Abstract

Objective:

A growing and increasingly vulnerable population resides in assisted living. States are responsible for regulating assisted living and vary in their requirements. Little is known about how this variability translates to differences in the dying experiences of assisted living residents. The objective of this study is to describe assisted living residents’ end-of-life care trajectories and how they vary by state.

Design:

Observational retrospective cohort study

Setting and Participants:

Using Medicare data and a methodology developed to identify beneficiaries residing in large assisted living communities (25+ beds), we identified a cohort of 40,359 assisted living residents in the continental US enrolled in traditional Medicare and who died in 2016.

Methods:

We used Medicare data and the Residential History File to examine assisted living residents’ location of care and services received in the last 30 days of life.

Results:

Nationally, 57% of our cohort died outside of an institutional setting, i.e., hospital or nursing home, (n=23,165), 18,396 of whom received hospice at the time of death. Rates of hospitalization and transition to a nursing home increased over the last 30 days of life. We observed significant inter-state variability in the adjusted number of days spent in assisted living in the month before death (from 13.6 days (95% CI: 11.8, 15.4) in North Dakota to 24.0 days (95% CI: 22.7, 25.2) in Utah) and wider variation in the adjusted number of days receiving hospice in the last month of life, ranging from 2.1 days (95% CI: 1.0, 3.2) in North Dakota to 13.8 days (95% CI: 12.1, 15.5) in Utah.

Conclusions and Implications:

Findings suggest that assisted living residents’ dying trajectories vary significantly by state. To ensure optimal end-of-life outcomes for assisted living residents, state policymakers should consider how their regulations influence end of life care in assisted living, and future research should examine factors (e.g., state regulations, market characteristics, provider characteristics) that may enable assisted living residents to die in place and contribute to differential access to hospice services.

Keywords: End of Life, assisted living, policy

Brief Summary:

This retrospective observational study using 2016 Medicare claims data suggests that assisted living residents’ places of death and services received in the last month of life vary significantly by state.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), assisted living communities provide health oversight, nursing, and personal care services to a growing and increasingly vulnerable population, 71% of whom have cognitive impairment.1 In 2016 there were an estimated 811,500 residents in 28,900 assisted living settings in the US.2 States are responsible for regulating and monitoring these settings and vary greatly in terms of their requirements for assisted living,3,4 including the provision of third-party services, such as hospice care. Hospice services delivered in assisted living might extend a resident’s tenure, as well as provide needed medical oversight and end-of-life care. However, these services might not be available, and some states’ regulations require discharge when a resident’s condition exceeds a certain level of care.

Previous research suggests that a variety of factors are attributable to differences in assisted living residents’ end-of-life experiences, including staff training,5 provider attitudes6 and policies, availability of hospice care,6 and residents’ characteristics, beliefs, values, and resources.7 However, these studies are limited to surveys with small samples of assisted living communities or interviews with assisted living residents, staff, and administrators. As such, there is limited information about state variability in dying experiences among assisted living residents.

Nationally, much of what we know about end-of-life care in assisted living relates to the use of hospice services by current assisted living residents. A recent study using national Medicare hospice claims found that receipt of hospice services in assisted living is becoming more common: between 2009 and 2015, a growing proportion of all Medicare beneficiaries who received hospice services and were classified as dying in the community, died in assisted living.8 In 2015, almost one-fifth (18.4% (95% CI, 18.1%−18.6%)) of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries dying in the community resided in assisted living at the time of death.8 Synonymous with these increases, Medicare payments for hospice care in assisted living more than doubled between 2007 and 2012.9 Over time, there has also been an increase in the share of hospice deaths in the US with a principal diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia (ADRD): the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization reports that in 2016, 18% of all hospice deaths had a principal diagnosis of dementia, up from 15.2% in 2013. Despite the attention to the growth in hospice care provided in assisted living and the large share of assisted living residents with cognitive impairment, we do not have insight into assisted living residents’ end-of-life experiences nationally, including what proportion of all assisted living residents are able to die in place and receive hospice services at the end of life, nor how these outcomes vary across the US and for the subgroup of residents with ADRD. Therefore, the objective of this study is to examine assisted living residents’ end-of-life care trajectories and how they vary by state.

