Abstract

Structural determinants of health drive inequities in the acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the use of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among cisgender women in the United States. However, current PrEP clinical guidance and implementation paradigms largely focus on individual behaviors and characteristics, resulting in missed opportunities to improve PrEP access, and the implicit transferring of prevention work from health systems to individuals. In this viewpoint article, we outline ways to apply a structural lens to clinical guidance and PrEP implementation for women and propose areas for future work.

Keywords: PrEP, women, HIV, structural determinants, equity

To address the structural drivers of human immunodeficiency virus acquisition in cisgender women in the United States, a structural lens must be applied to preexposure prophylaxis clinical guidance and implementation.

Systemic racism is a root cause of stark racial/ethnic inequities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) diagnoses among cisgender women in the United States, and intersects with sexism, geographic inequities, poverty, and other social and structural determinants of health [1]. Camara Jones, a social epidemiologist, defines racism as “a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks”—what we call “race”—that advantages certain groups, while disadvantaging others [2]. Structural racism refers to codification of racism into laws, policies, institutions, and social practices, and its manifestations include mass incarceration, residential segregation, and wealth inequities, key drivers of health inequities [3, 4].

In this context, black women in the United States face a 17-fold higher lifetime risk of acquiring HIV than white women. Cisgender women account for nearly 20% of new HIV diagnoses [1, 5, 6]; while the use of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention has risen dramatically since approval in 2012, women’s use remains low. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that >176 000 women may benefit from PrEP, but only approximately 7% of these women received prescriptions in 2018 [5]. PrEP-to-need ratios, indicators of PrEP use relative to HIV diagnoses, suggest that women have some of the greatest unmet need for PrEP [7]. For black women in the South, that unmet need is likely greater. In response to racial inequities in PrEP use among women, the HIV National Strategic Plan identifies black women as a priority population for PrEP interventions [8].

Current PrEP implementation paradigms largely focus on assessing individual behaviors rather than structural determinants of health. This focus is most evident in PrEP cascades, public health tools to identify implementation gaps and increase PrEP use. Many cascades begin with HIV risk assessments to determine eligibility, followed by offering PrEP services, and finally PrEP use [9]. While recent models incorporate how structural forces constrain steps in the cascade, in general, cascades focus on the individual—individual risk factors, motivations, and behaviors [10].

This approach minimizes the roles of racism and other structural forces in driving HIV risk and diagnoses, removes responsibility from healthcare providers and systems, and burdens patients with the responsibility of prevention, ultimately blaming them for HIV acquisition. Consequently, when PrEP cascades are applied to women, they fall short: a decade after PrEP’s approval, little has changed regarding women’s PrEP use. To address existing gaps in PrEP implementation and persistent racial/ethnic inequities in women’s PrEP use, we contextualize limitations of current clinical guidance, outline ways to apply a structural lens to the clinical guidance and PrEP implementation for women, and propose areas for future work.

CLINICAL GUIDANCE CHALLENGES

While the CDC offers PrEP clinical guidance, women’s health practitioners and researchers struggle with the guidance’s practicality [11]. Draft 2021 CDC guidance addresses some of these concerns [12]. For example, the new guidance acknowledges how clinical risk assessments are limited by reliance on patient disclosure of risk and cites numerous studies documenting patients’ discomfort disclosing sexual practices. Generally described as medical distrust, this stems directly from a long and ongoing history of medical racism, discrimination, and mistreatment focused on black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) [13, 14].

Intimate partner violence (IPV), which BIPOC women may experience more frequently or severely, is also associated with HIV acquisition [15, 16]. Barriers to IPV disclosure are widely documented, bringing into question the usefulness of IPV screening, and screening for any stigmatized condition, [17]. Barriers to disclosure about sexual practices, IPV, and other HIV vulnerabilities may be particularly pronounced for groups with the highest HIV incidence, namely, black women and other women of color. The 2021 draft CDC guidance suggests discussing PrEP with all sexually active people, regardless of risk disclosure, and not denying PrEP to those who request it without a specific qualifying behavior [12]. However, outside of those requesting PrEP, counseling about and prescribing of PrEP still rely on sexual history, which, in the context of medical racism and other forms of discrimination, constrains PrEP access.

Finally, CDC guidance suggests using biomedical markers of HIV vulnerability, including recent gonorrhea or syphilis. In the referent study from Florida, gonorrhea and syphilis were associated with increased odds of HIV, but the majority of HIV diagnoses occurred in women with no identifiable risk factors other than heterosexual sex [18]. Later studies showed regional differences in the usefulness of these infectious biomarkers, further limiting their application [19].

