Abstract

Rationale

Whether patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) may benefit from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) compared with conventional invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) remains unknown.

Objectives

To estimate the effect of ECMO on 90-day mortality versus IMV only.

Methods

Among 4,244 critically ill adult patients with COVID-19 included in a multicenter cohort study, we emulated a target trial comparing the treatment strategies of initiating ECMO versus no ECMO within 7 days of IMV in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (PaO2/FiO2 < 80 or PaCO2 ⩾ 60 mm Hg). We controlled for confounding using a multivariable Cox model on the basis of predefined variables.

Measurements and Main Results

A total of 1,235 patients met the full eligibility criteria for the emulated trial, among whom 164 patients initiated ECMO. The ECMO strategy had a higher survival probability on Day 7 from the onset of eligibility criteria (87% vs. 83%; risk difference, 4%; 95% confidence interval, 0–9%), which decreased during follow-up (survival on Day 90: 63% vs. 65%; risk difference, −2%; 95% confidence interval, −10 to 5%). However, ECMO was associated with higher survival when performed in high-volume ECMO centers or in regions where a specific ECMO network organization was set up to handle high demand and when initiated within the first 4 days of IMV and in patients who are profoundly hypoxemic.

Conclusions

In an emulated trial on the basis of a nationwide COVID-19 cohort, we found differential survival over time of an ECMO compared with a no-ECMO strategy. However, ECMO was consistently associated with better outcomes when performed in high-volume centers and regions with ECMO capacities specifically organized to handle high demand.

Keywords: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, emulated target trial

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is currently used for patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) related to acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, whether patients with COVID may benefit from ECMO compared with mechanical ventilation associated with other adjunct therapies such as prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade remains unknown, as no randomized controlled trial has been performed in that population.

What This Study Adds to the Field

In an emulated trial on the basis of a nationwide COVID-19 cohort, we found differential survival over time of an ECMO compared with a non-ECMO strategy for COVID-19. However, ECMO was consistently associated with better outcomes when performed in high-volume centers, in regions with ECMO capacities specifically organized to handle high demand, in patients who are profoundly hypoxemic, and if initiated early after intubation

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used for patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) related to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1–4). High-volume ECMO centers and large ECMO networks reported similar survival for these patients compared with patients who are ECMO-supported with non–COVID-19–related ARDS (5, 6). Two randomized controlled trials (5, 7), a post hoc Bayesian analysis (8), and a systematic review and individual meta-analysis (9) all consistently supported the use of venovenous ECMO in adults with severe ARDS treated in expert centers. Whether patients with COVID may benefit from ECMO compared with mechanical ventilation associated with other adjunct therapies such as prone positioning and neuromuscular blockades remains unknown, as no randomized controlled trial has been performed in that population. However, a recent multicenter cohort study of adults critically ill with COVID-19 in the United States found that patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure treated with ECMO in the first 7 days of ICU admission had a considerable reduction in mortality compared with those not treated with ECMO (10).

We aimed to use the COVID-ICU cohort database containing prospectively collected demographic and clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients admitted to ICUs for severe COVID-19 in France, Belgium, and Switzerland, between February and May 2020 (11) to further examine the impacts of ECMO on survival in patients with COVID-19–related severe ARDS. We used the target trial emulation framework and causal inference methodology (12) to compare the treatment strategies of initiating ECMO versus not initiating among patients who have started invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) within the past 7 days.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

All consecutive patients over 16 years of age admitted to the participating ICUs between February 25, 2020, and May 4, 2020, with laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection were included. Details of the data collected daily in the first 14 days from admission and then on Days 28, 45, 60, and 90 have been described elsewhere (11) and are briefly summarized below. Beyond baseline demographic and clinical information and ICU severity scores, the study investigators recorded time-updated information, including the use of ECMO, respiratory support, arterial blood gas, standard laboratory parameters, and use of adjuvant therapies for ARDS. The investigators also recorded information on ECMO-related complications (see online supplement) and in-ICU organ dysfunction. Patient vital status (with the exact date of death) was collected by study investigators 90 days after ICU admission, with a call to the patients or their relatives if they were discharged from the hospital before Day 90. This study received approval from the ethical committee of the French Intensive Care Society (CE-SRLF 20-23) and Swiss and Belgium ethical committees following local regulations.

Descriptive Statistics of Individuals who Initiated ECMO

A descriptive analysis of the characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients aged ⩽70 years old, with SAPS II 90 or less, and who received ECMO within 14 days of ICU admission (other eligibility criteria are defined in the next subsection) was performed. This was done overall and according to their survival status at 90 days after ECMO initiation.

We used the target trial emulation framework, which involves specifying the protocol for a hypothetical randomized trial and then emulating this using the available observational data described above. The components of the target trial and how it is emulated are summarized below. Full characteristics of a hypothetical target trial and our emulated trial using the COVID-ICU cohort are provided in Table E1 in the online supplement.

Eligibility Criteria and Treatment Strategies of Interest

The first step of any emulated trial is to define the target trial that would have been conducted if randomization was feasible (13). On the basis of the inclusion criteria of the EOLIA (ECMO to Rescue Lung Injury in Severe ARDS) trial (5), our eligibility criteria for this study were: patients in ICU and on IMV, with time spent in ICU ⩽14 days (before ECMO initiation) and time spent on IMV ⩽7 days, age ⩽70 years, SAPS (Simplified Acute Physiology Score) II at ICU admission 90 or less, and PaO2/FiO2 < 80 mm Hg or PaCO2 ⩽ 60 mm Hg. The lowest PaO2 value (with its corresponding FiO2) on the day of ECMO initiation/noninitiation or the day before was used. Therefore, a target trial would have aimed to compare strategies of initiating ECMO versus not initiating ECMO in patients with severe ARDS among patients meeting the above criteria. All patients in the COVID-ICU study were considered potential candidates for ECMO, as ECMO was available in all centers, including patients through mobile ECMO teams and retrieval into the ECMO center after cannulation. The organization of ECMO mobile teams and the increase in the offer during that period in Paris and its greater area (Région Ile de France) have been thoroughly described elsewhere (4). An ECMO center that had performed more than 30 venovenous ECMO cases in 2019 was considered a high-volume center (4, 14).

Endpoints and Estimands

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Overall survival time was defined as the time in days from the time of meeting eligibility criteria (i.e., time of inclusion in a given sequential “trial”; see the next subsection) up to death. We applied administrative censoring at 90 days. The primary estimands of interest were the marginal survival probabilities up to 90 days under each of the two treatment strategies (i.e., what would have been the survival if all patients meeting the eligibility criteria had started ECMO compared with if none of them had) and the corresponding risk difference. The secondary estimand was the hazard ratio (HR) associated with ECMO initiation conditional on variables measured at the time of meeting eligibility criteria.

Analysis Using Sequential Trials Approach: Data Set-up

Data from the COVID-ICU cohort were used to emulate the target trial specified above. The estimands specified in the previous section could be estimated using observational data under several assumptions: conditional exchangeability, positivity, consistency, and no interference (15).

Eligibility criteria were checked daily for each patient, and individuals in the study cohort could meet the eligibility criteria on several days. We took advantage of this feature in our analysis by making use of the “sequential trials” causal inference approach (10, 16, 17) (see Figure E1). Day 1 denoted the first day of IMV. An “emulated trial” data set was created for each day between Day 1 and Day 7 from IMV initiation, as follows. Among patients who met eligibility criteria on Day 1, those treated with ECMO were following treatment strategy (i) and are referred to as the treatment group. The remaining patients who did not initiate ECMO on Day 1 were following treatment strategy (ii) on that day and are referred to as the control group. Some individuals in the control group on Day 1 subsequently initiated ECMO, therefore deviating from treatment strategy (ii). They were artificially censored the day before initiating ECMO. This process was repeated for each day from Day 2 to Day 7 for alive patients meeting the eligibility criteria and not yet treated by ECMO. A given patient could be included in the control group in several trials but only once in the treatment group. Days 1–7 were called landmark time points. The final analysis dataset (referred to as the “pooled” dataset) was obtained by pooling the data from the seven sequential trials.

Analysis Using Sequential Trials Approach: Estimation

To estimate the effect of ECMO use on survival, we needed to account for confounding in this association. We also needed to account for the dependent censoring created from our artificial censoring of patients in the control group at the start of a given trial who deviated from the treatment strategy (ii) when ECMO was initiated. These were respectively handled in the analysis by adjustment for confounders measured at the start of each “trial” and by use of time-dependent inverse probability of censoring (IPC) weights. The following prespecified covariates were used to adjust for confounding: age, sex, inclusion period (before or after March 31, 2020), body mass index (< or ⩾30 kg/m−2), time from first symptoms to ICU admission (⩽ or >7 days), time since IMV initiation (< or ⩾6 days), diabetes mellitus, treated hypertension, immunodeficiency, PaO2/FiO2 (< or ⩾65 mm Hg; PaO2/FiO2 <65 mm Hg was the first quartile of PaO2/FiO2 and therefore identified the most hypoxemic patients in our population), PaCO2 (< or ⩾60 mm Hg), bacterial co-infection, renal and cardiovascular components of the SOFA score (⩽ or >2), any prone position, neuromuscular blockades, and/or corticosteroids use before ECMO initiation/noninitiation (details in the online supplement). Of these covariates, PaO2/FiO2, the SOFA score, PaCO2, bacterial co-infection, rescue therapies, and corticosteroid use varied over time during the follow-up in the emulated trial. These covariates were selected a priori on the basis of known prognostic factors of COVID-19 ARDS (11, 18) and severe ARDS rescued by ECMO (19, 20). The analysis used a Cox regression fitted to the pooled dataset, using the time-dependent IPC weights (see below). The model included ECMO status at the start of the trial (i.e., treatment or control group) as a covariate, plus measures of all covariates (as recorded at the start of each trial for time-varying covariates). The coefficient for ECMO status was assumed to be identical across the seven trials. We allowed a time-varying coefficient for ECMO (i.e., nonproportional hazards). A smooth plot of the Schoenfeld residuals was used to choose a suitable functional form for the log HR over time (21).

IPC weighting was used to adjust for the artificial informative censoring of patients in the control group who initiated ECMO later during follow-up (the “protocol deviation”). Cox regression was used to estimate the denominator of the weights, which was the estimated probability of not being censored up to a given follow-up time conditional on the patient characteristics at each landmark time point and during ICU follow-up, using the same set of covariates as in the main analysis. The weights were stabilized using the estimated probability of not being censored up to a given time obtained from the Kaplan-Meier estimator in the numerator. Individual weights were estimated separately in each trial.

