Abstract

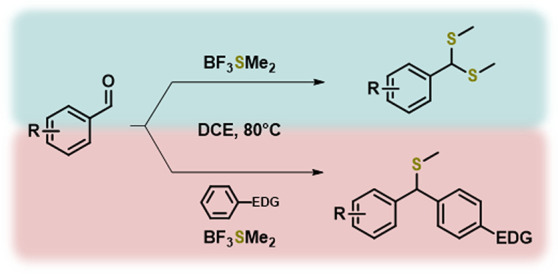

Herein, a method for thioacetalation using BF3SMe2 is presented. The method allows for convenient and odor-free transformation of aldehydes to methyl-dithioacetals, a simple but sparsely reported structural moiety, in good yields with a diverse set of aromatic aldehydes. In addition, a thiomethylative Friedel-Crafts reaction was discovered, affording thiomethylated diarylmethanes in good to excellent yields. The resulting diarylmethane core is of interest as it is found in many biologically active compounds, and its utility is further demonstrated as a novel precursor to unsymmetrical triarylmethanes. This work also highlights the usefulness and the synthetic capabilities of the readily available reagent BF3SMe2 beyond its reactivity profile as a dealkylation reagent.

Introduction

Boron trifluoride etherate is a commonly employed reagent in organic synthesis due to its combination of powerful Lewis acidity and ease of handling.1−5 In contrast, the related sulfur analogue boron trifluoride dimethyl sulfide (BF3SMe2) has received considerably less attention. Perhaps the most well-known and earliest reported use of this system is benzyl group cleavage6 using a combination of boron trifluoride etherate and dimethyl sulfide. The combined boron trifluoride complex has since been used almost exclusively for ether dealkylations.7−18 Some developments toward uses of the complex have nonetheless been accomplished, such as selective cleavage of di-tert-butylsilylene ethers,19 selective methoxy cleavage,20 and as a borylation reagent.21 Recently, we reported BF3SMe2 as a convenient thiomethylating reagent and also showed that it could reduce nitro groups in certain substrates.22 During our investigation, we also found that BF3SMe2 could produce methyl-dithioacetals from aldehydes albeit in a single example and in low yield.

Thioacetals are the sulfur analogue of the acetal group and are often employed as protecting groups to mask the electrophilic carbon of aldehydes and ketones as they offer increased acid stability.23 In addition to carbonyl protection, the thioacetal group can also be employed as a synthetic handle for other transformations and the most well-known example is the Corey–Seebach umpolung reaction.24,25 Generally, thioacetals are prepared via the Lewis acid (ZnCl2,26 BF3 etherate,27 AlCl3,28 and TiCl429) catalyzed addition of thiols to aldehydes and ketones. Thioacetals can also be accessed from other functional groups such as olefins,30 acetals,31,32 or propargylic carbons.33 Due to the odorous nature of thiols, there have been numerous efforts toward alleviation of this issue. Methods using solid-supported thioacetalation reagents have been reported34,35 as well as diacetyl ketene dithioacetals36−38 and derivatives thereof39−41 for achieving thioacetalation in odorless conditions. However, these methods are limited to cyclic thioacetals and require tedious preparation of the thioacetalating agents.

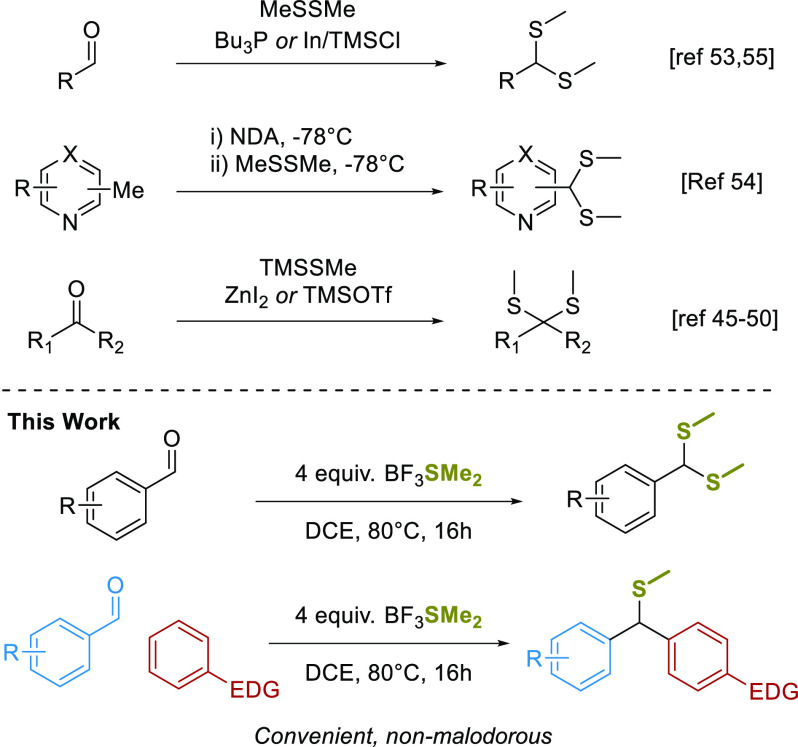

Advances have also been made in the field of thioacetalation, and there have been mild catalytic methods developed.31,42−52 However, despite being the structurally simplest thioacetal derivative, methyl dithioacetals are not found in these examples, most likely due to the highly odorous nature of methanethiol. Besides methanethiol, there are also methods utilizing dimethyldislufide53−55 to achieve methyl dithioacetals, although an unpleasant odor is associated with this reagent as well. There are examples that avoid this problem by using methylthiotrimethylsilane,56−61 although additional additives are often required and the reagent is rather expensive (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Overview of Synthetic Strategies To Access Methyl-dithioacetals.

Due to the usefulness of dithioacetals as a synthetic moiety in organic chemistry and the lack of convenient methods to access methyl dithioacetals, we set out to investigate the use of BF3SMe2 as a methyl-dithioacetalation reagent. We envisaged a convenient, odor-free method that would further broaden the utility of BF3SMe2 as a reagent in organic chemistry.

Results and Discussion

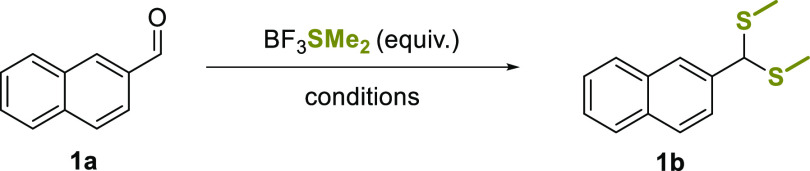

We began our investigation by screening reaction conditions using 2-napthaldehyde (1a) as the model substrate (Table 1). Initial attempts found that using 2 equiv of BF3SMe2 (2 mmol) at 60 °C resulted in 37% of the target dithioacetal 1b. It was also noted that concentration was important, as increasing the volume of solvent from 1 mL to 5 mL reduced the yield significantly to 10% (entry 2). Next, the effects of temperature were investigated, and we found that 80 °C increased the yield to 44% while increasing it further to 100 °C was detrimental and only traces of the product could be detected (LCMS analysis). With the optimal temperature found, we continued by increasing the amount of BF3SMe2, and gratifyingly 3 equiv increased the yield to 60%. Increasing the amount further to 4 equiv increased the yield to 68%, while 5 equiv only gave a slight increase of 71%, so 4 equiv was selected for further investigation. Lastly, increasing the reaction time did not give any further improvement, and control experiments removing the Lewis acid (entry 9) or using catalytic amounts of BF3OEt2 (entry 10) gave no observed reaction.

Table 1. Optimization of the Thioacetalation Reactiona.

| entry | solvent | equiv | time | temp. | yieldba |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DCM | 2 | 16 h | 60 °C | 37% |

| 2 | DCMc | 2 | 16 h | 60 °C | 10% |

| 3 | DCE | 2 | 16 h | 80 °C | 44% |

| 4 | DCE | 2 | 16 h | 100 °C | d |

| 5 | DCE | 3 | 16 h | 80 °C | 60% |

| 6 | DCE | 4 | 16 h | 80 °C | 68% |

| 7 | DCE | 5 | 16 h | 80 °C | 71% |

| 8 | DCE | 4 | 24 h | 80 °C | 68% |

| 9 | DCE | 4e | 16 h | 80 °C | f |

| 10 | DCE | 4g | 16 h | 80 °C | f |

Reactions performed at 0.5 mmol scale using 1 mL of solvent.

Isolated yield.

5 mL.

Not isolated.

In the absence of BF3.

No reaction.

Using 4 equiv SMe2 with 30 mol % catalytic loading of BF3OEt2.

