Abstract:

Extracorporeal life support (ECLS) devices are lifesaving for critically ill patients with multi-organ dysfunction. Despite this, patients supported with ECLS are at high risk for ECLS-related complications, including nosocomial infections, and mortality rates are high in this patient population. The high mortality rates are suspected to be, in part, a result of significantly altered drug disposition by the ECLS circuit, resulting in suboptimal antimicrobial dosing. Cefepime is commonly used in critically ill patients with serious infections. Cefepime dosing is not routinely guided by therapeutic drug monitoring and treatment success is dependent upon the percentage of time of the dosing interval that the drug concentration remains above the minimum inhibitory concentration of the organism. This ex vivo study measured the extraction of cefepime by continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits. Cefepime was studied in four closed-loop CRRT circuit configurations and a single closed-loop ECMO circuit configuration. Circuits were primed with a physiologic human blood–plasma mixture and the drug was dosed to achieve therapeutic concentrations. Serial blood samples were collected over time and concentrations were quantified using validated assays. In ex vivo CRRT experiments, cefepime was rapidly cleared by dialysis, hemofiltration, and hemodiafiltration, with greater than 96% cefepime eliminated from the circuit by 2 hours. In the ECMO circuits, the mean recovery of cefepime was similar in both circuit and standard control. Mean (standard deviation) recovery of cefepime in the ECMO circuits (n = 6) was 39.2% (8.0) at 24 hours. Mean recovery in the standard control (n = 3) at 24 hours was 52.2% (1.5). Cefepime is rapidly cleared by dialysis, hemofiltration, and hemodiafiltration in the CRRT circuit but minimally adsorbed by either the CRRT or ECMO circuits. Dosing adjustments are needed for patients supported with CRRT.

Keywords: cefepime, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement therapy, pharmacology, drug extraction.

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) are extracorporeal life support (ECLS) devices used in patients with refractory organ failure. Although these mechanical support devices can be lifesaving, mortality rates across the age spectrum are high (1–7). The high mortality is suspected to be due, in part, to alterations in drug pharmacokinetics (PK) by the ECLS circuit (8,9). The ECLS circuit affects drug PK via: 1) drug adsorption by components of the circuit; 2) increased volume of distribution due to exogenous fluids used to prime the circuit as well as inflammation and edema triggered by the circuit and underlying critical illness; and 3) direct drug clearance by the hemofilter (10,11).

Cefepime is a fourth-generation cephalosporin commonly used in critically ill patients when serious infections with resistant Gram-negative pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) are known or suspected to be involved. The bactericidal activity of cefepime is dependent upon the percentage of time of the dosing interval that the drug concentration remains above the minimum inhibitory concentration of the organism (12). However, excessive cefepime exposure has been associated with neurotoxicity (13). Cefepime dosing is not routinely guided by therapeutic drug monitoring, primarily due to the lack of widely available bioanalytical assays (14–17). This lack of therapeutic drug monitoring places patients at risk for treatment failure and toxicity, especially in patients on ECLS devices where drug disposition may be impacted.

Ex vivo experiments in which a drug is administered to an isolated circuit have been used to investigate the impact of CRRT (18–30) and ECMO (31–43) on drug disposition. As there is no patient connected to the circuit, any decrease in drug concentration is due to drug degradation or circuit extraction (adsorption or clearance). Adsorption by circuit components is more common with highly lipophilic and highly protein-bound drugs (38,44). In contrast, clearance by the hemofilter is more common with drugs that are hydrophilic and minimally protein bound (45). The extent of extraction also varies based on circuit materials and circuit flow/dialysis rates (46,47). Individual drug-circuit relationships are difficult to predict, however, and rapid technological advances in ECLS circuit design and equipment material over the past two decades have led to the development of newer, more refined, and more biocompatible materials that are constantly evolving, adding further variability to their impact on drug disposition.

This study used CRRT and ECMO ex vivo systems to determine the extent of cefepime removal by the CRRT and ECMO circuits, respectively. Cefepime is minimally protein bound, hydrophilic, and primarily renally cleared, leading to the hypothesis that it will be minimally adsorbed by the ECMO circuit but rapidly cleared by the CRRT circuit. Understanding the impact of ECLS devices on cefepime PK will help improve pharmacotherapy in patients supported with ECLS, ultimately improving the safety and efficacy of cefepime in this vulnerable population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CRRT Circuit Configurations

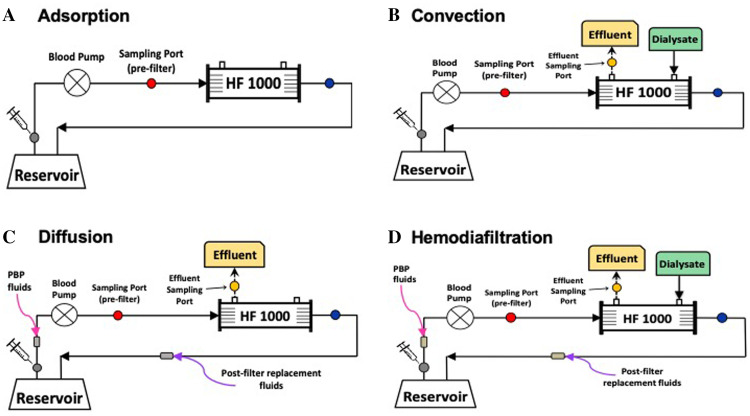

We designed four ex vivo CRRT circuit configurations (Figure 1, Table 1) based on previously described ex vivo models (18,19) to determine cefepime adsorption and transmembrane clearance. Adsorption experiments were performed to determine whether cefepime adsorbed to any CRRT components (i.e., hemofilter, tubing). Convection experiments using continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) circuit configurations were performed to determine cefepime’s sieving coefficient via convection. Diffusion experiments using continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD) circuit configurations were performed to determine cefepime’s saturation coefficient via diffusion. Finally, we performed hemodiafiltration experiments using continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) circuit configurations for two major reasons: 1) Convection and diffusion are independent processes and not necessarily additive, and 2) CVVHDF is the modality of choice for critically ill patients at our institutions. For all experiments, urea (ScienceCompany, Lakewood, CO) was added as a control solute as it is a stable molecule, freely filtered, and is not known to adsorb to CRRT systems (19). Each of the four experimental circuit configurations was replicated in triplicate and each experiment lasted 8 hours.