Marginal survival curves for treated and control groups were estimated from the regression coefficients, and cumulative baseline hazard was estimated from the weighted Cox regression analysis (16, 22). As the pooled dataset included several copies of the same individual that did not correspond to any well-defined population, survival curves were estimated on an evaluation cohort composed of unique individuals meeting the eligibility criteria at any time, with covariates set to their values at the first time of meeting the eligibility criteria (which may be trials starting on different days for different individuals). For each patient in the evaluation cohort, we estimated two sets of survival probabilities: the probabilities if they had initiated ECMO and the probabilities if they had not. We then calculated the empirical average of these predicted survival probabilities. Our focus was on the time horizon of 90 days, but we also repeated this on each day of follow-up to create estimated marginal (population average for the evaluation cohort) survival curves under the two treatment strategies. Because the same individual may appear in more than one trial and the use of IPC weighting, model-based variance estimators were not appropriate. Nonparametric bootstrap was used to estimate 95% normal-based confidence intervals for marginal survival probabilities and HRs (with 200 bootstrap replications). The estimation of weights and the multivariable Cox model were repeated in each bootstrap sample.

Missing Data

Multiple imputations using chained equations were used to replace missing values on covariates, assuming that data are missing at random. Besides, there was no missing data regarding ECMO exposure. Further details on our multiple imputations are provided in the online supplement.

Sensitivity Analyses (SAs)

We performed several SAs. First, by considering the complete case sample without any missing data imputation (SA1). Second, by performing the analysis without artificial censoring of “crossed-over” control patients (and thus without IPC weighting) (SA2). Third, by using more stringent eligibility criteria: patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 80 mm Hg or PaCO2 ⩾ 60 mm Hg and having received at least one prone position session (SA3), and fourth in the most hypoxemic patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 65 mm Hg (SA4).

To allow that ECMO effects may vary over the landmark times, we performed subgroup analyses by restricting the analysis to the first four trials (Days 1 to 4) (SA5) and the last three trials (Days 5 to 7) (SA6).

To explore the effect variation of ECMO between centers, analysis was restricted to centers from the greater Paris region (Région Ile de France), where a specific (re)organization of mobile ECMO teams was set up during that period (4) (SA7), and by separating high and low ECMO volume centers (SA8).

Lastly, marginal survival curves were re-estimated using a multivariable Cox model stratified (instead of adjusted) on the ECMO initiation group (i.e., with separate baseline hazards in the treated and control groups). Similar to the time-varying coefficient method, this allowed to completely relax the proportional hazards assumption on ECMO initiation (SA9) at the cost of preventing the estimation of an HR associated with ECMO.

Results

Study Population and Characteristics of Patients Before ECMO Initiation

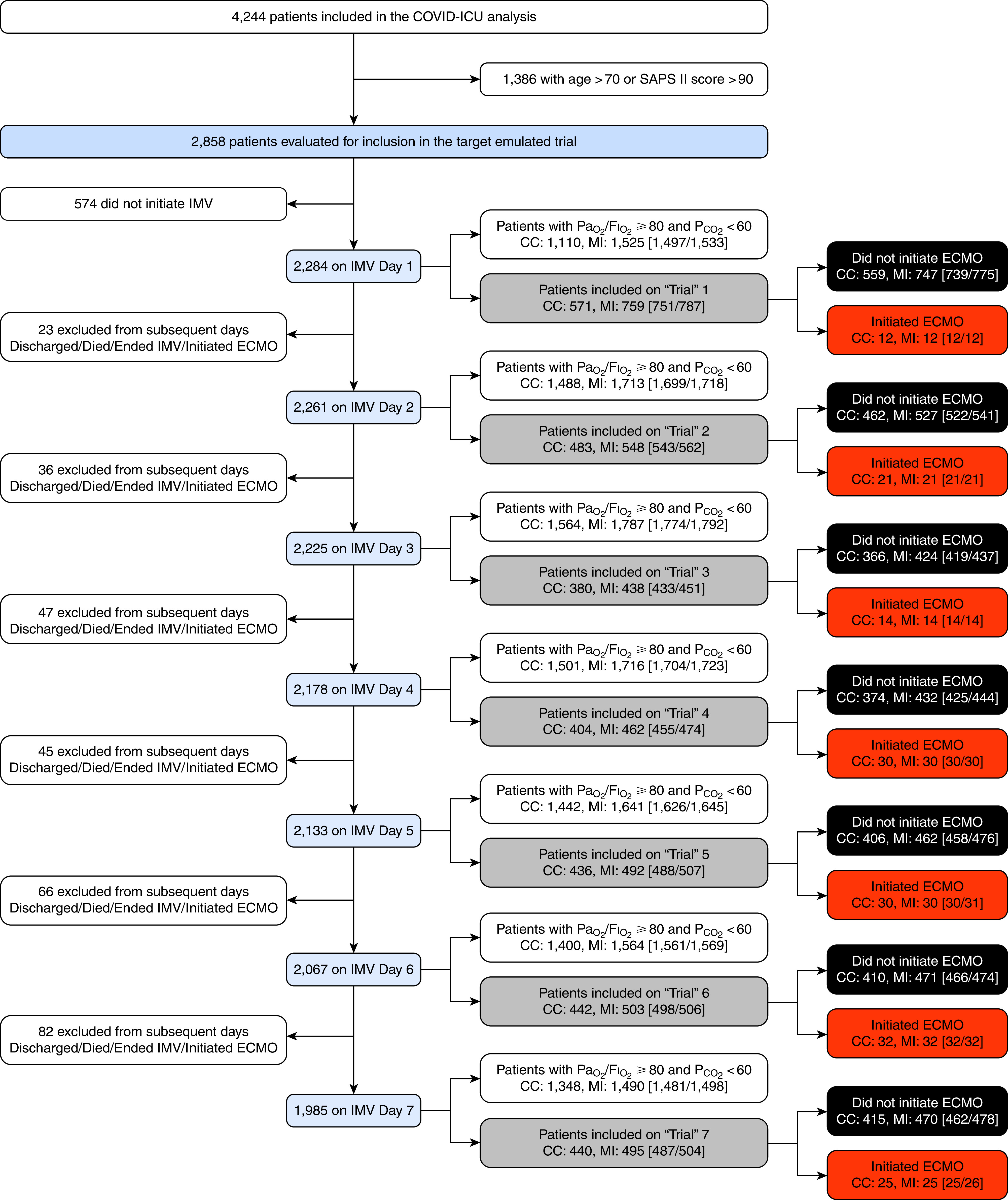

Among 4,244 patients included in the analysis, 2,858 (67%) met the criteria for inclusion in the target trial (of age ⩽70 years old and SAPS II 90 or less) (Figure 1). A total of 269 (9%) patients received ECMO within 14 days of ICU admission. The main characteristics of these patients on ECMO according to their survival status 60 days after ECMO initiation are presented in Table 1. One hundred nineteen (44%) patients died. IMV was started at a median time of 0 (interquartile range, 0–1) days from ICU admission, and ECMO was initiated 6 (4–8) days after IMV started. Median pre-ECMO PaO2/FiO2 was 62 (53–74), whereas PaCO2 was 58 (50–68) mm Hg. Noticeably, PaO2/FiO2 was less than 80 in 81% of the patients. Prone positioning and continuous neuromuscular blockade before ECMO were used in 240 (89%) and 260 (97%) patients, respectively.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. The flowchart describes at each landmark time (defined as the first seven days from invasive mechanical ventilation initiation) the number of patients considered for eligibility, the number of patients who met the eligibility criteria of the emulated trial, and the number of patients who initiated extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). One patient can contribute several times to the “Did not initiate ECMO” group but only once to the “initiated ECMO” group. CC = complete cases; COVID-ICU = large French cohort of 4,244 critically ill patients admitted in intensive care unit for coronavirus disease; IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation; MI = number of cases after multiple imputations of missing data (median [min/max]); SAPS II = simplified acute psychology score.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics before Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation According to Their Survival Status 60 Days after Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Initiation

| 60 d After ECMO Initiation Survival Status |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing values, n | All Patients (N = 269) | Alive (n = 151) | Dead (n = 118) | P value | |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | — | 54 (46–59) | 53 (43.5–58) | 55 (50–62) | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | — | 207 (77) | 109 (72) | 98 (83) | 0.036 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | — | 30 (27–34) | 30 (28–35) | 29 (27–34) | 0.322 |

| ⩾30 | — | 139 (54) | 84 (58) | 55 (49) | 0.156 |

| SAPS II score, median (IQR) | — | 42 (31–57) | 45 (31–55) | 41 (30–59) | 0.780 |

| SOFA score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 14 | 8 (4–12) | 8 (4–12) | 8 (5–11) | 0.945 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | — | — | — | — | 0.685 |

| Before March 31, 2020 | — | 149 (55) | 82 (54) | 67 (57) | — |

| After April 1, 2020 | — | 120 (45) | 69 (46) | 51 (43) | — |

| Treated hypertension, n (%) | 1 | 84 (31) | 47 (31) | 37 (31) | 0.997 |

| Known diabetes, n (%) | 3 | 63 (24) | 29 (19) | 34 (29) | 0.068 |

| Time between (d), median (IQR) | — | — | — | — | — |

| First symptoms to ICU admission | 19 | 10 (7–13) | 10 (7–13) | 9 (7–13) | 0.975 |

| ICU admission to invasive MV | — | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0.030 |

| Invasive MV to ECMO | — | 6 (4–8) | 5 (3–7) | 6 (5–9) | <0.001 |

| Before ECMO | |||||

| VT (ml/kg PBW), median (IQR) | 15 | 5.1 (3.0–6.0) | 5.2 (3.3–6.0) | 4.8 (3.1–6.0) | 0.474 |

| Set PEEP (cm H2O), median (IQR) | 2 | 14 (12–15) | 14 (12–15) | 14 (12–16) | 0.707 |

| Plateau pressure (cmH2O), median (IQR) | 17 | 30 (28–33) | 30 (28–33) | 31 (28–34) | 0.327 |

| Driving pressure (cmH2O),* median (IQR) | 10 | 18 (15–24) | 18 (15–23) | 19 (15–24) | 0.350 |

| Static compliance (ml/cmH2O), median (IQR) | 15 | 18 (12–25) | 19 (14–25) | 17 (11–25) | 0.264 |

| Cardiovascular SOFA score, n (%) | 12 | — | — | — | 0.177 |

| 0–2 | — | 101 (39) | 63 (43) | 38 (35) | — |

| 3–4 | — | 156 (61) | 84 (57) | 72 (65) | — |

| Renal SOFA score, n (%) | 15 | — | — | — | 0.397 |

| 0–2 | — | 212 (83) | 126 (85) | 86 (81) | — |

| 3–4 | — | 42 (16) | 22 (15) | 20 (19) | — |

| Renal replacement therapy | — | 44 (16) | 18 (12) | 26 (22) | 0.026 |

| Blood gases, median (IQR) | — | — | — | — | — |

| pH | 3 | 7.30 (7.25–7.36) | 7.31 (7.26–7.37) | 7.29 (7.22–7.35) | 0.005 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 6 | 58 (50–68) | 56 (48–67) | 59 (53–72) | 0.006 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 5 | 62 (53–74) | 65 (52–76) | 61 (54–70) | 0.215 |

| HCO3, mmol/L | 3 | 27 (23–30) | 26 (23–30) | 27 (23–31) | 0.365 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 4 | 2 (1.6–2.4) | 2 (1.6–2.5) | 2 (1.6–2.4) | 0.818 |

| Bacterial co-infection, n (%) | — | 90 (33) | 49 (32) | 41 (35) | 0.692 |

| Rescue therapies, n (%) | |||||

| Prone position | — | 240 (89) | 133 (88) | 107 (91) | 0.495 |

| Continuous neuromuscular blockade | — | 260 (97) | 149 (99) | 111 (94) | 0.045 |

| Nitric oxide | — | 135 (50) | 70 (46) | 65 (55) | 0.155 |

| Corticosteroids† | — | 59 (22) | 31 (21) | 28 (24) | 0.529 |

Definition of abbreviations: ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR = interquartile range; MV = mechanical ventilation; PBW = predicted body weight; PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure; SAPS = Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SOFA = Sequential Organ Function Assessment.

