Abstract

Microbial diversity is associated with improved outcomes in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT), but the mechanism underlying this observation is unclear. In a cohort of 174 patients who underwent allo-HCT, we demonstrate that a diverse intestinal microbiome early after allo-HCT is associated with an increased number of innate-like mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, which are in turn associated with improved overall survival and less acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD). Immune profiling of conventional and unconventional immune cell subsets revealed that the prevalence of Vδ2 cells, the major circulating subpopulation of γδ T cells, closely correlated with the frequency of MAIT cells and was associated with less aGVHD. Analysis of these populations using both single cell transcriptomics and flow cytometry suggested a shift toward activated phenotypes and a gain of cytotoxic and effector functions after transplantation. A diverse intestinal microbiome with the capacity to produce activating ligands for MAIT and Vδ2 cells appeared to be necessary for the maintenance of these populations after allo-HCT. These data suggest an immunological link between intestinal microbial diversity, microbe-derived ligands, and maintenance of unconventional T cells.

One sentence summary

MAIT and Vδ2 cells are supported by a diverse intestinal microbiome after allogeneic HCT and correlate with favorable outcome.

Introduction

Unconventional T cells are potent early responder T cells that act as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity (1). These populations are equipped with a T cell receptor (TCR) like conventional T cells, but they do not recognize peptide antigens presented in the context of highly polymorphic MHC molecules and are instead activated by lipid and metabolite antigens presented by conserved antigen-presenting molecules (1). These antigens typically go undetected by the conventional T cell subtypes. MAIT cells recognize metabolites derived from the microbial riboflavin pathway presented as antigens in the context of the ubiquitously-expressed MHC-class I related protein MR1(2). Natural killer T (NKT) cells recognize microbial and self glycolipids presented by CD1d (3), and Vδ2 cells, the major circulating subset of human γδ T cells, respond to intermediates in the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) isoprenoid synthesis pathway (4). Of these, the molecule 4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMBPP) is the most potent activating ligand and binds to the intracellular domain of butyrophilin 3A1 (BTN3A1) and 2A1 (BTN2A1), which then undergo a confirmation change that is recognized by the γδ TCR (5, 6). The anti-microbial role of unconventional T cells in the context of infection is well-recognized, however, the role of the commensal microbiota in regulating unconvential T cell homeostasis is less well understood (7–10).

Studies from our group and others have associated features of the early post-transplant intestinal microbiome with overall survival and complications related to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) (11–13). Allo-HCT is a curative-intent therapy for hematological cancers that involves immunoablative pre-treatment of the recipient with chemotherapy and/or radiation followed by infusion of an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell graft from either a family member or unrelated donor. Despite advances in the field, the broader implementation of allo-HCT is limited by high rates of transplantation-related complications, with 3-year overall mortality approaching 50% (14). Intestinal microbial α-diversity is a commonly used summary metric reflecting both the number of different taxa present and their distribution within a sample (15). A diverse intestinal microbiome, measured by a higher α-diversity, during the peri-engraftment period (days 7–21 after cell infusion) has been associated with favorable transplantation outcomes (11). These included lower risks of infection, relapse of the underlying malignancy and incidence of graft versus host disease (GVHD), an immune-mediated condition in which the donor T cells attack host tissues (11, 12, 16).

Unconventional T cells have restricted TCRs and lack the donor-MHC restriction that is characteristic of the reconstituting conventional donor T cell subsets with undesirable alloreactive potential. They also have been reported to have anti-tumor effects and have the capacity for antigen-independent activation (i.e. via cytokine signaling) (1). With the exception of NKT cells, which have been well-studied in mouse models of allo-HCT (17–19), a key challenge of studying unconventional T cells is that mouse models do not faithfully mimic the biology of these cell types in humans. Recipient MAIT cells have been studied in mouse models of GVHD and have been shown to have a protective effect (20). However, the number of circulating MAIT cells is markedly lower in mice than in humans, and characterization of their function has been generally limited to tissue-resident cells. Differences in the γδ subsets are even more striking between mice and humans. The Vδ2+ cells (which are almost exclusively Vγ9+) are the most prevalent circulating γδ T cell subset in humans but lack a mouse homolog (21), making functional studies of this cell type possible only by using xenograft mouse models and humanized mice (22–24). For these reasons, characterization of primary human samples is crucial to deciphering the contributions of these unconventional T cell populations to immune function (25). In humans, NKT cell numbers have been associated with lower rates of GVHD (26, 27). γδ T cells confer a strong anti-tumor and anti-infectious potential, without aggravating, or even protecting against GVHD (28–32). High MAIT cell counts in infused grafts and post-allo-HCT peripheral blood samples have been associated with lower rates of acute and chronic GVHD, though this has not been a consistent finding in the studies published thus far (33–38). To date, only three human studies in the allo-HCT setting have been able to link MAIT cell reconstitution with the intestinal microbiota, each with a limited number of stool samples (36–38).

Using multi-parameter flow cytometry on peripheral blood samples and stool microbiome analysis, we demonstrate an association between specific early microbiome features and early MAIT cell frequencies after allo-HCT. Higher early MAIT cell frequency is associated with less aGVHD, decreased transplantation-related mortality, and prolonged overall survival. We describe that the Vδ2 subset of γδ T cells correlates with MAIT cells in the post-transplantation setting and both appear dependent on intestinal microbial features and microbiome-derived ligands. These findings suggest that strategies to support microbial diversity in the early post-transplantation period are likely to improve maintenance and recovery of protective unconventional T cell populations, which may be one of the mechanisms by which a diverse microbiome supports favorable long-term patient outcomes after allo-HCT.

Results

Frequency of MAIT cells early post-transplantation is associated with diverse intestinal microbiome and correlates with favorable transplantation outcome

We assembled a cohort of patients (n = 174) undergoing allogeneic HCT at our center and performed multiparameter immunophenotyping and stool microbial profiling. The patient cohort is described in Fig S1 and patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Early MAIT cell reconstitution has previously been associated with favorable outcome after HCT, so we first analyzed the MAIT cell frequency within the CD3+ T cell compartment, as well as their absolute number (cells/μL) at day 30 and day 100 post-transplantation by staining with the MR1 tetramer in combination with CD161 (Fig 1A-B; complete gating strategy shown in Fig S2), capturing predominantly mature MAIT cells (CD45RO+CCR7-). We also identified MAIT cells using an antibody against the invariant Vα7.2 TCR and CD161, which is an alternative staining strategy that is less specific but commonly used, and this analysis produced similar results (Fig S3A-D). A number of patients (45 patients, 23.4 % of the cohort) had samples at both time points and, consistent with others (36), we observed that there was no significant increase in MAIT frequency and absolute numbers between day 30 and day 100 post-transplantation (Fig S4A,B). We analyzed the data as MAIT cell frequency of CD3+ cells rather than absolute cell counts, consistent with previous reports for other unconventional subsets (26). This frequency-based analysis is consistent with data derived from numerical counts, as shown in Fig S5A-D.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics

| All patients | PBSC with d30 sample | |

|---|---|---|

| n=174 | n=118 | |

| Sex = M (%) | 112 (64.4) | 75 (63.6) |

| Age (mean(SD)) | 58.6(12.84) | 60.27(11.22) |

| Disease (%) | ||

| Leukemia | 77 (44.3) | 57 (48.3) |

| MDS/MPN | 42 (24.1) | 29 (24.6) |

| Lymphoma | 45 (25.9) | 30 (25.4) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.7) |

| Non-Malignant Hematological Disorders | 6 (3.4) | |

| Conditioning intensity (%) | ||

| Reduced Intensity | 89 (51.1) | 72 (61.0) |

| Ablative | 56 (32.2) | 28 (23.7) |

| Non-ablative | 29 (16.7) | 18 (15.3) |

| Donor HLA match (%) | ||

| Unrelated Identical | 88 (50.6) | 65 (55.1) |

| Related Identical Sibling | 45 (25.9) | 35 (29.7) |

| Related Haploidentical | 27 (15.5) | 7 (5.9) |

| Unrelated Non-identical | 14 (8.0) | 11 (9.3) |

| Graft source | ||

| PBSC Unmodified (%) | 139 (79.9) | 118 (100.0) |

| BM Unmodified (%) | 35 (20.1) | |

| GVHD = Y (%) | 104 (59.8) | 71 (60.2) |

| Relapse = Y (%) | 47 (27.0) | 33 (28.0) |

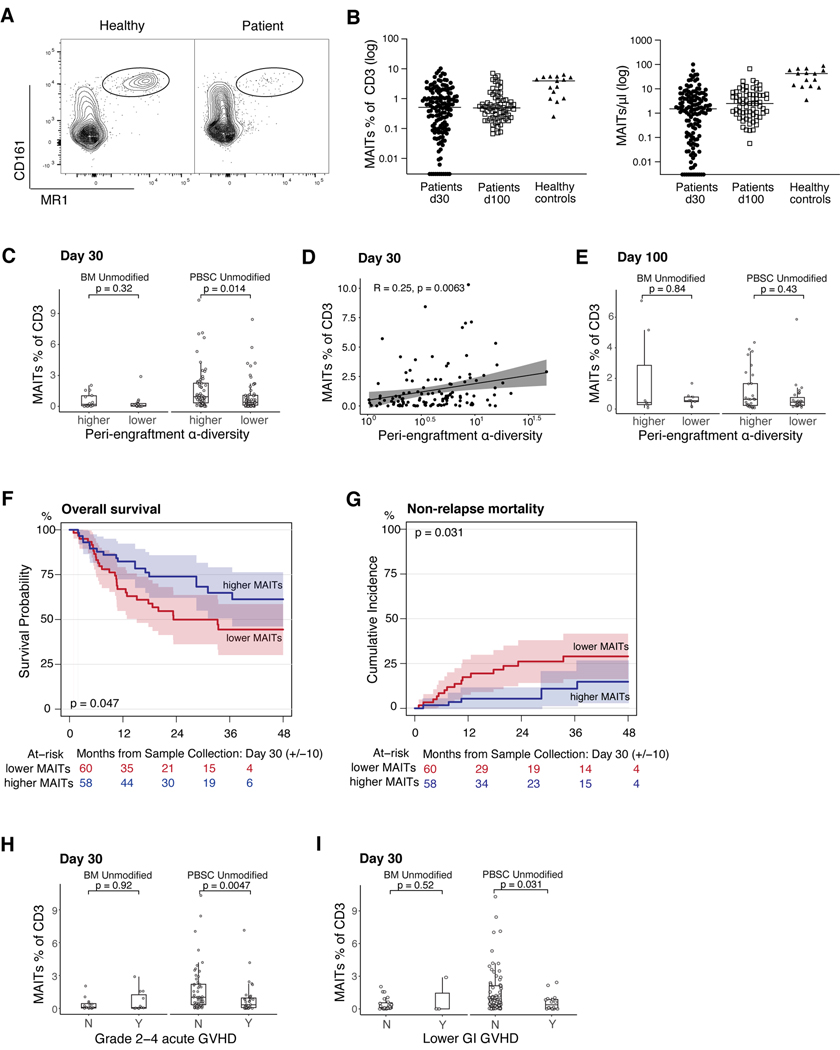

Figure 1: MAIT cells are supported by a diverse intestinal microbiome after HCT and predict favorable patient outcomes.

A) FACS plots of MAIT cells (MR1+/CD161+) in a healthy volunteer and a representative allo-HCT patient. B) MAIT cell frequencies among CD3+ cells and absolute counts on day 30 (+/−10) and day 100 (+/−20) after HCT (frequencies: day 30 n=147, day 100 n=72; healthy n=15; absolute counts: day 30 n=137, day 100 n=70, healthy control n=15). C) Recipients of BM or PBSC grafts were classified into > median (higher) or ≤ median (lower) α-diversity and MAIT frequency at day 30 was compared. (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, BM n=15 ≤ median, n=14 > median, p=0.32; PBSC n=59 ≤ median, n=59 > median, p=0.014). D) Stool α-diversity at day 7 to day 21 as a continuous variable correlated with MAIT frequency at day 30 (Pearson method; n = 118, R=0.25, p=0.0063). Each dot represents an individual patient sample. E) Patients were divided as in C), data shown for day 100 MAIT frequency (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, BM, n=8 ≤ median α-diversity, n=8 > median, p=0.84; PBSC, n=28 ≤ median α-diversity, n=28 > median, p=0.43). F) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of PBSC-graft recipients stratified by MAIT cell frequency (log-rank test, n=118, p=0.047). G) Cumulative incidence of NRM in PBSC-graft recipients with > median or ≤ median MAIT cell frequency (Gray’s test, n=118, p=0.031). H) Recipients of either BM or PBSC grafts were classified by GVHD status (grade 2–4, Y=Yes, grade 2–4 GVHD present, N=No grade 2–4 GVHD). MAIT cell frequency at day 30 shown (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, BM, n=15 grade 0–1 GVHD, n=11, grade 2–4, p=0.92; PBSC, n=53 grade 0–1 GVHD, n=36 with grade 2–4, p=0.0047). I) BM or PBSC recipients were classified by the presence of lower GI GVHD (Y=Yes, lower GI GVHD present or N=No, no lower GI GVHD); MAIT cell frequencies are shown (BM, n=23 without lower GI GVHD, n=3 with lower GI GVHD, p=0.52; PBSC, n=73 without lower GI GVHD, n=16 with any stage lower GI GVHD, p=0.031). H+I) Patients with blood samples collected before or on the day of GVHD onset were included. C+E, H+I) Each dot represents a single patient, boxes represent median with interquartile range.

We next asked whether above-median peri-engraftment fecal bacterial diversity was associated with MAIT cell frequency at days 30 and 100 post transplantation and we compared patients who received unmodified bone marrow (BM) grafts versus recipients of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) grafts. MAIT cells were approximately 2-fold less frequent on day 30 in the samples from recipients of BM grafts compared with PBSC, a difference that was no longer evident on day 100 (Fig S6A-B, p=0.00036 on day 30). Previous reports have suggested that early after HCT, circulating MAIT cells are graft-derived (36). Thus, in recipients of BM grafts (which contain 12 times fewer mature T cells than PBSC grafts (39)), it is to be expected that there are fewer MAIT cells early after transplantation. In the PBSC graft recipients, above-median diversity was associated with higher MAIT cell frequency at day 30, an effect that was not observed in the BM graft recipients (Fig 1C, p=0.014). Of note, more than half (63%) of the BM graft recipients received GVHD-prophylaxis regimens containing post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy), which was previously described to have a negative influence on MAIT cell reconstitution (36). Fecal peri-engaftment α-diversity was measured as the median Simpson reciprocal index among fecal samples collected between day 7 and day 21 for each patient, a time period we have previously shown to be predictive of clinical outcomes in allo-HCT patients (11). In addition to performing analyses in a dichotomous fashion dividing by median diversity of the cohort, we analyzed fecal α-diversity and MAIT cell frequency as continuous variables in the PBSC recipients where we had observed a difference. We confirmed a correlation between early MAIT cells and fecal diversity on day 30 (Fig 1D, R=0.25, p=0.0063). Interestingly, this relationship between day 7–21 fecal diversity and MAIT cells was not observed when MAIT cell frequencies were assessed at day 100, but the patient sample size is smaller at this latter time point (Fig 1E).

MAIT cell frequencies did not appear to be dependent on pre-transplantation conditioning intensity, with equivalent results seen in patients receiving myeloablative, reduced intensity, and nonablative pre-transplantation conditioning regimens (Fig S7). Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate the association of other potential confounding variables with MAIT cell frequency on day 30. Even though the PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis regimens had a negative association with MAIT frequency, peri-engraftment microbial diversity was confirmed as a significant independent factor associated with early MAIT cell frequency (Table 2).

Table 2:

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with MAIT cell frequency (day 30)

| Variable | Estimate (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-engraftment α-diversity* | continuously | 0.178 (0.039–0.317) | 0.013 |

| PTCy | no vs yes | 0.62 (0.309–0.932) | <0.001 |

| Conditioning intensity | non-ablative vs ablative | −0.084 (−0.414–0.247) | 0.62 |

| reduced intensity vs ablative | −0.192 (−0.429–0.045) | 0.114 | |

| Age | continuously | −0.003 (−0.012–0.006) | 0.58 |

| Donor Age | per 10 years | −0.058 (−0.118–0.002) | 0.059 |

| HCT-CI** | 2–3 vs 0–1 | −0.105 (−0.346–0.135) | 0.393 |

| >3 vs 0–1 | −0.252 (−0.501–0) | 0.051 |

Median was calculated if a patient had more than one sample

Hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (77)

Next, we sought to examine the relationship between MAIT cell frequency and patient outcome. We observed that patients who received PBSC grafts (n=118) with higher than median MAIT cell frequency on day 30 (median = 0.64 % of CD3+ cells) had a significantly increased overall survival (Fig 1F, p=0.047) and decreased non-relapse mortality (Fig 1G, p=0.031).

To assess whether MAIT cell frequency was a predictor of GVHD, we excluded any patient who developed GVHD prior to blood sampling (n = 115 remaining in the cohort), and we observed a clear association between MAIT cell frequency and the subsequent development of grade 2–4 acute GVHD and lower gastrointestinal (GI) GVHD in patients receiving PBSC grafts (n=89), but not in patients receiving BM grafts (n=26); (Fig 1 H, I, p=0.0047 and p=0.031, respectively).

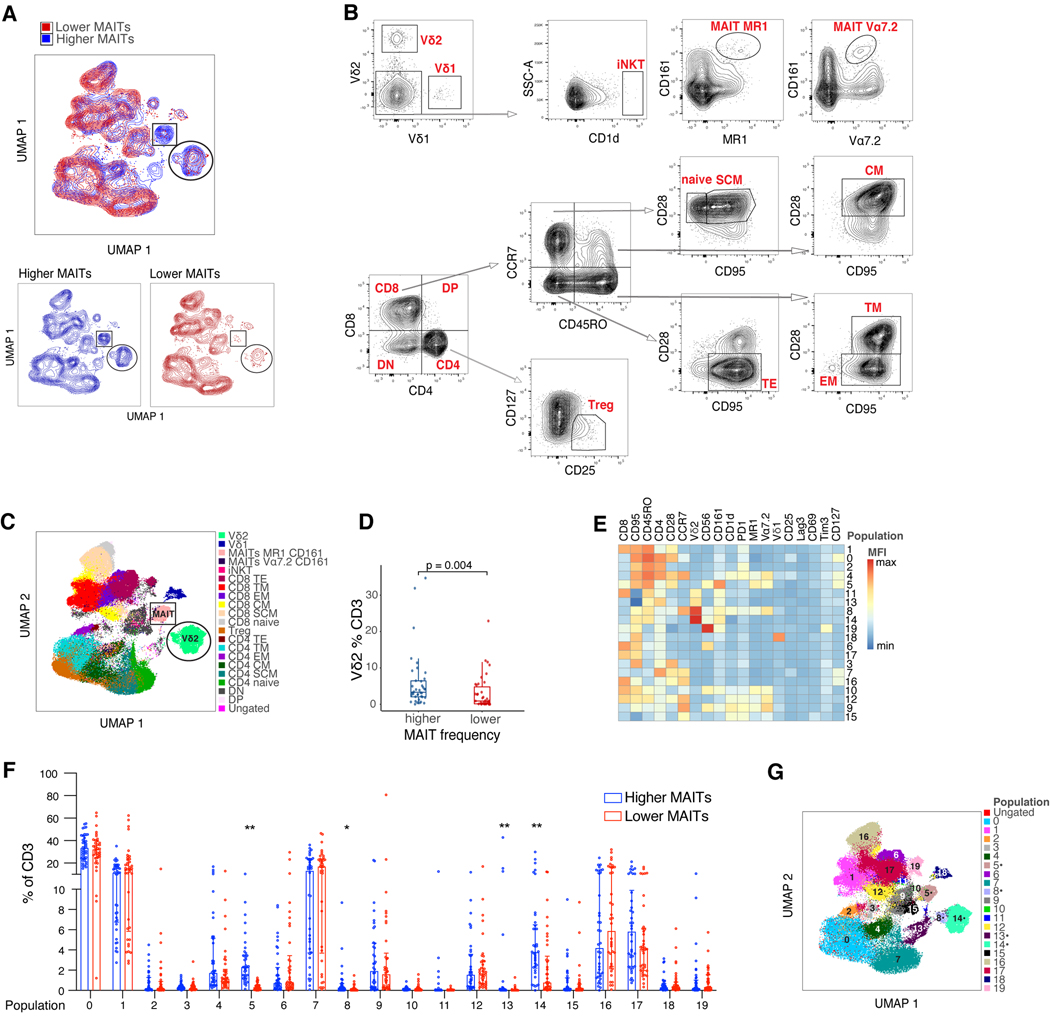

Frequency of Vδ2+ T cell subsets correlates with MAIT cells in high dimensional flow cytometry analysis of early post-transplantation blood samples

Our interest extended beyond the MAIT cells and our complete flow cytometry panel consisting of 22 markers defining conventional and unconventional T cell populations (Table S1) allowed characterization of a number of different cell types in these post-HCT samples. The analysis was performed on samples collected from patients who received PBSC grafts, excluding patients who developed GVHD before their blood sample was collected, those who received PTCy or had extremely low CD3 counts (n=76 remaining in the cohort). We divided patients into higher-than-median MAIT cells or lower than/equal to median MAIT cells (median = 0.84% of CD3+ cells). We first performed a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis to examine the general distribution of subpopulations within the CD3+ T cell compartment and color coded the cells blue or red, according to whether the sample contained above- or below-median MAIT cell frequencies, respectively (n=38 in each group; Fig 2A). To annotate the CD3+ T cell clusters seen in our UMAP plot in these two groups of patients we first used a traditional gating strategy (Fig 2B). Using this approach, we could identify two populations that distinguished the two groups in Fig. 2A. The first was the MAIT cells themselves (Fig 2A, rectangle), as expected. Unexpectedly, another non-MAIT cell cluster was also enriched in samples with highly abundant MAIT cells (Fig 2A, circle). This cluster was identified as the Vδ2 subset of the γδ T cells (Fig 2C, circle). When quantified as a frequency of the CD3+ cells in this patient cohort, we observed a higher Vδ2 cell frequency in the patients with above-median MAIT cell frequency (Fig 2D, p=0.004). To further explore and validate the differences between patients with higher and lower MAIT cell frequency, we defined phenotypic clusters using the self- organizing maps (FlowSOM) (40) algorithm (Fig 2E), in which 19 markers were used to define 20 different clusters within the CD3+ compartment. When examining each of the 20 populations defined by the FlowSOM algorithm, we observed four clusters that were more frequent in the the above-median MAIT cell group. Cluster 5 corresponded to a cell population expressing MAIT cell markers (MR1+, Vα7.2+, CD161+), as expected based on how the patient samples were grouped. Two other clusters (cluster 8 and 14) identified subpopulations highly expressing the Vδ2 cell marker (Fig. 2F-G). The fourth cluster (cluster 13) had a mixed phenotype of CD4 expression and intermediate CD45RO, Vδ2 and CD161 expression. UMAP and FlowSOM analysis of 15 healthy volunteer samples demonstrated different clusters in this sample cohort than those seen in the patient samples (Fig S8A, B, C), which can be explained given general changes in the T cell pool after allo-HCT and the timeline by which allo-HCT patients reach normal T cell counts and phenotypes.

Figure 2: Deep immune profiling reveals higher frequency of the Vδ2 subset of γδ T cells in the samples with higher MAIT frequency after HCT.

A) UMAP clusters in patients with day 30 MAIT frequency higher (blue) or lower than/equal to (red) the population median. Populations different between the two groups are marked by a circle and a rectangle. B) Gating strategy for both the conventional and unconventional T cell populations, which were used to define the UMAP clusters in A. Concatenated CD3+ cells from the same 76 samples from panel A were used to establish the gating scheme. DN = double negative, DP = double positive, SCM = stem cell memory, CM = central memory, TM = transitional memory, EM = effector memory, TE = terminal effector. C) UMAP clustering color coded to identify the gated populations. Clusters that were different between samples with higher and lower MAIT frequency are outlined: MAIT cells (rectangle) and Vδ2 cells (circle). D) Vδ2 cell frequency as a function of higher or lower MAIT frequency (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n= 76, p=0.004). Each dot represents a single patient, boxes represent median with interquartile range. E) Heatmap of 20 populations identified by self-organizing maps (FlowSOM) algorithm, demonstrating mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 19 identifying surface markers. F) Frequency of each FlowSOM population in each patient sample represented by 3000 concatenated CD3+ events/sample. Each dot represents a single patient, lines represent median with interquartile range. Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate differences between the two groups for each population and FDR correction was performed for multiple hypothesis testing, total n=76, *p<0.05, **p < 0.01. G) UMAP projection of 20 populations of CD3+ cells identified by the FlowSOM clustering algorithm. Dots indicate clusters that were different between samples with higher and lower MAIT frequency.

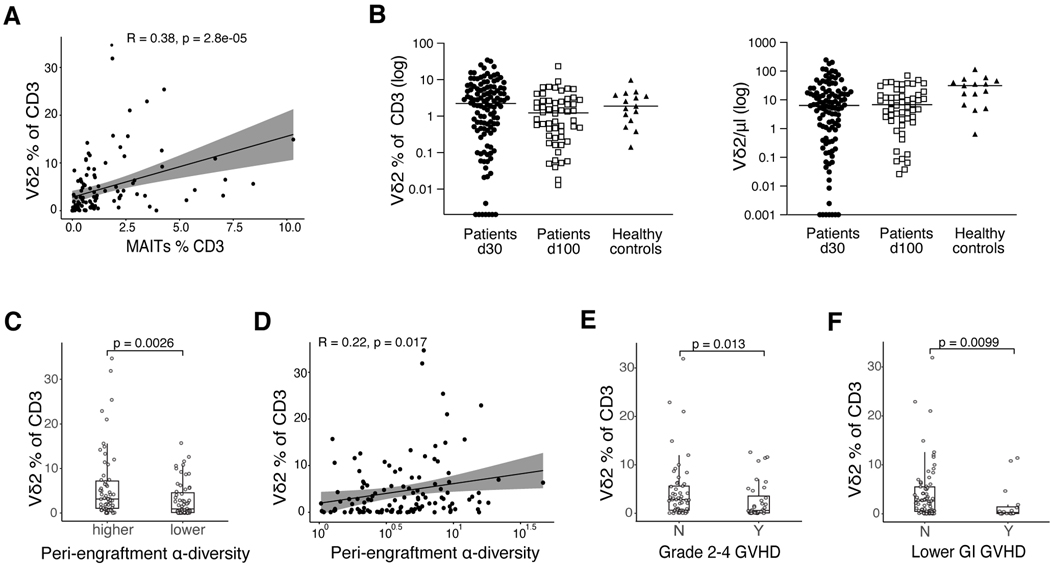

Vδ2 cell frequencies correlate with intestinal microbial diversity and predict acute GVHD

Having discovered that among 20 phenotypically unique CD3+ cell populations, only the Vδ2+ clusters correlated with MAIT cell frequency, we next examined the Vδ2 cell subset in all patients receiving PBSC allografts (n=118). We confirmed the result from the patient cohort used for high dimensional flow cytometry that the frequency of Vδ2 cells is correlated with the frequency of MAIT cells (Fig. 3A, R=0.38, p=2.8e-05). Absolute counts of Vδ2 cells were lower at day 30 post-HCT than in healthy volunteers, however their frequency within the CD3 compartment was comparable (Fig 3B). As we observed for MAIT cells, the day 30 Vδ2 cell frequency is significantly lower in recipients of BM grafts than PBSC grafts. However, unlike in the MAIT population, this difference persists until d100 (Fig. S9A,B). We had demonstrated that patients with higher MAIT proportion have higher peri-engraftment stool α-diversity (Fig 1C-D), and Vδ2 cells are known to depend upon the microbial metabolite HMBPP (4, 5). We observed a significantly higher Vδ2 cell proportion in patients with higher-than-median peri-engraftment stool α-diversity compared with those with lower than/equal to median diversity (Fig 3C, p=0.0026). We confirmed a positive association between early Vδ2 cells and fecal diversity when fecal α-diversity and Vδ2 proportion were analyzed as continuous variables (Fig 3D, R=0.22, p=0.017). When focusing on patients who developed GVHD on the day of or after blood sampling, we observed a negative association between Vδ2 cell frequency and the development of grade 2–4 acute GVHD (Fig 3E, p=0.013), as well as lower GI GVHD (Fig 3F, p=0.0099; absolute counts shown in Fig S10A-C), suggesting that these cells may play a protective role with respect to acute GVHD development.

Figure 3: The frequency of the Vδ2 subset of γδ T cell is associated with higher fecal α-diversity in peri-engraftment stool samples and lower rates of overall and lower intestinal acute GVHD.

A) MAIT and Vδ2 cell frequency analyzed as continuous variables in day 30 blood samples from recipients of PBSC grafts (Pearson correlation, n=118, R=0.38, p=2.8e-05). B) Vδ2 cell frequencies among CD3+ cells and absolute counts on day 30 (+/−10) and day 100 (+/−20) after HCT in PBSC graft recipients (frequencies: day 30 n=118, day 100 n=56; healthy n=15; absolute counts: day 30 n=110, day 100 n=54, healthy control n=15). C) PBSC graft recipients were classified as in Fig 1C into > median (higher) and ≤ median (lower) α-diversity and Vδ2 cell frequency in each subgroup at day 30 was compared (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n = 118, p=0.0026). D) Fecal α-diversity between day 7 and day 21 as a continuous variable correlated with Vδ2 frequency (Pearson correlation, n = 118, R=0.22, p=0.017). E) PBSC graft recipients were classified by GVHD grade (grade 2–4, Y=Yes, grade 2–4 GVHD present, N=No grade 2–4 GVHD) and Vδ2 frequencies compared in each group (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n=53 grade 0–1 GVHD, n=36 grade 2–4, p=0.013). F) Patients were classified by lower GI GVHD status (Y=Yes, lower GI GVHD present or N=No, no lower GI GVHD) and Vδ2 frequencies were compared in each group (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n=73 without lower GI GVHD, n=16 with any stage lower GI GVHD, p=0.0099). E+F) Patients with blood samples collected before or on the day of GVHD onset were included. A and D) Each dot represents a single patient sample. C+ E+ F) Each dot represents a single patient, and boxes represent median with interquartile range.

We performed flow cytometric analysis on additional day 30 samples from allo-HCT patients treated at another center (Duke University Medical Center; n=69 PBMC samples, n=58 with matched stool samples, n=49 received PBSC grafts) and we confirmed an association between the frequency of MAIT and Vδ2 populations. However, in this small cohort we could not establish any additional associations (Fig S11A-E).

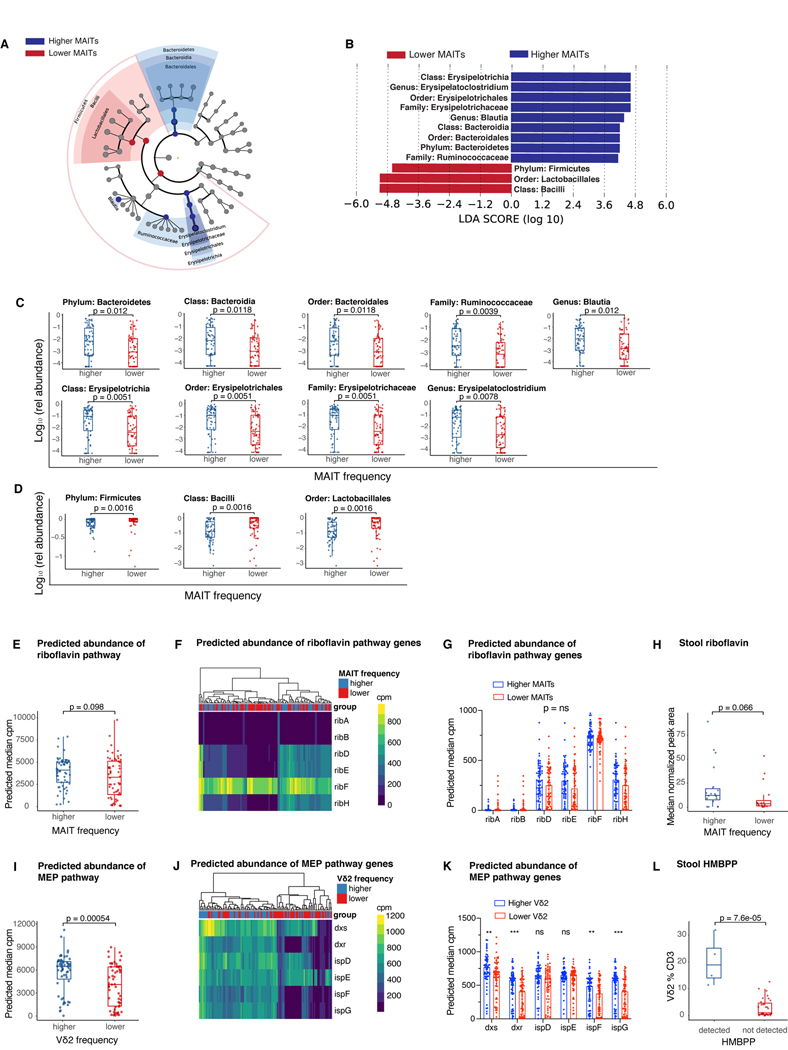

Specific bacterial taxa and their metabolites support MAIT and Vδ2 cell reconstitution

To extend our microbiota-related findings beyond α-diversity and further examine the microbial community profiles associated with MAIT and Vδ2 cell reconstitution we used LEfSe analysis (41) to identify a number of microbial taxa that are associated with higher than median or lower than/equal to median MAIT cell frequency at day 30 after transplantation. A higher abundance of the phylum Bacteroidetes was associated with higher MAIT cell frequency at day 30, whereas the phylum Firmicutes is more abundant in the patients with lower MAIT cell frequency (Fig 4A-B), corresponding with an in vitro study of the ability of human commensal strains to stimulate an engineered MAIT reporter system (42). Moreover, other members of this phylum, Bacilli (class) and Lactobacillales (order), the abundance of which was inversely correlated with MAIT cell frequencies, are predominantly comprised of species such as Enterococcus, which lack the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway and therefore do not synthesize the MAIT-activating metabolites (43). Conversely, higher MAIT cell frequency was associated with a higher relative abundance of the class Bacteroidia and order Bacteroidales, as well as the class Erysipelotrichia, order Erysipelotrichales, family Erysipelotrichaceae and the genus Erysipelatoclostridium. The bacterial family Ruminococcaceae and genus Blautia were also more abundant in patients with higher MAIT frequency, the latter in concordance with previously published findings in the allo-HCT patients (36). The differences observed in the LEfSe analysis were further confirmed in the comparison of the relative abundance of each taxa on a per-patient basis (Fig 4C-D).

Figure 4: Distinct microbial taxa and metabolic pathways support MAIT and Vδ2 cell populations.

A) Differences in peri-engraftment stool microbiota composition between PBSC recipients with MAIT cell frequency > median (higher) or ≤ median (lower) of all patients depicted using LEfSE (n=425 samples collected on day 7 to day 21 post-HCT from 118 patients; median relative abundance per patient at genus level). B) Dominant taxa driving the difference between the two groups (LDA>4, p<0.01). C) Taxa dominant in the higher MAIT cell group from the LEfSE analysis plotted as a relative abundance in patients with higher versus lower MAIT cells as defined above. D) Taxa dominant in the lower MAIT cell group identified by the LEfSE analysis plotted as a relative abundance in patients stratified by MAIT cell frequency. C and D) Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed to compare taxa abundances between groups, FDR correction was performed for multiple hypothesis testing. E) Predicted gene abundance of the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway in PBSC recipients as a function of MAIT cell frequency (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n=118, p=0.098). F) Heatmap representing microbial gene level abundance of key riboflavin biosynthesis enzymes in patients with higher and lower MAIT cell frequency. G) Differences in predicted microbial gene abundance of specific genes encoding key riboflavin biosynthesis enzymes. H) Metabolomic analysis was performed on stool samples collected from patients with previously defined higher or lower MAIT cells. Riboflavin concentrations measured as peak area normalized to internal standard, median value was used when more than one sample per patient was analyzed (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n=35, p=0.066). I) Predicted microbial gene level abundance of the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate/1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (MEP) biosynthesis pathway in PBSC recipients with > median or ≤ median Vδ2 cell frequency using PICRUSt2 analysis (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n=118, p=0.00054). J) Heatmap representing microbial gene level abundance of key MEP biosynthesis enzymes in PBSC recipients with higher and lower Vδ2 cell frequency. K) Differences in microbial gene level abundance of key MEP biosynthesis enzymes. L) HMBPP peak area was measured in the same patient cohort as in H. Patients were divided into those with detectable or not detectable HMBPP and Vδ2 frequencies are shown (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, n=35, p=7.6e-05). E-G and I-K) Total n=425 samples collected d7 to d21 post-transplantation from 118 PBSC allograft recipients were used, plotted is median predicted pathway/enzyme gene abundance in all samples available in this time window per patient. Each dot represents a single patient, and boxes represent median with interquartile range. C-E, G-I, K,L) Each dot represents a single patient, boxes/lines represent median with interquartile range. G,K) Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the groups for each enzyme and FDR correction was performed for multiple hypothesis testing, n=118, **p < 0.01, ***p<0.001, ns = not significant.

As the specific bacterial ligands required for MAIT and Vδ2 cell activation and proliferation are known, we hypothesized that we would be able to identify the pathways associated with production of these ligands by using the PICRUSt2 (44) algorithm. This package uses 16S amplicon abundance data with data from published metagenomes to predict the abundance of functional pathways. We investigated whether higher frequency of MAIT cells in the day 30 blood samples is associated with higher abundance of riboflavin biosynthesis pathway, which leads to the production of activating MAIT cell ligands. Using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) orthology analysis (45) and the MetaCyc pathway database (46), we showed that abundance of both riboflavin biosynthesis pathway (Fig 4E), as well as the key enzymes belonging to this pathway as previously reported (47) (Fig 4F, G) were not differentially present in the patients with higher versus lower MAIT cell frequency. These findings are consistent with an uncoupling of production capacity and true production, as has been demonstrated in vitro (42).

In contrast to these findings, the microbial gene abundance of the MEP biosynthesis pathway, resulting in the production of Vδ2 cell activating ligand HMBPP was significantly more abundant in the samples from patients with Vδ2 cell frequency higher than median (median Vδ2 frequency = 2.235% of CD3+ cells) when compared with those with the frequency equal to median or lower (Fig 4I, p=0.00054). Interestingly, several bacterial species that synthesize isoprenoids using the mevalonate pathway and not the MEP pathway (e.g., Enterococcus and Streptococcus (48)), belong to the order Lactobacillales, which was markedly increased in the patients with lower MAIT and Vδ2 cell frequency. The higher predicted MEP pathway abundance in Vδ2-high patients was further confirmed by higher gene expression of several key enzymes of this pathway in the patient stool samples (Fig 4J, K).

We next performed metabolomic analysis of stool samples from patients with high and low MAIT and Vδ2 cell frequencies (19 patients with highest and 16 with lowest MAIT cell frequencies; n = 70 peri-engraftment stool samples available; 1–3 samples/patient). Attempts to measure previously described MAIT ligands in human stool extracts were unsuccessful, likely due to the low concentration and reactive nature of these metabolites. However, we observed a trend toward a higher riboflavin peak area in patients with above-median MAIT cell frequency (p = 0.066, Fig 4H). Multiple activating ligands for MAIT cells are derived from 5-Amino-6-(D-ribitylamino)uracil (5-A-RU), an intermediate in the riboflavin biosynthetic pathway. Therefore, although riboflavin per se is not an activating ligand for MAIT cells, its concentration may reflect the capacity of intestinal microbial communities to produce the other less stable MAIT cell ligands. In contrast, MEP pathway intermediate HMBPP is one one of the most potent activating ligands for Vδ2 cells with an EC50 < 1nM (49). This metabolite was detected in stool extracts from only four patients in our cohort. Strikingly, these patients had very high Vδ2 cell frequencies in relation to the rest of our patient population (Fig 4L). HMBPP was below the limit of detection in the stool extracts from the remaining patients analyzed. Taken together, these results provide evidence that microbial metabolic products responsible for the activation of both MAIT and Vδ2 cells are present in stool samples from allo-HCT patients and, when detectable, correlate with an increased frequency of these unconventional T cells.

MAIT and Vδ2+ T cell subsets acquire effector/cytotoxic transcriptional signature post-HCT

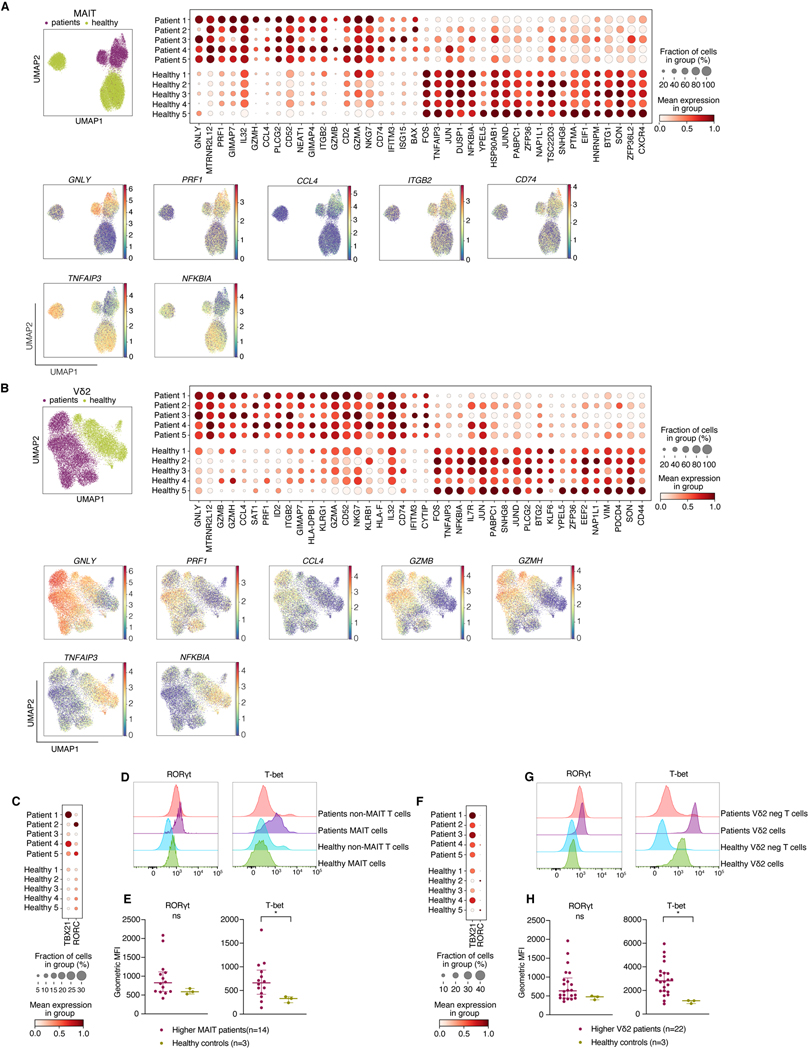

Having observed an association between higher MAIT and Vδ2 T cells and favorable transplant outcome, we examined the transcriptional landscape of these cells using single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) analysis of FACS-purified MAIT and Vδ2 cell populations. We selected five patients with a good transplant outcome that was not complicated by GVHD or early relapse, who had high frequencies of both MAIT and Vδ2 T cells and available PBMC samples. We compared FACS-purified MAIT and Vδ2 populations from allo-HCT patients with cells from healthy volunteers. We identified a number of transcriptional features that are more pronounced in the post-HCT period. MAIT cells upregulated genes linked with effector functions and cytotoxicity, such as GNLY, PRF1 and CCL4, as well as migration/invasiveness, such as the adhesion molecule ITGB2 and chemokine receptor CD74. Genes encoding negative feedback inhibitors of the NFκB pathway (NFKBIA, TNFAIP3) were downregulated, further suggesting pro-inflammatory capacity of post-HCT MAIT cells (Fig. 5A). Post-HCT Vδ2 cells appeared to share many transcriptional changes with MAIT cells e.g. upregulation of GNLY, PRF1 and CCL4, as well granzymes GZMB and GZMH (Fig 5B).

Figure 5: MAIT and Vδ2+ T cell subsets acquire effector cytotoxic transcriptional signature post-transplantation and are mostly Th/Tc1 polarized.

A) Upper left: UMAP clustering of MAIT cells from patients (n=5) and healthy donors (n=5). Upper right: Dotplot demonstrating the most differentially regulated genes between patients and healthy donors. Lower: UMAP plots of the most differentially regulated genes between healthy and patient MAIT cells.

B) Upper left: UMAP clustering of Vδ2 cells from patients and healthy donors. Upper right: Dotplot quantifying the most differentially regulated genes between patients and healthy donors. Lower: UMAP plots of most most differentially regulated genes between healthy and patient Vδ2 cells. C) Gene expression of T-bet and RORγt in patients (n=5) and healthy controls (n=5). D, E) Representative histograms and quantification of RORγt and T-bet expression in MAIT cells from patients with previously defined above median MAIT cell frequency (n=14) and healthy controls (n=3) by flow cytometry. Geometric MFI = geometric mean fluorescence intensity. F) Gene expression of T-bet and RORγt in Vδ2 cells in patients (n=5) and healthy controls (n=5). G, H) Representative histograms of RORγt and T-bet expression in Vδ2 populations from PBMC samples of patients with previously defined above-medianVδ2 cell frequency (n=22) and healthy controls (n=3) by flow cytometry. E+H) Each dot represents a single patient, lines represent median with interquartile range. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the groups, *p<0.05.

It has been suggested that MAIT cells can contribute to tissue repair (7, 50, 51). Thus, we used a reported gene set defining a tissue repair signature and performed a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (52–54). Most of these genes were absent in our dataset or were expressed at a low level, and the pathway was not enriched in patients compared with healthy controls (Fig S12A-D).

Human peripheral blood MAIT cells can express typical Th/Tc1 transcription factor T-bet as well as Th/Tc17-related transcription factor RORγt. When activated, circulating MAIT cells are thought to acquire a Th/Tc1 phenotype, with the majority secreting TNF and IFNγ and only a small subset producing IL-17 (55). In contrast, MAIT cells in G-CSF-mobilised peripheral blood stem cell grafts were shown to bear a Th/Tc17 phenotype, characterized by RORγt upregulation (56). We observed an increase in T-bet expression at both the RNA and protein level in patient samples when compared with the healthy volunteers (Fig 5C-E). Post-HCT Vδ2 cells also expressed more T-bet than this population at steady state (Fig 5F-H). Furthermore, a higher proportion of MAIT expressed Ki-67 after transplantation, suggesting increased proliferation after allo-HCT compared with the steady state (Fig S13).

Discussion

Our study of allo-HCT patients supports the notion that MAIT and Vδ2 cells depend on microbe-derived factors and that together, they support favorable post-transplantation outcomes. Prior work has explored the relationship of MAIT cells with favorable allo-HCT outcome (33, 36–38) and suggested that early Vδ2 abundance is associated with lower rates of GVHD (30), but here we link an in depth analysis of post-transplant immunophenotype with scRNAseq, metabolomics and large-scale microbiome profiling. The association between commensal microbiota and MAIT cells has been explored in the clinical HCT setting and also in different states and diseases, in both mouse and human studies (7, 20, 36–38, 57). The relationship of γδ T cells with the commensal microbiota has not been addressed in a great detail and the relationship between the gut microbiome and the Vδ2 cell subset of γδ T cells has not been described to date. We have demonstrated that both MAIT and Vδ2 cells are present in signficantly higher numbers in patients with higher fecal α-diversity. Both MAIT and Vδ2 cells require specific bacterial metabolites for development and maintenance. In our metabolomic analysis, we observed a trend toward higher riboflavin concentrations in stool samples from patients with higher MAIT cells, although this did not reach statistical significance with the number of samples analyzed. The Vδ2 cell-activating metabolite HMBPP could be measured in a small number of our samples, and consistent with the PICRUSt2 data, these were from patients with the highest frequencies of circulating Vδ2 cells. Although other ligands of Vδ2 cells have been described, such as isoprenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), HMBPP is by far the most potent activator of human Vδ2 T cells (58). Given its activity at nanomolar concentrations (49), it is possible that this metabolite is capable of influencing Vδ2 cell frequencies at concentrations below the detection threshold of our method.

The mechanism by which donor MAIT and Vδ2 cells may protect against aGVHD is not yet clear. MAIT cells are best known for their production of cytotoxic mediators and cytokines upon activation, such as perforin and granzymes, IFNγ, TNF and IL-17, although the latter is not thought to be abundantly produced by circulating MAIT cells at steady state (55). Moreover, MAIT cells in the skin have been associated with tissue repair in a mouse model (7). In the context of GVHD, a pre-clinical study demonstrated that recipient MAIT cells are protective with regard to acute gut GVHD in an IL-17-dependent fashion (20). While less is known regarding the Vδ2 T cells because this specific γδ population cannot be studied in mice, Vδ2 cells can produce IFNγ and a subset of the Vδ2 cells of healthy neonates and adults was also shown to produce IL-17 when stimulated in vitro with IL-6, IL-23, IL-1β and TGF-α (59, 60). Our data suggest that the MAIT and Vδ2 populations undergo comparable transcriptional changes after allo-HCT, consistent with a gain of cytotoxic and effector function. Although we observed expression of some genes associated with tissue repair in MAIT and Vδ2 cells, their expression was low and this pathway was not upregulated in the patients compared with healthy volunteers. The upregulation of the proinflammatory and cytotoxic genes in microbiota-responsive populations could reflect a role for these populations in controlling pathogenenic bateria or cell populations. Recent studies have indeed shown that granulysin facilitates granzyme delivery into bacterial cells and causes their death (61, 62). Furthermore, both MAIT and Vδ2 cells have been demonstrated to release granulysin and perforin upon TCR activation in the context of infection (63, 64). These hypotheses will require further exploration in prospective studies, and moreover, circulating unconventional T cells might differ from their tissue resident counterparts.

We are cognizant that there are several limitations of our study. We assessed the association between the intestinal microbiome and MAIT and Vδ2 cells in samples that were collected and available as part of broad biobanking efforts at our center, rather than conducting a prospective, multicenter study. We believe that multicenter studies, as well as deeper mechanistic analyses will be needed to validate the positive predictive effects of these populations on the outcome of allo-HCT patients. While our metabolomic analysis corroborates the PICRUSt2 predictions, we could not measure metabolites in all stool samples from our patient cohort, and thus the robustness of this analysis remains limited by small patient numbers.

In summary, we propose that microbiome-derived molecules support the maintenance of both MAIT and Vδ2 cell populations after allo-HCT. Strategies to support intestinal microbial diversity may therefore be beneficial for transplantation patients due to a positive effect on unconventional T cell populations.

Study Design

The objective of the study was to examine the association of post-transplantation unconventional T cell subsets, their relationship with conventional T cells and intestinal microbiome composition and characteristics in patients undergoing allo-HCT. Inclusion criteria for this study were: patients undergoing allogeneic HCT with an umodified PBSC or BM graft at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer center (MSKCC) in New York with an evaluable peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) sample collected on day +30 (+/−10 days) and/or day +100 (+/−20) relative to HCT and at least one available stool sample (successfully 16S-amplified and sequenced with >200 reads) that had been collected between day +7 and day +21. One patient who received a combination of BM and PBSC grafts and one patient who did not engraft were excluded from the study. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in full in Fig S1. Five of the patients in the cohort had participated in a randomized clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT, NCT02269150) (65) and received FMT after stool and blood samples were collected for this analyses. Clinical acute GVHD was graded according to the Glucksberg criteria and reviewed in a concensus meeting at our institution (66).

The biospecimen collection protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at MSKCC (Protocol numbers: 06–107 and 16–834) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Control blood samples were collected from healthy volunteers who also provided a written informed consent to the biospecimen collection protocol approved by the institutional review board at MSKCC.

Materials and Methods

Stool collection and analysis, taxa identification using LEfSe and metagenomic prediction

Stool samples were collected in the peri-engraftment time window, defined as day +7 to day +21 after HCT. DNA extraction, polymerase-chain-reaction amplification of genomic 16S ribosomal RNA V4–V5 regions, and sequencing were performed as previously described (11–13).

The α-diversity was calculated using the reciprocal Simpson index on the amplicon sequence variant (ASV) level. The 16S sequencing data was examined with the DADA2 pipeline (67) using default parameters except for the maxEE=2 and truncQ=2 in filterandtrim() function. For every sample, read number was capped at 100,000. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were annotated based on the NCBI 16S ribosomal RNA sequences database using BLAST (68). The α-diversity was calculated using the reciprocal Simpson index on the ASV level.

Linear discriminant analysis of effect size (LEfSe) is a high-dimensional class comparison algorithm that performs non-parametric statistical testing as well as additional tests to assess biological relevance, to describe taxonomic features leading to major differences between two groups (41). Genus-level abundances were analyzed by LEfSE using Galaxy server (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/root). Only the taxa with relative abundance higher than 10−4 in at least 10% of the samples were included. For patients with multiple fecal samples in the sampling window, median genus-level abundances were aggregated for analysis. Differentially abundant taxa between the two patient groups with higher and lower MAIT cell frequency were considered statistically significant using the p value < 0.01 and LDA log score cutoff +/− 4.

Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt2) is a method used to predict functional characteristics of bacterial communities based on 16S sequencing (44). ASV counts for each sample and the sequences for each unique ASV were used to run through the PICRUSt2 pipeline. Gene families were annotated against the KEGG orthology (45). MetaCyc databases was used to identify the specific pathways (46). The predicted abundance for a KEGG ortholog or a pathway per patient were calculated as a median abundance of this gene or pathway across all samples collected from a given patient in the peri-engraftment period, expressed in copies per million (cpm). The pathway and enzyme identifiers from the KEGG orthology and Metacyc database used in the analysis are listed in Table S2.

Metabolomic analyses

Metabolite extraction

Stool samples (180–200 mg) were weighed into beads tubes (Omni) for homogenization. Samples were then extracted using 9 volumes of LC-MS grade 80% methanol containing 100 nM of 13C415N2-riboflavin (IsoSciences) as an internal standard and homogenized using a BeadRuptor (OMNI) for 3 min at 6 m/s. After overnight incubation at −80°C, samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min to clarify and precipitate protein. Extracts were then dried in a vacuum evaporator (Genevac EZ-2 Elite) for 2 h and resuspended in 75 μL of 50% methanol. Finally, samples were vortexed, incubated on ice for 20 min, and clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was divided into two injections vials for acquisition with LC-MS/MS methods (ion pair and reverse phase LC separations).

LC-MS/MS metabolite detection

Ion pair LC-MS/MS analysis was performed with LC separation on a Zorbax RRHD Extend-C18 column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm particle size, Agilent Technologies), and using a gradient of solvent A (10 mM tributylamine and 15 mM acetic acid in 97:3 water:methanol) and solvent B (10 mM tributylamine and 15 mM acetic acid in methanol) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MassHunter Metabolomics dMRM Database and Method, Agilent Technologies). LC separation was coupled to an Agilent 6470 series triple quadrupole system using a dual Agilent Jet Stream source. The capillary voltage was 2000 V, nebulizer gas pressure of 45 psi, drying gas temperature of 250°C, drying gas flow rate of 13 L/min and delta electron multiplier voltage (EMV) of 600 V. The injection volume was 7.5 μL. HMBPP was detected in negative mode with transitions: 261→159 (CE 20); 261→79* (CE 28), *indicates primary transition used for quantitation.

Reverse phase LC-MS/MS analysis for riboflavin detection was performed with LC separation on a CORTECS UPLC C18+ (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.6 μm particle size, Waters), and using a gradient of solvent A (8.7 mM formate/formic acid, pH 2.9 in water) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile). A linear chromatographic gradient was used (0.5% B to 99.5% B in 12 minutes) at 0.4 mL/min flow rate, followed by 2 minutes of flushing at 99.5% B at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/minute. LC separation was coupled to an Agilent 6495C series triple quadrupole system using a dual Agilent Jet Stream source. The capillary voltage was 4000 V in positive and 3000 V in negative, nebulizer gas pressure of 25 psi, drying gas temperature of 230°C, drying gas flow rate of 12 L/min and delta EMV of 600 V. The injection volume was 7.5 μL. Riboflavin was detected in positive mode with transitions: 377→57 (CE 32); 377→172 (CE 26); 377→243* (CE 24), *indicates primary transition used for quantitation.

Data analysis was performed using MassHunter Quantitative Analysis (v. B.09.00).

PBMC isolation and flow cytometry

Patient PBMCs were collected into Becton Dickinson Vacutainer® CPTTM Cell Preparation Tubes with Sodium Citrate. Cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen in a freezing medium containing RPMI, 10% DMSO and 12.5% human serum albumin (HSA). PBMCs from healthy samples were isolated using density centrifugation with Ficoll Paque®. Between 0.3 × 106 and 10 × 106 PBMCs were stained in PBS with LIVE/DEAD Zombie UV Fixable dye (Biolegend) for 20 min at room temperature. Human Fc block (Miltenyi Biotec) was then added for 10 minutes at 4°C, followed by a staining with MR1-5-OP-RU APC and CD1d-PBS-57 BV421 or MR1-Ac-6-FP and CD1d unloaded tetramer (43) (acquired from NIH tetramer core facility) for 40 minutes at room temperature. The tetramer staining was followed by surface antibody staining for 15 minutes at room temperature. In each batch of samples (n per batch ranged from 23 to 30), we included one or more healthy control samples stained with loaded and unloaded tetramer. In most batches, we included a pooled patient sample stained with the unloaded tetramer.

For the intracellular flow cytometry analysis, the tetramer and surface staining was performed as described above. Cells were then fixed for and permeabilized with the Foxp3/transcription factor staining buffer set (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Intracellular antibody staining was performed for 30 minutes at room temperature.

The complete list of antibodies in the flow cytometry panel is available in Table S1. Samples were analyzed using LSR Fortessa X50 Symphony cytometer (BD Bioscience). Standardized SPHERO rainbow beads (BD Biosciences) and SPHERO Supra Rainbow Beads (Spherotech) were used to track and adjust photomultiplier tube voltages over time. UltraComp eBeads (Invitrogen) were used for compensation.

Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo Software version 10.7.2 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, Oregon). Patients who had no measurable lymphocyte or CD3+ population either in the complete blood count or in the flow cytometry analysis were considered to have immune cell populations downstream of CD3 equal to zero. These patients were included in the analysis of cell frequencies and absolute counts but were excluded from the high-dimensional flow cytometry analyses. The absolute counts were calculated as the percentage of live lymphocytes from the flow cytometry analysis multiplied by the white blood cell count (WBC) from the same day for patients where this information was available.

High-dimensional analysis of the flow cytometry data

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) learning technique, as well as FlowSOM algorithm creating self organizing maps (SOMs) (40) were performed using FlowJo Software plugins (FlowJo version 10.7.2, LLC, Ashland, Oregon) and the R programming language. After excluding doublets, dead cells, CD14/CD19 positive cells, 3000 CD3+ events of each patient sample were concatenated (one of the patients had only 2098 events). The UMAP analysis was performed using 15 nearest neighbors with minimum distance of 0.5. The FlowSOM analysis was performed using 20 meta clusters. The following markers were used for UMAP and FlowSOM analysis for closer phenotyping of the CD3+ population: CD4, CD8, CCR7, CD45RO, CD95, CD28, CD127, CD25, CD56, MR1 tetramer, CD1d tetramer, Vα7.2, Vδ1, Vδ2, CD161, CD69, PD1, Tim3, Lag3. The 20 populations defined by FlowSOM were further identified in each of the individual samples represented by 3000 concatenated events for statistical analysis.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing

FACS-purification of MAIT and Vδ2 populations from patients was performed using remaining aliquots (2–5 aliquots/patient) of the same sample that was used for the original flow cytometry analysis. Both patient and healthy control samples were stained as described above and sorted using the FACSAria instrument (BD Bioscience). The single-cell RNA-Seq of FACS-purifed cell suspensions was performed on Chromium instrument (10X genomics) following the user guide manual for 3′ v3.1. Between 6,000 to 30,000 cells were targeted for each sample. Samples were multiplexed together on one lane of 10X Chromium following cell hashing protocol (69). Final libraries were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq S4 platform (R1 – 28 cycles, i7 – 8 cycles, R2 – 90 cycles). The cell-gene count matrix was constructed using the Sequence Quality Control (SEQC) package (70). Viable cells were identified on the basis of library size and complexity, whereas cells with >20% of transcripts derived from mitochondria were excluded from further analysis.

Quality control, de-multiplexing, noise reduction and clustering

The SEQC-generated count matrices for each of the samples were further sanitized and integrated using the shunPykeR pipeline (71). The SEQC-generated count matrices were processed using the scanpy v1.8.2 toolkit (72). Ribosomal genes and genes that were not expressed in any cell were removed from downstream analysis. Each cell was then normalized to a total library size of 10,000 reads and gene counts were log-transformed using the log(X+1) formula, in which log denotes the natural logarithm. Principal component analysis was applied to reduce noise prior to data clustering. The knee point (eigenvalues smaller radius of curvature) was used to select the optimal number of principal components to retain for each dataset. Phenograph (73) was used to identify clusters within the PCA-reduced data. An adjusted Rand score (range: 5–150, step: 5) higher or equal to 0.8 for 4 consecutive steps was used to select a robust nearest neighbor parameter (k) for Phenograph.