METHODS

Data

Medicare beneficiaries’ enrollment, healthcare utilization, chronic conditions, as well as geographic and demographic data (including dates of death) were drawn from the 2015 and 2016 Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF). To characterize patients’ utilization and locations of care in the last 30 days before death, we used the 2015 and 2016 hospice, Skilled Nursing Facility, and inpatient claims, as well as nursing home Minimum Data Set (MDS). Data on assisted living communities were compiled from a national census collected by the authors in 2014.10

Sample Selection

We identified all Medicare beneficiaries, age 65 years or older, who resided in an assisted living community with 25+ beds in the continental U.S. on December 31, 2015 according to their 9-digit ZIP codes reported in the MBSF and died between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2016 (n=55,970, 8% of the assisted living sample). The 9-digit ZIP codes belonging to assisted living communities were identified using a methodology that combines the home health OASIS assessment data, Part B Medicare claims, and a national census of licensed, large (25+ beds) assisted living communities11. We excluded decedents enrolled in Medicare Advantage in the month of their death (n=15,611; 28% of decedents in our sample) because inpatient and skilled nursing facility claims data are not available for Medicare Advantage enrollees. This yielded a final analytic sample of 40,359 decedents.

Outcome

The Residential History File algorithm was used to characterize assisted living decedents’ care trajectories in the last 30 days of life.12 The Residential History File tracks beneficiaries across the healthcare system by place and time using the dates of service on Medicare claims and MDS assessments, including enrollment in hospice, and dates of death from the MBSF.

Analysis

We first examined the demographic characteristics and comorbidities of Medicare decedents who resided in assisted living communities, by place of death (considered in assisted living if neither hospitalized nor admitted to nursing home, as indicated in the Residential History File). We used chi-squared tests to examine differences in resident characteristics, by place of death. We also plotted the location of care and hospice services, of any level (i.e., routine home care, continuous home care, general inpatient care, respite care) received in the last 30 days of life in the general population of assisted living residents and for a subgroup of residents with ADRD diagnoses (n=25,780). We then examined the number of days spent in assisted living and the number of days receiving hospice while an assisted living resident in the last 30 days of life, by state. Multivariate regression models were used to adjust for decedents’ age, sex, race, dual eligibility for Medicaid, and diagnosis of a life-limiting illness (i.e., Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, Cancer, Chronic Kidney Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Diabetes, Heart Failure, Stroke/TIA). All analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp 2017). Additional information about the data and methods used for these analyses can be found in the Brown University Digital Repository (https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:924750/).

RESULTS

Nationally, 57% of our analytical cohort of assisted living residents who died in 2016 died outside of an institutional setting, i.e., hospital or nursing home (n=23,165). Moreover, 18,396 of the assisted living residents in the cohort received hospice at the time of their death (Table 1). A total of 10,752 were transferred to a nursing home prior to death, approximately 60% of whom (n=6,406) received hospice at the time of death. In 2016, 16% of our cohort (n=6,442) were in an acute hospital at the time of death. Resident characteristics varied significantly by place of death: residents who received hospice before dying, either in assisted living or after being transferred to a nursing home, were older than those who died without hospice services. A larger share of assisted living residents who died in a nursing home or inpatient hospital were dual eligible compared to residents who died in assisted living. In addition, a smaller proportion of assisted living residents receiving hospice were dual eligible compared to decedents who remained in assisted living without hospice. Compared to decedents who remained in assisted living or died in a nursing home, a higher percentage of assisted living residents who died in a hospital had life-limiting diagnoses (i.e., Cancer, Chronic Kidney Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Diabetes, Heart Failure, and Stroke/TIA) with the exception of ADRD, which was most common among those dying in a nursing home.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Assisted Living Residents who Died in 2016, by Place of Death