Defined as plateau pressure − PEEP.

No distinction between corticosteroid types, neither their dose nor the reason for initiation were made.

Management of ECMO and Outcomes

One hundred and eighty-four (68%) patients were proned on ECMO (Table 2). The median ECMO duration was 11 (6–17) days in the ECMO population and 12 (7–20) days in survivors. Noticeably, ECMO durations were 13 (7–20) and 10 (5–17) days in the high- and low-volume centers, respectively (Table E2). Median ICU and hospital length of stay were 31 (22–50) and 42 (28–63) days among survivors, respectively. Among the survivors 60 days after ECMO initiation, 6 (4%), 26 (17%), and 32 (21%) patients were still on ECMO, on IMV, or in the ICU, respectively. The main in-ICU complications were ventilator-associated pneumonia (64%), the need for renal replacement therapy (40%), and major bleeding (39%).

Table 2.

Management, Complications, and Outcomes of the Patients during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation According to Their Survival Status 60 Days After Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Initiation

| 60-D after ECMO Initiation Survival Status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (N = 269) | Alive (n = 151) | Dead (n = 118) | P value | |

| First 48 hr on ECMO | ||||

| VT (ml/kg PBW), median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.9–4.0) | 3.0 (2.1–4.1) | 2.5 (1.8–3.6) | 0.012 |

| Set PEEP (cmH2O), median (IQR) | 14 (12–16) | 13 (11–16) | 14 (12–16) | 0.422 |

| Plateau pressure (cmH2O), median (IQR) | 24 (22–27) | 24 (22–26) | 24 (21–28) | 0.503 |

| Driving pressure (cmH2O), median (IQR) | 12 (9–14) | 12 (9–13) | 12 (9.25–14) | 0.432 |

| Prone positioning during ECMO, n (%) | 184 (68) | 110 (73) | 74 (62) | 0.076 |

| Tracheostomy, n (%) | 36 (13) | 28 (19) | 8 (7) | 0.005 |

| Complications within day 60, n (%) | ||||

| Renal replacement therapy | 106 (39) | 49 (32) | 57 (48) | 0.008 |

| Pneumothorax | 15 (6) | 8 (5) | 7 (6) | 0.822 |

| Major hemolysis | 32 (12) | 15 (10) | 17 (14) | 0.261 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 171 (64) | 106 (70) | 65 (55) | 0.011 |

| Major bleeding | 107 (40) | 50 (33) | 57 (48) | 0.012 |

| Intracranial bleeding or hemothorax | 21 (8) | 2 (1) | 19 (16) | <0.001 |

| Thromboembolic complications | 83 (31) | 98 (65) | 88 (75) | 0.088 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 36 (13) | 16 (11) | 20 (17) | 0.129 |

| Proven distal venous thrombosis | 55 (20) | 42 (28) | 13 (11) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 24 (8) | 12 (8) | 12 (10) | 0.526 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | ||||

| On ECMO, d | 11 (6–17) | 12 (7–20) | 9 (5–14) | 0.002 |

| On invasive MV, d | 24 (16–37) | 27 (20–44) | 20 (12–31) | <0.001 |

| In ICU, d | 27 (15–41) | 31 (23–50) | 17 (10–31) | <0.001 |

| In the hospital, d | 30 (16–48) | 43 (28–62) | 20 (12–32) | <0.001 |

| At Day 60, n (%) | ||||

| Still on ECMO | 6 (2) | 6 (4) | 0 | — |

| Still on invasive MV | 26 (10) | 26 (17) | 0 | — |

| Still in ICU | 32 (12) | 32 (21) | 0 | — |

| Still in the hospital | 63 (23) | 63 (42) | 0 | — |

| Discharge alive from the hospital | 88 (33) | 88 (58) | 0 | — |

Definition of abbreviations: ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR = interquartile range; MV = mechanical ventilation; PBW = predicted body weight; PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure.

Effect of ECMO in Patients Included in the Emulated Trial

Among the 2,858 patients included in the above summaries, 2,284 patients received IMV within 14 days after ICU admission (Figure 1). Before imputation of missing data, 1,235 unique patients met the full eligibility criteria of the target emulated trial at least once during the first 7 days of IMV, and, among them, 164 initiated ECMO (Table 3) in 30 ECMO centers. Fifty-nine ECMO patients were treated in three high-volume centers. Their characteristics are reported in Table E2. After imputation of missing data, 1,421 (min/max: 1,414/1,449) unique patients met the full eligibility criteria. The results of the multivariable Cox model estimated in the primary analysis are shown in Table E3. After inspection of Schoenfeld residuals, we chose to introduce a time-varying coefficient associated with ECMO by including an interaction between ECMO status and the square root of time.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Patients Included in the Target Trial Emulation of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation versus No Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

| Unique Patients |

Final Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing values,* n | ECMO (n = 164) | No ECMO (n = 1,071) | ECMO (n = 164) | No ECMO (n = 2,992) | |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | — | 53 (46–59) | 61 (54–66) | 53 (46–58) | 60 (53–66) |

| Male sex, n (%) | — | 130 (79) | 836 (78) | 130 (79) | 2,341 (78) |

| SAPS II score, median (IQR) | — | 41 (31–56) | 36 (29–48) | 41 (31–56) | 37 (29–48) |

| ICU admission | |||||

| Before March 31, n (%) | — | 103 (63) | 727 (68) | 103 (63) | 2,023 (68) |

| After April 1, n (%) | — | 61 (37) | 344 (32) | 61 (37) | 969 (32) |

| Clinical frailty scale, median (IQR) | 499 | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 70 | 30 (27–34) | 29 (26–33) | 30 (27–34) | 30 (26–33) |

| ⩾30, n (%) | — | 89 (56) | 477 (47) | 89 (56) | 1,415 (50) |

| Known diabetes | 11 | 31 (19) | 312 (29) | 31 (19) | 847 (28) |

| Treated hypertension | 13 | 55 (33) | 500 (47) | 55 (33) | 1,379 (46) |

| Bacterial coinfection† | — | 18 (11) | 120 (11) | 56 (34) | 870 (29) |

| Time between | |||||

| First symptoms to ICU admission (d), median (IQR) | 65 | 9 (6–11) | 8 (6–11) | 9 (6–11) | 8 (6–11) |

| ICU admission to invasive MV (h), median (IQR) | — | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Invasive MV and inclusion in the emulation trial (d), median (IQR) | — | — | — | 5 (3–6) | 4 (2–6) |

| Respiratory function‡ | |||||

| PaO2/FiO2, median (IQR) | 239 | 74 (62–126) | 78 (63–143) | 59 (50–67) | 73 (63–107) |

| <80, n (%) | — | 50 (54) | 471 (52) | 156 (95) | 1,905 (64) |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) , median (IQR) | 244 | 44 (40–50) | 43 (37–50) | 58 (51–68) | 60 (46–66) |

| ⩾60, n (%) | — | 8 (9) | 93 (10) | 71 (44) | 1,503 (51) |

| Arterial pH, median (IQR) | 240 | 7.38 (7.32–7.43) |

7.37 (7.31–7.43) |

7.30 (7.24–7.34) |

7.33 (7.27–7.39) |

| <7.25, n (%) | — | 8 (9) | 98 (11) | 44 (27) | 596 (20) |

| VT (ml/kg PBW), median (IQR) | 692 | 5.9 (5.4–6.3) | 6.1 (5.8–6.7) | 5.3 (3.4–6.1) | 6.1 (5.8–6.7) |

| Set PEEP (cmH2O), median (IQR) | 280 | 12 (10–14) | 12 (10–14) | 14 (12–16) | 12 (10–15) |

| Plateau pressure (cmH2O), median (IQR) | 513 | 27 (24-29) | 24 (21–27) | 31 (29–33) | 27 (24–30) |

| Static compliance (ml/cmH2O), median (IQR) | 732 | 27 (17–33) | 32 (22–40) | 18 (13–25) | 27 (19–37) |

| Extra-pulmonary functions‡ | |||||

| Lactate (mmol/l), median (IQR) | 273 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) |

| Cardiovascular SOFA score 3–4, n (%) | 249 | 49 (52) | 507 (57) | 96 (60) | 1,548 (54) |

| Renal SOFA score 3–4, n (%) | 258 | 4 (4) | 75 (9) | 30 (19) | 423 (15) |

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | — | 1 (1) | 33 (3) | 22 (13) | 336 (11) |

| Rescue therapies,† n (%) | |||||

| Prone position | — | 38 (23) | 212 (20) | 156 (95) | 1,907 (64) |

| Neuromuscular blockade | — | 84 (51) | 749 (70) | 162 (99) | 2,742 (92) |

| Nitric oxide | — | 8 (5) | 23 (2) | 89 (54) | 466 (16) |

| Corticosteroids§ | — | 4 (2) | 106 (10) | 30 (18) | 656 (22) |

For definition of abbreviations, see Table 1.

For the unique patients.

Assessed on the day of ICU admission for the unique patients and up to the day of ECMO initiation or noninitiation for the final cohort.

Assessed on the day of ICU admission for the unique patients and the day of ECMO initiation or noninitiation for the final cohort.

No distinction between corticosteroid types, neither their dose nor the reason for initiation were made.

