Abstract

The post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 present major problems for many patients, their physicians and the health-care system. They are unrelated to the severity of the initial infection, are often highly symptomatic and can occur after vaccination. Many sequelae involve cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction, with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in 30% of individuals. Prognosis is unknown, and treatment is still unsatisfactory.

Subject terms: Hypertension, Neurovascular disorders, Infectious diseases

When the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic swept the world in early 2020, few could imagine the long-term consequences of this disease. During the first pandemic year — before vaccines had been developed — the focus was on surviving the acute infection, which many patients, especially older ones, did not do. In mid-2020, a new group of patients, so-called post-COVID-19 long-haulers, emerged. These individuals were constantly tired, incapable of work, often young or middle-aged women, with multiple symptoms, including heart palpitations, tachycardia, orthostatic and exercise intolerance, and chest pain1. Many physicians, cardiologists and neurologists realized that some of these symptoms were identical to those of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), as were patient responses to cardiovascular autonomic tests2. Other variations of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction, such as inappropriate sinus tachycardia, were also reported3. POTS is considered to be a major phenotype in the new post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, with an estimated prevalence of ~30% among highly symptomatic patients4, but other forms of cardiovascular dysautonomia, such as orthostatic intolerance or hypotension and vasovagal reflex susceptibility, have been also reported5.

“POTS is considered to be a major phenotype in the new post-acute COVID-19 syndrome”

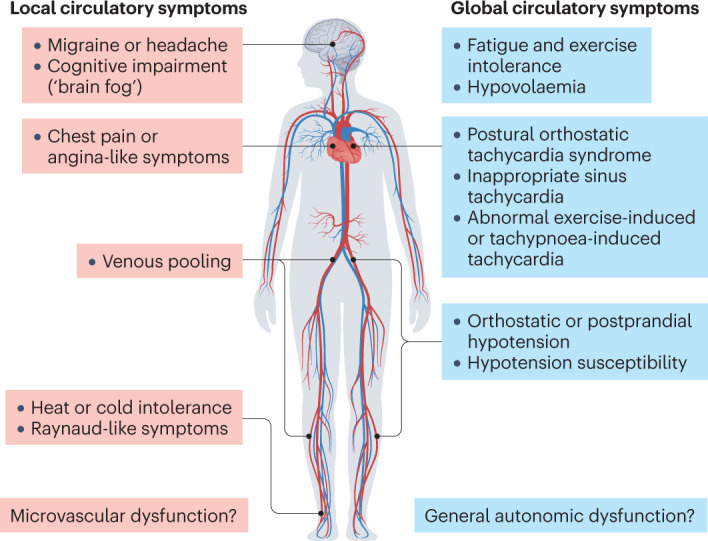

POTS cannot be confirmed without correctly interpreted cardiovascular autonomic testing. An appropriately performed active standing test (ideally with beat-to-beat non-invasive blood pressure recording, because POTS manifestations can be transient) is sufficient but is often omitted during diagnostic testing or its results ignored. The syndrome includes an exaggerated chronotropic response to standing of >30 bpm with maintained blood pressure and chronic symptoms of orthostatic intolerance and fatigue, in the absence of other explanatory pathologies6. The whole clinical picture is usually complicated by other symptoms, including unexplained chest pain, migraine, brain fog, muscle weakness and sleep disturbances7 (Fig. 1). This pattern can result in patients being referred between various clinical specialties, unable to procure a diagnosis that leads to effective therapy delivered by a caring medical team, including exercise, support stockings, fluids, ivabradine for tachycardia, and midodrine to support blood pressure.

Fig. 1. Typical manifestations of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome-related cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction.

The two main types of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction — local and global — usually overlap. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and inappropriate sinus tachycardia are the most prevalent phenotypes, found in ~30% of highly symptomatic patients with post-acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome. Peripheral circulatory disorders are thought to stem from microvascular and endothelial dysfunction and can lead to local symptoms such as headache, cognitive impairment (‘brain fog’), chest pain (angina-like symptoms), dyspnoea, heat or cold intolerance, Raynaud-like phenomena and venous pooling. Relative or absolute hypovolaemia can be present.

