Abstract

Aims

Frailty is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular (CV) events. Limited data exist from the modern era of CV prevention on the relationship between frailty and CV mortality. We hypothesized that frailty is associated with an increased risk of CV mortality.

Methods and results

All US Veterans aged ≥65 years who were regular users of Veteran Affairs care from 2002 to 2017 were included. Frailty was defined using a 31-item previously validated frailty index, ranging from 0 to 1. The primary outcome was CV mortality with secondary analyses examining the relationship between frailty and CV events (myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization). Survival analysis models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, geographic region, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, statin use, and blood pressure medication use. There were 3 068 439 US Veterans included in the analysis. Mean age was 74.1 ± 5.8 years in 2002, 76.0 ± 8.3 years in 2014, 98% male, and 87.5% White. In 2002, the median (interquartile range) frailty score was 0.16 (0.10–0.23). This increased and stabilized to 0.19 (0.10–0.32) for 2006–14. The presence of frailty was associated with an increased risk of CV mortality at every stage of frailty. Frailty was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, but not revascularization.

Conclusion

In this population, both the presence and severity of frailty are tightly correlated with CV death, independent of underlying CV disease. This study is the largest and most contemporary evaluation of the relationship between frailty and CV mortality to date. Further work is needed to understand how this risk can be diminished.

Key Question

Can an electronic frailty index identify adults aged 65 and older who are at risk of CV mortality and major CV events?

Key Finding

Among 3 068 439 US Veterans aged 65 and older, frailty was associated with an increased risk of CV mortality at every level of frailty. Frailty was also associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, but not revascularization.

Take Home Message

Both the presence and severity of frailty are associated with CV mortality and major CV events, independent of underlying CV disease.

Keywords: Frailty, Risk prediction, Risk factors, Epidemiology, Ageing, Mortality

Graphical Abstract

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Frailty and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: are we at a crossroad to include frailty in cardiovascular risk assessment in older adults?’, S. Goya Wannamethee, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab818.

Introduction

Frailty is a state of vulnerability increasingly prevalent in older adults globally.1 , 2 While the pathophysiology of frailty involves nearly every organ system, the effects on cardiovascular health are prominent.3 , 4 Frailty has previously been demonstrated to increase risk of future cardiac events and portend higher risk of morbidity and mortality for patients who have established cardiovascular disease (CVD).5 , 6 However, most prior individual studies were conducted in cohorts of patients recruited in the 1980s to early 2000s with sample sizes ranging from a few hundred to ∼40 000, with some pooled analyses reaching sample sizes of 154 000.7–9 More contemporary evaluations of the interplay of frailty and CVD have looked at specific patient populations (such as those with heart failure or atrial fibrillation) and/or used large existing trials (i.e. PARADIGM-HF, ENGAGE AF-TIMI, etc.) to retrospectively look at clinical events, or as one large recent study did, used national primary care data from the National Health System in England.10–12 Recent data have shown that the burden of frailty in US Veterans is higher than in the general population [with prevalence of frailty in the Veteran Affairs (VA) ranging from 32% in 2002 to 47% in 2012 compared with the 9–34% reported in similar non-VA studies];13however, the association between frailty and cardiovascular outcomes in a modern cohort or in US Veterans has not been explored.

Furthermore, in the era of statin therapy, high potency anti-platelet agents, and modern blood pressure guidelines, the relationship between CVD and frailty has not been explored. Methods to identify frailty in existing databases have been developed and validated, including the cumulative deficit model in VA.13 , 14

We hypothesized that a high frailty score, derived from electronic health record data, can identify US Veterans aged 65 and older who are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. We also hypothesized that frailty is associated with an increased risk of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) events: myocardial infarction (MI)/fatal MI, stroke/fatal stroke, and need for revascularization.

Methods

Study population

Our population includes all US Veterans aged 65 years or older who were regular users of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services between 2002 and 2014, with follow-up through 2017. Regular use was defined as having at least one primary care visit and a recorded blood pressure measurement. The index date was established by the last visit date in the year of cohort entry, and data were queried biennially.