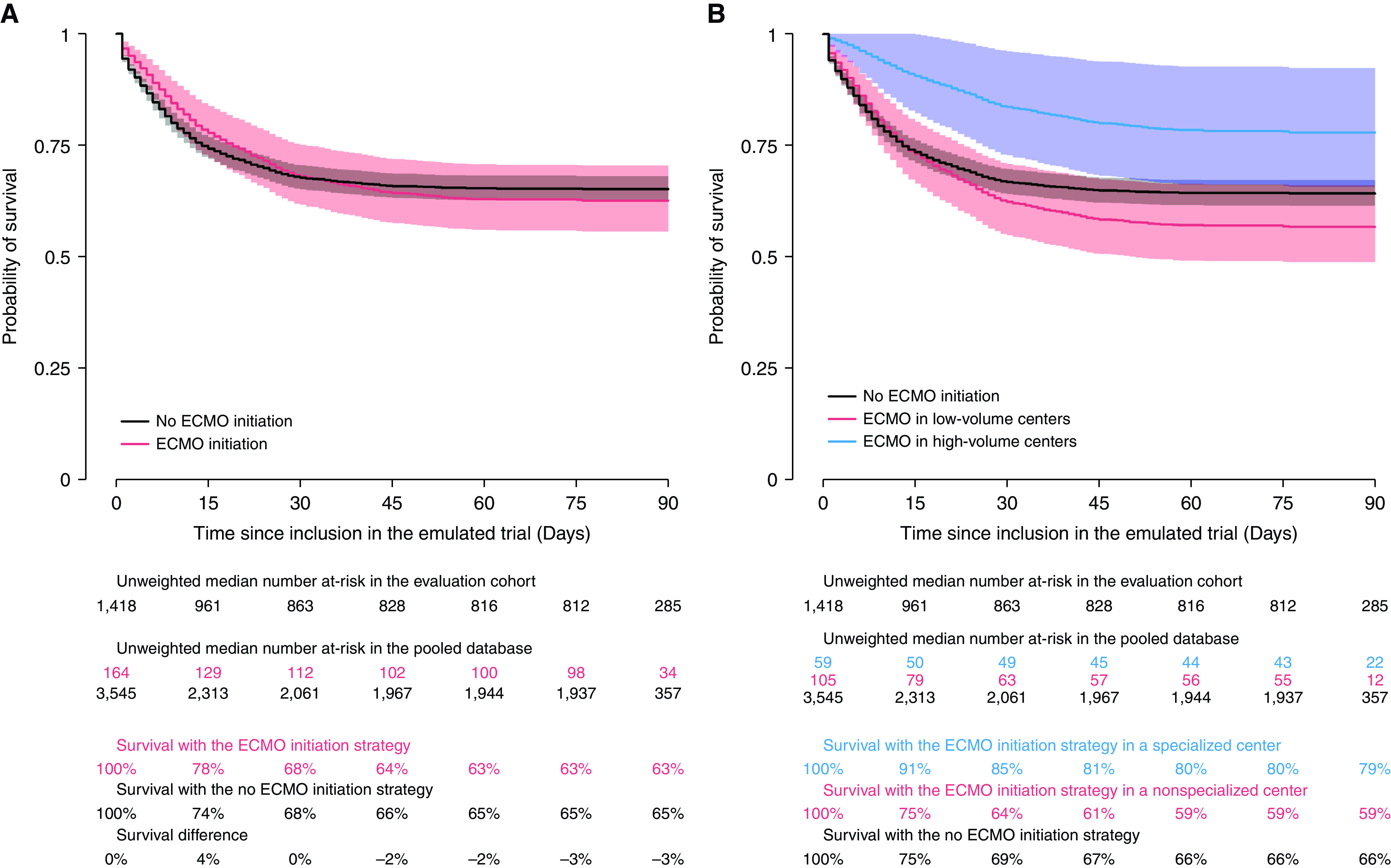

Figure 2 and Table E3 show the estimated marginal survival curves under the two treatment strategies for the evaluation cohort. Under ECMO, the estimated survival probability on Day 7 was 87% (95% confidence interval [CI], 83–92%) compared with 83% (95% CI, 81–85%) under the alternative treatment strategy of not receiving ECMO (risk difference, 4%; 95% CI, 0–9%). Moreover, the survival decreased to 69% (95% CI, 62–76%) on Day 28 with ECMO, compared with 68% (95% CI, 66–71%) without ECMO (risk difference, 1%; 95% CI, −6 to 8%). After Day 40, the estimated survival under ECMO was lower than without ECMO. Finally, at Day 90, survival was 63% (95% CI, 56–70%) and 65% (95% CI, 62–68%) with and without ECMO initiation, respectively (risk difference, −2%; 95% CI, −10% to 5%).

Figure 2.

Marginal survival curves for patients who are (A) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)-treated versus patients treated without ECMO. (B) Patients receiving ECMO treatment in low- or high-ECMO volume centers versus patients treated without ECMO (SA8). The number at-risk is the median number among multiply imputed datasets. The evaluation cohort is composed of unique individuals the first time they meet eligibility criteria. The pooled database is composed of potentially repeated individuals obtained by pooling the data from the seven sequential trials.

Initially, patients who initiated ECMO had a lower conditional hazard of death (HR at Day 1, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.37–0.94). However, after 14 days of follow-up, the HR associated with ECMO initiation increased to 1.14 (95% CI, 0.85–1.54) and was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12–2.46) and 3.00 (95% CI, 1.52–5.94) at Day 28 and Day 60, respectively. Figure E2 shows the estimated HR over time.

Comparable results to the primary analysis were found in analysis with no missing data imputation (Table E4) and when we did not censor patients in the control group who initiated ECMO later during follow-up (Table E5). However, the survival at Day 60 under ECMO was higher when the primary analysis was restricted to patients who had received at least one prone positioning session before ECMO (Table E6). Similarly, the protective effect of ECMO was more pronounced and maintained until Day 90, despite wider CIs, when analyses were limited to patients with PaO2/FiO2 <65 (Table E7) or those with ECMO initiated up to 4 days after intubation (Tables E8 and E9). When the primary analysis was restricted to patients treated in centers of the greater Paris region, or distinguished patients treated in high- versus low-volume ECMO centers, ECMO was consistently associated with a higher survival rate until Day 90 (Tables E10 and E11 and Figures 2B and E2). Specifically, Day 90 survival was 78% (95% CI, 66–92%) for ECMO patients treated in high-volume centers compared to 64% (95% CI, 61–67%) in those not receiving ECMO (risk difference, 14%; 95% CI, 0%–27%) (Table E11 and Figure 2B). Lastly, similar results to the primary analyses were observed in an analysis using a multivariable Cox model stratified on the ECMO initiation group (Table E11).

Discussion

In this multicenter cohort study of 4,244 patients with COVID-19–associated ARDS, 269 were treated with ECMO, and survival 60 days after ECMO initiation was 56%. When restricted to patients who fulfilled eligibility criteria for the emulation target trial in this nationwide COVID-19 cohort, the estimated survival after 90 days for patients initiating ECMO was 63% (95% CI, 56–70%) which was not better compared with patients without ECMO, and the effect of ECMO initiation varied over time. In sensitivity analyses, we observed that ECMO was more effective in patients with more severe hypoxemia (i.e., PaO2/FiO2 ⩽ 65 mm Hg) or if initiated within 4 days after intubation. Interestingly, the benefit of ECMO (vs. no initiation of ECMO) was important and remained constant over the 90 days of follow-up for patients treated in high-volume ECMO centers or in regions where ECMO services were specifically organized in these times of high demand (4).

In our emulated target trial, ECMO was used in 164 out of 1,235 (13%) patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 80 or PaCO2 ⩾ 60 mm Hg within the first 7 days of IMV. However, this incidence was greater than reported in the international LUNGSAFE (Large Observational Study to Understand the Global Impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Failure) study, in which only 6.6% of patients with severe ARDS received ECMO (23). A better knowledge of ECMO indications and widespread use of that technique with mobile ECMO teams could explain this finding. Although international organizations (24, 25) and experts in the field (26, 27) recommended ECMO for patients critically ill with COVID-19, and large ECMO cohorts reported acceptable survival rates (2, 3), the benefit of ECMO in that population remains a matter of debate (28, 29), especially in a context of a pandemic with healthcare resource constraints. Further randomized trials of ECMO in the COVID-19 population would be desirable but are unlikely to be undertaken. Target trial emulation may therefore offer the best evidence on the basis of observational data. When restricting the use of ECMO to EOLIA inclusion criteria (i.e., our eligibility target trial criteria), our 90-day survival for patients initiating ECMO was in accordance with survival reported in experienced ECMO centers (3), international ELSO (Extracorporeal Life Support Organization) cohort (2), or in a recent worldwide meta-analysis (30). However, the effect of ECMO on patient outcomes in the whole cohort varied over time, with a significantly higher survival during the first weeks and a similar or even lower 90-day survival when compared with a strategy not involving ECMO. These results contrast with the constant benefit of ECMO reported in the EOLIA trial (5) and question whether ECMO improves the outcomes of patients with severe COVID-19 related ARDS. Several lines of evidence may explain these findings. First, despite controlling for the carefully chosen baseline and time-dependent prognostic factors, residual confounding may have persisted. Second, specific pathophysiological features of COVID-19 could also explain these results. Indeed, a longer duration of ECMO support and higher rates of ECMO-associated complications, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, major bleeding, oxygenator failure, and thromboembolic events, were reported in patients with COVID-19 compared with the ECMO arm of the EOLIA trial (2, 3, 31–33). This may reflect the longer duration of mechanical ventilation, specific SARS-CoV-2–induced immunoparalysis, the vascular tropism of that disease, and the need for higher anticoagulation. Alternatively, our observation of a decreased benefit of ECMO over time may be explained by the differential survival of patients treated in experienced versus less experienced centers. Indeed, while the survival of patients treated in high-volume centers remained consistently higher than that of non-ECMO patients, it was not different in the initial days of support and then was even lower in patients treated in lower case–volume centers than in the non-ECMO patients (Figure 2B). These results concur with the strong association between higher ECMO volume and lower mortality reported in international non-COVID (14) and COVID cohorts (32), advocating for centralization and regulation of ECMO indications (4).

Our primary results also contrast with other recent observations. In an emulated target trial, Shaefi and colleagues (10) showed a considerably lower risk of death in patients treated with ECMO than those not treated with ECMO. Several factors may explain these differences. First, we used broader eligibility criteria in our trial with the inclusion of patients for up to 14 days in ICU, whereas it was the first 7 days in the study of Schaefi and colleagues (10). A shorter time between intubation or ICU admission and ECMO has been consistently associated with better survival in COVID cohorts (19). Similarly, our subgroup analysis of patients for whom treatment was initiated within the first 4 days of IMV showed a more pronounced protective effect of ECMO. Second, PaO2/FiO2 before ECMO and static compliance of our patients were much lower than those reported by Schaefi and colleagues (10), suggesting a greater respiratory severity. Similarly, the higher use of prone positioning before ECMO reported in our study (89% vs. 71%) reinforces that point by stressing that our population was refractory to (almost) all adjunct therapies before ECMO. The mortality benefit associated with ECMO in severe COVID-19 was also strongly suggested in a series of 90 patients eligible and referred for ECMO to a single center. Mortality was 90% for the 55 (61%) patients who did not receive it because of limited health system capacity, compared with 43% when ECMO capacity was available, despite both groups having young age and limited comorbidities (34).

