Abstract

Patients with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) are known for being difficult to treat. Treatment for ASPD is debated and lacking evidence. Among several reasons for treatment difficulties concerning ASPD, negative countertransference in health personnel is one central topic. Mentalization based treatment (MBT) is a reasonable candidate treatment for ASPD. From an ongoing pilot-study on MBT with substance using ASPD patients, we explore therapist experiences. Four experienced MBT therapists together with the principal investigator performed a focus group together. The therapists were themselves involved in performing this study and analyses are made as an autoethnographic study, with thematic analyses as methodological approach. As this study involved a qualitative investigation of own practice, reflexivity of the processes was performed. The aim was to explore in depth: therapist experiences and therapist wellbeing in MBTASPD. We found four main themes on therapist experiences: i) gaining safety by getting to know them better; ii) gaining cooperation through clear boundaries and a non-judgmental stance; iii) shifting inner boundaries; and iv) timing interventions in a highspeed culture. These four themes point to different therapist experiences one can have in MBT-ASPD. Our findings resonate well with the clinical literature on ASPD, the findings imply that clinical teams should have a focus on therapist countertransference and burnout, ensure that therapists uphold boundaries and openmindedness in treatment of ASPD and that therapists experience vitalizing feelings in this line of work.

Key words: Mentalization-based treatment, antisocial personality disorder, therapist experience, focus group, hermeneutical phenomenological epistemology

Introduction

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is a hard-toreach patient group where group therapy has been suggested as an important arena for change (Meloy & Yakeley, 2014), as this patient group is assumed to learn more from peers than therapists. However the usefulness of group therapy for the severe personality disordered patients is still unclear since these groups often deteriorate into chaotic and pseudomentalizing sessions (Inderhaug & Karterud, 2015). For therapists, ASPD pose great challenges by evoking countertransference and loss of optimism on the treatment potential. These challenges are known, but little research has been performed on therapist well-being and therapist countertransference with this patient group.

Antisocial personality disorder characteristics and substance use disorder

ASPD is characterized by three out of the seven following traits: i) failure to conform to social norms; ii) deceitfulness; iii) impulsivity; iv) irritability or aggressiveness; v) reckless disregard for safety of self or others; vi) consistent irresponsibility; and vii) lack of remorse. In addition, a diagnosis of conduct disorder must have been present in childhood, the individual must be over 18 years old and antisocial behavior must be present outside of manic or psychotic episodes (APA, 2013). Many or most patients with ASPD have also substance use disorders (SUD), studies indicate a correlation of as much as over 90% (Goldstein et al., 2007). Among patient populations with SUD, ASPD appear to be the most common PD followed by BPD and paranoid PD (Trull et al., 2010). A systematic review found that among SUD patients around 22% have comorbid ASPD (Verheul, 2001). The high comorbidity between ASPD and SUD is potentially due to the impulsivity difficulties among this patient group and perhaps due to ASPD high correlation with narcissistic traits and the potential reward pathway of using substances. Both impulsivity and the reward pathway are considered etiological pathways between PD and SUD (Verheul & van den Brink, 2005). Thus treatment facilities in health services for addiction medicine need to inform themselves on personality disorder combined with SUD.

Mentalization based treatment

Mentalization based treatment (MBT) is a well-known treatment for patients with personality disorder (PD), mainly borderline (BPD) (Bateman & Fonagy, 2016). Group therapy is a major component of MBT and is seen as key for improving mentalizing difficulties. MBT for BPD has received a great deal of empirical support through clinical trials and naturalistic studies (Storebø et al., 2020). MBT has also been clinically tested through one pilot study for patients with ASPD (McGauley et al., 2011). However, for ASPD, studies on treatment efficiency and effectivity are scarce (Gibbon et al., 2020). In fact, there is no compelling evidence for psychotherapeutic treatment, although there is limited evidence that dialectical behavioral therapy, contingency management, and schema therapy could provide better effect on outcome compared to the control (Gibbon et al., 2020). MBT have shown potential on reducing aggression (McGauley et al., 2011), and a larger RCT study is now ongoing in London (Fonagy et al., 2020). Furthermore, MBT have found treatment effects for patients with BPD with comorbid ASPD in a RCT by subgroup analyses (Bateman et al., 2016). In addition, there are two studies that found that MBT works better for patients with more severe personality problems (Bateman & Fonagy, 2013; Kvarstein et al., 2018), indicating perhaps a treatment potential for ASPD including those with comorbidity of substance use. Combined these studies demonstrate that MBT is a reasonable candidate treatment for ASPD. However, no RCT studies has been performed with ASPD, and the latest Cochrane review was not optimistic on recommendations for treatment as the studies are few, have mixed results and the evidence has low quality (Gibbon et al., 2020).

Treatment challenges and treatment hope

ASPD patients are considered particularly difficult to treat and have been known for negative reactions and countertransference from health services and personnel (Bateman, 2019). These patients often experience stigmatization and exclusion from health and social services due to their frightening appearance, or interpersonal strategies based on instrumentality or deceitfulness (Yakeley & Williams, 2014). Professionals often exclude them from treatment once its known that there is a history of antisocial behavior and violence, and there is a widespread belief that ASPD is untreatable among health personnel (Bateman et al., 2019). However, the newer perspectives on ASPD as a developmental disorder related to attachment disturbances, bring hope for early intervention in families at risk and children with conduct disorder, as well as informing treatment for adults with the diagnosis (Yakeley & Williams, 2014). In Germany an RCT on MBT with adolescents with conduct disorder is under way and could provide positive results on early intervention for this patient group (Taubner et al., 2021). The most effective treatments for ASPD are characterized by a focus on linking affect to actions, a focus on countertransference, take place in a physically secure setting, include individual therapy, and enforce strict rules and boundaries (Yakeley & Williams, 2014). Furthermore, there is hopefully an increasing consensus among health practitioners that evidence based approaches should be offered to patients (Gazzillo et al., 2017).

Mentalization based treatment for antisocial personality disorder vs the original mentalization based treatment

MBT-ASPD is a new adaptation of MBT. The MBTASPD compared to the original MBT includes some changes. Treatment duration is shorter, 12 months, with monthly intervals between individual sessions and weekly intervals between group sessions. The therapists have the dual role as both group and individual therapist. A group session is 75 minutes long, as opposed to 90 minutes. The interventions and focus are tailored to the typical ASPD mentalizing difficulties (Bateman et al., 2013). More emphasis is put on upholding the frames and structure in treatment. MBT-ASPD also primarily targets male patients, as the ASPD diagnosis is most common in men (Bateman et al., 2019). In MBT-ASPD the similarities with MBT original are that the patients receive combination treatment with group and individual therapy sessions, they have a case formulation and if they need it a crisis plan. In this study the patients also got access to a MBT informed social worker that provides help with social and economic needs, with a particular focus on establishing a mentalizing communication with external collaborators. The MBT informed social worker is recommended when offering MBT to substance using patients (Arefjord et al., 2019). The team has regular video-based supervision where the focus is on how to tailor interventions to the patients’ specific needs and to follow the treatment model. The primary goal of the treatment is to increase mentalizing in the patients. As for the interventions, the MBTASPD manual holds the not-knowing stance together with upholding the structure in the session, as key quality overarching interventions. Furthermore, in MBT-ASPD focus is on the following (Bateman et al., 2013):

‘1) Understanding emotional cues: external mentalizing and its link to internal states.

