Abstract

Introduction: The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of traumatic experiences and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in treatment-seeking individuals with ongoing substance use disorder (SUD) compared to individuals who have recovered from SUD. Methods: Patients with SUD recruited from the STAYER study (N = 114) underwent an examination of alcohol and drug use, childhood trauma, negative life events and PTSD symptomatology. In this study, only participants with 12-month concurrent polysubstance use was included. Using historical data from the STAYER study, alcohol and drug trajectories were dichotomised as (1) current SUD (current SUD) or (2) recovered from substance use disorder (recovered SUD). Crosstabs and chi-tests were used to measure differences between groups. Results: Childhood maltreatment, traumatic experiences later in life and symptoms of concurrent PTSD were highly prevalent in the study population. We found no significant difference between the current and recovered SUD groups. Recovered women reported a lower prevalence of physical neglect (p = 0.031), but a higher prevalence of multiple lifetime traumas (p = 0.019) compared to women with current SUD. Both women with current SUD and recovered women reported a significantly higher prevalence of sexual aggression than men (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). In addition, men who have recovered from SUD reported a lower prevalence of PTSD symptoms over cut-off 38 (p = 0.017), of re-experiencing (p = 0.036) and of avoidance (p = 0.015), compared to recovered women. Conclusion: Reported trauma did not differ between persons with current SUD and those who had recovered from SUD. Gender differences discovered in this study indicate the importance of developing individualised and gender-specific treatment models for comorbid PTSD/SUD.

Keywords: gender differences, prevalence, recovered, substance use disorder, traumatic experiences

Traumatic experiences are well-known risk factors for substance use disorders (SUD) (Heffernan et al., 2000; Kendler et al., 2000). Although the potential causal nature of this relationship is debated, previous studies indicate that the negative impacts of childhood trauma can reduce the ability to cope later in life, and increase various high-risk behaviours, such as drug use (Kerr et al., 2009; Ompad et al., 2005; Stoltz et al., 2007). The comorbidity between SUD and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after traumatic experiences is reported to be common (Brady et al., 2004; Guðmundsdóttir, 2018), with prevalence estimated in the range of 25%–49% in different studies (Bonin et al., 2000; Driessen et al., 2008; Gielen et al., 2012). The comorbidity estimates are three times higher than in the general population and are most prevalent in people with dependence to illicit drugs, compared to alcohol (Driessen et al., 2008).

Despite the substantial body of literature on the prevalence of traumatic experiences and PTSD among individuals who suffer from SUD (Zhang et al., 2020), less is known about possible differences in the prevalence of traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms between individuals with current SUD and those who recover from SUD. Since comorbid PTSD/SUD is associated with adverse treatment outcomes (Driessen et al., 2008; McCauley et al., 2012), one could expect that long-term outcomes from SUD treatment is associated with lower prevalence of traumatic experiences, as well as a lower prevalence of PTSD symptoms. Due to the variable nature of traumatic experiences, differences in the timing of trauma exposure, type of trauma and associated symptoms might also contribute significantly to the long-term outcomes. Thus, further studies are needed to provide clinical guidelines and aid the development of individualised treatment schedules for patients with SUD.

Traumatic experiences involving a betrayal of trust (such as childhood abuse perpetrated by an adult who is close to the victim) may lead to a set of outcomes that differ in kind from traumas that do not involve betrayal (Freyd, 1996). Life threat predicts symptoms of anxiety and hyper-arousal, while social betrayal predicts symptoms of dissociation, emotional numbness and depression, and future constricted or abusive relationships (Freyd, 1999). High levels of both life threat and social betrayal characterise the most severe traumatic events; with both aspects present, both classes of symptoms can co-occur (Freyd, 2001; Goldberg & Freyd, 2006). These differences might be important for both clinicians and patients, and will be instrumental in establishing a case formulation, treatment schedule and timing of interventions for the individual patient. For example, patients with anxiety- and hyper-arousal-dominated PTSD symptoms could benefit more from exposure-based techniques, while patients with symptoms of emotional numbness, depression and a tendency to repeat a pattern of being involved in abusive relationships might need a different approach. In addition, the timing and expected long-term outcomes for SUD-specific interventions are currently unknown. Thus, the lack of empirical data on types of trauma, PTSD symptom clusters and long-term outcomes hinder the development of more refined treatment approaches for patients with SUDs.

Gender differences in trauma symptoms highlight the clinical relevance of differentiating between types of traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms. In the general population, men are most at risk of traumatic experiences, while PTSD symptoms are over-represented among women (Breslau, 2002). Previous studies have argued that women more frequently are exposed to traumatic events perpetrated by someone close to them, while men report having experienced traumatic events perpetrated by someone not close (Brosky & Lally, 2004; Goldberg & Freyd, 2006). Thus, the risk of developing different symptom clusters is different for women and men in the general population (Breslau, 2002). In the SUD population, the risk of traumatic experiences is elevated, but there is a general lack of data on the differences in traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms between male and female patients (Breslau, 2002).

