Abstract

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 is a highly contagious virus, and despite professionals' best efforts, nosocomial COVID-19 (NC) infections have been reported. This work aimed to describe differences in symptoms and outcomes between patients with NC and community-acquired COVID-19 (CAC) and to identify risk factors for severe outcomes among NC patients.

Methods

This is a nationwide, retrospective, multicenter, observational study that analyzed patients hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 in 150 Spanish hospitals (SEMI-COVID-19 Registry) from March 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. NC was defined as patients admitted for non-COVID-19 diseases with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test on the fifth day of hospitalization or later. The primary outcome was 30-day in-hospital mortality (IHM). The secondary outcome was other COVID-19-related complications. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed.

Results

Of the 23,219 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 1,104 (4.8%) were NC. Compared to CAC patients, NC patients were older (median 76 vs. 69 years; p < 0.001), had more comorbidities (median Charlson Comorbidity Index 5 vs. 3; p < 0.001), were less symptomatic (p < 0.001), and had normal chest X-rays more frequently (30.8% vs. 12.5%, p < 0.001). After adjusting for sex, age, dependence, COVID-19 wave, and comorbidities, NC was associated with lower risk of moderate/severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.59–0.87; p < 0.001) and higher risk of acute heart failure (aOR: 1.40; 1.12–1.72; p = 0.003), sepsis (aOR: 1.73; 1.33–2.54; p < 0.001), and readmission (aOR: 1.35; 1.03–1.83; p = 0.028). NC was associated with a higher case fatality rate (39.1% vs. 19.2%) in all age groups. IHM was significantly higher among NC patients (aOR: 2.07; 1.81–2.68; p < 0.001). Risk factors for increased IHM in NC patients were age, moderate/severe dependence, malignancy, dyspnea, moderate/severe ARDS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and shock; odynophagia was associated with lower IHM.

Conclusions

NC is associated with greater mortality and complications compared to CAC. Hospital strategies to prevent NC must be strengthened.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infection, Cross-infection, Hospital mortality, Elderly, Aged

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has encompassed over 520 million reported COVID-19 infections and well over 6.2 million deaths worldwide as of May 15, 2022 [1]. The pandemic has posed an enormous challenge to health systems worldwide, many of which have dealt with significant overload. COVID-19 has a high mortality rate in patients who require hospitalization and especially among older patients [2, 3, 4, 5].

The hallmark of SARS-CoV-2 is its highly contagious nature. Its main mode of transmission is through droplets and close contact with infected individuals [6]. The incubation period is estimated to be 5–7 days but can last as long as 14 days [7]. Despite robust measures to control infection, hospital-acquired (or nosocomial) COVID-19 (NC) infections have been reported [8, 9, 10]. Several studies have described NC outbreaks in diverse settings [8, 10, 11] as well as the different measures implemented to control outbreaks [12, 13]. Nevertheless, few studies have compared patients with NC versus community-acquired COVID-19 (CAC) infection [14]. To date, many uncertainties remain regarding NC-related morbidity and mortality.

This study aimed to determine differences between NC and CAC infection in regard to epidemiological and clinical variables, in-hospital management, and outcomes. Its secondary aim was to analyze risk factors at admission associated with in-hospital mortality (IHM) among NC patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted an observational, multicenter, nationwide study of patients hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 in Spain from March 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. Patients were analyzed according to the wave of the pandemic during which they were admitted during the study period: the first wave or the second wave. The first wave included patients admitted from March 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020, and second wave included patients admitted from July 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. We cannot rule out the possibility that changes in SARS-CoV-2 variants during the pandemic may have influenced our results. During the first wave and the beginning of the second wave, the original SARS-CoV-2 variant from Wuhan, China, was prevalent and showed a relatively low transmissibility but high severity. In early 2021, the alpha variant from the UK was more prevalent and had greater infectivity and transmissibility.

All patient data were obtained from the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine's SEMI-COVID-19 Registry, in which 150 Spanish hospitals participated. The SEMI-COVID-19 Registry prospectively compiles data on the index admission of patients ≥18 years of age with COVID-19 confirmed microbiologically through a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction or antigen test. More in-depth information about the justification, objectives, methodology, and preliminary results of the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry has recently been published [3, 5].

Definition of Variables

Two subgroups were defined: (a) NC: patients admitted for non-COVID-19 diseases who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test on the fifth day of hospitalization or later; (b) CAC: community-dwelling and nursing home patients admitted for COVID-19 that was confirmed microbiologically before the fifth day of hospitalization. To assess preadmission functional status, we used the Barthel Index (independent or mild dependence: 100–91; moderate dependence: 90–61; and severe dependence: ≤60) [15]. Comorbidities were evaluated by means of the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [16]. Patients were classified as having dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension if they had a previous diagnosis on their medical chart or received pharmacological treatment for these conditions. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease was defined as a medical history of coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, angina, or coronary revascularization), cerebrovascular disease (stroke, transient ischemic attack), or peripheral arterial disease (intermittent claudication, revascularization, lower limb amputation, or abdominal aortic aneurysm). Chronic pulmonary disease was defined as diagnosis of asthma and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Malignancy encompassed hematologic neoplasia and/or solid tumors (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer). All baseline comorbidities were gathered from patients' electronic medical records (EMR) obtained from the hospitals. Patients' symptoms (dyspnea, fever [temperature ≥37.8°C], cough, fatigue, anorexia, arthralgia-myalgia, diarrhea, headache, nausea/vomiting, odynophagia, abdominal pain, ageusia, anosmia) and physical examination findings (oxygen saturation; temperature; blood pressure; heart rate; confusion; rales, rhonchi, or wheezing on the pulmonary auscultation) were obtained from the EMR. In CAC patients, analytical tests (blood gases, coagulation, metabolic panel, complete blood count) and diagnostic imaging tests were performed at admission, whereas in NC patients, these tests were performed immediately after SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis.

Complications during the hospitalization were defined pre hoc and were collected from the EMR. They included bacterial pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute heart failure, arrhythmia, acute coronary syndrome, myocarditis, epileptic seizures, stroke, shock, sepsis, acute kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, venous thromboembolism, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, shock, and acute limb ischemia. Ventilatory support included invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy [17].

The endpoint of the study was 30-day all-cause IHM expressed as the case fatality rate (CFR) or the proportion of in-hospital deaths in relation to the total number of hospitalized NC or CAC patients. More in-depth information about the definition of other variables is available in manuscripts recently published by the SEMI-COVID-19 Network [3, 5].