Despite being on the basis of a large detailed multicenter cohort of patients with a low rate of missing values who were critically ill with COVID-19, the results of this emulated target trial should be interpreted cautiously. First, our inclusion criteria for the emulated target trial were on the basis of PaO2/FiO2 < 80 and/or PaCO2 ⩾ 60 mm Hg at one point (regardless of the timing of adjunct therapies during that day), which contrasts with the EOLIA trial and expert recommendations which advocate considering the duration of time (i.e, >6 h) below a PaO2/FiO2 or above a PaCO2 threshold (5, 35). This difference could have caused a potential bias toward better outcomes for patients not treated with ECMO and hampered exchangeability. Second, the management of patients on ECMO has not been specifically captured by our study and could have differed between ECMO centers. As previously reported in patients with and without COVID (4, 14), venovenous ECMO case volume markedly influenced outcome, with better 90-day survival for patients treated in experienced centers in our study. Third, the use of specific COVID-19 therapies other than dexamethasone was not collected in the COVID-ICU cohort. Fourth, although we carefully designed this emulated trial on the basis of observational data, applied methodological corrections to each identified source of bias, and performed several sensitivity analyses, we cannot exclude residual confounding, which could question the conditional exchangeability assumption. The validity of other assumptions of causal inference may also be discussed. The assumption of no interference (the treatment applied to one unit does not affect the outcome of other units) is likely to be valid in this setting, as the assumption of positivity (by carefully selecting clinically meaningful ECMO eligibility criteria). Assumption of consistency could also have been challenged in a period when hospital strain was intense (34). This potential issue was explored by two sensitivity analyses restricted to centers from the greater Paris region and centers with high ECMO volume, reducing potential heterogeneity in ECMO management. The assumptions surrounding missing data may also not be justified. Lastly, because an increase in mortality in patients with COVID-19 on ECMO has been recently reported during the second surge of the pandemic (i.e., after September 2020) (32, 33, 36), our results might have changed over time with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants associated with more severe forms of ARDS.

Conclusions

We found a differential survival associated with ECMO compared with no ECMO that differs from previous studies in an unselected nationwide cohort of COVID-19 (10, 34). However, an ECMO strategy consistently yielded better outcomes when performed in high volume ECMO centers or in regions where ECMO services had been organized to handle high demand, and if initiated early after intubation and in patients who are profoundly hypoxemic. Our results reinforce the need for regional ECMO networks and advocate for providing ECMO in experienced centers to optimize the outcomes of these patients who are critically ill, especially at times of unprecedented strain on healthcare systems.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the French, Belgian, and Swiss clinical research centers, COVID-ICU investigators, the medical students, Polytechnic University students, and patients involved in the study.

