Abstract

Recently, attachment-informed researchers and clinicians have begun to show that attachment theory offers a useful framework for exploring group psychotherapy. However, it remains unclear whether patients with differing attachment classifications would behave and speak in distinct ways in group therapy sessions. In this study, we conducted an exploratory analysis of the discourse of patients in group therapy who had independently received different classifications with gold standard interview measures of attachment in adults. Each patient participant attended one of three mentalization-based parenting groups. Before treatment, the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) or the Parent Development Interview (PDI) were administered to each patient, and interviews were transcribed and coded to obtain the patient’s attachment classification. Groups included 2, 5, and 5 patients, respectively, and any session was led by at least two co-therapists. A total of 14 group sessions were transcribed verbatim. Sessions were analysed through a semi-inductive method, in order to identify markers that would typify patients of different attachment classifications in session. Through transcript excerpts and narrative descriptions, we report on the differing ways in which patients of different attachment classifications communicate in group psychotherapy, with the therapist and with each other. Our work provides useful information for group therapists and researchers regarding how differences in attachment status may play out in group sessions.

Key words: Groups, discourse analysis, mentalization, adult attachment interview, epistemic trust

Introduction

In the past two decades, attachment theory has been increasingly used to inform and advance group psychotherapy practice and research (Marmarosh, 2019; Parks & Tasca, 2021). To some, the application of attachment theory to a group context may be counterintuitive. Attachment relationships are defined as relationships between two individuals: one in distress, alarmed or in pain, and another one who is perceived as wiser and stronger, and as capable of offering protection (Bowlby, 1969/1982). Yet, pioneering researchers have recently begun to use the concepts and measures of attachment theory to understand how individual differences in attachment affect interactions between patients and therapists in group psychotherapy. This work built on the premise that humans often seek protection within social groups, in addition to one-on-one relationships with other individuals (e.g., Marmarosh, 2014). If this assumption is correct, patients’ expectations about attachment should be salient in group psychotherapy as much as in individual psychotherapy. Consistently with these assumptions, recent research has established that attachment-related variables predict group cohesion, therapeutic alliance, as well as treatment outcomes in group psychotherapy (Rosendahl, Alldredge, Burlingame, & Strauss, 2021).

Despite these compelling early findings, current attachment- informed research on group psychotherapy has one important limitation. Although presumably attachment differences influence the therapy process and outcome through patients’ interpersonal behaviour during group sessions, little is known about what specific interpersonal behaviours are associated with the different attachment classifications. Previous work with the Patient Attachment Coding System (PACS, Talia & Miller-Bottome, 2012/2021) described the interpersonal behaviour and discourse of speakers with different attachment classifications during individual psychotherapy (Talia, Miller- Bottome, & Daniel, 2017), and during interviews (Talia, Miller-Bottome, Lilliengren, Wyner, & Bate, 2019a). However, it is unclear whether these findings can be extended to the context of group psychotherapy.

This paper presents an investigation of how patients with different attachment classifications, as assigned by accredited coders, communicate in group psychotherapy. Because of the paucity of previous empirical research in this area, we conducted an exploratory analysis into the discourse characteristics that seem to typify these patients in session, which may inform future quantitative empirical work. Our work may represent a first step for theory-informed attempts to tailor group psychotherapy to the needs of patients with different attachment classifications.

Attachment and group psychotherapy: theory and research

Before becoming a popular framework for psychotherapy, attachment theory began as a theory of the development of close relationships and personality (Bowlby, 1969/1982). The core tenets of this theory can be encapsulated in two main assumptions. First, Bowlby hypothesized that one of the basic needs of the individual, in childhood as in adulthood, is to maintain an unbroken relationship with one or more persons who are stronger and wiser, called attachment figures. According to Bowlby, this need evolved in many species because maintaining proximity to a caregiver increases the likelihood that the infant will be protected from dangers. After infancy, many other strategies can be used to fulfil the need for protection and safety. For example, adults seek and maintain communicative contact with attachment figures in order to foster information exchange and formation of withingroup alliances (Tomasello, 2014).

The second key idea of attachment theory concerns what happens when the development of early relationships with attachment figures goes awry. Attachment theorists believe that infants who come to expect that their main caregivers will not adequately respond to their signals may later develop an expectation that all other significant persons will be insensitive to their needs. These expectations are believed to underpin insecure attachment, which can have an impact on how individuals engage in close relationships and regulate affect (see e.g., Cassidy & Shaver, 2016; Duschinsky, 2020).

These two ideas have inspired a prolific vein of research in psychotherapy informed by attachment theory. In his only systematic account of psychotherapy from the framework of attachment theory, Bowlby (1988) hypothesized that the therapist could become an attachment figure for the patient (i.e. a ‘secure base’), because the therapist is someone who typically attempts to provide closeness and safety. There is now a substantial body of research that supports a prospective association between differences in attachment-related expectations, as measured with assessments such as the AAI, and engagement in psychotherapy (see Slade, 2016). While this body of work includes measures of attachment ‘style’ by self-report, many of its findings are based on observational assessments of attachment-related individual differences in psychotherapy sessions (see e.g., Talia, et al. 2014).

Although Bowlby was convinced that attachment theory could be used as a framework for investigating and conducting group psychotherapy as well (see p. 137, Bowlby, 1988), in his writings he mainly considered individual psychotherapy, and to a lesser extent family therapy (see Bowlby, 1949). Following Bowlby’s suggestion, however, some pioneering researchers have in the past two decades begun to apply the basic assumptions of attachment theory to multiple caregivers and group contexts (Smith, Murphy, & Coats, 1999, Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007; Howes & Spieker, 2008).

It has been argued that our species could not have evolved unless other members of the social group helped with caring for the offspring, beyond mothers (Hrdy, 2009). Fonagy and colleagues’ recent emphasis on cultural transmission as a core function of attachment relationships (Fonagy, Allison, Campbell, & Luyten, 2017) may also suggest that various group contexts outside of dyadic relationships could be considered as ‘attachment-relevant’. On these grounds, a patient in group therapy may be expected to use the group therapist as a secure base, but also the therapy group as a whole (see, for example, Holtz, 2004; Keating et al., 2014; Marmarosh & Markin, 2007).

Individual differences in attachment-related expectations may influence the patient-therapist alliance, but also group cohesion, which is defined as the degree to which group members perceive connection and closeness to each other (Yalom & Leszcz, 2022). Secure attachment may help patients learn from new experiences with other group members, while insecure attachment could lead them to mistrust or misunderstand group members (Tasca, 2014). Attachment research has shown that patients’ attachment expectations influence group therapy outcomes (Marmarosh, 2019). Research explored the associations between attachment styles and group cohesion (Gullo, Lo Coco, Di Fratello, Giannone, Mannino, & Burlingame, 2015), and suggests that attachment should be considered when selecting members for a group (Kivlighan, Lo Coco, & Gullo, 2017). Finally, research has demonstrated that changes in the direction of greater attachment security is prospectively associated with therapy outcomes (Maxwell, et al. 2014).

