Abstract

The crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis have been extensively studied because of their pesticidal properties and their high natural levels of production. The increasingly rapid characterization of new crystal protein genes, triggered by an effort to discover proteins with new pesticidal properties, has resulted in a variety of sequences and activities that no longer fit the original nomenclature system proposed in 1989. Bacillus thuringiensis pesticidal crystal protein (Cry and Cyt) nomenclature was initially based on insecticidal activity for the primary ranking criterion. Many exceptions to this systematic arrangement have become apparent, however, making the nomenclature system inconsistent. Additionally, the original nomenclature, with four activity-based primary ranks for 13 genes, did not anticipate the current 73 holotype sequences that form many more than the original four subgroups. A new nomenclature, based on hierarchical clustering using amino acid sequence identity, is proposed. Roman numerals have been exchanged for Arabic numerals in the primary rank (e.g., Cry1Aa) to better accommodate the large number of expected new sequences. In this proposal, 133 crystal proteins comprising 24 primary ranks are systematically arranged.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY OF PESTICIDAL CRYSTAL PROTEIN NOMENCLATURE

Since the first cloning of an insecticidal crystal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis (91), many other such genes have been isolated. Initially, each newly characterized gene or protein received an arbitrary designation from its discoverers: icp (64); cry (21, 121); kurhd1 (31); Bta (88); bt1, bt2, etc. (40); type B and type C (43); and 4.5 kb, 5.3 kb, and 6.6 kb (55). The first systematic attempt to organize the genetic nomenclature relied on the insecticidal activities of crystal proteins for the primary ranking of their corresponding genes (44). The cryI genes encoded proteins toxic to lepidopterans; cryII genes encoded proteins toxic to both lepidopterans and dipterans; cryIII genes encoded proteins toxic to coleopterans; and cryIV genes encoded proteins toxic to dipterans alone.

This system provided a useful framework for classifying the ever-expanding set of known genes. Inconsistencies existed in the original scheme, however, due to attempts to accommodate genes that were highly homologous to known genes but did not encode a toxin with a similar insecticidal spectrum. The cryIIB gene, for example, received a place in the lepidopteran-dipteran class with cryIIA, even though toxicity against dipterans could not be demonstrated for the toxin designated CryIIB. Other anomalies arose after the nomenclature was established. The protein named CryIC, for example, was reported to be toxic to both dipterans and lepidopterans (103), while the protein designated CryIB was reported to be toxic to both lepidopterans and coleopterans (8). Because the nomenclature system provided no central committee or database to maintain standardization, new genes encoding a diverse set of proteins without a common insecticidal activity each received the name cryV, based on the next available Roman numeral (32, 46, 67, 100, 102, 108).

PROPOSED NOMENCLATURE

We propose in this review a revised nomenclature for the cry and cyt genes. To organize the wealth of data produced by genomic sequencing efforts, a new nomenclatural paradigm is emerging, exemplified by the internationally recognized cytochrome P-450 superfamily nomenclature system (68a, 122a). Our proposal conforms closely to this model both in conceptual basis and in nomenclature format. The underlying basis of this type of system is to assign names to members of gene superfamilies according to their degree of evolutionary divergence as estimated by phylogenetic tree algorithms. The nomenclature format in such a system is designed to convey rich informational content about these relationships by appending to the mnemonic root a series of numerals and letters assigned in a hierarchical fashion to indicate degrees of phylogenetic divergence. This change from a function-based to a sequence-based nomenclature allows closely related toxins to be ranked together and removes the necessity for researchers to bioassay each new protein against a growing series of organisms before assigning it a name.

In our proposed revision, Roman numerals have been exchanged for Arabic numerals in the primary rank (e.g., Cry1Aa) to better accommodate the large number of expected new proteins. The mnemonic Cyt to designate crystal proteins showing a general cytolytic activity in vitro has been retained because of its historical precedent and entrenchment in the research literature. Our definition of a Cry protein is rather broad: a parasporal inclusion (crystal) protein from B. thuringiensis that exhibits some experimentally verifiable toxic effect to a target organism, or any protein that has obvious sequence similarity to a known Cry protein. Similarly, Cyt denotes a parasporal inclusion (crystal) protein from B. thuringiensis that exhibits hemolytic activity, or any protein that has obvious sequence similarity to a known Cyt protein. By these criteria, the nontoxic 40-kDa crystal protein from B. thuringiensis subsp. thompsoni, for example, has been excluded from our list, but the lepidopteran-active 34-kDa protein (now Cry15A) encoded by an adjacent gene has been included (11).

The freely available software applications CLUSTAL W (110) and PHYLIP (27) define the sequence relationships among the toxins to form the framework of the new nomenclature. In the first step, CLUSTAL W aligns the deduced amino acid sequences of the full-length toxins and produces a distance matrix, quantitating the sequence similarities among the set of toxins. CLUSTAL W default settings are employed, except that the “delay divergent sequences” setting in the multiple-alignment parameter menu is reduced from 40 to 0%. The NEIGHBOR application within the PHYLIP package then constructs a phylogenetic tree from the distance matrix by an unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic averages (UPGMA) algorithm. The TREEVIEW application (73), with the “phylogenetic tree” and “ladderize left” options selected, produces a graphic presentation of the resulting tree.