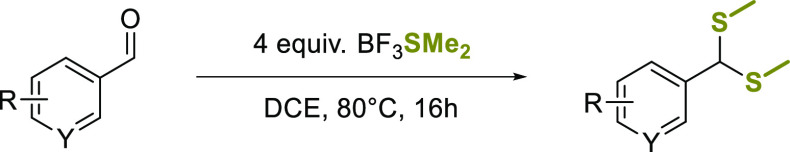

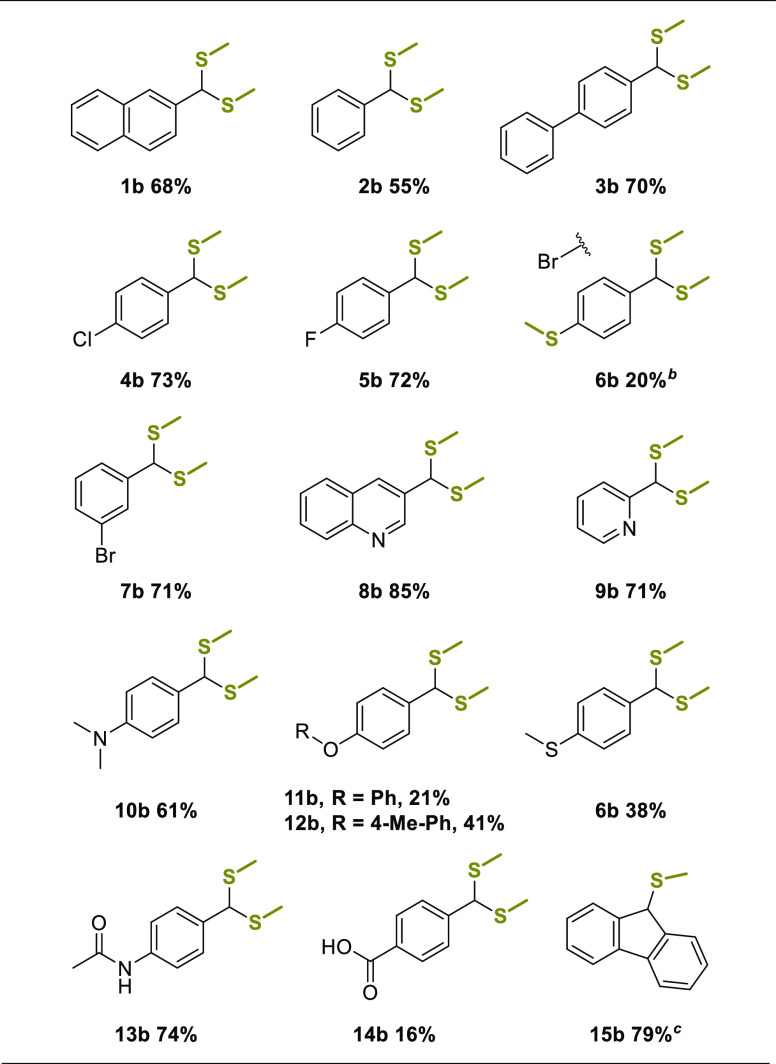

With suitable conditions in hand, the scope and limitations of the method were investigated (Table 2). Benzaldehyde and 4-phenylbenzaldehyde gave thioacetals 2b and 3b in moderate to good yield as did the halogenated substrates 4-chloro- and 4-fluorobenzaldehyde. Interestingly, 4-bromobenzaldehyde afforded the thiomethyl substituted product 6b, while 3-bromobenzaldehyde returned the expected thioacetal product 7b in good yield. This observation might be explained by aldehyde activation by BF3, followed by a Br abstraction by DMS (soft nucleophile/soft base),62 and attack on the formed DMS-Br complex (Scheme S1, the SI). Electron-poor aromatics quinoline-3-carboxaldehyde and 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde reacted smoothly to give the desired thioacetals in good yields. More electron-rich aldehydes resulted in low to moderate yields, where 4-(p-tolyloxy)benzaldehyde formed a stable dimethylsulfonium derivative as an additional product (12ba, SI). We believe that this transformation occurs via a DMS-mediated reduction,22 followed by a nucleophilic attack from an additional DMS molecule (Scheme S2, SI). Furthermore, 4-phenoxybenzaldehyde also afforded additional di- and trimeric products presumably resulting from substitution of a thiomethyl group at the 4-position of the electron-rich phenoxyether moiety. Notably, N-(4-formylphenyl)acetamide and 4-formylbenzoic acid were compatible with the method, although 14b resulted in lower yield due to troublesome purification. Finally, 2-phenylbenzaldehyde underwent concomitant thiomethylation and cyclization to afford the thiomethyl fluorene derivative 15b in 79% yield. Attempts to extend the method to aliphatic aldehydes and ketones were unfortunately unsuccessful.

Table 2. Scope of the Thioacetalation Reactiona.

Isolated yield.

From 4-bromobenzaldehyde.

From biphenyl-2-carboxaldehyde.

Intrigued by the cyclization of 2-biphenylaldehyde, and the apparent polymerization of 4-phenoxybenzaldehyde, we decided to investigate if the developed conditions could be utilized for cascade thiomethylation/arylation reactions. A literature survey revealed that, indeed, similar reactions have been described before.63,64 However, these methods proceed via the use of odorous ethanethiol, and to the best of our knowledge, the use of a thiomethyl source in this context is unprecedented.

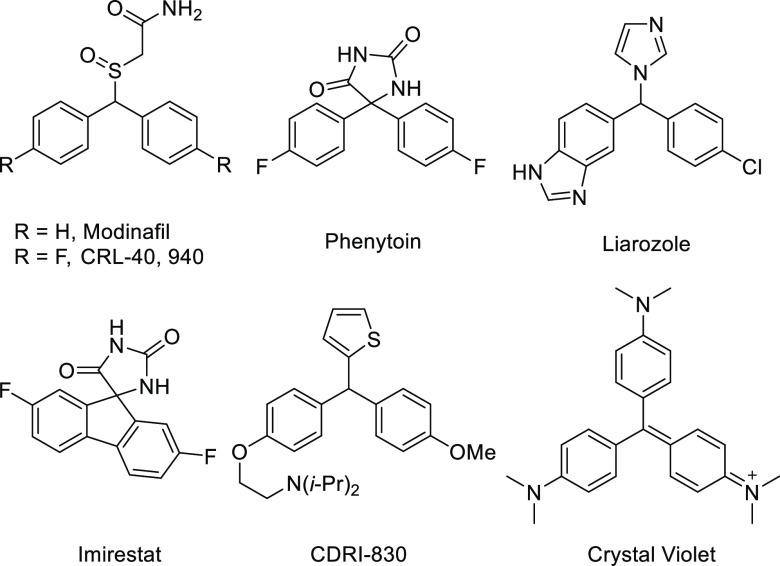

Arylmethanes are of considerable medicinal interest (Figure 1) and can for example be found in central nervous system stimulants modafinil and CRL-40,940,65,66 anti-seizure medication phenytoin,67 liarozole,68 a retinoic acid metabolism-blocking agent, the anti-diabetic imirestat,69 and CDRI-830, with anti-tubercular activity.70 The structures are also useful for the synthesis of dyes, here exemplified with crystal violet, a compound that is utilized for staining of bacteria,71 DNA,72 proteins,73 and also exhibits antibacterial properties.74

Figure 1.

Structures containing the arylmethane motif.

With the aim of developing a metal-free cascade thiomethylation/arylation sequence, we set out to explore the possibility of using BF3SMe2 as a dual-function Lewis acid and non-odorous sulfur source.

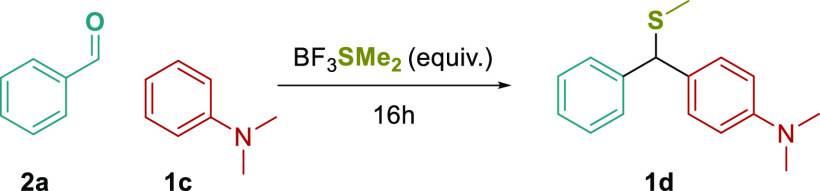

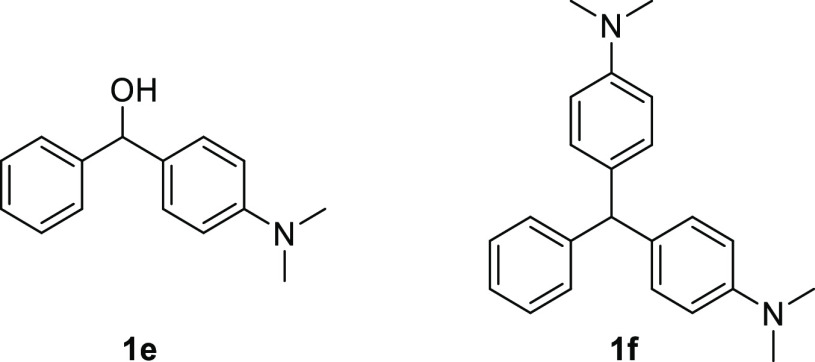

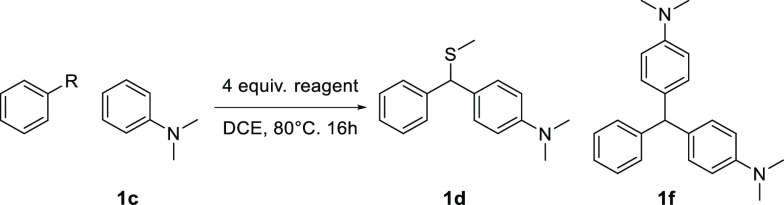

As a model substrate, N,N-dimethylaniline (1c) was chosen as the nucleophile, with benzaldehyde (2a) as the electrophile (Table 3). First, we explored the optimal amount of BF3SMe2 and, to our delight, 2 equivalents at 80 °C gave 79% of the desired product. Increasing the equivalents to 4 resulted in an improved 89% yield, while increasing it further was not beneficial and decreased the yield slightly (entries 1–3). We also found that increasing the amount of aniline or running the reaction in neat conditions gave no increase in yield (entries 4–5). Finally, reducing the reaction temperature to 60 °C resulted in a low yield of 1d (entry 6) along with alcohol 1e (27%) and triarylmethane 1f (22%) side products (Figure 2).