In contrast with our knowledge base about how attachment- related differences influence therapy process and outcome in individual psychotherapy, less is known about the behaviours that may distinguish patients of different attachment classifications in therapeutic groups. A number of researches have investigated associations between group members’ attachment styles and process variables (Illing, Tasca, Balfour, & Bissada, 2011; Harel, Shechtman, & Cutrona, 2011; Rosendahl, et al., 2021, Tucker, Wade, Abraham, Bittman-Heinrichs, Cornish, & Post, 2020). Studies also showed that individuals with high levels of anxiety reported more positive relationship in group (Tasca, Balfour, Ritchie, & Bissada, 2007, Lo Coco, Gullo, Oieni, Giannone, Di Blasi, Kivlighan, 2015), while high levels of avoidance were associated with weaker quality of group relationships in both clinical and nonclinical populations (Tucker, et al., 2020).

No studies have explored associations between attachment differences and observable in-session behaviour in group psychotherapy. Despite their importance, most studies cited above were based on self-report questionnaires about patients’ perceptions of other group members or themselves. Other studies of this topic were based on observation (Korfmacher, Adam, Ogawa, & Egeland, 1997; Teti et al., 2008; Zegers, Schuengel, van Ijzendoorn, & Janssens, 2006), but drew from clinicians’ perceptions of clients’ conduct during long periods of frequent contact. Greater knowledge of the behaviours typical of patients of different attachment classifications during any given session may assist group therapists in tailoring treatments to their patients, making decisions about optimal group homogeneity when assembling groups, and targeting patients’ attachment characteristics with their interventions.

How adult attachment status influences the psychotherapy process

In the past decade, we have learnt much about what interactive processes and discourse characteristics tend to be linked with secure, dismissing, and preoccupied patients in individual psychotherapy (as well as, most recently, unresolved/ disorganized patients, Talia, et al., 2022). Although such research has not so far focused on group psychotherapy, knowledge of attachment-related differences in individual therapy may be salient in this paper. We thus briefly discuss this research in the following paragraphs.

In 2014, Talia and colleagues showed that patients’ AAI classifications may have distinctive manifestations in the psychotherapy process, which can be tracked by outside observers to predict patients’ attachment classification. Later, an observer-based measure based on this research, the Patient Attachment Coding System (PACS), was shown to predict patients’ independently obtained AAI classifications with an excellent degree of accuracy (k=0.82, Talia, et al., 2017), as well as their mentalizing (Talia, et al., 2018).

The PACS in-session markers of patients’ attachment were initially identified through a semi-inductive method made popular by attachment researchers: the guess-and-uncover method (Duschinsky, 2020; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1988). The main aim of this method is to identify observable individual differences associated with an external criterion, for example an individual’s attachment classification. In the first step of this method, attachment researchers make initial conjectures about the likely attachment classification of a sample of individuals whose behavior or discourse were observed in depth. These conjectures are informed by assumptions about how attachment may manifest in the context under study. As they conduct their observations, researchers record any element of participants’ behavior or discourse that they believe to be indicators of participants’ attachment classification.

In the second step, the researchers compare their initial guesses with independently-obtained information about participants’ attachment classifications. Any error in prediction becomes an occasion for developing the system. Indicators that lead researchers to incorrect classifications are eliminated or revised, whilst new indicators are gradually introduced. Researchers who use the guess-and-uncover method go through the above two steps in an iterative fashion, adapting their coding system to new samples in turn. Although this process may continue indefinitely, it can temporarily stop when it appears to have amassed a sufficient number of indicators to correctly classify new observations.

Indeed, in their subsequent empirical work, Talia and colleagues confirmed that patients of differing attachment classifications adopt distinct discourse styles, even when discussing topics beyond their parents or other attachment figures (Talia, et al., 2019a). According to their findings, dismissing patients tend to speak in a concise manner, relaying summaries and short explanations in place of narrative episodes and feelings. This way of speaking is usually clear, but it may often come across as lifeless and barren of affect. On the other hand, preoccupied patients tend to speak in ways that are more compelling, but they are less easy to follow, as they fill their discourse with direct quotations, long re-enactments of past episodes, and evocative but vague terms. Secure patients, finally, seem to maintain informativeness and clarity of discourse by a measured use of narratives, emotions, and reflections.

Talia and colleagues have proposed that such attachment- related differences in psychotherapy reflect generalized differences in communication that are independent of the topics discussed (Talia, et al., 2019a). In particular, Talia et al. (2019b) have proposed that attachment differences reflect individual differences in the ability to promote epistemic trust in listeners. Epistemic trust is defined as the unconscious expectation that interpersonal communication is useful and understandable (Fonagy & Allison, 2014; Schröder, Talia, Volkert, & Taubner, 2018).

Talia and colleagues have also suggested that these differences in epistemic trust may first emerge as an adaptation to early caregivers’ communication patterns (Talia et al., in review). Behavior in attachment relationships serves to maintain a certain degree of closeness and communication with the attachment figure (Bowlby, 1991; Granqvist, 2020). The child can thus be expected to adapt to the attachment figure’s communication preferences and degree of attention in order to maximize communication with them.

Recent research has shown that dismissing individuals keep their communication as simple as possible, minimizing any narrative detail, perhaps because they expect that their interlocutors will pay little attention to their communication overall. For this reason, they try to make comprehension less effortful. On the other hand, preoccupied individuals provide plenty of detail that may interest their listeners, but they also make their communication more difficult to understand. They may assume that their listeners will not pay attention consistently to them, and so they strive to compel listeners’ attention with copious information and repetition. Such expectations influence verbal communication regardless of the topics discussed in ways that can be identified during individual psychotherapy sessions with the PACS, but also in structured interviews (Talia, et al., 2019b). These expectations, moreover, seem to have an identifiable influence on the process of individual psychotherapy (Miller-Bottome, Talia, Eubanks- Carter, Safran, & Muran, 2019; Kleinbub, Talia, & Palmieri, 2020; Bekes, et al., 2021).

Despite the body of work demonstrating the influence of attachment classifications on individual psychotherapy processes, no observational research to date has examined how patients with different classifications speak and interact in group psychotherapy. It can be expected that discourse characteristics displayed in group psychotherapy by patients of different attachment classifications may resemble those that typify the same patients according to the PACS. However, processes unique to groups, such as dynamic turn-taking between multiple speakers and the complexities of interpersonal interaction between several people, might substantially alter the way in which attachment- related differences emerge in groups (see e.g., Markin & Marmarosh, 2010). This may be particularly obvious if attachment-related differences are conceptualized as differences in expectations about communication. In a group, every individual is exposed to multiple sources of information, and they must promote the trust of many listeners at the same time. Exploratory research is needed to account for how patients of different attachment classifications speak in group psychotherapy, and to inform the adaptation of the PACS to the group therapy context.