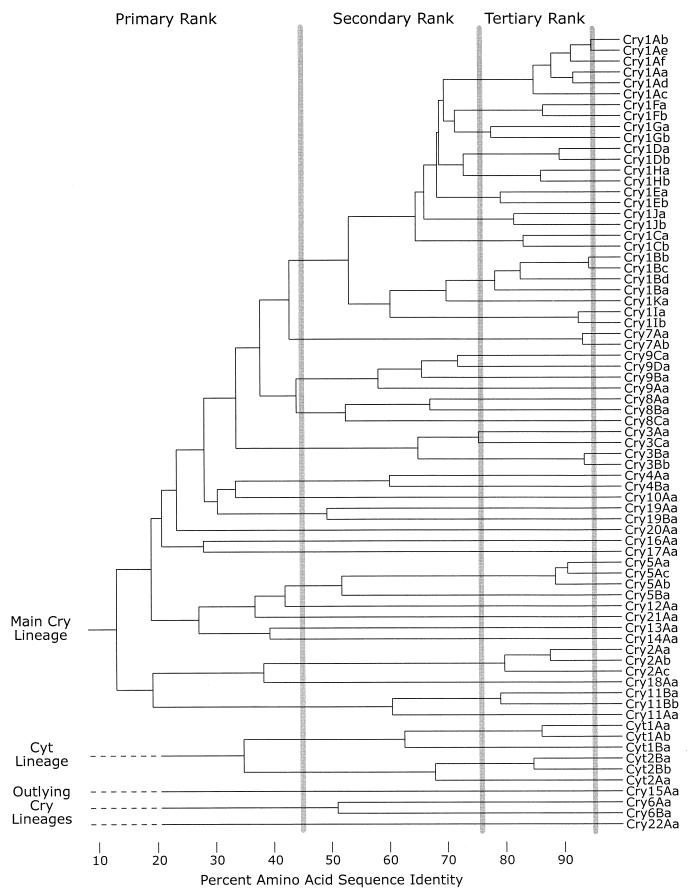

We have applied this procedure to the set of holotype sequences given in Table 1 to produce the phylogenetic tree presented in Fig. 1. Vertical lines drawn through the tree show the boundaries used to define the various nomenclatural ranks. The name given to any particular toxin depends on the location of the node where the toxin enters the tree relative to these boundaries. A new toxin that joins the tree to the left of the leftmost boundary will be assigned a new primary rank (an Arabic number). A toxin that enters the tree between the left and central boundaries will be assigned a new secondary rank (an uppercase letter). It will have the same primary rank as the other toxins within that cluster. A toxin that enters the tree between the central and right boundaries will be assigned a new tertiary rank (a lowercase letter). Finally, a toxin that joins the tree to the right of the rightmost boundary will be assigned a new quaternary rank (another Arabic number). Toxins with identical sequences but isolated independently will receive separate quaternary ranks.

TABLE 1.

Known cry and cyt gene sequences with revised nomenclature assignments

| Revised gene name | Original gene or protein name | Accession no. | Coding regiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cry1Aa1 | cryIA(a) | M11250 | 527–4054 | 92 |