Frailty definition

Frailty was previously defined according to the well-validated Rockwood cumulative deficit model that included 31 items.13 , 14 Briefly, these variables met the criteria of: (i) being related to health status, (ii) increased prevalence with age, (iii) not reaching a prevalence of 100% before age 65, and (iv) covering a range of systems such as cognition, function, mood, and morbidity. Constructing a frailty index (FI) using this method is a validated approach for creating a reproducible, reliable metric for assessing frailty. As to the distribution of the 31 items of our FI, 14/31 components assess medical co-morbidities, 8/31 assess physical function, 3/31 assess sensory loss, 3/31 assess cognition and mood, and 3/31 fall into various other categories (a full breakdown is available in the Supplementary material online). This approach is the same that has been used to calculate frailty across primary care clinics in the UK.15 The national VA administrative data set was linked to Medicare and Medicaid files to ensure complete capture of relevant variables.13 , 16–18 The variables included in our analysis and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes used to define them are listed in Supplementary material online, Table S1.

The FI was calculated by taking the number of variables present per patient and dividing that by the total number of variables assessed. For example, if a patient had 12 of 31 variables, their FI would be 0.39. The degrees of frailty were defined as: not frail (FI < 0.1), pre-frail (FI > 0.1 to ≤0.2), mildly frail (FI > 0.2 to ≤0.3), moderately frail (FI > 0.3 to ≤0.4), and severely frail (FI > 0.4).13 Most studies suggest that an FI > 0.7 is rarely compatible with life.19

Outcomes

The primary outcome was cardiovascular mortality identified in the National Death Index. Secondary outcomes were MI/fatal MI, stroke/fatal stroke, and any revascularization procedure [percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)], and a composite of these cardiovascular events, all identified through claims codes (Supplementary material online, Table S1).

Covariates

In addition to the variables used in the FI, covariates include age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, presence of hyperlipidaemia, use of anti-hypertensives, use of statins, and smoking status.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data (age, sex, race, ethnicity), smoking status, insurance data, and existing health conditions were obtained from VA electronic health records at the time of FI calculation. Medication use was also taken from VA electronic health records at time of FI calculation using dispensed generic drug names and ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes from inpatient and outpatient care. Geographic region was determined using the 21 Veterans Integrated Service Networks. Follow-up began from the date of FI calculation.

For the primary analysis, we used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for cardiovascular mortality, using FI ≤ 0.1 as the reference. Hazard ratios were computed for each 2-year interval starting with 2002–04 until 2014–16 in addition to an overall HR for the combined 15-year study period. We fitted sequential Cox proportional models: (i) crude/unadjusted model; (ii) age, sex, region, and smoking-adjusted model; and (iii) multivariate model including age, sex, race, region, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, statin use, and blood pressure medication use. We used the same crude/unadjusted and adjusted models for secondary outcomes where we examined the association between frailty and specific ASCVD events.

In a sensitivity analysis, we removed CVD related variables from the FI (atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, and heart failure) and repeated the main analysis. Additional analyses of frailty and CVD mortality that were stratified by sex and race were also done. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

This study was approved, and the requirement for obtaining patient informed consent was waived, by the VHA Boston institutional review board.

Results

The total number of US Veterans included in the analysis was 3 068 439 from 2002 to 2017. Beginning in 2002, the cohort included 1 606 703 patients. This number grew over the subsequent years, ranging from 1 899 316 to 1 973 370 patients for any single 2-year period, as shown in Table 1. In 2002, mean age was 74.1 (standard deviation: 5.8), 98.2% were male, and 91.1% were White. By 2014, mean age was 76.0 (8.3) years, 97.9% were male, and 87.5% were White. In terms of insurance, the numbers varied slightly overtime, ∼90% had Medicare, ∼9% had both Medicare and Medicaid, and < 1% of patients had VA coverage without either Medicare or Medicaid.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Veterans aged ≥65 years, 2002–16

| 2002 (n = 1 606 703) | 2004 (n = 1 908 956) | 2006 (n = 1 973 370) | 2008 (n = 1 950 516) | 2010 (n = 1 899 316) | 2012 (n = 1 919 945) | 2014 (n = 1 908 495) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 74.1 ± 5.8 | 75.1 ± 6.2 | 75.9 ± 6.6 | 76.4 ± 7.1 | 76.6 ± 8.1 | 76.3 ± 8.1 | 76.0 ± 8.3 |

| Race (%) | |||||||

| White | 91.1 | 91.0 | 90.8 | 90.4 | 89.7 | 88.8 | 87.5 |

| Black | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 10.4 |

| Other | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||||

| Former | 71.4 | 70.9 | 70.4 | 69.6 | 68.5 | 66.8 | 65.0 |

| Current | 6.4 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 12.4 | 14.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 15.3 | 17.7 | 19.3 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.8 | 19.1 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 46.5 | 48.8 | 49.6 | 48.7 | 46.7 | 44.3 | 41.2 |