Statistical Analysis

First, differences in clinical and epidemiological variables according to NC and CAC infection were explored. Second, differences between non-survivors and survivors with NC were examined. The characteristics of each group were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous and categorical variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and as absolute values and percentages, respectively. The differences between groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Pearson's χ2 test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The differences between the two groups (NC and CAC) in regard to complications and outcomes were adjusted by sex, age, dependence, COVID-19 wave, and comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, non-atherosclerotic heart diseases, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, dementia, diabetes mellitus, chronic pulmonary disease, malignancy, and chronic kidney disease) using a multivariable regression analysis. These values were expressed as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To analyze IHM in NC patients, statistically significant variables identified on the univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were entered into a multivariable logistic regression using a forward stepwise selection method with the likelihood-ratio test. The model's validity was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test for estimating goodness of fit to the data, and its discriminatory ability was evaluated using area under the curve. As some variables were missing, those which were not available for >25% of patients were excluded from the analysis. These included pH, PO2, PaO2/FiO2, lactate dehydrogenase, serum ferritin, D-dimer, interleukin-6, procalcitonin, venous lactate, and aspartate aminotransferase. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical Aspects

All patients gave informed consent. All patients gave their informed consent, oral or written, for inclusion. In the periods of maximum hospital care pressure (March to April 2020, November 2020 to January 2021), it was almost impossible for patients to give written consent. At this time, they gave verbal consent reflected in the EMR by the physician approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Málaga on March 27, 2020 (Ethics Committee code: SEMI-COVID-19 27-03-20), as per the guidelines of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Products. In this work, all data collected, processed, and analyzed were anonymized and used only for the purposes of this project. All data were protected in accordance with the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of April 27, 2016, on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committees of each participating hospital. The STROBE statement guidelines were adhered to in the execution and reporting of the study.

Results

A total of 23,219 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were included in the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry from March 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. Of them, 17,089 (73.6%) were admitted in the first wave and 6,130 (26.4%) in the second wave. There were 1,104 (4.8%) NC patients and 22,115 (95.2%) CAC patients: 1,937 (8.3%) were nursing home residents and 19,919 (85.8%) were community-dwelling. The median (IQR) number of days from admission to hospital acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection was 10 (5–19).

Clinical, Analytical, and Radiological Findings in NC and CAC Patients

The median (IQR) length of hospitalization was 14 days (8–25) for NC patients and 9 days (5–14) for CAC patients. However, the median (IQR) number of days from diagnosis to discharge was similar in both groups: 10 days (5–17) versus 10 days (6–15), respectively.

Compared to NC patients, CAC patients were older (median age: 76 vs. 69 years; p < 0.001); had more moderate-severe dependence (30.3% vs. 16.9%; p < 0.001) and more comorbidities (median CCI 5 vs. 3; p < 0.001), including cardiovascular diseases, chronic pulmonary diseases, chronic kidney disease, malignancy, and dementia (p < 0.001 for all) (Table 1). Furthermore, NC patients did not have as many COVID-19-related symptoms as CAC patients, including fever and respiratory, flu-like, or gastrointestinal symptoms. In contrast, NC patients had higher rates of hypotension, confusion, and pulmonary rales. Also, the PO2/FiO2 ratio was lower among NC patients (p < 0.001 for all) (Table 1). NC patients more often had normal chest X-rays at diagnosis (30.8% vs. 12.5%, p < 0.001). Most of the inflammatory markers (leukocytes, neutrophils, procalcitonin, and interleukin-6, with the exceptions of lactate dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein) and D-dimer levels were higher at diagnosis in NC compared to CAC patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical, radiological, and analytic findings at diagnosis or admission in patients with NC versus CAC

| Missing values | Nosocomial (N = 1,104) | Community acquired (N = 22,115) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave (first/second) | 0 | 831 (75.3%)/273 (24.7%) | 16,258 (73.5%)/5,857 (26.3%) | 0.198 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 0 | 76 (64–84) | 69 (56–80) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 34 | 652 (59.1) | 12,710 (57.5) | 0.294 |

| Degree of dependence | 261 | |||

| Independent or mild | 752 (69.9) | 18,240 (83.1) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate | 199 (18.5) | 2,192 (9.6) | <0.001 | |

| Severe | 127 (11.8) | 1,605 (7.3) | <0.001 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| CCI, median (IQR) | 434 | 5 (3–7) | 3 (2–5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 62 | 703 (63.8) | 11,433 (51.7) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 71 | 515 (46.7) | 8,699 (39.3) | <0.001 |

| Non-atherosclerotic heart diseasesa | 118 | 337 (30.6) | 3,606 (16.3) | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseasesb | 88 | 327 (29.7) | 3,131 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 83 | 321 (29.1) | 4.514 (20.4) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 1,892 | 229 (22.5) | 4,583 (22.5) | 0.997 |

| Chronic pulmonary diseasec | 90 | 218 (19.8) | 3,450 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Malignancyd | 110 | 267 (24.2) | 2,054 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 73 | 153 (13.9) | 2,143 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney diseasee | 72 | 149 (13.5) | 1,279 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Cough | 86 | 585 (53.1) | 15,705 (71.2) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 98 | 553 (50.3) | 13,101 (59.4) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue | 240 | 362 (33.3) | 9,623 (43.9) | <0.001 |

| Arthralgia-myalgia | 200 | 157 (14.4) | 6,544 (29.8) | <0.001 |

| Anorexia | 302 | 333 (20.6) | 4,188 (19.1) | 0.246 |

| Diarrhea | 163 | 154 (15.0) | 5,301 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 255 | 76 (7.0) | 2,744 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Ageusia | 437 | 55 (5.1) | 2,068 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Anosmia | 400 | 46 (4.3) | 1,846 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 198 | 90 (8.3) | 2,613 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 219 | 70 (6.4) | 1,394 (6.4) | 0.947 |

| Fever >37.8°C | 106 | 515 (47.0) | 13,375 (60.6) | <0.001 |

| Odynophagia | 282 | 71 (6.5) | 2,022 (9.2) | 0.003 |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Sat O2 < 94% | 592 | 421 (30.4) | 9,102 (42.2) | 0.072 |

| Temperature >37.8°C | 1,160 | 245 (23.6) | 3,367 (21.2) | 0.067 |

| Hypotensionf | 741 | 106 (9.9) | 1,250 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Tachycardiaf | 597 | 250 (23.5) | 5,444 (25.3) | 0.185 |

| Tachypneaf | 429 | 343 (31.8) | 7,043 (32.4) | 0.681 |

| Confusion | 192 | 206 (18.7) | 2,485 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary rales | 537 | 479 (45.2) | 11,922 (55.0) | <0.001 |