APPLYING A STRUCTURAL LENS TO CLINICAL GUIDELINES

Researchers have also critiqued CDC guidelines for inconsistently identifying community-level indicators of HIV risk, such as neighborhood prevalence [11]. Rather than highlighting these structural factors, which are likely powerful drivers of HIV acquisition in cisgender women, the CDC deemphasized “high HIV prevalence area or network” as an HIV risk indicator from the draft 2021 guidance. Beyond assessing local HIV epidemiology, advocates have proposed structural vulnerability assessments that measure ways in which “multiple overlapping and mutually reinforcing power hierarchies (e.g., socioeconomic, racial, cultural) and institutional and policy-level statuses (e.g., immigration status, labor force participation) constrain (individuals’) ability to access healthcare and pursue healthy lifestyles” [20]. Within the realm of HIV vulnerability, that assessment may include exposure to multiple structural factors including racism, poverty, and mass incarceration.

While including structural assessments in clinical guidance is a first step, how to incorporate them into HIV prevention counseling has yet to be determined. Few public health campaigns about PrEP explicitly address structural determinants of HIV, and few provider trainings address how to discuss racism and other structural determinants with patients [21, 22]. In part, this is because little is known about if and how patients want to discuss structural determinants during healthcare encounters. In preliminary findings from a study in Florida, while some women found discussions with providers about structural risk factors for HIV—specifically racism—empowering, others found them triggering [23]. More work is needed to understand patients’ experiences of structural risk assessments, and how assessments can be constructively incorporated into clinical care.

Little is also known about providers’ motivations to address structural determinants in clinical visits. In one study, focus groups with family planning providers suggested clinicians shied away from PrEP discussions because they were wary of conversations about structural influences on health [24]. Despite pronounced HIV inequities driven by structural determinants, by not including structural assessments in PrEP clinical guidelines, clinicians are permitted to sidestep conversations about structural determinants and HIV risk entirely. Considering the sociopolitical context of the United States, where many white Americans are ill equipped to discuss racism and its effects, where a majority of physicians and medical school faculty identify as white, and medical schools are only beginning to name racism as a root cause of inequitable health outcomes, clinicians’ avoidance of racism as a driver of HIV risk is unsurprising. Diversification of the healthcare workforce, with increased racial/ethnic concordance between patients and providers, may be one way to facilitate conversations about structural determinants addressing barriers to PrEP use [14, 25]. More broadly, to end the HIV epidemic, clinicians must be trained to interrogate the influence of racism in their personal and professional lives and equipped to engage in respectful and meaningful conversations with the communities they serve [26]. In other words, clinicians must gain structural competency [27].

APPLYING A STRUCTURAL LENS TO PrEP IMPLEMENTATION

A structural lens may be applied not only to PrEP clinical guidance but also to implementation and evaluation. There is growing consensus within women’s sexual and reproductive health fields that failure to recognize and dismantle the systems of oppression that create and perpetuate inequities will create further harm [28]. For HIV prevention services, this includes understanding the long history of reproductive coercion and regulation of women’s bodies, particularly among BIPOC; the history of PrEP development, research, and promotion that excluded women, including most recently trials of emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide; and local history relevant to individual communities and patients. Both public health tools, such as PrEP cascades, and clinical guidance lack attention to these histories; in turn, HIV prevention efforts for women continue to fall short.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR PrEP PROVISION

Move From Risk-Based Screening to Universal PrEP Education

Risk-based screening, including risk-based HIV testing [29], misses individuals who do not disclose stigmatized activities or who may be unable to identify clear risk factors but suspect they are at risk. Programs that offer resources only to those who “screen in” likely miss eligible people. To combat underreporting of IPV, universal education has been promoted, ensuring that everyone receive consistent information and resources [30]. A similar approach may be applied to HIV prevention by offering universal PrEP education before screening. This approach is supported by the 2021 draft CDC PrEP clinical guidance [12].

An approach that provides universal PrEP education may begin to flatten power structures, allowing patients to access information without mandatory screening or disclosure. Public health campaigns can be developed with community input and use a strengths-based approach to highlight PrEP as a health-promoting strategy without focusing on individual behaviors or “high risk” populations; an example is New York City’s women-focused “Living Sure” campaign [11]. Public health messaging may be coupled with universal education in clinics (eg, family planning clinics and adolescent health clinics) and community settings (eg, school-based sex education) [31]. Universal education may destigmatize PrEP use and increase awareness of PrEP to facilitate individuals’ requesting it.

