Abstract

The anabolic response of aged bone to skeletal loading is typically poor. Efforts to improve mechanotransduction in aged bone have met with limited success. This study investigated whether the bone response to direct skeletal loading is improved by reducing sympathetic suppression of osteoblastic bone formation via β2AR. To test this possibility, we treated aged wild‐type C57BL/6 mice with a selective β2AR antagonist, butaxamine (Butax), before each of nine bouts of cantilever bending of the right tibia. Midshaft periosteal bone formation was assessed by dynamic histomorphometry of loaded and contralateral tibias. Butax treatment did not alter osteoblast activity of contralateral tibias. Loading alone induced a modest but significant osteogenic response. However, when loading was combined with Butax pretreatment, the anabolic response was significantly elevated compared with loading preceded by saline injection. Subsequent studies in osteoblastic cultures revealed complex negative interactions between adrenergic and mechanically induced intracellular signaling. Activation of β2AR by treatment with the β1, β2‐agonist isoproterenol (ISO) before fluid flow exposure diminished mechanically stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary bone cell outgrowth cultures and AKT phosphorylation in MC3T3‐E1 pre‐osteoblast cultures. Expression of mechanosensitive Fos and Ptgs2 genes was enhanced with ISO treatment and reduced with flow in both MC3T3‐E1 and primary cultures. Finally, co‐treatment of MC3T3‐E1 cells with Butax reversed these ISO effects, confirming a critical role for β2AR in these responses. In combination, these results demonstrate that selective inhibition of β2AR is sufficient to enhance the anabolic response of the aged skeleton to loading, potentially via direct effects upon osteoblasts. © 2022 The Authors. JBMR Plus published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Keywords: BONE‐BRAIN‐NERVOUS SYSTEM INTERACTIONS, EXERCISE, OSTEOBLASTS, PRECLINICAL STUDIES, TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS

Introduction

The anabolic response of bone to skeletal loading declines with age.( 1 ) Numerous age‐related bone cell deficits have been identified, including diminished osteoblast function( 2 , 3 ) increased osteocyte apoptosis,( 3 ) a reduced osteoprogenitor pool,( 4 ) fewer periosteal lining cells,( 5 ) and a decreased calcium response to fluid flow.( 6 ) Additionally, systemic inhibitors are also likely to contribute to age‐related mechanotransduction deficits (eg, elevated serum sclerostin( 7 )). Despite these insights, the barriers preventing a robust osteogenic response from modest exercise in the elderly have not been overcome.

Anatomical studies reveal abundant sympathetic innervation in the periosteum of rodent long bones,( 8 ) with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactive fibers associated with blood vessels( 9 ) in the outer portion of the cambial layer.( 10 ) TH‐positive sympathetic nerve fibers have also been detected within diaphyseal cortical bone using fluorescent reporter mice.( 11 ) Aging does not alter the general morphology and organization of TH‐positive sympathetic innervation in mouse femora, but periosteal thinning in aged bone leads to increased sympathetic density despite a decrease in TH‐positive fiber numbers.( 12 ) Numerous other aspects of sympathetic regulation are also altered by age, including elevated plasma catecholamine,( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ) sympathoadrenal changes,( 19 , 20 , 21 ) increased central sympathetic drive,( 16 , 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ) impaired peripheral clock entrainment due to sympathetic dysfunction,( 31 ) and increased norepinephrine content in cortical bone.( 11 ) In this context, and given our interest in cross‐talk between bone, muscle, and nerve,( 32 ) we posited elevated sympathetic tone in the aged as a potential underexplored contributor to the diminished osteoblastic response to skeletal loading in the aged.

We therefore sought to directly investigate the role of the β2AR in the in vivo osteoblastic response to skeletal loading and the in vitro response to fluid flow by transient pharmacological blockade using the β2AR‐selective antagonist Butax. This drug was chosen for the present study based on its augmentation of osteoblast activity in hypertensive rats( 33 ) and its low penetrance at the blood‐brain barrier.( 34 ) Specifically, we evaluated the osteoblastic response of aged wild‐type C57BL/6 mice to tibia cantilever bending treatment. In addition, we characterized signaling responses to fluid flow stimulation of mouse primary osteoblast outgrowth and pre‐osteoblast MC3T3‐E1 cell line cultures with and without β‐adrenergic receptor agonist treatment.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments and protocols were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol no. 3306‐02) and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” guidelines (NIH publication No. 96‐23, 1996). Aged female C57BL/6 N mice (21 months) were obtained from the NIH/National Institute of Aging aged rodent colony (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). All animals were group‐housed in a SPF vivarium and acclimatized to local conditions (22°C room temperature, 14‐hour light /10‐hour dark cycle) for at least 1 month before experimentation and permitted standard commercial mouse chow and water ad libitum throughout.

Chemicals and drugs

Isoproterenol (cat. no. I5627), butaxamine HCl (cat. no. B1385) and calcein (cat. no. C0875) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). ISO stock was prepared fresh on each treatment day. Butax master stock (12.5 mg/mL in sterile physiologic saline) was stored in aliquots at −20°C and freshly diluted in sterile saline as needed. Tissue culture medium and supplements were purchased from Life Technologies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Media was supplemented with heat‐inactivated FBS (HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Imaging

Before experimentation, high‐resolution μCT images of the right tibia were obtained for all mice (Scanco vivaCT40; Scanco Medical, Bruttisellen, Switzerland; 10.5 μm voxel size, 55 kVp, 145 μA), and animal‐specific longitudinal normal strains induced by the loading protocol were determined via beam theory using individualized midshaft morphology.( 35 )

