Abstract

The major facilitator superfamily (MFS) is one of the two largest families of membrane transporters found on Earth. It is present ubiquitously in bacteria, archaea, and eukarya and includes members that can function by solute uniport, solute/cation symport, solute/cation antiport and/or solute/solute antiport with inwardly and/or outwardly directed polarity. All homologous MFS protein sequences in the public databases as of January 1997 were identified on the basis of sequence similarity and shown to be homologous. Phylogenetic analyses revealed the occurrence of 17 distinct families within the MFS, each of which generally transports a single class of compounds. Compounds transported by MFS permeases include simple sugars, oligosaccharides, inositols, drugs, amino acids, nucleosides, organophosphate esters, Krebs cycle metabolites, and a large variety of organic and inorganic anions and cations. Protein members of some MFS families are found exclusively in bacteria or in eukaryotes, but others are found in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. All permeases of the MFS possess either 12 or 14 putative or established transmembrane α-helical spanners, and evidence is presented substantiating the proposal that an internal tandem gene duplication event gave rise to a primordial MFS protein prior to divergence of the family members. All 17 families are shown to exhibit the common feature of a well-conserved motif present between transmembrane spanners 2 and 3. The analyses reported serve to characterize one of the largest and most diverse families of transport proteins found in living organisms.

“If you do not expect to, you will not discover the unexpected.”

Heraclitus

Transport systems allow the uptake of essential nutrients and ions, excretion of end products of metabolism and deleterious substances, and communication between cells and the environment (53). They also provide essential constituents of energy-generating and energy-consuming systems (54). Primary active transporters drive solute accumulation or extrusion by using ATP hydrolysis, photon absorption, electron flow, substrate decarboxylation, or methyl transfer (17). If charged molecules are unidirectionally pumped as a consequence of the consumption of a primary cellular energy source, electrochemical potentials result (54). The consequential chemiosmotic energy generated can then be used to drive the active transport of additional solutes via secondary carriers which merely facilitate the transport of one or more molecular species across the membrane (48, 49).

Recent genome-sequencing data and a wealth of biochemical and molecular genetic investigations have revealed the occurrence of dozens of families of primary and secondary transporters (63). Two such families have been found to occur ubiquitously in all classifications of living organisms. These are the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily (15, 21, 37, 44) and the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), also called the uniporter-symporter-antiporter family (7, 28, 30, 35, 51). While ABC family permeases are in general multicomponent primary active transporters, capable of transporting both small molecules and macromolecules in response to ATP hydrolysis (59), the MFS transporters are single-polypeptide secondary carriers capable only of transporting small solutes in response to chemiosmotic ion gradients. Although well over 100 families of transporters have now been recognized and classified (73), the ABC superfamily and MFS account for nearly half of the solute transporters encoded within the genomes of microorganisms (63). They are also prevalent in higher organisms. The importance of these two families of transport systems to living organisms can therefore not be overestimated.

The MFS was originally believed to function primarily in the uptake of sugars (36, 46). Subsequent studies revealed that drug efflux systems and Krebs cycle metabolites belong to this family (30, 62). The family was then expanded to include organophosphate:phosphate exchangers and oligosaccharide:H+ symport permeases (51). Reizer et al. (67) noted that a mammalian phosphate:Na+ symporter is a distant member of this family; Paulsen et al. (60) subdivided the MFS drug efflux pumps into two phylogenetically distinct families with differing topologies; and Goffeau et al. (26) identified a novel MFS family that consists exclusively of functionally uncharacterized proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed by genome sequencing. Recently, Williams and Shaw (86) noted that a family of bacterial aromatic acid permeases belongs to the MFS. These observations led to the probability that the MFS is far more widespread in nature and far more diverse in function than had been thought previously.

Although isolated reports have allowed recognition of an increasing degree of diversity within the MFS, there has been no recent systematic attempt to identify the sequenced proteins that make up the MFS and to classify these proteins into phylogenetic families. We have therefore undertaken this task in the hopes of allowing (i) recognition of the significance of this family to cell physiology; (ii) extrapolation of biochemical, molecular genetic, and biophysical information obtained from the study of a few such systems to all members of the family; (iii) unification of mechanistic models, to the greatest extent possible, so as to be applicable to a maximal number of transporters; (iv) introduction of a rational system of MFS protein classification; and (v) comprehension of the pathways taken in the development of structural and functional diversity resulting from the evolutionary process used.

In this report, we present analyses that allow us to generalize some previous observations regarding the MFS and to note additional characteristics of this immense superfamily. Thus, based exclusively on degrees of sequence similarity, we have constructed phylogenetic trees which allow us to divide all the recognized members of the MFS into 17 families. The members of each family all proved to be more closely related in sequence to each other than they were to any of the other MFS proteins. This fact presumably reflects the evolutionary histories of these proteins (71, 72), and, remarkably, we find that phylogenetic family correlates with function. Thus, each of the families recognizes and transports a distinct class of structurally related compounds. These observations have allowed us to derive a rational classification system for the MFS based on both phylogeny and function. This classification system has proven applicable to virtually all permeases found in nature (73).

In 1990, Rubin et al. (70) presented evidence that strongly argued in favor of an earlier suggestion (see reference 36), that MFS permeases arose by a tandem intragenic duplication event. In this report, we provide additional statistical evidence in favor of this possibility. This event generated the 12-transmembrane-spanner (TMS) protein topology from a primordial 6-TMS unit. Surprisingly, all currently recognized MFS permeases retain the two six-TMS units within a single polypeptide chain, although in 3 of the 17 MFS families, an additional two TMSs are found (60). Moreover, the well-conserved MFS-specific motif between TMS2 and TMS3 and the related but less well conserved motif between TMS8 and TMS9 (36) prove to be a characteristic of virtually all of the more than 300 MFS proteins identified. The functional significance of this repeated motif has been examined by Jessen-Marshall et al. (39) and by Yamaguchi et al. (87–89).

Many additional observations allowed the identification of highly specific characteristics of individual MFS families as well as general characteristics of the MFS as a whole. We hope that the computational analyses reported will provide a guide for molecular biologists, biochemists, and biophysicists interested in structural, functional, and evolutionary aspects of MFS permeases.

COMPUTER METHODS

The FASTA (64) and BLAST (2) programs were used to screen the peptide and translated nucleotide databases. The statistical significance of sequence similarities between putative members of the various families of the MFS was established by using the RDF2 (64) and GAP (16) programs with at least 200 random shuffles. Binary comparison scores are expressed in standard deviations (SD) (14). A value of 9 SD for a protein segment larger than 60 residues is deemed sufficient to establish homology (18, 71). This criterion was used to establish homology between MFS families (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Interfamilial comparison scores for representative members of families 7 to 17a

| Protein 1 | Family | Protein 2 | Family | Comparison scores (SD) | % Identity | No. of residues compared | No. of gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FucP | 7, FGHS | Gtr5 | 1, SP | 8 | 21 | 125 | 0 |

| NasA | 8, NNP | YidT | 14, ACS | 13 | 21 | 150 | 0 |

| Ph84 | 9, PHS | Itr1 | 1, SP | 10 | 24 | 586 | 19 |

| NupG | 10, NHS | CscB | 5, OHS | 12 | 19 | 415 | 8 |

| YhjX | 11, OFA | Ykw1 | 13, MCP | 11 | 18 | 402 | 5 |

| NanT | 12, SHS | CitA | 6, MHS | 10 | 25 | 407 | 11 |

| Mot1 | 13, MCP | NanT | 12, SHS | 10 | 17 | 494 | 5 |

| GudT | 14, ACS | Bmr1 | 3, DHA12 | 12 | 22 | 389 | 8 |

| YheO | 15, UMF | Sge1 | 2, DHA14 | 12 | 18 | 543 | 5 |

| PcaK | 16, AAHS | GudT | 14, ACS | 13 | 18 | 438 | 5 |

| YycB | 17, CP | NarK | 8, NNP | 10 | 21 | 408 | 6 |

Comparison scores expressed in standard deviations (SD) were determined with the GAP program with 500 random shuffles. Family and protein abbreviations are as indicated in Table 1 and Tables 3 to 17, respectively, with the exception of proteins from families 2 (DHA14) and 3 (DHA12), which are tabulated in reference 60.

Multiple-sequence alignments were constructed with the PREALIGN and TREE programs of Feng and Doolittle (22) and the PILEUP program (16). Phylogenetic analyses were routinely performed with the TREE program (22) but were checked with other programs. The different programs generally gave very similar, and often identical, branching orders, and the branch lengths were also strikingly similar. Branch length is approximately proportional to the degree of sequence divergence, which, to a first approximation, is assumed to be proportional to the phylogenetic distance (but see the section Conclusions and Perspectives, below). It is important to emphasize that branch lengths and even branch positions represent approximations to the evolutionary process, allowing facile visualization of the relationships between sequences within families. They reflect relative degrees of sequence divergence and can be considered to represent the evolutionary process only to a first approximation (71, 72).

Average hydropathy, average amphipathicity and average similarity analyses were conducted for all protein families analyzed. They were based on the complete multiple-sequence alignments generated with the TREE program. Only representative, well-conserved portions of these multiple-sequence alignments are presented. The hydropathy analyses were conducted with the assumptions and algorithm described by Kyte and Doolittle (45) with a sliding window of 20 residues. Similarly, a sliding window of 20 residues was used to generate the average similarity and average amphipathicity plots (45a). These latter analyses are not presented but are described in the text (see Table 2).

Charge bias analysis of membrane protein topology was performed with the program TOP PRED (83). Signature sequences were defined by the method of Bairoch et al. (6). The programs MEME and MAST (5) were used to help identify conserved motifs within the protein families of the MFS. Most of the methods used in this study have been applied to numerous transport proteins and have been evaluated (see references 71 and 72 for recent reviews).

SEVENTEEN MFS FAMILIES

Table 1 lists and summarizes the properties of transport protein families found within the current MFS. We have classified current members of the MFS into 17 (possibly 18) distinct families. This number of MFS families represents more than a threefold expansion over that published previously (51). The table provides the family number; the name of the family; the abbreviation of the family to be used in this study; the number of currently recognized sequenced members in each family; the range of organisms in which members of the family are found; the size range of the proteins (in numbers of amino acyl residues) for fully sequenced members; the number of putative TMSs in each protein (believed to be uniform for members of a given family); the energy-coupling mechanisms, if any, used by members of the family; the polarities of transport catalyzed by family members; the substrates known to be transported by various members of the family; and a representative and well-characterized member of the family.

TABLE 1.

