Abstract

Purpose

Long-term effects of being the primary caregiver of an older patient with cancer are not known. This study aimed to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in primary caregivers of patients aged 70 and older with cancer, 5 years after initial treatment. Secondly, to compare the HRQoL between former primary caregivers whose caregiving relationship had ceased (primary caregiver no longer directly assisting the patient because of patient death or removal to another city or admission to an institution) and current caregivers, and to determine the perceived burden of the primary caregivers.

Methods

Prospective observational study including primary caregivers of patients aged 70 and older with cancer. HRQoL and perceived burden were assessed using the SF-12 and Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) at baseline and 5 years after initial treatment.

Results

Ninety-six caregivers were initially included; at 5 years, 46 caregivers completed the SF-12 and ZBI between June 15 and October 26, 2020. Primary caregiver’s HRQoL scores had significantly decreased over time for physical functioning (mean difference = −10, p=0.04), vitality (MD= −10.5, p=0.02), and role emotional (MD= −8.1, p=0.01) dimensions. The comparison at 5 years according to caregiving status showed no difference for all HRQoL dimensions. There was no decrease in perceived burden at 5 years.

Conclusion

Some dimensions of HRQoL decreased at 5 years with a stable low perceived burden.

Trial registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-023-07594-w.

Keywords: Elderly, Cancer, Caregiver, Quality of life, Burden

Introduction

The aging of the population and increasing life expectancy have led to a growing incidence of cancer in older individuals (65% in men and 93% in women between 1990 and 2018) [1].

During cancer treatment, primary caregivers support patients both instrumentally and emotionally. Care-related tasks can cause burden and distress, which may impact the caregiver’s ability to support the patient.

Very often, being a primary caregiver, i.e., the person who has the duty of caring for someone else, leads to changes that can have a potentially negative impact on social life (activities, leisure) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which is a self-reported measure of the health-related well-being, including spirituality, health, activity level, social support, resources, satisfaction with personal accomplishments, and life situations [2–4]. In a recent study, 20% of caregivers remained burdened and distressed after the patient’s treatment had ended [5].

In primary caregivers, the potential negative impact of cancer care on HRQoL and perceived burden (usually defined as “the physical, psychological or emotional, social and financial problems that can be experienced by family members caring for impaired older adults”) has already been studied, in particular for anxiety and depression [6, 7]. Several associations have been identified between depression and HRQoL, such as sleep quality, burden, duration of caregiving, and caregiver unemployment [8, 9]. In 2014, the Geriatric Oncology Coordination Unit of Burgundy (GOCUB) carried out a study which identified several factors significantly associated with HRQoL in primary caregivers, namely age, perceived burden, and patient’s level of dependence [10]. Yet despite the known effects of caregiving, very few studies have assessed changes in long-term HRQoL and the perceived burden of primary caregivers of cancer patients. One exception is Kim et al.’s [11] prospective longitudinal study, which identified psychosocial factors predicting depressive symptoms in caregivers 5 years after their relative’s cancer diagnosis. If HRQoL and perceived burden were not directly studied, caregivers actively involved in cancer care at 5 years presented greater depressive symptoms, and it was suggested that they should benefit from programs to improve their symptoms [11]. The long-term impact of the continuity of the care relationship on the HRQoL has also not been studied.

This study aimed to determine the HRQoL of the primary caregivers of cancer patients aged 70 and older at 5 years. Secondly, to compare the HRQoL between former primary caregivers whose caregiving relationship had ceased (primary caregiver no longer directly assisting the patient because of patient death or removal to another city or admission to an institution) and current caregivers, and to determine the perceived burden of the primary caregivers.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The design of this study has previously been described by Germain et al. [10]. Briefly, it was an observational prospective multicenter study conducted by the GOCUB, including patients 70 years and older with cancer and their primary caregivers, from 1 June 2014 to 18 March 2015, with follow-up at follow-up 3 to 6 months after oncogeriatric care. In addition, in order to assess long-term HRQoL in primary caregivers, a final HRQoL assessment was conducted in the summer of 2020.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by a French ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Méditerranée N°2019-A03216-51) and by the French national data protection authority (CNIL-MR003 N°1989764). The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04478903).