2) Recognition of emotions in others: other/affective mentalizing.

3) Exploration of sensitivity to hierarchy and authority: self/cognitive.

4) Generation of an interpersonal process to understand subtleties of others’ experience in relation to ones’ own: self/ other mentalizing and

5) Explication of threats to loss of mentalizing which lead to teleological understanding of motivation: self/other mentalizing and self/affective mentalizing.’

The main principle is to facilitate the development of mentalizing while at the same time avoiding interactions that decrease mentalizing. An overarching goal of the treatment is to generate the ‘we-mode’, a mental state where sharing and understanding mind states of self and others is central (Bateman et al., 2021; Bateman, 2022). The ‘we-mode’ is a prerequisite for prosocial behaviour, as opposed to violence and exploitation of others.

Antisocial personality disorder mentalizing difficulties

The mentalizing profile of patients with ASPD is typically overly external, cognitive and automatic. Compared to other PDs, their mentalizing failures are more globally severe, and the failure in mentalizing is assumed to be related to the attachment system, which is activated via threats to the identity or self (Bateman, 2022). One study found that the tendency for non-mentalizing and hypomentalizing are more marked among ASPD compared to offenders without ASPD and compared to a control group of non-offenders. In this study they could predict offender status by their mentalizing subscales (Newbury-Helps et al., 2017). Hypo-mentalizing and non-mentalizing is in effect turning of the focus on mental states of others and self. This is understood as a risk factor for violence, since they cannot imagine the subjective mental state of the other person, and therefore have a lower threshold for performing violence. In fact, mentalizing has been found to prevent violence in people with psychopathic traits (Taubner et al., 2013). The activation of the attachment system is understood as important in the psychological dynamics of their mentalizing. The theory is that threats to self or identity will activate the attachment system, and this will impair the individuals mentalizing capacity and their focus on mental states in others will be compromised (Newbury-Helps et al., 2017). An attachment view on the psychological deficits of the patients, as opposed to a trait deficit is of key importance in the clinical work with ASPD. People with ASPD are often above average in external, cognitive, and automatic mentalizing abilities (Bateman et al., 2019). Being able to understand cognitively, but without connecting with the affective experience, is a prerequisite of the ability to deceive people. Generally, people with ASPD don’t care much for others, and are normally instrumentally motivated when it comes to engagement in relations, they also tend to be fixed on one pole of the self-other dimension depending on the situation (Bateman et al., 2019). As for their relational strategies, they normally seek hierarchical relationships that are more rigidly organized, like for instance gangs, and which implies why group work with ASPD is considered most beneficial (Meloy & Yakeley, 2014).

Therapist experiences

Considering the therapist experiences while working with ASPD, the importance of working with structured therapy manuals in a team-based manner are emphasized (Bateman et al., 2015). In MBT, these matters are implemented in the manual. The counter transferential aspect of therapeutic work with PD can be quite demanding for a solo therapist, and therefore supervision is important (Betan et al., 2005). Furthermore, the ASPD patient can be particularly emotionally demanding for therapists. Meloy & Yakeley (2014) propose a list of common countertransference reactions to ASPD; which are therapeutic nihilism, illusory treatment alliance, fear of assault, denial and deception, helplessness and guilt, devaluation and loss of professional identity, hatred, and the wish to destroy, assumption of psychological complexity and fascination together with sexual attraction. Another characteristics of ASPD is for instance that their non- mentalizing is characterized by ‘ranting’ about others with highly derogatory words (Bateman et al., 2019). This is a manner of speaking about others that can be emotionally distressing for therapists to endure. One study that compared countertransference between ASPD and schizophrenia found that ASPD gave much more negative feelings than the latter. With ASPD therapists experienced feelings of being dominated (exploited, manipulated, and talked down to) as opposed to more positive feelings of being liked with patients that had schizophrenia (Schwartz et al., 2007). This study was using videotapes of proposed clients and did not tap on actual treatment of ASPD or schizophrenia. A second study investigated patient personality and therapist response with the Therapist Response Questionnaire, and found that ASPD together with paranoid PD were associated with criticized and mistreated countertransference in the therapist (Colli et al., 2014). A newly published study that investigated therapist experience in an MBT-ASPD program (Warner & Keenan, 2021), describes negative experiences in part due to limited organizational support and frames. These therapists were running an MBT-ASPD program in the community and reported having to step out of their own comfort zone in order to meet clients’ needs, feeling confusion around the MBT model, threats to their professional identity and being at risk for burnout. The authors explain their negative findings to the most part due to gaps in the service infrastructure. However, there is a scarcity of studies investigating ASDP and therapist experience. Thus, there is a knowledge gap on how therapist experience ASPD and the specifics of their counter transferential experiences.

Aims

The aim of this study is to explore in depth: How is therapeutic work and therapist wellbeing experienced in MBT ASPD from the therapist perspective?

Materials and methods

This study was performed as an autoethnographic selfreflective study (Råbu et al., 2021) on own practice where three therapists and two researchers investigate therapist experiences in MBT-ASPD. MBT-ASPD is a new development within treatment for PD. The MBT- Substance use disorder (SUD) team in Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway has performed research and clinical work with PD/SUD patients since 2010, but the main clinical focus has been on BPD/SUD (Arefjord et al., 2019). As the newer developments of MBT was going in the direction of ASPD (Fonagy et al., 2020), and because many of the patients in our MBT-SUD program had ASPD, we wanted to provide more targeted treatment for this group. In August 2021, we launched a feasibility study on MBT for male patients with ASPD/SUD. Data-collection will be performed until we have recruited a minimum of 30 patients, and the pilot study is still ongoing. An expert in MBT-ASPD is providing supervision for the team monthly. All sessions are videotaped, and the team has two video-based supervisions with the MBT-SUD team weekly.

The background for this autoethnographic study is that we were invited to do a lecture on therapist experiences with ASPD some months into the pilot study. The PI interviewed two therapists (MØ and TM) on various themes on MBT-ASPD. As the interview developed and we explored different themes within the MBT-ASPD, our curiosity increased. Many aspects of working as a therapist in MBTASPD appeared different than MBT for BPD/SUD patients. We wanted to explore in greater detail what it was like to work within this framework compared to the ordinary MBT-SUD that we were used to. Furthermore, as a regular procedure in the pilot study, the PI and the therapists have a monthly status meeting, discussing the progress of the study and investigating positive and negative therapy processes. The reports from these meetings together with the interview on therapist experiences paved way for a curiosity to explore these experiences more scientifically. As a result of this we decided to do a focus group study within an autoethnographical frame (Kitzinger, 1994; Råbu et al., 2021). When performing qualitative studies, reflexivity is an important tool for ensuring transferability and trustworthiness of the study (Finlay & Gough, 2003; Malterud, 2001). These concepts are the equivalents to reliability and validity within a quantitative framework. This seemed particularly important for us when exploring our own experiences as therapists, so that our interpretations would go beyond the local cultural and implicit knowledge that we potentially have developed as a group of colleagues working together for years.