Figure 1.

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) ex vivo circuit configurations: (A) This circuit configuration constituted a closed system. As a result, any decrease in drug concentration could only be due to adsorption to the CRRT circuit components or drug degradation. (B) A continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) circuit to determine clearance by hemofiltration. Pre- and post-filter replacement fluids were used to maintain a constant volume in the circuit. (C) A continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD) circuit to determine clearance by dialysis. Dialysate flows countercurrent to the blood and drains into a separate bag (effluent). (D) A continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) circuit to determine drug clearance by hemodiafiltration. Pre- and post-filter replacement fluids were used to maintain a constant volume in the circuit.

Table 1.

ECLS circuit components.

| Circuit Type | Component | Manufacturer | Model | Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRRT | System | Baxter | Prismaflex™ | N/A |

| Hemofilter | Baxter | HF1000, (1.1 m2) | Polyarylethersulfone hollow fibers, plasticized polyvinyl chloride tubing | |

| TherMax Bag | Baxter | TherMax Blood Warmer Disposable, 27 mL | Polyurethane | |

| Reservoir | Baxter | EXACTAMIX EVA, 500 mL | Ethylene vinyl acetate | |

| System | Baxter | Prismaflex™ | N/A | |

| ECMO | Oxygenator | Maquet | Quadrox-iD Adult | Polymethylpentane hollow fibers with Softline* coating |

| Pump | Maquet | Rotaflow RF-32 Centrifugal Pump | Polycarbonate with Bioline† coating | |

| Tubing | LivaNova | Smart Perfusion Pack, 3/8″ diameter | Polyvinyl chloride with Smart-X‡ coating | |

| Cannula | Medtronic | DLP™ One-Piece Pediatric Arterial Cannnula, 10 Fr | Polyvinyl chloride |

CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; ECLS, extracorporeal life support; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

*Softline coating: heparin free biopassive polymer; †Bioline coating: heparin + recombinant human albumin; ‡Smart-X coating: Tribloc Copolymer (Polycaprolactone-Polydimethylsiloxane-Polycaprolactone) integrated into plastic.

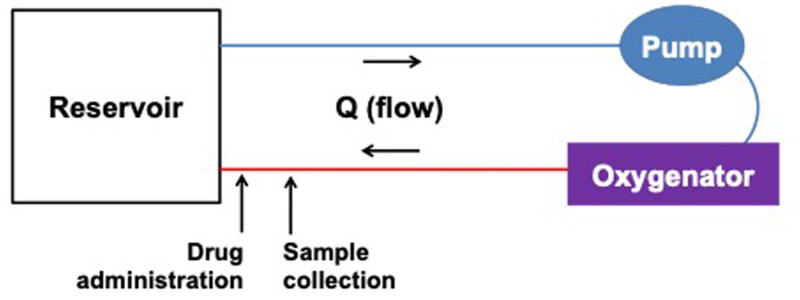

ECMO Circuit Configuration

Circuits were assembled to determine the extent of adsorption by circuit components and consisted of tubing, a pump, an oxygenator, and a cannula (Table 1, Figure 2). ECMO circuit experiments were replicated three times and each experiment lasted 24 hours.

Figure 2.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) ex vivo circuit configuration.

CRRT Circuit Setup

The CRRT circuit was primed with ∼500 mL of a human blood-crystalloid mixture created to simulate the in vivo environment (Table 2). The circuit was completed using a 500-mL EXACTAMIX (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) bag as a reservoir. The blood reservoir was continuously stirred using an orbital shaker. Reservoir temperature was maintained at 37°C using a digitally controlled heating pad. Circuit pH was continuously monitored using an in-line blood gas monitoring tool (CDI® Blood Parameter Monitoring System 500, Terumo Cardiovascular, Ann Arbor, MI) that connected the return line (blue lumen) to the reservoir bag. Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (THAM®, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was intermittently added to the system to maintain physiologic pH (7.2–7.5). Circuits were run using the following prescriptions: 1) Adsorption circuits: blood flow rate (Qb) 100 mL/min, ultrafiltration (UF) rate 0 mL/h to maintain a constant volume in the extracorporeal system; 2) CVVH circuits: blood flow rate 80 mL/min, pre-blood pump (PBP) replacement fluid rate 600 mL/h, post-filter replacement fluid rate 200 mL/h, UF rate 0 mL/h, effluent dose 800 mL/h; 3) CVVHD circuits: blood flow rate 80 mL/min, dialysate rate (Qd) 800 mL/h; 4) CVVHDF circuits: blood flow rate 80 mL/min, dialysate rate 400 mL/h, PBP replacement fluid rate 300 mL/h, post-filter replacement fluid rate 100 mL/h, UF rate was 0 mL/h, effluent dose 800 mL/h.

Table 2.

ECLS circuit prime solutions.

| Component | Amount | |

|---|---|---|

| CRRT | ECMO | |

| Plasma-Lyte A*† | – | 300–400 mL |

| PrismaSol® BGK 0/2.5*‡ | 50–100 mL | – |

| Human red blood cells (adenine saline added leukocytes reduced) | 300 mL | 400–500 mL |

| Thawed human plasma (frozen within 24 hours after phlebotomy) | 125 mL | 150 mL |

| Albumin 25% | 6.25 g | 12.5 g |

| Sodium bicarbonate 8.4% | 7 mEq | 7 mEq |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane§ | 1.5–2.0 g | 2 g |

| Calcium gluconate 10% | – | 650 mg |

| Calcium chloride 10% | 180 mg | – |

| Heparin | 350 units | 500 units |

ECLS, extracorporeal life support.

*Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL; †mEq/L: Na+ 140, K+ 0, Cl− 109, HCO3− 32, Ca2+ 2.5, Mg2+ 1.5, lactate 3; dextrose 100 mg/dL; 292 mOsmol/L; ‡mEq/L: Na+ 140, K+ 5, Cl− 98, Mg2+ 3, acetate 27, gluconate 23, lactate 0, dextrose 0; 294 mOsmol/L; §THAM®, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA.