Methods

This study analysed treatment data from the BMBFfunded project ‘Understanding and Breaking the Intergenerational Cycle of Abuse’ (UBICA-II). The project is devoted to providing help for parents currently in psychiatric treatment with a high risk of abusing their child (Neukel, et al., 2021). UBICA-II comprises a multicentric randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of a mentalization- based parenting intervention, the Lighthouse Parenting Intervention (LPI, Byrne et al., 2019). Before the start of the RCT, pilot groups were conducted in two different psychiatric hospitals in the North and the South of Germany as part of therapists’ training to deliver the intervention. The current paper presents an analysis of these pilot group sessions. Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty, University Hospital Heidelberg (S- 115/2019). All patients have given their consent for their anonymized data to be used for research.

Participants

In this study, we analysed transcripts of three therapy groups, which comprised 12 patients altogether (see Table 1). Patients were recruited in this project if they were parents of a child who was 15 or younger, and if they had regular contact with this child. Participation was voluntary, and patients had to be currently admitted to inpatient psychiatric care in one of the treatment centres involved in UBICA-II. Participants had a range of different diagnoses, including mood and psychotic disorders, and 85% of them were female. Participant age ranged between 25 and 45.

Each group was led by one experienced therapist and co-led by a variable number of co-therapists (from one to three), which differed between different group sessions. The total number of therapists and co-therapists was eleven. Though unusual, this setting was a consequence of the need to train the co-therapists in the context of the prospective, larger study. The co-therapists also saw patients in individual sessions. All therapists were female except two.

Measures

Before the first group therapy session, all patients were interviewed with one of two validated interview measures of attachment. Because the sessions analysed in this study were part of a pilot intervention that served to prepare for a subsequent psychotherapy trial, some aspects of the research design underwent variations as recruitment went along. In particular, whilst patients in group C were administered the AAI, the patients in the other two groups were administered the Parent Development Interview (PDI). Though similar in its overall structure to the AAI, the PDI focuses on discussing the speaker’s representations and feelings about their child, rather than about their parents. It was decided after the beginning of the project that the PDI was more appropriate than the AAI for preparing the clinical work anticipated with these patients. In the context of the present study, even if it would have been ideal to use the same interview for obtaining patients’ attachment classifications, we considered both interviews in order to be able to analyse the data that had already been collected with our group participants.

Adult Attachment interview (AAI): The Adult Attachment Interview is an hour-long semi-structured interview for adults (George et al., 1985). Participants are interviewed about early childhood memories about their primary caregivers, separations, losses, and other adverse experiences, which they are then asked to exemplify with specific memories. The interview elicits the speaker’s representations of attachment and rates their narrative coherence during their recall. A trained coder rates the transcript with the AAI coding scales, among which the most important are: ‘Coherence of transcript/mind’; ‘Idealization of parent’; ‘Lack of memory’; ‘Involving anger’; and ‘Passivity of discourse’. From the rating of these scales, a coder assigns one of four main attachment classifications: Secure-autonomous (when the Coherence scale is high and the other low), dismissing (when ‘Idealization of parent’ and/or ‘Lack of memory’ are high), preoccupied (when ‘Involving anger’ and ‘Passivity of discourse’ are high), or unresolved. Given that the PACS currently only has classifications that correspond to the first three main AAI classifications, we did not consider this last category and used a forced three-way classification in all analyses.

Table 1.

Composition of the groups and attachment classifications.

| Group | Dismissing | Preoccupied |

|---|---|---|

| A | Elisabeth | Amy |

| B | Julia | Marc, Tim, Sara, Eva |

| C | Hannah, Anne, Marie | Claudia, Sophie |

Parent Development Interview (PDI): The Parent Development Interview is a semi-structured interview for adults (Slade et al., 2004). It consists of 45 questions that inquire about parents’ representation of their children, of themselves as parents, and of their relationship with their children. Parents are instructed to focus on the relationship with one child. Similar to questions in the AAI, participants are asked to illustrate their answers with specific memories.

Though the PDI is most often used to assess Reflective Functioning (Slade, 2005), in this study we used it to classify speakers’ state of mind with respect to attachment as secure-autonomous, dismissing, or preoccupied. With this aim, we coded the PDI verbatim transcripts with an adaptation of the AAI coding scales. In our coding, high ratings on the AAI Coherence scale would lead to a secure attachment classification, high ratings on the AAI Idealization scale and/or the AAI Lack of memory scale would lead to a dismissing attachment classification, and high ratings on the AAI Involving anger and/or the AAI Passivity scale would lead to a preoccupied attachment classification. Because the PDI does not contain sufficient prompts for coding unresolved/disorganised attachment, we did not attempt to assign this classification. However, given the focus of this paper on the main organized classifications, we did not perceive this to be a limitation.

Although it has no specific precedent, our application of the AAI scales to the PDI rests on specific conceptual and empirical foundations. Even if the AAI is sometimes referred to as a measure of ‘attachment representations’, the central aim of the coding system developed by Main, Goldwyn and Hesse is that of assessing speakers’ ability to attend to and communicate about attachment-relevant experiences and the feelings they evoke. Therefore, although the AAI coding system has been validated specifically in relation to the AAI protocol developed by George, Kaplan, & Cassidy, it seems theoretically applicable as well to other interviews that focus on other attachment relationships, such as the PDI. In the past, slight adaptations of the AAI Coherence scale and other AAI scales have been successful used for coding interviews about romantic partners (Treboux, Crowell, & Waters, 2004), therapists (Diamond, Stovall-McClough, Clarkin, & Levy, 2003; Talia, et al., 2019a), and children, including the PDI (Henderson, Steele, & Hilmann, 2007).

In this project, all AAI and PDI interviews were classified by a trained AAI coder. Five patients (41.7%) were classified as dismissing and seven (58.3%) as preoccupied, with either the AAI or PDI. Every therapy group included at least one individual of each classification. Distribution of attachment classifications is presented in Table 2. No individual was classified as secure, which was not unexpected given the high-risk nature of the sample (see Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2009).

