Abstract

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been linked to common mental disorders (CMDs) such as anxiety and depressive thoughts. We examined the prevalence of ACEs and their association with CMDs among pregnant women living with HIV (PWLHIV) in Malawi–an HIV endemic resource-limited setting.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of 798 PWLHIV enrolled in the VITAL Start trial in Malawi (10/2018 to 06/2021) (NCT03654898). ACE histories were assessed using WHO’s Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) tool. Depressive symptoms (somatic complaints, reduced vital energy, anxiety, and depressive thoughts) were assessed using WHO’s Self Reporting Questionnaire 20-Item (SRQ-20) tool. Log-binomial regressions were used to examine the association between cumulative ACEs and each depressive symptom, as well as identify ACEs driving this association.

Results

The mean age of our sample was 27.5 years. Over 95% reported having experienced ≥1 ACE. On average, each participant reported four ACEs; 11% reported sexual abuse. About 52% and 44% reported anxiety and depressive thoughts, respectively. In regressions, cumulative ACE scores were significantly associated with depressive symptoms—even after adjusting for multiple testing. This association was primarily driven by reports of sexual abuse.

Limitations

Data on maternal ACEs were self-reported and could suffer from measurement error because of recall bias.

Conclusions

ACEs are widespread and have a graded relationship with depressive symptoms in motherhood. Sexual abuse was found to be a primary driver of this association. Earlier recognition of ACEs and provision of trauma-informed interventions to improve care in PWLHIV may reduce negative mental health sequelae.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, pregnant women living with HIV, resource-limited settings, prevalence, Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—or traumatic events among those aged 0-17 years—are a critical public health issue as they have been linked to a plethora of poor health outcomes, including common mental disorders (CMDs) (CDC, 2020). ACEs include exposure in childhood to any conditions that can undermine a child’s environment, for example, abuse, witnessing violence, or the death of a parent (CDC, 2020). Globally, nearly one billion children are exposed to at least one form of ACE annually (Hillis et al., 2016). ACEs have lifelong adverse impacts on health, with the impacts stronger and more persistent among women (Brown et al., 2015; Hillis et al., 2001). ACEs are associated with worse overall self-rated health, an increased likelihood of dying earlier (Bellis et al., 2014; Lansford et al., 2021), risky sexual behaviors (Campbell et al., 2016), and HIV infection (Goodman et al., 2017). ACEs are also strongly associated with CMDs such as depression (Hughes et al., 2017; Manyema et al., 2018), and having suicidal thoughts (Merrick et al., 2017; Satinsky et al., 2021). These effects have been reported worldwide, including in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Gardner et al., 2019; Kapetanovic et al., 2014) where exposure to childhood adversity through poverty, community violence, HIV/AIDS, and orphanhood is widespread (Benjet, 2010; Cluver and Orkin, 2009; Hailes et al., 2019; Hillis et al., 2016; Leoschut and Kafaar, 2017). More than 50% of adolescents in several parts of SSA report experiencing at least one form of ACE (Kidman et al., 2018; Manyema et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Satinsky et al., 2021; VanderEnde et al., 2018; Zietz et al., 2020), with data from 13 countries showing that female sexual abuse is higher among the region’s orphaned children (Kidman and Palermo, 2016).

ACEs can exacerbate other public health issues such as HIV/AIDS (Hatcher et al., 2015; Heestermans et al., 2016), and their prevalence among pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV (PWLHIV) can derail global efforts to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Emerging literature suggests that ACEs are associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), unsuppressed viral load, and HIV disease progression (Heestermans et al., 2016; Whetten et al., 2013). At the same time, depression and suicide ideation—known correlates of ACEs—are associated with suboptimal ART adherence and retention (Heestermans et al., 2016; Nachega et al., 2012; Uthman et al., 2014). Considering global ambitions to eliminate the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030 (UNAIDS, 2014), these associations are concerning, especially in SSA. SSA is home to approximately 70% of the 38 million people living with HIV, and the region accounts for over two-thirds of the 150,000 new pediatric HIV infections estimated annually (UNAIDS, 2019). Fortunately, with the widespread availability of more potent ART, prevention of these transmissions is possible, but requires that the mother has a suppressed HIV load. HIV suppression results from good ART adherence and retention in HIV care (Petra Study Team, 2002). Unfortunately, exposure to ACEs is associated with suboptimal ART adherence and retention (Pence et al., 2012; Whetten et al., 2013), yet these are critical in preventing vertical transmission of HIV—the key to an HIV-free generation.

Despite the importance of ACEs and CMDs in the context of HIV in SSA, and consequently globally, there is a paucity of research on the prevalence of ACEs and their association with CMDs among PWLHIV in the region. To date, the bulk of the research on these associations among pregnant/postpartum women has been conducted outside Africa and in resource-rich settings (Bonacquisti et al., 2014; Choi and Sikkema, 2016; Goldstein et al., 2021; McDonnell and Valentino, 2016; Schury et al., 2017), with only a few studies done in SSA (Choi et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2012; Mahenge et al., 2018; Maré et al., 2021). Even fewer studies have examined these associations among PWLHIV specifically. In South Africa and Kenya, it was reported that maternal childhood adversity is associated with depression or mental distress in a sample that included HIV-positive women but the studies did not stratify the analyses by HIV status (Maré et al., 2021; Osok et al., 2018). A recent systematic review concluded that there is currently no quality evidence documenting the prevalence of CMDs among young mothers living with HIV in SSA (Roberts et al., 2021), let alone its link to childhood adversity in this population.

This study has three objectives. First, to describe the prevalence of childhood adversity among PWLHIV in Malawi, a typical HIV-endemic resource-limited setting of SSA. Second, to examine the relationship between childhood adversity and CMDs in this population. We hypothesized that rates of CMDs will be higher among PWLHIV with histories of childhood adversity and that this association increases with the accumulation of more ACEs. Third, to identify ACE categories that may be individually associated with CMDs or be driving the association between total ACE scores and the CMDs.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a cross-sectional study, drawing data from the VITAL Start (Video-based intervention to Inspire Treatment Adherence for Life) trial (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03654898)—a randomized controlled trial currently ongoing at three sites in Malawi. The three sites of the VITAL Start trial are two large urban health centers in Malawi’s capital city, Lilongwe, and Mangochi, a busy rural district hospital in Southeastern Malawi. These sites were selected to represent urban, peri-urban, and rural PWLHIV in Malawi. The ANC HIV prevalence at these clinics ranged from 11 to 13%, similar to national estimates of HIV prevalence among women of child-bearing age (Malawi Ministry of Health, 2018). Details of the trial have previously been described (Kim et al., 2020). Briefly, the trial’s primary aim is to evaluate the effects of VITAL Start on maternal ART adherence and retention in care. The trial includes pregnant women, 18 years or older who test HIV positive by two antibody rapid tests. The present study utilized baseline data of all participants collected at enrolment. Malawi—located in Southeast Africa—has one of the lowest GDPs per capita in the world, nearly 13% of the female adult population is living with HIV (Ministry of Health (Malawi), 2017; The World Bank, 2019), and vertical HIV transmission continues to be a problem (UNAIDS, 2020).