Table 3. Optimization of the Thiomethylative Friedel-Crafts Arylation Reactiona.

| entry | equiv | 1c (equiv) | solvent | temp. | yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1.1 | DCE | 80 °C | 79% |

| 2 | 4 | 1.1 | DCE | 80 °C | 89% |

| 3 | 6 | 1.1 | DCE | 80 °C | 86% |

| 4 | 4 | 1.3 | DCE | 80 °C | 87% |

| 5 | 4 | 1.1 | 80 °C | 86% | |

| 6 | 4 | 1.1 | DCM | 60 °C | 22% |

Reactions performed at 0.5 mmol scale.

Isolated yields.

Figure 2.

Observed side products during the optimization of the thiomethylative Friedel-Crafts arylation.

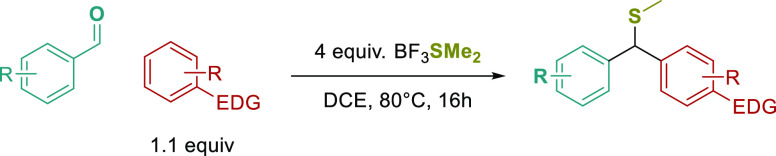

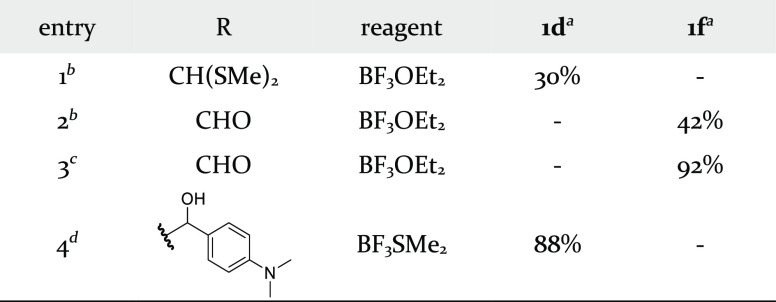

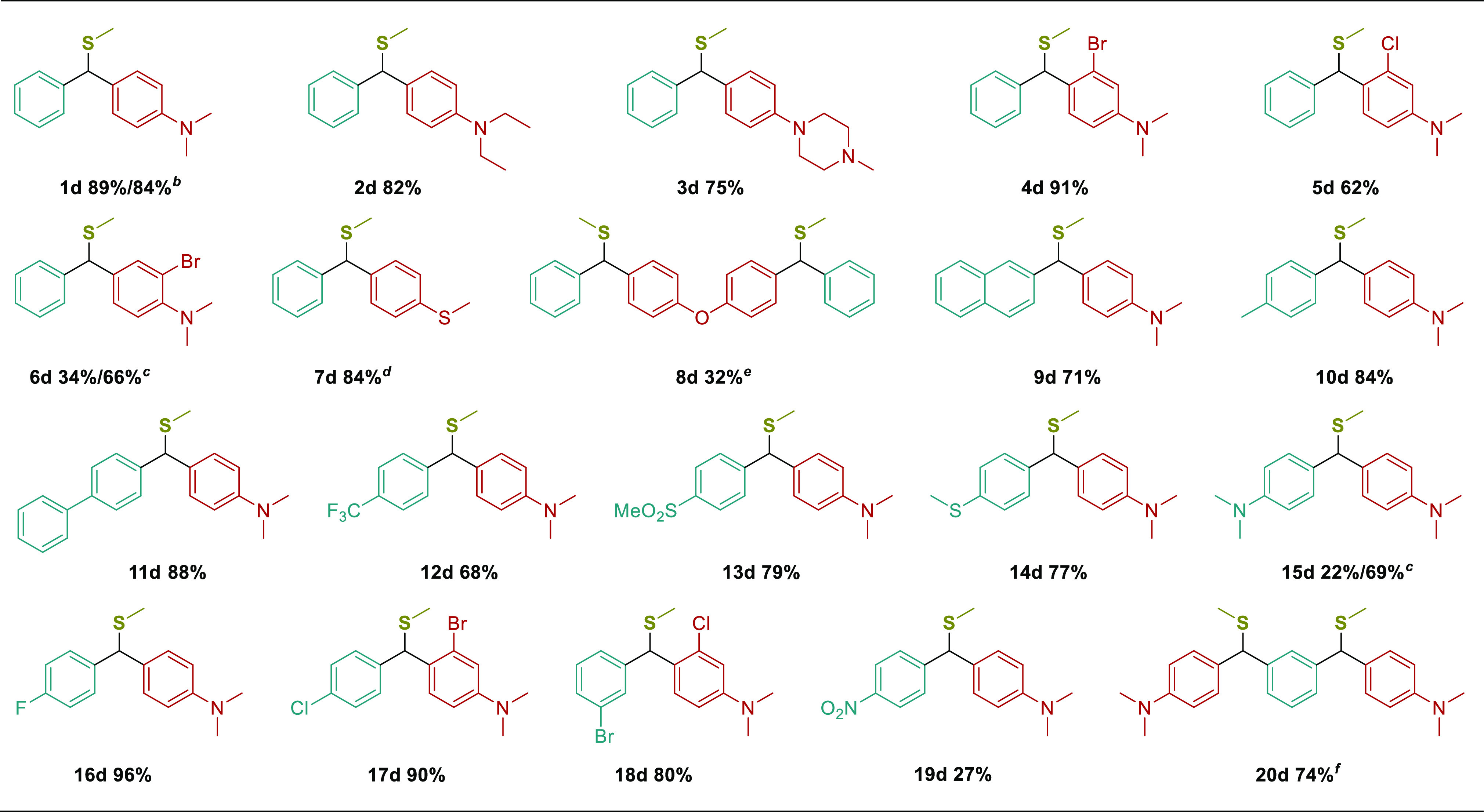

With suitable conditions in hand, we continued exploring the scope of the reaction (Table 4). The substituted anilines N,N-diethylaniline and N-methyl-4-phenylpiperazine reacted smoothly resulting in products 2d and 3d in good yield. Halogenated anilines were also well tolerated, affording products 4-6d in good to excellent yields. 2-Bromo-N,N-dimethylaniline was found to be less reactive, but this could be overcome by switching to solvent-free conditions. Methyl phenyl sulfide also reacted smoothly, although a longer 48 h reaction time was required to reach completion. The conditions were also compatible with diphenyl ether, which gave the bis-ether product 8d, in 32% yield. Our attempts to expand the scope to indoles revealed that these nucleophiles were too reactive and, instead of the target thiomethylated product, resulted in the exclusive formation of bis(indolyl)methanes. This was observed despite efforts to reduce reaction temperature and time.

Table 4. Scope of the Thiomethylative Friedel-Crafts Arylation Reactiona.

Isolated yield.

5 mmol reaction

Neat reaction.

48 h reaction.

0.5 mmol diphenyl ether, 2.2 equiv aldehyde, 8 equiv BF3SMe2, yield calculated with diphenyl ether as the limiting reagent.

2.2 equiv aniline and 8 equiv BF3SMe2.

Next, we turned our attention to exploring the aldehyde component and 2-napthaldehyde, 4-methylbenzaldehyde, and 4-phenylbenzaldehyde afforded the desired products 9-11d in good yields. Electron-withdrawing groups such as 4-(trifluoromethyl) and 4-(methylsulfonyl) were well tolerated, as were the electron donating 4-(methylthio) and 4-(dimethylamino) groups. In the case of 4-(dimethylamino)benzaldehyde, lower reactivity was observed, and again, neat conditions could be used to increase the yield. Halogen groups were also well tolerated as can be seen in the formation of compounds 16-18d. Finally, 1,3-dibenzaldehyde returned the bis-diarylmethane product 20d in good yield. The reaction was also scalable, where performing a 5 mmol reaction of benzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline resulted only in a slightly reduced yield of 1d (84%).

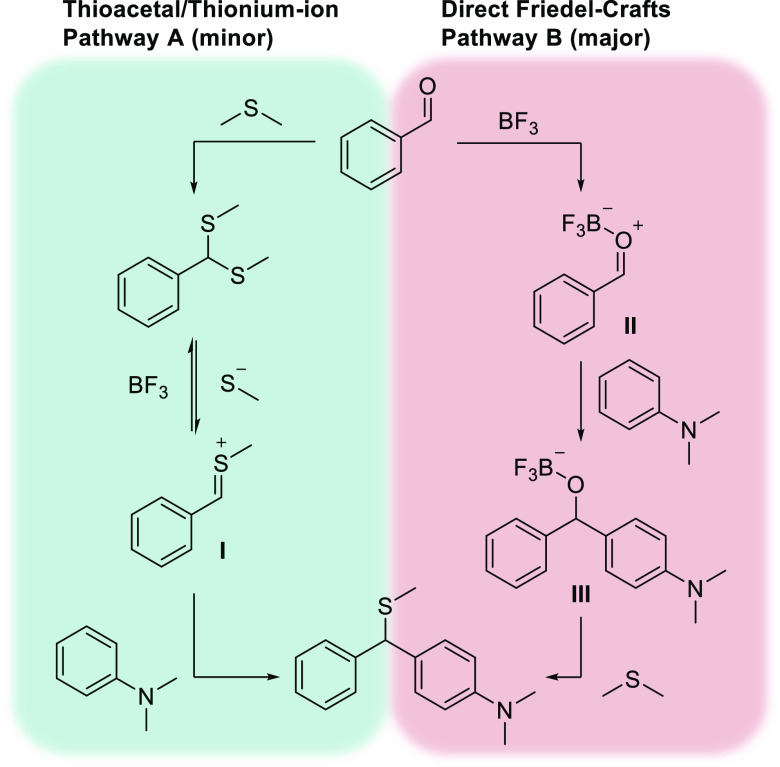

We then set out to clarify the reaction mechanism for the transformation, and two suggested pathways are presented in Scheme 2. In path A, the dithioacetal is formed first, followed by the formation of the thionium ion(I), and a final Friedel-Crafts type arylation leads to the product. In the second pathway (B), the order of events is reversed with an initial Lewis acid promoted Friedel-Crafts reaction followed by substitution of the activated alcohol(III) and a final demethylation, possibly by the eliminated oxygen75 or an additional SMe2,6 to afford the product.