Patient Attachment Coding System (PACS): Our analysis of the session transcripts was informed by the PACS. As previously mentioned, the PACS measures insession attachment based on a verbatim transcript of a psychotherapy session. It is coded without segmenting the transcript into parts. Coders assign markers as they occur and then assign a rating from one to seven (with 0.5 increments) on five main scales, based on the frequency of the respective markers: Proximity seeking; Contact maintaining; Exploring; Avoidance, and Resistance. These ratings generate a global Security score and a classification into one of three attachment categories: secure, dismissing, or preoccupied. Psychometric properties of the PACS have been assessed in a validation study in multiple therapy settings (N=160, Talia et al., 2017). The three main attachment classifications showed excellent convergent validity with the main AAI classifications (87% correspondence, κ=0.81, P<0.001).

Treatments

The treatment analysed in this study, the ‘Lighthouse- Parenting Program’ (LPP), is a manualized mentalizationbased intervention for parents at high risk of abusing their children (Byrne et al., 2019). The program is designed to enhance parents’ mentalizing, that is, the capacity to be curious about the child’s inner world and to reflect on the child’s thoughts and feelings, as well as one’s own, in relation to the child (Byrne et al., 2018). The LPP consists of group sessions and individual sessions for each parent. Each group session includes psychoeducation and more experiential elements, during which parents are asked to share and reflect on their difficulties and successes. Metaphors and artistic drawings about attachment and mentalization are used throughout the sessions as a vehicle for collaborative discussion. For example, the therapist describes the parents as ‘lighthouses’ that illuminate their child’s minds and offer a ‘safe harbour’ (secure attachment) in moments of distress (‘rough seas’).

Here, an adapted version of the LPP, LPP-psychiatry (Volkert et al., 2019) was administered as a part of the UBICA-II project. The LPP-psychiatry is a 12-hour manualized program offered within 5 weeks of hospital treatment with standard clinical care, and it comprises five 75-minute group sessions and five 50-minute individual sessions, as well as two additional sessions of ‘social counselling’ (Taubner et al., 2019). The treatment was provided by trained psychotherapists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses, who during the project pilot sessions had received a 2.5-day training in LPP and MBT by expert clinicians. All sessions were video recorded for training and supervision purposes.

Procedure

All available video-recorded group sessions were transcribed verbatim by a research assistant (N=14). For two of the groups, all five sessions were available, while for the remaining group only four were available, due to a failure in the recording equipment. The videos transcribed in this sample lasted between 36 and 86 minutes (average: 65 minutes). One session lasted longer than 86 minutes, but only part of it was available on recording.

Table 2.

Summary of observed attachment-related differences in groups.

| Preoccupied | Dismissing | |

|---|---|---|

| Differences in the content and form of communication | Frequently proposed discussions of values and ‘rules of life’ in a one-sided manner, whilst enlisting other patients’ point of view Preoccupied patients narrated specific events, often to supply positive instances of their behaviour as parents |

When proposing values or ‘rules of life’, their claims had a tentative tone and/or expressed doubt Dismissive patients rarely described specific examples of their interpersonal experiences, even when directly probed |

| Differences in how patients refer to what other fellow patients said | Preoccupied patients often agreed with the previous speaker only to change attitude or topic immediately afterwards Preoccupied patients were often covertly critical of others’ statements |

Dismissing patients closely linked their statements to the previous patient’s statement and/or point of view Dismissing patients often downplayed other patients’ previous negative statements by actively adding a ‘positive wrap-up’ |

| Differences in how patients ‘take the floor’ | Preoccupied patients had the tendency to be more proactive in turn taking by: i) by commenting on the utterances of others and then shifting the topic to their own experiences; ii) by answering therapists’ and co-therapist’s exploratory questions directed to the group; iii) by posing questions to the therapist or the group and then take the floor when further responding to their reply |

Dismissing patients had the tendency to be less proactive in turn taking by: i) by commenting on the utterances of others and then terminating their speech turn before shifting the topic; ii) by answering therapists’ and co-therapist’s questions only when directed to them |

The sessions were analysed by the first and the third author using the ‘guess-and-uncover’ semi-inductive method in combination with the PACS. At the beginning, the four available transcripts for group C were coded with the PACS, and an attachment classification was obtained for each patient by coding all individual speech turns for that patient (i.e. ‘guess’). At this stage, coders were blind to patients’ AAI classification.

Next, the PACS classifications of the patients obtained in this way were compared with the independently obtained AAI classification of each patient (‘uncover’). Every time that the coders were not able to guess the AAI classification of the patient correctly, they adapted the underlying coding system in order to maximize matching. Beyond the content of patients’ discourse, other characteristics of group interaction were scrutinized: the frequency and length of speech turns, the tendency to interrupt other speakers, turn-taking and patient-to-patient interaction in general. After group C, the same semi-inductive method of analysis was applied first to group A and then to group B.

Here, we report discourse characteristics that at the end of our analyses appeared to be associated with dismissing and preoccupied attachment classifications. We will group our observations according to three sets of differences in how patients foster their listener’s epistemic trust: differences in the content and form of communication; differences in how patients link their communications with previous communications of other patients; and differences in how patients took the initiative to speak in front of the rest of the group.

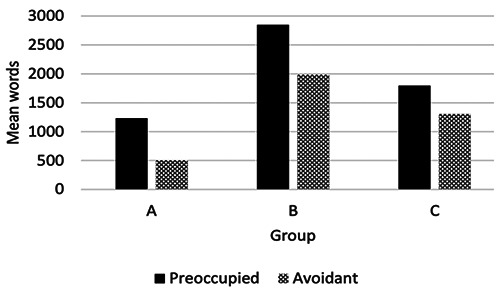

Before we present the specific results of our analysis, some general differences in the length and frequency of dismissing and preoccupied patients’ speech turns warrant further discussion. Dismissing patients seemed to speak less than their preoccupied counterparts and they initiated new speech turns less frequently. The first trend is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows that dismissing patients only uttered 63% of the words uttered by preoccupied patients. Moreover, in the sessions analysed, dismissing patients initiated on average only 16.6 speech turns that were longer than one single sentence, against the 35.0 multisentence speech turns of their preoccupied counterparts.

Figure 1.

Average words per session per patient, by therapy group and by Adult Attachment Interview classification.

Results

Differences in the content and form of communication

Many aspects of the discourse of dismissing and preoccupied patients in group psychotherapy were the same as those previously identified with the PACS in an individual therapy context. For example, similar to their counterparts in individual psychotherapy, preoccupied patients in group psychotherapy also re-enacted interpersonal episodes using direct discourse, as if these were occurring in the present, and they often used vague terms, whilst dismissing patients were terse and rarely mentioned their internal states. Further, patients in both groups did not tend to disclose their vulnerability openly (as rated by the PACS Proximity seeking scale) or reflect on others’ mental states (as rated by the PACS Exploring scale), both of which are characteristics of secure patients in individual psychotherapy. In the following, we will focus on the new markers that emerged as specific to the group therapy context. For more information about the markers of attachment originally identified in the context of individual therapy the interested reader is referred to Talia, et al., 2017.