Measures

Adverse childhood events (ACEs):

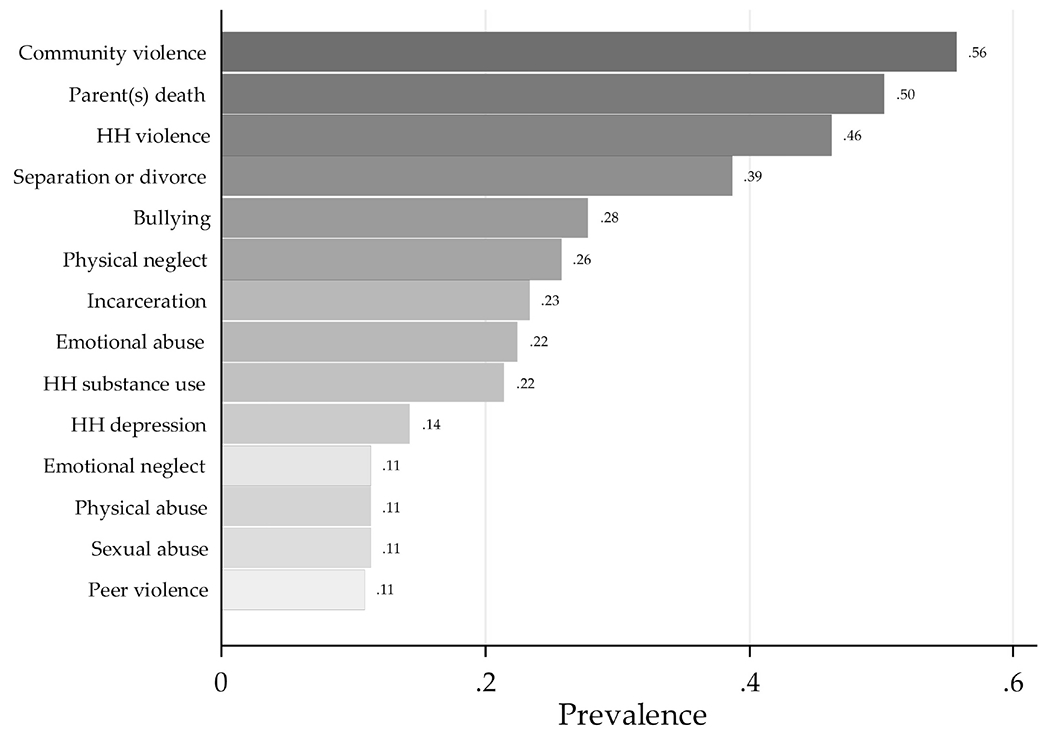

Maternal histories of ACEs were assessed using the World Health Organization’s Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) tool (World Health Organization, 2018). The ACE-IQ tool has been validated in multiple settings (Christoforou and Ferreira, 2020; Ho et al., 2019; Kidman et al., 2019), compares favorably with other tools for assessing ACEs (Bethell et al., 2017), and used in Malawi (Kidman et al., 2019; VanderEnde et al., 2018). In Malawi, the validity and reliability of the original ACE-IQ tool were evaluated in a sample of adolescents who answered questions from the ACE-IQ and the Beck Depression Inventory, concluding that the ACE-IQ could be used in this setting. For the present study, the tool was culturally adapted and administered in Chichewa—Malawi’s local language. The tool assesses ACEs across 13 categories in four broad groups: childhood abuse, childhood neglect, household dysfunction, and community dysfunction. Because parental death and divorce/separation were both pervasive and may have differential impacts, we treated them as separate categories and not combined as recommended (World Health Organization, 2018). Therefore, we had 14 ACE categories (Figure 1). We used WHO’s “frequency” method to score ACE reports (World Health Organization, 2018). In the frequency method, exposure to a specific ACE category was a “1” score if the participant’s response was “Yes” to a question and “0” if the response was “No”. The scores were then added, with 14 as the maximum score. We analyzed ACEs as individual categories with those without a history of that ACE as the reference group, and as cumulative scores (Kidman et al., 2020; Manyema et al., 2018; Satinsky et al., 2021).

Fig. 1..

Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

This figure shows the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in each ACE category among pregnant women living with HIV in Malawi. The taller the bar, the higher the prevalence. Reports of ACEs were assessed using WHO’s Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) tool and scored using the frequency method recommended by the WHO.

Common mental disorders (CMDs):

These were assessed using the self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20)—a 20-item tool developed by the WHO to screen for neurotic disorders, particularly where the diagnosis of these disorders in primary care settings can be challenging (Beusenberg et al., 1994). Validation studies in Malawi concluded that the tool can be used to screen for CMDs in this setting (Stewart et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2013). In Malawi, the SRQ-20, translated into Chichewa, was validated in a sample of rural pregnant women using the DSM-IV major and major-or-minor depressive episode as the gold standard for depression diagnoses (Stewart et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2013). The tool asks a set of questions about non-specific psychosomatic complaints (7 items), reduced vital energy (5 items), anxiety (4 items), and depressive thoughts (4 items), which collectively, fall under CMDs (Table 1). All the questions were binary, with responses scored 1 for ‘yes’ (symptom present) and 0 for ‘no’ (symptom absent). The item scores were then added to obtain a total score, with 20 as the maximum possible score. From the total scores, we identified probable cases of depression. For this study, a participant was “depressed” if the total score was ≥8/20 (Harpham et al., 2005; Nguyen et al., 2014).

Table 1:

SRQ items and frequencies of responses for each item (n=798)

| CMD Category | Item # | SRQ item | Yes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic complaints | 1 | Do you often have headaches? | 317 | 40% |

| Somatic complaints | 2 | Is your appetite poor? | 250 | 31% |

| Somatic complaints | 3 | Do you sleep badly? | 276 | 35% |

| Somatic complaints | 5 | Do your hands shake? | 105 | 13% |

| Somatic complaints | 7 | Is your digestion poor? | 75 | 9% |

| Somatic complaints | 19 | Do you have uncomfortable feelings in your stomach? | 356 | 45% |

| Somatic complaints | 20 | Are you easily tired? | 362 | 45% |

| Reduced vital energy | 8 | Do you have trouble thinking clearly? | 193 | 24% |

| Reduced vital energy | 11 | Do you find it difficult to enjoy your daily activities? | 155 | 19% |

| Reduced vital energy | 12 | Do you find it difficult to make decisions? | 155 | 19% |

| Reduced vital energy | 13 | Is your daily work suffering? | 181 | 23% |

| Reduced vital energy | 18 | Do you feel tired all the time? | 393 | 49% |

| Anxiety | 4 | Are you easily frightened? | 179 | 22% |

| Anxiety | 6 | Do you feel nervous, tense or worried? | 296 | 37% |

| Anxiety | 9 | Do you feel unhappy? | 245 | 31% |

| Anxiety | 10 | Do you cry more than usual? | 106 | 13% |

| Depressive thoughts | 14 | Are you unable to play a useful part in life? | 223 | 28% |

| Depressive thoughts | 15 | Have you lost interest in things? | 219 | 27% |

| Depressive thoughts | 16 | Do you feel that you are a worthless person? | 216 | 27% |

| Depressive thoughts | 17 | Has the thought of ending your life been on your mind? | 115 | 14% |

Ethical approval

We received ethical approval from the National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi (# 1593) and the Baylor College of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board (# H-39785).

Analytic approach

Both univariable and multivariable approaches were used to summarize the data. Frequencies and proportions were used to summarize the prevalence of ACEs and CMDs. Chi-square tests were used to test associations between ACEs and CMDs. In multivariable analyses, the association between ACEs and each outcome was modeled using log-binomial regressions given that the outcomes were relatively common (McNutt et al., 2003). In cases where the log-binomial models failed to converge, we fitted modified Poisson regressions with robust error variances (Zou, 2004). To determine the final models, we forced the primary exposure (ACE), established confounders, and biologically important variables in the model regardless of significance, then selected other potential confounders using the “change in estimate” rule; a variable was a confounder if its addition to a regression model led to a change in effect size of not less than 10%. ACE scores were entered in the main model as a continuous variable. We verified that multicollinearity was not a problem (VIF =6.1). We checked for specification errors using the linktest and model goodness-of-fit using deviance and influence statistics (Long and Freese, 2006) and adjusted the models accordingly. To determine statistical significance for the primary exposure variables (total ACE score), we adjusted the alpha level for multiple testing on the outcomes using the Bonferroni procedure. A p-value <0.01 was determined to be statistically significant. All tests were two-sided, and results are presented as risk ratios (RR). All analyses were performed in Stata 14.

Sensitivity analysis:

We performed two sensitivity analyses to check the robustness of our findings. In the first sensitivity analysis, we changed the method of scoring histories of ACEs from the frequency method to the binary method—both of which are recommended scoring methods by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2018). In the binary method, any response in the affirmative (“most of the time”, “some of the time”, “once”) within a category was coded as a “1” score. As in the main analysis, the scores were then added with 14 as the maximum score. In the second sensitivity analysis, we varied the optimal threshold for identifying probable cases of depression. As a lower value, we used a total score cut-off point of 4 to be consistent with findings from a validation study that was conducted in South Africa (van der Westhuizen et al., 2016). And as a higher cut-off point, a total score of 13 was considered optimal as suggested by a study in India (Patel et al., 2008).