| Cerebrovascular accident (%) | 21.1 | 24.9 | 27.0 | 27.4 | 26.4 | 24.9 | 23.1 |

| Heart failure (%) | 17.8 | 20.6 | 22.1 | 22.0 | 21.0 | 19.9 | 18.4 |

| Hypertension (%) | 77.7 | 82.6 | 85.7 | 86.4 | 85.2 | 84.1 | 82.7 |

| Diabetes (%) | 32.1 | 34.9 | 37.6 | 39.3 | 40.0 | 40.8 | 40.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 8.8 | 11.7 | 15.8 | 19.9 | 21.9 | 22.9 | 22.3 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (%) | 17.8 | 13.7 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 8.8 |

| Use of anti-hypertensive medication (%) | 71.0 | 75.1 | 76.6 | 75.0 | 70.6 | 67.6 | 66.0 |

| Use of statins (%) | 44.4 | 53.0 | 58.6 | 60.0 | 57.8 | 55.8 | 54.5 |

| Frailty (%) | |||||||

| Non-frail | 35.5 | 28.8 | 25.3 | 24.2 | 24.8 | 25.2 | 25.2 |

| Pre-frail | 32.6 | 31.2 | 30.4 | 29.5 | 28.7 | 28.4 | 29.3 |

| Mild frailty | 18.9 | 20.7 | 21.1 | 20.9 | 20.2 | 19.7 | 20.3 |

| Moderate frailty | 8.7 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 12.7 | 12.6 |

| Severe frailty | 4.3 | 7.8 | 10.4 | 12.2 | 13.3 | 14.1 | 12.6 |

| Frailty score [median (IQR)] | 0.16 (0.10–0.23) | 0.16 (0.10–0.29) | 0.19 (0.10–0.29) | 0.19 (0.13–0.32) | 0.19 (0.13–0.32) | 0.19 (0.10–0.32) | 0.19 (0.10–0.32) |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Frailty indices

In 2002, the median (interquartile range) frailty score was 0.16 (0.10–0.23). This increased and stabilized to 0.19 (0.10–0.32) for 2006–14. Overall, frailty became more prevalent, increasing from 31.9% in 2002 to 45.5% in 2014. The degrees of frailty also changed over time, with the prevalence of patients with severe frailty increasing (from 4.3% in 2002 to 12.6% in 2014), pre-frailty decreasing (32.6–29.3%), mild frailty increasing (18.9–20.3%), and moderate frailty increasing (8.7–12.6%). A sample of selected comorbidities is shown in Table 1.