While the goal of universal education is to make information more accessible and equitable, this approach exists within a structural context, including historical and current medical mistreatment fostering medical distrust. Universal PrEP education may therefore be received in variable ways, and without careful attention and listening to the communities receiving that information, may cause unintended harm. To avoid this, and to advance equity (rather than equality), a shift to universal education must begin by working with and listening to women who have been historically marginalized [1]. This includes evaluation, iterative improvement, and tailoring of universal education messaging across diverse communities and locations, as well as openness to community-based communication strategies.

Challenges in Patient-Provider Communication

Person-centered counseling around HIV prevention is crucial when engaging individuals with significant distrust of the healthcare system due to historical and present-day systemic oppression and mistreatment. Black women face profound inequities in women’s health, in part due to racism and sexism in women’s healthcare encounters [32]. Multiple studies report that black women feel stereotyped and more uncomfortable than white women in sexual and reproductive health counseling [33]. Moreover, black women have reported distrust of the healthcare system as a key barrier to PrEP uptake [34]. Finally, a recent study demonstrated that providers scoring higher on a racism scale were less likely to prescribe PrEP to black women [35]. Trust building is an evidence-based practice in contraceptive counseling to acknowledge distrust and experiences of mistreatment and foster shared decision making and patient-centered care [36, 37]. This principle is appropriately extrapolated to HIV prevention counseling, given similar clinical and structural contexts [38].

Key to trust building and shared decision making about HIV prevention options is the discussion of HIV vulnerabilities. Those vulnerabilities may include factors at the individual, partner, and community levels, ranging from sexual practices to community incarceration rates. To advance PrEP implementation, we must explore how to share this information, particularly in healthcare visits that cannot be separated from a long history of present-day medical racism and mistreatment. This patient-provider discussion may be contextualized by what has been aptly named “PrEP rumination,” or deliberation about PrEP initiation, described in qualitative interviews with women in New York [39]. One pilot study in Miami demonstrated feasibility and acceptability of motivational interviewing in clinical visits with black women, resulting in increased motivation to use PrEP and decreased medical mistrust [40]. More research is needed to explore these interventions with other populations.

Promoting a Healing Clinical Environment to Advance Sexual and Reproductive Health

Trust building must be embedded into healthcare systems rather than limited to clinical encounters. Healing-centered engagement is an asset-driven, holistic approach to addressing trauma and building trust that recognizes structural causes of trauma, and that trauma may be a collective experience [41]. This approach creates safer clinical environments for patients who have experienced a range of traumas—from interpersonal violence to systemic trauma. Notably, many HIV vulnerabilities cited in socioecological models of women’s HIV risk can be understood as forms of trauma [42]. Therefore, healing-centered engagement models provide a framework within which to address structural contributions to HIV risk and offer HIV prevention strategies.

Adopting Lessons From Coronavirus Disease 2019 to Expand Access

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic created further challenges to engaging women in HIV prevention, and also afforded opportunities to expand prevention services, including telehealth visits, longer PrEP prescriptions, and home testing for HIV and sexually transmitted infection. While best practices continue to evolve, providing new ways to access prevention services, as long as they are offered as one of many options, will meet more people’s needs. At the same time, the pandemic highlighted how certain groups, particularly those most affected by structural drivers of HIV risk, face substantial barriers to using telehealth services, and may fall out of care without in-person options [43, 44]. Rising IPV during the pandemic provided a glaring example of the limitations of telehealth in providing services to those who depend on the privacy of a clinic visit to access resources and preventive care [45].

Person-Centered HIV Preventive Care Outcomes

The contraceptive care field is rethinking end points, moving away from narrow focus on pregnancies prevented, contraceptive initiation, and contraceptive continuation and toward nuanced measures grounded in reproductive autonomy [46]. This work advances person-centered contraceptive care in which program quality is based not on the numbers of contraceptives distributed, pregnancies avoided, or money saved, “but by how many people feel truly respected and cared for when it comes to childbearing and family formation” [47].

These concepts can be adapted to the sexual health and HIV prevention fields. When we rethink PrEP implementation as an opportunity to foster person-centered sexual healthcare, the ultimate end point becomes not solely PrEP initiation, persistence, or retention, but how many people feel respected and cared for and have their clinical needs met, with respect to their sexual health and well-being. In turn, programs and payors may continue to count HIV infections averted, coupled with person-centered measures. While this approach may seem overly idealistic, the National Quality Forum, which payors use for performance measures, identifies person-centeredness as central to high-value care [48]. The contraceptive care field has operationalized these concepts into a patient-reported measure used in clinics to assess person-centered contraceptive care [49]. Given the long history of sexual and reproductive health abuses of BIPOC women, PrEP implementation requires this type of person-centered quality measure to accompany standard measures of PrEP implementation.