In vivo loading protocol and tissue collection

Mice were randomly assigned to groups (n = 8/group) for treatment with saline or Butax (1.0, 3.0, or 10.0 mg/kg, i.p.). Experiments were conducted between 12 p.m. and 6 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays for 3 weeks (9 bouts total). Animals were weighed on each loading day, then acclimated quietly for at least 1 hour in covered cages to reduce stress. Each mouse received Butax or saline treatment, and 30 minutes later was anesthetized (0.2% isoflurane) and the right tibia loaded in cantilever bending using a noninvasive murine tibia‐loading device.( 36 ) Each loading intervention consisted of 50 cycles (1 Hz) calibrated to induce peak longitudinal normal strain of 1700 με at the tibia midshaft. All mice received calcein (10 mg/kg, i.p.) on days 10 and 19, then were euthanized on day 22. Two mice (one each from saline and 10 mg/kg groups) were euthanized and excluded from analyses when excessive weight loss was detected, per IACUC protocol. Loaded (right) and contralateral (left) tibias were dissected free of soft tissue and 500‐μm‐thick sections were obtained at the location where strain measurements were calculated. Sections were then hand‐ground to 125 μm, cover‐slipped, and imaged via epifluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axio Imager.M2 epifluorescent microscope, Zeiss, White Plains, NY, USA). As previously described,( 37 ) composite images were assembled, anatomically oriented, and blinded for subsequent analysis. Custom NIH ImageJ based software was used to quantify mineral apposition rate (MAR, μm/d), mineralizing surface (MS/BS%), and bone formation rate (BFR, μm3/μm2/d) at the periosteal surface.

RNA preparation and quantitative RT‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), and quantitative RT‐PCR was performed using SYBR green and the Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA, USA) ViiA7 sequence detection system. Primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table S1. Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the 2(−ΔΔCT) method using β‐actin as housekeeping gene.

Cell culture and fluid flow

Primary outgrowth bone cultures were prepared from marrow‐depleted tibial diaphyses of aged (22 months) female C57BL/6 mice. Bones from groups of 5 animals were pooled in two independent experiments. Cells that grew out of bone fragments in osteogenic culture medium (α‐MEM with 10% FBS, 2 mM L‐glutamine, 10 mM β‐glycerophosphate, 50 mg/mL ascorbic acid, and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin) were expanded and then seeded at passage 2 for experimentation. MC3T3‐E1 cells (subclone 14; ATCC [Manassas, VA, USA] cat. no. CRL‐2594) were cultured in α‐MEM with 10% FBS, 2 mM L‐glutamine, and 100 mM sodium pyruvate. For cell mechanical stimulation, we used a previously described in vitro fluid flow model of mechanotransduction.( 38 ) Seventy‐two hours before experimentation, cells were seeded at 2.5 × 104 cells/well into 6‐well plates in 2 mL of growth media. Eighteen hours before ISO treatment, cells were changed into growth media containing 0.5% FBS. On the day of flow exposure, cells were treated with ISO or Butax and transferred to an orbital shaker (VWR [Radnor, PA, USA], DS‐500) placed in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2, 30 minutes before exposure to fluid flow. Cells were subjected to orbital shaking (2.2 Hz, 0.1–0.5 Pa) and harvested for RNA after 1 hour of fluid flow or for protein analysis at 5 or 10 minutes after the start of flow.

Antibodies and immunoblotting

Total protein was isolated from cells in RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP‐40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) and quantitated using BCA protein assay reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific), then separated on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis‐Tris gels (Life Technologies) and transferred to Immobilon‐FL membrane (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). Blots were stained using REVERT Total Protein Stain solution (LI‐COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) and probed with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Antibodies are detailed in Supplemental Table S2. Bound primary antibodies were detected using DyLight 680 and 800 labeled secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:15,000) and scanned and quantified using the Odyssey (LI‐COR). Where possible, phospho‐ and total protein antibodies from different host species were used at the same time to image dual fluorescent signals. When not possible, or to examine other signaling proteins, blots were stripped with Restore Fluorescent Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then reprobed. Quantified values for each signaling molecule on individual membranes were normalized to the associated no‐flow, no‐ISO value at the earliest time point on that membrane.

Statistical analysis

Sample size for in vivo studies was determined by power analysis for a 20–40% difference,( 39 ) assuming α = 0.05 (based on results from our previous studies( 40 ) and the literature( 41 )). All data analyses were performed in R (http://www.R-project.org/). Mouse group weights and loading‐induced peak strains were analyzed via ANOVA. Body weight changes over the experiment were evaluated per group by repeated measures ANOVA. Non‐parametric statistics were used for histomorphometric assessment of bone response to mechanical loading. Kruskal–Wallis tests with Mann–Whitney follow‐ups (where appropriate) were used to determine if outcome measures differed across groups, and Wilcoxon's rank‐sum tests to contrast outcomes in loaded versus contralateral bones. Quantified Western blot and RT‐PCR data from in vitro experiments were analyzed via two‐ or three‐way ANOVA as indicated, with Bonferroni post hoc tests implemented as appropriate. Statistical comparisons are indicated in the figure legends. For all tests, p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Butax pretreatment of aged mice enhanced the osteoblastic response to skeletal loading in aged mice

We used in vivo skeletal loading and dynamic histomorphometry to examine the influence of Butax treatment on the anabolic response to mechanical loading. Baseline body mass and peak normal strain induced in the loaded (right) tibias did not differ across experimental groups (Table 1). Body weight significantly declined 3.3 ± 0.7% over the course of the study (p < 0.0001), but Butax dosage had no effect (p = 0.78) and interaction between study time course and dosage was not significant (p = 0.5; Fig. 1). No significant differences in contralateral tibias p.MAR, p.MS., or p.BFR were observed across experimental groups. When contrasted with contralateral tibias, p.MAR was significantly elevated by skeletal loading in the saline (0 mg/kg, p = 0.02), low‐dose (1 mg/kg, p = 0.01), and high‐dose (10 mg/kg, p = 0.02) Butax groups (Fig. 2). In contrast, p.MS was significantly elevated versus contralateral tibias only in Butax‐treated groups (low dose, p = 0.02; medium dose [3 mg/kg], p = 0.01; high dose, p = 0.03; saline, p = 0.47). Finally, p.BFR was significantly increased in the loaded tibias of each Butax‐treated group versus contralateral tibias (low dose, p = 0.01; medium and high doses, each p = 0.02), but not in the saline group (p = 0.22). As a result, p.BFR was significantly increased in the loaded tibias of the low‐ (p = 0.01), medium‐ (p = 0.04), and high‐dose (p = 0.04) Butax‐treated groups versus the loaded tibias of saline‐treated mice, but no differences were observed across the Butax dose range.