Frailty and cardiovascular mortality

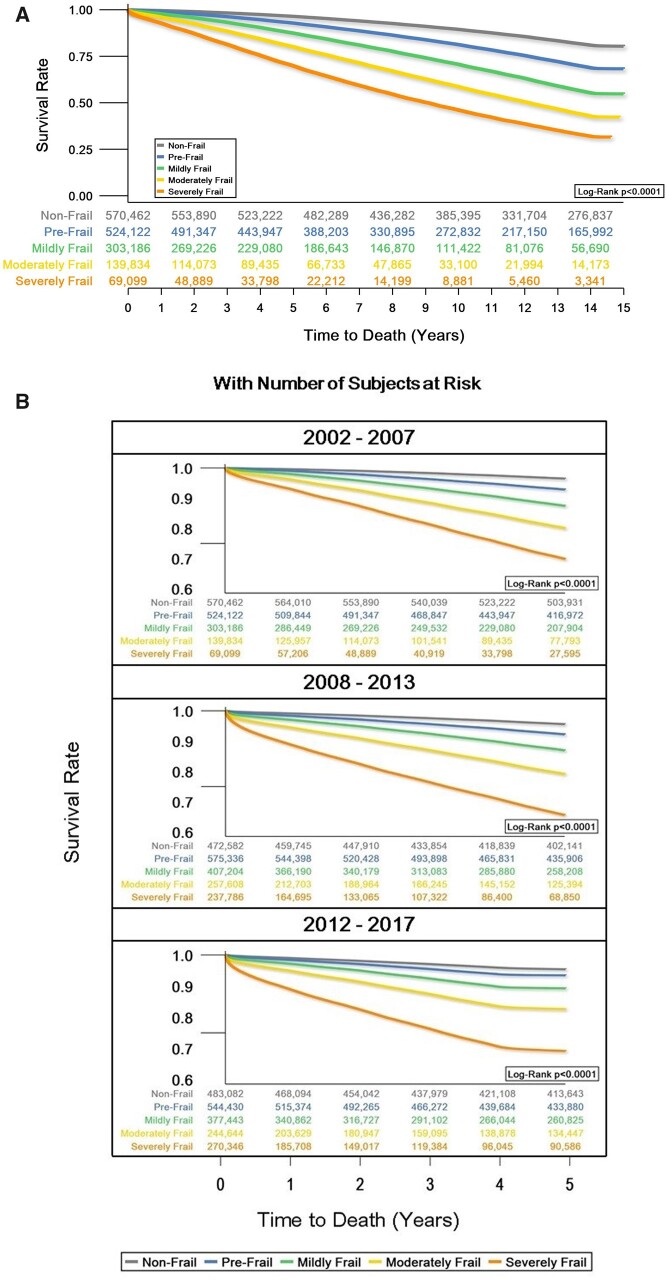

Figure 1A shows the survival rate of the 2002 cohort over the subsequent 15 years, through 2017, broken down by frailty category. Figure 1B shows the 5-year survival rate for cohorts from 2002, 2008, and 2012. Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years for 2-year survival analysis outcomes are also included in the Supplementary material online, Table S3.

Figure 1.

Overall (A) and 5-year (B) survival rate from cardiovascular mortality by frailty category, 2002–17, with number of subjects at risk. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, region, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, statin use, and blood pressure medication use.

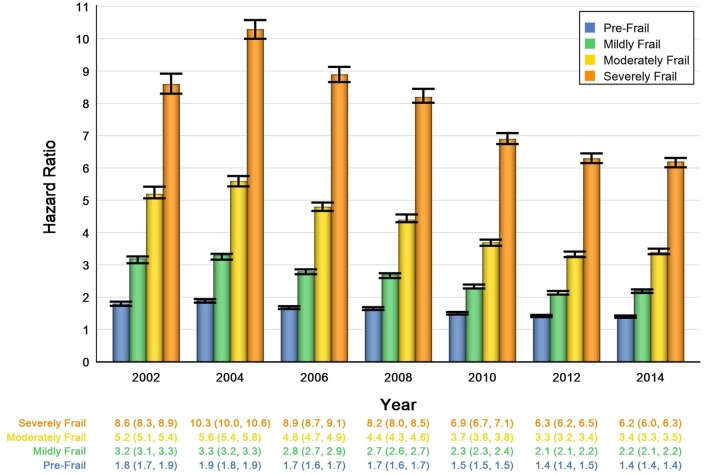

Table 2 and Figure 2 show the HRs for CVD mortality and frailty. The presence of frailty was associated with increased risk of CVD mortality at every stage of frailty, with HR and 95% CI for patients with pre-frailty ranging from 1.8 (95% CI: 1.7–1.9) in 2002 and 1.4 (95% CI: 1.4–1.4) in 2014 to 8.6 (95% CI: 8.3–8.9) in 2002 and 6.2 (95% CI: 6.0–6.3) for patients with severe frailty. The more severe the frailty level, the higher the risk of CVD mortality. However, from 2002 to 2014, the risk of CVD mortality decreased for each frailty strata: pre-frail HR 1.8 (95% CI: 1.7–1.9) in 2002 to 1.4 (95% CI: 1.4–1.4) in 2014, mild frailty HR 3.2 (95% CI: 3.1–3.3) in 2002 to 2.2 (95% CI: 2.1–2.2) in 2014, moderate frailty HR 5.2 (95% CI: 5.1–5.4) in 2002 to 3.4 (95% CI: 3.3–3.5) in 2014, and severe frailty HR 8.6 (95% CI: 8.3–8.9) in 2002 to 6.2 (95% CI: 6.0–6.3) in 2014. In a sex-stratified analysis, the magnitudes of the HR for men and women varied slightly (with men tending to have slightly higher HR for CVD mortality at a given frailty severity), but the overall trends were unchanged. In an analysis stratified by race (categorized as White, Black, and other), again the magnitudes of the HRs varied slightly, but the overall trends remained the same. See Supplementary material online, Table S4 for full details of both additional analyses.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for 2-year cardiovascular mortality by frailty among US Veterans aged ≥65 years, 2002–16

