Abstract

Background –

Outcomes of ventricular tachycardia (VT) ablation have been described in clinical trials and single-center studies. We assessed the safety of VT ablation in clinical practice.

Methods and Results –

Using administrative hospitalization data between 1994–2011 we identified hospitalizations with primary diagnosis of VT (ICD-9 CM code: 427.1) and cardiac ablation (ICD-9 CM code: 37.34). We quantified in-hospital adverse events (AEs) including death, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, pericardial complications, hematoma or hemorrhage, blood transfusion or cardiogenic shock. Secondary outcomes included major adverse events (MAE) (stroke, tamponade or death) and death. Multivariable mixed effects models identified patient and hospital characteristics associated with AEs.Of 9699 hospitalizations with VT ablations (age 56.5±17.6; 60.1% male), AEs were reported in 825 (8.5%), MAEs in 295 (3.0%) and death in 110 (1.1%). Heart failure had the strongest association with death (OR 5.52, 95% Cl 2.97–10.3) and MAE (OR 2.99, 95% Cl 2.15–4.16). Anemia (OR 4.84, 95% Cl 3.79–6.19) and unscheduled admission (OR 1.64, 95% Cl 1.37–1.97) were associated with AEs. Over the study period, incidence of AEs increased from 9.2% to 12.8% as did the burden of AE risk factors (0.034 patient/year, p<0.001). Hospital volume>25 cases/year was associated with fewer AEs compared with lower volume centers (6.4% vs. 8.8%, p=0.008).

Conclusions –

VT ablation-associated AE rates in clinical practice are similar to those reported in the literature. Over time rates have increased as have the number of AE risk factors per patient. Ablations done electively and at hospitals with higher procedural volume are associated with lower incidence of AEs.

Keywords: ablation, tachyarrhythmia, complication

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is now performed throughout the United States in both community and tertiary medical centers, and utilization of this procedure has increased over the last decade1,2. Previous studies suggest that patients without structural heart disease experience greater procedural success and fewer peri-procedural complications3–14, but little more is known about the factors that predispose patients to complications. While a recent observational study assessed the incidence of complications in patients with post-infarct VT1, the vast majority of literature addressing complications of VT ablation comes from randomized trials or high-volume single center retrospective studies3–16.With their small sample sizes and relatively low absolute numbers of adverse events, these publications preclude conclusions regarding clinical and institutional characteristics associated with peri-procedural adverse events or changes in event rates over time. Using publicly available hospital discharge data from multiple states in the United States, we assessed the frequency with which in-hospital adverse events occurred in association with VT ablation. We sought to characterize patient- and systems-level characteristics associated with in-hospital adverse outcomes as well as trends in patient characteristics and outcomes over time.

Methods

This a De-identified hospital discharge data were obtained from California (2000–2011)17, New York (1994–2007)18, Vermont (2002–2011)19, New Hampshire (1999–2007)20, West Virginia (2003–2007)21 and New Jersey (1997–2011)22 We included all hospital encounters with an endo- vascular cardiac ablation (International Classification of Diseases-9, Clinical Modification code [ICD-9]: 37.34) and a primary discharge diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia (ICD-9 CM code: 427.1)1,23. All other hospital records were excluded. All ICD-9 CM codes used in this analysis are found in supplemental table.

The primary outcome for this study was any in-hospital peri-procedural adverse event (AE) defined as death, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, pericardial complications defined as pericarditis, hemopericardium, tamponade, or pericardiocentesis, post-procedural hematoma,, hemorrhage or cardiac complications, blood transfusion, or cardiogenic shock. These diagnoses were chosen because they were considered much more likely to be procedural complications than other potential complications such as worsening to present concomitantly with VT, such as worsening heart failure (HF), respiratory failure, or heart block. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital death and a composite outcome of major adverse events (MAE) including cardiogenic shock, in-hospital death, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cardiac tamponade or need for pericardiocentesis.

Baseline patient characteristics including route of admission were determined using dataset documentation. Patients were classified as having HF and coronary artery disease (CAD), HF without CAD, congenital heart disease or no structural heart disease. Use of electroanatomical mapping (ICD-9 CM procedure code 37.27) was also determined. Annual volume of VT ablations by hospital was quantified to determine the relationship between hospital procedure volume and AEs. Regional trends in average number of cases per center and AE were also determined.

Statistical analysis

Associations between primary and secondary outcomes and baseline demographics, comorbidities, route of admission, year of hospitalization, and region were modeled using a multivariable mixed effects model with random effects terms for state and hospital using forward selection. All patient characteristics with a chi-squared p-value<0.05 between patients with no event and with an event were included in the univariate mixed effects binomial regression models for each outcome. An entry criterion of p<0.05 in univariate analysis was used for multivariable analysis.

Harmonization of demographics, in-hospital outcomes, and diagnosis, and procedure codes was performed using MySQL Server (version 5.5.24). All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical package (version 3.1.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna Austria). Specifically, the glmer function in the lme4 package was used to apply univariate and multivariable mixed effects models using a binomial distribution for all outcomes. De-identification procedures in California resulted in large numbers of hospitalizations with missing data on age, race and gender. A sensitivity analysis was performed using data only from the state of New York and New Jersey, which reported virtually no missing demographic data (0% age, 0% gender, 7.9% race missing), to confirm the findings of the primary analysis. The annual incident rate for number of risk factors (RF) per patient was calculated using a mixed effects Poisson regression model. Outcomes trends were adjusted according to presence of risk factors on an individual hospitalization basis using multivariable mixed effects binomial regression models. Volume-outcome analyses were conducted using logistic regression (glm function) due to the inclusion of the hospital-specific volume term int the predictive model. Relationships between annual VT ablation volume of <10, 10–25, and >25 were quantified based on recently published data suggesting a relationship between these VT ablation volumes and in-hospital complications1. Data regarding proceduralist volume were not available.