| Chest X-ray findings | ||||

| Normal | 274 | 328 (30.8) | 2,750 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Unilateral infiltrates | 274 | 217 (20.7) | 4,126 (18.8) | |

| Bilateral infiltrates | 274 | 521 (48.9) | 15,038 (68.6) | |

| Complete blood count | ||||

| Leukocytes, ×103/µL | 237 | 6.9 (4.9–10.0) | 6.4 (4.8–8.7) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils, ×103/µL | 255 | 4.9 (3.1–8.1) | 4.7 (3.2–6.8) | 0.002 |

| Lymphocytes, ×103/µL | 192 | 0.92 (0.60–1.35) | 0.93 (0.68–1.30) | 0.471 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 139 | 12 (10.4–14.7) | 13.8 (12.6–15.0) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count, ×103/µL | 148 | 195 (146–272) | 191 (149–250) | 0.108 |

| Arterial blood gases | ||||

| PO2, mm Hg | 11,237 | 64 (54–77) | 66 (57–77.8) | 0.029 |

| PO2/FiO2 ratio | 11,237 | 273 (205–321) | 290 (238–342) | <0.001 |

| Serum biochemistry | ||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 823 | 112 (95–142) | 114 (100–140) | 0.002 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 202 | 67 (38–89) | 79 (55–94) | <0.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 2,781 | 292 (221–408) | 322 (249–435) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 732 | 56 (19–129) | 65 (22–131) | 0.040 |

| Venous lactate, mmol/L | 13,923 | 1.6 (1.2–2.6) | 1.5 (1.1–2.3) | 0.037 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 11,709 | 0.14 (0.07–0.40) | 0.10 (0.05–0.22) | <0.001 |

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 19,249 | 30 (12–66) | 24 (9–57) | 0.015 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 4,124 | 1,000 (525–2,036) | 660 (370–1,234) | <0.001 |

| Serum ferritin, µg/L | 12,131 | 537 (265–1,217) | 592 (281–1,197) | 0.421 |

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold. N (%), number of cases (percentage); IQR, interquartile range; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Non-atherosclerotic heart disease includes atrial fibrillation and/or heart failure.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease includes coronary, cerebrovascular, and/or peripheral vascular disease.

Chronic pulmonary disease includes chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and/or asthma.

Malignancy includes solid tumors or hematologic neoplasia.

Chronic kidney disease is defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 according to the CKD-EPI equation.

Tachypnea (≥20 breaths per minute), tachycardia (≥100 breaths per minute), and hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg).

Regarding targeted COVID-19 therapies, patients with NC received hydroxychloroquine, macrolides, and immunomodulatory drugs less often but anticoagulant therapies more often (Table 2). During hospitalization, NC patients more often had moderate/severe ARDS (29.9% vs. 24.5%), acute kidney failure (21.0% vs. 13.3%), bacterial pneumonia (13.2% vs. 9.9%), sepsis (10.9% vs. 5.9%), multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (10.9% vs. 5.4%), acute heart failure (13.6% vs. 5.8%), and stroke (3.1% vs. 0.7%) (p < 0.001 for all). The use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy and noninvasive mechanical ventilation was similar in both NC and CAC patients, but invasive mechanic ventilation and consequent intensive care unit admission were less common among NC patients (4.6% and 7.4% vs. 6.6% and 9.6%; p < 0.001 and p = 0.002). Finally, IHM was significantly higher in NC patients compared to CAC patients (32.1% vs. 19.4%; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment, complications, and outcome in patients with NC versus CAC

| Missing value | Nosocomial (N = 1,104) | Community acquired (N = 22,115) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomodulatory therapy | ||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 96 | 633 (57.5) | 14,002 (63.5) | <0.001 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 153 | 495 (45.1) | 10,702 (48.9) | 0.021 |

| Tocilizumab | 140 | 61 (5.5) | 2,212 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Colchicine | 359 | 14 (1.3) | 167 (0.8) | 0.060 |

| Anakinra | 159 | 7 (0.6) | 136 (0.6) | 0.936 |

| Baricitinib | 3,214 | 0 (0) | 157 (0.8) | 0.006 |

| Antiviral therapy | ||||

| Remdesivir | 207 | 60 (5.59 | 1,094 (5.0) | 0.432 |

| Immunoglobulins | 353 | 7(0.6) | 118 (0.5) | 0.664 |

| Antibiotic therapy | ||||

| Beta-lactams | 131 | 752 (68.4) | 15,185 (69.4) | 0.495 |

| Macrolides | 147 | 444 (40.5) | 11,906 (54.1) | <0.001 |

| Quinolones | 200 | 169 (15.5) | 3,085 (14.1) | 0.196 |

| Anticoagulant therapy | ||||

| Oral anticoagulants | 167 | 93 (8.5) | 831 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 167 | |||

| No | 200 (18.2) | 3,229 (14.7) | <0.001 | |

| Low doses | 637 (58.1) | 14,174 (64.4) | ||

| Intermediate doses | 85 (7.8) | 2,030 (9.2) | ||

| High doses | 174 (15.9) | 2,562 (11.6) | ||

| Ventilatory therapy | ||||

| High-flow nasal cannula oxygen | 194 | 101 (9.2) | 2,130 (9.7) | 0.612 |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 136 | 62 (5.7) | 1,278 (5.8) | 0.846 |

| Invasive mechanic ventilation | 127 | 50 (4.6) | 1,629 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Readmission | 286 | 69 (6.4) | 848 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 46 | 73 (6.6) | 2,130 (9.6) | 0.001 |

| IHM | 35 | 432 (39.1) | 4,245 (19.2) | <0.001 |

| Days of admission, median (IQR) | 14 (8–25) | 9 (5–14) | <0.001 | |

| Days from diagnosis to discharge, median (IQR) | 10 (5–17) | 10 (6–15) | 0.260 | |

| Complications | ||||

| ARDS, moderate/severe | 126 | 328 (29.9) | 5,406 (24.5) | <0.001 |

| Acute kidney failure | 93 | 231 (21.0) | 2,944 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 99 | 145 (13.2) | 2,187 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Acute heart failure | 84 | 150 (13.6) | 1,287 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 96 | 120 (10.9) | 1,299 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome | 101 | 110 (10.9) | 1,182 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 94 | 72 (6.6) | 961 (4.4) | 0.001 |

| Shock | 110 | 60 (5.5) | 931 (4.2) | 0.047 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 108 | 14 (1.3) | 573 (2.6) | 0.319 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 110 | 12 (1.1) | 204 (0.9) | 0.573 |

| Stroke | 88 | 34 (3.1 | 156 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Myocarditis | 88 | 20 1.8) | 196 (0.9) | 0.189 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 87 | 14 (1.3) | 173 (0.8) | 0.076 |

| Epileptic seizures | 81 | 9 (0.8) | 134 (0.6) | 0.383 |

| Acute peripheral ischemia | 165 | 10 (0.9) | 101 (0.5) | 0.034 |

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold. N (%), number of cases (percentage); ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; IQR, interquartile range.