The transcript of the focus group discussion has been analysed for themes related to the aim of the study. Findings that were surprising or involved conflicting perspectives were especially highlighted. The themes were first categorized as phenomenological or descriptive as possible resulting in twelve ‘near to experience’ subordinate themes. These were then reorganized and categorized in superordinate themes, which resulted in four themes that encompassed the different phenomenological subthemes. The superordinate themes had a higher level of interpretation to them, and we attempted to lift the themes to a hermeneutic level, where our knowledge and preconceptions came to play. For instance, the subthemes ‘therapist experience of surprise’, ‘learning from the patients’, ‘therapist expectations’ and ‘changing as a therapist’ were all enclosed in the superordinate theme ‘gaining safety by getting to know them better’. See Table 1 for an overview of this process of organizing subthemes into superordinate themes.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity in qualitative research is first and foremost about turning a critical view on own standpoints and perspectives as a researcher (Finlay, 2003) and investigate thoroughly where our thinking and conclusions stem from. Reflexivity can be defined as ‘the project of examining how the researcher and intersubjective elements impact on and transform research (Finlay & Gough, 2003)’. In a study like this one, where five close colleagues with different roles in relation to each other, are running a pilot study on therapy with male patients with ASPD and SUD, there are many potential pitfalls and difficulties that can pop up along the way. We were very preoccupied with at least two major concerns prior to and during the analyses. First, are we able to be transparent and honest with each other in the focus group or are there hidden and unspoken issues that will not be addressed? Second, are we able to critically explore our findings and our work with this patient group? The patient group has been described in the literature as producing negative emotions in health personnel (Meloy & Yakeley, 2014), this could potentially cloud the interpretation of the findings, because we are not aware of own emotional reactions. Furthermore, we are all fans of MBT as we have worked within this framework most of our careers, are we able to be critical against ‘our own baby’, will we be able to see shortcomings and issues in this treatment? To deal with these concerns one of the things we did in the analyses was to search for surprises among the findings. We thought that by searching for surprising findings, we would be able to identify themes that were not part of our preconceptions. In essence, if we surprised ourselves, the finding would have some element of novelty in it. Another element of the analyses which had the intention of dealing with the potential pitfalls named above, was to investigate moments of tension and conflicting perspectives among us, these different views have been of particular interest to us, as they potentially demonstrate different areas of experiences therapist can have within this particular context. This is also one of the strengths of collaborative reflexivity as it offers the opportunity to consider different voices and perspectives in dialogue with each other (Finlay, 2003). In this cooperative inquiry as both co-researcher and co-participant our efforts at improving validity and trustworthiness are also demonstrated by the inclusion of the interview guide (Figure 1) and an attempt of thoroughly describing the analytic process in the methods section so that the whole research procedure is transparent to the reader.

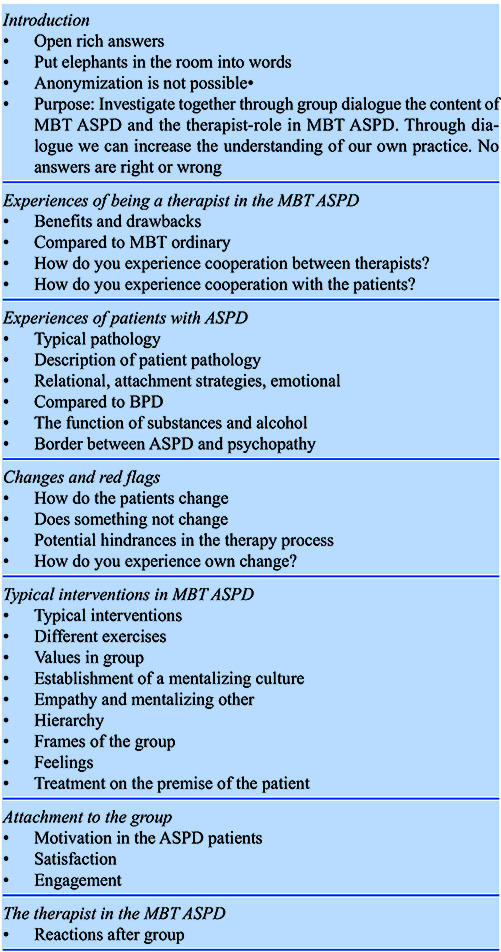

Figure 1.

Interview guide: Focus group.

Table 1.

Themes and subthemes of therapist experience.

| Therapist experience themes | Therapist experience subthemes |

|---|---|

| Gaining safety by getting to know them better | Therapists are surprised |

| Learning from the patients | |

| Therapists expectations | |

| Therapist changes | |

| Gaining cooperation through clear boundaries and a non-judgmental stance | Boundaries and frames |

| Therapist authority | |

| Therapist directness | |

| Shifting inner boundaries | The vibe in the room |

| Therapist countertransference | |

| Difficult to intervene on vulnerable emotion | |

| Timing interventions in a high-speed culture | The vibe in the room |

| Timing of interventions | |

| Therapist feelings |

Participants

The participants in this study are four MBT therapists, one MBT social worker. They are all involved in the pilot study for Mentalization based treatment of antisocial personality disorder in Norway. See Table 2 for an overview of therapist experience, training, and age.

Clinical context and patient severity

The MBT-SUD team is situated in the public health sector in Bergen, Norway as an outpatient treatment program within addiction health services. MBT-SUD offers the full MBT program according to the manuals for patients with combined PD and SUD. The team consists of 7 therapists and one social counsellor and runs 5 full MBT programs; 3 for female PD-/SUD patients, 2 for male PD/SUD patients where one is the MBT-ASPD program. The team offers gender specific treatment, females and males are not mixed in the groups. The patients that were in treatment during this focus group study had the following clinical characteristics, see Table 3.

Thematic analyses

Thematic analyses are an a-theoretical approach that can be utilized within qualitative research within various different theoretical frameworks (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The purpose of the thematic analyses is to investigate the themes which can be found in the transcribed text and keep them as close to lived experience as possible. Within a hermeneutical-phenomenological approach the oscillation between the level of description and interpretation will produce findings that are situated within the zeitgeist of the researchers, and in the context of which the research has been performed. Reflexivity is of great importance to ensure that the findings are transparent and replicable for other researchers from other similar scientific contexts. In the analyses we have followed a procedure with the following steps (Binder et al., 2012):

i) All authors note and reflect upon the process and content in the focus group and make notes on different important processes or themes that come to mind after participation in the focus group

ii) All authors read all the transcribed material to obtain a basic sense of the participants’ experiences. A gradual recognition through dialogue of some personal and professional preconceptions is also part of this phase.

iii) Examining those parts of the text relevant to the research question, the researcher leading the project identifies separable content units that represent different aspects of the participants’ experiences.

iv) The leading researcher (or the team) develops ‘meaning codes’ for those units, which are concepts or keywords attached to a text segment to permit its later retrieval.

v) The leading researcher (or the team) interprets and summarizes the meaning within each of the coded groups of text fragments into conceptions and overall descriptions of meaning patterns and themes. These should reflect, according to consensual understanding in the team, what emerges as the most important aspects of the participants’ experiences.

vi) The research team turns back to the overall text to check whether voices and points of view shall be added and can develop the conceptions and descriptions of themes further or represent correctives to the preliminary line of interpretation. vii) The themes are finally formulated and agreed upon by the whole research team.

Table 2.