Table 1.

Baseline Weights and Strain Values Did Not Differ Among Dosage Groups

| Butax dose (mg/kg) | 0 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| Body mass (g) | 31.6 ± 1.8 | 30.2 ± 1.4 | 30.5 ± 2.0 | 28.8 ± 1.1 |

| Peak normal strain (με) | 1886.4 ± 73.6 | 1842.8 ± 84.5 | 1876.5 ± 101.3 | 1883.3 ± 72.8 |

| Sample no. | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

Fig. 1.

Butax treatment did not alter the decline in body mass in senescent mice. Mice exhibited a decline in body weight over the course of the study (p < 0.0001), but dosage had no effect (p = 0.78) and the interaction between study time course and dosage was not significant (p = 0.51).

Fig. 2.

Butax treatment enhanced mechanically induced bone formation across a range of dosages. Periosteal mineral apposition rate (MAR) (A), mineralizing surface (MS) (B), and bone formation rate (BFR) (C) are plotted for loaded (red dots) and contralateral bones (black dots). Representative images (D) of contralateral and loaded tibias from saline and Butax‐treated mice (3 mg/kg dosage), each approximating the mean p.BFR of the specified group. Corresponding group mean values are listed below images. Single‐ and double‐labeled periosteal surfaces are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. Graphed data are from n = 7–8 mice in the 0, 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg (low, medium, and high) dose groups, respectively. Kruskal–Wallis test comparison across dosages for each limb identified significant dosage effect on p.BFR of loaded limb (p < 0.03). Mann–Whitney test compared each Butax dosage versus saline for this parameter (p < 0.05; aButax versus saline, same limb). Wilcoxon's rank‐sum test contrasted outcomes in loaded versus contralateral bones (p < 0.05; bloaded versus contralateral limb).

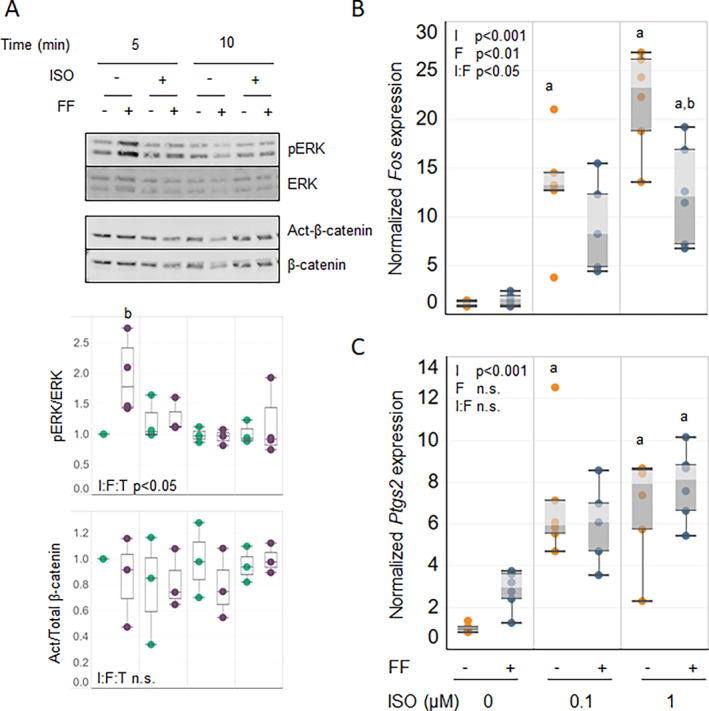

β2AR activation alters early mechanotransduction signaling in primary outgrowth bone cells

To evaluate β2AR modulation of signaling and gene expression in static and mechanically stimulated bone cells, we first investigated the effects of ISO on fluid flow responses in primary outgrowth bone cells from aged mice. These cultures expressed primarily osteoblastic markers, with negligible expression of osteocytic marker genes (Supplemental Fig. S1). Fluid flow increased pERK within 5 minutes, but this effect was muted with ISO pretreatment (Fig. 3A ). Neither flow nor ISO treatment altered levels of active β‐catenin at either time point. In these primary cultures, expression of the mechanosensitive gene Fos was not altered by flow alone. However, ISO treatment did cause significant elevation of Fos transcripts (Fig. 3B ), which was reduced by superimposition of flow. Ptgs2 mRNA was also significantly elevated with ISO treatment, but fluid flow did not change expression level of this gene (Fig. 3C ).

Fig. 3.

Isoproterenol (ISO) treatment selectively inhibits flow‐responsive signaling in primary outgrowth bone cells. Cells established from mice were pretreated with 0.1 or 1.0 μM ISO and subjected to fluid flow (FF). (A) Signaling events after flow were analyzed by Western blotting to detect ERK phosphorylation and canonical β‐catenin activation at the time points shown. Values of the normalized quantified signals are aligned below each relevant lane. Three‐way ANOVA was conducted to detect significance of ISO pretreatment (I), flow (F), and time (T) and the combination of these factors (I:F:T) on each signaling event. (B, C) After 1 hour under stationary (gold dots) or flow (blue dots) conditions, cells were analyzed for expression of mechanosensitive genes Fos (B) and Ptgs2 (C) relative to β‐Actin housekeeping gene by qRT‐PCR. Two‐way ANOVA analyses were performed to detect significance of ISO pretreatment (I) and flow (F), alone and in combination (I:F), for the expression of these genes. Western blot results are representative of 3 technical replicates. qRT‐PCR data are pooled from 2 replicate runs (n = 6). Post hoc analyses were used (p < 0.05; aversus no ISO; bversus no flow).