ECMO Circuit Setup

The ECMO circuit was primed with ∼1 L of the human blood–crystalloid mixture (Table 2). The circuit was completed using a double-spiked intravenous (IV) bag as a reservoir, with operating volume maintained to prevent air entrainment into circuit. Temperature was maintained at 37°C using an ECMO Water Heater (Cincinnati Sub-Zero, Cincinnati, OH) via the Quadrox-iD integrated heat exchanger. Physiologic pH (7.2–7.5) was maintained by adding additional sodium bicarbonate, THAM®, and/or carbon dioxide via the sweep gas. The reservoir return was directed into the IV bag via a 10 French arterial cannula (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). Flows were maintained at 1 L/min and were measured post-oxygenator using an HT110 bypass flow meter with H8XL flowsensor (Transonic, Davis, CA).

Controls

Three control samples were analyzed to determine the amount of natural drug degradation over time. The human blood-crystalloid mixture (Table 2) was added to polypropylene centrifuge tubes (229,426, CELLTREAT, Pepperell, MA). Blood was drawn from the primed ECMO circuit after 5 minutes of circulation but before cefepime administration, ensuring that the control sample medium was identical to the composition of the circuit medium. Control samples were maintained at 37°C for the duration of the experiment.

Observed cefepime degradation in the controls prompted additional post hoc experiments to assess the source of drug loss. In addition to the experiments in polypropylene centrifuge tubes above, three experimental conditions were studied: 1) Blood prime mixture in silanized glass to determine the extent of adsorption by the polypropylene; 2) Blood prime mixture in polypropylene centrifuge tubes protected from light to determine the impact of light on drug degradation; and 3) Crystalloid prime solution in polypropylene centrifuge tubes to determine the extent of drug metabolism in blood. The blood prime controls were filled with blood prime solution from the ECMO circuits (Table 2). The crystalloid prime controls were filled with the following crystalloid solution: Plasma-Lyte A (250 mL), heparin (1.75 U), sodium bicarbonate (3.5 mEq), calcium gluconate (1 g), and 25% albumin (6.25 g). All of the conditions were repeated in triplicate.

Drug

Cefepime was provided by our institutions’ pharmacies. The drug was added to the ex vivo circuits to achieve peak plasma concentrations of 140–170 mg/L to match peak cefepime plasma concentrations typically observed in the clinical setting following recommended dosing guidelines (48–50). Cefepime was dosed in the control samples to achieve a comparable concentration to the CRRT and ECMO circuits.

Drug Administration and Sample Collection

After the CRRT circuit was primed with the blood mixture and connected to the reservoir, the blood recirculated through the CRRT circuit for 30–40 minutes to allow for uniform coating of the extracorporeal system. Cefepime was then administered via the PBP arterial sampling port located just downstream from the reservoir bag at time = 0. Sample collection times were 1, 5, 15, and 30 minutes, and 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 hours after cefepime administration. Cefepime and urea concentrations were determined from 1.5 mL blood samples obtained simultaneously from the pre-filter (red) sampling port, and 1.5 mL effluent samples from the post-filter (yellow) effluent sampling port of the circuit (Figure 1).

After the ECMO circuit was primed and connected to the reservoir, cefepime was introduced into the system at time = 0 via a three-way stopcock located just before the reservoir bag and downstream of the sampling port on the arterial limb of the circuit. Samples were collected at 1, 5, 15, and 30 minutes and 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 10, and 24 hours after cefepime administration. Blood samples (1.5 mL) were collected via a second three-way stopcock located just upstream of the drug administration port on the arterial limb of the circuit (Figure 2).

Samples from both the CRRT and ECMO circuits were processed and stored as follows: 1) Effluent samples (if applicable) were directly transferred to cryovials (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA); 2) Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 3,000 g, 4°C for 10 minutes; 3) Separated plasma was transferred to cryovials; 4) All samples were frozen at −20°C for < 72 hours, then stored at −80°C until analysis.

Analysis

Drug concentrations were determined using assays developed and validated according to FDA guidance (51). CRRT plasma and effluent concentrations were measured in the laboratory of Douglas Fish (University of Colorado, Aurora CO) using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet (UV) detection according to previously published methods (52,53). The assay was validated in both plasma and effluent, with standard curves achieving coefficients of determination (r2) of >.998 and coefficients of variation being <5.1% for concentrations across the range of the standard curves (1.0–250 mg/L) for both fluids. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for cefepime in both plasma and effluent samples was 1.0 mg/L. Intraday and interday precision (%CV) for plasma cefepime samples ranged from 1.9% to 4.3% and 2.7% to 5.1%, respectively, across the range of the standard curve. Intraday and interday precision (%CV) for effluent samples ranged from .4% to 2.4% and .6% to 2.9%, respectively. For ECMO experiments, cefepime concentrations were measured at OpAns Laboratory (Durham, NC) using high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). The assay was validated with standard curves achieving coefficients of determination (r2) of >.997 and coefficients of variation being <4.6% for concentrations across the range of the standard curves (.1–100 mg/L). The LLOQ for cefepime was .1 mg/L. The intraday precision ranged from 2.4% to 2.5% and the interday precision ranged from 3.0% to 4.6%.

Drug recovery in circuits and controls was calculated at each sample time using the following equation:

where Ct is the concentration at time t and Ci is the initial concentration measured at time = 1 minute for the control and CRRT samples. In the ECMO circuits, there was an initial delay in drug mixing. Therefore, the maximum concentration of the first four time points was used as Ci. Data are reported as the mean and 95% confidence interval. Using paired plasma and effluent samples from six time points (t = 15 minutes through t = 4 hours), sieving and saturation coefficients as well as transmembrane clearances were calculated for the CVVH, CVVHD, and CVVHDF experiments using the following equations:

where Sc is the sieving coefficient, Cuf is the ultrafiltrate concentration, CP is the plasma concentration, Sa is the saturation coefficient, Cd is dialysate concentration, and Ceff is the effluent concentration. Quf, Qd, and Qeff are the rates of UF, dialysis, and effluent, respectively. Qeff is the ultrafiltrate plus the dialysate flow rates (Quf+Qd). CLCVVH, CLCVVHD, and CLCVVHDF represent the transmembrane clearances for the CVVH and CVVHD, and CVVHDF experiments, respectively. Sa(HDF) is the saturation coefficient for hemodiafiltration, calculated for the CVVHDF experiments. Data are reported as the mean (standard deviation [SD]).