Therapist experience and formal training in mentalization based treatment.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P1 | P2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49 | 47 | 39 | 42 | 35 |

| Years in an MBT team | 6 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 7 |

| Years as a therapist | 10 | 18 | 1 | 14 | 7 |

| Formal training/Certification in MBT | MBT-Individual MBT-Group MBT Supervisor | MBT-Individual MBT-Group | MBT-Introductory course | MBT-Individual MBT Supervisor | MBT-Group |

Table 3.

Patient’s personality disorder and social functioning.

| N | Mean | Range | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11 | 37 | 26-49 | 6.6 |

| Number of SCID-5 PD criteria | 10 | 20 | 10-26 | 4.3 |

| ASPD childhood (SCID-5 PD) | 10 | 8 | 3-15 | 3.4 |

| ASPD adult (SCID-5-PD) | 10 | 5 | 4-7 | 1.1 |

| GAF lowest score | 10 | 52 | 41-65 | 7.6 |

Results

Following our research question, we investigated the therapist experience of ASPD in a treatment program offering MBT. We found four superordinate themes on therapist experience which all point to different experiences that therapist can have while working with this patient group in an MBT program.

Gaining safety by getting to know them better

This theme illustrates a process of change within the therapists from a position of anxiousness and uncertainty to a sense of safety and competence. This process of change within the therapists started with prior expectations and preconceptions, followed by moments of surprise during the phase where they got to know the patients, then gaining more knowledge on how they ‘typically are’ and through this, gaining a higher level of competence and safety as a therapist. Typically, the therapists would feel nervous prior to the sessions, and fear aggressive outbursts or conflicts in the group. One therapist explains the worries they had prior to treatment:

‘T2: I worried, will there be conflicts, will they start fighting, what do we need to manage here, and what are the consequences, will they contact each other outside treatment, there were many uncertainties’.

After some time in the treatment the therapists were surprised by how patients so easily are calmed down after moments of anger or after a conflict between them. For instance, one therapist explains it like this:

T1: That it so quickly passes, that has surprised me with these patients, they can be pretty annoyed and argumentative and then (..) they are just done with it’.

Discovering that patients are not holding grudges for long, and that their anger quickly goes down leads to a sense of increased competence in the therapist, who feels more confident in intervening and being direct.

‘T1: I have gotten to know them better, or we have gotten to know each other really, and they are less suspicious maybe, and I think I am more direct than before, with time I discovered that they can handle quite a lot really’.

Furthermore, the therapists describe aspects of patients psychological functioning that surprised them. For instance, patients demonstrate high motivation for changing and for working therapeutically on their relational and emotional issues. The therapists are surprised by how clear patients express this desire (When a new member enters the group, all group members present their relational and psychological problems, the emotional compass).

‘T2: I was surprised last time they presented themselves (..) what they want to work on, why they are in group. I became very impressed by how clear they were. I have problems with this, I want to work with that, I want to change this and that.’

The therapists are also surprised by how some patients seem to feel much more comfortable in the ASPD group than they did when previously participating in MBT-BPD groups. They notice that these patients seem calmer, less stressed, show better recall of events, and are more communicative. Furthermore, therapist feelings of own competence and safety are related to finding ways of engaging with the patients that seem to improve the relationship between them. For instance, being open and transparent as illustrated in this group exercise used in MBT-ASPD where both therapist and patients are sharing their typical interpersonal pattern in the group:

‘T2: We wanted the patients to talk about their pattern, and we figured that we as well should share our pattern (…) I think this was very okay for them, or that’s the feedback they gave us, so, I think they got some respect.’

Therapist feeling of safety is also affected by the quantity and cooperation with the co-therapist as illustrated here:

‘T2: They do not get as angry as I had thought, I imagined that if we were very direct with them, that they would be more like ‘I disagree’ and argumentative and stuff, but they take it quite fine. (..) it also has to do with our cooperation, because we have been through a process, we have not had group together before, we needed to figure out, how to cooperate and we have tried different ways. That’s an assurance for me.’

However, the therapists still do not know if patients really change or have benefits by receiving MBT for ASPD. The feelings the therapists have regarding the treatment has changed into something positive, and in the focus group we were surprised by how certain and clear they expressed their positive feelings:

‘T1: In the beginning it was more like, I don’t know, a type of anxiousness, insecurity, but this has disappeared somewhat.

T2: I look forward to the groups!

PI: So, you are not lying awake the day before the group?

T2: No, I look forward!

PI: You don’t worry on how to do it, how to manage?

T1: No not anymore.

PI: Or that the patients act out?

T1: No

T2: No, I look forward. I get disappointed if the group is cancelled.’

In summary this theme illustrates that therapists experience preconceptions and fear when engaging with patients with ASPD. Even therapists who are highly trained in a specialized treatment program for PD and who have experience with this patient group have unwarranted preconceptions about their prognosis and pathology. The quality of treatment seemed to increase by gathering these patients in a group of their own. As therapists have experience with treating these patients individually and in groups of other PD patients, the essential aspect of getting to know them were also seeing them in a group ‘of their own’ and getting to know how they typically interact with each other. The therapists experienced the patients as more relaxed and open. The therapists were also surprised by the patients’ motivation and their tolerance for therapeutic interventions and being spoken directly to. An increased sense of both safety and competence came to the therapists as they got to know the patients better.

Gaining cooperation through clear boundaries and a non-judgmental stance

This theme illustrates how the subject of authority, boundaries and structure are important themes when working as a group therapist with ASPD. The therapists experience that compared to ordinary MBT groups, they need to put more effort into working with structure and boundaries. They also experience the need to position themselves in the group, as they felt somewhat on the outside and not to be ‘reckoned with’ in the first phases of the treatment. The therapists also notice that patients seem to be more preoccupied with the ‘rules’ of group therapy than patients with BPD, and prefer to receive clear guidance on what is expected of them:

‘T3: They seem very preoccupied with the rules of the group, for instance not giving advice, they arrest themselves quickly when they give advice, they stop. They care about showing up, and to provide something, like when the group is summarized ‘today we did good, today was a good day’ (…) I am not sure this is the case in the other groups.’

Therapists are surprised by how much patients appreciate that they are direct, and that their efforts at addressing boundaries are tolerated and accepted. Therapists are also surprised by their own ability to be direct, which is different from previous work in MBT/BPD groups. One of the therapists was intervening when two patients were having an argument prior to a group session:

‘T1: I was pretty surprised myself; I came into the group and two of them were having a noisy dispute (…) they were quarrelling like cats and dogs (…) it was pretty loud, and then it was almost as if I was outside of myself hearing me saying ‘stop that! let’s do this in the round’

In addition, the therapists discover that when patients engage in the group with efforts to help their fellow patients, they are more direct, concise, and conservative with their interventions, and this leads to increased mentalizing. The therapists feel that they can learn from the patients, to tailor their interventions better. Patients seem to listen more to each other, and sometimes provide more relevant comments to each other than the therapists. The therapists experience that they have gained a position in group, but that they are still somewhat outside of the gang

‘T2: This thing about hierarchy, it feels somehow like I am left out of it, because I am on the outside of the gang.

PI: Because you’re a woman?

T2: Yes

T1: Yes, but me too, I have the same feeling of being left out of the hierarchy. In the beginning it was a bit like ‘who do you think you are?’

PI: Did you have to be submissive then for this to settle down? Is that how it works?

T1: No, I don’t think so, it was more being open, I think.

P2: So, you didn’t challenge it?

T1: I didn’t challenge it, but I didn’t approve of it either

(..)