Scheme 2. Proposed Pathways for the Thiomethylative Friedel-Crafts Arylation Reaction.

To determine which pathway was more plausible, a set of control reactions were performed (Table 5). First, we reacted dithioacetal 2b with dimethylaniline in the presence of 4 equiv of BF3OEt2 at 80 °C. This reaction was rather sluggish, and only 30% of the desired product was isolated (entry 1). We then went on to react benzaldehyde in the absence of a sulfur source, and this resulted in the triarylmethane product (1f) in 42% yield. When the amount of aniline was increased to 3 equivalents, the triarylmethane product was isolated in 92% yield (entries 2–3). Next, when using the putative alcohol intermediate 1e as a substrate, the desired product was isolated in 88% yield (entry 4). Taken together, these findings support the direct Friedel-Crafts pathway (Path B), where attack of aniline is favored over thioacetal formation and is most likely the first step in the reaction. The thioacetal pathway cannot be ruled out as the reaction still proceeds via this intermediate, albeit to a lesser extent.

Table 5. Mechanistic Investigation.

Isolated yield.

1.1 equiv 1c

3 equiv 1c

In the absence of 1c.

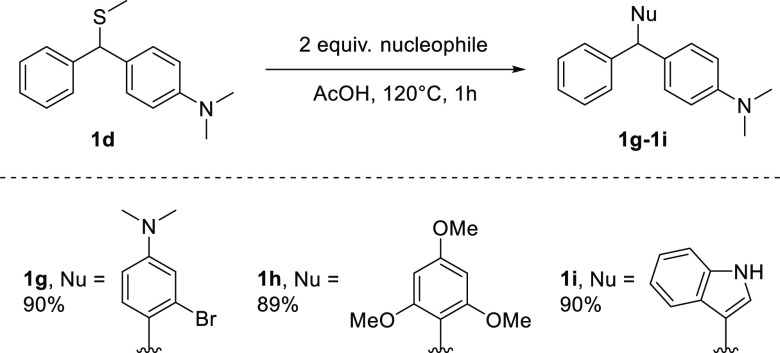

During our mechanistic investigations, we noted that displacement of the thiomethyl group occurred upon exposure of 1d to nucleophiles in certain conditions. We, therefore, reasoned that it could be utilized as a latent handle for further synthesis. After some experimentation, we found that the thiomethyl group was readily substituted under acidic conditions (Scheme 3) in the presence of arene nucleophiles. Thus, treatment of 1d with 2-bromo-N,N-dimethylaniline, 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene, or 1H-indole in AcOH afforded unsymmetrical triarylmethanes 1 g-1i in excellent yields. This represents a valuable new synthetic route to unsymmetrical triarylmethanes that are otherwise difficult to prepare using conventional Friedel-Crafts chemistry76−80 due to selectivity issues.

Scheme 3. Utility of the Thiomethylated Friedel-Crafts Compounds.

Conclusions

In summary, our efforts to explore BF3SMe2 as a versatile and underutilized reagent have resulted in the development of two new thiomethylation reactions. First, the synthesis of methyl dithioacetals from aldehydes has been demonstrated, avoiding odorous methanethiol and expanding the accessibility of this scarcely reported moiety. Furthermore, a three-component cascade thiomethylative Friedel-Crafts reaction was discovered using BF3SMe2 as a dual Lewis acid and thiomethyl source to afford interesting diarylmethane derivatives. Finally, the synthetic utility of these compounds was demonstrated through the strategic use of the thiomethyl moiety as a latent leaving group in the synthesis of challenging unsymmetrical triarylmethanes. The work described herein serves to further highlight the utility of BF3SMe2 as a convenient and multifaceted reagent/reactant with applications reaching beyond standard ether deprotections.

Experimental Section

General Information

Analytical thin-layer chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 F-254 plates and visualized with UV light. Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (40–63 μm). 1H and 13C spectra were recorded at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively. The chemical shifts for 1H NMR and 13C NMR are referenced to Tetramethylsilane via residual solvent signals (1H: CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm and DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm; 13C: CDCl3 at 77.16 ppm and DMSO-d6 at 39.52 ppm). Analytical high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization (ESI)-mass spectrometry was performed using ESI and a C18 column (50 × 3.0 mm2, 2.6 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size) with CH3CN/H2O in 0.05% aqueous HCOOH as mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. LC purity analyses were run using a gradient of 5–100% CH3CN/H2O in 0.05% aqueous HCOOH as mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min for 5 min unless otherwise stated on a C18 column. High-resolution molecular masses (HRMSs) were determined on a mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI source and time-of-flight unless otherwise stated.

General Procedure A for Synthesis of Compounds 1b–15b and 12ab

An oven-dried vial was charged with 0.5 mmol aldehyde. 1,2-Dichloroethane (DCE) (1 mL) was added, followed by 4 equiv (4 mmol, 0.42 mL) BF3SMe2. The vial was sealed, and the mixture was heated to 80 °C. After 16 h, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C and carefully quenched with 0.5 mL MeOH. The mixture was taken up in 20 mL DCM and poured into a separatory funnel. 10 mL Sat. Na2CO3 was added and the phases were separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with an additional 2 × 20 mL DCM. The organics were pooled, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude material was purified over silica.

General Procedure B for Synthesis of Compounds 1d–20d

A vial was charged with 0.5 mmol aldehyde and 1.1 equiv (0.55 mmol) nucleophile. DCE (1 mL) was added, followed by 4 equiv (2 mmol, 0.21 mL) BF3SMe2. The vial was sealed and the mixture was heated to 80 °C. After 16 h, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C and the reaction was quenched with 0.2 mL water. The mixture was poured into 10 mL sat. Na2CO3 and extracted with 3 × 20 mL DCM. The organics were pooled, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude material was purified over silica.

General Procedure C for Synthesis of Compounds 1g–1i

A vial was charged with 77.2 mg (0.3 mmol) 1d and 2 equiv (0.6 mmol) nucleophile. AcOH (1 mL) was added, and the mixture was heated to 120 °C for 1 h with the vial open to the atmosphere. The mixture was cooled to ambient temperature and poured into 10 mL sat. Na2CO3 and extracted with 3 × 20 mL DCM. The organics were pooled, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude material was purified over silica.

(Naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)bis(methylsulfane) (1b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 2-napthaldehyde. Purified over silica using 20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (79.9 mg, 68%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.87–7.79 (m, 4H), 7.59 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.43 (m, 2H), 4.94 (d, J = 0.5 Hz, 1H), 2.13 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.0, 133.2, 133.1, 128.7, 128.1, 127.8, 126.5, 126.4, 126.3, 125.9, 56.8, 15.2. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C12H11S+ 187,0477; found 187.0575.

(Phenylmethylene)bis(methylsulfane) (2b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from benzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 2% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a colorless oil (51.0 mg, 55%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.44–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.24 (m, 1H), 4.79 (s, 1H), 2.11 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.8, 128.6, 128.0, 127.7, 56.6, 15.1.57

([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylmethylene)bis(methylsulfane) (3b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from biphenyl-4-carboxaldehyde. Purified over silica using 20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (90.7 mg, 70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.62–7.55 (m, 4H), 7.52–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.32 (m, 1H), 4.84 (s, 1H), 2.15 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 140.9, 140.7, 138.8, 128.9, 128.2, 127.5, 127.4, 127.2, 56.4, 15.1. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C14H13S+ 213.0738; found 213.0732.

((4-Chlorophenyl)methylene)bis(methylsulfane) (4b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-chlorobenzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a pale yellow oil (80.6 mg, 73%).811H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.29 (m, 2H), 4.75 (s, 1H), 2.09 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.4, 133.6, 129.1, 128.8, 55.9, 15.1.

((4-Fluorophenyl)methylene)bis(methylsulfane) (5b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-fluorobenzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a clear oil (72.8 mg, 72%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.44–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.07–6.98 (m, 2H), 4.77 (s, 1H), 2.10 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.3 (d, J = 246.8 Hz), 135.7 (d, J = 3.2 Hz), 129.4 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 115.5 (d, J = 21.8 Hz), 55.8, 15.1.55

((4-(Methylthio)phenyl)methylene)bis(methylsulfane) (6b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from either 4-bromobenzaldehyde or 4-(methylthio)benzaldehyde. From 4-bromobenzaldehyde: Purified over silica using 20–50% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a pale yellow oil (23.0 mg, 20%). From 4-(methylthio)benzaldehyde: Purified over silica using 20–50% DCM in i-hexane. 43.5 mg (38%) isolated as a pale yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.36–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.19 (m, 2H), 4.75 (s, 1H), 2.48 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.2, 136.6, 128.2, 126.6, 56.1, 15.8, 15.1. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C9H11S2+ 183.0302; found 183.0297.