Potential for and Limitations of Expanding Biomedical Prevention Options

With additional HIV prevention technologies nearing availability, we have an opportunity to transform HIV prevention implementation for women into one centered on the experiences and priorities of BIPOC women. Without this transformation, the HIV prevention community risks further widening inequities by using inequitable infrastructure developed in early iterations of oral PrEP. Moreover, while implants and injectables may support people who find daily pill adherence challenging, they do not address the effects of underlying structures on HIV vulnerability. Housing insecurity, limited transportation, and other structural determinants may be identified in structural vulnerability assessments of HIV risk, and patients may identify these as focus areas for HIV prevention, rather than biomedical technologies.

As healthcare providers and advocates, we must listen to those assessments from the experts—patients—and strategize how to incorporate structural interventions to promote HIV prevention into biomedically focused HIV prevention toolkits. While it is unlikely that clinicians will or should become experts in these areas, social workers, navigators, community partners, and advocates with relevant expertise must be fully integrated into HIV prevention efforts. Their work may focus on individual-level linkages and supports to change individual exposures to structural determinants, as well as community- and structural-level interventions to change policies driving HIV vulnerabilities. Clinicians play an important role as well, advocating for the disruption of the biomedically focused model, and for the antiracism work and structural change that is necessary to advance health equity.

CONCLUSIONS: REIMAGINING PrEP PROVISION FOR WOMEN

PrEP cascades and current clinical guidance are insufficient to support or monitor PrEP implementation among women. Public health approaches to HIV prevention need to be structurally informed, grounded in historical context, and framed as explicitly antiracist, equity oriented, and person centered.

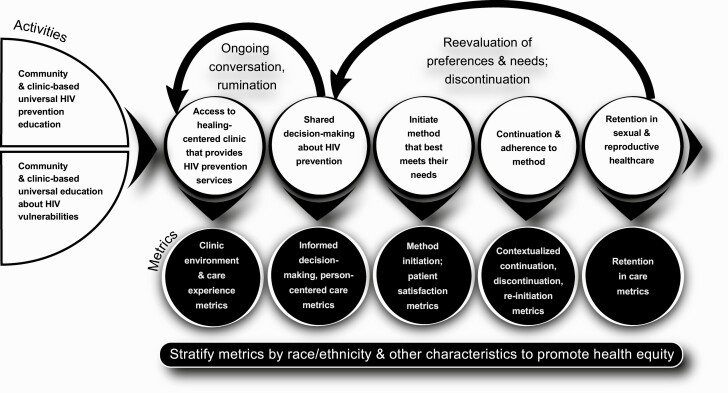

We propose a reimagined PrEP provision paradigm (Figure 1), which begins with universal PrEP education in communities and clinics. With health educators and/or clinicians, individuals would have a person-centered conversation about PrEP in the context of other HIV prevention options, and a healing-centered discussion of HIV vulnerabilities. Clinicians would acknowledge barriers to care and celebrate care engagement, as well as elicit and listen to care priorities, which may or may not include biomedical HIV prevention. If a patient elects for ongoing discussion, she/they would engage in shared decision making about whether PrEP, or another HIV prevention method, is right for them [38]. This clinical encounter would occur in a healing-centered environment with the goal of care being relationship and trust building. Patients may leave and return for ongoing conversations as part of PrEP rumination, start PrEP later, choose another or no HIV prevention method, or refer a friend or family member.

Figure 1.

Reimaging human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention services for women in the United States. In a reimagined paradigm for provision of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), women would receive universal education, from communities and clinics, about vulnerabilities to HIV and HIV prevention strategies including PrEP. Women would then access healing-centered clinics that provide PrEP, where shared decision making would occur around HIV prevention options. Women would initiate methods that best meet their needs, continue methods, or change methods; these processes may or may not be sequential. Women would have easy access to ongoing discussion about HIV prevention methods and, regardless of method continuation, maintain engagement in sexual and reproductive health services.

