Abstract

Background

Cognitive stimulation (CS) is an intervention for people with dementia offering a range of enjoyable activities providing general stimulation for thinking, concentration and memory, usually in a social setting, such as a small group. CS is distinguished from other approaches such as cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation by its broad focus and social elements, aiming to improve domains such as quality of life (QoL) and mood as well as cognitive function.

Recommended in various guidelines and widely implemented internationally, questions remain regarding different modes of delivery and the clinical significance of any benefits. A systematic review of CS is important to clarify its effectiveness and place practice recommendations on a sound evidence base. This review was last updated in 2012.

Objectives

To evaluate the evidence for the effectiveness of CS for people with dementia, including any negative effects, on cognition and other relevant outcomes, accounting where possible for differences in its implementation.

Search methods

We identified trials from a search of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group Specialized Register, last searched on 3 March 2022. We used the search terms: cognitive stimulation, reality orientation, memory therapy, memory groups, memory support, memory stimulation, global stimulation, cognitive psychostimulation. We performed supplementary searches in a number of major healthcare databases and trial registers to ensure the search was up‐to‐date and comprehensive.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of CS for dementia published in peer review journals in the English language incorporating a measure of cognitive change.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. As CS is a psychosocial intervention, we did not expect those receiving or delivering CS to be blinded to the nature of the intervention. Where necessary, we contacted study authors requesting data not provided in the papers. Where appropriate, we undertook subgroup analysis by modality (individual versus group), number of sessions and frequency, setting (community versus care home), type of control condition and dementia severity. We used GRADE methods to assess the overall quality of evidence for each outcome.

Main results

We included 37 RCTs (with 2766 participants), 26 published since the previous update. Most evaluated CS groups; eight examined individual CS. Participants' median age was 79.7 years. Sixteen studies included participants resident in care homes or hospitals. Study quality showed indications of improvement since the previous review, with few areas of high risk of bias. Assessors were clearly blinded to treatment allocation in most studies (81%) and most studies (81%) reported use of a treatment manual by those delivering the intervention. However, in a substantial number of studies (59%), we could not find details on all aspects of the randomisation procedures, leading us to rate the risk of selection bias as unclear.

We entered data in the meta‐analyses from 36 studies (2704 participants; CS: 1432, controls: 1272). The primary analysis was on changes evident immediately following the treatment period (median length 10 weeks; range 4 to 52 weeks). Only eight studies provided data allowing evaluation of whether effects were subsequently maintained (four at 6‐ to 12‐week follow‐up; four at 8‐ to 12‐month follow‐up). No negative effects were reported. Overall, we found moderate‐quality evidence for a small benefit in cognition associated with CS (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.40, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.55). In the 25 studies, with 1893 participants, reporting the widely used MMSE (Mini‐Mental State Examination) test for cognitive function in dementia, there was moderate‐quality evidence of a clinically important difference of 1.99 points between CS and controls (95% CI: 1.24, 2.74).

In secondary analyses, with smaller total sample sizes, again examining the difference between CS and controls on changes immediately following the intervention period, we found moderate‐quality evidence of a slight improvement in self‐reported QoL (18 studies, 1584 participants; SMD: 0.25 [95% CI: 0.07, 0.42]) as well as in QoL ratings made by proxies (staff or caregivers). We found high‐quality evidence for clinically relevant improvements in staff/interviewer ratings of communication and social interaction (5 studies, 702 participants; SMD: 0.53 [95% CI: 0.36, 0.70]) and for slight benefits in instrumental Activities of Daily Living, self‐reported depressed mood, staff/interviewer‐rated anxiety and general behaviour rating scales. We found moderate‐quality evidence for slight improvements in behaviour that challenges and in basic Activities of Daily Living and low‐quality evidence for a slight improvement in staff/interviewer‐rated depressed mood. A few studies reported a range of outcomes for family caregivers. We found moderate‐quality evidence that overall CS made little or no difference to caregivers' mood or anxiety.

We found a high level of inconsistency between studies in relation to both cognitive outcomes and QoL. In exploratory subgroup analyses, we did not identify an effect of modality (group versus individual) or, for group studies, of setting (community versus care home), total number of group sessions or type of control condition (treatment‐as‐usual versus active controls). However, we did find improvements in cognition were larger where group sessions were more frequent (twice weekly or more versus once weekly) and where average severity of dementia among participants at the start of the intervention was 'mild' rather than 'moderate'. Imbalance in numbers of studies and participants between subgroups and residual inconsistency requires these exploratory findings to be interpreted cautiously.

Authors' conclusions

In this updated review, now with a much more extensive evidence base, we have again identified small, short‐term cognitive benefits for people with mild to moderate dementia participating in CS programmes. From a smaller number of studies, we have also found clinically relevant improvements in communication and social interaction and slight benefits in a range of outcomes including QoL, mood and behaviour that challenges. There are relatively few studies of individual CS, and further research is needed to delineate the effectiveness of different delivery methods (including digital and remote, individual and group) and of multi‐component programmes. We have identified that the frequency of group sessions and level of dementia severity may influence the outcomes of CS, and these aspects should be studied further. There remains an evidence gap in relation to the potential benefits of longer‐term CS programmes and their clinical significance.

Keywords: Aged, Humans, Cognition, Cognition/physiology, Dementia, Dementia/therapy, Memory, Memory/physiology, Orientation, Orientation/physiology, Psychotherapy, Psychotherapy/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Can cognitive stimulation benefit people with dementia?

Key messages

‐ For people with mild‐to‐moderate dementia, cognitive stimulation probably leads to small benefits in cognition (the general ability to think and remember).

‐ We found a range of other probable benefits, including improved well‐being, mood and day‐to‐day abilities, but benefits were generally slight and, especially for cognition and well‐being, varied greatly between studies.

‐ Most studies evaluated group cognitive stimulation. Future studies should try to clarify the effects of individual cognitive stimulation, assess how often group sessions should take place to have the best effect, and identify who benefits most from cognitive stimulation.

What is dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term for numerous brain disorders. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common of these. People of all ages can develop dementia, but most often it occurs in later life. People with dementia typically experience a decline in their cognitive abilities, which can impair memory, thinking, language and practical skills. These problems usually worsen over time and can lead to isolation, upset and distress for the person with dementia and those providing care and support.

Cognitive stimulation

Cognitive stimulation (CS) is a form of 'mental exercise' developed specifically to help people with dementia. It involves a wide range of activities aiming to stimulate thinking and memory generally, including discussion of past and present events and topics of interest, word games, puzzles, music and creative practical activities. Usually delivered by trained staff working with a small group of people with dementia for around 45 minutes twice‐weekly, it can also be provided on a one‐to‐one basis. Some programmes have trained family carers to provide CS to their relative.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out if CS was better for people living with dementia than usual care or unstructured social activities to improve:

‐ cognitive abilities (including memory, thinking and language skills)

‐ well‐being and mood

‐ day‐to‐day abilities

‐ distress and upset for the person with dementia and/or carers

We also wanted to find out if family carers experienced any changes associated with the person with dementia receiving CS or if there were any unwanted effects.

What did we do? We searched for studies that looked at group or individual CS compared with usual care or unstructured social activity in people living with dementia.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 37 studies involving 2766 participants with mild or moderate dementia and an average age of 79 years. The biggest study involved 356 participants, the smallest 13. The studies were conducted in 17 countries from five continents, with most in Europe. Fewer than half (16) included participants living in care homes or hospitals. The length of the trials varied from four weeks to two years. Sessions per week varied from one to six. The overall number of sessions varied from eight to 520. Most studies lasted for around 10 weeks, with around 20 sessions. Most studies offered CS in groups, with just eight examining individual CS.