Participating Sites and COVID-ICU Investigators: CHU Angers, Angers, France (Alain Mercat, Pierre Asfar, François Beloncle, Julien Demiselle); APHP - Hôpital Bicêtre, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France (Tài Pham, Arthur Pavot, Xavier Monnet, Christian Richard); APHP - Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Alexandre Demoule, Martin Dres, Julien Mayaux, Alexandra Beurton); CHU Caen Normandie - Hôpital Côte de Nacre, Caen, France (Cédric Daubin, Richard Descamps, Aurélie Joret, Damien Du Cheyron); APHP - Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France (Frédéric Pene, Jean-Daniel Chiche, Mathieu Jozwiak, Paul Jaubert); APHP - Hôpital Tenon, Paris, France (France, Guillaume Voiriot, Muriel Fartoukh, Marion Teulier, Clarisse Blayau); CHRU de Brest – La Cavale Blanche, Brest, France (Erwen L'Her, Cécile Aubron, Laetitia Bodenes, Nicolas Ferriere); Centre Hospitalier de Cholet, Cholet, France (Johann Auchabie, Anthony Le Meur, Sylvain Pignal, Thierry Mazzoni); CHU Dijon Bourgogne, Dijon, France (Jean-Pierre Quenot, Pascal Andreu, Jean-Baptiste Roudau, Marie Labruyère); CHU Lille - Hôpital Roger Salengero, Lille, France (Saad Nseir, Sébastien Preau, Julien Poissy, Daniel Mathieu); Groupe Hospitalier Nord Essonne, Longjumeau, France (Sarah Benhamida, Rémi Paulet, Nicolas Roucaud, Martial Thyrault); APHM - Hopital Nord, Marseille, France (Florence Daviet, Sami Hraiech, Gabriel Parzy, Aude Sylvestre); Hôpital de Melun-Sénart, Melun, France (Sébastien Jochmans, Anne-Laure Bouilland, Mehran Monchi); Élément Militaire de Réanimation du SSA, Mulhouse, France (Marc Danguy des Déserts, Quentin Mathais, Gwendoline Rager, Pierre Pasquier); CHU Nantes - Hôpital Hotel Dieu, Nantes, France (Jean Reignier, Amélie Seguin, Charlotte Garret, Emmanuel Canet); CHU Nice - Hôpital Archet, Nice, France (Jean Dellamonica, Clément Saccheri, Romain Lombardi, Yanis Kouchit); Centre Hospitalier d'Orléans, Orléans, France (Sophie Jacquier, Armelle Mathonnet, Mai-Ahn Nay, Isabelle Runge); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de la Guadeloupe, Pointe-à-Pitre, France (Frédéric Martino, Laure Flurin, Amélie Rolle, Michel Carles), Hôpital de la Milétrie, Poitiers, France (Rémi Coudroy, Arnaud W. Thille, Jean-Pierre Frat, Maeva Rodriguez); Centre Hospitalier Roanne, Roanne, France (Pascal Beuret, Audrey Tientcheu, Arthur Vincent, Florian Michelin); CHU Rouen - Hôpital Charles Nicolle, Rouen, France (Fabienne Tamion, Dorothée Carpentier, Déborah Boyer, Gaetan Beduneau); CHRU Tours - Hôpital Bretonneau, Tours, France (Valérie Gissot, Stéphan Ehrmann, Charlotte Salmon Gandonniere, Djlali Elaroussi); Centre Hospitalier Bretagne Atlantique, Vannes, France (Agathe Delbove, Yannick Fedun, Julien Huntzinger, Eddy Lebas); CHU Liège, Liège, Belgique (Grâce Kisoka, Céline Grégoire, Stella Marchetta, Bernard Lambermont); Hospices Civils de Lyon - Hôpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France (Laurent Argaud, Thomas Baudry, Pierre-Jean Bertrand, Auguste Dargent); Centre Hospitalier Du Mans, Le Mans, France (Christophe Guitton, Nicolas Chudeau, Mickaël Landais, Cédric Darreau); Centre Hospitalier de Versailles, Le Chesnay, France (Alexis Ferre, Antoine Gros, Guillaume Lacave, Fabrice Bruneel); Hôpital Foch, Suresnes, France (Mathilde Neuville, JérômeDevaquet, Guillaume Tachon, Richard Gallot); Hôpital Claude Galien, Quincy sous Senart, France (Riad Chelha, Arnaud Galbois, Anne Jallot, Ludivine Chalumeau Lemoine); GHR Mulhouse Sud-Alsace, Mulhouse, France (Khaldoun Kuteifan, Valentin Pointurier, Louise-Marie Jandeaux, Joy Mootien); APHP - Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart, France (Charles Damoisel, Benjamin Sztrymf); APHP - Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Matthieu Schmidt, Alain Combes, Juliette Chommeloux, Charles Edouard Luyt); Hôpital Intercommunal de Créteil, Créteil, France (Frédérique Schortgen, Leon Rusel, Camille Jung); Hospices Civils de Lyon - Hôpital Neurologique, Lyon, France (Florent Gobert); APHP - Hôpital Necker, Paris, France (Damien Vimpere, Lionel Lamhaut); Centre Hospitalier Public du Cotentin - Hôpital Pasteur, Cherbourg-en-cotentin, France (Bertrand Sauneuf, Liliane Charrrier, Julien Calus, Isabelle Desmeules); CHU Rennes - Hôpital du Pontchaillou, Rennes, France (Benoît Painvin, Jean-Marc Tadie); CHU Strasbourg - Hôpital Hautepierre, Strasbourg, France (Vincent Castelain, Baptiste Michard, Jean-Etienne Herbrecht, Mathieu Baldacini); APHP - Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Nicolas Weiss, Sophie Demeret, Clémence Marois, Benjamin Rohaut); Centre Hospitalier Territorial Gaston-Bourret, Nouméa, France (Pierre-Henri Moury, Anne-Charlotte Savida, Emmanuel Couadau, Mathieu Série); Centre Hospitalier Compiègne-Noyon, Compiègne, France (Nica Alexandru); Groupe Hospitalier Saint-Joseph, Paris, France (Cédric Bruel, Candice Fontaine, Sonia Garrigou, Juliette Courtiade Mahler); Centre hospitalier mémorial de Saint-Lô, Saint-Lô, France (Maxime Leclerc, Michel Ramakers); Grand Hôpital de l'Est Francilien, Jossigny, France (Pierre Garçon, Nicole Massou, Ly Van Vong, Juliane Sen); Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France (Nolwenn Lucas, Franck Chemouni, Annabelle Stoclin); Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal Robert Ballanger, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France (Alexandre Avenel, Henri Faure, Angélie Gentilhomme, Sylvie Ricome); Hospices Civiles de Lyon - Hôpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France (Paul Abraham, Céline Monard, Julien Textoris, Thomas Rimmele); Centre Hospitalier d'Avignon, Avignon, France (Florent Montini); Groupe Hospitalier Diaconesses - Croix Saint Simon, Paris, France (Gabriel Lejour, Thierry Lazard, Isabelle Etienney, Younes Kerroumi); CHU Clermont-Ferrand - Hôpital Gabriel Montpied, Clermont Ferrand, France (Claire Dupuis, Marine Bereiziat, Elisabeth Coupez, François Thouy); Hôpital d'Instruction des Armées Percy, Clamart, France (Clément Hoffmann, Nicolas Donat, Anne Chrisment, Rose-Marie Blot); CHU Nancy - Hôpital Brabois, Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France (Antoine Kimmoun, Audrey Jacquot, Matthieu Mattei, Bruno Levy); Centre Hospitalier de Vichy, Vichy, France (Ramin Ravan, Loïc Dopeux, Jean-Mathias Liteaudon, Delphine Roux); Hopital Pierre Bérégovoy, Nevers, France (Brice Rey, Radu Anghel, Deborah Schenesse, Vincent Gevrey); Centre Hospitalier de Tarbes, Tarbes, France (Jermy Castanera, Philippe Petua, Benjamin Madeux); Hôpitaux Civils de Colmar - Hôpital Louis pasteur, Colmar, France (Otto Hartman); CHU Charleroi - Hôpital Marie Curie, Bruxelles, Belgique (Michael Piagnerelli, Anne Joosten, Cinderella Noel, Patrick Biston); Centre hospitalier de Verdun Saint Mihiel, Saint Mihiel, France (Thibaut Noel); CH Eure-Seine - Hôpital d'Evreux-Vernon, Evreux, France (Gurvan LE Bouar, Messabi Boukhanza, Elsa Demarest, Marie-France Bajolet); Hôpital René Dubos, Pontoise, France (Nathanaël Charrier, Audrey Quenet, Cécile Zylberfajn, Nicolas Dufour); APHP - Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris, France (Buno Mégarbane, Sébastian Voicu, Nicolas Deye, Isabelle Malissin); Centre Hospitalier de Saint-Brieuc, Saint-Brieuc, France (François Legay, Matthieu Debarre, Nicolas Barbarot, Pierre Fillatre); Polyclinique Bordeaux Nord Aquitaine, Bordeaux, France (Bertrand Delord, Thomas Laterrade, Tahar Saghi, Wilfried Pujol); HIA Sainte Anne, Toulon, France (Pierre Julien Cungi, Pierre Esnault, Mickael Cardinale); Grand Hôpital de l'Est Francilien, Meaux, France (Vivien Hong Tuan Ha, Grégory Fleury, Marie-Ange Brou, Daniel Zafimahazo); HIA Robert Picqué, Villenave d'Ornon, France (David Tran-Van, Patrick Avargues, Lisa Carenco); Centre Hospitalier Fontainebleau, Fontainebleau, France (Nicolas Robin, Alexandre Ouali, Lucie Houdou); Hôpital Universitaire de Genève, Genève, Suisse (Christophe Le Terrier, Noémie Suh, Steve Primmaz, Jérome Pugin); APHP - Hôpital Beaujon, Clichy, France (Emmanuel Weiss, Tobias Gauss, Jean-Denis Moyer, Catherine Paugam Burtz); Groupe Hospitalier Bretage Sud, Lorient, France (Béatrice La Combe, Rolland Smonig, Jade Violleau, Pauline Cailliez); Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal Toulon, La Seyne sur Mer, France (Jonathan Chelly), Centre Hospitalier de Dieppe, Dieppe, France (Antoine Marchalot, Cécile Saladin, Christelle Bigot); CHU de Martinique, Fort-de-France, France (Pierre-Marie Fayolle, Jules Fatséas, Amr Ibrahim, Dabor Resiere); Hôpital Fondation Adolphe de Rothchild, Paris, France (Rabih Hage, Clémentine Cholet, Marie Cantier, Pierre Trouiler); APHP - Bichat Claude Bernard, Paris, France (Philippe Montravers, Brice Lortat-Jacob, Sebastien Tanaka, Alexy Tran Dinh); APHP - Hôpital Universitaire Paris Sud, Bicêtre, France (Jacques Duranteau, Anatole Harrois, Guillaume Dubreuil, Marie Werner); APHP - Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France (Anne Godier, Sophie Hamada, Diane Zlotnik, Hélène Nougue); APHP, GHU Henri Mondor, Créteil, France (Armand Mekontso-Dessap, Guillaume Carteaux, Keyvan Razazi, Nicolas De Prost); APHP - Hôpitaux Universitaires Henri Mondor, Créteil, France (Nicolas Mongardon, Meriam Lamraoui, Claire Alessandri, Quentin de Roux); APHP - Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris, France (Charles de Roquetaillade, Benjamin G. Chousterman, Alexandre Mebazaa, Etienne Gayat); APHP - Hôpital Saint-Antoine, Paris, France (Marc Garnier, Emmanuel Pardo, LeaSatre-Buisson, Christophe Gutton); APHP Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France (Elise Yvin, Clémence Marcault, Elie Azoulay, Michael Darmon), APHP - Hôpital Saint-Antoine, Paris, France (Hafid Ait Oufella, Geoffroy Hariri, Tomas Urbina, Sandie Mazerand); APHP - Hôpital Raymond Pointcarré, Garches, France (Nicholas Heming, Francesca Santi, Pierre Moine, Djillali Annane); APHP - Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Adrien Bouglé, Edris Omar, Aymeric Lancelot, Emmanuelle Begot); Centre Hospitalier Victor Dupouy, Argenteuil, France (Gaétan Plantefeve, Damien Contou, Hervé Mentec, Olivier Pajot); CHU Toulouse - Hôpital Rangueil, Toulouse, France (Stanislas Faguer, Olivier Cointault, Laurence Lavayssiere, Marie-Béatrice Nogier); Centre Hospitalier de Poissy, Poissy, France (Matthieu Jamme, Claire Pichereau, Jan Hayon, Hervé Outin); APHP - Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France (François Dépret, Maxime Coutrot, Maité Chaussard, Lucie Guillemet); Clinique du MontLégia, CHC Groupe-Santé, Liège, Belgique (Pierre Goffin, Romain Thouny, Julien Guntz, Laurent Jadot); CHU Saint-Denis, La Réunion, France (Romain Persichini), Centre Hospitalier de Tourcoing, Tourcoing, France (Vanessa Jean-Michel, Hugues Georges, Thomas Caulier); Centre Hospitalier Henri Mondor d'Aurillac, Aurillac, France (Gaël Pradel, Marie-Hélène Hausermann, Thi My Hue Nguyen-Valat, Michel Boudinaud); Centre Hospitalier Saint Joseph Saint Luc, Lyon, France (Emmanuel Vivier, SylvèneRosseli, Gaël Bourdin, Christian Pommier); Centre Hospitalier de Polynésie Française, Polynésie, France (Marc Vinclair, Simon Poignant, Sandrine Mons); Ramsay Générale de Santé, Hôpital Privé Jacques Cartier, Massy, France (Wulfran Bougouin); Centre Hospitalier Alpes Léman, Contamine sur Arve, France (Franklin Bruna, Quentin Maestraggi, Christian Roth); Hospices Civils de Lyon - Hôpital de la Croix Rousse, Lyon, France (Laurent Bitker, François Dhelft, Justine Bonnet-Chateau, Mathilde Filippelli); Centre Cardiologique du Nord, Saint-Denis, France (Tristan Morichau-Beauchant, Stéphane Thierry, Charlotte Le Roy, Mélanie Saint Jouan); GHU - Hôpital Saint-Anne, Paris, France (Bruno Goncalves, Aurélien Mazeraud, Matthieu Daniel, Tarek Sharshar); CHR Metz - Hôpital Mercy, Metz, France (Cyril Cadoz, RostaneGaci, Sébastien Gette, Guillaune Louis); APHP - Hôpital Paul Brousse, Villejuif, France (Sophe-Caroline Sacleux, Marie-Amélie Ordan); CHRU Nancy - Hôpital Central, Nancy, France (Aurélie Cravoisy, Marie Conrad, Guilhem Courte, Sébastien Gibot); Centre Hospitalier d’Ajaccio, Ajaccio, France (Younès Benzidi, Claudia Casella, Laurent Serpin, Jean-Lou Setti); Centre Hospitalier de Bourges, Bourges, France (Marie-Catherine Besse, Anna Bourreau); Centre hospitalier de la Côte Basque, Bayonne, France (Jérôme Pillot, Caroline Rivera, Camille Vinclair, Marie-Aline Robaux); Hospices Civils de Lyon - Hôpital de la Croix Rousse, Lyon, France (Chloé Achino, Marie-Charlotte Delignette, Tessa Mazard, Frédéric Aubrun); CH Saint-Malo, Saint-Malo, France (Bruno Bouchet, Aurélien Frérou, Laura Muller, Charlotte Quentin); Centre Hospitalier de Mulhouse, Mulhouse, France (Samuel Degoul); Centre Hospitalier de Briançon, Briançon, France (Xavier Stihle, Claude Sumian, Nicoletta Bergero, Bernard Lanaspre); CHU Nice, Hôpital Pasteur 2, Nice, France (Hervé Quintard, Eve Marie Maiziere); Centre Hospitalier des Pays de Morlaix, Morlaix, France (Pierre-Yves Egreteau, Guillaume Leloup, Florin Berteau, Marjolaine Cottrel); Centre Hospitalier Valence, Valence, France (Marie Bouteloup, Matthieu Jeannot, Quentin Blanc, Julien Saison); Centre Hospitalier Niort, Niort, France (Isabelle Geneau, Romaric Grenot, Abdel Ouchike, Pascal Hazera); APHP - Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Anne-Lyse Masse, Suela Demiri, Corinne Vezinet, Elodie Baron, Deborah Benchetrit, Antoine Monsel); Clinique du Val d'Or, Saint Cloud, France (Grégoire Trebbia, Emmanuelle Schaack, Raphaël Lepecq, Mathieu Bobet); Centre Hospitalier de Béthune, Béthune, France (Christophe Vinsonneau, Thibault Dekeyser, Quentin Delforge, Imen Rahmani); Groupe Hospitalier Intercommunal de la Haute-Saône, Vesoul, France (Bérengère Vivet, Jonathan Paillot, Lucie Hierle, Claire Chaignat, Sarah Valette); Clinique Saint-Martin, Caen, France (Benoït Her, Jennifier Brunet); Ramsay Générale de Santé, Clinique Convert, Bourg en Bresse, France (Mathieu Page, Fabienne Boiste, Anthony Collin); Hôpital Victor Jousselin, Dreux, France (Florent Bavozet, Aude Garin, Mohamed Dlala, Kais Mhamdi); Centre Hospitalier de Troye, Troye, France (Bassem Beilouny, Alexandra Lavalard, Severine Perez); CHU de ROUEN-Hôpital Charles Nicolle, Rouen, France (Benoit Veber, Pierre-Gildas Guitard, Philippe Gouin, Anna Lamacz); Centre Hospitalier Agen-Nérac, Agen, France (Fabienne Plouvier, Bertrand P Delaborde, Aïssa Kherchache, Amina Chaalal); APHP - Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes, France (Jean-Damien Ricard, Marc Amouretti, Santiago Freita-Ramos, Damien Roux); APHP - Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Jean-Michel Constantin, Mona Assefi, Marine Lecore, Agathe Selves); Institut Mutualiste Montsouris, Paris, France (Florian Prevost, Christian Lamer, Ruiying Shi, Lyes Knani); CHU Besançon – Hôpital Jean Minjoz, Besançon, France (Sébastien Pili Floury, Lucie Vettoretti); APHP - Hôpital Universitaire Robert-Debré, Paris, France (Michael Levy, Lucile Marsac, Stéphane Dauger, Sophie Guilmin-Crépon); CHU Besançon – Hôpital Jean Minjoz, Besançon, France (Hadrien Winiszewski, Gael Piton, Thibaud Soumagne, Gilles Capellier); Médipôle Lyon-Villeurbanne, Vileurbanne, France (Jean-Baptiste Putegnat, Frédérique Bayle, Maya Perrou, Ghyslaine Thao); APHP - Ambroise Paré, Boulogne-Billancourt, France (Guillaume Géri, Cyril Charron, Xavier Repessé, Antoine Vieillard-Baron); CHU Amiens Picardie, Amiens, France (Mathieu Guilbart, Pierre-Alexandre Roger, Sébastien Hinard, Pierre-Yves Macq); Hôpital Nord-Ouest, Villefranche-sur-Saône, France (Kevin Chaulier, Sylvie Goutte); CH de Châlons en Champagne, Châlons en Champagne, France (Patrick Chillet, Anaïs Pitta, Barbara Darjent, Amandine Bruneau); CHU Angers, Angers, France (Sigismond Lasocki, Maxime Leger, Soizic Gergaud, Pierre Lemarie); CHU Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France (Nicolas Terzi, Carole Schwebel, Anaïs Dartevel, Louis-Marie Galerneau); APHP - Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France (Jean-Luc Diehl, Caroline Hauw-Berlemont, Nicolas Péron, Emmanuel Guérot); Hôpital Privé d'Antony, Antony, France (Abolfazl Mohebbi Amoli, Michel Benhamou, Jean-Pierre Deyme, Olivier Andremont); Institut Arnault Tzanck, Saint Laurent du Var, France (Diane Lena, Julien Cady, Arnaud Causeret, Arnaud De La Chapelle); Centre Hospitalier d’ Angoulême, Angoulême, France (Christophe Cracco, Stéphane Rouleau, David Schnell); Centre Hospitalier de Cahors, Cahors, France (Camille Foucault); Centre hospitalier de Carcassonne, Carcassonne, France (Cécile Lory); CHU Nice – Hôpital L’Archet 2, Nice, France (Thibault Chapelle, Vincent Bruckert, Julie Garcia, Abdlazize Sahraoui); Hôpital Privé du Vert Galant, Tremblay-en-France, France (Nathalie Abbosh, Caroline Bornstain, Pierre Pernet); Centre Hospitalier de Rambouillet, Rambouillet, France (Florent Poirson, Ahmed Pasem, Philippe Karoubi); Hopitaux du Léman, Thonon les Bains, France (Virginie Poupinel, Caroline Gauthier, François Bouniol, Philippe Feuchere); Centre Hospitalier Victor Jousselin, Dreux, France (Florent Bavozet, Anne Heron); Hôpital Sainte Camille, Brie sur Marne, France (Serge Carreira, Malo Emery, Anne Sophie Le Floch, Luana Giovannangeli); Hôpital d’instruction des armées Clermont-Tonnerre, Brest, France (Nicolas Herzog, Christophe Giacardi, Thibaut Baudic, Chloé Thill); APHP - Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France (Said Lebbah, Jessica Palmyre, Florence Tubach, David Hajage); APHP - Hôpital Avicenne, Bobigny, France (Nicolas Bonnet, Nathan Ebstein, Stéphane Gaudry, Yves Cohen); Groupement Hospitalier la Rochelle Ré Amis, La Rochelle, France (Julie Noublanche, Olivier Lesieur); Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal de Mont de Marsan et du Pays des Sources, Mont de Marsan, France (Arnaud Sément, Isabel Roca-Cerezo, Michel Pascal, Nesrine Sma); Centre Hospitalier Départemental de Vendée, La-Roche-Sur-Yon, France (Gwenhaël Colin, Jean-Claude Lacherade, Gauthier Bionz, Natacha Maquigneau); Pôle Anesthésie-Réanimation, CHU Grenoble (Pierre Bouzat, Michel Durand, Marie-Christine Hérault, Jean-Francois Payen).