Results

Our sample comprised 798 PWLHIV, with a mean age was 27.5 years (Table 2). Overall, the majority had at least a primary education, had partners, were not household heads, were pregnant at least once before, presented in the second trimester of the pregnancy, and used public transport to get to the facilities. Somatic complaints were the most common depressive symptom (80%), followed by reduced vital energy symptoms (63%). Nearly half (45%) of the women reported having depressive thoughts and about 1 in 3 (34%) women were probable cases of depression (total score ≥8/20). About 32% (255/798) of all mothers reported at least one symptom in each of the four broad categories of depressive symptoms.

Table 2:

Demographic characteristics and maternal reports of adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptoms and (n=798)

| Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 27.45 | 6.59 |

| Education | ||

| No education | 40 | 5% |

| Primary | 441 | 55% |

| Secondary | 287 | 36% |

| Post-secondary | 30 | 4% |

| Monthly income (Malawi Kwacha)* | ||

| ≤49,999 | 471 | 59% |

| 50,000 - 99,999 | 219 | 27% |

| 100,000 - 249,999 | 83 | 10% |

| ≥ 250,0000 | 25 | 3% |

| Has partner (Married or boyfriend) | 729 | 91% |

| Household head | 145 | 18% |

| Disclosure to partner (Yes) | 130 | 16% |

| Received HIV diagnosis today (Date of eligibility assessment) | 713 | 89% |

| Number of pregnancies | ||

| First | 118 | 15% |

| Second, third, fourth | 576 | 72% |

| More than four | 104 | 13% |

| Gestations age (Trimester) | ||

| First trimester | 74 | 9% |

| Second trimester | 597 | 75% |

| Third trimester | 127 | 16% |

| Travel mode | ||

| Walk | 229 | 29% |

| Public transport | 559 | 70% |

| Private transport | 10 | 1% |

| Exposure | ||

| History of adverse childhood events (ACE) | 755 | 95% |

| Depressive symptoms | ||

| Somatic complaints | 635 | 80% |

| Reduced vital energy | 502 | 63% |

| Anxiety | 419 | 53% |

| Depressive thoughts | 358 | 45% |

| Depressed (score ≥8) | 278 | 35% |

In 2021, 805 Malawi Kwacha =1US$ (Knoema, 2021). Note: The percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

ACE prevalence (individual categories)

As noted, maternal report of childhood adversity was common, with 95% of the women reporting at least one form of ACE. On average, each mother reported four forms of childhood adversity, and more than 20% reported no less than six forms of childhood adversity. The most commonly reported ACEs were community violence (56%) followed by parental death (50%) and witnessing household violence (46%) (Figure 1). Various forms of abuse were also reported. Emotional abuse was the leading form of abuse (23%) followed by both physical and sexual abuse at 11%. Child neglect was also reported, with more than twice as many mothers reporting physical neglect compared to emotional neglect (26 vs. 11%). Without the two commonest forms of ACEs (community violence and parental death), about 84% reported experiencing at least one ACE (a decrease from 95%). More broadly, household dysfunction was the commonest childhood adversity (household dysfunction: 85%; community dysfunction: 66%; neglect: 32%; abuse: 31%).

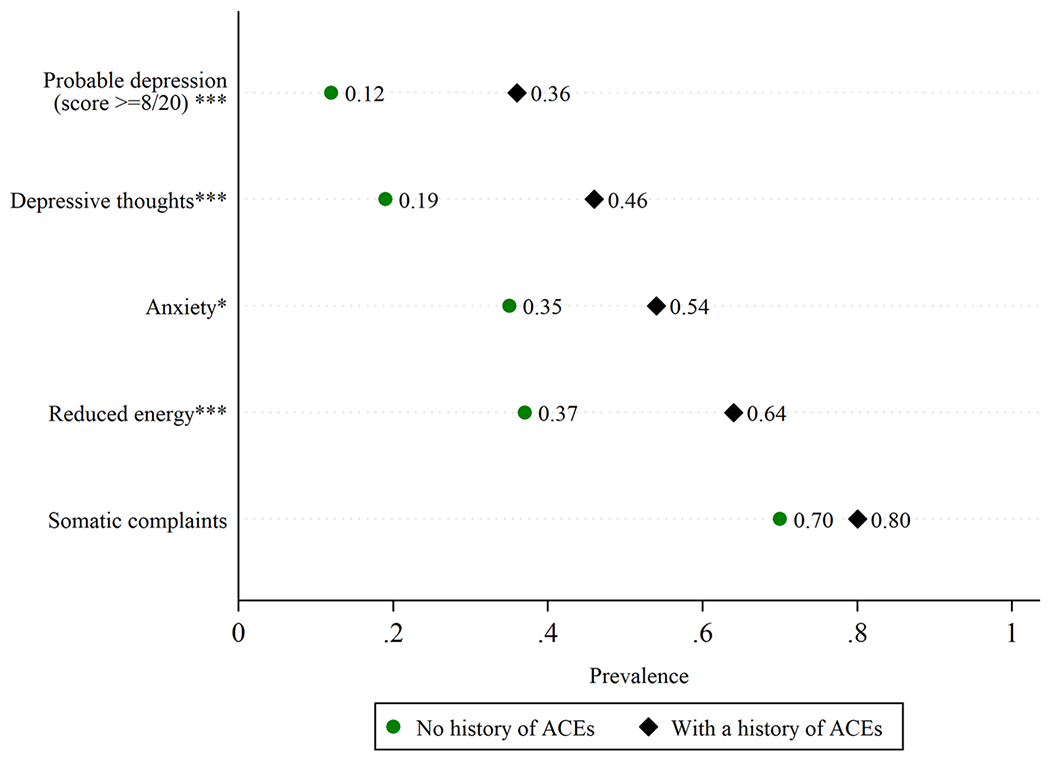

Association (unadjusted) between ACEs and depressive symptoms

In bivariable analyses, all depressive symptoms were higher among mothers reporting any ACE history compared to those without ACE histories (Figure 2). In the figure, CMD prevalence is represented by circles among those without ACE histories and diamond shapes among those with any ACE history. Thus, the proportion that reported depressive thoughts was +27 points higher (46 vs. 19%) among mothers with any ACE history compared to those without ACE histories (p<0.001). Similarly, the proportion that reported symptoms of reduced vital energy and anxiety were significantly higher among those with any ACE histories compared to those without ACE histories by at least 19 points (64 vs. 37% and 54 vs. 35%), respectively. The trend was the same for somatic complaints. Following these results, the proportion of probable cases of depression was significantly higher among mothers with any ACE histories compared to those without ACE histories (36 vs 11%, p<0.001). Within each group (women with ACE histories and those without ACE histories) the pattern of CMDs was similar, with somatic complaints as the most common symptom, followed by reduced energy, anxiety, and depressive thoughts.

Fig. 2.

Depressive symptoms and history of adverse childhood experiences (ACE).

This figure shows the prevalence of depressive symptoms by ACE history. The circles represent the prevalence of depressive symptoms among participants without histories of ACEs while the diamonds represent the prevalence of depressive symptoms among participants with histories of ACEs. Asterisks denote significant differences across ACE history in bivariable analyses using Chi-square tests, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. For each depressive symptom as well as for cases of probable depression, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was higher among those with histories of ACEs.