Procedures

Patients 70 years and older who had a geriatric oncology consultation between 1 June 2014 and 18 March 2015 and were managed at the George Francois Leclerc Cancer Center or Dijon University Hospital, France, were included with their primary caregivers after providing written informed consent. HRQoL and burden were assessed in primary caregivers at baseline. A final assessment was performed 5 years after inclusion. To this end, the vital status of the primary caregivers was updated using data from the national statistics bureau (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques, INSEE).

Before sending questionnaires, INSEE data were used to establish whether the primary caregiver was still alive. Those who were still alive were called at their place of residence between 15 June and 7 July 2020 to obtain consent for participation. Non-responders were called again 2 months later for follow-up, and the inclusions were closed in December 2020.

Studied variables and endpoints

Patient information, such as cancer location, therapeutic goal (curative vs. palliative), comorbidities assessed using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) [12], and patient’s life expectancy using the Lee score or “4-year Mortality Index of older adults” [13] were collected at baseline from patient records. Caregivers’ gender, age, type of relationship with the patient (categorized into 3 groups: spouse, child, or other relative), marital status, and employment status were also recorded at baseline.

Five years after inclusion, a general information questionnaire was sent to the primary caregiver to update information about the patient’s vital status (categorized as alive vs deceased), the caregiving status (which was defined into 2 classes: “former caregiver” if the primary caregiver no longer directly assisted the patient due to death or removal to another city or admission to nursing home vs. “current caregiver” if the primary caregiver was still helping the patient), and any change in employment status from inclusion to summer 2020 (categorized into 2 classes: yes, if primary caregiver changed employment vs. no, if primary caregiver had the same job or employment situation). Whether the caregiver had any help with caregiving (categorized into 2 classes: yes, if caregivers received any kind of support such as help with household chores, psychological counselling vs. no, if they did not receive support) was ascertained. From a dichotomous question also found in the general questionnaire, whether primary caregivers were taking daily medication (categorized into 2 classes: yes, if primary caregiver took daily medication for any condition vs. no, if primary caregiver did not take any daily medication) was ascertained. Along with the general questionnaire, the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) from the Medical Outcomes Study and the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) were also sent.

SF-12

The SF-12 was used to assess the caregiver’s HRQoL [14]. It is a validated tool comprising twelve questions that generate eight scales, namely: physical functioning, role physical, role emotional, body pain, social functioning, mental health, vitality, and general health perception. All scales were scored according to the standard scoring method described in the SF-12 scoring manual [15]. Each score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better HRQOL. The SF-12 showed a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) coefficient ranging from 0.73 to 0.87 for the initial version and 0.879 for the French version [14, 16]. For this study, Cronbach’s alpha of all domains was calculated and was more than 0.70, confirming the internal consistency of the questionnaire in this population.

Zarit Burden Interview

Perceived burden was measured with the ZBI. This self-administered questionnaire contains 22 items exploring the consequences of caregiving on the physical, psychological, and social levels. The overall score is linked to the physical and behavioral dependence of the person being helped. The total score, which is the sum of the scores obtained for each of the 22 items, ranges from 0 to 88. A score less than or equal to 20 indicates a low burden, a score between 21 and 40 indicates a mild burden, between 41 and 60 a moderate burden, and > 60 a severe burden [17, 18]. The ZBI showed a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) coefficient between 0.83 and 0.91 for the initial version and 0.85 for the French version and test-retest reliability (intra-class correlation coefficient) of 0.89 [17, 19]. For this study, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated and was 0.93, confirming the internal consistency of the questionnaire in this population.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were described as means ± standard deviation (SD), medians, and ranges, while categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages. The characteristics of the PCs who participated at 5 years and their patients were described at baseline. Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact or chi2 tests for categorical variables were used to compare sociodemographic variables between respondents and non-respondents. HRQoL and perceived burden scores were generated, described at baseline and at 5 years. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare the difference between 5 years and baseline, due to low sample size. Following the guidelines from Osoba et al., the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was defined in this study as a mean difference (MD) of least 5 points in HRQoL and perceived burden between baseline and 5 years of follow-up [17]. A negative difference indicated a deterioration in HRQOL but an improvement in perceived burden while a positive difference indicated an improvement in HRQOL but a decline in perceived burden. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare HRQOL at 5 years according to the caregiving status, other sociodemographic variables were not tested. P value < 0.05 was set to define a statistically significant difference. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NA, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the primary caregivers