Contrary to what has been observed in individual psychotherapy (Talia, et al., 2017), in the sessions we analysed, differences in the discourse of preoccupied and dismissing patients in group psychotherapy seemed to be more striking when patients talked about topics of general interest, rather than personal experiences. Among such topics presented to the group were theories about how society should work, how people should behave, or what strategies should be adopted by parents raising their children.

Strikingly, values and rules of life were frequently proposed for discussion by preoccupied patients, but rarely, if at all, by dismissing patients. In particular, in these discussions preoccupied patients were one-sided and seemed to affect certainty and objectiveness. They did not limit the truth of their claims by using a tentative tone or expressing doubt (e.g., they did not introduce them with ‘I think’, ‘perhaps’, etc.), nor did they mention any relevant feelings or emotions. Further, these patients often interspersed their discourse by enlisting other patients’ point of view (‘I’m sure you agree with me’) or other people’s.

For example, compare what Sophie (preoccupied) and Hannah (dismissing) say in their first group session:

Sophie: You gotta teach your children not to interrupt, you know what I mean, if I’m talking to someone, please don’t interrupt me. Wait until I’m done and then I’ll talk to you. Yes, and with a nine-yearold child it’s certainly something important that you gotta do.

[...]

Hannah: I think it’s good to have your mummy there when you need her, but too much is maybe...I don’t know…too much is too much (chuckles), yeah.

Further, in the group sessions we analysed, such general theories and value systems were supported by patients through supplying (positive) instances of their own behaviour; but only among preoccupied patients. For example, in the fourth group session, Eva (preoccupied) shifts without segue from stating a positive evaluation of her own behaviour as a mother, to reporting an incomplete episode with her child that challenged her self-doubts about her parenting, to invoking her husband’s approval of her behaviour:

I have an older daughter and she is 5. And in spite of everything, I’ve been actually trying so hard when she was younger to give her the feeling that I’ll come back, that I’ll never leave her and I’ll always come back and be with her. And I have been totally convinced that I have managed it. That I have mastered this art, you know? That my child trusts that mommy will come again. But last time you [pointing to the therapist] managed to confuse me (chuckles), and I had a big question mark about this when I got out of here a week ago. But I was able to reassure myself by saying ‘I just know I did right by her’. Last week she was crying once when I left. She wanted me, so to speak. I mean now that she’s grown up, of course, you gotta explain things to her. She doesn’t just stop crying, you have to explain it to her, why, why. And so I did that. It upset me, but I was able to reassure myself again and also talk to my husband and he gave me confirmation, so to speak, that we both acted correctly. And especially me as a mother.

On the other hand, dismissing patients rarely described specific examples of their interpersonal experiences. When directly probed, they often avoided responding to the queries, as Anne and Marie do in the following excerpt, taken from the third group session:

Anne: I see my own anger in other people and then I think they’re, they’re annoyed with me, even though it’s not true.

T: Mh-hmm. Yeah, can you think of an example? Even if it’s not related to your child. Could be an example of something that happened with your partner.

Anne: (pause 5 sec) That’s all that comes to my mind now.... Mm... Maybe it’ll come later. T. Mh-hmm.

Marie: I find it difficult... Do they have to be concrete situations like that, or...?

Before closing this section, we should mention another peculiarity of dismissing and preoccupied individuals in the context of group psychotherapy, as compared to their observed discourse behaviour in individual psychotherapy. In individual psychotherapy, there are a set of markers coded under the PACS Contact Maintaining scale that are characteristic of secure patients and relatively rare in their insecure counterparts. These include instances when the patient thanks the therapist, disclose positive emotions about the therapy, affirm the therapist’s interventions, or describes experiencing the impact of the therapy. In our observations of group psychotherapy, these markers frequently appeared in the discourse of dismissing and preoccupied patients as well. Although the explanation for this observation is not yet clear, we can speculate that insecure patients may find it easier to use these markers because they may feel ‘backed up’ by the other patients in the room. At this stage, this observation suggests that the PACS Contact maintaining scale should not be used when applying the PACS to code group psychotherapy, and that future studies should investigate this phenomenon.

Differences in how patients refer to fellow patients’ remarks

In group psychotherapy, every statement made by a patient can be understood as an indirect reply to previous statements by other patients (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020). Each new sentence is an argument in favour of others’ claims or against them, an accompaniment or a counterpoint, an attempt to shed light on what was said or to obscure it, and so on. This is relevant to our discussion of attachment-related differences in patients’ behaviour in group sessions in two ways.

First, our analyses identified differences in how patients took an explicit stance with respect to previous remarks made by other patients. After a patient’s statement, other patients might feel involved and called upon to express their agreement or disagreement with it. They may feel that, if they do not speak up, their silence could be interpreted as assent or denial.

In this respect, dismissing patients often downplayed other patients’ previous negative statements, as if they actively tried to add a ‘positive wrap-up’ to them. The following excerpt is taken from a group discussion of a series of drawings that were shown to the group by the main therapist during session two. Here, Claudia (preoccupied), tells the therapist that she does not like the images:

Claudia: I think you’ve put many negative images on the screen right now and I don’t like that. The only nice one, I think, is the one with people playing at the beach and hanging out together. But even that one, the one with mermaids, that’s so ambivalent, do you know what I mean?

At this point, Hannah and Anne, both classified as dismissing on the AAI, intervened and corrected Claudia’s remarks:

Hannah: But the picture on top, in the top right corner, is also/

Anne: Looks like a family trip.

Hannah: On an adventure, a positive one.

Hannah: The sea is also very calm. And the seagull above looks rather idyllic, at least in my perspective. Hannah: The pirate ship need not be something negative. (pause 5 second) (chuckles). I mean I don’t know what this image here is supposed to represent, but I am not necessarily seeing it as negative.

Second, we found that patients’ attachment classifications were associated with how their utterances implicitly related to the previous utterance made by another patient. Dismissing speakers, whenever they were not responding to a direct question of the therapist, seemed to limit themselves to reflecting back the previous patient’s remark, without introducing any new material. They started by saying that they agreed or disagreed with what another patient had said, or at least acknowledged their fellow patients’ remark with a ‘yeah’, and then proceeded to explain their point of view. On the other hand, preoccupied patients made links with previous utterances made by fellow patients that were much more tenuous. These patients often agreed with the previous speaker or repeated back one single element of their comment, only to change attitude or topic immediately afterwards, for example by starting to speak about an unrelated experience of theirs. See for example how Amy (coded as preoccupied) reacts to Elisabeth’s (coded as dismissing) previous intervention, during the last session:

Elisabeth: When we were on holiday with the whole family, everything was problem-free, and it was nice. That’s what I try to do for my son, those are also the moments when I see that he really feels good and doesn’t think too much. That he can just let go.

