Abstract

This cohort study examines the association between approval characteristics, clinical benefit, and prices of cancer drugs recommended for reimbursement by the Canadian Agency for Drug and Technology in Health.

Introduction

Cancer drug prices have increased exponentially in the past decade and several studies have demonstrated an increasing disconnect between clinical benefit and prices for cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency.1,2 This disconnect seemed to exist even in the setting of central price negotiations in Italy.3 However, to our knowledge this has not been studied for Canada. This study examined the association between approval characteristics, clinical benefit, and prices for cancer drugs recommended for reimbursement in Canada by the Canadian Agency for Drug and Technology in Health (CADTH).

Methods

CADTH provides funding recommendations to Canadian provinces and territories (except Quebec). We conducted a retrospective cohort study of anticancer drugs for treatment of solid tumors in adult patients that received positive reimbursement recommendations from inception in 2011 to 2020. Supportive care medicines, hematologic neoplasms, pediatric indications, and biosimilars were excluded, which allowed for a homogenous cohort to evaluate clinical benefit using the ESMO-MCBS (European Society for Medical Oncology-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale).4 In this scale, a score of 4 or 5 in the metastatic setting or A or B in adjuvant settings were considered substantial clinical benefit. We extracted supporting trials characteristics and monthly drug prices from CADTH reports.5

This study examined publicly available data and did not require institutional ethics approval as per the research ethics policy and procedures at the London School of Economics and Political Science. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

While prices do not reflect confidential discounts, estimates are based on data submitted by the manufacturer and reanalyzed by CADTH. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were used to determine the association between approval characteristics and prices. Linear regression was used to examine the association between percentage improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) with monthly prices using R Statistical Software version 3.5.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing). P < .05 in 2-sided tests was considered statistically significant. All prices are reported in US dollars.

Results

Between 2011 and 2020, there were 78 positive reimbursement recommendations for solid tumors. Of these, 30 (38%) were for novel drugs, 41 (53%) for new indications of existing drugs, and 7 (9%) were resubmissions that received previous negative decisions. All submissions had evidence from a phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trial.

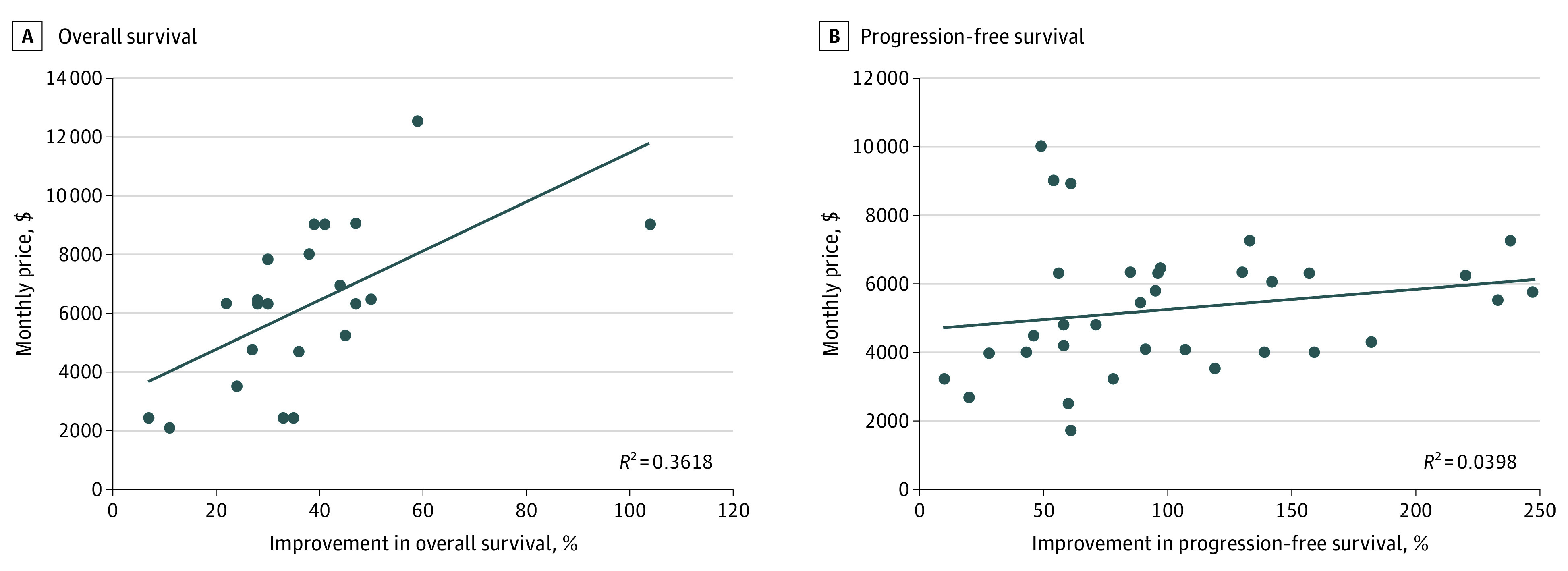

Drugs that offered substantial clinical benefit were associated with a higher median monthly price ($6207; range, $1723-$34 305) compared with low benefit ($4437; range, $782-$11 733) per ESMO-MCBS (P < .001) (Table). Immune checkpoint inhibitors were priced highest ($8533; range, $5668-$34 305). There was a significant difference between the median monthly treatment costs of drugs that received recommendations for melanoma compared with other tumor types (eg, monthly price: melanoma, $8342; range, $782-$34 305 vs gastrointestinal, $4293; range, $2105-$17 500; P < .001). Conditional recommendations were associated with higher median monthly prices compared with regular recommendations ($6184; range, $1723-$34 305 vs $3289; range, $782-$7298; P < .001). No other significant associations were found. We found a weak correlation between monthly treatment costs and percentage improvements in median PFS (R2 = 0.040) and OS (R2 = 0.361) (Figure).