| cry1Aa2 | cryIA(a) | M10917 | 153–>2955 | 98 |

| cry1Aa3 | cryIA(a) | D00348 | 73–3600 | 99 |

| cry1Aa4 | cryIA(a) | X13535 | 1–3528 | 62 |

| cry1Aa5 | cryIA(a) | D17518 | 81–3608 | 113 |

| cry1Aa6 | cryIA(a) | U43605 | 1–>1860 | 63 |

| cry1Ab1 | cryIA(b) | M13898 | 142–3606 | 119 |

| cry1Ab2 | cryIA(b) | M12661 | 155–3622 | 111 |

| cry1Ab3 | cryIA(b) | M15271 | 156–3620 | 31 |

| cry1Ab4 | cryIA(b) | D00117 | 163–3627 | 50 |

| cry1Ab5 | cryIA(b) | X04698 | 141–3605 | 40 |

| cry1Ab6 | cryIA(b) | M37263 | 73–3537 | 37 |

| cry1Ab7 | cryIA(b) | X13233 | 1–3465 | 36 |

| cry1Ab8 | cryIA(b) | M16463 | 157–3621 | 69 |

| cry1Ab9 | cryIA(b) | X54939 | 73–3537 | 13 |

| cry1Ab10 | cryIA(b) | A29125 | —b | 28 |

| cry1Ac1 | cryIA(c) | M11068 | 388–3921 | 3 |

| cry1Ac2 | cryIA(c) | M35524 | 239–3769 | 117 |

| cry1Ac3 | cryIA(c) | X54159 | 339–>2192 | 18 |

| cry1Ac4 | cryIA(c) | M73249 | 1–3534 | 84 |

| cry1Ac5 | cryIA(c) | M73248 | 1–3531 | 83 |

| cry1Ac6 | cryIA(c) | U43606 | 1–>1821 | 63 |

| cry1Ac7 | cryIA(c) | U87793 | 976–4509 | 38 |

| cry1Ac8 | cryIA(c) | U87397 | 153–3686 | 71 |

| cry1Ac9 | cryIA(c) | U89872 | 388–3921 | 33 |

| cry1Ac10 | AJ002514 | 388–3921 | 107 | |

| cry1Ad1 | cryIA(c) | M73250 | 1–3537 | 79 |

| cry1Ae1 | cryIA(e) | M65252 | 81–3623 | 60 |

| cry1Af1 | icp | U82003 | 172–>2905 | 49 |

| cry1Ba1 | cryIB | X06711 | 1–3684 | 10 |

| cry1Ba2 | X95704 | 186–3869 | 105 | |

| cry1Bb1 | ET5 | L32020 | 67–3753 | 25 |

| cry1Bc1 | cryIB(c) | Z46442 | 141–3839 | 6 |

| cry1Bd1 | cryE1 | U70726 | 12 | |

| cry1Ca1 | cryIC | X07518 | 47–3613 | 45 |

| cry1Ca2 | cryIC | X13620 | 241–>2711 | 88 |

| cry1Ca3 | cryIC | M73251 | 1–3570 | 79 |

| cry1Ca4 | cryIC | A27642 | 234–3800 | 114 |

| cry1Ca5 | cryIC | X96682 | 1–>2268 | 106 |

| cry1Ca6 | cryIC | X96683 | 1–>2268 | 106 |

| cry1Ca7 | cryIC | X96684 | 1–>2268 | 106 |

| cry1Cb1 | cryIC(b) | M97880 | 296–3823 | 48 |

| cry1Da1 | cryID | X54160 | 264–3758 | 42 |

| cry1Db1 | prtB | Z22511 | 241–3720 | 56 |

| cry1Ea1 | cryIE | X53985 | 130–3642 | 115 |

| cry1Ea2 | cryIE | X56144 | 1–3513 | 7 |

| cry1Ea3 | cryIE | M73252 | 1–3513 | 82 |

| cry1Ea4 | U94323 | 388–3900 | 47 | |

| cry1Eb1 | cryIE(b) | M73253 | 1–3522 | 81 |

| cry1Fa1 | cryIF | M63897 | 478–3999 | 14 |

| cry1Fa2 | cryIF | M73254 | 1–3525 | 80 |

| cry1Fb1 | prtD | Z22512 | 483–4004 | 56 |

| cry1Ga1 | prtA | Z22510 | 67–3564 | 56 |

| cry1Ga2 | cryIM | Y09326 | 692–4210 | 96 |

| cry1Gb1 | cryH2 | U70725 | 12 | |

| cry1Ha1 | prtC | Z22513 | 530–4045 | 56 |

| cry1Hb1 | U35780 | 728–4195 | 53 | |

| cry1Ia1 | cryV | X62821 | 355–2511 | 108 |

| cry1Ia2 | cryV | M98544 | 1–2157 | 34 |

| cry1Ia3 | cryV | L36338 | 279–2435 | 100 |

| cry1Ia4 | cryV | L49391 | 61–2217 | 54 |

| cry1Ia5 | cryV159 | Y08920 | 524–2680 | 94 |

| cry1Ib1 | cryV465 | U07642 | 237–2393 | 100 |

| cry1Ja1 | ET4 | L32019 | 99–3519 | 25 |

| cry1Jb1 | ET1 | U31527 | 177–3686 | 116 |

| cry1Ka1 | U28801 | 451–4098 | 52 | |

| cry2Aa1 | cryIIA | M31738 | 156–2054 | 20 |

| cry2Aa2 | cryIIA | M23723 | 1840–3738 | 123 |

| cry2Aa3 | D86064 | 2007–3911 | 8911 | |

| cry2Ab1 | cryIIB | M23724 | 1–1899 | 123 |

| Revised gene name | Original gene or protein name | Accession no. | 2125–3990> | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cry2Ab2 | cryIIB | X55416 | 874–2775 | 17 |

| cry2Ac1 | cryIIC | X57252 | 2125–3990 | 124 |

| cry3Aa1 | cryIIIA | M22472 | 25–1956 | 39 |

| cry3Aa2 | cryIIIA | J02978 | 241–2172 | 93 |

| cry3Aa3 | cryIIIA | Y00420 | 566–2497 | 41 |

| cry3Aa4 | cryIIIA | M30503 | 201–2132 | 65 |

| cry3Aa5 | cryIIIA | M37207 | 569–2500 | 22 |

| cry3Aa6 | cryIIIA | U10985 | 569–2500 | 1 |

| cry3Ba1 | cryIIIB2 | X17123 | 25–>1977 | 101 |

| cry3Ba2 | cryIIIB | A07234 | 342–2297 | 85 |

| cry3Bb1 | cryIIIBb | M89794 | 202–2157 | 24 |

| cry3Bb2 | cryIIIC(b) | U31633 | 144–2099 | 23 |

| cry3Ca1 | cryIIID | X59797 | 232–2178 | 59 |

| cry4Aa1 | cryIVA | Y00423 | 1–3540 | 121 |

| cry4Aa2 | cryIVA | D00248 | 393–3935 | 95 |

| cry4Ba1 | cryIVB | X07423 | 157–3564 | 16 |

| cry4Ba2 | cryIVB | X07082 | 151–3558 | 112 |

| cry4Ba3 | cryIVB | M20242 | 526–3930 | 125 |

| cry4Ba4 | cryIVB | D00247 | 461–3865 | 95 |

| cry5Aa1 | cryVA(a) | L07025 | 1–>4155 | 102 |

| cry5Ab1 | cryVA(b) | L07026 | 1–>3867 | 67 |

| cry5Ac1 | I34543 | 1–>3660 | 76 | |

| cry5Ba1 | PS86Q3 | U19725 | 1–>3735 | 76 |

| cry6Aa1 | cryVIA | L07022 | 1–>1425 | 68 |

| cry6Ba1 | cryVIB | L07024 | 1–>1185 | 67 |

| cry7Aa1 | cryIIIC | M64478 | 184–3597 | 58 |

| cry7Ab1 | cryIIIC(b) | U04367 | 1–>3414 | 75 |

| cry7Ab2 | cryIIIC(c) | U04368 | 1–>3414 | 75 |

| cry8Aa1 | cryIIIE | U04364 | 1–>3471 | 29 |

| cry8Ba1 | cryIIIG | U04365 | 1–>3507 | 66 |

| cry8Ca1 | cryIIIF | U04366 | 1–3447 | 70 |

| cry9Aa1 | cryIG | X58120 | 5807–9274 | 104 |

| cry9Aa2 | cryIG | X58534 | 385–>3837 | 32 |

| cry9Ba1 | cryX | X75019 | 26–3488 | 97 |

| cry9Ca1 | cryIH | Z37527 | 2096–5569 | 57 |

| cry9Da1 | N141 | D85560 | 47–3553 | 4 |

| cry9Da2 | AF042733 | <1–>1937 | 122 | |

| cry10Aa1 | cryIVC | M12662 | 941–2965 | 111 |

| cry11Aa1 | cryIVD | M31737 | 41–1969 | 21 |

| cry11Aa2 | cryIVD | M22860 | <1–235 | 2 |

| cry11Ba1 | Jeg80 | X86902 | 64–2238 | 19 |

| cry11Bb1 | 94 kDa | AF017416 | 72 | |

| cry12Aa1 | cryVB | L07027 | 1–>3771 | 67 |

| cry13Aa1 | cryVC | L07023 | 1–2409 | 90 |

| cry14Aa1 | cryVD | U13955 | 1–3558 | 77 |

| cry15Aa1 | 34kDa | M76442 | 1036–2055 | 11 |

| cry16Aa1 | cbm71 | X94146 | 158–1996 | 5 |

| cry17Aa1 | cbm72 | X99478 | 12–1865 | 5 |

| cry18Aa1 | cryBP1 | X99049 | 743–2860 | 126 |

| cry19Aa1 | Jeg65 | Y07603 | 719–2662 | 86 |

| cry19Ba1 | D88381 | 87 | ||

| cry20Aa1 | 86kDa | U82518 | 60–2318 | 61 |

| cry21Aa1 | I32932 | 1–3501 | 74 | |

| cry22Aa1 | I34547 | 1–2169 | 76 | |

| cyt1Aa1 | cytA | X03182 | 140–886 | 118 |

| cyt1Aa2 | cytA | X04338 | 509–1255 | 120 |

| cyt1Aa3 | cytA | Y00135 | 36–782 | 26 |

| cyt1Aa4 | cytA | M35968 | 67–813 | 30 |

| cyt1Ab1 | cytM | X98793 | 28–777 | 109 |

| cyt1Ba1 | U37196 | 1–795 | 78 | |

| cyt2Aa1 | cytB | Z14147 | 270–1046 | 51 |

| cyt2Ba1 | “cytB” | U52043 | 287–655 | 35 |

| cyt2Bb1 | U82519 | 416–1204 | 15 |

The symbols < and > indicate that the coding region extends up- or downstream, respectively, from the known sequence data.