| 2002 (n = 1 606 699) | 2004 (n = 1 908 952) | 2006 (n = 1 973 370) | 2008 (n = 1 950 514) | 2010 (n = 1 899 315) | 2012 (n = 1 919 945) | 2014 (n = 1 908 495) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-frail | FI ≤ 0.1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Pre-frail | 0.1 > FI ≤ 0.2 | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 1.7 (1.6–1.7) | 1.7 (1.6–1.7) | 1.5 (1.5–1.5) | 1.4 (1.4–1.5) | 1.4 (1.4–1.4) |

| Mildly frail | 0.2 > FI ≤ 0.3 | 3.2 (3.1–3.3) | 3.3 (3.2–3.3) | 2.8 (2.7–2.9) | 2.7 (2.6–2.7) | 2.3 (2.3–2.4) | 2.1 (2.1–2.2) | 2.2 (2.1–2.2) |

| Moderately frail | 0.3 > FI ≤ 0.4 | 5.2 (5.1–5.4) | 5.6 (5.4–5.8) | 4.8 (4.7–4.9) | 4.4 (4.3–4.6) | 3.7 (3.6–3.8) | 3.3 (3.2–3.4) | 3.4 (3.3–3.5) |

| Severely frail | 0.4 > FI | 8.6 (8.3–8.9) | 10.3 (10.0–10.6) | 8.9 (8.7–9.1) | 8.2 (8.0–8.5) | 6.9 (6.7–7.1) | 6.3 (6.2–6.5) | 6.2 (6.0–6.3) |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, region, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, statin use, and blood pressure medication use.

FI, frailty index.

Figure 2.

Risk of cardiovascular mortality by frailty category, 2002–16. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, region, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, statin use, and blood pressure medication use.

All results were statistically significant to the level of 0.0083 (Bonferroni correction for multiple testing).

Sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis that excluded CVD related variables from the FI was performed and showed that the trends for CVD mortality according to frailty status and over time were unchanged (Supplementary material online, Table S5). Additionally, the same sensitivity analyses were run for each secondary outcome (MI/fatal MI, stroke/fatal stroke, and revascularization) and showed similar trends.