Impact of ACEs on depression

In adjusted models, cumulative ACE scores were significantly associated with each of the four categories of depressive symptoms, as well as a diagnosis of probable depression (Table 3). The associations were still significant even after adjusting for multiple testing. We observed that every unit increase in ACE score significantly increased the risk by 4% for somatic symptoms (RR=1.04; 99% CI: 1.02, 1.6; p<0.001), 9% for reduced vital energy (RR=1.09; 99% CI: 1.11, 1.21; p<0.001), 10% for anxiety (RR=1.10; 99% CI: 1.07, 1.13; p<0.001), and 13% for depressive thoughts (RR=1.13; 99% CI: 1.09, 1.17; p<0.001). Similarly, a unit score increase in ACEs was associated with a significant increase of 16% in the risk of being diagnosed with probable depression (RR=1.16; 99% CI: 1.12, 1.21; p<0.001). We also found that mothers with secondary education were significantly less likely to report depressive thoughts or be identified as probable cases of depression, compared to mothers without any education. At the same time, the risk of anxiety decreased as the number of pregnancies increased. For example, the risk of anxiety was 17% lower among mothers who had two to four prior pregnancies compared to those who were pregnant for the first time. Furthermore, mothers presenting to the clinic in the second or third trimesters of their pregnancies were less likely to report any depressive symptoms compared to those who presented in the first trimester of their pregnancies. Mothers with partners were significantly more likely to report somatic complaints compared with those without partners (RR=1.17; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.37; p=0.02).

Table 3:

The association between ACEs and depression symptoms among pregnant women living with HIV (n=798)

| Somatic complaints | Reduced energy Anxiety | Depressive thoughts | Depressed (score ≥8) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio | 99% CI | Risk Ratio | 99% CI | Risk Ratio | 99% CI | Risk Ratio | 99% CI | Risk ratio | 99% CI | |

| ACE score | 1.04*** | [1.02,1.06] | 1.09*** | [1.06,1.11] | 1.10*** | [1.07,1.14] | 1.13*** | [1.09,1.17] | 1.16** | [1.11,1.21] |

| Age | 0.99 | [0.98,1.00] | 1.00 | [0.98,1.01] | 1.00 | [0.99,1.02] | 1.01* | [1.00,1.02] | 1.00 | [0.98,1.02] |

| Education, Ref: None | ||||||||||

| Primary | 0.97 | [0.76,1.22] | 0.98 | [0.68,1.40] | 1.08 | [0.68,1.71] | 0.89 | [0.60,1.32] | 0.80 | [0.49,1.30] |

| Secondary | 1.03 | [0.81,1.31] | 1.01 | [0.70,1.46] | 1.09 | [0.67,1.76] | 0.67* | [0.43,1.04] | 0.65* | [0.38,1.10] |

| Some college | 0.90 | [0.62,1.31] | 0.90 | [0.53,1.54] | 1.21 | [0.63,2.32] | 1.04 | [0.53,2.06] | 0.78 | [0.34,1.78] |

| Income, Ref: | ||||||||||

| <MK50,000† | ||||||||||

| 50,000 to 99,999 | 0.96 | [0.86,1.07] | 0.99 | [0.84,1.17] | 0.84* | [0.68,1.04] | 0.91 | [0.71,1.15] | 1.01 | [0.76,1.34] |

| 100,000-249,999 | 0.93 | [0.79,1.10] | 1.07 | [0.87,1.32] | 0.95 | [0.72,1.26] | 0.95 | [0.69,1.32] | 1.04 | [0.70,1.56] |

| 250,000 or more | 1.13 | [0.90,1.41] | 1.14 | [0.78,1.68] | 1.06 | [0.68,1.65] | 0.59 | [0.24,1.47] | 1.12 | [0.52,2.38] |

| Partner, Ref: No partner | ||||||||||

| Has partner | 1.20* | [0.98,1.48] | 1.02 | [0.80,1.30] | 1.01 | [0.77,1.32] | 0.91 | [0.66,1.27] | 1.06 | [0.70,1.61] |

| Household head: Ref (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.97 | [0.85,1.10] | 1.05 | [0.89,1.26] | 1.16 | [0.95,1.41] | 1.16 | [0.92,1.47] | 1.05 | [0.78,1.43] |

| Partner disclosure: Ref (No) | [1.00,1.00] | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.99 | [0.87,1.13] | 0.99 | [0.80,1.23] | 0.91 | [0.70,1.18] | 0.88 | [0.64,1.20] | 0.93 | [0.65,1.34] |

| HIV diagnosis, Ref: Today | ||||||||||

| Before today | 1.16** | [1.01,1.32] | 1.00 | [0.78,1.27] | 1.13 | [0.86,1.48] | 1.08 | [0.78,1.51] | 1.18 | [0.81,1.72] |

| Pregnancy number, Ref: First | ||||||||||

| Two to four | 0.95 | [0.84,1.07] | 0.90 | [0.73,1.10] | 0.81* | [0.64,1.04] | 0.93 | [0.68,1.28] | 0.91 | [0.63,1.30] |

| More than four | 0.92 | [0.75,1.14] | 0.84 | [0.60,1.17] | 0.80 | [0.55,1.17] | 0.87 | [0.56,1.34] | 0.83 | [0.48,1.43] |

| Trimester, Ref: First | ||||||||||

| Second | 0.91* | [0.81,1.03] | 0.88 | [0.73,1.06] | 0.85 | [0.67,1.09] | 0.75** | [0.58,0.98] | 0.62** | [0.46,0.84] |

| Third | 0.87* | [0.74,1.02] | 0.81* | [0.63,1.04] | 0.89 | [0.66,1.21] | 0.78 | [0.56,1.09] | 0.64** | [0.44,0.95] |

| Travel mode, Ref: Walk | ||||||||||

| Public transport | 1.03 | [0.93,1.14] | 0.94 | [0.81,1.09] | 0.97 | [0.81,1.17] | 0.91 | [0.74,1.12] | 0.84 | [0.65,1.08] |

Exponentiated coefficients (risk ratios); 99% confidence intervals in brackets;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001;

In 2021, 805 Malawi Kwacha =1US$ Knoema, 2021).