Removal of doublet and contaminant cells

Doublets were predicted using the scrublet (74) python package with default parameters. Although cells were sorted for purified MAIT cell populations after gating out myeloid cells, B cells and CD3 negative cells, a small proportions of the cells expressing either the CD68 myeloid marker or not expressing canonical MAIT cell markers (SLC4A10 and DPP4) were detected and marked as contaminating in our scRNA-seq data. Quality of the single cells was computationally assessed based on total counts, number of genes, mitochondrial fraction and ribosomal fraction per cell, with low total counts, low number of genes (≤1000) and high mitochondrial content (≥0.2) as negative indicators of cell quality. Cells characterized by more than one negative indicator were considered as poor quality cells. To remove in an unbiased way contaminants and poor quality cells, we assessed them in a cluster basis rather than individually. PhenoGraph-generated clusters with a poor quality profile and/or a high number of contaminating cells (expressing high levels of CD68 or not expressing SLC4A10 and DPP4) were removed on a per sample basis. Additionally, cells marked as doublets were filtered out. After removal of these cells, PCA and unsupervised clustering analysis was reapplied to the filtered data as described in the Methods section above.

Differential expression analysis

Differential expression analysis between annotated populations of interest was performed using model-based analysis of single-cell transcriptomics (MAST) (75) with default parameters. Differentially expressed genes were considered statistically significant if the FDR-adjusted p-value was less than 0.05.

Pathway enrichment analysis

The GSEAPreranked module from the GSEA v4.1.0 software (52, 53) was used to predict pathway enrichment for (a) MAIT patients vs MAIT healthy and (b) Vδ2 patients vs Vδ2 healthy comparisons. The coefficient value (log2-transformed fold change) generated by the differential expression analysis with MAST was used to pre-rank all differentially expressed genes. Predicted pathways with an FDR<=0.05 were considered as significantly enriched. Human homologs of mouse genes were generated using Ensembl genes 105 (76).

Statistical Analysis

P-values for α-diversity, taxa abundance, relationship between MAIT/Vδ2 cells and GVHD, metabolic pathway abundances, expression of genes encoding enzymes in these pathways and analysis of stool metabolites were calculated using a two sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test using R (Version 4.0.3). A multivariable linear regression assessed the association between α-diversity and MAIT cell frequency, both modeled continuously, adjusted for PTCy, conditioning, and age. Overall survival was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared by MAIT frequency, categorized as above and below the median, using the log-rank test. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was estimated using cumulative incidence functions, where relapse was considered a competing risk. NRM was compared by the binary MAIT frequency using Gray’s test. P values for differences in the flow cytometry populations defined in the FlowSOM analysis and the differences in transcription factor mean fluorescence intensity between patients and healthy controls were calculated using a Mann-Whitney test in GraphPad Prism. The false discovery rate (FDR) approach was used in multiple hypothesis testing to correct for multiple comparisons in the analysis of FlowSOM defined populations, taxa abundance and riboflavin/MEP pathway enzymes using an algorithm in R.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Patient selection

Figure S2: Gating strategy

Figure S3: MAIT cell identification using CD161 and Vα7.2 TCR staining

Figure S4: Changes in MAIT cell frequencies and absolute counts on d30 and d100

Figure S5: Absolute counts of MAIT cells, diversity and aGVHD

Figure S6: MAIT cell frequency by graft source

Figure S7: MAIT cell frequency by conditioning intensity in PBSC recipients on d30 post-transplantation

Figure S8: Deep immune profiling of healthy control samples

Figure S9: Vδ2 cell frequency by graft source

Figure S10: Absolute counts of Vδ2 cells, diversity and aGVHD on d30 post-transplantation

Figure S11: MAIT and Vδ2 cell frequency on d30 post-transplantation in correlation with intestinal diversity and GVHD in second patient cohort

Figure S12: Tissue repair pathway in MAIT and Vδ2 cells of patients versus healthy controls

Figure S13: Ki67 expression by MAIT and Vδ2 cells of patients versus healthy controls

Table S1: List of antibodies used for flow cytometry

Table S2: KEGG orthology and MetaCyc identification of enzymes and pathways

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Daniel Correia for his input regarding γδ T cell staining and antibody selection, the Hematologic Oncology Tissue Bank at MSKCC for blood sample banking and the NIH tetramer core facility for provision of MR1 and CD1d tetramer complexes.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge the MSKCC Cancer Center Core Grant NCI P30 CA008748 and support from the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. This work was supported in part by the Tri-Institutional Metabolomics Training Program (R25 AI140472).

HA was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT). OM was supported by the American Association of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Young Investigator Award, Hyundai Hope on Wheels young investigator award, Cycle for Survival Equinox Innovation award and Collaborative Pediatric Cancer Research Program Award. RZ was supported by the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy Bridge Fellows Award and acknowledges funding from the NCI SPORE (P50-CA192937). SDW was supported by Clinical Scholars T32 (T32CA009512) and an ASCO Young Investigator Award. JUP reports funding from NHLBI NIH Award K08HL143189 and is a member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. DIG was supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1117766) and an NHMRC Investigator Award (2008913). MRMvdB was supported by NCI awards, MSKCC Cancer Center Core Grants P30 CA008748, R01-CA228358, R01- CA228308, P01-CA023766; NHLBI award R01-HL125571, R01-HL123340; NIA National Institute of Aging award Project 2 of P01-AG052359; NIAID award U01 AI124275; Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initiative award 2016-013; The Lymphoma Foundation; The Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program; and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. KAM would like to acknowledge funding from the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, DKMS, The American Australian Association, The Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians and the American Society for Hematology.

Competing interests

JUP reports research funding, intellectual property fees, and travel reimbursement from Seres Therapeutics, and consulting fees from DaVolterra, CSL Behring, and from MaaT Pharma. He serves on an Advisory board of and holds equity in Postbiotics Plus Research. He has filed intellectual property applications related to the microbiome (reference numbers #62/843,849, #62/977,908, and #15/756,845). Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) has financial interests relative to Seres Therapeutics.

MAP reports honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Equilium, Incyte, Karyopharm, Kite/Gilead, Merck, Miltenyi Biotec, MorphoSys, Novartis, Nektar Therapeutics, Omeros, Takeda, and VectivBio AG, Vor Biopharma. He serves on DSMBs for Cidara Therapeutics, Medigene, Sellas Life Sciences, and Servier, and the scientific advisory board of NexImmune. He has ownership interests in NexImmune and Omeros. He has received research support for clinical trials from Incyte, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, and Novartis. He serves in a volunteer capacity as a member of the Board of Directors of the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) and Be The Match (National Marrow Donor Program, NMDP), as well as on the CIBMTR Cellular Immunotherapy Data Resource (CIDR) Executive Committee.

RZ is inventor on patent applications related to work on glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein (GITR), PD-1 and CTLA-4. R.Z. consulted for Leap Therapeutics and is scientific advisory board member of iTEOS Therapeutics. RZ receives grant support from AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb.

DP receives funding from Takeda Pharmaceutical and Incyte Pharmaceutical and is advisory of Ceramedic, Evive Biotechnology, Incyte Pharmaceutical, Kadmon Corporation and CareDx.

SG receives research funding from Miltenyi Biotec, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Celgene Corp., Amgen Inc., Sanofi, Johnson and Johnson, Inc., Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and is on the Advisory Boards for: Kite Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Celgene Corp., Sanofi, Novartis, Johnson and Johnson, Inc., Amgen Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

DIG is an inventor on patent applications related to γδ T cells, CD1, MR1, a Covid-19 diagnostic test and a Covid-19 vaccine. He is also a scientific advisory board member and shareholder for Avalia Immunotherapies, and his team receives research support funding from CSL.

MRMvdB has received research support and stock options from Seres Therapeutics and stock options from Notch Therapeutics and Pluto Therapeutics; he has received royalties from Wolters Kluwer; has consulted, received honorarium from or participated in advisory boards for Seres Therapeutics, WindMIL Therapeutics, Rheos Medicines, Merck & Co, Inc., Magenta Therapeutics, Frazier Healthcare Partners, Nektar Therapeutics, Notch Therapeutics, Forty Seven Inc., Ceramedix, Lygenesis, Pluto Therapeutics, GlaskoSmithKline, Da Volterra, Vor Biopharma, Novartis (Spouse), Synthekine (Spouse), and Beigene (Spouse); he has intellectual property Licensing with Seres Therapeutics and Juno Therapeutics; and holds a fiduciary role on the Foundation Board of DKMS (a nonprofit organization).

KAM serves on an advisory board of and holds equity in Postbiotics Plus Research.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) has financial interests relative to SeresTherapeutics.

HA, OM, AK, AD, SDW, SV, HYP, SJR, RG, SED, JS, PG, AC, ALCG, CN, MBDS, GKA, NL, RC, IM, EF, DP, CC, AB, LH, NC, ADS, EHV, KKH, SMD, JRC and DIG have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Jupyter notebooks that allow replication of the MAIT and Vδ2 single cell dataset analysis are available on Andrlova_et_al_2022 GitHub repository. Raw and processed files have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus. To review GEO accession GSE194328, use the token gzibwkmctlglrqp.

The Bioproject ID numbers to access the raw and processed files of stool 16s sequencing are listed in Data file S2.

Final version of the manuscript published by Science Translational Medicine is available under following link: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.abj2829?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

Data and materials availability

All data associated with this study are in the paper or supplementary materials.