Secondary outcomes

Myocardial infarction/fatal myocardial infarction

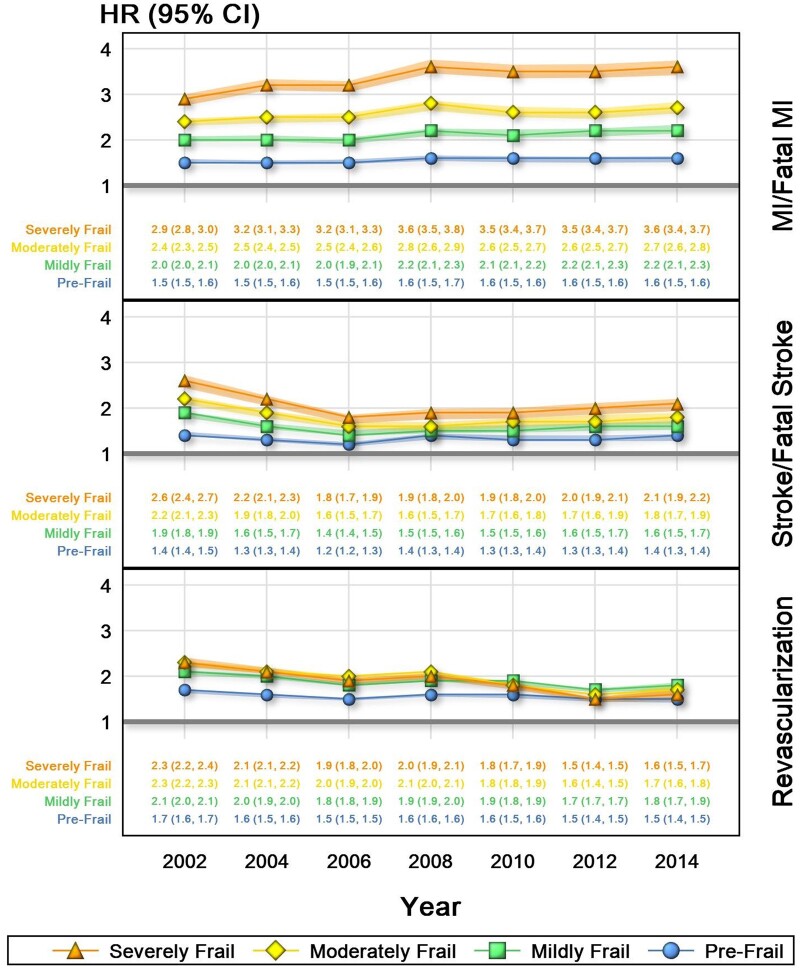

Risk of MI or death from MI was most strongly associated with frailty, with HR ranging from 1.5 (95% CI: 1.5–1.6) in 2002 to 1.6 (95% CI: 1.5–1.6) in 2014 for patients with pre-frailty and HR ranging from 2.9 (95% CI: 2.8–3.0) in 2002 to 3.6 (95% CI: 3.4–3.7) in 2014 for patients with severe frailty. Over this same time period, there was little change in the risk of MI or fatal MI as associated with frailty or the degree of frailty, with patients who had severe frailty having a slightly higher risk (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk of secondary outcomes by frailty category, 2002–16. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, region, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, statin use, and blood-pressure medication use. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction.

Stroke/fatal stroke

Similar trends were seen in stroke, with the risk of stroke or death from stroke being HR 1.4 (95% CI: 1.4–1.5) in 2002 to 1.4 (95% CI: 1.3–1.4) in 2014 for those with pre-frailty, and HR of 2.6 (95% CI: 2.4–2.7) in 2002 to 2.1 (95% CI: 1.9–2.2) for those with severe frailty. However, from 2002 to 2014, the risk of incident stroke or death from stroke across each category of frailty was lower (Figure 3).

Revascularization

Hazard ratios of revascularization (PCI or CABG) were similar across categories of frailty. For patients with pre-frailty, the HR in 2002 was 1.7 (95% CI: 1.6–1.7) and 1.5 (95% CI: 1.4–1.5) in 2014, whereas for patients with severe frailty, the HR in 2002 was 2.3 (95% CI: 2.2–2.4) and 1.6 (95% CI: 1.5–1.7) in 2014. As seen with stroke and fatal stroke, though to a smaller degree, the association between risk for revascularization and degree of frailty was lower over time (Figure 3).

Discussion

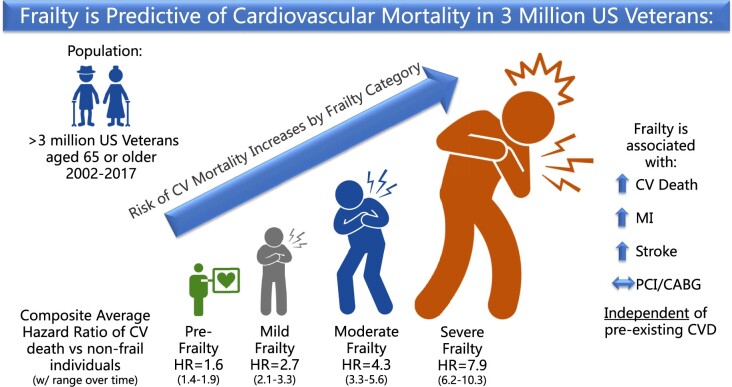

In this study of frailty and CVD in US Veterans aged 65 years and older, we found that frailty is associated with a higher risk of CVD mortality in a dose-dependent manner, even after adjusting for underlying CVD and preventive treatment (Graphical Abstract)

Structured Graphical Abstract.

As frailty increases, so does the risk of CVD mortality.

Frailty is an increasingly common condition among older adults in the USA and across the world, and patients with frailty are often those most likely to interact with the medical system.20 Our understanding of frailty is of yet incomplete, and its utility for the clinician is evolving. Fortunately, quick and cost-effective tests such as gait speed and grip strength have proven to be excellent markers of frailty and can be implemented into almost any clinical practice.21 , 22 This study represents one of the largest and most contemporary evaluations of the interplay between CVD and frailty. A recent pooled analysis of 154 000 patients combined data from 14 large cardiovascular studies in the late 1990s through the early 2000s and reported an association between frailty and CVD [69.7 ± 9.6 years (non-frail), 72.1 ± 9.4 years (pre-frail), 74.6 ± 9.3 years (frail), HR for cardiovascular death 1.9 patients with frailty compared with non-frail patients; 95% CI: 1.8–2.1].9 The current study strengthens and elaborates on these findings by not only showing that the associations for CVD risk remain in a modern cohort, but by also allowing us to see the trends as they relate to severity of frailty and changes over time. When these data are compared with prior work on all-cause mortality and frailty in this cohort of US Veterans, the risk of CVD mortality is even higher than overall mortality, suggesting that CVD may be a major driver of mortality in patients with the most severe frailty.10 This might suggest a similar or shared pathophysiology of frailty and CVD; be it inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, or other biologic pathways leading to a final common pathway of CVD death.