Only the polypeptide sequence has been reported.

FIG. 1.

Phylogram demonstrating amino acid sequence identity among Cry and Cyt proteins. This phylogenetic tree is modified from a TREEVIEW visualization of NEIGHBOR treatment of a CLUSTAL W multiple alignment and distance matrix of the full-length toxin sequences, as described in the text. The gray vertical bars demarcate the four levels of nomenclature ranks. Based on the low percentage of identical residues and the absence of any conserved sequence blocks in multiple-sequence alignments, the lower four lineages are not treated as part of the main toxin family, and their nodes have been replaced with dashed horizontal lines in this figure.

By this method each toxin will be assigned a unique name incorporating all four ranks. A completely novel toxin would currently be assigned the name Cry23Aa1. For the sake of convenience, however, we propose that the inclusion of the tertiary rank a and quaternary rank 1 be optional, their use dictated only by a need for clarity. This new toxin could therefore simply be referred to as Cry23A.

In choosing locations for rank boundaries, we attempted to construct a nomenclature reflecting significant evolutionary relationships while at the same time minimizing changes from the gene names assigned under the old system. In the resulting system, proteins with a common primary rank are similar enough that the percent identity can be defined with some confidence. Proteins with the same primary rank often affect the same order of insect; those with different secondary and tertiary ranks may have altered potency and targeting within an order. At the tertiary rank, differences can be due to the accumulation of dispersed point mutations, but often they appear to have resulted from ancestral recombination events between genes differing at a lower rank level (9). The quaternary rank was established to group “alleles” of genes coding for known toxins that differ only slightly, either because of a few mutational changes or an imprecision in sequencing. To avoid confusion, however, the reader should bear in mind the differences between the quaternary rank number and the classical concept of the allele. Any cry gene specified with a quaternary rank is a natural isolate. No assumption about functionality is implied by the presence of this rank number in the gene name. In contrast, an allele number would be assumed, unless parenthetical or subscripted information indicated otherwise, to denote a nonfunctional mutant form of a wild-type gene found at a discrete genetic locus. Because of the somewhat modular nature of the Cry proteins and the effect that various segmental relationships could have on the clustering algorithm, it is likely that these boundaries will move slightly or even bend as the addition of new sequences changes the topology of the phylogenetic tree. Currently the boundaries represent approximately 95, 78, and 45% sequence identity.

A B. thuringiensis Pesticidal Crystal Protein Nomenclature Committee, consisting of the authors of this paper, will remain as a standing committee of the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (BGSC) to assist workers in the field of B. thuringiensis genetics in assigning names to new Cry and Cyt toxins. The corresponding gene or protein sequences must first be deposited into a publicly accessible database (GenBank, EMBL, or PIR) and released by the repository for electronic publication in the database so that the scientific community may conduct an independent analysis. Researchers should submit new sequences directly to the BGSC director (D. R. Zeigler), either by electronic mail (zeigler.1@osu.edu) or on computer diskette. The director will analyze the amino acid sequence as described above and suggest the appropriate name, subject to the approval of the committee. The committee will periodically review the literature of the Cry and Cyt toxins and publish a comprehensive list. This list, alongside other relevant information, will also be available via the Internet at the following URL: http://www.biols.susx.ac.uk/Home/Neil_Crickmore/Bt/.

The current list of cry and cyt genes (including quaternary ranks) is given in Table 1. New gene names are listed with their previous names, their GenBank accession numbers, and published references. The quaternary ranks were assigned in the order that the gene sequences were discovered in the literature or submitted to the committee. Genes assigned the quaternary rank 1 represent holotype sequences.

The boundaries shown in Fig. 1 allow most cry genes to retain the names they received under the system of Höfte and Whiteley (44), after a substitution of Arabic for Roman numerals. There are a few notable exceptions: cryIG becomes cry9A, cryIIIC becomes cry7Aa, cryIIID becomes cry3C, cryIVC becomes cry10A, cryIVD becomes cry11A, cytA becomes cyt1A, and cytB becomes cyt2A (Table 1). Under the revised system, the known Cry and Cyt proteins fall into 24 sets at the primary rank—Cyt1, Cyt2, and Cry1 through Cry22.

ROBUSTNESS OF THE NOMENCLATURE

The robustness of the current naming process was assessed by a number of additional analyses. The choice of clustering algorithm (unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic averages) was driven largely by the consistent location of a root and constant branch lengths, resulting in a common vertical alignment of sequence names and essentially allowing a “ruler across the tree” approach to naming. It has the drawback of imposing a common evolutionary clock on the clustering process, an assumption that cannot be assured. The distance metric related to percent identity (essentially 1 minus the fraction of identical residues of the total compared without gaps) is the one most commonly found as the output of sequence comparison programs, including CLUSTAL W. For phylogenetic analysis, a more usual distance metric relates to the number of substitutions per site to convert one sequence to the other (e.g., Dayhoff’s point accepted mutation [PAM]) and accounts for the possibility of multiple substitutions per site as the sequences are more divergent. The latter method has the drawback of being more computationally intensive, and, for very divergent sequences, requiring too large a value, resulting in numeric computation failures. They also differ in the way sequences of unequal length are handled, with the percent identity method typically ignoring excess sequence and the other methods assigning a penalty. This is particularly important for crystal proteins, since a number of them lack the C-terminal protoxin segments yet are quite related to some longer toxins in the N-terminal toxin segment; we feel that the stronger association of such relationships found by the percent identity method is preferred.