| Died in Assisted Living with Hospice | Died in Assisted Living w/out Hospice | Died in Nursing Home with Hospice | Died in Nursing Home w/out Hospice | Died in Hospital | All Decedents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=18,396 (45.6%) | n=4,769 (11.8%) | n=6,406 (15.9%) | n=4,346 (10.8%) | n=6,442 (16.0%) | n=40,359 (100%) | |

| Age Groups, n (%) | ||||||

| 65–74 | 774 (4.2) | 582 (12.2) | 313 (4.9) | 261 (6.0) | 652 (10.1) | 2,582 (6.4) |

| 75–84 | 3,024 (16.4) | 909 (19.1) | 1,081 (16.9) | 762 (17.5) | 1,495 (23.2) | 7,271 (18.0) |

| 85+ | 14,598 (79.4) | 3,278 (68.7) | 5,012 (78.2) | 3,323 (76.5) | 4,295 (66.7) | 30,506 (75.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 6,258 (34.0) | 2,062 (43.2) | 2,278 (35.6) | 1,643 (37.8) | 2,538 (39.4) | 14,779 (36.6) |

| Female | 12,138 (66.0) | 2,707 (56.8) | 4,128 (64.4) | 2,703 (62.2) | 3,904 (60.6) | 25,580 (63.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 17,654 (96.0) | 4,437 (93.0) | 6,128 (95.7) | 4,088 (94.1) | 6,011 (93.3) | 38,318 (94.9) |

| Black | 323 (1.8) | 158 (3.3) | 132 (2.1) | 118 (2.7) | 201 (3.1) | 932 (2.3) |

| Hispanic | 220 (1.2) | 87 (1.8) | 78 (1.2) | 74 (1.7) | 126 (2.0) | 585 (1.5) |

| Other | 199 (1.1) | 87 (1.8) | 68 (1.1) | 66 (1.5) | 104 (1.6) | 524 (1.3) |

| Entitlement Characteristics, n (%) | ||||||

| Dually Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid at the time of death | 1,769 (9.6) | 611 (12.8) | 1,545 (24.1) | 1,172 (27.0) | 1,106 (17.2) | 6,203 (15.4) |

| Chronic Conditions, n (%) | ||||||

| Alzheimer’s/Related or Senile Dementia | 12,190 (66.3) | 2,345 (49.2) | 4,558 (71.2) | 3,080 (70.9) | 3,607 (56.0) | 25,780 (63.9) |

| Cancer | 2,822 (15.3) | 419 (8.8) | 1,084 (16.9) | 682 (15.7) | 1,217 (18.9) | 6,224 (15.4) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 9,394 (51.1) | 2,088 (43.8) | 3,617 (56.5) | 2,597 (59.8) | 4,708 (73.1) | 22,404 (55.5) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 4,225 (23.0) | 1,019 (21.4) | 1,638 (25.6) | 1,267 (29.2) | 2,492 (38.7) | 10,641 (26.4) |

| Diabetes | 5,115 (27.8) | 1,448 (30.4) | 2,009 (31.4) | 1,542 (35.5) | 2,471 (38.4) | 12,585 (31.2) |

| Heart Failure | 9,403 (51.1) | 2,178 (45.7) | 3,560 (55.6) | 2,610 (60.1) | 4,337 (67.3) | 22,088 (54.7) |

| Stroke/TIA | 1,897 (10.3) | 269 (5.6) | 837 (13.1) | 553 (12.7) | 1,032 (16.0) | 4,588 (114) |

| 2+ Chronic Conditions | 13,351 (72.6) | 2,902 (60.9) | 5,148 (80.4) | 3,595 (82.7) | 5,688 (88.3) | 30,684 (76.0) |

| 4+ Chronic Conditions | 4,114 (22.4) | 791 (16.6) | 1,763 (27.5) | 1,389 (32.0) | 2,434 (37.8) | 10,491 (26.0) |

Notes. Dual eligibility represents Medicare and Medicaid eligible in the month of death. Cancer includes a diagnosis of breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, lung cancer or prostate cancer. 2+ and 4+ Chronic conditions is out of the following seven: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and stroke. Chi-squared tests indicate that decedent characteristics differ significantly (p<.001) across categories of place of death.