While trauma and PTSD symptoms have been investigated in several SUD samples, data from samples with a history of polysubstance use are generally lacking. Poly-SUD is a part of a pattern of problematic substance use and refers to a patient using multiple substances, and meeting the SUD criteria for some, but not necessarily all of them (Hetland et al., 2021). Polysubstance use is common among drug users worldwide, and the majority of patients with SUD report polysubstance use (Hiebler-Ragger & Unterrainer, 2019). Data from a Finnish registry-based study report that 90% of treatment-seeking individuals with SUD use an average of 3.5 substances, including polysubstance use both simultaneously and concurrently (Onyeka et al., 2012). A high prevalence of polysubstance use is particularly concerning as it can negatively affect treatment outcomes and severity of substance use disorders. SUD negatively affects mental, cognitive and physical health and can consequently lead to increased risk behaviour (e.g., violence, overdose) (Crummy et al., 2020). Compared to mono-SUD patients, polysubstance users have more depressive and suicidal symptoms at treatment admission than single-substance users, and more social anxiety symptoms than alcohol-only users (Burdzovic Andreas et al., 2015). Lastly, Gjersing and Bretteville-Jensen (2018) demonstrated that polysubstance use has a 10-fold increase in mortality risk when compared to the general population.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of different traumatic experiences, and symptoms of PTSD, in individuals with ongoing SUD compared to individuals who have recovered from drug use. Furthermore, the study investigates possible gender differences in the prevalence of different traumatic experiences, and PTSD symptoms, among current versus recovered users.

Methods

Participants and study design

This study is based on data from the Stavanger project on addiction and recovery: the STAYER study (Hagen et al., 2016), a prospective, longitudinal cohort study on cognitive, psychological and social recovery processes related to changes in substance use among people with SUD in Rogaland, Norway, initiated in 2012. The STAYER study recruited patients from inpatient treatment facilities, outpatient treatment facilities and private treatment facilities in the Stavanger University Hospital catchment area. All participants fulfil the criteria for a diagnosis of F1x.1 (harmful use) or F1x.2 (dependency syndrome), as defined by the ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992). As in former STAYER studies (Erga et al., 2021), polysubstance users were defined as patients with SUD who reported use of multiple substances within the last year before inclusion. The inclusion criteria in this sub-study were: (1) a signed written informed consent; (2) meeting the diagnostic criteria for SUD as described above; (3) polysubstance use defined as “concurrent use of multiple drugs or alcohol the last year”; (4) participant initiating a course of treatment within the substance abuse treatment services; and (5) aged 16 years or older.

A total of 208 participants were recruited to the STAYER study at baseline. In 2018, consenting participants provided additional data used in this sub-study. Out of the 208 participants at baseline, eight are dead, eight have dependences other than substance use, another 17 are excluded due to not fulfilling the criteria of poly-SUD as defined above, 13 did not want to participate in this sub-study and 48 have dropped out on earlier measurement points for other reasons (e.g., no contact or no wish to continue their participation in the study). A total of 114 participants consented to provide the additional data used in this sub-study during their four- to eight-year follow-up visit, between November 2018 and November 2020. Due to missing responses on single items and subsequent exclusion in analyses, the final total of participants equals 106. For the same reason, in specific analyses n is lower; see Table 1 for descriptions. This project was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (REK 2011/1877 and REK 2018/1528) and conducted according to its guidelines and those of the Helsinki Declaration (1975). All participants gave their informed written consent.

Table 1.

Trauma and PTSD symptoms in recovered versus current users (n = 106).

| Whole sample (n = 106) | C-SUD (n = 55) |

R-SUD (n = 51) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Demographic factors | ||||||

| Age, years | 106 | 35 (7.2) | 55 | 34 (7.8) | 51 | 35 (6.7) |

| Women | 106 | 34.9 | 55 | 34.5 | 51 | 35.3 |

| Age of first substance use, years | 106 | 13.0 (2.3) (2.3) | 55 | 12.6 (2.2) | 51 | 13.4 (2.3) |