To assess the effect of using the neighbor-joining method to generate an unrooted tree, CLUSTAL W routines were used to generate such a tree with 1,000 bootstraps of the sequence alignment we used for Fig. 1. When an appropriate outgroup was chosen, the resulting tree (not shown) resembled our Fig. 1. The bootstrap values indicated that the tree thus generated had significant branch points deeper in the tree than the chosen primary rank in the nomenclature. This sort of analysis was rejected as unsuitable for the purposes of Cry nomenclature due to the generally ragged branch lengths it produced and the requirement for the careful choice of an outgroup.

An alternative method of clustering protein sequences, capable of handling sequences that are quite diverse, is parsimony analysis. A consensus tree generated from 100 bootstraps of such an analysis displaces the two incomplete Cry1 sequences (Cry1Bd and Cry1Af) and the two Cry1 sequences lacking the C-terminal protoxin segments (Cry1Ia and Cry1Ib) into a region of the tree populated with such shortened sequences (not shown). With the further exceptions of Cry12A being interjected into the Cry5 cluster and a number of sequences besides Cry6B clustering higher in the tree than Cry6A, the proposed nomenclature successfully reflects the grouping of sequences provided by this method of analysis as well.

As noted above, the usual distance metrics for phylogenetic analysis account for multiple substitutions per site; most commonly, the Dayhoff PAM metric is used. When this distance metric was applied to the alignment used to make Fig. 1, a large number of the sequence pairs were found to have infinite distance. Therefore, the main Cry lineage and the Cyt lineage were separately aligned, the distances were calculated, and the distance matrices were clustered by using the FITCH program (of the PHYLIP software package). This method of analysis revealed several strongly associated groups of sequences (>90% of trees) in the main Cry lineage that extend deeper into the tree than the primary rank assigned in the proposed nomenclature: Cry1; Cry3; Cry4; Cry7; the Cry5, Cry12-Cry13-Cry14-Cry21 group; the Cry8-Cry9 group; the Cry10-Cry19 group; the Cry16-Cry17 group; and the Cry2-Cry11-Cry18 group. Many of these groups, however, were separated by branch points that were either nonmajority or were found <60% of the time; thus, the arrangement of these groups would be likely to change with additional sequence additions. At the secondary rank, the only anomaly with respect to the proposed nomenclature was the interjection of the Cry1Ia and Cry1Ib sequences into the Cry1B group. This effect may be due to an artificially reduced distance between the Cry1I sequences and the incomplete Cry1Bd sequence caused by the particular distance metric used. The Cyt lineage sequences were separated into the expected two primary rank groups that separate into the expected secondary rank groupings. This more standard phylogenetic approach also suffers from an accentuated visual disorientation of uneven branch lengths and shortening of the more closely related branches, especially at the tertiary rank (lowercase letter), where a great deal of comparative work has been done among the Cry1 toxins.

In summary, the proposed nomenclature uses readily available software that can be easily interpreted by investigators in the field and meets their needs as well as, or better than, alternative methods of analysis and presentation. When the holotype toxins were analyzed by alternative phylogenetic methods, the hierarchy implied by the nomenclature was essentially consistent with the resulting phylogenetic clustering, and the few exceptions were largely explainable by known properties of the sequences in question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The BGSC is supported by National Science Foundation grant DBI-9319712 and by industrial sponsorships.

Footnotes

Editor’s note: Articles published in this journal represent the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams L F, Mathewes S, O’Hara P, Petersen A, Gürtler H. Elucidation of the mechanism of CryIIIA overproduction in a mutagenized strain of Bacillus thuringiensis var. tenebrionis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams L F, Visick J E, Whiteley H R. A 20-kilodalton protein is required for efficient production of the Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis 27-kilodalton crystal protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:521–530. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.521-530.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adang M J, Staver M J, Rocheleau T A, Leighton J, Barker R F, Thompson D V. Characterized full-length and truncated plasmid clones of the crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD-73 and their toxicity to Manduca sexta. Gene. 1985;36:289–300. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asano S I, Nukumizu Y, Bando H, Iizuka T, Yamamoto T. Cloning of novel enterotoxin genes from Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1054–1057. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1054-1057.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barloy F, Delécluse A, Nicolas L, Lecadet M-M. Cloning and expression of the first anaerobic toxin gene from Clostridium bifermentans subsp. malaysia, encoding a new mosquitocidal protein with homologies to Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3099–3105. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3099-3105.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop, A. H. 1994. Unpublished observation.

- 7.Bossé M, Masson L, Brousseau R. Nucleotide sequence of a novel crystal protein gene isolated from Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kenyae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7443. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley D, Harkey M A, Kim M-K, Biever D, Bauer L S. The insecticidal CryIB protein of Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. thuringiensis has dual specificity to coleopteran and lepidopteran larvae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1995;65:162–173. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bravo A. Phylogenetic relationships of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin family proteins and their functional domains. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2793–2801. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2793-2801.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brizzard B L, Whiteley H R. Nucleotide sequence of an additional crystal protein gene cloned from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. thuringiensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:2723–2724. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.6.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown K L, Whiteley H R. Molecular characterization of two novel crystal protein genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. thompsoni. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:549–557. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.549-557.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chak, K. F. 1996. Unpublished observation.

- 13.Chak K F, Chen J C. Complete nucleotide sequence and identification of a putative promoter region for the expression in Escherichia coli of the cryIA(b) gene from Bacillus thuringiensis var. aizawai HD133. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China. 1993;17:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers J A, Jelen A, Gilbert M P, Jany C S, Johnson T B, Gawron-Burke C. Isolation and characterization of a novel insecticidal crystal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. aizawai. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3966–3976. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.3966-3976.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheong H, Gill S S. Cloning and characterization of a cytolytic and mosquitocidal δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. jegathesan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3254–3260. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3254-3260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chungjatupornchai W, Höfte H, Seurinck J, Angsuthanasombat C, Vaeck M. Common features of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins specific for Diptera and Lepidoptera. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dankocsik C, Donovan W P, Jany C S. Activation of a cryptic crystal protein gene of Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki by gene fusion and determination of the crystal protein insecticidal specificity. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2087–2094. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dardenne F, Seurinck J, Lambert B, Peferoen M. Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of a cryIA(c) gene variant from Bacillus thuringiensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5546. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.18.5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delécluse A, Rosso M-L, Ragni A. Cloning and expression of a novel toxin gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. jegathesan encoding a highly mosquitocidal protein. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4230–4235. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4230-4235.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donovan W P, Dankocsik C C, Gilbert M P, Gawron-Burke W C, Groat R R, Carlton B C. Amino acid sequence and entomocidal activity of the P2 crystal protein. An insect toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:561–567. . (Author’s correction, 263:4740.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan W P, Dankocsik C, Gilbert M P. Molecular characterization of a gene encoding a 72-kilodalton mosquito-toxic crystal protein from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4732–4738. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4732-4738.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donovan W P, González J M, Jr, Gilbert M P, Dankocsik C. Isolation and characterization of EG2158, a new strain of Bacillus thuringiensis toxic to coleopteran larvae, and nucleotide sequence of the toxin gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;214:365–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00330468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donovan, W. P., M. J. Rupar, and A. C. Slaney. January 1995. U.S. patent 5,378,625.

- 24.Donovan W P, Rupar M J, Slaney A C, Malvar T, Gawron-Burke M C, Johnson T B. Characterization of two genes encoding Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins toxic to Coleoptera species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3921–3927. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3921-3927.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donovan, W. P., Y. Tan, C. S. Jany, and J. M. González, Jr. June 1994. U.S. patent 5,322,687.

- 26.Earp D J, Ellar D J. Bacillus thuringiensis var. morrisoni strain PG14: nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding a 27 kDa crystal protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3619. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.8.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischhoff D A, Bowdisch K S, Perlak F J, Marrone P G, McCormick S H, Niedermeyer J G, Dean D A, Kusano-Kretzmer K, Mayer E J, Rochester D E, Rogers S G, Fraley R T. Insect tolerant transgenic tomato plants. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:807–813. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foncerrada, L., A. J. Sick, and J. M. Payne. August 1992. European Patent Office no. EP 0498537.

- 30.Galjart N J, Sivasubramanian N, Federici B A. Plasmid location, cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding a 23-kilodalton cytolytic protein from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. morrisoni (PG-14) Curr Microbiol. 1987;16:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geiser M, Schweitzer S, Grimm C. The hypervariable region in the genes coding for entomopathogenic crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis: nucleotide sequence of the kurhd1 gene of subsp. kurstaki HD1. Gene. 1986;48:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gleave A P, Hedges R J, Broadwell A H. Identification of an insecticidal crystal protein from Bacillus thuringiensis DSIR517 with significant sequence differences from previously described toxins. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:55–62. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gleave A P, Hedges R J, Broadwell A H, Wigley P J. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of an insecticidal crystal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis DSIR732 active against three species of leafroller Lepidoptera Tortricidae. N Z J Crop Hortic Sci. 1992;20:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gleave A P, Williams R, Hedges R J. Screening by polymerase chain reaction of Bacillus thuringiensis serotypes for the presence of cryV-like insecticidal protein genes and characterization of a cryV gene cloned from B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1683–1687. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1683-1687.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerchicoff A, Ugalde R U, Rubinstein C P. Identification and characterization of a previously undescribed cyt gene in Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2716–2721. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2716-2721.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haider M Z, Ellar D J. Nucleotide sequence of a Bacillus thuringiensis aizawai ICI entomocidal crystal protein gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10927. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hefford M A, Brousseau R, Préfontaine G, Hanna Z, Condie J A, Lau P C K. Sequence of a lepidopteran toxin gene of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki NRD-12. J Biotechnol. 1987;6:307–322. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herrera G, Snyman S J, Thomson J A. Construction of a bioinsecticidal strain of Pseudomonas flourescens active against the sugarcane borer, Eldana saccharina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:682–690. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.682-690.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrnstadt C, Gilroy T E, Sobieski D A, Bennett B D, Gaertner F H. Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of a coleopteran-active delta-endotoxin gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. san diego. Gene. 1987;57:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Höfte H, de Greve H, Seurinck J, Jansens S, Mahillon J, Ampe C, Vandekerckhove J, van Montagu M, Zabeau M, Vaeck M. Structural and functional analysis of a cloned delta endotoxin of Bacillus thuringiensis berliner 1715. Eur J Biochem. 1986;161:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Höfte H, Seurinck J, Van Houtven A, Vaeck M. Nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding an insecticidal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis var. tenebrionis toxic against Coleoptera. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7183. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.7183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Höfte H, Soetaert P, Jansens S, Peferoen M. Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of a new Lepidoptera-specific crystal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5545. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.18.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Höfte H, Van Rie J, Jansens S, Van Houtven A, Vanderbruggen H, Vaeck M. Monoclonal antibody analysis and insecticidal spectrum of three types of lepidopteran-specific insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2010–2017. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2010-2017.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Höfte H, Whiteley H R. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:242–255. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.242-255.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honée G, van der Salm T, Visser B. Nucleotide sequence of crystal protein gene isolated from B. thuringiensis subspecies entomocidus 60.5 coding for a toxin highly active against Spodoptera species. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6240. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hori H, Suzuki K, Ogiwara K, Minani M, Himejima M, Sakanaka K, Kaji Y, Asano S, Sato R, Ohba M, Iwahana H. Presented at the XXVth Annual Meeting of the Society for Invertebrate Pathology, Heidelberg, Germany. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibarra, J. 1997. Unpublished observation.

- 48.Kalman S, Kiehne K L, Libs J L, Yamamoto T. Cloning of a novel cryIC-type gene from a strain of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. galleriae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1131-1137.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang, S. K., H. S. Kim, and Y. M. Yu. 1997. Unpublished observation.

- 50.Kondo S, Tamura N, Kunitate A, Hattori M, Akashi A, Ohmori I. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of two insecticidal δ-endotoxin genes from Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki HD-1 DNA. Agric Biol Chem. 1987;51:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koni P A, Ellar D J. Cloning and characterization of a novel Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic delta-endotoxin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:319–327. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koo, B. T. 1995. Unpublished observation.

- 53.Koo B T, Park S H, Choi S K, Shin B S, Kim J I, Yu J H. Cloning of a novel crystal protein gene cry1K from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp morrisoni. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kostichka K, Warren G W, Mullins M, Mullins A D, Craig J A, Koziel M G, Estruch J J. Cloning of a cryV-type insecticidal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis: the cryV-encoded protein is expressed early in stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2141–2144. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2141-2144.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kronstad J W, Whiteley H R. Three classes of homologous Bacillus thuringiensis crystal-protein genes. Gene. 1986;43:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lambert, B. 1993. Unpublished observation.

- 57.Lambert B, Buysse L, Decock C, Jansens S, Piens C, Saey B, Seurinck J, Van Audenhove K, Van Rie J, Van Vliet A, Peferoen M. A Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal protein with a high activity against members of the family Noctuidae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:80–86. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.80-86.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambert B, Höfte H, Annys K, Jansens S, Soetaert P, Peferoen M. Novel Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal protein with a silent activity against coleopteran larvae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2536–2542. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2536-2542.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lambert B, Theunis W, Agouda R, Van Audenhove K, C. D, Jansens S, Seurinck J, Peferoen M. Nucleotide sequence of gene cryIIID encoding a novel coleopteran-active crystal protein from strain BTI109P of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki. Gene. 1992;110:131–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90457-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee C-S, Aronson A I. Cloning and analysis of δ-endotoxin genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. alesti. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6635–6638. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6635-6638.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee H-K, Gill S S. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel mosquitocidal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. fukuokaensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4664–4670. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4664-4670.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Masson L, Marcotte P, Préfontaine G, Brousseau R. Nucleotide sequence of a gene cloned from Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies entomocidus coding for an insecticidal protein toxic for Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:446. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.1.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Masson L, Mazza A, Gringorten L, Baines D, Aneliunas V, Brousseau R. Specificity domain localization of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxins is highly dependent on the bioassay system. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:851–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLinden J H, Sabourin J R, Clark B D, Gensler D R, Workman W E, Dean D H. Cloning and expression of an insecticidal k-73 type crystal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki into Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:623–628. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.3.623-628.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McPherson S A, Perlak F J, Fuchs R L, Marrone P G, Lavrik P B, Fischhoff D A. Characterization of the coleopteran-specific protein gene of Bacillus thuringiensis var. tenebrionis. Bio/Technology. 1988;6:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michaels, T. E., K. E. Narva, and L. Foncerrada. August 1993. World Intellectual Property Organization patent WO 93/15206.

- 67.Narva, K. E., J. M. Payne, G. E. Schwab, L. A. Hickle, T. Galasan, and A. J. Sick. December 1991. European Patent Office no. EP 0462721.

- 68.Narva, K. E., G. E. Schwab, T. Galasan, and J. M. Payne. August 1993. U.S. patent 5,236,843.

- 68a.Nelson D R, Koymans L, Kamataki T, Stegeman J J, Feyereisen R, Waxman D J, Waterman M R, Gotoh O, Coon M J, Estabrook R W, Gunsalus I C, Nebert D W. P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers and nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:1–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oeda K, Oshie K, Shimizu M, Nakamura K, Yamamoto H, Nakayama I, Ohkawa H. Nucleotide sequence of the insecticidal protein gene of Bacillus thuringiensis strain aizawai IPL7 and its high-level expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;53:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ogiwara K, Hori H, Minami M, Takeuchi K, Sato R, Ohba M, Iwahana H. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding novel delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis serovar japonensis strain Buibui specific to scarabaeid beetles. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:227–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00293638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Omolo E O, D. J M, O. O E, Thomson J A. Cloning and expression of a Bacillus thuringiensis (L1-2) gene encoding a crystal protein active against Glossina morsitans morsitans and Chilo partellus. Curr Microbiol. 1997;34:118–121. doi: 10.1007/s002849900154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Orduz, S. Unpublished observation.

- 73.Page R D M. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. CABIOS. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Payne, J., K. E. Narva, and J. Fu. December 1996. U.S. patent 5,589,382.

- 75.Payne, J. M., and J. M. Fu. February 1994. U.S. patent 5,286,486.

- 76.Payne, J. M., M. K. Kennedy, J. B. Randall, H. Meier, H. J. Uick, L. Foncerrada, H. E. Schnepf, G. E. Schwab, and J. Fu. January 1997. U.S. patent 5,596,071.

- 77.Payne, J. M., and K. E. Narva. July 1994. World Intellectual Property Organization patent WO 94/16079.

- 78.Payne, J. M., K. E. Narva, K. A. Uyeda, C. J. Stalder, and T. E. Michaels. July 1995. U.S. patent 5,436,002.

- 79.Payne, J. M., and A. J. Sick. September 1993. U.S. patent 5,246,852.

- 80.Payne, J. M., and A. J. Sick. February 1993. U.S. patent 5,188,960.

- 81.Payne, J. M., and A. J. Sick. April 1993. U.S. patent 5,206,166.

- 82.Payne, J. M., and A. J. Sick. August 1991. U.S. patent 5,039,523.

- 83.Payne, J. M., A. J. Sick, and M. Thompson. August 1992. U.S. patent 5,135,867.

- 84.Payne, J. M., G. G. Soares, H. W. Talbot, and T. C. Olson. October 1991. U.S. patent 4,990,332.

- 85.Peferoen, M., B. Lambert, and H. Joos. August 1990. European patent Office no. EP 0382990-A1.

- 86.Rosso M L, Delecluse A. Contribution of the 65-kilodalton protein encoded by the cloned gene cry19A to the mosquitocidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. jegathesan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4449–4455. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4449-4455.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saitoh, H. 1996. Unpublished observation.

- 88.Sanchis V, Lereclus D, Menou G, Chaufaux J, Guo S, Lecadet M-M. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of the N-terminal coding region of the Spodoptera-active δ-endotoxin gene of Bacillus thuringiensis aizawai 7.29. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:229–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sasaki J, Asano S, Hashimoto N, Lay B-W, Hastowo S, Bando H, Iizuka T. Characterization of a cry2A gene cloned from an isolate of Bacillus thuringiensis serovar sotto. Curr Microbiol. 1997;35:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s002849900201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schnepf, H. E., G. E. Schwab, J. M. Payne, K. E. Narva, and L. Foncerrada. November 1992. World Intellectual Property Organization patent WO 92/19739.