The increasing prevalence and severity of frailty, as well as the trend towards lower HRs from 2002 to 2012 have important clinical implications. The rates of death from CVD overall have been improving in the USA, with this relationship holding true for both ischaemic heart disease and stroke.23 Our study does not answer the question of why patients with frailty appear to be at lower risk of CVD death in 2017 compared with 2002, but one possible contributor would be the improvement in medical management of patients with CVD. From 2002 to 2013, Salami et al.24 showed that the use of statins rose nearly 80% in the USA. Over this same time period, advances in therapies for coronary disease including more effective anti-platelet agents and drug-eluting stents (as well improved bare metal stents) were rolled out.25–27 Furthermore, more aggressive management of older patient’s risk factors has become the norm, validated by the results of the SPRINT trial and codified in national guidelines such as the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines and 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.28–30 Although there is some concern that the most vulnerable older adults were not included in SPRINT, our data suggest that it is the frailest patients who are at the highest risk of CVD death and cardiovascular events. It is highly probably that carefully targeted prevention, in line with individual goals of care, for this population could significantly reduce the burden of CVD and resultant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, while the frail patients are certainly susceptible to the harms of polypharmacy or therapy side effects, they may also derive the greatest benefit from optimal medical management of their cardiovascular risk profile.31

Our study has several strengths, including the richness of the data. With the VA nationwide electronic medical records combined with federal claim and death data, we were able to see a granular picture of a large cohort of patients over an extended period of time. Additionally, with a study population of 3 million patients, we were still able to get quality information on demographics that are less represented in the VA than elsewhere.

Our study also has important limitations. While VA data can provide a large, rich source of clinical variables, US Veterans may not be representative of the general population as Veterans often carry a greater burden of multimorbidity and psychiatric conditions. However, when compared with Medicare patients, VA patients and Medicare patients are more comparable than has been previously thought.32 While only ∼2% were female, this represents over 60 000 women, and our sex-stratified analyses (shown in Supplementary material online, Table S4) showed no change in the trends seen. Furthermore, there were high rates of medical therapy in this cohort for hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, and this was in part a motivating factor to include statin and anti-hypertensive use as covariates in our model when looking at HRs for the primary and secondary outcomes. However, this may also speak to the power of prevention in populations at such high risk of CVD. Although the FI is a well validated measure of frailty, there are other definitions that do not rely on claims. The use of claims may both under and over-estimate covariates and event rates depending on how accurately claims are applied in the clinic; however, we linked VA data to Medicare and Medicaid to minimize loss of data.

Further studies are needed to consider the dynamics of frailty and CVD. Outstanding questions include how to best operationalize this connection; as a screening tool, therapeutic target, or perhaps both. Additionally, while this study looked at claims data, self-reported or directly measured frailty data could also be of use.

Conclusion

Given the high burden of both CVD and frailty, understanding the relationship between them will be important as we continue to refine the approach to caring for these patients. Our data show that in US Veterans 65 years and older, increasing frailty is associated with an increased risk of CVD mortality. As the population ages, further characterization of this interplay will be critical for the optimization of care of all older adults.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This study was approved, and the requirement for obtaining patient informed consent was waived, by the VHA Boston institutional review board. This work is dedicated to the memory of Dr. William Shrauner.

Funding

This research was supported by Veterans Administration (VA) Merit Award I01 CX001025 (Dr Wilson and Dr Cho) and VA CSR&D CDA-2 award IK2-CX001800 (Dr Orkaby). This publication does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. Support for VA/Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Health Services Research and Development Service, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Contributor Information

William Shrauner, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; Division of Aging, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont St Boston, MA 02120, USA; Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Boston Medical Center, One Boston Medical Center Pl, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

Emily M Lord, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA.

Xuan-Mai T Nguyen, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA.

Rebecca J Song, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA.

Ashley Galloway, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA.

David R Gagnon, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; New England GRECC (Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center) VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave Boston, MA 02130, USA.