| Born in Norway | 106 | 94.3 | 55 | 94.5 | 51 | 94.1 |

| Stable living conditions | 106 | 61.3 | 55 | 69.1 | 51 | 52.9 |

| Stable income | 106 | 62.3 | 55 | 61.8 | 51 | 62.7 |

| CTQ-SF | ||||||

| Any childhood trauma | 94 | 72.3 | 49 | 79.6 | 45 | 64.4 |

| Multiple childhood traumas | 94 | 52.1 | 49 | 59.2 | 45 | 44.4 |

| Physical abuse | 98 | 30.6 | 52 | 38.5 | 46 | 21.7 |

| Sexual abuse | 98 | 24.5 | 52 | 26.9 | 46 | 21.7 |

| Emotional abuse | 98 | 49.0 | 52 | 55.8 | 46 | 41.3 |

| Physical neglect | 96 | 53.1 | 50 | 62.0 | 46 | 43.5 |

| Emotional neglect | 96 | 36.5 | 51 | 41.2 | 45 | 31.1 |

| LEC-5 | ||||||

| Any lifetime trauma | 90 | 94.4 | 47 | 93.6 | 43 | 95.3 |

| Multiple lifetime traumas | 90 | 86.7 | 47 | 83.0 | 43 | 90.7 |

| Natural disaster | 98 | 4.1 | 52 | 3.8 | 46 | 4.3 |

| Accidents | 98 | 67.3 | 51 | 68.6 | 47 | 66.0 |

| Physical aggressions | 99 | 73.7 | 52 | 76.9 | 47 | 70.2 |

| Sexual aggressions | 99 | 45.5 | 52 | 42.3 | 47 | 48.9 |

| War-related trauma | 99 | 0 | 52 | 0 | 47 | 0 |

| Exposure to injury, illness, death | 98 | 77.6 | 51 | 74.5 | 47 | 80.9 |

| Others | 92 | 66.3 | 48 | 60.4 | 44 | 72.7 |

| Both childhood and lifetime trauma | 85 | 70.6 | 44 | 75.0 | 41 | 65.9 |

| PCL-5 a | ||||||

| Score over 38 | 81 | 24.7 | 42 | 23.8 | 39 | 25.6 |

| Re-experiencing | 81 | 60.5 | 42 | 54.8 | 39 | 66.7 |

| Avoidance | 82 | 50.0 | 43 | 51.2 | 39 | 48.7 |

| Negative alterations | 82 | 59.8 | 43 | 58.1 | 39 | 61.5 |

| Hyper-arousal | 82 | 51.2 | 43 | 53.5 | 39 | 48.7 |

Note. Values are given as % unless otherwise indicated. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SD = standard deviation.

Measured on participants with experience of trauma.

* p ≤ .05, ** p ≤ .01, *** p ≤ .001.

Measurements

Current polysubstance use disorder (CUR) versus recovered from polysubstance use disorder (REC)

CUR versus REC were measured by the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT- C) (Berman et al., 2005) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) (Bush et al., 1998). In line with previous studies on the same study population (Erga et al., 2021), DUDIT-C score ≥1 was used as a definition of CUR, while DUDIT-C = 0 was defined as recovered from substance use. For AUDIT-C, a score of ≥5 defined problematic alcohol use. This higher cut-off score has previously been used to identify unhealthy alcohol use in at-risk populations (Erga et al., 2021; Rubinsky et al., 2013). In this study, subsequently, ≤4 was defined as recovered from problematic alcohol use. In the final analyses in this study, we used the dichotomised variable, CUR = DUDIT-C ≥1 or AUDIT-C ≥5, and REC = DUDIT-C 0 and AUDIT-C ≤4. Recovered users have all been defined as current users at baseline.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ-SF)

The CTQ-SF is the most commonly used screening tool to retrospectively assess childhood abuse in medical research (Thombs et al., 2007). It consists of 28 items that are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from “never true” to “very often true”. It is used in both clinical and community populations and has evidence for validity in populations with SUD (Bernstein et al., 2003; Thombs et al., 2007). The CTQ-SF measures five different dimensions of childhood trauma: physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and physical and emotional neglect. Previous studies indicate that all dimensions are associated with an increased risk of SUDs (Afifi et al., 2012; Dube et al., 2003; Kerr et al., 2009; Schnieders et al., 2006). The CTQ-SF includes a minimisation/denial validity scale that was developed to detect the underreporting of maltreatment (Bernstein et al., 1998). In this study, we used the five dimensions, and the dichotomous clinical cut-off scores that differentiate between the presence or absence of significant abuse or neglect (Bevilacqua et al., 2012; Erfanian, 2018; Walker et al., 1999). The cut-off scores were 8 or higher for physical abuse, physical neglect and sexual abuse, 10 or higher for emotional abuse and 15 or higher for emotional neglect (Bevilacqua et al., 2012; Erfanian, 2018; Walker et al., 1999).

Life Event Checklist (LEC-5)

The LEC-5 is a measurement tool of lifetime exposure to traumatic events. The LEC-5 screens for 17 potentially traumatic events in the respondent’s lifetime, clustered in seven types: (1) natural disasters; (2) accidents; (3) physical aggressions; (4) sexual aggressions; (5) war-related trauma; (6) exposure to illness, injury or death; and (7) exposure to any other very stressful event (Weathers et al., 2013). Responses are on a 6-point nominal scale (“happened to me”, “witnessed it”, “learned about it”, “part of my job”, “not sure”, “doesn’t apply”). To avoid a Type I error and since, in this study, we are interested in measuring first-hand experience of traumatic events, answers were dichotomised in the following way: “happened to me” = 1, “all others” = 0.

The PTSD Checklist (PCL-5)

The PCL-5 consists of 20 items, each measuring one symptom of PTSD, grouped into four symptom clusters: (1) re-experiencing; (2) avoidance; (3) negative alterations of cognition and mood; and (4) hyper-arousal (Sveen et al., 2016). Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale (“not at all” = 0, “a little bit” = 1, “moderately” = 2, “quite a bit” = 3, “extremely” = 4). Recommended total cut-off scores vary between different studies, in the range of 28–50 (Bondjers et al., 2020; Forbes et al., 2001). Newly published studies investigated a lower cut-off of 29–33 among a general population (Bondjers et al., 2020); however, higher (37 or above), in a population where it was expected to find PTSD, or for detecting probable cases of PTSD in non-clinical settings, such as survey research, when a follow-up assessment was not possible (Bondjers et al., 2020). To avoid false-positive responses, we used a cut-off score of 38, which has been used in clinical and non-clinical settings to detect probable cases of PTSD among populations where we expect to find a high prevalence of PTSD (Sveen et al., 2016; Weathers et al., 2013). This was the cut-off recommended by the National Center for PTSD at the time when the data of this study were collected and analysed. Further, there is no validated cut-off of the four symptom clusters; however, in clinical use mean scores (range of 0–4) of each subscale are used. We dichotomised each subscale at a mean score of 2, which is equivalent to symptom severity reported being “moderately” and above.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0. As all variables were dichotomised, chi-square tests were conducted to measure significant differences between groups. To measure differences between current and recovered users within gender, chi-square tests were conducted separately for each gender (significant differences are presented in bold in Table 2). To measure gender differences within the current and recovered user groups, chi-square tests were conducted for each group of current and recovered users (significant differences are presented in a separate column marked “p” in Table 2). Measurements of PTSD symptoms are made for participants with experience of trauma.