Families within the MFS

| Family no. | Family name | Abbreviation | No. of proteins | Source(s)a | Size range (aa) | Putative TMSs (no.) | Mechanism(s) | Polarities | Substrates | Representative example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sugar porter | SP | 133 | Bac, Ar, Pr, Y, An, Pl | 404–818 | 12 | Sugar uniport Sugar:proton symport Sugar:sugar antiport | None In Both | Monosaccharides (hexoses, pentoses), disaccharides, quinate, organo-cations, inositols | XylE of E. coli |

| 2 | Drug:H+ antiporter (14 TMS) | DHA14 | 30 | Bac, Y | 14 | Drug:H+ antiport | Out | Multiple or single drugs | QacA of S. aureus | |

| 3 | Drug:H+ antiporter (12 TMS) | DHA12 | 46 | Bac, Ar, Y, An | 12 | Drug:H+ antiport | Out | Multiple or single drugs | Bmr of B. subtilis | |

| 4 | Organophosphate:Pi antiporter | OPA | 12 | Bac, An | 439–495 | 12 | Organo phosphate:Pi antiport | Both | Sugar-phosphates, glycerol phosphate, phosphoglycerates, phosphoenolpyruvate | UhpT of E. coli |

| 5 | Oligosaccharide:H+ symporter | OHS | 6 | Bac | 415–425 | 12 | Sugar:H+ symport Sugar:sugar antiport | In Both | Di- and trisaccharides | LacY of E. coli |

| 6 | Metabolite:H+ symporter | MHS | 16 | Bac | 425–500 | 12 | Solute:H+ symport | In | Citrate, α-ketoglutarate, proline, betaine, methylphthalate, dicarboxylates | KgtP of E. coli |

| 7 | Fucose-galactose-glucose:H+ symporter | FGHS | 4 | Bac | 404–438 | 12 | Hexose uniport Hexose:H+ symport | None In | l-Fucose, glucose, galactose | FucP of E. coli |

| 8 | Nitrate/nitrite porter | NNP | 13 | Bac, Y, Pl | 395–547 | 12 | Nitrite uniport? Nitrate:H+ symport? | Out In | Nitrite, nitrate | NarK of E. coli |

| 9 | Phosphate:H+ symporter | PHS | 11 | Y, Pl | 518–587 | 12 | Pi:H+ symport | In | Inorganic phosphate | Pho-5 of N. crassa |

| 10 | Nucleoside:H+ symporter | NHS | 2 | G− Bac | 418 | 12 | Nucleoside:H+ symport | In | Nucleosides | NupG of E. coli |

| 11 | Oxalate:formate antiporter | OFA | 5 | Bac, Ar, An | 373–470 | 12 | Anion:anion antiport | Both | Oxalate, formate | OxlT of O. formigenes |

| 12 | Sialate:H+ symporter | SHS | 3 | G− Bac | 407–496 | 14 | Substrate:H+ symport | In | Sialate | NanT of E. coli |

| 13 | Monocarboxylate porter | MCP | 13 | Y, An | 450–808 | 12 | Substrate:H+ symport | In | Pyruvate, lactate, mevalonate | Mct of H. sapiens |

| 14 | Anion:cation symporter | ACS | 40 | Bac, Y, An | 411–596 | 12 | Substrate:H+ or Na+ symport | In | Glucarate, hexuronate, tartrate, 4-hydroxyphenyl acetate, inorganic phosphate, allantoate | ExtU of E. coli |

| 15 | Aromatic acid:H+ symporter | AAHS | 7 | Bac | 418–460 | 12 | Substrate:H+ symport | In | Muconate, benzoate; 4-hydroxybenzoate; 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetate, protocatachurate, 3-hydroxypropionate | PcaK of P. putida |

| 16 | Unknown major facilitator | UMF | 6 | Y | 600–637 | 14 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yh1040c of S. cereisiae |

| 17 | Cyanate permease | CP | 3 | Bac | 393–402 | 12 | Substrate:H+ symport? | In | NCO− | CynX of E. coli |

| 18 | Proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter | POT | 24 | Bac, Y, An, Pl | 463–783 | 12 | Substrate:H+ symport | In | Peptides, amino acids, nitrate, chlorate, nitrite | DtpT of L. lactis |

The abbreviations for source organisms used here and in all subsequent tables are as follows: Bac, bacteria; G−, gram negative; Ar, archaea; Pr, eukaryotic protists (usually protozoans); Y, yeasts; F, fungi; Pl, plants; An, animals.

The largest family (family 1) is the sugar porter (SP) family, with 133 identified members. These proteins are derived from all of the major groups of living organisms: bacteria, archaea, eukaryotic protists, fungi, mostly yeasts, animals, and plants. These proteins have 12 established or putative TMSs. They can function by uniport, solute:solute antiport, and/or solute:cation symport, depending on the system and/or conditions. Uniporters exhibit no polarity but can usually catalyze both uniport and antiport depending on whether a substrate is present on the trans side of the membrane. The polarity of solute:solute antiporters is indicated in Table 1 by “both.” Symporters function with inwardly-direct polarity in the presence of a membrane potential (negative inside), but many of these proteins have also been shown to catalyze antiport when a substrate is present on the trans side of the membrane. Substrates transported by SP family members include hexoses, pentoses, disaccharides, quinate, inositols, and organic cations. Most but not all members of the SP family thus catalyze sugar transport.

Family 1 permeases exhibit a size range of 404 to 818 residues. The smaller permeases possess very short hydrophilic N and C termini and short loops connecting the 12 TMSs. As is true of many MFS families, the bacterial sugar porters are usually smaller than the eukaryotic proteins. The larger sizes of the eukaryotic proteins are due to large hydrophilic N and/or C termini or, less frequently, to increased sizes of specific inter-TMS loops. The hydrophilic regions of the eukaryotic proteins may play roles in regulation or in cytoskeletal attachment, and they are frequently subject to phosphorylation by ATP-dependent protein kinases. A representative well-characterized example of the SP family is the arabinose:H+ symport permease (AraE) of Escherichia coli (47).

Families 2 and 3 consist of drug efflux systems which possess 14 and 12 TMSs, respectively (74). Since these permeases uniformly catalyze drug:H+ antiport, they are referred to as the DHA14 and DHA12 families, respectively. A total of 30 and 46 sequenced members are currently recognized in these two families. Because these permeases have recently been the subject of an extensive review which presented multiple alignments and phylogenetic trees (60), they will not be described or analyzed here. Members of both families are found in bacteria and eukaryotes, and DHA12 family members have also been identified in archaea.

Families 4, 5, and 6, the organophosphate:inorganic phosphate antiporters (OPA), the oligosaccharide:H+ symporters (OHS), and the metabolite:H+ symporters (MHS), respectively, were recognized to be families within the MFS in 1993 (30, 51). Since these permeases are restricted to bacteria, it is not surprising that they are all relatively small (400 to 500 residues). All three of these families have become substantially larger and more diverse in function since 1993, due to the sequencing and functional identification of new members.

All the remaining families listed in Table 1 (families 7 to 18) were not recognized in 1993 and are therefore new MFS families. Family 7 (the fucose-galactose-glucose:H+ symporters [FGHS]) is a small family with four distantly related members. As with most members of the SP family, these proteins are specific for sugars. They all probably function by proton symport. They are relatively small (404 to 438 residues), as expected since they are derived exclusively from bacteria.

The nitrate-nitrite porter (NNP) family (family 8) has members in bacteria, yeasts, and plants. Not surprisingly, these proteins exhibit a larger size range (395 to 547 residues) than was observed for FGHS family members. These proteins catalyze either nitrate uptake or nitrite efflux. The energy-coupling mechanisms are not well defined.

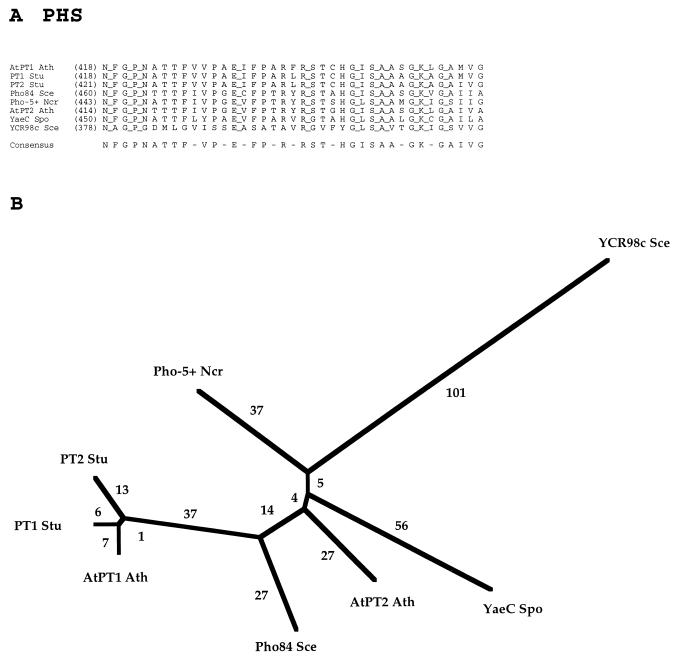

Family 9, the phosphate:H+ symporter (PHS) family, has sequenced representatives only in yeast and plants. The 11 proteins of the PHS family are fairly uniform in size, but they are substantially larger than most bacterial MFS proteins (518 to 587 residues). The characterized members are uniform in function.

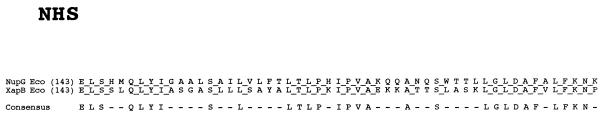

Family 10, the nucleoside:H+ symporter (NHS) family, has only two bacterial members, and they are of the same size (418 residues each). They are both from E. coli and differ in specificity.

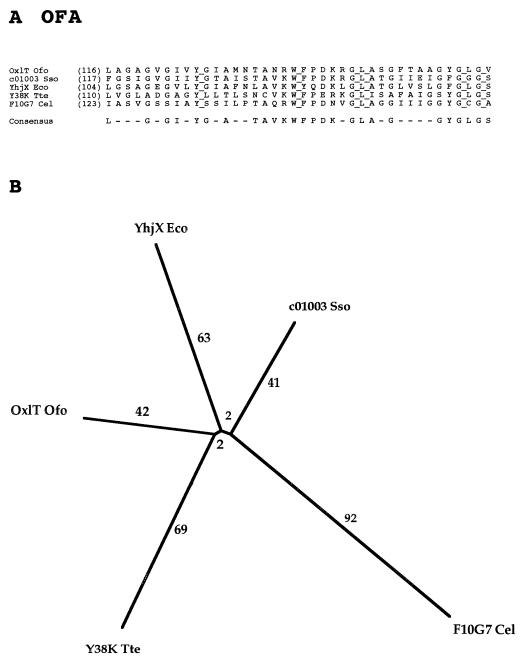

Family 11, the oxalate/formate antiporter (OFA) family, is a small but diverse family. Only five members have been sequenced, but these proteins are found in the bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic kingdoms. Surprisingly, they are of fairly uniform size (373 to 470 residues). The very small size of one of these proteins (see below) raises the possibility that its sequence is incomplete.

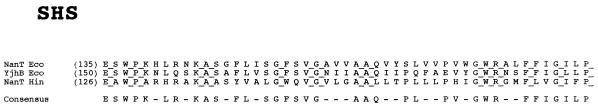

Family 12, the sialate:H+ symporter (SHS) family, like the NHS family, is very small (with only three members), and, again like the NHS family, the members are all derived from gram-negative bacteria. Their sizes are consistent with those generally observed for bacterial MFS proteins (407 to 496 residues). These proteins differ from most MFS proteins in possessing 14 putative TMSs.

Family 13, with 13 members derived exclusively from yeasts and animals, is the monocarboxylate porter (MCP) family. These permeases transport pyruvate, lactate, and/or mevalonate with inwardly-directed polarity. They all presumably function by proton symport. Their reported sizes range from 450 to 808 residues.