Table. Prices and Characteristics of Cancer Medicines Recommended for Funding in Canada Between 2011 to 2020.

| Characteristic | Monthly price, median (range), US$a | P valueb |

|---|---|---|

| Drug | ||

| Total submissions | 6025 (782-26 388) | NA |

| Type of submission | ||

| New drug | 6148 (1723-32 480) | .96 |

| New indication | 5936 (782-34 305) | |

| Resubmission | 5683 (3188-9445) | |

| Type of recommendation | ||

| Conditional | 6184 (1723-34 305) | <.001 |

| Regular | 3289 (782-7298) | |

| Drug type | ||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor | 8533 (5668-34 305) | <.001 |

| Monoclonal antibody | 6324 (3231-13 031) | |

| Small molecule inhibitor | 5481 (1723-17 992) | |

| Hormonal therapy | 2390 (2441-3497) | |

| Cytotoxic therapy | 4526 (3515-6820) | |

| Other | 3921 (782-17 500) | |

| Trial | ||

| Tumor type | ||

| Genitourinary | 3289 (2441-16 302) | <.001 |

| Melanoma | 8342 (782-34 305) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 4293 (2105-17 500) | |

| Breast | 4706 (2690-13 031) | |

| Lung | 6212 (1723-11 780) | |

| Gynecological | 6184 (4200-11 615) | |

| Other | 5647 (3231-8400) | |

| Treatment setting | ||

| Adjuvant | 7191 (5614-14 929) | .26 |

| Advanced or metastatic | 6025 (782-34 305) | |

| Single-arm | ||

| Yes | 6351 (782-24 360) | .24 |

| No | 5652 (1723-34 305) | |

| RCT evidence | ||

| Yes | 5812 (1723-34 305) | .75 |

| No | 6264 (782-10 933) | |

| Treatment linec | ||

| 1st | 6184 (1723-34 305) | .63 |

| 2nd and beyond | 6114 (782-32 480) | |

| Primary endpoint | ||

| OS | 6202 (2105-32 480) | .57 |

| PFS | 5376 (1723-34 305) | |

| RR | 6203 (2442-10 933) | |

| Other | 5521 (2442-14 929) | |

| Health-related quality of life | ||

| Assessed | 6184 (1723-34 305) | .17 |

| Not assessed | 4658 (782-11 615) | |

| ESMO-MCBS benefit | ||

| High | 6207 (1723-34 305) | <.001 |

| Low | 4437 (782-11 733) | |

| ESMO MCBS categoriesd | ||

| 1 | NA | .03 |

| 2 | 4898 (2690-11 733) | |

| 3 | 4164 (782-10 933) | |

| 4 | 6212 (1723-34 305) | |

| 5 | 6327 (6318-9035) | |

| A | 7191 (5614-14 929) | |

| B | NA | |

Abbreviations: ESMO-MCBS, European Society for Medical Oncology-Magnitude of Benefit Scale; NA, not available; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RR, response rate.

Prices reported in US$ after applying the exchange rate of September 3, 2022.

P values are unadjusted.

Treatment line applicable to medicines in advanced or metastatic setting.

There were no positive CADTH recommendations with an ESMO-MCBS score of 1 or B.

Figure. Association Between Improvement in OS and PFS and Monthly Drug Costs.

A total of 4 outliers were removed for consistency.

Discussion

Unlike US or Europe, monthly prices in Canada significantly differed for cancer drugs with substantial benefit vs low benefit per MCBS scores. However, consistent with other studies,1,2 there was only a weak correlation between monthly drug prices and PFS or OS gains.

MCBS captures broader evidence including hazard ratios, quality of life, and toxicity. Thus, drug prices differing based on MCBS scores but not based simply on PFS or OS gains is a reassuring finding to the MCBS. However, MCBS is based solely on clinical trials, so the correlation of prices with population-level benefit remains unmeasured. These findings are important to consider for US policy makers as the legislations for price negotiation are under discussion.6 We have previously shown that drugs that receive a positive reimbursement recommendation in Canada, in general, have better quality of evidence and magnitude of benefit than the drugs approved by the FDA.7 However, having a health technology assessment should not be presumed to directly cause better alignment of drug prices since previous studies from European nations have failed to find such association despite price negotiations.1,3

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Vokinger KN, Hwang TJ, Grischott T, et al. Prices and clinical benefit of cancer drugs in the USA and Europe: a cost-benefit analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):664-670. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30139-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miljković MD, Tuia JE, Olivier T, Haslam A, Prasad V. Association between US drug price and measures of efficacy for oncology drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration from 2015 to 2020. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(12):1319-1320. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trotta F, Mayer F, Barone-Adesi F, et al. Anticancer drug prices and clinical outcomes: a cross-sectional study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e033728. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherny NI, Dafni U, Bogaerts J, et al. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2340-2366. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canada’s Drug and Health Technology Agency . Reimbursement Review Reports. Updated January 2, 2023. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.cadth.ca/reimbursement-review-reports

- 6.Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Act, HR 2139, 117th Cong (2021). Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2139

- 7.Meyers DE, Jenei K, Chisamore TM, et al. Evaluation of the clinical benefit of cancer drugs submitted for reimbursement recommendation decisions in Canada. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):499-508. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement