Abstract

Objectives

Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, were evaluated in a 6-month, double-blind, phase 3 study in Chinese patients with active (polyarthritic) psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and inadequate response to ≥1 conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Methods

Patients were randomised (2:1) to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (N=136) or placebo (N=68); switched to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily after month (M)3 (blinded). Primary endpoint: American College of Rheumatology (ACR50) response at M3. Secondary endpoints (through M6) included: ACR20/50/70 response; change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI); ≥75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75) response, and enthesitis and dactylitis resolution. Safety was assessed throughout.

Results

The primary endpoint was met (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, 38.2%; placebo, 5.9%; p<0.0001). M3 ACR20/ACR70/PASI75 responses, and enthesitis and dactylitis resolution rates, were higher and HAQ-DI reduction was greater for tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo. Incidence of adverse events (AEs)/serious AEs (M0–3): 68.4%/0%, tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily; 75.0%/4.4%, placebo. One death was reported with placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (due to accident). One serious infection, non-serious herpes zoster, and lung cancer case each were reported with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily; four serious infections and one non-serious herpes zoster case were reported with placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (M0–6). No non-melanoma skin cancer, major adverse cardiovascular or thromboembolism events were reported.

Conclusion

In Chinese patients with PsA, tofacitinib efficacy was greater than placebo (primary and secondary endpoints). Tofacitinib was well tolerated; safety outcomes were consistent with the established safety profile in PsA and other indications.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Arthritis; Arthritis, Psoriatic; Inflammation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib has demonstrated greater efficacy over placebo in two global phase 3 studies (OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond) in adult patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA). In both studies, adverse events were reported more frequently with tofacitinib than placebo. The long-term extension study (OPAL Balance) demonstrated tofacitinib efficacy and safety consistent with phase 3 studies.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Although tofacitinib is approved for the treatment of PsA in Taiwan, there are no approved advanced therapies (biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug [DMARD] or targeted synthetic DMARD) for PsA in mainland China, highlighting an unmet need for new treatments for patients with PsA in China.

The global phase 3 tofacitinib clinical trial programme in patients with PsA did not include mainland China and few patients from Taiwan were enrolled; thus, this study provides insight into the benefit/risk of tofacitinib in Chinese patients. Further, this is the first focused, nationwide, phase 3 clinical trial evaluating an advanced therapy for PsA in Chinese patients.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The results of this study are the first to demonstrate that tofacitinib may be an effective treatment option for Chinese patients with active PsA.

Tofacitinib was well tolerated, with safety outcomes consistent with the established safety profile in the PsA global clinical programme and other indications.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease with musculoskeletal, skin and nail manifestations1 2 that can substantially impair patients’ health-related quality of life.3 The global prevalence of PsA in patients with psoriasis is approximately 30%2; however, this varies across geographical regions. In Chinese patients, the prevalence of PsA is approximately 10%,4 5 although this could be underestimated in the Asia-Pacific region as patients with musculoskeletal disorders are often subject to delays in diagnosis. Other challenges that patients in this region experience include delayed or limited access to treatment with advanced therapies.5 6 Furthermore, due to limited access to information, patients may seek treatment to improve pain and disability, including traditional Chinese medicines, rather than treating signs and symptoms of inflammatory arthritis, further delaying treatment with advanced therapies.6 7

Current treatment guidelines for PsA recommend initial therapy with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate.8–11 International guidelines recommend treatment with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors across most psoriatic disease subtypes9 or for patients with inadequate response to at least one biological DMARD (bDMARD), including tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), or for whom treatment with a bDMARD is not appropriate.8 10 12 To date, although bDMARDs, including TNFi and interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors, and targeted synthetic DMARDs, are approved in Taiwan for the treatment of PsA,12 these advanced treatments are not approved in mainland China. As such, there is an unmet need for bDMARDs or targeted synthetic DMARDs in Chinese patients.

Tofacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor for the treatment of PsA. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily were demonstrated in two global phase 3 studies, OPAL Broaden (NCT01877668)13 and OPAL Beyond (NCT01882439),14 and one long-term extension study, OPAL Balance (NCT01976364),15 in adult patients with active PsA. However, mainland China was not included in the global clinical development programme of tofacitinib in PsA, and although tofacitinib is approved in Taiwan, only a small number of patients from Taiwan were enrolled in the programme. To date, there are limited data supporting the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with PsA. Here, we report the results from the first phase 3 randomised clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety data for tofacitinib in Chinese patients with active PsA.

Methods

Patients

Eligible Chinese patients were aged ≥18 years, with a diagnosis of PsA for ≥6 months and fulfilled the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis criteria with active arthritis, defined as ≥3 tender/painful joints (out of 68 joints assessed) and ≥3 swollen joints (out of 66 joints assessed) at both screening and baseline, and confirmed active plaque psoriasis at screening. Patients had prior inadequate response or intolerance to ≥1 csDMARD. Full eligibility criteria are listed in the online supplemental material.

rmdopen-2022-002559supp001.pdf (729.9KB, pdf)

Study design

This was a phase 3, 6-month, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in adult Chinese patients with active (polyarthritic) PsA (NCT03486457), conducted at 38 centres in China between August 2018 and April 2021.

Eligible patients were randomised (2:1) in a blinded manner to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo advancing to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (online supplemental figure 1). Randomisation was performed using an automated web/telephone randomisation system. At screening, each patient was allocated a unique patient identification number, and at the baseline/day 1 visit, the next sequential randomisation number was provided.

At the end of the placebo-controlled phase (month 3), all patients receiving placebo were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in a blinded manner (active treatment phase) for the remainder of the study (placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily). Investigators, patients and the sponsor were blinded to treatment allocations throughout.