After adjusting for sex, age, dependence, COVID-19 wave, comorbidities, and treatment with corticosteroids and low-molecular-weight heparin, NC was associated with a lower risk of moderate/severe ARDS (aOR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.59–0.87; p = 0.001) but a higher risk of acute heart failure (aOR: 1.40; 1.12–1.72; p = 0.003) and sepsis (aOR: 1.73; 1.33–2.54; p < 0.001). Among NC patients, IHM (aOR: 2.07; 1.81–2.68; p < 0.001) and readmission (aOR: 1.35; 1.03–1.83; p = 0.028) were significantly more common (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ventilatory therapy, complications, and IHM in patients with NC versus CAC

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventilatory therapy | |||

| High-flow nasal cannula oxygen | 0.47 (0.76–1.17) | 1.04 (0.81–1.35) | 0.729 |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 0.97 (0.74–1.26) | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | 0.160 |

| Invasive mechanic ventilation | 0.59 (0.44–0.79) | 0.63 (0.36–1.11) | 0.111 |

| Outcome | |||

| Readmission | 1.70(1.32–2.19) | 1.35 (1.03–1.83) | 0.028 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 0.66 (0.52–0.85) | 1.08 (0.66–1.78) | 0.757 |

| IHM | 2.71 (2.39–3.07) | 2.07 (1.81–2.68) | <0.001 |

| Complications | |||

| ARDS, moderate/severe | 1.31 (1.15–1.50) | 0.72 (0.59–0.87) | 0.001 |

| Acute kidney failure | 1.73 (1.48–2.01) | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) | 0.908 |

| Pneumonia | 1.37 (1.15–1.65) | 1.04 (0.84–1.28) | 0.781 |

| Acute heart failure | 2.55 (2.13–3.06) | 1.40 (1.12–1.72) | 0.003 |

| Sepsis | 1.95 (1.60–1.28) | 1.73 (1.33–2.54) | <0.001 |

| Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome | 1.96 (1.59–2.41) | 0.89 (0.67–1.19) | 0.459 |

| Arrhythmia | 1.53 (1.20–1.97) | 1.05 (0.79–1.40) | 0.704 |

| Shock | 1.31 (1.00–1.71) | 0.79 (−0.55-1.15) | 0.230 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1.95 (0.84–1.69) | 1.28 (0.86–1.91) | 0.280 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 1.18 (0.65–2.12) | 0.81 (0.42–1.55) | 0.553 |

| Stroke | 1.60 (1.63–4.16) | 1.69 (0.97–2.92) | 0.061 |

| Myocarditis | 1.43 (0.83–2.48) | 0.83 (0.44–1.53) | 0.544 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1.63 (0.94–2.82) | 0.91 (0.50–1.65) | 0.776 |

| Epileptic seizures | 1.35 (0.68–2.66) | 0.93 (0.44–2.13) | 0.931 |

| Acute peripheral ischemia | 1.99 (1.04–3.83) | 1.48 (0.75–2.92) | 0.258 |

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold. Multivariable logistic regression analysis. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

After adjusting for sex, age, dependence, wave, comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, non-atherosclerotic heart diseases, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, dementia, diabetes mellitus, chronic pulmonary disease, malignancy, and moderate-severe renal disease), and treatment with glucocorticoids and low-molecular-weight heparin.

Mortality in NC Infection

The 30-day IHM as measured by the CFR was markedly higher among NC patients with respect to CAC patients (39.1 vs. 19.2), with a CFR risk difference of 19.93 (95% CI: 17.04–22.88). As with CAC patients, the CFR in NC patients increased with the age, from 5.6 in individuals <40 years to 54.9 in individuals ≥90 years. Excess mortality in NC patients compared to CAC patients was present in all age groups (Table 4). In NC and CAC patients, IHM occurred in a median (IQR) of 7 (3–13) and 7 (4–14) days from COVID-19 diagnosis, respectively, and the median (IQR) number of days from diagnosis to discharge in survivor patients was 13 (7–20) and 10 (6–16) days (p < 0.001), respectively.

Table 4.

Case fatality ratio (CFR) by age in patients with NC versus CAC

| Age range, years | Nosocomial |

Community acquired |

Risk difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N deaths/total N patients (% of 432 total deaths) | CFR | N deaths/total N patients (% of 4,245 total deaths) | CFR | ||

| <40 | 2/36 (0.5%) | 5.6 | 15/1,329 (0.4%) | 1.1 | 4.43 (0.34–17.02) |

| 40–49 | 10/55 (2.3%) | 18.2 | 51/2,151 (1.2%) | 2.4 | 15.81 (7.78–27.97) |

| 50–59 | 23/121 (5.3%) | 19.0 | 166/3,525 (3.9%) | 4.7 | 14.30 (8.26–22.23) |

| 60–69 | 49/167 (11.3%) | 29.3 | 468/4,442 (11.0%) | 10.5 | 18.81 (12.36–26.16) |

| 70–79 | 132/318 (12.0%) | 41.5 | 1,242/5,176 (29.3%) | 24.0 | 17.51 (12.10–23.12) |

| 80–89 | 166/316 (15.0%) | 52.6 | 1,715/4,265 (40.4%) | 40.2 | 12.32 (6.62–17.96) |

| ≥90 | 50/91 (11.6%) | 54.9 | 588/1,218 (13.8%) | 48.3 | 6.71 (−3.88 to 16.92) |

|

| |||||

| Total | 432/1,104 (100%) | 39.1 | 4,245/22,115 (100%) | 19.2 | 19.93 (17.04–22.88) |