Recent reports have highlighted this problem by underscoring the place of POTS in the post-COVID-19 landscape1, calling for more diagnostic vigilance, greater availability of health-care resources and new therapeutic options. Interestingly, POTS and related conditions, such as mast cell disorders, chronic fatigue and general dysautonomia, are diagnosed more often in the 3 months after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, but can also develop after COVID-19 vaccination. The medium-term to long-term prognosis is not well understood8, but one report suggests that many patients can spontaneously recover over the next 12 months9.

“either SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 vaccination can trigger POTS and other cardiovascular dysautonomias”

Given that either SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 vaccination can trigger POTS and other cardiovascular dysautonomias, it has been hypothesized that these factors might be potent immune triggers that evoke an autoimmune response in susceptible individuals. Moreover, the occurrence of these cardiovascular dysautonomias seems to be unrelated to the severity of initial infection4. Future research might reveal an immunomodulating agent that abates the hypothetically overstimulated or misdirected immune response. However, reliable immunological tests that can identify the immune mediator of the observed functional changes in the autonomic nervous system are currently lacking. Additionally, the identification of genetic or epidemiological markers of increased risk of cardiovascular dysautonomia should be prioritized.

The post-COVID-19 cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction can affect global circulatory control, producing not only a POTS-like pattern but also tachycardia at rest, blood pressure instability with both hypotension and hypertension, and local circulatory disorders such as migraine, coronary microvascular dysfunction or Raynaud-like symptoms (Fig. 1). Microvascular dysfunction with inadequate regional microvascular and macrovascular responses, such as vasospasm and circulatory mismatch between local oxygen demands and supply, and venous retention leading to pooling and reduced venous return after standing, might explain the plethora of symptoms that are frequently observed in POTS. There are sparse reports suggesting that microvascular dysfunction is an important mechanism of post-COVID-19 complications10. All these dysautonomic phenotypes might coexist, and, more importantly, they preferentially affect young and middle-aged women, possibly suggesting a genetic predisposition and/or a mechanistic role for sex hormones. Of note, POTS is extremely rare among either prepubertal girls or postmenopausal women6.

“post-COVID-19 cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction can affect global circulatory control”

As more evidence emerges, it will be important to have better precision phenotyping of POTS in prospective cohorts of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, to identify reliable biomarkers of the condition and to design clinical trials to test the best candidates for an effective therapy for the syndrome.

Competing interests

A.F. has received speaker fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Finapres Medical Systems and Medtronic, and is a consultant to Argenx and Medtronic. R.S. has received consulting fees from Medtronic and payment for expert testimony in medicolegal cases in the UK; is a member of the clinical events committee for the BioSync study; and is secretary to the Executive Board of the World Society of Arrhythmias.

References

- 1.Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson M, et al. Long-haul post-COVID-19 symptoms presenting as a variant of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Swedish experience. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ståhlberg M, et al. Post-COVID-19 tachycardia syndrome: a distinct phenotype of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Am. J. Med. 2021;134:1451–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hira R, et al. Objective hemodynamic cardiovascular autonomic abnormalities in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamal SM, et al. Prospective evaluation of autonomic dysfunction in post-acute sequela of COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022;79:2325–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedorowski A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J. Intern. Med. 2019;285:352–366. doi: 10.1111/joim.12852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spahic JM, et al. Malmö POTS symptom score: assessing symptom burden in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J. Intern. Med. 2023;293:91–99. doi: 10.1111/joim.13566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwan AC, et al. Apparent risks of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome diagnoses after COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022;1:1187–1194. doi: 10.1038/s44161-022-00177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizrahi B, et al. Long covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2023;380:e072529. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahdi A, et al. Erythrocytes induce vascular dysfunction in COVID-19. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2022;7:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]