Amy: Uhm, yeah, I also want to give Johanna the feeling that she can trust me and that I’m always a rock. That I am always there for her and would always give everything for her. Definitely, so really being the ‘rock in the storm’, that’s really.... That she always knows she can rely on her mum to be strong for her. So everything that my mother practically didn’t do for me.

Preoccupied patients were also often covertly critical of others’ statements. For instance, without explicitly stating their disagreement, they presented theories or value systems that appeared to oppose the views implied in other patients’ comments. The following two examples exemplify this tendency (and present another example of the tendency of these patients to propose ‘rules of life’ with a ring of authority). In the second session, after Elisabeth had stated that she did not cuddle her children as often anymore because they had now grown up, Amy said:

Amy: A mum can always cuddle, especially her own children, regardless of their age. You know what I mean? I always cuddle my child, it doesn’t matter if she has her own room or she hasn’t.

In their fourth session, after Marc reported letting his children go to school alone, Sara (coded as preoccupied) said:

Sara: With my child, I would always…it doesn’t matter if he’s nine or eleven … I would always make sure that he doesn’t go to school alone. Even if it’s only walking together with a friend, yeah, or something like that. Let me say this, it just isn’t like it used to be thirty years ago anymore.

Differences in how patients ‘take the floor’

In a group, when a patient takes the initiative to speak to the rest of the group, they indirectly prevent other patients from doing so, and for as long as they continue speaking. Thus, this behavior in the group context can be understood as a meaningful interpersonal gesture.

In our observations, preoccupied patients in this sample tended to initiate sharing in front of the group far more than their dismissing counterparts. This took several different forms. First, as we discussed above, preoccupied patients often took the floor by cursorily commenting on the utterances of others and then shifting the topic to an unrelated experience of theirs. Second, in all three groups, preoccupied patients were most often the first to answer therapists’ exploratory questions directed to the whole group. In group B, open questions were mostly answered by Tim and Eva, whilst in group C they were mostly answered by Claudia and Sophie, each of whom were classified as preoccupied. Dismissing patients mostly answered questions that were directed at them specifically. Strikingly, Julia, a dismissing patient in group B, only seemed to speak when directly probed.

Finally, preoccupied patients also seemed to tactically pose questions to the therapist or the group which they would then answer, as though the question was posed to provide an opportunity to expound on a topic already held in mind. In the following example, taken from the first group session in treatment, the therapist proposes for discussion a fictional example with a mother and her son. The focus of the story revolves around conflicts that can arise between children and parents when both are stressed and mentalizing fails. In a seemingly unrelated fashion, Sophie (preoccupied) asks a general question that appeared to serve as a segue into a complaint about her husband and a re-enactment of the conflict in front of the group:

Sophie: I have a question. Can women mentalize better than men?

T: Well, we don’t know for sure. But men need to mentalize too.

Sophie: I often experience that my husband is like ‘Oh, our son is sulky again.’ Or ‘Oh, he is whining again.’ Where I think: ‘Yeah, but why is he crying or what happened?’ I want to know, I want to see, is that really, well, is he whining or is that real? Is he hurt? He has a need, he wants to eat, or I don’t know, yeah. ‘Oh, just let him be.’ Or, well I think no, it doesn’t work that way, there is more to it than just saying something like that.

Discussion

In this article, we reported a semi-inductive analysis of the discourse characteristics that typify dismissing and preoccupied patients in group psychotherapy sessions. Specifically, we discussed differences in the content and form of patients’ communication, how they reacted to other patients’ communication, and in how they ‘took the floor’. We also highlighted differences in the length and frequency of patients’ speech turn and advanced some hypotheses about the mechanisms underpinning such differences.

Our observations seem to support and extend the idea that adult attachment classifications reflect differences in epistemic trust (Talia, et al., 2019b). In a group, each individual is exposed to multiple sources of information and must promote the trust of many listeners at once. As in individual therapy, preoccupied patients seem to strive to maintain their listeners’ attention and trust by increasing the amount of potentially useful information conveyed as well as their commitment to the points of view they express. Dismissing patients, on the other hand, try to communicate in a more economical manner and try not to give the impression of exaggerating any claims.

While in individual psychotherapy these differences are most evident when patients talk about personal experiences, in our analyses we observed these characteristics primarily during discussion of topics of general interest. This may be because, in structured therapy groups like those analysed in this study, topics of general interest such as broad theories about development or parenting practices may be more immediately interesting to participants, compared to personal anecdotes. If attachment-related differences reflect differences in how patients foster epistemic trust in the relevance of what they say (see Talia, et al., 2019), these may be most recognizable when patients discuss topics that are potentially interesting to listeners.

These considerations appear particularly relevant also considering that groups included in this study were very brief. It is known that the initial sessions of a group are crucial in the process of forming group cohesion (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020). In this early stage, the group attempts to find common themes for discussion and to foster a sense of collective belonging. Only when some measure of group cohesion is established may patients feel safe enough to bring more personal issues to the group. However, while keeping these considerations in mind, our results seem to indicate that patients with different attachment classifications show marked differences in the way they discuss even general issues.

Our study was limited in several ways. First, our sample did not include any speakers who were classified as secure. Even if these patients may be rare in clinical contexts (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2009) including them in future studies of group psychotherapy may better clarify what mechanisms underpin the differences in communication discussed in this article. For example, on the basis of this study, it remains unclear whether the observed absence of positive instances of mentalizing (coded with the PACS Exploring scale) was a function of the absence of secure patients in our sample, or of the group setting. Similarly, our study did not consider speakers classified as unresolved/disorganized. This is because, until recently (Talia, et al. 2022), there have been no empirical means of identifying markers of this attachment classification in psychotherapy. Future studies should consider this attachment classification as well. Furthermore, given that we only considered one short-term, small group treatment, it is possible that some of the manifestations of attachment classifications we observed are specific to the treatment considered. In particular, it is important to test whether other markers of the different attachment classifications emerge when analysing groups that are not manualized or structured, like LPP is, and in which psychoeducation is less of a focus.

Secondly, our data came from a pilot study, the parameters of which underwent changes as the study went along, in order to optimize how the intervention was administered. For example, the number of participants in the three groups varied, as did the number of therapists. The attachment assessment instruments administered to the patients before the beginning of the groups changed from the AAI to the PDI. However, although this lack of uniformity could be viewed as a limitation in the case of a traditional hypothesis-testing study, it allowed us to explore different settings and conditions, thereby potentially making our hypotheses more relevant for future tests in a broader range of contexts.