Statistics

A two-sample t test was used to compare the mean recovery of ECMO and CRRT circuit replicates to the mean recovery in the standard control. We compared all four control conditions using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bartlett’s test to confirm equal variance and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

CRRT Circuits

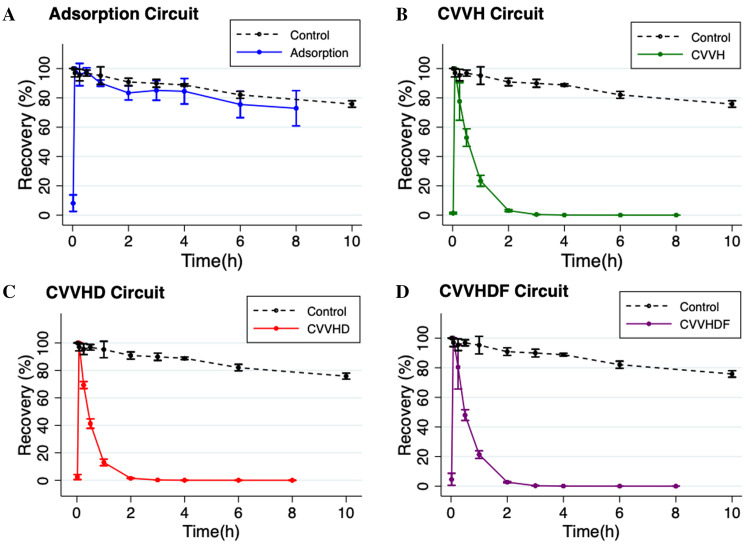

Cefepime was rapidly cleared by both diffusion (i.e., dialysis) and convection (i.e., hemofiltration) in ex vivo CRRT circuits with greater than 96% cefepime extraction by 2 hours (Figure 3). By 30 minutes, mean recovery in the standard control was significantly greater than mean recovery in the CVVH (n = 3; p = .0003), CVVHD (n = 3; p = <.0001), and CVVHDF (n = 3; p = <.0001) circuits. The mean (SD) recovery of cefepime in the adsorption circuits (n = 3) was not statistically different compared to the recovery in the standard control (p = .68 at 30 minutes and p = .29 at 6 hours). Table 3 summarizes the mean (SD) Sa, Sc, and CL values of cefepime for each ex vivo CRRT modality. Appendix Table 1 lists raw cefepime concentration data by CRRT circuit type.

Figure 3.

Cefepime recovery by ex vivo continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) circuit configuration, depicted as %-drug recovered over 8 hours for each circuit configuration. Values are mean; error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Table 3.

Ex vivo saturation (Sa) and sieving (Sc) coefficients, and transmembrane clearance (CLTM, mL/min) of cefepime in a human blood-crystalloid solution for each CRRT modality using a polyarylethersulfone (HF-1000) membrane.

| CRRT Modality | Sa or Sc Coefficients | CLTM (mL/min) |

|---|---|---|

| CVVH | 1.20 (.08)† | 15.96 (1.06) |

| CVVHD | 1.29 (.09)* | 17.23 (1.24) |

| CVVHDF | 1.17 (.07)* | 15.63 (.94) |

All values are presented as mean (SD) and were calculated using sample times from 15 minutes to 4 hours. *Sa = saturation coefficient. †Sc = sieving coefficient. CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; CVVH = continuous venovenous hemofiltration; CVVHD = continuous venovenous hemodialysis; CVVHDF = continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration.

ECMO Circuits

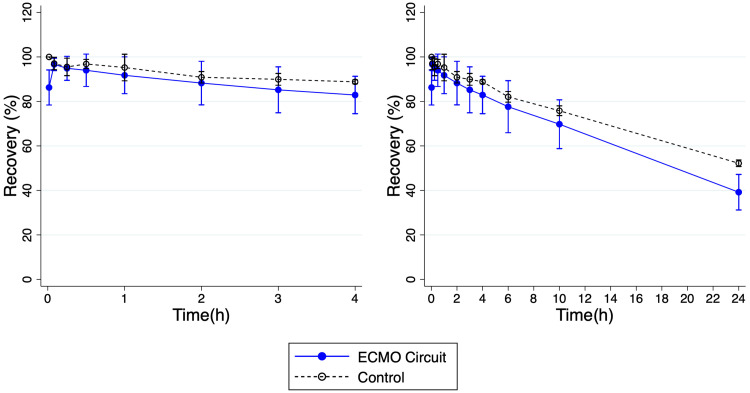

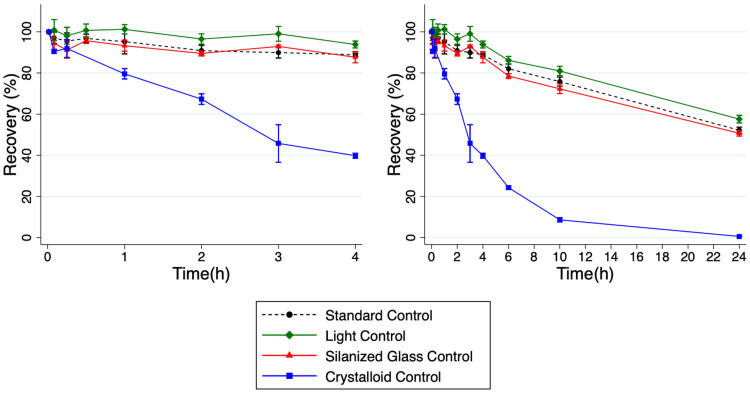

Due to circuit failures, a total of six ECMO circuit replicates were ultimately performed. The mean recovery of cefepime was similar in both circuit and standard control. Mean (SD) recovery of cefepime in the ECMO circuits (n = 6) was 82.9% (8.4) at 4 hours and 39.2% (8.0) at 24 hours. Mean recovery in the standard control (n = 3) at 4 hours was 88.8% (.9) and 52.2% (1.5) at 24 hours. Mean recovery in the standard control was not significantly different compared to recovery in the ECMO circuit at 4 hours (p = .28) but was significantly different compared to recovery in the ECMO circuit at 24 hours (p = .03) (Figures 4 and 5). See Appendix Table 3 for cefepime concentration data from control experiments. Cefepime concentration data for ECMO ex vivo experiments are shown in Appendix Table 2.

