Abstract

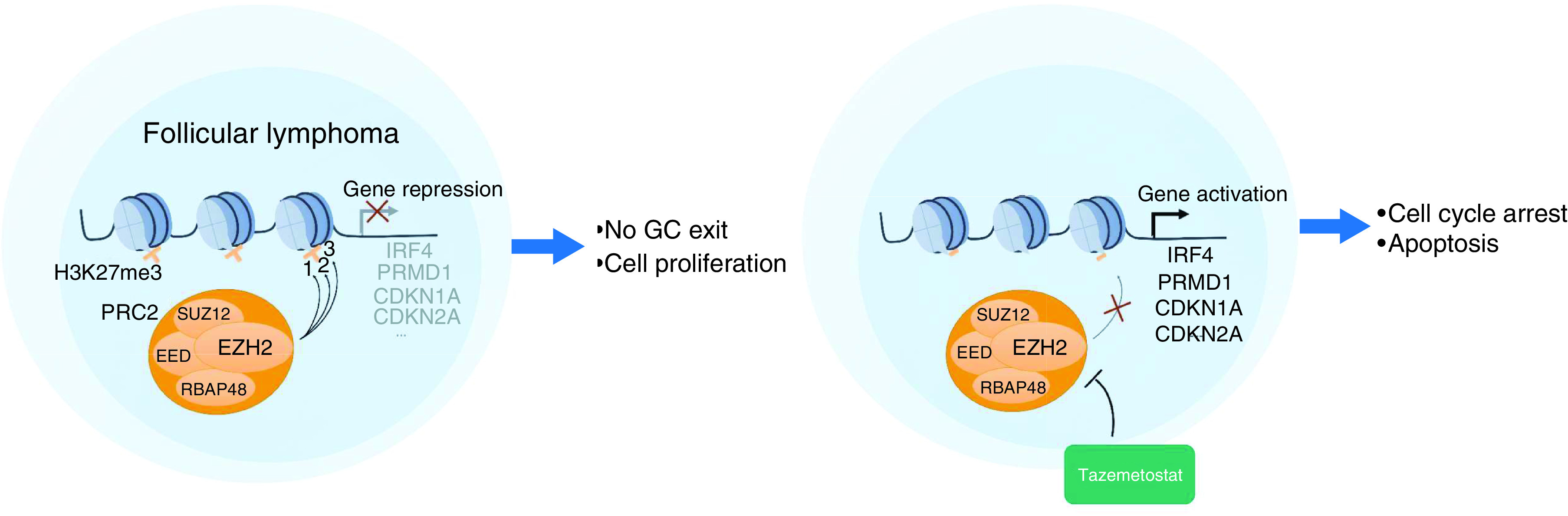

Epigenetic alterations are major drivers of follicular lymphomagenesis, and these alterations are frequently caused by mutations in or upregulation of EZH2, a histone methyltransferase responsible for PRC2-mediated gene repression. EZH2 hyperactivation increases proliferation of B cells and prevents them from exiting the germinal center, favoring lymphomagenesis. The first FDA-approved EZH2 inhibitor is tazemetostat, which is orally available and targets both mutant and wild-type forms of the protein to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of lymphoma cells in preclinical models. Phase II trials have shown objective response rates of 69% for patients with lymphoma-carrying EZH2 mutations and 35% for those with wild-type EZH2 without major toxicity, leading to tazemetostat approval for this cancer by the US FDA in June 2020.

Keywords: : B cells, enhancer of zest homolog 2, epigenetics, follicular lymphoma, germinal center, histone methylation, tazemetostat

Lay abstract

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a subtype of B-cell cancer. Initial prognosis of this disease is favorable as first-line treatments provide responses lasting 10 years on average. However, most patients will experience relapse and subsequent treatments are not as efficient nor as well tolerated as the first ones. An important driver of FL is a gene called EZH2 that makes B cells proliferate, either because of mutations that increase its activity or because of a net increase in its concentration in lymphoma cells. Tazemetostat is a drug that was designed to inhibit EZH2 protein and thus lymphoma cell growth. Phase I and II studies have been completed for this drug showing a good safety profile. In Phase II, reponses were seen in 69% of patients who have the EZH2 mutations and 35% of the other patients. The US FDA has approved tazemetostat for patients with FL who have had at least two previous treatments and harbor the EZH2 mutations, or for patients with FL who have no other therapeutic options. However, the drug has not yet been approved in Europe. Randomized trials and long-term follow-up will be of interest to make sure this drug is efficient and safe enough to be given to patients in earlier lines of treatment or in combination with other active agents used to treat patients with FL.

Graphical abstract

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is an indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma arising from germinal center (GC) B cells. Though FL demonstrates high response rates to first-line treatments and the median progression-free survival (PFS) is almost 10 years, most patients will ultimately experience a relapse. Subsequent lines of chemotherapy are known to be less efficient and many FLs become resistant to both chemotherapy and anti-CD20 antibodies, indicating a need for new therapeutic options.

The first oncogenic event in FL is the well-known t(14:18) translocation that leads to overexpression of the antiapoptotic BCL2 protein. However, this translocation can be found in the peripheral blood of up to 23% of healthy patients, indicating that it is not sufficient to drive lymphomagenesis alone [1]. Instead, the major driver of follicular lymphomagenesis is epigenetic deregulation [2,3]. Indeed, extensive genome sequencing has found that at least one gene related to epigenetic regulation is mutated in virtually every FL biopsy sample [4–6]. Mutations affect genes encoding histone acetyltransferases (CREBBP and EP300), histone methyltransferase (EZH2 and KMT2D), nucleosome remodeling complex proteins (ARID1A, ARID1B and BCL7A), histone H1 and H2 themselves, or transcription factors (MEF2B). Among these genes, the histone methyltransferase EZH2 is mutated in 22–28% of FL cases [5,7–9]. EZH2 mutations are mostly clonal and may appear at different stages of FL development [10]. Interestingly, these mutations are also found in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) arising from GC B cells but not in DLBCL of the activated B-cell subtype. Moreover, EZH2 mutations are stable during transformation from FL to DLBCL and believed to occur in a common progenitor clone [6,11]. Patients with EZH2-mutated FL tend to have a significantly better prognosis when treated in first line with immunochemotherapy than other patients, though the underlying mechanism is unknown [5,8]. This mutation status represents a favorable prognostic factor in the m7-FLIPI index [5]. Of note, the EZH2 gene is amplified in a small proportion (15%) of patients with FL, eventually coexisting with an activating mutation of the gene. Tumors with EZH2 amplification share identical transcriptional profiles with EZH2-mutated FL, and patient outcome also appears similar [8].