((3-Bromophenyl)methylene)bis(methylsulfane) (7b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 3-bromobenzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (93.0 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (t, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.9, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.72 (s, 1H), 2.11 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 142.2, 131.1, 130.8, 130.2, 126.4, 122.7, 55.9, 15.1. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C8H8BrS+ 214.9525; found 214.9532.

3-(Bis(Methylthio)methyl)quinolone (8b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 3-quinolinecarboxaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10–20% EtOAc in toluene. Isolated as a clear oil (100.3 mg, 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.96 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.13–8.06 (m, 1H), 7.82 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 4.99 (s, 1H), 2.14 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.8, 147.7, 133.9, 132.6, 129.7, 129.4, 128.0, 127.5, 127.2, 54.1, 14.9.22

2-(Bis(methylthio)methyl)pyridine (9b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10–25% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a pale yellow oil (65.6 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.53 (dt, J = 4.9, 1.8, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (td, J = 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (ddd, J = 7.5, 4.9, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 4.92 (s, 1H), 2.13 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.4, 149.0, 137.0, 122.6, 122.0, 58.3, 14.5.54

4-(Bis(methylthio)methyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (10b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-(dimethylamino)benzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 50% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a pale yellow oil (69.8 mg, 61%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.33–7.25 (m, 2H), 6.73–6.64 (m, 2H), 4.75 (s, 1H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.09 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.3, 128.6, 127.2, 112.3, 56.3, 40.7, 15.2.

HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C11H18NS2 228.0881; found 228.0880.

((4-Phenoxyphenyl)methylene)bis(methylsulfane) (11b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-phenoxybenzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as an off-white solid (28.8 mg, 21%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.41–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.15–7.09 (m, 1H), 7.05–7.00 (m, 2H), 6.99–6.94 (m, 2H), 4.78 (s, 1H), 2.12 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.1, 157.0, 134.5, 129.9, 129.1, 123.6, 119.3, 118.7, 56.1, 15.2. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C14H13OS+ 229.0687; found 229.0681.

((4-(p-Tolyloxy)phenyl)methylene)bis(methylsulfane) (12b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-(4-methylphenoxy)benzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as an off-white solid (60.0 mg, 41%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.40–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.11 (m, 2H), 6.97–6.89 (m, 4H), 4.77 (s, 1H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.6, 154.5, 134.0, 133.3, 130.4, 129.0, 119.5, 118.1, 56.1, 20.9, 15.2. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C15H15OS+ 243.0844; found 243.0837.

N-(4-(Bis(methylthio)methyl)phenyl)acetamide (13b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-acetamidobenzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 25–75% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as an off-white solid (89.0 mg, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.97 (s, 1H), 7.58–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.26 (m, 2H), 4.99 (s, 1H), 2.04 (s, 6H), 2.03 (s, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.3, 138.7, 134.4, 127.7, 118.8, 54.8, 24.0, 14.5, 14.3. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C11H16NOS2 242.0673; found 242.0684.

4-(Bis(methylthio)methyl)benzoic Acid (14b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-formylbenzoic acid. Purified over silica using 10–50% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (18.6 mg, 16%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.57–7.48 (m, 2H), 4.83 (s, 1H), 2.12 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.6, 146.0, 130.7, 128.9, 127.9, 56.2, 15.0. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C9H9O2S+ 181.0323; found 181.0331.

(9H-Fluoren-9-yl)(methyl)sulfane (15b)

Synthesized according to procedure A from biphenyl-2-carboxaldehyde. Purified over silica using 20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (84.0 mg, 79%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77–7.65 (m, 4H), 7.45–7.32 (m, 4H), 4.88 (s, 1H), 1.41 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.4, 141.0, 128.0, 127.7, 125.4, 119.8, 49.0, 9.7.82

Dimethyl(4-(p-tolyloxy)benzyl)sulfonium (12ba)

Synthesized according to procedure A from 4-(4-methylphenoxy)benzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10% MeOH in DCM. Isolated as an off-white solid (42.5 mg, 25%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.40–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.11 (m, 2H), 6.98–6.86 (m, 4H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 2.82 (s, 6H), 2.34 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.1, 153.3, 134.3, 132.6, 130.7, 120.1, 120.0, 118.6, 46.6, 23.6, 20.9. HRMS m/z: [M]+ calcd for C16H19OS+ 259.1157; found 259.1157.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)aniline (1d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from benzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (114.0 mg, 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.47–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.25 (m, 4H), 7.25–7.18 (m, 1H), 6.73–6.65 (m, 2H), 5.02 (s, 1H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 1.98 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.8, 142.1, 129.1, 129.0, 128.5, 128.4, 127.0, 112.6, 55.7, 40.7, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H20NS 258.1316; found 258.1311.

N,N-Diethyl-4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)aniline (2d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from benzaldehyde and N,N-diethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a brown liquid (117.3 mg, 82%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.29–7.20 (m, 3H), 6.74–6.50 (m, 2H), 5.01 (s, 1H), 3.34 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 1.16 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 147.0, 142.1, 129.3, 128.5, 128.4, 127.7, 126.9, 111.7, 55.7, 44.4, 16.0, 12.7. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H24NS 286.1629; found 286.1628.

1-Methyl-4-(4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)phenyl)piperazine (3d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from benzaldehyde and 1-methyl-4-phenylpiperazine. Purified over silica using 2% MeOH and 1% TEA in DCM. Isolated as a brown oil (116.8 mg, 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.25–7.18 (m, 1H), 6.91–6.83 (m, 2H), 5.01 (s, 1H), 3.25–3.15 (m, 4H), 2.62–2.52 (m, 4H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 1.97 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.2, 141.7, 132.2, 129.1, 128.5, 128.3, 127.0, 115.9, 55.5, 55.1, 48.9, 46.2, 15.9. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C19H25N2S [M + H]+ 313.1738; found 313.1739.

3-Bromo-N,N-dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)aniline (4d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from benzaldehyde and 3-bromo-N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (152.9 mg, 91%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.48 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.17 (m, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.52 (s, 1H), 2.92 (s, 6H), 2.01 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.4, 141.2, 130.3, 128.5, 128.5, 127.4, 127.1, 125.6, 115.9, 112.1, 53.9, 40.5, 16.1. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H19BrNS 336.0422; found 336.0413.

3-Chloro-N,N-dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)aniline (5d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from benzaldehyde and 3-chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a yellow oil (90.3 mg, 62%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (s, 1H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.03 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.2, 141.2, 134.6, 130.1, 128.5, 128.4, 127.0, 125.8, 112.7, 111.5, 51.3, 40.4, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H19ClNS 292.0927; found 292.0922.

2-Bromo-N,N-dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)aniline (6d)

Synthesized according to modified procedure B from benzaldehyde and 2-bromo-N,N-dimethylaniline in neat conditions. Purified over silica using 25–50% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a yellow oil (110.7 mg, 66%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (dd, J = 2.1, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.28–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.96 (s, 1H), 2.78 (s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.9, 141.0, 137.1, 133.7, 128.8, 128.3, 128.0, 127.4, 120.5, 119.2, 55.2, 44.3, 16.1. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H19BrNS 336.0422; found 336.0427.

Methyl(4-((methylthio)(phenyl)methyl)phenyl)sulfane (7d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from benzaldehyde and thioanisole. 48 h reaction time. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a yellow oil (108.7 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.48–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.29 (m, 4H), 7.28–7.19 (m, 3H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 2.47 (s, 3H), 2.00 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.2, 138.3, 137.3, 128.9, 128.7, 128.4, 127.3, 126.8, 55.8, 16.0, 16.0. HRMS (EI+) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C15H16S2 260.0688; found 260.0693.

((Oxybis(4,1-phenylene))bis(phenylmethylene))bis(methylsulfane) (8d)

Synthesized according to a modified procedure B from 0.5 mmol diphenylether and 1.1 mmol (2.2 equiv) benzaldehyde. Purified over silica using 10–20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a clear oil (70.5 mg, 32%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.46–7.40 (m, 4H), 7.39–7.30 (m, 8H), 7.28–7.22 (m, 2H), 6.99–6.90 (m, 4H), 5.05 (s, 2H), 2.00 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 156.3, 141.3, 136.3, 129.7, 128.7, 128.4, 127.3, 118.9, 55.6, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M – –SMe]+ calcd for C27H23OS+ 395.1470; found 395.1471.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(naphthalen-2-yl)methyl)aniline (9d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 2-naphtaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (109.0 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.93–7.88 (m, 1H), 7.88–7.79 (m, 3H), 7.61 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.30 (m, 2H), 6.80–6.68 (m, 2H), 5.21 (s, 1H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.05 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.8, 139.4, 133.4, 132.7, 129.2, 128.8, 128.3, 128.0, 127.7, 126.8, 126.1, 112.6, 55.8, 40.6, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C20H22NS 308.1473; found 308.1479.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(p-tolyl)methyl)aniline (10d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from p-tolualdehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as yellow oil (113.7 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.10 (m, 2H), 6.77–6.67 (m, 2H), 5.02 (s, 1H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.7, 139.0, 136.5, 129.3, 129.2, 129.1, 128.2, 112.6, 55.3, 40.7, 21.1, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H22NS 272.1473; found 272.1461.