Results

Of 116,350,103 hospitalizations from the combined data sources, there were 150,520 hospitalizations (1.3%) with a primary diagnosis of VT of which 9699 (0.008% of all hospitalizations; 6.4% of hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of VT) reported intracardiac ablation. Baseline characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Data on age, gender and race were not available in 19.6%, 19.1% and 27.6% of hospitalizations, respectively due to state-specific de-identification procedures. Excluding hospitalizations with missing data, the overall demographics of VT ablation hospitalizations reported predominantly white race (n=4827, 69.3%, 2734 missing), male gender (n=4716, 60.1%, 1851 missing) and over the age of 50 (n=5533, 67.2%, 1462 missing).

Table 1:

Characteristics associated with adverse events, N (%)

| Characteristic | All 9699 | Any complication 825 (8.5) | Major adverse event 295 (3.0) | Death 110 (1.1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | ||||

| < 18 | 177 (1.8) | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 18–29 | 505 (5.2) | 9 (1) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 30–39 | 745 (7.7) | 17 (2) | 6 (2) | 3 (3) |

| 40–49 | 1276 (13.2) | 58 (7) | 23 (8) | 4 (4) |

| 50–59 | 1568 (16.2) | 93 (11) | 31 (11) | 6 (5) |

| 60–69 | 1763 (18.2) | 188 (23) | 61 (21) | 24 (22) |

| >70 | 2202 (22.7) | 304 (37) | 112 (38) | 48 (44) |

| Age NA | 1462 (15.2) | 152 (18) | 61 (21) | 25 (23) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4716 (48.6) | 433 (52) | 148 (50) | 64 (58) |

| Female | 3132 (32.3) | 190 (23) | 60 (20) | 12 (11) |

| Gender NA | 1851 (19.1) | 202 (24) | 87 (29) | 34 (31) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 4827 (49.8) | 386 (47) | 116(39) | 48 (44) |

| Black | 1081 (11.1) | 93 (11) | 37 (13) | 15 (14) |

| Hispanic | 538 (5.5) | 49 (6) | 23 (8) | 5 (5) |

| Other Race | 519 (5.4) | 28 (3) | 11 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Race NA | 2734 (28.2) | 269 (33) | 108 (37) | 39 (35) |

| Structural Heart Disease | ||||

| None | 6635 (68.4) | 372 (45) | 97 (33) | 19 (17) |

| Congenital heart disease | 154 (1.6) | 12 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| HF, no CAD | 1392 (14.4) | 173 (21) | 86 (29) | 40 (36) |

| HF, CAD | 1518 (25.0) | 268 (32) | 109 (37) | 51 (36) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HTN | 3117 (32.1) | 281 (34) | 88 (30) | 26 (23) |

| DM | 1454 (15.0) | 197 (24) | 74 (25) | 29 (26) |

| CAD | 3174 (32.7) | 436 (53) | 144 (49) | 61 (55) |

| Anemia | 528 (5.4) | 196 (24) | 67 (23) | 31 (28) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1481 (15.3) | 218 (26) | 71 (24) | 33 (30) |

| Admission characteristics | ||||

| Admit from home | 5682 (58.6) | 338 (41) | 128 (43) | 25 (23) |

| Hospital transfer | 1977 (20.4) | 241 (29) | 81 (27) | 45 (41) |

| Admit from ED | 2015 (20.8) | 243 (29) | 85 (29) | 40 (36) |

| Admit source NA | 25 (0.3) | 3 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Advanced technology | ||||

| Cardiac mapping | 5890 (60.7) | 525 (64) | 216 (73) | 72 (65) |

NA = Not Available; HTN = Hypertension; HF = Heart Failure; ED = Emergency Department; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease

Of the 9699 hospitalizations with VT ablation, 825 (8.5%) were associated with in-hospital AEs, 295 (36.1% of AEs, 3.0% of hospitalizations) of which were MAEs. Death occurred in 110 (1.1%) hospitalizations. More than one AE was reported in 259 (2.7%) hospitalizations, and more than one MAE was reported in 63 (0.6%). Need for blood transfusion was the most common adverse event associated with VT ablation, occurring in 224 (2.3%) hospitalizations. In chi-squared analysis, age>60 and male gender were associated with higher rates of adverse events of any sort, as were structural heart disease (congenital heart disease or HF+/−CAD), diabetes mellitus, and atrial fibrillation. The majority of ablations were performed during hospitalizations of patients without structural heart disease (6635 total, 68% of hospitalizations) with event rates of 5.6% for any AE, 1.4% for MAE, and 0.3% for in-hospital death. Ablation performed during hospitalization of patients with structural heart disease was associated with event rates of 453 (14.7%) for AE, 198 (6.5%) for MAE and 31 (3.0%) for in-hospital death (p<0.001 for all compared with no structural heart disease). Patients with HF, but no CAD (n=1392, 14.4%) had gross event rates of 173 (12.4%), 86 (6.2%) and 40 (2.9%) for AE, MAE and in-hospital death, respectively, whereas patients with both HF and CAD (n=1518, 15.7%) had gross rates of 268 (17.7%), 109 (7.2%) and 51 (3.4%). Rate of AEs was significantly greater in HF patients with CAD vs. no CAD (p<0.001), but rates of MAE and death were not significantly different. Rates of peri-procedural AE and MAE increased over time as depicted in Figure 1. Likelihood of in-hospital AEs increased by an odds ratio (OR) of 1.04 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00–1.07) per year (p<0.05), and MAEs increased by an OR of 1.07 (95% CI 1.01–1.4) per year (p<0.001). Odds of in-hospital mortality did not increase significantly over time (p=0.86). Advancing age, HF +/−CAD, anemia, atrial fibrillation, and admission via transfer or the emergency department (ED) remained independent predictors of AEs, MAEs, and death in multivariable analysis as demonstrated in Table 2. HF without CAD had the strongest association with death (OR 6.36 95% CI 3.31–12.2, p<0.001), and HF with CAD had the strongest association with MAE (OR 3.10; 95% CI 2.12–4.54, p <0.001). Anemia (OR 4.84; 95% CI 3.79–6.19, p <0.001) was the comorbid condition most associated with AEs. Women were noted to have lower multivariable odds of death (OR 0.47, 0.25–0.90, p<0.05) than men. Hospitalizations beginning with admission from the ED were associated with an increased multivariable odds ratio of AE (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.38–2.08, p<0.001), MAE (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.13–2.24, p<0.01) and death (OR 3.13, 95% CI 1.73–5.68, p<0.001) than were direct admissions from home. Transfers from other facilities were also associated with an increased odds of AE (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.26–1.98, p<0.001) and death (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.48–5.29, p<0.01) but not MAE (p=0.38) relative to direct admissions from home. When considering all multivariable predictors except for admission source, the presence of ≥ 2 RFs was associated with significantly greater likelihood of AE (OR 4.20, 95% CI 3.61–4.87), MAE (OR 4.50, 95% CI 3.55–5.71) and in-hospital mortality (OR 8.47, 95% CI 5.47–13.1, p<0.001 for all). Utilization of electroanatomical mapping increased from 307/609 (50.4%) cases in 1994 to 599/848 (70.6%) of cases in 2007 (p<0.001 for trend) but showed no significant association with rates of adverse outcomes. Sensitivity analysis using only data from New York and New Jersey, which had few missing demographic data confirmed 7/7 multivariable predictors of AE, 4/5 multivariable predictors of MAE (exception: year, OR 1.05 p<0.05 vs. OR 1.05, p=0.1), and 5/7 multivariable predictors of death (exceptions: female OR 47, p<0.05 vs. OR 0.53, p=0.1 and hospital transfer OR 3.26 p<0.01 vs. OR 1.90, p=0.1).

Figure 1:

Rates of adverse events, major adverse events, and death over time

Table 2a:

Multivariable mixed effects model of characteristics associated with adverse events

| Adverse Event | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristic | Univariate OR | p-value | Multivariable OR | p-value |

| Age ≥ 60 vs. < 60 years | 3.23 (2.70–3.87) | <0.001 | 2.20 (1.80–2.70) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.66 (0.57–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.75–1.11) | 0.37 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | - | - |

| Black | 1.19 (0.91–1.55) | 0.21 | - | - |

| Hispanic | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) | 0.51 | - | - |

| Other Race | 0.68 (0.46–1.03) | 0.66 | - | - |

| Structural Heart Disease | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| CHD | 1.34 (0.73–2.47) | 0.35 | 1.60 (0.81–3.16) | 0.18 |

| HF, no CAD | 2.38 (1.96–2.90) | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.25–2.02) | <0.001 |

| HF, CAD | 3.56 (2.99–4.25) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.48–2.30) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| DM | 1.83 (1.54–2.18) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.77–1.21) | 0.79 |

| Anemia | 7.63 (6.23–9.33) | <0.001 | 4.84 (3.79–6.19) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.17 (1.83–2.57) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.06–1.61) | 0.01 |

| Admission characteristics | ||||

| Admit from home | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Hospital transfer | 2.13 (1.77–2.56) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.26–1.98) | <0.001 |

| Admit from ED | 2.15 (1.79–2.57) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.38–2.08) | <0.001 |

| Year | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.16 |

HF = Heart Failure; ED = Emergency Department; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease; CHD = Congenital Heart Disease

Route of admission

Patients admitted directly from home accounted for 5682 (58.6%) of all hospitalizations considered in the analysis, whereas admissions via the ED or by hospital transfer made up 2015 (20.8%) and 1977 (20.4%) of records analyzed, respectively. Characteristics of patients admitted by each of these three mechanisms are described in Table 3. Patients admitted from home were less likely to have structural heart disease, diabetes mellitus, anemia or atrial fibrillation (p<0.01 for all). Excluding the risk factor of admission source, patients admitted via the ED or by hospital transfer had a higher average number of RFs when compared to patients admitted from home (1.14, 1.18 and 0.74 RFs/patient, respectively, p<0.001). Patients admitted via the ED were more likely than patients admitted from home to have AE (12.1% vs 5.9%, p<0.01), MAE (4.2% vs 2.3%, p<0.01) or death (2.0% vs 0.4%, p<0.01). Rates of AE, MAE and death for patients transferred between hospitals were similar to those observed in patients admitted via the ED.