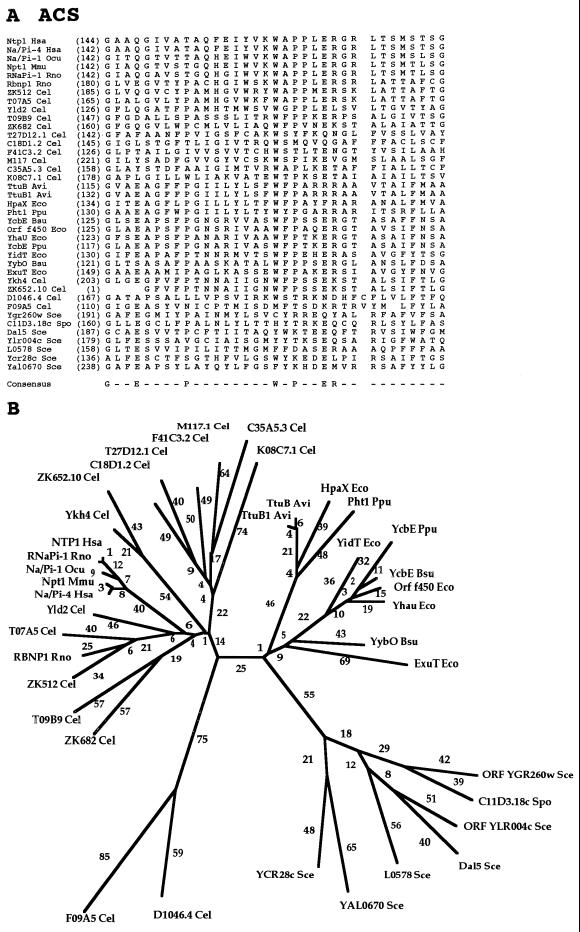

Family 14, the anion:cation symporter (ACS) family, is a relatively large family with 40 sequenced members. The proteins are derived from bacteria, yeasts, and animals, and they exhibit an intermediate range of sizes (411 to 596 residues). They accumulate their substrates in symport with either Na+ or H+, depending on the system. They may transport either inorganic anions (e.g., phosphate) or organic anions (e.g., glucarate, hexuronate, tartrate, allantoate, or 4-hydroxylphenyl acetate). Of the functionally characterized porters, the inorganic anion porters of the ACS family cotransport Na+ while the organic anion porters cotransport H+.

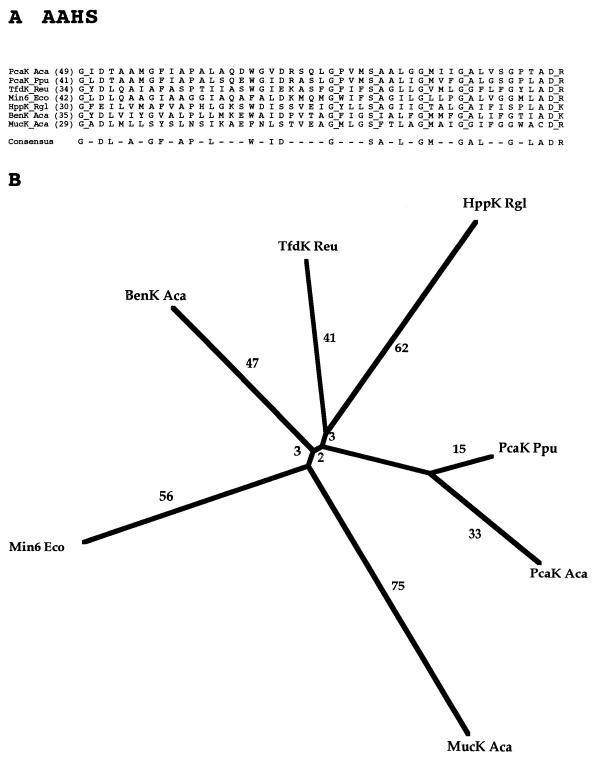

Family 15, the aromatic acid:H+ symporter (AAHS) family, consists of seven sequenced proteins, all from bacteria. As expected, these porters show fairly uniform sizes (418 to 460 residues), all on the low end of the scale. They transport a variety of aromatic acids as well as cis,cis-muconate, as indicated in Table 1. Interestingly, one member of the family has been implicated in chemotaxis, allowing the bacteria to swim up concentration gradients of its substrates (34). This is the only documented case where an MFS protein apparently serves as a chemoreceptor. One of the AAHS proteins (BenK Aca) transports benzoate (11). Two additional (putative) benzoate:H+ symporters (BenE) have been sequenced. They are both derived from gram-negative bacteria. One is the functionally characterized BenE protein of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, and the other is a closely related protein from E. coli (55). These two proteins both contain a single region that exhibits limited sequence similarity to family 15 porters, as might be expected on the basis of the specificity of the A. calcoaceticus protein. However, they are very divergent in sequence from the latter proteins and cannot be shown to be homologous to any member of the MFS. They are therefore included in a separate family designated the benzoate:H+ symporter (BenE; TC #2.46) family (72a).

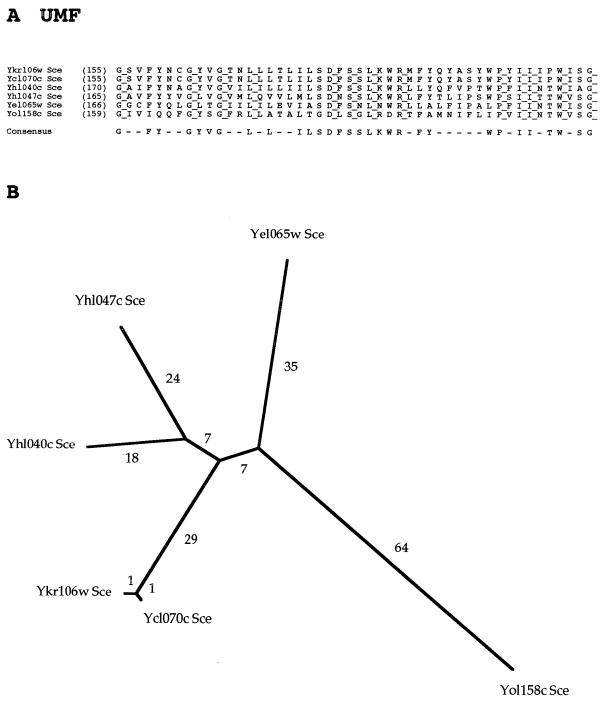

Six members of a novel family, family 16, the unknown major facilitator (UMF) family, have recently been identified (26). Although it has been proposed that these carriers are drug efflux pumps, no member of this family has been functionally characterized, and consequently the designation UMF has tentatively been assigned to this family. All six currently recognized members of the family are from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and no close homologs are found in other organisms. These proteins exhibit the less common putative 14-TMS topology observed for only two other MFS families. The proteins of the UMF family exhibit almost no size variation (range, 606 to 637 residues).

Family 17, the cyanate permease (CP) family, includes only three proteins, all from bacteria. They are small proteins (393 to 402 residues with 12 TMSs). The substrate of one of these proteins (CynX of E. coli) is believed to be cyanate (NCO−). The other two members, from E. coli and Bacillus subtilis, are strikingly divergent in sequence but not in size, as noted above.

The proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter (POT) family has been described previously (62, 78). We have observed sequence similarities of these proteins to members of the SP and DHA14 families (see below). Although this similarity is insufficient to establish homology, the similarities in sequence, mechanism, and topology between proteins of the POT family and those of several MFS families strongly suggest that the POT family is a distant constituent of the MFS.

ESTABLISHMENT OF HOMOLOGY FOR MFS PROTEINS

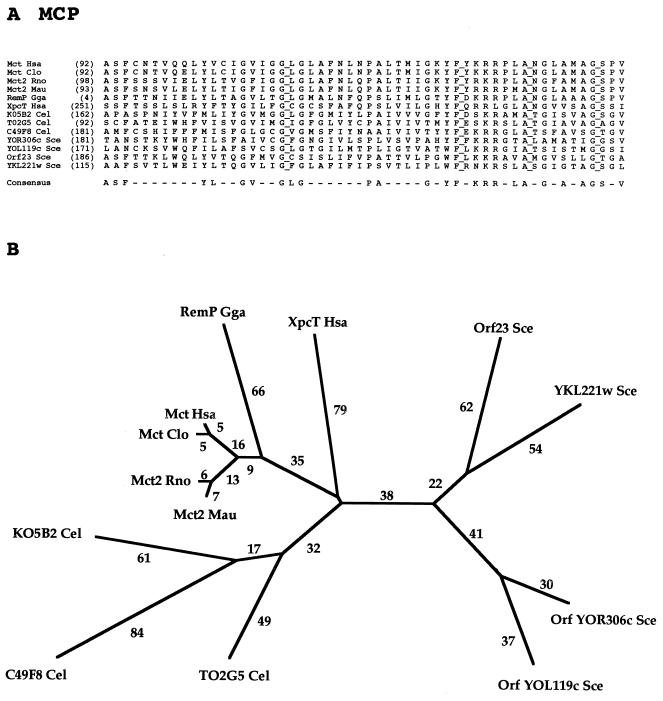

Proteins within any one family of the MFS exhibit fairly extensive sequence similarities, as revealed by the portions of the multiple alignments shown in Fig. 3 to 17. Intrafamily comparison scores are always in excess of 15 SD, thus easily establishing that the members of any one family are homologous. However, sequence similarity for any two proteins derived from different MFS families is much less extensive. We therefore conducted interfamily binary comparisons to establish homology for all MFS families (18, 71). Homology for families 1 to 6 has been established previously (51). The results of the present comparisons are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1.

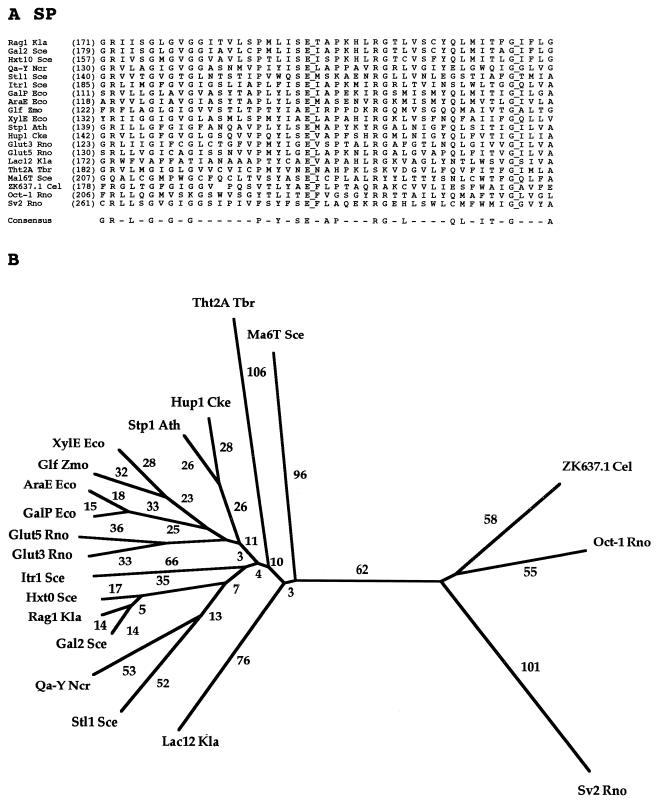

FIG. 3.

Partial multiple alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for representative members of the SP family (family 1) of the MFS. The format of presentation for this figure is essentially the same as for subsequent family-specific figures (Fig. 4 to 17), as follows. (A) The abbreviation of each protein, provided in Table 3, is followed by the residue number in the protein, presented in parentheses, corresponding to the first residue in the alignment shown. Fully conserved residues are highlighted with a line to the right of that residue. A residue appears in the consensus sequence (bottom) if that residue occurs at the specified position in a majority of the aligned proteins. In the phylogenetic tree (B), the branch length (numerical values in arbitrary units) is a measure of sequence divergence and is assumed to be approximately proportional to the phylogenetic distance. The tree was based on the complete multiple-sequence alignment for the proteins included in the study. Both the multiple-sequence alignment and the phylogenetic tree were derived with the TREE program of Feng and Doolittle (22).