Main results

No negative effects were reported. We found that CS probably results in a small benefit to cognition at the end of the course of sessions compared with usual care/unstructured activities. This benefit equates roughly to a six‐month delay in the cognitive decline usually expected in mild‐to‐moderate dementia. We found preliminary evidence suggesting that cognition benefited more when group sessions occurred twice weekly or more (rather than once weekly) and that benefits were greater in studies where participants’ dementia at the outset was of mild severity.

We also found that participants improved on measures of communication and social interaction and showed slight benefits in day‐to‐day activities and in their own ratings of their mood. There is probably also a slight improvement in participants’ well‐being and in experiences that are upsetting and distressing for people with dementia and carers. We found CS probably made little or no difference to carers' mood or anxiety.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Our confidence in the evidence is only moderate because of concerns about differences in results between studies. We cannot be certain of the exact reasons for these differences, but we noted that studies varied in:

• the way CS was delivered (individually, in groups, using an app) and the programme of activities included

• who delivered the programme (trained professionals, care workers, family carers)

• the frequency of sessions (1 per week to 5 per week)

• the duration of the programme (from 4 weeks to 1 or 2 years)

• the type(s) of dementia with which participants were diagnosed and the severity of the dementia

• whether participants lived in care homes and hospitals or in their own homes

We were unable to examine as many of these sources of potential difference as would have been desirable because of the relatively small number of studies reflecting each aspect.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

This review updates our previous review from 2012, with evidence up‐to‐date to March 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Cognitive stimulation compared to no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) in people with dementia.

| Cognitive stimulation compared to no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) in people with dementia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with dementia Setting: care homes and long‐term care facilities; community settings including daycare and outpatients Intervention: cognitive stimulation Comparison: no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) | Risk with cognitive stimulation | |||||

| Cognition Assessed with various brief cognitive tests including: ADAS‐Cog, MMSE, Global Cognitive Score, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, MoCA, ACE‐III, CAM‐COG DS, ENB2 | SMD 0.4 SD higher (0.25 higher to 0.55 higher) | ‐ | 2340 (34 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate a | Cognitive stimulation probably results in a small increase in cognition. | |

| Quality of Life: self‐report Assessed with: QoL‐AD (17 studies) and EQ‐5D (1 study) | SMD 0.25 SD higher (0.07 higher to 0.42 higher) | ‐ | 1584 (18 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate a | Cognitive stimulation probably results in a slight increase in self‐reported quality of life. | |

| Communication and social interaction Assessed with: Holden Communication Scale; NOSGER Social Behaviour subscale; Narrative language ‐ communicative abilities | SMD 0.53 SD higher (0.36 higher to 0.7 higher) | ‐ | 702 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Cognitive stimulation results in an increase in communication and social interaction. | |

| Mood: self‐reported Assessed with: Geriatric Depression Scale (14; 15 and 30‐item versions); HADS Depression Scale; CESD‐R; Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (self‐report) | SMD 0.11 SD higher (0.08 lower to 0.31 higher) | ‐ | 787 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Cognitive stimulation results in a slight improvement in self‐reported mood. | |

|

Mood: interviewer/staff‐rated Assessed with Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; NOSGER‐Mood subscale; Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale |

SMD 0.35 SD higher (0.09 higher to 0.61 higher) | ‐ | 1011 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low bc | Cognitive stimulation may result in a slight improvement in mood rated by an interviewer or by staff. | |

| Instrumental ADL Assessed with: Lawton Brody IADL scale; Disability Assessment for Dementia; NOSGER IADL subscale; Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale; ADCS‐ADL scale; Rapid Disability Rating Scale | SMD 0.15 SD higher (0.04 higher to 0.26 higher) | ‐ | 1318 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Cognitive stimulation results in a slight increase in Instrumental ADL. | |

| Behaviour that challenges Assessed with: NPI; NPI‐Agitation subscale; NOSGER‐Challenging Behaviour subscale; BEHAVE‐AD; Dementia Behaviour Disturbance Scale | SMD 0.18 SD higher (0.01 lower to 0.38 higher) | ‐ | 1340 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate b | Cognitive stimulation probably results in a slight improvement in behaviour that challenges. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADL: activities of daily living; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

a Downgraded one point for inconsistency as moderate heterogeneity was present.

b Downgraded one point for inconsistency as substantial heterogeneity was present.

c Downgraded one point for imprecision as 95% CIs included both a clinically important and a negligible benefit.

Summary of findings 2. Group cognitive stimulation compared to no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) in people with dementia.

| Group cognitive stimulation compared to no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) in people with dementia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with dementia Setting: care homes and long‐term care facilities; community settings including daycare and outpatients Intervention: group cognitive stimulation Comparison: no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no cognitive stimulation (post‐treatment) | Risk with group cognitive stimulation | |||||

| Cognition Assessed with various brief cognitive tests including: ADAS‐Cog, MMSE, Global Cognitive Score; Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, MoCA, ENB2 | SMD 0.43 SD higher (0.26 higher to 0.59 higher) | ‐ | 1637 (27 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate a | Group cognitive stimulation probably results in a small increase in cognition. | |

| Quality of Life: self‐report Assessed with: QoL‐AD | SMD 0.28 SD higher (0.05 higher to 0.52 higher) | ‐ | 1058 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low bc | Group cognitive stimulation may result in a slight increase in self‐reported quality of life. | |

| Communication and social interaction Assessed with: Holden Communication Scale; NOSGER‐Social Behaviour subscale; Narrative language ‐ communicative abilities | SMD 0.53 SD higher (0.36 higher to 0.7 higher) | ‐ | 702 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Group cognitive stimulation results in an increase in communication and social interaction. | |

| Mood: self‐reported assessed with: Geriatric Depression Scale (14 and 30‐item versions); CESD‐R | SMD 0.2 SD higher (0.06 lower to 0.45 higher) | ‐ | 299 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate d | Group cognitive stimulation probably results in a slight improvement in self‐reported mood. | |

| Mood: interviewer/staff‐rated Assessed with: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; NOSGER‐Mood subscale; Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale | SMD 0.4 SD higher (0.14 higher to 0.67 higher) | ‐ | 959 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate b | Group cognitive stimulation probably results in a small improvement in interviewer/staff‐rated mood. | |

| Instrumental ADL Assessed with: Lawton‐Brody IADL scale; Disability Assessment for Dementia; NOSGER IADL subscale; ADCS‐ADL scale; Rapid Disability Rating Scale | SMD 0.2 SD higher (0.05 higher to 0.35 higher) | ‐ | 687 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Group cognitive stimulation results in a slight increase in Instrumental ADL. | |

| Behaviour that challenges assessed with: NPI; NPI‐Agitation subscale; NOSGER‐Challenging Behaviour subscale; BEHAVE‐AD; Dementia Behaviour Disturbance subscale | SMD 0.33 SD higher (0.11 higher to 0.54 higher) | ‐ | 754 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate a | Group cognitive stimulation probably results in a slight improvement in behaviour that challenges. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADL: activities of daily living; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

a Downgraded one point for inconsistency as moderate heterogeneity was present.

b Downgraded one point for inconsistency as substantial heterogeneity was present.

c Downgraded one point for imprecision as 95% CIs included both a clinically important and a negligible effect.

d Downgraded one point for imprecision as fewer than 400 participants.

Background

Description of the condition

Dementia is widely regarded as one of the greatest current challenges facing health and social care globally.