All patients received a stable dose of a single csDMARD (methotrexate ≤20 mg/week or sulfasalazine ≤3 g/day) throughout. All concomitant bDMARDs were prohibited. Prior treatment with TNFi was permitted but must have been discontinued prior to study start. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were permitted at the same dose throughout the study unless adjustments were required for safety reasons. Use of Tripterygium wilfordii, a traditional Chinese medicine with an immunosuppressive effect and the potential to interact with tofacitinib, was prohibited during the study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint of the trial was the proportion of patients achieving ≥50% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria (ACR50) at month 3. A subgroup analysis of ACR50 response rates was conducted according to baseline demographics/disease characteristics. Secondary endpoints (assessed up to month 6) included: ACR50 response rates at remaining time points; ACR improvements ≥20%/≥70% (ACR20/70); change from baseline in ACR response components; Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) score and resolution of enthesitis defined as LEI=0 in patients with baseline LEI >0; Dactylitis Severity Score (DSS) and resolution of dactylitis defined as DSS=0 in patients with baseline DSS >0; Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) response (decrease from baseline ≥0.30 for patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥0.30 or decrease from baseline ≥0.35 for patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥0.35); Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria response rate; Physician’s Global Assessment of Psoriasis (PGA-PsO) change from baseline in patients with baseline PGA-PsO >0 and response rates (PGA-PsO score of 0 or 1 and decrease from baseline ≥2) in patients with baseline PGA-PsO ≥2 and rates of ≥75% Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75) improvement in patients with baseline psoriatic body surface area ≥3% and baseline PASI >0. Further details on efficacy endpoints, patient-reported outcomes and sensitivity analyses assessed up to month 6 are described in the online supplemental material.

Safety assessments included incidence of adverse events (AEs) from months 0 to 3 and months 0 to 6, classified according to Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities V.24.0, including serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation. AEs of special interest were reported (see online supplemental material).

Physical examinations, vital signs and clinical laboratory tests were evaluated up to month 6.

Owing to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, recruitment was paused for a period of 2 months. Virtual evaluations were carried out for ongoing patients during the peak of the pandemic and collected information such as the occurrence of AEs. Patients had laboratory samples collected and tested at their local hospital, and reports were sent to the respective study investigator.

Statistical analysis

For the primary endpoint of ACR50 response rate at month 3, assuming a placebo response rate of 9.5% and factoring in the number of patients with missing data owing to COVID-19, enrolment of approximately 204 patients was planned to provide ≥90% power to detect a difference of 18.5% from placebo, based on normal approximation (without continuity correction) at the two-sided 5% significance level.

Efficacy analyses included all patients who were randomised and received ≥1 dose of study medication (full analysis set). Treatment comparisons up to month 3, including the primary efficacy comparison, were tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo and for analyses from month 3 to month 6 were tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.

For binary endpoints, the normal approximation to the difference in binomial proportions was used to test differences between tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo, and to generate 95% CIs and p values for the differences. Missing values were counted as non-response. A supportive analysis of ACR50 response rate, excluding patients who had a missing or remote visit at month 3 owing to COVID-19, was performed. Continuous endpoints were analysed using a mixed model for repeated measures, including treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction, baseline value as fixed effects and an unstructured variance covariance matrix for within-patient correlation, without imputation for missing values. Least squares (LS) means of the difference between tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo and the corresponding standard error, 95% CI and p values were calculated.

For endpoints other than the primary endpoint, differences between tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo were analysed without multiple comparison adjustments; therefore, 95% CIs and p values should only be considered nominal.

A subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of baseline characteristics on ACR50 response rates at month 3. Estimated response rates were reported. Two-sided 95% CIs were provided for differences in response rates based on the normal approximation for binomial proportions.

Safety data were analysed descriptively throughout the study in the safety analysis set (all patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication).

Results

Patients

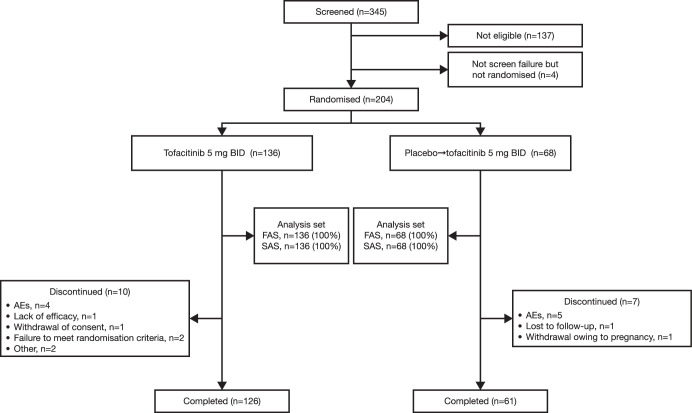

In total, 345 Chinese patients with active PsA were screened, and 204 patients were randomised and treated (figure 1); of these, 136 patients received tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, and 68 patients received placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar between treatment groups (table 1). However, more patients had prior bDMARD use and presence of enthesitis and dactylitis; duration of PsA was longer, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were lower with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily than placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. AE, adverse event; BID, twice daily; FAS, full analysis set; n, number of patients; SAS, safety analysis set.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics (safety analysis set*)

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=136) | Placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=68) | Total (N=204) | |

| Patient demographics | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 45.3 (11.6) | 43.9 (10.4) | 44.8 (11.2) |

| Aged ≥65 years, n (%) | 9 (6.6) | 1 (1.5) | 10 (4.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 79 (58.1) | 42 (61.8) | 121 (59.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.6 (3.3) | 24.9 (3.9) | 24.7 (3.5) |

| Baseline disease characteristics | |||

| Duration of PsA (years), mean (SD) | 5.0 (6.0) | 3.5 (4.4) | 4.5 (5.5) |

| Swollen joint count (66), mean (SD) | 9.4 (7.7) | 9.9 (7.8) | 9.6 (7.7) |

| Tender/painful joint count (68), mean (SD) | 16.1 (12.1) | 14.9 (10.4) | 15.7 (11.5) |

| HAQ-DI, mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.5) |

| PGA-PsO, mean (SD)† | 2.2 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.8) |

| PASI, median (range)‡ | 8.6 (1.4 to 58.6) | 8.0 (2.6 to 42.0) | 8.3 (1.4 to 58.6) |

| NAPSI, mean (SD)§ | 3.9 (2.1) | 4.0 (2.3) | 4.0 (2.2) |

| DAS28-3(CRP), mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.1) |

| Presence of enthesitis (LEI >0), n (%) | 71 (52.2) | 28 (41.2) | 99 (48.5) |

| Presence of dactylitis (DSS >0), n (%) | 93 (68.4) | 41 (60.3) | 134 (65.7) |

| CRP (mg/L), median (range) | 4.9 (0.2 to 115.0) | 8.2 (0.3 to 73.9) | 5.3 (0.2 to 115.0) |

| CRP >2.87 mg/L, n (%) | 89 (65.4) | 45 (66.2) | 134 (65.7) |

| SF-36v2 PCS, mean (SD) | 38.4 (8.2) | 38.5 (8.5) | 38.4 (8.3) |

| SF-36v2 MCS, mean (SD) | 42.0 (11.3) | 45.2 (11.1) | 43.1 (11.3) |

| Prior bDMARD use, n (%)¶ | 24 (17.6) | 6 (8.8) | 30 (14.7) |

| Concomitant medication use up to month 6, n (%) | |||

| Corticosteroids | 6 (4.4) | 5 (7.4) | 11 (5.4) |

| NSAIDs | 49 (36.0) | 41 (60.3) | 90 (44.1) |

| csDMARDs | 136 (100) | 68 (100) | 204 (100) |

| Methotrexate | 126 (92.6) | 62 (91.2) | 188 (92.2) |

| Sulfasalazine | 10 (7.4) | 6 (8.8) | 16 (7.8) |

*All patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication.

†Among patients with baseline PGA-PsO score >0: N=133 in the tofacitinib 5 mg BID group; N=66 in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID group.

‡Among patients with baseline psoriatic BSA ≥3% and PASI >0: N=75 in the tofacitinib 5 mg BID group; N=27 in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID group.

§Among patients with baseline NAPSI >0: N=99 in the tofacitinib 5 mg BID group; N=54 in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID group.

¶bDMARDs may have been used for psoriasis or other medical purposes. bDMARDs are not approved for the treatment of PsA in mainland China.

bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C-reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DAS28-3(CRP), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints with CRP; DSS, Dactylitis Severity Score; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; MCS, Mental Component Summary; N, number of evaluable patients; n, number of patients with the specified characteristic; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PGA-PsO, Physician’s Global Assessment of Psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SD, standard deviation; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey, version 2 acute.

Efficacy

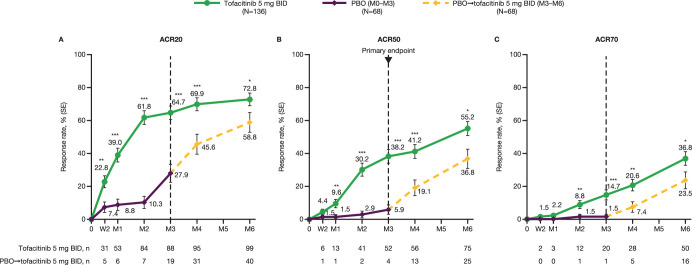

At month 3, the primary endpoint of the study was met, with a significantly greater ACR50 response rate observed with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily than placebo (38.2% vs 5.9%, respectively; p<0.0001; figure 2). Greater improvements in ACR50 response rate with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo occurred as early as month 1. From month 3 to month 6, improvements continued with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and increased in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group (figure 2; table 2). In the supportive analysis excluding patients impacted by COVID-19 (eight patients in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group and four patients in the placebo group), ACR50 response rates at month 3 were consistent with the overall findings (40.6% and 6.3%, respectively; table 2).

Figure 2.

(A) ACR20, (B) ACR50 and (C) ACR70 response rates to month 6 in Chinese patients with PsA.†‡ The dotted line at month 3 represents the time point at which patients in the placebo group were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg BID from month 3 for the remainder of the study. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus placebo (through month 3) or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID (for remainder of study). †All randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication. ‡Missing values were considered as non-response. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ACR20/50/70, ≥20/50/70% improvement, respectively, in ACR response criteria; BID, twice daily; M, month; n, number of patients meeting response criteria; N, number of patients in full analysis set; PBO, placebo; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SE, standard error; W, week.

Table 2.

Efficacy endpoints at month 3 and month 6 (full analysis set)†‡

| Endpoint | Month 3 | Month 6 | ||||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=136) |

Placebo (N=68) |

Difference (SE) (95% CI) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=136) |

Placebo→ tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=68) |

Difference (SE) (95% CI) | |

| ACR50, n (%) (SE) | 52 (38.2) (4.2)§ | 4 (5.9) (2.9)§ |

32.4 (5.1)§ (22.5 to 42.3)*** |

75 (55.2) (4.3) | 25 (36.8) (5.9) | 18.4 (7.2) (4.2 to 32.6)* |

| ACR50 excl. COVID-19, n (%) (SE) | 52 (40.6) (4.3) (N1=128) |

4 (6.3) (3.0) (N1=64) |

34.4 (5.3) (24.0 to 44.8)*** |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ACR20, n (%) (SE) | 88 (64.7) (4.1) | 19 (27.9) (5.4) | 36.8 (6.8) (23.4 to 50.1)*** |