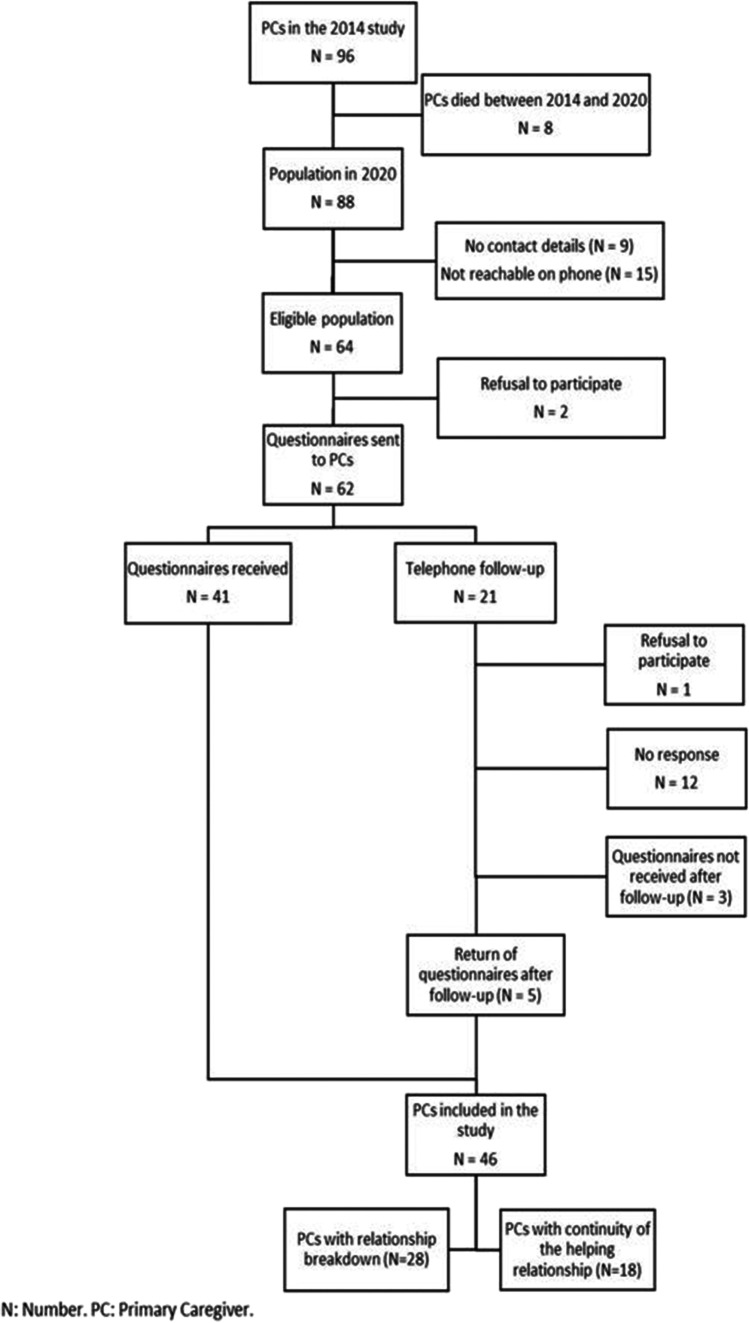

From 1 June 2014 to 18 March 2015, 96 caregivers were initially included. In 2020, after the data were updated, 8 caregivers had died, 24 were lost to follow-up, and 2 refused to pursue their participation. HRQoL questionnaires were then sent to the 62 caregivers who agreed to participate. Of these, 46 completed and returned their questionnaires, corresponding to a response rate of 71.87%, and were retained for the analyses (Fig. 1). At 5 years of follow-up, 28 (60.86%) caregivers were no longer directly assisting the patient [25 patients had died, two patients had been moved to another city, and one had entered a nursing home] and 18 individuals (39.14%) reported that they were still the primary caregiver (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

There is only one significant difference between responders at 5 years and no responders at 5 years (supplementary data). Patients of responders were most managed in a curative context (82.61% vs 61.22%, p=0.02).