β2AR activation altered flow responses in osteoblastic MC3T3‐E1 cells

To further our understanding of the effects of β2AR on mechanotransduction in the primary cultures, we turned to more homogeneous cell models. As the primaries lacked a significant osteocytic phenotype, we first evaluated the effects of fluid flow and ISO pretreatment in MLO‐Y4 osteocytic cells. We detected no significant interactions between activation of β2AR and fluid flow in either signaling or transcriptional responses (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that the ISO responses observed in the primary cultures likely occurred in osteoblastic cells. Next, we treated MC3T3‐E1 cells with ISO before fluid flow exposure and investigated early flow responsive signaling pathways. Flow alone increased relative pCREB, pAKT, and pERK levels, but active β‐catenin did not change with flow (Fig. 4A ). ISO treatment alone did not significantly alter activation of the signaling pathways tested. However, in cultures also subjected to fluid flow, the β‐agonist did inhibit the mechanical stimulation of pAKT. In contrast, levels of pCREB, pERK, and active β‐catenin in cultures exposed to ISO plus flow did not differ from those with flow alone. Consistent with the primary outgrowth cultures, neither Fos (Fig. 4B ) nor Ptgs2 (Fig. 4C ) was elevated by fluid flow alone. However, pretreatment with ISO increased expression of both genes in the absence of flow. This elevated expression was significantly reduced when fluid flow was superimposed upon ISO pretreatment but remained elevated above the level of expression with flow alone.

Fig. 4.

Isoproterenol (ISO) selectively inhibits flow‐induced signaling and gene expression in MC3T3‐E1 cells. MC3T3‐E1 cells were pretreated with ISO at the concentrations shown and subjected to fluid flow (FF). (A) Phosphorylation of CREB, AKT, ERK, and canonical β‐catenin activation after flow were analyzed by Western blotting. Quantitative analysis of the blots is shown to the right. (B, C) after 1 hour under stationary (gold dots) or flow (blue dots) conditions, expression of mechanosensitive genes Fos (B) and Ptgs2 (C) was assessed by qRT‐PCR. Two‐way ANOVA analyses were performed to detect significance of ISO pretreatment (I), flow (F), and the combination of these factors (I:F), for the expression of these genes. Western blot results are representative of 3 independent experiments. qRT‐PCR data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n = 6). Post hoc analyses were used (p < 0.05; aversus no ISO; bversus no flow).

Co‐treatment of MC3T3‐E1 cells with β2AR antagonist Butax mitigated effects of ISO

To confirm that ISO effects on fluid flow‐induced signaling in MC3T3‐E1 cells were mediated via β2AR signaling, we explored co‐treatment with Butax. Qualitatively, elevation of pAKT by flow was lessened when superimposed with ISO treatment (Fig. 5A ). As expected, concurrent treatment with Butax tended to mitigate the ISO inhibitory effect on pAKT in the presence of flow, partially restoring the flow response despite exposure of the cells to ISO. In the parallel expression analysis, co‐treatment with Butax also reversed the ISO‐induced increase of Fos (Fig. 5B ) and Ptgs2 (Fig. 5C ) transcripts in a concentration‐dependent manner, with little effect on the flow‐induced decrease in ISO‐treated cells. Butax treatment did not alter levels of pCREB, pERK, or active β‐catenin when combined with ISO treatment, consistent with the lack of ISO effect on these signaling molecules in the earlier experiment.

Fig. 5.

Butax co‐treatment reverses isoproterenol (ISO)‐induced effects in MC3T3‐E1 cells. MC3T3‐E1 cells were pretreated with ISO and Butax at the concentrations shown and subjected to fluid flow (FF). (A) Phosphorylation of CREB, AKT, ERK, and canonical β‐catenin activation after flow was analyzed by Western blotting. Quantification of the blots is shown to the right, but the unbalanced study design and small group sizes precluded statistical analysis. (B, C) After 1 hour under stationary (gold dots) or flow (blue dots) conditions, cells were analyzed by qRT‐PCR for expression of mechanosensitive genes Fos (B) and Ptgs2 (C). Three‐way ANOVA analyses were performed to detect significance of ISO (I), flow (F), Butax (B), and the combination of these factors (I:F:B), for the expression of these genes. Post hoc analyses were used (p < 0.05; aversus no ISO; bversus no flow; cversus no Butax). Western blot results are representative of 3 independent experiments. qRT‐PCR data are pooled from 3 independent experiments (n = 3–9).

Discussion

Pretreatment of aged female mice with the β2AR‐selective antagonist Butax enhanced periosteal bone formation induced by direct skeletal loading but did not alter bone formation in contralateral tibias, suggesting that β2AR mitigation was not sufficient to enhance bone formation on its own. In vitro, the activation of β2AR by ISO treatment before fluid flow exposure differentially altered mechanically responsive signal transduction and early mechanosensitive gene expression in osteogenic cell cultures. Concurrent treatment with Butax reversed the signaling effects of ISO, supporting the role of β2AR in this response and highlighting potential mechanisms mediating Butax‐enhanced mechanotransduction in vivo.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate potential βAR‐antagonist modulation as a means to enhance the minimal response of the aged skeleton to mechanical loading. Previous explorations of the sympathetic modulation of bone cell responses to skeletal loading in young adult rodents, however, provide supportive context for our observation despite superficially conflicting data. Genetic studies in single and double null mutant male mice concluded that β1AR, but not β2AR, was required to increase periosteal bone formation after mechanical stimulation.( 41 ) In that study, however, periosteal mineral apposition rate of mechanically stimulated β2AR tibias was almost twice that of wild‐type littermates, which is consistent with our findings. In β2AR KO male mice of similar age, we have observed a smaller tibial cross section and reduced cortical moment of inertia versus littermate controls, which would result in increased peak normal strain, as loading magnitude was constant across groups.( 42 ) Thus, the enhanced loading response of the β2AR‐deficient tibias observed by Pierroz and colleagues could potentially have arisen by some combination of altered tibial morphology and an enhanced responsiveness to loading. Our finding that treatment with a β2AR‐selective antagonist enhanced the bone mechanical response in C57BL/6 female mice adds support for the latter mechanism.