- 91.Schnepf H E, Whiteley H R. Cloning and expression of the Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein gene in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2893–2897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schnepf H E, Wong H C, Whiteley H R. The amino acid sequence of a crystal protein from Bacillus thuringiensis deduced from the DNA base sequence. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6264–6272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sekar V, Thompson D V, Maroney M J, Bookland R G, Adang M J. Molecular cloning and characterization of the insecticidal crystal protein gene of Bacillus thuringiensis var. tenebrionis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7036–7040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Selvapandiyan, A. 1996. Unpublished observation.

- 95.Sen K, Honda G, Koyama N, Nishida M, Neki A, Sakai H, Himeno M, Komano T. Cloning and nucleotide sequences of the two 130 kDa insecticidal protein genes of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52:873–878. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shevelev A B, Kogan Y N, Busheva A M, Voronina E J, Tebrikov D V, Novikova S I, Chestukhina G G, Kubshinov V, Pehu E, Stepanov V M. A novel delta-endotoxin gene cryIM from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. wuhanensis. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:148–152. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shevelev A B, Svarinsky M A, Karasin A I, Kogan Y N, Chestukhina G G, Stepanov V M. Primary structure of cryX, the novel delta-endotoxin-related gene from Bacillus thuringiensis spp. galleriae. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81613-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shibano Y, Yamagata A, Nakamura N, Iizuka T, Sugisaki H, Takanami M. Nucleotide sequence coding for the insecticidal fragment of the Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein. Gene. 1985;34:243–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shimizu M, Oshie K, Nakamura K, Takada Y, Oeda K, Ohkawa H. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the 135-kDa insecticidal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. aizawai IPL7. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52:1565–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shin B-S, Park S-H, Choi S-K, Koo B-T, Lee S-T, Kim J-I. Distribution of cryV-type insecticidal protein genes in Bacillus thuringiensis and cloning of cryV-type genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki and Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. entomocidus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2402–2407. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2402-2407.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sick A, Gaertner F, Wong A. Nucleotide sequence of a coleopteran-active toxin gene from a new isolate of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. tolworthi. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1305. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.5.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sick, A. J., G. E. Schwab, and J. M. Payne. January 1994. U.S. patent 05281530.

- 103.Smith G P, Ellar D J. Mutagenesis of two surface-exposed loops of the Bacillus thuringiensis CryIC δ-endotoxin affects insecticidal specificity. Biochem J. 1994;302:611–616. doi: 10.1042/bj3020611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Smulevitch S V, Osterman A L, Shevelev A B, Kaluger S V, Karasin A I, Kadyrov R M, Zagnitko O P, Chestukhina G G, Stepanov V M. Nucleotide sequence of a novel delta-endotoxin gene cryIG of Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. galleriae. FEBS Lett. 1991;293:25–28. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81144-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Soetaert, P. 1996. Unpublished observation.

- 106.Strizhov, N. 1996. Unpublished observation.

- 107.Sun, M. 1997. Unpublished observation.

- 108.Tailor R, Tippett J, Gibb G, Pells S, Pike D, Jordon L, Ely S. Identification and characterization of a novel Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin entomocidal to coleopteran and lepidopteran larvae. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1211–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thiery I, Delécluse A, Tamayo M C, Orduz S. Identification of a gene for Cyt1A-like hemolysin from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. medellin and expression in a crystal-negative B. thuringiensis strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:468–473. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.468-473.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thorne L, Garduno F, Thompson T, Decker D, Zounes M, Wild M, Walfield A M, Pollock T J. Structural similarity between the Lepidoptera- and Diptera-specific insecticidal endotoxin genes of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. “kurstaki” and “israelensis.”. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:801–811. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.801-811.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tungpradubkul S, Settasatien C, Panyim S. The complete nucleotide sequence of a 130 kDa mosquito-larvicidal delta-endotoxin gene of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1637–1638. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.4.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Udayasuriyan V, Nakamura A, Mori H, Masaki H, Uozumi T. Cloning of a new cryIA(a) gene from Bacillus thuringiensis strain FU-2-7 and analysis of chimeric cryIA(a) proteins for toxicity. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:830–835. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Van Mellaert, H., J. Botterman, J. Van Rie, and H. Joos. January 1991. European Patent EP Office no. 0408403.

- 115.Visser B, Munsterman E, Stoker A, Dirkse W G. A novel Bacillus thuringiensis gene encoding a Spodoptera exigua-specific crystal protein. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6783–6788. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6783-6788.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Von Tersch, M. A., and J. M. Gonzalez. October 1994. U.S. patent 5,356,623.

- 117.Von Tersch M A, Robbins H L, Jany C S, Johnson T B. Insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kenyae: gene cloning and characterization and comparison with B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki CryIA(c) toxins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:349–358. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.349-358.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Waalwijk C, Dullemans A M, vanWorkum M E S, Visser B. Molecular cloning and the nucleotide sequence of the Mr28,000 crystal protein gene of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8207–8217. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.22.8207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wabiko H, Raymond K C, Bulla L A., Jr Bacillus thuringiensis entomocidal protoxin gene sequence and gene product analysis. DNA. 1986;5:305–314. doi: 10.1089/dna.1986.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ward E S, Ellar D J. Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis delta-endotoxin: nucleotide sequence and characterization of the transcripts in Bacillus thuringiensis and Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ward E S, Ellar D J. Nucleotide sequence of a Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis gene encoding a 130 kDa delta-endotoxin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7195. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wasano, N., and M. Ohba. 1998. Unpublished observation.

- 122a.White J A, Maltais L J, Nebert D W. An increasingly urgent need for standardized gene nomenclature. 1998. http://genetics.nature.com/web_specials/nomen/nomen_article.html See: http://genetics.nature.com/web_specials/nomen/nomen_article.html. . [Google Scholar]

- 123.Widner W R, Whiteley H R. Two highly related insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki possess different host range specificities. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:965–974. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.965-974.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wu D, Cao X L, Bai Y Y, Aronson A I. Sequence of an operon containing a novel δ-endotoxin gene from Bacillus thuringiensis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;81:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90466-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yamamoto T, Watkinson I A, Kim L, Sage M V, Stratton R, Akande N, Li Y, Ma D-P, Roe B A. Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for a 130-kDa mosquitocidal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis. Gene. 1988;66:107–120. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang J, Hodgman T C, Krieger L, Schnetter W, Schairer H U. Cloning and analysis of the first cry gene from Bacillus popilliae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4336–4341. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4336-4341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]