4-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-yl(methylthio)methyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (11d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from biphenyl-4-caroxaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a brown solid (147.2 mg, 88%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.64–7.52 (m, 6H), 7.48–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.32 (m, 3H), 6.76–6.72 (m, 2H), 5.09 (s, 1H), 2.96 (s, 6H), 2.05 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.8, 141.2, 141.0, 139.8, 129.1, 128.9, 128.8, 128.8, 127.3, 127.1, 112.6, 55.4, 40.7, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C22H24NS 334.1629; found 334.1627.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)methyl)aniline (12d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a red oil (111.0 mg, 68%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.62–7.49 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.20 (m, 2H), 6.74–6.62 (m, 2H), 5.04 (s, 1H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.0, 146.3, 129.9-129.0 (q, J = 32.3 Hz), 129.1, 128.7, 127.9, 125.6–125.5 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 123.0, 123.0, 112.6, 55.3, 40.6, 16.0. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −62.4. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H19F3NS 326.1190; found 326.1189.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl)(methylthio)methyl)aniline (13d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 4-(methylsulfonyl)benzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 20% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a green oil (132.4 mg, 79%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.87 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.68 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 3.02 (s, 3H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 1.98 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.9, 148.7, 138.9, 129.3, 129.0, 127.7, 127.2, 112.5, 55.2, 44.6, 40.5, 15.9. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H22NO2S2 336.1092; found 336.1082.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(4-(methylthio)phenyl)methyl)aniline (14d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 4-(methylthio)benzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 2–5% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a yellow oil (117.0 mg, 77%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39–7.30 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.17 (m, 2H), 6.73–6.64 (m, 2H), 4.98 (s, 1H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 1.98 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.8, 139.1, 136.8, 129.1, 128.9, 128.8, 126.9, 112.6, 55.2, 40.7, 16.1, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C17H22NS2 304.1194; found 304.1201.

4,4′-((Methylthio)methylene)bis(N,N-dimethylaniline) (15d)

Synthesized according to modified procedure B from 4-(dimethylamino)benzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline in neat conditions. Purified over silica using 5–10% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as an off-white solid (103.9 mg, 69%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32–7.24 (m, 4H), 6.72–6.65 (m, 4H), 4.96 (s, 1H), 2.92 (s, 12H), 1.97 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.7, 129.9, 129.1, 112.7, 55.1, 40.8, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H25N2S 301.1733; found 301.1734.

4-((4-Fluorophenyl)(methylthio)methyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (16d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 4-fluorobenzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5% EtOAc in i-Hexane. Isolated as a white solid (132.4 mg, 96%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.05–6.98 (m, 2H), 6.74–6.68 (m, 2H), 5.01 (s, 1H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.8 (d, J = 245.3 Hz), 149.8, 137.9 (d, J = 3.1 Hz), 129.9 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 129.0, 128.7, 115.3 (d, J = 21.4 Hz), 112.6, 54.9, 40.6, 16.0. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −115.9, −116.0 (m). HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H19FNS 276.1222; found 276.1212.

3-Bromo-4-((4-chlorophenyl)(methylthio)methyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (17d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 4-chlorobenzaldehyde and 3-bromo-N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 10–20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a clear oil (167.3 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.22 (m, 2H), 6.86 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (s, 1H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.01 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.5, 139.8, 132.8, 130.1, 129.8, 128.7, 126.7, 125.6, 115.9, 112.1, 53.3, 40.4, 16.1. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H18BrClNS [M + H]+ 370.0032; found 370.0038.

4-((3-Bromophenyl)(methylthio)methyl)-3-chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline (18d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 3-bromobenzaldehyde and 3-chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 10–20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as a clear oil (148.7 mg, 80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60–7.54 (m, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.30 (m, 2H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (s, 1H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.02 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.4, 143.6, 134.6, 131.4, 130.2, 130.1, 130.0, 127.2, 124.9, 122.6, 112.7, 111.5, 50.9, 40.4, 16.1. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H18BrClNS 370.0032; found 370.0026.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-((methylthio)(4-nitrophenyl)methyl)aniline (19d)

Synthesized according to procedure B from 4-nitrobenzaldehyde and N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 20% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as an orange solid (40.9 mg, 27%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.16 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.68 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.06 (s, 1H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 1.99 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.1, 149.8, 146.9, 129.2, 129.1, 127.1, 123.9, 112.6, 55.2, 40.6, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H19N2O2S 303.1167; found 303.1162.

4,4′-(1,3-Phenylenebis((methylthio)methylene))bis(N,N-dimethylaniline) (20d)

Synthesized according to modified procedure B from 0.5 mmol isophtalaldehyde and 1.1 mmol (2.2 equiv) N,N-dimethylaniline. Purified over silica using 5–20% DCM in i-hexane. Isolated as an off-white solid (160.5 mg, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56 (td, J = 1.8, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.22 (m, 7H), 6.71–6.65 (m, 4H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 2.93 (s, 12H), 1.96 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.7, 142.0, 142.0, 129.2, 129.1, 129.0, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 127.0, 112.6, 55.6, 40.7, 16.0. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C26H33N2S2 [M + H]+ 437.2085; found 437.2071.

4,4′-(Phenylmethylene)bis(N,N-dimethylaniline) (1f)

A vial was charged with 51.3 mg (0.5 mmol) benzaldehyde and 3 equiv (1.5 mmol, 185 mg) N,N-dimethylaniline. DCE (1 mL) was added, followed by 4 equiv (2 mmol, 0.21 mL) BF3OEt2. The vial was sealed, and the mixture was heated to 80 °C. After 16 h, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and 0.2 mL water was added. The mixture was poured into 10 mL Sat. Na2CO3 and extracted with 3 × 20 mL DCM. The organics were pooled, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude material was purified over silica using 5–10% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a brown oil (165.0 mg, 92%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.04–6.95 (m, 4H), 6.73–6.63 (m, 4H), 5.39 (s, 1H), 2.92 (s, 12H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.1, 145.6, 133.0, 130.1, 129.5, 128.2, 125.9, 112.7, 55.1, 40.9.83

3-Bromo-4-((4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)(phenyl)methyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (1g)

Synthesized according to procedure C with 3-bromo-N,N-dimethylaniline as a nucleophile. Purified over silica using 5–10% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a white solid (110.1 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.06 (m, 2H), 6.99–6.90 (m, 3H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.71–6.63 (m, 2H), 6.57 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (s, 1H), 2.92 (s, 6H), 2.91 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.0, 149.1, 144.4, 131.7, 131.5, 131.4, 130.2, 129.6, 128.2, 126.3, 126.0, 116.5, 112.6, 111.6, 54.2, 40.8, 40.6. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C23H26BrN2 409.1279; found 409.1284.

N,N-Dimethyl-4-(phenyl(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)methyl)aniline (1h)

Synthesized according to procedure C with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as nucleophile. Purified over silica using 5–10% EtOAc in i-hexane. Isolated as a pink oil (101.0 mg, 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34–7.15 (m, 7H), 6.85–6.78 (m, 2H), 6.23 (s, 2H), 6.07 (s, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.67 (s, 6H), 3.00 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.9, 159.2, 145.2, 130.1, 129.0, 127.5, 125.1, 114.2, 113.0, 91.8, 55.8, 55.3, 44.3, 41.4. HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C24H28NO3 378.2069; found 378.2063.

4-((1H-Indol-3-yl)(phenyl)methyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (1i)

Synthesized according to procedure C with 1H-indole as nucleophile. Purified over silica using 2% EtOAc in toluene. Isolated as a white solid (88.0 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.34 (dt, J = 8.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.17 (m, 6H), 7.19–7.13 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.08 (m, 2H), 6.99 (ddd, J = 8.0, 7.1, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.64 (m, 2H), 6.59 (dd, J = 2.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.59 (s, 1H), 2.92 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.2, 144.9, 136.9, 132.3, 129.7, 129.1, 128.3, 127.3, 126.1, 124.1, 122.1, 120.8, 120.2, 119.4, 112.7, 111.1, 48.0, 40.9.77

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lisa Haigh (Imperial College London, U.K.) for assistance with accurate mass determination. The research was supported by Uppsala University and the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet 2018-05133).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c07608.