Evaluation and outcomes of this approach would include assessment of shared information, informed decision making, and patient-reported care experiences, rather than simply a decision to start PrEP. Examples of this type of evaluation exist in the reproductive health literature and may be modified and tested to apply to HIV prevention [49]. Moreover, clinics and clinicians would be evaluated for their promotion of a respectful, person-centered environment [50]. Metrics of persistence would reflect changing HIV vulnerabilities, priorities, and preferences and patient satisfaction with methods. This nuance is particularly important as longer-acting methods become available. As demonstrated in the contraception literature, persistence must be contextualized, to ensure that continuation is not a reflection of provider reluctance to discontinue a method [46]. Finally, the ultimate outcome would shift focus from medication use to retention in sexual and reproductive healthcare. In turn, PrEP would be viewed as an opportunity to rebuild trust in sexual and reproductive health services and advance sexual and reproductive health equity.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The figures were designed by Bryn Ludlow (https://brynludlow.com/#Home).

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the National Institute of Health (NIH).

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIH Women's Reproductive Health Research Grant 5K12HD001262-18 [principal investigator, Amy P. Murtha] to D. S.) and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (support to A. G.; no payments to A. G. or their institution).

Potential conflicts of interest. D. S. reports personal payments for lectures at national conference on family planning from the National Clinical Training Center for Family Planning, a nonprofit that provides education about family planning services, including human immunodeficiency virus prevention and preexposure prophylaxis, and serves on the Center’s National Advisory Board. S. W. works for Gilead Sciences, on the corporate giving team, starting 25 September 2021, and worked as a contractor for Gilead Sciences as a contractor from 1 March to 23 September 2021. A. G. reports support from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, and the NIH; reports consulting for Health Justice (unpaid); reports receiving a stipend for participation on a steering committee from University of Michigan; reports having been supported by their employer, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, to attend relevant professional conferences and/or meetings; and reports serving in an unpaid role as a board member of the New York Abortion Access Fund through June 2019. O. B. reports payment or honoraria from Clinical Mind for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events. R. L. reports no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Dominika Seidman, Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Rachel Logan, Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Shannon Weber, San Francisco, California, USA.

Anisha Gandhi, Racial Equity and Social Justice Initiatives, Bureau of HIV, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York, New York, USA.

Oni Blackstock, Health Justice, New York, New York, USA.

References

- 1. Black AIDS Institute. We the people: a strategy to end HIV. Available at: https://www.blackaids.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Black-AIDS-Institute-We-The-People-Report-2020-Version-1.1.pdf. Accessed 1 June2021.

- 2. Racism and health. Available at: https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity/racism-and-health. Accessed 1 June 2021.

- 3. Doshi RK, Bowleg L, Blackenship KM. Tying structural racism to human immunodeficiency virus viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:e646–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health 2019; 40:105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and women: HIV incidence. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/incidence.html. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- 6. Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 2017; 27:238–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis–to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol 2018; 28:841–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Department of Health and Human Services. HIV National Strategic Plan: a roadmap to end the epidemic 2021–2025. Available at: files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/HIV-National-Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2021.

- 9. Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS 2017; 31:731–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schaefer R, Gregson S, Fearon E, Hensen B, Hallett TB, Hargreaves JR. HIV prevention cascades: a unifying framework to replicate the successes of treatment cascades. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e60–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Willie TC, Kershaw TS, Mayer KH. US guideline criteria for human immunodeficiency virus preexposure prophylaxis: clinical considerations and caveats. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:884–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2021.

- 13. Ojikutu BO, Amutah-Onukagha N, Mahoney TF, et al. HIV-related mistrust (or HIV conspiracy theories) and willingness to use PrEP among black women in the United States. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:2927–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between black and white women: implications for patient-provider communication about PrEP. AIDS Behav 2019; 23:1737–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The link between exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among women in the United States. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/csi/ipv-hiv.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- 16. Intimate partner violence. 2018 National Crime Victims’ Rights Week resource guide: crime and victimization fact sheets. Available at: https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_IPV_508_QC.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2021.