The dementias comprise a number of neurodegenerative disorders of the brain, which have in common that they:

develop during life (i.e. they represent a change from a previous level of function or ability)

lead to impairment in a number of areas of cognitive function, typically including memory and orientation but also language skills, reasoning, judgement, visuo‐spatial skills, executive function and practical abilities may be affected

have an impact on day‐to‐day life abilities

may have an impact on personality and social relationships

are usually progressive

The most common types of dementia are Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022). Mixed‐types of dementia are common, with both Alzheimer and vascular changes evident at postmortem in the brains of people who have developed dementia in late life. The severity of dementia is often described as 'mild' in the early stages when, with support, the person is able to continue with many activities; 'moderate' when more support and personal care is required; and 'severe' when the person may need help with almost all aspects of day‐to‐day life. It is estimated that 55% of people with dementia will have a mild dementia, 32% moderate and 12% severe (Prince 2014).

It is estimated that there were over 55 million people worldwide living with dementia in 2020 and this number is projected to almost double every 20 years, reaching 78 million in 2030 and 139 million in 2050 (ADI 2022). The increase in numbers with dementia reflects the growth globally in the numbers of people living into later life, as the risk of developing dementia increases markedly with age. For example, whilst 2% of those age 65 to 69 years will have a dementia, this rises to 20% of those aged 85 to 89 years (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022).

Taking together, the direct costs of medical care and of social care and of costs attributed to the unpaid care provided by families and others, the annual global cost of dementia is now above US$1.3 trillion and is expected to rise to US$2.8 trillion by 2030. ADI 2022 point out that, if global dementia care were a country, it would be the 14th largest economy in the world.

In the UK, it is estimated that there are 944,000 people living with dementia, of whom 42,000 are aged under 65 years (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022). Of those aged 65 years and over, 39% live in care homes. People with dementia form the majority of care home residents in the UK, with 70% of care home residents having dementia (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022). However, most people with dementia live in their own homes, often with support from family members. This support carries a considerable human as well as economic cost. It is estimated that 1.1 billion hours are spent on unpaid care, from family and friends, for people with dementia each year and 36% of carers spend more than 100 hours per week providing care (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022). Nearly half (49%) of family carers report a significant sense of burden and nearly a third report depression (Collins 2020) and anxiety (Kaddour 2020). Female carers are especially at risk of depression, and around two‐thirds of carers for people with dementia are women (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022). The majority of carers (63.5%) report that they have had no or not enough support (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022).

Medications (notably acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) have been available for some years for Alzheimer's disease and these are seen as offering symptomatic help (Alzheimer's Research UK 2022). Non‐pharmacological interventions are viewed as a key component of post‐diagnostic support, with the potential for enhancing well‐being and confidence, but Alzheimer's Society 2022 point out that, in the UK at least, provision of such support for people with dementia and their carers after diagnosis has often been lacking.

Description of the intervention

Interventions with a cognitive focus have a long history of development and application in dementia care (Woods 1977; Woods 2018a). Clare and Woods (Clare 2004) distinguished ‘Cognitive stimulation’ from other therapeutic approaches with a cognitive focus, proposing the following definition:

‘Cognitive stimulation is engagement in a range of activities and discussions (usually in a group) aimed at general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning.’

In contrast, ‘Cognitive training’ is defined as:

‘guided practice on a set of standard tasks designed to reflect particular cognitive functions; a range of difficulty levels may be available within the standard set of tasks to suit the individual's level of ability. It may be offered in individual or group sessions, with pencil and paper or computerised exercises.’

and ‘Cognitive rehabilitation’ as:

‘an individualised approach where personally relevant goals are identified and the therapist works with the person and his or her family to devise strategies to address these. The emphasis is on improving performance in everyday life rather than on cognitive tests, building on the person's strengths and developing ways of compensating for impairments.’

Cochrane reviews have been carried out or are in progress for each of these three distinct approaches to improving outcomes for people living with dementia (Bahar‐Fuchs 2019; Kudlicka 2019; Woods 2012) using agreed definitions to provide consistency in a field where there has been a tendency for these terms to be used interchangeably.

Descriptions of group‐based activities and discussions aimed at general improvements in cognitive function, communication and social well‐being can be traced back for over 50 years. Reality orientation (RO) (Taulbee 1966) was developed in the late 1950s as a response to confusion and disorientation in older patients in hospital units in the USA, and was the precursor of the cognitive stimulation approach. ‘RO Classes’ were held for 30 minutes once or twice per day. Basic personal and current information was presented to the patient and a variety of materials used, such as individual calendars, word‐letter games, building blocks and large‐piece puzzles. A Reality Orientation board would be used in each session and would list the name of the unit and its location, the day, date, weather, current events etc. The approach emphasised the engagement of nursing assistants in a hopeful, therapeutic process.

Following the first controlled evaluation of RO groups being reported in the UK by Brook 1975, a number of other small‐scale controlled evaluations of RO groups followed (Holden 1995), with outcome measures typically including assessments of orientation, other aspects of cognitive functioning and level of independent functioning. A Cochrane review specifically examining Reality Orientation (Spector 2000a; Spector 2000b) concluded that there was some evidence that RO had benefits for people with dementia on both cognition and behaviour. However, RO has been little practised or researched since 1990 and has attracted some criticism (Burton 1982; Dietch 1989), especially for being applied in a mechanical, inflexible, insensitive and confrontational manner, with the potential for a negative effect on the person. Doubts were also raised about the clinical significance of any improvements (e.g. Powell‐Proctor 1982); the person with dementia might now know what day of the week it was but would this have any meaningful impact on the person's life?

Subsequently, there began to be increasing discussion of 'cognitive stimulation', in relation to both normal ageing and dementia (Breuil 1994; Small 2002), Recognising that RO fitted well with this concept of cognitive stimulation and that it had the beginnings of an evidence base, attempts were made to harness its positive aspects whilst ensuring that it was implemented in a properly sensitive and respectful manner (Spector 2001; Woods 2002), in keeping with best practice person‐centred care, as had been influentially articulated by Kitwood 1997. At the same time, developments in measurement of outcomes for people with dementia (e.g. Logsdon 2002) meant that quality of life could now be envisaged as an outcome of psychosocial interventions, with cognitive function and orientation no longer the only indices of effectiveness. Given the concerns discussed above of a possible negative effect, measures of quality of life, well‐being and mood are highly pertinent outcome measures, alongside any cognitive benefits.

The publication of a manual for cognitive stimulation groups (Spector 2006) setting out in some detail the approach used in a large randomised controlled trial in the UK (Spector 2003) facilitated the implementation of the approach in the UK and internationally, and has formed the basis of a number of further evaluations (Lobbia 2019). Implementation was also facilitated by the recommendation in the UK (NICE‐SCIE 2006) Guidelines that ‘people with mild/moderate dementia of all types should be given the opportunity to participate in a structured group cognitive stimulation programme’. Protocols have been developed for the cultural adaptation of the approach, whilst maintaining the key principles and elements (Aguirre 2014), and the approach is used in over 20 countries. Other manualised cognitive stimulation approaches have also been developed and evaluated such as 'NEUROvitalis' (Middelstädt 2016) and 'MAKS' (Graessel 2011) but, to date, have been less widely implemented internationally.

How the intervention might work

Attempts to understand the mechanisms by which cognitive stimulation might lead to benefits for people living with dementia are at an early stage. The approach can be seen as bringing together three aspects: a component of generalised cognitive exercise and a component of social interaction and support, both underpinned by a person‐centred approach, which upholds the dignity and value of the person living with dementia (Woods 2018a). In recent years, a number of qualitative studies have been published, reporting the experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers in relation to both group and individual cognitive stimulation (Gibbor 2020a). All three aspects emerge clearly from these qualitative studies on cognitive stimulation (Gibbor 2020a; Leung 2018; Orfanos 2020).