Risk Factors for In-Hospital Complications and Mortality in NC Patients

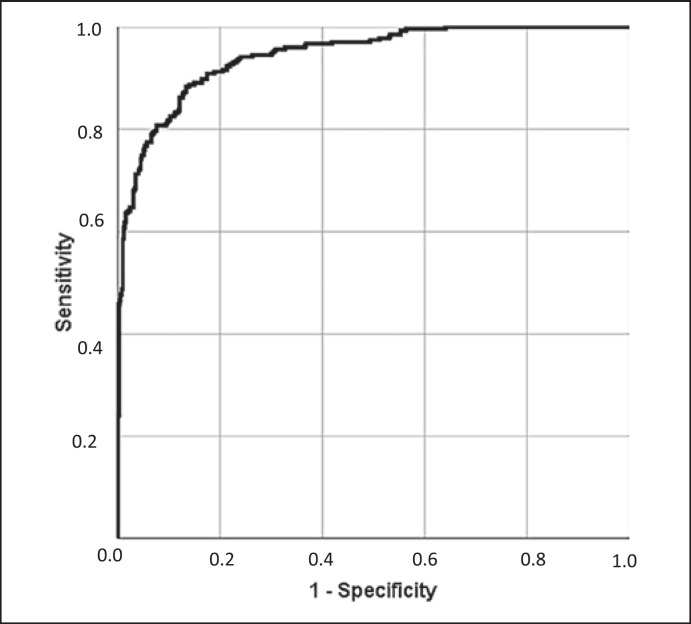

NC patients were divided into non-survivor and survivor subgroups and analyzed in terms of admitting clinical, radiological, and analytic parameters (online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000527711) and in-hospital treatment and complications (online suppl. Table 2). The factors significantly associated with IHM on the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis (Table 5). Risk factors associated with IHM in NC patients were age (aOR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.04–1.10; p < 0.001), severe dependence (aOR: 3.94; 1.53–10.1; p = 0.004), malignancy (aOR: 3.55; 1.91–6.59; p < 0.001), and the presence of dyspnea at diagnosis (aOR: 2.23; 1.20–4.09; p = 0.010), whereas the presence of odynophagia (aOR: 0.05; 0.008–0.43; p = 0.006) was associated with lower risk of death. The analytical variables related to non-survival were low platelet (aOR: 1.001; 1.000–1.002; p = 0.02) and CRP levels (aOR: 1.004; 1.000–1.007; p = 0.016). Finally, complications associated with IHM were moderate/severe ARDS (aOR: 29.4; 15.2–56; p < 0.001), multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (aOR: 107; 15–795; p < 0.001), and shock (aOR: 69; 95% CI: 3.25–1,497; p = 0.009). In this model, the p value for the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was 0.69 with an area under the curve of 0.944 (95% CI: 0.928–0.960), which indicates good predictive ability (Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Risk of mortality according to comorbidities and clinical, radiological, and analytical findings at diagnosis in patients with NC

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave (second vs. first) | 0.71 (0.53–0.95) | 0.023 | 0.91 (0.49–1.69) | 0.78 | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | <0.001 | |

| Sex (male) | 2.27 (1.01–1.37) | 0.034 | 1.06 (0.59–1.88) | 0.843 | |

| Degree of dependence | |||||

| Independent or mild | 1 | 1 | |||

| Moderate | 2.65 (1.95–3.58) | <0.001 | 1.80 (0.87–3.69) | 0.109 | |

| Severe | 3.36 (2.28–4.98) | <0.001 | 3.94 (1.53–10.1) | 0.004 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| CCI | 1.32 (1.25–1.399 | <0.001 | NI | ||

| Hypertension | 1.75 (1.35–2.27) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.30–1.07) | 0.080 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.57 (1.23–2.00) | <0.001 | 1.38 (0.77–1.48) | 0.278 | |

| Non-atherosclerotic heart diseasesa | 2.57 (2.11–3.52) | <0.001 | 1.83 (0.94–3.55) | 0.071 | |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseasesb | 1.23 (1.71–2,89) | <0.001 | 1.59 (0.77–2.89) | 0.123 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.77 (1.36–2.33) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.48–1.78) | 0.814 | |

| Chronic pulmonary diseasec | 1.78 (1.32–2.41) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.39–1.70) | 0.588 | |

| Malignancyd | 1.68 (1.27–2.27) | <0.001 | 3.55 (1.91–6.59) | <0.001 | |

| Dementia | 2.04 (1.45–2.88) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.26–1.74) | 0.417 | |

| Chronic kidney diseasee | 2.48 (1.75–3.54) | <0.001 | 2.02 (0.81–5.02) | 0.129 | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Dyspnea | 3.07 (2.38–3.99) | 0.001 | 2.23 (1.20–4.09) | 0.010 | |

| Arthralgia-myalgia | 0.55 (0.39–0.80) | 0.002 | 0.68 (0.29–1.59) | 0.386 | |

| Diarrhea | 0.68 80.47–0.96) | 0.042 | 1.19 (0.50–2.82) | 0.684 | |

| Ageusia | 0.11 (0.94–0.32) | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.00–3.15) | 0.075 | |

| Anomia | 0.068 80.01–0.28) | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.01–3.158 | 0.253 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.52 (0.32–0.869 | 0.009 | 2.82 (0.85–9.30) | 0.088 | |

| Abdominal pain | 0.49 (0.28–0.86) | 0.011 | 0.30 (0.06–1.43) | 0.133 | |

| Odynophagia | 0.52 80.30–0.91) | 0.020 | 0.05 (0.008–0.43) | 0.006 | |

| Physical examination | |||||

| Oxygen saturation ≤94% | 2.03 81.58–2.63) | <0.001 | 0.30 (0.06–1.35) | 0.078 | |

| Hypotensionf | 1.77 (1.18–2.66) | 0.005 | 2.10 (0.86–4.65) | 0.103 | |

| Tachycardiaf | 1.44 (1.08–1.929 | 0.012 | 1.86 (0.96–3.54) | 0.062 | |

| Tachypneaf | 3.57 (2.70–4.62) | <0.001 | 1.48 (0.77–2.85) | 0.231 | |

| Confusion | 3.38 (2.47–4.46) | <0.001 | 1.59 (0.78–3.33) | 0.213 | |

| Pulmonary rales | 1.52 (1.18–1.95) | 0.001 | 0.63 (0.35–1.13) | 0.124 | |

| Chest X-ray findings | |||||

| Normal | 1 | 1 | |||

| Unilateral infiltrates | 1.51 (1.05–2.16) | 0.026 | 1.19 (0.54–2.57) | 0.666 | |

| Bilateral infiltrates | 2.15 (1.68–2.98) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.62–2.46) | 0.547 | |

| Complete blood count | |||||

| Leukocytes, ×103/µL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.241 | |

| Neutrophils, ×103/µL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.241 | |

| Lymphocytes, ×103/µL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.435 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.87 (0.25–0.92) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.78–1.00) | 0.055 | |

| Platelet count, ×103/µL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.021 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.02 | |