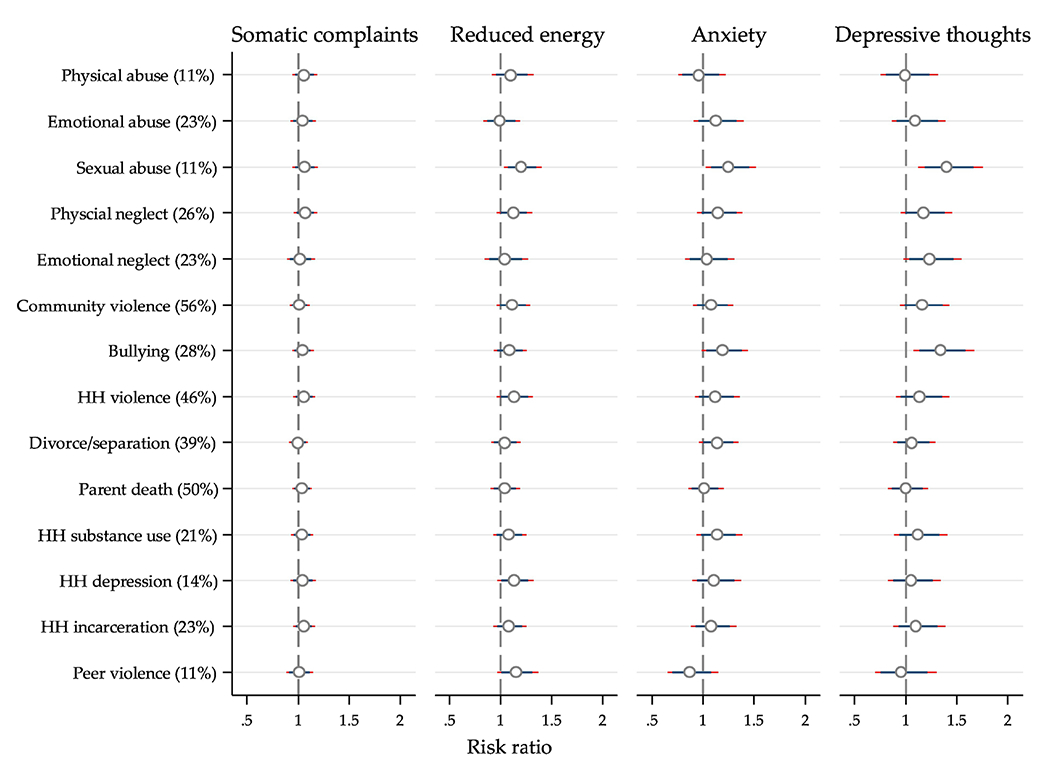

ACEs driving depressive symptoms

In the final adjusted analysis, we identified ACEs driving the association between cumulative ACEs and depressive symptoms, and we found that sexual abuse is the primary driver of this association (Figure 3). In this figure, each column is an adjusted model of each of the CMDs, with the association reported as risk ratios. An adjusted risk ratio of 1 suggests no significant difference in the outcome variable among those with and without a history of childhood adversity indicated on the y-axis. Thus, sexual abuse had the largest effect and was significantly associated with all depressive symptoms except somatic complaints. Bullying and emotional neglect were also behind this association, but not to the same extent as sexual abuse. For example, depressive thoughts were associated with sexual abuse (RR=1.42; 95% CI: 1.20, 1.68; p<0.001), bullying (RR=1.35; 95% CI: 1.14, 1.60; p <0.001), and emotional neglect (RR=1.24; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.48; p=0.015). Similarly, anxiety was driven by sexual abuse, bullying, physical neglect, household substance use, and divorce/separation. No ACE category appeared to individually drive the relationship between cumulative ACEs and somatic complaints. [Note: in Figure 3, each ACE was binary, with those reporting that specific ACE coded “1” and “0” otherwise. Those not reporting the ACEs “0s” were the reference group.]

Fig. 3.

Association between individual ACE categories and depressive symptoms.

This figure shows the association between individual ACE categories and depressive symptoms derived from Jog-binomial regressions. ACE categories and their overall prevalence are on the y-axis. Each column is a model of each of the depressive symptoms, with the association reported as risk ratios and adjusted for potential confounders and biologically important variables such as age. An adjusted risk ratio of 1 suggests no significant difference in the outcome variable among those with and without a history of childhood adversity on the y-axis. Note: two confidence intervals are presented: 95% (thicker and at the top and 99% (thinned and underneath). The figure shows that sexual abuse is the most prominent ACE as it is significantly associated with all depressive symptoms except for somatic complaints.

Sensitivity analysis

In the first sensitivity analysis—where maternal ACE reports were scored using the binary method instead of the frequency method—the proportion reporting ACEs increased but overall findings were relatively unchanged. The proportion reporting any ACE histories increased from 95% to 98%, and the average ACE score was six (increased from four). The proportion reporting each ACE category remained the same for seven of the categories but increased for the other seven. The following changes in percentage points were noted: peer violence +37; emotional abuse +31; physical abuse +28; community violence +28; bullying +27; physical neglect +22; household violence +13 (Supplementary Figure S1). In adjusted log-binomial and modified Poisson models, the effect of a one-score increase in ACE score remained the same both in magnitude and strength except for probable cases of depression where it marginally increased from 16% (RR=1.16; 99% CI: 1.12, 1.20) to 17% (RR=1.17; 99% CI: 1.12, 1.22). In terms of primary drivers of the association between cumulative ACEs and depressive symptoms, sexual abuse was as important as before but emotional abuse and bullying were now equally important (Supplementary Figure S2). Unlike before, however, when there was no primary driver for somatic complaints, emotional abuse now was (RR=1.09; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.19; p=0.04).

In the second sensitivity analysis, lower and higher thresholds for identifying probable cases of depression were used, and our findings changed materially. When a lower threshold (depression score ≥4) was used, up to 59% (467/798) of the mothers were classified as probably depressed compared with 35% (278/798) in the main analysis. Similarly, the proportion of mothers probably depressed decreased to 11% (89/798) when a higher threshold (depression score ≥13) was used.

Discussion

We examined the association between maternal reports of ACEs and depressive symptoms among PWLHIV in Malawi—a typical resource-limited setting endemic to HIV. Our findings suggest that in this setting both ACEs and depressive symptoms are highly prevalent, and ACEs are positively associated with depressive symptoms, as well as a diagnosis of probable depression. The risk of depressive symptoms and being a probable case of depression increases with each additional ACE. The magnitude of the effect of a one-unit increase in total ACE score was highest for depressive thoughts, followed by anxiety and reduced vital energy. Of all ACE categories, sexual abuse was the primary driver of the association between total ACE scores and depressive symptoms. In sensitivity analysis, the association between ACEs and depressive symptoms was robust to changes in the method for scoring ACEs.

The prevalence of ACEs (95%) reported in the current study is often higher and not always consistent with reports from similar studies, although the prevalence in each category of ACEs is consistent with reports from several studies in the region. Our findings are closer to reports of ACE prevalence among adolescents and young adults in Malawi (82-99%) (Kidman et al., 2020; VanderEnde et al., 2018). Among adolescent and young females alone in Malawi, these studies have reported an ACE prevalence of 77% which is slightly lower than our findings but high nonetheless (Kidman et al., 2020; VanderEnde et al., 2018). As these studies also used the ACE-IQ tool to assess the ACE prevalence, included males and females, and people with and without HIV, these findings suggest that ACE prevalence is high regardless of sex or HIV status and point to a more pervasive public health issue nationwide. Furthermore, the ACE prevalence reported in this study is similar to prevalence among young adults and women in South Africa (84-90%) (Brittain et al., 2021; Manyema et al., 2018), but higher than estimates from a recent meta-analysis of studies from countries across the globe (33-88%) (Hughes et al., 2017), Peru (72%) (Zhong et al., 2016), and Honduras (77%) (Kappel et al., 2021).

The differences in estimates of ACE prevalence between the current study and estimates elsewhere could arise because of differences in the study population, setting, and methodology for assessing ACEs. ACE prevalence tends to be lower for studies that do not include people living with HIV specifically or were done in either middle- and high-income countries, perhaps because the conditions for raising children may be better overall (Hughes et al., 2017). In some of these studies, the ACE prevalence was estimated using fewer categories of ACEs (9 categories on average, vs. 14 categories in this study) and excluded community violence (Hughes et al., 2017)—an ACE reported by more than half of mothers in this study. For example, when we excluded ACEs such as community violence, overall prevalence dropped from 95 to 84%. Our findings may also reflect Malawi’s history as the majority of participants were born around the time when ART was not widely available and orphanhood due to HIV/AIDS was widespread. This is supported by the finding that half of the mothers reported having experienced parental death. In sum, the high prevalence of ACEs in the current study is not surprising, especially with reports that abuse and neglect are more common among orphaned children (Kidman and Palermo, 2016). In this study, each mother reported four ACEs on average while two in five (40%) and one in five mothers (20%) mothers reported at least four and six forms of childhood adversity, respectively. These numbers have been reported in Malawi before (Kidman et al., 2020; VanderEnde et al., 2018), but are higher than global estimates of only about 15% reporting up to four ACEs (Hughes et al., 2017). In terms of the prevalence of ACEs in each category, our findings are similar to reports on the prevalence of community violence among those in more resource-limited settings in South Africa (Richter et al., 2018) and on sexual and physical abuse in Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda (Koenig et al., 2004; Mahenge et al., 2018; VanderEnde et al., 2018).

The current study has demonstrated that childhood adversity is associated with depressive symptoms, which is consistent with emerging literature from SSA and evidence from resource-rich settings (Brittain et al., 2021; Campbell et al., 2016; Gartland et al., 2016; Hughes et al., 2017; Kappel et al., 2021; Kidman et al., 2020; Lee and Chen, 2017; Mersky and Janczewski, 2018; Schilling et al., 2008; Too et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2016). As in the majority of these studies, this association is graded—it gets stronger as the number of ACEs increases (Campbell et al., 2016; Kappel et al., 2021; Schilling et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2016). While this association was expected, it is nonetheless disturbing, particularly in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Emerging evidence from the general population of people living with HIV suggests that depression and other CMDs are associated with suboptimal ART adherence and elevated viral load (Heestermans et al., 2016; Whetten et al., 2013). While additional research focusing on the links between ACEs, CMDs, and HIV treatment outcomes among PWLHIV in this setting is warranted, the evidence from the current study suggests the need to pay attention to the mental health needs of people living with HIV.