Our findings with Butax contrast with pharmacologic studies in young adult mice, which suggested that after reduction of sympathetic signaling by a chemical or surgical approach, treatment with the β1, β2‐antagonist propranolol (PRO) did not alter the mechanical response of cortical bone.( 43 , 44 ) Our findings are consistent, however, with previous studies indicating that elevation of sympathetic tone may reduce the anabolic response of bone to loading. For example, sympathetic modulation of the bone mechanical response was evident after treatment of adult rats with the β2AR‐selective agonist salbutamol, which blocked an exercise‐induced increase in cortical bone formation.( 45 ) Additionally, bilateral lesion of the inner ear vestibula led to increased sympathetic outflow and a loss of bone mass in weight‐bearing bones due to reduced bone formation; this loss was prevented by PRO and by deletion of β2AR,( 46 ) consistent with the Butax effect we observed in aged mice. This parallel between elevation of sympathetic tone and anabolic effects of beta antagonists on the response of bone to mechanical stimuli may, in part, explain why the findings of the present study differ from those of previous investigations in which sympathetic tone was lowered. Other contributing factors could be aligned with our pharmacologic strategy. For example, selective affinity for β2AR and poor penetrance at the blood brain barrier( 34 ) would limit Butax effects to peripheral tissues, whereas PRO, which readily passes into the brain,( 47 ) could impact central as well as peripheral β1AR and β2AR activity.

Our detection of β2AR antagonist effects on the bone mechanical response was likely facilitated by our use of aged animals, as senescent rodents demonstrate higher sympathetic tone.( 13 , 19 , 46 ) Selective antagonism of β2AR also holds potential to enhance bone mechanotransduction more broadly, and this concept can be directly tested in younger adult mice. Another limitation of the present study is that Butax effects on bone mechanotransduction were not tested in male mice. Sympathetic restraint of bone mass was associated with a progressive increase in norepinephrine content of cortical bone in aging norepinephrine transporter (NET)‐deficient male mice.( 11 , 48 ) In addition, we have observed an enhanced periosteal response to mechanical stimulation in aged male β2AR‐deficient mice.( 42 ) Thus, although sex‐related differences in sympathetic regulation have been reported,( 49 , 50 ) the available evidence suggests that Butax treatment would also enhance the bone mechanical response in aged male C57BL/6 mice.

Butax treatment may relieve sympathetic suppression of mechanically stimulated osteoblast differentiation in vivo, as predicted by the findings of in vitro studies using PRO( 51 ) and ISO( 52 ) to manipulate β‐adrenergic activity in osteoblastic cultures. Mechanically stimulated calcium signaling is known to enhance osteoblast proliferation and differentiation through PI3K/AKT, ERK/Elk1, and CaMK/CREB signaling pathways.( 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ) Consistent with the Butax enhancement of the mechanical response of bone in vivo, our in vitro data demonstrate the potential for β2AR signaling to counter typical osteoblastic fluid flow responses, as ISO activation of β2AR signaling abolished flow responsive enhancement of pERK in primary cells and pAKT in MC3T3‐E1 cells, and Butax prevented the latter. Although it is well established that fluid flow shear stress can enhance expression of the early effectors Fos and Ptgs2 in osteoblasts,( 59 , 60 ) we did not see robust flow‐induced increases in expression of mechanoresponsive Fos and Ptsg2 in our cells. As we have previously observed flow responsive expression of these genes under the same experimental conditions,( 38 ) this deficit may be attributable to the low serum conditions used to optimize ISO responses in this study. Although ISO treatment greatly enhanced expression of both Fos and Ptgs2, consistent with previous reports,( 61 , 62 , 63 ) fluid flow reduced the ISO‐induced elevation. This unexpected finding suggests that mechanotransduction may interfere with β2AR‐activated transcription in osteoblastic cells.

We found that mechanically enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was inhibited by ISO treatment in primary, but not MC3T3‐E1, cultures. Our long bone osteogenic cultures from aged mice were predominately mature osteoblasts, whereas MC3T3‐E1 cells cultured in the absence of osteogenic stimuli are pre‐osteoblastic.( 64 ) This is consistent with a previous study demonstrating that juvenile mouse long bone primary cultures were at a later stage of osteoblast differentiation than neonatal calvarial cultures before in vitro differentiation.( 65 ) In another study, although mechanotransduction was comparable in primary bone cell cultures regardless of donor age or skeletal origin, neonatal cultures had a stronger biochemical response than adult cultures.( 66 ) By extension, these previous studies suggest that disparate signaling responses to the β‐agonist in our two culture models may be due to an age‐related influence on stage of osteoblast differentiation that determines biochemical responses to ISO, with the β2AR agonist blocking mechanically stimulated ERK1/2 activation in the pre‐osteoblasts but not the more mature cells. Future studies will explore this insight to determine whether β2AR expression, signaling, and interactions with mechanotransduction vary according to osteoblastic stage of differentiation.