| Arterial blood gases | |||||

| PO2, mm Hg | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| PO2/FiO2 ratio | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| Serum biochemistry | |||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.331 | |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.518 | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| ALT, U/L | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.540 | |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.016 | |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 1.05 (0.98–1.11) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| Serum ferritin, µg/L | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | <0.001 | NI | ||

| Complications | |||||

| ARDS, moderate/severe | 18.8 813-3-26.1) | <0.001 | 29.4 (15.2–56) | <0.001 | |

| Acute kidney failure | 4.64 (3.39–6.33) | <0.001 | 1.94 (0.97–3.88) | 0.059 | |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 2.68 (1.88–3.84) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.33–1.54) | 0.396 | |

| Acute heart failure | 3.92 (2.71–5.66) | <0.001 | 1.66 (0.71–3.92) | 0.242 | |

| Sepsis | 6.25 (4.09–9,79) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.39–2.83) | 0.916 | |

| Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome | 54.6 (19.9–149) | <0.001 | 107 (15–792) | <0.001 | |

| Arrhythmia | 2.17 (1.34–3.54) | 0.001 | 0.55 (0.19–1.54) | 0.258 | |

| Shock | 24 (8.98–69.3) | <0.001 | 69 (3.25–1497) | 0.009 | |

| Myocarditis | 3.98 81.24–12.7) | 0.012 | 0.14 (0.01–1.27) | 0.081 | |

| Epileptic seizures | 12.7 (1.6–1,029) | 0.002 | ND | ND |

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold. Bivariable and multivariable analysis. NI, not included; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Non-atherosclerotic heart disease includes atrial fibrillation and/or heart failure.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease includes coronary, cerebrovascular, and/or peripheral vascular disease.

Chronic pulmonary disease includes chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and/or asthma.

Malignancy includes solid tumors or hematologic neoplasms.

Chronic kidney disease is defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 according to the CKD-EPI equation.

Tachypnea (≥20 breaths per minute), tachycardia (≥100 breaths per minute), and hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the multivariable analysis of IHM in patients with NC

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of NC patients published to date. This work analyzed 1,104 NC cases, representing 4.8% of the total number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in a large multicenter registry of patients from 150 Spanish hospitals. NC patients were older, more dependent, and had more comorbidities than CAC patients. NC patients also had fewer symptoms and more often presented with a normal chest X-ray compared to CAC patients. However, overall IHM was significantly higher in NC versus CAC patients after adjusting for covariates. Heart failure and sepsis were major causes of mortality in NC patients, whereas ARDS was less common in this group than in CAC patients. The factors related to mortality in NC patients were age, level of dependence, malignancy, dyspnea, ARDS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and shock.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, several NC outbreaks have been reported which have affected both patients and healthcare workers [9, 18, 19, 20, 21]. Nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 can originate from healthcare workers; visitors; patients admitted for non-COVID-19 diseases who have mild disease, are pre-symptomatic, or are asymptomatic carriers; or from individuals with false-negative microbiological tests [22, 23, 24, 25].

Our percentage of NC patients (4.8%) out of the total number of patients is far lower than in previous reports. A preliminary article from Wuhan, China, reported a percentage of 41% [9, 26, 27]. In England, it has been calculated that 20% of COVID-19 cases in hospitalized patients are nosocomial [28]. The COPE-Nosocomial Study, a multicenter observational cohort of 1,564 hospitalized adults from ten British and one Italian hospital, reported a rate of NC infections of 12.5% [14]. A multicenter study from Scotland found a prevalence of NC of 11.0%, though this study had a small sample size and was conducted during a peak pandemic period in which the healthcare system was under pressure [29]. These differences are mainly explained by methodological differences between studies. First, compared to previous reports, our study includes the largest sample size of NC patients by far. Second, in some studies, only symptomatic patients were tested for COVID-19 in the hospital [29], whereas our sample included a high proportion of asymptomatic nosocomial infections and/or patients with normal chest X-rays. This may be due to the widespread use in our country of routine SARS-CoV-2 screening in patients hospitalized in COVID-19-free wards. Furthermore, we only included cases of patients admitted with non-COVID-19 diseases who were infected but not infections in healthcare workers or visitors, as other studies did [26, 30, 31, 32, 33]. Third, the definition of NC has yet to be definitively established and differs among studies. Given the wide variation in incubation periods and the high rates of asymptomatic/subclinical infection, accurate attribution of NC is challenging. We defined NC as patients admitted for non-COVID-19 diseases who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test after the fifth day of admission. Other studies used different cut-off days which ranged from 4 days after admission and the absence of clinical suspicion of COVID-19 [31], 5 days [29], 7 days [32], 8 days [33], or 14 days after admission [14, 34]. As the incubation period for COVID-19 could be up to 14 (IQR 2–7) days [35], we cannot rule out the possibility that some infections in our series were acquired before admission. All these aforementioned factors could lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of NC in our analysis. Finally, a key factor that could explain the low prevalence of NC found in our study was that most of the patients in the SEMI-COVID-19 Registry were included in the first wave, a period in which most beds in acute-care hospitals in Spain were occupied by COVID-19 patients.

In our study, compared to patients admitted with symptomatic COVID-19, patients with NC were older, more dependent, and had more comorbidities. These data are in accordance with other reports that show a higher risk of NC infection among vulnerable patient groups. In the COPE-Nosocomial Study [14], the median age of NC patients was 80 years and a higher percentage were moderately frail; a higher mortality rate has been associated with older age, increased frailty, and renal failure. Khan et al. [29] found that both male sex and adjusted CCI were predictive of 30-day mortality in patients who were not admitted to critical care units.

We found that NC patients had higher IHM and rate of readmission than CAC patients after adjusting for covariates. Other studies have not found worse outcomes among NC patients compared to CAC patients. Khan et al. [29] did not find significant differences in 30-day all-cause mortality rates between patients admitted with suspected COVID-19 (21.1%) and NC patients (21.6%); however, these results must be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. In the COPE-Nosocomial Study [14], NC was even associated with a lower IHM rate than CAC (aHR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.51–0.98). In that study, only patients hospitalized for more than 14 days were included in the definition of NC infection. The median number of days between the patient's admission and a positive COVID-19 test for NC infection was 32.5 days, whereas for CAC patients, the median was 0 days. These important disparities in the length of hospital stay could imply differences in both clinical status and supportive care between NC and CAC patients that could justify the lower mortality rate observed in NC patients. On the other hand, COVID-19 outbreaks among vulnerable hospitalized patients have been associated with elevated mortality rates, even as high as 50% [30, 33, 36]. Indeed, in a retrospective observational analysis of hospitalized older adults (mean age: 82 years) with COVID-19, nosocomial infection accounted for almost 50% of cases, and the 30-day mortality was 43% [34].

Some facts suggest that the elevated IHM rate among NC patients observed in our study may not be directly attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patients with NC were less symptomatic, more often had no radiological abnormalities, and developed ARDS − the main cause of COVID-19-related death − less frequently. In contrast, heart failure and sepsis were common causes of mortality in our NC population. This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may be acting as the “final nail in the coffin” for vulnerable hospitalized patients. Our data suggest that the higher NC mortality could be explained both by COVID-19 and by the primary cause of hospital admission itself.

Hydroxychloroquine was widely prescribed during the first wave. However, its use has not been shown to improve COVID-19 outcomes and indeed, it may even increase mortality due to cardiac arrhythmia, especially in old and very old vulnerable patients who have significant comorbidities [37]. Given that the use of hydroxychloroquine in our series was less frequent in NC than in CAC patients, the overall higher IHM observed in NC patients seems to be independent of this therapy.

The control of NC infections will continue to be a key goal in the near future while the pandemic persists. However, infection prevention and control of COVID-19 in the hospital settings is challenging due to a lack of evidence-based recommendations [38, 39], the particular characteristics of COVID-19 (high community infection rates; wide clinical spectrum, including frequent asymptomatic cases with capacity for transmission; highly contagious nature; potential false-negative results on diagnostic tests in asymptomatic patients or those whose diseases is of a short duration), and factors related to the structure and organization of hospitals (limited number of isolation rooms and difficulties in implementing containment measures for infection control).

To reduce the risk of in-hospital SARS-CoV-2 transmission and prevent nosocomial outbreaks, hospitals should implement contingency plans and infection prevention and control protocols. They must follow a multidimensional approach that includes the following essential measures [22, 31, 40]: (a) establish hospital isolation areas for inpatients with known or suspected COVID-19; (b) perform strict monitoring for nosocomial acute respiratory illness, especially in COVID-19-free areas; (c) strengthen universal measures of infection prevention, including use of masks, hand hygiene, proper ventilation, use of personal protection equipment when required, and regular cleaning and disinfection of all surfaces and medical equipment; (d) consider regular, widespread microbiological screening of all patients admitted to non-COVID-19 wards, staff, and visitors, particularly in vulnerable areas; and (e) limit patient movement between wards and the number of hospital visitors, including family, caregivers, and students.

The main strength of our study is the large number of patients analyzed and its multicenter, nationwide design. However, this study has several limitations. First, its observational design does not allow for determining causal relationships. Second, we did not have data on frailty and some geriatric syndromes (falls, delirium, malnutrition, etc.), factors that are decisive for outcomes in older adults for both CAC [5] and NC patients [34]. Third, we did not have information about the reasons for hospital admission in the NC population. Fourth, we cannot rule out the possibility that some patients were incubating SARS-CoV-2 at the time of admission. Fifth, our study was carried out in a developed Western country and may not be applicable to other settings with fewer healthcare resources.

In conclusion, our study shows that NC patients have a high risk of mortality, especially vulnerable patients who are elderly and who have significant comorbidities, considering the profound impact of nosocomial infection. Considering both the high mortality of NC infections and their considerable prevalence (almost 5% of cases) observed in our series, COVID-19 should be considered one of the most frequent and dangerous nosocomial infections. This suggests that it is necessary to reconsider our overall approach to the prevention of future nosocomial infections spread via droplet transmission, which continue to occur even when standard precautions are taken.

Statement of Ethics

All patients gave informed consent. All patients gave their informed consent, oral or written, for inclusion. In the periods of maximum hospital care pressure (March to April 2020, November 2020 to January 2021), it was almost impossible for patients to give written consent. At this time, they gave verbal consent reflected in the EMR by the physician approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Málaga on March 27, 2020 (Ethics Committee code: SEMI-COVID-19 27-03-20), as per the guidelines of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Products. In this work, all data collected, processed, and analyzed were anonymized and used only for the purposes of this project. All data were protected in accordance with the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of April 27, 2016, on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committees of each participating hospital.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

None declared.

Author Contributions

Jose-Manuel Ramos-Rincon and Ricardo Gomez-Huelgas were responsible for the design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. Almudena Lopez-Sampalo, Lidia Cobos-Palacios, Michele Ricci, Manel Rubio-Rivas, Raquel Díaz-Simón, María-Dolores Martín-Escalante, Sabela Castañeda-Pérez, Rosa Fernández-Madera-Martínez, Jose-Luis Beato-Perez, Gema-Maria García-García, María-del-Mar García-Andreu, Francisco Arnalich-Fernandez, Sonia Molinos-Castro, Juan-Antonio Vargas-Núñez MD, Arturo Artero, Santiago-Jesús Freire-Castro, Jennifer Fernández-Gómez, Pilar Cubo-Romano, Almudena Hernández-Milián MD, Sandra-Maria Inés-Revuelta, Ramon Boixeda, and Elia Fernández-Pedregal contributed to data acquisition and data interpretation. Jose-Manuel Ramos-Rincon, Almudena Lopez-Sampalo, Lidia Cobos-Palacios, Michele Ricci, Manel Rubio-Rivas, Raquel Díaz-Simón, María-Dolores Martín-Escalante, Sabela Castañeda-Pérez, Rosa Fernández-Madera-Martínez, Jose-Luis Beato-Perez, Gema-Maria García-García, María-del-Mar García-Andreu, Francisco Arnalich-Fernandez, Sonia Molinos-Castro, Juan-Antonio Vargas-Núñez MD, Arturo Artero, Santiago-Jesús Freire-Castro, Jennifer Fernández-Gómez, Pilar Cubo-Romano, Almudena Hernández-Milián MD, Sandra-Maria Inés-Revuelta, Ramon Boixeda, Elia Fernández-Pedregal, and Ricardo Gomez-Huelgas revised the research design and the manuscript, as well as approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Appendix

List of the SEMI-COVID-19 Network members: a complete list of the SEMI-COVID-19 Network members is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Funding Statement

None declared.

References

- 1.COVID-19 dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) at johns hopkins university (JHU) Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (Accessed May 15, 2022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323((20)):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casas-Rojo JM, Antón-Santos JM, Millán-Núñez-Cortés J, Lumbreras-Bermejo C, Ramos-Rincón JM, Roy-Vallejo E, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Spain results from the SEMI-COVID-19 registry. Rev Clin Esp. 2020;220((8)):480–494. doi: 10.1016/j.rce.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernabeu-Wittel M, Ternero-Vega JE, Díaz-Jiménez P, Conde-Guzmán C, Nieto-Martín MD, Moreno-Gaviño L, et al. Death risk stratification in elderly patients with covid-19 A comparative cohort study in nursing homes outbreaks. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;91:104240. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos-Rincon JM, Buonaiuto V, Ricci M, Martín-Carmona J, Paredes-Ruíz D, Calderón-Moreno M, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in very old patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Spain. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76((3)):e28–e37. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((16)):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang T, Ding S, Zeng Z, Cheng H, Zhang C, Mao X, et al. Estimation of incubation period and serial interval for SARS-CoV-2 in jiangxi and an updated meta-analysis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15((3)):326–332. doi: 10.3855/jidc.14025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wee LE, Conceicao EP, Sim XYJ, Aung MK, Tan KY, Wong HM, et al. Minimizing intra-hospital transmission of COVID-19 the role of social distancing. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105((2)):113–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Zhou Q, He Y, Liu L, Ma X, Wei X, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Eur Respir J. 2020;55((6)):2000544. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00544-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in wuhan China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6((7)):1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SCY, Kwong RTS, Wu TC, Chan JWM, Chu MY, Lee SY, et al. Risk of nosocomial transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 an experience in a general ward setting in Hong Kong. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105((2)):119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harada S, Uno S, Ando T, Iida M, Takano Y, Ishibashi Y, et al. Control of a nosocomial outbreak of COVID-19 in a university hospital. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7((12)):ofaa512. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landoas A, Cazzorla F, Gallouche M, Larrat S, Nemoz B, Giner C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 nosocomial infection acquired in a French university hospital during the 1st wave of the Covid-19 pandemic a prospective study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10((1)):114. doi: 10.1186/s13756-021-00984-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter B, Collins JT, Barlow-Pay F, Rickard F, Bruce E, Verduri A, et al. Nosocomial COVID-19 infection examining the risk of mortality The COPE-Nosocomial study (COVID in Older PEople) J Hosp Infect. 2020;106((2)):376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryg J, Engberg H, Mariadas P, Pedersen SGH, Jorgensen MG, Vinding KL, et al. Barthel index at hospital admission is associated with mortality in geriatric patients a danish nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1789–1800. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S176035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rius C, Pérez G, Martínez JM, Bares M, Schiaffino A, Gispert R, et al. An adaptation of Charlson comorbidity index predicted subsequent mortality in a health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57((4)):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307((23)):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li YK, Peng S, Li LQ, Wang Q, Ping W, Zhang N, et al. Clinical and transmission characteristics of covid-19 a retrospective study of 25 cases from a single thoracic surgery department. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40((2)):295–300. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2176-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewkes SV, Zhang Y, Nicholl DJ. Nosocomial spread of COVID-19 lessons learned from an audit on a stroke/neurology ward in a UK district general hospital. Clin Med. 2020;20((5)):e173–e177. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao S, Yuan Y, Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Deng L, Chen T, et al. Two outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 in department of surgery in a Wuhan hospital. Infect Prev Pract. 2020;2((3)):100065. doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor J, Rangaiah J, Narasimhan S, Clark J, Alexander Z, Manuel R, et al. Nosocomial COVID-19 experience from a large acute NHS trust in south-west london. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106((3)):621–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treibel TA, Manisty C, Burton M, McKnight Á, Lambourne J, Augusto JB, et al. COVID-19 PCR screening of asymptomatic health-care workers at London hospital. Lancet. 2020;395((10237)):1608–1610. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, Kimball A, James A, Jacobs JR, et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((22)):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Wu S, Xu L. Asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 as a concern for disease prevention and control more testing, more follow-up. Biosci Trends. 2020;14((3)):206–208. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.03069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323((22)):2249–2251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323((11)):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Q, Gao Y, Wang X, Liu R, Du P, Wang X, et al. Nosocomial infections among patients with COVID-19 SARS and MERS a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8((10)):629. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans S, Agnew E, Vynnycky E, Stimson J, Bhattacharya A, Rooney C, et al. The impact of testing and infection prevention and control strategies on within-hospital transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in english hospitals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021;376((1829)):20200268. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan KS, Reed-Embleton H, Lewis J, Saldanha J, Mahmud S. Does nosocomial COVID-19 result in increased 30-day mortality? A multi-centre observational study to identify risk factors for worse outcomes in patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Infect. 2021;107:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biernat MM, Zińczuk A, Biernat P, Bogucka-Fedorczuk A, Kwiatkowski J, Kalicińska E, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a haematological unit - high mortality rate in infected patients with haematologic malignancies. J Clin Virol. 2020;130:104574. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Praet JT, Claeys B, Coene AS, Flore´ K, Reynders M. Prevention of nosocomial COVID-19 another challenge of the pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41((11)):1355–1356. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soe WM, Balakrishnan A, Adhiyaman V. Nosocomial COVID-19 on a green ward. Clin Med. 2020;20((6)):e282. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.Let.20.6.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montero MM, Hidalgo-López C, López-Montesinos I, Sorli L, Barrufet Gonzalez C, Villar-García J, et al. Impact of a nosocomial COVID-19 outbreak on a non-COVID-19 nephrology ward during the first wave of the pandemic in Spain. Antibiotics. 2021;10((6)):619. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10060619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis P, Gibson R, Wright E, Bryan A, Ingram J, Lee RP, et al. Atypical presentations in the hospitalised older adult testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 a retrospective observational study in Glasgow, Scotland. Scott Med J. 2021;66((2)):89–97. doi: 10.1177/0036933020962891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019 retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when patients novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected interim guidance. 2020. Jan 28, Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of (Accessed 30 October 2021)

- 37.Fteiha B, Karameh H, Kurd R, Ziff-Werman B, Feldman I, Bnaya A, et al. QTc prolongation among hydroxychloroquine sulphate-treated COVID-19 patients an observational study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75((3)):e13767. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rickman HM, Rampling T, Shaw K, Martinez-Garcia G, Hail L, Coen P, et al. Nosocomial transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 a retrospective study of 66 hospital-acquired cases in a london teaching hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72((4)):690–693. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Infection prevention and control and preparedness for COVID-19 in healthcare settings-third update Available from https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/infection-prevention-and-control-and-preparedness-covid-19-healthcare-settings (Accessed July 21, 2021)

- 40.Islam MS, Rahman KM, Sun Y, Qureshi MO, Abdi I, Chughtai AA, et al. Current knowledge of COVID-19 and infection prevention and control strategies in healthcare settings a global analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41((10)):1196–1206. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.