In our study, the primary caregiver mean age was 66.8 years, over 58% of primary caregivers were women, and 54.35% of primary caregivers were patients’ children (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of primary caregivers and patients

| Variable | Total (N=46) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Age | Mean ± SD | 66.76 ± 12.7 | |

| Median (min–max) | 65.00 (38–92) | ||

| Time since 2014 | Mean ± SD | 5.64 ± 0.23 | |

| Median (min–max) | 5.58 (5.34–6.05) | ||

| Gender | Male | 19 | 41.30 |

| Female | 27 | 58.70 | |

| Relation with patient | Spouse | 13 | 28.26 |

| Child | 25 | 54.35 | |

| Other relative/friend/other | 8 | 17.39 | |

| Caregiver marital status | Married | 35 | 76.09 |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 11 | 23.91 | |

| Professional situation | In activity | 30 | 65.22 |

| Without profession | 16 | 34.78 | |

| Change in employment status | Yes | 9 | 19.57 |

| No | 37 | 80.43 | |

| Vital status of the patient | Alive | 21 | 45.65 |

| Dead | 25 | 54.35 | |

| Assistance in the caring role | Yes | 15 | 32.61 |

| No | 31 | 67.39 | |

| Using a daily medication | Yes | 19 | 41.43 |

| No | 27 | 58.67 | |

| Patient curative context | Yes | 38 | 82.61 |

| No | 08 | 17.39 | |

| CIRS-G N ≥3 | Yes | 36 | 78.26 |

| No | 10 | 21.74 | |

| Patient’s Lee mortality index | Low/medium risk | 14 | 30.43 |

| High/very high risk | 32 | 69.57 | |

| Patient’s cancer location | Breast | 15 | 32.61 |

| others | 31 | 67.39 | |

CIRS-G Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric, N number, SD standard deviation, min minimum, max maximum

Analysis of health-related quality of life over time

At baseline, the best HRQOL score was physical functioning dimension with a mean score of 84.5 (SD=26.2) and the worst HRQOL score was mental health with a mean score of 59.3 (23.6) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Health-related Quality of Life and Perceived Burden scores at baseline and 5 years

| Baseline (N=46) | 5 years (N=46) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Mean (SD) | Median (min–max) | N | Mean (SD) | Median (min–max) | MD | P* |

|

Health-related Quality of Life (SF-12) | ||||||||

| General health | 44 | 63.25 (24.22) | 60 (0–100) | 46 | 60.43 (17.82) | 60 (25–100) | −2.82 | 0.57 |

| Physical functioning | 44 | 84.47 (26.17) | 100 (0–100) | 46 | 74.45 (30.50) | 87.50 (0–100) | −10.02 | 0.04 |

| Role physical | 44 | 73.54 (26.89) | 75 (0–100) | 46 | 66.30 (24.28) | 62.50 (0–100) | −7.24 | 0.08 |

| Role emotional | 44 | 74.13 (25.35) | 75 (12.5–100) | 46 | 66.03 (23.96) | 62.50 (12.5–100) | −8.1 | 0.01 |

| Bodily pain | 44 | 81.98 (19.15) | 75 (25–100) | 46 | 75.00 (27.39) | 75.00 (0–100) | −6.98 | 0.09 |

| Mental health | 44 | 59.30 (23.63) | 62.50 (0–87.50) | 46 | 64.67 (20.63) | 62.50 (12.50–100) | 5.37 | 0.12 |

| Vitality | 44 | 61.04 (24.58) | 75 (0–100) | 46 | 50.54 (27.63) | 50.00 (0–100) | −10.5 | 0.02 |

| Social functioning | 44 | 70.93 (27.23) | 75 (0–100) | 46 | 72.83 (22.25) | 75.00 (25–100) | 1.90 | 0.85 |

|

Perceived Burden (Zarit) |

44 | 18.26 (12.94) | 18 (0–48) | 18¥ | 14.76 (12.63) | 13 (0–34) | −3.50 | 0.41 |

MD mean difference. MD was calculated as the difference between 5 years’ score and baseline score

*p from Wilcoxon rank test, ¥ caregivers still in a caregiving relationship, significant results are highlighted in bold