FIG. 17.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment for the three members of the CP family (family 17).

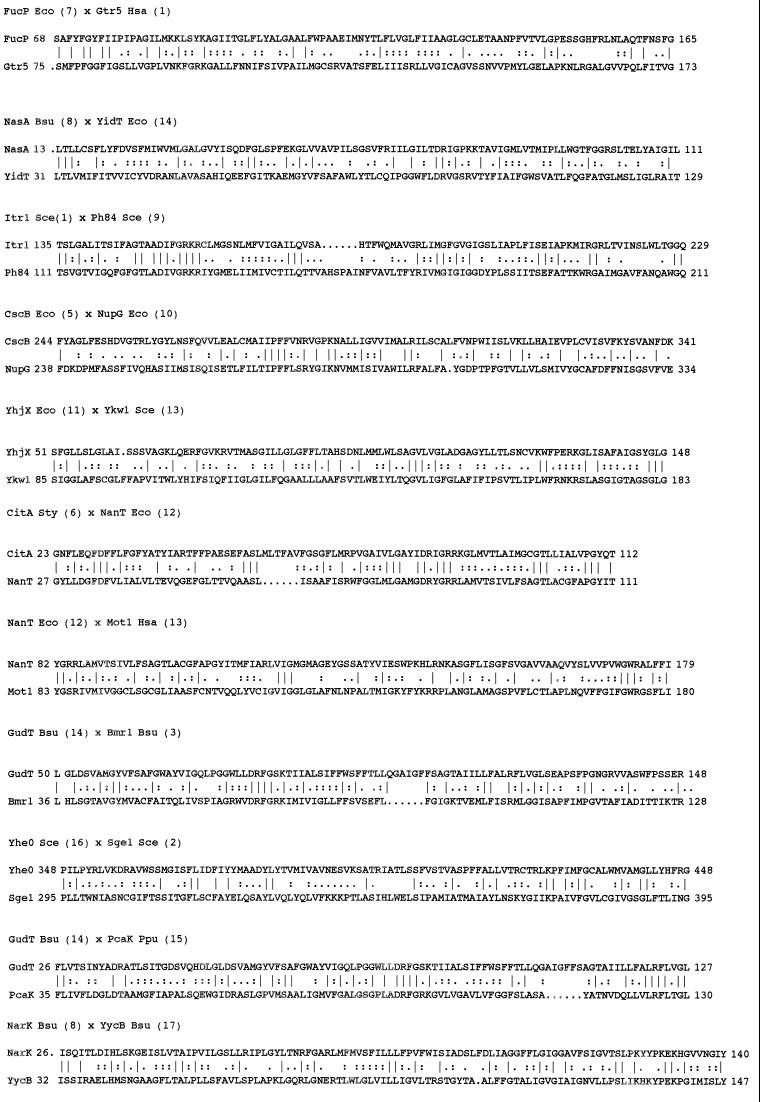

FIG. 1.

Interfamily binary alignments of representative regions within the larger alignments upon which the comparison scores recorded in Table 2 were based. The two proteins compared (families in parentheses) are presented above the alignment. Protein abbreviations are as indicated in Tables 3 to 17 for families 3 to 17, respectively. The number following the protein abbreviation and preceding its sequence is the residue number of the first residue shown. A vertical line specifies an identity, while double and single dots signify close and distant similarities, respectively.

As noted above, families 1 to 6 and family 16 have already been shown to be constituent families of the MFS (26, 51, 60). The data presented in Table 2 establish that families 7 to 17 (described above) are all constituents of the MFS. In the case of FucP of family 7 (FGHS), 21% identity (8 SD) was observed with Gtr5 of family 1 in a region of 125 residues that exhibits no gaps in the binary alignment. Gtr5 is an established member of family 1 of the MFS (see Table 3). Of the comparison scores recorded in Table 2, this is the only score below 10 SD, and most of the other sequences compared include all or most of the two proteins compared. Family 7 is therefore the only family included in Table 2 that is not fully established as an MFS constituent. Other considerations provide additional support for the conclusion that the FGHS family is in fact a member of the MFS (see below).

TABLE 3.

Members of the SP family (family 1)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Data- baseb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AraE Eco | Arabinose-proton symporter | B | Escherichia coli | 472 | P09830 | SP |

| AraE Kox | Arabinose-proton symporter | B | Klebsiella oxytoca | 472 | P45598 | SP |

| GalP Eco | Galactose-proton symporter | B | Escherichia coli | 464 | P37021 | SP |

| Glf Zmo | Glucose facilitated diffusion protein | B | Zymomonas mobilis | 473 | P21906 | SP |

| Gtr Ssp | Glucose transport protein | B | Synechocystis sp. | 468 | P15729 | SP |

| Orf_f469 Eco | Putative sugar transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 469 | U29579 | GB |

| Orf ZZ Shy | Putative monosaccharide transporter (fragment) | B | Streptomyces hygroscopicus | 290 | X86780 | GB |

| XylE Eco | Xylose-proton symporter | B | Escherichia coli | 491 | P09098 | SP |

| YaaU Eco | Putative sugar transporter (frameshift error?) | B | Escherichia coli | 220 | P31578 | SP |

| YfiG Bsu | Putative sugar transporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 482 | P54723 | SP |

| YncC Bsu | Putative sugar transporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 419 | U66480 | GB |

| YxbC Bsu | Putative sugar transporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 388 | P46333 | SP |

| YxdF Bsu | Putative sugar transporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 439 | P42417 | SP |

| YyaJ Bsu | SV2 homolog | B | Bacillus subtilis | 451 | P37514 | SP |

| Str Ssp | Sugar transporter | Ar | Sulfolobus solfataricus | 423 | Y08256 | GB |

| Gtr1 Ldo | Putative glucose transporter | Pr | Leishmania donovani | 547 | Q01440 | SP |

| Glut2 Ldo | Putative sugar transporter | Pr | Leishmania donovani | 558 | Q01441 | SP |

| HT1 Tvi | Glucose transporter | Pr | Trypanosoma vivax | 543 | L47540 | GB |

| Pro-1 Ldo | Putative sugar transporter | Pr | Leishmania donovani | 567 | P13865 | SP |

| TcrHT1 Tcr | Hexose transporter | Pr | Trypanosoma cruzi | 544 | U05588 | GB |

| Tht1E Tbr | Glucose transporter 1E | Pr | Trypanosoma brucei brucei | 528 | Q09037 | SP |

| Tht2A Tbr | Glucose transporter 2A | Pr | Trypanosoma brucei brucei | 529 | Q06222 | SP |

| Tht2B Tbr | Glucose transporter 1B/1C/1D/1F/2B | Pr | Trypanosoma brucei brucei | 527 | Q06221 | SP |

| Tht2C Tbr | Glucose transporter 2C (fragment) | Pr | Trypanosoma brucei brucei | 337 | Q09039 | SP |

| Ag1 Sce | α-Glucoside transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 617 | S59368 | GB |

| Gal2 Sce | Galactose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 574 | P13181 | SP |

| Glu Ssp | Putative glucose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces sp. | 518 | L21753 | GB |

| Hgt1 Kla | High-affinity glucose transporter | Y | Kluyveromyces lactis | 551 | P49374 | SP |

| Hxt1 Sce | Low-affinity glucose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 570 | P32465 | SP |

| Hxt2 Sce | High-affinity glucose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 541 | P23585 | SP |

| Hxt3 Sce | Low-affinity glucose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 567 | P32466 | SP |

| Hxt4 Sce | Glucose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 576 | P32467 | SP |

| Hxt5 Sce | Glucose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 592 | P38695 | SP |

| Hxt6 Sce | Hexose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 570 | P39003 | SP |

| Hxt7 Sce | Hexose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 570 | P39004 | SP |

| Hxt8 Sce | Putative hexose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 569 | P40886 | SP |

| Hxt10 Sce | Putative hexose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 546 | P43581 | SP |

| Hxt11 Sce | Putative hexose transporter; drug resistance? | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 567 | P40885 | SP |

| Hxt13 Sce | Putative hexose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 564 | P39924 | SP |

| Hxt14 Sce | Putative hexose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 540 | P42833 | SP |

| Hxt16 Sce | Putative sugar transport protein | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 567 | P47185 | SP |

| Hxt17 Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 343 | Z71687 | GB |

| Itr1 Sce | myo-Inositol transporter 1 | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 584 | P30605 | SP |

| Itr1 Spo | myo-Inositol transporter | Y | Saccharomyces pombe | 575 | X98622 | GB |

| Itr2 Sce | myo-Inositol transporter 2 | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 612 | P30606 | SP |

| Kht2 Kla | Putative hexose transporter | Y | Kluyveromyces marxianus | 566 | S51081 | PIR |

| Lac12 Kla | Lactose/galactose transporter | Y | Kluyveromyces lactis | 587 | P07921 | SP |

| Mal3T Sce | Maltose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 614 | P38156 | SP |

| Mal6T Sce | Maltose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 614 | P15685 | SP |

| Rag1 Kla | Low-affinity glucose transporter | Y | Kluyveromyces lactis | 567 | P18631 | SP |

| Rgt2 Sce | High glucose sensor | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 763 | X96876 | GB |

| YacI Spo | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Schizo saccharomyces pombe | 522 | Q10710 | SP |

| Ybr241c Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 488 | P38142 | SP |

| Yd1199c Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 687 | S58778 | PIR |

| Ydr387c Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 555 | U32274 | GB |

| Yfl040w Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 540 | P43562 | SP |

| Ygk4 Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 486 | Z72626 | GB |

| Yil170w Sce | Putative sugar transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 457 | P40441 | SP |

| Yjr160c Sce | Putative maltose transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 602 | P47186 | SP |

| Snf3 Sce | Low glucose sensor | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 818 | P10870 | SP |

| Stl1 Sce | Putative sugar transporter Stl1 | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 569 | P39932 | SP |

| Rco3 Ncr | Sugar transporter | F | Neurospora crassa | 594 | U54768 | GB |

| Qa-Y Ncr | Quinate transporter | F | Neurospora crassa | 537 | P11636 | SP |

| QutD Eni | Quinate transporter | F | Emericella nidulans | 533 | P15325 | SP |

| Glu2 Ssp | Putative glucose transporter (fragment) | Pl | Saccharum sp. | 287 | L21752 | GB |

| Hex6 Rco | Hexose transporter | Pl | Ricinus communis | 510 | L08188 | GB |

| Hup1 Cke | Hexose-proton symporter | Pl | Chorella kessleri | 533 | P15686 | SP |

| Hup2 Cke | Galactose-proton symporter | Pl | Chorella kessleri | 540 | X66855 | GB |

| Hup3 Cke | Glucose transporter | Pl | Chorella kessleri | 534 | S38435 | PIR |

| Int Hvu | Putative sugar transporter | Pl | Beta vulgaris | 490 | U43629 | GB |

| Mst1 Nta | Monosaccharide transport protein | Pl | Nicotiana tabacum | 523 | S25015 | PIR |

| MtSt1 Mtr | Putative sugar transporter | Pl | Medicago truncatula | 518 | U38651 | GB |