In both osteoblasts and osteocytes, fluid flow has been reported to stabilize β‐catenin via the upstream inactivation of GSK3β, mediated by the activation of AKT.( 58 , 67 , 68 , 69 ) Given the essential role of Wnt signaling in osteoblasts and our observed loss of flow‐induced pAKT with ISO treatment, it is surprising that we did not see a change in active β‐catenin levels with either flow or ISO treatment. Activation and nuclear localization of β‐catenin in response to fluid shear stress has commonly been observed in osteoblastic cells after one or more hours of stimulation( 58 , 67 , 70 , 71 ) and under sufficient magnitude of shear stress.( 70 ) Thus, our short period of more modest fluid flow magnitude (2 dyn/cm2 versus 10 or 12 dyn/cm2 in the previously cited work) may not have been sufficient to replicate previous studies. It is possible that β2AR treatment could have an inhibitory effect on flow‐induced β‐catenin activation under more vigorous or prolonged flow conditions.

Induction of Fos( 72 ) and COX‐2( 73 ) expression are among the earliest activated mechanotransduction pathways in bone. Although this pattern has been reproduced in MC3T3‐E1 cells,( 59 ) we did not observe these increases in this study. In fact, exposure to shear stress dampened a positive β‐agonist effect on expression of Fos and Ptgs2 expression. In this regard, our in vitro results were not directly aligned with the enhanced anabolic response to mechanical stimulation in Butax‐treated mice. A similar lack of consistency between live animal and cell culture studies has been noted in the context of connexin 43 and mechanotransduction.( 74 ) Suggested reasons for that discrepancy included the use of two‐dimensional cell cultures and the experimental focus on only one mechanical signal,( 74 ) which would both apply here. The inconsistency may also relate to the mixture of mechanically responsive cell populations in skeletal tissue (osteobasts, osteocytes, and stromal cells) versus the predominantly osteoblastic cells in vitro. Finally, in addition to β2AR, mouse osteoblast lineage and stromal cells express α1AAR and α1DAR, and MC3T3‐E1 cells express α2AAR as well (reviewed by Elefteriou( 75 )). Thus, whereas β2AR is presumably the predominant responder to ISO in the cell culture studies, the α‐ARs in bone cells in vivo can also be activated by the endogenous catecholamine norepinephrine.

In summary, the anabolic response to mechanical loading of mouse tibias was enhanced at the periosteum by the β2‐antagonist Butax, but bone formation on the contralateral limb was unaffected. Butax treatment was associated with increased mineralizing surface but not mineral apposition rate. This result suggests that sympathetic output primarily reduces activation of the osteoblastic cell population by mechanical stimulation, with less impact on osteoblast function. The in vitro responses to flow and ISO were complex, varying with the signaling pathway investigated and the cell model employed. In sum, however, our data provide clear evidence for negative interactions between mechanically stimulated and active β2AR signaling. These findings support further explorations into the potential clinical benefit of selective β2AR antagonism as a therapeutic adjuvant to exercise.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential or real conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Leah Worton: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Sundar Srinivasan: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. DeWayne Threet: Investigation; validation. Brandon J Ausk: Validation; visualization; writing – review and editing. Phillipe Huber: Visualization; writing – review and editing. Ronald Kwon: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing. Steven D. Bain: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing. Ted S. Gross: Conceptualization; supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Edith Gardiner: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting information

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AR66710. This work was also supported by a UW Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine seed grant. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

LEW and SS contributed equally to this work.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request from the authors.