T2: No, you just stayed calm and said okay, and then moved on

(...)

P1: You don’t play the positioning game at all…?

T1: No

P1: You meet them with equality and respect, is that the position you take?

T1: Yes, that’s my goal (…) I don’t point the finger, I don’t know better than them’.

Therapists experience that even though they feel like outsiders, the patients respect and listen to them. Being clear and transparent, together with reminding the patients of agreed boundaries, appear to be mental stances that the therapists feel are helpful in their effort to cooperate better with the patients. Another important aspect in this theme is the duality between offering treatment on the premise of the patient, while at the same time upholding boundaries and expectations. The therapists experience this oscillation as important in the cooperation and relationship with the patients:

‘T1: I think it should be on their premises, within a certain structure. That this is important, that it must be very clear what the setup is, that this is how it is. But the goals of the treatment, what you want to work on, that is on their premises.

(..)

T2: We ask them, what do you want to change, and then we take it seriously what they want, and often it’s on relationships, they want better lives. And then we have a firm structure where we expect them to train on this.’

The therapists address that not being judgmental towards the patients, and having an open mind, allowing patients to decide treatment goals for themselves, are important aspects of establishing a cooperative relationship. The therapists underline that the premises and structure of the treatment are clear, the patients are expected to work on something related to mentalizing. They have monthly individual sessions and weekly group sessions. Within this frame, therapist experience the importance of being non-judgmental and open.

‘T1: We have psychoeducational groups, this is how we think, this is what we feel are important for treatment, this is what it takes, and then it’s up to the patient if they accept this or not, they can say that this is crap, but most get hooked right away, they recognize themselves and find it exciting (…) when it’s on their premises its more on their lives, we are not moralistic like ‘no that’s not possible’ or ‘you cannot use violence’

(...)

T2: I am not motivating them; they need to figure this out themselves.

T3: They are not censured when they talk, and I think they experience this as okay, that when they share an incident or a story, that you are not sitting their rolling your eyes, that there is room.’

For the therapists, being able to uphold structure and at the same time relate to patients on their own premises is experienced as essential for stimulating a therapeutic change process. This therapeutic stance could be described as authoritative.

Shifting inner boundaries

This theme is about having to endure interacting with patients who are without boundaries and often trespass the therapist level of comfort. One challenge for the therapists has been that patients sometimes are unpredictable and unbounded on subjects like for example females, sex, violence, and drugs. In other words, they do not behave according to social norms, and the content of their discussions can be emotionally distressing.

‘T2: I think about all those comments, (…), generalizing about women, devaluation, talk about, they have been incredibly outspoken with, direct questions, sexual stuff, (…) I have told them that, or like I have shared my experience of it or my feelings on it, I have been very clear that, it is not okay that you talk like this’.

This can challenge the therapists into losing the ability to think clearly and that they don’t know what to do and how to intervene. On the other hand, the therapists have noticed that these types of dialogue are less common now than in the beginning, and that the patients often stress that it’s a joke and they didn’t mean it. Here therapists are imitating how patients take back their comments in group.

‘T1: ‘and then they immediately stop and take it back (..)

T2: ‘It is just a way we speak; it is just an expression; we don’t mean it like that’’

For the female therapists it can be challenging to manage these situations without losing mentalizing. Another aspect of the ASPD groups and therapist loss of mind, is that a typical characteristic trait of the ASPD groups seems to be little contact with vulnerable emotions, and a more playful / oppositional tone of interaction. The therapists experience a shift away from emotions and therefore finds themselves entertained by the easy-going and playful tone instead of managing to intervene by for instance focus on the feelings.

‘T1: at times it is very entertaining, they have stories that just make you think ‘oh shit, it is just like a movie!’

T2: yes, it is easier to get the temperature up then down.

P1: But what are the negative consequences?

T2: I get more tired working with these patients

T1: It is a problem that you become too much in your head, I get influenced by their mentalizing pattern, I become like that myself.’

Therapists find it challenging to bring out vulnerability in different topics that seem to have an underlying state of vulnerable emotion.

T3: It does not seem like they recognize their emotions, and it is hard to get them to describe ‘what did that feel like?’

Also, the therapists themselves find it easy to get drawn into the ‘antisocial logic’, where violence is reasonable. They must put effort into enduring challenging relational and emotional processes.

‘T1: On my part, I experience a shift in my boundaries more in the moment, because of the tempo and all that is going on, I cannot connect emotionally (…)’.

Furthermore, therapists experience changes in their own typical way of being, for instance some report a shift toward a higher level of tolerance for violence and aggression while others report becoming more scared and anxious in their private life. One therapist experienced becoming more badass and less anxious in private situations. Therapists fear that they are shifting their tolerance level for aggression and violence, and that they should be supervising this process.

‘T3: I notice in my private life, (…), recently I was in an episode on a playground and there was someone who was acting out in a car, you know with traffic lights and screaming and shouting, I just stood there watching and just, I did not notice it happening and my partner he was pretty agitated ‘what’s happening here?’ (…) Afterwards I thought, I should have walked away, I was there with my kids, I should have walked away, but I just stood there’.

Furthermore, some experience becoming more concerned and ‘on the watch’ in their own private lives, and some experience becoming more ‘badass’, less worried and more externalizing. Therapists underline the importance of taking care of each other and watch each other’s mental and emotional process, as they go on working with this patient group.

‘T2: Its violence and sex, and sometimes I just feel like getting up and leave, that I cannot stand it anymore (…) It’s difficult to explain what it is I am feeling, but it is too much (…) I think we have to be aware, how much, how much we shall tolerate’.

Therapists felt monthly individual sessions as opposed to more frequent individual sessions, was helping on keeping some distance to the most disturbing subjects that could come up in sessions.

Timing interventions in a high-speed culture

This theme is about therapist experience of the group culture. The culture in the group is characterized as fast paced with a lot of talking, jokes, and sometimes humorous but mocking interactions between patients. In general, the therapists experience difficulties following and keeping track of patients’ mental states, and difficulties finding opportunities for interventions. All the therapists agree on their experience of the high tempo in group and difficulties with intervening in the right moment.

‘T1: For me it’s like this, when one patient is on the go and has started something, it is difficult to interrupt, because, you know, normally people stop when others start talking to them, but these patients often don’t, they just continue talking, and you don’t get any room, so therefore the timing is much more important, you have to wait until there is a little opening, and there you have to enter.’

This high tempo group culture is demanding for the therapists, with being able to keep up with the tempo and stay on track with the therapeutic focus:

‘T2: (…) I also find it challenging in relation to my own mentalizing (…) because it is so quick, and I am not that quick to begin with, I react a little late. Compared to the other groups, where things are a bit slower, and you have better time, and then you can (…) think about it, it is easier to rewind (…) because when I try to rewind, they have sort of moved on and it is not so relevant anymore.’

Therapists compare the group culture to being at an afterparty with lots of ‘life’. A phenomenon that also for a short moment of time entered our focus-group and our dialogue suddenly imitated the group culture in the ASPD group:

‘P2: I get the impression of a train that comes and just runs over everything; it looks intense, even though the vibe is good, there is a lot of pressure

T2: (…) we plan something

T1: yes, and then it just all falls apart because it just

T2: What just happened? It all happens so fast

T1: So, we have worked on getting the tempo down

(…)

P1: So how we are talking right now, that is not even close to how an ASPD group is looking?