NMR spectra (1H NMR and 13C NMR) of all compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aparicio D. M.; Tépox-Luna D.; Bedolla-Medrano M.; Gnecco D.; Juárez J. R.; Mendoza Á.; Orea M. L.; Terán J. L. Boron Trifluoride Etherate for Regioselective Rearrangement or Opening of Secondary Aryl Glycidic Amides. Tetrahedron 2022, 122, 132934 10.1016/j.tet.2022.132934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H.; Yao J.; Zhang M.; Xue L.; Zhou Q.; Li S.; Lei M.; Meng L.; Zhang Z.; Li Y. Low-Cost Synthesis of Small Molecule Acceptors Makes Polymer Solar Cells Commercially Viable. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3687. 10.1038/s41467-022-31389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z.-Y.; He Y.; Li L.-Y.; Tian J.-S.; Loh T.-P. BF 3 -Promoted Reactions of α-Amino Acetals with Alkynes to 2,5-Disubstituted Pyrroles. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 3317–3321. 10.1039/D2QO00405D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goulart T. A. C.; Recchi A. M. S.; Back D. F.; Zeni G. Selective 5-Exo-Dig versus 6-Endo-Dig Cyclization of Benzoimidazole Thiols with Propargyl Alcohols. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 1989–1997. 10.1002/adsc.202200254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthusamy S.; Prabu A. BF3·OEt2 catalyzed Chemoselective CC Bond Cleavage of α,β-Enones: An Unexpected Synthesis of 3-Alkylated Oxindoles and Spiro-Indolooxiranes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 558–564. 10.1039/D1OB02002A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuji K.; Kawabata T.; Fujita E. Hard Acid and Soft Nucleophile System. IV. Removal of Benzyl Protecting Group with Boron Trifluoride Etherate and Dimethyl Sulflide. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1980, 28, 3662–3664. 10.1248/cpb.28.3662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers M. J.; Carlson K. E.; Katzenellenbogen J. A. Facile Synthesis of High Affinity Styrylpyridine Systems as Inherently Fluorescent Ligands for the Estrogen Receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 3589–3594. 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny M. T.; Horowska B.; Kunikowski A.; Konopa J.; Wierzba K.; Yamada Y.; Asao T. Synthesis of Polyhydroxylated Derivatives of Phenyl Vinyl Sulfone as Structural Analogs of Chalcones. Synthesis 2001, 1363–1367. 10.1055/s-2001-15223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abu Rabah R. R.; Sebastian A.; Vunnam S.; Sultan S.; Tarazi H.; Anbar H. S.; Shehata M. K.; Zaraei S.-O.; Elgendy S. M.; Al Shamma S. A.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of a New Series of Pyrazole Derivatives: Discovery of Potent and Selective JNK3 Kinase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 69, 116894 10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaib S.; Tayyab Younas M.; Zaraei S. O.; Khan I.; Anbar H. S.; El-Gamal M. I. Discovery of Urease Inhibitory Effect of Sulfamate Derivatives: Biological and Computational Studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 119, 105545 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koufaki M.; Tsatsaroni A.; Alexi X.; Guerrand H.; Zerva S.; Alexis M. N. Isoxazole Substituted Chromans against Oxidative Stress-Induced Neuronal Damage. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 4841–4850. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchais-Oberwinkler S.; Xu K.; Wetzel M.; Perspicace E.; Negri M.; Meyer A.; Odermatt A.; Möller G.; Adamski J.; Hartmann R. W. Structural Optimization of 2,5-Thiophene Amides as Highly Potent and Selective 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Osteoporosis. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 167–181. 10.1021/jm3014053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y.; Okada Y.; Chiba K. Understanding the Reactivity of Enol Ether Radical Cations: Investigation of Anodic Four-Membered Carbon Ring Formation. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 2626–2638. 10.1021/jo3028246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong R.; Zhao J.; Gutgesell L. M.; Wang Y.; Lee S.; Karumudi B.; Zhao H.; Lu Y.; Tonetti D. A.; Thatcher G. R. J. Novel Selective Estrogen Receptor Downregulators (SERDs) Developed against Treatment-Resistant Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1325–1342. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian M.; Vasudevan L.; Huysentruyt J.; Risseeuw M. D. P.; Stove C.; Vanderheyden P. M. L.; Van Craenenbroeck K.; Van Calenbergh S. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Bivalent Ligands Targeting Dopamine D 2 -Like Receptors and the μ-Opioid Receptor. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 944–956. 10.1002/cmdc.201700787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ahmad Y.; Tabart M.; Halley F.; Certal V.; Thompson F.; Filoche-Rommé B.; Gruss-Leleu F.; Muller C.; Brollo M.; Fabien L.; et al. Discovery of 6-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-5-[4-[(3 S)-1-(3-Fluoropropyl)Pyrrolidin-3-Yl]Oxyphenyl]-8,9-Dihydro-7 H-Benzo[7]Annulene-2-Carboxylic Acid (SAR439859), a Potent and Selective Estrogen Receptor Degrader (SERD) for the Treatment of Estrogen-Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 512–528. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L.; Schafer A.; Li Y.; Cheng H.; Medegan Fagla B.; Shen Z.; Nowar R.; Dye K.; Anantpadma M.; Davey R. A.; et al. Screening and Reverse-Engineering of Estrogen Receptor Ligands as Potent Pan-Filovirus Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 11085–11099. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gamal M. I.; Zaraei S. O.; Foster P. A.; Anbar H. S.; El-Gamal R.; El-Awady R.; Potter B. V. L. A New Series of Aryl Sulfamate Derivatives: Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115406 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M.; Pagenkopf B. L. The Regioselective Mono-Deprotection of 1,3-Dioxa-2,2-(Di-Tert-Butyl)-2-Silacyclohexanes with BF3,SMe2. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 4553–4558. 10.1021/jo025624x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny M. T.; Maciejewski G.; Konieczny W. Selectivity Adjustment in the Cleavage of Allyl Phenyl and Methyl Phenyl Ethers with Boron Trifluoride-Methyl Sulfide Complex. Synthesis 2005, 17, 1575–1577. 10.1055/s-2005-865304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iashin V.; Berta D.; Chernichenko K.; Nieger M.; Moslova K.; Pápai I.; Repo T. Metal-Free C–H Borylation of N-Heteroarenes by Boron Trifluoride. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 13873–13879. 10.1002/chem.202001436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderström M.; Zamaratski E.; Odell L. R. BF3 ·SMe 2 for Thiomethylation Nitro Reduction and Tandem Reduction/SMe Insertion of Nitrogen Heterocycles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 31–32, 5402–5408. 10.1002/ejoc.201900503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt T. E. Developments in the Deprotection of Thioacetals. J. Sulfur Chem. 2005, 26, 411–427. 10.1080/17415990500195198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J.; Seebach D. Synthesis of 1,n-Dicarbonyl Derivates Using Carbanions from 1,3-Dithianes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1965, 4, 1077–1078. 10.1002/anie.196510771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seebach D.; Corey E. J. Generation and Synthetic Applications of 2-Lithio-1,3-Dithianes. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 231–237. 10.1021/jo00890a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann H. Some Steroid Mercaptols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 562–566. 10.1021/ja01195a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieser L. F. Preparation of Ethylenethioketals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 1945–1947. 10.1021/ja01636a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong B. S. A Simple and Efficient Method of Thioacetal - and Ketalization. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 4225–4228. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92868-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V.; Dev S. Titanium Tetrachloride, an Efficient and Convenient Reagent for Thioacetalization1,1. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 1289–1292. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)81637-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuji K.; Kawabata T.; Node M.; Fujita E. Carbon-Carbon Double Bond Cleavage with a Hard Lewis Acid and Ethanethiol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 875–878. 10.1016/0040-4039(81)80019-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firouzabadi H.; Iranpoor N.; Hazarkhani H. Iodine Catalyzes Efficient and Chemoselective Thioacetalization of Carbonyl Functions, Transthioacetalization of O, O- and S, O-Acetals and Acylals. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 7527–7529. 10.1021/jo015798z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firouzabadi H.; Iranpoor N.; Amani K. Heteropoly Acids as Heterogeneous Catalysts for Thioacetalization and Transthioacetalization Reactions. Synthesis 2002, 59–60. 10.1055/s-2002-19300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt M. J.; Sneddon H. F.; Hewitt P. R.; Orsini P.; Hook D. F.; Ley S. V. Development of β-Keto 1,3-Dithianes as Versatile Intermediates for Organic Synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 15–16. 10.1039/B208982C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini V.; Lucchesini F.; Pocci M.; De Munno A. Polymeric Reagents with Propane-1,3-Dithiol Functions and Their Precursors for Supported Organic Syntheses. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4839–4842. 10.1021/jo000078y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung N.; Grässle S.; Lütjohann D. S.; Bräse S. Solid-Supported Odorless Reagents for the Dithioacetalization of Aldehydes and Ketones. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 1036–1039. 10.1021/ol403313h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.; Liu Q.; Yin Y.; Fang Q.; Zhang J.; Dong D. α,α-Diacetyl Cyclic Ketene Dithioacetals: Odorless and Efficient Dithiol Equivalents in Thioacetalization Reactions. Synlett 2004, 6, 999–1002. 10.1055/s-2004-822892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D.; Ouyang Y.; Yu H.; Liu Q.; Liu J.; Wang M.; Zhu J. Chemoselective Thioacetalization in Water: 3-(1,3-Dithian-2-Ylidene)Pentane- 2,4-Dione as an Odorless, Efficient, and Practical Thioacetalization Reagent. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 4535–4537. 10.1021/jo050271y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y.; Dong D.; Zheng C.; Yu H.; Liu Q.; Fu Z. Chemoselective Thioacetalization Using 3-(1,3-Dithian-2-Ylidene)Pentane-2, 4-Dione as an Odorless and Efficient Propane-1,3-Dithiol Equivalent under Solvent-Free Conditions. Synthesis 2006, 1, 3801–3804. 10.1055/s-2006-950298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Che G.; Yu H.; Liu Y.; Zhang J.; Zhang Q.; Dong D. The First Nonthiolic, Odorless 1,3-Propanedithiol Equivalent and Its Application in Thioacetalization. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 9148–9150. 10.1021/jo034702t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.; Dong D.; Ouyang Y.; Liu Q. Chemoselective Thioacetalization with Odorless 2-(1,3-Dithian-2-Ylidene)-3- Oxobutanoic Acid as a 1,3-Propanedithiol Equivalent. Can. J. Chem. 2005, 83, 1741–1745. 10.1139/v05-184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D.; Yu H.; Ouyang Y.; Liu Q.; Bi X.; Lu Y. Thia-Michael Addition Reactions Using 2-[Bis(Alkylthio)Methylene]-3-Oxo-N- o-Tolylbutanamides as Odorless and Efficient Thiol Equivalents. Synlett 2006, 283–287. 10.1055/s-2005-923602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tani H.; Masumoto K.; Inamasu T.; Suzuki H. Tellurium Tetrachloride as a Mild and Efficient Catalyst for Dithioacetalization. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 2039–2042. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)78902-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceschi M. A.; de Araujo Felix L.; Peppe C. Indium Tribromide-Catalyzed Chemoselective Dithioacetalization of Aldehydes in Non-Aqueous and Aqueous Media. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 9695–9699. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01741-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iranpoor N.; Firouzabadi H.; Shaterian H. R.; Zolfigol M. A. 2,4,4,6-Tetrabromo-2,5-Cyclohexadienone (TABCO), N-Bromosuccinimide (NBS) and Bromine as Efficient Catalysts for Dithioacetalization and Oxathioacetalization of Carbonyl Compounds and Transdithioacetalization Reactions. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2002, 177, 1047–1071. 10.1080/10426500211712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanta De S. Cobalt(II)Chloride Catalyzed Chemoselective Thioacetalization of Aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 1035–1036. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.11.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanta De S. Ruthenium(III) Chloride-Catalyzed Thioacetalization of Carbonyl Compounds: Scope, Selectivity, and Limitations. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005, 347, 673–676. 10.1002/adsc.200404323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasulu M.; Rajesh K.; Suryakiran N.; Jon Paul Selvam J.; Venkateswarlu Y. Lanthanum(III) Nitrate Hexahydrate Catalyzed Chemoselective Thioacetalization of Aldehydes. J. Sulfur Chem. 2007, 28, 245–249. 10.1080/17415990701344710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazarkhani H. Trichloromelamine (TCM) – Catalyzed Efficient and Selective Thioacetalization of Aldehydes and Transthioacetalization of Acetals and Oxathioacetals under Mild Reaction Conditions. Synth. Commun. 2008, 38, 2597–2606. 10.1080/00397910802219338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami S.; Maity A. C. Molybdenum Pentachloride (MoCl5) or Molybdenum Dichloride Dioxide (MoO2Cl2): Advanced Catalysts for Thioacetalization of Heterocyclic Aromatic and Aliphatic Compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 3092–3096. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.-C.; Zhu J. Hafnium Trifluoromethanesulfonate (Hafnium Triflate) as a Highly Efficient Catalyst for Chemoselective Thioacetalization and Transthioacetalization of Carbonyl Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 9522–9524. 10.1021/jo8021988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaterian H. R.; Azizi K.; Fahimi N. Silica-Supported Phosphorus Pentoxide: A Reusable Catalyst for S,S-Acetalization of Carbonyl Groups under Ambient Conditions. J. Sulfur Chem. 2011, 32, 85–91. 10.1080/17415993.2010.542155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Cyanuric Chloride-Catalyzed Thioacetalization for Organocatalytic Synthesis of Thioacetals. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2016, 191, 679–682. 10.1080/10426507.2015.1054934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tazaki M.; Takagi M. Deoxygenative Thioacetalization of Carbonyl Compounds With Organic Disulfide and Tributylphosphine. Chem. Lett. 1979, 8, 767–770. 10.1246/cl.1979.767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamane V.; Aubert E.; Fort Y. The Methyl Group as a Source of Structural Diversity in Heterocyclic Chemistry: Side Chain Functionalization of Picolines and Related Heterocycles. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7294–7300. 10.1021/jo071209z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranu B. C.; Saha A.; Mandal T. An Indium–TMSCl Promoted Reaction of Diphenyl Diselenide and Diorganyl Disulfides with Aldehydes: Novel Routes to Selenoacetals Thioacetals and Alkyl Phenyl Selenides. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 2072–2078. 10.1016/j.tet.2008.12.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Grimm K. G.; Truesdale L. K. Methylthiotrimethylsilane. Versatile Reagent for Thioketalization under Neutral Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 3229–3230. 10.1021/ja00844a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Truesdale L. K.; Grimm K. G.; Nesbitt S. L. Thiosilanes, a Promising Class of Reagents for Selective Carbonyl Protection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 5009–5017. 10.1021/ja00457a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig G. W.; Sternberg E. D.; Jones G. H.; Moffatt J. G. Synthesis of 9-[5-(Alkylthio)-5-Deoxy-β-D-Erytiiro-Pent-4-Enofuranosyl)Adenines as Potential Inhibitors of Transmethylation. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 1258–1264. 10.1021/jo00358a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mantus E. K.; Clardy J. The Synthesis of Dithyreanitrile. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 1085–1086. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77496-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Kiappes J. L.; Tian W.; Gondi V. B.; Becker J. Synthesis of the Carboline Disaccharide Domain of Shishijimicin A. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3924–3927. 10.1021/ol201444t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Li R.; Lu Z.; Pitsinos E. N.; Alemany L. B.; Aujay M.; Lee C.; Sandoval J.; Gavrilyuk J. Streamlined Total Synthesis of Shishijimicin A and Its Application to the Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Analogues Thereof and Practical Syntheses of PhthNSSMe and Related Sulfenylating Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12120–12136. 10.1021/jacs.8b06955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuji K.; Node M.; Kawabata T.; Fujimoto M. Hard Acid and Soft Nucleophile Systems. Part 11. Hard-Soft Affinity Inversion: Dehalogenation of α-Halogeno Ketones with Aluminium Chloride and a Thiol. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1987, 1043–1047. 10.1039/P19870001043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leber J. D.; Elliott J. D. The Preperation of 9-Alkylthiofluorenes from Biphenyl-2-Carboxaldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 6849–6850. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)93368-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parnes R.; Pappo D. Reductive Alkylation of Arenes by a Thiol-Based Multicomponent Reaction. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2924–2927. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson P.; Hellriegel E. T. Clinical Pharmacokinetic Profile of Modafinil. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 123–137. 10.2165/00003088-200342020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konofal A.Lauflumide and the Enantiomers Thereof, Method for Preparing Same and Therapeutic Uses Thereof U.S. Patent 20130295196A1, 2013