- 17. O’Doherty LJ, Taft A, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, Davidson LL, Feder G. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: abridged Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014; 348:g2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peterman TA, Newman DR, Maddox L, Schmitt K, Shiver S. Risk for HIV following a diagnosis of syphilis, gonorrhoea or chlamydia: 328,456 women in Florida, 2000–2011. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26:113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berzkalns AE, Barbee LA, Dombrowski JC, Golden MR. Low HIV incidence among women following sexually transmitted infection does not support national pre-exposure prophylaxis recommendations. AIDS 2020; 34:1429–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, Quesada J. Structural vulnerability: operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Acad Med 2017; 92:299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bagchi AD. A structural competency curriculum for primary care providers to address the opioid use disorder, HIV, and hepatitis C syndemic. Front Public Health 2020; 8:210. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7289946/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Downey MM, Gómez AM. Structural competency and reproductive health. AMA J Ethics 2018; 20:211–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Logan R, Wulf S, Wilson W, et al. Empowering or racist? Sharing information about HIV-related health inequities and structural risk factors for HIV acquisition with women in the U.S. AIDS 2020; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Razon NA, Rodriguez A, Carlson K, et al. “Far more than just a prescription”: focus groups with U.S. family planning providers and staff about integrating PrEP for HIV prevention into their work. Women’s Health Issues 2021; 31:294–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. King WD, Wong MD, Shapiro MF, et al. Does racial concordance between HIV-positive patients and their physicians affect the time to receipt of protease and targeted HIV screening in the emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 64:315–23.23846569 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Health equity competencies for health care providers. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/ending_the_epidemic/docs/health_equity_providers.pdf. Accessed 25 October 2021.

- 27. Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med 2014; 103:126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perritt J. #WhiteCoatsForBlackLives—addressing physicians’ complicity in criminalizing communities. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1804–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ruffner AH.et al. Randomized comparison of universal and targeted HIV screening in the emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021; 88:165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Todahl J, Nekkanti A, Schnabler S. Universal screening and education: a client-centered protocol for normalizing intimate partner violence conversation in clinical practice. J Couple Relatsh Ther 2020; 19: 322–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seidman D, Weber S, Carlson K, Witt J. Family planning providers’ role in offering PrEP to women. Contraception 2018; 97:467–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eichelberger KY, Doll K, Ekpo GE, Zerden ML. Black lives matter: claiming a space for evidence-based outrage in obstetrics and gynecology. Am J Public Health 2016; 106:1771–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thorburn S, Bogart LM. African American women and family planning services: perceptions of discrimination. Women Health 2005; 42:23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flash CA, Stone VE, Mitty JA, et al. Perspectives on HIV prevention among urban black women: a potential role for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS patient care and STDs 2014; 28:635–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hull SJ, Tessema H, Thuku J, et al. Providers PrEP: identifying primary health care providers’ biases as barriers to provision of equitable PrEP services inhibitors? J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19:1146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hill BS, Patel VV, Haughton LJ, Blackstock OJ. Leveraging social media to explore black women’s perspectives on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2018; 29:107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dehlendorf C, Krajewski C, Borrero S. Contraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2014; 57:659–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, Dehlendorf C, Marcus JL, Krakower DS. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021; 1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park CJ, Taylor TN, Gutierrez NR, Zingman BS, Blackstock OJ. Pathways to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among women prescribed PrEP at an urban sexual health clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2019; 30:321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dale SK. Using motivational interviewing to increase PrEP uptake among black women at risk for HIV: an open pilot trial of MI-PrEP. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2020; 7:913–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ginwrite S. The future of healing: shifting from trauma informed care to healing centered engagement. Medium 2020. Available at: https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c. Accessed 15 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seidman D, Weber S. Integrating preexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus prevention into women’s health care in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ukoha EP, Davis K, Yinger M, et al. Ensuring equitable implementation of telemedicine in perinatal care. Obstet Gynecol 2021; 137:487–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Power L. COVID-19 has had a major impact on PrEP, sexual behaviour and service provision. AIDSmap 2020. Available at: https://www.aidsmap.com/news/jul-2020/covid-19-has-had-major-impact-prep-sexual-behaviour-and-service-provision. Accessed 15 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Evans ML, Lindauer M, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic—intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2302–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dehlendorf C, Reed R, Fox E, Seidman D, Hall C, Steinauer J. Ensuring our research reflects our values: the role of family planning research in advancing reproductive autonomy. Contraception 2018; 98:4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gubrium AC, Mann ES, Borrero S, et al. Realizing reproductive health equity needs more than Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC). Am J Public Health 2016; 106:18–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. The care we need. Available at: https://thecareweneed.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Full-Report-The-Care-We-Need-Update-Aug-2020.pdf. Accessed 25 October 2021.

- 49. Dehlendorf C, Fox E, Silverstein IA, et al. Development of the Person-Centered Contraceptive Counseling scale (PCCC), a short form of the Interpersonal Quality of Family Planning care scale. Contraception 2021; 103:310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vedam S, Stoll K, Rubashkin N, et al. The Mothers on Respect (MOR) index: measuring quality, safety, and human rights in childbirth. SSM Popul Health 2017; 3:201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]