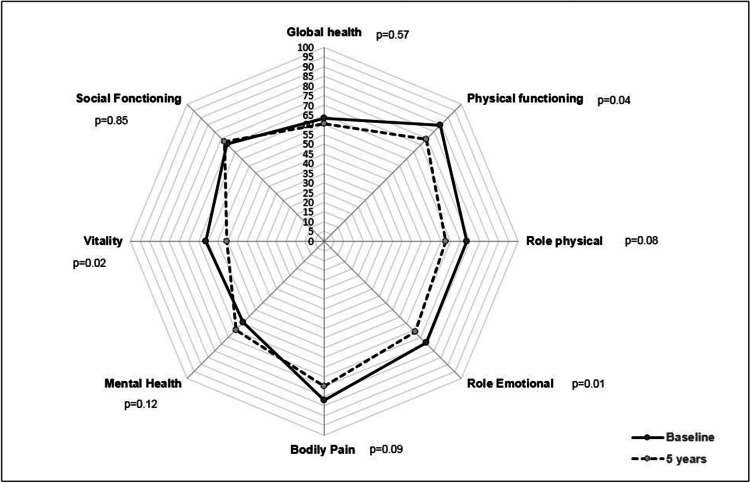

At 5 years with respect to baseline score, physical functioning (MD= −10, p=0.04), vitality (MD= −10.5, p=0.02), and role emotional (MD= −8.1, p=0.01) were statistically significant and clinically meaningful and all of 3 dimensions were deteriorated (Table 2, Fig. 2). However, although not statistically significant (p>0.05), mental health dimension showed clinical improvement (MD=5.4, p=0.68) while role physical showed a clinical deterioration (MD= −7.2, p=0.17).

Fig. 2.

Baseline and 5-year HRQOL score radar chart

The comparison at 5 years according to caregiving status showed no difference for all HRQoL dimensions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the primary caregiver’s quality of life scores according to the caregiving status at 5 years

| Variable | Current caregivers (N=18) |

Former caregivers (N=28) |

MD | p* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SD | Median (min–max) | N | Mean ± SD | Median (min–max) | |||

| SF-12 | ||||||||

| General health | 18 | 58.33 ± 18.00 | 60 (25–85) | 28 | 61.78 ± 17.91 | 60 (25–100) | 3.45 | 0.62 |

| Physical functioning | 18 | 73.61 ± 31.47 | 87.50 (25–100) | 28 | 75.00 ± 30.43 | 87.50 (0–100) | 1.39 | 0.89 |

| Role physical | 18 | 63.19 ± 29.23 | 62.50 (0–100) | 28 | 68.30 ± 20.83 | 75 (25–100) | 5.11 | 0.69 |

| Role emotional | 18 | 65.27 ± 28.94 | 68.75 (12.50–100) | 28 | 66.52 ± 20.71 | 62.5 (25–100) | 1.25 | 0.84 |

| Bodily pain | 18 | 76.39 ± 29.04 | 87.50 (25–100) | 28 | 74.11 ± 26.77 | 75 (0–100) | −2.28 | 0.67 |

| Mental health | 18 | 68.05 ± 23.57 | 75 (12.50–100) | 28 | 62.50 ± 18.63 | 62.50 (25–100) | −5.55 | 0.31 |

| Vitality | 18 | 51.39 ± 33.73 | 50 (0–100) | 28 | 50.00 ± 23.57 | 50 (0–75) | −1.39 | 0.86 |

| Social functioning | 18 | 77.78 ± 20.81 | 75 (50–100) | 28 | 69.64 ± 22.93 | 75 (25–100) | −8.14 | 0.24 |

*p from Mann-Whitney test; MD mean difference between former and current caregiver status

Analysis of perceived burden over time

The mean perceived burden score at baseline was 18.26 (12.94). There was not a significant or clinically meaningful difference in this score over time (MD= −3.50, p=0.41) (Table 2).

Discussion

Concerning the caregiver’s HRQoL, significant decreases over time were observed for physical functioning, vitality, and role emotional. A study investigated QoL in the caregivers of patients of all ages 3 months after the end of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and showed that caregivers remained burdened and distressed [5].