99 (72.8) (3.8) | 40 (58.8) (6.0) | 14.0 (7.1) (0.1 to 27.9)* |

| ACR70, n (%) (SE) | 20 (14.7) (3.0) | 1 (1.5) (1.5) |

13.2 (3.4) (6.6 to 19.8)*** |

50 (36.8) (4.1) | 16 (23.5) (5.1) | 13.2 (6.6) (0.3 to 26.2)* |

| HAQ-DI response, n (%) (SE)¶†† |

54 (65.1) (5.2) (N1=83) |

16 (41.0) (7.9) (N1=39) |

24.0 (9.5) (5.5 to 42.6)* |

61 (73.5) (4.8) (N1=83) |

26 (66.7) (7.6) (N1=39) |

6.8 (9.0) (−10.8 to 24.4) |

| ∆HAQ-DI (SE) | −0.3 (0.0) (N1=127) |

−0.1 (0.0) (N1=62) |

−0.2 (0.1) (−0.3 to −0.1)*** |

−0.4 (0.0) (N1=126) |

−0.3 (0.0) (N1=61) |

−0.1 (0.0) (−0.2 to 0.0) |

| ∆TJC (SE) | −8.9 (0.6) (N1=123) |

−1.9 (0.9) (N1=60) |

−7.0 (1.1) (−9.2 to −4.8)*** |

−11.9 (0.6) (N1=115) |

−9.5 (0.9) (N1=57) |

−2.4 (1.1) (−4.6 to −0.2)* |

| ∆SJC (SE) | −6.4 (0.5) (N1=123) |

−0.6 (0.7) (N1=60) |

−5.9 (0.9) (−7.5 to −4.2)*** |

−8.1 (0.4) (N1=115) |

−5.5 (0.5) (N1=57) |

−2.6 (0.7) (−3.9 to −1.3)** |

| ∆CGA (SE) | −29.5 (1.4) (N1=123) |

−11.0 (2.1) (N1=60) |

−18.4 (2.5) (−23.4 to −13.5)*** |

−38.8 (1.3) (N1=114) |

−31.1 (1.9) (N1=57) |

−7.7 (2.3) (−12.1 to −3.2)*** |

| ∆Pain (VAS) (SE) | −23.1 (1.7) (N1=127) |

−1.2 (2.5) (N1=62) |

−21.9 (3.0) (−27.8 to −15.9)*** |

−29.4 (1.7) (N1=124) |

−26.3 (2.4) (N1=59) |

−3.1 (3.0) (9.0 to 2.8) |

| ∆PtGA (SE) | −26.0 (1.8) (N1=127) |

−7.3 (2.6) (N1=62) |

−18.8 (3.2) (−25.1 to −12.5)*** |

−33.5 (1.7) (N1=124) |

−28.4 (2.4) (N1=59) |

−5.1 (2.9) (−10.9 to 0.6) |

| PsARC response, n (%) | 94 (69.1) | 20 (29.4) | 39.7 (6.8) (26.4 to 53.0)*** |

108 (79.4) | 43 (63.2) | 16.2 (6.8) (2.9 to 29.5)* |

| PGA-PsO response, n (%) (SE)‡‡ |

10 (9.4) (2.8) (N1=106) |

1 (2.0) (1.9) (N1=51) |

7.5 (3.4) (0.7 to 14.2)* |

11 (10.4) (3.0) (N1=106) |

11 (21.6) (5.8) (N1=51) |

−11.2 (6.5) (−23.9 to 1.5) |

| ∆PGA-PsO (SE) | −1.12 (0.1) (N1=119) |

−0.5 (0.1) (N1=58) |

−0.6 (0.1) (−0.9 to −0.3)*** |

−1.3 (0.1) (N1=112) |

−1.3 (0.1) (N1=54) |

0.0 (0.2) (−0.3 to 0.3) |

| PASI75, n (%) (SE)§§ | 27 (36.0) (5.5) (N1=75) |

3 (11.1) (6.1) (N1=27) |

24.9 (8.2) (8.8 to 41.0)** |

31 (41.3) (5.7) (N1=75) |

16 (59.3) (9.5) (N1=27) |

−17.9 (11.0) (−39.6 to 3.7) |

| Resolution of enthesitis, n (%) (SE)¶¶ |

35 (49.3) (5.9) (N1=71) |

7 (25.0) (8.2) (N1=28) |

24.3 (10.1) (4.5 to 44.1)* |

46 (64.8) (5.7) (N1=71) |

17 (60.7) (9.2) (N1=28) |

4.1 (10.8) (−17.2 to 25.3) |

| ∆LEI (SE) | −1.4 (0.2) (N1=63) |

−1.0 (0.3) (N1=24) |

−0.4 (0.3) (−1.0 to 0.2) |

−1.9 (0.1) (N1=59) |

−1.6 (0.2) (N1=23) |

−0.3 (0.2) (−0.7 to 0.2) |

| Resolution of dactylitis, n (%) (SE)††† | 42 (45.2) (5.2) (N1=93) |

8 (19.5) (6.2) (N1=41) |

25.7 (8.1) (9.9 to 41.4)** |

60 (64.5) (5.0) (N1=93) |

17 (41.5) (7.7) (N1=41) |

23.1 (9.2) (5.1 to 41.0)* |

| ∆DSS (SE) | −6.6 (0.5) (N1=86) |

−2.5 (0.8) (N1=37) |

−4.1 (1.0) (−6.0 to −2.1)*** |

−7.8 (0.2) (N1=79) |

−6.8 (0.3) (N1=34) |

−1.0 (0.3) (−1.7 to −0.3)** |

| ∆NAPSI (SE) | −1.0 (0.2) (N1=86) |

−0.8 (0.2) (N1=48) |

−0.2 (0.3) (−0.8 to 0.4) |

−2.4 (0.2) (N1=82) |

−2.1 (0.3) (N1=47) |

−0.3 (0.3) (−1.0 to 0.3) |

| ∆CRP mg/L (SE) | −9.8 (0.7) (N1=123) |

−2.0 (1.0) (N1=60) |

−7.8 (1.2) (−10.2 to −5.4)*** |

−10.2 (0.4) (N1=115) |

−9.0 (0.6) (N1=56) |

−1.3 (0.8) (−2.8 to 0.3) |

| ∆DAS28-3(CRP) (SE) | −1.3 (0.1) (N1=123) |

−0.3 (0.1) (N1=60) |

−1.0 (0.1) (−1.3 to −0.8)*** |

−1.9 (0.1) (N1=115) |

−1.6 (0.1) (N1=56) |

−0.2 (0.1) (−0.5 to 0.1) |

| ∆SF-36v2 PCS (SE) | 6.0 (0.6) (N1=125) |

1.9 (0.8) (N1=62) |

4.2 (1.0) (2.2 to 6.1)*** |

7.9 (0.6) (N1=126) |

7.6 (0.8) (N1=61) |

0.4 (1.0) (−1.6 to 2.4) |

| ∆SF-36v2 MCS (SE) | 3.4 (0.7) (N1=125) |

0.1 (1.0) (N1=62) |

3.3 (1.2) (0.8 to 5.7)** |

4.0 (0.8) (N1=126) |

2.2 (1.2) (N1=61) |

1.8 (1.4) (−1.0 to 4.6) |

| MDA, n (%) (SE)‡‡‡ | 44 (32.4) (4.0) | 4 (5.9) (2.9) |

26.5 (4.9) (16.8 to 36.1)*** |

67 (49.3) (4.3) | 25 (36.8) (5.9) | 12.5 (7.3) (-1.7 to 26.7) |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus placebo (to month 3) or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID (for remainder of study).

†All randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication.

‡For change from baseline endpoints, missing values were not imputed; for binary endpoints, missing values were considered as non-response.

§Primary endpoint.

¶Defined as a decrease in HAQ-DI from baseline ≥0.30 in patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥0.30.

††Identical results were observed for HAQ-DI response rate based on a decrease from baseline ≥0.35 in patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥0.35.

‡‡In patients with PGA-PsO ≥2 at baseline.

§§In patients with psoriatic BSA ≥3% and PASI>0 at baseline.

¶¶In patients with baseline LEI >0, with resolution of enthesitis defined as LEI=0.

†††In patients with baseline DSS >0, with resolution of dactylitis defined as DSS=0.