The EZH2 protein is a component of the PRC2, together with SUZ12, EED and RbAp48, and catalyzes the mono-, di- and trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone 3 (H3K27). H3K27me3 is a repressive epigenetic mark that favors a closed chromatin state and inhibits gene transcription. An excess of H3K27me3 is commonly found in many different cancer types, including FL, and is often associated with EZH2 mutations or EZH2 overexpression [12]. In contrast, a significant proportion of myeloid leukemias and T-cell lymphoblastic leukemias harbor distinct homozygous inactivating EZH2 mutations and decreased H3K27 methylation [13], suggesting that precise H3K27 methylation control is critical in preventing tumorigenesis.

In GC B cells, EZH2 is highly upregulated and plays a critical role in the GC reaction by hypermethylating H3K27 at several target genes involved in cell cycle inhibition (CDKN1A and CDKN2A), plasma cell differentiation (PRMD1, IRF4 and CD138) and GC exit (CD40, IL10 and NFKB) [14–16]. EZH2 is also essential for the protection of GC B cells from apoptosis induced by AID-linked DNA damage.

EZH2 mutations occurring in lymphomas affect most frequently the SET domain of the protein responsible for the methylation reaction [17,18]. Several mutations lead to an amino acid change at tyrosine 646 (Y646N, Y646S and Y646F) but other mutations have also been described at A687 and A697 [7,19]. These gain-of-function mutations lead to a hypermorphic protein that has a higher affinity for H3K27me2 and increased ability to catalyze the reaction from dimethylated to trimethylated H3K27 [20,21]. Increase in H3K27me3 further represses transcription of EZH2 target genes, especially cell cycle regulation and GC exit genes [20,21], thus promoting proliferation and blocking differentiation of GC B cells toward memory or plasma cells. More recent studies show that mutant EZH2 can also upregulate gene expression by redistributing H3K27 methylation throughout the genome, suggesting a neomorphic role of the mutant protein rather than simple hyperactivity [22]. EZH2 mutations cooperate with BCL2 rearrangement [23] and BCL6 protein to drive lymphomagenesis [24].

EZH2 lymphoid mutations are also associated with decreased MHC-I and MHC-II expression in GC DLBCL [25] and could play an important role in tumor immune escape [26]. Recent data also indicate that EZH2 mutation reshapes the immune microenvironment of B cells in GCs by enabling those B cells to become less dependent on T-cell help [27]. Furthermore, EZH2 is also known to modulate T-cell functions and differentiation, as the protein is ubiquitous and thus expressed in all immune cells. Specifically EZH2 represses Th1 and Th2 differentiation [28], promotes Tfh differentiation [29] and is necessary for Treg cell maintenance [30].

Considering these functions, targeting EZH2 seems likely to reduce FL cells’ proliferation, induce their apoptosis and augment their immunogenicity. Several inhibitors of EZH2 have thus been designed, targeting both wild-type (WT) and mutant forms and have been shown to efficiently inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of B-cell lymphoma in cell culture and xenograft models [31–33]. Among them, tazemetostat (TAZVERIK®, formerly EPZ-6438) is most advanced in clinical trials, and results so far demonstrate promising activity in patients with relapsed or refractory FL. In this paper, we will review current data on tazemetostat safety and efficacy, focusing on FL.

Overview of the field

Selection of second-line treatment for FL depends on the outcome of first-line therapy. Conventional chemotherapy, either bendamustine or CHOP in combination with an anti-CD20 antibody, is recommended for patients with a high tumor volume or symptomatic disease. Substituting obinutuzumab in place of rituximab when the disease becomes refractory to the latter can be beneficial [34]. Intensive chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation has been proposed in patients with early progression [35,36]. A second option consists of the immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide in combination with rituximab or obinutuzumab [37,38]. For further lines of treatment, the selective PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib has shown interesting activity [39,40]. Three new PI3K inhibitors, copanlisib, duvelisib and umbralisib, are also approved for third and subsequent lines by the US FDA [41,42]. Key results for these treatments in clinical trials are presented in Table 1. These drugs are associated with substantial adverse events, some of which are related to on-target activity, preventing their prolonged administration in the majority of treated patients. Other agents have shown activity in FL but are still under development, including polatuzumab [43], magrolimab [44], inhibitors of BCL2 [45], bispecific antibodies, CD19 CAR-T cells [46] and other PI3Kδ inhibitors [47]. It should be noted that some patients with FL, even when presenting relapsed or refractory disease, may still be able to live many years with their disease or benefit of prolonged treatment-free intervals. In this context, the optimal sequencing and long-term benefit of new therapeutic agents evaluated in Phase II studies remain to be fully determined.

Table 1. . Efficacy results of single agents and associations in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma.

| Agent or regimen evaluated | Prior lines (n); median (range) | CRR, % | ORR, % | Duration of response (months) | Median PFS (months) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenalidomide | NA | 20% | 53% | NA | 13 (TTP) | [65] |

| Bendamustine | 2 (0–6) | 15% | 74% | 9.2† | 9.3† | [66] |

| Obinutuzumab | 2 (1–7) | 9% | 44% | NA | 17.6 | [34] |

| Idelalisib | 4 (2–12) | 13.9% | 55.6% | 10.8 | 11 | [40] |

| Copanlisib | 3 (2–9) | 14% | 59% | 12.2 | 11.2 | [41] |

| Duvelisib | NA | 7%† | 47%† | NA | 14.7† | [42] |

| Lenalidomide + rituximab | 1 | 34% | 78% | 37 | 39 | [37] |

| Lenalidomide + obinutuzumab | 2 (1–3) | 27% | 79% | >24 | >24 | [38] |

| Obinutuzumab + bendamustine | 2 (1–NA)‡ | 17% | 68% | NA | 25 | [66,67] |

Data are presented for all indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients included in the study.

Eligible patients were Rituximab-refractory.

CRR: Complete response rate; ORR: Objective response rate; PFS: Progression-free survival; TTP: Time to progression.