Also notable is that sexual abuse during childhood, although relatively less common, has more severe consequences as it was the primary driver of the association between cumulative ACEs and depressive symptoms. This is consistent with previous reports which revealed that the high impact of cumulative ACEs is a byproduct of highly consequential ACEs such as sexual abuse (Schilling et al., 2008). In this sample of PWLHIV, about 1 in 10 women reported experiencing child sexual abuse which is similar to reports from several countries across SSA (Ministry of Gender (Malawi) et al., 2013; Selengia et al., 2020; UNICEF Tanzania et al., 2011). Our findings provide further evidence that the consequences of child sexual abuse can be more enduring (Brittain et al., 2021), and in many cases, outlive the physical injuries suffered during the abuse. Additional severe consequences of childhood sexual abuse noted elsewhere include that survivors of sexual abuse are more likely to smoke (Novais et al., 2021); engage in risky sexual behaviors (Campbell et al., 2016); acquire HIV (Goodman et al., 2017); be victims of sexual abuse again (Davis et al., 2006); suffer intimate partner violence (Novais et al., 2021); have sub-optimal education attainment and reduced future earnings (Barrett et al., 2014; Hardner et al., 2018).

In sensitivity analysis, our findings were robust but raised important questions about the ACE-IQ tool’s scoring methods and SRQ-20’s threshold scores for identifying probable cases of depression in this setting. Prevalence overall and in some ACE categories was higher when ACE reports were scored using the binary method in the sensitivity analysis compared to the frequency method in the main analysis. While these changes in ACE prevalence did not materially affect the overall association between cumulative ACEs and depressive symptoms, additional drivers of this association were now identified. These were emotional abuse and bullying alongside sexual abuse from the main analysis. This suggests that the choice of method for scoring the ACE reports is important, and additional research may help to clarify when to use what scoring method. Similarly, when lower and higher thresholds were used to identify probable cases of depression based on responses to the SRQ-20 tool, the proportion probably depressed nearly doubled at the lower threshold and more than halved at the higher threshold. This suggests that thresholds for identifying probable cases of depression should be the ones that have been validated and are contextually appropriate, otherwise the proportion of probable depression cases will either be underestimated or overestimated.

Limitations

These findings should be understood in the context of the following limitations. First, data on maternal ACEs were self-reported and therefore could suffer from measurement error because of recall bias given the long recall period from the time the ACE occurred to the time of the study. Unfortunately, the direction of the potential bias is unclear because ACEs may have been under-reported by some mothers and over-reported by others (Baldwin et al., 2019; Naicker et al., 2017; Reuben et al., 2016). However, if mothers reporting depressive symptoms are more likely to recall childhood adversity then our findings are biased away from the null. Notwithstanding this limitation, almost all prior research on the prevalence of ACEs has relied on memory recall (Hughes et al., 2017). Importantly, we estimated the prevalence of ACEs and depressive symptoms using tools (the ACE-IQ and the SRQ-20) that have been both validated and used in this setting (Stewart et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2013; Swedo et al., 2019).

The second limitation is that there is likely overlap between pregnancy symptoms and depressive symptoms. For example, somatic complaints are common in pregnancy and their presence is not always suggestive of depressive disorders. While we acknowledge this limitation, we emphasize that the SRQ-20 was found to be valid in detecting depressive disorders among pregnant women in Malawi (Stewart et al., 2013). The third limitation is that we are unable to infer causality between ACEs and depressive symptoms as this was a cross-sectional study and that the occurrence of ACEs and depressive symptoms was too far apart to satisfy the “temporal precedence” condition in causality. Despite this limitation, our overall findings are consistent with reports from studies that used designs more suited for causal inference, for example, longitudinal studies which consistently followed participants over time (Clark et al., 2010; Schilling et al., 2007). Thus, the current study provides additional evidence that in resource-limited settings childhood adversity is widespread, including sub-populations such as PWLHIV, and has a graded relationship to both the prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms later in life. Until now, much of the research about ACE prevalence and its association with depression and other mental health conditions has been conducted in resource-rich settings.

Implications for policy and future research

Our findings have important implications for policy and future research. First, the findings demonstrate that ACEs continue to be a public health concern as was also noted in a Malawi government report many years ago (Ministry of Gender (Malawi) et al., 2013). Given the inherent difficulty in getting data about ACEs right at the time they occur (UNICEF Tanzania et al., 2011), strategies to bring change at the community level must be quickly identified and introduced. Such strategies need to be multi-sectoral and could include proactively engaging communities and local leaders to ensure quick and safe reporting of any acts of child abuse, as well as the involvement of law enforcement and social development agencies to ensure that both the children and community members who report child abuse are protected. Data suggest underreporting of abuse (Chandran et al., 2019), particularly sexual abuse, with more than half of sexual abuse victims not reporting the abuse to anyone at the time it occurred (UNICEF Tanzania et al., 2011).

Second, these findings suggest that earlier recognition of pregnant women with histories of ACEs for trauma-informed interventions to improve care in PWLHIV may reduce negative mental health sequelae. All this can be part of antenatal care. In Malawi, screening for histories of ACEs among pregnant women in general or those living with HIV is not done as part of routine antenatal care. The Ministry of Health and its partners should consider developing a tool (a short questionnaire) to screen pregnant women for ACE histories on the women’s first ANC visit, emphasizing more on less common but highly consequential ACEs such as sexual abuse. Those with ACE histories can then receive additional care or trauma-informed interventions. In the short term, studies may also look at the association between ACEs and HIV treatment outcomes (ART adherence, retention in HIV care, viral suppression, prevention of vertical transmission of HIV), and whether depressive symptoms mediate or modify this association. In the medium-to-long term, however, additional research to help develop interventions to support (cope with or ameliorate the effects of ACEs) pregnant women with these histories is warranted.

Conclusions

We described the prevalence of childhood adversity and its association with depressive symptoms among PWLHIV in Malawi. We found that ACEs are widespread and are positively associated with depressive symptoms. Our findings have highlighted that sexual abuse, although relatively less common, is the primary driver of the association between cumulative ACEs and depressive symptoms. Given that depressive symptoms are associated with poor HIV treatment outcomes and PWLHIV are key to global ambitions of achieving an HIV-free generation, the high prevalence of ACEs in this sub-population is concerning. While these findings relate to Malawi specifically, they are generalizable to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, especially where HIV is endemic and multiplicity of ACEs is more likely to happen. In all, the current study represents an important step in confirming that ACEs are a global public health crisis requiring urgent and multi-faceted approaches to prevent their occurrence, improve reporting of such experiences, particularly sexual abuse, and ameliorate the effects of such experiences by providing support and developing interventions to help build resilience to childhood adversity.

Supplementary Material

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with depressive symptoms, but these data have largely come from resource-rich settings.

We examined the prevalence of ACEs and the association between cumulative ACEs and depressive symptoms among pregnant women living with HIV (PWLHIV) in Malawi—a resource-limited setting in sub-Saharan Africa.

We found that ACEs are common among PWLHIV and cumulative ACEs are associated with depressive symptoms, and sexual abuse is the primary driver of this association.

We call for earlier recognition of ACEs and the provision of trauma-informed interventions to improve care in PWLHIV to help reduce negative mental health sequelae.

Acknowledgments

We thank our partner, the Malawi Ministry of Health, for supporting this work. We also thank all the women who participated in this study.

Role of funding source

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health under Award Number R01MH115793-01A1. Xiaoying Yu is supported by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program-BIRCWH; Berenson, PI) from the National Institutes of Health/Office of the Director (OD)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the funding sources.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Baldwin JR, Reuben A, Newbury JB, Danese A, 2019. Agreement Between Prospective and Retrospective Measures of Childhood Maltreatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry 76, 584–593. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A, Kamiya Y, O’Sullivan V, 2014. Childhood sexual abuse and later-life economic consequences. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 53, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, Hughes K, Harrison D, 2014. Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. Journal of public health 36, 81–91. 10.1093/pubmed/fdt038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, 2010. Childhood adversities of populations living in low-income countries: prevalence, characteristics, and mental health consequences. Current opinion in psychiatry 23, 356–362. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833ad79b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell CD, Carle A, Hudziak J, Gombojav N, Powers K, Wade R, Braveman P, 2017. Methods to Assess Adverse Childhood Experiences of Children and Families: Toward Approaches to Promote Child Well-being in Policy and Practice. Acad. Pediatr 17, S51–S69. 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beusenberg M, Orley JH, World Health Organization. Division of Mental, H., 1994. A User’s guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ / compiled by M. Beusenberg and J. Orley). (WHO/MNH/PSF/94.8. Unpublished). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/61113. (Accessed 19 October, 2021).