‡‡‡Defined as meeting ≥5 out of 7 items: ≤1 tender joint, ≤1 swollen joint, a PASI score of ≤1 or a BSA covered by psoriasis of ≤3%, pain VAS ≤15 mm, PtGA VAS ≤20 mm, HAQ-DI ≤0.5, and ≤1 tender enthesitis site (based on LEI).

∆, change from baseline; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; BID, twice daily; BSA, body surface area; CGA, Clinician's Global Assessment of arthritis; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28-3(CRP), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints with CRP; DSS, Dactylitis Severity Score; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MDA, minimal disease activity; N1, number of evaluable patients at each time point; n, number of patients with the specified characteristic; N, number of patients; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PGA-PsO, Physician’s Global Assessment of Psoriasis; PsARC, Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria; PtGA, Patient’s Global Assessment of arthritis; SE, standard error; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey, version 2 acute; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

In general, ACR50 response rates at month 3 were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo in a PsA subgroup analysis including sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, disease duration, previous DMARD exposure, CRP level, baseline PASI score and joint involvement (online supplemental figure 2).

Greater ACR20 response rates with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo occurred from week 2 (first postbaseline assessment; 22.8% vs 7.4%, respectively) to month 3. ACR70 response rates were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo at month 2 and month 3 (figure 2). From month 3 to month 6, ACR20 and ACR70 response rates continued to improve with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and increased in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group.

Greater proportions of patients achieved PASI75 responses with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at month 1 and month 3 versus placebo (figure 3; table 2). In patients with baseline enthesitis and dactylitis, resolution rates were higher at month 3 with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (figure 3; table 2).

Figure 3.

(A) PASI75 response rates†, (B) resolution rates of enthesitis‡, (C) resolution rates of dactylitis§, (D) change from baseline in HAQ-DI, (E) SF-36v2 PCS and (F) SF-36v2 MCS (full analysis set).¶†† The dotted line at/after month 3 indicates that patients in the placebo group were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg BID from month 3 for the remainder of the study. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus placebo (through month 3) or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg BID (for remainder of study). †Assessed in patients with baseline psoriatic BSA ≥3% and baseline PASI >0. ‡Assessed in patients with baseline LEI >0, with resolution of enthesitis defined as LEI=0. §Assessed in patients with baseline DSS >0, with resolution of dactylitis defined as DSS=0. ¶All randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication. ††For response outcomes, missing values were considered as non-response. For change from baseline, missing values were not imputed. ∆, change from baseline; BID, twice daily; BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; DSS, Dactylitis Severity Score; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; M, month; MCS, Mental Component Summary; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients assessed; N2, number of patients with observations at study visit; n, number of patients meeting response criteria; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBO, placebo; PCS, Physical Component Summary; SE, standard error; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey version 2 acute; W, week.

At month 3, LS mean reductions in HAQ-DI were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily than with placebo (LS mean difference −0.22; figure 3). HAQ-DI improvements occurred as early as week 2 through to month 3 with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo. The proportion of patients achieving HAQ-DI response (decrease from baseline ≥0.30 in patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥0.30) was greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at month 3 (65.1%) compared with placebo (41.0%; online supplemental figure 3). Identical results were achieved when HAQ-DI response was defined as a decrease from baseline ≥0.35 in patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥0.35 (table 2).

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily was also associated with improved Short Form-36 Health Survey, version 2 acute (SF-36 v2) Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores versus placebo at month 3; LS mean differences in change from baseline were 4.2 and 3.3, respectively (figure 3; table 2).