In relation to generalised cognitive exercise, Gibbor 2020a, for example, found that 'continued stimulation' was important and Leung 2018 reported on people with dementia emphasising the importance of 'being mentally active' and adopting the principle 'use it or lose it'. Although treating the brain as a muscle that can be made stronger through exercise may be a crude analogy, the notion that mentally stimulating activities may improve cognitive function or even prevent cognitive decline has been widely discussed in relation to normal ageing (e.g. Gallacher 2005; Salthouse 2006). Indeed, it has been also sometimes characterised in the literature as ‘use it or lose it’ (Hultsch 1999), perhaps reflecting a general view that lack of cognitive activity hastens cognitive decline. In similar vein, the influential Lancet commission recommends 'keeping cognitively, physically, and socially active in midlife and later life' (Livingston 2020). The argument then is that if cognitively engaging activities can have a role in slowing or even preventing decline in cognitive functioning in older people in general, could they have an effect on people experiencing a dementia?

Whilst feasibly cognitive training could also be seen as exercising the brain, cognitive stimulation places cognitive exercise within a social and interpersonal context. The social interaction and support aspects emerge in qualitative themes such as 'being with others' and 'relationships' (Gibbor 2020a), 'opportunities to communicate' (Leung 2018) and 'importance of companionship and getting to know others', and 'togetherness and shared identity' (Orfanos 2020). The underpinning values of the person‐centred approach are evident in themes such as 'confidence' and 'relaxed environment' (Gibbor 2020a) and 'providing supportive/non‐threatening group environment' (Leung 2018) and 'group support' (Orfanos 2020). Orfanos 2020 highlighted the contribution of the group format to the benefits of cognitive stimulation, which raises the question of how the social and interpersonal component can best be retained in individual cognitive stimulation. Neuropsychological studies have also provided some support for the importance of the interpersonal aspects, in that several studies have shown specific improvements in language skills and performance following cognitive stimulation (Hall 2013; Spector 2010).

A potential mechanism for improvements related to cognitive stimulation arising from the social and value‐based elements relate to the concept of 'excess disability' (Sabat 1994). This suggests that the person with dementia may, for a variety of reasons, not be able to function at their optimal or potential level. The person may be socially withdrawn, feel a lack of confidence, feel unmotivated or anxious, for example. Cognitive stimulation may then address some of these barriers, enhancing social confidence, giving a greater sense of purpose, engaging the person with others, promoting relaxation and enjoyment. The mental exercise component may interact with these aspects, providing practice and experience of cognitive successes in a supportive environment, when previously fear of failure has inhibited the making of any response or contributing to conversation. The inter‐connection of the cognitive exercise and social elements is supported by findings that improvements in quality of life are mediated by improvements in cognition (Woods 2006). This suggests that there is one process of change, rather than two separate processes: one involving mental exercise, improving cognition, and one involving social enjoyment, improving quality of life.

Brain imaging has also been used to seek to explore potential mechanisms of action of cognitive stimulation (Liu 2018; Liu 2021). The preliminary results using structural and functional MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scanning suggest that cognitive stimulation 'maintains/enhances brain reserve both structurally and functionally', with increased connectivity despite an overall decline in volume of grey matter (which also occurred in control participants not receiving cognitive stimulation). The connectivity increased in a network believed to be important for 'sense‐making' in a social context and mental self‐representation, and it is suggested may relate to the person‐centred nature of the intervention. However, these studies involved a small number of participants and this work requires further development.

Why it is important to do this review

Since the previous version of this review (Woods 2012), cognitive stimulation continues to be recommended in guidelines for dementia care practice such as those published by NICE 2018 and Alzheimer's Disease International (Prince 2011). In a report on post‐diagnostic support in the UK, the Alzheimer's Society recommend that people diagnosed with dementia should be offered 'equitable access to non‐pharmacological interventions as per national guidance, such as cognitive stimulation therapy (CST), and ensure all memory services have access to CST by April 2024' (Alzheimer's Society 2022). Such guidelines and recommendations have increased the implementation of cognitive stimulation around the world and, in a survey of UK Memory Clinics, Holden 2020 found that 87% of services responding were offering cognitive stimulation interventions. It is important that both clinical guidelines and clinical practice are based on up‐to‐date evidence, and so an update of the review is essential.

As well as the approach being more widely used, more adaptations to delivery are being made. Notably, the initial emphasis was on a group approach, and thematic analysis of interviews with participants in cognitive stimulation groups reinforces the perceived importance of the group experience (Orfanos 2020; Spector 2011). However, interest from family caregivers in using the approach at home has led to the development of individual cognitive stimulation, delivered on a one‐to‐one basis (Yates 2014). This has the disadvantage of lacking some of the social elements inherent in a group context, but does allow greater individualisation of activities, in relation to the person’s interests and preferences. It also allows the inclusion of people with dementia who are unable to attend or participate in group sessions, for reasons of logistics or due to sensory difficulties which can prevent engagement in group activities. Individual cognitive stimulation can be delivered by paid care staff and professionals or by volunteers, as well as by family members. The onus is on the person facilitating the session to ensure that it remains a social experience, albeit on a smaller scale than in a group context. Recommendations have largely been made relating to group cognitive stimulation, so it is timely to consider also the evidence‐base for individual cognitive stimulation.

Other developments include the use of digital technology to support cognitive stimulation (e.g. Rai 2020). This could assist those offering the intervention, by readily providing a wider range of activities, games and materials for use in group or individual sessions. The development of a cognitive stimulation‐based television programme also offers an alternative mode of delivery (Streater 2020). When using digital approaches, care would need to be taken to retain the social stimulation aspect of the approach, of course. As a means of maintaining services during the Covid pandemic, Cheung 2021 described the development and feasibility of virtual cognitive stimulation groups using Zoom video‐conferencing, retaining the social and peer‐interaction elements of the approach despite remote delivery.

There is also a trend to combine cognitive stimulation with other interventions and offer a multi‐component approach. For example, physical exercise, which is widely recognised as beneficial for older people and for people with dementia, has been incorporated to some extent in many cognitive stimulation programmes. In order to make sense of the evidence base, it is important to be as clear as possible regarding the interventions included in any systematic review, and to adopt clear operational definitions for inclusion of studies. In the current review, we only included studies where the predominant intervention met our definition of cognitive stimulation.

Given the long‐standing and typically progressive nature of difficulties associated with dementia, there is also interest as to the required duration and intensity of these approaches. If, say, cognitive stimulation is associated with benefits over a three‐month period, will these benefits continue and/or will continued input be required to maintain them? How frequent do cognitive stimulation sessions need to be to have the most beneficial effects? Does effectiveness vary with the level of impairment or between care home and community settings?

In the review, we consider cognitive functioning as a primary outcome, as this would appear to be the minimum expectation of a general approach with this focus. However, weight must also be given to indices of quality of life and well‐being, in view of the early criticism that a difference of, say, a few points on a test of orientation may, in itself, be of marginal benefit to the person living with dementia. The effects on the person's everyday life need to be considered in evaluating the meaning of any changes observed for the individual and his or her supporters, and have been highlighted by participants (Spector 2011). The impact on family caregivers and care workers is also important to consider as they are key partners in the process of care. Where family caregivers have the additional responsibility of delivering the intervention, as in some applications of individual cognitive stimulation, the impact on them is especially relevant.

This updated review (the third, including the original superseded Reality Orientation review) will then need to consider developments in research and practice including the following: the modality of delivery (individual or group); the duration and frequency of the intervention; the involvement of family caregivers in delivery of the intervention; the use of digital technology; and the classification of multi‐component interventions, as well as the setting of the intervention (care home versus community), the severity of dementia‐related impairment and the type of comparison groups employed.