A clinically meaningful increase was observed, without statistical significance, for mental health. These results are only somewhat consistent with the rare previous studies [5, 11]. The present study considered caregiving status whereas other studies, such as Kim et al. [11], only included current caregivers, which could explain some differences. In comparison with non-caregivers of the same age, another study showed that caregivers of older adults with cancer were more likely to experience a deterioration of their physical health and to have poor health-related behaviors [20]. The clinical improvement observed in the mental health of caregivers over time could be related to the time elapsed since the initial diagnosis. These findings are concordant with the literature since increasing patient age and time since diagnosis [6 months] has been associated with reduced levels of caregiver depression [21]. Several explanations for this mental health improvement could be advanced, e.g., accommodation to reality, development of coping strategies to deal with reality, positive effects of psychotherapy, the effectiveness of antidepressant therapy, or the implementation of supportive care at home. Each of these hypotheses should be further explored.

A recent study conducted among caregivers of older hospitalized cancer patients found that lower caregiver QoL with poorer mental health and less social support was associated with poorer patient Karnofsky performance status [22]. For Jepson et al. [23], caregivers with physical issues were at risk of psychological morbidity, which can potentially appear 3 months after initial treatment. This delayed effect may reflect the replacement of initial optimism by discouragement as the reality of long‐term illness sets in [23]. For Raveis et al. [24], caregivers with health-limiting conditions were at risk of higher anxiety levels, but a low burden tended to be associated with better mental health (p = 0.027). The results presented in this work did not test interactions between the caregiver’s physical issue and mental health. However, since the burden did not differ, we could speculate that caregivers developed coping strategies, resilience, or effective perceived social support that counteracts discouragements and could improve mental health [24, 25].

In the present study, HRQoL did not differ significantly between current and former caregivers 5 years after enrollment, but there were clinically meaningful differences for some dimensions (increase in the physical role, decrease in mental health and social functioning for the former caregivers), probably linked to our small sample. “Role physical” describes the discomfort of the physical state in daily activities, which suggests that the helping relationship had a negative impact on the physical capacities of caregivers [15]. Long-term cancer caregivers have been shown to have more depressive symptoms [26]. It can be only speculated that the clinical decline in mental health and social functioning after the termination of the helping relationship may be related to the loss of the cancer patient, or to “caregiver burnout” before termination, which had not been studied [27].

The results showed that 19.6% of primary caregivers had changed their professional situation in the last 5 years (Table S2). An American study showed that 39.8% of 922 caregivers had quit or retired early due to caregiving demands. Among employed caregivers, 52.4% reported that caregiving had impacted their work [28].

In this study, 33% of caregivers received outside help in their caring role, which is similar to the literature (32% to 52% of professional help at home) [29]. In the initial 2014 study, 59% of primary caregivers had help [10]. Recent studies have demonstrated the impact of providing support for caregivers. Hendrix et al. [30] showed improvements in caregiver stress after training with a nurse. Several other studies have highlighted the benefit of home-care interventions [29, 30]. Therefore, one potential way to improve QoL for primary caregivers would be to offer help at the patient’s home.

It has been shown that psychological distress in the bereaved is linked to the care that they provided during the patient’s end of life [31]. Many studies have evaluated psychosocial interventions that can help reduce caregiver burden and improve HRQoL [32, 33]. This supports the importance of follow-up and access to psychological support. In particular, general practitioners have a major role in the management of bereaved patients.

In France, the national cancer plan for 2014–2019 aimed to prevent caregiver exhaustion and isolation by improving support and diversifying and increasing options for respite by according new benefits and facilitating a return to professional life [34]. In 2014, the French authority for health, Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS), established guidelines to help professionals care for the caregivers of patients with chronic diseases [35]. There is no internationally recognized recommendation for providing care for the caregivers of patients with cancer; therefore, a lower HRQoL 5 years after initial treatment, although the sample size is small and the effect modest, highlights the need to consider caregiver care from the time of cancer diagnosis in clinical research.

Finally contrary to HRQoL, no difference was observed at 5 years regarding burden, nor in a statistical or clinical manner.

Our study has some limitations. Despite a good response rate, the study included a small number of participants. Several patients were lost to follow-up between the two periods, which may have led to a lack of statistical power. Thus, due to the low number of participants, we could not provide a multivariate analysis and our results must be carefully interpreted. Furthermore, an “age effect” 5 years later on the observed quality-of-life trends in the univariate analysis cannot be excluded. Data concerning the caregiver’s comorbidities or clinical status were not collected, which could interfere with the HRQoL and perceived burden. Moreover, some intrinsic factors, which have been not tested, may influence caregiver HRQoL.