Jane A Driver, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; Division of Aging, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont St Boston, MA 02120, USA; New England GRECC (Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center) VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave Boston, MA 02130, USA.

J Michael Gaziano, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; Division of Aging, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont St Boston, MA 02120, USA.

Peter W F Wilson, Atlanta VA Medical Center, 1670 Clairmont Rd, Decatur, GA 30033, USA; Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, 1525 Clifton Rd, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, 1518 Clifton Rd, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Luc Djousse, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; Division of Aging, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont St Boston, MA 02120, USA.

Kelly Cho, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; Division of Aging, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont St Boston, MA 02120, USA.

Ariela R Orkaby, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02130, USA; Division of Aging, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont St Boston, MA 02120, USA; New England GRECC (Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center) VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Ave Boston, MA 02130, USA.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ et al. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:747–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newman AB, Gottdiener JS, McBurnie MA et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group.Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M158–M166. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fugate Woods N, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL et al. ; Women’s Health Initiative. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the women’s health initiative observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vestergaard S, Patel KV, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM. Characteristics of 400-meter walk test performance and subsequent mortality in older adults. Rejuvenation Res 2009;12:177–184. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adabag S, Vo TN, Langsetmo L et al. Frailty as a risk factor for cardiovascular versus noncardiovascular mortality in older men: results from the MrOS sleep (outcomes of sleep disorders in older men) study. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e008974. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang X, Lupón J, Vidán MT et al. Impact of frailty on mortality and hospitalization in chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e008251. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farooqi MAM, Gerstein H, Yusuf S, Leong DP. Accumulation of deficits as a key risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: a pooled analysis of 154 000 individuals. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e014686. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dewan P, Jackson A, Jhund PS et al. The prevalence and importance of frailty in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction—an analysis of PARADIGM-HF and ATMOSPHERE. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:2123–2133. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilkinson C, Wu J, Searle SD et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and frailty: insights from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. BMC Med 2020;18:401. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01870-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkinson C, Clegg A, Todd O et al. Atrial fibrillation and oral anticoagulation in older people with frailty: a nationwide primary care electronic health records cohort study. Age Ageing 2021;50:772–779. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho YL et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. Veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019;74:1257–1264. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016;45:353–360. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Price LE, Shea K, Gephart S. The vVeterans Affairs’s corporate data warehouse: uses and implications for nursing research and practice. Nurs Adm Q 2015;39:311–318. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. NDI: Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention. Joint Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) Suicide Data Repository – National Death Index (NDI). http://vaww.virec.research.va.gov/Mortality/Overview.htm (October 2018).

- 18. US Department of Veterans Affairs. System of Records Notice 97VA10P1: Consolidated Data Information System-VA. 76 FR 25409. Published May 4, 2011; amended March 3, 2015. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PAI-2019-VA/xml/PAI-2019-VA.xml#97VA10P1 (7 December 2021).

- 19. Rockwood K, Rockwood MRH, Mitnitski A. Physiological redundancy in older adults in relation to the change with age in the slope of a frailty index. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02667.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. García-Nogueras I, Aranda-Reneo I, Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Abizanda P. Use of health resources and healthcare costs associated with frailty: the FRADEA Study. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rothman MD, Leo-Summers L, Gill TM. Prognostic significance of potential frailty criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2211–2216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02008.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, Briggs R, Aihie Sayer A. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age Ageing 2003;32:650–656. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mensah GA, Wei GS, Sorlie PD et al. Decline in cardiovascular mortality: possible causes and implications. Circ Res 2017;120:366–380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the medical expenditure panel survey. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:56–65. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0904327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M et al. ; ISAR-REACT 5 Trial Investigators. Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1524–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bønaa KH, Mannsverk J, Wiseth R et al. ; NORSTENT Investigators. Drug-eluting or bare-metal stents for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1242–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK et al. ; SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103–2116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:1269–1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066; Erratum in: Hypertension 2018;71: e136–e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ridker PM, Lonn E, Paynter NP, Glynn R, Yusuf S. Primary prevention with statin therapy in the elderly: new meta-analyses from the contemporary JUPITER and HOPE-3 randomized trials. Circulation 2017;135:1979–1981. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wong ES, Wang V, Liu C-F, Hebert PL, Maciejewski ML. Do veterans health administration enrollees generalize to other populations? Med Care Res Rev 2016;73:493–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.