., Walling, E., Zebrack, B., Levin, N.J., Stuchell, B., & Himle, J. (submitted for publication). Evaluating an engaging and coach-assisted online cognitive behavioral therapy for depression among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A pilot feasibility trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]