Table 2.

Gender differences in trauma and PTSD symptoms in recovered versus current SUD users (n = 106).

| Current SUD | Recovered from SUD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | p b | Men | Women | p b | |

| Demographic factors | ||||||

| Age, years | 36 (8.2) | 32 (6.5) | 36 (7.4) | 33 (4.2) | ||

| Age of first substance use, years | 12.4 (2.3) | 13 (1.9) | 13 (2.6) | 14 (1.4) | ||

| Born in Norway | 91.7 | 100 | 93.9 | 94.4 | ||

| Stable living condition | 75.0* | 57.9 | 45.5* | 66.7 | ||

| Stable income | 72.2 | 42.1 | * | 63.6 | 61.1 | |

| CTQ-SF | ||||||

| Any childhood trauma | 73.3 | 89.5 | 60.7 | 70.6 | ||

| Multiple childhood traumas | 50.0 | 73.7 | 35.7 | 58.8 | ||

| Physical abuse | 42.4 | 31.6 | 25.0 | 16.7 | ||

| Sexual abuse | 21.2 | 36.8 | 17.9 | 27.8 | ||

| Emotional abuse | 51.5 | 63.2 | 35.7 | 50.0 | ||

| Physical neglect | 51.6 | 78.9* | 42.9 | 44.4* | ||

| Emotional neglect | 31.3 | 57.9 | 25.0 | 41.2 | ||

| LEC-5 | ||||||

| Any lifetime trauma | 96.7 | 88.2 | 92.6 | 100 | ||

| Multiple lifetime traumas | 90.0 | 70.6* | 85.2 | 100* | ||

| Natural disaster | 6.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | ||

| Accidents | 72.7 | 61.1 | 65.5 | 66.7 | ||

| Physical aggressions | 81.8 | 68.4 | 75.9 | 61.1 | ||

| Sexual aggressions | 21.2 | 78.9 | *** | 27.6 | 83.3 | *** |

| War-related trauma | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Exposure to injury, illness, death | 81.3 | 63.2 | 79.3 | 83.3 | ||

| Others | 63.3 | 55.6 | 66.7 | 82.4 | ||

| Both childhood and lifetime trauma | 70.4 | 82.4 | 61.5 | 73.3 | ||

| PCL-5 a | ||||||

| Score over 38 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 12.5 | 46.7 | * | |

| Re-experiencing | 51.9 | 60.0 | 54.2 | 86.7 | * | |

| Avoidance | 44.4 | 62.5 | 33.3 | 73.3 | * | |

| Negative alterations | 51.9 | 68.8 | 50.0 | 80.0 | ||

| Hyper-arousal | 48.1 | 62.5 | 41.7 | 60.0 | ||

Note. Values are given as % unless otherwise indicated. Significant differences between groups within gender are presented in bold. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SD = standard deviation; SUD = substance use disorder.

Measured on participants with experience of trauma. bSignificant differences between gender within groups.

* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001.

Results

Demographic data are summarised in Table 1. Overall, childhood and lifetime trauma were highly prevalent in the study population, and was evident in 72.3% and 94.4%, respectively. For a detailed description of prevalence of CTQ-SF, LEC-5 and PCL-5 in the whole sample, see Table 1.

Trauma and PTSD symptoms in recovered versus current users

A total of 55 (51.9%) participants were categorised as current SUD at the time of assessment, while 51 (48.1%) were categorised as recovered SUD. Childhood trauma and lifetime trauma were prevalent for both groups, with frequency estimates of childhood trauma above 64% and the frequency of lifetime trauma above 93% for both groups. There were no significant differences between the groups (p = 0.229 and p = 0.631, respectively) (see Table 1 for a detailed presentation of the frequency of trauma in these groups). PTSD symptoms were observed in 23.8% and 25.6% of participants with current and recovered SUD, respectively. For a detailed description of prevalence of traumatic experiences and concurrent PTSD symptoms among people with current compared to recovered SUD, see Table 1.