Third, one of the three groups we considered only included two patients, and could thus hardly be considered to be representative of group psychotherapy as a treatment. However, we resolved to analyse the sessions of this group together with the others on the following grounds. Previous research with the PACS has tended to focus on discourse characteristics that, at least in theory, are expected to characterize patients even outside of psychotherapy. For example, they have been identified in post-treatment interviews (Talia, et al., 2019), and Talia et al. (in press) have suggested that they reflect generalized styles of communication. Drawing from this research, our aim in this paper was to analyse how attachment-related differences influence discourse therapy groups as a local instance of discourse in groups more generally. This perspective is entirely consistent with the view of therapy groups as ‘social microcosms’, proposed for example by Yalom and Leszcz, which also forms the basis of attachment-informed group psychotherapy research (see e.g., Mallinckrodt & Chen, 2004). Analysing patients in our group A is informative from this perspective, especially because this group was conducted by a therapist and two to three co-therapists, and thus at any given time there were five or six people in the room.

A final limitation of this study is that its semi-inductive method does not allow us to reach firm conclusions about the generalizability of our findings. In other words, because in our study we were only partially blind to patient attachment classifications, it is still unclear the extent to which the characteristics we identified in the discourse of dismissing and preoccupied patients could be reliably tracked in other samples. Thus, our observations require independent validation and elaboration in future research.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study provides the first account based on observation of how attachment classifications influence interpersonal behaviour and communication in group psychotherapy. This is a first necessary step for future empirical investigation of how attachment manifests in group psychotherapy, and for using the PACS for classifying patients’ attachment in group contexts. For example, our findings suggest that the PACS Contact maintaining scale may have a different meaning in group psychotherapy, and we have discussed several potential additional markers of patient attachment classifications in groups, including differences in how patients refer to other fellow patients’ remarks, and how they initiate sharing. A version of the PACS adapted for groups could provide a window into patients’ interpersonal behaviour in group psychotherapy. This knowledge could inspire new hypotheses about how attachment impacts the process and outcome of therapy groups, and it may inform therapists’ decisions when selecting patients for therapy groups and tailoring group interventions to patients’ attachment classifications.

Attachment theory emerged as a theory of dyadic relationships. As the theory developed, several questions have arisen concerning how early relationships influence a broad set of later social outcomes, including interaction with larger social groups. Up until now, there has been little observational work examining how attachment classifications affect how individuals behave in groups. Further research on the influence of attachment classifications on group psychotherapy can expand our knowledge of psychotherapeutic treatments and, more broadly, our understanding of attachment in general and lifespan development.

Funding Statement

Funding: this work was supported by the International Psychoanalytic Association (Grant number 055) and by the BMBF-funded project ‘Understanding and Breaking the Intergenerational Cycle of Abuse’ (UBICA II: 01KR1803B; 01KR1803C).

References

- Bakermans-Kranenburg M. J., van IJzendoorn M. H. (2009). The first 10,000 Adult Attachment Interviews: Distributions of adult attachment representations in clinical and non-clinical groups. Attachment & Human Development, 11(3), 223-263. doi:10.1080/14616730902814762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Aafjes-van Doorn K., Spina D., Talia A., Starrs C., Perry J. (2021). The Relationship Between Defense Mechanisms and Attachment as Measured by Observer- Rated Methods in a Sample of Depressed Patients: A Pilot Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1949). The study and reduction of group tensions in the family. Human Relations, 2, 123-128. doi:10.1177/ 001872674900200203. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol 1. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1991). Ethological light on psychoanalytical problems. In Bateson P. (Ed.), The development and integration of behaviour: Essays in honour of Robert Hinde (pp. 301-313). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G., Sleed M., Midgley N., Fearon P., Mein C., Bateman A., Fonagy P. (2019). Lighthouse Parenting Programme: Description and pilot evaluation of mentalizationbased treatment to address child maltreatment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(4), 680-693. doi: 10.1177/1359104518807741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, Shaver P. R. (Ed.), Handbook of attachment (3rd ed., pp. 759-779). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duschinsky R. (2020) Cornerstones of Attachment Research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Allison E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 372-380. doi:10.1037/a0036505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P. (2021). Attachment, culture, and gene-culture coevolution: expanding the evolutionary toolbox of attachment theory. Attachment & Human Development, 23(1), 90-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo S., Lo Coco G. L., Di Fratello C., Giannone F., Mannino G., Burlingame G. (2015). Group climate, cohesion and curative climate: A study on the common factors in group process and their relation with members attachment dimensions. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 18(1), 10-20. doi:10.4081/ripppo.2015.160. [Google Scholar]

- Harel Y., Shechtman Z., Cutrona C. (2011). Individual and group process variables that affect social support in counseling groups. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15(4), 297. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz A. (2004). Measuring the therapy group attachment in group psychotherapy: A validation of the Social Group Attachment Scale [Dissertation, Psychology]. The Catholic University of America. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C., Spieker S. (2008). Attachment relationships in the context of multiple caregivers. In Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 317-332). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Illing V., Tasca G. A., Balfour L., Bissada H. (2011). Attachment dimensions and group climate growth in a sample of women seeking treatment for eating disorders. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 74(3), 255-269. doi:10.1521/psyc.2011.74.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating L., Tasca G. A., Gick M., Ritchie K., Balfour L., Bissada H. (2014). Change in attachment to the therapy group generalizes to change in individual attachment among women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy, 51(1), 78-87. doi:10.1037/a0031099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco G., Gullo S., Oieni V., Giannone F., Di Blasi M., Kivlighan D. M. (2016). The relationship between attachment dimensions and perceptions of group relationships over time: An actor-partner interdependence analysis. Group Dynamic Theory Research Practice, 20(4), 276-293. doi:10.1037/gdn0000056. [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan D. M., Lo Coco G., Gullo S., Pazzagli C., Mazzeschi C. (2017). Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance: members’ attachment fit with their group and group relationships. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 67, 223-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbub J. R., Talia A., Palmieri A. (2020). Physiological synchronization in the clinical process: A research primer. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(4), 420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfmacher J., Adam E., Ogawa J., Egeland B. (1997). Adult Attachment: Implications for the therapeutic process in a home visitation intervention. Applied Developmental Science, 1(1), 43-52. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0101_5. [Google Scholar]

- Main M., Cassidy J. (1988). Categories of response to reunion with the parent at age 6: Predictable from infant attachment classifications and stable over a 1-month period. Developmental Psychology, 24(3), 415-426. doi:10.1037/ 0012-1649.24.3.415. [Google Scholar]

- Main M., Kaplan N., Cassidy J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1/2), 66-104. doi:10.2307/3333827. [Google Scholar]