Table 3:

Case characteristics according to source of admission, N (%)

| ED | Transfer | Home | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristic | 2015 (21) | 1977 (20) | 5682 (59) | p-value |

| Age | <0.001 | |||

| <18 | 10 (0) | 14 (1) | 153 (3) | |

| 18–29 | 68 (3) | 54 (3) | 383 (7) | |

| 30–39 | 138 (7) | 96 (5) | 511 (9) | |

| 40–49 | 276 (14) | 188 (10) | 811 (14) | |

| 50–59 | 342(17) | 295 (15) | 930 (16) | |

| 60–69 | 442 (22) | 367 (19) | 954 (17) | |

| >70 | 606 (30) | 510 (26) | 1086 (19) | |

| Age NA | 133 (7) | 453 (23) | 854 (15) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 1164 (58) | 938 (47) | 2604 (46) | |

| Female | 660 (33) | 477 (24) | 1980 (35) | |

| Gender NA | 191 (9) | 562 (28) | 1098 (19) | |

| Race | 0.89 | |||

| White | 1148 (57) | 817 (41) | 2861 (50) | |

| Black | 249 (12) | 196 (10) | 635 (11) | |

| Hispanic | 136 (7) | 94 (5) | 308 (5) | |

| Other Race | 127 (6) | 93 (5) | 299 (5) | |

| Race NA | 355 (18) | 777 (39) | 1579 (28) | |

| Structural Heart Disease | <0.001 | |||

| None | 1219 (60) | 1120 (57) | 4278 (75) | |

| Congenital heart disease | 46 (2) | 37 (2) | 71 (1) | |

| HF, no CAD | 336 (17) | 369 (19) | 684 (12) | |

| HF, CAD | 414 (21) | 451 (23) | 649 (11) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| DM | 378 (19) | 410 (21) | 664 (12) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 177 (9) | 168 (8) | 182 (3) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 403 (20) | 394 (20) | 682 (12) | <0.001 |

| # AE risk factors | 0.7±0.9 | 2.1±1.0 | 2.2±1.0 | <0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Adverse events | 243 (12) | 241 (12) | 338 (6) | <0.001 |

| Major adverse event | 85 (4) | 81 (4) | 128 (2) | <0.001 |

| Death | 40 (2) | 45 (2) | 25 (0) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay, days | 6 [4–9] | 5 [3–8] | 1 [1–3} | <0.001 |

NA = Not Available; HTN = Hypertension; HF = Heart Failure; ED = Emergency Department; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease

Hospital ablation volume

Hospital volume was defined as average annual volume for all years that each hospital reported performing at least one ablation. In total, 200 unique hospitals reported performing VT ablation during the study period with a cumulative median of 4 cases/yr. The median for average procedural volume was 2.9 cases/year (interquartile range 1.5–5.8 and the majority of procedures 7047 (72.7) were performed in hospitals of the highest volume quartile (>5.8 procedures annually on average). Table 4 describes the characteristics of patients undergoing ablation according to volume <10, 10–25, and >25 cases/year. When compared to the admissions to hospitals with <10 cases/year, patients hospitalized in hospitals performing >25 procedures/year less likely to be admitted via the ED (15.7% vs. 24.7%, p<0.001), to have diabetes mellitus (12.7% vs. 15.9%, p<0.01) or to have anemia (3.8% vs. 5.7%, p<0.01), and they were more likely to be white (80.3% vs. 66.4%, p<0.001). Patients hospitalized at highest volume centers also had fewer AE risk factors on average than the lowest volume centers (1.3±1.2 vs. 1.4±1.2, p=0.036)

Table 4:

Case characteristics according to average annual hospital ablation volume, N (%)

| < 10 cases/year | 10–25 cases/year | > 25 cases/year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristic | 5083 (52) | 3498 (36) | 1118 (12) | p-value |

| Age | <0.001 | |||

| < 18 | 66 (1) | 97 (3) | 14 (1) | |

| 18–29 | 253 (5) | 200 (6) | 52 (5) | |

| 30–39 | 359 (7) | 283 (8) | 103 (9) | |

| 40–49 | 670 (13) | 460 (13) | 146 (13) | |

| 50–59 | 863 (17) | 528 (15) | 177 (16) | |

| 60–69 | 964 (19) | 610 (17) | 207 (19) | |

| >70 | 1281 (25) | 696 (20) | 225 (20) | |

| Age NA | 645 (13) | 624 (18) | 194 (17) | |

| Gender | 0.017 | |||

| Male | 2612 (51) | 1579 (45) | 525 (47) | |

| Female | 1632 (32) | 1130 (32) | 370 (33) | |

| Gender NA | 839 (17) | 789 (23) | 223 (20) | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| White | 2434 (48) | 1692 (48) | 701 (63) | |

| Black | 705 (14) | 324 (9) | 52 (5) | |

| Hispanic | 305 (6) | 163 (5) | 70 (6) | |

| Other Race | 224 (4) | 245 (7) | 50 (4) | |

| Race NA | 1415 (28) | 1074 (31) | 245 (22) | |

| Structural Heart Disease | 0.003 | |||

| None | 3452 (68) | 2435 (70) | 748 (67) | |

| Congenital heart disease | 65 (1) | 70 (2) | 19 (2) | |

| HF, no CAD | 768 (15) | 443 (13) | 181 (16) | |

| HF, CAD | 798 (16) | 550 (16) | 170 (15) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| DM | 806 (16) | 506 (14) | 14.2 (13) | 0.015 |

| Anemia | 291 (6) | 195 (6) | 42 (4) | 0.029 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 795 (16) | 504 (14) | 182 (16) | 0.18 |

| Admission characteristics | <0.001 | |||

| Admit from home | 3032 (60) | 1957 (56) | 693 (62) | |

| Hospital transfer | 777 (15) | 951 (27) | 249 (22) | |

| Admit from ED | 1250 (25) | 590 (17) | 175 (16) | |

| # AE risk factors | 1.4±1.2 | 1.3± 1.1 | 1.3±1.2 | 0.035 |

| Cardiac mapping Outcomes | 3133 (62) | 2003 (57) | 754 (67) | <0.001 |

| Adverse events | 448 (9) | 305 (9) | 72 (6) | 0.031 |

| Major adverse events | 145 (3) | 118 (3) | 32 (3) | 0.36 |

| Death | 56 (1) | 46 (1) | 8 (1) | 0.24 |

| Length of stay, days | 4.6±7.0 | 4.7±6.6 | 4.6±5.9 | 0.52 |

NA = Not Available; HTN = Hypertension; HF = Heart Failure; ED = Emergency Department; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease

Significant differences in AE rate were also observed between hospitals with <10 (n=448, 8.8%), 10–25 (n=305, 8.7%) and >25 (n=72, 6.4%) hospitalizations for VT ablation/year (chi-squared p=0.03), but there were no significant difference in rates of MAE or in-hospital death. The difference in AEs was driven by “high volume” hospitals with > 25 hospitalizations/year who reported a significantly lower overall unadjusted AE rate (6.4% vs 8.8% vs. all other hospitals; OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56–0.92, p=0.008), although only 3 hospitals in the six states had average annual volumes of >25 procedures per year. Hospital volume >25 cases/year also remained significantly associated with a lower rate of AE when adjusted for number of AE risk factors (OR 0.72 95% CI 0.56–0.93, p=0.013). There was no association between hospital volume and MAE (p=0.36) or in-hospital death rates.

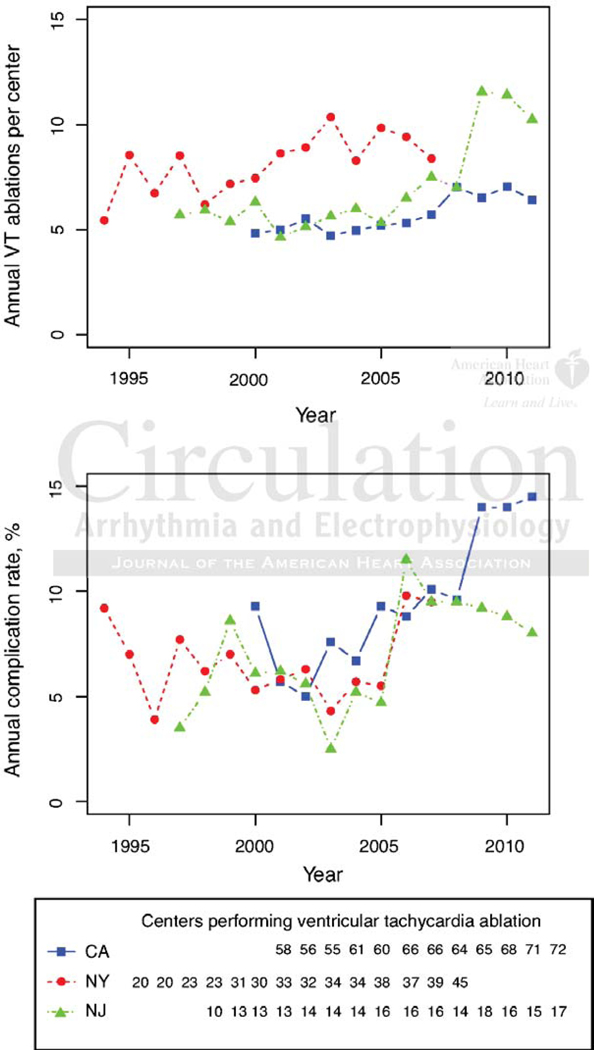

There was a small, homogeneous increase in the mean number of VT ablations per center in the three highest volume states (New York, California and New Jersey) between the years 1994–2007 with a subsequent abrupt increase in the number of cases/center in New Jersey from 2007–2011 (Figure 2). Despite these modest increases in hospital volumes, ablation-associated adverse events increased at similar rates across all three states with the exception of the last 4 years when AE rates in NJ and CA appeared to diverge in association with an increase in the number of cases/center in NJ compared to CA. When the average number of cases per center by state was included in a multivariable logistic regression along with year of hospitalization, the number of high risk features and the state, an increase of 1 case/center was associated with lower odds of AE (OR 0.94 95% CI 0.90–0.98, p=0.003), but no significant differences in MAE (p=0.21) or mortality (p=0.38).

Figure 2:

Ablation procedures/center and associated statewide adverse event rates in California, New York and New Jersey

Trends in adverse events and patient complexity

The percentage of patients with ≥2 RFs (‘high risk’) for AEs also increased throughout the period studied from 15.6% to 39.9% (Figure 3). This corresponded to a Poisson regression incident rate of 1.025 (95% CI 1.02–1.03, p<0.001) annually. The increase in percentage of patients who were high risk was greatest among patients admitted from home (6.5% to 34.8%, incident rate 1.057 95% CI 1.04–1.08, p<0.001), although the annual increase in percentage of high-risk patients was also significant for transfer patients (26.3% to 51.2%, incident rate 1.01 95% CI 1.00–1.02, p=0.006). The percentage of ED patients with ≥2 risk factors was more variable but did increased overall during the study period (incident rate 1.01 95% CI 1.01–1.02, p=0.002). After adjusting for the increase in RF, annual increases in AE (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05, p<0.001) and MAE (OR 1.10 95 1.07–1.14, p<0.001) remained significant.