Figure 4.

Cefepime recovery from ex vivo extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuit depicted as %-drug recovered over 24 hours. Left panel shows recovery over the first 4 hours and right panel shows recovery over 24 hours. Values are mean; error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Cefepime recovery under four experimental control conditions depicted as %-drug recovered over 24 hours. Left panel shows recovery over the first 4 hours and right panel shows recovery over 24 hours. Values are mean; error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Control Experiments

Drug loss was more pronounced in the crystalloid prime samples compared with the other control conditions. At 24 hours, the standard control, light control, and silanized glass control, had mean recoveries of 52.2%, 50.7% (1.3), and 57.6% (1.8), respectively. The crystalloid prime control saw much lower mean recovery at .61% (.04). Significant differences were present (difference, adjusted p value) between the crystalloid prime control and the standard control (51.6%, p = <.0001), light control (50.1%, p= <.0001), and silanized glass control (57.0%, p = <.0001) at 24 hours. Significant differences were also present between the silanized glass control and the standard control (−5.39%, p = .007) and light control (6.9%, p = .001).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the degree of cefepime extraction by the ex vivo ECMO and CRRT circuits. Although drug loss was observed in the adsorption experiments, the minimal difference between the adsorption circuits and the controls suggests that adsorption played a nominal role in either of the ECLS circuits. In CRRT, cefepime was rapidly cleared by both diffusion (i.e., dialysis) during CVVHD (mean Sa of 1.29) and convection (i.e., hemofiltration) during CVVH (mean Sc of 1.20), indicating that the drug passes freely through the HF-1000 hemofilter membrane. Our findings are similar to prior ex vivo CRRT studies of cefepime using different hemofilter membranes (54) and are consistent with our hypothesis that the physiochemical properties of cefepime would lead to minimal circuit-drug adsorption but rapid clearance by hemodiafiltration.

In this study, CVVHD provided the highest clearance of cefepime compared to CVVH and CVVHDF. This is not unexpected given small solute clearance (e.g., cefepime) is highest with diffusion and lowest with convection, whereas large solute clearance is highest with convection and lowest with diffusion (55). In addition, high rates of hemofiltration (or convection, as can be seen in CVVH and CVVHDF) typically require replacement fluid to prevent clotting and preserve the hemofilter’s half-life. The replacement fluid acts as a pre-dilutional fluid which also decreases the clearance of small molecular weight solutes. Although a few clinical and in vitro studies have described the PK of cefepime during CRRT (52,54,56–60), this is the first study evaluating the extracorporeal removal of cefepime by CVVH, CVVHD, and CVVHDF under operational settings for the HF-1000 filter. These results provide important insights into circuit-cefepime interactions that can affect bedside dosing recommendations.

While we observed minimal interaction between cefepime and the ECMO circuit, it is worth noting that there was significant adsorption present at 24 hours. Although statistically significant, this degree of adsorption is unlikely to be clinically significant given that: 1) There was little to no adsorption by the ECMO circuit at the other experimental time points, and 2) There was only a small quantitative difference in recovery between the standard control and experimental samples at 24 hours.

Our control experiments demonstrated a decline in cefepime recovery over time in all of the experimental conditions. Cefepime is known to undergo non-enzymatic degradation in plasma in vitro with accelerated degradation rates at temperatures >4°C (61). We surmised that because our experiments were performed at 37°C, the decline in cefepime concentrations over time was likely the result of this temperature-dependent degradation. Interestingly, there was more precipitous and significant cefepime degradation in the crystalloid prime controls relative to the other control conditions. Mehta et al. also observed higher adsorption in crystalloid primed circuits relative to blood-primed circuited for a number of common drugs (42). It can thus be assumed that some component of the blood prime is offering protection against cefepime degradation. The exact mechanism of protection, however, is unclear.

Our study is not without limitations. Due to a miscalculation in dose-conversion (i.e., targeting a goal peak concentration of mg/dL rather than mg/L), cefepime concentrations were 10-fold higher in the ex vivo CRRT experiments. Although this could theoretically result in saturation of the circuit and artificially decrease apparent adsorption, we do not believe this occurred based on the fact that adsorption was comparable between CRRT circuits with the higher concentrations and ECMO circuits with a physiologic concentration. Second, due to constraints with the CRRT ex vivo system, CRRT experiments were conducted for a shorter duration than ECMO experiments (8 hours vs. 24 hours). We do not believe the shorter CRRT experiment duration significantly impacted our results because 1) The presence or absence of substantial adsorption should be observed within the first few hours after dosing (25,62–64), and 2) Cefepime was fully cleared within two hours of dosing. Additionally, we only evaluated one type of hemofilter membrane (i.e., HF-1000) in the ex vivo CRRT experiments, and it is well known that the degree of drug extraction can vary substantially based on the type (i.e., composition) of hemofilter (24,25,55). Finally, we used very similar flows (i.e., Qb and Quf) for all experiments. This most likely did not impact our results given the rapidity and extent to which cefepime was removed from the CRRT system.

CONCLUSION

Cefepime is rapidly cleared by dialysis, hemofiltration, and hemodiafiltration in the CRRT circuit but minimally adsorbed by either the CRRT or ECMO circuits. Dosing adjustments are needed for patients supported with CRRT. Optimal dosing regimens can be predicted by incorporating ex vivo ECLS data into physiological-based PK models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Lizanne Meszaros and the Duke Clinical Pediatric Laboratory for their time and resources, as well as Marlina Roberson and the Duke Inpatient Dialysis Unit for their technical expertise.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2T32HL105321), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R01HD097775), and the Thrasher Research Fund.

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to report for the present study. Danielle J. Green receives support for critical care research from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2T32HL105321). Kevin M. Watt receives support for pediatric research from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD097775, R21HD104412). Adam R. Bensimhon receives support for pediatric research from the Thrasher Research Fund (www.thrasherresearch.org) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (4T32HD043029).