Introduction to the compound

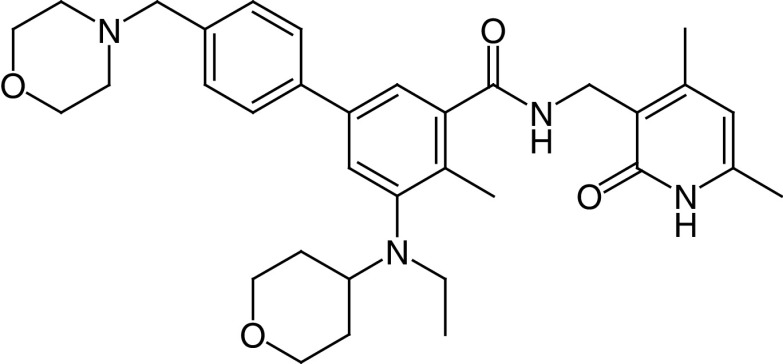

Tazemetostat (EPZ-6438) is similar in structure to the EPZ005687compound [32], one of the first oral EZH2 inhibitors to show antitumor activity in lymphoma. This compound targets both the WT and Y641 mutant forms of the enzyme [48]. Its activity was first reported in malignant rhabdoid tumors, which are also highly dependent on EZH2 [49]. Tazemetostat’s chemical structure is (N-((4,6-dimethyl-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridin-3-yl)methyl)-5-(ethyl(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)amino)-4-methyl-4′-(morpholinomethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxamide) (Figure 1). It inhibits EZH2 activity with an inhibition constant (Ki) value of 2.5 ± 0.5 nM, in a competitive mechanism with S-adenyl methionine, one of EZH2’s substrates. This compound has 35-fold selectivity for EZH2 versus EZH1 and inhibits EZH2 >4500-fold more potently compared with other histone methyltransferases in vitro.

Figure 1. . Chemical structure of tazemetostat.

Pharmacodynamics

Tazemetostat reduces H3K27 methylation with similar potency in lymphoma cell lines regardless of EZH2 mutational status with an IC50 value of 9 nM (IC95: 2–38). The compound directly decreases the various methylated forms of H3K27 (H3K27me3, H3K27me2 and H3K27me1) resulting in derepression of PRC2 target genes, without decreasing total H3 concentration or other histone methylation marks, though it does lead to a slight increase in H3K27 acetylation, another epigenetic mark known to activate gene transcription [48]. In GC-derived lymphoma cell cultures, tazemetostat reduces cell proliferation after 4–7 days and has a cytotoxic effect after prolonged exposure for at least 11 days. Tazemetostat also inhibits tumoral growth in murine xenograft models containing the EZH2 Y646 or A682G mutation [48]. Most cell lines harboring an EZH2 mutation are more sensitive to the antiproliferative and antiapoptotic effect than WT cell lines, which is also true of other EZH2 inhibitors, suggesting that EZH2-mutant lymphomas are more dependent on EZH2 activity for proliferation and survival [31]. The antiproliferative effect correlates with decreased gene expression in the cell cycle and spliceosome pathways. EZH2 also induces differentiation of B cells by upregulating memory B-cell gene sets, including PRDM1/BLIMP1 [50]. Interestingly, much of the cytotoxic and growth-inhibitory effects of EZH2 inhibitors seems to be due to insufficient compensatory B-cell activation signaling [50].

H3K27 methylation upon tazemetostat treatment has been assessed in humans via skin biopsies of patients included in the Phase I study. Tazemetostat treatment induced a dose-dependent reduction in the percentage of H3K27me3-positive cells in the stratum spinosum of the skin. Maximal H3K27me3 decreases were seen with doses of 800 mg twice daily, supporting the selection of this dosing schedule for Phase II studies [51].

Tazemetostat was shown to restore MHC-I and MHC-II expression in EZH2-mutant but not WT DLBCL cell lines [25]. This compound also restored epigenetically silenced CD58, a common immune escape mechanism in lymphoma [52]. Altogether, these data suggest that tazemetostat’s efficacy may also result from an enhanced antitumor immune response, possibly irrespective of EZH2 mutational status.

Pharmacokinetics & metabolism

Tazemetostat is administered as a Hbr salt twice daily in continuous 28-day cycles at 800 mg twice daily as determined by the Phase I study. Tazemetostat mean absolute oral bioavailability is only 33% [49]. It is metabolized by CYP3A to form EPZ-6930 and EPZ006931, two inactive major metabolites. EPZ-6930 is further metabolized by CYP3A. The predominant metabolic reaction of tazemetostat is N-dealkylation of the aniline nitrogen that leads to the loss of the ethyl group to form EPZ-6930 (also referred to as ER-897387), the tetrahydropyran moiety EPZ006931 (also referred to as ER-897388) and sequentially both functionalities EPZ034163 (also referred to as ER-897389). These three metabolites, especially EPZ-6930 and EPZ006931, accounted for the major circulating components derived from tazemetostat in humans as well as in rats and monkeys. However, these metabolites are not expected to exert meaningful pharmacological effects in vivo because they were markedly less potent than tazemetostat in inhibiting EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 formation (by ~100-fold lower).

Because of autoinduction of tazemetostat metabolism by CYP3A, a dose-dependent decrease in AUC0–12h is seen after repeated tazemetostat administration, leading to AUC reduction of 42% at day 15 compared with day 0. Main pharmacokinetic parameters at steady state (15 days) are presented in Table 2. AUC at 15 days is 3340 ng.h/ml, Cmax is 829 ng/ml (coefficient of variation 56%), median maximal exposure (tmax) is reached approximately 1 h after administration, and mean half-life of the drug is between 3 and 4 h [51].

Table 2. . Major pharmacokinetic properties of EZH2 inhibitors.

| Parameters | Tazemetostat | EPZ-6930 |

|---|---|---|

| AUC0–12h, ng.h/ml† | 3340 (49.3) | 6840 (28) |

| Cmax, ng/ml† | 829 (56.3) | 1220 (30.8) |

| Tmax, h | 1.1 (1–4) | 2 (1–4.1) |

| T½, h† | 3.6 (24.1) | 4.27 (28.7) |

| Oral bioavailability | 33% | |

| Mean Vss/F (l)† | 1230 (46) | |

| Serum protein binding, % | 88% | |

| Mean CLss/F, l/h† | 274 l/h (49) | |

| Metabolized by | CYP3A | CYP3A |

| Excretion | Urine 15%, feces 79% |

Data reported as geometric mean (% coefficient of variation) except Tmax reported as median (IQR).

AUC: Area under the plasma concentration–time curve; CL: Plasma clearance; Cmax: Maximum plasma concentration; Cmin: Minimum plasma concentration; F: Bioavailability; IQR: Interquartile range; SS: Steady state; t1/2: Terminal elimination half-life; Tmax: Time to Cmax.

No interaction was seen with high dietary fat intake. However, tazemetostat decreases CYP3A and CYP2C8 substrate concentration, as demonstrated by a decrease in midazolam AUC from 0 to 12 h by 40%, and a similar decrease in that of repaglinide, respectively. On the other hand, tazemetostat concentration is increased by CYP3A inhibitors and coadministration should be avoided. If it cannot be avoided, tazemetostat doses should be reduced accordingly (400 mg twice daily for moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors) [53]. In a Phase Ib study [54] of tazemetostat in combination with R-CHOP, no interaction was seen with doxorubicin, vincristine, nor cyclophosphamide, except for a slight decrease in cyclophosphamide AUC.