Figure 3:

Trends in percentage of patients at elevated risk of complications according to admission source

Discussion

Over a 19 year period, approximately 8.5% of VT ablations were associated with AEs, including MAEs in 3% of procedure-related hospitalizations with higher rates of complications including in-hospital death observed in patients with structural heart disease. These rates are within the range reported in most single center studies and randomized controlled trials of VT ablation, though rates in these publications vary widely3–14,24 In particular, the overall MAE rate reported in the present study for patients with structural heart disease (6.2%) is similar to the rate of 6.0% in the most recent report from Brigham and Women’s Hospital where nearly 370 VT ablations were performed over a two year period14 and lower than was observed in largest multicenter trial of VT ablation24. In comparison to a recent report using data from the National Inpatient Survey examining patients undergoing ablation for post-infarct VT, we found higher AE and in-hospital death rates (17.6% vs 11.2%, and 3.3% vs 1.6%) (24), but MAE and in-hospital death rates were similar to those seen in clinical trials of ablation for recurrent VT with predominantly ischemic heart disease1,4,24 Overall, the odds of death among HF patients with or without CAD were significantly elevated when compared to odds of death in patients without structural heart disease, but statistically similar to one another. In patients without structural heart disease MAE rates were lower than that reported from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in a Spanish registry (1.4% vs 3.4% vs 3.4%), though the occurrence of in-hospital death was higher (0.3% vs 0% vs 0%)2,14.

We found an association between peri-procedural adverse events, advancing age and the presence structural heart disease with or without CAD in hospitalized patients undergoing VT ablation. These findings refute previous publications that advanced age is not associated with higher adverse event rates11,25 but support findings that structural heart disease is associated with higher rates of complications1,4,8,14,24,26. Interestingly, in contrast to published data on outcomes in acute coronary syndromes and catheterization which demonstrate higher adverse event rates in women when compared to men27,28, we found that female sex was associated with fewer adverse events after VT ablation.

Though adverse outcomes associated with VT ablation have increased over time, our data demonstrate concomitant increase in patient risk factors, which may explain part but not all of the observed trends in adverse events. The observed trend of increasing RFs in patients suggests that sicker patients are undergoing ablation, particularly those admitted from home who are undergoing elective ablation. Increased success rates and operator competence may contribute to this trend, although a different data source would be required to assess for procedural success. Further, improved procedural technique and technologies have the potential to offset some of the risks inherent to ablating sicker patients. Our data demonstrate increased use of electroanatomical mapping over time, but selection bias precludes assessment of mapping’s impact on adverse event rates.

Other surgical specialties have decreased complication rates by further concentrating higher-risk procedures in high volume centers. For instance in Germany minimum volume requirements for total knee replacement resulted in 22.5% and 44% risk reductions in wound infections and bleeding complications, respectively29. Within electrophysiology, lower complication rates have recently been reported in higher volume device implantation centers and amongst higher volume operators for device implantation and atrial fibrillation ablation23, 30,31.

Whether concentrating ablation volume to select centers is a practical approach to decreasing complication rates in VT ablation is not clear. Unlike the aforementioned elective procedures, VT ablation may be done urgently and emergently. In fact, we demonstrate that, in lower volume ablation centers, patients undergoing ablation were more likely to have been admitted via the ED than were patients ablated at higher volume centers. AE rates were also higher in lower volume centers, though it is unclear how much of this difference was attributable to patient selection and how much to provider or center proficiency. While there may be certain circumstances in which concentrating VT ablation in high-volume centers is challenging, Della Bella and colleagues have described a “VT unit” able to provide helicopter accessible, around-the-clock intensive care management by a team which included multiple electrophysiologists working in cooperation with HF specialists and cardiac surgeons32. While our data suggest that patient transfer is not associated with lower complication rates than those observed in patients admitted via the ED, not all patients were transferred to hospitals in the highest volume quartile and not all hospitals in the highest volume quartile may truly qualify as high volume VT ablation centers. Our data do suggest that the highest volume hospitals, defined here as those performing >25 procedures per year on average, do have lower complication rates, suggesting that further concentration of VT ablation as suggested by Della Bella may have merit in the United States.

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations inherent to all claims-based studies including unidentified confounders, misclassification and missing data due to state administrative procedures for de-identification. The lack of granularity in administrative data prevents assessment of important clinical and procedural characteristics, including VT mechanism and substrate (idiopathic vs. scar-related), cardiac site of the VT origin, left ventricular ejection fraction, and procedural equipment as well as limiting comparison to clinical trials and registries. Although patients admitted for premature ventricular complex ablation have had a different ICD-9 CM code than those admitted with a primary diagnosis of VT, we cannot differentiate between non-sustained VT and sustained or hemodynamically significant VT in this analysis nor can we exclude the possibility that patients undergoing ablation of premature ventricular complexes were included in the analysis. Data on the presence of chronic renal insufficiency was lacking due to a change in the ICD-9 CM codes during the study period. Discharge data sets do not allow for assessment of individual provider volume, which may better predict procedural outcomes than does institutional volume. De-identified hospital discharge data also does not permit for assessment of adverse events in patients presenting for more than one VT ablation on a per patient basis. Events reported here are assumed to be directly related to the ablation procedure but may be overestimates as causality cannot be proven. In addition, nonspecific conditions such as worsening HF or respiratory failure that might be procedural complications but could also be attributable to underlying comorbidities were excluded, potentially underestimating true adverse event rates, Finally, procedural success cannot be ascertained from this data, and so the balance of risks and benefits provided by VT ablation cannot be assessed.

Conclusion

Using a multi-state hospital discharge database we found that adverse events occurred in 8.5% of hospitalization during which ablation of ventricular tachycardia was performed. Major adverse events, including death, occurred in 3% of hospitalizations. Event rates in patients with and without structural heart disease were similar to those reported from high volume centers and in randomized controlled trials. Heart failure, anemia, increasing age, male sex and hospital admission via the emergency department were the traits most strongly associated with in-hospital adverse events. Gross rates of adverse events increased slightly over time, as did the average perpatient number of risk factors. Fewer adverse events were seen at higher volume centers.