References

- 1.Godfrey DI, Uldrich AP, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J, Moody DB, The burgeoning family of unconventional T cells. Nature Immunology 16, 1114–1123 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treiner E, Duban L, Bahram S, Radosavljevic M, Wanner V, Tilloy F, Affaticati P, Gilfillan S, Lantz O, Selection of evolutionarily conserved mucosal-associated invariant T cells by MR1. Nature 422, 164–169 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Kaer LV, NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat Rev Immunol 4, 231–237 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hintz M, Reichenberg A, Altincicek B, Bahr U, Gschwind RM, Kollas A-K, Beck E, Wiesner J, Eberl M, Jomaa H, Identification of E-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate as a major activator for human γδ T cells in Escherichia coli. FEBS Letters 509, 317–322 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandstrom A, Peigné C-M, Léger A, Crooks James E., Konczak F, Gesnel M-C, Breathnach R, Bonneville M, Scotet E, Adams Erin J., The Intracellular B30.2 Domain of Butyrophilin 3A1 Binds Phosphoantigens to Mediate Activation of Human Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells. Immunity 40, 490–500 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigau M, Ostrouska S, Fulford TS, Johnson DN, Woods K, Ruan Z, McWilliam HEG, Hudson C, Tutuka C, Wheatley AK, Kent SJ, Villadangos JA, Pal B, Kurts C, Simmonds J, Pelzing M, Nash AD, Hammet A, Verhagen AM, Vairo G, Maraskovsky E, Panousis C, Gherardin NA, Cebon J, Godfrey DI, Behren A, Uldrich AP, Butyrophilin 2A1 is essential for phosphoantigen reactivity by γδ T cells. Science 367, eaay5516 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constantinides MG, Link VM, Tamoutounour S, Wong AC, Perez-Chaparro PJ, Han S-J, Chen YE, Li K, Farhat S, Weckel A, Krishnamurthy SR, Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Linehan JL, Bouladoux N, Merrill ED, Roy S, Cua DJ, Adams EJ, Bhandoola A, Scharschmidt TC, Aubé J, Fischbach MA, Belkaid Y, MAIT cells are imprinted by the microbiota in early life and promote tissue repair. Science 366, eaax6624 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma C, Han M, Heinrich B, Fu Q, Zhang Q, Sandhu M, Agdashian D, Terabe M, Berzofsky JA, Fako V, Ritz T, Longerich T, Theriot CM, McCulloch JA, Roy S, Yuan W, Thovarai V, Sen SK, Ruchirawat M, Korangy F, Wang XW, Trinchieri G, Greten TF, Gut microbiome–mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science 360, eaan5931 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benakis C, Brea D, Caballero S, Faraco G, Moore J, Murphy M, Sita G, Racchumi G, Ling L, Pamer EG, Iadecola C, Anrather J, Commensal microbiota affects ischemic stroke outcome by regulating intestinal γδ T cells. Nat Med 22, 516–523 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legoux F, Bellet D, Daviaud C, El Morr Y, Darbois A, Niort K, Procopio E, Salou M, Gilet J, Ryffel B, Balvay A, Foussier A, Sarkis M, El Marjou A, Schmidt F, Rabot S, Lantz O, Microbial metabolites control the thymic development of mucosal-associated invariant T cells. Science 366, 494–499 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peled JU, Gomes ALC, Devlin SM, Littmann ER, Taur Y, Sung AD, Weber D, Hashimoto D, Slingerland AE, Slingerland JB, Maloy M, Clurman AG, Stein-Thoeringer CK, Markey KA, Docampo MD, Burgos da Silva M, Khan N, Gessner A, Messina JA, Romero K, Lew MV, Bush A, Bohannon L, Brereton DG, Fontana E, Amoretti LA, Wright RJ, Armijo GK, Shono Y, Sanchez-Escamilla M, Castillo Flores N, Alarcon Tomas A, Lin RJ, Yáñez San Segundo L, Shah GL, Cho C, Scordo M, Politikos I, Hayasaka K, Hasegawa Y, Gyurkocza B, Ponce DM, Barker JN, Perales M-A, Giralt SA, Jenq RR, Teshima T, Chao NJ, Holler E, Xavier JB, Pamer EG, van den Brink MRM, Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med 382, 822–834 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenq RR, Taur Y, Devlin SM, Ponce DM, Goldberg JD, Ahr KF, Littmann ER, Ling L, Gobourne AC, Miller LC, Docampo MD, Peled JU, Arpaia N, Cross JR, Peets TK, Lumish MA, Shono Y, Dudakov JA, Poeck H, Hanash AM, Barker JN, Perales MA, Giralt SA, Pamer EG, van den Brink MR, Intestinal Blautia Is Associated with Reduced Death from Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 21, 1373–1383 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L, No D, Gobourne A, Viale A, Dahi PB, Ponce DM, Barker JN, Giralt S, van den Brink M, Pamer EG, The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 124, 1174–1182 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Souza A, Fretham C, Lee SJ, Arora M, Brunner J, Chhabra S, Devine S, Eapen M, Hamadani M, Hari P, Pasquini MC, Perez W, Phelan RA, Riches ML, Rizzo JD, Saber W, Shaw BE, Spellman SR, Steinert P, Weisdorf DJ, Horowitz MM, Current Use of and Trends in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in the United States. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 26, e177–e182 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.C. Human Microbiome Project, Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peled JU, Devlin SM, Staffas A, Lumish M, Khanin R, Littmann ER, Ling L, Kosuri S, Maloy M, Slingerland JB, Ahr KF, Porosnicu Rodriguez KA, Shono Y, Slingerland AE, Docampo MD, Sung AD, Weber D, Alousi AM, Gyurkocza B, Ponce DM, Barker JN, Perales M-A, Giralt SA, Taur Y, Pamer EG, Jenq RR, van den Brink MRM, Intestinal Microbiota and Relapse After Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. JCO 35, 1650–1659 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Strober S, Host natural killer T cells induce an interleukin-4–dependent expansion of donor CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells that protects against graft-versus-host disease. Blood 113, 4458–4467 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leveson-Gower DB, Olson JA, Sega EI, Luong RH, Baker J, Zeiser R, Negrin RS, Low doses of natural killer T cells provide protection from acute graft-versus-host disease via an IL-4–dependent mechanism. Blood 117, 3220–3229 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneidawind D, Baker J, Pierini A, Buechele C, Luong RH, Meyer EH, Negrin RS, Third-party CD4+ invariant natural killer T cells protect from murine GVHD lethality. Blood 125, 3491–3500 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varelias A, Bunting MD, Ormerod KL, Koyama M, Olver SD, Straube J, Kuns RD, Robb RJ, Henden AS, Cooper L, Lachner N, Gartlan KH, Lantz O, Kjer-Nielsen L, Mak JYW, Fairlie DP, Clouston AD, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J, Lane SW, Hugenholtz P, Hill GR, Recipient mucosal-associated invariant T cells control GVHD within the colon. Journal of Clinical Investigation 128, 1919–1936 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pang DJ, Neves JF, Sumaria N, Pennington DJ, Understanding the complexity of γδ T-cell subsets in mouse and human. Immunology 136, 283–290 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vavassori S, Kumar A, Wan GS, Ramanjaneyulu GS, Cavallari M, El Daker S, Beddoe T, Theodossis A, Williams NK, Gostick E, Price DA, Soudamini DU, Voon KK, Olivo M, Rossjohn J, Mori L, De Libero G, Butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphorylated antigens and stimulates human γδ T cells. Nature Immunology 14, 908–916 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Kamath A, Das H, Li L, Bukowski JF, Antibacterial effect of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in vivo. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 108, 1349–1357 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benyamine A, Le Roy A, Mamessier E, Gertner-Dardenne J, Castanier C, Orlanducci F, Pouyet L, Goubard A, Collette Y, Vey N, Scotet E, Castellano R, Olive D, BTN3A molecules considerably improve Vγ9Vδ2T cells-based immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. OncoImmunology 5, e1146843 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis MM, Brodin P, Rebooting Human Immunology. Annual Review of Immunology 36, 843–864 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio M-T, Moreira-Teixeira L, Bachy E, Bouillié M, Milpied P, Coman T, Suarez F, Marcais A, Sibon D, Buzyn A, Caillat-Zucman S, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Varet B, Dy M, Hermine O, Leite-de-Moraes M, Early posttransplantation donor-derived invariant natural killer T-cell recovery predicts the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease and overall survival. Blood 120, 2144–2154 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaidos A, Patterson S, Szydlo R, Chaudhry MS, Dazzi F, Kanfer E, McDonald D, Marin D, Milojkovic D, Pavlu J, Davis J, Rahemtulla A, Rezvani K, Goldman J, Roberts I, Apperley J, Karadimitris A, Graft invariant natural killer T-cell dose predicts risk of acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 119, 5030–5036 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb LS, Gee AP, Hazlett LJ, Musk P, Parrish RS, O’Hanlon TP, Geier SS, Folk RS, Harris WG, McPherson K, Lee C, Henslee-Downey PJ, Influence of T cell depletion method on circulating γδ T cell reconstitution and potential role in the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Cytotherapy 1, 7–19 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perko R, Kang G, Sunkara A, Leung W, Thomas PG, Dallas MH, Gamma Delta T Cell Reconstitution Is Associated with Fewer Infections and Improved Event-Free Survival after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Pediatric Leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 21, 130–136 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minculescu L, Marquart HV, Ryder LP, Andersen NS, Schjoedt I, Friis LS, Kornblit BT, Petersen SL, Haastrup E, Fischer-Nielsen A, Reekie J, Sengelov H, Improved Overall Survival, Relapse-Free-Survival, and Less Graft-vs.-Host-Disease in Patients With High Immune Reconstitution of TCR Gamma Delta Cells 2 Months After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Frontiers in Immunology 10, 1997 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamb LS, Henslee-Downey PJ, Parrish RS, Godder K, Thompson J, Lee C, Gee AP, Rapid Communication: Increased Frequency of TCRγδ+ T Cells in Disease-Free Survivors Following T Cell-Depleted, Partially Mismatched, Related Donor Bone Marrow Transplantation for Leukemia. Journal of Hematotherapy 5, 503–509 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godder KT, Henslee-Downey PJ, Mehta J, Park BS, Chiang KY, Abhyankar S, Lamb LS, Long term disease-free survival in acute leukemia patients recovering with increased γδ T cells after partially mismatched related donor bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation 39, 751–757 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawaguchi K, Umeda K, Hiejima E, Iwai A, Mikami M, Nodomi S, Saida S, Kato I, Hiramatsu H, Yasumi T, Nishikomori R, Kondo T, Takaori-Kondo A, Heike T, Adachi S, Influence of post-transplant mucosal-associated invariant T cell recovery on the development of acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Int J Hematol 108, 66–75 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solders M, Erkers T, Gorchs L, Poiret T, Remberger M, Magalhaes I, Kaipe H, Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells Display a Poor Reconstitution and Altered Phenotype after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Frontiers in Immunology 8, 1861 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]