Excretion of tazemetostat was found to be mainly in feces (74%) and 15% in urine. Its safety in liver-impaired patients is currently being evaluated (NCT04241835).

Clinical efficacy

NCT01897571: E7438-G000-101 Phase I

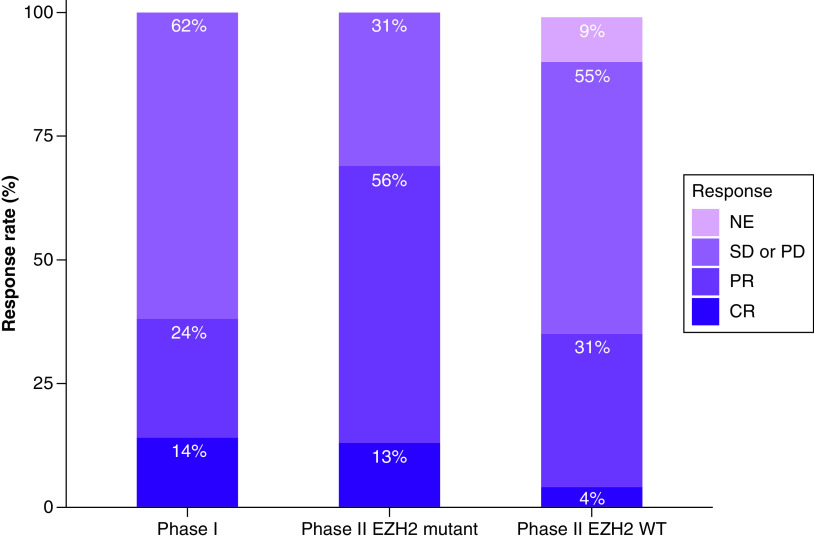

The first-in-human Phase I study (NCT01897571) [51] of tazemetostat was conducted in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and advanced solid tumors, including solid rhabdoid tumors, and sarcomas (Table 3). We report here only the results for lymphomas. Twenty-one patients were included in the study: 13 with DLBCL, seven with FL and one with marginal zone lymphoma (MZL). The study followed a classical 3 + 3 dose escalation followed by a dose expansion at the two highest doses. Overall response rate (ORR) was 38% (8/21) including five partial responses (PR) and three complete responses (CR). ORR (confirmed using PET-CT) by histology was 4/13 for DLBCL, 3/7 for FL, 1/1 for MZL and CRs were observed in two patients with FL and one with DLBCL (Figure 2). Median time to first response was 3.5 months. In responders, median duration of response was 12.4 months and increased to 27–33 months for complete responders. Of the two DLBCL patients harboring EZH2 mutations, one responded to treatment and the other progressed.

Table 3. . Results of clinical trials of tazemetostat in follicular lymphomas. Medians reported with interquartile ranges.

| Clinical trial | Phase | Trial design | Inclusion criteria | Patients (n) | Prior lines (n) | Dosing | ORR | CR | Median duration of response | Median PFS | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E7438-G000-101 NCT01897571 | I | Open-label, multicenter, 3 + 3 dose-escalation followed by expansion phase | R/R B-cell NHL† | 21 | 3 | 100–1600 mg BID | 8/21‡ (38%) | 3/21§ | 12.4 months | [51] | ||

| E7438-G000-101 NCT01897571 |

II | Open-label, multicenter | R/R FL including grade 3b and transformed | EZH2 mutant | 45 | 2 (1–11) | 800 mg BID |

69% (53.4–81.1) |

6/45 (13%) |

10.9 months (7.2–NE) |

13.8 months (10.7–22.0) |

[55] |

| EZH2 WT | 54 | 3 (1–8) | 35% (22.7–49.4) |

2/54 (4%) |

13 months (5/6–NE) |

11.1 months (3.7–14.6) |

||||||

Results in patients with progressive locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors omitted.

Including four patients with DLBCL, three with FL and one with MZL.

Including one patient with DLBCL and two with FL.

BID: Twice daily; CR: Complete response; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL: Follicular lymphoma; MZL: Marginal zone lymphoma; NE: Not evaluable; NHL: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; ORR: Objective response rate; PFS: Progression-free survival; R/R: Relapsed or refractory; WT: Wild-type.

Figure 2. . Response rates in Phase I (all non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and II (follicular lymphoma only) clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01897571).

CR: Complete response; NE: Not evaluable or unknown; PD: Progressive disease; PR: Partial response; SD: Stable disease; WT: Wild-type.

NCT01897571: E7438-G000-101 Phase II

The Phase II part of the trial [55] was conducted in six cohorts, one of which included 45 FL patients with EZH2 mutations and another one of which included 54 patients that were EZH2 WT. EZH2 mutations were identified prospectively using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples, which were centrally tested using the cobas® EZH2 Mutation Test. The cobas EZH2 Mutation test is designed to detect the following mutations: Y646X (S, H, C), Y646F, Y646N, A682G and A692V. Median duration of follow-up was 22 and 35.9 months, respectively. Objective response rate (ORR; including PR and CR) was 69% (53–82%) in EZH2-mutant and 35% (23–49%) in EZH2 WT, among which, respectively, 13 and 4% reached a CR as assessed by an independent radiology committee (Figure 2). Time to first response was 3.7 months, similar to that seen in Phase I. Responses lasted 10.9 months in patients with EZH2-mutant FL and 13 months in EZH2 WT, with estimated PFS of 13.8 and 11.1 months, respectively.

Response rates in high-risk subgroups were promising: patients who had progressed less than 24 months after their last therapy [56] had an ORR of 63% if EZH2-mutant and 25% otherwise. Similarly, double-refractory patients had ORRs of 78 and 27%, respectively. All three patients with grade 3b or transformed EZH2-mutant FL had a PR and two of six patients with either grade 3b or transformed EZH2-WT FL presented a response. Ancillary molecular analyses have shown EZH2 mutations to be predictors of treatment response in patients with FL, in contrast to results in patients with DLBCL [57].

However, efficacy results cannot be strictly compared between the two FL cohorts because EZH2-mutant patients had notably better prognostic factors, namely fewer grade 3b FLs or transformed lymphomas (three in EZH2-mutant and six in EZH2 WT), shorter median time from diagnosis (4.7 vs 6.3 years) and fewer prior lines of therapy (2 vs 3), double-refractory patients (20 vs 28%) and patients with progression of disease within 2 years (42 vs 59%), possibly reflecting known differences in disease biology and outcomes between these two populations [5,8,55].

A longer follow-up of this study would be desirable to further evaluate overall survival of these patients and the ability to deliver subsequent therapies if needed.