References

- 1. Srinivasan S, Gross TS, Bain SD. Bone mechanotransduction may require augmentation in order to strengthen the senescent skeleton. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11(3):353‐360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meakin LB, Galea GL, Sugiyama T, Lanyon LE, Price JS. Age‐related impairment of bones' adaptive response to loading in mice is associated with sex‐related deficiencies in osteoblasts but no change in osteocytes. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(8):1859‐1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dunstan CR, Somers NM, Evans RA. Osteocyte death and hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;53 Suppl 1:S113‐S116 discussion S6–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergman RJ, Gazit D, Kahn AJ, Gruber H, McDougall S, Hahn TJ. Age‐related changes in osteogenic stem cells in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(5):568‐577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silbermann M, Weiss A, Reznick AZ, Eilam Y, Szydel N, Gershon D. Age‐related trend for osteopenia in femurs of female C57BL/6 mice. Compr Gerontol A. 1987;1(1):45‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donahue SW, Jacobs CR, Donahue HJ. Flow‐induced calcium oscillations in rat osteoblasts are age, loading frequency, and shear stress dependent. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281(5):C1635‐C1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ardawi MS, Rouzi AA, Al‐Sibiani SA, Al‐Senani NS, Qari MH, Mousa SA. High serum sclerostin predicts the occurrence of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women: the Center of Excellence for Osteoporosis Research Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(12):2592‐2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mach DB, Rogers SD, Sabino MC, et al. Origins of skeletal pain: sensory and sympathetic innervation of the mouse femur. Neuroscience. 2002;113(1):155‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cherruau M, Morvan FO, Schirar A, Saffar JL. Chemical sympathectomy‐induced changes in TH‐, VIP‐, and CGRP‐immunoreactive fibers in the rat mandible periosteum: influence on bone resorption. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194(3):341‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin CD, Jimenez‐Andrade JM, Ghilardi JR, Mantyh PW. Organization of a unique net‐like meshwork of CGRP+ sensory fibers in the mouse periosteum: implications for the generation and maintenance of bone fracture pain. Neurosci Lett. 2007;427(3):148‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu Y, Ma Y, Elefteriou F. Cortical bone is an extraneuronal site of norepinephrine uptake in adult mice. Bone Rep. 2018;9:188‐198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chartier SR, Mitchell SAT, Majuta LA, Mantyh PW. The changing sensory and sympathetic innervation of the young, adult and aging mouse femur. Neuroscience. 2018;387:178‐190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Avakian EV, Horvath SM, Colburn RW. Influence of age and cold stress on plasma catecholamine levels in rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1984;10(2):127‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cizza G, Pacak K, Kvetnansky R, et al. Decreased stress responsivity of central and peripheral catecholaminergic systems in aged 344/N Fischer rats. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(3):1217‐1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taylor J, Weyers P, Harris N, Vogel WH. The plasma catecholamine stress response is characteristic for a given animal over a one‐year period. Physiol Behav. 1989;46(5):853‐856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saar N, Gordon RD. Variability of plasma catecholamine levels: age, duration of posture and time of day. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;8(4):353‐358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ziegler MG, Lake CR, Kopin IJ. Plasma noradrenaline increases with age. Nature. 1976;261(5558):333‐335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pedersen EB, Christensen NJ. Catecholamines in plasma and urine in patients with essential hypertension determined by double‐isotope derivative techniques. Acta Med Scand. 1975;198(5):373‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ito K, Sato A, Sato Y, Suzuki H. Increases in adrenal catecholamine secretion and adrenal sympathetic nerve unitary activities with aging in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1986;69(3):263‐268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strong R, Moore MA, Hale C, Wessels‐Reiker M, Armbrecht HJ, Richardson A. Modulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the rat adrenal gland by age and reserpine. Brain Res. 1990;525(1):126‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erdos B, Broxson CS, Landa T, et al. Effects of life‐long caloric restriction and voluntary exercise on age‐related changes in levels of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes and angiotensin II receptors in the rat adrenal medulla and hypothalamus. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(8):745‐752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleg JL. Ventricular arrhythmias in the elderly: prevalence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Geriatrics. 1988;43(12):23‐29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sowers JR, Mohanty PK. Autonomic nervous system function. J Hypertens Suppl. 1988;6(1):S49‐S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iwase S, Mano T, Watanabe T, Saito M, Kobayashi F. Age‐related changes of sympathetic outflow to muscles in humans. J Gerontol. 1991;46(1):M1‐M5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng AV, Callister R, Johnson DG, Seals DR. Age and gender influence muscle sympathetic nerve activity at rest in healthy humans. Hypertension. 1993;21(4):498‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christensen NJ, Jensen EW. Effect of psychosocial stress and age on plasma norepinephrine levels: a review. Psychosom Med. 1994;56(1):77‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seals DR, Esler MD. Human ageing and the sympathoadrenal system. J Physiol. 2000;528(Pt 3):407‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Farr JN, Charkoudian N, Barnes JN, et al. Relationship of sympathetic activity to bone microstructure, turnover, and plasma osteopontin levels in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(11):4219‐4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Palmer GJ, Ziegler MG, Lake CR. Response of norepinephrine and blood pressure to stress increases with age. J Gerontol. 1978;33(4):482‐487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Young JB, Rowe JW, Pallotta JA, Sparrow D, Landsberg L. Enhanced plasma norepinephrine response to upright posture and oral glucose administration in elderly human subjects. Metabolism. 1980;29(6):532‐539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tahara Y, Takatsu Y, Shiraishi T, et al. Age‐related circadian disorganization caused by sympathetic dysfunction in peripheral clock regulation. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2017;3:16030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bain SD, Huber P, Ausk BJ, et al. Neuromuscular dysfunction, independent of gait dysfunction, modulates trabecular bone homeostasis in mice. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2019;19(1):79‐93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arai M, Sato T, Takeuchi S, Goto S, Togari A. Dose effects of butoxamine, a selective beta2‐adrenoceptor antagonist, on bone metabolism in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;701(1–3):7‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iwata S, Nomoto M, Fukuda T. Effects of beta‐adrenergic blockers on drug‐induced tremors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44(3):611‐613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Srinivasan S, Ausk BJ, Poliachik SL, Warner SE, Richardson TS, Gross TS. Rest‐inserted loading rapidly amplifies the response of bone to small increases in strain and load cycles. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(5):1945‐1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gross TS, Srinivasan S, Liu CC, Clemens TL, Bain SD. Noninvasive loading of the murine tibia: an in vivo model for the study of mechanotransduction. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(3):493‐501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Srinivasan S, Ausk BJ, Bain SD, Gardiner EM, Kwon RY, Gross TS. Rest intervals reduce the number of loading bouts required to enhance bone formation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(5):1095‐1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Worton LE, Ausk BJ, Downey LM, et al. Systems‐based identification of temporal processing pathways during bone cell mechanotransduction. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Glantz SA. Primer of biostatistics. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Srinivasan S, Agans SC, King KA, Moy NY, Poliachik SL, Gross TS. Enabling bone formation in the aged skeleton via rest‐inserted mechanical loading. Bone. 2003;33(6):946‐955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pierroz DD, Bonnet N, Bianchi EN, et al. Deletion of beta‐adrenergic receptor 1, 2, or both leads to different bone phenotypes and response to mechanical stimulation. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(6):1252‐1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Srinivasan S, Threet D, Huber P, et al. Beta 2 adrenergic receptor gene deletion enhances periosteal response to mechanical stimulation in sensecent male mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(Supp. 1):117. [Google Scholar]