P2: No

T1: No

P1: This is calm?

T1: This is calm

P2: This is calm

P1: Like this is really calm?

P2: It is like an afterparty on the love boat or something, they sit there and

T3: and throw

P2: Throw snuff to each other

T2: Eat some

T2: Someone is talking, while another one is talking, what’s happening over there, oh right he is talking

(…)

T3: But they talk out loud, they are not low-key, the volume in their voices is very high

P2: and lots of laughter and cheering

T3: They laugh and hit their thighs’.

This theme also encompasses how the therapists are drawn into the external and cognitive mentalizing profile of the patients, finding themselves being entertained like if they were watching an action movie. Related to this they experience a feeling of ‘unreal’ or detached quality to the events described. Furthermore, the timing of interventions is crucial to gain control of the mentalizing processes in the group, but also the quality of the interventions is of importance. The therapists are surprised by how the patient’s own interventions sometimes start mentalizing processes in others, by engaging co-patients in a way that was better matched to their mentalizing level:

‘T1: They are more preoccupied with what their copatients are saying than what we are saying (…) often they listen more to the others and the interventions that they can make use of is often coming from other group members (…) in addition, it seems that their comments are more in tune with the level of mentalizing than ours (…)

T2: Yes, that is just it, they are more concrete, more direct, and we are more like

T1: Yes, much more psychological

T2: Yes, can you take her perspective? What do you think she felt? That is not working out as well as when they…’

The therapists are excited, and they enjoy that there is ‘temperature’ in the group. They feel that a lot of effort is put on calming the patients down, and there is seldom a need for interventions that gets the ‘temperature’ up.

‘T1: I think we use more time on calming down, structure, calming down, like a lot more focus on this, getting the temperature down, get them into a frame and a structure, compared to the other treatments

T2: And then this thing about, how, we said it before, short, we must be more careful with the timing, like when we intervene, timing, being short, it’s a different way of working’.

Therapists also feel that they get very tired by working this way, and that they lose affectivity and become more cognitive in their minds with this type of group therapy. Sometimes they have problems memorizing content and process from the group:

‘T2: I become more tired working with them

P1: Tired?

T2: Yes, so much is happening and so quickly. And it is just ‘aaaaa’, you are working ongoing, you are more…

P1: But is it more cognitive exhaustion or emotional exhaustion or what?

T2: Both I think, mostly cognitive I think (…) We talk together after group right, and it is like, what happened today? What was it?’

The art of therapy with ASPD seem to be to find the right moment to intervene, as the group culture do not allow much talk from the therapists. In addition, clear and concise interventions is understood as important. Therapists report both positive feelings and exhaustion by this particular aspect of ASPD groups.

Discussion

Our findings resonate well with the clinical literature on MBT ASPD.

Treatment pessimism

First the findings point to that therapists underestimate motivational and positive prognostic factors with these patients before they gain experience with treating them, many have underlined this problem with treatment pessimism in the literature (Bateman et al., 2019; Yakeley & Williams, 2014). As we don’t know yet the results of our pilot study, we are careful with concluding on the potential of the treatment. However, from the therapist perspective, there have been positive surprises on how much these patients are motivated to change and how much they enjoy being taken seriously and getting access to treatment tailored to their needs. Perhaps understanding ASPD from the point of view of attachment is indeed fruitful as we can identify why we should offer tailored treatments primarily in the group format and endure ASPD typical mentalizing issues better (Bateman et al., 2019; Mc- Gauley et al., 2011). Furthermore, the importance of focusing on the alliance in group has been underlined by others (Bateman et al., 2021; Coco et al., 2019). In our findings, therapist gain a good alliance by upholding a not-knowing stance together with structuring the sessions. In the MBT-manual these are two overarching principles for MBT quality and adherence, and we do not know if the reason that our therapists here underline these two strategies is in part due to their training as MBT therapists. The alliance, in the sense of collaborating around the goals of treatment appears to be more positive than therapists expected.

Firm boundaries in treatment of antisocial personality disorder

Second, our findings confirm the importance of boundaries and structure. We propose that employing boundaries together with respect for the patient is a helpful approach. As a parallel to this, one study found that friendly submissiveness in therapists was negatively related to the alliance, which informs us of the importance of an authoritative therapist (Cain et al., 2018). It seems from our findings that also the patients feel safer in a context of clear rules and expectations, the trick is of course to implement a curious and flexible focus on mental stances inside this framework. We are curious as to the reasons of why these patients apparently experience more safety by contexts that have a clear framework and explicit boundaries. The MBT-ASPD recommends that these patients partake with making their own principles and values for the group, and as to the perspective of involving patients in own treatment process through establishing joint collaboration (Bateman, 2022), we understand why this is important. But as to the actual part of the treatment to have ‘rules’ in the group, this is different from the other MBT groups, and we are curious on why this is so important with ASPD. Perhaps due to how ASPD organize themselves in gangs with clear structures for different roles like we typically see in male dominated criminal subcultures (Bateman et al., 2019). We also suspect that the lower the mentalizing the higher need for structure and steering? Newbury-Phelps and colleagues (2017) found that compared to other offenders, ASPD has more non-mentalizing and concrete mentalizing. Could their mentalizing deficits have anything to do with how and why they feel safer in context of clear expectations, after all social contexts where expectations and boundaries are more floating, do demand at certain capacity for mentalizing in order to manoeuvre sufficiently. Perhaps investigations on the patient perspective can shed light on this aspect of treatment with ASPD.

Countertransference with antisocial personality disorder

Not surprisingly, we found indicators that the emotional strain in therapists can be quite demanding when working with ASPD. There seem to be individual differences between the therapists on how they became influenced by the work, in the sense that we had descriptions of therapists that became more externalizing and less afraid, while others described more fear and hypervigilance. Perhaps there are gender differences in how patients effect therapists, or perhaps these differences are more individual? Furthermore, the differences could be related to prior relationships with patients as some therapists were treated individually for a longer period in the recruitment phase of the treatment. Nevertheless, it seems to be important to have procedures ensuring that therapists communicate well together on own reactions, and that therapists’ reactions are supervised by each other. That therapists have different countertransference reactions to the patient group is known in the clinical literature of ASPD. We recognized some of the counter transferences that were described by Yakeley and Meloy, like for instance fear of assault, helplessness and guilt, assumption of psychological complexity and fascination (Meloy & Yakeley, 2010). We worry that some of our positive findings on the alliance and cooperation with the patients are due to a countertransference of illusory treatment alliance. Furthermore, we suggest that our experiences of feeling cognitively tired and exhausted after group, our problems with remembering content from the group, and our experience of taking over the patients mentalizing momentarily during the group, are interesting supplements to what is already written about therapist experiences and countertransference with ASPD. We have no specific suggestion for a solution other than the importance of creating an open and transparent mentalizing environment for the therapists, and that supportive measures need to be taken. Perhaps we should also have a specific eye on the female therapists, as both of our female therapists in this project reported a various degree of discomfort with how patients could be personal and sort of mocking towards them in group or individual therapy. We follow the ASPD-MBT literature that suggests that in response to patients’ teleological explanations of for instance relationships, therapist juxtaposition of own mental states is suggested (Bateman et al., 2013). In our findings juxtaposition of own mental state, that is to say to the patients how we feel in the moment contrasting their view, were experienced as important in order to deal with patients who talk about difficult subjects without boundaries. We feel it is important to underline that it is hard to work with these patients, and all therapists experienced changes in their private lives and own psychological functioning to various degrees. We support the notion of taking this aspect of working with ASPD very seriously and that organizations and therapists are strict on their need to uphold the framework of the treatment. We find the conclusions from a similar study as our own interesting, as their findings are much more negative, and therapists seem to be more loaded and strained in their MBT-ASPD work (Warner & Keenan, 2021). If the framework around the treatment delivery is not solid, there are potential consequences on the outcome of treatment as well, as we have seen in the studies from the Netherlands with young severe BPD inpatients. Their effect sizes on outcome in an inpatient facility delivering MBT were half after organizational turmoil, and there were no changes at the team or therapist level, which makes these findings even more interesting (Bales et al., 2017).