Objectives

To evaluate the evidence for the effectiveness of CS for people with dementia, including any negative effects, on cognition and other relevant outcomes, accounting where possible for differences in its implementation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies that met the following criteria: • Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that used cognitive stimulation as an intervention for people living with dementia. • Control activity was no treatment, treatment‐as‐usual or a passive treatment such as basic social contact. • Study was written in English and published in a peer‐reviewed journal article.

We included in the review trials published since the previous version of this review that did not publish (or later supply) adequate information about study design and results but we did not include these studies in the meta‐analysis. Details are noted in Characteristics of included studies.

Types of participants

Participants with a diagnosis of dementia, according to established diagnostic criteria. The main diagnostic categories that we included were Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia or mixed Alzheimer's and vascular dementia. We considered these diagnostic categories together. We did not include participants with mild cognitive impairment, where the extent of cognitive impairment or its effects on day‐to‐day function were insufficient to justify a dementia diagnosis. In this revised review, we were also able to consider studies focusing on other forms of dementia, such as Lewy body dementia and Parkinson's Disease Dementia.

We evaluated severity of dementia through group mean scores, range of scores, or individual scores on a standardised scale such as the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein 1975) or Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Hughes 1982). We included all levels of severity.

Qualifying participants received the intervention in a range of settings, including their own home, as outpatients and in daycare and residential settings.

We did not apply any specific restrictions regarding age.

We included data from family caregivers, where available.

We documented whether participants were receiving concurrent treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, where possible.

Types of interventions

We considered studies for this review if they described a cognitive stimulation intervention targeting cognitive and social functioning. These interventions may also have been described as RO groups, sessions or classes.

We adopted the definition of cognitive stimulation as proposed by Clare 2004. This meant that we excluded some studies which described their intervention as 'cognitive stimulation'. Interventions needed to offer exposure to generalised cognitive activities rather than training in a specific modality.

Where the intervention included multiple components e.g. cognitive stimulation and physical exercise, we included the study only if more than 50% of the intervention time was spent in activities meeting our definition of cognitive stimulation.

We did not include studies where the predominant intervention involved reminiscence, defined as 'the discussion of memories and past experiences with other people using tangible prompts such as photographs or music to evoke memories and stimulate conversation', as this intervention is the subject of a separate Cochrane review (Woods 2018b).

Interventions were typically conducted in a group to enhance social functioning, but could involve family or paid caregivers offering cognitive stimulation on an individual basis.

We included studies if a comparison was made to 'no treatment', 'standard treatment' or 'placebo'. We defined standard treatment as the treatment that was normally provided to people with dementia in the study setting and could include provision of medication, clinic consultations, contact with a community mental health team, daycare, or support from voluntary organisations. Placebo conditions could consist, for example, of an equivalent number of sessions in which general support, but no structured intervention, was offered. We did not consider comparisons with other activities or therapies such as cognitive training in this review.

For inclusion of a study, we required a minimum intervention duration of one month. We noted the number of treatment sessions, but we did not apply any restrictions on this.

Types of outcome measures

We included only studies including at least one measure of cognitive function, as this was the focus of the review.

We considered outcomes in relation to the impact of the intervention on the person with dementia and on the primary family caregiver. Studies could present data in both these categories.

We considered short‐term (immediately after the intervention) and medium‐term (follow‐up one month to one year after the intervention finished) outcomes.

We considered outcomes for the person with dementia and the caregiver where these were assessed using scores on standardised tests, rating scales and questionnaires.

We noted rates of attrition and reasons for participants dropping out from the study.

Primary outcomes

For the primary outcome measure we sought to identify whether short‐term changes were observed following the intervention for the person with dementia on performance on at least one test of cognitive functioning (including tests of memory and orientation).

Secondary outcomes

Outcomes for the person with dementia

We considered the following variables as secondary outcome measures for the person with dementia.

Self‐reported, clinically‐rated or carer‐reported (proxy) measures for mood of the person with dementia.

Self‐reported or carer‐reported (proxy) quality of life or well‐being measures for the person with dementia.

Observer or carer ratings of everyday functioning (activities of daily living) of the person with dementia.

Carer ratings of the participant's behaviour.

Clinician or carer ratings of 'behaviour that challenges' relating to the person with dementia.

Clinician or carer ratings of the communication and social interaction of the person with dementia.

Self‐reported quality of relationship with the carer.

'Carer' in this context included care staff as well as family caregivers.

Outcomes for the family caregiver

We considered all outcomes for the family caregiver as secondary. We considered the following outcomes for the family caregiver.

Self‐reported quality of life.

Self‐reported depression and anxiety.

Self‐reported burden, stress and coping.

Self‐reported quality of relationship with the person with dementia.

Self‐reported resilience.

Adverse outcomes

There is a potential risk that participants may find the process of cognitive stimulation over‐ or under‐challenging, if not targeted at the appropriate level. We monitored the potential for adverse outcomes by observing negative responses on the outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group Specialised Register, on 3 March 2022. The search terms used were: cognitive stimulation, reality orientation, memory therapy, memory groups, memory support, memory stimulation, global stimulation, cognitive psychostimulation.

The Register is maintained by the Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and cognitive enhancement in healthy populations. The studies are identified from:

monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and LILACS;

monthly searches of a number of trial registers: meta Register of Controlled Trials; Umin Japan Trial Register; WHO portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; Chinese Clinical Trials Register; German Clinical Trials Register; Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others);

quarterly search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library);

six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources: Web of Knowledge Conference Proceedings; Index to Theses; Australasian Digital Theses.

Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, CENTRAL and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG).

We ran additional searches in each of the sources listed above to ensure that the search for the review was as up‐to‐date as possible. The search strategies used can be seen in Appendix 1

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of full‐text papers, including those of relevant published systematic reviews, for further references, and review authors searched personal holdings of references to reports and trials. We sent emails to authors of included RCTs asking for essential information, where this was not available in the publication, such as relevant statistics.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this revised review, following deduplication, we imported into Covidence all references identified in the searches, their titles and abstracts. Three review authors (HR, EE and BW) undertook the selection of studies, with the title and abstract of each study being independently reviewed by two reviewers, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed above. If one of the three reviewers had been involved in the study under consideration, s/he did not participate in the screening for that study. We automatically retained studies that had been included in previous versions of this review for further consideration. We discussed any disagreements and reached consensus by involving the third reviewer, where appropriate.