- Martin E.; Tozer T. N.; Sheiner L. B.; Riegelman S. The Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Phenytoin. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1977, 5, 579–596. 10.1007/BF01059685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahlquist A.; Blockhuys S.; Steijlen P.; Van Rossem K.; Didona B.; Blanco D.; Traupe H. Oral Liarozole in the Treatment of Patients with Moderate/Severe Lamellar Ichthyosis: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Multinational, Placebo-Controlled Phase II/III Trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 170, 173–181. 10.1111/bjd.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien J. Y.; Banfield C. R.; Brazzell R. K.; Mayer P. R.; Slattery J. T. Saturable Tissue Binding and Imirestat Pharmacokinetics in Rats. Pharm. Res. 1992, 9, 469–473. 10.1023/a:1015880011131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.; Manna S. K.; Jana A. K.; Saha T.; Mishra P.; Bera S.; Parai M. K.; Srinivas Lavanya Kumar M.; Mondal S.; Trivedi P.; et al. Thiophene Containing Trisubstituted Methanes [TRSMs] as Identified Lead against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 95, 357–368. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. B.; Webb R. B. A Comparison of the Crystal Violet Nuclear Stain with Other Technics. Stain Technol. 1955, 30, 73–78. 10.3109/10520295509113747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand K. N. Crystal Violet Can Be Used to Visualize DNA Bands during Gel Electrophoresis and to Improve Cloning Efficiency. Tech. Tips Online 1996, 1, 23–24. 10.1016/S1366-2120(07)70016-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause R. G. E.; Goldring J. P. D. Crystal Violet Stains Proteins in SDS-PAGE Gels and Zymograms. Anal. Biochem. 2019, 566, 107–115. 10.1016/j.ab.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maley A. M.; Arbiser J. L. Gentian Violet: A 19th Century Drug Re-Emerges in the 21st Century. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 775–780. 10.1111/exd.12257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehedi M. S.; Tepe J. J. Diastereoselective One-Pot Synthesis of Oxazolines Using Sulfur Ylides and Acyl Imines. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 7219–7226. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Lu X. Cationic Pd(II)/Bipyridine-Catalyzed Addition of Arylboronic Acids to Arylaldehydes. One-Pot Synthesis of Unsymmetrical Triarylmethanes. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9757–9760. 10.1021/jo071232k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; He T.; Wang L. FeCl3 as Lewis Acid Catalyzed One-Pot Three-Component Aza-Friedel-Crafts Reactions of Indoles, Aldehydes, and Tertiary Aromatic Amines. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3420–3426. 10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Zhang X.; Li N.; Xu X.; Qiu R.; Yin S. Synthesis and Structure of an Air-Stable Binuclear Complex of Bis(Ethylcyclopentadienyl)Zirconium Perfluorooctanesulfonate and Its Catalytic Application in One-Pot Three-Component Aza-Friedel-Crafts Reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 120–123. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.10.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kothandapani J.; Ganesan A.; Vairaprakash P.; Ganesan S. S. Copper(II) Chloride Assisted Aryl Exchange in Arylmethanes: A Simple and Efficient Route to Triarylmethane Derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 2238–2242. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.03.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chinta B. S.; Baire B. Catalyst Free, Three-Component Approach for Unsymmetrical Triarylmethanes (TRAMs). Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5381–5384. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.10.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drosten G.; Mischke P.; Voß J. Elektroreduktion Organischer Verbindungen, 9 1) Vereinfachte Elektrochemische Darstellung von Thioacetalen Aus Dithioestern. Chem. Ber. 1987, 120, 1757–1761. 10.1002/cber.19871201023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Schuster G. B. Photo-Stevens Rearrangement of 9-Dimethylsulfonium Fluorenylide. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 61801, 716–719. 10.1021/jo00239a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff T.; Wood S. Production of Malachite Green Oxalate and Leucomalachite Green Reference Materials Certified for Purity. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 391, 2035–2045. 10.1007/s00216-008-2048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.