Footnotes

A complete list of the COVID-ICU Investigators may be found before the beginning of the References.

Supported by the Foundation APHP (Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris) and its donators through the program “Alliance Tous Unis Contre le Virus”, the Direction de la Recherche Clinique et du Développement, and the French Ministry of Health and the foundation of the University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. This research was funded in whole or in part by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, MR/T032448/1. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. C.L. is supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (Skills Development Fellowship MR/T032448/1). R.H.K. is funded by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/S017968/1). C.M. and A. Belot are funded by a Cancer Research United Kingdom program grant (C7923/A29018).

Data sharing: Individual patient data reported in this article will be shared after de-identification (text, tables, figures, and appendices), beginning 6 months, and ending 2 years after article publication, to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal and after approval of the COVID-ICU internal scientific committee. Proposals should be addressed to matthieu.schmidt@aphp.fr. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Author Contributions: A.C., C.G., G.L., A.M., A.P., S.N., A.M.-D., N.M., J.P.M., J.-D.R., A. Belot, G.T., L.K., C.L.T., J.C.R., B.M., and M.S. were involved in data generation. M.S., D.H., R.H.K., A. Buerton, C.M., C.L., and A.C. developed the protocol and the statistical analysis plan. D.H. performed the statistical analysis of the data. M.S., D.H., and A.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript. D.H. and M.S. take responsibility for the integrity of the work, from inception to published article.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2495OC on May 9, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

for the COVID-ICU Investigators:

Alain Mercat, Pierre Asfar, François Beloncle, Julien Demiselle, Tài Pham, Arthur Pavot, Xavier Monnet, Christian Richard, Alexandre Demoule, Martin Dres, Julien Mayaux, Alexandra Beurton, Cédric Daubin, Richard Descamps, Aurélie Joret, Damien Du Cheyron, Frédéric Pene, Jean-Daniel Chiche, Mathieu Jozwiak, Paul Jaubert, Guillaume Voiriot, Muriel Fartoukh, Marion Teulier, Clarisse Blayau, Erwen L'Her, Cécile Aubron, Laetitia Bodenes, Nicolas Ferriere, Johann Auchabie, Anthony Le Meur, Sylvain Pignal, Thierry Mazzoni, Jean-Pierre Quenot, Pascal Andreu, Jean-Baptiste Roudau, Marie Labruyère, Saad Nseir, Sébastien Preau, Julien Poissy, Daniel Mathieu, Sarah Benhamida, Rémi Paulet, Nicolas Roucaud, Martial Thyrault, Florence Daviet, Sami Hraiech, Gabriel Parzy, Aude Sylvestre, Sébastien Jochmans, Anne-Laure Bouilland, Mehran Monchi, Marc Danguy des Déserts, Quentin Mathais, Gwendoline Rager, Pierre Pasquier, Jean Reignier, Amélie Seguin, Charlotte Garret, Emmanuel Canet, Jean Dellamonica, Clément Saccheri, Romain Lombardi, Yanis Kouchit, Sophie Jacquier, Armelle Mathonnet, Mai-Ahn Nay, Isabelle Runge, Frédéric Martino, Laure Flurin, Amélie Rolle, Michel Carles, Rémi Coudroy, Arnaud W. Thille, Jean-Pierre Frat, Maeva Rodriguez, Pascal Beuret, Audrey Tientcheu, Arthur Vincent, Florian Michelin, Fabienne Tamion, Dorothée Carpentier, Déborah Boyer, Gaetan Beduneau, Valérie Gissot, Stéphan Ehrmann, Charlotte Salmon Gandonniere, Djlali Elaroussi, Agathe Delbove, Yannick Fedun, Julien Huntzinger, Eddy Lebas, Grâce Kisoka, Céline Grégoire, Stella Marchetta, Bernard Lambermont, Laurent Argaud, Thomas Baudry, Pierre-Jean Bertrand, Auguste Dargent, Christophe Guitton, Nicolas Chudeau, Mickaël Landais, Cédric Darreau, Alexis Ferre, Antoine Gros, Guillaume Lacave, Fabrice Bruneel, Mathilde Neuville, Jérôme Devaquet, Guillaume Tachon, Richard Gallot, Riad Chelha, Arnaud Galbois, Anne Jallot, Ludivine Chalumeau Lemoine, Khaldoun Kuteifan, Valentin Pointurier, Louise-Marie Jandeaux, Joy Mootien, Charles Damoisel, Benjamin Sztrymf, Matthieu Schmidt, Alain Combes, Juliette Chommeloux, Charles Edouard Luyt, Frédérique Schortgen, Leon Rusel, Camille Jung, Florent Gobert, Damien Vimpere, Lionel Lamhaut, Bertrand Sauneuf, Liliane Charrrier, Julien Calus, Isabelle Desmeules, Benoît Painvin, Jean-Marc Tadie, Vincent Castelain, Baptiste Michard, Jean-Etienne Herbrecht, Mathieu Baldacini, Nicolas Weiss, Sophie Demeret, Clémence Marois, Benjamin Rohaut, Pierre-Henri Moury, Anne-Charlotte Savida, Emmanuel Couadau, Mathieu Série, Nica Alexandru, Cédric Bruel, Candice Fontaine, Sonia Garrigou, Juliette Courtiade Mahler, Maxime Leclerc, Michel Ramakers, Pierre Garçon, Nicole Massou, Ly Van Vong, Juliane Sen, Nolwenn Lucas, Franck Chemouni, Annabelle Stoclin, Alexandre Avenel, Henri Faure, Angélie Gentilhomme, Sylvie Ricome, Paul Abraham, Céline Monard, Julien Textoris, Thomas Rimmele, Florent Montini, Gabriel Lejour, Thierry Lazard, Isabelle Etienney, Younes Kerroumi, Claire Dupuis, Marine Bereiziat, Elisabeth Coupez, François Thouy, Clément Hoffmann, Nicolas Donat, Anne Chrisment, Rose-Marie Blot, Antoine Kimmoun, Audrey Jacquot, Matthieu Mattei, Bruno Levy, Ramin Ravan, Loïc Dopeux, Jean-Mathias Liteaudon, Delphine Roux, Brice Rey, Radu Anghel, Deborah Schenesse, Vincent Gevrey, Jermy Castanera, Philippe Petua, Benjamin Madeux, Otto Hartman, Michael Piagnerelli, Anne Joosten, Cinderella Noel, Patrick Biston, Thibaut Noel, Gurvan LE Bouar, Messabi Boukhanza, Elsa Demarest, Marie-France Bajolet, Nathanaël Charrier, Audrey Quenet, Cécile Zylberfajn, Nicolas Dufour, Buno Mégarbane, Sébastian Voicu, Nicolas Deye, Isabelle Malissin, François Legay, Matthieu Debarre, Nicolas Barbarot, Pierre Fillatre, Bertrand Delord, Thomas Laterrade, Tahar Saghi, Wilfried Pujol, Pierre Julien Cungi, Pierre Esnault, Mickael Cardinale, Vivien Hong Tuan Ha, Grégory Fleury, Marie-Ange Brou, Daniel Zafimahazo, David Tran-Van, Patrick Avargues, Lisa Carenco, Nicolas Robin, Alexandre Ouali, Lucie Houdou, Christophe Le Terrier, Noémie Suh, Steve Primmaz, Jérome Pugin, Emmanuel Weiss, Tobias Gauss, Jean-Denis Moyer, Catherine Paugam Burtz, Béatrice La Combe, Rolland Smonig, Jade Violleau, Pauline Cailliez, Jonathan Chelly, Antoine Marchalot, Cécile Saladin, Christelle Bigot, Pierre-Marie Fayolle, Jules Fatséas, Amr Ibrahim, Dabor Resiere, Rabih Hage, Clémentine Cholet, Marie Cantier, Pierre Trouiler, Philippe Montravers, Brice Lortat-Jacob, Sebastien Tanaka, Alexy Tran Dinh, Jacques Duranteau, Anatole Harrois, Guillaume Dubreuil, Marie Werner, Anne Godier, Sophie Hamada, Diane Zlotnik, Hélène Nougue, Armand Mekontso-Dessap, Guillaume Carteaux, Keyvan Razazi, Nicolas De Prost, Nicolas Mongardon, Meriam Lamraoui, Claire Alessandri, Quentin de Roux, Charles de Roquetaillade, Benjamin G. Chousterman, Alexandre Mebazaa, Etienne Gayat, Marc Garnier, Emmanuel Pardo, Lea Satre-Buisson, Christophe Gutton, Elise Yvin, Clémence Marcault, Elie Azoulay, Michael Darmon, Hafid Ait Oufella, Geoffroy Hariri, Tomas Urbina, Sandie Mazerand, Nicholas Heming, Francesca Santi, Pierre Moine, Djillali Annane, Adrien Bouglé, Edris Omar, Aymeric Lancelot, Emmanuelle Begot, Gaétan Plantefeve, Damien Contou, Hervé Mentec, Olivier Pajot, Stanislas Faguer, Olivier Cointault, Laurence Lavayssiere, Marie-Béatrice Nogier, Matthieu Jamme, Claire Pichereau, Jan Hayon, Hervé Outin, François Dépret, Maxime Coutrot, Maité Chaussard, Lucie Guillemet, Pierre Goffin, Romain Thouny, Julien Guntz, Laurent Jadot, Romain Persichini, Vanessa Jean-Michel, Hugues Georges, Thomas Caulier, Gaël Pradel, Marie-Hélène Hausermann, Thi My Hue Nguyen-Valat, Michel Boudinaud, Emmanuel Vivier, Sylvène Rosseli, Gaël Bourdin, Christian Pommier, Marc Vinclair, Simon Poignant, Sandrine Mons, Wulfran Bougouin, Franklin Bruna, Quentin Maestraggi, Christian Roth, Laurent Bitker, François Dhelft, Justine Bonnet-Chateau, Mathilde Filippelli, Tristan Morichau-Beauchant, Stéphane Thierry, Charlotte Le Roy, Mélanie Saint Jouan, Bruno Goncalves, Aurélien Mazeraud, Matthieu Daniel, Tarek Sharshar, Cyril Cadoz, Rostane Gaci, Sébastien Gette, Guillaune Louis, Sophe-Caroline Sacleux, Marie-Amélie Ordan, Aurélie Cravoisy, Marie Conrad, Guilhem Courte, Sébastien Gibot, Younès Benzidi, Claudia Casella, Laurent Serpin, Jean-Lou Setti, Marie-Catherine Besse, Anna Bourreau, Jérôme Pillot, Caroline Rivera, Camille Vinclair, Marie-Aline Robaux, Chloé Achino, Marie-Charlotte Delignette, Tessa Mazard, Frédéric Aubrun, Bruno Bouchet, Aurélien Frérou, Laura Muller, Charlotte Quentin, Samuel Degoul, Xavier Stihle, Claude Sumian, Nicoletta Bergero, Bernard Lanaspre, Hervé Quintard, Eve Marie Maiziere, Pierre-Yves Egreteau, Guillaume Leloup, Florin Berteau, Marjolaine Cottrel, Marie Bouteloup, Matthieu Jeannot, Quentin Blanc, Julien Saison, Isabelle Geneau, Romaric Grenot, Abdel Ouchike, Pascal Hazera, Anne-Lyse Masse, Suela Demiri, Corinne Vezinet, Elodie Baron, Deborah Benchetrit, Antoine Monsel, Grégoire Trebbia, Emmanuelle Schaack, Raphaël Lepecq, Mathieu Bobet, Christophe Vinsonneau, Thibault Dekeyser, Quentin Delforge, Imen Rahmani, Bérengère Vivet, Jonathan Paillot, Lucie Hierle, Claire Chaignat, Sarah Valette, Benoït Her, Jennifier Brunet, Mathieu Page, Fabienne Boiste, Anthony Collin, Florent Bavozet, Aude Garin, Mohamed Dlala, Kais Mhamdi, Bassem Beilouny, Alexandra Lavalard, Severine Perez, Benoit Veber, Pierre-Gildas Guitard, Philippe Gouin, Anna Lamacz, Fabienne Plouvier, Bertrand P Delaborde, Aïssa Kherchache, Amina Chaalal, Jean-Damien Ricard, Marc Amouretti, Santiago Freita-Ramos, Damien Roux, Jean-Michel Constantin, Mona Assefi, Marine Lecore, Agathe Selves, Florian Prevost, Christian Lamer, Ruiying Shi, Lyes Knani, Sébastien Pili Floury, Lucie Vettoretti, Michael Levy, Lucile Marsac, Stéphane Dauger, Sophie Guilmin-Crépon, Hadrien Winiszewski, Gael Piton, Thibaud Soumagne, Gilles Capellier, Jean-Baptiste Putegnat, Frédérique Bayle, Maya Perrou, Ghyslaine Thao, Guillaume Géri, Cyril Charron, Xavier Repessé, Antoine Vieillard-Baron, Mathieu Guilbart, Pierre-Alexandre Roger, Sébastien Hinard, Pierre-Yves Macq, Kevin Chaulier, Sylvie Goutte, Patrick Chillet, Anaïs Pitta, Barbara Darjent, Amandine Bruneau, Sigismond Lasocki, Maxime Leger, Soizic Gergaud, Pierre Lemarie, Nicolas Terzi, Carole Schwebel, Anaïs Dartevel, Louis-Marie Galerneau, Jean-Luc Diehl, Caroline Hauw-Berlemont, Nicolas Péron, Emmanuel Guérot, Abolfazl Mohebbi Amoli, Michel Benhamou, Jean-Pierre Deyme, Olivier Andremont, Diane Lena, Julien Cady, Arnaud Causeret, Arnaud De La Chapelle, Christophe Cracco, Stéphane Rouleau, David Schnell, Camille Foucault, Cécile Lory, Thibault Chapelle, Vincent Bruckert, Julie Garcia, Abdlazize Sahraoui, Nathalie Abbosh, Caroline Bornstain, Pierre Pernet, Florent Poirson, Ahmed Pasem, Philippe Karoubi, Virginie Poupinel, Caroline Gauthier, François Bouniol, Philippe Feuchere, Florent Bavozet, Anne Heron, Serge Carreira, Malo Emery, Anne Sophie Le Floch, Luana Giovannangeli, Nicolas Herzog, Christophe Giacardi, Thibaut Baudic, Chloé Thill, Said Lebbah, Jessica Palmyre, Florence Tubach, David Hajage, Nicolas Bonnet, Nathan Ebstein, Stéphane Gaudry, Yves Cohen, Julie Noublanche, Olivier Lesieur, Arnaud Sément, Isabel Roca-Cerezo, Michel Pascal, Nesrine Sma, Gwenhaël Colin, Jean-Claude Lacherade, Gauthier Bionz, Natacha Maquigneau, Pierre Bouzat, Michel Durand, Marie-Christine Hérault, and Jean-Francois Payen

References

- 1. Badulak J, Antonini MV, Stead CM, Shekerdemian L, Raman L, Paden ML, et al. ELSO COVID-19 Working Group Members Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for COVID-19: updated 2021 guidelines from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ASAIO J . 2021;67:485–495. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, Iwashyna TJ, Slutsky AS, Fan E, et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet . 2020;396:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt M, Hajage D, Lebreton G, Monsel A, Voiriot G, Levy D, et al. Groupe de Recherche Clinique en REanimation et Soins intensifs du Patient en Insuffisance Respiratoire aiguE (GRC-RESPIRE) Sorbonne Université Paris-Sorbonne ECMO-COVID investigators. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med . 2020;8:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30328-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lebreton G, Schmidt M, Ponnaiah M, Folliguet T, Para M, Guihaire J, et al. Paris ECMO-COVID-19 Investigators Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation network organisation and clinical outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greater Paris, France: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med . 2021;9:851–862. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00096-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoué S, Guervilly C, et al. EOLIA Trial Group, REVA, and ECMONet Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med . 2018;378:1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmidt M, Pham T, Arcadipane A, Agerstrand C, Ohshimo S, Pellegrino V, et al. Mechanical ventilation management during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. An international multicenter prospective cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;200:1002–1012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1094OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany MM, et al. CESAR trial collaboration Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goligher EC, Tomlinson G, Hajage D, Wijeysundera DN, Fan E, Jüni P, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and posterior probability of mortality benefit in a post hoc Bayesian analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:2251–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combes A, Peek GJ, Hajage D, Hardy P, Abrams D, Schmidt M, et al. ECMO for severe ARDS: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2048–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaefi S, Brenner SK, Gupta S, O’Gara BP, Krajewski ML, Charytan DM, et al. STOP-COVID Investigators Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with severe respiratory failure from COVID-19. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:208–221. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06331-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. COVID-ICU Group on behalf of the REVA Network and the COVID-ICU Investigators. Clinical characteristics and day-90 outcomes of 4244 critically ill adults with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:60–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol . 2016;183:758–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. García-Albéniz X, Hsu J, Hernán MA. The value of explicitly emulating a target trial when using real world evidence: an application to colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Epidemiol . 2017;32:495–500. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0287-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barbaro RP, Odetola FO, Kidwell KM, Paden ML, Bartlett RH, Davis MM, et al. Association of hospital-level volume of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and mortality. Analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2015;191:894–901. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1634OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hernán MA, Robins JM. Estimating causal effects from epidemiological data. J Epidemiol Community Health . 2006;60:578–586. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hernán MA. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology . 2010;21:13–15. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gran JM, Røysland K, Wolbers M, Didelez V, Sterne JAC, Ledergerber B, et al. A sequential Cox approach for estimating the causal effect of treatment in the presence of time-dependent confounding applied to data from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Stat Med . 2010;29:2757–2768. doi: 10.1002/sim.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, Albano G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, et al. COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med . 2020;180:1345–1355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Rozé H, Repesse X, Lebreton G, Luyt CE, et al. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med . 2013;39:1704–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3037-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, Hodgson C, Aubron C, Rycus PT, et al. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival prediction (RESP) score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2014;189:1374–1382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-2023OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]