Appendix Table 1.

CRRT cefepime concentrations (mg/L).

| Time | Adsorption Circuit – Blood | Adsorption Circuit - Effluent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |

| 1 minutes | 153.47 | 147.29 | 27.97 | - | - | - |

| 5 minutes | 1239.2 | 1421.42 | 1630.36 | - | - | - |

| 15 minutes | 1250.06 | 1415.95 | 1420.55 | - | - | - |

| 30 minutes | 1245.77 | 1387.38 | 1549.65 | - | - | - |

| 1 hours | 1116.04 | 1310.99 | 1433.2 | - | - | - |

| 2 hours | 1096.06 | 1179.91 | 1284.22 | - | - | - |

| 3 hours | 1011.54 | 1319.9 | 1318.12 | - | - | - |

| 4 hours | 947.57 | 1331.76 | 1358.76 | - | - | - |

| 6 hours | 828.63 | 1207.05 | 1219.49 | - | - | - |

| 8 hours | 757.12 | 1210.25 | 1180.78 | - | - | - |

| Time | CVVH Circuit - Blood | CVVH Circuit - Effluent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |

| 1 minutes | 6.15 | 17.6 | 14.3 | 958.85 | 1316.37 | 1915.03 |

| 5 minutes | 803.29 | 1047.66 | 868.99 | 1256.3 | 1382.21 | 1319.75 |

| 15 minutes | 618.16 | 682.18 | 788.55 | 1077.09 | 1030.77 | 914.02 |

| 30 minutes | 467.21 | 485.9 | 469.8 | 670.89 | 670.14 | 737.56 |

| 1 hours | 182.96 | 209.88 | 239.03 | 234.22 | 238.97 | 302.5 |

| 2 hours | 21.29 | 28.78 | 34.04 | 28.65 | 30.58 | 22.05 |

| 3 hours | 3.06 | 4.2 | 5.05 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 5.01 |

| 4 hours | .64 | .76 | .95 | .48 | .85 | .89 |

| 6 hours | .19 | .23 | .29 | 0 | .72 | .24 |

| 8 hours | .19 | .2 | .2 | 0 | .85 | 0 |

| Time | CVVHD Circuit - Blood | CVVHD Circuit - Effluent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |

| 1 minutes | 59.26 | 16.15 | 14.6 | 733.51 | 558.46 | 905.38 |

| 5 minutes | 1315.53 | 1329.55 | 1012.87 | 1158.99 | 2450.07 | 1291.2 |

| 15 minutes | 873.8 | 945.24 | 713.22 | 1064.31 | 1250.14 | 1114.5 |

| 30 minutes | 594.55 | 522.37 | 397.69 | 640.44 | 805.61 | 445.04 |

| 1 hours | 161.63 | 146.88 | 158.83 | 230.25 | 220.59 | 193.02 |

| 2 hours | 16.77 | 18.2 | 16.99 | 26.13 | 26.87 | 18.87 |

| 3 hours | 2.55 | 2.56 | 2.22 | 2.12 | 3.36 | 2.37 |

| 4 hours | .52 | .59 | .42 | .43 | .51 | .9 |

| 6 hours | .16 | .28 | .41 | .45 | .41 | .31 |

| 8 hours | .17 | .25 | .29 | .11 | .11 | .21 |

| Time | CVVHDF Circuit - Blood | CVVHDF Circuit – Effluent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |

| 1 minutes | 17.95 | 94.45 | 24.19 | 1341.68 | 1263.93 | 4323.47 |

| 5 minutes | 875.2 | 1015.27 | 997.15 | 1319.28 | 1330.65 | 1333.22 |

| 15 minutes | 845.93 | 690.16 | 762.91 | 1195.69 | 1160.53 | 1142.33 |

| 30 minutes | 455.74 | 459.11 | 464.73 | 725.43 | 767.75 | 697.37 |

| 1 hours | 208.03 | 220.31 | 185.79 | 268.5 | 216.07 | 255.46 |

| 2 hours | 25.89 | 30.39 | 22.05 | 25.37 | 29.59 | 24.26 |

| 3 hours | 3.19 | 3.85 | 2.48 | 2.26 | 3.79 | 2.69 |

| 4 hours | .56 | .6 | .37 | .31 | .41 | .38 |

| 6 hours | .32 | .12 | .11 | .1 | 0 | .12 |

| 8 hours | .3 | .11 | .1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Appendix Table 2.

ECMO cefepime concentrations (mg/L).

| Time | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 4 | Run 5 | Run 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 minutes | 196.95034 | 111.08942 | 168.76169 | 262.70758 | 103.34327 | 93.99746 |

| 5 minutes | 221.12605 | 132.40337 | 174.75852 | 206.9969 | 107.72754 | 112.60044 |

| 15 minutes | 229.14542 | 136.65941 | 163.75908 | 178.61292 | 113.00717 | 110.55926 |

| 30 minutes | 228.80454 | 139.92037 | 152.94846 | 172.18674 | 105.61809 | 120.51624 |

| 1 hours | 216.22497 | 139.72196 | 152.81494 | 159.79767 | 106.19672 | 117.70585 |

| 2 hours | 205.78023 | 136.5953 | 146.25552 | 146.93519 | 103.44411 | 115.5767 |

| 3 hours | 208.4848 | 123.59014 | 145.51425 | 141.60737 | 286.61903 | 114.57281 |

| 4 hours | 196.645 | 122.03676 | 136.45963 | 141.43888 | 97.38119 | 110.59217 |

| 6 hours | 182.37148 | 117.32404 | 115.85707 | 131.23024 | 87.40895 | 114.77545 |

| 10 hours | 156.82844 | 95.73425 | 111.10991 | 113.99033 | 85.54847 | 105.28467 |

| 24 hours | 90.78882 | 42.03206 | 75.00834 | 60.11575 | 51.49357 | 57.85821 |

Appendix Table 3.