NCT02889523: Epi RCHOP

A third clinical trial [54] evaluating tazemetostat in lymphoma, although only in DLBCL, was a Phase Ib study in which tazemetostat was combined with R-CHOP for first-line treatment for patients aged 60–80 years. The CR rate was promising, 76.5%, warranting further trials. This combination presented additional safety issues, described in the next section.

Safety & tolerability

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) with tazemetostat reported in the published Phase I and II studies were nausea (20–23%), asthenia (18–55%), fatigue (17%), alopecia (<10–17%), dry skin (<10–13%), diarrhea (11–18%) and those were predominantly of grade 1 or 2 (Table 4). A variety of grade 3–5 events occurred during the Phase I study that included a majority of patients with advanced stage solid tumors; none of the seven fatal events observed during the Phase I study was considered as related to the study dug. During the Phase II study, treatment-related adverse events of grade ≥3 were infrequent and included neutropenia (3%), thrombocytopenia (3%), anemia (2%), myelodysplastic syndrome (1%), pancytopenia (1%), asthenia (1%), fatigue (1%), leucopenia (1%), hypophosphatemia (1%) and hypertriglyceridemia (1%). No fatal TEAE was seen in Phase II. In the clinical trial combining tazemetostat with R-CHOP therapy, a higher incidence of constipation was seen compared with other clinical trials, possibly due to the elderly population receiving vincristine included in the trial [54].

Table 4. . Summary of adverse events reported on treatment with tazemetostat as a single agent.

| Event | Phase I (n = 64); 21 patients with lymphoma, others with solid tumors | Phase II (n = 99); EZH2 WT and mutant FL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | |

| Any | 63 (99%) | 23 (36%) | 98 (99%) | 27 (27%, serious TEAEs) |

| Leading to drug interruption | 12 (19%) | 27 (27%) | ||

| Leading to treatment discontinuation | 5 (8%) | 8 (8%) | ||

| General | ||||

| – Asthenia | 35 (55%) | 1 (2%) | 18 (18%) | 3 (3%) |

| – Fatigue | 17 (17%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| – General deterioration of physical health | 5 (8%) | 4 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| – Vomiting | 12 (19%) | 0 | 12 (12%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Nausea | 13 (20%) | 0 | 23 (23%) | 0 |

| – Anorexia | 14 (22%) | 3 (5%) | ||

| – Abdominal pain | 11 (17%) | 1 (2%) | 13 (13%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Upper abdominal pain | 6 (6%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Diarrhea | 7 (11%) | 0 | 18 (18%) | 0 |

| – Constipation | 11 (17%) | 0 | ||

| – Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Respiratory, thoracic, mediastinal | ||||

| – Cough | 16 (16%) | 0 | ||

| – Upper respiratory tract infection | 15 (15%) | 0 | ||

| – Bronchitis | 15 (15%) | 0 | ||

| – Lung infection | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Pleural effusion | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Dyspnea | 10 (16%) | 1 (2%) | 8 (8%) | 3 (3%) |

| – Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 0 | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Respiratory distress | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| – Hypoxia | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Noncardiac chest pain | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Hematologic | ||||

| – Anemia | 14 (22%) | 3 (5%) | 14 (14%) | 5 (5%) |

| – Thrombocytopenia | 11 (17%) | 4 (6%) | 10 (10%) | 5 (5%) |

| – Neutropenia | 6 (9%) | 4 (6%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (4%) |

| – Lymphopenia | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Leucopenia | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Pancytopenia | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Acute myeloid leukaemia | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Nervous system | ||||

| – Osmotic demyelination syndrome | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Neuralgia | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Headache | 12 (12%) | 0 | ||

| – Anxiety, depression | 8 (13%) | 4 (6%) | ||

| – Dizziness | 7 (7%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Musculoskeletal | ||||

| – Back pain, pain management | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 11 (11%) | 0 |

| – Muscle spasms | 14 (22%) | 0 | ||

| Infection | ||||

| – Pyrexia | 5 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 10 (10%) | 0 |

| – Sepsis, septic shock | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| – Empyema | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Device or catheter-related infection | 3 (5%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| – Urinary tract infection | 6 (6%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Herpes zoster | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| – Hypertension | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Pulmonary embolism | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| – Venous occlusion | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Presyncope, syncope | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| – Constrictive pericarditis | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Hepatobiliary and metabolic | ||||

| – Cholestatic hepatitis | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Hepatocellular injury | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Jaundice cholestatic | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Increased serum aminotransferase | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Bile duct obstruction | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Ascites | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Acute pancreatitis | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Hyperlipasemia or hyperamylasemia | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Hypertriglyceridemia | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Hyperglycaemia | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Renal | ||||

| – Renal colic | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Renal failure acute | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| – Chronic kidney disease | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Hypophosphataemia | 5 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

| – Hyperkalemia | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Hypokalaemia | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Hyperuricaemia | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Dermatologic | ||||

| – Alopecia | 17 (17%) | 0 | ||

| – Dry skin | 8 (13%) | 0 | ||

| – Malignant melanoma | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| – Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

Data expressed as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Of note, in the Phase I study, including a majority of patients with solid tumors, seven patients died with a TEAE (four patients with general status deterioration, two from acute respiratory distress syndrome, one from a septic shock), none of which was considered by the investigators to be drug related.

FL: Follicular lymphoma; NHL: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; TEAE: Treatment-emergent adverse event; WT: Wild-type.

In the Phase II study, tazemetostat dose reductions occurred in nine (9%) of 99 patients and TEAE leading to dose interruptions occurred in 27 (27%) patients. Eight (8%) patients discontinued tazemetostat because of a TEAE (predominantly infectious, hematological or general), five of which were solely related to the study drug.

Prescribing information (detailed in [53]) recommends to withhold tazemetostat in case of occurrence of significant cytopenia or other grade 3 (or higher) AEs, the drug being reintroduced at a reduced dose after resolution of the AE to grade 1. The recommended dose reduction scheme consists in decreasing each intake by 200 mg steps (i.e., from 800 to 600 mg and then 400 mg, all twice daily), and to discontinue the drug if 400 mg twice a day is not tolerated.