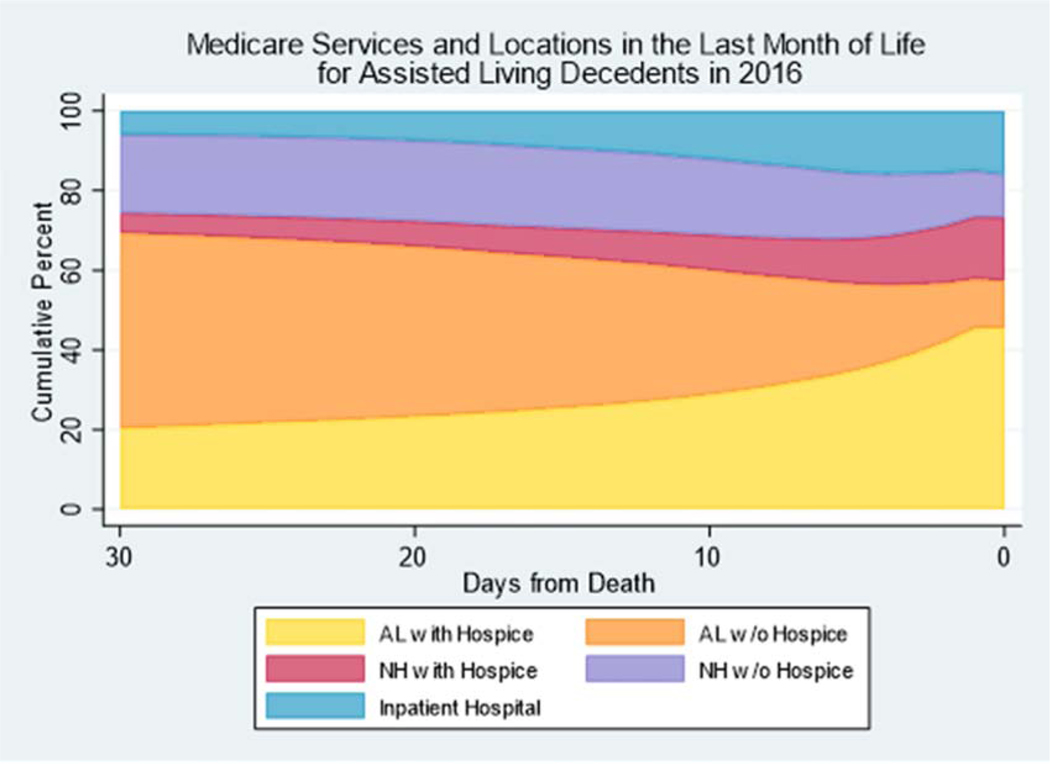

Nationally, the share of our analytical cohort who elected hospice while an assisted living resident increased from 20% at 30 days prior to death to 46% at the time of death. As can be seen in Figure 1, rates of hospitalization and transition to a nursing home also increased over the last 30 days of life: the share of our cohort who were hospitalized rose from 6% to 16% and the share who transitioned to a nursing home rose from 25% to 27% during the last 30 days of life. The patterns observed for the sub-sample with ADRD tracked similarly to the overall cohort (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 1.

Medicare Services and Locations in the Last Month of Life for Assisted Living Residents who Died in 2016 (n=40,359)