Cefepime control concentrations (mg/L).

| Time | Standard Control | Silanized Glass Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |

| 1 minutes | 192.86238 | 205.55319 | 212.05363 | 191.89105 | 172.15995 | 168.65082 |

| 5 minutes | 191.40225 | 201.45249 | 199.13072 | 195.62468 | 181.33379 | 160.55144 |

| 15 minutes | 192.93888 | 192.25701 | 197.17461 | 179.15311 | 173.01319 | 169.34122 |

| 30 minutes | 189.24266 | 201.2972 | 200.28896 | 186.8495 | 174.44978 | 174.52997 |

| 1 hours | 196.50095 | 192.23312 | 191.51791 | 189.56502 | 174.78698 | 174.31031 |

| 2 hours | 170.63481 | 192.3734 | 191.95817 | 179.85811 | 167.04442 | 166.56287 |

| 3 hours | 178.29631 | 185.31742 | 184.84808 | 182.20511 | 173.178 | 171.39609 |

| 4 hours | 173.21323 | 182.0862 | 186.75904 | 177.23313 | 164.69179 | 157.85155 |

| 6 hours | 162.63344 | 169.18322 | 168.69401 | 161.07302 | 150.02695 | 147.35349 |

| 10 hours | 151.06032 | 153.67052 | 157.68122 | 150.4807 | 141.04283 | 139.32183 |

| 24 hours | 103.25456 | 107.75019 | 107.39349 | 106.90541 | 102.10431 | 97.3979 |

| Time | Light Protected Control | Crystalloid Prime Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |

| 1 minutes | 196.97845 | 188.54589 | 192.27326 | 101.34747 | 99.26823 | 96.59257 |

| 5 minutes | 190.15917 | 179.94511 | 175.32738 | 92.18619 | 88.83282 | 87.88802 |

| 15 minutes | 182.46991 | 177.55372 | 166.75782 | 95.15595 | 94.2512 | 83.94168 |

| 30 minutes | 191.79255 | 179.25861 | 182.11011 | 940.29744* | 962.45564* | 838.87809* |