Gender differences

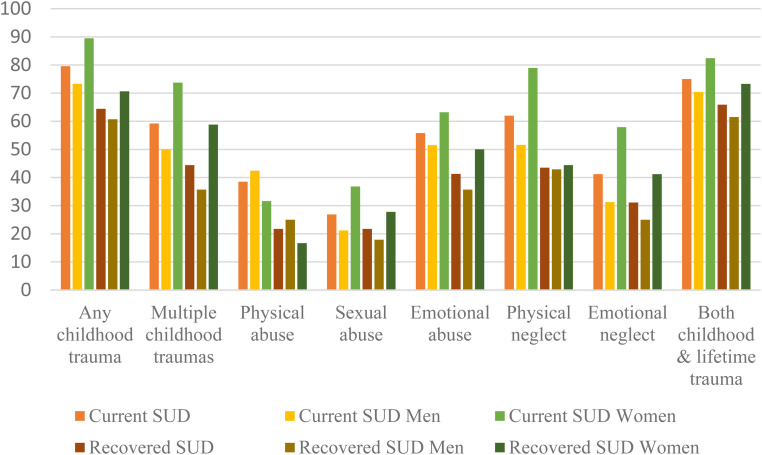

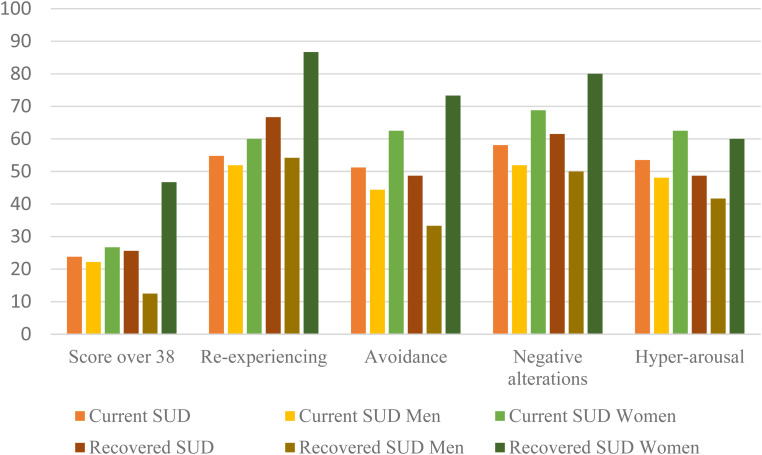

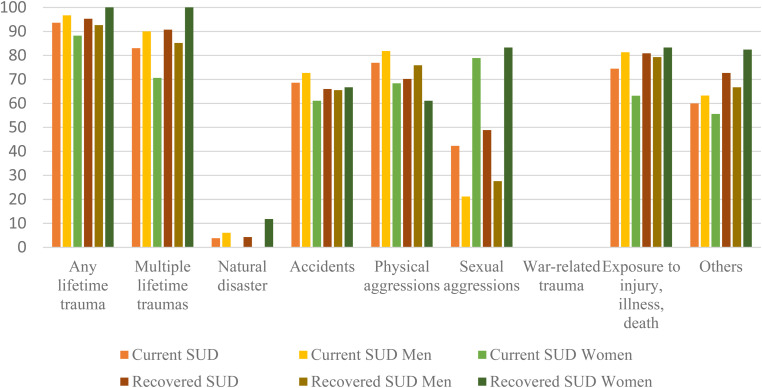

For an overview of gender differences in demographic variables, prevalence of childhood trauma, lifetime trauma and symptoms of concurrent PTSD in current versus recovered SUD groups, see Table 2 and Figures 1–3.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of childhood trauma (n = 106).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters (n = 106).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of lifetime trauma (n = 106).

Between-group analysis among male participants demonstrated a significant difference between participants with current SUD and recovered SUD on the variable “Stable living condition” (45.5% vs. 75.0%, p = 0.012). Between-group analysis among female participants demonstrated no demographic differences, but a lower prevalence of physical neglect (44.4% vs. 78.9%, p = 0.031) and a higher prevalence of multiple lifetime traumas (100% vs. 70.6%, p = 0.019) among the recovered SUD group, when compared to women in the current SUD group.

Regarding gender differences within the two groups—current versus recovered SUD—female current participants reported a significantly lower prevalence of stable income than male participants (42.1% vs. 72.2%, p = 0.029), and a significantly higher prevalence of lifetime traumatic experience of sexual aggression than men (78.9% vs. 21.2%, p < 0.001). In the recovered SUD group, women reported a significantly higher prevalence of sexual aggressions than men (83.3 vs. 27.6%, p < 0.001). In addition, recovered SUD women reported a higher prevalence of PTSD symptoms over the cut-off of 38 (46.7% vs. 12.5%, p = 0.017), of re-experiencing (86.7 vs. 54.2%, p = 0.036) and of avoidance (73.3% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.015).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of traumatic experiences and concurrent PTSD symptoms among people with SUD compared to people who have recovered from SUD, with a special focus on gender differences. We found no significant differences between current and recovered users in prevalence of childhood traumas, traumatic experiences later in life or current PTSD symptoms. However, when investigating gender differences between the groups, we found that women with recovered SUD reported a lower prevalence of the childhood trauma physical neglect and a higher prevalence of multiple lifetime traumas than women with current SUD. Women in both the current and recovered SUD groups reported a significantly higher prevalence of having experienced sexual aggression than men. Within recovered SUD group, women reported a higher prevalence than men of the PTSD symptom clusters re-experiencing and avoidance, as well as scores over the cut-off indicating PTSD.

We know that childhood trauma increases the risk of mental illness in general (Afifi & Asmundson, 2020) and of substance abuse in particular (Gielen et al., 2012). This is in line with the results of this study. Childhood trauma was evident in a larger percentage of this study population (72.3%) than in the meta-analysis by Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2020). This could be explained by the fact that our study population experience, or have experienced, SUD, compared to other studies often including alcohol use disorder (AUD), since the prevalence of traumatic experiences is reported to be higher among people with SUD compared to AUD (Driessen et al., 2008).