Note. AL = Assisted Living; NH=Nursing Home

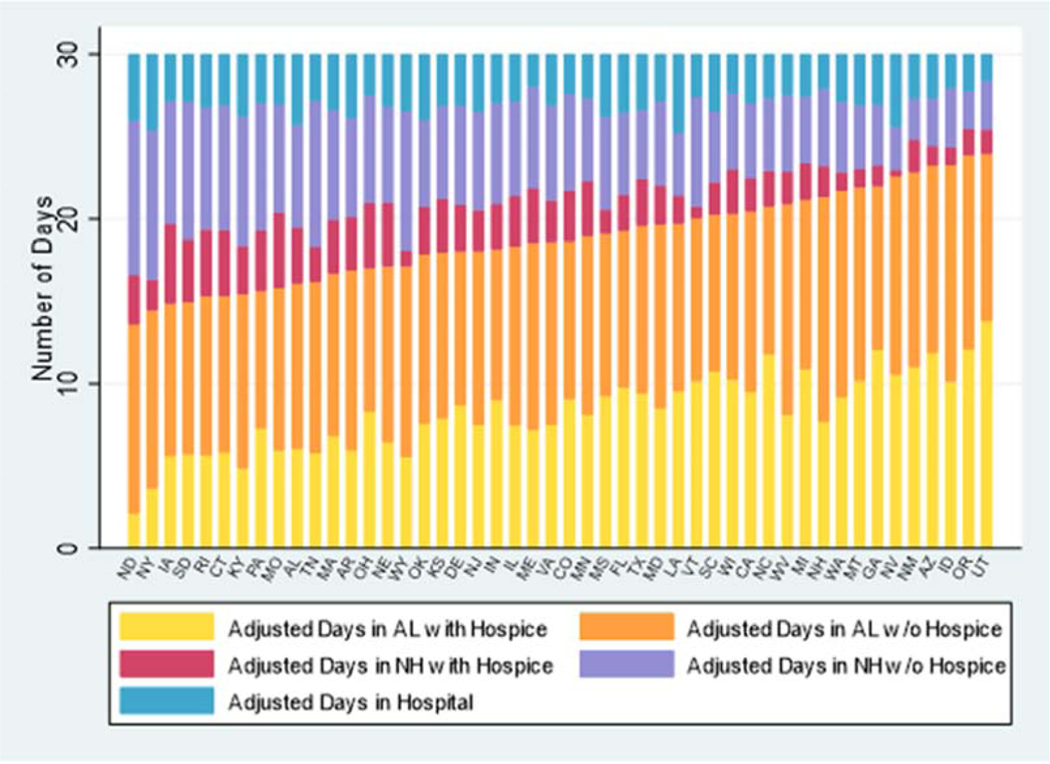

We observed significant inter-state variability in the number of days spent in assisted living in the month before death, ranging from 24 days in Utah (95% CI: 22.7–25.2), to fewer than 14 days in North Dakota (95% CI: 11.8–15.4) (Figure 2 and eTable1 in the Supplement). We observed even wider variation in the number of days receiving hospice care while an assisted living resident in the last month of life, ranging from 13+ days in Utah (95% CI: 12.1–15.5), to <3 days in North Dakota (95% CI: 1.0–3.2).

Figure 2.

State Variability in the Adjusted Number of Days in Various Locations in the Last Month of Life

Notes. AL = Assisted Living; NH=Nursing Home

Days adjusted for age, sex, race, dual-eligibility, and life-limiting illnesses;

States are presented in the order of least days in assisted living in the last month of life to most days in assisted living in the last month of life.

DISCUSSION

This is the first national study to examine dying trajectories in a cohort of residents in large assisted living communities. Our results suggest that while many assisted living residents transfer to a nursing home prior to death, the majority remain in assisted living and over three-quarters of these decedents receive hospice care at the end of life. We observed important state variation in the number of days spent in assisted living in the last month of life and the number of days in which dying assisted living residents received hospice.

The observation that the majority of assisted living decedents died outside of a nursing home or hospital is noteworthy for several reasons. First, it provides further evidence to support the observation that assisted living communities serve an increasingly frail population.13 Second, the large number of assisted living residents who are not transferred to a nursing home or acute hospital during the last month of life might avoid complications associated with late transitions,14,15 and potentially receive care that is concordant with their preferences. Third, among those who died in assisted living, over three quarters received some form of hospice at the time of death. In sum, the share of assisted living residents who age in place until death, the majority of whom receive hospice, could be viewed as a positive finding in light of increasing evidence that this may be in line with residents’ preferences,6 although, we cannot draw conclusions about the quality of end-of-life care received in assisted living.