| 1 hours | 188.44459 | 176.87172 | 173.7968 | 78.29515 | 81.61207 | 76.59731 |

| 2 hours | 175.92757 | 171.28249 | 169.96549 | 65.6745 | 66.58957 | 67.59806 |

| 3 hours | 184.56155 | 174.45904 | 177.90815 | 48.4884 | 53.33587 | 34.59568 |

| 4 hours | 175.6372 | 168.4602 | 162.4127 | 41.47848 | 39.80336 | 37.19439 |

| 6 hours | 153.77383 | 150.7026 | 149.35987 | 23.86695 | 24.3284 | 24.0626 |

| 10 hours | 143.86192 | 140.01071 | 133.98007 | 9.3895 | 9.15086 | 7.26393 |

| 24 hours | 101.11173 | 97.37865 | 94.60944 | .58595 | .58243 | .63483 |

*Dropped from final analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nasr VG, Raman L, Barbaro RP, et al. Highlights from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry: 2006-2017. ASAIO J. 2019;65:537–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lee H-J, Son Y-J. Factors associated with in-hospital mortality after continuous renal replacement therapy for critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prowle JR, Bellomo R. Continuous renal replacement therapy: Recent advances and future research. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortina G, McRae R, Hoq M, et al. . Mortality of critically ill children requiring continuous renal replacement therapy: Effect of fluid overload, underlying disease, and timing of initiation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20:314–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci Z, Goldstein SL. Pediatric continuous renal replacement therapy. Contrib Nephrol. 2016;187:121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes LW, Oster RA, Tofil NM, et al. . Outcomes of critically ill children requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. J Crit Care. 2009;24:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin BR, Liu KD, Teixeira JP. Critical care nephrology: core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75:435–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherwin J, Heath T, Watt K. Pharmacokinetics and dosing of anti-infective drugs in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A review of the current literature. Clin Ther. 2016;38:1976–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolin TD, Aronoff GR, Fissell WH, et al. . Pharmacokinetic assessment in patients receiving continuous RRT: Perspectives from the Kidney Health Initiative. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shekar K, Fraser JF, Smith MT, et al. . Pharmacokinetic changes in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care. 2012;27:741.e9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Drug dosing during continuous renal replacement therapy. Semin Dial. 2009;22:185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barradell L, Bryson H. Cefepime: A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1994;47:471–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne LE, Gagnon DJ, Riker RR, et al. . Cefepime-induced neurotoxicity: A systematic review. Crit Care. 2017;21:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdulla A, van den Broek P, Ewoldt TMJ, et al. . Barriers and facilitators in the clinical implementation of beta-lactam therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill patients: a critical review. Ther Drug Monit. 2022;44:112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdul-Aziz MH, Alffenaar JWC, Bassetti M, et al. . Antimicrobial therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill adult patients: A position paper. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1127–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fratoni AJ, Nicolau DP, Kuti JL. A guide to therapeutic drug monitoring of β-lactam antibiotics. Pharmacotherapy. 2021;41:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang SM, Infante S, Abdi Pour A. Drug dosing considerations in critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020;8:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi G, Gomersall CD, Lipman J, et al. . The effect of adsorption, filter material and point of dilution on antibiotic elimination by haemofiltration an in vitro study of levofloxacin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaijamorn W, Shaw AR, Lewis SJ, et al. . Ex vivo Ceftolozane/Tazobactam clearance during continuous renal replacement therapy. Blood Purif. 2017;44:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baud FJ, Houzé P, Carli P, et al. . Alteration of the pharmacokinetics of aminoglycosides by adsorption in a filter during continuous renal replacement therapy. An in vitro assessment. Therapie. 2021;76:415–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis SJ, Switaj LA, Mueller BA. Tedizolid adsorption and transmembrane clearance during in vitro continuous renal replacement therapy. Blood Purif. 2015;40:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biagi M, Butler DXT, Tan X, et al. . Pharmacokinetics and dialytic clearance of isavuconazole during in vitro and in vivo continuous renal replacement. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e01085–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baud FJ, Jullien V, Abarou T, et al. . Elimination of fluconazole during continuous renal replacement therapy. An in vitro assessment. Int J Artif Organs. 2021;44:453–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onichimowski D, Ziółkowski H, Nosek K, et al. . Comparison of adsorption of selected antibiotics on the filters in continuous renal replacement therapy circuits: In vitro studies. J Artif Organs. 2020;23:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onichimowski D, Nosek K, Ziółkowski H, et al. . Adsorption of vancomycin, gentamycin, ciprofloxacin and tygecycline on the filters in continuous renal replacement therapy circuits: in full blood in vitro study. J Artif Organs. 2020;24:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sartori M, Loregian A, Pagni S, et al. . Kinetics of linezolid in continuous renal replacement therapy: An in vitro study. Ther Drug Monit. 2016;38:579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baud FJ, Houzé P, Raphalen J-H, et al. . Diafiltration flowrate is a determinant of the extent of adsorption of amikacin in renal replacement therapy using the ST150®-AN69 filter: An in vitro study. Int J Artif Organs. 2020;43:758–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrannini M, Niscola P, Falcone C, et al. . Drastic reduction of piperacillin-tazobactam concentrations in an in-vitro model of continuous venovenous hemofiltration: Proposal of an innovative modality of administration to maintain them at constant concentration. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2014;11:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar A, Mann HJ, Keshtgarpour M, et al. . In vitro characterization of oritavancin clearance from human blood by low-flux, high-flux, and continuous renal replacement therapy dialyzers. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34:1067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baud FJ, Jullien V, Secrétan P-H, et al. . Are we correctly treating invasive candidiasis under continuous renal replacement therapy with echinocandins? Preliminary in vitro assessment. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40:100640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahsman MJ, Hanekamp M, Wildschut ED, et al. . Population pharmacokinetics of midazolam and its metabolites during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:407–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harthan AA, Buckley KW, Heger ML, et al. Medication Adsorption into Contemporary Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenator Circuits. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:288–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Vorst MMJ, Wildschut E, Houmes RJ, et al. . Evaluation of furosemide regimens in neonates treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2006;10:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahsman MJ, Wildschut ED, Tibboel D, et al. . Pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime and desacetylcefotaxime in infants during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1734–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Mcdonald CI, et al. . Sequestration of drugs in the circuit may lead to therapeutic failure during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2012;16:R194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wildschut ED, Ahsman MJ, Allegaert K, et al. . Determinants of drug absorption in different ECMO circuits. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watt KM, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Williams DC, et al. . Antifungal extraction by the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2017;49:150–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Mcdonald CI, et al. . Protein-bound drugs are prone to sequestration in the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit: Results from an ex vivo study. Crit Care. 2015;19:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemaitre F, Hasni N, Leprince P, et al. . Propofol, midazolam, vancomycin and cyclosporine therapeutic drug monitoring in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuits primed with whole human blood. Crit Care. 2015;19:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of slow-acting antirheumatic drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;25:392–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulla H, Lawson G, von Anrep C, et al. . In vitro evaluation of sedative drug losses during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2000;15:21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta NM, Halwick DR, Dodson BL, et al. . Potential drug sequestration during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Results from an ex vivo experiment. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1018–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wildschut ED, de Hoog M, Ahsman MJ, et al. . Plasma concentrations of oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate in critically ill children on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. PLoS One. 2010;5:5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wildschut ED, Ahsman MJ, Allegaert K, et al. . Determinants of drug absorption in different ECMO circuits. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pea F, Viale P, Pavan F, et al. . Pharmacokinetic considerations for antimicrobial therapy in patients receiving renal replacement therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:997–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wildschut ED, Ahsman MJ, Allegaert K, et al. . Determinants of drug absorption in different ECMO circuits. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jamal JA, Mueller BA, Choi GYS, et al. . How can we ensure effective antibiotic dosing in critically ill patients receiving different types of renal replacement therapy? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;82:92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garrelts JC, Wagner DJ. The pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerance of cefepime administered as an intravenous bolus or as a rapid infusion. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:1258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huls CE, Prince RA, Seilheimer DK, et al. . Pharmacokinetics of cefepime in cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1414–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blumer JL, Reed MD, Knupp C. Review of the pharmacokinetics of cefepime in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research C for VM : Bioanalytical Method Validation: Guidance for Industry.

- 52.Wilson FP, Bachhuber MA, Caroff D, et al. . Low cefepime concentrations during high blood and dialysate flow continuous venovenous hemodialysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2178–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allaouchiche B, Breilh D, Jaumain H, et al. . Pharmacokinetics of cefepime during continuous renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients. 1997; 41:2424–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isla A, Gascón AR, Maynar J, et al. . Cefepime and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT): In vitro permeability of two CRRT membranes and pharmacokinetics in four critically ill patients. Clinical Therapeutics. 2005;27:599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Troyanov S, Cardinal J, Geadah D, et al. . Solute clearances during continuous venovenous haemofiltration at various ultrafiltration flow rates using Multiflow-100 and HF1000 filters. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:961–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allaouchiche B, Breilh D, Jaumain H, et al. . Pharmacokinetics of cefepime during continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2424–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malone RS, Fish DN, Abraham E, et al. . Pharmacokinetics of cefepime during continuous renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaijamorn W, Charoensareerat T, Srisawat N, et al. . Cefepime dosing regimens in critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: A Monte Carlo simulation study. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Philpott CD, Droege CA, Droege ME, et al. . Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of extended-infusion cefepime in critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: A prospective, open-label study. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39:1066–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stitt G, Morris J, Schmees L, et al. . Cefepime pharmacokinetics in critically ill pediatric patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02006–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bugnon D, Giannoni E, Majcherczyk P, et al. . Pitfalls in cefepime titration from human plasma: Plasma-and temperature-related drug degradation in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3654–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Preston TJ, Ratliff TM, Gomez D, et al. . Modified surface coatings and their effect on drug adsorption within the extracorporeal life support circuit. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2010;42:199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nasr VG, Meserve J, Pereira LM, et al. . Sedative and analgesic drug sequestration after a single bolus injection in an ex vivo extracorporeal membrane oxygenation infant circuit. ASAIO J. 2019;65:187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imburgia CE, Rower JE, Green DJ, et al. Remdesivir and GS-441524 extraction by Ex Vivo extracorporeal life support circuits. ASAIO J. 2021; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]