Abstract

Background: Reversed Potts shunt has been a prospective approach to treat suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension, particularly when medication treatment fails to reduce right ventricular afterload.

Objective: This meta-analysis aims to review the clinical, laboratory, and hemodynamic parameters after a reversed Potts shunt in suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension patients.

Methods: Six electronic databases were searched from the date of inception to August 2021, where the obtained studies were evaluated according to the PRISMA statement. The effects of shunt creation were evaluated by comparing preprocedural to postprocedural or follow-up parameters, expressed as a mean difference of 99% confidence interval. Quality assessment was conducted using the STROBE statement.

Results: Seven studies suited the inclusion criteria which were included in this article. A reduction in upper and lower limb oxygen saturation [Upper limb: St. Mean difference -0.55, 99% CI -1.25 to 0.15; P=0.04; I2=6%. Lower limb: St. Mean difference –4.45, 99% CI –7.37 to –1.52; P<0.00001; I2=65%]. Reversed Potts shunt was shown to improve WHO functional class, 6-minute walk distance, NTpro-BNP level, and hemodynamic parameters including tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, interventricular septal curvature, and end-diastolic right ventricle/left ventricle ratio.

Conclusion: Reversed Potts shunt cannot be said to be relatively safe, although it allows improvement in the clinical and functional status in patients with suprasystemic PAH. Reversed Potts shunt procedure may be the last resort for drug-resistant pulmonary hypertension as it is considered a high-risk procedure performed on patients with extremely poor conditions.

This meta-analysis is registered in PROSPERO with the registration number 279757.

Keywords: Outcome, pulmonary arterial hypertension, reversed Potts shunt, suprasystemic, PRISMA, pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary artery coupling

1. INTRODUCTION

Pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease with a poor prognosis. Current treatment strategies intend to decrease the pulmonary vascular resistance and load to preserve RV function. Nevertheless, neither a persistent reversal of pulmonary vascular changes nor reduction of pulmonary arterial pressure could be achieved by currently available vasodilators [1]. To convert PAH with suprasystemic pulmonary arterial pressure into patent ductus arteriosus-Eisenmenger physiology, a novel side-to-side Potts shunt anastomosis was devised, and pilot studies have reported this procedure to be safe [2, 3]. However, since the physiology of Potts shunt creation on RV function, RV-pulmonary artery coupling has not been well studied; a systematic review and meta-analysis was created to study those effects in pediatric PAH.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Search Strategy

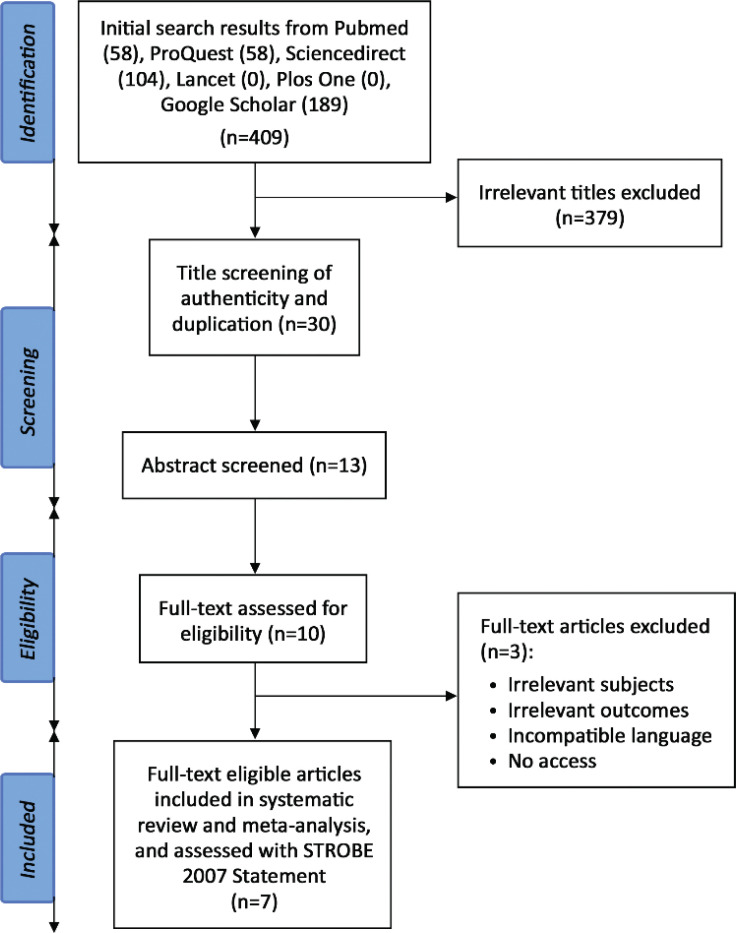

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [4]. We did a systematic search in PubMed, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Lancet, Plos One, and Google Scholar databases using the combination of keywords: (reversed Potts shunt) AND (pulmonary hypertension). The database search was conducted independently in August 2021 by four reviewers (BM, C, PA, IH) with equal contributions. Additionally, hand searching was conducted independently by the same reviewers (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

PRISMA flow of the systematic review and meta-analysis [4].

2.2. Study Criteria

The included studies complied with all eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria were patients with evidence of suprasystemic pulmonary arterial hypertension, the intervention of either surgical or transcatheter reversed Potts shunt creation, and follow-up assessment of clinical, laboratory, or hemodynamic parameters, including echocardiographic or catheterization outcome. The exclusion criteria were studies using unidirectional valved Potts shunt or modified reversed Potts shunt, studies in the form of editorial, case report, case series, review, or meta-analysis, and studies with the irretrievable full-text articles.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

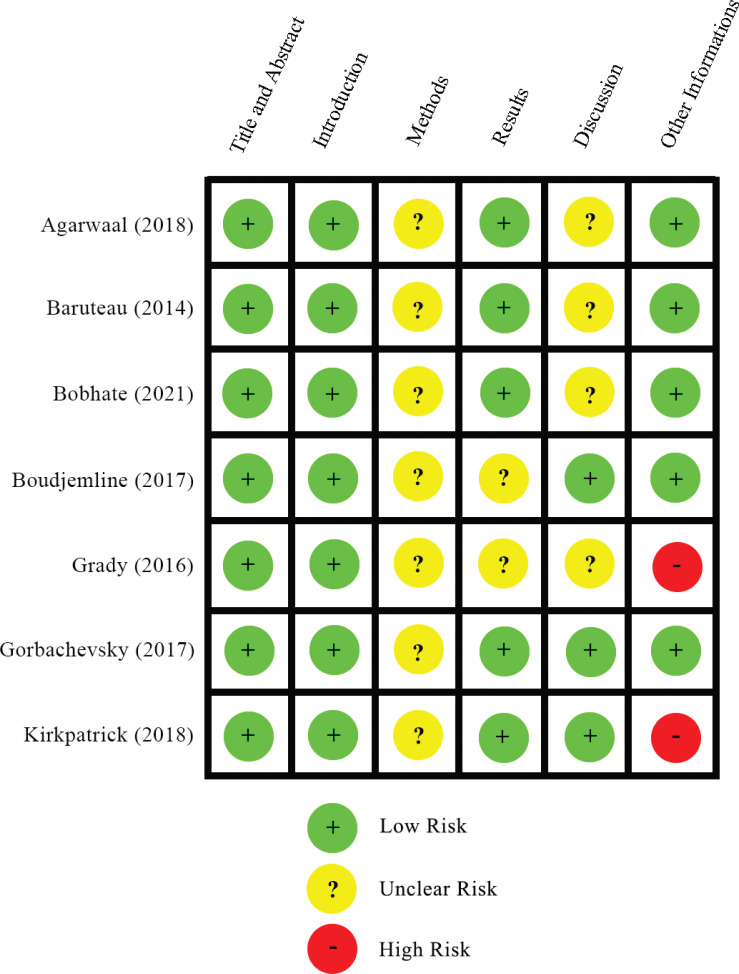

The screening and reviewing, continued by data extraction of the included studies was completed by four reviewers (BM, C, PA, IH). The data extracted from the included studies were study and patient characteristics (first author, year of publication, study design, setting, duration of follow-up, number of patients, age, weight, procedure either surgical or transcatheter), as well as preprocedural, postprocedural, and follow-up assessment of clinical parameter (WHO functional class, 6-minute walking test, adverse event), laboratory parameter (NTpro-BNP), hemodynamic parameter (upper limb SaO2, lower limb SaO2, SaO2 upper/lower limb gradient, mean pulmonary arterial pressure/MPAP, systolic right ventricular/RV pressure, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/TAPSE, interventricular septal curvature, end-diastolic RV/LV diameter ratio). Quality assessment of the included studies was conducted by four reviewers (BM, C, PA, IH) using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [5]. Any disagreement in the data extraction and the quality assessment was resolved by discussion between the four reviewers to reach a consensus (Fig. 2).

Fig. (2).

Summary of quality appraisal using STROBE statement [5].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Parametric data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while nonparametric data are expressed as median (interquartile range). The outcome of the reversed Potts shunt creation on the patients was evaluated by comparing preprocedural with postprocedural or follow-up parameters, expressed as a mean difference of 99% confidence interval (CI). A random-effects model was used to analyze the data with consideration of inconsistency in the baseline characteristics and outcomes of the patients. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for hypothesis testing. All statistical analyses were done using REVMAN (version 5.4; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) [6].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search Results

The PRISMA flow diagram of the literature screening and selection for this systematic review and meta-analysis is shown in Fig. (1). The initial search generated 409 potential studies from the selected databases. The exclusion of studies with irrelevant titles produced 30 studies for authenticity and duplication review. Eighteen studies were qualified for abstract screening, eliciting 15 studies for full-text screening. Elimination of 6 studies was performed due to irrelevant intervention and no access to full-text papers. Conclusively, nine studies complied with the eligibility criteria and thus were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

3.2. Study Characteristics

This systematic review covers nine studies that analyzed various outcomes of reversed Potts shunt in patients with suprasystemic PAH (Table 1). These studies consisted of three retrospective studies [7-9], one multicenter retrospective study [2], one retrospective single-center study [10], and two prospective single-center studies [3, 11] that were published from 2012 to 2021 in France, the USA, India, and Rusia [2, 3, 7-11]. Each included study had a distinct duration of follow-up with a mean and median of less than one year in two studies [3, 9], mean and median between 1-3 years in five studies [2, 7, 8, 10, 11]. The total number of participants involved in this review is 73 patients with the age of intervention ranging from 13.5 months to 20.7 years old [8, 9]. Weight of the patients varies among studies with the median and mean above 30 kg in three studies [3, 7, 10], a mean and median between 20-30 kg in one studies [11], and median of less than 20 kg in one study [2]. The remaining studies had no information on the participants' weight data. Four studies performed Potts shunt interventional surgery through thoracotomy [7, 8, 10, 11], two studies reviewed both surgical and transcatheter intervention [2,9], and a study by Boudjemline et al. (2017) [3] used the transcatheter approach as the interventional method. The adverse events of Potts shunt intervention reported in the included studies were bilateral lung transplantation [7], cardiac arrest after anesthetic induction, irreversible brain damage [3], pulmonary hypertensive crisis, heart failure [8], significant hemorrhage, pulmonary contusion, respiratory failure [9], and death. The total number of deaths of participants included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were 17 participants.

Table 1.

Study and patient characteristics of the included studies.

| No | Study (Year) | Study Design | Settings | Duration of Follow-up | No. of Patients | Age | Weight (kg) | Procedure | Adverse Events (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aggarwal et al (2018) | Retrospective cohort | St Louis Children Hospital, Boston | 27 (2.9-50.6) months | 11 | Median: 11.2 years | Median: 32.8 | Surgical | Bilateral lung transplant (1), death (2) |

| 2 | Baruteau et al (2014) | Retrospective multicenter study | Marie Lannelongue Hospital, Necker Hospital, and style="background-color: #D9D9D9" Bambino Gesu Children Hospital, France | 2.1 (3-14.3) years | 24 | 7.7 (1.5-17) years | 19.5 (10.2-47) | Surgical (19), Transcatheter (4) | Death (3) |

| 3 | Bobhate et al (2021) | Prospective single-center study | Children's Heart Center, Kokilaben Dhirubai Ambani Hospital and Research Center, India | 17 (1-40) months | 16 | 10.5 (4.3-17.3) years | 24.7 (13.2-50.3) | Surgical | Death (4) |

| 4 | Boudjemline et al (2017) | Prospective single-center study | Necker University Hospital, France | 10 ± 2.6 months | 6 | 11.0 ± 4.2 years | 37.8 ± 19.1 | Transcatheter | Cardiac arrest after anesthetic induction and postprocedural irreversible brain damage death (2) |

| 5 | Grady et al (2016) | Retrospective study single-center study | Washington University School of Medicine | 31.42 ± 18.4 weeks | 5 | 10.32 ± 5.1 years | 37.1 ± 24.4 | Surgical | - |

| 6 | Gorbachevsky et al (2017) | Retrospective study | Bakoulev Center for Cardiovascular Surgery, Moscstyle="background-color: #D9D9D9" ow, Russia | 17 (2-32) months | 8 | 13.5 (5-154) months | N/A | Surgical | Pulmonary hypertensive crisis (2), heart failure (1), death (2) |

| 7 | Kirkpatrick et al (2018) | Retrospective study | Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, United States | 351 (244-441) days | 3 | 20.7 ± 5.7 years | N/A | Surgical (1), Transcatheter (2) | Significant hemorrhage, pulmonary contusion, and respiratory failure (1) |

N/A, not available.

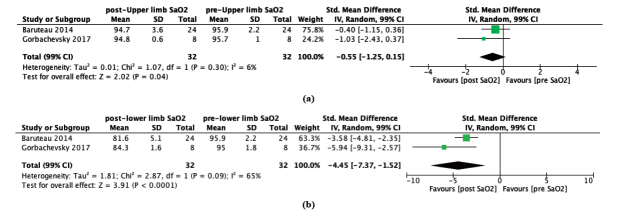

3.3. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on Upper Limb SaO2

Upper limb SaO2 of most patients with suprasystemic PAH were not significantly influenced by the reversed the Potts shunt procedure [2, 8] (2 studies, Std. mean difference -0.55, 99% CI -1.25 to 0.15; P=0.04; I2 = 6%); Fig. (3A). Studies conducted by Gorbachevsky et al. (2017) demonstrated a negligible change of preprocedural upper limb SaO2 from 95.7 ± 1.0% to 94.8 ± 0.6% after Potts shunt procedure. In the follow-up period, the values returned to their initial upper limb SaO2 of 95.6 ± 1.2% [8]. Furthermore, the other study by Baruteau et al (2014) showed a minimal lowering of preprocedural upper limb SaO2 from 95.9 ± 2.2% to postprocedural of upper limb SaO2 of 94.7 ± 3.6%, respectively [2].

Fig. (3).

Forest plot of random-effect model for the preprocedural and postprocedural conditions of (a) upper limb oxygen saturation, and (b) lower limb oxygen saturation. CI: Confidence Interval.

3.4. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on Lower Limb SaO2

In contrast to upper limb SaO2, lower limb SaO2 were remarkably reduced following Potts shunt procedure [2, 8] (2 studies, Std.mean difference -0.55, 99% CI -1.25 to 0.15; P=0.04; I2 = 6%; Fig. 3a (2 studies, Std. mean difference –4.45, 99% CI –7.37 to -1.52; P < 0.0001; I2 = 65%; Fig. 3b). The consequence of prominent lower limb arterial oxygen desaturation was portrayed by Baruteau et al (2014) from 96.9 ± 2.2% to 81.6 ± 5.1% [2]. The same result was also presented as a decline of preprocedural lower limb SaO2 from 95.0 ± 1.8% to postprocedural lower limb SaO2 of 84.3 ± 1.6% in a study conducted by Gorbachevsky et al (2017), respectively. Fortunately, these lower limb arterial saturations slightly improved to 85.0 ± 2.9% during the follow-up time [8].

3.5. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on SaO2 Upper/Lower Limb Gradient

Most of the included studies showed a pronounced SaO2 upper/lower limb gradient because of reversed Potts shunt procedure in patients with suprasystemic PAH (Table 2). Initially, neither SaO2 on the upper limb nor lower limb indicated a different value [2, 3, 8]. Nevertheless, the subsequent intervention manifests as SaO2 upper/limb gradient of .2 ± 5.2% and 10.5 ± 1.8% according to studies by Baruteau et al. (2014) and Gorbachevsky et al. (2017) [2, 8]. The SaO2 differences, as stated by Gorbachevsky et al (2017), tended to be slightly increased in the follow-up period to 10.7 ± 2.6%, respectively [8].On the other hand, other studies observed declining oxygen saturation gradients. Grady et al (2016) reported a decrease in postprocedural SaO2 upper/lower limb gradient from 12.4 ± 5.9% to 9.8 ± 3.8% in the follow-up time [10]. The least arterial oxygen saturation difference of the patients in the follow-up period, 7 (0-20) %, was reported by Boudjemline et al. (2017) [3]. Unfortunately, there was not enough information presented by Aggarwal et al. (2018) for preprocedural and postprocedural SaO2 upper/lower limb gradient to compare those parameters to a saturation difference of 13 (2-22) % on the follow-up [7].

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory outcomes of the included studies.

| No | Study (Year) | Upper Limb SaO2 (%) | Lower Limb SaO2 (%) | SaO2 Upper/Lower Limb Gradient (%) | WHO Functional Class | 6-minute Walking Test (m) | NT-pro BNP (pg/mL) | ||||||||||||

| pre | post | follow up | pre | post | follow up | pre | post | follow up | pre | post | follow up | pre | post | follow up | pre | post | follow up | ||

| 1 | Aggarwal et al (2018) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13 (2-22%) | 3.33 ± 0.65 | 2.37 ± 0.74 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | Baruteau et al (2014) | 95.9 ± 2.2 | 94.7 ± 3.6 | N/A | 95.9 ± 2.2 | 81.6 ± 5.1 | N/A | 0 | 13.2 ± 5.2 | N/A | Median: 4 (2-4) | Median: 2 (1-3) | N/A | 260.2 ± 85.1 | 522.6 ± 93.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | Bobhate et al (2021) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.75 ± 0.43 | N/A | 3.88 ± 0.33 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4947 (1143-13204) | N/A | 1106 (389-14327) |

| 4 | Boudjemline et al (2017) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | 7 (0-20) | 3 (3-4) | N/A | 1 (1-2) | 399 (200-478) | N/A | 469 (371-551) | 163 (77-4465) | N/A | 125 (71-730) |

| 5 | Grady et al (2016) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12.4 ± 5.9 | 9.8 ± 3.8 | 4 | N/A | 2.5 ± 0.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1108.2 ± 818.9 | 968.2 ± 988.3 | 237 ± 65.6 |

| 6 | Gorbachevsky et al (2017) | 95.7 ± 1.0 | 94.8 ± 0.6 | 95.6 ± 1.2 | 95.0 ± 1.8 | 84.3 ± 1.6 | 85.0 ± 2.9 | 0 (0-4) | 10.5 ± 1.8 | 10.7 ± 2.6 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 135.3 ± 9.5* | 382.7 ±77.5* | 360.7 ± 66.3* | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | Kirkpatrick et al (2018) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.3 ± 0.6 | N/A | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 385.5 ± 78.5* | N/A | 360.7 ± 104.3 | 74 (BNP), 9000, 3340 | N/A | 2950 (556-3480) |

N/A, not available; NT-pro BNP; N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation

*Only included patients with available data

3.6. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on WHO Functional Class

Post-procedural and follow-up WHO Functional Class showed significant improvement from the pre-procedure state in most studies. Studies by Agarwal et al (2018) and Baruteau (2014) reported improvement from the pre-procedure functional class of III (II-IV) and IV (II-IV) to post-procedure FC of II (II-IV) and II (I-III) [2, 7]. Recovery of FC on clinical follow-up was also observed by Boudjemline et al (2017), Grady et al (2016), and Kirkpatrick et al (2017) with FC of I (I-II), 2.5 ± 0.9, and 2.5 ± 0.5 compared to the pre-procedural state of III (III-IV), IV, and 3.3 ± 0.6 [3, 9, 10]. Gorbachevsky et al (2017) revealed conversion from pre-procedure FC of 3.7 ± 0.5 to 1.4 ± 0.4. Clinical follow-up of the study demonstrated a slight decline of FC outcomes in the post-procedure condition where the FC became 1.6 ± 0.4 [8]. Nevertheless, Bobhate et al. (2021) noticed a small FC retrogression on clinical follow-up of 3.88 ± 0.33 in comparison to pre-procedure FC of 3.75 ± 0.43 [11].

3.7. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on 6 Minute-Walking Distance Outcome

All included studies revealed an increased 6 MWD in most patients. Baruteau et al (2014) reported improvement from pre-procedure 6 MWD of 260.2 ± 85.1 to post-procedure of 522.6 ± 93.2, respectively [2]. Studies by Boudjemline et al (2017) and Kirkpatrick et al. (2017) observed increasing of 6 MWD from 399 (200-478) m and 385.5 ± 78.5 m at pre-procedural state to 469 (371-551) and 393 (244-445) at follow-up time [3, 9]. Gorbachevsky et al (2017) showed positive development in 6 MWD of capable patients of 132 (128-146) m, 411 (295-442) m, 335 (311-436) m before the intervention, after intervention, and on clinical follow-up time, respectively. However, the third patient in the study experienced regression from 442 m to 335 m [8].

3.8. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on NT-pro BNP Level

Reversed Potts shunt promoted reduced NT-pro BNP level in most studies. Bobhate et al (2021) and Boudjemline et al (2017) showed improvement in NT-pro BNP levels from 4947 (1143-13204) and 163 (77-4465) preoperatively to 1106 (389-14327) and 125 (71-730) at clinical follow-up time [3, 11]. A study by Kirkpatrick et al (2017) reported a decreased NT-pro BNP level in two patients from 9000 and 3340 to 3480 and 2950, respectively [9]. Grady et al (2016) observed a reduction of NT-pro BNP from 1108.2 ± 818.9 before the procedure to 968.2 ± 988.3 and 237 ± 65.6 post-procedure and on follow-up, respectively [10].

3.9. Effect of Reversed Potts Shunt on Hemodynamic Parameters

Most studies reported improvement of hemodynamic parameters postprocedural or after follow-up in the patients who had undergone reversed Potts shunt procedures (Table 3). Aggarwal et al (2018) and Bobhate et al (2021) reported decreased levels of MPAP, from 85.7 ± 17.2 mmHg to 75 ± 4.5 mmHg and 79.5 (66.8-89.0) mmHg to 75 (44-89) mmHg, respectively [7, 11]. A study by Gorbachevsky et al (2017) reported improved systolic RV pressure after the reversed Potts shunt procedures [8]. However, Aggarwal et al (2018) reported no improvement in systolic RV pressure in the patients [7]. TAPSE Z score was improved from -3.9 ± 1.3 to -1.3 ± 1.5 and from -2.1 (-2.8-1.1) to 0.3 (-1.5-2.6) in Bobhate et al (2021) and Boudjemline et al (2017), respectively [3, 11]. Aggarwal et al (2018) also reported slight improvement from 11.5 (10.4-12.4) mm to 12.6 (11.7-13.8) mm in postprocedural [7]. There was also an improvement in the interventricular septal curvature from the initial inverted or concave towards the LV to flattening of the septal curvature [8]. Gorbachevsky et al (2017) reported decreased end-diastolic RV/LV diameter ratio from 1.5 ± 0.3 to 0.68 ± 0.1 postprocedural and from 1.36 ± 0.14 to 0.99 ± 0.22 postprocedural and 0.90 ± 0.30 on follow-up, respectively [2, 8].

Table 3.

The assessment of hemodynamic parameters of the included studies.

| No | Study (Year) | MPAP (mmHg) | Systolic RV Pressure (mmHg) | TAPSE | Interventricular Septal Curvature | End-diastolic RV/LV Diameter Ratio | ||||||||||

| Pre | Post | Follow Up | Pre | Post | Follow Up | Pre | Post | Follow Up | Pre | Post | Follow Up | Pre | Post | Follow Up | ||

| 1 | Aggarwal et al (2018) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 81(71-98) | 81 (77-99) | N/A | 11.5 (10.4-12.4) | 12.6 (11.7-13.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | Baruteau et al (2014) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Inverted | Flattened | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | Bobhate et al (2021) | 79.5 (66.8-89.0) | N/A | 75 (44-89) | N/A | N/A | N/A | -3.9 ± 1.3 | N/A | -1.3 ± 1.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | Boudjemline et al (2017) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | -2.1 (-2.8 - 1.1) | N/A | 0.3 (-1.5 - 2.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 5 | Grady et al (2016) | 53 (51-87) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | Gorbachevsky et al (2017) | 86.6 ± 11.9 | N/A | N/A | 109.7 ± 9.4 | 98.7 ± 9.3 | 99.5 ± 8.6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.36 ± 0.14 | 0.99 ± 0.22 | 0.90 ± 0.30 |

| 7 | Kirkpatrick et al (2018) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 116 ± 21.7 | 130* | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Flattened | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

LV, left ventricle; MPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; N/A, not available; RV, right ventricle; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

*Only included patients with available data

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Clinical Outcomes of Reversed Potts Shunt

Despite the rapid advancement in the medical treatment of pulmonary hypertension, there are still congenital heart disease patients who progressed to right ventricular failure, recurrent syncope, and even death [12, 13]. Reversed Potts shunt, which connects the aorta with the left pulmonary artery, aims to decompress the right heart while elevating systemic cardiac output [14]. Theoretically, the shunting of desaturated blood from the pulmonary circulation to the systemic circulation could lead to differential cyanosis and induced polycythaemia [15]. It was proven by two included studies that demonstrated a significant decrease in postprocedural lower extremity saturation [2,8]. In our meta-analysis, upper limb oxygen saturation showed no significant reduction(2 studies, Std. mean difference -0.55, 99% CI -1.25 to 0.15; P=0.04; I2 = 6%), while lower limb oxygen saturation decreased remarkably (2 studies, Std. mean difference -4.45, 99% CI –7.37 to –1.52; P < 0.0001; I2 = 65%). Oxygen saturation, particularly during the 6-minute walk distance test, is an independent prognostic marker in PAH patients [16].

Unlike atrial septostomy, since the connection of reversed Potts shunt was made on the descending aorta, blood oxygen desaturation should not manifest on the upper extremity (representing coronary and cerebral circulation) [17]. This presumption was convinced by two included studies that showed only a slight decrease in the upper extremity saturation following reversed Potts shunt procedure [2, 8]. However, the reversed Potts shunt could still produce both upper and lower limb hypoxemia. The combination of hypoxemia with a recurrent pulmonary hypertensive crisis should be a consideration to narrow the reversed Potts shunt [8, 18]. Other consequences of the intervention included a noticeable postprocedural upper/lower limb saturation gradient [2, 8]. Boudjemline et al (2017) also reported a more pronounced saturation difference between the upper and lower limb at maximal exercise compared to the resting conditions [3].

Patients with suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension (PH) are classified into four functional classes (FC) in the WHO classification based on the impact of the disease on their life [19-21]. The higher the number of WHO FC, the more severe the disease [22]. Improvement of the FC has been observed in PH patients who underwent reversed Potts shunt. Post-procedural and follow-up FC of patients in most reversed Potts studies were significantly recovered compared to pre-operative states [2, 3, 7-10, 23, 24]. This is an expected result of hemodynamic improvement after the reversed Potts shunt procedure. However, Bobhate et al. found a small decline in follow-up FC compared to pre-operative conditions [11]. Moreover, follow-up FC is slightly increased in comparison to the post-operative state [8].

A six-minute walk test is commonly used to assess the exercise limitations of PH patients [21, 25, 26]. The output of this test, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), could predict the prognosis of the PH [27]. A study by Souza et al showed a better long-term prognosis in patients with 6MWD of more than 400m. However, changes in 6MWD are not associated with long-term outcomes of PH [28]. The reversed Potts shunt resulted in amelioration of the exercise ability of PH patients. Post-operative 6MWD was significantly improved in comparison to pre-operative states [2, 8]. Clinical follow-up of capable patients also showed improvement of 6MWD compared to the pre-operative condition [3, 8, 9].

4.2. Laboratory and Hemodynamic Improvement of Reversed Potts Shunt

NT-proBNP is utilized as a biomarker in assessing RV dysfunction and an outcome predictor of PH [21, 29, 30]. A concentration of NT-proBNP above the 97th percentile revealed PH with 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity [31]. Available data from included studies revealed decreased NT-proBNP levels after reversed Potts shunt procedure [10]. In addition, patients had a lower level of NT-proBNP in follow-up time compared to preoperative and postoperative values [9-11]. This outcome can be explained by the reduced work stress of the heart after the creation of the reversed Potts shunt, thus resulting in a reduction of NT-proBNP secretion.

Hemodynamic parameters assessed with echocardiography or cardiac catheterization (MPAP, systolic RV pressure, TAPSE, interventricular septal curvature, end-diastolic RV/LV diameter ratio) were improved after the reversed Potts shunt procedure. These hemodynamic parameters have been shown to predict the clinical outcomes in adult and pediatric patients with pulmonary hypertension. Decreased MPAP and systolic RV pressure are associated with increased survival in pulmonary hypertension patients [32]. TAPSE, a parameter of RV function, is correlated strongly with RVEF. Therefore, an increase in the TAPSE shows an improvement in RV function [33]. Interventricular septal curvature is also a useful marker of structural, hemodynamic, and electromechanical as well as ventricular interdependence in patients with right heart diseases including pulmonary hypertension [34]. Decreased RV end-diastolic volume and increased LV end-diastolic volume indicate better survival in these patients [32]. Therefore, these hemodynamic improvements can be correlated with the clinical improvement after the reversed Potts shunt procedure.

4.3. Complication and Mortality of Reversed Potts Shunt

Despite the lower risk of complications compared to the lung transplantation procedure, reversed Potts shunt is an invasive procedure [35]. Its complications ranged from chylothorax, tracheal stenosis, significant upper limb desaturation, bilateral lung transplantation, and death [2, 7]. Four deaths occurred in the study by Bobhate et a.l because of intolerable pulmonary artery clamping and pulmonary haemorrhage with respiratory failure [11]. Other complications of reversed Potts shunt include cardiac arrest after the anesthetic procedure and irreversible brain damage [3], pulmonary hypertensive crisis, and heart failure [8]. A study by Kirkpatrick reported no complications in the transcatheter procedure, while a patient that underwent the surgical procedure experienced heavy bleeding and respiratory failure [9]. Nevertheless, there is no postoperative complication in the five left thoracotomy Potts shunts conducted by Grady et al. [10].

In our included studies, we noted 13 deaths in total from 73 patients who underwent the reversed Potts shunt procedure. Most of the deaths were caused by low cardiac output with two of them developing subsequent cardiac arrest and irreversible brain damage [2, 3]. Heart failure was recorded in 2 patients [7, 8], while other deaths were caused by a severe pulmonary hypertensive crisis and adenoviral pneumonia [7, 8]. The mortality risk factor was associated with some preoperative data. A high preoperative pulmonary artery to aorta mean pressure ratio was also suggested to have a connection with patient deaths [8]. Furthermore, the operative mortality of the reversed Potts shunt procedure was higher compared to a lung transplant (20% vs. 6%), although both did not have significant survival differences [35].

5. LIMITATIONS

The studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were mostly retrospective cohort studies which consisted of a small number of subjects and a limited duration of follow-up. The initial baseline characteristics of the patients were different in each study, which reduces the comparability between studies. Furthermore, different primary and secondary outcomes resulted in inadequate data on some of the clinical, laboratory, and hemodynamic parameters, and thus could not be included in the meta-analysis.

CONCLUSION

Reversed Potts shunt cannot be said to be relatively safe, although it allows improvement in the clinical and functional status in patients with suprasystemic PAH. These changes were reflected in the improvement of laboratory and hemodynamic parameters including RV function, which can be markers for better survival. Reversed Potts shunt procedure may be the last resort for drug-resistant pulmonary hypertension as it is considered a high-risk procedure performed on patients with extremely poor conditions. Further studies are necessary to determine the sustainability of these improvements in the long term and to establish a better approach for these procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all those who have supported them in the making of this systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors are especially grateful to the Department of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, for their guidance in teaching them about research methodology, as well as their assistance in the proofreading of this article.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- PAH

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- CI

Confidence Interval

- SD

Standard Deviation

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines have been followed for this study.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenzweig E.B., Abman S.H., Adatia I., et al. Paediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: Updates on definition, classification, diagnostics and management. Eur. Respir. J. 2019;53(1):1801916. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01916-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baruteau A.E., Belli E., Boudjemline Y., et al. Palliative potts shunt for the treatment of children with drug-refractory pulmonary arterial hypertension: Updated data from the first 24 patients. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2015;47(3):e105–e110. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudjemline Y., Sizarov A., Malekzadeh-Milani S., et al. Safety and feasibility of the transcatheter approach to create a reverse Potts shunt in children with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017;33(9):1188–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group T.P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manager R. (RevMan) [Computer program] The Cochrane Collaboration. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggarwal M., Grady R.M., Choudhry S., Anwar S., Eghtesady P., Singh G.K. Potts shunt improves right ventricular function and coupling with pulmonary circulation in children with suprasystemic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018;11(12):e007964. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.007964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorbachevsky S.V., Shmalts A.A., Barishnikova I.Y., Zaets S.B. Potts shunt in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension: Institutional experience. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2017;25(4):595–599. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivx209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkpatrick E.C., Handler S.S., Foerster S., Gudausky T., Tillman K., Mitchell M. Single center experience with the Potts shunt in severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2018;48:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2017.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grady R.M., Eghtesady P. Potts shunt and pediatric pulmonary hypertension: What we have learned. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016;101(4):1539–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bobhate P., Mohanty S.R., Tailor K., et al. Potts shunt as an effective palliation for patients with end stage pulmonary arterial hypertension. Indian Heart J. 2021;73(2):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zelt J.G.E., Chaudhary K.R., Cadete V.J., Mielniczuk L.M., Stewart D.J. Medical therapy for heart failure associated with pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res. 2019;124(11):1551–1567. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenkranz S., Howard L.S., Gomberg-Maitland M., Hoeper M.M. Systemic consequences of pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure. Circulation. 2020;141(8):678–693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schranz D., Akintuerk H., Voelkel N.F. ‘End-stage’ heart failure therapy: Potential lessons from congenital heart disease: From pulmonary artery banding and interatrial communication to parallel circulation. Heart. 2017;103(4):262–267. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanc J., Vouhé P., Bonnet D. Potts shunt in patients with pulmonary hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350(6):623–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200402053500623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos M., Furtado I., Goncalves F., Carvalho L., Reis A. Prognostic impact of oxygen saturation during the 6-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;48(Suppl. 60):PA2405. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delhaas T., Koeken Y., Latus H., Apitz C., Schranz D. Potts shunt to be preferred above atrial septostomy in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension patients: A modeling study. Front. Physiol. 2018;9(SEP):1252. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latus H., Apitz C., Moysich A., et al. Creation of a functional Potts shunt by stenting the persistent arterial duct in newborns and infants with suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension of various etiologies. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(5):542–546. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.01.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corris P., Degano B. Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension: Treatment options and the bridge to transplantation. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2014;23(134):488–497. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivy D. Pulmonary hypertension in children. Cardiol. Clin. 2016;34(3):451–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammers A.E., Apitz C., Zartner P., Hager A., Dubowy K.O., Hansmann G. Diagnostics, monitoring and outpatient care in children with suspected pulmonary hypertension/paediatric pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease. Expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of paediatric pulmonary hypertension. The European paediatric pulmonary vascular disease network, endorsed by ISHLT and DGPK. Heart. 2016;102(Suppl. 2):ii1–ii13. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galiè N., Hoeper M.M., Humbert M., et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;34(6):1219–1263. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00139009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorbachevkiy S.V., Shmal’ts A.A., Belkina M.V., Grenaderov M.A., Baryshnikova I.Y., Pursanov M.G. Potts shunt in children with pulmonary hypertension: 7 operations in one clinic and review of world experience. Det Bolezn Serdtsa i Sosudov. 2016;13(4):189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baruteau A.E., Serraf A., Lévy M., et al. Potts shunt in children with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: Long-term results. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012;94(3):817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deboeck G., Niset G., Vachiery J.L., Moraine J.J., Naeije R. Physiological response to the six-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26(4):667–672. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00031505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin L.J. The 6-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension: How far is enough? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;186(5):396–397. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1137ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demir R., Küçükoğlu M.S. Six-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2015;15(3):249–254. doi: 10.5152/akd.2015.5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Souza R., Channick R.N., Delcroix M., et al. Association between six-minute walk distance and long-term outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: Data from the randomized SERAPHIN trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berghaus T.M., Kutsch J., Faul C., von Scheidt W., Schwaiblmair M. The association of N-terminal pro-brain-type natriuretic peptide with hemodynamics and functional capacity in therapy-naive precapillary pulmonary hypertension: Results from a cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017;17(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chin K.M., Rubin L.J., Channick R., et al. Association of N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide and long-term outcome in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2019;139(21):2440–2450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casserly B., Klinger J.R. Brain natriuretic peptide in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Biomarker and potential therapeutic agent. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2009;3:269–287. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badesch D.B., Champion H.C., Gomez Sanchez M.A., et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54(1) Suppl.:S55–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu V.C.C., Takeuchi M. Echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular systolic function. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018;8(1):70–79. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2017.06.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haddad F., Guihaire J., Skhiri M., et al. Septal curvature is marker of hemodynamic, anatomical, and electromechanical ventricular interdependence in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Echocardiography. 2014;31(6):699–707. doi: 10.1111/echo.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lancaster T.S., Shahanavaz S., Balzer D.T., Sweet S.C., Grady R.M., Eghtesady P. Midterm outcomes of the potts shunt for pediatric pulmonary hypertension, with comparison to lung transplant. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021;161(3):1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.10.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.