Our findings suggest that dying trajectories among assisted living residents vary significantly by state. It may be the case that differences in regulations pertaining to use of third-party services, delivery of pain medications, level of care permitted, dementia-specific provisions, and availability of nursing staff may be driving assisted living residents’ healthcare utilization at the end of life and accounting for differences observed between states. For example, Utah, the state with the largest number of days in assisted living with hospice in the last month of life, allows assisted living communities to admit and retain residents receiving hospice services. North Dakota, the state with the fewest days spent in assisted living or on hospice among all assisted living decedents, has extensive requirements for end-of-life care services. For example, the assisted living must be certified for end-of-life care and the resident must elect to receive this care from a licensed and Medicare-certified hospice agency. If the resident is not capable of self-preservation during an emergency, the assisted living community must inform the licensing agency and comply with National Fire Protection Association building requirements. Additional work is needed to understand how state regulations and/or local variations in hospice practice patterns16 may enable or prevent dying assisted living residents from receiving care that is in-line with their preferences.

Our findings suggest that residents who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid are more likely to die in nursing homes or acute care hospitals than non-dual eligible beneficiaries. The move to a nursing home at the end of life may be due, in part, to “spend down” while in assisted living and inability to pay.17 Possibly, assisted living communities that accept and retain dual eligible residents may be concentrated in states with different regulations pertaining to the level of care provided in assisted living communities, or these providers may have different resources to provide needed services for individuals with increasing needs at the end of life. Among those dying in assisted living, dual eligible residents are less likely to receive hospice at the time of death. This difference has not been observed in the nursing home setting.18 Future work is needed to understand the mechanisms behind the variation in end-of-life experiences of dual eligible residents in assisted living.

Limitations of our study include only examining assisted living communities with 25+ beds. As such, our findings may not be generalizable to small assisted living communities.19 While large assisted living communities made up approximately 39.2% of assisted living communities in 2016, they comprised 84.1% of all licensed beds, nationally.2 Given our reliance on updating ZIP codes to reflect residence in assisted living, we are only able to examine a cohort of residents in large assisted living communities who changed their ZIP code to reflect residence in these settings. Furthermore, we may be including beneficiaries who reside in other setting types, such as independent living, that are co-located with a licensed assisted living community and, therefore, share a 9-digit ZIP code. In addition, we are unable to observe the end-of-life care trajectories of the large and growing population of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries20 or assisted living residents who are not enrolled in Medicare and whose presence in assisted living varies across the country.21 Because of our reliance on administrative data, we describe utilization as opposed to patients’ preferences or quality of care. In addition, ADRD is underdiagnosed and varies by state,22,23 limiting our understanding of end-of-life care for persons with dementia. Finally, we do not examine variation in hospice practice patterns or local market factors (e.g., availability of nursing home and inpatient beds), which may impact our results.24,25 For example, hospices may concentrate on serving residents in nursing homes or assisted living and this behavior may vary by state.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

In conclusion, this study provides insight into the dying trajectories of assisted living residents and reveals important variation in the ability for dying assisted living residents to age and die in place across the country. These results have important implications for policy and practice. For example, states with lower rates of residents dying in assisted living may want to examine their regulations to determine if they restrict residents’ ability die in place. In addition, palliative care training for assisted living administrators and staff, particularly in states where utilization of hospice in assisted living is lower, may be one way to ensure high quality end-of-life care in assisted living. Future research is needed to better understand the factors (e.g., state regulations, market characteristics, provider characteristics, consumer preferences) that may be attributable to differences observed in this study and to examine whether assisted living residents have access to high-quality end-of-life care in line with their care preferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by research awards from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG057746 to KST) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (CDA14-422 to KST).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kali S. Thomas, Brown University School of Public Health, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Providence, RI.

Emmanuelle Belanger, Brown University School of Public Health.