Efficacy was greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo at month 3 in other secondary endpoints, including change from baseline in PGA-PsO, tender joint counts, swollen joint counts and DAS28-3(CRP) scores (table 2). In a post hoc analysis, a greater proportion of patients met the criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA; see the online supplemental material) with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo at month 3 (32.4 and 5.9%, respectively). From month 3 to month 6, the proportions of patients who met MDA criteria increased in both the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily groups (49.3% and 36.8% at month 6, respectively) (online supplemental figure 4).

Safety

The frequency of AEs (all causality) was lower with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (68.4%) than with placebo (75.0%) from months 0 to 3 and from months 0 to 6 with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (81.6%) versus placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (88.2%). The incidence of serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation was lower with tofacitinib versus placebo from months 0 to 3 (table 3). From months 0 to 3, 55.1% and 13.2% of patients in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group, and 61.8% and 7.4% of patients in the placebo group reported mild and moderate AEs (all causality), respectively. No patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily reported severe AEs (an AE significantly interfering with a patient’s usual function) versus four patients receiving placebo.

Table 3.

Safety summary (safety analysis set*; all causality)

| Months 0–3 | Months 0–6 | |||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=136) | Placebo (N=68) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=136) | Placebo→ tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N=68) | |

| All treatment-emergent AEs | 93 (68.4) | 51 (75.0) | 111 (81.6) | 60 (88.2) |

| Serious AEs† | 0 | 3 (4.4) | 2 (1.5) | 5 (7.4) |

| Discontinued from study due to AEs | 3 (2.2)‡ | 6 (8.8)‡ | 4 (2.9)‡ | 6 (8.8)‡ |

| Death | 0 | 1 (1.5)§ | 0 | 1 (1.5)§ |

| AEs of special interest | ||||

| Serious infections¶ | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (5.9) |

| Herpes zoster (non-serious/serious) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7)** | 1 (1.5)** |

| Malignancies excluding NMSC†† | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7)‡‡ | 0 |

| NMSC†† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Opportunistic infections†† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MACE†† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GI perforations†† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thromboembolisms (DVT,†† PE,†† ATE) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic events | ||||

| Hy’s law case or DILI†† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most frequently reported treatment-emergent AEs (≥5% of patients in any treatment group), n (%) | ||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 25 (18.4) | 7 (10.3) | 36 (26.5) | 7 (10.3) |

| Blood CPK increased | 9 (6.6) | 1 (1.5) | 20 (14.7) | 2 (2.9) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 9 (6.6) | 2 (2.9) | 14 (10.3) | 6 (8.8) |

| Diarrhoea | 9 (6.6) | 2 (2.9) | 12 (8.8) | 2 (2.9) |

| Hepatic function abnormal | 5 (3.7) | 0 | 12 (8.8) | 3 (4.4) |

| ALT increased | 7 (5.1) | 4 (5.9) | 11 (8.1) | 5 (7.4) |

| AST increased | 6 (4.4) | 2 (2.9) | 11 (8.1) | 4 (5.9) |

| Cough | 6 (4.4) | 0 | 11 (8.1) | 0 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 9 (6.6) | 1 (1.5) | 9 (6.6) | 2 (2.9) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 9 (6.6) | 3 (4.4) |

| LDL cholesterol increased | 4 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | 8 (5.9) | 2 (2.9) |

| Dizziness | 7 (5.1) | 1 (1.5) | 7 (5.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Leucopenia | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.5) | 7 (5.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Blood triglycerides increased | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.9) | 5 (3.7) | 4 (5.9) |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (2.9) | 5 (7.4) |

| Red blood cell count decreased | 1 (0.7) | 3 (4.4) | 2 (1.5) | 4 (5.9) |

*All patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication.

†Serious AEs were defined as any untoward medical occurrence at any dose that resulted in death, were life-threatening (immediate risk of death), required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, resulted in congenital abnormality/birth defect or were considered to be important medical events.

‡All permanent discontinuations.

§One patient died due to an accident beyond 28 days after the last dose of study treatment; this was not considered treatment-related by the investigator (reported as a serious AE; counted under both month 3 and month 6 data). The exact date of the accident was unknown and therefore imputed as starting at day 1 and ending at day 264 (awareness date of patient death).

¶Up to month 6, the case in the tofacitinib group was upper respiratory tract infection, and the cases in the placebo group were two cases of bronchitis, one case of pneumonia, and one urinary tract infection.

**Non-serious.

††Adjudicated events.

‡‡Lung neoplasm malignant. The patient (male, aged 63 years) had a 40-year smoking history and a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, latent tuberculosis and a right lung nodule. The patient discontinued between month 4 and month 5 owing to rash. A bronchoscopy, conducted between months 6 and 7 due to respiratory symptoms, revealed the lung cancer, which was determined to be possibly related to blinded therapy by the investigator.

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ATE, arterial thromboembolism; BID, twice daily; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GI, gastrointestinal; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; N, number of evaluable patients; n, number of patients with event; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PE, pulmonary embolism.

The most frequently reported AE from months 0 to 3 was upper respiratory tract infection, followed by blood creatine phosphokinase increased, hyperlipidaemia, diarrhoea and abdominal discomfort. From months 0 to 6, the rates of the most frequently reported AEs were higher with tofacitinib versus placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (table 3).

One death was reported in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group owing to an accident that occurred beyond 28 days after the last dose of study treatment; this event was not considered by the investigator to be treatment related. From months 0 to 6, one serious infection event (upper respiratory tract infection) was reported in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group versus four events in the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group (bronchitis [two cases], pneumonia [one case] and urinary tract infection [one case]. Two non-serious cases of herpes zoster (one in each treatment group) were reported. One patient (male, aged 63 years, with a 40-year smoking history and a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) had an adjudicated malignancy (invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the lung that was determined to be possibly related to blinded therapy by the investigator) in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group.