The prevalence of lifetime trauma is also high (94.4%) in our study population, which could be explained by the high-risk lifestyle where people with SUDs place themselves in dangerous situations which leads to increased exposure to trauma (Jacobsen et al., 2001). It can also be explained by a trauma trajectory, where childhood trauma increases the risk of traumatic experiences later in life (Maschi et al., 2013).

Even though childhood trauma and traumatic experiences predict polysubstance abuse, the results of this study do not indicate that severity or number of traumas predict recovery from polysubstance abuse. We found no differences between the current and recovered SUD groups regarding traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms. For women, multiple lifetime traumas were significantly more common among the recovered SUD group. This indicate that type of, as well as number of, traumatic experiences seem not to be an obstacle when identifying factors associated with a recovery process. This contradicts previous research indicating that traumatic experiences or comorbidity with PTSD lead to less improvement during treatment (Driessen et al., 2008; McCauley et al., 2012; Norman et al., 2007). This could be explained by the fact that other factors, such as different types of coping strategies, might be of more importance in treatment.

Our results are in line with previous research arguing that all sub-categories of childhood traumas are associated with current SUD (Afifi et al., 2012; Dube et al., 2003; Kerr et al., 2009; Schnieders et al., 2006). However, physical neglect being reported at a significantly lower rate among recovered women compared to current is a new finding. Physical neglect is defined as the failure or inability to provide necessary care for a child (for reasons other than poverty), e.g., failure to provide necessary food, clothing and shelter, or inappropriate or lack of supervision. Studies show that childhood physical neglect is associated with long-term consequences of lower mental health outcome, e.g., higher levels of anxiety and depression and lower levels of self-esteem as well as having a hard time feeling secure in a relationship, and of becoming independent as an adult, both physically and emotionally (Widom et al., 2018). Further research needs to study these associations and possible explanations. However, our findings imply that women with SUD and experience of physical neglect have a worse prognosis for recovery.

When investigating gender differences within the groups, both current and recovered users report a higher prevalence of experiences of sexual aggression among women than among men. This is in line with previous research (Najdowski & Ullman, 2009) and could be a result of women in general being at higher risk of sexual assault, or be explained by the high-risk lifestyle of many women with SUD (Brady et al., 2004). It could also be explained by the fact that social betrayal predicts both emotional numbness and repeating of the pattern of being involved in constricted or abusive relationships (Freyd, 1999).

Apart from sexual aggression, there were no other significant differences between the genders among the current SUD group. Among the recovered SUD individuals, however, women reported symptoms above the cut-off indicating PTSD, as well as above the cut-off of the sub-clusters re-experiencing and avoidance. Repressive coping, which means avoiding unpleasant thoughts, emotions and memories, has been associated with resilience in some groups. A study of women with a history of sexual abuse showed that individuals with repressive coping were better adjusted (less withdrawn, anxious or depressed) than other survivors (Bonanno et al., 2003). These findings indicate that gender and type of background experiences may lead to one combination of protective factors, while other combinations might be more protective for other individuals. This heterogeneous and multidimensional approach needs to be further explored and systematised in future research.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of the study is that the participants provide a representative sample of a treatment-seeking population with SUD. The study does have several limitations, including data being gathered 4–8 years after baseline inclusion in the STAYER study. Attrition may have an impact on the frequency estimates of childhood and lifetime trauma, and the frequency of PTSD symptoms. Since we have not corrected the p value for multiple testing, the statistical power is low. With a correction, p = 0.0009 would have given statistical significance. The categorisation of recovered versus current SUD is based on self-reported measures and not objective measures such as urine, blood or hair samples. Although the objective data on substance use are considered superior to self-reported data, self-reported measures are considered valid and reliable in the clinical follow-up of patients with SUD (Secades-Villa & Fernández-Hermida, 2003). The use of mean scores of the four symptom clusters of PCL-5 is common in clinical settings but is questioned in this population where a higher cut-off could be discussed and investigated.

Both men and women tend to underreport abusive experiences (Hardt & Rutter, 2004). Previous studies have shown that men are less likely than women to characterise themselves as survivors of abuse, even when there is evidence of a history of abusive experiences (Thombs et al., 2006; Widom & Morris, 1997). Despite this tendency, we saw a high reported prevalence of abusive experiences among men. This could be due to the data being collected in a personal interview by research assistants that knew the participants well and had followed them up since the start of the study in 2012. The discussion on possible explanations and implications of findings as the significantly higher prevalence of PTSD symptoms among recovered women can only be speculative and left for future research to explore further.

Conclusion

Childhood trauma and traumatic experiences later in life are highly prevalent both among the recovered and current SUD groups, and among participants with SUD who have entered treatment. Future research should investigate moderating or mediating factors relevant to the recovery process. Such factors could be, for example, different types of coping strategies, and subsequent different needs of focus in treatment. Gender differences are discovered in this study. In women, having experienced multiple lifetime traumas was significantly more common among recovered compared to women with current SUD. For the recovered SUD group, PTSD symptoms were significantly more prevalent among women than among men. This indicates the importance of developing individualised and gender-specific treatment models for comorbid PTSD/SUD.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the participants in our study and the staff of the participating clinical services, the KORFOR staff, and in particular, Thomas Solgård Svendsen, who collected all the initial and follow-up data, in collaboration with A-LMN and JÅ. A special thanks to Sverre Nesvåg at Center for Alcohol and Drug Research, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway for valuable guidance and fruitful discussions.

Footnotes

Availability of data and material: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Center for Alcohol and Drug Research, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway.

ORCID iDs: Anna Belfrage https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0760-374X

Siri Lunde https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8829-3412

Elise Constance Fodstad https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8378-8494

Torgeir Gilje Lid https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0088-411X

Contributor Information

Elise Constance Fodstad, Center for Alcohol and Drug Research, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; and Department of Psychosocial Science, Faculty of Psychology, University of Bergen, Norway.

Torgeir Gilje Lid, Center for Alcohol and Drug Research, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; and Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway.

Aleksander Hagen Erga, Center for Alcohol and Drug Research, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; The Norwegian Centre for Movement Disorders, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; and Department of Biological and Medical Psychology, University of Bergen, Norway.

References

- Afifi T. O., Asmundson G. J. G. (2020). Chapter 17 - current knowledge and future directions for the ACEs field. In Asmundson G. J. G., Afifi T. O. (Eds.), Adverse childhood experiences (pp. 349–355). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi T. O., Henriksen C. A., Asmundson G. J., Sareen J. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and substance use disorders among men and women in a nationally representative sample. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(11), 677–686. 10.1177/070674371205701105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman A. H., Bergman H., Palmstierna T., Schlyter F. (2005). Evaluation of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. European Addiction Research, 11(1), 22–31. 10.1159/000081413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D. P., Fink L., Handelsman L., Foote J. (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire. Assessment of family violence: A handbook for researchers and practitioners.

- Bernstein D. P., Stein J. A., Newcomb M. D., Walker E., Pogge D., Ahluvalia T., Stokes J., Handelsman L., Medrano M., Desmond D., Zule W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua L., Carli V., Sarchiapone M., George D. K., Goldman D., Roy A., Enoch M. A. (2012). Interaction between FKBP5 and childhood trauma and risk of aggressive behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(1), 62–70. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G. A., Noll J. G., Putnam F. W., O’Neill M., Trickett P. K. (2003). Predicting the willingness to disclose childhood sexual abuse from measures of repressive coping and dissociative tendencies. Child Maltreatment, 8(4), 302–318. 10.1177/1077559503257066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondjers K., Willebrand M., Arnberg F. (2020). Psychometric Properties of the Swedish Version of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Sensitivity, Specificity, Diagnostic Accuracy and Structural Validity in a Mixed Trauma Sample In K. Bondjers (Ed.), Post-traumatic stress disorder-Assessment of current diagnostic definitions. Doctoral dissertation, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Bonin M. F., Norton G. R., Asmundson G. J., Dicurzio S., Pidlubney S. (2000). Drinking away the hurt: The nature and prevalence of PTSD in substance abuse patients attending a community-based treatment program. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31(1), 55–66. 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00008-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady K. T., Back S. E., Coffey S. F. (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(5), 206–209. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00309.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. (2002). Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Gender-Specific Medicine: JGSM: The Official Journal of the Partnership for Women's Health at Columbia, 5(1), 34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosky B. A., Lally S. J. (2004). Prevalence of trauma, PTSD, and dissociation in court-referred adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(7), 801–814. 10.1177/0886260504265620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdzovic Andreas J., Lauritzen G., Nordfjaern T. (2015). Co-occurrence between mental distress and poly-drug use: A ten year prospective study of patients from substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 48, 71–78. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K., Kivlahan D. R., McDonell M. B., Fihn S. D., Bradley K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crummy E. A., O’Neal T. J., Baskin B. M., Ferguson S. M. (2020). One is not enough: Understanding and modeling polysubstance use. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 569. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen M., Schulte S., Luedecke C., Schaefer I., Sutmann F., Ohlmeier M., Kemper U., Koesters G., Chodzinski C., Schneider U., Broese T., Dette C., Havemann-Reinicke U. (2008). Trauma and PTSD in patients with alcohol, drug, or dual dependence: A multi–center study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(3), 481–488. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00591.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S. R., Felitti V. J., Dong M., Chapman D. P., Giles W. H., Anda R. F. (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erfanian M. (2018). Childhood trauma: A risk for major depression in patients with psoriasis. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28, 1–8. 10.1080/24750573.2018.1452521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erga A. H., Hønsi A., Anda-Ågotnes L. G., Nesvåg S., Hesse M., Hagen E. (2021). Trajectories of psychological distress during recovery from polysubstance use disorder. Addiction Research & Theory, 29(1), 64–71. 10.1080/16066359.2020.1730822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D., Creamer M., Biddle D. (2001). The validity of the PTSD checklist as a measure of symptomatic change in combat-related PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(8), 977–986. 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00084-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd J. J. (1999). Blind to betrayal: New perspectives on memory. The Harvard Mental Health Letter, 15(12), 4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd J. J. (2001). Memory and dimensions of trauma terror may be “all-too-well terror may be “all-too-well remembered'and a betrayal buried. In Conte J. R. (Ed.), Critical Issues in Remembere'and Betrayal Buried (pp. 139-176). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen N., Havermans R., Tekelenburg M., Jansen A. (2012). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among patients with substance use disorder: It is higher than clinicians think it is. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 17734. 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjersing L., Bretteville-Jensen A. L. (2018). Patterns of substance use and mortality risk in a cohort of ‘hard-to-reach’ polysubstance users. Addiction, 113(4), 729–739. 10.1111/add.14053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. R., Freyd J. J. (2006). Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: Gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a brief betrayal-trauma survey. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(3), 39–63. 10.1300/J229v07n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guðmundsdóttir Í. (2018). PTSD Among Substance Abusers: Prevalence of Various Trauma Types and the Concurrence of Addiction and Mental Disorders on PTSD [Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen E., Erga A. H., Hagen K. P., Nesvåg S. M., McKay J. R., Lundervold A. J., Walderhaug E. (2016). Assessment of executive function in patients with substance use disorder: A comparison of inventory- and performance-based assessment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 66, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J., Rutter M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan K., Cloitre M., Tardiff K., Marzuk P. M., Portera L., Leon A. C. (2000). Childhood trauma as a correlate of lifetime opiate use in psychiatric patients. Addictive Behaviors, 25(5), 797–803. 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00066-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetland J., Braatveit K. J., Hagen E., Lundervold A. J., Erga A. H. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of borderline intellectual functioning in a cohort of patients with polysubstance use disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 651028. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.651028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebler-Ragger M., Unterrainer H. F. (2019). The role of attachment in poly-drug use disorder: An overview of the literature, recent findings and clinical implications. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 579. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen L. K., Southwick S. M., Kosten T. R. (2001). Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(8), 1184–1190. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. S., Bulik C. M., Silberg J., Hettema J. M., Myers J., Prescott C. A. (2000). Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(10), 953–959. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T., Stoltz J.-A., Marshall B. D. L., Lai C., Strathdee S. A., Wood E. (2009). Childhood trauma and injection drug use among high-risk youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 300–302. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T., Baer J., Morrissey M. B., Moreno C. (2013). The aftermath of childhood trauma on late life mental and physical health: A review of the literature. Traumatology, 19(1), 49–64. 10.1177/1534765612437377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J. L., Killeen T., Gros D. F., Brady K. T., Back S. E. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder and co–occurring substance use disorders: Advances in assessment and treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 19(3), 283. 10.1111/cpsp.12006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski C. J., Ullman S. E. (2009). Prospective effects of sexual victimization on PTSD and problem drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 34(11), 965–968. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman S. B., Tate S. R., Anderson K. G., Brown S. A. (2007). Do trauma history and PTSD symptoms influence addiction relapse context? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(1), 89–96. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ompad D. C., Ikeda R. M., Shah N., Fuller C. M., Bailey S., Morse E., Kerndt P., Maslow C., Wu Y., Vlahov D., Garfein R., Strathdee S. (2005). Childhood sexual abuse and age at initiation of injection drug use. American Journal of Public Health, 95(4), 703–709. 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyeka I. N., Uosukainen H., Korhonen M. J., Beynon C., Bell J. S., Ronkainen K., Kauhanen J. (2012). Sociodemographic characteristics and drug abuse patterns of treatment-seeking illicit drug abusers in Finland, 1997-2008: The Huuti study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 31(4), 350–362. 10.1080/10550887.2012.735563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsky A. D., Dawson D. A., Williams E. C., Kivlahan D. R., Bradley K. A. (2013). AUDIT–C scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a US general population sample of drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(8), 1380–1390. 10.1111/acer.12092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders M., Rassaerts I., Schäfer M., Soyka M. (2006). Relevance of childhood trauma for later drug dependence. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie, 74(9), 511–521. 10.1055/s-2005-919143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secades-Villa R., Fernández-Hermida J. R. (2003). The validity of self-reports in a follow-up study with drug addicts. Addictive Behaviors, 28(6), 1175–1182. 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00219-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz J.-A. M., Shannon K., Kerr T., Zhang R., Montaner J. S., Wood E. (2007). Associations between childhood maltreatment and sex work in a cohort of drug-using youth. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1214–1221. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveen J., Bondjers K., Willebrand M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5: A pilot study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 30165–30165. 10.3402/ejpt.v7.30165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs B. D., Bernstein D. P., Ziegelstein R. C., Scher C. D., Forde D. R., Walker E. A., Stein M. B. (2006). An evaluation of screening questions for childhood abuse in 2 community samples: Implications for clinical practice. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(18), 2020–2026. 10.1001/archinte.166.18.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs B. D., Lewis C., Bernstein D. P., Medrano M. A., Hatch J. P. (2007). An evaluation of the measurement equivalence of the childhood trauma questionnaire—short form across gender and race in a sample of drug-abusing adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63(4), 391–398. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E. A., Unutzer J., Rutter C., Gelfand A., Saunders K., VonKorff M., Koss M., Katon W. (1999). Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7), 609–613. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F., Blake D., Schnurr P., Kaloupek D., Marx B., Keane T. (2013). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov

- Weathers F. W., Litz B. T., Keane T. M., Palmieri P. A., Marx B. P., Schnurr P. P. (2013). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov

- Widom C. S., Czaja S. J., Kozakowski S. S., Chauhan P. (2018). Does adult attachment style mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental and physical health outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 533–545. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C. S., Morris S. (1997). Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, part 2: Childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment, 9(1), 34. 10.1037/1040-3590.9.1.34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1992). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Lin X., Liu J., Pan Y., Zeng X., Chen F., Wu J. (2020). Prevalence of childhood trauma measured by the short form of the childhood trauma questionnaire in people with substance use disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113524. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]