Supplementary Material

Table 2b:

Multivariable mixed effects model of characteristics associated with major adverse events

| Major adverse events | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristic | Univariate OR | p-value | Multivariable OR | p-value |

| Age ≥60 years | 3.12 (2.30–4.23) | <0.001 | 2.16 (1.48–3.15) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.62 (0.45–0.84) | <0.01 | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) | <0.68 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.65 (1.08–2.51) | <0.05 | 1.20 (0.79–1.83) | 0.4 |

| Hispanic | 1.78 (1.12–2.85) | <0.05 | 1.77 (1.09–2.86) | 0.02 |

| Other Race | 0.90 (0.48–1.70) | 0.74 | 1.24 (0.65–2.37) | 0.52 |

| Structural Heart Disease | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| CHD | 1.27 (0.39–4.17) | 0.69 | 1.31 (0.30–5.60) | 0.72 |

| HF, no CAD | 4.38 (3.22–5.95) | <0.001 | 2.57 (1.71–3.86) | <0.001 |

| HF, CAD | 5.13 (3.84–6.88) | <0.001 | 3.10 (2.12–4.54) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| DM | 1.85 ( 1.41–2.44) | <0.001 | 0.89 ( 0.61–1.30) | 0.55 |

| Anemia | 5.16 (3.83–6.96) | <0.001 | 2.45 (1.61–3.73) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.74 (1.32–2.31) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.73–1.50) | 0.79 |

| Admission characteristics | ||||

| Admit from home | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Hospital transfer | 1.74 (1.30–2.34) | <0.001 | 1.20 (0.80–1.81) | 0.38 |

| Admit from ED | 1.90 (1.42–2.53) | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.13–2.24) | <0.01 |

| Year | 1.13 (1.10–1.17) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | <0.05 |

HF = Heart Failure; ED = Emergency Department; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease; CHD = Congenital Heart Disease

Table 2c:

Multivariable mixed effects model of characteristics associated with in-hospital death

| Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Death Characteristic | Univariate OR | p-value | Multivariable OR | p-value |

| Age ≥60 years | 6.02 (3.18–11.4) | <0.001 | 3.30 (1.67–6.51) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.29 (0.15–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.25–0.90) | <0.05 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | - | - |

| Black | 1.34 (0.67–2.68) | 0.41 | - | - |

| Hispanic | 0.90 (0.32–2.52) | 0.85 | - | - |

| Other Race | 0.56 (0.15–2.03) | 0.38 | - | - |

| Structural Heart Disease | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| CHD | - | 0.99 | - | 0.99 |

| HF, no CAD | 9.71 (5.4–17.5) | <0.001 | 6.36 (3.31–12.2) | <0.001 |

| HF, CAD | 11.6 (6.58–20.4) | <0.001 | 4.67 (2.42–8.99) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| DM | 1.95 (1.23–3.08) | <0.01 | 0.82 (0.46–1.47) | 0.51 |

| Anemia | 6.33 (3.99–10.0) | <0.01 | 3.14 (1.75–5.63) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.32 (1.49–3.60) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.67–1.87) | 0.66 |

| Admission characteristics | ||||

| Admit from home | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Hospital transfer | 4.92 (2.89–8.36) | <0.001 | 2.80 (1.48–5.29) | <0.01 |

| Admit from ED | 4.37 (2.54–7.50) | <0.001 | 3.13 (1.73–5.68) | <0.001 |

| Year | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | <0.05 | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.55 |

HF = Heart Failure; ED = Emergency Department; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease; CHD = Congenital Heart Disease

Funding Sources:

Dr. Kao was supported by NIH Grant 2 T32 HL007822-12 and Jacqueline’s Research Fund funded by the Jacqueline Marie Leaffer Foundation and the University of Colorado Center for Women’s Health Research. Dr. Turakhia was supported by a VA Career Development Award (CDA09027-1) and AHA National Scientist Development Grant AHA #09SDG2250647). The content and opinions expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: William Sauer acknowledges receiving research and educational support from Medtronic, St Jude, Boston Scientific and Biosense Webster. All others have none.

References:

- 1.Palaniswamy C, Kolte D, Harikrishnan P, Khera S, Aronow WS, Mujib M, Mellana WM, Eugenio P, Lessner S, Ferrick A, Fonarow GC, Ahmed A, Cooper HA, Frishman WH, Panza JA, Iwai S. Catheter Ablation of Post-Infarction Ventricular Tachycardia: Ten-Year Trends in Utilization, In-Hospital Complications, and In-Hospital Mortality in the United States. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:2056–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Loma-Osorio AF, Diaz-Infante E, Gallego AM. Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry. 12th Official Report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Electrophysiology and Arrhythmias (2012). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calkins H, Kalbfleisch SJ, el-Atassi R, Langberg JJ, Morady F. Relation between efficacy of radiofrequency catheter ablation and site of origin of idiopathic ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calkins H, Epstein A, Packer D, Arria AM, Hummel J, Gilligan DM, Trusso J, Carlso M, Luceri R, Kopelman H, Wilber D, Wharton JM, Stevenson W. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease using cooled radiofrequency energy: results of a prospective multicenter study. Cooled RF Multi Center Investigators Group. J Am Coll Cadiol. 2000;35:1905–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi S, Wilber DJ. Ablation of idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia: current perspectives. JCardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16 Suppl 1:S52–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuck KH, Schaumann A, Eckardt L, Willems S, Ventura R, Delacrétaz E, Pitschner HF, Kautzner J, Schumacher B, Hansen PS. Catheter ablation of stable ventricular tachycardia before defibrillator implantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH): a multi centre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morady F, Harvey M, Kalbfleisch SJ, el-Atassi R, Calkins H, Langberg JJ. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1993;87:363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokuda M, Tedrow UB, Kojodjojo P, Inada K, Koplan BA, Michaud GF, John RM, Epstein LM, Stevenson WG. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in nonischemic heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tokuda M, Kojodjojo P, Tung S, Tedrow UB, Nof E, Inada K, Koplan BA, Michaud GF, John RM, Epstein LM, Stevenson WG. Acute failure of catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia due to structural heart disease: causes and significance. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tung R, Josephson ME, Reddy V, Reynolds MR, SMASH-VT Investigators. Influence of clinical and procedural predictors on ventricular tachycardia ablation outcomes: an analysis from the substrate mapping and ablation in Sinus Rhythm to Halt Ventricular Tachycardia Trial (SMASH-VT). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viana-Tejedor A, Merino JL, Pérez-Silva A, León RC, Reviriego SM, Caraballo ED, Peinado RP, Lopez-Sendon JL.. Effectiveness of catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in elderly patients with structural heart disease. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delacrétaz E, Brenner R, Schaumann A, Eckardt L, Willems S, Pitschner HF, Kautzner J, Schumacher B, Hansen PS, Kuck KH. Catheter ablation of stable ventricular tachycardia before defibrillator implantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH): an on-treatment analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Donnell D, Cox D, Bourke J, Mitchell L, Furniss S. Clinical and electrophysiological differences between patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia and right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohnen M, Stevenson WG, Tedrow UB, Michaud GF, John RM, Epstein LM, Albert CM, Koplan BA. Incidence and predictors of major complications from contemporary catheter ablation to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1661–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lü F, Eckman PM, Liao KK, Apostolidou I, John R, Chen T, Das GS, Francis GS, Lei H, Trohman RG, Benditt DG. Catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia with mechanical circulatory support. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:3859–3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P, Richardson AW, Taborsky M, Jongnarangsin K, Kravolec S, Sediva L, Ruskin JN, Josephson ME. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2657–2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patient Discharge Data [ [Internet]]. OSHPD Website. California Health and Human Services Agency: Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development; [cited 2013], Retrieved from: http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Products/PatDis.

- 18.Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) [ [Internet]]. Department of Health, New York State, [cited 2013], Retrieved from: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/spares/. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermont Hospitalization Utilization Reports and Discharge Data Sets [ [Internet]]. Department of Health, Agency of Human Services, Vermont. [cited 2013]. Retrieved from: http://healthvermont.gov/research/hospital-utilization.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hospital Discharge Data [ [Internet]]. New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. [cited 2013]. Retrieved from: http://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/hsdm/requests.htm.

- 21.WV Hospital Discharge Data [ [Internet]]. West Virginia Health Care Authority. [cited 2013]. Retrieved from: http://www.hca.wv.gov/data/requestdata/Pages/default.aspx.

- 22.Hospital Patient Discharge Data [ [Internet]]. Office of Health Care Quality Assessment, New Jersey: Department of Health. [cited 2013]. Retrieved from: http://www.state.nj.us/health/healthcarequality. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deshmukh A, Patel NJ, Pant S, Shah N, Chothani A, Mehta K, Grover P, Singh V, Vallurupalli S, Savani GT, Badheka A, Tuliani T, Dabhadkar K, Dibu G, Reddy YM, Sewani A, Kowalski M, Mitrani R, Paydak H, Viles-Gonzalez JF. In-hospital complications associated with catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in the United States between 2000 and 2010: analysis of 93 801 procedures. Circulation. 2013;128:2104–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevenson WG, Wilber DJ, Natale A, Jackman WM, Marchlinski FE, Talbert T, Gonzalez MD, Worley SJ, Daoud EG, Hwang C, Schuger C, Bump TE, Jazayeri M, Tomassoni GF, Kopelman HA, Soejima K, Nakagawa H. Irrigated Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation Guided by Electroanatomic Mapping for Recurrent Ventricular Tachycardia After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2773–2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inada K, Roberts-Thomson KC, Seiler J, Steven D, Tedrow UB, Koplan BA, Stevenson WG. Mortality and safety of catheter ablation for antiarrhythmic drug-refractory ventricular tachycardia in elderly patients with coronary artery disease. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinov B, Fiedler L, Schönbauer R, Bollmann A, Rolf S, Piorkowski C, Hindricks G, Arya A. Outcomes in Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Dilated Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Compared With Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: Results From the Prospective Heart Centre of Leipzig VT (HELP-VT) Study. Circulation. 2014;129:728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akhter N, Milford-Beland S, Roe MT, Piana RN, Kao J, Shroff A. Gender differences among patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR). Am Heart J. 2009;157:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daugherty SL, Thompson LE, Kim S, Rao SV, Subherwal S, Tsai TT, Messenger JC, Masoudi FA. Patterns of use and comparative effectiveness of bleeding avoidance strategies in men and women following percutaneous coronary interventions: an observational study from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2070–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohmann C, Verde PE, Blum K, Fischer B, de Cruppé W, Geraedts M. Two short-term outcomes after instituting a national regulation regarding minimum procedural volumes for total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkfeldt RE, Johansen JB, Nohr EA, Jørgensen OD, Nielsen JC. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1186–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Khatib S, Lucas FL, Jollis JG, Malenka DJ, Wennberg DE. The Relation Between Patients’ Outcomes and the Volume of Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation Procedures Performed by Physicians Treating Medicare Beneficiaries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1536–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Della Bella P, Baratto F, Tsiachris D, Trevisi N, Vergara P, Bisceglia C, Petracca F, Carbucicchio C, Benussi S, Maisano F, Alfieri O, Pappalardo F, Zangrillo A, Maccabelli G. Management of ventricular tachycardia in the setting of a dedicated unit for the treatment of complex ventricular arrhythmias: long-term outcome after ablation. Circulation. 2013;127:1359–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.