No adjudicated non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), opportunistic infections, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), gastrointestinal perforations, thromboembolism or drug-induced liver injuries were reported in either treatment group (table 3). Considering laboratory values and clinical laboratory abnormalities (online supplemental figure 5; online supplemental tables 1 and 2), in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group, absolute lymphocyte counts transiently increased, followed by a decrease that plateaued at month 3. In addition, absolute neutrophil counts decreased and haemoglobin, creatinine, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol increased with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily compared with placebo to month 3; levels remained relatively stable after month 3 (online supplemental figure 5). Alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels increased to month 3 with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo; numerical reductions in levels from month 3 were observed (online supplemental figure 5). Elevations in bilirubin and transaminase levels are shown in online supplemental table 2. Similar changes from baseline in laboratory parameters were generally observed to those noted with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at subsequent time points after patients receiving placebo switched to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at month 3 (online supplemental figure 5). One patient from the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group had a platelet count <100×109/L. Throughout the study, no patients had absolute lymphocyte or neutrophil counts meeting criteria for monitoring or discontinuation (online supplemental table 1).

Discussion

In this first phase 3 study of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with active PsA and an inadequate response to csDMARDs, tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily demonstrated a significantly greater efficacy than placebo for the primary endpoint, ACR50 response rate at month 3 (38.2% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 5.9% with placebo; p<0.0001).

The improvements in ACR50 response rates in this study in Chinese patients are numerically greater than the findings of the Phase 3 OPAL Broaden (ACR50 response rates: 28%, tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily; 10%, placebo; p<0.001) and OPAL Beyond (30% and 15%, respectively; p<0.05) studies in global populations of patients with active PsA.13 14 Similarly, higher ACR20 response rates at month 6 were seen in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), compared with the global tofacitinib RA studies.16 However, this nuance may be accounted for by differences in baseline patient demographics.16

Compared with OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond, patients in this study had a shorter mean duration of disease, lower mean tender/painful joints and mean swollen joint counts at baseline, lower baseline HAQ-DI scores and, versus OPAL Broaden only, higher median PASI scores. Baseline characteristics in this study in Chinese patients are also generally consistent with the clinical features of Chinese patients with PsA reported in a cross-sectional observational study,17 with the exception of baseline dactylitis levels, which were higher in this study. Furthermore, in this study, the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group contained more patients with prior bDMARD use and higher rates of dactylitis and enthesitis at baseline than the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group. The imbalance between the groups was considered a chance occurrence, given that this was a randomised, double-blind study, and as this was previously observed in the global phase 3 studies.13 14 Notably, more prior bDMARD use in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group in this study may have been a disadvantage, given the well-described trend of reduced response in treatment refractory patients.18 19 Furthermore, the higher proportion of patients with enthesitis (and dactylitis) at baseline in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group compared with the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group may have presented a disadvantage for MDA attainment, as patients without enthesitis at baseline would have been more likely to achieve the MDA component threshold. The higher proportion of patients with enthesitis and dactylitis at baseline in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group is unlikely to have impacted greatly the proportion of patients achieving enthesitis and dactylitis resolution, as these measures were restricted to patients with LEI >0 and DSS >0 at baseline, respectively.

Although the time frame of the study included the global COVID-19 pandemic, results of a supporting analysis for ACR50 at month 3 that excluded patients impacted by COVID-19 were similar to the overall ACR50 findings. Moreover, ACR50 response rates at month 3 were generally in favour of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo for a range of baseline characteristics examined. This is similar to findings from previous post hoc analyses of the global clinical trial programme in PsA, in which clinical improvements with tofacitinib treatment were generally observed when factors such as BMI,20 severity of skin symptoms,21 sex,22 methotrexate dose,23 bDMARD exposure14 and time since first PsA diagnosis24 were examined.

In this study, the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily was greater than placebo across a range of secondary efficacy outcomes, including ACR20, ACR70 and PASI75 response, rates of enthesitis or dactylitis resolution and change from baseline in HAQ-DI at month 3, with improvements generally maintained or continuing to month 6. The improvement in these secondary endpoints was of similar or greater magnitude to improvements reported for tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo in the phase 3 global studies,13 14 although differences in patient populations at baseline between these studies and the current study should be noted. As well as improvements in efficacy outcomes, tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily was associated with greater improvements in SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores versus placebo at month 3. The improvements presented here were generally greater than the results shown in OPAL Broaden and OPAL Beyond studies.25 26

The safety of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with PsA was consistent with the established safety profile of tofacitinib in patients with PsA13–15 27 and in other indications, including RA.27–37 The most frequently reported AE was upper respiratory tract infection, and up to month 6, the incidence of AEs of special interest was ≤6% for serious infections, ≤1.5% for herpes zoster and ≤0.7% for malignancies excluding NMSC. No adjudicated NMSC, opportunistic infections, MACE, gastrointestinal perforations, thromboembolism or drug-induced liver injury events were reported.

The limitations of this study include the study duration (6 months) that prevents conclusions on the long-term effectiveness and assessment of long-latency safety events (eg, MACE and malignancy) of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with PsA. As with all randomised controlled trials, the patient eligibility criteria may not be truly reflective of the real-world Chinese PsA population, and results presented herein may not be representative of expected responses to tofacitinib in other global regions. No radiographical data were collected during the study; thus, the impact of tofacitinib on structural changes could not be evaluated. In addition, some assessments used in this study, such as questions related to bathtub use in HAQ-DI, may not be entirely applicable to the lifestyle of the Chinese population. Finally, the numbers of patients included at some time points for some outcome measures and in the subgroup analyses were low and limit the interpretation of these data.