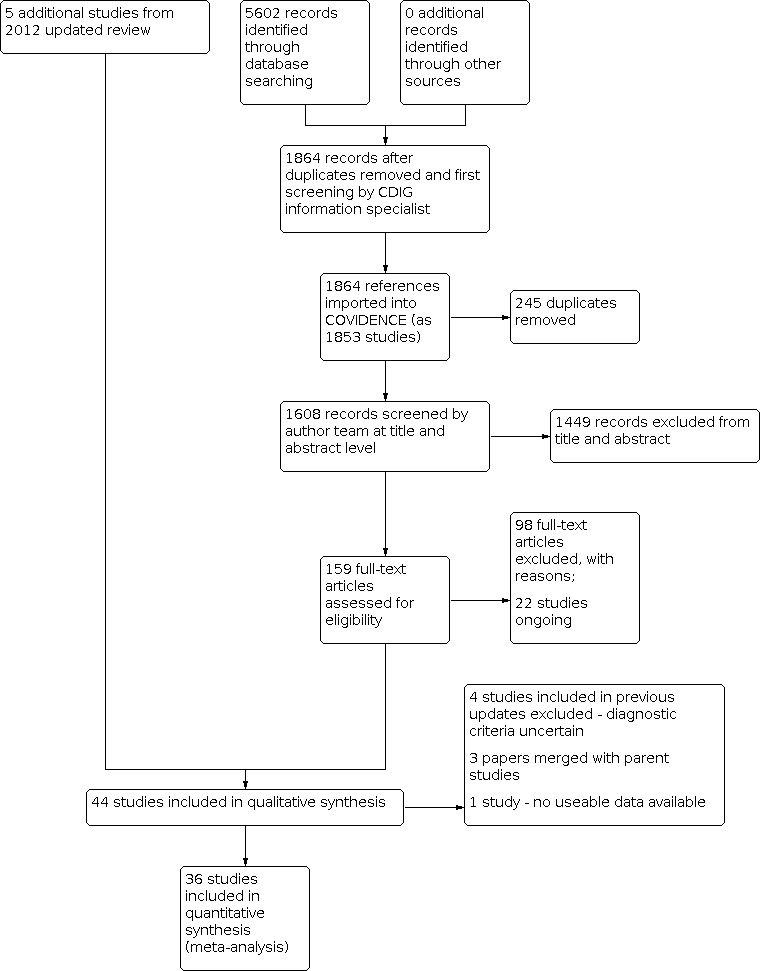

We excluded obviously irrelevant studies. We then obtained the full text of remaining studies and excluded studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria with reasons outlined in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (HR, EE and BW) independently extracted descriptive characteristics, study methodology data and study results from the included studies and recorded them on a data collection form. Two reviewers extracted the data from each study, ensuring that these reviewers had not been involved in the study in question. We compared the data and resolved any disagreements through consensus. We transferred extracted data to RevMan.

For each outcome measure, the authors sought to obtain data on every participant randomised irrespective of whether the participant was excluded or dropped out of the intervention or research (i.e. data from an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis). If these data were not available in the published studies, the review authors sought the data of those who completed the trials. Where necessary, we sent emails to trial authors requesting additional information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each trial, two of three review authors (HR, EE and BW) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias (version 1) tool (Higgins 2011). We resolved any initial disagreements with the third author. We attempted to obtain additional information from study authors when this was required. Based on the methods detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we classified each category of bias as 'low risk of bias,' 'high risk of bias' or 'unclear risk of bias.' An outline of this can be seen in Table 3. We did not rate 'Blinding of participants and personnel', as it is a given in research on psychosocial interventions that the person receiving the intervention and the person delivering it will be aware of the nature of the intervention. We expanded 'Other sources of bias' to identify whether a structured treatment manual had been used, and whether those delivering the intervention had received training and/or supervision, two important aspects of ensuring a consistent intervention of good quality. For selection bias, the meta‐analysis included only trials with a low or unclear risk of bias, in order to meet the study inclusion criteria as a randomised controlled trial. The ratings assigned with respect to each study's risk of bias are summarised in the risk of bias tables, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

1. Risk of bias assessment table.

| Domain | Risk of bias judgement | ||

| Selection bias | Low | High | Unclear |

| Random sequence generation | Assigned if simple randomisation was used (e.g. computer‐generated random sequence, coin tossing). | Assigned if study reported an inadequate randomisation method (e.g. using date of birth or odd/even numbers). | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

| Assigned if restricted randomisation was used (e.g. block randomisation, provided that within groups randomisation was not affected). | |||

| Allocation Concealment | Assigned if there was evidence of concealed allocation sequence in which allocations could not have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. | Assigned if those enrolling participants were aware of the group (or period in a cross‐over trial) to which the next enrolled participant would be allocated. | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

| Detection bias | Low | High | Unclear |

| Blinding of outcome assessors (blinding of participants and facilitators is not possible in psychosocial interventions). | Assigned if outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation. | Assigned if the outcome assessors were aware of treatment allocation (e.g. if the cognitive stimulation group leader was also an outcome assessor). | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

| Attrition bias | Low | High | Unclear |

| Incomplete outcome data | Assigned if the study reported levels of attrition, reasons for attrition and how missing data were dealt with. Assigned if the impact of missing data was not believed to alter the conclusions and there were acceptable reasons for the missing data. | Assigned if there was inadequate information regarding the level of attrition in each group, reasons for attrition and if missing data were not handled correctly. | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

| Reporting bias | Low | High | Unclear |

| Selective reporting | Assigned if study reported results of all outcome measures that were detailed in the methods section. If a study protocol was available, low risk of bias was assigned if the outcome assessments reported in the trial paper matched those detailed in the protocol. | Assigned if study did not report results of all outcome measures that were detailed in the methods section. Assigned if all outcome measures detailed in the protocol (if available) were not reported in the study. | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

| Other bias | Low | High | Unclear |

| Availability of training and supervision | Assigned if cognitive stimulation sessions were facilitated by people who had received some form of training to ensure the necessary principles of cognitive stimulation were adhered to. The definition of training was inclusive and could range from a brief session to a longer, more intensive course. This also applied to interventions delivered by trained family carers. The opportunity for facilitators to access appropriate supervision was also desirable. | Assigned if there was no evidence of facilitator training or supervision. | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

| Availability of manual, structure or protocol | Assigned if there was evidence of a documented intervention protocol, structure or manual outlining the content of each session to ensure the principles of cognitive stimulation were adhered to. | Assigned if there was no evidence of a treatment protocol, structure or manual for facilitators to follow. | Assigned if there was insufficient detail to judge the risk of bias as low or high. |

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Measures of treatment effect

As the outcomes measured in clinical trials of dementia and cognitive impairment often arise from ordinal rating scales, where the rating scales had a reasonably large number of categories, we treated the data as continuous outcomes arising from a normal distribution. For meta‐analysis of this type of data, the mean change scores from baseline, the standard deviation of the mean change and the number of participants for each treatment group at each assessment are required. The majority of study authors did not report change scores from baseline. We defined the baseline assessment as the latest available assessment prior to randomisation, but no longer than two months prior. Where change scores were not reported, we extracted the mean, standard deviation and number of participants for each treatment group at each time point and calculated the required summary statistics manually. In this case, we assumed a zero correlation between the measurements at baseline and assessment time. This method overestimates the standard deviation of the change from baseline, but this conservative approach is considered to be preferable in a meta‐analysis. Some studies (e.g. Gibbor 2020b) reported mean differences and 95% confidence intervals, which enabled us to calculate the appropriate statistics in RevMan. Lok 2020 provided data as medians and interquartile ranges, from which we calculated the required summary statistics following the methods proposed by Wan 2014, as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook (sections 6.5.2.5 and 6.5.2.9).

The meta‐analyses included the combination of data from trials that may not have used the same rating scale to measure a particular outcome. For example, cognition may have been measured by the MMSE in one study and the ADAS‐Cog in another. In this situation we used the standardised mean difference (SMD; the absolute mean difference (MD) divided by the standard deviation) to measure the treatment difference. Where pooled trials used the same rating scale or test to measure an outcome, we used the MD.

To allow comparisons with other scales assessing similar outcomes, it was necessary to reverse the change scores on certain scales, for example, for the ADAS‐Cog, where higher scores indicate worse cognitive performance.

Unit of analysis issues

In studies using a cross‐over design, only data from the first treatment phase after randomisation were eligible for inclusion.

Three studies used cluster‐randomisation. No analysable data were obtained from Lin 2018 and the studies reported by Cheung 2019 and Paddick 2017 were not large enough for planned adjustments to be made for clustering using estimated intraclass correlations.

Dealing with missing data

Where possible, review authors extracted data on all participants randomised. We preferred data from intention‐to‐treat analyses to per protocol or compliance analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We performed assessments of heterogeneity using both the Chi2 and I2 statistic. Review authors followed guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2021),to interpret heterogeneity percentages (i.e. 0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; and 75% to 100% reflects considerable heterogeneity). Following these recommendations (Deeks 2021), we considered heterogeneity to be present when the Chi² statistic was significant at the P = 0.1 level, or when l² was greater than 40%. Where substantial heterogeneity was detected, we considered exploring the sources of heterogeneity by conducting subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there were enough studies available, authors created a funnel plot to assess the risk of publication bias.