| Stc Rco | Sugar transporter | Pl | Ricinus communis | 523 | L08196 | GB |

| Stp1 Ath | Glucose transporter | Pl | Arabidopsis thaliana | 522 | P23586 | SP |

| Stp4 Ath | Monosaccharide transport protein | Pl | Arabidopsis thaliana | 514 | S25009 | PIR |

| B0252 Cel | B0252.3 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 435 | U23453 | GB |

| C44C10.3 Cel | C44C10.3 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 404 | Z69787 | GB |

| C46C2.2 Cel | C46C2.2 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 517 | Z68296 | GB |

| C53B4.1 Cel | C53B4.1 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 517 | Z68215 | GB |

| F11D5 Cel | F11D5.4/F11D5.5 (putative sugar transporter-frameshift) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 361/192 | U41532 | GB |

| F13B12.2 Cel | F13B12.2 (putative glucose transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 431 | Z70683 | GB |

| F14B8.3 Cel | Putative organic cation transporter | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 524 | U28737 | GB |

| F14E5.1 Cel | F14E5.1 (putative sugar transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 466 | Z66522 | GB |

| F14E5.1 Cel | F14E5.1 (putative glucose transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 493 | Z66522 | GB |

| F23F12.5 Cel | Putative organic cation transporter | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 751 | P46501 | SP |

| F48E3 Cel | F48E3.2 (putative glucose transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 488 | U28735 | GB |

| F53H8 Cel | Similar to glucose transporter | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 569 | U41023 | GB |

| Glu Dme | Putative glucose transporter | An | Drosophila melanogaster | 507 | U31961 | GB |

| Glut1 Bta | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Bos taurus | 492 | P27674 | SP |

| Glut1 Gga | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Gallus gallus | 490 | P46896 | SP |

| Glut1 Hsa | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Homo sapiens | 492 | P11166 | SP |

| Glut1 Mmu | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Mus musculus | 492 | P17809 | SP |

| Glut1 Ocu | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Oryctolagus cuniculus | 492 | P13355 | SP |

| Glut1 Rno | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Rattus norvegicus | 492 | P11167 | SP |

| Glut1 Ssc | Glucose transporter type 1, erythrocyte | An | Sus scrofa | 451 | P20303 | SP |

| Glut2 Gga | Glucose transporter | An | Gallus gallus | 533 | S37476 | PIR |

| Glut2 Hsa | Glucose transporter type 2, liver | An | Homo sapiens | 524 | P11168 | SP |

| Glut2 Mmu | Glucose transporter type 2, liver | An | Mus musculus | 523 | P14246 | SP |

| Glut2 Rno | Glucose transporter type 2, liver | An | Rattus norvegicus | 522 | P12336 | SP |

| Glut3 Cfa | Glucose transporter type 3, brain | An | Canis familiaris | 495 | P47842 | SP |

| Glut3 Gga | Glucose transporter type 3, brain | An | Gallus gallus | 496 | P28568 | SP |

| Glut3 Hsa | Glucose transporter type 3, brain | An | Homo sapiens | 496 | P11169 | SP |

| Glut3 Mmu | Glucose transporter type 3, brain | An | Mus musculus | 493 | P32037 | SP |

| Glut3 Oar | Glucose transporter type 3, brain | An | Ovis aries | 494 | P47843 | SP |

| Glut3 Rno | Glucose transporter type 3, brain | An | Rattus norvegicus | 493 | Q07647 | SP |

| Glut4 Hsa | Glucose transporter type 4, insulin | An | Homo sapiens | 509 | P14672 | SP |

| Glut4 Mmu | Glucose transporter type 4, insulin | An | Mus musculus | 510 | P14142 | SP |

| Glut4 Rno | Glucose transporter type 4, insulin | An | Rattus norvegicus | 509 | P19357 | SP |

| Glut5 Hsa | Fructose transporter | An | Homo sapiens | 501 | P22732 | SP |

| Glut5 Ocu | Glucose transporter type 5, small intestine | An | Oryctolagus cuniculus | 486 | P46408 | SP |

| Glut5 Rno | Glucose transporter type 5, small intestine | An | Rattus norvegicus | 502 | P43427 | SP |

| Glut7 Rno | Glucose transporter type 7, hepatic | An | Rattus norvegicus | 528 | Q00712 | SP |

| GT2 Mmu | Glucose transporter | An | Mus musculus | 508 | B30310 | PIR |

| GTP1 Tso | Glucose transporter | An | Taenia solium | 510 | U39197 | GB |

| K05F1 Cel | K05F1.6 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 745 | U29377 | GB |

| K09C4 Cel | Putative glucose transporter | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 520 | U43375 | GB |

| Ksp Mmu | Putative organic cation transporter | An | Mus musculus | 545 | U52842 | GB |

| M01F1 Cel | M01F1.5 (putative hexose transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 628 | Z46381 | GB |

| Nit Rno | Putative organic cation transporter | An | Rattus norvegicus | 514 | L27651 | GB |

| Oct-1 Rno | Organic cation transporter | An | Rattus norvegicus | 556 | X78855 | GB |

| Oct-2 Rno | Organic cation transporter | An | Rattus norvegicus | 593 | D83045 | GB |

| SGTP1 Sma | Glucose transporter | An | Schistosoma mansoni | 521 | A53153 | GB |

| SGTP2 Sma | Glucose transporter | An | Schistosoma mansoni | 489 | B53153 | PIR |

| SGTP4 Sma | Glucose transporter | An | Schistosoma mansoni | 505 | C53153 | PIR |

| SV2 Rno | SV2 synaptic vesicle protein | An | Rattus norvegicus | 742 | S27263 | PIR |

| SV2 Rno | Synaptic vesicle protein 2 | An | Rattus norvegicus | 742 | Q02563 | SP |

| T05A1.5 Cel | T05A1.5 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 498 | Z68219 | GB |

| T05A1.7 Cel | T05A1.7 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 251 | Z68219 | GB |

| ZK455.8 Cel | ZK455.8 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 447 | Z66567 | GB |

| ZK563 Cel | ZK563.1 (fragment) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | >357 | U40061 | GB |

| ZK637.1 Cel | Putative organic cation transporter | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 536 | P30638 | SP |

| ZK829.9 Cel | ZK829.9 (putative glucose transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 351 | Z73899 | GB |

| ZK892.3 Cel | ZK892.3 (putative organic cation transporter) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 541 | Z48638 | GB |

B, bacterium; Ar, archaea; Pr, protozoan; Y, yeast; F, fungus; Pl, plant; An, animal.

SP, SwissProt; GB, GenBank; PIR, Protein Information Resource.

NasA of family 8 exhibits a comparison score of 13 SD with 21% identity to YidT of family 14 for a 150-residue segment exhibiting no gaps, thus linking these two families, and GudT of family 14 exhibits 22% identity and 12 SD to Bmrl of family 3 for the full lengths of the two proteins (eight gaps in the complete binary alignment). Bmrl is an established member of the MFS (60). Thus, families 8 and 14 are members of the MFS as determined by these comparisons. Similarly, the OFA (family 11) member YhjX exhibits 18% identity and 11 SD with five gaps for the full binary alignment with respect to Ykwl of family 13. Family 13 member Motl exhibits 10 SD (17% identity; 5 gaps for the full-length binary alignment) with respect to NanT of family 12, and NanT exhibits 10 SD (25% identity with 11 gaps in the complete binary alignment) with respect to CitA of family 6, a protein shown previously to be a member of the MFS (51). Thus, on the basis of these comparisons and the superfamily principle (18, 71), families 11, 13, and 12 are within the MFS. Using similar logic, the results summarized in Table 2 establish that all 17 families under consideration (with the improbable exception of family 7) are homologous.

Short regions of the binary alignments upon which the comparison scores recorded in Table 2 were based are shown in Fig. 1. These alignments exhibit between 17 and 25% identity with greater than 50% similarity in each case. Most of the regions shown are derived from the N-terminal halves of these proteins. These regions are generally the best-conserved portions of the MFS proteins, as pointed out previously for families 1 to 7 (51, 71).

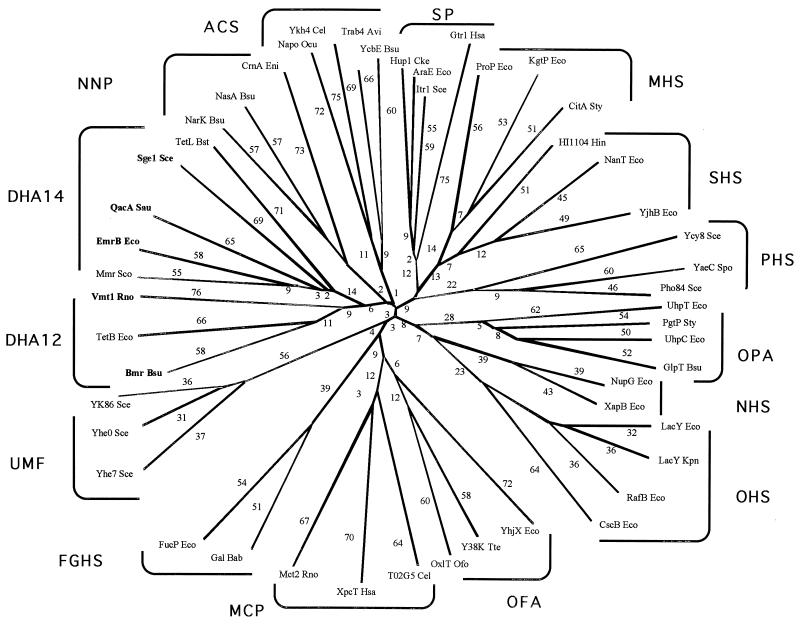

PHYLOGENETIC TREE FOR THE MFS

A phylogenetic tree for the MFS, which includes representative proteins from most of the families, is shown in Fig. 2. Several features are worthy of note. First, most of the families branch from points near the center of the tree. Second, the DHA14 and DHA12 families (families 2 and 3, respectively) branch off from each other after the initial divergence from the center of the tree, suggesting that they are more closely related to each other than to other MFS families. This is in agreement with their similar specificities. Third, the UMF family (family 16) does not branch from a point near the branch for the two DHA families (families 2 and 3), and thus there is no phylogenetic evidence for the suggestion that they transport drugs, even though the proteins of the UMF and DHA14 families both have 14 putative TMSs (26). Fourth, the MCP and OFA families (families 13 and 11, respectively) branch from each other at a point that is somewhat distant from the center of the tree. A late branching point, suggestive of late divergence, is consistent with the fact that both families transport carboxylates. Fifth, the MHS and SHS families (families 6 and 12, respectively) branch from each other relatively far from the center of the tree, suggesting that they are close familial relatives, having diverged from each other late in the evolutionary process. Most, and perhaps all, of the members of these two families transport anionic compounds. The PHS and SP families (families 9 and 1, respectively) also stem from the primary branch from which the MHS and SHS families stem. However, these families branch off close to the center of the tree. Consequently, close phylogenetic relationships for these families are not suggested. Finally, the OPA, NHS, and OHS families (families 4, 10, and 5, respectively) are found branching from the same trunk. All of the proteins of the NHS and OHS families, and some of the members of the OPA family, transport glycosides.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree for the MFS including representative members of most of the currently recognized constituent families. All of the families listed in Table 1 are included except the AAHS family (family 15) and the putative POT family (putative family 18). The TREE program of Feng and Doolittle (22) was used to derive the tree.