In conclusion, the results from this first study of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with polyarthritic PsA demonstrate that tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily has a significantly greater efficacy versus placebo for the primary endpoint of ACR50 response rate at month 3. Greater efficacy (vs placebo) was observed for secondary endpoints evaluated at month 3, including PASI75, rates of enthesitis or dactylitis resolution and HAQ-DI. Tofacitinib was well tolerated, and the safety findings were consistent with the established safety profile of tofacitinib in the global clinical trial programme in PsA, as well as the overall tofacitinib clinical programme in other indications. Tofacitinib has demonstrated a favourable benefit/risk profile in Chinese patients with PsA and could potentially address the unmet need for new advanced PsA treatments in China.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Louise Brown, BSc (Hons), CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications, and Karleen Nicholson, PhD, on behalf of CMC Connect, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022; 175: 1298-304).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have met the following International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria. All authors had access to the data, were involved in interpretation of data, reviewed and approved the manuscript’s content before submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Study conception and design: XZ, XL, WL, CW; acquisition of data: XZ, XL, WW, ZJ, YL, SL, ZhuZ, ZhiZ, JX, WT, JH, JiL, JuL; analysis of data: XL, WL, SL, CW. The study sponsor, Pfizer Inc, was involved in the conception of the study, as well as the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. XZ is the guarantor for this study.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Pfizer.

Competing interests: XZ, XL, WW, ZJ, YL, SL, ZhuZ, ZhiZ, JX, WT, JH, JiL and JuL declare no conflicts of interests. WL is a former employee of Pfizer Inc. SL, KK, CW, LMG, CK and OD are current employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the general principles in the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, International Council for Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written, informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Peking Union Medical College Hospital (ID: KS2018070).

References

- 1.Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Psoriatic arthritis: state of the art review. Clin Med 2017;17:65–70. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-1-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:957–70. 10.1056/NEJMra1505557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudu T, Gossec L. Quality of life in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018;14:405–17. 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1468252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Q, Qu L, Tian H, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of psoriatic arthritis in Chinese patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:1409–14. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.03985.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei JC-C, Shi L-H, Huang J-Y, et al. Epidemiology and medication pattern change of psoriatic diseases in Taiwan from 2000 to 2013: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. J Rheumatol 2018;45:385–92. 10.3899/jrheum.170516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra A, Lin H-Y, Navarra SV, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis management in the APLAR region: perspectives from an expert panel of rheumatologists, patients and community oriented program for control of rheumatic diseases. Int J Rheum Dis 2021;24:1106–11. 10.1111/1756-185X.14185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahiri M, Santosa A, Teoh LK, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicines is associated with delay to initiation of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapy in early inflammatory arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 2017;20:567–75. 10.1111/1756-185X.13091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700–12. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates LC, Soriano E, Corp N, et al. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) treatment recommendations 2021. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:139–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.4091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, et al. Special article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National psoriasis Foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:2–29. 10.1002/acr.23789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rheumatology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association . Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Chin J Rheumatol 2010;14:631–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai T-F, Hsieh T-Y, Chi C-C, et al. Recommendations for psoriatic arthritis management: a joint position paper of the Taiwan Rheumatology Association and the Taiwanese Association for Psoriasis and Skin Immunology. J Formos Med Assoc 2021;120:926–38. 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1525–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nash P, Coates LC, Fleishaker D, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib up to 48 months in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: final analysis of the OPAL Balance long-term extension study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021;3:e270–83. 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00010-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z-G, Liu Y, Xu H-J, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Chin Med J 2018;131:2683–92. 10.4103/0366-6999.245157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Z, Li B, Zhang Z. AB0384 clinical characteristics of ARTHRITIS IN CHINESE PATIENTS: A cross-sectional observational study [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1721–2. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.5921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, et al. Clinical response, drug survival, and predictors thereof among 548 patients with psoriatic arthritis who switched tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish Nationwide DANBIO Registry. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1213–23. 10.1002/art.37876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy SM, Crean S, Martin AL, et al. Real-world effectiveness of anti-TNF switching in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:2955–66. 10.1007/s10067-016-3425-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giles JT, Ogdie A, Gomez Reino JJ, et al. Impact of baseline body mass index on the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open 2021;7:e001486. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merola JF, Papp KA, Nash P, et al. Tofacitinib in psoriatic arthritis patients: skin signs and symptoms and health-related quality of life from two randomized phase 3 studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:2809–20. 10.1111/jdv.16433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eder L, Gladman D, Zehra Aydin S. Evaluation of sex differences in the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 randomized controlled trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:0377. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kivitz AJ, FitzGerald O, Nash P, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib by background methotrexate dose in psoriatic arthritis: post hoc exploratory analysis from two phase III trials. Clin Rheumatol 2022;41:499–511. 10.1007/s10067-021-05894-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nash P, Greenwald M, Lin L-H. The impact of time since first diagnosis on the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with active psoriatic arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1484. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strand V, de Vlam K, Covarrubias-Cobos JA, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo: patient-reported outcomes from OPAL Broaden-a phase III study of active psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. RMD Open 2019;5:e000806. 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strand V, de Vlam K, Covarrubias-Cobos JA, et al. Effect of tofacitinib on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in the phase III, randomised controlled trial: OPAL Beyond. RMD Open 2019;5:e000808. 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burmester GR, Nash P, Sands BE, et al. Adverse events of special interest in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis with 37 066 patient-years of tofacitinib exposure. RMD Open 2021;7:e001595. 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61424-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:495–507. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kremer J, Li Z-G, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:253–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2377–86. 10.1056/NEJMoa1310476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Heijde D, Tanaka Y, Fleischmann R, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve-month data from a twenty-four-month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:559–70. 10.1002/art.37816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:508–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Hall S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy, tofacitinib with methotrexate, and adalimumab with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ORAL Strategy): a phase 3b/4, double-blind, head-to-head, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;390:457–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31618-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open-label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol 2014;41:837–52. 10.3899/jrheum.130683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamanaka H, Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral janus kinase inhibitor, as monotherapy or with background methotrexate, in japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label, long-term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:34. 10.1186/s13075-016-0932-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wollenhaupt J, Lee E-B, Curtis JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for up to 9.5 years in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: final results of a global, open-label, long-term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:89. 10.1186/s13075-019-1866-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2022-002559supp001.pdf (729.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.