High-speed group culture

Fourth, it was intriguing to discover how full of life and tempo work with ASPD can be, and interesting that therapist struggle so much with the literal timing of when to get a word in. This type of group culture poses different challenges than other types of groups with PD patients. The tempo had both positive and negative aspects, and we think that a specific focus in how to deal with this particular challenge in MBT-ASPD would be interesting to further develop. We suspect that this high tempo of the group culture has in part to do with hierarchical interpersonal strategies of the patient group, and that taking the room with entertaining stories is one way of positioning yourself. Perhaps even a prosocial manner of positioning yourself since the stories are meant to be entertaining and often has aspects of trying to be supportive of each other. On the other hand, some of the patients are more direct and impulsive than others. Impulsivity is a core problem for patients with ASPD, but not for all patients with ASPD. Temperature and the level of entertainment in the group varies with the individual patients present. Is a high tempo and the party like quality of the dialogue an example of pseudomentalizing, the antisocial version? Pseudomentalizing has been described as potentially very destructive in group therapy (Esposito et al., 2021). Therapists often have problems with discovering when pseudomentalizing is present, they lack authority to steer the group away from pseudomentalizing and furthermore, we assume that a pseudomentalistic dialogue does not have the potential to produce change. Inderhaug & Karterud (2015) has written well about pseudomentalizing in groups, they suggested that therapist failed to manage authority and overplayed the not-knowing position as an explanation for chaotic group sessions. Esposito and colleagues (2021) have made an important contribution to the understanding of pseudomentalizing in groups with substance addicted patients, where they suggest that there are three types of pseudomentalizing where the intrusive type is perhaps what is most recognizable in our study. The intrusive pseudomentalizing appears certain about mental states and lacks any connection between thoughts and feelings (Esposito et al., 2021). Since pseudomentalizing does not appear in all group sessions, the therapeutic style (MBT-adherence) probably matters in generating a mentalizing dialogue (Esposito et al., 2021). The high tempo described from the therapists in this study suggests that they struggle with chaotic group sessions, and we suspect that pseudomentalizing is the dominant mental stance in the patients in these moments. We don’t know if therapists have failed to implement authority or if the patient group is specifically impaired when it comes to normal societal communicational norms, like waiting for your turn, listen to the other, and stop and rewind. But in the ASPD manual the therapist position is suggested as that of authority in the sense the therapist keeps patients on the ‘task’, but at the same time take the position as the group’s servant, that steers only to get patient back on track and intervenes with the purpose of increasing mentalizing in the patients (Bateman et al., 2019). Utilizing the case formulation in group therapy could be a useful therapeutic intervention to deal with the deterioration and chaos which can appear with severe personality disorder (Karterud, 2018).

Are we on the way of gaining pro-sociality and mentalizing?

We do not investigate effect of treatment or patients experience in this study. We look forward to investigating these questions scientifically in publications down the road. Nevertheless, we ask the question if ASPDMBT has something to offer, from the therapist perspective. The quick answer is that we do not know. Treatment optimism has been surrounding the team since launching the pilot. In fact, we are so optimistic that we wanted to investigate our experiences scientifically as we did in this study. However, deep diving into our experiences demonstrated for us that some of our experiences are negative, and that negative implications on therapist well-being is one possible outcome of working as an MBT-ASPD therapist. Another aspect of this work that worries us is the concept of illusory treatment alliance (Meloy & Yakeley, 2010). There has been a collective sense of good and fruitful collaboration with the patients in group, at the same time we suspect that pseudomentalizing is dominating the group culture and this would imply that little change will happen with patients’ level of mentalizing. Could it be that we are blind to a potential lacking effect of the treatment? However, the positive processes of getting to know the patients better, being surprised by patients’ level of motivation and tolerance for differing perspectives and gaining more competence as clear and concise therapists leads us to carefully conclude, that even though there is uncertainty, there is also hope. We look forward to the first results from the RCT in London (Fonagy et al., 2020), and the RCT on adolescents with conduct disorder in Germany (Taubner et al., 2021). Hopefully, treatment pessimism on ASPD will look different during the coming decade.

Conclusions

This focus group study investigated therapist experiences with MBT-ASPD. We found four major themes on therapist experiences. Through getting to know the patients better, and how they related to their peers in group therapy, therapist experienced fewer negative preconceptions and more confidence in their role as a clear and concise therapist. Second, therapists experienced that upholding boundaries and clear expectations to patients together with a non-judgmental stance, was essential as overarching strategies in MBT ASPD. Third, countertransference and changes in therapist psychological functioning needs to be monitored and supportive measures must be taken to manage therapist countertransference. Lastly, there is a specific characteristic of MBT-ASPD groups that involves high tempo and a mocking humorous interaction, this group culture both excited and exhausted the therapist.

Limitations and future directions

This is a small qualitative study performed by five colleagues within an autoethnographical framework performing a focus group. There are many potential pitfalls with this methodology like bias, preconceptions, blindness to findings, and producing conclusions that were already made prior to the study. We have tried to be transparent about the analytical process and reflexive on these potential pitfalls as is recommended in qualitative methodology (Malterud, 2001). Critical voices on collaborative reflexivity and studies on own practice is that the process of compromising and negotiations between researchers could potentially reduce the complexity of the insights compared to single researcher studies (Finlay, 2003; Halkier, 2010). There could be some elements of truth to this critique, although we would also like to stress that as this could be the case for some of our findings, other parts of our findings became richer and more complex because of the negotiations between us. We could also investigate the potential conflicts and potential disagreements between us, which has enrichened the analyses of the data.

There is very little research on therapist experience with ASPD, the studies we found point to very differently emotionally laden experiences. The importance of organizational structures should be investigated further so that we can scientifically establish contextual mechanisms important in this line of work. Furthermore, we know little of the mechanisms of change with ASPD. Suggestions on the importance of group therapy has been made both in the clinical literature and in national guidelines (NICE, 2009). There is a need for process studies and qualitative investigations on how patients experience mechanisms of change in MBT groups, and process studies that investigate mechanism of change through other analytical methods.

Acknowledgements

This study has been performed in the Department of Addiction Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital (HUS) and costs of running this project are covered by HUS. This study is performed in cooperation with the Research group of Personality Disorder, Oslo University Hospital and the National Network for Personality Disorder, Oslo University Hospital. We thank all patients that are participating in the ASPD feasibility study.

Funding Statement

Funding: this study has received funding from The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters.