Wenhan Zhang, Brown University School of Public Health, Paula Carder PhD Portland State University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed D. Dementia Prevalence and Care In Assisted Living. Health Aff 2014;33(4):658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. Long-term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2015–2016 Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_43-508.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 3.Carder PC, O’Keeffe J. Compendium of Residential Care and Assisted Living Regulations and Policy: 2015 ed. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/compendium-residential-care-and-assisted-living-regulations-and-policy-2015-edition. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 4.Carder PC. State Regulatory Approaches for Dementia Care in Residential Care and Assisted Living. Gerontologist. 2017;57(4):776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbs DJ, Hanson L, Zimmerman S, et al. Hospice Attitudes Among Assisted Living and Nursing Home Administrators, and the Long-Term Care Hospice Attitudes Scale. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1388–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cartwright JC, Miller L, Volpin M. Hospice in Assisted Living: Promoting Good Quality Care at End of Life. Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):508–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball MM, Kemp CL, Hollingsworth C, Perkins MM. “This is our last stop”: Negotiating End-of-Life Transitions in Assisted Living. J Aging Stud. 2014;30:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. Site of Death, Place of Care, and Health Care Transitions Among US Medicare Beneficiaries, 2000–2015. JAMA. 2018;320(3):264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.OIG Report. Medicare Hospices have Financial Incentives to Provide Care in Assisted Living Facilities. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-14-00070.asp. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 10.Silver BC, Grabowski DC, Gozalo PL, et al. Increasing Prevalence of Assisted Living as a Substitute for Private-Pay Long-Term Nursing Care. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4906–4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Gozalo PL, et al. A Methodology to Identify a Cohort of Medicare Beneficiaries Residing in Large Assisted Living Facilities Using Administrative Data. Med Care. 2018. Feb;56(2):e10–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, et al. The Residential History File: Studying Nursing Home Residents’ Long-Term Care Histories. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1 Pt 1):120–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowblis JR. Market Structure, Competition from Assisted Living Facilities, and Quality in the Nursing Home Industry. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2012;34(2):238–257. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen J, Hutchinson AM, Brown R, Livingston PM. Quality Care Outcomes Following Transitional Care Interventions for Older People from Hospital to Home: a Systematic Review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman EA, Boult C. Improving the Quality of Transitional Care for Persons with Complex Care Needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(4):556–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden TR, Smith MA, Bartels CM, et al. Hospice Enrollment, Local Hospice Utilization Patterns, and Rehospitalization in Medicare Patients. J of Palliat Med. 2015;18(7):601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiener JM, Anderson WL, Khatutsky G, et al. Medicaid Spend Down: New Estimates and Implications for Long-Term Services and Supports Financing Reform. http://www.thescanfoundation.org/sites/default/files/tsf_ltc-financing_medicaid-spend-down-implications_wiener-tumlinson_3-20-13.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 18.Unroe KT, Sachs GA, Dennis ME, et al. Impact of Hospice Use on Costs for Long Stay Nursing Home Decedents. J of Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4): 723–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washington KT, Demiris G, Oliver DP, et al. Quality Hospice Care in Adult Family Homes: Barriers and Facilitators. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19(2):136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage Checkup. N Engl J Med 2018;379(22):2163–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caffrey C, Sengupta M. Variation in residential care community resident characteristics, by size of community: United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 299. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsltcp/State_estimates_for_NCHS_Data_Brief_299.pdf [PubMed]

- 22.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, et al. Missed and Delayed Diagnosis of Dementia in Primary Care: Prevalence and Contributing Factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23(4):306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russ TC, Batty GD, Hearnshaw GF, et al. Geographical Variation in Dementia: Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):1012–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, et al. Associations among Hospital Capacity, Utilization, and Mortality of US Medicare Beneficiaries, Controlling for Sociodemographic Factors. Hum Serv Res. 2000;34(6): 1351–1362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson DG, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC, Keating NL. Differences in hospice care between home and institutional settings. J Palliat Med. 2007. Oct;10(5):1040–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.