These preliminary results warrant confirmation in larger prospective studies to assess the benefits of specific elderly cancer patient’s caregiver’s care. Finally, it should be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the period of this study. Several studies have reported significant increases in anxiety during the pandemic which may have influenced our results [36, 37]. However, there is a paucity of literature on the consequences of long-term caregiving, particularly in elderly cancer patients and our work is one of the first of its kind.

Conclusions

Caregivers of older patients with cancer are important for the success of treatment plans, yet few studies consider the quality of life in this population. Five years after their initial evaluation, some dimensions of HRQoL of caregivers decreased (physical functioning, vitality, and role emotional) regardless of caregiving status. Perceived burden did not differ. These preliminary results warrant confirmation in larger prospective studies including sociodemographic and clinical data to better understand the specific support that could improve the quality of life in caregivers of older patients with cancer.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the primary caregivers for their collaboration, to Fiona Ecarnot, PhD (EA3920, University of Franche-Comté, Besancon, France) for translation and review, and to Ms. Suzanne Rankin, a native English speaker who read and corrected the manuscript.

Author contribution

Conceptualization, Jérémy Barben, Oumar Billa, Leila Bengrine-Lefevre, Tienhan Sandrine Dabakuyo-Yonli, and Valérie Quipourt; methodology, Jérémy Barben, Oumar Billa, Leila Bengrine-Lefevre, Tienhan Sandrine Dabakuyo-Yonli, and Valérie Quipourt; validation, Jérémy Barben, Oumar Billa, Patrick Manckoundia, and Thomas Collot; formal analysis, Jérémy Barben, Oumar Billa; investigation, Julie Collot; data curation, Julie Collot; writing—original draft preparation, Jérémy Barben, Oumar Billa, Julie Collot; writing—review and editing, Jérémy Barben, Oumar Billa, Leila Bengrine-Lefevre, Tienhan Sandrine Dabakuyo-Yonli, Thomas Collot, Patrick Manckoundia, and Valérie Quipourt; supervision, Valérie Quipourt. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Data are not available.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by a French ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Méditerranée N°2019-A03216-51) and by the French national data protection authority (CNIL-MR003 N°1989764). The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04478903).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jérémy Barben and Oumar Billa have equal contributions.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries CA: A. Cancer J Clinicians. 2018;6:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen SM, Goldscheider F, Ciambrone DA. Gender Roles, Marital intimacy, and nomination of spouse as primary caregiver. The Gerontologist. 1999;39(2):150–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stolz-Baskett P, Taylor C, Glaus A, Ream E. Supporting older adults with chemotherapy treatment: a mixed methods exploration of cancer caregivers’ experiences and outcomes. European J Oncol Nursing. 2021;50:101877. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chappell NL, Reid RC. Burden and well-being among caregivers: examining the distinction. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):772–80. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langenberg SMCH, Poort H, Wymenga ANM, de Groot JW, Muller EW, van der Graaf WTA, et al. Informal caregiver well-being during and after patients’ treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a prospective, exploratory study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2021;29(5):2481–91. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05738-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver weil-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. The Gerontologist. 1986;26(3):253–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ankri J, Andrieu S, Beaufils B, Grand A, Henrard JC. Beyond the global score of the Zarit Burden Interview: useful dimensions for clinicians. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):254–60. doi: 10.1002/gps.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fekete C, Tough H, Siegrist J, Brinkhof MW. Health impact of objective burden, subjective burden and positive aspects of caregiving: an observational study among caregivers in Switzerland. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017369. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng H, Chuang D, Yang F, Yang Y, Liu W, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e11863. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germain V, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Marilier S, Putot A, Bengrine-Lefevre L, Arveux P, et al. Management of elderly patients suffering from cancer: assessment of perceived burden and of quality of life of primary caregivers. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(3):220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, Shaffer KM, Carver CS, Cannady RS. Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms among cancer caregivers 5 years after the relative’s cancer diagnosis. J Consult Clin Psyc. 2014;82(1):1–8. doi: 10.1037/a0035116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 1968;16(5):622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295(7):801. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries. J Clin Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1171–8. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware J (2005) How to score version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (with a supplement documenting version 1). In: Lincoln RI, Boston Mass: QualityMetric Inc. Health Assessment Lab. QualityMetric Incorporated, New England Medical Center Hospital, Health Assessment Lab