FAMILY 1: SUGAR PORTER (SP) FAMILY

The SP family was described many years ago, and its description has been repeatedly updated (7, 7a, 28, 30, 35, 36, 46, 58). The present SP family consists of 133 sequenced members derived from bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. The family includes members that are very diverse in sequence and function. As revealed by the information in Table 3, these proteins function under normal physiological conditions either by uniport or by H+ symport. However, many of these and other MFS permeases can catalyze solute:solute antiport when substrates are present on both sides of the membrane (42). The symporters all function in energized cells with inwardly directed polarity. Substrates of SP family members include galactose, arabinose, xylose, and glucose in bacteria; galactose, quinate, myoinositol, lactose, maltose, and α-glucosides in yeasts and fungi; hexoses in trypanosomes and plants; and sugars as well as organic cations and neurotransmitters in animals. Most but by no means all members of the SP family are therefore specific for sugars.

Figure 3A presents a portion of the multiple-sequence alignment of 20 representative members of the SP family. The proteins included are from bacteria, yeasts, fungi, trypanosomes, plants, and animals. The 47-residue segment shown exhibits no gaps in the multiple alignment, and there are two fully conserved residues. Almost half of the residue positions within this segment exhibit a predominant residue that appears in the consensus sequence. This fact reflects a high degree of conservation. At least 50% of the proteins included in the alignment exhibit the same residue at each of these positions, by definition. While the fully conserved glycine (G) is likely to be of structural importance, the fully conserved glutamate (E) may play a catalytic role. Several of the well-conserved residues (e.g., R’s at alignment positions 2 and 29 and G’s at alignment positions 6 and 10) are conserved in all but one or two of the proteins depicted. The high degree of conservation of these residues clearly suggests that they play important structural or functional roles.

The phylogenetic tree for the SP family members whose sequences are represented in Fig. 3A is shown in Fig. 3B. On the left-hand side of the tree are all of the sugar porters as well as the quinate:H+ symporter (Qa-Y Ncr). Uniporters and proton symporters are often closely related (e.g., XylE Eco and Glf Zmo). More divergent members of the sugar porter cluster are Tht2A Tbr, Ma6T Sce, and Lac12 Kla of protists and yeasts. It is noteworthy that the bacterial, plant, and animal proteins cluster loosely together but most of the yeast and fungal proteins cluster separately.

Two yeast proteins and one protozoan protein branch from points near the base of the tree. However, the most distant members (right-hand side of the tree) include the synaptic vesicle transporter Sv2 Rno and the organic cation transporter Oct-1 Rno, both from the rat. The great phylogenetic distances observed between these proteins and the sugar porters correlate roughly with the divergent substrate specificity of these transporters relative to other members of the SP family.

FAMILY 2: DRUG:H+ ANTIPORTER (14-SPANNER) (DHA14) DRUG EFFLUX FAMILY

The DHA14 drug efflux family has been described recently (60). Thirty members of the family were identified in that study. All functionally characterized members of the DHA14 family have been found to catalyze drug efflux. Of these functionally characterized permeases, 7 are multidrug resistance pumps from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria as well as yeasts, 12 are putative drug-specific pumps from gram-positive bacteria, and 11 are hypothetical or uncharacterized proteins from gram-negative bacteria, yeasts, and fungi. A multiple alignment and a dendogram for the family were presented in that study (60). The multidrug resistance pumps, drug-specific permeases, and uncharacterized proteins did not group together on the DHA14 family dendogram but instead proved to be scattered in an apparently random fashion relative to each other. This fact suggests that drug-specific and multidrug efflux pumps arose repeatedly by narrowing and broadening of their specificities and that the functionally uncharacterized members of the family are also probably involved in drug efflux (74). Because of the extensive treatment of this family by Paulsen et al. (60), these proteins will not be considered further here.

FAMILY 3: DRUG:H+ ANTIPORTER (12-SPANNER) (DHA12) DRUG EFFLUX FAMILY

The DHA12 drug efflux family, also described by Paulsen et al. (60), consists of 46 proteins. Of these, 9 have been shown to be multidrug resistance pumps, 15 are probably drug-specific efflux pumps, and 22 are hypothetical or uncharacterized proteins. Like the DHA14 family, functionally characterized members of the DHA12 family exhibit specificities only for drugs, although the range of drugs transported is remarkable (60). Interestingly, the range of organisms in which DHA12 family members are found is wider than that for the DHA14 family. Thus, the DHA12 MDR pumps are found in animals as well as in yeasts and a variety of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. The proven and putative drug-specific efflux pumps are also found in a wide range of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, yeasts, and animals. Uncharacterized members of this family include an even wider range of organisms, including humans and archaea (reference 60 and unpublished results).

The dendogram for the DHA12 family (60) resembles that for the DHA14 family in that multidrug resistance and drug-specific pumps are interspersed. Thus, in both families, phylogeny does not appear to provide an indication of drug specificity.

FAMILY 4: ORGANOPHOSPHATE:INORGANIC PHOSPHATE ANTIPORTER (OPA) FAMILY

Table 4 lists the members of the OPA family of the MFS. The seven functionally characterized members are derived from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria and function in the transport of either sugar phosphates, glycerol phosphate, or phosphoglycerates and phosphoenolpyruvate. The UhpC proteins are believed to function in the regulation of hexose phosphate transporter synthesis. UhpC presumably serves as a receptor for glucose-6-phosphate the inducer, in controlling transcription of the uhpT operon (38). It is a rare example of an MFS member which does not serve a primary transport function. However, it is not known whether or not it has the capacity to transport its ligand, glucose-6-phosphate.

TABLE 4.

Members of the OPA family (family 4)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GlpT Bsu | Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 444 | P37948 | SP |

| GlpT Eco | Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 452 | P08194 | SP |

| IpgH Sfl | IpgH ORFB gene product (truncated by IS insertion) | B | Shigella flexneri | 333 | U28354 | GB |

| PgtP Sty | Phosphoglycerate transporter | B | Salmonella typhimurium | 406 | P12681 | SP |

| UhpC Eco | Hexose phosphate receptor | B | Escherichia coli | 439 | P09836 | SP |

| UhpC Sty | Hexose phosphate receptor | B | Salmonella typhimurium | 442 | P27669 | SP |

| UhpT Eco | Hexose phosphate transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 463 | P13408 | SP |

| UhpT Sty | Hexose phosphate transporter | B | Salmonella typhimurium | 463 | P27670 | SP |

| F47B8.10 Cel | F47B8.10 (unknown function) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 456 | Z77662 | GB |

| T11G6.2 Cel | T11G6.2 (unknown function) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 495 | Z69384 | GB |

| T11G6.3 Cel | T11G6.3 (unknown function) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 475 | Z69384 | GB |

| T11G6.4 Cel | T11G6.4 (unknown function) | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 304 | Z69384 | GB |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

The predominant mechanism of transport catalyzed by permeases of the OPA family under normal physiological conditions appears to be antiport of an organophosphate ester for inorganic phosphate (49, 50). These permeases may also be capable of catalyzing substrate:H+ symport (19). The best-characterized members of the family are UhpT and GlpT, both of E. coli, for which detailed topological models have been presented (29, 90, 91). The OPA family includes several proteins from the worm Caenorhabditis elegans. Thus, this family includes members derived from eukaryotes as well as prokaryotes.

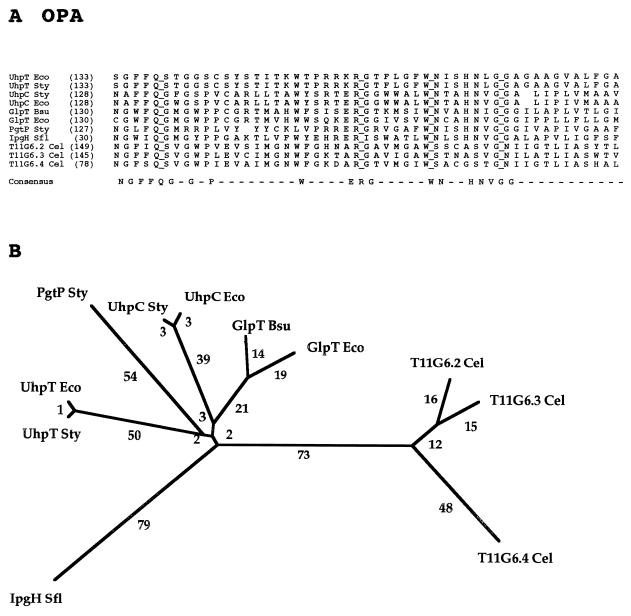

A well-conserved segment of the complete multiple alignment for the OPA family is presented in Fig. 4A. The 52-residue multiple-sequence alignment reveals only three single-residue gaps and shows four fully conserved residues (Q, R, W, and G). Of the 52 alignment positions, 19 are conserved in a majority of the proteins and hence appear in the consensus sequence. Structural (G, P), hydrophobic (F, V), semipolar (W), and strongly polar (N, Q, E, R and H) residues occur in the consensus sequence, with the last group being overrepresented.

FIG. 4.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the OPA family (family 4). The format of presentation for this figure and Fig. 5 to 17 is essentially as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

The phylogenetic tree for the OPA family shows all bacterial proteins clustering together, as do the uncharacterized C. elegans proteins. Surprisingly, the UhpT transport proteins are as distant from the UhpC receptor proteins as these proteins are from the phosphoglycerate transporter (PgtP) or the glycerol phosphate transporters (GlpT). It is therefore of interest that UhpC is apparently specific for glucose-6-phosphate and 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate whereas UhpT recognizes a wide spectrum of sugar phosphates (3, 38). The large separation observed for the bacterial and animal proteins suggests that a primordial gene encoding one of the latter proteins was transferred to eukaryotes by vertical transmission from their prokaryotic progenitors and that gene duplication events in the developing eukaryote gave rise to the three paralogs found in C. elegans. Similarly, the configuration of the tree suggests that the gene duplication and divergence events that gave rise to the functionally dissimilar members of the bacterium-specific subfamilies occurred after the divergence of eukaryotes from prokaryotes.

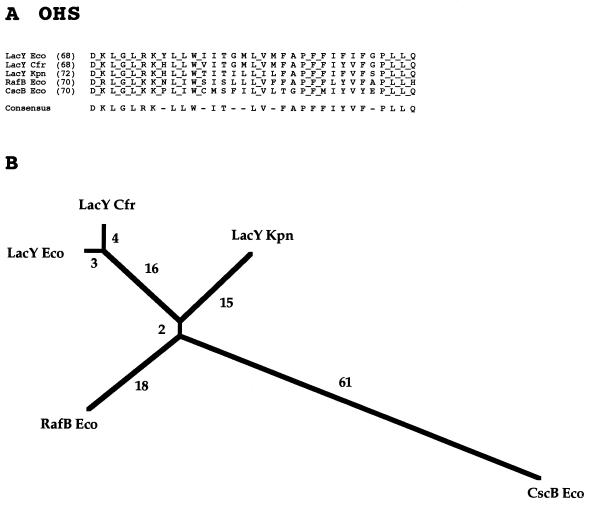

FAMILY 5: OLIGOSACCHARIDE:H+ SYMPORTER (OHS) FAMILY

The current OHS family consists of six proteins, three of which are β-galactoside permeases from closely related bacteria (Table 5). The lactose permease of E. coli is not only the best-characterized member of this family but also probably the most extensively studied permease in the MFS (41, 82). An experimentally verified 12-TMS topological model for LacY has been published (10), and extensive data provide evidence for the nature of the substrate binding sites within the transmembrane region of the permease (8, 12, 23, 27, 43, 57). A detailed mechanistic model that incorporates information obtained using many different experimental approaches has recently been proposed (40).