Data synthesis

The meta‐analyses presented in this updated review provide overall estimates of the treatment effect using a random‐effects model. In previous versions of the review, we have preferred a fixed‐effects model where heterogeneity is low, but with a substantial number of analyses showing high heterogeneity, this protocol change leads to a more consistent approach. As a result, confidence intervals may be broader than would have been obtained from a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed planned subgroup analyses with respect to the modality of the cognitive stimulation intervention (individual versus group) and environmental context (care home versus community) and severity of dementia (mild versus moderate, considering MMSE scores of 20 and below as indicating 'moderate' and above 20 as 'mild' dementia, NICE‐SCIE 2006). We undertook further subgroup analyses to investigate high levels of heterogeneity, considering feasible moderator variables such as frequency of sessions and duration of intervention. We planned a further subgroup analysis to compare studies where control participants took part in some form of alternate activity with those where the control condition was 'treatment‐as‐usual'. We only presented subgroup analyses where there were at least five studies per subgroup (Richardson 2019), to reduce concerns regarding covariate distributions. Where we presented subgroup analyses, we considered the difference between subgroups to be statistically significant where P < 0.10 (Richardson 2019). We considered all subgroup analyses as exploratory.

Sensitivity analysis

In planned sensitivity analyses we explored:

a) whether the trial of maintenance cognitive stimulation reported by Orrell 2014, where the control group had attended 14 sessions of cognitive stimulation before randomisation, might have an influence on the results of one session per week studies.

b) whether the findings on cognition, pooling different assessment measures, were reflected in the findings for the two most widely used assessment measures, the ADAS‐Cog and the MMSE, for which figures for recognised minimum clinically important differences were available.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADE methods to rate the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low or very low) behind each effect estimate in the review (Guyatt 2011). This rating referred to our level of confidence that the estimate reflected the true effect, taking account of the risk of bias in the included studies, inconsistency between studies, imprecision in the effect estimate, indirectness in addressing our review question and the risk of publication bias. We produced summary of findings tables for cognitive stimulation compared to no treatment to show the effect estimate and the quantity and quality of the supporting evidence for the following outcomes immediately post‐treatment:

cognition

self‐reported QoL

communication and social interaction

self‐reported mood

interviewer/staff‐rated mood

instrumental activities of daily living

behaviour that challenges

In view of the widespread use of group cognitive stimulation, and its specific recommendation in guidelines, we produced an additional table (with the same outcomes) to summarise the effects of group cognitive stimulation considered separately. We prepared the summary of findings tables using the GRADEpro GDT 2015 (gradepro.org).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

From the searches of databases carried out since the previous version of this review was published (Woods 2012), we have identified a total of 5602 records (see Appendix 1; Figure 1). Following removal of duplicates and a first screening by the CDIG information specialist, 1864 records remained which we imported into COVIDENCE as 1853 studies. Further de‐duplication resulted in 1608 studies, of which we excluded 1449 as it was clear from the title and/or abstract that the study did not meet the inclusion criteria.

We then obtained the full texts of the remaining 159 studies and the author team assessed their eligibility for inclusion. Twenty‐two of these studies are ongoing (typically published on trial registries) and we excluded a further 98 studies at this point, leaving 39 studies to be transferred from COVIDENCE to RevMan. At this stage, it became clear that three of the 39 studies were in fact reports of specific aspects of larger studies (Graessel 2011; Orrell 2014), and so we merged these studies with their parent studies. We added five studies included in the previous version of this review which had not been re‐included by the subsequent searches to these 36 studies (Baldelli 1993; Baldelli 2002; Bottino 2005; Spector 2001; Woods 1979). We recognised that some leeway regarding diagnostic criteria had been given in the previous version of the review, where the authors had stated, 'Older studies may be included where the review authors are satisfied that the included population would now be described as having a dementia'. Given the growth of the evidence base, it now appeared timely to exclude the early, small‐scale studies which had described participants as 'disorientated' and having 'significant memory impairment' (Woods 1979); ‘demented/organic' (Wallis 1983); 'moderate to severe Impairment of cognitive functioning' (Baines 1987); and ‘elderly patients with cognitive disturbances’ (Ferrario 1991), predating current diagnostic criteria. Exclusion of these four studies resulted in inclusion of a total of 37 studies in this updated review, compared with 15 studies in the previous review (Woods 2012).

We present full details of the included studies and reasons for exclusion of selected excluded studies in the tables 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. We present selected recent ongoing studies in 'Characteristics of ongoing studies'.

Included studies

We summarise key characteristics of the included studies in Table 4. Overall, the 37 included studies comprised 2766 participants, 1462 in the treatment groups and 1304 in the control groups. The 37 studies were carried out in 17 different countries, from five continents. The largest number of studies came from the UK (9) and Italy (7), with three from Germany and two each from China (Hong Kong), Spain, Portugal and Brazil. There was considerable variation in study sizes, with the mean intervention sample size being 39.5 (SD 39.1) and the mean control sample size being 35.2 (SD 35.3).The smallest study (Bottino 2005) had just 13 participants and the largest, (Orgeta 2015), a total of 356. Eight of the 37 studies had more than 100 participants in total (Alvares‐Pereira 2021; Carbone 2021; Graessel 2011 (at 6 months); Onder 2005; Orgeta 2015; Orrell 2014; Spector 2003; and Young 2019). The included studies varied in many other aspects: (1) participant characteristics; (2) number and duration of cognitive stimulation sessions; (3) activities which defined cognitive stimulation; (4) the activity of the control group; and (5) outcome measures. We will consider these factors in turn.

2. Summary of key characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Intervention/modality | Setting | Frequency (per week) | Duration (weeks) | Total number of sessions | Session length (minutes) |

MMSE Mean (SD) |

Follow‐up? |

Age Mean (SD) |

Relevant sample size intervention/control |

| Ali 2021 | Individual iCST adapted from ‘Making a Difference’ manuals delivered by paid staff or family/friends | Mixed community/supported housing/residential care, UK | 2 | 20 | 40 | 30 | N/A | None | 60.4 (8.2) | 20/20 |

| Alvares‐Pereira 2021 | CST groups using Portugese version of 'Making a Difference' manual | Mixed day‐centre/residential settings, Portugal | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | N/A | None | 83.6 (7.6) | 55/50 |

| Baldelli 1993 | RO group sessions | Institution, Italy | 3 | 12 | 36 | 60 | 20.6 (4.9) | 3‐month | 84.5 (6.4) | 13/10 |

| Baldelli 2002 | RO group sessions | Nursing home, Italy | 5 | 4 | 20 | 60 | 20.7 (3.0) | None | 80.0 (7.4) | 71 /16 |

| Bottino 2005 | ‘Cognitive rehabilitation’ group sessions/carer support group | Outpatients, Brazil | 1 | 20 | 20 | 90 | 22.3 (3.6) | None | 73.7 (6.6) | 6/7 |

| Breuil 1994 | Cognitive stimulation groups | Outpatients, France | 2 | 5 | 10 | 60 | 21.5 | None | 77.1 (7.1) | 29/27 |

| Buschert 2011 | Cognitive stimulation groups | Outpatients, all on AChEIs/memantine, Germany | 1 | 26 | 20 | 120 | 24.9 (1.6) | None | 75.9 (8.1) | 8/7 |

| Capotosto 2017 | CST groups using ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Residential homes, Italy | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 18.2 (3.4) | None | 87.4 (5.4) | 20/19 |