- Bonacquisti A, Geller PA, Aaron E, 2014. Rates and predictors of prenatal depression in women living with and without HIV. AIDS Care 26, 100–106. 10.1080/09540121.2013.802277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K, Zerbe A, Phillips TK, Gomba Y, Mellins CA, Myer L, Abrams EJ, 2021. Impact of adverse childhood experiences on women’s psychosocial and HIV-related outcomes and early child development in their offspring. Global public health, 1–13. 10.1080/17441692.2021.1986735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MJ, Masho SW, Perera RA, Mezuk B, Cohen SA, 2015. Sex and sexual orientation disparities in adverse childhood experiences and early age at sexual debut in the United States: results from a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse Negl. 46, 89–102. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Egede LE, 2016. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med 50, 344–352. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2020. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/aces/fastfact.html. (Accessed 19 April, 2020).

- Chandran S, Bhargava S, Manohar Rao K, 2019. Under reporting of child sexual abuse-The barriers guarding the silence. Telangana Journal of Psychiatry 4, 57. 10.18231/2455-8559.2018.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, Sikkema KJ, 2016. Childhood Maltreatment and Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse 17, 427–453. 10.1177/1524838015584369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, Sikkema KJ, Vythilingum B, Geerts L, Faure SC, Watt MH, Roos A, Stein DJ, 2017. Maternal childhood trauma, postpartum depression, and infant outcomes: Avoidant affective processing as a potential mechanism. J. Affect. Disord 211, 107–115. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforou R, Ferreira N, 2020. Psychometric Assessment of Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (Ace-Iq) with Adults Engaging in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 8. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld SA, 2010. Does the influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? A 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Ann. Epidemiol 20, 385–394. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Orkin M, 2009. Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med 69, 1186–1193. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Guthrie P, Ross T, O’Sullivan C, 2006. Reducing sexual revictimization: A field test with an urban sample. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/216002.pdf. (Accessed 21 October, 2021).

- Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, Holmes W, 2012. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ 90, 139G–149G. 10.2471/BLT.11.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MJ, Thomas HJ, Erskine HE, 2019. The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 96, 104082. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartland D, Woolhouse H, Giallo R, McDonald E, Hegarty K, Mensah F, Herrman H, Brown S, 2016. Vulnerability to intimate partner violence and poor mental health in the first 4-year postpartum among mothers reporting childhood abuse: an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Archives of women’s mental health 19, 1091–1100. 10.1007/s00737-016-0659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BL, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Grasso DJ, 2021. The Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and a History of Childhood Abuse on Mental Health and Stress during Pregnancy. Journal of Family Violence 36, 337–346. 10.1007/s10896-020-00149-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman ML, Raimer-Goodman L, Chen CX, Grouls A, Gitari S, Keiser PH, 2017. Testing and testing positive: childhood adversities and later life HIV status among Kenyan women and their partners. J Public Health (Oxf) 39, 720–729. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailes HP, Yu R, Danese A, Fazel S, 2019. Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. The lancet. Psychiatry 6, 830–839. 10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30286-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardner K, Wolf MR, Rinfrette ES, 2018. Examining the relationship between higher educational attainment, trauma symptoms, and internalizing behaviors in child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse Negl. 86, 375–383. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpham T, Huttly S, De Silva MJ, Abramsky T, 2005. Maternal mental health and child nutritional status in four developing countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 59, 1060–1064. 10.1136/jech.2005.039180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stöckl H, 2015. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 29, 2183–2194. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heestermans T, Browne JL, Aitken SC, Vervoort SC, Klipstein-Grobusch K, 2016. Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ global health 1. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, Kress H, 2016. Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics 137, e20154079. 10.1542/peds.2015-4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, 2001. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam. Plann. Perspect 33, 206–211. 10.1363/3320601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho GW, Chan AC, Chien W-T, Bressington DT, Karatzias T, 2019. Examining patterns of adversity in Chinese young adults using the Adverse Childhood Experiences—International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Child Abuse Negl. 88, 179–188. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, Dunne MP, 2017. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Public health 2, e356–e366. 10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Dass-Brailsford P, Nora D, Talisman N, 2014. Mental health of HIV-seropositive women during pregnancy and postpartum period: a comprehensive literature review. AIDS Behav. 18, 1152–1173. 10.1007/s10461-014-0728-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappel RH, Livingston MD, Patel SN, Villaveces A, Massetti GM, 2021. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and associated health risks and risk behaviors among young women and men in Honduras. Child Abuse Negl. 115, 104993. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Nachman S, Dietrich J, Liberty A, Violari A, 2018. Childhood adversity increases the risk of onward transmission from perinatal HIV-infected adolescents and youth in South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 79, 98–106. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Palermo T, 2016. The relationship between parental presence and child sexual violence: Evidence from thirteen countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 51, 172–180. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Piccolo LR, Kohler HP, 2020. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Prevalence and Association With Adolescent Health in Malawi. Am. J. Prev. Med 58, 285–293. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Smith D, Piccolo LR, Kohler HP, 2019. Psychometric evaluation of the Adverse Childhood Experience International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Malawian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 92, 139–145. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Tembo TA, Mazenga A, Yu X, Myer L, Sabelli R, Flick R, Hartig M, Wetzel E, Simon K, Ahmed S, Nyirenda R, Kazembe PN, Mphande M, Mkandawire A, Chitani MJ, Markham C, Ciaranello A, Abrams EJ, 2020. The Video intervention to Inspire Treatment Adherence for Life (VITAL Start): protocol for a multisite randomized controlled trial of a brief video-based intervention to improve antiretroviral adherence and retention among HIV-infected pregnant women in Malawi. Trials 21, 207. 10.1186/s13063-020-4131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Zablotska I, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Wagman J, Gray R, 2004. Coerced first intercourse and reproductive health among adolescent women in Rakai, Uganda. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect 30, 156–163. 10.1363/3015604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Godwin J, McMahon RJ, Crowley M, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Coie JD, Dodge KA, 2021. Early Physical Abuse and Adult Outcomes. Pediatrics 147. 10.1542/peds.2020-0873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RD, Chen J, 2017. Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and excessive alcohol use: Examination of race/ethnicity and sex differences. Child Abuse Negl. 69, 40–48. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoschut L, Kafaar Z, 2017. The frequency and predictors of poly-victimisation of South African children and the role of schools in its prevention. Psychol. Health Med 22, 81–93. 10.1080/13548506.2016.1273533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JS, Freese J, 2006. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata, Second ed. Stata Press, College Station, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- Mahenge B, Stöckl H, Mizinduko M, Mazalale J, Jahn A, 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence during pregnancy and their association to postpartum depression. J. Affect. Disord 229, 159–163. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health, 2018. Malawi population-based HIV impact assessment (MPHIA) 2015-16 : final report. [Report]. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60951. (Accessed 24 May 2022).