- Markin R. D., Marmarosh C. (2010). Application of adult attachment theory to group member transference and the group therapy process. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(1), 111-121. doi:10.1037/a0018840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh. C. L. (2017). Attachment in group psychotherapy: bridging theories, research, and clinical techniques. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 67, 157-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh C. L. (2014). Empirical research on attachment in group psychotherapy: Moving the field forward. Psychotherapy, 51(1), 88-92. doi:10.1037/a0032523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh C. L. (Ed., 2019). Attachment in Group Psychotherapy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh C. L., Markin R. D. (2007). Group and personal attachments: Two is better than one when predicting college adjustment. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 11(3), 153-164. doi:10.1037/1089-2699.11.3.153. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone M. (2014). Attachment and interaction: From Bowlby to current clinical theory and practice (2nd ed.). Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell H., Tasca G. A., Ritchie K., Balfour L., Bissada H. (2014). Change in attachment insecurity is related to improved outcomes 1-year post group therapy in women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy, 51(1), 57-65. doi:10. 1037/a0031100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood. Structure, dynamics and changes. New York, London: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Bottome M., Talia A., Eubanks C. F., Safran J. D., Muran J. C. (2019). Secure in-session attachment predicts rupture resolution: Negotiating a secure base. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 36(2), 132-138. doi:10.1037/pap0000232. [Google Scholar]

- Neukel C., Bermpohl F., Kaess M., Taubner S., Boedeker K., Williams K., Herpertz S. C. (2021). Understanding and breaking the intergenerational cycle of abuse in families enrolled in routine mental health services: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial and two non-interventional trials investigating mechanisms of change within the UBICA II consortium. Trials, 22(1), 1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks C. D., Tasca G. A. (Eds.). (2021). The psychology of groups: The intersection of social psychology and psychotherapy research. American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/0000201-000. [Google Scholar]

- Rosendahl J., Alldredge C. T., Burlingame G. M., Strauss B. (2021). Recent developments in group psychotherapy research. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 74(2), 52-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder-Pfeifer P., Talia A., Volkert J., Taubner S. (2018). Developing an assessment of epistemic trust: a research protocol. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 21(3), 330. doi:10.4081/ripppo.2018.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 269-281. doi:10.1080/14616730500245906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. (2016). The implications of attachment theory and research for adult psychotherapy research and practice. In Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Ed.), Handbook of attachment (3rd ed., pp. 759-779). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A., Grienenberger J. F., Bernbach E., Levy D., Locker A. (2005). Maternal reflective functioning, attachment, and the transmission gap: A preliminary study. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 283-298. doi:10.1080/ 14616730500245880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E.R., Murphy J., Coats S. (1999). Attachment to groups: theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1), 94-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Daniel S. I., Miller-Bottome M., Brambilla D., Miccoli D., Safran J. D., Lingiardi V. (2014). AAI predicts patients’ in-session interpersonal behavior and discourse: A ‘move to the level of the relation’ for attachment-informed psychotherapy research. Attachment & Human Development, 16(2), 192-209. doi:10.1080/14616734.2013.859161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Duschinsky R., Mazzarella D., Hauschild S., Taubner S. (2021). Epistemic Trust and the Emergence of Conduct Problems: Aggression in the Service of Communication. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Miller-Bottome M., Daniel S. I. (2017). Assessing attachment in psychotherapy: Validation of the patient attachment coding system (PACS). Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 149-161. doi:10.1002/cpp.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Miller-Bottome M., Katznelson H., Pedersen S. H., Steele H., Schröder P., Origlieri A., Scharff F. B., Giovanardi G., Andersson M., Lingiardi V., Safran J. D., Lunn S., Poulsen S., Taubner S. (2019a). Mentalizing in the presence of another: Measuring reflective functioning and attachment in the therapy process. Psychotherapy Research, 29(5), 652-665. doi:10.1080/10503307.2017.1417651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Muzi L., Lingiardi V., Taubner S. (2020). How to be a secure base: Therapists’ attachment representations and their link to attunement in psychotherapy. Attachment & Human Development, 22(2), 189-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Miller-Bottome M., Wyner R., Lilliengren P., Bate J. (2019a). Patients’ Adult Attachment Interview classification and their experience of the therapeutic relationship: Are they associated? Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 22(2), 361. doi:10.4081/ripppo.2019.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Taubner S., Miller-Bottome M. (2019b). Advances in attachment-informed psychotherapy practice. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 22(2), 405. doi:10.4081/ripppo.2019.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Taubner S., Miller-Bottome M., Muurholm S. D., Winther A., Frandsen F. W., Duschinsky R. (2022). The in-session discourse of unresolved/disorganized psychotherapy patients: An exploratory study of an attachment classification. Frontiers in Psychology, 5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca G. A., Balfour L., Ritchie K., Bissada H. (2007). The relationship between attachment scales and group therapy alliance growth differs by treatment type for women with binge eating disorder. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 11(1), 1-14. doi:10.1037/1089-2699.11.1.1. [Google Scholar]

- Tasca G. A. (2014). Attachment and group psychotherapy: Introduction to a special section. Psychotherapy, 51(1), 53-56. doi:10.1037/a0033015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca G. A., Maxwell H. (2021). Attachment and group psychotherapy: Applications to work groups and teams. In Parks C. D., Tasca G. A. (Eds.), The psychology of groups: The intersection of social psychology and psychotherapy research (pp. 149-167). American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/0000201-009. [Google Scholar]

- Teti D. M., Killeen L. A., Candelaria M., Miller W., Hess C. R., O’Connell M. (2008). Adult attachment, parental commitment to early intervention, and developmental outcomes in an African American sample. In Steele H., Steele M. (Eds.), Clinical applications of the adult attachment interview (pp. 126-153). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Volkert J., Georg A., Hauschild S., Herpertz S. C., Neukel C., Byrne G., Taubner S. (2019). Bindungskompetenzen psychisch kranker Eltern stärken: Adaptation und Pilottestung des mentalisierungsbasierten Leuchtturm-Elternprogramms [Strengthen attachment competencies of mentally ill parents: Adaptation and pilot-testing of the mentalizationbased Lighthouse parent program]. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, 68(1), 27-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. (2014). The ultra-social animal. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 187-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treboux D., Crowell J. A., Waters E. (2004). When’ new’ meets’ old’: configurations of adult attachment representations and their implications for marital functioning. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J.R., Wade N.G., Abraham W.T., Bittman-Heinrichs R.L., Cornish M.A., Post P.C. (2020). Modeling cohesion change in group counseling: the role of client characteristics, group variables, and leader behaviors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(3), 371-385. doi:10.1037/ cou0000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom I. D., Leszcz M. (2020). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Zegers M. A. M., Schuengel C., van IJzendoorn M. H., Janssens J. M. A. M. (2006). Attachment representations of institutionalized adolescents and their professional caregivers: Predicting the development of therapeutic relationships. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(3), 325-334. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]