TABLE 5.

Members of the OHS family (family 5)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CscB Eco | Sucrose transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 415 | P30000 | SP |

| LacY Eco | Lactose-proton symporter | B | Escherichia coli | 417 | P02920 | SP |

| LacY Cfr | Lactose-proton symporter | B | Citrobacter freundii | 416 | P47234 | SP |

| LacY Kpn | Lactose-proton symporter | B | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 416 | P18817 | SP |

| MelY Ecl | Melibiose transporter | B | Enterobacter cloacae | 425 | AB000622 | GB |

| RafB Eco | Raffinose transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 425 | P16552 | SP |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

The other members of the OHS are specific for (i) the trisaccharide, raffinose; (ii) the α,β-nonreducing glucoside-fructoside, sucrose; and (iii) the α-galactoside, melibiose. All of these putative proton symporters are from gram-negative bacteria. The sequence of the melibiose permease of Enterobacter cloacae was deposited in the database after the completion of our phylogenetic analysis of the OHS family and is therefore not represented in Fig. 5. However, this protein proved to resemble RafB Eco (75% identity) more closely than it resembles one of the lactose permeases (50% identity) or the sucrose permease (<40% identity).

FIG. 5.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the OHS family (family 5).

Figure 5A presents an alignment of a well-conserved 33-residue portion of the OHS family proteins. Over one-third of the residues shown in this gap-free alignment are fully conserved, and a large majority of the residues appear in the consensus sequence.

The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5B) reveals that the raffinose permease clusters tightly with the lactose permeases, but that the sucrose permease is much more distant. Raffinose is a trisaccharide which incorporates the structural elements of sucrose, and melibiose in a single molecule. The degree to which these different permeases overlap in specificity is not known, but the broad specificity of the lactose permease of E. coli is noteworthy (56, 82).

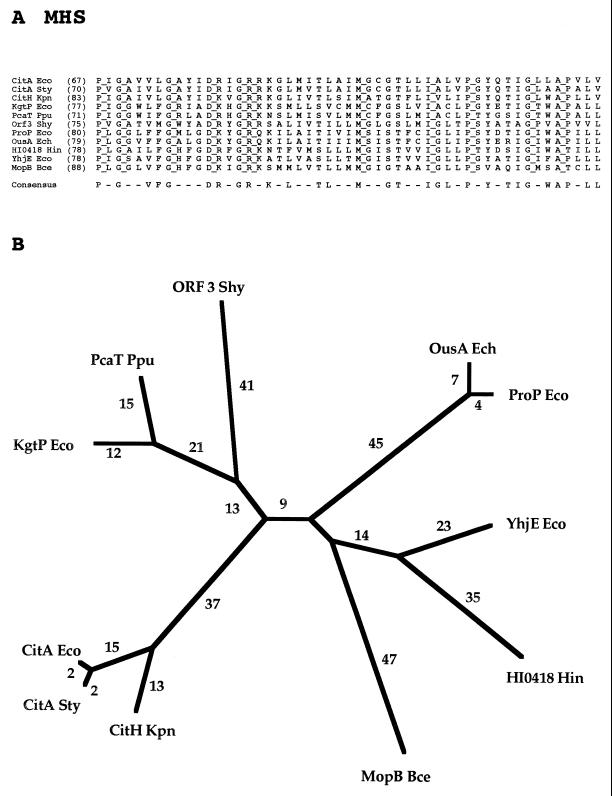

FAMILY 6: METABOLITE:H+ SYMPORTER (MHS) FAMILY

The MHS family includes 16 currently sequenced members of widely differing specificities (Table 6). Those of known transport function recognize (i) citrate, (ii) α-ketoglutarate, (iii) proline and betaine, (iv) 4-methyl-O-phthalate, and (v) dicarboxylates. The α-ketoglutarate:H+ symport permease of E. coli (KgtP) is probably the best-characterized member of this family (75). An experimentally documented 12-TMS topological model has been proposed for this permease (76).

TABLE 6.

Members of the MHS family (family 6)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Data- basea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CitA Eco | Citrate transporter (plasmid) | B | Escherichia coli | 431 | P07860 | SP |

| CitA Sty | Citrate transporter | B | Salmonella typhimurium | 434 | P24115 | SP |

| CitH Kpn | Citrate transporter | B | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 444 | P16482 | SP |

| f427 Eco | Putative metabolite transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 427 | D90798 | GB |

| HI0281 Hin | Putative metabolite transporter | B | Haemophilus influenzae | 438 | P44610 | SP |

| HI0418 Hin | Putative metabolite transporter | B | Haemophilus influenzae | 447 | P44699 | SP |

| I364 Mtu | MTCI364.12 (putative metabolite transporter) | B | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 425 | Z93777 | GB |

| KgtP Eco | α-Ketoglutarate transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 432 | P17448 | SP |

| MopB Bce | 4-Methyl-O-phthalate transporter | B | Burkholderia cepacia | 449 | U29532 | GB |

| o438 Eco | Putative metabolite transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 438 | D90837 | GB |

| Orf3 Shy | Involved in bialophos biosynthesis | B | Streptomyces hygroscopicus | 447 | E47031 | PIR |

| OusA Ech | Osmoprotectant uptake system | B | Erwinia chrysanthemi | 498 | X82267 | GB |

| PcaT Ppu | Dicarboxylic acid transport | B | Pseudomonas putida | 429 | U48776 | GB |

| ProP Eco | Proline/betaine transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 500 | P30848 | SP |

| YhjE Eco | Putative metabolite transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 440 | P37643 | SP |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

Metabolites transported by members of the MHS family have little in common, except that they all possess at least one carboxyl group. Several protein members of the MHS family are specific for Krebs cycle intermediates. All are from bacteria, and all characterized members of the MHS family function by proton symport.

A 51-residue segment of the multiple-sequence alignment of the MHS family, including all functionally characterized members, is shown in Fig. 6A. There are no gaps in the aligned sequences, and 11 residues are fully conserved. The majority of the fully conserved residues are probably of structural significance. These residues include four G’s, two P’s and an A. Two fully conserved residues (M and I) are hydrophobic, and two (D and R) are hydrophilic charged residues. Over half of the positions appear in the consensus sequence, illustrating the high degree of conservation observed for the members of this family.

FIG. 6.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the MHS family (family 6).

The phylogenetic tree for the MHS family reveals clustering according to substrate specificity. Thus, the α-ketoglutarate permease of E. coli and the dicarboxylate permease of Pseudomonas putida cluster together, the osmoprotectant (proline/betaine) permeases of E. coli and Erwinia chrysanthemi cluster tightly together and are undoubtedly orthologs, and all three citrate permeases cluster tightly together. These three proteins are also undoubtedly orthologs. The MopB protein of Burkholderia cepacia, specific for 4-methyl-O-phthalate, is on a branch by itself. Orf3 Shy clusters loosely with dicarboxylate permeases and therefore may exhibit specificity for such a compound. The phylogenetic tree does not provide clues to the functions of the remaining two unidentified proteins. However, these two proteins (YhjE Eco and HI0418 Hin) appear to be located at a phylogenetic distance from each other consistent with their being orthologs. Several MHS homologs of unknown function listed in Table 6 are not represented in Fig. 6 because the sequences were deposited in the databases after completion of the phylogenetic studies reported.

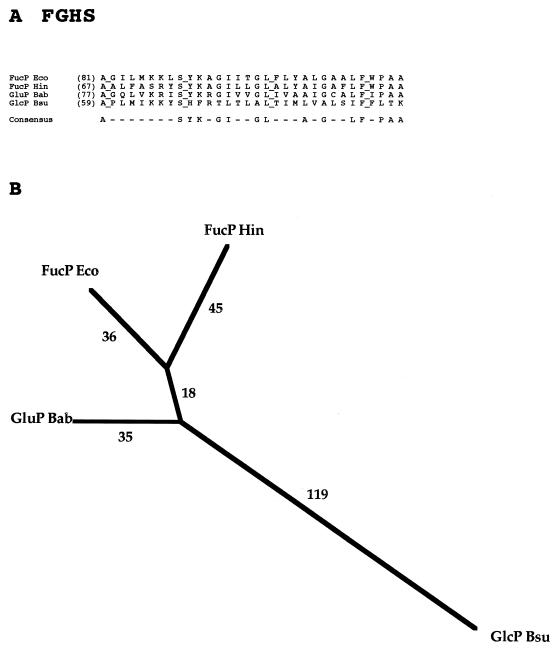

FAMILY 7: FUCOSE-GALACTOSE-GLUCOSE:H+ SYMPORTER (FGHS) FAMILY

The first sequenced member of the FGHS family to be characterized was the FucP fucose permease of E. coli (31), and a 12-TMS topological model for this permease has been presented (32). Subsequently, a galactose/glucose permease of Brucella abortus (20) and a glucose/mannose permease of Bacillus subtilis (61) were characterized and shown to be members of the FGHS family (Table 7). The Bacillus protein, like the E. coli FucP protein, is believed to be a sugar:proton symporter (61). Only four proteins are currently in the FGHS family.

TABLE 7.

Members of the FGHS family (family 7)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FucP Eco | l-Fucose permease | B | Escherichia coli | 438 | P11551 | SP |

| FucP Hin | Putative l-fucose permease | B | Haemophilus influenzae | 428 | P44776 | SP |

| GluP Bab | Galactose/glucose transporter | B | Brucella abortus | 412 | U43785 | GB |

| GlcP Bsu | Glucose/mannose:H+ symporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 404 | AF002191 | GB |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

In spite of the small size of the FGHS family, its members, all of which are derived from bacteria, exhibit a surprising degree of sequence diversion. Figure 7A shows the best-conserved portion of the complete multiple-sequence alignment of these sequences. Only 4 positions in the gap-free 32-position alignment shown are fully conserved, and a minority of the residue positions appear in the consensus sequence. The phylogenetic tree reveals that the Haemophilus influenzae protein clusters closely with FucP of E. coli, that the galactose/glucose permease of B. abortus is more distant, and that the hexose permease from B. subtilis is most divergent. These relative distances correlate with substrate specificity to the extent known since fucose is of the galacto configuration.

FIG. 7.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the FGHS family (family 7).

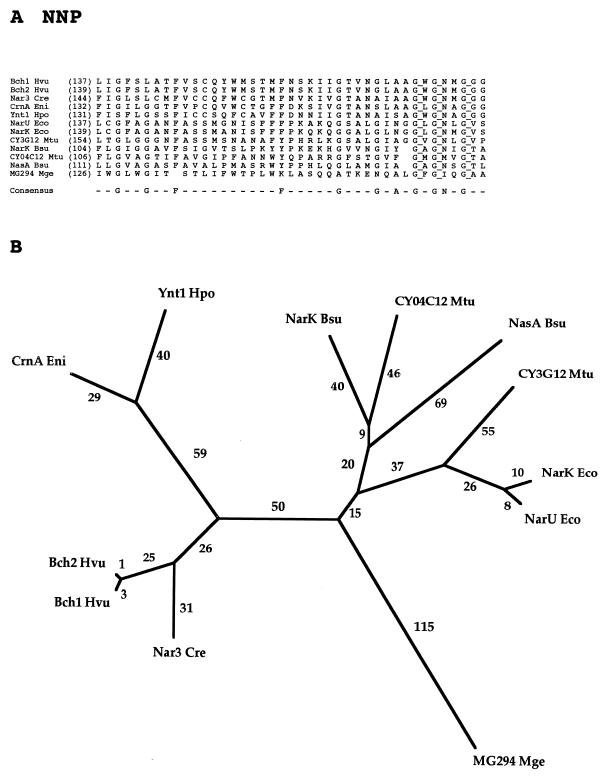

FAMILY 8: NITRATE-NITRITE PORTER (NNP) FAMILY

Thirteen proteins make up the current NNP family (Table 8). These proteins are derived from a variety of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria as well as various eukaryotes including yeasts (Ynt1 Hpo), fungi (CrnA Eni), algae (Nar3 Cre), and higher plants (Bch1 Hvu and Bch2 Hvu). Irrespective of the organism, the nitrate permeases of the NNP family take up their substrate while the nitrite permeases apparently extrude theirs. Well-characterized members of the family are the NarK nitrite extrusion system involved in anaerobic nitrate-dependent respiration in E. coli (68) and the CrnA nitrate uptake permease of Aspergillus nidulans (81).