References

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Arefjord N., Morken K. T. E., Lossius K. (2019). Comorbid Substance Use Disorder and Personality Disorder. In Bateman A., Fonagy P. (Eds.), Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice. American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bales D. L., Timman R., Luyten P., Busschbach J., Verheul R., Hutsebaut J. (2017). Implementation of evidence-based treatments for borderline personality disorder: The impact of organizational changes on treatment outcome of mentalization- based treatment. Personality and Mental Health, 11(4), 266-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Bolton R., Fonagy P. (2013). Antisocial personality disorder: A mentalizing framework. Focus, 11(2), 178-186. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. (2013). Impact of clinical severity on outcomes of mentalisation-based treatment for borderline personality disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(3), 221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Campbell C., Fonagy P. (2021). Rupture and repair in mentalization-based group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 71(2), 371-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. (2016). Mentalization-based treatment for personality disorders - A practical guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A. W. (2022). Mentalizing and group psychotherapy: a novel treatment for antisocial personality disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 75(1), 32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Gunderson J., Mulder R. (2015). Treatment of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385(9969), 735-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Motz A., Yakeley J. (2019). Antisocial personality disorder in community and prison settings. In Anthony Bateman P. F. (Ed.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice - Second edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., O’Connell J., Lorenzini N., Gardner T., Fonagy P. (2016). A randomised controlled trial of mentalizationbased treatment versus structured clinical management for patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry 16(1), 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betan E., Heim A. K., Zittel Conklin C., Westen D. (2005). Countertransference phenomena and personality pathology in clinical practice: an empirical investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(5), 890-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder P.-E., Holgersen H., Moltu C. (2012). Staying close and reflexive: An exploratory and reflexive approach to qualitative research on psychotherapy. Nordic Psychology, 64(2), 103-117. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [Google Scholar]

- Cain L., Perkey H., Widner S., Johnson J. A., Hoffman Z., Slavin-Mulford J. (2018). You really are too kind: implications regarding friendly submissiveness in trainee therapists. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 21(2), 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coco G. L., Tasca G. A., Hewitt P. L., Mikail S. F., Kivlighan J. D. M. (2019). Ruptures and repairs of group therapy alliance. An untold story in psychotherapy research. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 22(1), 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colli A., Tanzilli A., Dimaggio G., Lingiardi V. (2014). Patient personality and therapist response: An empirical investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G., Formentin S., Marogna C., Sava V., Passeggia R., Karterud S. W. (2021). Pseudomentalization as a Challenge for Therapists of Group Psychotherapy With Drug Addicted Patients. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2003). The reflexive journey: mapping multiple routes. Reflexivity: A practical guide for researchers in health and social sciences, 3-20. doi:10.1002/9780470776094.ch1. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L., Gough B. (2003). Reflexivity: A practical guide for researchers in health and social sciences. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Yakeley J., Gardner T., Simes E., McMurran M., Moran P., Crawford M., Frater A., Barrett B., Cameron A. (2020). Mentalization for Offending Adult Males (MOAM): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to evaluate mentalization-based treatment for antisocial personality disorder in male offenders on community probation. Trials, 21(1), 1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzillo F., Schimmenti A., Formica I., Simonelli A., Salvatore S. (2017). Effectiveness is the gold standard of clinical research. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 20(2), 278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon S., Khalifa N. R., Cheung N. H., Völlm B. A., Mc-Carthy L. (2020). Psychological interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(9), CD007668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R. B., Compton W. M., Pulay A. J., Ruan W. J., Pickering R. P., Stinson F. S., Grant B. F. (2007). Antisocial behavioral syndromes and DSM-IV drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(2-3), 145-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkier B. (2010). Fokusgrupper. Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS. [Google Scholar]

- Inderhaug T. S., Karterud S. (2015). A qualitative study of a mentalization-based group for borderline patients. Group Analysis, 48(2), 150-163. [Google Scholar]

- Karterud S. (2018). Case formulations in mentalization-based group therapy. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 21(3), 318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall T., Pilling S., Tyrer P., Duggan C., Burbeck R., Meader N., Taylor C. J. B. (2009). Borderline and antisocial personality disorders: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ, 338, b93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J. (1994). The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health & Illness, 16(1), 103-121. [Google Scholar]

- Kvarstein E. H., Pedersen G., Folmo E., Urnes Ø., Johansen M. S., Hummelen B., Wilberg T., Karterud S. (2018). Mentalization-based treatment or psychodynamic treatment programmes for patients with borderline personality disorder - the impact of clinical severity. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92(1), 91-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K. (2001). Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet, 358(9280), 483-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGauley G., Yakeley J., Williams A., Bateman A. (2011). Attachment, mentalization and antisocial personality disorder: The possible contribution of mentalization-based treatment. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 13(4), 371-393. [Google Scholar]

- Meloy J., Yakeley J. (2014). Antisocial personality disorder. In Gabbard G. O. (Ed.), Gabbard’ s treatments of psychiatric disorders, Fifth Edition (pp. 1015-1034). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Meloy J. R., Yakeley J. (2010). Psychodynamic treatment of antisocial personality disorder. In Clarkin J. F., Fonagy P., Gabbard G. O. (Eds.), Psychodynamic psychotherapy for personality disorders: A clinical handbook (pp. 289-309). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Newbury-Helps J., Feigenbaum J., Fonagy P. (2017). Offenders with antisocial personality disorder display more impairments in mentalizing. Journal of Personoality Disorders, 31(2), 232-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Råbu M., McLeod J., Haavind H., Bernhardt I. S., Nissen-Lie H., Moltu C. (2021). How psychotherapists make use of their experiences from being a client: Lessons from a collective autoethnography. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(1), 109-128. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. C., Smith S. D., Chopko B. (2007). Psychotherapists’ countertransference reactions toward clients with antisocial personality disorder and schizophrenia: An empirical test of theory. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 61(4), 375-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storebø O. J., Stoffers-Winterling J. M., Völlm B. A., Kongerslev M. T., Mattivi J. T., Jørgensen M. S., Faltinsen E., Todorovac A., Sales C. P., Callesen H. E. (2020). Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubner S., Hauschild S., Kasper L., Kaess M., Sobanski E., Gablonski T.-C., Schröder-Pfeifer P., Volkert J. (2021). Mentalization-based treatment for adolescents with conduct disorder (MBT-CD): protocol of a feasibility and pilot study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 7(1), 1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubner S., White L. O., Zimmermann J., Fonagy P., Nolte T. (2013). Attachment-related mentalization moderates the relationship between psychopathic traits and proactive aggression in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(6), 929-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull T. J., Jahng S., Tomko R. L., Wood P. K., Sher K. J. (2010). Revised Nesarc Personality Disorder Diagnoses: Gender, Prevalence and Comorbidity with Substance Dependent Disorders. Journal of Personality Disorder, 24(4), 412-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R. (2001). Co-morbidity of personality disorders in individuals with substance use disorders. European Psychiatry, 16(5), 274-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R., van den Brink W. (2005). Causal pathways between substance use disorders and personality pathology. Australian Psychologist, 40(2), 127-136. [Google Scholar]

- Warner A., Keenan J. (2021). Exploring clinician wellbeing within a mentalization-based treatment service for adult offending males with antisocial personality disorder in the community. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 1-11. [Google Scholar]

- Yakeley J., Williams A. (2014). Antisocial personality disorder: new directions. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 20(2), 132-143. [Google Scholar]