- 43. de Souza RL, Pitsillides AA, Lanyon LE, Skerry TM, Chenu C. Sympathetic nervous system does not mediate the load‐induced cortical new bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(12):2159‐2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marenzana M, De Souza RL, Chenu C. Blockade of beta‐adrenergic signaling does not influence the bone mechano‐adaptive response in mice. Bone. 2007;41(2):206‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bonnet N, Benhamou CL, Beaupied H, et al. Doping dose of salbutamol and exercise: deleterious effect on cancellous and cortical bones in adult rats. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(4):1502‐1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chiueh CC, Nespor SM, Rapoport SI. Cardiovascular, sympathetic and adrenal cortical responsiveness of aged fischer‐344 rats to stress. Neurobiol Aging Winter. 1980;1(2):157‐163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McAinsh J, Cruickshank JM. Beta‐blockers and central nervous system side effects. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;46(2):163‐197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ma Y, Krueger JJ, Redmon SN, et al. Extracellular norepinephrine clearance by the norepinephrine transporter is required for skeletal homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(42):30105‐30113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hinojosa‐Laborde C, Chapa I, Lange D, Haywood JR. Gender differences in sympathetic nervous system regulation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26(2):122‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hart EC, Charkoudian N, Wallin BG, Curry TB, Eisenach JH, Joyner MJ. Sex differences in sympathetic neural‐hemodynamic balance: implications for human blood pressure regulation. Hypertension. 2009;53(3):571‐576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu Y, Zhang Q, Zhao B. Wang X. Effect and mechanism of propranolol on promoting osteogenic differentiation and early implant osseointegration. Int J Mol Med. 2021;48(4):191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yamada T, Ezura Y, Hayata T, et al. Beta(2) adrenergic receptor activation suppresses bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)‐induced alkaline phosphatase expression in osteoblast‐like MC3T3E1 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(6):1144‐1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu D, Genetos DC, Shao Y, et al. Activation of extracellular‐signal regulated kinase (ERK1/2) by fluid shear is Ca(2+)‐ and ATP‐dependent in MC3T3‐E1 osteoblasts. Bone. 2008;42(4):644‐652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. You J, Reilly GC, Zhen X, et al. Osteopontin gene regulation by oscillatory fluid flow via intracellular calcium mobilization and activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinase in MC3T3‐E1 osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(16):13365‐13371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guo Y, Lv Q, Zou XQ, Yan ZX, Yan YX. Mechanical strain regulates osteoblast proliferation through Ca(2+)‐CaMK‐CREB signal pathway. Chin Med Sci J. 2016;31(2):100‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Matsumoto T, Kuriwaka‐Kido R, Kondo T, Endo I, Kido S. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by interleukin‐11 via AP‐1 and Smad signaling. Endocr J. 2012;59(2):91‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu CC, Li YS, Haga JH, et al. Roles of MAP kinases in the regulation of bone matrix gene expressions in human osteoblasts by oscillatory fluid flow. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98(3):632‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rangaswami H, Schwappacher R, Tran T, et al. Protein kinase G and focal adhesion kinase converge on Src/Akt/beta‐catenin signaling module in osteoblast mechanotransduction. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(25):21509‐21519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pavalko FM, Chen NX, Turner CH, et al. Fluid shear‐induced mechanical signaling in MC3T3‐E1 osteoblasts requires cytoskeleton‐integrin interactions. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):C1591‐C1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wadhwa S, Godwin SL, Peterson DR, Epstein MA, Raisz LG, Pilbeam CC. Fluid flow induction of cyclo‐oxygenase 2 gene expression in osteoblasts is dependent on an extracellular signal‐regulated kinase signaling pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(2):266‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barthel F, Loeffler JP. Beta 2‐adrenoreceptors stimulate c‐fos transcription through multiple cyclic AMP‐ and Ca(2+)‐responsive elements in cerebellar granular neurons. J Neurochem. 1995;64(1):41‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kellenberger S, Muller K, Richener H, Bilbe G. Formoterol and isoproterenol induce c‐fos gene expression in osteoblast‐like cells by activating beta2‐adrenergic receptors. Bone. 1998;22(5):471‐478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Spooren A, Kooijman R, Lintermans B, et al. Cooperation of NFkappaB and CREB to induce synergistic IL‐6 expression in astrocytes. Cell Signal. 2010;22(5):871‐881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Beck GR Jr, Sullivan EC, Moran E, Zerler B. Relationship between alkaline phosphatase levels, osteopontin expression, and mineralization in differentiating MC3T3‐E1 osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 1998;68(2):269‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang D, Atkins GJ, Turner AG, Anderson PH, Morris HA. Differential effects of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D on mineralisation and differentiation in two different types of osteoblast‐like cultures. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;136:166‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Soejima K, Klein‐Nulend J, Semeins CM, Burger EH. Different responsiveness of cells from adult and neonatal mouse bone to mechanical and biochemical challenge. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186(3):366‐370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Norvell SM, Alvarez M, Bidwell JP, Pavalko FM. Fluid shear stress induces beta‐catenin signaling in osteoblasts. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75(5):396‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Santos A, Bakker AD, Zandieh‐Doulabi B, de Blieck‐Hogervorst JM, Klein‐Nulend J. Early activation of the beta‐catenin pathway in osteocytes is mediated by nitric oxide, phosphatidyl inositol‐3 kinase/Akt, and focal adhesion kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391(1):364‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Xia X, Batra N, Shi Q, Bonewald LF, Sprague E, Jiang JX. Prostaglandin promotion of osteocyte gap junction function through transcriptional regulation of connexin 43 by glycogen synthase kinase 3/beta‐catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(1):206‐219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kamel MA, Picconi JL, Lara‐Castillo N, Johnson ML. Activation of beta‐catenin signaling in MLO‐Y4 osteocytic cells versus 2T3 osteoblastic cells by fluid flow shear stress and PGE2: implications for the study of mechanosensation in bone. Bone. 2010;47(5):872‐881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Case N, Sen B, Thomas JA, et al. Steady and oscillatory fluid flows produce a similar osteogenic phenotype. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88(3):189‐197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Turner CH, Tu Y, Onyia JE. Mechanical loading of bone in vivo causes bone formation through early induction of c‐fos but not c‐Jun of c‐myc. Ann. Biomed Eng. 1996;24(Suppl 1):S‐74. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Forwood MR. Inducible cyclo‐oxygenase (COX‐2) mediates the induction of bone formation by mechanical loading in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(11):1688‐1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lloyd SA, Loiselle AE, Zhang Y, Donahue HJ. Shifting paradigms on the role of connexin43 in the skeletal response to mechanical load. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(2):275‐286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Elefteriou F. Impact of the autonomic nervous system on the skeleton. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(3):1083‐1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request from the authors.