Two myeloid malignancies (0.6%) occurred in the Phase II trial, one myelodysplastic syndrome and one acute myeloid leukemia, at 15.3 and 25.8 months after the onset of treatment, respectively. One patient developed a melanoma and one a squamous cell carcinoma. All these events except the myelodysplastic syndrome were judged unrelated to treatment by the investigators. It is known, however, that EZH2-inactivating mutations favor T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia in animal models [58] and were also found in human myeloid leukemia [13]. Furthermore, in young rats, tazemetostat administration for more than 9 weeks leads to the occurrence of T-lymphoblastic leukemia [59]. Moreover, one child with advanced poorly differentiated chordoma developed a secondary T-cell lymphoma in a tazemetostat Phase I pediatric trial, causing the FDA to place a partial clinical hold on development of the drug in 2018, which was lifted later in 2018 after the Agency determined that the drug’s risk/benefit balance was favorable [59]. The occurrence of secondary malignancies might be linked to higher and longer drug exposure, but a causal link remains questionable considering the number of courses of chemotherapy patients in these studies had received prior to tazemetostat. Most patients responding to tazemetostat have been included in a rollover trial whose results will provide important information regarding long-term safety and association with secondary malignancies.

Tazemetostat exposure during organogenesis to pregnant rats and rabbits has been reported to result in higher incidences of skeletal developmental abnormalities in fetuses, and it has been shown to modify the epigenome of rat oocytes long after treatment arrest [60]. Consequently, tazemetostat has the potential risk for teratogenicity; therefore, contraception is required during therapy and for 6 months after the last dose.

Resistance mechanisms

Currently, no specific study has addressed resistance mechanisms to tazemetostat in human FL. However, a study on DLBCL cell lines evidenced that IGF-1 R, PI3K and MEK pathway activation were sufficient to confer resistance to another EZH2 inhibitor GSK126 [61]. Treatment with PI3K inhibitor restores some activity of GSK126, indicating potential interesting association of those two drug classes. In cells that were GSK126 resistant, this study also identified the appearance of new EZH2 mutations (EZH2Y726F, EZHC663Y) altering the drug binding and conferring resistance to both GSK126 and tazemetostat. Inhibition by UNC1999, another EZH2 inhibitor, or by EED226, an allosteric PRC2 inhibitor, was not affected by some of these mutations. To our knowledge, there has not yet been report of such mutations in patients treated with tazemetostat.

Regulatory approval

In January 2020, tazemetostat was approved in the USA for treatment of adults and pediatric patients 16 years and older with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma that cannot be resected. The FDA subsequently approved tazemetostat in June 2020 for patients with relapsed or refractory EZH2-mutant FL (as detected by an FDA-approved test) after at least two prior lines of systemic therapy or for patients with relapsed or refractory FL who have no satisfactory alternative treatment options. The cobas® EZH2 Mutation Test has been approved at the same time by the FDA to identify the mutations targeted by the drug in FL tumor tissue specimens.

EMA granted orphan designation to tazemetostat in FL in 2018. However, no application for marketing authorization has yet been assessed by EMA.

Ongoing studies in lymphoma patients

Several studies are ongoing to characterize tazemetostat’s pharmacokinetics, drug–drug interactions (NCT03028103 and NCT04537715), and safety in patients with moderate to severe liver dysfunction (NCT04241835).

Single-agent Phase II studies are also currently active in non-Hodgkin lymphomas with EZH2 mutations in adults (NCT03456726), and pediatric patients with relapsed or refractory advanced solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphoma or histiocytic disorders (NCT03213665).

Because EZH2 plays a role in immune regulation, tazemetostat has been combined with anti-PD-L1 to amplify the immune response. Hence, a Phase I clinical trial of tazemetostat with obinutuzumab and atezolizumab was recently completed in patients with DLBCL, but was considered as futile based on early results (NCT02220842) [62].

In vitro studies of combination with R-CHOP components have identified an interesting synergistic effect of steroids with tazemetostat [63]. This combination is being evaluated in B-cell lymphomas and solid tumors (NCT01897571). The Phase II study of the R-CHOP combination (NCT02889523) as first-line treatment for DLBCL described above is recruiting, with the recent addition of a cohort of patients with FL.

Given the recent approval of the combination of rituximab and lenalidomide in patients with FL, a randomized Phase III clinical trial evaluating tazemetostat with this combination has recently been initiated (NCT04224493). Lastly, another clinical trial (NCT04590820) will soon open to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding tazemetostat to rituximab in patients with FL in the second or subsequent line of treatment.

Conclusion

Major therapeutic advances for patients with FL have been achieved recently with the development of noncytotoxic agents or combinations, in particular immunotherapeutic approaches. Several new compounds of this class will continue to emerge, leading to new active therapeutic options for selected patients. Despite the key role of epigenetic alterations in FL and the numbers of mutated genes in this pathway, interventions directed toward the epigenetic machinery have so far been rather disappointing, with the exception of EZH2-targeted agents such as the first-in-class tazemetostat. This EZH2 inhibitor is effective in FL, especially cases harboring EZH2 mutations, and represents the first approved therapy selectively targeting a gene found to be mutated in this disease. Early toxicity related to treatment seems limited. However, long-term safety must be assessed prior to consideration as an earlier therapeutic option.

The current approval of tazemetostat specifies the use of a companion diagnostic test detecting EZH2 mutations on tumor tissue but does not take into account molecular and clonal heterogeneity of FL, which might be better approached using sensitive circulating tumor DNA testing, for instance. Furthermore, the clinical activity of the compound in patients without presence of the EZH2 mutation in their tumors suggests a broader potential of activity of this drug (i.e., in the immune environment) or the existence of off-target effects. Preclinical models have shown synergistic activity of tazemetostat and steroids [63], tazemetostat and the Bcl2 inhibitor venetoclax [64] and tazemetostat and PI3K inhibitors [61], indicating interesting therapeutic associations to investigate. Given recent results revealing close links between epigenetic mutations and modifications of the microenvironment in this lymphoma, the combination of epigenetically targeted drugs such as tazemetostat with immunotherapies may also contribute to significant therapeutic progresses.

Results of ongoing and future clinical trials investigating tazemetostat in combination with other therapies or in selected well-defined FL populations at higher risk of progression will determine this drug’s position in the rapidly evolving therapeutic landscape for this disease.

Executive summary.

Background

New therapeutic options are needed for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) whose cancer relapses after or is refractory to classical treatment options.

EZH2 is a key component of the epigenetic machinery controlling normal and transformed B-cell biology in the germinal center. Activating mutations of EZH2 (25% of cases) or other mechanisms leading to EZH2 overexpression are found in FL, leading to increased H3K27 trimethylation, which promotes cell proliferation while blocking differentiation. Thus, EZH2 represents a potential therapeutic target in patients with FL.

Mechanisms of action

Tazemetostat is an efficient and selective EZH2 inhibitor, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of lymphoma cells in preclinical models.

Clinical efficacy

In the Phase II trial, tazemetostat as a single agent induced high objective response rates in patients with relapsed or refractory FLs: 69% in EZH2-mutant patients (56% partial and 13% complete responses) and 35% in EZH2 wild-type patients (31% partial and 4% complete responses). Responses and progression-free survival lasted nearly 1 year and were comparable between these two cohorts.