TABLE 8.

Members of the NNP family (family 8)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CY04C12 Mtu | CY04C12.22c (putative nitrite exporter) | B | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 395 | Z81360 | GB |

| CY3G12 Mtu | MTCY3G12.04 (putative nitrite transporter) | B | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 515 | Z79702 | GB |

| MG294 Mge | Unknown function | B | Mycoplasma genitalium | 474 | E64232 | PIR |

| NarK Bsu | Nitrite exporter 1 | B | Bacillus subtilis | 395 | P46907 | SP |

| NarK Eco | Nitrite exporter 1 | B | Escherichia coli | 463 | P10903 | SP |

| NarK Sty | Putative nitrite exporter (fragment) | B | Salmonella typhimurium | 130 | P37593 | SP |

| NarU Eco | Nitrite exporter 2 | B | Escherichia coli | 462 | P37758 | SP |

| NasA Bsu | Putative nitrate transporter | B | Bacillus subtilis | 421 | P42432 | SP |

| Ynt1 Hpo | Nitrate transporter | Y | Hansenula polymorpha | 508 | Z69783 | GB |

| CrnA Eni | Nitrate transporter | F | Emericella nidulans | 507 | P22152 | SP |

| Bch1 Hvu | Putative nitrate transporter | Pl | Hordeum vulgare | 507 | U34198 | GB |

| Bch2 Hvu | Putative nitrate transporter | Pl | Hordeum vulgare | 509 | U34290 | GB |

| Nar3 Cre | Nitrate transporter | Pl | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | 547 | S40142 | PIR |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

A portion of the NNP family protein multiple alignment is shown in Fig. 8A. Although this region is the best-conserved region in the complete multiple-sequence alignment, only three residues, all G’s, are fully conserved. There are few gaps, and several residues are largely conserved (e.g., three additional G’s, an F, and an N are conserved in all but one, two, or three of the proteins, respectively).

FIG. 8.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the NNP family (family 8).

The phylogenetic tree for the NNP family (Fig. 8B) reveals that all of the eukaryotic proteins cluster together (on the left) as do the prokaryotic proteins (on the right). Further, within the eukaryotic cluster, the fungal proteins comprise one cluster while the plant proteins comprise another. Within the prokaryotic cluster, the two (putative) nitrite extrusion systems of E. coli (NarK and NarU) cluster tightly together. These paralogs probably arose by a recent gene duplication event. All other prokaryotic full-length proteins represented are from gram-positive bacteria. The NasA and NarK proteins of B. subtilis cluster loosely together, even though they are believed to catalyze nitrate uptake and nitrite efflux, respectively. The shorter phylogenetic distance of the M. tuberculosis protein (CY04C12) from NarK Bsu suggests that these two proteins may have the same or similar functions. Further, the other M. tuberculosis protein, CY3G12, resembles the two E. coli permeases, NarK and NarU (Fig. 8B). By contrast, the MG294 protein of M. genitalium is distant from all other members of the NNP family. Proteins from the mycoplasmas often exhibit greater distances from other gram-positive bacterial homologs than do other homologs from the latter bacteria (unpublished observations). The tree thus does not provide a clue to the function of this protein.

FAMILY 9: PHOSPHATE:H+ SYMPORTER (PHS) FAMILY

The current PHS family is unusual in that it includes members from yeasts, fungi and plants but none from bacteria, animals, and other eukaryotes (Table 9). As a family within the MFS, it is presumed to be of ancient origin, and therefore one would expect members of the family to be found in bacteria (see Conclusions and Perspectives, below). Two well-characterized members of the PHS family are the Pho84 inorganic phosphate transporter of S. cerevisiae (9) and the GvPT phosphate transporter of Glomus versiforme (33).

TABLE 9.

Members of the PHS family (family 9)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pho84 Sce | Inorganic phosphate transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 587 | P25297 | SP |

| YaeC Spo | Putative inorganic phosphate transporter | Y | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 559 | Q09852 | SP |

| YCR98c Sce | Probable metabolite transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 518 | P25346 | SP |

| GvPT Gve | Phosphate transporter | F | Glomus versiforme | 521 | U38650 | GB |

| Pho-5+ Ncr | High-affinity phosphate transporter | F | Neurospora crassa | 569 | L36127 | GB |

| AtPT1 Ath | Phosphate transporter | Pl | Arabidopsis thaliana | 524 | U62330 | GB |

| AtPT2 Ath | Phosphate transporter | Pl | Arabidopsis thaliana | 534 | U62331 | GB |

| PT1 Ath | Putative phosphate transporter | Pl | Arabidopsis thaliana | 524 | Y07681 | GB |

| PT2 Ath | Putative phosphate transporter | Pl | Arabidopsis thaliana | 524 | Y07682 | GB |

| PT1 Stu | Inorganic phosphate transporter 1 | Pl | Solanum tuberosum | 540 | X98890 | GB |

| PT2 Stu | Inorganic phosphate transporter 2 | Pl | Solanum tuberosum | 527 | X98891 | GB |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

The 11 members of the PHS family are fairly uniform in size (518 to 587 residues) and exhibit a striking degree of sequence similarity (Fig. 9A). Only eight proteins are included in Fig. 9 because of the near identity of the remaining three sequences to at least one protein that was included. Thus, in the 39-residue segment of the multiple-sequence alignment presented for the eight divergent proteins, 11 positions exhibit full conservation. Four of these residues are glycines, one is a proline, and one is alanine, all of which probably play structural roles. The remaining fully conserved residues (N, E, R, S, and K) are polar and therefore may function in substrate or proton binding or in catalysis of transport.

FIG. 9.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the PHS family (family 9).

The phylogenetic tree for eight members of the PHS family is shown in Fig. 9B. Three of the four plant proteins cluster tightly together, and the short branch lengths separating them indicate that these proteins differ only slightly in sequence. This fact is also revealed by the partial multiple-sequence alignment shown in Fig. 9A. The yeast and fungal proteins cluster loosely together with the fourth plant protein. The occurrence of distant homologs in both the plant and fungal kingdoms suggests that both kingdoms possess isoforms that diverged from each other before plants diverged from fungi.

FAMILY 10: NUCLEOSIDE:H+ SYMPORTER (NHS) FAMILY

The NHS family currently has only two sequenced members, and both proteins are from E. coli (Table 10). One is a general nucleoside:proton symporter, NupG, and the other is a xanthosine permease. NupG has been examined structurally and is the better characterized of the two proteins (85).

TABLE 10.

Members of the NHS family (family 10)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NupG Eco | Nucleoside transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 418 | P09452 | SP |

| XapB Eco | Xanthosine transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 418 | P45562 | SP |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

As shown in Fig. 10, these two proteins are very similar, exhibiting close to 50% identity in the region shown. They evidently arose by a gene duplication event that occurred relatively recently in evolutionary time.

FIG. 10.

Partial alignment of the sequences of the two currently sequenced proteins of the NHS family (family 10).

FAMILY 11: OXALATE:FORMATE ANTIPORTER (OFA) FAMILY

Five sequenced proteins comprise the OFA family, but only one of these proteins has been functionally characterized (Table 11). This protein, the oxalate:formate antiporter from Oxalobacter formigenes, provides the basis for naming the OFA family (1, 4). The protein has been purified, reconstituted in an artificial membrane system, and studied structurally (24, 69). As is apparent from Table 11, members of the OFA family are widely distributed in nature, being present in the bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic kingdoms.

TABLE 11.

Members of the OFA family (family 11)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OxlT Ofo | Oxalate:formate antiporter | B | Oxalobacter formigenes | 418 | U40075 | GB |

| YhjX Eco | Hypothetical 43-kDa protein | B | Escherichia coli | 402 | P37662 | SP |

| c01003 Sso | Unknown | Ar | Sulfolobus solfataricus | 430 | Y08256 | GB |

| Y38K Tte | Hypothetical 38-kDa protein | Ar | Thermoproteus tenax | 373 | P05715 | SP |

| F10G7 Cel | tRNA-Leu in exon 5 | An | Caenorhabditis elegans | 470 | U40029 | GB |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

One would expect that a family that derives its members from all three kingdoms of life would exhibit little sequence similarity. However, as shown in Fig. 11A, 6 residues in the 40-residue segment shown are fully conserved and a majority of residues are present in the consensus sequence. The phylogenetic tree reveals that all five members of the OFA family are nearly equally distantly related to each other. This may be due in part to the fact that most of the organisms from which these proteins are derived are distantly related. However, one cannot draw conclusions about whether these proteins are orthologs of the same function. The answer to this dilemma will require direct experimentation.

FIG. 11.

Partial multiple-sequence alignment (A) and phylogenetic tree (B) for the OFA family (family 11).

FAMILY 12: SIALATE:H+ SYMPORTER (SHS) FAMILY

Only three currently sequenced proteins comprise the SHS family, and only one of these, the NanT sialic acid permease of E. coli, is functionally characterized (Table 12) (52). E. coli possesses two SHS family paralogs, and Haemophilus influenzae possesses one homolog. Sequence comparisons (Fig. 12) and phylogenetic analyses (data not shown) reveal that the two E. coli paralogs are more closely related to each other than either of these proteins is related to the protein from Haemophilus influenzae, even though H. influenzae is closely related to E. coli. The function of this last protein can therefore not be surmised.

TABLE 12.

Members of the SHS family (family 12)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NanT Eco | Sialic acid transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 496 | P41036 | SP |

| NanT Hin | Putative sialic acid transporter | B | Haemophilus influenzae | 407 | C64167 | PIR |

| YjhB Eco | Putative sialic acid transporter | B | Escherichia coli | 425 | P39352 | SP |

For abbreviations, see Table 3 footnotes.

FIG. 12.

Partial alignment of the sequences of the three currently sequenced proteins of the SHS family (family 12).

FAMILY 13: MONOCARBOXYLATE PORTER (MCP) FAMILY

Thirteen proteins comprise the MCP family, and all are from eukaryotes (Table 13). Most of these proteins are derived from various animal sources including three from C. elegans. However, S. cerevisiae possesses four paralogs. Only mammalian members of the MCP family have been functionally characterized. These permeases appear to be energized by proton symport (80). Monocarboxylates transported by these permeases include lactate, pyruvate, and mevalonate (25). Topological studies leading to a 12-TMS model have been reported (65).

TABLE 13.

Members of the MCP family (family 13)

| Abbreviation | Description | Phyluma | Organism | Size (no. of residues) | Accession no. | Databasea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ykl221w Sce | Putative monocarboxylate transporter | Y | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 473 | P36032 | SP |