- Manyema M, Norris SA, Richter LM, 2018. Stress begets stress: the association of adverse childhood experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress. BMC Public Health 18, 835. 10.1186/s12889-018-5767-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maré KT, Pellowski JA, Koopowitz S-M, Hoffman N, van der Westhuizen C, Workman L, Zar HJ, Stein DJ, 2021. Perinatal suicidality: prevalence and correlates in a South African birth cohort. Archives of women’s mental health. 10.1007/s00737-021-01121-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell CG, Valentino K, 2016. Intergenerational effects of childhood trauma: evaluating pathways among maternal ACEs, perinatal depressive symptoms, and infant outcomes. Child maltreatment 21, 317–326. 10.1177/1077559516659556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt L-A, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP, 2003. Estimating the Relative Risk in Cohort Studies and Clinical Trials of Common Outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol 157, 940–943. 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ports KA, Ford DC, Afifi TO, Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A, 2017. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 69, 10–19. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Janczewski CE, 2018. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Postpartum Depression in Home Visiting Programs: Prevalence, Association, and Mediating Mechanisms. Maternal and child health journal 22, 1051–1058. 10.1007/s10995-018-2488-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Gender (Malawi), United Nations Children’s Fund, The Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. Violence against children and young women in Malawi: Findings from a national survey 2013. http://10.150.35.18:6510/www.togetherforgirls.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2013_Malawi_Findings-from-a-Violence-Against-Children-Survey.pdf. (Accessed 25 September, 2021).

- Ministry of Health (Malawi), 2017. Malawi Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (MPHIA) 2015-16: First report. https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Final-MPHIA-First-Report_11.15.17.pdf. (Accessed 20 April, 2020, 2020).

- Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Anderson J, Peltzer K, Wampold S, Cotton MF, Mills EJ, Ho Y-S, Stringer JSA, McIntyre JA, Mofenson LM, 2012. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 26, 2039–2052. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359590f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naicker SN, Norris SA, Mabaso M, Richter LM, 2017. An analysis of retrospective and repeat prospective reports of adverse childhood experiences from the South African Birth to Twenty Plus cohort. PLoS One 12, e0181522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PH, Saha KK, Ali D, Menon P, Manohar S, Mai LT, Rawat R, Ruel MT, 2014. Maternal mental health is associated with child undernutrition and illness in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Ethiopia. Public Health Nutr. 17, 1318–1327. 10.1017/s1368980013001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novais M, Henriques T, Vidal-Alves MJ, Magalhães T, 2021. When Problems Only Get Bigger: The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experience on Adult Health. Front. Psychol 12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.693420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osok J, Kigamwa P, Stoep AV, Huang K-Y, Kumar M, 2018. Depression and its psychosocial risk factors in pregnant Kenyan adolescents: a cross-sectional study in a community health Centre of Nairobi. BMC Psychiatry 18, 136–136. 10.1186/s12888-018-1706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, King M, Kirkwood B, Nayak S, Simon G, Weiss HA, 2008. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: a comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychol. Med 38, 221–228. 10.1017/s0033291707002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Mugavero MJ, Carter TJ, Leserman J, Thielman NM, Raper JL, Proeschold-Bell RJ, Reif S, Whetten K, 2012. Childhood trauma and health outcomes in HIV-infected patients: an exploration of causal pathways. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 59, 409–416. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824150bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petra Study Team, 2002. Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 359, 1178–1186. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Schroeder F, Hogan S, Ramrakha S, Poulton R, Danese A, 2016. Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 57, 1103–1112. 10.1111/jcpp.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter LM, Mathews S, Kagura J, Nonterah E, 2018. A longitudinal perspective on violence in the lives of South African children from the Birth to Twenty Plus cohort study in Johannesburg-Soweto. S. Afr. Med. J 108, 181–186. 10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KJ, Smith C, Cluver L, Toska E, Sherr L, 2021. Understanding Mental Health in the Context of Adolescent Pregnancy and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review Identifying a Critical Evidence Gap. AIDS Behav. 25, 2094–2107. 10.1007/s10461-020-03138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satinsky EN, Kakuhikire B, Baguma C, Rasmussen JD, Ashaba S, Cooper-Vince CE, Perkins JM, Kiconco A, Namara EB, Bangsberg DR, Tsai AC, 2021. Adverse childhood experiences, adult depression, and suicidal ideation in rural Uganda: A cross-sectional, population-based study. PLoS Med. 18, e1003642. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Gore S, 2008. The impact of cumulative childhood adversity on young adult mental health: measures, models, and interpretations. Social science & medicine (1982) 66, 1140–1151. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Aseltine RH Jr., Gore S, 2007. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health 7, 30–30. 10.1186/1471-2458-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schury K, Zimmermann J, Umlauft M, Hulbert AL, Guendel H, Ziegenhain U, Kolassa IT, 2017. Childhood maltreatment, postnatal distress and the protective role of social support. Child Abuse Negl. 67, 228–239. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selengia V, Thuy HNT, Mushi D, 2020. Prevalence and Patterns of Child Sexual Abuse in Selected Countries of Asia and Africa: A Review of Literature. Open Journal of Social Sciences 8, 146–160. 10.4236/jss.2020.89010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RC, Kauye F, Umar E, Vokhiwa M, Bunn J, Fitzgerald M, Tomenson B, Rahman A, Creed F, 2009. Validation of a Chichewa version of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) as a brief screening measure for maternal depressive disorder in Malawi, Africa. J. Affect. Disord 112, 126–134. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RC, Umar E, Tomenson B, Creed F, 2013. Validation of screening tools for antenatal depression in Malawi—A comparison of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Self Reporting Questionnaire. J. Affect. Disord 150, 1041–1047. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedo EA, Sumner SA, Msungama W, Massetti GM, Kalanda M, Saul J, Auld AF, Hillis SD, 2019. Childhood violence is associated with forced sexual initiation among girls and young women in Malawi: a cross-sectional survey. The Journal of pediatrics 208, 265–272. e261. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank, 2019. GDP per capita (current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?view=chart. (Accessed 19 September, 2021).

- Too EK, Abubakar A, Nasambu C, Koot HM, Cuijpers P, Newton CR, Nyongesa MK, 2021. Prevalence and factors associated with common mental disorders in young people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J. Int. AIDS Soc 24, e25705. 10.1002/jia2.25705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS, 2014. Fast Track: Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf. (Accessed 03 May, 2020).

- UNAIDS, 2019. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics - 2019 Fact sheet. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf. (Accessed 24 April, 2020).

- UNAIDS, 2020. Country factssheets: Malawi 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi. (Accessed 16 December, 2020).

- UNICEF Tanzania, Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Science, 2011. Violence against Children in Tanzania: Findings from a National Survey, 2009. Summary Report on the Prevalence of Sexual, Physical and Emotional Violence, Context of Sexual Violence, and Health and Behavioural Consequences of Violence Experienced in Childhood. https://evaw-global-database.unwomen.org/-/media/files/un%20women/vaw/full%20text/africa/tanzania%20violence%20against%20children%20survey%202009.pdf?vs=1424. (Accessed 22 October, 2021).

- Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB, 2014. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep 11, 291–307. 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Westhuizen C, Wyatt G, Williams JK, Stein DJ, Sorsdahl K, 2016. Validation of the Self Reporting Questionnaire 20-Item (SRQ-20) for Use in a Low- and Middle-Income Country Emergency Centre Setting. Int J Ment Health Addict 14, 37–48. 10.1007/s11469-015-9566-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderEnde K, Chiang L, Mercy J, Shawa M, Hamela J, Maksud N, Gupta S, Wadonda-Kabondo N, Saul J, Gleckel J, 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and HIV sexual risk-taking behaviors among young adults in Malawi. J Interpers Violence 33, 1710–1730. 10.1177/0886260517752153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Shirey K, Pence BW, Yao J, Thielman N, Whetten R, Adams J, Agala B, Ostermann J, O’Donnell K, Hobbie A, Maro V, Itemba D, Reddy E, Team CR, 2013. Trauma history and depression predict incomplete adherence to antiretroviral therapies in a low income country. PLoS One 8, e74771. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2018. Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/. (Accessed 13 October, 2021).

- Zhong Q-Y, Wells A, Rondon MB, Williams MA, Barrios YV, Sanchez SE, Gelaye B, 2016. Childhood abuse and suicidal ideation in a cohort of pregnant Peruvian women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 215, 501.e501–501.e5018. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zietz S, Kajula L, McNaughton Reyes HL, Moracco B, Shanahan M, Martin S, Maman S, 2020. Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and subsequent risk of interpersonal violence perpetration among men in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Child Abuse Negl 99, 104256–104256. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G, 2004. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol 159, 702–706. 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.