Safety

Administration of tazemetostat is well tolerated, causing mostly gastrointestinal and hematologic adverse events, and grade 3 events in less than 5% of patients.

Long-term safety has yet to be evaluated for this epigenetic modulating agent, especially regarding secondary malignancies.

Conclusion

Tazemetostat is the first-in-class inhibitor of EZH2 with promising clinical activity and a good safety profile and has recently been approved by the US FDA for patients with FL after two lines of therapy when EZH2 is mutated (as assessed using an FDA-approved test) or when no other therapeutic option is available. Long-term data and further studies are needed to complete the evaluation of its clinical benefit and position this new agent in the evolving therapeutic landscape of FL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Moore for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions

E Julia and G Salles reviewed research articles and wrote the manuscript.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

G Salles has received financial compensations for participating on advisory boards and consulting regarding educational events from Abbvie, Allogene, Beigene, Autolus, BMS/Celgene, Debiopharm, Genmab, Kite/Gilead, Epizyme, Janssen, Incyte, Karyopharm, Morphosys, Novartis, Roche/Genentech and Velosbio. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Company review disclosure

In addition to the peer-review process, with the authors’ consent, the manufacturer of the product discussed in this article was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for factual accuracy. Changes were made by the authors at their discretion and based on scientific or editorial merit only. The authors maintained full control over the manuscript, including content, wording and conclusions.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest

- 1.Summers KE, Goff LK, Wilson AG, Gupta RK, Lister TA, Fitzgibbon J. Frequency of the Bcl-2/IgH rearrangement in normal individuals: implications for the monitoring of disease in patients with follicular lymphoma. JCO 19(2), 420–424 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sermer D, Pasqualucci L, Wendel H-G, Melnick A, Younes A. Emerging epigenetic-modulating therapies in lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16(8), 494–507 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korfi K, Ali S, Heward JA, Fitzgibbon J. Follicular lymphoma, a B cell malignancy addicted to epigenetic mutations. Epigenetics 12(5), 370–377 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature 476(7360), 298–303 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastore A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol. 16(9), 1111–1122 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okosun J, Bödör C, Wang J et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies recurrent mutations and evolution patterns driving the initiation and progression of follicular lymphoma. Nat. Genet. 46(2), 176–181 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bödör C, Grossmann V, Popov N et al. EZH2 mutations are frequent and represent an early event in follicular lymphoma. Blood 122(18), 3165–3168 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huet S, Xerri L, Tesson B et al. EZH2 alterations in follicular lymphoma: biological and clinical correlations. Blood Cancer J. 7(4), e555 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lockmer S, Ren W, Brodtkorb M et al. M7-FLIPI is not prognostic in follicular lymphoma patients with first-line rituximab chemo-free therapy. Br. J. Haematol. 188(2), 259–267 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huet S, Sujobert P, Salles G. From genetics to the clinic: a translational perspective on follicular lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18(4), 224–239 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasqualucci L, Khiabanian H, Fangazio M et al. Genetics of follicular lymphoma transformation. Cell Rep. 6(1), 130–140 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassetta L, Pollard JW. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17(12), 887–904 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J et al. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat. Genet. 42(8), 722–726 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Béguelin W, Popovic R, Teater M et al. EZH2 is required for germinal center formation and somatic EZH2 mutations promote lymphoid transformation. Cancer Cell 23(5), 677–692 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Seminal description of the role of EZH2 in germinal center formation and lymphoid transformation.

- 15.Su I-H, Basavaraj A, Krutchinsky AN et al. Ezh2 controls B cell development through histone H3 methylation and Igh rearrangement. Nat. Immunol. 4(2), 124–131 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caganova M, Carrisi C, Varano G et al. Germinal center dysregulation by histone methyltransferase EZH2 promotes lymphomagenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 123(12), 5009–5022 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat. Genet. 42(2), 181–185 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • First description of EZH2 activating mutations in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.

- 18.Bödör C, O’Riain C, Wrench D et al. EZH2 Y641 mutations in follicular lymphoma. Leukemia 25(4), 726–729 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCabe MT, Graves AP, Ganji G et al. Mutation of A677 in histone methyltransferase EZH2 in human B-cell lymphoma promotes hypertrimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109(8), 2989–2994 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yap DB, Chu J, Berg T et al. Somatic mutations at EZH2 Y641 act dominantly through a mechanism of selectively altered PRC2 catalytic activity, to increase H3K27 trimethylation. Blood 117(8), 2451–2459 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Molecular consequences of the activating EZH2 in lymphoid cells; first demonstration of an activating mutation increasing histone methylation.

- 21.Sneeringer CJ, Scott MP, Kuntz KW et al. Coordinated activities of wild-type plus mutant EZH2 drive tumor-associated hypertrimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27) in human B-cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107(49), 20980–20985 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souroullas GP, Jeck WR, Parker JS et al. An oncogenic EZH2 mutation induces tumors through global redistribution of histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation. Nat. Med. 22(6), 632–640 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • EZH2 mutations induce global redistribution of H3K27 marks all over the genome.