| Carbone 2021 | CST groups using Italian version of 'Making a Difference' manual | Residential homes and day‐centres, Italy | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 20.1 (4.0) | 3‐month follow‐up | 83.6 (8.1) | 123/102 |

| Chapman 2004 | Cognitive‐communication stimulation groups | Outpatients – all on donepezil, USA | 1 | 8 | 8 | 90 | 20.9 (3.6) | 6‐month and 10‐month follow‐up | 76.4 (7.9) | 26/28 |

| Cheung 2019 | Cognitive stimulating play intervention groups | 2 daycare centres, Hong Kong | 1 | 8 | 8 | 45‐60 | (MoCA 7.9 (4.4)) | None | 83.2 (7.2) | 18/12 |

| Coen 2011 | CST Groups using ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Long‐term care, nursing home, Ireland | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 16.9 (5.0) | None | 79.8 (5.6) | 14/13 |

| Cove 2014 | CST Groups using ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Community, UK | 1 | 14 | 14 | 45 | 22.8 (3.4) | None | 77.3 (7.0) | 24/23 |

| Gibbor 2020b | Individual iCST adapted from ‘Making a Difference’ manuals delivered by researchers | Care homes, UK | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 21.7 (3.5) | None | 81.9 (10.3) | 17/16 |

| Graessel 2011 | ‘MAKS’ groups | Nursing homes, Germany | 6 | 52 | 300 | 120 | 14.6 (5.4) | 10‐month follow‐up | 85.1 (5.1) | 71/68 (6 months) 50/46 (12 months) |

| Juarez‐Cedillo 2020 | 'SADEM' cognitive stimulation groups | Outpatients, Mexico | 2 | 48 | 96 | 90 | 22.6 (0.9) | 12‐month follow‐up | 77.7 (8.2) | 39/28 |

| Justo‐Henriques 2022 | Home‐based individual cognitive stimulation delivered by clinical psychologist | Community, Portugal | 1 | 47 | 47 | 45 | 23.2 (3.2) | None | 78.9 (7.5) | 30/29 |

| Kim 2016 | Multi‐domain cognitive stimulation groups | Community – all receiving pharmacotherapy, South Korea | 5 | 26 | 130 | 60 | 18.0 (5.8) | None | 78.5 (1.5) | 32/21 |

| Leroi 2019 | Individual cognitive stimulation delivered by informal carers (CST‐PD) | Community, UK | 2‐3 | 12 | 24‐36 | 30 | N/A | None | Median 75 (range 55‐90) | 31 /30 |

| Lin 2018 | Cognitive stimulation groups | Long‐term care institutions, Taiwan | 1 | 10 | 10 | 50 | 14.9 (3.7) | 3‐month follow‐up | 79.5 (7.7) | 30/32 |

| Lok 2020 | RAM‐based CST groups (using ‘Making a Difference’ themes and structure) | Community ‐ all receiving AChEIs, Turkey | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 16.9 (4.3) | None | Not stated | 30/30 |

| Lopez 2020 | Cognitive stimulation groups | Community (daycare centre) ‐ all receiving AChEIs, Spain | 3 | 26 | 78 | 60 | 17.9 (3.9) | None | 81.9 (5.5) | 10/10 |

| Maci 2012 | Cognitive stimulation and physical activity groups | Community (gymnasium) ‐ all receiving AChEIs/memantine/anti‐depressants, Italy | 5 | 12 | 60 | 120 | 17.8 (2.8) | None | 72.6 (9.5) | 7/7 |

| Mapelli 2013 | Cognitive stimulation groups | Nursing home, Italy | 5 | 8 | 40 | 60 | 19.5 (3.4) | None | 83.7 (4.6) | 10/10 |

| Marinho 2021 | CST groups using Brazilian version of 'Making a Difference' manual | Outpatients ‐ all receiving AChEIs, Brazil | 2 (but both sessions on same day) | 7 | 14 | 45 | N/A | None | 77.8 (8.4) | 23/24 |

| Middelstädt 2016 | NEUROvitalis senseful cognitive stimulation groups | Nursing homes, Germany | 2 | 8 | 16 | 60 | 16.9 (4.5) | 6‐week follow‐up | 86.4 (4.5) | 36/35 |

| Onder 2005 | Individual reality orientation delivered by family carers | Community – all on donepezil, Italy | 3 | 25 | 75 | 30 | 20.1 (3.1) | None | 75.8 (7.1) | 79/77 |

| Orgeta 2015 | Individual cognitive stimulation delivered by informal carers; ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Community, UK | 3 | 25 | 75 | 30 | 21.2 (4.3) | None | 78.2 (7.5) | 180/176 |

| Orrell 2014 | Maintenance cognitive stimulation groups; ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Care homes and community, UK | 1 | 24 | 24 | 45 | 17.8 (5.5) | None | 83.1 (7.6) | 123/113 |

| Paddick 2017 | Cognitive stimulation groups using adapted ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Community, Tanzania | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | Mean Clinical Dementia Rating 1.65 | 8‐week follow‐up (uncontrolled) | Median 80 (IQR 76.5,85.3) | 16/18 |

| Rai 2021 | Individual cognitive stimulation app delivered by informal carers based on 'Making a Difference' manual | Community, UK | 2‐3 | 11 | 22‐33 | 30 | N/A | None | 73.0 (7.7) | 31/30 |

| Requena 2006 | Cognitive stimulation groups using computer‐controlled visual stimuli on TV screen | Community – all on donepezil, Spain | 5 | 52 and 104 | 250 and 500 | 45 | 21.9 (6.3) | None | 77.0 (7.5) | 20/30 |

| Spector 2001 | Cognitive stimulation groups using ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Mixed community & care home, UK | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 13.1 (4.4) | None | 85.7 (6.7) | 21 /14 |

| Spector 2003 | Cognitive stimulation groups using ‘Making a Difference’ manual | Mixed community & care home, UK | 2 | 7 | 14 | 45 | 14.4 (3.8) | None | 85.3 (7.0) | 115/86 |

| Tanaka 2021 | Group exercise and cognitive stimulation | Residential geriatric rehabilitation facility | 2 | 8 | 16 | 45 | 15.5 (5.8) | None | 86.2 (7.8) | 16/15 |

| Tsantali 2017 | Individual cognitive stimulation delivered by psychologists | Community – all receiving AChEIs, Greece | 3 | 16 | 48 | 90 | 23.0 (1.3) | 8‐month follow‐up | 73.7 (5.3) | 17/21 |

| Young 2019 | Cognitive stimulation groups plus Tai Chi (using adapted ‘Making a Difference’ manual) | Community, Hong Kong | 2 | 7 | 14 | 60 | 20.7 (2.3) | None | 80.2 (6.4) | 51/50 |

AChEI: acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor

CST: cognitive stimulation therapy

CST‐PD: cognitive stimulation therapy – Parkinson’s Disease

iCST: individual cognitive stimulation therapy

IQR: interquartile range

MAKS: motor stimulation; activities of daily living; cognitive stimulation; spiritual element

MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination

MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment

N/A: not applicable

RAM: Roy’s adaptation model

RO: reality orientation

SADEM: study on ageing and dementia in Mexico

1) Participant characteristics

The mean or median age of participants was over 80 years in 17 studies and over 70 years in all but one of the 36 studies reporting summary statistics for age. The exception was Ali 2021 where the mean age was 60.4 years, reflecting the more frequent younger onset of dementia in the people with an intellectual disability who participated in this study. The average mean age across the 36 studies was 79.4 years (median 79.7). Across the studies where the range of ages was reported, the lowest age was 50 and the highest 102 years, with most including participants aged 90 years and over.