- 16.Protopopescu C, Boyer S, Marcellin F, Carrieri M-P, Koulla-Shiro S, Spire B. Validation de l’échelle de qualité de vie SF-12 chez des patients infectés par le VIH au Cameroun (enquête EVAL–ANRS 12–116) Revue d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2011;59:S9. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2011.02.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–55. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galindo-Vazquez O, Benjet C, Cruz-Nieto MH, Rojas-Castillo E, Riveros-Rosas A, Meneses-Garcia A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Zarit Burden Interview in Mexican caregivers of cancer patients: Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) in Mexican primary caregivers. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(5):612–5. doi: 10.1002/pon.3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hébert R, Bravo G, Girouard D. Fidélité de la traduction française de trois instruments d’évaluation des aidants naturels de malades déments. Can J Aging. 1993;12(3):324–37. doi: 10.1017/S0714980800013726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadambi S, Loh KP, Dunne R, Magnuson A, Maggiore R, Zittel J, et al. Older adults with cancer and their caregivers - current landscape and future directions for clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(12):742–55. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0421-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldzweig G, Schapira L, Baider L, Jacobs JM, Andritsch E, Rottenberg Y. Who will care for the caregiver? Distress and depression among spousal caregivers of older patients undergoing treatment for cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019;27(11):4221–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu T, Nathwani N, Loscalzo M, Chung V, Chao J, Karanes C, et al. Understanding caregiver quality of life in caregivers of hospitalized older adults with cancer. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2019;67(5):978–86. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jepson C, McCorkle R, Adler D, Nuamah I, Lusk E. Effects of home care on caregivers’ psychosocial status Image: the. J Nursing Scholarship. 1999;2:115–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raveis VH, Karus D, Pretter S. Correlates of anxiety among adult daughter caregivers to a parent with cancer. J Psyc Oncol. 1999;17(3–4):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong HL, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Sambasivam R, Fauziana R, Tan M-E, et al. Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1616-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Carver CS, Cannady RS. Effects of caregiving status and changes in depressive symptoms on development of physical morbidity among long-term cancer caregivers. Health Psychol. 2017;36(8):770–8. doi: 10.1037/hea0000528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gérain P, Zech E. Informal caregiver burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1748. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longacre ML, Valdmanis VG, Handorf EA, Fang CY (2016) Work impact and emotional stress among informal caregivers for older adults. J Gerontol Ser B: Psych Sci Soc Sci gbw027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Dionne-Odom JN, Applebaum AJ, Ornstein KA, Azuero A, Warren PP, Taylor RA, et al. Participation and interest in support services among family caregivers of older adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2018;27(3):969–76. doi: 10.1002/pon.4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendrix CC, Bailey DE, Steinhauser KE, Olsen MK, Stechuchak KM, Lowman SG, et al. Effects of enhanced caregiver training program on cancer caregiver’s self-efficacy, preparedness, and psychological well-being. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24(1):327–36. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2797-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCorkle R, Robinson L, Nuamah I, Lev E, Benoliel JQ. The effects of home nursing care for patients during terminal illness on the bereaved’s. Psyc distress: Nursing Res. 1998;47(1):2–10. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badr H, Krebs P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer: couples meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(8):1688–704. doi: 10.1002/pon.3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trevino KM, Healy C, Martin P, Canin B, Pillemer K, Sirey JA, et al. Improving implementation of psychological interventions to older adult patients with cancer: convening older adults, caregivers, providers, researchers. J Geriatric Oncol. 2018;9(5):423–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Observatoire sociétal des cancers (2015) Rapport sur les aidants [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ligue-cancer.net/sites/default/files/docs/observatoire_societal_des_cancers_rapport_2015_0.pdf

- 35.ANESM (2014) Le soutien des aidants non professionnels. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-03/ane-trans-rbpp-soutien_aidants-interactif.pdf

- 36.Ng KYY, Zhou S, Tan SH, Ishak NDB, Goh ZZS, Chua ZY, et al. Understanding the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers in Singapore. JCO Global Oncology. 2020;6:1494–509. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chia JMX, Goh ZZS, Chua ZY, Ng KYY, Ishak D, Fung SM, et al. Managing cancer in context of pandemic: a qualitative study to explore the emotional and behavioural responses of patients with cancer and their caregivers to COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e041070. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are not available.