- 23.Ryan RJH, Nitta M, Borger D et al. EZH2 codon 641 mutations are common in BCL2-rearranged germinal center B cell lymphomas. PLoS ONE 6(12), e28585 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Béguelin W, Teater M, Gearhart MD et al. EZH2 and BCL6 cooperate to assemble CBX8–BCOR complex to repress bivalent promoters, mediate germinal center formation and lymphomagenesis. Cancer Cell 30(2), 197–213 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ennishi D, Takata K, Béguelin W et al. Molecular and genetic characterization of MHC deficiency identifies EZH2 as therapeutic target for enhancing immune recognition. Cancer Discov. 9(4), 546–563 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldinucci D, Gloghini A, Pinto A, De Filippi R, Carbone A. The classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma microenvironment and its role in promoting tumour growth and immune escape. J. Pathol. 221(3), 248–263 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Béguelin W, Teater M, Meydan C et al. Mutant EZH2 induces a pre-malignant lymphoma niche by reprogramming the immune response. Cancer Cell 37(5), 655–673.e11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumes DJ, Onodera A, Suzuki A et al. The polycomb protein Ezh2 regulates differentiation and plasticity of CD4(+) T helper Type 1 and Type 2 cells. Immunity 39(5), 819–832 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Zeng Z, Xing S et al. Ezh2 programs TFH differentiation by integrating phosphorylation-dependent activation of Bcl6 and polycomb-dependent repression of p19Arf. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 5452 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuPage M, Chopra G, Quiros J et al. The chromatin-modifying enzyme EZH2 is critical for the maintenance of regulatory T cell identity after activation. Immunity 42(2), 227–238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature 492(7427), 108–112 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM et al. A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8(11), 890–896 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi W, Chan H, Teng L et al. Selective inhibition of EZH2 by a small molecule inhibitor blocks tumor cells proliferation. PNAS 109(52), 21360–21365 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sehn LH, Goy A, Offner FC et al. Randomized Phase II trial comparing obinutuzumab (GA101) with rituximab in patients with relapsed CD20+ indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final analysis of the GAUSS Study. JCO 33(30), 3467–3474 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohatiner AZS, Nadler L, Davies AJ et al. Myeloablative therapy with autologous bone marrow transplantation for follicular lymphoma at the time of second or subsequent remission: long-term follow-up. JCO 25(18), 2554–2559 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casulo C, Barr PM. How I treat early-relapsing follicular lymphoma. Blood 133(14), 1540–1547 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonard JP, Trneny M, Izutsu K et al. AUGMENT: a Phase III study of lenalidomide plus rituximab versus placebo plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory indolent lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 37(14), 1188–1199 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morschhauser F, Gouill SL, Feugier P et al. Obinutuzumab combined with lenalidomide for relapsed or refractory follicular B-cell lymphoma (GALEN): a multicentre, single-arm, Phase II study. Lancet Haematol. 6(8), e429–e437 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gopal AK, Kahl BS, de Vos S et al. PI3Kδ inhibition by idelalisib in patients with relapsed indolent lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 370(11), 1008–1018 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salles G, Schuster SJ, de Vos S et al. Efficacy and safety of idelalisib in patients with relapsed, rituximab- and alkylating agent-refractory follicular lymphoma: a subgroup analysis of a Phase II study. Haematologica 102(4), e156–e159 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dreyling M, Santoro A, Mollica L et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibition by copanlisib in relapsed or refractory indolent lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 35(35), 3898–3905 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flinn IW, O’Brien S, Kahl B et al. Duvelisib, a novel oral dual inhibitor of PI3K-δ,γ, is clinically active in advanced hematologic malignancies. Blood 131(8), 877–887 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morschhauser F, Flinn IW, Advani R et al. Polatuzumab vedotin or pinatuzumab vedotin plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final results from a Phase II randomised study (ROMULUS). Lancet Haematol. 6(5), e254–e265 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Advani R, Flinn I, Popplewell L et al. CD47 blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and rituximab in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 379(18), 1711–1721 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zinzani PL, Flinn IW, Yuen SLS et al. Venetoclax-rituximab ± bendamustine vs bendamustine-rituximab in relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: CONTRALTO. Blood 136(23), 2628–2637 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 377(26), 2545–2554 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forero-Torres A, Ramchandren R, Yacoub A et al. Parsaclisib, a potent and highly selective PI3Kδ inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies. Blood 133(16), 1742–1752 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knutson SK, Kawano S, Minoshima Y et al. Selective inhibition of EZH2 by EPZ-6438 leads to potent antitumor activity in EZH2-mutant non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13(4), 842–854 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Wigle TJ et al. Durable tumor regression in genetically altered malignant rhabdoid tumors by inhibition of methyltransferase EZH2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110(19), 7922–7927 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • First report proving tazemetostat antitumoral efficacy in preclinical models of B-cell lymphomas.

- 50.Brach D, Johnston-Blackwell D, Drew A et al. EZH2 inhibition by tazemetostat results in altered dependency on B-cell activation signaling in DLBCL. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16(11), 2586–2597 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Italiano A, Soria J-C, Toulmonde M et al. Tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, Phase I study. Lancet Oncol. 19(5), 649–659 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • First-in-human Phase I clinical trials of tazemetostat in solid tumors and non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas.

- 52.Otsuka Y, Nishikori M, Arima H et al. EZH2 inhibitors restore epigenetically silenced CD58 expression in B-cell lymphomas. Mol. Immunol. 119, 35–45 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.FDA. Tazemetostat - FDA drug prescribing informations. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/211723s000lbl.pdf

- 54.Sarkozy C, Morschhauser F, Dubois S et al. A LYSA Phase Ib Study of tazemetostat (EPZ-6438) plus R-CHOP in newly diagnosed diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients with poor prognosis features. Clin. Cancer Res. 26(13), 3145–3153 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morschhauser F, Tilly H, Chaidos A et al. Tazemetostat for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, Phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 21(11), 1433–1442 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Phase II trial shows tazemetostat safety and promising clinical activity in follicular lymphoma; this study supported the FDA approval of the drug.

- 56.Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL et al. Early relapse of follicular lymphoma after rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone defines patients at high risk for death: an analysis from the National Lympho Care Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 33(23), 2516–2522 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonald A, Thomas E, Daigle S et al. Updated report on identification of molecular predictors of tazemetostat response in an ongoing NHL Phase II study. Blood 132(Suppl. 1), 4097–4097 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang C, Oshima M, Sato D et al. Ezh2 loss propagates hypermethylation at T cell differentiation-regulating genes to promote leukemic transformation. J. Clin. Invest. 128(9), 3872–3886 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.FDA. FDA Briefing Document Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting: NDA 211723 tazemetostat applicant epizyme. (2019). https://www.fda.gov/media/133573/download

- 60.Prokopuk L, Hogg K, Western PS. Pharmacological inhibition of EZH2 disrupts the female germline epigenome. Clin. Epigenet. 10, 33 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bisserier M, Wajapeyee N. Mechanisms of resistance to EZH2 inhibitors in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood 131(19), 2125–2137 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palomba ML, Till BG, Park SI et al. A Phase Ib study evaluating the safety and clinical activity of atezolizumab combined with obinutuzumab in patients with relapsed or refractory non-hodgkin lymphoma (nhl). Hematol. Oncol. 35(S2), 137–138 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Johnston LD et al. Synergistic anti-tumor activity of EZH2 inhibitors and glucocorticoid receptor agonists in models of germinal center non-Hodgkin lymphomas. PLoS ONE 9(12), e111840 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scholze H, Stephenson RE, Reynolds R et al. Combined EZH2 and Bcl-2 inhibitors as precision therapy for genetically defined DLBCL subtypes. Blood Adv. 4(20), 5226–5231 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leonard JP, Jung S-H, Johnson J et al. Randomized trial of lenalidomide alone versus lenalidomide plus rituximab in patients with recurrent follicular lymphoma: CALGB 50401 (Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 33(31), 3635–3640 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, Phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 17(8), 1081–1093 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheson BD, Chua N, Mayer J et al. Overall survival benefit in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-hodgkin lymphoma who received obinutuzumab plus bendamustine induction and obinutuzumab maintenance in the GADOLIN study. JCO 36(22), 2259–2266 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]